Abstract

Complementary synthetic routes to a new class of near IR fluorophores are described. These allow facile access (four synthetic steps) to the core fluorophore and substituted derivatives with emissions between 740 and 780 nm in good quantum yields.

Complementary synthetic routes to a new class of near IR fluorophores are described. These allow facile access (four synthetic steps) to the core fluorophore and substituted derivatives with emissions between 740 and 780 nm in good quantum yields.

Surprisingly few fluorescent probes emit in the near-IR region with high quantum yields.1, 2 Such compounds are valuable for intracellular imaging because autofluorescence in cells tends to obscure emissions at wavelengths below approximately 550 nm, but this factor becomes less of an issue at longer wavelengths. Probes that emit in the 750 – 900 nm region are, therefore, relatively easy to visualize in vivo.3 Cyanine dyes are currently the most widely used probes for this wavelength region, but their quantum yields and photostabilities are sub-optimal.4 Thus there is need for new fluorescent probes that emit efficiently above 750 nm.

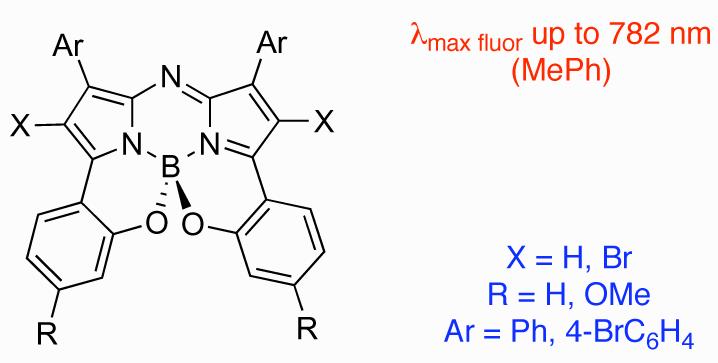

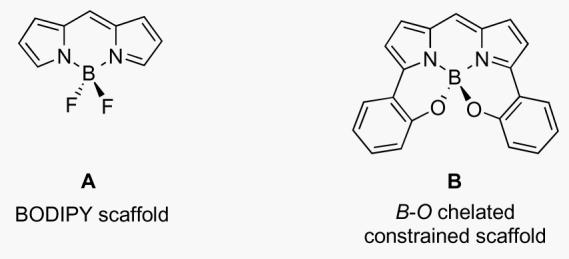

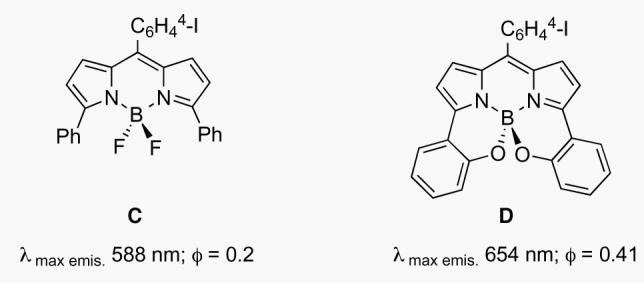

Dyes based on the 5-6-5 fused BODIPY ring system A are popular in biotechnology because they tend to have relatively sharp fluorescence emission characteristics, and high quantum yields.5 However, the emission wavelengths of most BODIPY dyes are between 530 and 630 nm, and this is sub-optimal for intracellular or tissue imaging. Previous work by Burgess et al,6-8 and others,9,10 successfully explored a modification strategy for shifting BODIPY-fluorescence emissions to the red (Figure 1). Adaptation of the core fluorophore scaffold by intramolecular B-O ring formation to produce the 6,6-5-6-5-6,6 ring system B gave a ca 65 nm bathochromatic shift (compare C and D),11 but the fluorescence emission wavelengths were less than 700 nm.12

Figure 1.

Comparison of fluorescence emission wavelength maxima and quantum yields (in CHCl3) for: A BODIPY class and a B-O ring-extended class B.

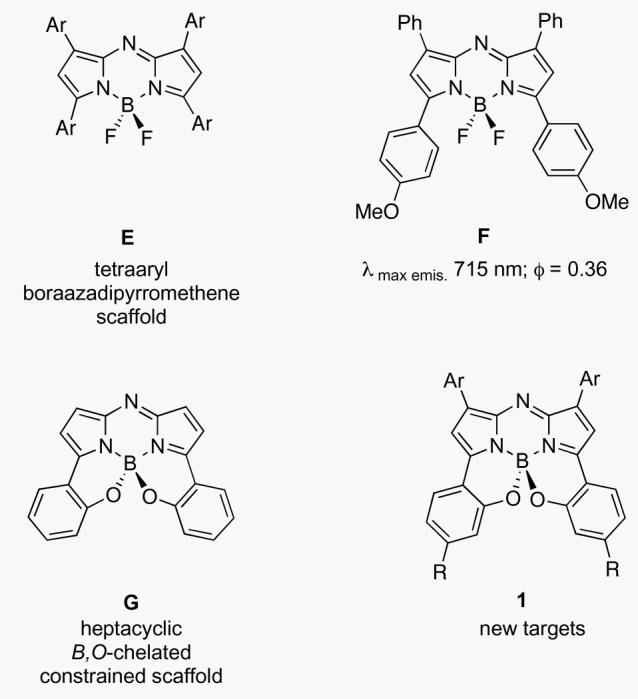

O'Shea and co-workers have demonstrated that BF2 chelated tetraaryl-substituted azadipyrromethenes E, fluoresce with wavelength maxima between 670-720 nm with para-oriented electron donating groups being particularly effective in enhancing the red-shifted fluorescence, eg F (Figure 2).13-19 This is close to the 750 - 1,400 nm region at which light permeation through tissue is most effective. Subsequently, it was shown that derivatives with extended aromatic groups do emit in near-IR region.20 The premise of this paper is that it would be advantagous to “hybridize” the structure B and E to shift their emissions beyond 750 nm. On the basis of the structures shown in Figure 1 it was therefore logical to introduce an intramolecular B,O-chelate on a tetraaryl aza-BODIPY scaffold eg G. The studies described here feature compound 1 of this type; it emerges that they can emit in this region.

Figure 2.

Representative fluorescence emission wavelength maximum and quantum yield (in CHCl3) for E BF2-chelated tetraarylazadipyrromethenes and a new B-O ring extended class G.

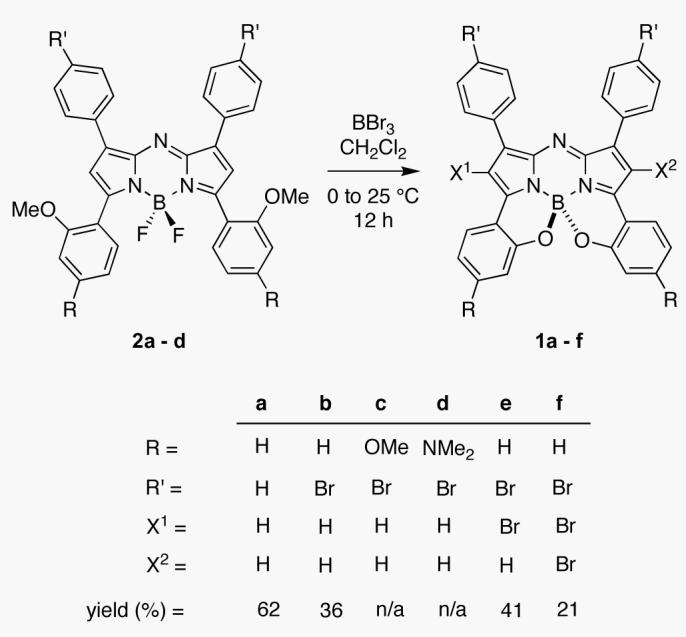

Scheme 1 shows one approach to the synthesis of the target class 1 from the precursors 2a-d which can be synthesized in four steps from commercially available materials.21 A solid state X-ray structure determination of 2a illustrated that both 2-MeOC6H4 rings lie out of the plane of the central chromophore with torsion angles of 42.7° and 61.4° (Supporting Information). Compounds 1 were obtained from the corresponding 2 by treatment with boron tribromide in dichloromethane. We anticipated that demethylation of the methoxy groups with BBr3 to the corresponding bisphenols would lead to spontaneous cyclization giving the target materials 1. This proved correct for substrates 1a and 1b with products isolated in 61 and 36% yields respectively following chromatography. Furthermore, in addition to 1a and 1b, compounds corresponding to bromination of the pyrrole ring i.e. 1e - f were also observed. This is somewhat surprising since this did not occur for synthesis of the B class, but it is also potentially useful if the compounds are to be modified further.6 Systems 1c and 1d were not air-stable, and were not isolated.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Near-IR Fluorophores 1

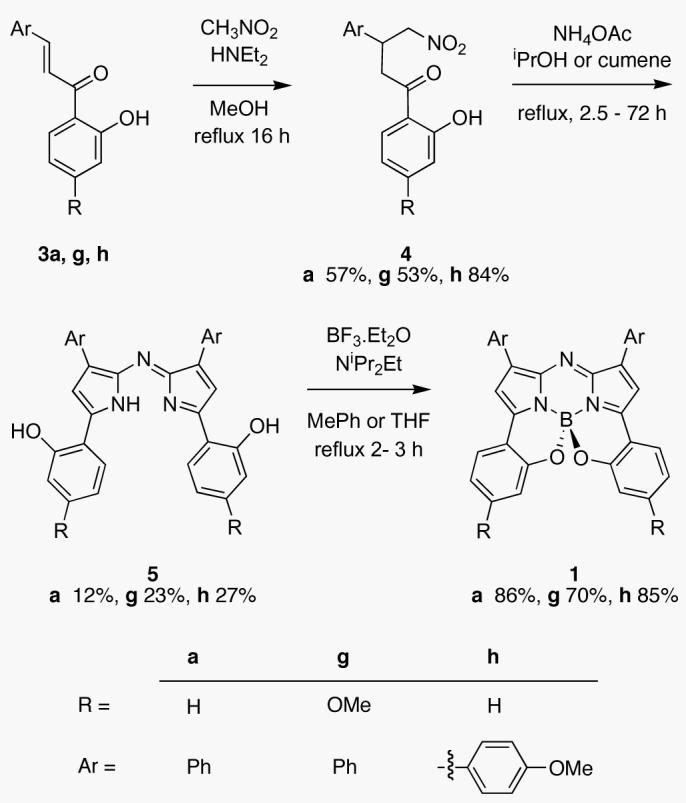

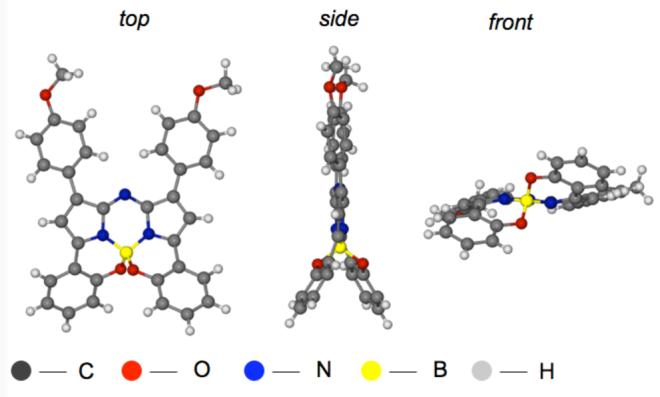

Prior experience with aza-BODIPY derivatives such as F indicated that electron releasing R-groups might red-shift the fluorescence maxima of the B,O-chelated compounds 1. An alternative route, which avoids the aryl demethylation conditions used in Scheme 1, was therefore developed to allow inclusion of 4-methoxy groups (Scheme 2). This required conjugate addition of nitromethane to the chalcones 3a, g, h. Heating of 4a, g, h with an ammonium source gave phenolic substituted azadipyrromethens 5a,g , h. Fluorophores 1a, g, h were obtained in a one-pot BF2 chelation and intramolecular phenolic oxygen – fluorine displacement thereby generating the structurally constraining benzo{1,3,2}oxazaborinine rings. Presumably this synthetic route could be modified to include functional groups in place of the p-methoxy position of 1g,h for bioconjugation. Single crystal X-ray structures for 1h and 1f were obtained (Figure 3 and Supporting Information). The benzo fused 6,6-5-6-5-6,6 ring structure was shown to be tetrahedral around the boron atom. Consequently the molecule is chiral just as for the other B,O-chelates B.

Scheme 2.

Four steps synthesis to Near-IR Fluorophores 1

Figure 3.

X-Ray crystal structure of 1h. Selected bond lengths B-O 1.471(2) and 1.476(2); B-N 1.513(2) and 1.514(2); bond angles O-B-O 108.0(1)° and N-B-N 103.9(1)°.

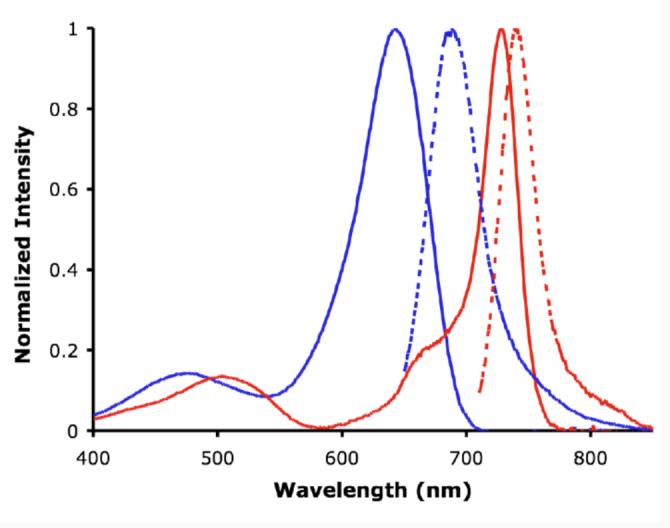

Figure 4 highlights the dramatic spectroscopic contrast between the constrained derivative 1a and its unconstrained precursor 2a. Restrictions caused by the B-O bonds in 1a gave bathochromic shifts in both the absorption (86 nm) and emission maxima (58 nm) and over a seven fold increase in the quantum yield from 0.07 to 0.51 (Figure 4, Table 1, entries 1 and 2). These trends were observed for all derivatives of 1 with additional hypso- and bathochromatic shifts due to the further influence of the aryl and pyrrole substituents.

Figure 4.

Normalized absorbance (solid line) and emission (dashed line) for 2a (blue) and 1a (red) in CHCl3.

Table 1.

Photophysical Properties of 1 in Toluene.

| entry | λmax (nm) |

λf (nm) |

fwhm (nm)a |

Φfb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2a | 642 | 688 | 43 | 0.0710 |

| 2 | 1a | 728 | 746 | 36 | 0.51 |

| 3 | 1b | 745 | 760 | 36 | 0.46 |

| 4 | 1e | 747 | 769 | 38 | 0.35 |

| 5 | 1f | 755 | 776 | 36 | 0.36 |

| 6 | 1g | 765 | 782 | 40 | 0.18c |

| 7 | 1h | 728 | 742 | 36 | 0.17c |

Full width at half-maximum height.

Measured in 1% pyridinein toluene. ZnPtc (Φf 0.30) was used as standard

Measured in CHCl3.

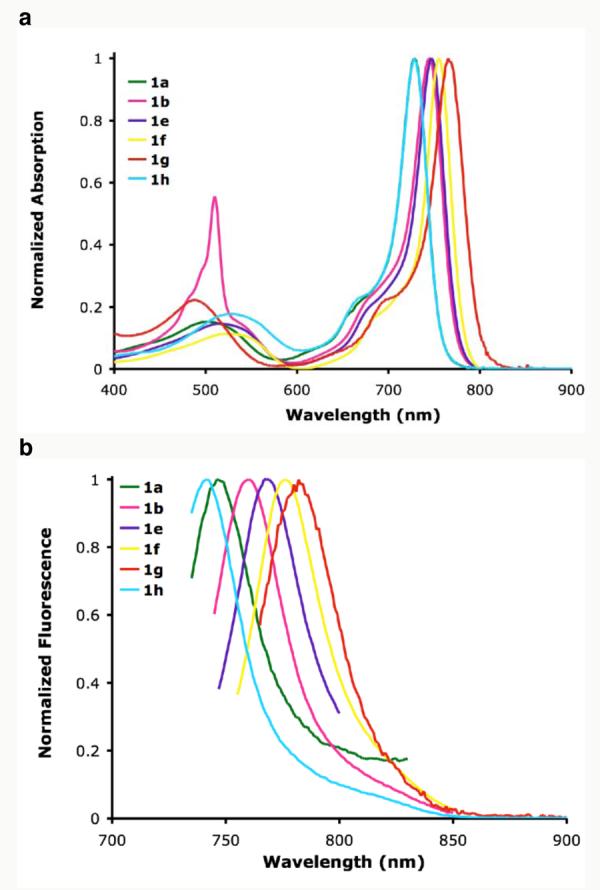

Introduction of bromine- (1b) and methoxy (1h) aryl-substituents resulted in a 14 nm bathochromic and 4 nm hypsochromic shift for fluorescence maxima respectively when compared to 1a (entries 3 and 7). The longest absorbance/emission wavelength maxima (765/782 nm) were observed for derivative 1g containing electron donating methoxy substituents on the benzo{1,3,2}oxazaborinine rings (entry 6). This pronounced red-shift for fluorescence maximum of 94 nm when compared to 2a and 36 nm from 1a places it into the near-IR spectral region (Figure 5). Interestingly, the tetrabromo derivative 1f also had red-shifted absorption and emission profiles and the substituent did not result in a pronounced quenching of the fluorescence (entry 5).14

Figure 5.

Normalized absorbance (a); and (b) emission spectra (excited at the respective λmax) of 1a, b, e, f, g and h in toluene

In addition the absorbance spectra showed only a small sensitivity to solvent polarity. For example, the λmax abs of 1g in DMF is only red shifted by 5 nm when compared to 761 nm in cyclohexane (Table 2). Inspection of fluorescence maxima for 1g and 1h revealed a small blue shift trend in polar solvents (Table 3 and Supporting Information). Large Stokes shift values of 34-56 nm in variuos solvents were recorded for 2a, however this trend did not translate to the conformationally restricted fluorophores 1a, g (9 and 19 nm, Table 3).

Table 2.

Effects of the solvent polarity on the absorption.

| λmax abs (fwhm)a / nm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHCl3 | THF | Dioxane | Cyclohexane | DMF | |

| 2a | 642 (67) | 643 (68) | 636 (67) | 640 (62) | 643 (71) |

| 1a | 725 (33) | 724 (34) | 724 (34) | 724 (31) | 725 (36) |

| 1g | 764 (43) | 764 (47) | 764 (42) | 761 (37) | 766 (47) |

Full width at half-maximum height.

Table 3.

Effects of the solvent polarity on the fluorescence.

| λmax abs (Stokes shift) / nm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHCl3 | THF | Dioxane | Cyclohexane | DMF | |

| 2a | 686 (44) | 682 (39) | 681 (45) | 674 (34) | 696 (56) |

| 1a | 737 (12) | 738 (14) | 738 (14) | 733 (9) | 738 (13) |

| 1g | 778 (14) | 782 (18) | 778 (14) | 771 (10) | 785 (19) |

In conclusion, two efficient synthetic routes to a new class of near-IR fluorophore 1 has been accomplished. The highly favorable emission wavelengths and quantum yields are strongly indicative of future applications in biotechnology. The ease at which key functional groups (halogen and ether) can be included on the core fluorophore indicate that future structural manipulation would be possible to allow adaption for specific use as in vitro and non-invasive in vivo imaging agents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Dr Burgess. thanks the members of the TAMU/LBMS-Applications Laboratory directed by Dr Shane Tichy for assistance with mass spectrometry and Dr Nattamai Bhuvanesh for assistance with crystallographic data. Support for this work was provided by The National Institutes of Health (GM72041) and by The Robert A. Welch Foundation. Dr O'Shea thanks funding support from the Program for Research in Third-Level Institutions administered by the HEA, Dr. D. Rai of the CSCB Mass Spectrometry Centre and Dr. H. Mueller-Bunz of the UCD Crystallographic Centre.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Experimental procedures and characterization data for the new compounds reported. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Sun C, Yang J, Li L, Wu X, Liu Y, Liu S. J. Chromatogr., B. 2004:173, 90. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2003.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiyose K, Kojima H, Nagano T. Chem.--Asian J. 2008:506, 515. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frangioni JV. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2003:626, 34. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benson RC, Kues HA. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 1977:379, 83. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyer JH, Haag AM, Sathyamoorthi G, Soong ML, Thangaraj K, Pavlopoulos TG. Heteroat. Chem. 1993:39, 49. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, Burghart A, Derecskei-Kovacs A, Burgess K. J. Org. Chem. 2000:2900, 2906. doi: 10.1021/jo991927o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thivierge C, Bandichhor R, Burgess K. Org. Lett. 2007:2135, 2138. doi: 10.1021/ol0706197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loudet A, Burgess K. Chem. Rev. 2007:4891, 4932. doi: 10.1021/cr078381n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Umezawa K, Nakamura Y, Makino H, Citterio D, Suzuki K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008:1550, 1551. doi: 10.1021/ja077756j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ulrich G, Ziessel R, Harriman A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008:1184, 1201. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim H, Burghart A, Welch MB, Reibenspies J, Burgess K. Chem. Commun. 1999:1889, 90. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burghart A, Kim H, Welch MB, Thoresen LH, Reibenspies J, Burgess K, Bergstroem F, Johansson LBA. J. Org. Chem. 1999:7813, 7819. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Killoran J, Allen L, Gallagher JF, Gallagher WM, O'Shea DF. Chem. Commun. 2002:1862, 1863. doi: 10.1039/b204317c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorman A, Killoran J, O'Shea C, Kenna T, Gallagher WM, O'Shea DF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004:10619, 31. doi: 10.1021/ja047649e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McDonnell SO, Hall MJ, Allen LT, Byrne A, Gallagher WM, O'Shea DF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005:16360, 16361. doi: 10.1021/ja0553497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Killoran J, O'Shea DF. Chem. Commun. 2006:1503, 1505. doi: 10.1039/b513878g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall MJ, Allen LT, O'Shea DF. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006:776, 780. doi: 10.1039/b514788c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Shea D, Killoran J, Gallagher W. US Pat. 7220732, 20030324 Compounds useful as photodynamic therapeutic agents. 2003

- 19.Killoran J, McDonnell SO, Gallagher JF, O'Shea DF. New J. Chem. 2008:483, 489. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao W, Carreira EM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005:1677, 9. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loudet A, Bandichhor R, Wu L, Burgess K. Tetrahedron. 2008:3642, 3654. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.01.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.