A 10-yr-old boy with Cushing’s disease (CD) suffered an acute ischemic infarction after transsphenoidal surgery. The patient presented with weight gain, poor growth, hypertension, and other classic symptoms of CD. The hypertension was difficult to control despite therapy with multiple agents; blood pressure averaged at 150/90 mm Hg with brief elevations as high as 220/120 mm Hg. Laboratory evaluation revealed classic biochemical features of CD (1); magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed a microadenoma that was removed via transsphenoidal surgery. Two days postoperatively, the patient developed left lower extremity weakness and was lethargic. Postoperative MRI of the brain showed abnormalities typical for acute ischemic infarction using fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) as well as diffusion-weighted imaging; these abnormalities were not present on preoperative MRI (Figs. 1 and 2). He was found to be a carrier of the prothrombin 20210 G-to-A polymorphism but the rest of the workup (including factor V leiden, lupus anticoagulant, protein C, and protein S) was entirely normal. Anticoagulation therapy with heparin was started, followed by aspirin. The patient received physical therapy and was able to ambulate on discharge. By his 8-month visit, the patient had no residual motor deficits. Follow-up MRI revealed minimal scarring 2 yr after the event (Fig. 3), and the patient has fully recovered.

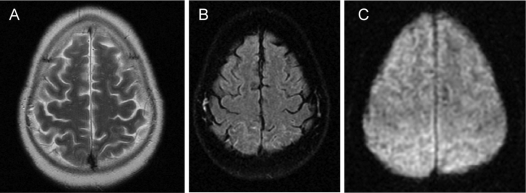

Figure 1.

Preoperative MRI of the brain: A, T2-weighted; B, FLAIR; C, diffusion-weighted. There are no brain abnormalities present.

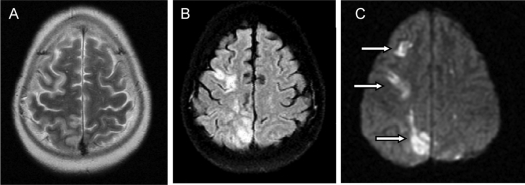

Figure 2.

Brain images obtained 2 d after surgery using identical techniques as in Fig. 1. A, T2-weighted images show no definite brain lesions. However, FLAIR (B) as well as diffusion-weighted (C) images reveal abnormal areas of increased signal intensity in the right cerebral hemisphere (arrows). Corresponding low-signal-intensity lesions were present on the apparent diffusion coefficient maps (not shown). The combination of these signal changes indicates the presence of acute ischemic infarctions.

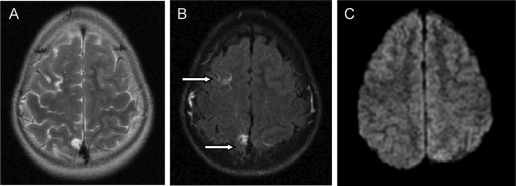

Figure 3.

Brain MRI obtained 2 yr after surgery. A and B, T2-weighted (A) and FLAIR (B) images show small glial scars in two of the ischemic infarctions previously identified in the right cerebral hemisphere; the third infarction had completely resolved. C, Diffusion weighted image at the same level is normal indicating good healing and no evidence of new acute lesions.

Hypertension is a common feature in children with CD, and conventional antihypertensives may only be partially effective (2,3). CD is also a hypercoaguable state associated with increased incidence of thromboembolic complications, especially after surgery (4). Hypertension is a known major risk factor in cerebral infarctions and may be overlooked in the pediatric population. Annual incidence rates for pediatric arterial ischemic stroke (AIS) have ranged from 0.6–7.9 per 100,000 children per year. AIS is more common in males than females and blacks compared with whites; reported outcomes for AIS in children reveal that on average up to 30% of children were neurologically normal at follow-up (5).

This is the first report of an ischemic stroke in a child with CD. Hypertension and hypercortisolemia were risk factors for the acute ischemic event in our patient. Early recognition and treatment of hypertension in patients with CD is important to avoid possible cerebrovascular complications; the prognosis appears to be good, if recognized and treated early.

Footnotes

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NICHD, NIH.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Abbreviations: AIS, Arterial ischemic stroke; CD, Cushing’s disease; FLAIR, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

References

- Batista DL, Riar J, Keil M, Stratakis CA 2007 Diagnostic tests for children who are referred for the investigation of Cushing syndrome. Pediatrics 120:e575–e586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magiakou MA, Mastorakos G, Zachman K, Chrousos GP 1997 Blood pressure in children and adolescents with Cushing’s syndrome before and after surgical care. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:1734–1738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baid S, Nieman LK 2004 Glucocorticoid excess and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 6:493–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscaro M, Sonino N, Scarda A, Barzon L, Fallo F, Sartori MT, Patrassi GM, Girolami A 2002 Anticoagulant prophylaxis markedly reduces thromboembolic complications in Cushing’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:3662–3666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JK, Han CJ 2005 Pediatric stroke: what do we know and what do we need to know? Semin Neurol 25:410–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]