Summary

doublesex (dsx) encodes sex-specific transcription factors (DSXF in females and DSXM in males) that act at the bottom of the Drosophila somatic sex determination hierarchy. dsx, which is conserved among diverse taxa, is responsible for directing all aspects of Drosophila somatic sexual differentiation outside the nervous system. The role of dsx in the nervous system remains minimally understood. Here, the mechanisms by which DSX acts to establish dimorphism in the central nervous system were examined. This study shows that the number of DSX-expressing cells in the central nervous system is sexually dimorphic during both pupal and adult stages. Additionally, the number of DSX-expressing cells depends on both the amount of DSX and the isoform present. One cluster of DSX-expressing neurons in the ventral nerve cord undergoes female-specific cell death that is DSXF-dependent. Another DSX-expressing cluster in the posterior brain undergoes more cell divisions in males than in females. Additionally, early in development, DSXM is present in a portion of the neural circuitry in which the male-specific product of fruitless (fru) is produced, in a region that has been shown to be critical for sex-specific behaviors. This study demonstrates that DSXM and FRUM expression patterns are established independent of each other in the regions of the central nervous system examined. In addition to the known role of dsx in establishing sexual dimorphism outside the central nervous system, the results demonstrate that DSX establishes sex-specific differences in neural circuitry by regulating the number of neurons using distinct mechanisms.

Keywords: sexual development, sex hierarchy, nervous system

Introduction

Sex–specific differences in neural circuitry contribute to differences in male and female reproductive behaviors (reviewed in Ball and Balthazart, 2004; Simerly, 2002). In Drosophila, sex-specific reproductive behaviors are specified through a genetic regulatory cascade called the sex determination hierarchy (reviewed in Manoli et al., 2006). This hierarchy consists of a pre-mRNA splicing cascade that culminates in the production of sex-specific transcription factors. doublesex (dsx) is at the bottom of one branch of the sex hierarchy and has been shown to specify all aspects of sex-specific development outside the nervous system (Hildreth, 1965). fruitless (fru) is at the bottom of another branch of the sex hierarchy and has been shown to encode male-specific transcription factors [FRUM, encoded by fru P1 transcripts; (Ryner et al., 1996)] that underlie the potential for male courtship behaviors (reviewed in Manoli et al., 2006). Recent studies have shown that both fru and dsx collaborate in the central nervous system (CNS) to bring about the potential for one step in the male courtship ritual, the production of courtship song (Rideout et al., 2007). Despite this progress, the mechanisms by which dsx establishes differences in neural circuitry are largely unknown.

dsx encodes both male (DSXM) and female (DSXF) transcription factors (reviewed in Christiansen et al., 2002). DSX isoforms share a common amino terminal region that contains the DNA binding domain, but differ in their carboxyl terminal region [Figure 1A; (Burtis and Baker, 1989)]. dsx specifies nearly all aspects of Drosophila somatic sex determination outside the nervous system, as dsx null animals display an intersexual phenotype (Hildreth, 1965). Furthermore, if DSXM is the only DSX isoform produced in chromosomally XX animals, these animals look almost identical to wild type males (hereafter called pseudomales), suggesting that dsx is sufficient to specify most aspects of sex-specific somatic development (Duncan and Kaufman, 1975).

Figure 1. DSX expression is sexually dimorphic.

(A) Schematic of sex-specific DSX isoform The common region includes the DNA binding domain (region 1). The sex-specific regions (region 2) are 152 and 30 amino acids, in the male and female isoforms, respectively (Burtis and Baker, 1989). The polyclonal antibody was generated against amino acids 290–398 (bar). (B) Schematic of posterior surface of adult male CNS, indicating where DSX-expressing clusters pC1 (blue) and pC2 (white) reside in the brain. (C) Schematic of anterior surface of adult male CNS, indicating where clusters of DSX-expressing cells aDN, SN, and SLN reside in the brain, and TN1 (purple) and TN2 cells reside in the VNC. DSX-expressing cell groups are indicated by dots on both sides of the schematic, but only labeled on the left, as DSX-expressing cells are bilaterally symmetrical. (D) Schematic of male white-pre-pupal CNS, indicating where clusters of DSX-expressing cells reside (white). DSX-expressing cells in the posterior midbrain (E–J) and ventral nerve cord (K–N) in 0–24 hour adults (E, F, K and L), 48-hour pupae (G, H, M and N), and 0-hour white pre-pupae (I and J; only one hemisegment is shown for each brain). Arrow and arrowhead (E) indicates pC2 and pC1 cluster, respectively. Arrowheads in (K) and (M) indicate TN1 region. Magnified DSX-expressing cells in the TN1 region of males (O) and females (P). Male and female genotypes are indicated by XY and XX, respectively. 20X confocal sections (~1 µm thick) are shown.

The role of dsx in directing sex-specific nervous system development and physiology has been more difficult to examine, given that there are no overt morphological differences between the sexes in the nervous system. Behavioral analyses on dsx mutants provide conflicting results. Initially, it was thought that dsx was unable to direct the nervous system to a male fate, given the observation that pseudomales do not display any male-specific behaviors (Taylor et al., 1994). However, it was also shown that dsx null males perform courtship in a quantitatively subnormal manner (Villella and Hall, 1996), and a population of abdominal neuroblasts undergoes more dsx-dependent divisions in males (Taylor and Truman, 1992). Recent studies suggest a key role for dsx in specifying reproductive behaviors, including a demonstration that DSXM and FRUM are co-expressed in subsets of neurons in the CNS (Billeter et al., 2006; Rideout et al., 2007), that DSX and FRU collaborate to bring about the potential for wing song (Rideout et al., 2007), and that animals that are transheterozygous for dsx and fru P1 alleles show a reduction in male courtship behaviors (Shirangi et al., 2006).

DSX is expressed in a sexually dimorphic pattern in the adult CNS (Lee et al., 2002). In this study, the mechanisms responsible for generating this dimorphism were determined. DSX expression was examined during metamorphosis, in both males and females and the pattern is very similar to that which was previously described, with some differences (Lee et al., 2002). Additionally, this study shows that the DSX-expressing cell number is established during a small window of time during early stages of metamorphosis. DSX directs the number of DSX-expressing cells in the CNS in an isoform-specific and dose-dependent manner. The sexually dimorphic number of DSX-expressing cells in one region of the ventral nerve cord (VNC) is a result of DSXF-dependent cell death that occurs during metamorphosis in females and not males. Additionally, a population of DSX-expressing neurons in the posterior brain of males undergoes more cell divisions than in females. Given that the sex-specific transcription factors DSXM and FRUM have overlapping expression patterns, we examine if these transcription factors are responsible for establishing differences in each other’s expression patterns in the CNS, and find that they are not inter-dependent. Furthermore, in females, overlap between DSXF and fru P1-expressing cells during development does not occur in the two regions examined that have a dimorphism of number of neurons. Taken together, this work demonstrates a role for DSX in forming sex-specific differences in cell number that underlie differences in neural circuitry in the CNS.

Materials and Methods

Generation of polyclonal antibodies specific to DSX and FRUM

We produced a recombinant glutathione S-transferase (GST) DSX fusion protein that contained ~100 amino acids that are common to both DSX isoforms, by PCR amplifying the region and cloning it into the pGEX 4T1 vector (GE Healthcare). The PCR primers used are: 5’ CTCGAGCTCTTCGATTCGATTCGCCGGGAAGCCTCTTCAAT (Xho1 site is engineered at 5’ end) and 5’ GAATTCAGGTCATCGGGAACATCGGTGATCACTAGC (EcoR1 site is engineered at 5’ end). The GST-DSX fusion protein was produced in E. coli, purified and used to immunize a rat host (Josman, Napa Valley). The serum was affinity purified on a column containing the recombinant GST-DSX fusion protein covalently coupled to amino resin (Pierce). The FRUM antibody was generated as described in Lee et al., 2000, and was shown to be specific to FRUM.

Immunohistochemistry

Whole mount immunochemistry experiments were performed as previously described (Lee et al., 2000). The primary polyclonal DSX antibody was diluted 1:50–1:100 in TNT (0.1M Tris-HCl, 0.3M NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, pH 7.4). Secondary antibodies were purchased from Molecular Probes and used at recommended dilutions. Confocal microscopy was performed on a Zeiss Pascal. ELAV antibody was obtained from the Iowa hybridoma bank. Cell counts of FRUM-expressing cells in 5–7 day old dsx null and wild type males were performed blind by two independent members of the lab.

TUNEL assay for cell death

The Apoalert DNA Fragmentation Assay kit (Clontech) was used with modifications (as described in Firth et al., 2005).

Drosophila strains

Drosophila were grown on standard media containing cornmeal, dextrose, and yeast at 25°C. The wild type strain is Canton S. The dsx null genotype is transheterozygous for the dsx alleles dsxM+R15 and dsxD+R3. Generally, flies homozygous for the ix3 allele were not viable, although a small number of homozygous ix3 flies escaped to the adult stage. The loss-of-function ix genotype used here is transheterozygous for the ix3 allele and a Df(2R)en-B deficiency. The fru P1 null genotype is transheterozygous for the fru alleles fruP14 and fru4–40. The fru-P1-GAL4 driver was previously described (Stockinger et al., 2005). The UAS-DSXF and UAS-DSXM lines were provided by Gyunghee Lee. Genotypes of transgenic flies and flies mutant for cell death effectors are described in Supplemental Table 2; briefly, they include Df(3L)XR38 and Df(3L)H99 deficiencies (referred to as XR38 and H99, respectively), described in (Peterson et al., 2002), □ amyloid protein precursor-like (appl)-Gal4, tubulin -Gal4, actin-Gal4, elav-Gal4, heat shock-Gal4, UAS-diap, and UAS-p35. With the exception of the XR38, H99, appl-Gal4, UAS-diap, and UAS-p35 strains, all were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, United States). Pupal animals were sex-sorted at the white pre-pupal stage, and then aged at 25° C.

BrdU labeling

Pupae were sex-sorted at the white pre-pupal stage and aged for eight hours. CNS tissues were dissected in cold PBS, incubated for four hours in 15 µg/ml of BrdU in PBS at room temperature, washed once in PBS, and then fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 minutes at room temperature. Samples were washed three times for five minutes in PBS, three times for five minutes in TNT, and blocked for one hour in 4% normal goat serum. To expose the BrdU antigen, samples were briefly boiled (4.5 minutes) at 100°C. Samples were washed in PBS and incubated in mouse anti-BrdU (1:200 dilution, GE Healthcare) and rat anti-DSX (1:50 dilution) in TNT overnight at 4°C on a rocker. Samples were washed six times for 15 minutes each with TNT and then incubated in secondary anti-rat and anti-mouse antibodies (Molecular Probes) diluted 1:500 in TNT overnight at 4°C. Samples were washed six times in TNT for 15 minutes each and mounted in VectaShield before imaging.

Statistical analyses

All cell counts are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance was calculated by unpaired, two-tailed Student t-tests and performed in excel. The resulting P-value is reported.

Results

DSX expression in the CNS is sexually dimorphic across development

To determine the mechanism that underlies the sexual dimorphism in the number of DSX-expressing cells, a polyclonal rat anti-serum specific to a common portion of DSX was generated and DSX-expressing cells during development were analyzed (see Figure 1A). The antibody is specific to DSX, as signal is detected in wild type animals, but not in dsx null animals (Supplemental Figure 1A and B). Using antibodies against DSX and the nuclear, neuron-specific ELAV protein (Robinow and White, 1991), we demonstrate that nearly all DSX-expressing cells detected here are neuronal and that DSX is localized to the nucleus (Supplemental Figure 2). When DSX is over-expressed using a constitutive promoter, signal is detected throughout the brain using the DSX antibody (Supplemental Figure 1C).

Previous studies have shown that DSX is present in the CNS and sexually dimorphic at the adult stage, but not at the 48-hour after puparium formation (APF) stage (Lee et al., 2002). DSX expression 48-hours APF was examined here and a sexual dimorphism in several regions of the CNS was observed. To determine how the dimorphism in DSX-expressing cells is both established and maintained, the number of DSX-expressing cells in the CNS were quantified in 48-hour APF pupae and 0–24 hour adults (see Table 1 and Table 2). At 48-hours APF, the combined number of cells for pC1 and pC2 (see Figure 1 for description of nomenclature) is 88±1.9 and 13±0.8, in males and females, respectively (all cell counts are represented as the mean ± standard error of the mean). A sexual dimorphism in the TN1 cluster of the ventral nerve cord (VNC) was also observed, with 16±1.3 and 0±0 cells, in males and females, respectively (Figure 1).

Table 1.

DSX-expressing cells in the pC1 and pC2 regions of the brain

| Male (XY) | Female (XX) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| cells (n) | cells (n) | ||

| Wild type | Wild type | ||

| 0–24 hour adult | 83+/−3.1 (17) | 0–24 hour adult | 16+/−0.9 (7) |

| 48 hours APF | 88+/−1.9 (7) | 48 hours APF | 13+/−0.8 (12) |

| 0 hours APF | 64+/−2.7 (10) | 0 hours APF | 13+/−0.9 (8) |

| dsx mutants | dsx mutants | ||

| 0–24 hour adult, dsxD/dsxM+R15 | 64+/−1.7 (24) | 0–24 hour adult, dsxD/dsxM+R15 | 56+/−2.4 (15) |

| 0–24 hour adult, dsxM+R15/+ | 56+/−3.8 (9) | 0–24 hour adult, dsxM+R15/+ | 15+/−0.8 (16) |

| 0–24 hour adult, dsxD/+ | 83+/−2.2 (15) | 0–24 hour adult, dsxD/+ | 41+/−1.3 (13) |

| ix mutant | ix mutant | ||

| 0–24 hour adult, ix3/Df(2R)en-B | 75+/−2.9 (12) | 0–24 hour adult, ix3/Df(2R)en-B | 29+/−1.3 (14) |

| fru mutant | |||

| 0–24 hour adult, fru4–40/fruP14 | 93+/−4.8 (8) | ||

| Cells that co-express DSXM and FRUM | |||

| 48 hour APF, UAS-nlsGFP; fru P1-GAL4/+ | 18+/−0.6 (12) |

Table 2.

DSX-expressing cells in the TN1 region of the VNC

| Male (XY) | Female (XX) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| cells (n) | cells (n) | ||

| Wild type | Wild type | ||

| 0–24 hour adult | 15+/−0.5 (12) | 0–24 hour adult | 0+/−0 (12) |

| 48 hours APF | 16+/−1.3 (6) | 48 hours APF | 0+/−0 (8) |

| 0 hours APF | 0+/−0 (12) | 0 hours APF | 0+/−0 (8) |

| dsx mutants | dsx mutants | ||

| 0–24 hour adult, dsxD/dsxM+R15 | 10+/−0.5 (8) | 0–24 hour adult, dsxD/dsxM+R15 | 10+/−0.8 (10) |

| 0–24 hour adult, dsxM+R15/+ | 11+/−0.6 (10) | 0–24 hour adult, dsxM+R15/+ | 0+/−0 (16) |

| 0–24 hour adult, dsxD/+ | 17+/−0.6 (14) | 0–24 hour adult, dsxD/+ | 5+/−0.3 (16) |

| ix mutant | ix mutant | ||

| 0–24 hour adult, ix3/Df(2R)en-B | 18+/−0.7 (12) | 0–24 hour adult, ix3/Df(2R)en-B | 6+/−0.5 (10) |

| fru mutant | |||

| 0–24 hour adult, fru4–40/fruP14 | 15+/−0.6 (5) | ||

| Cells that co-express DSXM and FRUM | |||

| 48 hour APF, UAS-nlsGFP; fru P1-GAL4/+ | 9+/−0.5 (8) |

A similar overall pattern of DSX-expressing cells was observed in the 0–24 hour adult CNS, with a dimorphism in the pC1, pC2 and TN1 regions, as was observed in 48-hour APF pupae [Table 1 and Table 2, Figure 1, and previously described (Lee et al., 2002)]. Two DSX-expressing neurons are present on the anterior dorsal side of the brain (aDN cluster) in both males and females (Supplemental Figure 1D and E); the aDN neurons were previously thought to be male-specific (Lee et al., 2002). Here, the mechanisms by which the sexual dimorphism in DSX-expressing cells in the pC1, pC2 and TN1 clusters are generated were examined.

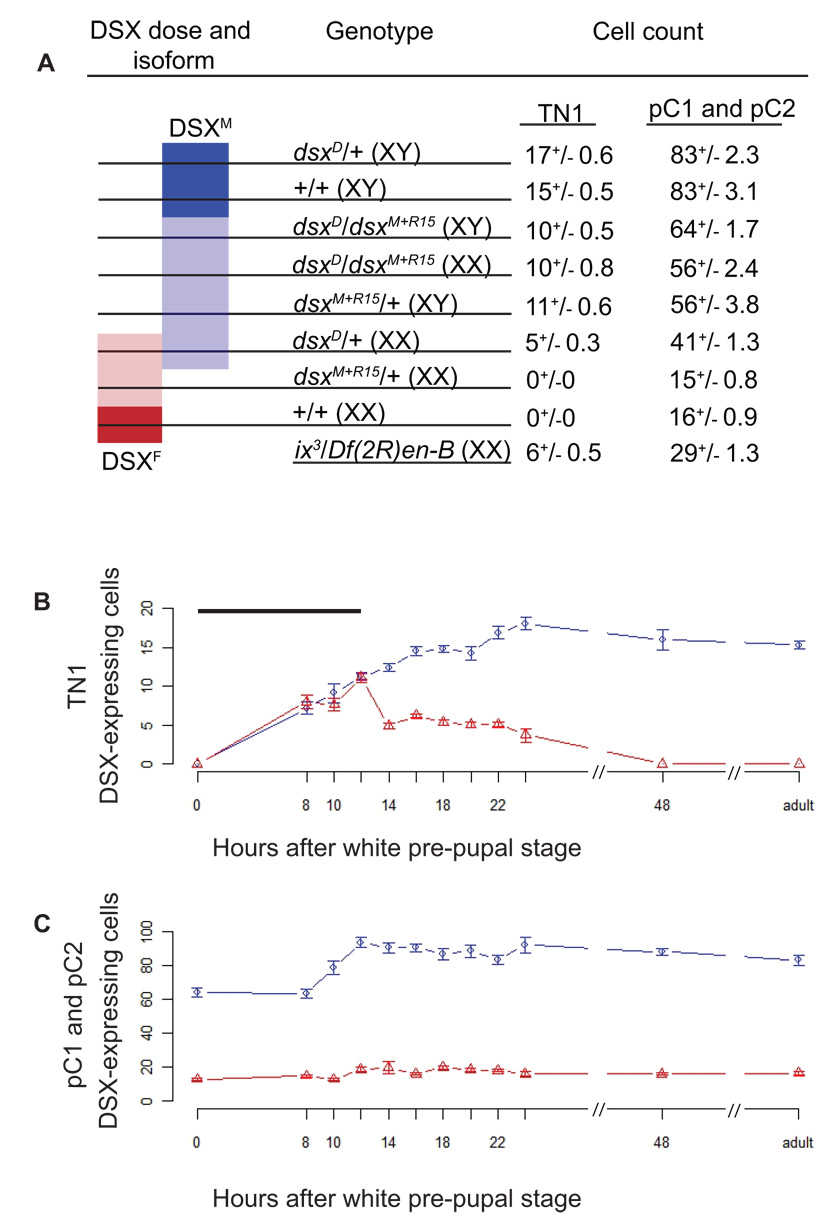

DSX regulates the number of cells in the adult TN1 cluster in an isoform-and dosedependent manner

Given the sexual dimorphism in DSX-expressing cells, we sought to determine whether the difference in DSX isoforms in males and females is responsible for the difference in the number of DSX-expressing cells, or if sex-specific regulation of dsx transcription in males and females is responsible for the difference in DSX-expressing cell number. The TN1 cluster was examined in the adult stage, as the dimorphism in cell number in this cluster is the most dramatic, and therefore the most straightforward to analyze: 15±0.5 and 0±0 cells are in adult males and females, respectively. If the absence of DSX-expressing cells in the TN1 cluster in females is because dsx transcription is not activated, then the number of DSX-expressing cells should be independent of the DSX isoform. Alternatively, if DSX regulates cell number in an isoform-dependent manner, then the presence of a DSX isoform will influence the number of DSX-expressing cells in the TN1 cluster.

Accordingly, the number of DSX-expressing cells in chromosomally XX animals that only produce the DSXM isoform was determined. These animals are transheterozygous for a dsx allele (dsxD), whose product can only be spliced to produce the male-specific isoform, and a dsx null allele (dsxM+R15); hereafter these animals will be called dsxD pseudomales, as they are phenotypically male. The number of DSX-expressing cells in both chromosomally XX and XY dsxD/dsxM+R15 transheterozygous flies was examined; the chromosomally XY flies served as a control to determine the number of DSX-expressing cells when only one copy of dsx can produce DSX product.

In chromosomally XX and XY dsxD / dsxM+R15 flies, 10±0.8 and 10±0.5 cells were observed, in TN1 regions, respectively. Given that both chromosomally XX and XY dsxD/dsxM+R1 flies have the same number of DSX-expressing cells in this region, this demonstrates that the DSX isoform directs the number of cells, rather than differences in dsx transcription in males and females.

Both chromosomally XX and XY dsxD / dsxM+R15 flies had significantly fewer DSX-expressing cells (10±0.5 and 10±0.8 cells) in the TN1 region than wild type males (15±0.5 cells) (P=1.9 × 10−5 and 7.4 × 10−7, respectively), which suggests a dsx dose-dependency for the number of DSX-expressing cells, since the dsxD / dsxM+R15 mutants examined only had one copy of dsx that can make DSXM product. Chromosomally XY flies that are transheterozygous for the dsxD allele and a wild type dsx allele had 17±0.6 cells in the TN1 cluster, which is more than wild type males (15±0.5 cells). Taken together, these results suggest that the dose of dsx is important, and the difference in number in dsxD / dsxM+R15 mutants is not due to the dsxD allele, as if that were the case, fewer DSX-expressing cells would be expected in flies that are transheterozygous for the dsxD allele and a wild type allele, as compared to wild type males.

To further confirm this, DSX-expressing cells were quantified in males that are transheterozygous for one dsx null allele and one wild type dsx allele (dsxM+R15/TM6B; hemizygotes), and thus have one dsx allele that can make DSXM product. These flies had 11±0.6 DSX-expressing cells in the TN1 region, which is similar to the number of DSX-expressing cells we observed in the dsxD/dsxM+R15 pseudomales and males (10±0.5 and 10±0.8 cells, P>0.05 for both comparisons). This observation suggests that there is a threshold amount of DSXM activity required to specify the wild type number of DSX-expressing neurons in the TN1 region. In animals that contain only one dsx allele producing functional product, the amount of DSXM may be close to the threshold needed to establish or maintain the wild type number of neurons.

DSXM and DSXF have antagonistic roles in establishing adult DSX cell number in the TN1 cluster

To determine if DSXM and DSXF have antagonistic roles in establishing the number of TN1-region, DSX-expressing cells, we examined chromosomally XX flies that contain both DSXM and DSXF. These flies are heterozygous for the allele (dsxD) that only produces DSXM and a wild type allele of dsx, which in chromosomally XX flies produces DSXF. Hereafter these transheterozygotes are called dsxD intersexual flies, as they have morphological features of both sexes. Previous studies have shown that DSX functions as a homodimer, and the presence of DSXF interferes with DSXM activity by forming a heterodimer (Erdman et al., 1996). Also, since both DSX isoforms bind the same enhancer element DNA, DSXF homodimers can compete with DSXM homodimers for DNA (Erdman et al., 1996).

When the TN1 cluster in dsxD intersexual flies was examined, 5±0.3 cells were present (Table 2 and Figure 2A); this is intermediate to the number in wild males (15±0.5 cells) and females (0±0 cells), and significantly fewer than the number in dsxD pseudomale animals (10±0.5 cells; P=5.1 × 10−5) or male dsx hemizygotes (11±0.6 cells; P=9.3 × 10−7); these latter two genotypes have one copy of dsx that produces DSXM. These results suggest that DSXM and DSXF isoforms have antagonistic roles with respect to establishing the TN1 population of DSX-expressing cells. DSXF may reduce the number of cells in dsx intersexual animals indirectly, by interfering with DSXM activity and effectively reducing the dose of DSXM. Alternatively, DSXF may directly regulate the TN1 region cell number, perhaps by inducing cell death or blocking cell division. Clearly, DSXM and DSXF establish the number of DSX-expressing cells in a context-dependent way, as DSX-expressing cells in females persist in other regions of the CNS at this same developmental time (Figure 1).

Figure 2. The number of DSX-expressing cells depends on the dose and isoform of DSX present.

(A) Dark blue and light blue bar indicates genotypes with two or one copy of dsx that can produce DSXM, respectively. Light red and dark red bar indicates genotypes with one and two copies of dsx that can produce DSXF, respectively. Chromosomal sex of the animal is shown in parentheses. (B and C) The number of DSX-expressing cells in male and female CNS from 0 hour white pre-pupae to 0–24 hour adults, in the TN1 cluster (B) and posterior brain clusters (C) in males and females. The bar in (B) represents the period during development when the TN1-region, DSX-expressing cell number is isoform-independent. Six to thirty individuals were analyzed at each time point (B and C). The abscissa and ordinate show the developmental stage and number of DSX-expressing cells, respectively. Male (blue circles) and female (red triangles) data are indicated. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean.

Male and female TN1 regions have detectable DSX-expressing cells early in pupal development, but DSX-expressing cells in the female TN1 region are not detectable in later stages

To determine how the number of DSX-expressing cells is established by the DSX isoform present, the TN1 cluster was examined during development. In females, the absence of DSXM or the presence of DSXF may result in death of those cells. Alternatively, DSXM may drive additional cell divisions. The number of DSX-expressing cells was examined during metamorphosis, with the rationale that the developmental profile would provide insight into the mechanism underlying the resultant sex-specific cell number (see Figure 2B, Supplemental Table 1).

In the TN1 cluster, in 0-hour white pre-pupae, no DSX-expressing cells were present in males or females (Figure 2B, Table 2). Twelve hours later (12-hours APF), 11±0.4 and 11±0.6 cells in males and females are observed, respectively. In females, at 14-hours APF, the cell numbers decrease to 5±0.4. By 48-hours APF, no DSX-expressing cells are observed in the TN1 region in females. In males, the number of cells steadily rises with time, with 12±0.5 and 16±1.3 cells observed at 14- and 48-hours APF.

Females initially have a substantial number of cells, located in a homologous position to those observed in males, and none of these cells are detected by 48-hours APF. This suggests that sex-specific cell death may be the mechanism by which the sexually dimorphic number of cells is established. After 12-hours APF, males have more DSX-expressing cells than were observed in females, which suggests that the loss of DSX-expressing cells in females is not sufficient to explain the entire difference in cell numbers. An additional cell division of the DSX-expressing cells may be occurring in males, and DSXM may either permit or direct this cell division.

Sex-specific cell death leads to absence of DSX-expressing neurons in the TN1 cluster in females

To address if cell death is responsible for the absence of detectable TN1-region, DSX-expressing cells in females, the number of DSX-expressing cells showing molecular signs of cell death was determined. In one of the stages of cell death, cellular endonucleases cleave nuclear DNA into small fragments that are detectable by the TUNEL (Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling) assay. Female and male TN1 regions were examined starting at 8 hours APF, every two hours, until 22 hours APF (Figure 3). These time points were chosen because the number of DSX-expressing cells declines substantially in females during the 12–24-hour APF period (Figure 2B). Animals were staged by starting with the white pre-pupae stage, which lasts about 20–30 minutes, so each subsequent time point examined represents about 40 minutes to one hour of development.

Figure 3. DSX-expressing cells in the TN1 cluster in females undergo cell death during the first day of pupal development.

For panels A–D, DSX-expressing cells (red), TUNEL staining (green), and co-localization (yellow) in the TN1 regions at 14-hours APF is shown. A–C show female tissues; D shows male tissue. (A and B) TUNEL-positive cells are also DSX-expressing cells. Arrowheads indicate a TUNEL-positive cell with faint DSX signal. (C) TUNEL-positive cells in close proximity to remaining DSX-expressing cells. DSX-expressing cells in the TN1 region in 0–24 hour adult wild type females (E), XX ix3/Df(2R)en-B flies (F), and wild type males. 40X confocal sections of ~0.5 µm are shown for A–G. (G) The number of DSX-expressing cells in the CNS of dsx and ix mutants from 0 hour white pre-pupae to two-day old pupae, in the TN1 cluster (H) and posterior brain clusters (I). Legend indicates genotypes examined. Six to twenty individuals were analyzed at each time point. The abscissa and ordinate show the developmental stage and number of DSX-expressing cells, respectively. Chromosomal sex of animals is indicated in all panels and legend. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean.

Overlap in TUNEL staining and DSX was observed at all time points examined between 10- and 22-hours APF, in female, but never in male, TN1-region VNC tissue. During the 12 hour and 14 hour APF stages, in which the largest decline in TN1-region, DSX-expressing cell number is observed (Figure 2B), 28% of female samples examined had at least one TUNEL-positive, DSX-expressing cell (n=36), whereas males had none (n=16). Typically, only one cell with overlap in TUNEL staining and DSX was observed per female VNC. However, given the difficulty of detecting a nuclear transcription factor that is being stripped from the nucleus during cell death (Robinow et al., 1993), the changes in nuclear morphology as a cell dies, and the limited window in which it is possible to detect TUNEL staining in a dying cell, this result is not unexpected. Furthermore, the overall number and distribution of TUNEL-positive cells in male and female VNC tissue is very similar at all stages examined, which suggests that the overlap observed with DSX and TUNEL in the female VNC is specific, and not due to a greater number of dying cells in females, which would then make it more likely that DSX-expressing cells would randomly overlap with TUNEL staining in females. We thus conclude that female-specific cell death in the TN1 region establishes the sexual dimorphism in cell number.

To further determine the mechanism that establishes female-specific, TN1-region cell death, female adult transgenic animals that over-express cell death inhibitors (including bacculovirus p35 and the caspase inhibitor DIAP) and adult animals that are mutant for cell death effectors (transheterozygotes for a deletion of rpr, hid, and grim and a deletion of rpr) were examined. None of the female animals examined had TN1 region, DSX-expressing cells, leaving the cell death effectors in the TN1 region an open question (Supplemental Table 2).

DSXF function is necessary, but not sufficient, for female-specific apoptosis that results in the absence of cells in the adult TN1 region

To determine if DSXF is required for female-specific cell death in the TN1 region, dsx function was abrogated in females via mutation of an obligate DSXF heterodimer partner encoded by intersex (ix); this allows for the detection of DSX-expressing cells with the α-DSX antibody in cells in which DSX is not functional. ix encodes an obligate heterodimer partner of DSXF, but not DSXM, and is required for the establishment of all female-specific morphological features under the control of DSXF that have been examined (Garrett-Engele et al., 2002). Therefore, if DSXF is required for the absence of DSX-expressing cells in the female TN1 region, than in ix mutant females, DSX-expressing cells should be observed, as DSXF is not functional in the absence of IX. Accordingly, a strong ix hypomorphic allele combination (ix3/Df(2R)en-B) was examined. DSX-positive cells (6±0.5 cells) were observed in the TN1 region of ix adult females (n=10, Figure 3F), which is significantly more than the zero observed in wild type adult females (P = 4×10−7). Therefore, DSXF is necessary for the absence of TN1-region, DSX-expression cells. Because the ix allele combination is not a null (Garrett-Engele et al., 2002), some DSXF function may remain to direct cell death in the DSX-expressing, TN1-region neurons, and that could explain why the number of TN1 region cells are less than the number observed in wild type males. Alternatively, DSXM may be required for establishing the final cell number in males.

Given the observation that DSXF activity is required for the absence of cells in the TN1 region in females, we next tested if it is sufficient to induce cell death. DSXF was over-expressed with the fru P1-GAL4 driver, and the number of FRUM-expressing cells was assayed using an antibody directed against FRUM. We and others (see below and Rideout et al., 2007) have shown that there are a small number of DSX-expressing, TN1-region cells that overlaps with fru P1 in males. The activity of dsx is context dependent, based on the observation that in some cells in females, dsx is required for cell death, whereas in other populations, DSX-expressing cells persist. Thus, it was important to test if DSX is sufficient to drive cell death in a cell population most similar to the DSX-expressing, TN1 region female cells. Accordingly, the anterior surface fru P1-expressing PrMs region cells were assayed; the fru P1 anatomical nomenclature is used, as fru P1-expressing cells were examined (anterior surface FRUM-PrMs cells overlap DSX-TN1 cells in males; Lee et al., 2000). There is no statistical difference in number of anterior region PrMs cells between control males (fru P1-GAL4/+; 72±2.3 cells) and males that expresses DSXF under the fru P1-GAL4 promoter (fru P1-GAL4; UAS-DSXF flies; 72±2.6 cells) (P = 0.4). Therefore, over-expression of DSXF in the male PrMs cells is not sufficient to induce cell death, suggesting that DSXF acts in a specific context in females to direct cell death. Alternatively, the PrMs cells may not homologous to the TN1 region cells in females, or the over-expression may not produce enough DSXF to induce cell death.

Increase in cell number in TN1 region between 0 hr wpp to 12 hr pupal stages is DSX isoform independent, but dsx dependent

To determine when in development dsx is required to establish the TN1-region, DSX-expressing cell number, DSX–expressing cells were examined in dsx mutant backgrounds. Between the 0 hour wpp (0 cells in both sexes) and 12 hour pupal stages (~11 cells in both sexes), the increase in DSX-expressing cell number in males and females is indistinguishable and shows a similar trajectory (see bar in Figure 2B). The following genotypes were examined: male and female animals heterozygous for a null and a wild type allele of dsx and chromosomally XX, ix (ix3/Df(2R)en-B) flies. In these genotypes, dsx function is reduced, which allows us to determine if the increase in cell number between 0 and 12 hour APF, in males and females, requires wild type levels of dsx product and function.

At 8 hours APF, wild type males and females have 7±0.8 and 8±0.9 TN1-region cells respectively, whereas no DSX-expressing cells were detectable in male and female dsx hemizygotes (dsxM+R15/TM6B), and significantly fewer cells were observed in ix females (2±0.7 cells), as compared to wild type females (8±0.9 cells) (P = 7×10−6; Figure 3H, Supplemental Table 1). This suggests that dsx is required for establishing the number of cells in both males and females during the 0 hour to 8 hour APF stages.

By 12 hours APF, the last time point examined before wild type males and females diverge in TN1-region cell number, there is no statistical difference between chromosomally XY animals dsxM+R15/TM6B and wild type male animals (P = 0.12), although there is a slight, but statistically significant decrease in chromosomally XX, dsxM+R15/TM6B animals (8±0.7 cells), as compared to wild type females (11±0.6 cells) (P = 0.002) (Figure 3H). Chromosomally XX, ix mutants (ix3/Df(2R)e-B) were also examined at 12 hours APF, and a slight but significant decrease in cell number was observed as compared to wild type females (9±0.9 and 11±0.6 cells, respectively; P = 0.05; Figure 3H). Taken together, these results suggest that the wild type amount of dsx activity is required to establish DSX-expressing TN1-region cell number, between 0 and 12 hour pupal stages.

To determine if the increase in the number of cells during the 0 hour wpp to 12-hour APF stage is DSX-isoform independent, the number of DSX-expressing, TN1-region cells were examined in chromosomally XX, dsxD intersexual flies that produce both DSXM and DSXF. If the isoforms have distinct activities, the presence of both isoforms would interfere with wild type activity. The number of DSX-expressing cells in dsxD intersexual flies at 8- and 12-hour APF stages in chromosomally XX animals was indistinguishable from that observed in wild type males and females (Figure 3H). At 8 hours APF, dsxD intersexual flies have 6±0.5 cells; wild type males and females have 7±0.8 and 8±0.9 (for both, P>0.05). At 12 hours APF, dsxD intersexual flies have 11±0.6, wild type males have 11±0.4 (P >0.05), and wild type females have 11±0.6 cells (P >0.05) (Figure 3H). This suggests that the establishment of cell number during this period of development is DSX-isoform independent, and that the DSX transcription factors do not have antagonistic functions with respect to establishing cell number. Our previous studies have shown that DSXM and DSXF can activate and repress many of the same target genes, but that the extent of activation or repression is isoform specific (Goldman and Arbeitman, 2007). These results are consistent with that observation and suggest that in the context of the TN1-region, DSX-expressing cells during early pupal stages, the amount of DSX activity in both males and females is sufficient to establish the final cell number.

Sex-specific differences in DSX-expressing, TN1 region cells after 12 hour APF stage is DSX-isoform dependent

In wild type animals, after the 12-hour APF stage, the number of DSX-expressing, TN1-region cells is sexually dimorphic. The absence of TN1-region, DSX-expressing cells in females is due to female-specific cell death that initiates after the 12 hour APF stage and requires DSX activity, as when ix mutant females were examined, 6±0.5 cells were evident at the adult stage. At the 16-hour APF stage, ix females had roughly the same number of TN1 region, DSX-expressing cells as they had at 12 hours, demonstrating that the trajectory of cell loss is very different in ix females than that observed in wild type females, where the number of TN1-region DSX-expressing cells has dropped about two-fold (Figure 3H). This demonstrates that DSXF is required for directing the cell death process during early pupal development and not just at late stages. When female dsx hemizygotes (dsxM+R15/TM6B) were examined, the cell death trajectory looked very similar to that observed in wild type females, suggesting that ~2-fold dose reduction does not affect cell number at this stage.

After the 12-hour APF stage, TN1-region cell number in males continues to increase, demonstrating that cell death in females is not sufficient to account for the sexual dimorphism in cell number observed in adults. The number of DSX-expressing, TN1-region cells in male dsx hemizygotes (dsxM+R15/TM6B) at the 16-hour APF stage was examined, and a slight (13±0.5 cells), but significant (P = 0.03), decrease in cell number compared to wild type males (15±0.6 cells ) was observed (Figure 3H). However, at adulthood, dsx heterozygotes only have 11±0.6 cells, compared to 15±0.5 cells in wild type males (P = 2.5 × 10−6), suggesting that the dose of dsx is critical for the increase of cells observed after the 16 hour-APF stage. This is also consistent with the observations of chromosomally XX, dsxD intersexual animals, in which the TN1-region cell number is similar to wild type males at the 16-hour APF stage (15±2 and 14.5+0.6 cells in wild type males), but subsequently there is a decline to 5±0.3 cells, as compared to 15±0.5 cells in adult wild type males (Figure 3H). Taken together, this suggests that both the dose and isoforms of DSX are critical for the increase in cell number observed in wild type males after the 12-hour APF stage.

The difference in DSX cell number in the adult posterior brain clusters is dependent on the amount of DSX activity and the DSX-isoform present

To determine if the DSX isoform and the dose of dsx present also determines sex-specific, DSX-expressing cell numbers in other regions of the CNS, the combined number of neurons in the posterior brain pC1 and pC2 clusters in dsxD pseudomales was examined. In adult chromosomally XX and XY, dsxD / dsxM+R15 pseudomales and males (only produce DSXM), that only have one allele of dsx that produces DSXM, 56±2.4 cells and 64±1.7 cells, respectively, were observed; this is significantly lower than the wild type male numbers of DSX-expressing cells (83±3.1 cells; P =6.1 × 10−8 and 3.7 × 10−6, respectively). However, the number of DSX-expressing cells in XX and XY dsxD / dsxM+R15 animals are much closer to each other, and to the number of cells observed in wild type males, (83±3.1 cells, Table 1), than wild type females (16±0.9 cells, Table 1), consistent with the idea that the DSX isoform establishes the number of DSX-expressing cells and that the difference in number is not due to sex-specific differences in expression of dsx.

To determine if the fewer cells in the adult dsxD / dsxM+R15 animals, as compared to adult wild type males, is because there is only one allele that can produce DSXM product, males transheterozygous for a wild type dsx allele and a dsx null allele, dsxM+R15, were examined. These males had 56±3.8 cells in the pC1 and pC2, which is also significantly fewer than what is observed in wild type males (P =1.8 × 10−5), consistent with the idea that the dose of dsx establishes cell number.

We also determined if the difference in number between dsxD pseudomales (XX; 56±2.4 cells) and dsxD / dsxM+R15 (XY; 64±1.7 cells) males, as compared to wild type males (83±3.1 cells), is due to the reduced dose of dsx, and not the presence of the dsxD allele, by examining animals that contain both the dsxD allele and a wild type allele. In these animals that have two copies of dsx that can make DSXM product, the number of cells in the pC1 and pC2 clusters is 83±2.3 (Table 1), which is indistinguishable from wild type males (P>0.05). This demonstrates that the dsxD allele is not responsible for differences in cell numbers observed in dsxD/dsxM+R15 animals, as we would have expect fewer cells in the dsxD/dsxM+R15 animals, but rather, the dose of dsx present is the crucial factor.

To investigate if DSXF and DSXM also have antagonistic functions in establishing the number of cells in the posterior brain clusters, adult dsxD intersexual flies that produce both DSXF and DSXM were examined. An intermediate number of DSX-expressing cells was observed (41±1.3 cells), as compared to wild type males (83±3.1) and females (16±0.9 cells), but much fewer than that observed in dsxD pseudomales (64±1.7 cells; Table 1), suggesting that the DSX isoforms have antagonistic functions in establishing pC1 and pC2, DSX-expressing cell number. Taken together, the results from both the TN1 region and the posterior brain cluster analyses are consistent with both the DSX isoform and the dose of dsx establishing the adult number of DSX-expressing cells (Figure 2A).

DSX-expressing posterior brain cells undergo more cells divisions during metamorphosis in males as compared to females

The pC1 and pC2, DSX-expressing clusters were examined during development (Figure 2C). At the 0-hour white pre-pupal stage, males already display significantly more DSX-expressing cells than females (64±2.7 and 13±0.8 cells, respectively; P =1.3 × 10−9). DSX-expressing cell numbers in females remain fairly constant throughout the 8-to 48-hour APF pupal stages, while the DSX-expressing cell numbers in males increase rapidly between the 8-and 12-hour APF time points (from 68.4 ±2.7 to 93.6±3.2 cells). Thus, in the pC1 and pC2 clusters, DSXM may act to promote cell division. Alternatively, the presence of DSXF may block additional cell division during metamorphosis, and DSXM activity may simply be permissive for cell division that is driven by other pathways.

To address if the sex-specific difference in DSX-expressing pC1 and pC2 cell number is due to more cell division in males during metamorphosis, as opposed to more cells expressing dsx in males, molecular hallmarks of cell division were examined in these cells. We reasoned that if the increase in cell number in males is due to cell division, then we should be able to detect molecular markers of cell division in males, and not in females. Here the incorporation of BrdU, a thymidine analog that is incorporated into dividing cells in S phase and can be detected using immunocytochemistry, was examined during the period in metamorphosis in which cell number increases substantially in males and not in females (see bar in Figure 4A).

Figure 4. DSX-expressing cells co-localize with BrdU in males, but not in females.

(A) Adaptation from Figure 2C shows a schematic of the four-hour BrdU pulse from 8-hours APF to 12-hours APF. For all panels, anti-DSX is shown in green, anti-BrdU is shown in red, and co-localization is yellow. (B and C) Cells in female posterior brain regions do not show co-localization with BrdU and DSX, while cells in male posterior brains (D and E) show co-localization.

Male and female CNS tissues were dissected at the eight-hour stage, incubated with BrdU for four hours, fixed and stained for BrdU and DSX. Although in other parts of the CNS the pattern of BrdU incorporation in male and female brain is largely indistinguishable during this time period, cells that co-label with the DSX and BrdU antibody were detected only in males (17/20 samples examined showed co-labeling), but never in females (0/26 samples examined showed co-labeling) (Figure 4), consistent with the idea that the increase of cell number in males is due to increased cell division. The maximum number of cells that co-label with the antibody to BrdU and DSX in a given male brain was eight cells per hemisphere, and none were ever detected in females. Although this does not fully account for the approximately twenty cell increase per hemisphere in males during this time (see Figure 2C), it demonstrates that DSX-expressing cells in males are undergoing cell division in the region and during the time period expected. One possibility is that some of the DSX-expressing pC1 and pC2 cells are arrested in the G2 phase of the cell cycle and thus would be in the cell division cycle, but would be beyond the stage when BrdU incorporation occurs.

Consistent with DSXM driving additional cell divisions, when the TN1 region was examined, there was a slight, but statistically significant increase in FRUM-expressing cells when DSXM was over-expressed in the fru P1 circuitry, which suggests that DSXM can direct additional cell divisions in this region (fru P1-GAL4; UAS-DSXM flies had 80±2.4 FRUM-expressing cells, while fru P1-GAL4/+ controls had 72±2.6; P = 0.02). These two lines of evidence suggest that DSXM may cause additional cell divisions in both TN1 and posterior brain regions of the CNS, where DSX expression is sexually dimorphic.

Sex-specific differences in DSX-expressing, posterior region brain cells that are established during metamorphosis depend on the DSX isoform and dose of dsx

To examine how the sex-specific differences in DSX-expressing posterior brain cell numbers are established during metamorphosis by dsx, the following genotypes in which dsx function is reduced were examined: male and female animals heterozygous for a null and a wild type allele of dsx and chromosomally XX, ix (ix3/Df(2R)en-B) flies. At the 8-hour APF time point male dsx hemizygotes (dsxM+R15/TM6B) had the same number of posterior brain region DSX-expressing cells, as wild type males (Figure 3I). However, at the 12-hour APF time point, which is after the rapid increase in pC1 and pC2 cells in males, dsx male hemizygotes display a significant decrease in cell number (P = 8 × 10−5), as compared to wild type males, suggesting that the dose of dsx is important for the increase in cell number in males. The difference in cell number between male dsx hemizygotes and wild type males is maintained at the 16-hour APF time point, and by the adult stage the difference is more substantial (dsx male hemizygotes have only 56±3.8 cells, whereas wild type males have 83±3.1 cells cell numbers (Figure 3I), suggesting that the wild type dose of dsx is required not only to drive the early divisions, but to also maintain the population of DSX-expressing cells after the 16-hour APF stage.

At the 12-hour APF time point, dsx female hemizygotes also display a significant decrease in cell number, as compared to wild type females (dsx female hemizygotes have 14±1.2 cells, whereas wild type females have 19±1.3 cells; P = 0.004; Figure 3I). This difference in cell number between dsx female hemizygotes and wild type females is maintained at the 16-hour and adult stage (at 16-hours APF, dsx females have 13±0.7 cells, whereas wild type females have 16±0.6 cells; P = 0.003; Figure 3I), suggesting that the initial establishment of DSX-expressing cell number in pupae is sensitive to the dose of dsx in females. However, when female ix mutants were examined, more female posterior-region DSX-expressing cells were observed, as compared to wild type females, at all four stages examined (Figure 3I), suggesting that at a certain point in development, DSXF may prevent cell division in this region. Consistent with this idea is the observation that during the pupal stages examined, chromosomally XX, dsx intersexual animals have significantly fewer cells than dsx hemizygous males and wild type males, suggesting that DSXF and DSXM have antagonistic activities with respect to establishing cell number.

DSXM and FRUM are co-expressed in a subset of neurons in adults and pupae, but DSXM expression profile does not depend on FRUM

Given the sexual dimorphism in DSX-expressing cells, we wanted to determine if FRUM plays a role in males in establishing the number of DSX-expressing cells. A recent report has shown that DSXM and FRUM co-localize in a subset of neurons in the mid-pupal CNS (Rideout et al., 2007). Given the observations that demonstrate that DSX-expressing cell number is established during metamorphosis, we wanted to determine if FRUM plays a functional role in specifying that developmental fate by analyzing the developmental profile of DSXM and FRUM co-localization. To detect FRUM-expressing cells, a GAL4 driver that is expressed in the same cells as the fru P1 transcript was used (hereafter called fru P1- GAL4; Stockinger et al., 2005) to drive the expression of nuclear localized GFP (UAS-nlsGFP) in males.

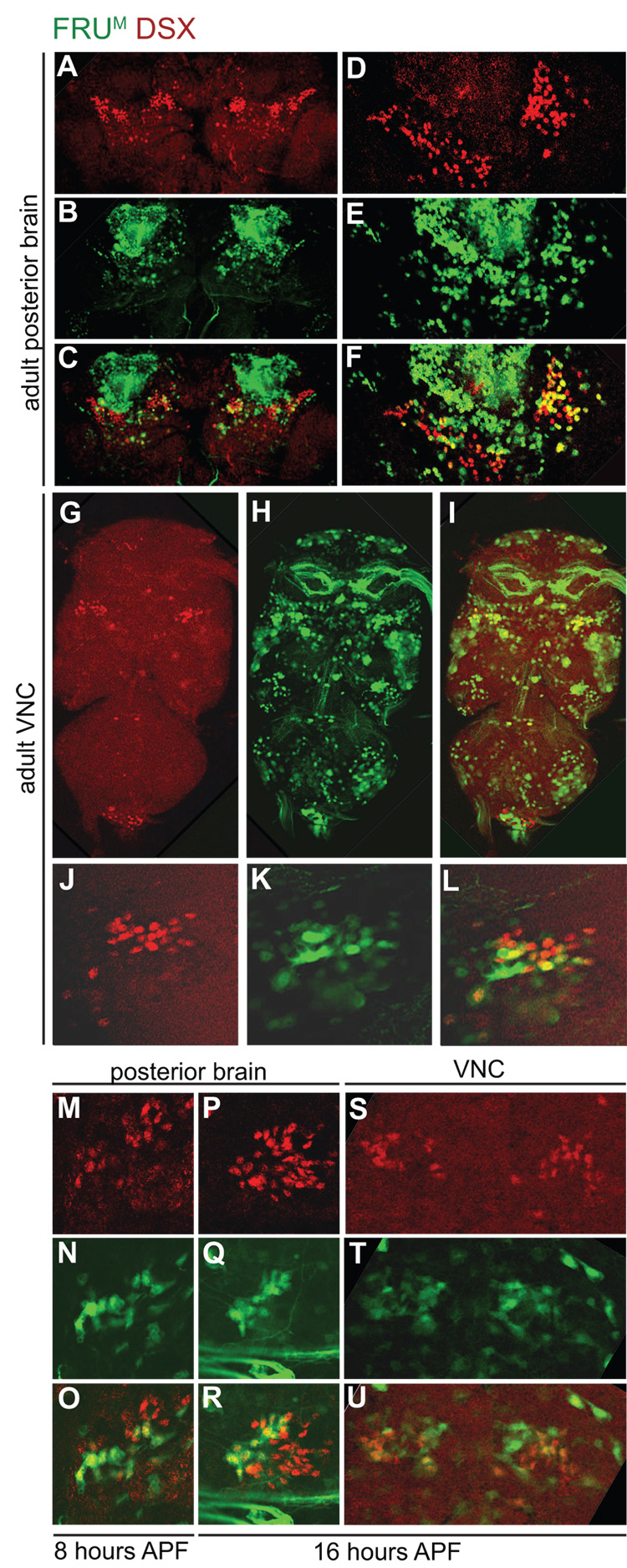

In 0–24 hour old adult males overlap was observed between the DSX-expressing cells and the fru P1-expressing cells in the pC1, pC2 and TN1 clusters (Figure 5 and Table 1 and Table 2), which is similar to previous reports of overlap at mid-pupae stages (Rideout et al., 2007). Extensive co-expression of DSX and FRUM was detected in the abdominal ganglion region of the VNC (Billeter et al., 2006). Cells were identified that co-express fru P1 and DSXM in the subesophogeal region of the brain, the SN and SLN clusters, and several cells located in the TN2 region of the VNC (Supplemental Figure 3). Given that only a subset of DSX-expressing cells overlap in expression with fru P1-expressing cells (Figure 5, Table 1; (Rideout et al., 2007)), DSX-expressing cells are likely functionally distinct, despite residing in close proximity.

Figure 5. fru P1-expressing cells and DSX co-localize in the CNS.

DSX-expressing (red) and fru P1-expressing (green) cells in adult (A–L), 8 hour APF (M–O), and 16 hour APF (P–U) male CNS. fru P1 -expressing cells are visualized using a fru P1-GAL4 transgene, driving expression of nuclear GFP. (A) DSX (red) and (B) fru P1-expressing cells (green) co-localize (C) (yellow) in the posterior midbrain. Higher magnification (40X) of DSX (D) and fru P1-expressing cells (E) in the pC1 and pC2 clusters of the midbrain; (F) is merged image. (G) DSX and (H) fru P1-expressing cells co-localize (I), see arrowheads, in the VNC. Higher magnification (40X) of (J) DSX and (K) fru P1-expressing cell co-localization (L) in the TN1 region of the VNC. (M) DSX and (N) fru P1-expressing cells co-localize (O) in male a brain 8 hours APF. (P) DSX and (Q) fru P1-expressing cells co-localize (R) in a male brain 16 hours APF. (S) DSX and (T) fru P1-expressing cells co-localize in the TN1 clusters of a male VNC 16 hours APF. Both TN1 clusters are shown. Unless otherwise indicated, 20X confocal sections (~1 µm thick) are shown.

Expression patterns of fru P1 and DSX at 8-, 12-, 16-, and 48-hours APF were next examined in males in the pC1, pC2 and TN1 and TN2 regions. At 8-hours APF, co-expression was observed in brain regions that appear to be the cells fated to become the pC1 and pC2 clusters, as well as the TN2 region of the VNC, but not the TN1 region (Figure 5). However, by 12-hours APF, cells in the TN1 region of the VNC, and the pC1 and pC2 regions of the brain co-express DSX and fru P1. Males from 12-, 16-, 48- hour APF and adults had similar patterns. Overlap of DSX and fru P1-expressing cells in the TN1 and TN2 regions in the VNC, and the pC1 and pC2 regions in the brain were observed (Figure 5; Supplemental figure 3; (Rideout et al., 2007)). Given that the number of DSX-expressing cells in males is established during pupal stages and co-localization of FRUM and DSXM are observed during these stages, we next determined if FRUM plays a role in establishing DSXM cell numbers.

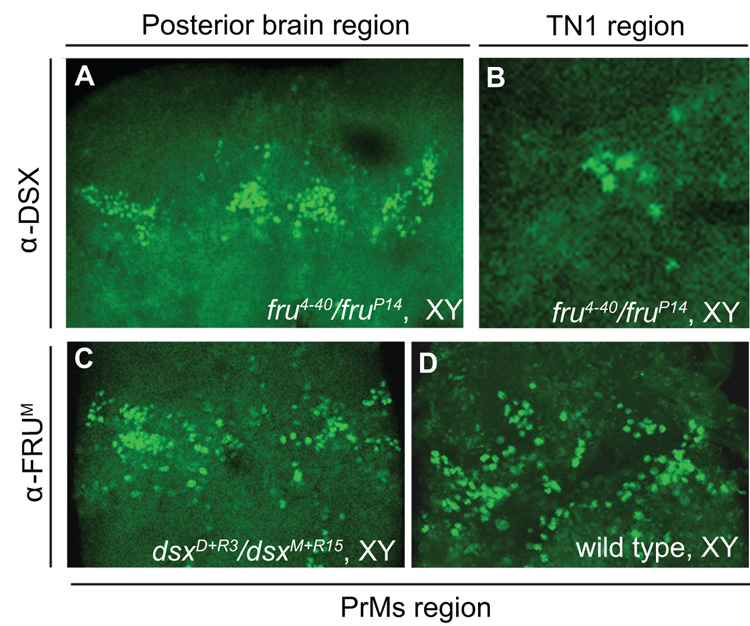

DSX expression was examined in 0–24 hour adult fru P1 mutant males that do not produce FRUM. We characterized the three clusters that show sexually dimorphic numbers of DSX-expressing cells (pC1, pC2 and TN1) and observe no statistically significant differences between wild type males and fru P1 mutant males (Table 1 and Table 2, Figure 6A and B), demonstrating that FRUM does not establish the sexual dimorphism in the number of DSX-expressing cells in these regions in 0–24 hour adults.

Figure 6. DSX expression in fru P1 null animals and FRUM expression in dsx null animals.

DSX-expressing cells in the posterior brain (A) and TN1 cluster (B) of fru P1 null mutant males. FRUM-expressing cells in the PrMs region of the VNC in dsx null males (C) and wild type control males (D). 20X confocal sections (~1 µm thick) are shown.

DSX and fru P1 do not extensively co-localize in pC1, pC2 and TN1 region neurons in females

A recent observation has shown that the fru P1-expressing cell circuit is important for female behaviors (Kvitsiani and Dickson, 2006). In addition, it has been shown that DSX is required to establish the male-specific number of fru P1-expressing cells (Rideout et al., 2007). Given the observation of female-specific cell death in the DSX-expressing, TN1 cluster cells, we wanted to determine if DSX plays a role in establishing the number of fru P1-expressing cells in females. If DSXF is responsible for a difference between males and females in fru P1-expressing cell number previously reported (Rideout et al., 2007), we would expect to see about ten cells per hemisegment with overlap between DSXF and fru P1 in the TN1 region, as that is the difference in fru P1-expressing cell number reported to be established by DSX (Rideout et al., 2007).

Accordingly, the fru P1-GAL4 driver that produces GAL4 in homologously positioned cells in both males and females was used to assess the overlap between fru P1-expressing cells and DSX in females. Females at 8-, 12-, and 16-hour APF were examined, when DSX-expressing TN1 cells are present in females, as well as 48-hour APF and 0–24 hour adults. No cells were consistently observed expressing both fru P1-GAL4 and DSX in the TN1, pC1 or pC2 regions in females at the 8-, 12-, 16-, -48-hour APF stages and 0–24 hour adults. Taken together, the absence of overlap between fru P1-expressing cells and DSXF during development suggests that DSXF does not direct the number of fru P1-expressing cells in females in the TN1 region or posterior brain in a cell autonomous manner.

DSXM does not direct the number of FRUM -expressing cells in adults

To determine if DSXM is required to maintain fru P1-expressing cells in the TN1 region in males, FRUM expression was examined in dsx mutant males in the PrMs region of the VNC (nomenclature from Lee, et al., 2000). The FRUM-PrMs cluster overlaps the DSXM-TN1 region. Using a FRUM polyclonal antibody, no significant difference was found between FRUM-expressing cell number in dsx null male XY (57±1.7 cells) and wild type males (56±1.7 cells), in 0–24-hour adults (Figure 6C and D), on the anterior surface of the PrMs region of the VNC where DSX and FRUM co-localize (n=16 and n=18, respectively). Furthermore, the total number of FRUM-expressing cells in the entire PrMs region showed no statistically significant difference in FRUM-expressing cells, between dsx null males (98±5.5 cells) and wild type males (105±3.1 cells). The number of FRUM-expressing cells detected was comparable to previous reports (Lee et al., 2000). This suggests that at the 0–24 hour stage, the number of FRUM-expressing cells is not regulated by DSXM. DSXM may be required later in adult life to maintain parts of the fru P1-circuitry. Evidence for this hypothesis comes from the recent report that shows 5–7 day old dsx null males have roughly 20 fewer FRUM-expressing cells in the PrMs region of the VNC than wild type males (Rideout et al., 2007). However, when 5–7 day old adult flies were examined in this study, dsx null flies had on average 78±2.6 cells on the anterior surface of the entire PrMS region, and wild type flies had 73±1.3 cells; these values do not differ significantly (P = 0.9). The discrepancy between the two studies could perhaps be explained by differences in strain or reagents employed. Nonetheless, the data presented here suggest that FRUM-expressing cell number in males can be established by a mechanism that is independent of DSX.

Discussion

The identity of dsx has been known for many years (Burtis and Baker, 1989), but how DSX specifies sexually dimorphic neural circuits has only begun to be investigated. Here, we report a sexual dimorphism in the number of DSX-expressing cells in the TN1 cluster in the VNC and in the pC1 and pC2 clusters in the posterior brain, during both pupal and adult stages, that is established by the DSX isoform and dose of dsx present. Males have consistently higher numbers of DSX-expressing cells in the pC1, pC2 and TN1 clusters than females, and for the pC1 and pC2 regions, we show that DSX-expressing cells undergo more divisions in males than in females. Our results from examining the brain clusters pC1 and pC2 and VNC TN1 clusters are consistent with previous analyses that demonstrated that DSXM promotes additional neuroblast divisions in male abdominal ganglion neuroblasts (Taylor and Truman, 1992). We propose that DSXM may promote additional neuroblast divisions in these clusters, given that the DSX-expressing pC1 and pC2 cells are in very close proximity, and thus might be derived from the same progenitor (Pereanu and Hartenstein, 2006).

We also demonstrate that in males, fru P1 is not required to establish the number of DSX-expressing cells in adults. Rather, our results are consistent with the sex-specific DSX isoform establishing the dimorphism in number of DSX-expressing cells in these clusters. Furthermore, in adult males, DSXM does not appear to be required to establish the number of fru P1-expressing cells, as was suggested in a previous study (Rideout et al., 2007).

The regions of the CNS where DSX is detected in a sexually dimorphic pattern have been implicated in underlying the potential for male courtship behaviors. Early gynandromorph studies, in which animals were mosaic for male and female tissues, showed that certain regions of the CNS needed to be genetically male or female for normal male courtship behavior to occur (Hall, 1977). Those studies showed that the posterior midbrain, where the pC1 and pC2 clusters reside, were important for reproductive behaviors in both sexes (Hall, 1977 )(Tompkins and Hall, 1983). Interestingly, the posterior brain region contains DSX-expressing cells in both male and females, suggesting dsx function may underlie these early observations. Additionally, the mesothoracic ganglion of the ventral nerve cord, where the TN1-region, DSX-cluster is located, was shown to underlie male wing song (von Schilcher, 1979).

It was recently shown that DSXM and FRUM collaborate to establish the neural circuitry that underlies wing song formation (Rideout et al., 2007), and DSXM is expressed in neurons that comprise the fru neural circuit, which is necessary and sufficient for the early steps of the male courtship ritual (Ryner et al., 1996; Demir and Dickson, 2005; Manoli et al., 2005)). Here, we observe extensive overlap of fru P1-expressing cells and DSX expression in males in both the posterior brain and ventral nerve cord [Figure 2; Rideout et al., 2007)], as well as overlap in the abdominal ganglion, as previously reported (Billeter et al., 2006). This overlap begins in certain CNS regions as early as 8 hours APF and is maintained to the 0–24 hour adult stage. Thus, the anatomical position of these sexually dimorphic neurons in both in the posterior midbrain and the mesothoracic ganglion, as well as their presence in the fru neural circuit, suggests that they may participate in establishing the neural circuits underlying sex-specific behaviors.

fru P1 was shown to be sufficient to specify early, but not late, steps of the male courtship ritual, when FRUM was expressed in females in homologously-positioned cells in which it is normally expressed in males (Demir and Dickson, 2005; Manoli et al., 2005). Additionally, gynandromorph studies showed that if the CNS was genetically male, animals that contain female tissues in other body regions could perform all male courtship steps (Hall, 1977). Taken together, these results suggests there are additional gene(s), other than fru P1, that are sex-differentially utilized in the CNS that specify the correct neural circuitry for male behavior. dsx is an excellent candidate, given the role dsx plays in establishing sexually dimorphic numbers of neurons.

Our results may reconcile the observation that dsx is necessary, but not sufficient, for specifying aspects of male courtship behaviors (Taylor et al., 1994; Villella and Hall, 1996). Because the male courtship ritual is a sequence-dependent series of sub-behaviors, in which performance of late steps required completion of early steps (reviewed in Greenspan and Ferveur, 2000), if FRUM is required for establishing early male courtship steps, then in chromosomally XX dsxD pseudomales that lack FRUM, it would not be possible to assess if DSXM is sufficient to establish the potential for late male behaviors. The majority of DSX-expressing cells do not reside in regions previously mapped as important for the early steps (reviewed in Greenspan and Ferveur, 2000), consistent with this idea.

The neural patterning that underlies the potential for female behaviors remains minimally understood. In females, very few fru P1- expressing cells also express DSXF, with the exception of the abdominal ganglion of the VNC. The observation that fru P1-expressing cells play a role in female behaviors indicates that fru P1-expressing cells function in female reproductive behaviors (Kvitsiani and Dickson, 2006). The observation that there are very few DSX-expressing cells in the female brain, and they do not overlap the fru P1-expressing brain cells, suggests DSXF is most likely not sufficient to specify female behaviors, as was suggested by earlier results (Waterbury et al., 1999), but that DSXF- and fru P1-expressing cells collaborate to bring about the potential for female behaviors.

Here, we have shown that DSXF-dependent, sex-specific cell death in the TN1 region is the mechanism used to reach the correct number of DSX-expressing cells in females. It has been shown that in females, a small set of fru P1-expressing neurons undergoes cell death, thereby eliminating neurons that would go on to make male-typical projections (Kimura et al., 2005). Additionally, DSXF has been shown to control cell death in the developing embryonic gonad, which ultimately results in a sexual dimorphism in gonadal tissues (DeFalco et al., 2003). Our results, along with other studies undertaken in C. elegans and mammals (Conradt and Horvitz, 1999; Davis et al., 1996), underscore the importance of cell death as a mechanism by which differences between the sexes are established.

Supplementary Material

The DSX antibody is specific. There is no DSX expression in dsx null tissue. Shown is the brain (A) and VNC (B) of a transheterozygote of the dsx alleles dsxM+R15 and dsxD+R3. (C) DSX expression pattern is shown in a male brain in which DSXF has been overexpressed under the control of a heat shock promoter. DSX expression in wild type female (D) and male (E) aDN cells are shown. See schematic in Figure 1C for location of aDN cells.

ELAV, a protein expressed in the nuclei of neurons, co-localizes with DSX. Neurons in the posterior midbrain (A) and TN1 region of the VNC (B) co-express DSX (red) and ELAV (green). Note that ELAV is expressed in small, highly localized regions in the nucleus of some cells. 40X confocal sections of ~0.5 µm are shown.

DSX and fru P1 expressing cells co-localize at 48 hours APF, and in additional regions in the adult CNS.

(A) DSX and (B) fru P1-expressing cells co-localize (C; yellow) in the posterior midbrain of 48 hour APF males. (D) DSX and (E) fru P1-expressing cells co-localize (F) in the VNC of 48 hour APF males. (G) DSX and (H) fru P1-expressing cells (I) co-localization in the SN neurons, located near the subesophogeal ganglion of the brain, in adults. (J) DSX and (K) fru P1-expressing cells (L) co-localization in TN2 cells in the VNC in adults. 20X confocal sections (~1 µm thick) are shown. (A–F), and 40X confocal sections of ~0.5 µm are shown (G–L).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the Arbeitman laboratory for commentary and assistance. We thank J. Dalton for help with cell counts and M. Lebo for help making graphs. We thank D. Manoli, B. Baker, and B. Dickson for providing fru P1-GAL4 strains, G. Lee for the UAS-DSXF and UAS-DSXM strains, K. White for the XR38 and H99 strains, M. Siegal for the ix strains, and M. Guo for sending several strains. We thank S. Goodwin for helpful discussions, and a previous reviewer for the thoughtful suggestion of the ix experiment.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grants 1R01GM073039 and 1R03NS055646 awarded to MNA, USC start-up funding and USC Women In Science and Engineering funding.

abbreviations

- APF

after pupal formation

- BrdU

Bromodeoxyuridine

- CNS

central nervous system

- dsx

doublesex

- fru

fruitless

- ix

intersex

- pC1 and pC2

posterior cells 1 and 2

- PrMs

pro- and meso-thoracic ganglion region

- TN1

thoracic neurons 1

- TUNEL

terminal uridine deoxynucleotidyl transferase

- VNC

ventral nerve cord

- wpp

white pre-pupal

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ball GF, Balthazart J. Hormonal regulation of brain circuits mediating male sexual behavior in birds. Physiol Behav. 2004;83:329–346. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billeter JC, et al. Isoform-specific control of male neuronal differentiation and behavior in Drosophila by the fruitless gene. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1063–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtis KC, Baker BS. Drosophila doublesex gene controls somatic sexual differentiation by producing alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding related sex-specific polypeptides. Cell. 1989;56:997–1010. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90633-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen AE, et al. Sex comes in from the cold: the integration of sex and pattern. Trends Genet. 2002;18:510–516. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02769-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conradt B, Horvitz HR. The TRA-1A sex determination protein of C. elegans regulates sexually dimorphic cell deaths by repressing the egl-1 cell death activator gene. Cell. 1999;98:317–327. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81961-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EC, et al. The role of apoptosis in sexual differentiation of the rat sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area. Brain Res. 1996;734:10–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFalco TJ, et al. Sex-specific apoptosis regulates sexual dimorphism in the Drosophila embryonic gonad. Dev Cell. 2003;5:205–216. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir E, Dickson BJ. fruitless splicing specifies male courtship behavior in Drosophila. Cell. 2005;121:785–794. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan IW, Kaufman TC. Cytogenic analysis of chromosome 3 in Drosophila melanogaster: mapping of the proximal portion of the right arm. Genetics. 1975;80:733–752. doi: 10.1093/genetics/80.4.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdman SE, et al. Functional and genetic characterization of the oligomerization and DNA binding properties of the Drosophila doublesex proteins. Genetics. 1996;144:1639–1652. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth LC, et al. Analyses of RAS Regulation of Eye Development in Drosophila melanogaster. Methods Enzymol. 2005;407:711–721. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)07056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett-Engele CM, et al. intersex, a gene required for female sexual development in Drosophila, is expressed in both sexes and functions together with doublesex to regulate terminal differentiation. Development. 2002;129:4661–4675. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.20.4661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman TD, Arbeitman MN. Genomic and Functional Studies of Drosophila Sex Hierarchy Regulated Gene Expression in Adult Head and Nervous System Tissues. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan RJ, Ferveur JF. Courtship in Drosophila. Annu Rev Genet. 2000;34:205–232. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JC. Portions of the central nervous system controlling reproductive behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Behav Genet. 1977;7:291–312. doi: 10.1007/BF01066800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildreth PE. Doublesex, Recessive Gene That Transforms Both Males and Females of Drosophila into Intersexes. Genetics. 1965;51:659–678. doi: 10.1093/genetics/51.4.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K, et al. Fruitless specifies sexually dimorphic neural circuitry in the Drosophila brain. Nature. 2005;438:229–233. doi: 10.1038/nature04229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvitsiani D, Dickson BJ. Shared neural circuitry for female and male sexual behaviours in Drosophila. Current Biology. 2006;16:R355–R356. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G, et al. Spatial, temporal, and sexually dimorphic expression patterns of the fruitless gene in the Drosophila central nervous system. J Neurobiol. 2000;43:404–426. doi: 10.1002/1097-4695(20000615)43:4<404::aid-neu8>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G, et al. Doublesex gene expression in the central nervous system of Drosophila melanogaster. J Neurogenet. 2002;16:229–248. doi: 10.1080/01677060216292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoli DS, et al. Male-specific fruitless specifies the neural substrates of Drosophila courtship behaviour. Nature. 2005;436:395–400. doi: 10.1038/nature03859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoli DS, et al. Blueprints for behavior: genetic specification of neural circuitry for innate behaviors. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:444–451. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereanu W, Hartenstein V. Neural Lineages of the Drosophila Brain: A Three-Dimensional Digital Atlas of the Pattern of Lineage Location and Projection at the Late Larval Stage. 2006;Vol. 26:5534–5553. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4708-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, et al. reaper is required for neuroblast apoptosis during Drosophila development. Development. 2002;129:1467–1476. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.6.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout EJ, et al. The Sex-Determination Genes fruitless and doublesex Specify a Neural Substrate Required for Courtship Song. Curr Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinow S, et al. Programmed cell death in the Drosophila CNS is ecdysone-regulated and coupled with a specific ecdysone receptor isoform. 1993;Vol. 119:1251–1259. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinow S, White K. Characterization and spatial distribution of the ELAV protein during Drosophila melanogaster development. J Neurobiol. 1991;22:443–461. doi: 10.1002/neu.480220503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryner LC, et al. Control of male sexual behavior and sexual orientation in Drosophila by the fruitless gene. Cell. 1996;87:1079–1089. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81802-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirangi TR, et al. A double-switch system regulates male courtship behavior in male and female Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1435–1439. doi: 10.1038/ng1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simerly RB. Wired for reproduction: organization and development of sexually dimorphic circuits in the mammalian forebrain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:507–536. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockinger P, et al. Neural circuitry that governs Drosophila male courtship behavior. Cell. 2005;121:795–807. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BJ, Truman JW. Commitment of abdominal neuroblasts in Drosophila to a male or female fate is dependent on genes of the sex-determining hierarchy. Development. 1992;114:625–642. doi: 10.1242/dev.114.3.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BJ, et al. Behavioral and neurobiological implications of sex-determining factors in Drosophila. Dev Genet. 1994;15:275–296. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020150309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins L, Hall JC. Identification of Brain Sites Controlling Female Receptivity in Mosaics of DROSOPHILA MELANOGASTER. Genetics. 1983;103:179–195. doi: 10.1093/genetics/103.2.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villella A, Hall JC. Courtship anomalies caused by doublesex mutations in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1996;143:331–344. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.1.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Schilcher FaH, J C. Neural topography of courtship song in sex mosaics of Drosophila Melanogaster. J Comp Physiol. 1979;129:85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Waterbury JA. Analysis of the doublesex female protein in Drosophila melanogaster: role on sexual differentiation and behavior and dependence on intersex. Genetics. 1999;152:1653–1667. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.4.1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The DSX antibody is specific. There is no DSX expression in dsx null tissue. Shown is the brain (A) and VNC (B) of a transheterozygote of the dsx alleles dsxM+R15 and dsxD+R3. (C) DSX expression pattern is shown in a male brain in which DSXF has been overexpressed under the control of a heat shock promoter. DSX expression in wild type female (D) and male (E) aDN cells are shown. See schematic in Figure 1C for location of aDN cells.

ELAV, a protein expressed in the nuclei of neurons, co-localizes with DSX. Neurons in the posterior midbrain (A) and TN1 region of the VNC (B) co-express DSX (red) and ELAV (green). Note that ELAV is expressed in small, highly localized regions in the nucleus of some cells. 40X confocal sections of ~0.5 µm are shown.

DSX and fru P1 expressing cells co-localize at 48 hours APF, and in additional regions in the adult CNS.

(A) DSX and (B) fru P1-expressing cells co-localize (C; yellow) in the posterior midbrain of 48 hour APF males. (D) DSX and (E) fru P1-expressing cells co-localize (F) in the VNC of 48 hour APF males. (G) DSX and (H) fru P1-expressing cells (I) co-localization in the SN neurons, located near the subesophogeal ganglion of the brain, in adults. (J) DSX and (K) fru P1-expressing cells (L) co-localization in TN2 cells in the VNC in adults. 20X confocal sections (~1 µm thick) are shown. (A–F), and 40X confocal sections of ~0.5 µm are shown (G–L).