Abstract

Untreated human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is accompanied by reduced bone mineral density, which appears to be exacerbated by certain HIV protease inhibitors (PIs). The mechanisms leading to this apparent paradox, however, remain unclear. We have previously shown that, the HIV envelope glycoprotein gp120 used at levels similar those in plasmas of untreated HIV+ patients, induced expression of the osteoclast (OC) differentiation factor RANKL in CD4+ T cells. In addition, the HIV PI ritonavir abrogated the interferon-γ-mediated degradation of the RANKL nuclear adapter protein TRAF6, a physiological block to RANKL activity. Here, using oligonucleotide microarrays and quantitative polymerase chain reaction, we explored potential upstream mechanisms for these effects. Ritonavir, but not the HIV PIs indinavir or nelfinavir, up-regulated the production of transcripts for OC growth factors and the non-canonical Wnt Proteins 5B and 7B as well as activated promoters of nuclear factor-κB signaling, but suppressed genes involved in canonical Wnt signaling. Similarly, ritonavir blocked the cytoplasmic to nuclear translocation of β-catenin, the molecular node of the Wnt signaling pathway, in association with enhanced β-catenin ubiquitination. Exposure of OC precursors to LiCl, an inhibitor of the canonical Wnt antagonist GSK-3β, suppressed OC differentiation, as did adenovirus-mediated overexpression of β-catenin. These data identify, for the first time, a biologically relevant role for Wnt signaling via β-catenin in isolated OC precursors and the modulation of Wnt signaling by ritonavir. The reversal of these ritonavir-mediated changes by interferon-γ provides a model for possible intervention in this metabolic complication of HIV therapy.

Low bone mineral density (BMD) occurs in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-seropositive patients, whether naive to antiretroviral therapy (ART) or on effective ART, with prevalence estimates ranging up to 89%.1 A meta-analysis of 20 cross-sectional studies revealed a pooled odds ratio for osteopenia and osteoporosis of 6.4 and 3.7, respectively.2 Use of ART increased the odds for BMD suppression by 2.5-fold, with the greatest risk among those receiving a HIV protease inhibitor (PI).2

Several studies have attempted to address the paradox of an increased prevalence of HIV-linked bone mineral loss in patients on effective ART. Histomorphometric examination of iliac bone biopsies performed after double tetracycline labeling in HIV+, treatment-naive individuals revealed a decrease in bone formation rate and osteoclast (OC) proliferation index compared with normal controls, indicating a deficiency in both bone formation and resorption.3 Disturbances in synchronized bone remodeling have also been reflected by alterations in biochemical markers of bone turnover in untreated patients.4 However, the use of multiple drug regimens, and divergent agents within each drug class, are impediments to exploration of BMD regulation in HIV+ individuals on ART.

Uncontrolled clinical trials suggest that patients receiving the HIV PIs indinavir and nelfinavir experience an increase or stabilization in BMD, whereas those treated with ritonavir (RTV), the most widely used PI, have accelerated bone loss.5 But the statistical power to discriminate among effects of individual PIs on BMD is unlikely to be available for several years. Cell culture and bone explant models of OC differentiation and activity offer conflicting results, exacerbated by use of nonpharmacological doses of drug6 and the failure to consider the potential involvement of soluble HIV gene products, HIV-associated cytokines, and physiologic regulators of OC formation such as interferon (IFN)-γ.

For example, Jain and Lenhard7 found that RTV increased OC activity in a rat neonatal calvaria assay. In contrast, the Teitelbaum and Ross group8 reported that RTV decreased osteoclastogenesis among murine bone marrow precursor cells and inhibited recruitment of Src and TRAF6 (tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated protein 6) to lipid rafts, disrupting the OC cytoskeleton and its signaling pathways. The latter occurred in the presence of 10 to 20 μg/ml RTV. Our group found that low pharmacological concentrations of RTV (1 to 5 μmol/L, or 0.7 to 3.6 μg/ml), levels consistent with their use in contemporary PI-boosted ART regimens,6 produced something quite different: enhancement of OC differentiation and activity in murine and human precursor cells in vitro.9

We first showed that exposure of T cells to levels of HIV envelope glycoprotein gp120 present in plasmas of HIV+ treatment-naive patients induced production of the primary cytokine for OC differentiation, receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL). Supernatants from gp120-activated T cells supported differentiation of primary human macrophages into functional OCs.9 This could account for the association between HIV disease and osteopenia because serum RANKL levels are inversely proportional to BMD in infected patients.10 We also found that RTV, but not indinavir or nelfinavir, abrogated the primary physiological block to RANKL activity, (IFN)-γ-mediated degradation of the RANKL signaling adapter protein TRAF6.9 This could explain the apparent acceleration of BMD loss in patients treated with RTV. The effects of RTV were reversed by pharmacological levels of IFN-γ.9

We now explored potential upstream mechanisms of action of RTV on osteoclastogenesis. First, patterns of gene induction and suppression by RTV during RANKL-mediated differentiation of primary human precursor cells into OCs, and the impact of pharmacological levels of IFN-γ on these changes, were determined by large-scale oligonucleotide microarrays. Alterations in several transcripts potentially critical to osteoclastogenesis were then validated by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (Q-PCR). We documented up-regulation of messages for growth factors or their receptors involved in OC maturation, suppression of transcripts for antagonists of NK-κB signaling, and up-regulation of transcripts for noncanonical Wnt proteins, which can block canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling. This led us to explore the role of β-catenin, the molecular node of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway,11,12 in OC formation and its regulation by RTV. Several lines of evidence have established a role for Wnt and β-catenin in direct regulation of osteoblast differentiation and function, but previous studies of Wnt-related effects in OCs have been limited to alterations in soluble stromal or osteoblast products that modulate osteoblast-OC interaction.11,12 In contrast, our results define a direct role for Wnt/β-catenin in the OC, and its modulation by RTV and IFN-γ.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Human recombinant RANKL, M-CSF, GM-CSF, and IFN-γ and murine RANKL and IFN-γ were purchased from Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ. The HIV PIs RTV, indinavir, and nelfinavir were obtained from the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (Rockville, MD) and prepared in stock solutions of Me2SO (RTV, 27 mmol/L; indinavir and nelfinavir, 30 mmol/L), so that the final concentration of Me2SO in control or drug-treated cultures was 0.1%.

Isolation, Propagation, and Detection of Human OC Precursors

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were derived from heparinized venous blood by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque. They were cultured in RPMI 1640 plus 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum in polystyrene flasks for 2 to 4 hours at 37°C. Nonadherent cells were depleted by rinsing the flasks with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium; adherent cells were collected using a cell scraper. This population was not purified further; CD14+ monocyte/macrophages, absent contaminating T lymphocytes, produce few to no OCs, regardless of inducing agent.9 Normal donor adherent cells (1 to 2 × 106) per experimental condition were used for microarray studies. They were incubated in wells of 12-well tissue culture plates. Adherent cells (1 to 2 × 105) per experimental condition were used for all other protocols. They were incubated in four- or eight-well glass slide Lab-Tek chambers (Nalge Nunc, Naperville, IL). In preliminary experiments we evaluated both M-CSF (100 ng/ml) and GM-CSF (100 ng/ml) as co-factors for RANKL (50 ng/ml) in the differentiation of OCs from primary adherent cell populations. This was done because although several in vitro and in vivo studies document a positive role for GM-CSF in osteoclastogenesis,13,14 other experiments suggest that GM-CSF might inhibit OC formation driven by RANKL/M-CSF,15,16 and our own initial studies with RTV used only RANKL/M-CSF.9 In addition, circulating levels of GM-CSF are normal or elevated in HIV disease, whereas M-CSF levels might be suppressed.17 We used two healthy control donors (male, ages 35 and 40) and a single batch of fetal bovine serum for all experiments because the extent of OC formation might vary greatly using adherent cells and/or serum from different, ostensibly healthy donors.18 Physiological levels of IFN-γ (1 ng/ml, equivalent to 10 U/ml) were included in all cultures because IFN-γ concentrations are normal or increased in many HIV-positive patients,19,20 and low levels of RTV had a reduced impact on osteoclastogenesis in the absence of either autologous serum or physiological levels of IFN-γ.9

Osteoclastogenesis was quantitatively assessed using tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) activity as an index, as previously described.9 The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), with p-nitrophenol phosphate in acid phosphatase buffer as substrate, and enzyme activity measured colorimetrically at OD 405 nm. The validity of this assay as a measure of precursor cell differentiation into functional OC had been established in our laboratory by parallel determinations of membrane expression of TRAP and bone resorption function.9

Gene Expression Using High-Density Oligonucleotide Microarrays and Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

Each condition analyzed by large-scale microarrays involved three independent primary culture preparations and DNA microarray runs. Total RNA was extracted following the manufacturer’s protocol and purified by using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). Size integrity profiles of all RNAs were determined with a bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA), and RNA concentration was determined by Nanodrop (Wilmington, DE) spectrophotometry. All preparations had A260:280 OD ratios >1.8. Fifty ng of total RNA from each sample were amplified, yielding an average of 7 μg of single-stranded cDNA. This material was then fragmented and labeled with biotin using the Ovation Biotin system (NuGEN Technologies, Inc., San Carlos, CA). Expression patterns of 18,400 genes, ∼14,500 functionally characterized genes and ∼3900 expressed sequence tag clusters, were examined using GeneChip U133A2.0 arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Targets were prepared for array hybridization according to the Affymetric Expression Analysis Technical Manual, and hybridization conditions, array washing, staining (using GeneChip Fluidics Station 450), and scanning with GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G were performed according to this manual. Affymetrix GeneChip Operating Software was used for image acquisition.

For Q-PCR, reverse transcription was performed with 1 μg of total RNA followed by PCR using the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen) and LightCycler technology (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN). PCR conditions and methods for quantitation of target gene expression were as described elsewhere.21 Ten genes were examined: GM-CSF, HGF-R, IKBKE, MAKK7, DKK1, SFRP1, SFRP4, Wnt5B, Wnt6, and Wnt7B. The Gene Bank accession numbers are provided in Table 1. All data points represent three replications using stock primers and probes purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA).

Table 1.

Expression Profiles for Genes Modulated by HIV Protease Inhibitor Ritonavir and Reversed by Therapeutic Doses of IFN-γ in RANKL/GM-CSF Cultures of Normal Human Adherent Cells

| Gene bank | Short name | Name/description | RTV/Ct | IFN-γ + RTV/RTV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wnt signaling | ||||

| NM_012242 | DKK1 | Dickkopf homolog 1 | −32.05 | 2.42 |

| AF017987 | SFRP1 | Secreted frizzled-related protein 1 | 2.48 | −2.41 |

| NM_003014 | SFRP4 | Secreted frizzled-related protein 4 | 2.42 | −2.41 |

| AI927000 | SOSTDC1 | Sclerostin domain containing 1 | −5.07 | 2.17 |

| NM_003882 | WISP1 | WNT1 inducible signaling pathway protein 1 | −2.13 | 8.54 |

| NM 030775 | WNT5B | WNT5B | 4.29 | −6.06 |

| AY009401 | WNT6 | WNT6 | 2.03 | −5.98 |

| BE736994 | WNT7B | WNT7B | 10.01 | −9.25 |

| NM_003393 | WNT8 | WNT8 | −7.93 | 3.37 |

| Nitric oxide | ||||

| AF049656 | iNOS | Inducible NO synthetase | −12.18 | 3.06 |

| U31466 | NOS1 | Nitric oxide synthase 1 (neuronal) | −9.52 | 6.98 |

| AI005066 | AVP-R1A | Arginine-vasopressin receptor 1A | −2.2 | 2.49 |

| Osteoclast-osteoblast coupling | ||||

| BC000019 | CDH6 | cadherin 6, type 2, K-cadherin | 8.21 | −4.25 |

| Cytokines, growth factors and their receptors | ||||

| NM_006132 | BMP-1 | Bone morphogenetic protein 1 | −2.86 | 3.1 |

| M60316 | BMP-7 | Bone morphogenetic protein 7 | −3.01 | 8.11 |

| NM_016215 | EGFL7 | Epidermal growth factor-like 7 | −2.33 | 2.03 |

| NM_023932 | EGFL9 | Epidermal growth factor-like 9 | −3.02 | 2.99 |

| AF125253 | EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor | −3.34 | 3.24 |

| NM_020996 | FGF6 | Fibroblast growth factor 6 | −3.28 | 7.4 |

| NM_002010 | FGF9 | Fibroblast growth factor 9 | −6.62 | 6.1 |

| M63889 | FGFR1 | Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 | −10.1 | 14.06 |

| AB030078 | FGFR2 | Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 | −5.88 | 2.24 |

| AI972496 | IGF1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 | −2.77 | 3.89 |

| NM_021803 | IL-21 | Interleukin 21 | −2.06 | 2.74 |

| NM_000634 | IL8RA | Interleukin 8 receptor, α | −2.1 | 2.48 |

| NM_005092 | TNFSF18 | TNF superfamily, member 18 | −3.53 | 2.11 |

| NM_003242 | TGFBR2 | Transforming growth factor, β receptor II | −3.02 | 5.32 |

| AI986120 | LTBP1 | Latent transforming GF β binding protein | −4.34 | 4.15 |

| NM_00031 | PTH | Parathyroid hormone | 4.1 | −5.64 |

| NM_000564 | IL5RA | Interleukin 5 receptor, α | 2.13 | −8.77 |

| M11734 | GM-CSF | Colony stimulating factor 2 | 3.93 | −3.59 |

| NM_005448 | BMP-15 | Bone morphogenetic protein 15 | 19.67 | −8.13 |

| NM_004113 | FGF12 | Fibroblast growth factor 12 | 2.96 | −2.27 |

| NM_003868 | FGF16 | Fibroblast growth factor 16 | 8.73 | −7.57 |

| NM_005247 | FGF3 | Fibroblast growth factor 3 | 3.64 | −3.49 |

| NM_015883 | IGF1R | Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor | 5.94 | −8.92 |

| M22005 | IL-2 | Human interleukin 2 gene | 7.73 | −4.87 |

| NM_000879 | IL-5 | Interleukin 5 | 2.24 | −2.61 |

| NM_006207 | PDGFRL | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-like | 4.12 | −5 |

| BE870509 | HGF-R | Hepatocyte growth factor receptor | 2.42 | −2.7 |

| Programmed cell death | ||||

| NM_001459 | FLT3LG | Fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand | −2.25 | 7.41 |

| NM_013984 | NRG2 | Neuregulin 2 | −10.49 | 12.08 |

| NM_016109 | ANGPTL4 | Angiopoietin-like 4 | −10.88 | 7.11 |

| NM_003885 | CDK5R1 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 | −5.02 | 12.45 |

| AK021882 | ARHI | Ras homolog gene family, member I | −2.29 | 6.34 |

| NM_003841 | TNFRSF10C | TRAIL decoy receptor TR1 | 5.48 | −4.14 |

| AF021233 | TNFRSF10D | TRAIL decoy receptor TR2 | 4.29 | −4.76 |

| AF277724 | CDC25C | Cell division cycle 25C | 7.42 | −3.03 |

| NM_002825 | PTN | Pleiotrophin (heparin binding growth factor 8) | 9.38 | −3.67 |

| NM_015883 | IGF1R | Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor | 5.94 | −8.92 |

| AF069510 | NBCN1 | NaHCO3 co-transporter-1 | 2.27 | −3.7 |

| U72398 | BCL2L1 | Human Bcl-x β (bcl-x) gene, complete | 2.79 | −2.23 |

| RANKL, NF-κB signaling pathway | ||||

| AF006689 | MKK7 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 | −8.4 | 13.8 |

| AW340333 | IKBKE | Inhibitor of κ light chain enhancer | −4.27 | 5.18 |

| AF098518 | FHL2 | Four and a half LIM domains 1 | −5.78 | 5.51 |

| U09609 | NFKB2 | Nuclear factor of κ B-2 | 8.52 | −6.89 |

| U31601 | JAK3 | Janus kinase 3 | 7.88 | −5.43 |

| NM_006613 | GRAP | GRB2-related adaptor protein | 7.63 | −2.5 |

| L40992 | RUNX2 | Runt-related transcription factor 2 | 8.27 | −4.15 |

Fluorescent Immunolocalization of β-Catenin

Cells were seeded onto glass coverslips at an initial density of 1 × 105 for 2 hours, then incubated for 5 hours in four-well Lab-Tek II chamber slides. Medium was removed and cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 5 minutes and then incubated in 10% goat serum/0.1% Triton X-100 for 30 minutes. Excess serum was removed, and the cells incubated with 50 μl of a 7-μg/ml solution of mouse anti-β-catenin mAb conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (BD Transduction Laboratories, San Diego, CA) for 1.5 hours at room temperature. Coverslips were mounted in Vectorshield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and viewed under UV illumination.

β-Catenin Gene Transfer

Primary human adherent peripheral blood mononuclear cells (2 × 105) were plated in 0.2-ml culture medium containing RANKL, GM-CSF, and 1 ng/ml of IFN-γ in eight-well Lab-Tek II chamber slides. They were combined with 1.5 μl of a stock adenovirus (Ad) vector with E1 and E3 deletions, driven by a cytomegalovirus promoter containing a gene encoding either β-catenin-green fluorescent protein (GFP) or a control insert (Vector Biolabs, Philadelphia, PA) at a multiplicity of infection of 100. Virus was added at the initiation of culture and on days 3 and 5, together with removal of one-half of the culture medium and addition of fresh medium. Efficiency of transduction was estimated by immunofluorescence for GFP.

Proteasome-Based Assays

Ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of a GFP-based substrate was used, enabling quantification of drug effects on this proteasome-driven process in living cells, as previously described.22 The substrate consists of a mutated, uncleavable ubiquitin moiety, Ubi(G76V), fused to GFP. The mutation results in constitutive degradation of the protein, which can be blocked by classic proteasome inhibitors such as MG132 and lactacystin.21 The degree of inhibition of reporter protein degradation by the HIV PIs RTV and indinavir (0.16 to 40 μmol/L) in the U20Sps2042 Ubi(G76V)-GFP cell line was calculated as percent activity relative to buffer (Me2SO). Comparisons were made to lactacystin, MG132, and the anti-E3 ligase Ro106-9920 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals).

β-Catenin ubiquitination was examined in the murine OC precursor cell line RAW 264.7 by modification of previously published methods.23 Briefly, RAW cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium plus 10% fetal bovine serum and 1 ng/ml of murine IFN-γ. Cells (2 × 106) per condition were incubated with RTV (5 μmol/L) or buffer for 2 hours, followed by addition of murine RANKL (50 ng/ml), alone or with treatment doses of IFN-γ (10 ng/ml), for 20 minutes. A total of 0.5 mg of cell lysate from each condition was precleared with Protein G Plus-Agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) for 2 hours at 4°C, then incubated with rabbit anti-mouse polyclonal β-catenin antibody (1:500 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 4 hours at 4°C. Protein G Plus-Agarose was added for 1 hour, immunoprecipates were washed with lysis buffer and denatured at 90°C for 10 minutes in sample buffer, and the samples were resolved on a 4 to 15% polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose, probed with anti-ubiquitin mouse monoclonal IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated bovine anti-mouse IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences. Arlington Heights, IL).

Detection of proteasome components involved incubation of 2 × 106 RAW 264.7 cells with buffer or RTV (5 μmol/L) for 2 hours followed by addition of RANKL (50 ng/ml) with physiological (1 ng/ml) or pharmacological (10 ng/ml) levels of IFN-γ. Cells were harvested 6 hours later, whole lysates made, and 10 μg of protein per condition resolved on a 4 to 15% polyacrylamide gel. Western blotting for the 26S constitutive proteasome subunit 20S Y, and immunoproteasome components 11S regulator (PA28) and LMP2 using rabbit polyclonal antibodies (1:500 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was performed as for the β-catenin immunoblots.

Statistical Analyses

Differences in OC differentiation, quantitated by TRAP determinations, were compared using paired two-tailed t-tests. For the oligonucleotide microarray studies, target signal intensity from each chip was scaled to 500, and data normalization and pattern study performed with GeneSpring software (Agilent). Array data were globally normalized, followed by normalization of each gene to the median value of the samples. All measurements on each chip were then divided by the 50th percentile value. Per-chip normalization was then compared with per-gene normalization and those differing by more than or equal to twofold were reported. This threshold reflected two standard errors of the mean. Cluster gene analyses, exploring changes induced by RTV and reversed by treatment doses of IFN-γ, were performed using GeneSpring and DAVID 2.0 (Bioinformatic Resources 2006; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) databases.

Results

Cellular and Molecular Characterization of Primary Human OCs Induced in Vitro

Our initial system for induction of OC differentiation in primary human adherent cells used RANKL (50 to 100 ng/ml), M-CSF (100 ng/ml), and either autologous serum (15%) or physiological levels of IFN-γ (1 ng/ml).9 We repeated these experiments, substituting GM-CSF (100 ng/ml) for M-CSF. Cells with the phenotypic features of TRAP+, multinucleated giant cells were seen by days 4 to 5, with equivalent production of TRAP enzymatic activity on day 7 in both GM-CSF- and M-CSF-treated cultures (data not shown). By microarray analysis, mRNAs for four of six key OC markers, cataloged by others in RANKL/M-CSF-treated cells,24 were up-regulated in the RANKL/GM-CSF cultures by day 5 as compared with day 1 cultures. These genes included: RANK, 7.1-fold up-regulation; TRAP, 4.3-fold; calcitonin receptor, 4.4-fold; and cathepsins C, D, E, G, and S, 15.1- to 61.0-fold (data not shown).

Effect of RTV on RANKL-Mediated OC Differentiation, and Its Modulation by IFN-γ

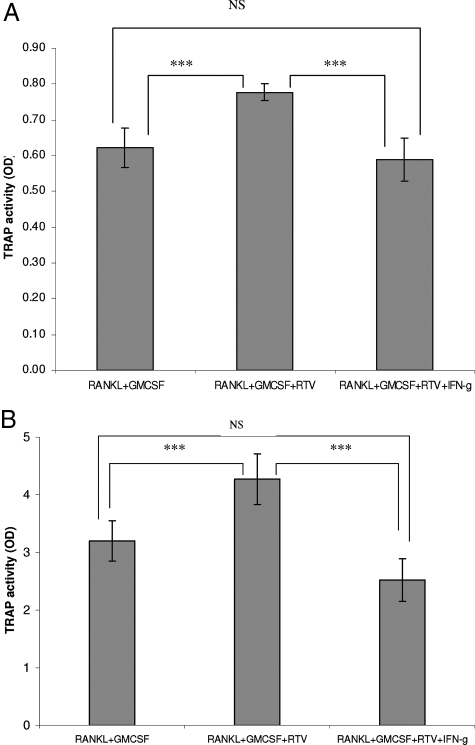

We had previously shown that low pharmacological levels of RTV, but not two other HIV PIs, indinavir and nelfinavir, enhanced differentiation of primary human and murine precursors cells into mature, functional OCs, as driven by RANKL/M-CSF in the presence of physiological levels of IFN-γ.9 Pharmacological levels of IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) blocked this enhancement.9 We now replicated these results using RANKL + GM-CSF. RTV (5 μmol/L) augmented TRAP activity in the presence of RANKL, GM-CSF, and 1 ng/ml of IFN-γ (Figure 1A; P < 0.001). Replacing the exogenous physiological IFN-γ with 15% autologous serum again revealed the enhancing effect of RTV on OC formation (Figure 1B; P < 0.001). Pharmacological doses of IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) inhibited TRAP activity under both conditions (Figure 1, A and B; P < 0.001). IFN-γ also suppressed OC formation in the absence of RTV (data not shown), replicating the work of other groups.23 Indinavir and nelfinavir had no effect on these processes at doses to 25 μmol/L (data not shown).

Figure 1.

RTV augments OC formation in cultures of normal human peripheral blood mononuclear adherent cells exposed to RANKL. Adherent cells (2.0 × 105) from a normal human donor were cultured in the presence of RANKL (50 ng/ml) and GM-CSF (100 ng/ml) for 7 days. RTV (5 μmol/L), pharmacological doses of IFN-γ (10 ng/ml), or both were added to certain cultures. Each point represents the mean of triplicate cultures. A: Physiological levels (1 ng/ml) of IFN-γ were included in all cultures. B: Fifteen percent autologous human serum was used in place of physiological levels of IFN-γ. ***P < 0.001.

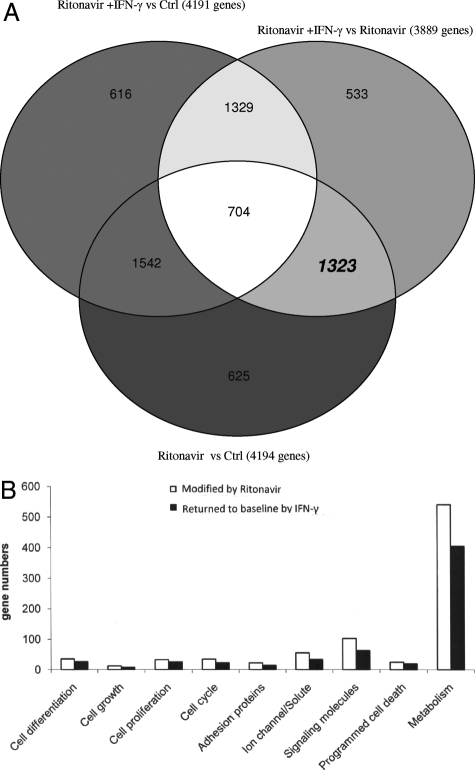

mRNAs isolated from parallel cultures of primary human adherent cells exposed to RANKL, GM-CSF, and 1 ng/ml of IFN-γ either alone (control culture), with RTV (5 μmol/L), or with RTV plus pharmacological levels (10 ng/ml) of IFN-γ, were then analyzed in large-scale DNA microarrays. Transcripts were considered significantly changed if they were altered more than or equal to twofold in two of the three microarray runs performed for each experimental condition. Venn diagrams were constructed based on these data. Genes (n = 4194) were affected in control versus RTV cultures on day 1 (Figure 2A), whereas only 178 genes were so altered on day 5 (data not shown). This is consistent with the kinetics of transcriptional changes from microarray data obtained with murine24,25 and human16 OC precursors exposed to other drugs that impact OC formation. Major alterations took place before day 3 for 96% of genes in our human system, versus 91% of genes in a murine OC model.24 Of the genes altered by RTV on day 1, 31.5% (1323 genes) normalized (reverted to within 1.9-fold of baseline control levels) on addition of treatment doses of IFN-γ (Figure 2A). By day 5, only 35 additional genes had been affected by RTV; virtually all of these changes (34 of 35) were reversed by IFN-γ (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Changes in gene expression assessed by DNA microarray analyses of normal human adherent cells exposed to RANKL/GM-CSF +/− RTV for 24 hours. Genes were considered significantly changed on addition of RTV (5 μmol/L), treatment doses of IFN-γ (10 ng/ml), or both if altered more than or equal to twofold from control values in two of three separate microarray experiments. A: Venn diagram comparing effects of RTV with and without IFN-γ. B: General classification of genes modulated by RTV, alone and in the presence of treatment doses of IFN-γ, with groupings determined by DAVID software.

Identity of Transcripts Affected by RTV, and Reversed by IFN-γ

Using the GeneSpring database and DAVID software, all transcripts that were altered by RTV and modulated by pharmacological doses of IFN-γ in day 1 cultures were segregated into nine general categories. These categories primarily related to cell differentiation, growth, and activity (Figure 2B). Expression values for genes in five of these categories—cell differentiation, cell growth, adhesion proteins, signaling molecules, and programmed cell death (apoptosis)—are provided in Table 1, and those alterations considered most relevant to OC biology are discussed below (a complete set of microarray data are presented in Supplemental Table S1 available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Nitric Oxide (NO)

Deficiency of inducible nitric oxide synthetase (iNOS) or pharmacological inhibition of NO increases OC formation and bone resorption in vitro and in vivo.26 In contrast, pharmacological levels of IFN-γ stimulate iNOS and NO production.26 We found that iNOS expression was suppressed by RTV, an effect reversed by IFN-γ (Table 1). In parallel, an inhibitory receptor for cytokine-induced NO production, arginine-vasopression receptor 1A,27 was down-regulated by RTV, and reversed by IFN-γ (Table 1).

Apoptosis

M-CSF and related growth factors can suppress OC apoptosis via rapid and sustained cellular alkalinization, related to up-regulation of the electroneutral NaHCO3 co-transporter NBCn1, leading to inhibition of caspase 8.28 NBCn1 was up-regulated by RTV, an effect blocked by IFN-γ (Table 1). Bcl-XL, an anti-apoptotic factor for OCs that is unaffected by RANKL or M-CSF29 was also up-regulated by RTV and blocked by IFN-γ (Table 1).

Cytokines and Growth Factors

Three key growth factors or their receptors involved in OC differentiation, GM-CSF, parathyroid hormone, and hepatocyte growth factor receptor (HGF-R), were up-regulated by RTV, with these effects reversed by IFN-γ (Table 1). HGF is of particular interest because it signals through the same tyrosine kinase receptor as M-CSF, phosphorylating common transducers and effectors.30 It can replace M-CSF in in vitro models of OC differentiation.30 Q-PCR was then used in an attempt to validate these changes. As shown in Table 2, RTV treatment was associated with a greater magnitude of increase in HGF-R than either indinavir or nelfinavir, and IFN-γ blocked this change.

Table 2.

Q-PCR Data for Genes Modulated by Different HIV Protease Inhibitors in RANKL/GM-CSF Cultures of Normal Human Adherent Cells

| Gene | RTV/Ctrl | RTV + IFN-γ/RTV | IDV/Ctrl | NFV/Ctrl |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM-CSF | 5.6 | −2.0 | 41.1 | 4.9 |

| HGF-R | 2.4 | 1.8 | 2.0 | -* |

| IKBKE | 1.6 | - | - | - |

| MAKK7 | −1.6 | 3.83 | 1.9 | - |

| Wnt5B | 38.4 | −9.0 | - | −2.5 |

| Wnt6 | - | - | - | - |

| Wnt7B | - | - | - | - |

| DKK1 | - | - | - | - |

| SFRP1 | - | - | - | - |

| SFRP4 | - | - | - | - |

Dashes indicate no change from baseline expression. RTV, ritonavir (5 μmol/L); IDV, indinavir (10 μmol/L); NFV, nelfinavir (10 μmol/L).

OC-Osteoblast Coupling

Cadherin-6 isoform 2 mediates interactions requiring cell-cell contact between OCs and osteoblasts; its suppression inhibits OC formation in co-culture models.31 Expression of cadherin-6i2 was increased by RTV and suppressed by IFN-γ (Table 1).

Signaling Pathways Related to Nuclear Factor (NF)-κB

NF-κB is rapidly induced in response to RANKL after the activation of IκB kinase (IKK)-1/2 and recruitment of Grb2-binding adapter protein (GRAP) to RANK.32 Suppression of either molecule blocks osteoclastogenesis in vitro and in vivo.33 RTV augmented NF-κB expression, an effect blocked by IFN-γ (Table 1). This was accompanied by modulation of three key regulators of NF-κB activation. RTV suppressed IKBKE, the IKK inhibitor, increased GRAP, and blocked expression of mitogen-activated protein kinase 7 (MKK7), which normally suppresses NF-κB activation in OC precursors in response to RANKL without affecting other signaling pathways34 (Table 1). All three effects were mitigated by IFN-γ (Table 1). In addition, FHL2 (four and a half LIM domain 2), a LIM domain-only protein that desensitizes OC precursors to RANKL by interacting with TRAF6,35 the obligate nuclear adapter protein for RANKL, was suppressed by RTV, an effect reversed by IFN-γ (Table 1). Q-PCR was used to examine changes in IKBKE and MKK7 after PI treatment. As shown in Table 2, alterations in IKBKE suggested by the large-scale microarray data were not confirmed by Q-PCR. MKK7, however, continued to show RTV-mediated suppression, an effect reversed by IFN-γ. In contrast, NFV had no impact on this transcript, and IDV showed a slight up-regulation (Table 2).

Signaling Pathways Related to Wnt

Wnt signaling in the osteoblast and mesenchymal osteoblast precursor requires the interaction of Wnt co-receptors LRP5 and LRP6 with frizzled receptors, processes suppressed by Dickkopf (Dkk1) and secreted frizzled-related proteins (SFRP)-1 and -4.11,36,37 Results from our initial microarray screen of OC precursors yielded conflicting patterns in terms of these inhibitors. Suggestive of a negative role for canonical Wnt signaling in OC differentiation were the RTV-mediated enhancement of transcripts for molecules that sequester Wnt ligands, SFRP-1 and -4, along with increases in Wnts 5B and 7B, which can activate noncanonical Wnt signalizing, thereby antagonizing the Wnt/β-catenin pathway37 (Table 1). These changes were reversed by IFN-γ (Table 1). Wnt 7B is of additional interest as its induction in articular cartilage is closely linked to rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis.38 However, DKK1 and sclerostin (SOST), two molecules that can sequester Wnt receptors LRP5 and LRP6 and thus suppress the ability of Wnt to stabilize β-catenin,37 were down-regulated by RTV (Table 1). Q-PCR was used to clarify these changes, and compare them to effects with HIV PIs IDV and NFV. As seen in Table 2, RTV failed to impact soluble Wnt receptor antagonists DKK1, SFRP1, or SFRP4. But there was a persistent, large elevation in Wnt5B transcripts (38.4-fold), a change seen only after RTV exposure, and reversed by IFN-γ.

Mimicking Canonical Wnt Signaling in OC Precursors Blocks OC Formation in Vitro

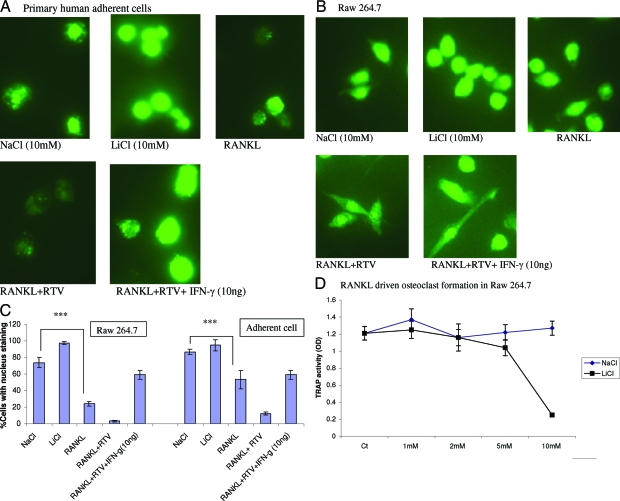

The above genomic data led us to explore the possibility of a direct inhibitory role for canonical Wnt and β-catenin in OC differentiation. We first examined nuclear translocation of β-catenin in OC precursors and the impact of RTV on this process. Primary human adherent cells and murine RAW 264.7 precursor cells were cultured in GM-CSF plus 1 ng/ml of IFN-γ for 1 hour followed by addition of RANKL with and without treatment doses of IFN-γ for 5 hours. RANKL depressed nuclear localization of β-catenin in both primary human (Figure 3, A and C) and murine (Figure 3, B and C) OC precursors. Nuclear transfer was further inhibited by RTV; this effect was reversed by pharmacological levels of IFN-γ in both cell types (Figure 3, A–C).

Figure 3.

Cytoplasmic to nuclear translocation of β-catenin in primary human OC precursors and murine RAW 264.7 cells. The intracellular localization of fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled β-catenin was examined by immunofluorescence in primary human adherent cells (A) or RAW 264.7 cells (B) cultured with 1 ng/ml IFN-γ, GM-CSF (100 ng/ml), and NaCl (10 mmol/L) or LiCl (10 mmol/L) for 1 hour, then exposed to RANKL (50 ng/ml), RANKL plus RTV (5 μmol/L), or RANKL, RTV, and IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) for 5 hours. The extent of nuclear staining for β-catenin is quantitated in C, representing three separate experiments. D: Concentrations of LiCl >2 mmol/L led to a marked suppression of TRAP+ OC formation in RAW 264.7 cells, assessed on day 7 (***P < 0.03).

We then explored the effect of LiCl on this process. Glycogen synthetase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), an enzyme that phosphorylates β-catenin in the cytoplasm targeting it for ubiquitination and degradation, is inhibited by LiCl.39 LiCl up-regulated cytoplasmic to nuclear translocation of β-catenin in both primary human adherent cells and RAW 264.7 cells compared with NaCl controls (Figure 3, A–C). This was accompanied by a dose-dependent suppression of OC formation, assessed in RAW cells cultured for 7 days in the continuous presence of RANKL, 1 ng/ml IFN-γ, and LiCl (Figure 3D; P < 0.03 for LiCl >2 mmol/L).

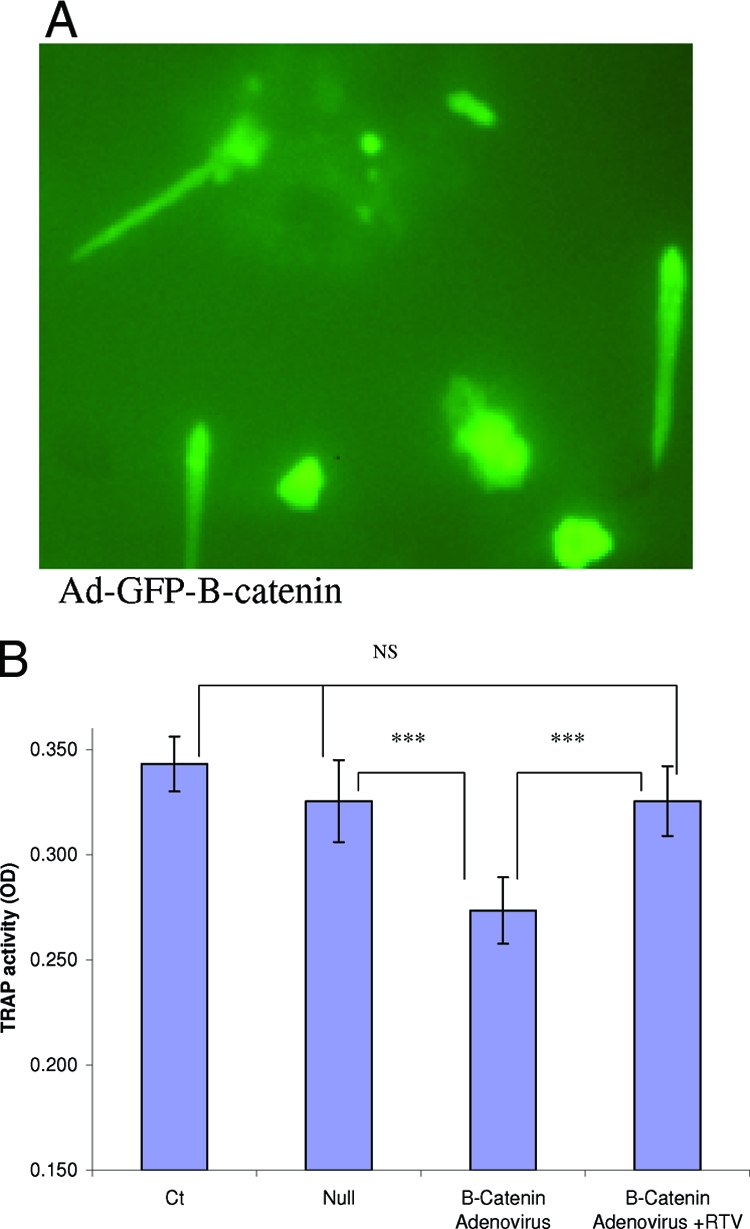

The impact of direct up-regulation of β-catenin on OC differentiation was also examined, using adenovirus-mediated gene transfer in primary human OC precursors. This led to β-catenin nuclear expression, with an efficiency >90% (Figure 4A), paralleled by suppression of OC formation (Figure 4B; P < 0.0005). Addition of RTV to cells transduced with Ad-β-catenin reversed the inhibition of OC formation (Figure 4B; P < 0.0003 comparing Ad-β-catenin to Ad-β-catenin + RTV; NS difference between control and Ad-β-catenin + RTV-treated cultures).

Figure 4.

Effect of adenovirus-mediated up-regulation of β-catenin on OCs. Primary human adherent mononuclear cells were infected with adenovirus vectors, either null or bearing a GFP-β-catenin transgene, on days 0, 3, and 5 of culture, together with RANKL (50 ng/ml) and 1 ng/ml of IFN-γ. A: The expression efficiency exceeded 90% on day 3. B: Ad-β-catenin, but not a control Ad vector, suppressed TRAP activity in these cells, as measured on day 7 (P < 0.0005). RTV rescued OC formation and TRAP activity when added to Ad-β-catenin-infected cells (P < 0.0003 comparing Ad-β-catenin + RTV cultures to Ad-β-catenin, with NS difference from controls). ***P < 0.001.

Potential Mechanisms for the Effect of RTV on Wnt-Related Signaling

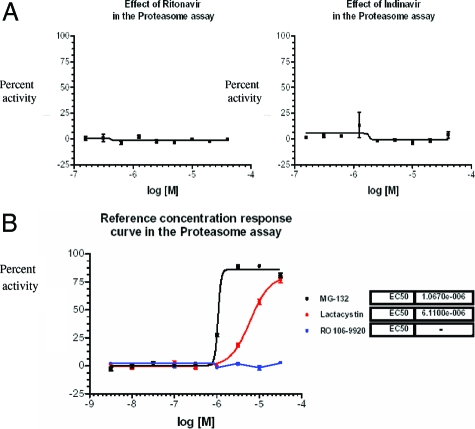

In vitro studies of other investigators demonstrating inhibition of OC differentiation and function by high doses of RTV focused on the proteasome because, at the concentrations used by these investigators (20 to 150 μmol/L), RTV is a potent and general inhibitor of proteasomal function.40,41 We first examined general proteasome function, profiling RTV and indinavir in an ubiquitin fusion degradation assay. Neither compound affected the constitutive degradation of Ubi(G76V), a GFP-tagged protein bearing an uncleavable ubiquitin moiety, at doses from 0.16 to 40 μmol/L (Figure 5A). In contrast, the general proteasome inhibitors MG132 and lactacystin blocked this pathway, with EC50s of ∼1 μmol/L and 8 μmol/L, respectively (Figure 5B). Specificity of this assay was demonstrated by the fact that a highly selective inhibitor of IκBα ubiquitination, the anti-E3 ligase Ro106-9920, had no effect on processing of Ubi(G76V)-GFP (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Effect of HIV PIs on proteasomal degradation of Ubi(G76V)-GFP. A: Varying concentrations of RTV or indinavir were added to U20S cells containing a mutated uncleavable ubiquitin moiety [Ubi(G76V)] fused to green fluorescence protein, resulting in constitutive degradation of the protein. Percent activities relative to buffer are shown. B: Data for pan-proteasome inhibitors MG-132 and lactacystin plus the E3 ligase inhibitor Ro106-9920.

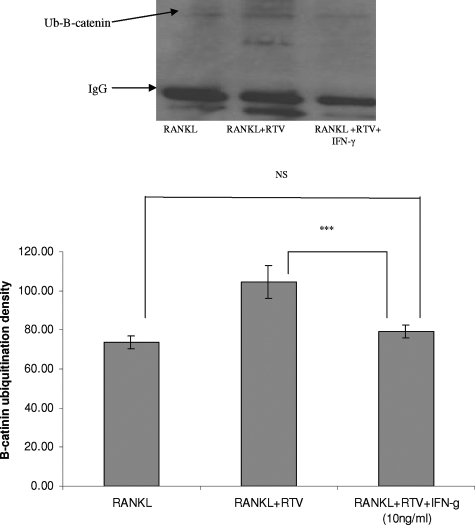

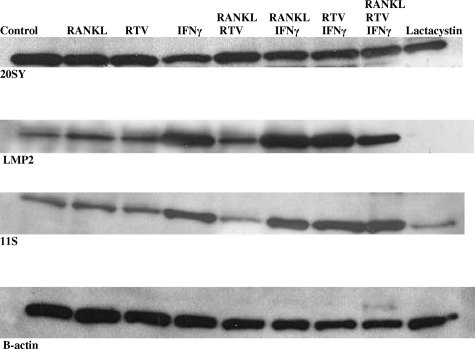

Next we examined the effect of RTV on ubiquitination of β-catenin. Five μmol/L RTV enhanced β-catenin ubiquitination over that seen in cells exposed only to RANKL (Figure 6). This enhancement was blocked by pharmacological levels of IFN-γ (Figure 6). In terms of potential mechanisms for the IFN-γ effect, we pre-exposed RAW 264.7 cells to RTV (5 μmol/L) followed by addition of physiological or treatment doses of IFN-γ and immunoblotting for components of both the constitutive proteasome and the immunoproteasome. As shown in Figure 7, treatment levels of IFN-γ increased components of the immunoproteasome while suppressing constitutive proteasome protein, consistent with the work of others.23,42 RTV inhibited expression of immunoproteasome components formed in the presence of physiological concentrations of IFN-γ, an effect reversed by treatment doses of IFN-γ, but had no effect on expression of components of the constitutive proteasome (Figure 7). A general inhibitor of proteasome function, lactacystin, suppressed constitutive proteasome protein (20SY) and completely blocked formation of immunoproteasome components (LMP2, 115) (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Effect of RTV and IFN-γ on RANKL-mediated induction of ubiquitination of β-catenin. RAW 264.7 cells were incubated with RTV (5 μmol/L) or buffer for 2 hours, followed by addition of RANKL (50 ng/ml), alone or with pharmacological doses of IFN-γ (10 ng/ml). Cell lysates were made after 30 minutes of incubation, immunoprecipitated with anti-β-catenin antibody, resolved on polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with an anti-Ub mouse mAb. Mono-ubiquitinated forms of β-catenin were quantitated by densitometry in three separate experiments. RTV elevated β-catenin ubiquitination when compared with control (RANKL only, ***P < 0.001) cultures, and this reverted to control levels in the presence of IFN-γ.

Figure 7.

Effect of pharmacological doses of IFN-γ on components of the constitutive proteasome and immunoproteasome in OC precursor cells. RAW 264.7 cells were exposed to buffer or RTV (5 μmol/L) for 1 hour followed by addition of RANKL (50 ng/ml), IFN-γ (10 ng/ml), or lactacystin (10 μmol/L) for 6 hours. Cells were then harvested and evaluated by Western blotting for components of the constitutive proteasome (20S, Y component) or immunoproteasome [11S (PA28) and LMP2].

Discussion

BMD is decreased in the setting of untreated HIV infection yet ART in general enhances the prevalence of bone mineral loss by 2.5-fold,2 accompanied by an increased risk for bone fracture.43,44 We have argued that the impact of certain antiretroviral drugs on bone mineral loss is much greater.9,20 We now establish that RTV, at low pharmacological concentrations, alters transcripts associated with pathways critical to enhancement of OC development and survival, changes reversed by pharmacological levels of IFN-γ. Experiments with both human and murine OC precursors confirm a role for modulation of β-catenin activity in these processes.

These results are consistent with the effects of RTV and IFN-γ in our in vitro models of OC differentiation,9 and parallel preliminary clinical observations of BMD loss in RTV-treated HIV+ patients.5,20,45,46 For example, we have an ongoing study assessing the impact of RTV-based ART versus other forms of anti-HIV therapy on bone mineralization in HIV+ versus HIV− postmenopausal women. Interim analysis showed higher levels of the three main peripheral markers for bone turnover, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, osteocalcin, and N-telopeptide (P values from 0.02 to 0.004), as well as BMD, assessed by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry of the total hip (P < 0.01) in RTV-treated versus treatment-naive HIV+ patients, and a trend for a decrease in total hip BMD for HIV+/RTV-treated patients versus those on other ART regimens (P = 0.12).20 These observations were recently supported by a prospective, nonrandomized study of a RTV-boosted PI regimen versus triple nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor therapy. The former was associated with significant loss of BMD.46 Furthermore, using an autologous serum OC induction assay, by which OC differentiation is quantitated in patient adherent cells cultured for 7 days only in the presence of 15% autologous serum, we found higher levels of OC formation in HIV+, RTV-treated patients (n = 8) versus HIV+ patients taking other antiretrovirals (n = 32; P < 0.02).20 This held true irrespective of a patient’s estimated duration of HIV infection or current CD4+ T-cell count.20

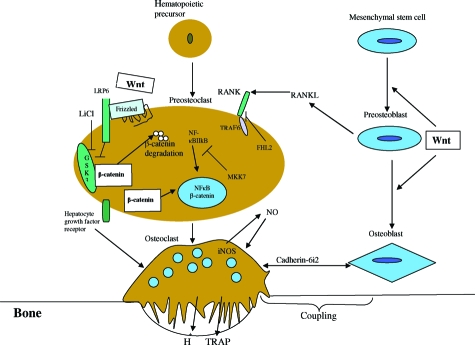

RTV and many other anti-HIV PIs can congruently affect a variety of cell systems.47 Based on our present data, we now offer probable mechanisms for OC enhancement by RTV that are unique to this HIV PI. They are summarized schematically in Figure 8 and described below. These changes were particularly striking for members of the NF-κB and Wnt signaling pathways. Additional experiments confirmed a role for direct Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the OC, apart from osteoblast-mediated phenomena.48

Figure 8.

Regulation of OC differentiation and OC-osteoblast coupling. Pathways identified by our microarray analyses as potentially modulated by RTV and reversed by pharmacological doses of IFN-γ are indicated. Based on additional experimental data, the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, critical to induction of osteoblast differentiation and activity, is postulated to also have a direct inhibitory role in OC differentiation. (Diagram format derived from References 37 and 48).

First, we documented suppression of the NF-κB inhibitory transcript MKK7 and enhancement of a key transcript providing positive signals for NF-κB activation, the Grb2-binding adapter protein. This is consistent with our previous work demonstrating RTV-mediated up-regulation of both NF-κB and JNK1 activation in RTV-treated cells.9 It is potentially important clinically because selective inhibition of NF-κB with cell-permeable peptides blocks osteoclastogenesis and prevents inflammatory bone destruction in vitro and in vivo.49 Second, a major impact of RTV on β-catenin signaling was seen, and these effects were completely reversed by pharmacological levels of IFN-γ. This included RTV-mediated up-regulation of Wnt 5B, a known antagonist of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling in other cell types.37 Wnt7B, a similar antagonist,37 was also enhanced by RTV in our initial microarray screen (Table 1), but we have not yet validated this result by Q-PCR. These results illuminate another potential avenue for intervention in HIV and RTV-linked BMD loss.

There is a paucity of studies on β-catenin-Wnt signaling in OCs. It is generally assumed that Wnt regulates OC formation and bone resorption exclusively through effects on the osteoblast. SFRP-1, secreted by the osteoblast, can inhibit osteoclastogenesis in co-cultures of osteoblasts and OC precursors through binding and removal of RANKL,50 and canonical Wnt signaling can up-regulate osteoblast expression of the soluble RANKL decoy osteoprotegerin, another negative regulator of OC differentiation.11,51,52 However, β-catenin also localizes to nuclei of isolated OCs in vitro11 and in vivo,53 consistent with endogenous Wnt signaling and transcription of Wnt target genes in these cells. Recent microarray studies of primary human osteoblasts exposed to 5 μmol/L RTV showed no impact of this drug on Wnt-related transcripts.54 We therefore postulated that an autocrine Wnt signaling pathway directly regulates OCs and can be modulated by RTV. Supporting data are provided by the LiCl-induced cytoplasmic to nuclear translocation of β-catenin in RANKL-treated OC precursors, paralleled by a decrease in OC formation, and the ability of Ad-mediated gene transfer of β-catenin to inhibit osteoclastogenesis. In contrast, RTV suppressed translocation of β-catenin, accompanied by an increase in its ubiquitination.

Although our results with Wnt/β-catenin relate to the isolated OC precursor, there are in vivo correlates: enhancement of bone mineralization has been documented in Lrp5-null mice treated with low levels of LiCl39; up-regulation of canonical Wnt protein Wnt 3a in mice leads to reduction in OC number55; and Msx2-based activation of canonical Wnt signals in mice resulted in a downward trend in OC number.56 In addition, genetically manipulated mice with stabilization of β-catenin show enhanced BMD and suppression of OC differentiation, with opposite results after disruption of β-catenin.12

Finally, it is striking that virtually all genes involved in OC biology whose transcripts were altered by RTV had these changes reversed by pharmacological levels of IFN-γ. There are at least three points at which IFN-γ-mediated transcriptional changes could suppress RTV-enhanced osteoclastogenesis. First, IFN-γ is known to induce the rapid degradation of TRAF6 via induction of the 11S regulator PA28 and other immunoproteasome components, leading to polyubiquitination of TRAF6 and targeting to the immunoproteasome.23 This results in inhibition of RANKL-induced activation of NF-κB and JNK.57 We had previously shown that therapeutic levels of IFN-γ could block NF-κB and JNK-1 activation elicited by RTV in OCs.9 We now show that IFN-γ up-regulates components of the immunoproteasome as it suppresses those of the constitutive proteasome. IFN-γ is known to be able to both down-regulate constitutive 26S proteasomes and decrease phosphorylation of a key 26S subunit, destabilizing any constitutive proteasomes that do form.58 Because ubiquitinated β-catenin appears to be degraded only by the constitutive proteasome,59 this would favor prolongation of β-catenin activity, and suppression of OC formation. Second, IFN-γ blocked RTV-mediated up-regulation of Smad3 (see supplementary Table S1 available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), a transcription factor that facilitates NF-κB signaling.60 Third, IFN-γ reversed the RTV-mediated down-regulation of iNOS, which leads to enhancement of NO production and induction of OC apoptosis.26 In preliminary experiments we confirmed the up-regulation of iNOS in human OC precursors by RTV (data not shown).

To summarize, the HIV PI RTV might accelerate BMD loss in vivo by augmenting several pathways critical to OC differentiation, acting via NF-κB and Wnt/β-catenin-linked signals. The ability of IFN-γ to completely reverse these changes might be of value in modulation of RTV-mediated BMD loss. Investigation of a direct role for Wnt and its inhibitors in OC biology, suggested by our studies, might open additional avenues for modulation of OC function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Betina Kerstin Lundholt, Ph.D., of BioImage, Inc., Soeborg, Denmark, for performing the ubiquitin degradation experiment; Dr. Anthony Brown of Weill Medical College-Cornell for helpful discussions Optical Microscopy Core facility at Weill Cornell Medical College; and the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program for providing the HIV protease inhibitors.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Jeffrey Laurence, M.D., Laboratory for AIDS Virus Research, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, 411 East 69th St., New York, NY 10021. E-mail: jlaurenc@med.cornell.edu.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants DK65511, AI65200, and HL55646) and the Angelo Donghia and Hagedorn Funds (to J.L.).

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

References

- Knobel H, Guelar A, Vallecillo G, Nogues X, Diez A. Osteopenia in HIV-infected patients: is it the disease or is it the treatment? AIDS. 2001;15:807–808. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200104130-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TT, Qaqish RB. Antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis: a meta-analytic review. AIDS. 2006;20:2165–2174. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801022eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano S, Marinoso ML, Soriano JC. Bone remodelling in human immunodeficiency virus-1-infected patients. A histomorphometric study. Bone. 1995;16:185–191. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(94)00028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aukrust P, Haug CJ, Ueland T, Lien E, Muller F, Espevik T, Bollerslev J, Froland SS. Decreased bone formative and enhanced resorptive markers in human immunodeficiency virus infection: indication of normalization of the bone-remodeling process during highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:145–150. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.1.5417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan D, Upton R, McKinnon E. Stable or increasing bone mineral density in HIV-infected patients treated with nelfinavir or indinavir. AIDS. 2001;15:1275–1280. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200107060-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurence J, Modarresi R. Modeling metabolic effects of the HIV protease inhibitor ritonavir in vitro. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1724–1725. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain RG, Lenhard JM. Select HIV protease inhibitors alter bone and fat metabolism ex vivo. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19247–19250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MW-H, Wei S, Faccio R, Takeshita S, Tebas P, Powderly WG, Teitelbaum SL, Ross FP. The HIV protease inhibitor ritonavir blocks osteoclastogenesis and function by impairing RANKL induced signaling. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:206–213. doi: 10.1172/JCI15797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakruddin JM, Laurence J. HIV envelope gp120-mediated regulation of osteoclastogenesis via receptor of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL) secretion and its modulation by certain HIV protease inhibitors through interferon-γ/RANKL cross-talk. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48251–48258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304676200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi M, Takahashi K, Yoshimoto E, Uno K, Kashara K, Mikasa K. Association between osteopenia/osteoporosis and the serum RANKL in HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2005;19:1240–1241. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000176231.24652.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer GJ, Utting JC, Etheridge SL, Arnett TR, Genever PG. Wnt signalling in osteoblasts regulates expression of the receptor activator of NFκB ligand and inhibits osteoclastogenesis in vitro. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:1283–1296. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass DA, II, Bialek P, Ahn JD, Starbuck M, Patei MS, Clevers H, Taketo MM, Long F, McMahon AP, Lang RA, Karsenty G. Canonical Wnt signaling in differentiated osteoblasts controls osteoclast differentiation. Dev Cell. 2005;8:751–764. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park BK, Zhang H, Zeng Q, Dai J, Keller ET, Giordano T, Gu K, Shah V, Zarbo RJ, McCauley L, Shi S, Chen S, Wang C-Y. NF-κB in breast cancer cells promotes osteolytic bone metastasis by inducing osteoclastogenesis via GM-CSF. Nat Med. 2007;13:62–69. doi: 10.1038/nm1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada N, Niwa S, Tsujimura T, Iwasaki T, Sugihara A, Futani J, Hayashi S, Okamura H, Akedo H, Terada N. Interleukin-18 and interleukin-12 synergistically inhibit osteoclastic bone-resorbing activity. Bone. 2002;30:901–908. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00722-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorny G, Shaw A, Oursler MJ. IL-6, LIF, and TNF-α regulation of GM-CSF inhibition of osteoclastogenesis in vitro. Exp Cell Res. 2004;294:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day CJ, Kim MS, Stephens SRJ, Simcock WE, Aitken CJ, Nicholson GC, Morrison NA. Gene array identification of osteoclast genes: differential inhibition of osteoclastogenesis by cyclosporin A and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor. J Cell Biochem. 2004;91:303–315. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esser R, Glienke W, Andressen R, Unger RE, Kreutz M, Rubsamen-Waigmann H, von Briesen H. Individual cell analysis of the cytokine repertoire in human immunodeficiency virus-1-infected monocytes/macrophages by a combination of immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization. Blood. 1998;91:4752–4760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susa M, Luong-Nguyen NH, Cappellen D, Zamurovic N, Gamse R. Human primary osteoclasts: in vitro generation and applications as pharmacological and clinical assay. J Transl Med. 2004;2:6. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs D, Hausen A, Reibnegger G, Werner ER, Werner-Felmayer G, Dierich MP, Wachter H. Interferon-γ concentrations are increased in sera from individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1989;2:158–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakruddin JM, Yin M, Laurence J: Pathophysiologic correlates of RANKL deregulation in HIV infection and its therapy. Program and Abstracts 12th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Feb 22–25, 2005, Boston, MA, Abst. 822 [Google Scholar]

- Hanriot D, Bello G, Ropars A, Seguin-Devaux C, Poitevin G, Grosjean S, Latger-Cannard V, Devaux Y, Zannad F, Regnault V, Lacolley P, Mertes P-M, Hess K, Longrois D. C-reactive protein induces pro- and anti-inflammatory effects, including activation of the liver X receptor α, on human monocytes. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99:558–569. doi: 10.1160/TH07-06-0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantuma NP, Lindsten K, Glas R, Jeline M, Masucci MG. Short-lived green fluorescent proteins for quantifying ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent proteolysis in living cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:538–543. doi: 10.1038/75406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayanagi H, Ogasawara K, Hida S, Chiba T, Murata S, Sato K, Takaoba A, Taniguchi T. T-cell-mediated regulation of osteoclastogenesis by signalling cross-talk between RANKL and IFN-γ. Nature. 2000;408:600–605. doi: 10.1038/35046102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappellen D, Luong-Nguyen N-H, Bongiovanni S, Grenet O, Wanke C, Susa M. Transcriptional program of mouse osteoclast differentiation governed by the macrophage colony-stimulating factor and the ligand for the receptor of NFκB. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21971–21982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida N, Hayashi K, Hoshijima M, Ogawa T, Koga S, Miyatake Y, Kumegawa M, Kimura T, Takeya T. Large scale gene expression analysis of osteoclastogenesis in vitro and elucidation of NFAT2 as a key regulator. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41147–41156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Yu X, Collin-Osdoby P, Osdoby P. RANKL stimulates inducible nitric-oxide synthetase expression and nitric oxide production in developing osteoclasts. An autocrine negative feedback mechanism triggered by RANKL-induced interferon-β via NF-κB that restrains osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15809–15820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513225200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagumdzija A, Pernow Y, Bucht E, Gonon A, Petersson M. The effects of arg-vasopression on osteoblast-like cells in endothelial nitric oxide synthetase-knockout mice and their wild-type counterparts. Peptides. 2005;26:1661–1666. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouyer P, Sakai H, Itokawa T, Kawano T, Fulton CM, Boron WF, Insogna KI. Colony-stimulating factor-1 increases osteoclast intracellular pH and promotes survival, via the electroneutral Na/HCO3 cotransporter NBCn1. Endocrinology. 2007;148:831–840. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey DL, Tan HL, Lu J, Kaufman S, Van G, Qiu W, Rattan A, Scully S, Fletcher F, Juan T, Kelley M, Burgess TL, Boyle WJ, Polverino AJ. Osteoprotegerin ligand modulates murine osteoclast survival in vitro and in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:435–448. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64556-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamopoulos IE, Xia Z, Lau YS, Athanasou NA. Hepatocyte growth factor can substitute for M-CSF to support osteoclastogenesis. BBRC. 2006;350:478–483. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbalaviele G, Nishimura R, Myoi A, Niewolna M, Reddy SV, Chen D, Feng J, Roodman D, Mundy GR, Yoneda T. Cadherin-6 mediates the heterotypic interactions between the hemopoietic osteoclast cell lineage and stromal cells in a murine model of osteoclast differentiation. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1467–1476. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.6.1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao D, Epple H, Uthgenannt B, Novack DV, Faccio R. PLCγ2 regulates osteoclastogenesis via its interaction with ITAM proteins and GAB2. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2869–2879. doi: 10.1172/JCI28775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruocco MG, Maeda S, Park JM, Lawrence T, Hsu L-C, Cao Y, Schett G, Wagner EF, Karin M. IκB kinase (IKK)β, but not IKKα, is a critical mediator of osteoclast survival and is required for inflammation-induced bone loss. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1677–1687. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto A, Miyazaki T, Kadono Y, Takayanagi H, Miura T, Nishina H, Katada T, Wakabayashi K, Oda H, Nakamura K, Tanaka S. Possible involvement of IκB kinase 2 and MKK7 in osteoclastogenesis induced by receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:612–621. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.4.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai S, Kitaura H, Zhao H, Chen J, Muller JM, Schuk R, Darnay B, Novack DV, Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL. FHL2 inhibits the activated osteoclast in a TRAF6-dependent manner. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2742–2751. doi: 10.1172/JCI24921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass DA, II, Karsenty G. Minireview: in vivo analysis of Wnt signaling in bone. Endocrinology. 2007;148:2630–2634. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan V, Bryant HU, MacDougal OA. Regulation of bone mass by Wnt signaling. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1202–1209. doi: 10.1172/JCI28551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Nawata M, Wakitani S. Expression profiles and functional analysis of Wnt-related genes in human joint disorders. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:97–105. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62957-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clément-Lacroix P, Ai M, Morvan F, Roman-Roman S, Vayssiere B, Belleville C, Estrera K, Warman ML, Baron R, Rawadi G. Lrp5-independent activation of Wnt signaling by lithium chloride increases bone formation and bone mass in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17406–17411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505259102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidtke G, Holzhutter H-G, Bogyo M, Kairies N, Groll M, de Giuli R, Emch S, Groettrup M. How an inhibitor of the HIV-1 protease modulates proteasome activity. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:35734–35740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.50.35734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- André P, Groettrup M, Klenerman P, de Giuli R, Booth BL, Jr, Cerundolo V, Zinkernagel RM, Lotteau V. An inhibitor of HIV-1 protease modulates proteasome activity, antigen presentation, and T cell responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13120–13124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heink S, Ludwig D, Kloetzel P-M, Kruger E. IFN-γ-induced immune adaptation of the proteasome system is an accelerated and transient response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9241–9246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501711102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten JH, Freeman R, Howard AA, Floris-Moore M, Lo Y, Klein RS. Decreased bone mineral density and increased fracture risk in aging men with or at risk for HIV infection. AIDS. 2007;21:617–623. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280148c05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triant VA, Brown TT, Lee H, Grinspoon SK. Fracture prevalence among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected versus non-HIV-infected patients in a large U.S. healthcare system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3499–3504. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piliero PJ, Gianoukakis AG. Ritonavir-associated hyperparathyroidism, osteopenia and bone pain. AIDS. 2002;16:1565–1566. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200207260-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas P, Gorgolas M, Garcia-Delgado R, Diaz-Curiel M, Goyenechea A, Fernandez-Guerrero ML. Evolution of bone mineral density in AIDS patients on treatment with zidovudine/lamivudine plus abacavir or lopinavir/ritonavir. HIV Med. 2008;9:89–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Pandak WM, Jr, Lydall V, Natarajan R, Hylemon PB. HIV protease inhibitors activate the unfolded protein response in macrophages: implication for atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:690–700. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.012898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldring SR, Goldring MB. Eating bone or adding to it: the Wnt pathway decides. Nat Med. 2007;13:133–134. doi: 10.1038/nm0207-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimi E, Aoki K, Saito H, D'Acquisto F, May MJ, Nakamura I, Sudo T, Kojima T, Okamoto F, Fukushima H, Okabe K, Ohya K, Ghosh S. Selective inhibition of NF-κB blocks osteoclastogenesis and prevents inflammatory bone destruction in vivo. Nat Med. 2004;10:617–624. doi: 10.1038/nm1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häusler KD, Horwood NJ, Yoshiro C, Fisher JL, Ellis J, Martin TJ, Rubin JS, Gillespie MT. Secreted frizzled-related protein-1 inhibits RANKL-dependent osteoclast formation. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:1873–1881. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass DA, II, Karsenty G. Canonical Wnt signaling in osteoblasts is required for osteoclast differentiation. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1068:117–130. doi: 10.1196/annals.1346.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diarra D, Stolina M, Polzer K, Zwerina J, Ominsky MS, Dwyer D, Korb A, Smolen J, Hoffman M, Scheinecker C, van der Heide D, Landewe R, Lacey D, Richards WG, Schett G. Dickkopf-1 is a master regulator of joint remodeling. Nat Med. 2007;13:156–163. doi: 10.1038/nm1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan H, Bubb VJ, Sirimujalin R, Millward-Sadler SJ, Salter DM. Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), β-catenin, and cadherin are expressed in human bone and cartilage. Histopathology. 2001;39:611–619. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2001.01287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malizia AP, Cotter E, Crew N, Powderly WG, Doran PP. HIV protease inhibitors selectively induce gene expression alterations associated with reduced calcium deposition in primary human osteoblasts. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23:243–250. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang Y-W, Shaughnessy JD, Jr, Yaccoby S. Wnt3a signaling within bone inhibits multiple myeloma bone disease and tumor growth. Blood. 2008;112:374–382. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-120253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S-L, Shao J-S, Cai J, Sierra OL, Towler DA. Msx2 exerts bone anabolism via canonical Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20505–20522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800851200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett IR, Chen D, Gutierrez G, Zhao M, Escobedo A, Rossini G, Harris SE, Gallwitz W, Kim KB, Hu S, Crews CM, Mundy GR. Selective inhibitors of the osteoblast proteasome stimulate bone formation in vivo and in vitro. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1771–1782. doi: 10.1172/JCI16198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose S, Stratford FLL, Broadfoot KI, Mason GGF, Rivett AJ. Phosphorylation of 20S proteasome alpha subunit C8 (α7) stabilizes the 26S proteasome and plays a role in the regulation of proteasome complexes by γ-interferon. Biochem J. 2004;378:177–184. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J-H, Ghosn C, Hinchman C, Forbes C, Wang J, Snider N, Cordrey A, Zhao Y, Chandraratna RAS. Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)-independent regulation of β-catenin degradation via a retinoid X receptor-mediated pathway. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29954–29962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304761200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa L, Doody J, Massague J. Inhibition of transforming growth factor-β/SMAD signalling by the interferon-γ/STAT pathway. Nature. 1999;397:710–713. doi: 10.1038/17826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.