Abstract

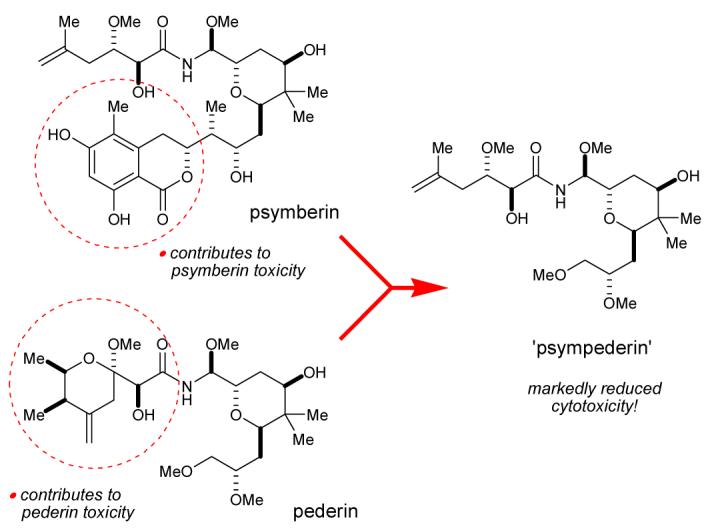

In this communication we describe an efficient synthesis of ‘psympederin’, a hybrid between the novel antitumor natural product psymberin and the blister beetle toxin pederin. Evaluation of antiproliferative activity reveals that the dihydroisocoumarin fragment is important for psymberin toxicity and the cyclic pederate fragment is important for pederin/mycalamide toxicity. Based on preliminary results described herein, we speculate that, despite their structural resemblance, psymberin and pederin/mycalamide induce toxicity through different mechanisms.

Recently, the Pettit and Crews groups independently reported the isolation of two novel natural cytotoxins from the marine sponges Ircinia ramose (irciniastatin A)1 and Psammocinia sp. (psymberin)2 which appeared to be diastereomeric. Our total synthesis3 has enabled a full stereochemical assignment, and firmly established that irciniastatin A and psymberin are in fact identical compounds with relative and absolute configuration proposed by the Crews group.2, 4 In addition to these structural considerations, our synthetic efforts were fuelled by the impressive biological activity of these natural products. Irciniastatin inhibited the growth of human tumor cell lines with values ranging from 0.1-6.2 nM (GI50, 50% growth inhibition), and exhibited antivascular activity (inhibition of human umbilical vein endothelial cells at 0.5 nM).1 Psymberin on the other hand, was evaluated in the NCI Developmental Therapeutics in Vitro Screening Program where it exhibited an unprecedented differential cytotoxicity profile - three of the melanoma (MALME-3M, SK-MEL-5, UACC-62), one breast (MDA-MB-435) and one colon cancer cell line (HCT-116) were sensitive to psymberin concentrations below 2.5 nM (LC50, 50% cell lethality), whereas most other cell lines did not respond to concentrations up to 25 μM.2 Such data, supporting a >104 differential activity for 1, are exceptional and might indicate a novel mode-of-action.

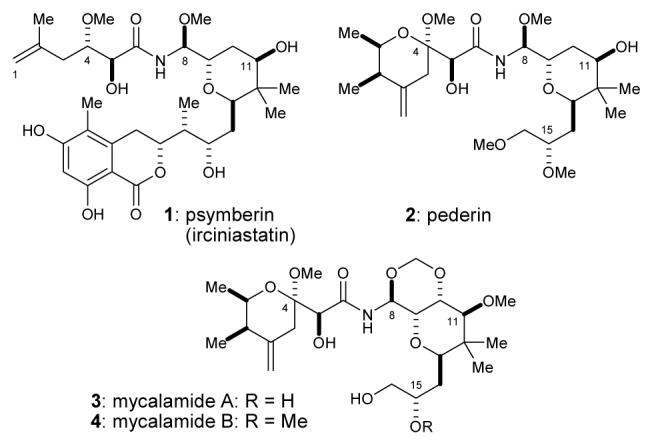

Psymberin (1) most closely resembles the pederin/mycalamide family of natural products.5 They share pederin’s 2,6-trans-substituted tetrahydropyranyl ring with axial N-acyl methoxyaminal substituent (2, Fig. 1). In mycalamides, this substructure is embedded within a conformationally locked trioxadecalin (Fig. 1, 3, 4).6, 7 Because of this partial structural resemblance to pederin-like natural products, psymberin could share the latter’s well-documented pharmacological role as potent eukaryotic protein synthesis inhibitors.8 However, the following observations indicate that psymberin could have a biological function that is at least partially distinct from the pederin/mycalamide family of protein synthesis inhibitors: (1) without exception, all ∼33 members of the pederin/mycalamide family display an identical left-half pederate side chain,5b contrasting psymberin’s lesscomplex acyclic side chain; (2) the dihydroisocoumarin bottom-half is unique to psymberin, indicating divergent biosynthetic machinery9 not found in any of the other pederin-type producing organisms; and (3) psymberin displayed unprecedented differential cytotoxicity,2 whereas pederin-like compounds display much more uniform cytotoxicity profiles.8c-e, 10 Herein, we present the first structure-function data that reveal the central importance of psymberin’s distinct dihydroisocoumarin fragment on cell proliferation.

Figure 1.

Structures of psymberin, pederin, and mycalamides.

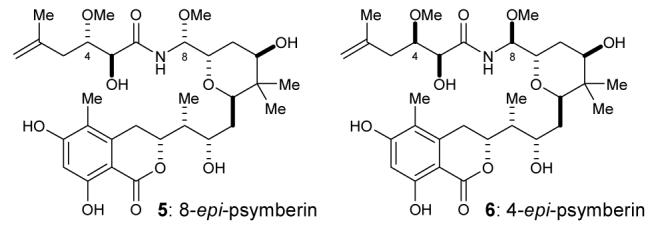

The first indication of a functional disconnect between psymberin and other members of the pederin/mycalamide family of natural products came from biological evaluation of psymberin and the epimeric variants that were obtained during our synthetic campaign to fully elucidate its stereostructure.3 Psymberin (1) and the corresponding C8- and C4-epimers 5 and 6 (Figure 2) were evaluated against a selection of human tumor cell lines. As shown in Table 1, synthetic psymberin exhibited very potent antiproliferative activity against a selection of human tumor cell lines (KM12, PC3, SK-MEL-5, T98G) with IC50 values in the single digit to sub-nanomolar range (0.45 – 2.29 nM), about 2-fold more active than mycalamide A (0.95 – 3.79 nM).11 Albeit less active, the 8-epi- and 4-epi-psymberin variants 5 and 6 were still able to prevent the proliferation of these cancer lines in the sub-micromolar range (37 – 763 nM). Similar structural changes (methoxyaminal epimer) in the pederin/mycalamide series resulted in >3 orders of magnitude reduction in cytotoxic activity.5a, 8e

Figure 2.

Two epimeric psymberins.

Table 1.

Cytotoxicities of psymberin, mycalamide A, and analogs against various human tumor cell lines.a

| cmpd | IC50[nm] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KM12 | PC3 | SK-MEL-5 | T98G | |

| 1 | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 0.98 ± 0.12 | 2.29 ± 0.13 | 1.37 ± 0.06 |

| 3 | 0.95 ± 0.02 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 3.79 ± 0.04 | 2.87 ± 0.07 |

| 5 | 37.1 ± 5.5 | 200.2 ± 27.6 | 352.0 ± 12.1 | 85.8 ± 48.4 |

| 6 | 126.08 ± 8.6 | 346.5 ± 102.8 | 762.8 ± 70.0 | 186.7 ± 51.3 |

| 18 | 710.9 ± 35.8 | 821.8 ± 89.1 | >1,000 | >1,000 |

| 19 | >1,000 | 255.5 ± 11.4 | >1,000 | >1,000 |

The Promega CellTiter GloTM assay was utilized to measure cell viability after cells were exposed to compounds for 48 h. IC50 values represent the mean of triplicate experiments ± standard error of the mean. KM12: colon tumor; PC3: prostate tumor; SK-MEL-5: melanoma; T98G: glioblastoma.

In order to fully assess the importance of psymberin’s unique dihydroisocoumarin moiety, we designed a truncated psymberin analog 18 (Scheme 1) that lacks this fragment, which is in essence also an analog of pederin with the acyclic “psymberate” (C1-C6) side chain substituting the cyclic “pederate” fragment reminiscent of the pederin/mycalamide natural products.

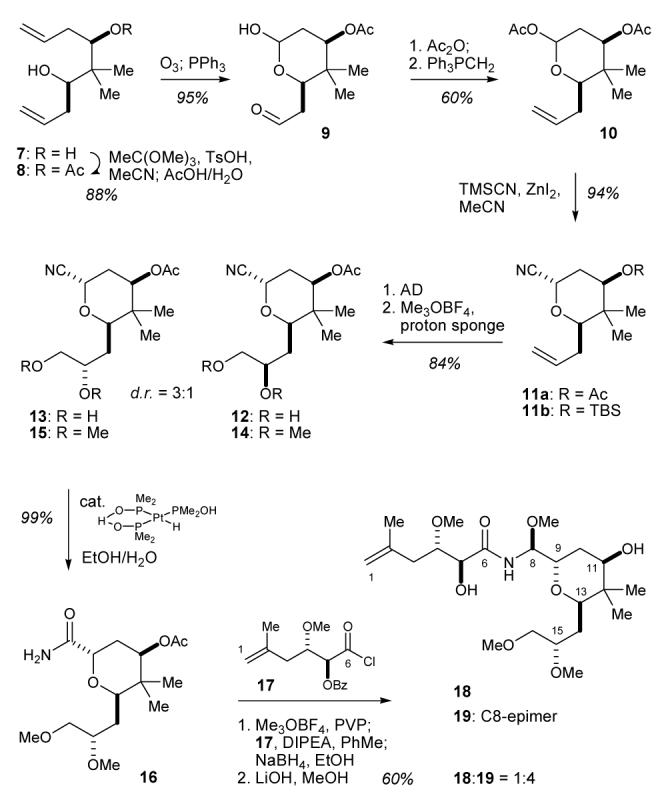

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of psymberin-pederin hybrids 18 and 19.a aDetailed experimental procedures and characterization data are provided in the supporting information.

For the synthesis of psymberin-pederin hybrid 18, we required access to acetylpedamide 16, followed by coupling with the C1-C6 “psymberate” side chain. Many synthetic approaches towards pederin have been reported,5a, 7a-c but we decided to exploit chemistry developed during our psymberin total synthesis campaign for the synthesis of acetylpedamide 16.3 As shown in Scheme 1, we started with the C2-symmetrical diol 73 - a material that was efficiently monoacetylated via acid catalyzed cyclic orthoacetate formation followed by hydrolysis mediated by the addition of aqueous acetic acid (88% yield). Ozonolysis of monoacetate 8 followed by in situ reduction with triphenylphosphine yielded cleanly lactol 9 in 95% yield. Locking the lactol as the corresponding acetate allowed for the selective methylenation of the aldehyde, providing terminal olefin 10 in 60% yield over the two steps. Introduction of the axial nitrile (→ 11a) was accomplished by ZnI2 mediated acetate displacement with trimethylsilyl cyanide in 94% yield.

After some experimentation, we found that hydroxyquinine 9-phenanthtryl ether (HQP ether)12 was the optimal ligand for the Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation (AD) of 11a,13 providing a ∼3:1 mixture (13:12) favoring the desired C15-S configured diol 13 in 92% yield.14, 15 Kocienski and coworkers had previously screened various ligands for the asymmetric dihydroxylation of the closely related substrate 11b and found HQP ether also to be optimal, although selectivity for the desired diastereomer was lower (1.5:1) with this substrate.7a The epimeric mixture of α-diols 12 and 13 was methylated to yield the separable methyl ethers 14 and 15 in 91% yield.16 Nitrile hydrolysis of the major methyl ether 15 using the Ghaffar-Parkins catalyst17 provided acetylpedamide 16 in quantitative yield.18

The final introduction of the C1-C6 “psymberate” side chain was accomplished via a protocol consisting of our modified conditions for the formation of the imidate derivative of 16, acylation with acid chloride 17, in situ reduction with ethanolic NaBH4, and final saponification of the protecting groups with LiOH in MeOH.3 A 1:4 mixture of separable (silicagel, CH2Cl2/MeOH, 50:1 to 20:1) epimeric psymberin-pederin chimeras 18 and 19 was obtained in 60% yield from acetylpedamide 16. This result is in sharp contrast with the corresponding psymberin result where the natural methoxyaminal epimer dominated (3:1),3 and indicates that diastereoselectivity associated with the N-acylimidate reduction is highly dependent on the presence or absence of the dihydroisocoumarin fragment.19

The natural C8-(S) configuration of 18 was assigned based upon a detailed analysis of 1H - 1H coupling constants, 1D-, and 2D-NOE interactions - two possible conformations consistent with all the available data are shown in Figure 3.20 The tetrahydropyranyl ring adopts a chair conformation with the C1-C8 side chain occupying the axial position, similar to psymberin and pederin. The methoxyaminal methine proton (H8) gave strong NOESY cross-peaks with the two axial tetrahydropyranyl protons H11 and H13 (see Scheme 1 for atom numbering). An anti-periplanar arrangement between H8/H9 and H8/NH was revealed by coupling constants (9.6 and 9.6 Hz) and further corroborated by a strong NH/H9 NOESY correlation. Finally, NOESY correlations between H5 and 15-OMe and 16-OMe, also observed as 1D enhancements upon irradiation of H5, unambiguously confirmed the assigned C8-configuration in 18. No such correlations or enhancements were observed for 19.21

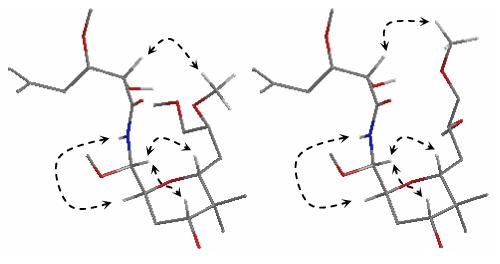

Figure 3.

Model of two proposed conformations of 18 consistent with NOE interactions (selected correlations indicated by dashed arrows) and 1H-1H coupling constants.20

Analysis of the antiproliferative activity of psymberinpederin hybrids 18 and 19 was particularly informative (Table 1). The dihydroisocoumarin-truncated psymberin analog 18 with natural C8-configuration displayed dramatically reduced cytotoxicity (∼1,000-fold) compared to psymberin (1). Furthermore, the unnaturally configured C8-epimer 19 was devoid of cytotoxic activity against three out of four tested human cancer cell lines (at 1 μM) whereas the corresponding dihydroisocoumarincontaining psymberin epimer 5 was active at concentrations between 37 and 352 nM.22 These results strongly support the notion that the dihydroisocoumarin fragment is vitally important for psymberin cytotoxicity.

Considering hybrid 18 as a pederin/mycalamide analog reveals the vital importance of the cyclic pederate side chain for pederin/mycalamide cytotoxicity. Indeed, compound 18 also displayed markedly reduced antiproliferative activity (>300-fold) compared to mycalamide A (3, Table 1). Detailed structure - activity relationships in the pederin/mycalamide series have revealed the importance of a free C5-alcohol with (S)-configuration, a free NH, a correctly configured C8-(S) alkoxyaminal, and the cyclic C4-acetal for potent cytotoxic activity (P388 and/or HeLa cell line).5a Analog 18 retains these features save for the cyclic C4-acetal. We therefore conclude that the C4-acetal functionality significantly contributes to pederin/mycalamide cytotoxicity although is not required for psymberin cytotoxicity. Interestingly, the acid lability and vesicant (blistering) effects of pederin/mycalamide has been attributed to the reactive homoallylic acetal functionality.5a Unfortunately, previously reported studies do not illuminate on the structural determinants for specific versus non-specific toxicity, and correlation with protein synthesis inhibition.

In conclusion, we have initiated the first structure-function analysis of the novel antitumor natural product psymberin. Although psymberin is structurally partially related to the pederin/mycalamide family of antitumor compounds, we demonstrated that psymberin’s mode of cytotoxicity is distinct to that induced by the pederin/mycalamide natural products. We synthesized a synthetic psymberin-pederin chimera 18 - a compound that is at the same time a psymberin analog lacking its characteristic dihydroisocoumarin fragment, and a pederin analog with an acyclic “psymberate” (C1-C6) side chain substituting for the “pederate” cyclic acetal fragment. We will continue these structure-function studies, including evaluation for protein synthesis inhibition, to further illuminate the mode-of-action of psymberin as well as mycalamide.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the National Institutes of Health (CA-90349 and CA-95471), the Robert A. Welch Foundation and Merck Research Laboratories for financial support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures, characterization data, and copies of NMR spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).Pettit GR, Xu JP, Chapuis JC, Pettit RK, Tackett LP, Doubek DL, Hooper JNA, Schmidt JM. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:1149. doi: 10.1021/jm030207d. A C11-oxo analog irciniastatin B was also isolated.

- (2).Cichewicz RH, Valeriote FA, Crews P. Org. Lett. 2004;6:1951. doi: 10.1021/ol049503q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Jiang X, García-Fortanet J, De Brabander JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:11254. doi: 10.1021/ja0537068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4) a).For examples of fragment syntheses, see: Rech JC, Floreancig PE. Org. Lett. 2005;7:5175. doi: 10.1021/ol0520267.;Green ME, Rech JC, Floreancig PE. Org. Lett. 2005;7:4117. doi: 10.1021/ol051396s.;Kiren S, Williams LJ. Org. Lett. 2005;7:2905. doi: 10.1021/ol0508375.

- (5) (a).For a review, see: Narquizian R, Kocienski PJ. The Pederin Family of Antitumor Agents: Structures, Synthesis and Biological Activity. In: Mulzer J, Bohlmann R, editors. The Role of Natural products in Drug Discovery. Springer; New York: 2000. pp. 25–56.;For a complete listing of structures of pederin related natural products including references, see the Supporting Information of ref 2.

- (6) a).Mycalamides A-D: Perry NB, Blunt JW, Munro MHG, Thompson AM. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:223.;Simpson JS, Garson MJ, Blunt JW, Munro MHG, Hooper JNA. J. Nat. Prod. 2000;63:704. doi: 10.1021/np990431z.;West LM, Northcote PT, Hood KA, Miller JH, Page MJ. J. Nat. Prod. 2000;63:707. doi: 10.1021/np9904511.

- (7) a).For selected total syntheses of mycalamides and pederin, see ref 5a, and: Kocienski PJ, Narquizian R, Raubo P, Smith C, Farrugia LJ, Muir K, Boyle FT. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 2000:2357.;Kocienski P, Jarowicki K, Marczak S. Synthesis. 1991:1191.;Takemura T, Nishii Y, Takahashi S, Kobayashi J, Nakata T. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:6359.;Roush WR, Pfeifer LA. Org. Lett. 2000;2:859. doi: 10.1021/ol005629l.;Trost BM, Yang H, Probst GD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:48. doi: 10.1021/ja038787r.;Sohn J-H, Waizumi N, Zhong HM, Rawal VH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:7290. doi: 10.1021/ja050728l.;Kagawa N, Ihara M, Toyota M. Org. Lett. 2006;8:875. doi: 10.1021/ol052943c.

- (8) (a).Jacobs-Lorena M, Brega A, Baglioni C. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1971;240:263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jiménez A, Carrasco L, Vázquez D. Biochem. 1977;16:4727. doi: 10.1021/bi00640a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Brega A, Falaschi A, De Carli L, Pavan M. J. Cell Biol. 1968;36:485. doi: 10.1083/jcb.36.3.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Burres NS, Clement JJ. Canc. Res. 1989;49:2935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Richter A, Kocienski P, Raubo P, Davies DE. Anti-Canc. Drug Des. 1997;12:217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Piel J, Butzke D, Fusetani N, Hui D, Platzer M, Wen G, Matsunaga S. J. Nat. Prod. 2005;68:472. doi: 10.1021/np049612d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Soldati M, Fioretti A, Ghione M. Experientia. 1966;22:176. doi: 10.1007/BF01897720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).We thank Prof. Northcote for providing natural mycalamide A.

- (12).Sharpless KB, Amberg W, Beller M, Chen H, Hartung J, Kawanami Y, Lübben D, Manoury E, Ogino Y, Shibata T, Ukita T. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:4585. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Kolb HC, VanNieuwenhze MS, Jian D, Nagashima H. Chem. Rev. 1994;94:2483. [Google Scholar]

- (14).The ratio was determined by 1H NMR.

- (15).Asymmetric dihydroxylation with (DHQ)2PYR or (DHQ)2PHAL was non-selective (1:1 ratio). Dihydroxylation using the UpJohn Process (cat. OsO4, N-methylmorpholine) revealed an intrinsic facial bias slightly favoring the undesired diastereomer 12 (1:1.4).

- (16).The stereochemistry was determined by chemical correlation of acetate 15 to the corresponding known tert-butyldimethylsilyl ether,7a see the Supporting Information for details.

- (17).Ghaffar T, Parkins AW. J. Mol. Cat. A. 2000;160:249. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Our synthesis of acetylpedamide 16, accomplished in 13 steps from isobutyraldehyde, compares favorable to Nakata’s7c and Kocienski’s7a 15 step syntheses of benzoylpedamide (from S-malic acid) and tert-butyldimethylsilylpedamide (from ethyl isobutyrate), respectively.

- (19).A similar coupling between benzoylpedamide and the pederin “pederate” fragment in Nakata’s pederin total synthesis also yielded a 1:3 mixture of pederin and epi-pederin (38% yield), see ref. 7c.

- (20).There is conformational flexibility in the acyclic C1-C6 and C14-C16 fragments. The conformations in Fig. 3 are meant to illustrate the proximity of these two fragments as observed by NOE interactions between H5 and C15/C16-OMe protons. For a complete listing of chemical shifts, coupling constants, and NOE correlations, and copies of corresponding spectra, see the Supporting Information.

- (21).The 1H chemical shifts and coupling constants in the C1-C13 and the C6-C16 portion of 18 are very similar to the corresponding ones in psymberin2, 3 and pederin7b respectively. For the C8-epimer 19, dissimilarities were observed mainly for the NH, H8, and H9 protons.

- (22).Interestingly, analog 19 is equipotent to C8-epi-psymberin 5 and about three-fold more potent than 18 against the PC3 pancreatic tumor cell line.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.