Abstract

The pathogenesis of Legionella pneumophila results from growth of the bacterium within lung macrophages after aerosols are inhaled from contaminated water sources. Interest in this microorganism stems from its ability to manipulate host cell vesicular trafficking pathways and to establish a membrane-bound replication vacuole, making it a model for intravacuolar pathogens. Establishment of the replication compartment requires a specialized translocation system that transports a large cadre of protein substrates across the vacuolar membrane. These substrates regulate vesicle traffic and survival pathways in the host cell. This review focuses on the strategies that L. pneumophila uses to establish intracellular growth and evaluates why the microorganism has accumulated an unprecedented number of translocated substrates targeted at host cells.

Many bacterial and eukaryotic parasites trick host cells into providing comfortable living arrangements for their descendents. Some of these microorganisms have similar requirements to viruses, as they cannot grow in extracellular or environmental niches, and must instead establish an intracellular replication cycle. Other intracellular microorganisms can replicate either inside or outside host cells. For these microorganisms, the intracellular lifestyle allows them to gain a competitive advantage relative to other microorganisms, or to facilitate colonization of a host. Life inside cells could either enable evasion of killing mechanisms that are wielded by predatory cells in the environment, such as amoebae, or provide a niche to evade host humoral and cellular immune responses.

Following uptake of microorganisms into a host-cell membrane bound compartment (called a vacuole, throughout this review), intracellular growth involves replication either within this vacuole or in the host cell cytoplasm, after destruction of this compartment. For microorganisms that replicate in a vacuole, three important problems must be tackled. First, membrane-bound compartments newly formed from the host cell surface normally enter the antimicrobial lysosomal network, which is an inhospitable environment, and this must be confronted. Second, the microorganism must acquire sustenance through the vacuolar membrane. Finally, microorganisms have to deal with space limitations after they have begun to divide in this compartment. Intravacuolar pathogens, such as Legionella pneumophila, overcome these problems by establishing an intimate association with a particular organelle in the host cell secretory system and hijacking membrane traffic from this site to the pathogen-containing vacuole (PCV). The resulting PCV is camouflaged and provided with a ready supply of new membrane to satisfy the needs of a growing population.

In this review, we will describe the membrane traffic that leads to formation of the L. pneumophila PCV and replication of the microorganism within host cells. Important bacterial and host cell proteins that are necessary for intracellular replication will be analyzed, as well as confounding results indicating that functional redundancy exists among the proteins associated with formation of the PCV. A model will be presented that will attempt to explain the evolutionary basis for this redundancy. Finally, we will discuss events that interfere with replication of L. pneumophila in host cells, and strategies that the microorganism uses to overcome these blocks on replication.

Legionella pneumophila — intravacuolar pathogen

Legionella pneumophila, the causative agent of Legionnaire's pneumonia, is an intravacuolar pathogen of environmental protozoa 1 . Pneumonic disease is initiated in humans after they inhale contaminated water supplies found in poorly designed air conditioning units or sludge-filled plumbing 2, and infection in humans possibly results from amoebae laden with bacteria3. The primary site of replication of this Gram-negative bacterium is the alveolar macrophage, where it grows in a membrane-bound compartment that is morphologically indistinguishable from that found during growth within amoebae 4,5.

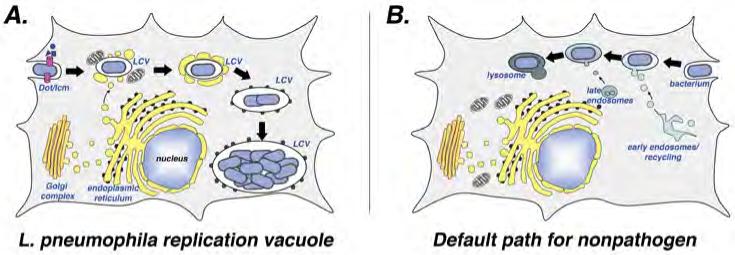

The intravacuolar lifestyle of L. pneumophila 6-8 is summarized in Fig. 1. The bacteria are found in a vacuole that resists fusion with lysosomes as demonstrated by a number of different assays 6. In support of the idea that trafficking of the Legionella-containing vacuole (LCV) is distinct from that of non-pathogens, the LCV resists acidification compared to compartments that contain Escherichia coli, indicating that maturation of the LCV into a phagolysosome is impeded8. Additionally, a series of alternative docking events appears to take place, including recruitment of mitochondria followed by association of ribosome-studded membranes (later shown to be endoplasmic recticulum (ER)) with the vacuolar membrane 7,9,10. When either intact cells or isolated LCVs are analyzed, ER associated proteins are found localized near the vacuole shortly after uptake of L. pneumophila 11,12. These ER-derived proteins include Sec22b, a member of the SNARE family of membrane fusion proteins, and the small GTPase Rab1, a regulator of traffic from the ER to the Golgi 11,12. Although the sequestration of ER-derived material might be slower in amoebae than in macrophages 13, it is clear that the LCV assumes ER character before rough ER is found to surround the compartment 7 (Figs 1, 2).

Figure 1. L. pneumophila modulates trafficking of its vacuole to establish a replicative niche.

(A) Formation of the replication vacuole. After uptake into target amoebae or macrophages, the “Legionella containing vacuole” (LCV) evades transport to the lysosomal network and is sequestered in a compartment very different from that observed for nonpathogens 6,7. Within minutes of uptake, vesicles derived from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER; yellow compartments) and mitochondria appear in close proximity to the LCV surface. The identity of the ER-derived vesicles is based on the presence of proteins known to be associated with the early secretory apparatus. The vesicles about the LCV appeared docked and extend out about the surface, and eventually the membranes surrounding the bacterium closely resemble rough ER in appearance, with ribosomes studding them. Within this ER-like compartment, the bacterium replicates to high numbers and eventually lyses the host cell. (B) Default pathway of trafficking nonpathogen. After bacterial uptake, the membrane-bound compartment acquires the character of early endosomes and late endosomes before entering into the lysosomal network.

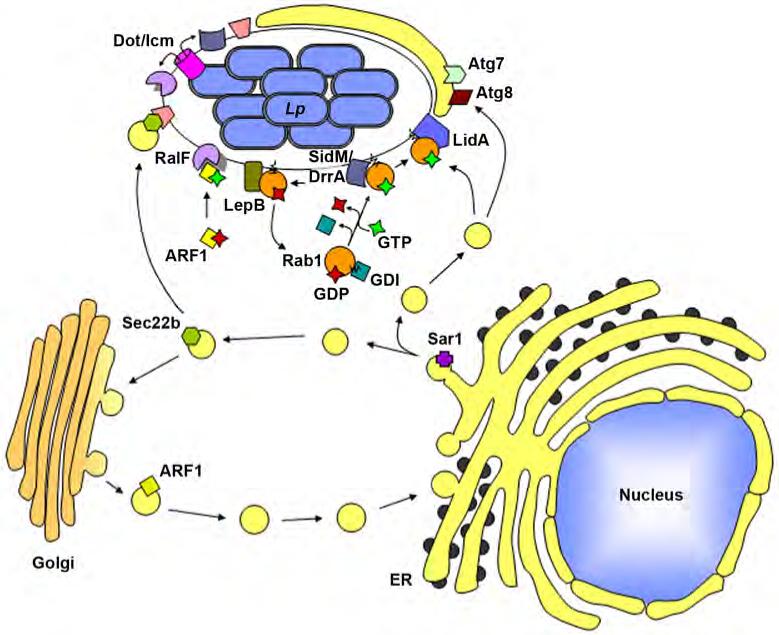

Figure 2.

L. pneumophila proteins secreted via the Dot/Icm translocation system associate with the LCV and recruit host proteins involved in vesicle trafficking through the early secretory pathway. For the sole purpose of simplifying the components displayed in the figure, the Dot/Icm apparatus is depicted as a tube extending from the bacterial cytoplasm into the host cytosol, but this there is no mechanistic support of this simplistic view. Sec22b, involved in docking of ER-derived vesicles at the Golgi, is recruited to the LCV, although the mechanism of recruitment is unclear. Rab1, another vesicle docking and fusion protein is recruited to the LCV by the L. pneumophila protein SidM which functions as both a Rab1 GDF (GDI dissociation factor) and a Rab1 GEF (guanine nucleotide exchange factor). LidA acts in conjunction with SidM to sequester activated Rab1 at the LCV membrane. LepB is a RabGAP, and may be involved in dissociation of Rab1 from the vacuolar membrane. Arf1, involved in vesicle budding and recycling at the Golgi, is recruited to the LCV via RalF which functions as an Arf1 GEF. Host membrane recruitment to the LCV may involve an autophagic process as both the host autophagy proteins Atg7 and Atg8 also localize about the LCV.

The association of ER material with the LCV indicates that after entry into host cells, L. pneumophila hijacks membrane material that is normally destined for fusion with downstream compartments such as the Golgi apparatus 14. In support of this model, interference with the function of Arf1, a small GTPase that controls a large number of functions in the host cell, including the assembly of COPI coats (which form and maintain the integrity of vesicles exiting from sites in the early secretory system), disrupts formation of the LCV 14. Although Arf1 is usually associated with budding of vesicles from the Golgi, the defect resulting from overproduction of dominant negative Arf1 is probably due to blocking maturation of vesicles from the ER, because there is little evidence for movement of vesicles in a retrograde direction from the Golgi to the LCV. Furthermore, dominant interfering mutants of Sar1, a small GTPase involved in formation of vesicles exiting from the ER, also disrupts formation of the replication vacuole 14 (Fig. 2).

There is evidence indicating that vesicles that exit the ER fuse with the LCV and deposit their luminal contents into this compartment. Fusion between vesicles and membranous compartments in eukaryotic cells requires the presence of SNARE proteins on both membranes. The association with the LCV by the Sec22b SNARE protein, which is normally found on donor vesicles derived from the ER, indicates that at least some of the host cell fusion machinery is available to allow docking and fusion of these vesicles with the LCV. The fact that a fragment of membrin, a SNARE protein found on acceptor compartments that normally acts as a partner with Sec22b, interferes with replication vacuole formation is consistent with fusion taking place with ER-derived vesicles 12. Furthermore, several hours after uptake of the bacterium into macrophages, soluble ER-derived proteins such as glucose-6-phosphatase and protein disulphide isomerase can be detected within the LCV by electron microscopy, which indicate that the soluble contents of the ER are delivered to the lumen of the LCV 15.

Autophagy and intracellular replication

Although most studies find ER associated with the LCV throughout intracellular replication, there are other membrane trafficking events that may modulate L. pneumophila intracellular growth. One study found that the separation between the LCV and the endocytic network breaks down in mouse macrophages; replicating L. pneumophila were found in compartments that contain the late endosomal protein LAMP-1 16. By contrast, another study argued that LAMP-1 compartments are unlikely to exist during replication of L. pneumophila in other cell types17. In addition, in a cultured cell line, L. pneumophila seems to be released into the host cell cytoplasm where the bacteria might undergo a few rounds of replication prior to host cell lysis 18.

Another possibility that has been raised regarding the biogenesis of the LCV is that the membranous material surrounding the LCV is derived from autophagy, which is initiated to clear L. pneumophila from the host cell 19. During autophagy, cytoplasmic material is encapsulated by membranes that resemble the ER and packaged for eventual delivery to the lysosome where the cargo is degraded20 . The association of the LCV with markers of autophagy 21, such as Atg7 and Atg8, is consistent with the formation of a nascent compartment that is destined to be targeted for degradation. If this is the case, then autophagy must be arrested for the bacteria to maintain intracellular replication (Fig. 2) 22. However, mutants of the amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum that are defective for the formation of autophagous compartments show normal intracellular replication of L. pneumophila 23.

The Dot/Icm machine

Efficient formation of the replication vacuole and successful intracellular growth of L. pneumophila requires most of the 27 dot/icm genes (Defect in Organelle Trafficking; Intracellular Multiplication; Table 1; see Fig. 3 for presumed locales of each component in the system)24-27. Mutations in many of these genes cause defective recruitment of ER-derived material to the LCV and result in rapid acquisition of late endosomal markers, such as LAMP-1 9,28. Most of the predicted protein products of these genes resemble components of conjugative DNA transfer apparatuses (type IV secretion systems; T4SS) 29. Although there are multiple T4SS in each of the four sequenced L. pneumophila strains 30,31, it was shown that bacteria can transfer DNA to other bacterial cells in a dot/icm-dependent fashion, indicating that the Dot/Icm machine transfers macromolecules to target cells 27,32. Protein is probably the critical macromolecule transferred to host cells33. This was originally made clear by bioinformatic searches for proteins that show sequence similarity to eukaryotic proteins that manipulate ER-to-Golgi traffic. In this fashion, the RalF (Recruitment of Arf1 to Legionella phagosome) protein was identified. RalF, which was demonstrated to be translocated to macrophages in a Dot/Icm-dependent fashion, has a Sec7 homology domain that allows the protein to activate Arf1 34 .

Table 1.

Dot/Icm proteins

| Protein | Comment/Function |

|---|---|

| Substrate Recognition | |

| IcmS36-38,40 | Substrate recognition/presentation to translocon |

| IcmW36-38,40 | Substrate recognition/presentation to translocon |

| LvgA36 | Substrate recognition/presentation to translocon |

| Coupling ATPase | |

| DotL/IcmO42,43 | ATPase /binds directly to substrates? |

| DotM/IcmP46,47 | ATPase component |

| DotN/IcmJ46,47 | Probable ATPase component |

| Core Components | |

| DotC47 | Putative outer membrane lipoprotein |

| DotD47 | Putative lipoprotein/localized to outer membrane |

| DotF/IcmB47 | Interacts with substrates/major component of channel? |

| DotG/IcmE47 | Major component of channel |

| DotH/IcmK47 | Outer membrane channel? |

| Core Stability Determinants | |

| DotU/IcmH50,51 | Inner membrane protein |

| IcmF50,51 | Inner membrane protein |

| Cytoplasmic Components | |

| IcmQ49 | Pore forming molecule |

| IcmR37,48 | Chaperone for IcmQ |

| DotB54,116 | ATPase/Disassembly of translocon? |

| DotO/IcmB117 | Cytoplasm/inner membrane |

| Inner Membrane or Periplasmic Components of Unknown Function | |

| DotA25,118 | Large polytopic inner membrane protein |

| DotE/IcmC47 | Similar to DotV |

| DotI/IcmL117 | Inner membrane |

| DotJ/IcmM | Predicted inner membrane |

| DotK/IcmN119 | Predicted inner membrane |

| DotP/IcmD | Predicted inner membrane |

| DotV47 | Predicted inner membrane |

| IcmT120 | Inner membrane protein |

| IcmV121 | Predicted inner membrane |

| IcmX122 | Periplasmic |

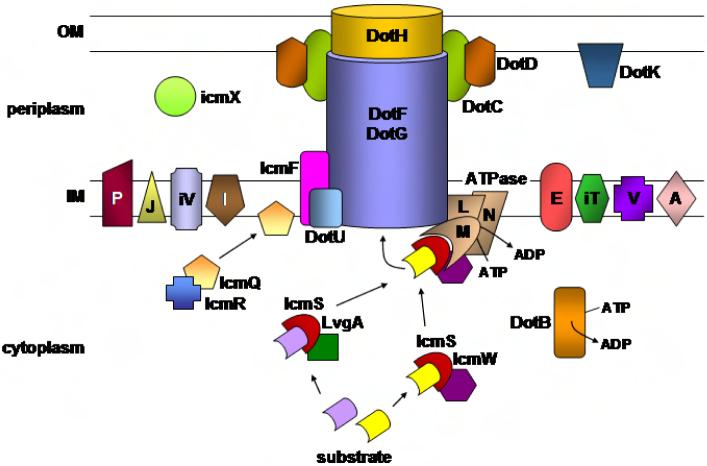

Figure 3. The Dot/Icm translocation apparatus.

Depicted are the presumed locales and topological relationships of the various Dot/Icm components in the L. pneumophila envelope based on a study of the stability of individual proteins in the presence of defined deletion mutations46. Individual letters represent Dot protein names whereas letters preceded by an “i” indicated Icm protein names. See text for further details of the individual Dot/Icm components.

Following this discovery, it became clear that the function of the Dot/Icm system was to deliver proteins across the target host cell membrane. These “translocated substrates” accumulate across the plasma membrane shortly after contact of the bacterium with the host cell35, and are found on the outer face of the LCV as well as associated vesicles 33. It took some time to identify just a single translocated protein, but the number of identified Dot/Icm substrates has since avalanched (see below).

Although detailed understanding of the functions of the Dot/Icm proteins is still poor, they can be separated into several classes, as follows (Table 1).

Translocated substrate-associated proteins

The IcmS protein in complex with either IcmW or LvgA seems to coordinate presentation of many translocated substrates to the Dot/Icm secretion system 36,37. In fact, binding to IcmS 38 or IcmW 39 has been used to identify substrates. Binding of IcmS, IcmW, and/or LvgA 37-40 to translocated substrates appears to occur within a complex that includes at least two of these three T4SS components 36,38-40. Although interactions between IcmW, IcmS, LvgA and their targets appear reminiscent of stable interactions between chaperones and substrates in type III secretion systems (TTSS), the relationship between these proteins is almost certainly more complicated. There is probably a much larger steady-state pool of translocated substrates than of Dot/Icm components, consistent with a transient interaction during the course of secretion (similar to chaperone-assisted Sec-dependent secretion in bacteria41).

The DotLMN translocation ATPase

The DotL protein shows strong sequence similarity to membrane-associated proteins that couple protein/DNA substrates to conjugative systems in preparation for transfer to target cells 42. As there is evidence in several conjugative transfer systems for direct binding of the ATPases to translocated substrates 43,44, it is believed that proteins translocated by Dot/Icm bind to DotL, possibly using other Dot/Icm components as linkers. The crystal structure of one such coupling ATPase demonstrates that the protein forms a hexameric ring, providing a channel into which substrates could enter during transfer 45. That DotL directly binds to DotM and DotN is suggested by the fact that the absence of one of these membrane proteins results in degradation of the others. Furthermore, dotL−, dotM− and dotN− mutants all have similar phenotypes, with mutations in each resulting in hyper-NaCl sensitivity of the bacteria or lethality, depending on the strain harboring the mutations 46,47. These proteins are also destabilized by the absence of IcmS or IcmW 47. This suggests that a recognition site on the DotL/DotM/DotN membrane complex binds IcmW and/or IcmS proteins, which in turn are bearing substrates.

The bacterial envelope-associated core complex

Much of the information leading to the concept of the core complex is based on the demonstration that stabilizing interactions occur between a subgroup of Dot/Icm proteins and the demonstration that mutations in one of these components results in altered compartmentalization of the other proteins. These five Dot/Icm components (DotC, D, F, G and H) interact to span the inner and outer bacterial membranes 47. The presumed critical outer membrane partner is DotH, which fails to localize in the outer membrane in the absence of DotG or the outer membrane lipoproteins DotC and DotD 47. It is possible that DotH is the outer membrane channel through which substrates pass as they transit from the DotF/DotG inner membrane proteins via the DotL/DotM ATPase.

Essential cytoplasmic components

These are necessary for the proper function of the Dot/Icm translocator. A rather mysterious component of the translocation system is the cytoplasmic IcmQ/IcmR complex 37,48. The absence of either protein prevents translocation of substrates and formation of the replication vacuole, but there is no evidence for direct interaction of either protein with any known membrane-associated protein. Although the complex might perform chaperone functions similar to those hypothesized for IcmW/IcmS, the phenotypes of mutations in the IcmQ/IcmR complex are not similar to those affecting IcmS/IcmW. As is true of mutants lacking membrane components, icmQ− or icmR− mutants cannot promote high multiplicity cytotoxicity in macrophages, an activity that is taken as an indicator for a functioning protein channel into target cells 37,48. Consistent with the idea of channel formation, in the absence of IcmR, the IcmQ protein can insert into membranes 49. However, as yet there is no evidence for Dot/Icm-dependent insertion of IcmQ into target membranes either after association of L. pneumophila with host cells or at any other stage of the lifecycle 49.

Inner membrane accessory factors IcmF and DotU/IcmH

These proteins regulate the turnover of core components. Deletion mutations in icmF or dotU/IcmH result in partial defects in intracellular growth and effector translocation, indicating that the products of these genes might support translocation 50,51. In the absence of IcmF or DotU, the steady state levels of DotG and DotH are reduced. Interestingly, IcmF and DotU are the most widely distributed of the Dot/Icm proteins, with orthologs in many bacterial species that interact with host cells and lack recognizable type IV secretion systems 52. It has been argued that these orthologs are components of the recently discovered type VI secretion system 53. By analogy with the Dot/Icm system, the orthologs might not be directly involved in protein translocation, but instead modulate the stability or function of the type VI system.

Components of unknown function

The remaining proteins are by-and-large essential for formation of the replication vacuole and intracellular growth, but their relationships with the other components are unknown (Table 1). The only hint regarding these proteins is based on the sequence similarity of DotB to PilT ATPases 54. This family is associated with pili-promoted twitching motility, and can couple ATP hydrolysis in the cytoplasm to depolymerization of pili on the outer surface of the outer membrane. This protein might be involved in energy transfer across the bacterial envelope, or in promoting disassembly of the complex at critical points in the translocation process.

Dot/Icm substrates

According to the “Molecular Koch's Postulate,” originally formulated by Falkow 55, if a mutant can be demonstrated to be defective for a process critical in pathogenesis, then the protein missing in the mutant can be called a virulence factor. The inability to demonstrate a defect in a virulence-associated process has sometimes been used as an argument against the importance of a protein in disease. As emphasized by the original formulator of this model 56, this point of view is much too simplistic, as many proteins play roles in pathogenesis that are too complex to be uncovered in the assays commonly used by workers in the field. The analysis of the Dot/Icm substrates supports the complex view of the pathogen, and highlights the difficulty in trying to formulate simple definitions of virulence factors. Although most of the dot/icm genes result in complete loss of replication vacuole formation and intracellular growth, the substrates of Dot/Icm often fail the simple test for significance. The best-case scenario for some of the substrates is that their absence results in partial defects in intracellular growth or replication vacuole morphology 38,57,58. As a result, screens for mutants defective in intracellular growth have only uncovered genes encoding a few substrates, with the most profound mutant being in sdhA (SidH paralog A). Deletion of this gene, blocks intracellular growth without grossly affecting replication vacuole formation (discussed below) 59. Therefore, the identification of substrates requires that strategies other than screening for defective intracellular growth must be used.

As a result, several complementary strategies have been used to identify the Dot/Icm substrates (see Box: “Searching for Translocated Substrates” for more details). The four major approaches that have been used involve: 1) bioinformatics analysis to identify proteins likely to have activities only within eukaryotic cells33,60,31,61,62; 2) the use of gene fusions to detect protein sequences that promote translocation of an assayable protein fragment27,32,124; 3) the identification of L. pneumophila proteins that disrupt cellular processes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae57,63; and 4) the identification of regulatory networks that control translocated substrates64 (Table 2; Supplementary Table 1). Thus far, 85 proteins have been identified that contain a signal recognized by the Dot/Icm system (Supplemental Table 1). Representatives of these substrates are shown in Table 2, chosen so that the substrates represent examples of most of the structural elements predicted by sequence analysis. In addition to the described substrates in these tables, our laboratory has identified an addition 65 proteins having sequences that can provide translocation signals (data not shown). The number of substrates is likely to be much larger than this 140 total, as none of the strategies used to identify substrates has been performed in a saturating fashion. In addition, the complete sequence determination of several strains indicates that there may be great variation between different clinical isolates in the number of translocated substrates 30,31.

Table 2.

Examples of Dot/Icm translocated substratesa

| A: Substrates based on similarity to eukaryotic proteins | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Gene | Domain/Function | Evidence for Translocationb |

| RalF33 | lpg1950 | sec7 homology domain, ARF1 GEF/ARF1 recruitment | CA, IF |

| LepA62 | lpg2793 | homology to EEA1, USO1 SNAREs, coiled-coil domain/bacterial egress | CA, BLA |

| LepB62,77 | lpg2490 | homology to EEA1, USO1 SNAREs, coiled-coil domain, Rab1 GAP/vesicle trafficking, bacterial egress | CA |

| LegA8/AnkN/AnkX61,123,124 | lpg0695 | ankyrin repeat | CA, BLA |

| LegAU13/Ceg27/AnkB61,64,123 | lpg2144 | F-box, ankyrin repeat | BLA |

| LegC8/Lgt261 | lpg2862 | glucosyltransferase, coiled-coil domain | BLA |

| LegL361 | lpg1660 | leucine-rich repeat | CA, BLA |

| LegLC861 | lpg1890 | leucine-rich repeat, coiled-coil domain | CA, BLA |

| LegG261 | lpg0276 | RasGEF | CA, BLA |

| LegP31,61 | lpg2999 | astacin protease | BLA |

| LegT61 | lpg1328 | thaumatin domain | BLA |

| LegU161 | lpg0171 | F-box | BLA |

| B: Substrates identified by directly assaying for Dot/Icm-dependent translocation | |||

| Protein | Gene | Domain/Function | Evidence for Translocationb |

| SidF39,72,89 | lpg2584 | Bcl2-rambo and BNIP3 binding domain/anti-apoptosis | IT, IF, CA |

| SdhA59 | lpg0376 | coiled-coil domain/anti-apoptosis | SE |

| C: Substrates identified in yeast ectopic overexpression studies | |||

| Protein | Gene | Domain/Function | Evidence for Translocationb |

| VipA63 | lpg0390 | Formin homology domain/vesicle trafficking | CA |

| YlfA/LegC757,61 | lpg2298 | coiled-coil domain/vesicle trafficking | CA, BLA |

| D: Substrates identified based on regulatory networks | |||

| Protein | Gene | Domain/Function | Evidence for Translocationb |

| Ceg1064 | lpg0284 | hypothetical protein | CA |

| E: Substrate identified by a putative Dot/Icm translocation signal | |||

| Protein | Gene | Domain/Function | Evidence for Translocationb |

| Lpg004566 | lpg0045 | hypothetical protein | CA |

| F: Substrates identified by alternative mechanisms | |||

| Protein | Gene | Domain/Function | Evidence for Translocationb |

| SidM/DrrA75,76 | lpg2464 | Rab1 GEF, Rab1 GDI/Rab1 recruitment | CA, IF, PNS |

| LidA35,75 | lpg0940 | coiled-coil domain/Rab1 sequestering | IF, PNS |

| SidJ78 | lpg2155 | ER recruitment | SE, ST |

| WipA39 | lpg2718 | hypothetical protein | CA |

A complete list of substrates is given in Supplementary Table 1.

CA: cya-fusion assay; IF: immunofluorescence microscopy; IT: inter-bacterial transfer; PNS: protein present on phagosomes isolated from postnuclear supernatants of infected cells; SE: saponin extraction; ST: SidC-based translocation assay; BLA: fusions to β-lactamase125.

With the wealth of substrates, this should generate sufficient information to allow detection of a common motif recognized by the Dot/Icm apparatus (Table 2; Supplementary Table 1). In fact sequence patterns in known translocated substrates have allowed further bioinformatic identification of substrates. The T4SS appears to recognize a signal on the C terminus of target proteins, and analysis of the C terminus of RalF showed that a hydrophobic residue, 2 amino acids upstream of the C terminus, is crucial for translocation of RalF into mammalian cells 65. Extending the analysis of known translocated substrates further, polar and small residues seem to be common upstream of the hydrophobic residue 66. By looking for similar arrangements of sequences near the C termini of all L. pneumophila proteins, 19 more Dot/Icm substrates were identified that were not detected using other strategies66. The fact that only a subset of translocated substrates can be found using this strategy, however, underlies the difficulty of finding a single recognition signal for translocation.

Regulation of translocated substrates

Efficient intracellular replication of many strains of L. pneumophila requires that the bacteria be grown to post-exponential phase in broth culture prior to introduction onto host cells67. Consistent with this phenomenon, proteins involved in regulating post-exponential phase gene expression are required for optimal intracellular replication 68-71. Furthermore, several of the translocated substrates of Dot/Icm are most highly expressed in post-exponential phase 33,58,72,73. This indicates that common regulators might control many of the substrate-encoding genes. A consensus regulatory sequence (cTTAATatT) that seems to be recognized by PmrA, a two-component response regulator 64 is present upstream of several genes encoding Dot/Icm substrates. A significant number of these genes have reduced expression in the absence of PmrA, and a ΔpmrA strain is defective for intracellular growth, indicating that PmrA might control many proteins that interface with host cells. Another 35 targets of PmrA were identified from the presence of the consensus sequence, several of which are linked on the chromosome to dot/icm substrate-encoding genes 64. Several of these cegs (coregulated with effector genes) have eukaryotic motifs. Furthermore, seven (Supplementary Table 1) were shown to be translocated in a Dot/Icm-dependent fashion using an enzymatic assay 64. Similarly, nine translocated substrates were identified after searching for genes regulated by the CpxR transcriptional regulator 74.

Modulation of vesicle trafficking by Dot/Icm substrates

Hijacking of host cell membrane material by the replication vacuole involves the recruitment of host cell regulatory and effector proteins that promote vesicle budding, tethering and fusion throughout the early secretory system. The recruitment of Arf1, Rab1 and Sec22 11,12 makes each of these a potential target of the translocated substrates (Fig. 2). The demonstration that the translocated substrate RalF activates Arf1, and that ralF− mutants are defective for recruitment of Arf1 to the LCV, gave the first support for this idea 33. However, these mutants are still able to grow intracellularly, even though chemical inhibition of Arf family function interferes with intracellular growth 14. Therefore, although Arf1 activity is important for intracellular growth, its recruitment to the LCV is of unknown importance. Either there exist other L. pneumophila proteins that manipulate Arf family member activity, or host cell activators of Arf can regulate membrane trafficking processes that are important for intracellular growth.

The story of the recruitment of Rab1 to the LCV follows a similar scenario. Association of Rab1 with the LCV depends on the Dot/Icm translocated substrate SidM 75 (DrrA 76), which activates Rab1 by promoting nucleotide exchange. Reminiscent of the Arf1 story, dominant inhibitory variants of Rab1 interfere with LCV formation 11,12, so it might be expected that recruitment of Rab1 by SidM/DrrA would be critical for intracellular growth—but it is not. Mutants lacking SidM/DrrA grow intracellularly in all cell types tested 75,76. This lack of phenotype is particularly strange, given that L. pneumophila appears to encode many proteins that modulate Rab1 dynamics. Another translocated substrate LidA binds to Rab1 (as well as other Rab family members) 75, while a third translocated substrate, LepB is a GTPase activating protein for Rab1 (RabGAP)77. This indicates that L. pneumophila can control the complete cycle of Rab1 activation (via SidM/DrrA) and inactivation (via LepB), and use a third protein for recognition. However, bacteria lacking the proteins that manipulate Rab1 have only small defects, at best, in establishing the LCV96. In fact, there is no demonstration that an effector of known activity is a critical component of LCV formation, although mutations in a previously uncharacterized protein, SidJ, have been demonstrated to result in lowered ER recruitment35,78.

The genetic analysis of translocated substrates has been frustrating, but the biochemistry of their activities has been fascinating. By way of example, SidM/DrrA has a novel activity not observed in other GEF proteins. In eukaryotic cells, Rab GTPases are geranylgeranylated. In their inactive GDP-bound form, Rab proteins associate with RabGDI proteins, which block exposure of the lipid tail to the aqueous environment and allow the formation of a soluble pool of GTPases 79. This raises a problem for RabGEF proteins: they are blocked from activating Rabs bound to GDI. There is evidence, at least in one case, that a GDI dissociation factor (GDF) can extract Rab proteins from the soluble pools 80. Although this protein, called Pra1, might be involved in LCV formation, there is no reason that it should be necessary to extract and recruit Rab1 to the LCV. This is because SidM/DrrA has both GEF and GDF activities, as it can extract and activate geranylgeranylated Rab1 77,81. In a pure system, SidM/DrrA can remove Rab1 from its GDI bound partner and deliver activated protein to synthetic lipid vesicles, reconstructing the entire recruitment process in vitro 81. Furthermore, both the GDF and GEF activities of SidM/DrrA are necessary for recruiting Rab1 to membranes in living cells, providing the only in vivo evidence that GDF activity is needed for the delivery and activation of a Rab protein to cellular membranes 77.

Effector redundancy

Given that the Dot/Icm system is required for LCV formation, and the fact that four Dot/Icm substrates have activities that manipulate ER-to-Golgi traffic, it is likely that the translocated substrates have a role in promoting replication vacuole formation 33,75,76,81. The difficulty in demonstrating phenotypes of deletion mutations in genes for substrates may be indicative of functional redundancy, such that multiple proteins can carry out similar functions. This presents a difficult problem: there are few systematic approaches that allow redundant functions to be identified. Inspection of four sequenced L. pneumophila genomes could provide insights, as many of the translocated substrates are members of protein families 30,31,72. In some cases, substrates have as many as five paralogues; unfortunately, there is little evidence that deletion of all of the paralogues in a family reveals a new phenotype 38,57,58. The only exceptions to this rule are the lepA/lepB double mutant and removal of all three paralogues of the sdhA family. In the former case, the double mutant reveals a defect in lysis from amoebae 62, whereas in the latter, a profound defect in host cell survival caused by loss of sdhA is exacerbated by loss of the other paralogues59.

Functional redundancy might occur if substrates target different host cell trafficking pathways that can each promote LCV formation. If so, eliminating one of these processes should cause the bacterium to become dependent on the remaining pathway(s), revealing phenotypes that are not otherwise apparent. Evidence for this model was obtained using replication of L. pneumophila in Drosophila melanogaster cells 82. Interruption of individual membrane trafficking pathways, using RNA interference (RNAi) against specific components involved in vesicle budding and fusion, often results in little or no reduction in L. pneumophila intracellular growth. On the other hand, if RNAi is targeted against appropriate pairs of transcripts that encode proteins involved in different steps in membrane trafficking, then defects in intracellular growth can be demonstrated 82. Therefore, the L. pneumophila translocated substrates might target each of these pathways, raising the possibility that interfering with the function of one of these pathways might allow phenotypes of bacterial mutants to be revealed. Similar redundancy might be present in other intracellular pathogens, such as Salmonella and Shigella 83,84.

One useful comparison that could shed light on the reason for the high number of substrate-encoding genes in the genome is with the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae, which translocates proteins into host plant cells through a type III secretion system (TTSS). As in L. pneumophila, hundreds of TTSS substrates encoded by P. syringae have been identified, but this number is spread out over a large number of pathogenic isolates 85,86. Any single P. syringae isolate rarely has more than 40 known substrates 87. These strains are highly adapted to a limited spectrum of hosts, so that host specificity is at least partially determined by the strain-specific spectrum of TTSS substrates. By contrast, L. pneumophila is not a specialist in the same sense. Although L. pneumophila has adapted to grow in amoeba and other unicellular microorganisms, there is no demonstrated amoebal host preference, and many cell types can support intracellular growth of this microorganism 88. Although there might have been powerful selection for the acquisition or generation of new substrate genes to facilitate intracellular growth in multiple amoebal species, there has been less selective pressure for the loss of genes. This is presumably because a set of genes that does not facilitate optimal growth in one host allows a selective advantage when the next species is encountered.

Although this model explains the lack of host specificity and the multitude of substrates, it does not totally explain functional redundancy, as one could imagine a pathogen in which loss of proteins that are optimized for growth in one host should result in a profound intracellular growth defect in that particular host. Although there is evidence that certain proteins in L. pneumophila selectively give advantage in certain hosts (for instance SdhA, SidF and SidJ)59,78,89, for most substrates the consequences of deletions are subtle or nonexistent during the timescale of normal laboratory experiments. Translocated substrates that are optimal in one host might have partial activities in another, contributing to the appearance of redundancy. This model also predicts that because the main selection is for the microorganism to be a generalist, individual L. pneumophila strains do not need the identical spectrum of substrates, so long as the organism can grow in multiple hosts. Consistent with this possibility, the four completely sequenced strains are predicted to have many substrates that are only present in a subset of strains 30,31.

Survival of the host cell

Growth of L. pneumophila within macrophages involves a battle between life and death for the host cell. As continued intracellular replication requires a live macrophage, the bacterium needs to ensure the survival of the host cell against assault by toxic microbial products and the immune system. L. pneumophila can induce Dot/Icm-dependent death through both apoptotic 90-92 and nonapoptotic pathways92,93, whereas innate immune mechanisms can lead to premature death of infected macrophages causing termination of the replication cycle 94,95. These events are not good for intracellular replication. Macrophage death caused by L. pneumophila can most clearly be seen under conditions of high loads of bacteria, which results in induction of caspase 3 92,96, and in some cell types, caspase 1 95,97. Although it has been argued that caspase 3 might support intracellular replication 98, the consensus is that the bacterium must interfere with caspase activation in some way to support intracellular growth 59,95. In addition, high multiplicities of infection result in damage to the host cell membrane leading to cellular death 92,93, and similar types of nonapoptotic death are also apparent even at low doses of bacteria 59. For the most part, the microbial components that induce cell death have not been identified, although in macrophages isolated from mouse strains that fail to support efficient L. pneumophila growth, the bacterial flagellin protein appears to promote caspase 1-dependent cell death 97,99.

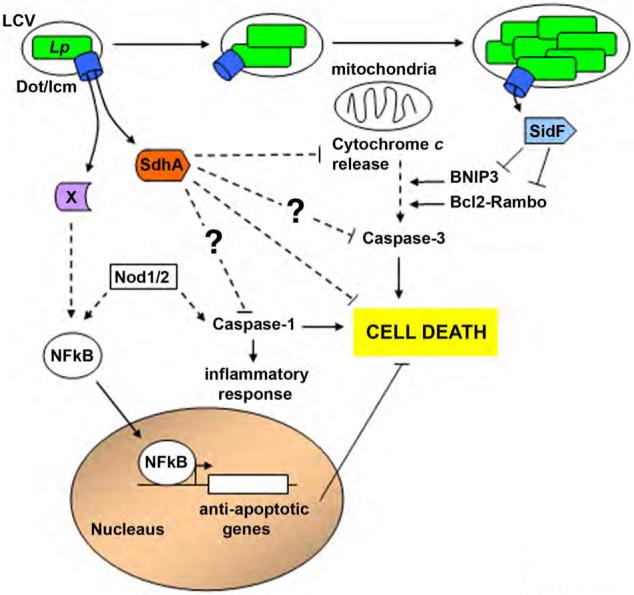

Importantly, the bacterium can interfere with host cell death, using a mechanism that requires the Dot/Icm translocator (Fig. 4) 100. The mechanisms that protect against host cell death are likely to be diverse, because many types of death pathways seem to be induced in mammalian cells in response to L. pneumophila. One strategy employed by the bacterium is to induce transcription of host cell anti-apoptotic proteins, at least some of which are positively regulated by the NFκB transcription factor 100, 101. In addition, two translocated substrates of the Dot/Icm system interfere with host cell death. SidF interferes with specific pro-apoptotic pathways induced in response to L. pneumophila 89 by binding to two members of the Bcl2 family of pro-apoptotic proteins, Bcl-rambo and BNIP3, and thereby interfering with an intrinsic death pathway that is initiated by these proteins 102,103. Interestingly, SidF appears to be necessary for protecting against host cell death only during the last few hours of intracellular replication, as ΔsidF mutants initiate replication efficiently and host cells harbouring the mutant are relatively healthy during the first several hours of encounter 89.

Figure 4. L. pneumophila manipulates host cell death and survival pathways.

After uptake into mammalian cells there is a response to L. pneumophila that threatens to terminate intracellular growth by causing host cell death. The cell death pathways have both necrotic as well as apoptotic character, and require the presence of an intact Dot/Icm translocation system. The individual L. pneumophila components or translocated substrates that cause cell death have not been identified. In addition, there are at least two translocated substrates that interfere with host cell death. SdhA is required to inhibit multiple pathways that lead to cell death after L. pneumophila contact with host cells, and its absence causes a defect in intracellular replication within macrophages. L. pneumophila also activates the host transcription factor NFκB to promote expression of anti-apoptotic genes to delay host cell death; however, the mechanism by which this occurs has not yet been determined. At later stages of infection, SidF directly inhibits an apoptotic pathway by interfering with pro-death proteins in the Rambo family. See text.

A mutation that eliminates another translocated substrate, SdhA, has profound effects on intracellular growth in bone marrow-derived macrophages from mice; ΔsdhA mutants induce cell death shortly after uptake 59. Such a strong phenotype resulting from loss of a translocated substrate is unique, and indicates that interference with cell death by SdhA is the primary strategy used to promote host cell survival. The protein is one of three paralogues expressed by the L. pneumophila Philadelphia 1 isolate, and deletion of all three genes results in a strain that cannot replicate in bone marrow-derived macrophages. Although the mechanism of SdhA-dependent protection from host cell death has not been determined, it must either target a step that is common to a variety of cell death pathways, or have multiple sites of action: both caspase-dependent and -independent pathways of cell death are inhibited by bacteria encoding SdhA 59.

One striking phenotype of strains bearing sidF and sdhA knockout mutations is that growth defects for these mutants are only observed in macrophages. For most pathogens that are selected for growth on a particular mammalian host, there would be nothing odd about this result; however, for L. pneumophila there is no explanation for the selective pressures that could have led to this specificity. According to current models, L. pneumophila is an “accidental pathogen” in which selective pressures are directed toward evolving an organism that survives and grows efficiently within amoebae104. The fact that SidF binds two pro-death family members that are not found in lower eukaryotes cannot be easily explained by this theory. Either human pathogenic L. pneumophila strains have been selected for virulence by growth in a higher eukaryote, or they encountered simple uncharacterized eukaryotes that have death cascades similar to those in multicellular organisms. Consistent with this latter model is the observation that programmed cell death cascades occur in amoebae and involve apoptotic, necrotic and autophagic pathways 105-107.

Conclusions

The intracellular lifecycle of L. pneumophila is well characterized, and most of the mutants that have profound defects in establishing a replicative niche in the host cells have probably already been identified. Four complete genome sequences of related strains have been completed, allowing comparative analysis of substrates108,30,31. Many translocated proteins have also been identified in the L. pneumophila philadelphia 1 strain. However, it is difficult to demonstrate that any of the translocated effectors are essential in replication vacuole biogenesis. Analysis of L. pneumophila pathogenesis is complicated by the fact that it is not a robust pathogen, with high doses of bacteria required to establish disease. Animals that are defective for Toll-like receptor signaling show higher susceptibility to the pathogen 109, raising hope that novel animal infection models may provide new insights into the disease process. The fact that the related organism, Legionella longbeachae causes severe disease in mice might be a partial solution, but this organism is not well characterized 110,111.

It might be possible to take a systems biology approach to probe how L. pneumophila grows within host cells. There are blocks of dissimilarity as well as the loss and acquisition of isolated genes in the four sequenced genomes, which might define regions encoding translocated substrates of Dot/Icm 30,31. Analysing the members of the regulons controlled by CpxR, PmrA and RpoS could also provide information on host-pathogen interactions 64,70,71,74,87.

This is an exciting time to be studying the biology of L. pneumophila intracellular growth. Although the problems raised are complex, solutions to these problems are likely to be satisfying and may involve integrating data generated by analyzing the contributions to the formation of the replication vacuole of hundreds of different proteins.

BOX 1: “Searching for translocated substrates”.

Translocated substrates of Dot/Icm have been identified in a variety of fashions (Table 2; Supplementary Table 1). Bioinformatics picked out almost 50 potential substrates. The proteins have sequences similar to proteins involved in processes unique to eukaryotic cells 31,61,62. These leg (Legionella eukaryotic-like) genes, include kinases, lyases and esterases 31,61. Several are predicted to be involved in ubiquitination, and one was shown to be a ubiquitin ligase 66. Furthermore, several dozen proteins with predicted coiled-coil secondary structures are encoded in the four sequenced L. pneumophila strains as are proteins with ankyrin and leucine-rich repeats 31,61,62,72,112 . A second strategy was to identify biological regulatory networks that control identified substrates and extend the analysis to identify other genes similarly regulated74.

Dot/Icm substrates have been identified by the presence of translocation signals 27,32. Such proteins (called “Sid” for Substrates of Icm/Dot) were identified using a Cre-lox site assay, in which fusions were constructed between the 3’ ends of L. pneumophila genes and the Cre site-specific recombinase gene113. Recognition of the recombinase fusions by the Dot/Icm system was detected by mixing the fusions strains with a recipient strain that had an antibiotic resistance detector readout for acquisition of the recombinase 38,58,72.

A fourth strategy used to identify translocated proteins was to screen for Legionella proteins that disrupt cellular functions when ectopically expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Table 2C) 57,63. Proteins translocated by bacteria into host cells cause misregulation of biochemical pathways in eukarotic cells, which can be detected as growth defects in yeast 114. Few, if any, proteins involved in bacterial housekeeping functions trigger such growth defects 115. Shuman and coworkers hunted specifically for proteins that could disrupt secretory function 63. Four such proteins, called Vips, were identified. Similarly, a general screen for loss of viability was performed, by introducing a random bank of L. pneumophila genes into yeast 57. This identified YlfA, which localizes to the early secretory apparatus, as well as SidE and SdcA (SidC paralog A), which were identified using the Cre-Lox assay 72.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1: Dot/Icm translocated substrates

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Matthias Machner, Vicki Auerbuch Stone and Elizabeth Creasey for review of the manuscript. MH was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the NIAID and RRI is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rowbotham TJ. Preliminary report on the pathogenicity of Legionella pneumophila for freshwater and soil amoebae. J. Clin. Pathol. 1980;33:1179–83. doi: 10.1136/jcp.33.12.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muder RR, Yu VL, Woo AH. Mode of transmission of Legionella pneumophila. A critical review. Arch. Intern. Med. 1986;146:1607–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brieland J, et al. Coinoculation with Hartmannella vermiformis enhances replicative Legionella pneumophila lung infection in a murine model of Legionnaires' disease. Infect. Immun. 1996;64:2449–56. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2449-2456.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Segal G, Shuman HA. Legionella pneumophila utilizes the same genes to multiply within Acanthamoeba castellanii and human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:2117–24. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2117-2124.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abu Kwaik Y. The phagosome containing Legionella pneumophila within the protozoan Hartmannella vermiformis is surrounded by the rough endoplasmic reticulum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996;62:2022–8. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.6.2022-2028.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horwitz MA. The Legionnaires' disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) inhibits phagosome-lysosome fusion in human monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1983;158:2108–26. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.6.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horwitz MA. Formation of a novel phagosome by the Legionnaires' disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) in human monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1983;158:1319–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.4.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horwitz MA, Maxfield FR. Legionella pneumophila inhibits acidification of its phagosome in human monocytes. J. Cell. Biol. 1984;99:1936–43. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.6.1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swanson MS, Isberg RR. Association of Legionella pneumophila with the macrophage endoplasmic reticulum. Infect. Immun. 1995;63:3609–20. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3609-3620.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tilney LG, Harb OS, Connelly PS, Robinson CG, Roy CR. How the parasitic bacterium Legionella pneumophila modifies its phagosome and transforms it into rough ER: implications for conversion of plasma membrane to the ER membrane. J. Cell. Sci. 2001;114:4637–50. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.24.4637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derre I, Isberg RR. Legionella pneumophila replication vacuole formation involves rapid recruitment of proteins of the early secretory system. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:3048–53. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.5.3048-3053.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kagan JC, Stein MP, Pypaert M, Roy CR. Legionella subvert the functions of Rab1 and Sec22b to create a replicative organelle. J. Exp. Med. 2004;199:1201–11. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu H, Clarke M. Dynamic properties of Legionella-containing phagosomes in Dictyostelium amoebae. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:995–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kagan JC, Roy CR. Legionella phagosomes intercept vesicular traffic from endoplasmic reticulum exit sites. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2002;4:945–54. doi: 10.1038/ncb883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson CG, Roy CR. Attachment and fusion of endoplasmic reticulum with vacuoles containing Legionella pneumophila. Cell. Microbiol. 2006;8:793–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sturgill-Koszycki S, Swanson MS. Legionella pneumophila replication vacuoles mature into acidic, endocytic organelles. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:1261–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.9.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wieland H, Goetz F, Neumeister B. Phagosomal acidification is not a prerequisite for intracellular multiplication of Legionella pneumophila in human monocytes. J. Infect. Dis. 2004;189:1610–4. doi: 10.1086/382894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molmeret M, Bitar DM, Han L, Kwaik YA. Disruption of the phagosomal membrane and egress of Legionella pneumophila into the cytoplasm during the last stages of intracellular infection of macrophages and Acanthamoeba polyphaga. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:4040–51. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.4040-4051.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swanson MS, Fernandez-Moreira E. A microbial strategy to multiply in macrophages: the pregnant pause. Traffic. 2002;3:170–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.030302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shintani T, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy in health and disease: a double-edged sword. Science. 2004;306:990–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1099993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev. Cell. 2004;6:463–77. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amer AO, Swanson MS. Autophagy is an immediate macrophage response to Legionella pneumophila. Cell. Microbiol. 2005;7:765–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otto GP, et al. Macroautophagy is dispensable for intracellular replication of Legionella pneumophila in Dictyostelium discoideum. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;51:63–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marra A, Blander SJ, Horwitz MA, Shuman HA. Identification of a Legionella pneumophila locus required for intracellular multiplication in human macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1992;89:9607–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berger KH, Merriam JJ, Isberg RR. Altered intracellular targeting properties associated with mutations in the Legionella pneumophila dotA gene. Mol. Microbiol. 1994;14:809–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Segal G, Shuman HA. Characterization of a new region required for macrophage killing by Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 1997;65:5057–66. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5057-5066.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vogel JP, Andrews HL, Wong SK, Isberg RR. Conjugative transfer by the virulence system of Legionella pneumophila. Science. 1998;279:873–6. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5352.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sadosky AB, Wiater LA, Shuman HA. Identification of Legionella pneumophila genes required for growth within and killing of human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 1993;61:5361–73. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.5361-5373.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Komano T, Yoshida T, Narahara K, Furuya N. The transfer region of IncI1 plasmid R64: similarities between R64 tra and Legionella icm/dot genes. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;35:1348–59. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chien M, et al. The genomic sequence of the accidental pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Science. 2004;305:1966–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1099776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cazalet C, et al. Evidence in the Legionella pneumophila genome for exploitation of host cell functions and high genome plasticity. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:1165–73. doi: 10.1038/ng1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Segal G, Purcell M, Shuman HA. Host cell killing and bacterial conjugation require overlapping sets of genes within a 22-kb region of the Legionella pneumophila genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1998;95:1669–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagai H, Kagan JC, Zhu X, Kahn RA, Roy CR. A bacterial guanine nucleotide exchange factor activates ARF on Legionella phagosomes. Science. 2002;295:679–82. doi: 10.1126/science.1067025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chardin P, et al. A human exchange factor for ARF contains Sec7- and pleckstrinhomology domains. Nature. 1996;384:481–4. doi: 10.1038/384481a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conover GM, Derre I, Vogel JP, Isberg RR. The Legionella pneumophila LidA protein: a translocated substrate of the Dot/Icm system associated with maintenance of bacterial integrity. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;48:305–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vincent CD, Vogel JP. The Legionella pneumophila IcmS-LvgA protein complex is important for Dot/Icm-dependent intracellular growth. Mol. Microbiol. 2006b;61:596–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coers J, et al. Identification of Icm protein complexes that play distinct roles in the biogenesis of an organelle permissive for Legionella pneumophila intracellular growth. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;38:719–736. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bardill JP, Miller JL, Vogel JP. IcmS-dependent translocation of SdeA into macrophages by the Legionella pneumophila type IV secretion system. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:90–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ninio S, Zuckman-Cholon DM, Cambronne ED, Roy CR. The Legionella IcmS-IcmW protein complex is important for Dot/Icm-mediated protein translocation. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;55:912–926. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cambronne ED, Roy CR. The Legionella pneumophila IcmSW Complex Interacts with Multiple Dot/Icm Effectors to Facilitate Type IV Translocation. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e188. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rusch SL, Kendall DA. Interactions that drive Sec-dependent bacterial protein transport. Biochemistry. 2007;46:9665–73. doi: 10.1021/bi7010064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gomis-Ruth FX, Sola M, de la Cruz F, Coll M. Coupling factors in macromolecular type-IV secretion machineries. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2004;10:1551–65. doi: 10.2174/1381612043384817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu J, Frost LS. Mutations in the C-terminal region of TraM provide evidence for in vivo TraM-TraD interactions during F-plasmid conjugation. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:4767–73. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.14.4767-4773.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Atmakuri K, Ding Z, Christie PJ. VirE2, a type IV secretion substrate, interacts with the VirD4 transfer protein at cell poles of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;49:1699–713. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeo HJ, Savvides SN, Herr AB, Lanka E, Waksman G. Crystal structure of the hexameric traffic ATPase of the Helicobacter pylori type IV secretion system. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:1461–72. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buscher BA, et al. The DotL protein, a member of the TraG-coupling protein family, is essential for Viability of Legionella pneumophila strain Lp02. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:2927–38. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.9.2927-2938.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vincent CD, et al. Identification of the core transmembrane complex of the Legionella Dot/Icm type IV secretion system. Mol. Microbiol. 2006a;62:1278–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dumenil G, Isberg RR. The Legionella pneumophila IcmR protein exhibits chaperone activity for IcmQ by preventing its participation in high-molecular-weight complexes. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;40:1113–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dumenil G, Montminy TP, Tang M, Isberg RR. IcmR-regulated membrane insertion and efflux by the Legionella pneumophila IcmQ protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:4686–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309908200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.VanRheenen SM, Dumenil G, Isberg RR. IcmF and DotU are required for optimal effector translocation and trafficking of the Legionella pneumophila vacuole. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:5972–82. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5972-5982.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sexton JA, Miller JL, Yoneda A, Kehl-Fie TE, Vogel JP. Legionella pneumophila DotU and IcmF are required for stability of the Dot/Icm Complex. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:5983–3992. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5983-5992.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Das S, Chakrabortty A, Banerjee R, Roychoudhury S, Chaudhuri K. Comparison of global transcription responses allows identification of Vibrio cholerae genes differentially expressed following infection. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2000;190:87–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pukatzki S, et al. Identification of a conserved bacterial protein secretion system in Vibrio cholerae using the Dictyostelium host model system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2006;103:1528–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510322103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wall D, Kaiser D. Type IV pili and cell motility. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;32:1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Falkow S. Molecular Koch's postulates applied to microbial pathogenicity. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1988;10(Suppl 2):S274–6. doi: 10.1093/cid/10.supplement_2.s274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Falkow S. Molecular Koch's postulates applied to bacterial pathogenicity--a personal recollection 15 years later. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2:67–72. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Campodonico EM, Chesnel L, Roy CR. A yeast genetic system for the identification and characterization of substrate proteins transferred into host cells by the Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm system. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;56:918–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.VanRheenen SM, Luo ZQ, O'Connor T, Isberg RR. Members of a Legionella pneumophila family of proteins with ExoU (phospholipase A) active sites are translocated to target cells. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:3597–606. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02060-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Laguna RK, Creasey EA, Li Z, Valtz N, Isberg RR. A Legionella pneumophila-translocated substrate that is required for growth within macrophages and protection from host cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:18745–18750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609012103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Casanova JE. Regulation of Arf activation: the Sec7 family of guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Traffic. 2007;8:1476–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de Felipe KS, et al. Evidence for acquisition of Legionella type IV secretion substrates via interdomain horizontal gene transfer. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:7716–26. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.22.7716-7726.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen J, et al. Legionella effectors that promote nonlytic release from protozoa. Science. 2004;303:1358–1361. doi: 10.1126/science.1094226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shohdy N, Efe JA, Emr SD, Shuman HA. Pathogen effector protein screening in yeast identifies Legionella factors that interfere with membrane trafficking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:4866–4871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501315102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zusman T, et al. The response regulator PmrA is a major regulator of the icm/dot type IV secretion system in Legionella pneumophila and Coxiella burnetii. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;63:1508–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nagai H, et al. A C-terminal translocation signal required for Dot/Icm-dependent delivery of the Legionella RalF protein to host cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2005;102:826–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406239101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kubori T, Hyakutake A, Nagai H. Legionella translocates an E3 ubiquitin ligase that has multiple U-boxes with distinct functions. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;67:1307–1319. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Byrne B, Swanson MS. Expression of Legionella pneumophila virulence traits in response to growth conditions. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:3029–34. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3029-3034.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hales LM, Shuman HA. The Legionella pneumophila rpoS gene is required for growth within Acanthamoeba castellanii. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:4879–4889. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.16.4879-4889.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bachman MA, Swanson MS. RpoS co-operates with other factors to induce Legionella pneumophila virulence in the stationary phase. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;40:1201–1214. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hammer BK, Tateda ES, Swanson MS. A two-component regulator induces the transmission phenotype of stationary-phase Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;44:107–18. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tiaden A, et al. The Legionella pneumophila response regulator LqsR promotes host cell interactions as an element of the virulence regulatory network controlled by RpoS and LetA. Cell. Microbiol. (2007;9:2903–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Luo ZQ, Isberg RR. Multiple substrates of the Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm system identified by interbacterial protein transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2004;101:841–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304916101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bruggemann H, et al. Virulence strategies for infecting phagocytes deduced from the in vivo transcriptional program of Legionella pneumophila. Cell. Microbiol. 2006;8:1228–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Altman E, Segal G. The response regulator CpxR directly regulates the expression of several Legionella pneumophila icm/dot components as well as new translocated substrates. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:1985–96. doi: 10.1128/JB.01493-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Machner MP, Isberg RR. Targeting of host Rab GTPase function by the intravacuolar pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Dev. Cell. 2006;11:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Murata T, et al. The Legionella pneumophila effector protein DrrA is a Rab1 guanine nucleotide-exchange factor. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2006;8:971–7. doi: 10.1038/ncb1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ingmundson A, Delprato A, Lambright DG, Roy CR. Legionella pneumophila proteins that regulate Rab1 membrane cycling. Nature. 2007;450:365–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu Y, Luo ZQ. The Legionella pneumophila Effector SidJ Is Required for Efficient Recruitment of Endoplasmic Reticulum Proteins to the Bacterial Phagosome. Infect. Immun. 2007;75:592–603. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01278-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Goody RS, Rak A, Alexandrov K. The structural and mechanistic basis for recycling of Rab proteins between membrane compartments. Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 2005;62:1657–70. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-4486-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sivars U, Aivazian D, Pfeffer SR. Yip3 catalyses the dissociation of endosomal Rab-GDI complexes. Nature. 2003;425:856–9. doi: 10.1038/nature02057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Machner MP, Isberg RR. A bifunctional bacterial protein links GDI displacement to Rab1 activation. Science. 2007;318:974–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1149121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dorer MS, Kirton D, Bader JS, Isberg RR. RNA interference analysis of Legionella in Drosophila cells: exploitation of early secretory apparatus dynamics. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e34. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhou D, Chen LM, Hernandez L, Shears SB, Galan JE. A Salmonella inositol polyphosphatase acts in conjunction with other bacterial effectors to promote host cell actin cytoskeleton rearrangements and bacterial internalization. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;39:248–59. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Deiwick J, et al. The translocated Salmonella effector proteins SseF and SseG interact and are required to establish an intracellular replication niche. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:6965–72. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00648-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chang JH, et al. A high-throughput, near-saturating screen for type III effector genes from Pseudomonas syringae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2005;102:2549–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409660102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vinatzer BA, Jelenska J, Greenberg JT. Bioinformatics correctly identifies many type III secretion substrates in the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae and the biocontrol isolate P. fluorescens SBW25. Mol. Plant Microbe. Interact. 2005;18:877–88. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-18-0877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sarkar SF, Gordon JS, Martin GB, Guttman DS. Comparative genomics of host-specific virulence in Pseudomonas syringae. Genetics. 2006;174:1041–56. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.060996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dorer MS, Isberg RR. Non-vertebrate hosts in the analysis of host-pathogen interactions. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:1637–46. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Banga S, et al. Legionella pneumophila inhibits macrophage apoptosis by targeting pro-death members of the Bcl2 protein family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2007;104:5121–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611030104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Muller A, Hacker J, Brand BC. Evidence for apoptosis of human macrophage-like HL-60 cells by Legionella pneumophila infection. Infect. Immun. 1996;64:4900–4906. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.4900-4906.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gao LY, Abu Kwaik Y. Apoptosis in macrophages and alveolar epithelial cells during early stages of infection by Legionella pneumophila and its role in cytopathogenicity. Infect. Immun. 1999a;67:862–870. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.862-870.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gao LY, Abu Kwaik Y. Activation of caspase 3 during Legionella pneumophila-induced apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 1999b;67:4886–4894. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4886-4894.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kirby JE, Vogel JP, Andrews HL, Isberg RR. Evidence for pore-forming ability by Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;27:323–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Derre I, Isberg RR. Macrophages from mice with the restrictive Lgn1 allele exhibit multifactorial resistance to Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:6221–6229. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6221-6229.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zamboni DS, et al. The Birc1e cytosolic pattern-recognition receptor contributes to the detection and control of Legionella pneumophila infection. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:318–325. doi: 10.1038/ni1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Neumeister B, Faigle M, Lauber K, Northoff H, Wesselborg S. Legionella pneumophila induces apoptosis via the mitochondrial death pathway. Microbiol. 2002;148:3639–3650. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-11-3639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Molofsky AB, et al. Cytosolic recognition of flagellin by mouse macrophages restricts Legionella pneumophila infection. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:1093–1104. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Molmeret M, et al. Activation of caspase-3 by the Dot/Icm virulence system is essential for arrested biogenesis of the Legionella-containing phagosome. Cell. Microbiol. 2004;6:33–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ren T, Zamboni DS, Roy CR, Dietrich WF, Vance RE. Flagellin-deficient Legionella mutants evade caspase-1- and Naip5-mediated macrophage immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e18. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Abu-Zant A, et al. Anti-apoptotic signalling by the Dot/Icm secretion system of L. pneumophila. Cell. Microbiol. 2007;9:246–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Losick VP, Isberg RR. NF-kappaB translocation prevents host cell death after low-dose challenge by Legionella pneumophila. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:2177–2189. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Webster KA, Graham RM, Bishopric NH. BNip3 and signal-specific programmed death in the heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2005;38:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lee H, Paik SG. Regulation of BNIP3 in normal and cancer cells. Mol. Cells. 2006;21:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bruggemann H, Cazalet C, Buchrieser C. Adaptation of Legionella pneumophila to the host environment: role of protein secretion, effectors and eukaryotic-like proteins. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2006;9:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Arnoult D, et al. On the evolutionary conservation of the cell death pathway: mitochondrial release of an apoptosis-inducing factor during Dictyostelium discoideum cell death. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:3016–30. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.10.3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lam D, Golstein P. A specific pathway inducing autophagic cell death is marked by an IP3R mutation. Autophagy. 2008;4 doi: 10.4161/auto.5521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tresse E, Kosta A, Luciani MF, Golstein P. From autophagic to necrotic cell death in Dictyostelium. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2007;17:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Glockner G, et al. Identification and characterization of a new conjugation/type IVA secretion system (trb/tra) of Legionella pneumophila Corby localized on two mobile genomic islands. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2008;298:411–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Archer KA, Roy CR. MyD88-dependent responses involving Toll-like receptor 2 are important for protection and clearance of Legionella pneumophila in a mouse model of Legionnaires' disease. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:3325–33. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02049-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Asare R, Abu Kwaik Y. Early trafficking and intracellular replication of Legionella longbeachaea within an ER-derived late endosome-like phagosome. Cell. Microbiol. 2007;9:1571–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Alli OA, Zink S, von Lackum NK, Abu-Kwaik Y. Comparative assessment of virulence traits in Legionella spp. Microbiology. 2003;149:631–41. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.25980-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Graumann PL. SMC proteins in bacteria: condensation motors for chromosome segregation? Biochimie. 2001;83:53–9. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(00)01218-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Vergunst AC, et al. VirB/D4-dependent protein translocation from Agrobacterium into plant cells. Science. 2000;290:979–82. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5493.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lesser CF, Miller SI. Expression of microbial virulence proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae models mammalian infection. EMBO J. 2001;20:1840–9. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.8.1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Slagowski NL, Kramer RW, Morrison MF, LaBaer J, Lesser CF. A functional genomic yeast screen to identify pathogenic bacterial proteins. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e9. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wolfgang M, van Putten JP, Hayes SF, Dorward D, Koomey M. Components and dynamics of fiber formation define a ubiquitous biogenesis pathway for bacterial pili. EMBO J. 2000;19:6408–18. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Andrews HL, Vogel JP, Isberg RR. Identification of linked Legionella pneumophila genes essential for intracellular growth and evasion of the endocytic pathway. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:950–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.950-958.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Brand BC, Sadosky AB, Shuman HA. The Legionella pneumophila icm locus: a set of genes required for intracellular multiplication in human macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 1994;14:797–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]