Abstract

Although aging is known to lead to increased vascular stiffness, the role of estrogens in the prevention of age-related changes in the vasculature remains to be elucidated. To address this, we measured vascular function in the thoracic aorta in adult and old ovariectomized (ovx) rats with and without immediate 17β-estradiol (E2) replacement. In addition, aortic mRNA and protein were analyzed for proteins known to be involved in vasorelaxation. Aging in combination with the loss of estrogens led to decreased vasorelaxation in response to acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside, indicating either smooth muscle dysfunction and/or increased fibrosis. Loss of estrogens led to increased vascular tension in response to phenylephrine, which could be partially restored by E2 replacement. Levels of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and inducible nitric oxide synthase did not differ among the groups, nor did total nitrite plus nitrate levels. Old ovx exhibited decreased expression of both the α and β-subunits of soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) and had impaired nitric oxide signaling in the vascular smooth muscle. Immediate E2 replacement in the aged ovx prevented both the impairment in vasorelaxation, and the decreased sGC receptor expression and abnormal sGC signaling within the vascular smooth muscle.

The combination of loss of estradiol and aging leads to increased constriction (phenylephrine) and decreased relaxation with nitric oxide. Reduced soluble guanylyl cyclase mediates these changes.

Aging is A progressive process characterized by a reduction in protective responses, an increase in inflammatory mediators, and impairment of organ function. In females the loss of estrogens may further compound these changes (1). Results from the World Health Initiative study cast doubts on the protective effects of estrogens in postmenopausal women. Estrogen replacement led not only to an increased risk of breast cancer but also to increased cardiovascular disease (2). However, many of the patients enrolled in these studies had been without estrogens for 10 yr or more, and this late addition of estrogens may have had unintended or unexpected results (3). The initiation of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) closer to menopause tended to reduce coronary heart disease risk among postmenopausal women compared with women who begin HRT later in menopause (4).

The fundamental age-related change in arterial function is an impairment of relaxation, which is associated with an increase in pulse wave velocity (5). In males, this age-related decrease in vascular relaxation is characterized by reduction in the nitric oxide (NO)-dependent vasodilator response to acetylcholine (ACh) (6). This impaired response to ACh is thought to be primarily due to down-regulation in the activation and expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) (7); however, downstream changes within the vascular smooth muscle (VSM) can similarly impair vasodilation. Aging has also down-regulated the NO receptor, soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC), as well as protein kinase G (PKG)-I activation in adult male rat aortas (8,9,10). The underlying mechanisms mediating abnormal vascular function with aging remain controversial.

Estrogens, in contrast to aging, are known to be vasoprotective. In the endothelium, 17β-estradiol (E2) activates eNOS nongenomically through the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/AKT pathway (11,12). This leads to NO production within the endothelium, which then diffuses to the VSM and causes vasorelaxation. Studies in female estrogen receptor-α knockout mice have demonstrated reduced NO release and decreased relaxation in response to E2 treatment compared with wild type (13). In addition, estrogens can modulate the release of other vasoactive substances, such as prostacyclin and endothelin (14). In the VSM, estrogens reduce intracellular Ca2+ concentrations and hyperpolarize the cell by opening potassium channels (15).

There is a lack of literature addressing changes in arterial relaxation in aged females with the loss of estrogens. These two factors, aging and estrogen loss, are critical to our understanding of how menopause leads to an increased risk of hypertension, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease. Despite the body of literature addressing changes in aging and/or estrogen supplementation, much remains to be elucidated. The purpose of this study was to investigate how estrogen loss vs. aging affected vascular function, and whether any observed changes would be attenuated by E2 replacement. To address these questions, we used Norwegian brown rats, as an aging model, and compared changes in the vasculature after ovariectomized (ovx) with and without E2 replacement in young and old rats.

Materials and Methods

The animal protocol was approved by the University of California, Davis, Animal Research Committee in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Norwegian brown rats were obtained from the National Institute of Aging and housed under standard conditions in female rat only housing. Aged (19–20 months) and adult (3–4 months) female rats were ovx under sterile conditions using standard methods. In one half of the ovx rats, hormone replacement was done with 0.36 mg E2 90 d slow-release pellets (Innovative Research, Sarasota, FL) implanted sc as previously described (16). Nine weeks after ovariectomy (i.e. at 5–6 and 21–22 months), body weight was measured, and the rats were euthanized by exsanguination. Before exsanguination, plasma samples were collected by cardiac puncture for measurement of NO metabolites, cytokines, and E2. The descending thoracic aorta was excised, cleansed of adhering tissue, and cut into 3- to 4-mm long aortic rings. For each rat a segment of the aorta was harvested for vascular contraction and relaxation studies, and the remaining segment was stored at −80 C for subsequent RNA and protein studies.

Isometric tension studies

Isometric tension was measured in 3- to 4-mm long descending thoracic aortic rings from rats as previously described (17). Individual aortic rings were suspended from an isometric transducer (Radnoti Glass Technology, Inc., Monrovia, CA) in oxygenated tissue baths containing bicarbonate-buffered Krebs-Henseleit solution [118 mm NaCl, 4.6 mm KCl, 27.2 mm NaHCO3, 1.2 mm KH2PO4, 1.2 mm MgSO4, 1.75 mm CaCl2, 0.03 mm Na2EDTA, and 11.1 mm glucose (pH 7.4)]. According to length-tension curves previously established in our laboratory, a passive load of 2.0 g was applied, and the aortic segments were allowed to equilibrate for approximately 1 h with frequent readjustment of tension until reaching a stable baseline. Two KCl (70 mm)-induced contractions were performed to train the vessels to constrict. Rings were then washed and allowed to equilibrate for 40 min. To determine the maximum contractile response, a concentration-response curve to l-phenylephrine (PE) (1 nm to 3 μm) was obtained. To evaluate the vasodilatory response, a single concentration of PE (100 μm) was used to develop similar tension values in all groups, and, subsequently, cumulative concentrations of either ACh (1 nm to 3 μm) or sodium nitroprusside (SNP) (1 nm to 3 μm) were added to the tissue bath to induce endothelial cell-dependent or endothelial cell-independent relaxation, respectively. At least two aortic rings were assayed from each animal for multiple compounds. Drugs were added with an interval of approximately 1 min between them. All aortas were studied with intact endothelium. Data were collected and analyzed using PowerLab software (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO).

Quantification of NO metabolites in plasma

Quantitative measurements of plasma nitrite (NO2-) and nitrate (NO3-) were performed as an index of local NO production according to the procedure outlined by Van Der Vliet et al. (18). Briefly, this procedure is based on acidic reduction of NO2 and NO3 to NO by vanadium (III) and purging of NO with helium into an Antek 7020 NO detector (Antek Instruments, Houston, TX). At room temperature, vanadium (III) only reduces NO2, whereas NO3 and other redox forms of NO such as S-nitrosothiols are also reduced after the solution is heated to 80–90 C, so that both NO2 and total nitrogen oxides (primarily NO3) can be measured. Data were quantified by comparison with standard solutions of NO2 and NO3. Detection limits for NO metabolites in plasma samples are 0.25 μm.

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed and analyzed as previously described (19). Briefly, aortic tissue was homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer [50 mm Tris (pH 7.4), 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 0.2% sodium deoxycholate, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm EGTA, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, and 1 mm NaF]. Aortic homogenates were then centrifuged at 2300 × g for 5 min to remove insoluble material. Primary antibodies were all rabbit polyclonal antibodies, and dilutions were as follows: 1:500 anti-eNOS, 1:500 and 1:250 inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), 1:250 anti-p50, 1:500 phospho (p)-vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) (Ser239), and 1:1,000 total VASP (Cell Signaling Technologies, Beverly, MA); 1:100 anti-α1 and 1:500 anti-sGC β1 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI); 1:500 anti-cytidine-cytidine-adenosine-adenosine-thymidine (CCAAT)/enhancer-binding protein (BioLegend, San Diego, CA); 1:10,000 β-actin (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO); 1;10,000 α-actin (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO); and 1:200 anti-Smooth Muscle Myosin (Biomedical Technologies, Inc., Stoughton, MA). Membranes were washed and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000) in 2% milk-Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (Amersham Biosciences Inc., Piscataway, NJ). Membranes were washed, incubated with a chemiluminescent substrate (West Pico; Pierce, Rockford, IL), and visualized using CL-Xposure Film (Fuji Photo Film, Düsseldorf, Germany). Densitometry was performed using a Hewlett-Packard Scanjet model G3010 (Hewlett-Packard Co., Palo Alto, CA) and Un-Scan-It software (Silk Scientific, Inc., Orem, UT). Relative intensities for eNOS, α1 and sGC β1 were normalized to β-actin, as a loading control. P-VASP (Ser 239) was normalized to total VASP.

Real-time PCR

Frozen tissue was ground in liquid nitrogen with a porcelain mortar and pestle. Total RNA was extracted by the modified guanidine isothiocyanate method (20). After isolation, RNA was processed with the RNeasy mini kit, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (QIAGEN, Inc., Valencia, CA). First-strand cDNA was generated using 2 μg total RNA and the high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Primers were purchased from SuperArray Technologies (Frederick, MD).

PCRs were set up in 25-μl vol, consisting of 2.5 μl cDNA, 0.5 μl forward and 0.5 μl reverse 10 μm primers, 12.5 μl SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), and 9 μl ribonuclease-deoxyribonuclease free water. For all primer sets, a denaturing step at 94 C for 10 min was followed by 40 cycles of denaturing at 94 C for 30 sec, annealing at 60 C for 45 sec, and 72 C extension for 30 sec. Real-time PCR was performed using an AbiPrism 7900HT Sequence Detector, and data were analyzed using SDS 2.1 software (Applied Biosystems). The relative concentration of the corresponding mRNA was measured as the number of cycles of PCR required to reach threshold fluorescence and normalized against that of an internal standard gene (β-actin).

Drugs and chemicals

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich except for Bay 41-2272 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA).

Statistical analysis

Results from vascular contraction-relaxation studies were analyzed by both a two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test to compare individual means and a sum of squares F test for whole curve comparison (GraphPad Prism, version 4.0b; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). IC50 was calculated from individual concentration-response curves after fitting the data to sigmoidal dose response curves (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). Western blot and NO metabolite data were analyzed by a one-way ANOVA or ANOVA on Ranks, where appropriate, followed by a Student-Newman-Keuls test. Data are presented as mean + sem. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

ovx rats had plasma E2 levels of 27.3 ± 4.8 pg/ml, whereas E2 replacement resulted in levels of 59.48 ± 9.6 pg/ml. Old shams had E2 levels of 58.0 ± 8.1 pg/ml. Body weight among groups did not differ significantly (adult ovx 225.6 ± 15.6, adult ovx plus E2 196.2 + 12.6, old ovx 269.2 + 6.9, old ovx plus E2 246.6 + 13.5 g), as would be expected with Norway Brown rats.

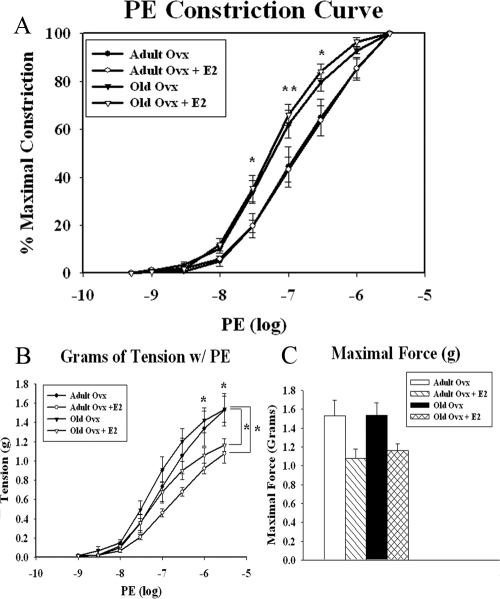

Aging and the loss of estrogens lead to enhanced vasoconstriction

To determine the effects of aging and withdrawal of estrogens on both the endothelium and the surrounding smooth muscle, we measured the contractile-relaxant responses of isolated thoracic aortic segments. Data are summarized in Fig. 1A (adult ovx n = 5, adult ovx plus E2 n = 5, old ovx n = 4, and old ovx plus E2 n = 4). When normalized to maximal constriction, aged animals had increased vasomotor responses to l-PE (P < 0.05), specifically at 30, 100, and 300 nm. E2 replacement did not affect the normalized vasoconstrictor response in either the adult or old aortas (Fig. 1A). Although vasomotor responses are usually presented as normalized values, we also analyzed changes in absolute grams of tension developed in each group. Both adult and old ovx animals had greater tension development, specifically at 1 and 3 μm compared with similarly aged ovx rats with E2 replacement, indicating increased vessel tension after ovariectomy (Fig. 1B). Maximal tension generated per aortic ring was measured in response to 3 μm PE. Although there was a trend for adult and old ovx animals to have slightly higher maximal tension with PE administration as seen in Fig. 1C, this was not statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Effect of aging and/or E2 withdrawal on the aortic constriction response to PE. A, Normalized concentration-response curves to PE in isolated aortic rings of adult and old ovx rats with and without E2 replacement. B, Overall tension (grams) in PE precontracted rings. C, Maximal tension developed in response to 3 μm PE. Each curve represents the mean + sem (n = 4–5 per group).*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

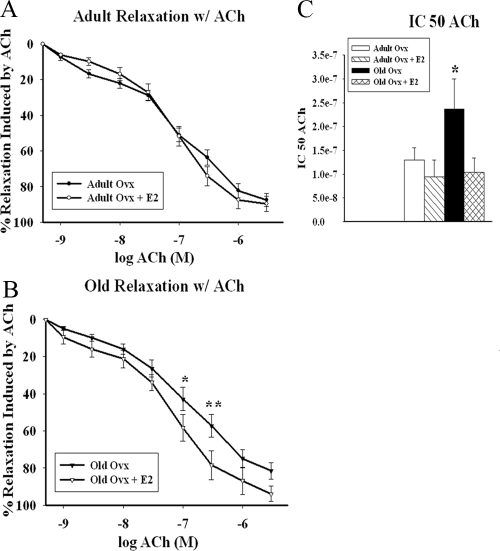

Aging plus estrogen deficiency impairs ACh-induced relaxation

To investigate the effect of aging vs. estrogen loss on vasorelaxation, we tested vasomotor responses to ACh (1 × 10−9 m to 3 × 10−6 m). We observed no differences between adult ovx and adult ovx plus E2 in response to ACh, as seen in Fig. 2A (adult ovx n = 7, adult ovx plus E2 n = 5, old ovx n = 8, and old ovx plus E2 n = 7). However, old ovx demonstrated impaired relaxation in response to ACh in comparison to old ovx plus E2 at 100 and 300 nm (P < 0.05; Fig. 2B). Absolute grams of tension were also analyzed in all groups (data not shown) and had the same result, that there was no difference between adult ovx and adult ovx plus E2, whereas old ovx had greater tension vs. old ovx plus E2 by whole curve comparison (P < 0.05). The IC50 (Fig. 2C) was higher in the old ovx vs. all others (adult ovx 1.3e−7 ± 2.6e−8 m, adult ovx plus E2 9.5e−8 ± 3.5e−8 m, old ovx 2.4e−7 ± 6.3e−8 m, old ovx plus E2 1.0e−8 ± 2.9e−8; P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Vasodilatory effects of ACh. Concentration-response curves to ACh were obtained in PE precontracted isolated aortic rings from adult (A) and old (B) ovx rats with and without E2. C, IC50 values for ACh-induced vasorelaxation in isolated aortic rings precontracted with PE (100 μm). Each curve represents the mean + sem (n = 5–8 per group). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Aging plus estrogen deficiency necessary for endothelial-independent impaired relaxation

To identify whether the dysfunction was occurring in the endothelium or smooth muscle, we repeated the vasorelaxation experiments using SNP (1e−9 to 3e−6 m) as an NO donor. Adult ovx and adult ovx plus E2 showed no differences in relaxation (Fig. 3A). As seen in Fig. 3B, old ovx exhibited impaired relaxation in response to SNP at 1 and 3 nm (P < 0.05), indicating that the vascular dysfunction was endothelium independent and was occurring within the smooth muscle (adult ovx n = 5, adult ovx plus E2 n = 4, old ovx n = 6, and old ovx plus E2 n = 6). Normalized and absolute tension curves (data not shown) demonstrated impaired relaxation for old ovx in comparison to old ovx plus E2 by whole curve comparison (P < 0.05), whereas adult and adult ovx plus E2 did not differ. The SNP IC50 (Fig. 3C) was higher in the old ovx vs. all others (adult ovx 1.5e−9 ± 4.3e−10 m, adult ovx plus E2 1.2e−9 ± 3.6e−11 m, old ovx 2.9e−9 ± 5.2e−10 m, old ovx plus E2 1.8e−9 ± 2.3e−10; P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Vasodilatory effects of SNP. Concentration-response curves to SNP were obtained in PE precontracted isolated aortic rings from adult (A) and old (B) ovx rats with and without E2. C, IC50 values for SNP-induced vasorelaxation in isolated aortic rings precontracted with PE (100 μm). Each curve represents the mean + sem (n = 4–6 per group). *, P < 0.05. ***, P < 0.001.

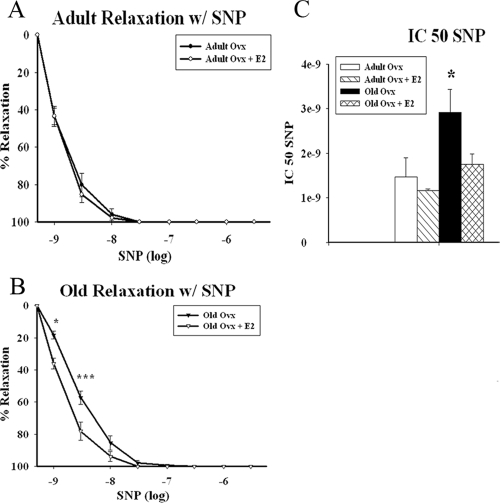

NOS expression and systemic NO production

To determine whether changes in the signaling cascade proteins were the reason for impaired relaxation, we measured expression of the NOS isoforms, eNOS and iNOS, and circulating NO levels. Aging and/or E2 replacement did not affect basal protein expression of eNOS or iNOS among the four groups [P = not significant (ns)], as shown in Fig. 4, A and B. Expression of the NOS isoform, neuronal NOS, could not be detected, although our internal control was detected. To corroborate these findings, we quantified levels of circulating NO metabolites in the plasma of the animals. As shown in Fig. 4C, circulating levels of NO did not differ among groups (adult ovx 22.4 ± 2.0, adult ovx plus E2 22.5 ± 2.6, old ovx 21.6 ± 1.7, and old ovx plus E2 23.5 ± 3.5 μm; P = ns), which is consistent with the protein results.

Figure 4.

Aortic NOS expression is unchanged with age and/or E2 replacement. A, Graph summarizes eNOS expression in aortic tissue from the respective groups. Expression was normalized to β-actin (n = 4–5 per group) (P = ns). Representative Westerns in lower panel showing eNOS and β-actin on the same blot. B, Graph summarizes iNOS expression in aortic tissue from respective groups. Expression was normalized to β-actin. Representative Westerns in lower panel showing iNOS and β-actin on the same blot. Lanes for both blots: 1, adult ovx; 2, adult ovx plus E2; 3, old ovx; and 4, old ovx plus E2 (n = 4 per group) (P = ns). C, Plasma concentration of the circulating NO metabolites, NO2 and NO3 (n = 8–12 per group) (P = ns).

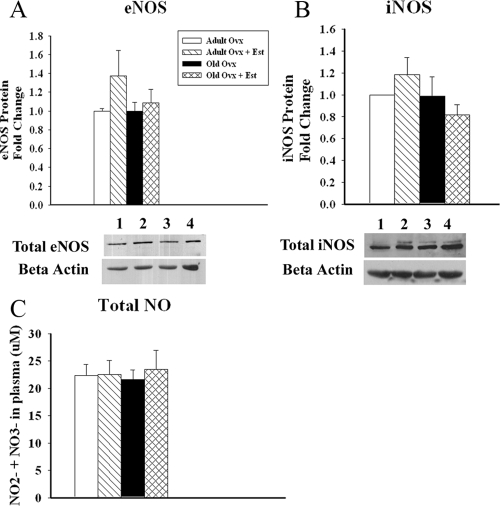

Aging and withdrawal of estrogens impair response of VSM to NO

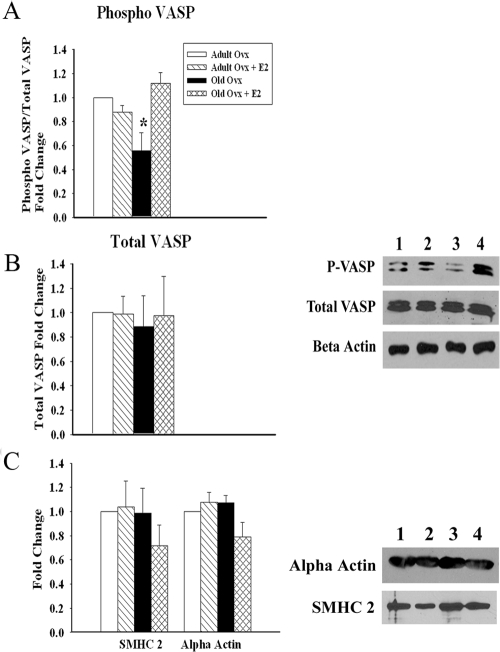

Because old ovx had impaired relaxation in response to SNP, we hypothesized that old ovx had abnormalities in the signaling cascade downstream of eNOS. We examined expression of the NO receptor sGC. As shown in Fig. 5, A and B, mRNA and protein levels of both the sGC α1 (P < 0.05) and sGC β1-isoforms (P < 0.05) were decreased in old ovx compared with all other groups. In addition, we investigated whether VASP, a downstream target of sGC and a biochemical endpoint in the NO signaling pathway, was activated in the aortas of the aforementioned groups. Phospho-serine 239, the major phosphorylation site activated in response to PKG activation, was examined. In support of the sGC data, we found decreased p-VASP in old ovx compared with all other groups (P < 0.05), whereas no differences were observed in the total levels of VASP (P = ns; Fig 6, A and B). To assess whether changes in VSM cell phenotype could be a cause of the impaired sGC function, we measured expression of α-actin and smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (SMHC). No changes were detected in either α-actin or SMHC expression among the groups (Fig. 6C).

Figure 5.

Aortic sGC expression decreases with age and E2 withdrawal. A, sGC mRNA was analyzed by real-time PCR of total aortic RNA. Values for sGC α1 and β1 mRNA were normalized to β-actin. B, Graph summarizes levels of sGC α1 and β1 from the lysates of total aortic tissue by Western blotting. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Representative Westerns in the bottom panel show sGC α1 and β1 and β-actin on same blot (n = 4–6 per group). *, P < 0.05.

Figure 6.

Downstream NO cascades are decreased with age and E2 withdrawal, independent of phenotypical changes. A, Graph summarizes phosphorylation of VASP (Ser 239) in the four groups. Values were normalized to total VASP. A representative blot developed sequentially for p-VASP, total VASP, and β-actin is shown on the right. B, Graph summarizes total VASP in the four groups. Values were normalized to β-actin. C, Graph summarizes expression of SMHC 2 and smooth muscle actin in the four groups. Values were normalized to β-actin. A representative blot for SMHC 2 and smooth muscle α-actin is shown on the right. Lanes: 1, adult ovx; 2, adult ovx plus E2; 3, old ovx; and 4, old ovx plus E2 (n = 4–5 per group). *, P < 0.05.

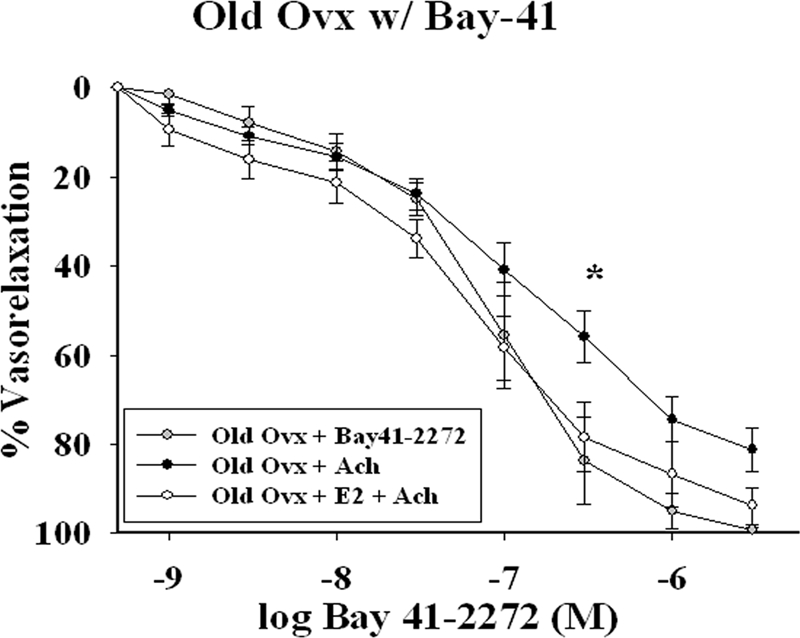

BAY 41-2278 rescues smooth muscle function in old ovx rats

To assess whether the smooth muscle abnormalities can be corrected with an sGC agonist, we compared vasorelaxation in the old ovx in the presence of BAY 41-2272 (an sGC α-agonist; Calbiochem) from 1 × 10−9 m to 3 × 10−6 m. As shown in Fig. 7, stimulation of the sGC receptor restores the vasorelaxation response in old ovx plus ACh to that seen in old ovx plus E2 plus ACh (P < 0.05; old ovx n = 8, old ovx plus Bay-41 n = 4, and old ovx plus E2 n = 7).

Figure 7.

Vasodilatory effects of the sGC-α agonist, Bay 41-2272. Concentration response to Bay 41-2272 (0.1 nm-3 μm) was studied in PE (50–150 nm) precontracted aortic rings of old ovx without E2. Results were compared with responses of old ovx with ACh and old ovx plus E2 with ACh. Each curve represents the mean + sem (n = 4–8 per group). *, P < 0.05.

Discussion

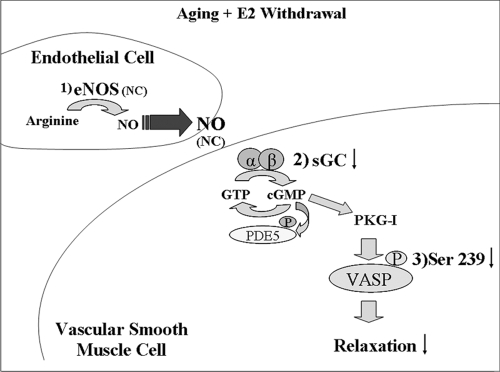

Our results show that aging in combination with the withdrawal of estrogens (menopause) leads to decreased vasorelaxation in response to ACh and SNP. The effected cascades are summarized in Fig. 8. Vasoconstriction is increased in both adult and old ovx animals in response to PE, and is decreased by E2 replacement. Levels of eNOS and iNOS did not differ among the groups, nor did total NO2 plus NO3 level, indicating that the abnormal relaxation was secondary to VSM dysfunction. Old ovx exhibited decreased expression of both the α1 and β1 subunits of sGC. Immediate E2 replacement in the aged ovx prevented both the depressed vasorelaxation and the loss of the sGC expression.

Figure 8.

Changes in NO signaling cascade with aging and the loss of estrogens. 1, NO is synthesized in the endothelium by eNOS using l-arginine as a substrate, where it then diffuses into the VSM. 2, Within the VSM, NO binds to sGC, which consists of two subunits, α and β. sGC catalyzes the conversion GTP to cyclic GMP. Cyclic GMP has multiple effects, which include: activation of phosphodiesterases (PDE), activation of cyclic GMP dependant ion channels. 3, Activation of cyclic GMP dependant protein kinase G (PKG). VASP is then phosphorylated at serine 239 by PKG. VASP is an established biochemical endpoint in the NO/cyclic GMP pathway in VSM, and is an index of defects in NO signaling and/or endothelial dysfunction. Aging combined with ovariectomy depressed sGC α1 and β1 expression, resulting in decreased phosphorylation of VASP, and consequently decreased relaxation in response to NO. E2 replacement blocked these changes. NC, No change; P, phosphorylation; PDE5, phosphodiesterose-5.

In the current study, we examined changes in vascular function in adult and old ovx female Norway Brown rats with and without E2 replacement. The Norway Brown rat is a standard model of aging, allowing the selective study of aging independent of obesity. The purpose of our study was to investigate the effects of E2 replacement vs. aging in a menopausal model. Female rats do not undergo menopause but, instead, enter a stage of slowly declining ovarian function as they age. Intact, cycling animals display wide variations in estrogen levels during their cycles and as they age. We carefully considered the use of an intact control but thought there was no optimal point in the 4-d rat cycle that would be a good control in the adult rats, and in the aging rats, the sustained estrus with slowly declining levels of estrogens over time did not represent a useful control. The addition of these multiple groups would complicate analysis and make it more difficult to discern the effect of E2 replacement after ovx, which was the principle question of interest. Therefore, we focused on adult and old rats with and without E2 replacement after ovariectomy.

Previously, we have observed in the hearts of female Sprague Dawley rats that a period of 9 wk was necessary for levels of the cardio-protective heat shock protein 72 to decrease to levels seen in age-matched males (16). Although clinical studies have demonstrated that the withdrawal of estrogens after 3 wk leads to increased blood pressure and decreases in forearm blood flow (21,22), we believe that the acute loss of estrogens is not sufficient to induce the full cascade of changes that occur with loss of estrogen. An additional strength of our study design is the use of both adult and aged rats. Much of the literature on estrogens has used adolescent models. Although their findings may be of importance, the results may not be applicable to many pathological conditions that occur with aging.

Increased vascular stiffness during aging can partly be attributed to enhanced sensitivity to vasoconstrictive agents. In mesenteric arteries of female Sprague Dawley rats, loss of estrogens has led to increased PE induced contractions through the up-regulation of the angiotensin II type I receptor (AT1R), which can be reduced by E2 supplementation (23). In contrast, others have found that E2 status did not affect constriction to PE but did enhance sensitivity to angiotensin II in thoracic aortic segments (24). We found in the descending thoracic aorta of Norway Brown rats that ovariectomy led to increased response to PE in both adult and old rats. Although ovariectomy increased vascular tension, aging by itself increased the constrictor response to PE independent of E2 status.

In males, aging may decrease bioavailability of NO through decreased expression of eNOS, as found in aged Sprague Dawley rats (25,26), though this model has concomitant obesity. It has also been reported that high-passage human umbilical vein endothelial cells have decreased activation of eNOS, along with decreased activation and expression of associated proteins needed for NO generation, such as AKT (8). Recent work suggests that along with decreased eNOS expression, in males aging leads to increased superoxide production, arginase I activity, and endothelial susceptibility to apoptotic stimuli, all which may lead to decreased bioavailability of NO (27,28,29). However, it is not known whether these same changes apply to females or the role of estrogens. In the current study in female rats, neither aging nor ovariectomy affected eNOS expression.

We found no difference in vascular relaxation in response to ACh in adult female rats with and without E2 supplementation, indicating no change in NO production by the endothelium. However, in aged female rats, ovariectomy impaired relaxation in response to ACh, which was prevented by immediate E2 replacement. As discussed previously, eNOS expression and NO levels did not change, indicating that the abnormal relaxation in the aged ovx was due to either changes in the VSM or extracellular matrix. This was confirmed by the failure of the NO donor, SNP, to correct the abnormal relaxation seen in the old ovx group.

Although NO levels did not differ among the groups, both sGC α1 and β1 were decreased in old ovx compared with old ovx plus E2, indicating that the reduced response to NO in old ovx was due to decreased receptor expression, not to deficits in NO generation. Similarly, we have found, as part of a microarray study of gene changes in the heart of aging female Norway Brown rats, that sGC α and β are decreased with ovariectomy (unpublished observations), whereas adult female Sprague Dawley rats showed no variation with ovariectomy (30).

Aging with concomitant hypertension has led to decreased expression of the sGC α and/or β-isoforms in the aortas of male spontaneously hypertensive rats and Wistar-Kyoto rats (9,31). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that demonstrates that chronic E2 replacement can preserve sGC expression and prevent impaired relaxation in aged ovx female rats. Previous studies have focused on the acute effects of E2 treatment on sGC function in female rat uterine and pituitary tissues, not on vascular tissue (32,33). The reduction in sGC α1 and β1 in old ovx was accompanied by decreased downstream activation of VASP by phosphorylation at serine 239, verifying reduced activation of the NO signaling cascade in old ovx without E2 replacement. A limited number of old sham aortas were examined, and found to have no change in total eNOS, and similar sGC α1 and β1 expression to that seen in old ovx plus E2 (data not shown). This supports our findings that the combination of aging and E2 withdrawal lead to the aforementioned changes.

The exact cause of the down-regulation of sGC in our model remains unknown, but in other studies decreased expression has been linked to increased endotoxin and cytokine levels (34). Although we found no difference in circulating levels of IL1-β, IL-6, or TNF-α in plasma of young and old with and without E2 supplementation (data not shown), localized inflammation could be one mechanism for the down-regulation of the sGC isoforms. Previous studies suggest that E2 replacement can reduce proinflammatory cytokine levels induced by ovariectomy; however, some controversy exists as to whether these changes are seen across all menopausal models with HRT (35,36). The transcription factors nuclear factor κB and CCAAT-binding factor have also negatively regulated sGC α1 and β1 expression by binding to the promoter site (37,38). In our model we did could not detect expression of the either p50 or CCAAT-binding factor in any of the groups tested. Further work needs to be done to determine how sGC α1 and β1 expression is being down-regulated. To exclude phenotypical changes impairing sGC expression, we measured smooth muscle heavy chain-2 and smooth muscle α-actin expression. No changes in expression were detected for either protein in the four groups.

Changes in the extracellular matrix can also affect vessel stiffness. Studies in aging male rats have shown increased collagen content and cross-linking, along with increases in fibronectin, and decreases in elastin, due to calcification and fragmentation (39). Recently, Qui et al.(40) found that aortic stiffness increased with age, but to a greater degree in aged male than aged female premenopausal and perimenopausal monkeys. Decreases in collagen type 8 and elastin were observed only in aged males and likely accounted for the greater increase in aortic stiffness compared with aged females (40). Further work needs to be done to determine whether aging and chronic loss of estrogens in females lead to changes in extracellular matrix proteins, such as collagen, fibronectin, and elastin.

Treatment of hypertension in postmenopausal women has focused on vasodilators. In the current study, the sGC receptor was reduced by the combination of ovariectomy and aging, and this was accompanied by reduction in vascular relaxation in response to ACh and SNP. The impairment of vasorelaxation due to decreased expression of sGC is a potential target in the treatment of hypertension in postmenopausal women (41). Bay 41-2272, an agonist of sGC, which binds to the regulatory site of sGC α and stimulates the enzyme synergistically with NO, restored normal relaxation. sGC activators, such as Bay 41-2272, are a possible new therapeutic approach for elderly female patients. Recent work has shown that Bay 41-2272 can reduce systemic arterial and pulmonary hypertension in rat models, and also can inhibit leukocyte adhesion in vivo (42). Thus, this compound shows promise as a new therapy to treat hypertension in postmenopausal women.

In conclusion, estrogens are a powerful compound with a plethora of effects. Further work is needed to understand the effects of aging vs. the withdrawal of estrogens in the aging female. The availability of an increasing number of synthetic estrogen receptor modulators raises the possibility of eventually being able to exploit the positive properties of estrogen without the deleterious effects.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AG19327 (to A.A.K.), the Department of Veterans Affairs (to A.A.K.), and the American Heart Association Western States Affiliate (to J.P.S.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online September 11, 2008

Abbreviations: ACh, Acetylcholine; CCAAT, cytidine-cytidine-adenosine-adenosine-thymidine; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; E2, 17β-estradiol; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; NO3, nitrate; NO, nitric oxide; NO2, nitrite; ovx, ovariectomized; ns, not significant; PE, phenylephrine; PKG, protein kinase G; sGC, soluble guanylyl cyclase; SMHC, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain; SNP, sodium nitroprusside; VASP, vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein; VSM, vascular smooth muscle.

References

- Stevenson JC 2000 Cardiovascular effects of oestrogens. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 74:387–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson HD, Humphrey LL, Nygren P, Teutsch SM, Allan JD 2002 Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy: scientific review. JAMA 288:872–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turgeon JL, McDonnell DP, Martin KA, Wise PM 2004 Hormone therapy: physiological complexity belies therapeutic simplicity. Science 304: 1269–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JE, Wu L, Barad D, Barnabei VM, Ko M, LaCroix AZ, Margolis KL, Stefanick ML 2007 Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. JAMA [Erratum (2008) 299:1426] 297:1465–1477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari AU, Radaelli A, Centola M 2003 Invited review: aging and the cardiovascular system. J Appl Physiol 95:2591–2597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei S, Virdis A, Mattei P, Ghiadoni L, Gennari A, Fasolo CB, Sudano I, Salvetti A 1995 Aging and endothelial function in normotensive subjects and patients with essential hypertension. Circulation 91:1981–1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TC, Yen MH, Li CY, Ding YA 1998 Alterations of nitric oxide synthase expression with aging and hypertension in rats. Hypertension 31:643–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruetten H, Zabel U, Linz W, Schmidt HH 1999 Downregulation of soluble guanylyl cyclase in young and aging spontaneously hypertensive rats. Circ Res 85:534–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloss S, Bouloumie A, Mulsch A 2000 Aging and chronic hypertension decrease expression of rat aortic soluble guanylyl cyclase. Hypertension 35(1 Pt 1):43–47 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CS, Liu X, Tu R, Chow S, Lue TF 2001 Age-related decrease of protein kinase G activation in vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 287:244–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Yuhanna IS, Galcheva-Gargova Z, Karas RH, Mendelsohn ME, Shaul PW 1999 Estrogen receptor α mediates the nongenomic activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by estrogen. J Clin Invest 103:401–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes MP, Sinha D, Russell KS, Collinge M, Fulton D, Morales-Ruiz M, Sessa WC, Bender JR 2000 Membrane estrogen receptor engagement activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase via the PI3-kinase-Akt pathway in human endothelial cells. Circ Res 87:677–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Lu X, Ren H, Levin ER, Kassab GS 2006 Estrogen modulates the mechanical homeostasis of mouse arterial vessels through nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290:H1788–H1797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrel PM 1999 The differential effects of oestrogens and progestins on vascular tone. Hum Reprod Update 5:205–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RE 2002 Estrogen and vascular function. Vascul Pharmacol 38:73–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss MR, Stallone JN, Li M, Cornelussen RN, Knuefermann P, Knowlton AA 2003 Gender differences in the expression of heat shock proteins: the effect of estrogen. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285:H687–H692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiserich JP, Baldus S, Brennan ML, Ma W, Zhang C, Tousson A, Castro L, Lusis AJ, Nauseef WM, White CR, Freeman BA 2002 Myeloperoxidase, a leukocyte-derived vascular NO oxidase. Science 296:2391–2394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Vliet A, Nguyen MN, Shigenaga MK, Eiserich JP, Marelich GP, Cross CE 2000 Myeloperoxidase and protein oxidation in cystic fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 279:L537–L546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss MR, Gupta S, Stice JP, Baumgarten G, Lu L, Tristan JM, Knowlton AA 2005 Effect of mutation of amino acids 246–251 (KRKHKK) in HSP72 on protein synthesis and recovery from hypoxic injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289:H2519–H2525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N 2006 The single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction: twenty-something years on. Nat Protoc 1:581–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner DZ, Personius BE, Andrews TC 1999 Effects of withdrawal of chronic estrogen therapy on brachial artery vasoreactivity in women with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 83:247–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashi Y, Sanada M, Sasaki S, Nakagawa K, Goto C, Matsuura H, Ohama K, Chayama K, Oshima T 2001 Effect of estrogen replacement therapy on endothelial function in peripheral resistance arteries in normotensive and hypertensive postmenopausal women. Hypertension 37:651–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenas IA, Armstrong SJ, Xu Y, Davidge ST 2006 Tumor necrosis factor-α and vascular angiotensin II in estrogen-deficient rats. Hypertension 48:497–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassmann S, Baumer AT, Strehlow K, van Eickels M, Grohe C, Ahlbory K, Rosen R, Bohm M, Nickenig G 2001 Endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress during estrogen deficiency in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Circulation 103:435–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long DA, Newaz MA, Prabhakar SS, Price KL, Truong LD, Feng L, Mu W, Oyekan AO, Johnson RJ 2005 Loss of nitric oxide and endothelial-derived hyperpolarizing factor-mediated responses in aging. Kidney Int 68: 2154–2163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucy KG, Ryoo S, Benjo A, Lim HK, Gupta G, Sohi JS, Elser J, Aon MA, Nyhan D, Shoukas AA, Berkowitz DE 2006 Impaired shear stress-induced nitric oxide production through decreased NOS phosphorylation contributes to age-related vascular stiffness. J Appl Physiol 101:1751–1759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson A, Yan C, Gao Q, Rincon-Skinner T, Rivera A, Edwards J, Huang A, Kaley G, Sun D 2007 Aging enhances pressure-induced arterial superoxide formation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293:H1344–H1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AR, Ryoo S, Li D, Champion HC, Steppan J, Wang D, Nyhan D, Shoukas AA, Hare JM, Berkowitz DE 2006 Knockdown of arginase I restores NO signaling in the vasculature of old rats. Hypertension 47:245–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann J, Haendeler J, Aicher A, Rossig L, Vasa M, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S 2001 Aging enhances the sensitivity of endothelial cells toward apoptotic stimuli: important role of nitric oxide. Circ Res 89:709–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton KL, Lin L, Wang Y, Knowlton AA 2008 Effect of ovariectomy on cardiac gene expression: inflammation and changes in SOCS gene expression. Physiol Genomics 32:254–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Daum G, Fischer JW, Hawkins S, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Gabbiani G, Clowes AW 2000 Loss of expression of the β subunit of soluble guanylyl cyclase prevents nitric oxide-mediated inhibition of DNA synthesis in smooth muscle cells of old rats. Circ Res 86:520–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumenacker JS, Hyder SM, Murad F 2001 Estradiol rapidly inhibits soluble guanylyl cyclase expression in rat uterus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:717–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabilla JP, Diaz Mdel C, Machiavelli LI, Poliandri AH, Quinteros FA, Lasaga M, Duvilanski BH 2006 17β-Estradiol modifies nitric oxide-sensitive guanylyl cyclase expression and down-regulates its activity in rat anterior pituitary gland. Endocrinology 147:4311–4318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friebe A, Koesling D 2003 Regulation of nitric oxide-sensitive guanylyl cyclase. Circ Res 93:96–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller ET, Zhang J, Yao Z, Qi Y 2001 The impact of chronic estrogen deprivation on immunologic parameters in the ovariectomized rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) model of menopause. J Reprod Immunol 50:41–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zegura B, Keber I, Sebestjen M, Koenig W 2003 Double blind, randomized study of estradiol replacement therapy on markers of inflammation, coagulation and fibrinolysis. Atherosclerosis 168:123–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marro ML, Peiro C, Panayiotou CM, Baliga RS, Meurer S, Schmidt HH, Hobbs AJ 2008 Characterization of the human α1 β1 soluble guanylyl cyclase promoter: key role for NF-κB(p50) and CCAAT-binding factors in regulating expression of the nitric oxide receptor. J Biol Chem 283:20027–20036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Padron RI, Pham SM, Pang M, Li S, Aitouche A 2004 Molecular dissection of mouse soluble guanylyl cyclase α1 promoter. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 314:208–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatta EG 2003 Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: part III: cellular and molecular clues to heart and arterial aging. Circulation 107:490–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu H, Depre C, Ghosh K, Resuello RG, Natividad FF, Rossi F, Peppas A, Shen YT, Vatner DE, Vatner SF 2007 Mechanism of gender-specific differences in aortic stiffness with aging in nonhuman primates. Circulation 116:669–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolin MS 2005 Loss of vascular regulation by soluble guanylate cyclase is emerging as a key target of the hypertensive disease process. Hypertension 45:1068–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerrigter G, Burnett Jr JC 2007 Nitric oxide-independent stimulation of soluble guanylate cyclase with BAY 41-2272 in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Drug Rev 25:30–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]