Abstract

Objective

To describe the incidence and clinical characteristics of epiretinal membranes in children.

Methods

The medical records of all pediatric (< 19 years of age) patients diagnosed with an epiretinal membrane from January 1, 1976, through December 31, 2005, at Olmsted Medical Group and Mayo Clinic were retrospectively reviewed. Incidence and clinical findings of childhood epiretinal membranes were obtained.

Results

Five of the 44 total patients were diagnosed as residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, yielding an annual age- and gender-adjusted incidence of 0.54 per 100,000 patients, or 1 in 20,896 < 19 years of age. The mean age at diagnosis of the study patients was 12.4 years (range, 4 months to 18 years) with a preponderance of boys (70.5%). The presenting visual acuity in the affected eye was ≤ 20/60 in 22 (50%), while ten (22.2%) displayed strabismus. Common causes were trauma (38.6%), idiopathic (27.3%), and uveitis (20.5%). Eight (17.8%) of the 44 underwent pars plana vitrectomy with membrane peel, with at least 5 of the 8 experiencing an improvement in their postoperative visual acuity.

Conclusions

Epiretinal membranes are rare in children and are most frequently associated with a traumatic, idiopathic, or uveitic etiology. Those patients treated surgically generally have a favorable outcome.

Epiretinal membranes (ERM) are characterized by a wrinkling or distortion of the macular surface caused by retinal cell proliferation. Also known as macular pucker or cellophane maculopathy, ERM most often occur in patients older than 50 years of age and are usually bilateral although often asymmetric. In adults, ERM generally occur in association with ocular disease, idiopathically, or following retinal reattachment surgery. Less commonly, ERM can also occur in younger patients following trauma or from ocular disorders such as uveitis, retinal vascular disease, or tumors. Although there are studies of epiretinal membranes among patients up to the age of forty years,1,2 there are no known reports devoted exclusively to children. The purpose of this study was to describe the incidence and clinical characteristics of epiretinal membranes in patients < 19 years studied over a thirty-year period.

Subjects and Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained for this study. The medical records of all patients younger than 19 years of age diagnosed at our institution with an epiretinal membrane from January 1, 1976, through December 31, 2005, were retrospectively reviewed. We also identified pediatric patients who were residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, when diagnosed with an epiretinal membrane during the same time period. Olmsted County cases were identified by the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP), a medical records linkage system designed to capture data on any patient-physician encounter in this county.3 The population of Olmsted County (106,470 in 1990) is relatively isolated from other urban areas, and virtually all medical care is provided to residents by Mayo Clinic or Olmsted Medical Group and their affiliated hospitals. We also reviewed the ophthalmic records of all pediatric patients who had fundus photography or Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) for any diagnosis of macular pathology during the same time interval.

Of 153 potential cases generated by the diagnostic code search from these two institutions, 58 were eliminated on the basis of their age at the time of diagnosis. Fifty-one of the remaining 95 patients were excluded due to an incorrect diagnosis, including two patients with persistent fetal vasculature. The remaining 44 patients were included in this study. Historical characteristics concerning age, race, gender, trauma, date of onset of symptoms, and date of diagnosis were collected. The ophthalmic record was carefully reviewed for visual acuity, ocular misalignment, anterior segment findings, and refractive error. Funduscopic examination included indirect ophthalmoscopy of the posterior pole and peripheral retina, and the use of the Hruby lens or 90 diopter lens for the presence or absence of foveal involvement, vascular distortion, puckering, cellophaning and macular edema.

Each case was classified by the following etiologic types; 1) traumatic, 2) uveitic, 3) idiopathic, and 4) other. The trauma designation included blunt, penetrating, perforating, intraocular foreign body, ruptures and contusions. The uveitis patients were classified as anterior, intermediate or posterior. Other etiologies of epiretinal membranes included any epiretinal membranes not classified by the three primary groups. Epiretinal membranes that occurred solely as a result of intraocular surgery were not included in this series. The medical record of each patient was reviewed for progression of disease, type of management, and final outcome.

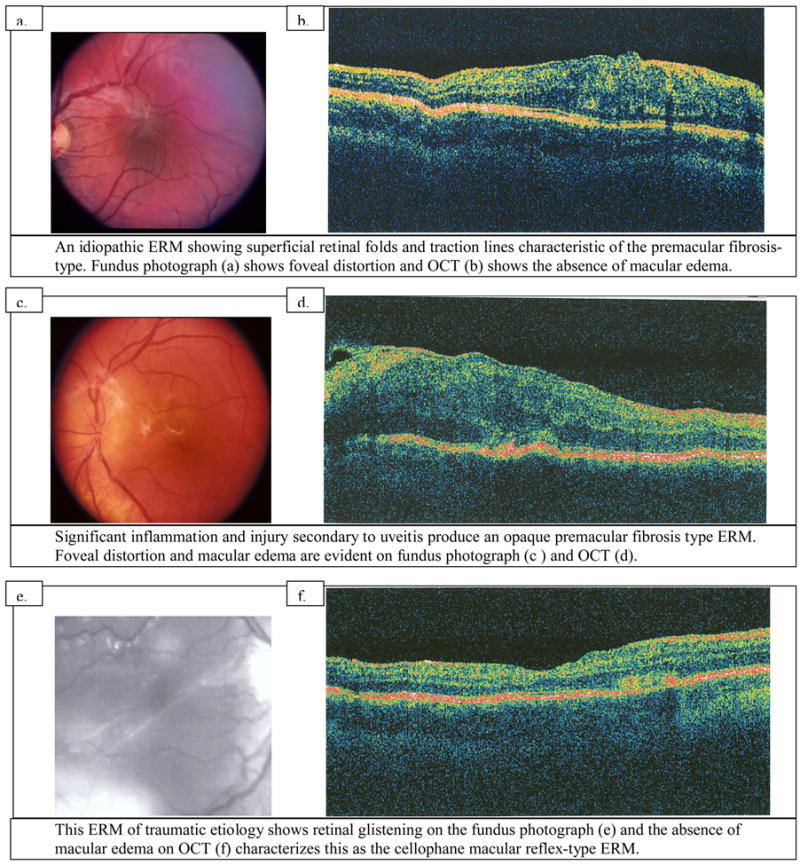

Clinical findings as demonstrated by red-free fundus photographs, OCT, and fluorescein angiography were retrospectively reviewed when available, in order to 1) verify the diagnosis of ERM and, 2) characterize the forms of ERM in a standardized manner according to the severity of retinal distortion. The various types of epiretinal membranes were defined in the following manner. The presence or absence of glistening, folds, traction, vascular distortion, foveal distortion, and/or macular edema was used to confirm the ERM diagnosis and to characterize the degree of severity. From this data, we divided the epiretinal membranes into cellophane macular reflex (CMR) type and premacular fibrosis (PMF) type.4 The cellophane type was defined as a patch or patches of irregular increased reflection from the inner surface of the retina. The diagnosis was made by an inappropriate “cellophane” light reflex. The premacular fibrosis type, a more severe type, occurs as the membrane thickens and contracts, becoming opaque and gray with the appearance of superficial retinal folds and traction lines. Subjects with both a cellophane macular reflex and preretinal macular fibrosis were allocated to the PMF group.

To determine the incidence of epiretinal membranes in children in Olmsted County, Minnesota, annual age- and gender-specific incidence rates were constructed using the age- and gender-specific population figures for this county from the United States census. Age- and gender-specific denominators for individual years were generated from linear interpolation of the 1970, 1980, 1990, and 2000 census figures. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated with assumptions based on the Poisson distribution.

Results

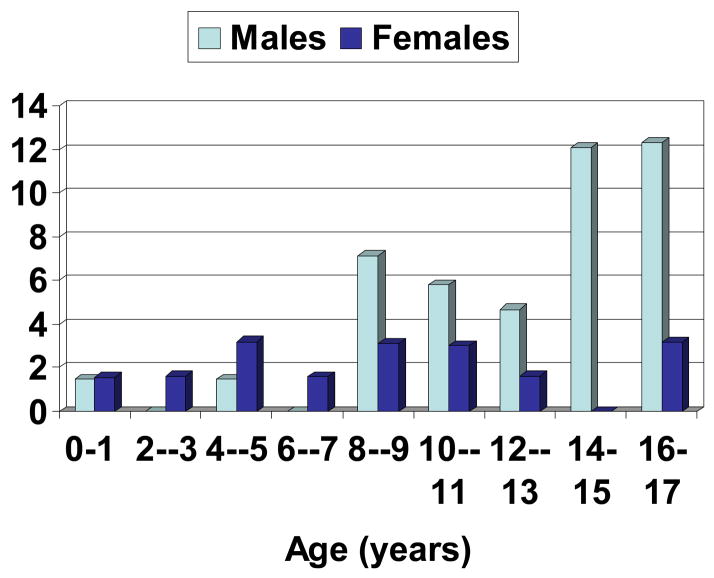

Forty-four new cases of epiretinal membranes in children were diagnosed during the 30-year study period. There were 13 female (29.5%) cases and five (11.4%) of the study patients exhibited bilateral involvement. The mean age at diagnosis of the 44 study patients was 12.4 years (range, 4 months to 18 years). Epiretinal membranes tended to be more common among boys than girls in the second decade of life as shown in the Figure. The presenting visual acuity in the affected (or worse) eye was ≤ 20/60 in 22 (50%), while ten (22.7%) of 44 children displayed strabismus. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the 44 study patients. Among the 44 patients with membranes, 17 (38.6%) were associated with trauma, 12 (27.3%) were idiopathic, 9 (20.5%) occurred in the setting of uveitis, and the remaining 6 (13.6%) developed in association with other disorders as listed in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Incidence of Childhood Epiretinal Membranes by Gender, 1976 through 2005

Table 1.

Characteristics of Epiretinal Membranes among 44 Consecutive Patients < 19 Years, 1976 through 2005

| Age | Gender | Eye | Etiology | Type | Management | Initial VA | Final VA | Changes in VA (Lines) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OD | Followed | ||||||||

| 1 | 8 | M | Traumatic | Unknown | Elsewhere | 20/200 | Unknown | Unknown | |

| 2 | 9 | M | OD | Traumatic | None | Observation | 20/100 | 20/20 | 8 |

| 3 | 10 | M | OD | Traumatic | CMR | Observation | 20/70 | 20/40 | 3 |

| 4 | 10 | M | OD | Traumatic | Unknown | Observation | 20/60 | 20/200 | −6 |

| 5 | 11 | M | OS | Traumatic | CMR | Observation | 20/70 | 20/20 | 6 |

| 6 | 12 | M | OS | Traumatic | None | Observation | 20/30 | 20/25 | 1 |

| OD | Followed | ||||||||

| 7 | 12 | M | Traumatic | Unknown | Elsewhere | 20/40 | Unknown | Unknown | |

| 8 | 14 | M | OS | Traumatic | Unknown | Observation | 20/400 | 20/200 | 3 |

| OD | Followed | ||||||||

| 9 | 15 | M | Traumatic | None | Elsewhere | 20/40 | Unknown | Unknown | |

| OS | Followed | ||||||||

| 10 | 15 | M | Traumatic | Unknown | Elsewhere | 20/80 | Unknown | Unknown | |

| 11 | 15 | M | OS | Traumatic | Unknown | Observation | 20/60 | 20/20 | 5 |

| 12 | 16 | M | OD | Traumatic | Unknown | Observation | 20/200 | FC | Unknown |

| OS | Followed | ||||||||

| 13 | 16 | F | Traumatic | PMF | Elsewhere | 20/25 | Unknown | Unknown | |

| 14 | 16 | M | OD | Traumatic | Unknown | Observation | 20/300 | 20/300 | 1 |

| 15 | 16 | M | OD | Traumatic | CMR | Observation | 20/40 | 20/30 | 1 |

| 16 | 17 | M | OD | Traumatic | Unknown | Observation | 20/40 | 20/30 | 1 |

| 17 | 18 | M | OD | Traumatic | Unknown | Observation | 20/60 | 20/80 | −2 |

| 18 | 1 | F | OD | Idiopathic | PMF | PPV | Not Specified | 20/40 | Unknown |

| 19 | 3 | F | OD | Idiopathic | PMF | Observation | 20/160 | 20/200 | 4 |

| OD | Followed | ||||||||

| 20 | 5 | F | Idiopathic | Unknown | Elsewhere | 20/250 | Unknown | Unknown | |

| 21 | 5 | F | OS | Idiopathic | PMF | Observation | 20/40 | 20/25 | 2 |

| 22 | 5 | M | OS | Idiopathic | PMF | PPV | 20/125 | 20/100 | 1 |

| 23 | 8 | F | OD | Idiopathic | Unknown | Observation | 20/30 | 20/25 | 1 |

| OD | Followed | ||||||||

| 24 | 10 | M | Idiopathic | CMR | Elsewhere | 20/20 | Unknown | Unknown | |

| 25 | 11 | M | OS | Idiopathic | CMR | Observation | 20/30 | 20/30 | 0 |

| 26 | 13 | M | OS | Idiopathic | PMF | PPV | Not Specified | 20/150 | Unknown |

| 27 | 15 | M | OD | Idiopathic | Unknown | PPV | 20/100 | 20/100 | 0 |

| OS | Followed | ||||||||

| 28 | 17 | M | Idiopathic | CMR | Elsewhere | HM | Unknown | Unknown | |

| OS | Followed | ||||||||

| 29 | 18 | M | Idiopathic | Unknown | Elsewhere | 20/25 | Unknown | Unknown | |

| OD | PMF | PPV | 20/100 | 20/30 | 6 | ||||

| 30 | 8 | F | OS | Uveitic | PMF | PPV | 20/150 | 20/60 | 5 |

| OD | Observation | 20/20 | 20/25 | −1 | |||||

| 31 | 10 | F | OS | Uveitic | Unknown | 20/30 | 20/30 | 0 | |

| OD | CMR | 20/50 | 20/100 | − 4 | |||||

| 32 | 13 | F | OS | Uveitic | PMF | Observation | 20/80 | 20/100 | − 1 |

| OD | PMF | Followed | 20/20 | ||||||

| 33 | 13 | M | OS | Uveitic | PMF | Elsewhere | 20/250 | Unknown | Unknown |

| 34 | 16 | M | OS | Uveitic | PMF | Observation | 20/40 | 20/70 | −3 |

| 35 | 16 | M | OD | Uveitic | PMF | PPV | 20/40 | 20/20 | 3 |

| 36 | 18 | F | OS | Uveitic | Unknown | Observation | 20/40 | 20/40 | 0 |

| OS | Followed | ||||||||

| 37 | 18 | F | Uveitic | Unknown | Elsewhere | 20/20 | Unknown | Unknown | |

| 38 | 18 | F | OS | Uveitic | PMF | PPV | 20/100 | 20/20 | 8 |

| OD | PMF | LP | NLP | ||||||

| 39 | 0 | M | OS | Other | PMF | Observation | LP | FC | Unknown |

| OD | Followed | ||||||||

| 40 | 12 | F | Other | PMF | Elsewhere | 20/50 | Unknown | Unknown | |

| 41 | 8 | M | OS | Other | PMF | PPV | 20/400 | Not Specified | Unknown |

| 42 | 9 | M | OD | Other | PMF | Observation | 20/20 | 20/20 | 0 |

| OS | Followed | ||||||||

| 43 | 15 | M | Other | Unknown | Elsewhere | 20/70 | Unknown | Unknown | |

| 44 | 15 | M | OS | Other | PMF | Steroids | 20/60 | 20/50 | 1 |

OD= right eye, OS = left eye

CMR= Cellophane Macular Reflex, PMF = Premacular Fibrosis

PPV = Pars Plana Vitrectomy

FC= Finger Counting, HM= Hand motion, LP= Light Perception, NLP= No Light Perception Change in VA - negative number signifies a decrease in visual acuity

Table 2.

Etiology of Epiretinal Membranes among 44 Consecutive Patients < 19 Years, 1976 through 2005

| ERM Type | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Traumatic | 17 | 38.6 |

| Anterior segment only | 7 | |

| Posterior segment only | 2 | |

| Anterior and posterior | 3 | |

| Blunt trauma | 5 | |

|

| ||

| Uveitic | 9 | 20.5 |

| Posterior | 6 | |

| Intermediate | 3 | |

| Anterior | 0 | |

|

| ||

| Idiopathic | 12 | 27.3 |

|

| ||

| Other* | 6 | 13.6 |

Includes 2 patients with retinal hamartomas, and 1 each with toxoplasma canis, Gorlin’s syndrome, and retinal detachment.

Five (11.4%) of forty-four patients resided in Olmstead County, Minnesota at the time of their diagnosis, yielding an annual age- and gender-adjusted incidence of 0.54 per 100,000 or 1 in 20,896 < 19 years of age. Four of the 5 patients were male. The mean age at diagnosis for the five patients was 13.2 years (range, 5 years to 18 years). All five patients had unilateral involvement and one patient displayed strabismus. The median visual acuity for the affected eye was 20/40 with a final median visual acuity of 20/125 during a mean follow-up of 6.1 years. Three of these ERM were secondary to trauma and all five were managed with observation alone.

Fundus imaging was available in 27 (61.4%) of the 44 patients and a review of the images was performed by a retinal specialist who made these determinations without previewing the patients’ medical records or diagnoses. One of these patients had bilateral membranes yielding 28 eyes with ERM. Epiretinal membranes of the premacular fibrosis type were the most frequently diagnosed form of epiretinal membranes, comprising 21 (75%) of 28 eyes with ERM, while epiretinal membranes of the cellophane macular reflex type comprised the remaining 7 (25%) eyes.

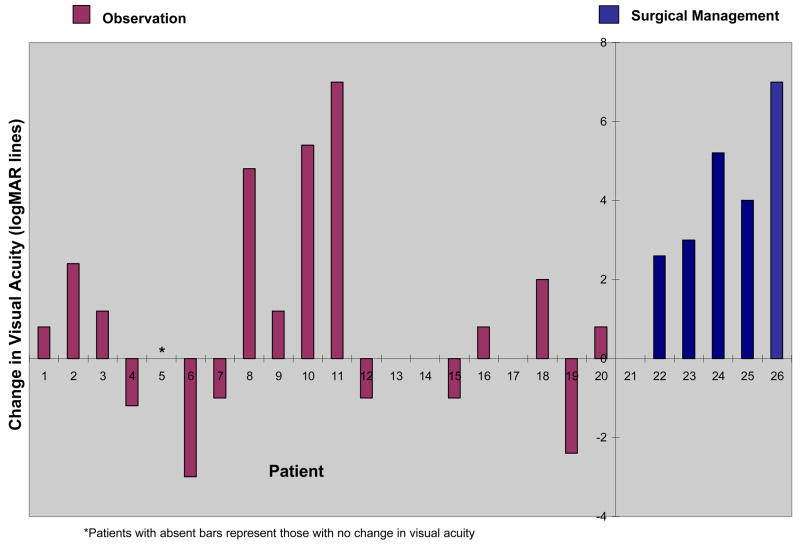

The median visual acuity, from first exam to last exam (mean duration of 3.1 years), improved from 20/65 to 20/20 for the 44 study patients. Twenty-four (54.5%) of the 44 patients with epiretinal membranes were managed with observation alone, 8 (18.2%) were managed with pars plana vitrectomy, and 1 (1.3%) was managed with steroids. The remaining eleven patients were followed elsewhere and treatment information was unavailable. Table 2 outlines surgical outcomes for the eight patients who were managed with pars plana vitrectomy and membrane peel. The final postoperative visual acuity for these patients demonstrated a mean improvement of 3.8 lines during a mean follow-up of 33 months. The vision in all 4 of the uveitic cases and at least 1 of the idiopathic cases improved postoperatively. One of the eight patients had bilateral ERM secondary to uveitis and underwent a surgical procedure in each eye. Postoperative complications included one each with cataract formation and an ERM recurrence requiring a second membrane peel.

Discussion

This study describes a population-based incidence rate and the clinical characteristics of epiretinal membranes from a large cohort of pediatric patients. Membrane formation occurred in approximately 1 in 20,896 individuals < 19 years of age in Olmsted County, Minnesota. There was a preponderance of boys with most membranes occurring in the second decade of life. The initial visual acuity of the affected eye was ≤ 20/60 in half the patients while 22.2% presented with strabismus. Surgical intervention, although relatively uncommon in this study, resulted in improved visual acuity for most patients.

This study also reports the common etiologies of epiretinal membranes in children. Trauma to the eye or orbit occurred in 17 (38.6 %) of 44 patients and boys made up 16 of these 17 patients who suffered ocular trauma. Males, especially in the second decade of life, are more likely than similarly-aged females to engage in risk-taking behavior that may expose them to trauma and subsequent membrane formation. Isolated anterior segment trauma was the most common form of trauma leading to ERM formation in this cohort. Membranes associated with uveitis occurred in 1 of 5 children in this study and was most often a result of chronic inflammation with cystoid macular edema. Idiopathic membranes were found in approximately 1 of 4 children, with clinical features similar to the other forms of membranes. Banach and associates examined ERM in 20 eyes in patients less than 40 years old and all were of the idiopathic etiology.1 Benhamou and associates, reporting on 20 patients from 7 to 26 years of age, found an idiopathic cause in 11 (55%) of their patients.2

This study also reports the relative prevalence of the two main varieties of epiretinal membranes in children. Cellophane macular reflex type, often considered the most common and benign form of epiretinal membranes,5 was relatively uncommon in this population, comprising only 25% of the total patients. The more severe premacular fibrosis type of membrane was diagnosed in 3 of 4 children in this study. Although Banach and associates did not classify the type of ERM in their patients,1 Benhanou and associates reported findings similar to this study.2 They described 13 (65%) of 20 eyes as having a “thick, white, and contractile” membrane (similar to the premacular fibrosis designation) and the remaining 7 eyes as having a “thin transparent membrane” (similar to the cellophane macular reflex designation).2 The predominance of the premacular fibrosis type of ERM in this study may be related to the high prevalence of the traumatic and uveitic causes, both of which may be more prone to significant injury and inflammation. Such a classification system appears useful in assessing clinical characteristics and surgical outcomes.

Published studies on the management of epiretinal membranes in young patients have demonstrated that membrane peeling can be safely performed with a improvement in visual acuity.1,2 Spontaneous peeling of the ERM in young patients has also been reported6,7 and observation alone may also be warranted. Banach and associates compared two groups of subjects under 40 years of age with idiopathic ERMs.1 One group, with visual acuity of 20/50 or better, was merely observed while the second group, with a visual acuity of 20/60 or worse, underwent surgery. Ten (77%) of 13 cases managed with surgical peeling experienced an improvement of vision and 50 % of the cases managed with observation alone had stable or improved vision. Benhamou and coauthors also found ERM peeling to be safe in 20 young patients who had an improvement in postoperative visual acuity.2

The 8 patients who underwent pars plana vitrectomy in this study had a mean visual improvement of 3.8 lines which is comparable to the 4.25 lines of improvement reported in a prior study of young subjects.2 One of the patients in this study subsequently developed a nuclear sclerotic cataract while another developed a recurrent ERM sufficient to require a second peeling. Reoperation for an ERM recurrence among young patients has been reported as high as 5 (25%) of 20 patients.1

Pars plana vitrectomy with membrane peeling is a viable treatment option for pediatric epiretinal membranes, and appears to be as safe in children as it is for adults. Surgical intervention may be more successful for ERM secondary to chronic uveitis compared to idiopathic membranes, and a repeat procedure may be required. Only one (12.5%) of the 8 patients in this study who underwent pars plana vitrectomy had a recurrent ERM requiring a second procedure. This relatively low rate may be due to variations in surgical technique and equipment at different institutions.

There are a number of limitations to the findings in this study. Our reported incidence rate may be below the true value since this condition is often discovered on routine eye examination, and some patients with an epiretinal membrane may have gone unnoticed by the caretaker, thereby avoiding an evaluation by the study ophthalmologists. Moreover, some residents may have sought care outside Olmsted County. This study is also limited by its retrospective nature. The diagnostic criteria and methods of examination have evolved over the past 30 years; however, we retrospectively reviewed the available imaging for 27 (61.4%) of the 44 study patients for confirmation and consistency of diagnosis.

This study found that epiretinal membranes occur in approximately 1 in 21,000 children. The most common causes were trauma, uveitis, or idiopathic with a preponderance of boys, especially in the second decade of life. For those patients who underwent pars plana vitrectomy with membrane peel, most experienced an improvement in vision.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Table 3.

Surgical Outcomes for Epiretinal Membranes following Pars Plana Vitrectomy with Membrane Peel in 9 Eyes among 8 Patients < 19 Years

| Age(years) | Etiology | Type | Pre Op VA in affected eye | Final VA | Change in VA(Lines) | Follow Up Time(months) | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Idiopathic | PMF | Not Specified | 20/40 | Unknown | 37 | None |

| 5 | Idiopathic | PMF | 20/125 | 20/70 | 1 | 3 | Recurrent ERM and second PPV |

| 8 | Uveitic | PMF | 20/100(OD) | 20/30 | 6 | 51 | None |

| Uveitic | PMF | 20/150(OS) | 20/60 | 5 | 25 | None | |

| 8 | Other | PMF | 20/400 | Not Specified | Unknown | NA | NA |

| 13 | Idiopathic | PMF | Not Specified | 20/150 | Unknown | 45 | None |

| 15 | Idiopathic | NA | 20/100 | 20/100 | 0 | 7 | None |

| 16 | Uveitic | PMF | 20/40 | 20/20 | 3 | 4 | None |

| 18 | Uveitic | PMF | 20/100 | 20/20 | 8 | 97 | Cataract |

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc, New York, NY. The sponsor or funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research. No conflicting relationship exists for any author.

References

- 1.Banach MJ, Hassan TS, Cox MS, Margherio RR, Williams GA, Garretson BR, Trese MT. Clinical course and surgical treatment of macular epiretinal membranes in young subjects. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:23–6. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benhamou N, Massin P, Spolaore R, Paques M, Gaudric A. Surgical management of epiretinal membrane in young patients. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2002;133:358–64. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01422-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurland LT, Molgaard CA. The patient record in epidemiology. Sci Am. 1981;245:54–63. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1081-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein R, Klein BE, Wang Q, Moss SE. The epidemiology of epiretinal membranes. Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 1994;92:403–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rice TA, De Bustros S, Michels RG, Thompson JT, Debanne SM, Rowland DY. Prognostic factors in vitrectomy for epiretinal membranes of the macula. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:602–610. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33689-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desatnik H, Treister G, Moisseiev J. Spontaneous separation of an idiopathic macular pucker in a young girl [case report] Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;127:729–31. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulligan TG, Daily MJ. Spontaneous peeling of an idiopathic epiretinal membrane in a young patient. Arch Ophthalmology. 1992;110:1367–1368. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080220029009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]