Abstract

The purpose of this study was to test a version of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) for predicting safe sex behavior in a sample of 228 HIV-negative heterosexual methamphetamine users. We hypothesized that, in addition to TPB constructs, participants’ amount of methamphetamine use and desire to stop unsafe sex behaviors would predict intentions to engage in safer sex behaviors. In turn, we predicted that safer sex intentions would be positively correlated with participants’ percentage of protected sex. Hierarchical linear regression indicated that 48% of the total variance in safer sex intentions was predicted by our model, with less negative attitudes toward safer sex, greater normative beliefs, greater control beliefs, less methamphetamine use, less intent to have sex, and greater desire to stop unsafe sex emerging as significant predictors of greater safer sex intentions. Safer sex intentions were positively associated with future percent protected sex (p<.05). These findings suggest that, among heterosexual methamphetamine users, the TPB is an excellent model for predicting safer sex practices in this population, as are some additional factors (e.g., methamphetamine use). Effective interventions for increasing safer sex practices in methamphetamine user will likely include constructs from this model with augmentations to help reduce methamphetamine use.

Keywords: Theory of Planned Behavior, Safer Sex, Methamphetamine, Drug use

INTRODUCTION

Over 1/2 million individuals in the United States have suffered HIV-related deaths since tracking of these data began (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007). One population at elevated risk for contracting HIV is heterosexual methamphetamine users. Compared to nonmethamphetamine users, non-injection heterosexual methamphetamine users have significantly more sex partners, engage in significantly more anal sex, are less likely to use condoms, and are twice as likely to have sex with a prostitute or exchange sex for drugs (Molitor, Truax, Ruiz, & Sun, 1998). In addition, this population is four times more likely than non-methamphetamine users to have sex with an injection drug user (IDU). Other studies indicate that drug use is linked to sexual risk taking (Essien, Meshack, Peters, Ogungbade, & Osemene, 2005; Kalichman, Rompa, & Cage, 2000; Simbayi et al., 2006). In sum, this population is at increased risk of contracting HIV/AIDS or other sexually transmitted diseases.

Outside of abstinence, condom use is the most reliable method of preventing HIV infection. However, given that condom use is particularly low in this population (Molitor et al., 1998), it is important to identify factors which increase the likelihood these individuals will engage in safer sex practices. One model for explaining safer sex behaviors is the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991), which stipulates that attitudes toward a behavior, subjective norms regarding the behavior, and perceived behavioral control each predict one’s intention to actually perform a behavior. In turn, one’s intention predicts actual performance of the behavior. The theory of planned behavior has been successfully applied to a number of health behaviors, including weight loss (Schifter & Ajzen, 1985), maintenance of physical activity (Armitage, 2005), consumption of fruits and vegetables (Lien, Lytle, & Komro, 2002; Sjoberg, Kim, & Reicks, 2004), and condom use among non-drug using populations (Jemmott et al., 1992; Villarruel et al., 2004).

Although the TPB has received substantial support in a number of populations and for a variety of health behaviors, it is possible that within-group factors may also contribute to one’s intentions to engage in safer sex behaviors. For example, among methamphetamine users, level of drug use and intent to engage in safer sex practices may be related. Indeed, methamphetamine use has been related to risky sex in a number of studies (Clatts, Goldsamt, & Yi, 2005; Fernández et al., 2005; Halkitis, Parsons, & Stirratt, 2001; Purcell, Parsons, Halkitis, Mizuno, & Woods, 2001), although most consisted of men who have sex with men (MSM). Not surprisingly, methamphetamine use has been related to rising HIV transmission rates (Boddiger, 2005). Methamphetamine use may act to decrease one’s intention to engage in safer sex practices though physiologic means (Parks & Kennedy, 2004), including reduced ability to obtain a full or partial erection and delayed ejaculation (Bell & Trethowan, 1961; Galloway, Newmeyer, Knapp, Stalcup, & Smith, 1996), thereby making condom use less practical. Galloway and colleagues (1996) state that increased bleeding and abrasions may occur as a result of rougher sex while high on methamphetamine. Psychological effects of methamphetamine may also decrease one’s intentions to engage in safer sex. For example, it has been shown that 88% of methamphetamine users used the drug to enhance sexual pleasure (Semple, Patterson, & Grant, 2004). Specifically, methamphetamine users describe sexual experiences as being extremely more intense with methamphetamine and the drug is perceived as enhancing sexual performance. Further, methamphetamine users indicate that the drug contributes to their willingness to experiment sexually (Semple et al., 2004).

Depressive symptoms may also play a role in one’s intention to use condoms and reduce one’s actual use of condoms during sex. In a sample of HIV-positive women, greater depressive symptoms predicted reduced condom use (Lambert, Keegan, & Petrak, 2005). Greater self-reported depression is also associated with a higher number of sexual partners and reduced use of contraception among adolescent boys and girls (Kosunen, Kaltiala-Heino, Rimpelä, & Laippala, 2003) Finally, depressive symptoms were associated with an increased risk of unprotected sex in a sample of over 3,100 adolescent boys (Shrier, Harris, Sternberg, & Beardslee, 2001). Indeed, there is a high prevalence of lifetime depression among methamphetamine users (Semple et al., 2002).

A third factor that may increase the likelihood of intending to engage in safer sex practices is one’s desire to reduce unprotected sex. Although desire and intent to change are similar constructs, desire can be differentiated from intentions in that desire is more passive in nature compared to the more proactive state of intent. Further, while it is not necessary for desire to occur before one intends to change, we believe a stronger presence of desire to reduce unsafe sex practices will be associated with an increase in one’s intent to engage in safer sex.

The present study tests a modified version of the TPB in a sample of 228 HIV-negative, heterosexual methamphetamine users. We hypothesized the following factors would be significantly correlated with intentions to engage in safer sex behaviors: a) attitudes toward negotiating safer sex and condom use, b) perceptions of the social norms regarding safer sex, c) perceived control beliefs for condom use and negotiating safer sex, d) amount of meth used, e) depressive symptoms, and f) desire to stop unsafe sex. Further, we hypothesized that intentions to engage in safer sex practices would predict actual change in safer sex behaviors at 6-month follow-up.

METHODS

Participants

Participants in this study were recruited for a study examining the efficacy of a behavioral intervention for reducing unsafe sex practices in the context of ongoing methamphetamine use (Mausbach, Semple, Strathdee, Zians, & Patterson, 2007). As described by Mausbach et al., street outreach was used to recruit participants in neighborhoods with high concentrations of non-gay methamphetamine users and venues known to be meeting places of methamphetamine users (e.g., dance clubs, video arcades, street corners). In addition, snowball sampling techniques were used in which enrolled participants referred friends and acquaintances. Finally, referrals and brochures placed at health clinics, health service agencies, and community organizations were used.

Inclusion criteria for the study included being an HIV-negative heterosexual individual who reported they had snorted, smoked, or injected methamphetamine and had unprotected sex at least once during the previous 2 months. Participants were excluded if they were under 18 years of age, currently had a major psychiatric diagnosis with psychotic or suicidal symptoms, reported consistent use of condoms/dental dam for oral, vaginal, or anal sex with all partners during the previous two months, reported they were trying to get pregnant or trying to get a partner pregnant, or were currently enrolled in a drug treatment program. A total of 450 individuals met these inclusion/exclusion criteria and were enrolled in the study.

Measures

Details of the scales used in this study follow. In addition, copies of these scales may be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Safer Sex Practices

Participants were asked to report the number of times in the past 2 months they engaged in various sexual behaviors including anal, oral, and vaginal sex. For each sexual behavior endorsed, a follow-up question asked the number of times these sexual acts were protected (i.e., used a condom or oral dam). Using these data, we calculated the percentage of protected sex (Protected Sex ÷ Total Sex).

Intentions for Safer Sex Practices

Participants answered 3 questions regarding their intentions to use protection during sex over the next two months (e.g., “I intend to always use condoms during vaginal sex with all of my partners during the next two months”) (Fisher, Kimble Willcuts, Misovich, & Weinstein, 1998). Responses were on a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 = “Very Untrue” and 5 = “Very True”. An overall intentions score was created by average responses to these items. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .83.

Attitudes Toward Safer Sex Practices

Negative attitudes toward safer sex practices were calculated by averaging responses to 5 questions (e.g., “I believe condoms interfere with sexual pleasure”, “I believe that stopping to put on a condom ruins the moment”). Responses were given on a Likert scale ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 4 = “strongly agree”. Alpha reliability for this scale was .80.

Normative Beliefs

Three questions were used to assess each participant’s normative beliefs regarding safer sex practices (e.g., “Most people who are important to me think that I should always use condoms for vaginal sex with all my partners during the next two months”). Response choices ranged from 1 = “Very Untrue” to 5 = “Very True” (Fisher et al., 1998). Average responses to these three items were used to create an overall normative beliefs score, and the Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .81.

Control Beliefs

Control beliefs for safer sex practices were assessed using a scale developed by our team. This scale consisted of 18 items (e.g., “I can use a condom properly”; “I can interrupt sex to use a condom”; “I can delay penetrative sex if a condom is not available”. Responses for each item ranged from 1 = “Strongly Disagree” to 4 = “Strongly Agree”. Alpha reliability for this scale was .92.

Intentions for Sex

In addition to intentions for engaging in safer sex practices, we assessed each participant’s intent to engage in sex over the next two months using the following 3 questions: a) “I intend not to have oral sex during the next two months”, b) “I intend not to have vaginal sex during the next two months”, and c) “I intend not to have anal sex during the next two months”. Responses ranged from 1 = “Very Untrue” to 5 = “Very True” (Fisher et al., 1998). Each of the 3 items was reverse scored so that higher scores indicated greater intent to have sex, and the mean of these three items was used.

Methamphetamine Use

Participants were asked the number of grams of methamphetamine they used during the past 30 days.

Depressive Symptoms

All participants completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961), which is both a reliable and valid measure of depressive symptoms (Beck & Steer, 1993). Possible scores on this scale ranged from 0-60, with higher scores indicating greater experience of depressive symptoms.

Desire to Stop Unsafe Sex

Participants rated the extent to which they agreed with the following statement: “I want to stop having unprotected sex with my partners”. Response options were on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 4 “strongly agree”.

Intervention Conditions

After completion of the baseline interview, participants were randomized, via random number generator, to receive one of two psychosocial interventions. The first was a behavioral intervention known as Fast-Lane, and the second was a Diet and Exercise condition. Details on the content, format, and structure of these interventions can be found elsewhere (Mausbach et al., 2007).

Briefly, those randomized to the Fast-Lane intervention participated in four weekly 90-minute face-to-face (individual) counseling sessions primarily focusing on helping the individual engage in safer sex behaviors in the context of ongoing methamphetamine use. That is, reductions in methamphetamine use were not emphasized in the counseling session. Participants randomized to the Diet and Exercise condition received four 90-minute weekly face-to-face counseling sessions. Sessions focused on general nutrition (e.g., eating healthier) and tips for a healthier exercise routine (e.g., different types of exercise, benefits of exercise). Participants in the Diet and Exercise condition also received diet and exercise information tailored to the methamphetamine user (e.g., dangers of exercise and methamphetamine use).

Procedures and Data Analysis

Because questions were of a highly personal nature, all participants completed questionnaires through audio-computer assisted self interview (ACASI) technology, which offers maximum confidentiality and privacy. This procedure involved having participants listen to each question and its corresponding response categories, to which he/she selects the best answer using a computer mouse. In addition to increased privacy, this method eliminated the need for user literacy. Participants completed the ACASI questionnaires at baseline and again 6-months post-baseline.

Prior to conducting statistical analyses, all variables were examined for normality. To approximate normality, methamphetamine use required a log transformation and depressive symptoms required a square root transformation. To test our hypotheses, two separate hierarchical linear regressions were performed. In our first regression model, safer sex intentions was the dependent variable. Independent variables were entered into the following blocks: Block 1 = age, gender, and ethnicity; Block 2 = Theory of Planned Behavior constructs (i.e., attitudes toward safer sex behaviors, normative beliefs, and control beliefs); Block 3 = depressive symptoms, methamphetamine use, intentions to have sex, and desire to stop unsafe sex. For each block, we calculated change in R-square to determine the amount of additional variance accounted for by that particular set of variables.

In our second regression model, follow-up percent protected sex was our dependent variable. Block 1 included baseline percent protected sex and, because this study was conducted in the context of an intervention study (Mausbach, Semple, Strathdee, Zians, & Patterson, In Press), treatment condition was included as a covariate in this block (0 = Diet and Exercise; 1 = FAST-Lane). The primary variable of interest (safer sex intentions) was included in Block 2.

RESULTS

Participant Demographics and Dropout Information

Of the 450 enrolled participants, 28 did not adequately complete all the baseline measures. Participants who did not adequately complete baseline measures were significantly older (t =2.70, df = 448; p = .007) and used significantly less methamphetamine (t = -2.18, df = 434; p = .029) than those who completed baseline measures. Of the remaining 422 participants, 228 (54.0%) completed both baseline and follow-up assessments of sexual behaviors. Compared to those who completed both assessments, those who did not were significantly lower in their desire to stop unsafe sex (t = -2.14, df = 420, p = .033), but did not differ in any other study variables. Demographic characteristics of the 228 participants included in our analyses can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Sample (N = 228)

| Characteristic | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 36.4 (10.0) | 18-63 |

| Gender male, n (%) | 151 (66.2) | |

| Marital Status, n (%) | ||

| Married | 18 (7.9) | |

| Separated/Divorced | 78 (34.2) | |

| Widowed | 4 (1.8) | |

| Never Married | 128 (56.1) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 112 (49.1) | |

| African American | 63 (27.6) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 26 (11.4) | |

| Native American/Indian | 6 (2.6) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 4 (1.8) | |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| Some High School | 39 (17.1) | |

| High School Diploma/GED | 92 (40.3) | |

| Some College | 77 (33.8) | |

| College Degree or above | 20 (8.8) | |

| Employment Status, n (%) | ||

| Not employed | 165 (72.4) | |

| Full-time | 28 (12.3) | |

| Part-time | 35 (15.4) | |

| BDI score, M (SD) | 15.3 (10.3) | 0-51 |

| Methamphetamine use past month (grams), M (SD) | 9.8 (19.6) | 1-168 |

| Control Beliefs, M (SD) | 3.0 (0.6) | 1.0-4.0 |

| Attitudes Toward Safer Sex Behaviors, M (SD) | 2.6 (0.7) | 1.0-4.0 |

| Normative Beliefs, M (SD) | 3.5 (1.2) | 1.0-5.0 |

| Percentage of Protected Sex, M (SD) | 12.1 (19.3) | 0.0-93.0 |

| Desire to stop unsafe sex, M (SD) | 2.5 (1.1) | 1.0-4.0 |

| Intent to Have Sex, M (SD) | 3.9 (0.9) | 1.0-5.0 |

Predictors of Intention to Engage in Safer Sex

As expected, bivariate correlations indicated significant relations (p < .05) between the TPB constructs of attitudes toward safer sex, normative beliefs, and control beliefs and safer sex intentions (r = -.24, .49, and .27, respectively). Safer sex intentions were in turn significantly related to sexual risk behaviors at baseline (r = .28) and follow-up (r = .25).

Our first regression model examined the extent to which safer sex intentions was predicted by TPB constructs (normative beliefs, control beliefs, and attitudes toward safer sex behaviors), and additional factors potentially linked to safer sex intentions (i.e., methamphetamine use, desire to stop unsafe sex, intentions to have sex, depressive symptoms) while controlling for demographic characteristics. The resulting multiple correlation coefficient (R) from this model was .694, indicating that our regression model accounted for a total of 48.2% of the variance in safer sex intentions. Block 1, which included demographic characteristics, accounted for 3.4% of the overall variance (F = 2.61, df = 3, 224; p = .052). Within this block, minority participants reported greater safer sex intentions than Caucasian participants (t = 2.73, df = 224, p = .007).

Block 2, which included constructs from the theory of planned behavior, accounted for an additional 31.5% of the variance in safer sex intentions (ΔF = 33.00, df = 3, 221; p < .001). All three factors within this block significantly predicted greater safe sex intentions. That is, greater normative beliefs (t = 8.01, df = 221; p < .001), greater control beliefs (t = 2.50, df = 221; p = .013), and less negative attitudes toward safer sex behaviors (t = -2.16, df = 221; p = .032) each predicted greater intention to engage in safer sex behaviors.

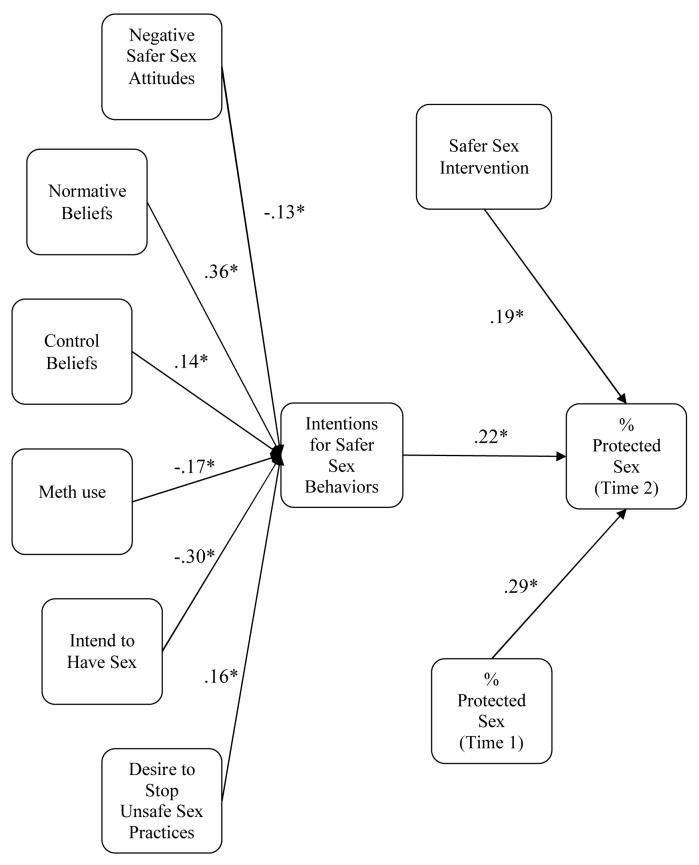

Block 3 included additional factors potentially linked to safer sex intentions. This block accounted for an additional 14.9% of variance beyond that explained by demographics and TPB constructs (ΔF = 15.60, df = 4, 217; p < .001). Lower methamphetamine use (t = -3.10, df = 217, p = .002), greater desire to stop unsafe sex (t = 3.00, df = 217, p = .003), and decreased intentions to have sex (t = -5.70, df = 217, p < .001) were associated with greater safer sex intentions. Also within block 3, all three constructs of TPB remained significant predictors of safer sex behaviors as follows: a) Normative beliefs (t = 6.66, df = 217; p < .001), b) Control beliefs (t = 2.49, df = 217; p = .013), and c) attitudes toward safer sex behaviors (t = -2.37, df = 217, p = .019). Finally, male gender (t = 2.79, df = 217; p = .006) and minority status (t = 2.27, df = 217, p = .024) were significant predictors of greater safer sex intentions within this block. Standardized beta coefficients for the final model are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Results of the regression models using an expanded Theory of Planned Behavior. Values on the paths are standardized regression coefficients after controlling for other factors in the model. * p < .05.

Relations between Intention and Percentage of Protected Sex

Our second regression model examined factors that predicted follow-up percentage of protected sex. A total of 21.9% of the variance in follow-up percent protected sex was accounted for by the predictors in our model, with safer sex intentions accounting for 4.3% of unique variance. Greater baseline safer sex intentions was a significant predictor of follow-up percent protected sex (t = 3.50, df = 224, p = .001), even when controlling for baseline percent protected (t = 4.50, df = 224, p < .001) and treatment condition (t = 3.18, df = 224, p = .002).

DISCUSSION

This study tested a modified version of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) for predicting both safer sex intentions and actual engagement in safer sex in a sample of HIV-negative heterosexual methamphetamine users. According to this model, the three constructs of attitudes toward condoms, social norms regarding condom use, and perceived control beliefs for safer sex behaviors should significantly predict one’s intention to engage in safer sex (Ajzen, 1991). Our results provide clear support for this model. Specifically, we found that more positive attitudes toward condoms, greater expectations from their peers to engage in safer sex behaviors, and greater control over negotiating safer sex and using condoms all significantly predicted intention to use condoms during sex. Further, our results expand this model by identifying 3 additional factors that predict intention to engage in safer sex in this population. Specifically, greater desire to stop unsafe sex was associated with greater intention to practice safer sex, whereas higher levels of methamphetamine use and greater intentions to engage in sex were associated with reduced intention to practice safer sex behaviors.

Also consistent with the theory of planned behavior, safer sex intentions significantly predicted behavioral outcomes (i.e., future safer sex behavior). That is, individuals who reported more intention to engage in safer sex actually used condoms a greater percentage of the time they had sex. We acknowledge that these data are correlational in nature, and therefore urge caution in interpreting our results as causal. Nonetheless, these results may have implications for the development of interventions for increasing safer sex practices in methamphetamine-using individuals. First, it would be interesting to test whether or not reducing methamphetamine use increases intentions to practice safer sex, which in turn decreases risky sexual behaviors. That is, interventions designed to reduce risky sexual behavior may wish to incorporate cognitive-behavioral and contingency management components for reducing methamphetamine use. Indeed, others have demonstrated the efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral intervention with contingency management for reducing methamphetamine use and sexual risk behaviors in a population of methamphetamine-dependent gay and bisexual men, although the authors did not examine whether change in methamphetamine use mediated change in sexual risk behavior (Shoptaw et al., 2005). Future studies may want to examine this effect.

We found that desire to stop risky sex behaviors was associated with intentions to use condoms during sex. We believe this finding is interesting because it suggests that motivational interviewing (MI) (Miller & Rollnick, 1991) may be useful for reducing risky sex behaviors in this population. In particular, MI seeks to produce “change talk”, or a desire to change, which in turn strengthens one’s commitment to actual change. We believe use of MI to elicit “change talk” for risky sexual behaviors in methamphetamine-using individuals may be an important component of risk-reduction interventions. MI may be used prior to an existing intervention for reducing sexual risk behaviors or can be integrated into these interventions as a means of augmenting their effects. Again, our study was correlational, and these suggestions should be tested scientifically to determine their merit.

Weaker intentions for having sex were one of the best predictors of intention to engage in safer sex behaviors. Specifically, individuals who did not intend to have sex were more likely to report intentions to engage in safer sex behavior. While this intuitively makes sense, other factors may also have played a role in this relationship. Specifically, individuals who had lower intentions to have sex also tended to report stronger social norms for safer sex (r = -.15), reduced use of methamphetamine (r = .15), and increased desire to stop unsafe sex (r = -.12). Therefore, it seems likely that a combination of these factors played a role in explaining this relationship. Researchers may wish to further examine factors that explain a relationship between sex intentions and safer sex intentions.

There are limitations to this study, including the volunteer sample and high attrition rate. Indeed, of participants completing baseline measures, 46% did not complete their follow-up measures. This prevented us from testing the full model in all participants who completed baseline measures. While it would be ideal to know how our expanded model performs in predicting safer sex intentions and sexual risk behavior among a full sample of participants, we believe the accuracy of our model for predicting safer sex intentions among the sub-sample of 228 participants (i.e., 48.2% of variance explained) suggests this model may perform particularly well. Nonetheless, as discussed in our previous manuscript (Mausbach et al., 2007), methamphetamine-using individuals are difficult to track over time, and 20% of participants in this sample were incarcerated over the course of the study. Those participants who did not complete follow-up assessments reported less desire to stop unsafe sex, suggesting this sample was “treatment seeking” and more likely to change sexual behavior over the 6-month study period. Whether these results apply to non-treatment seeking methamphetamine users is unclear, and future research should replicate these results in this sample.

In sum, we find strong support for a model of sexual risk behavior in a sample of HIV-negative heterosexual methamphetamine users, as indicated by our model explaining nearly 50% of the variance in safer sex intentions. In addition to increasing efficacy for, altering normative beliefs and improving positive attitudes toward safe sex behaviors, our model suggests additional targets for interventions designed to increase safer sex practices in this population. These targets include increasing one’s desire to change sexual risk behavior, reducing amount of methamphetamine used, and reducing depressive symptoms. We anticipate interventions incorporating techniques targeting these components will demonstrate efficacy for increasing safe sex practices in this high risk population.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health award 061146.

REFERENCES

- Ajzen I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage CJ. Can the theory of planned behavior predict the maintenance of physical activity? Health Psychology. 2005;24(3):235–245. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell DS, Trethowan WH. Amphetamine addiction and disturbed sexuality. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Boddiger D. Metamphetamine use linked to rising HIV transmission. Lancet. 2005;365(9466):1217–1218. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74794-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2005 (Vol 17) US Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Clatts MC, Goldsamt LA, Yi H. Club drug use among young men who have sex with men in NYC: A preliminary epidemiological profile. Substance Use & Misuse. 2005;40(910):1317–1330. doi: 10.1081/JA-200066898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essien EJ, Meshack AF, Peters RJ, Ogungbade GO, Osemene NI. Strategies to prevent HIV transmission among heterosexual African-American men. BMC Public Health. 2005;5(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández MI, Bowen GS, Varga LM, Collazo JB, Hernandez N, Perrino T, et al. High rates of club drug use and risky sexual practices among Hispanic men who have sex with men in Miami, Florida. Substance Use & Misuse. 2005;40(910):1347–1362. doi: 10.1081/JA-200066904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Willcuts D. L. Kimble, Misovich SJ, Weinstein B. Dynamics of sexual risk behavior in HIV-infected men who have sex with men. AIDS & Behavior. 1998;2(2):101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Galloway GP, Newmeyer J, Knapp T, Stalcup SA, Smith D. A controlled trial of imipramine for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1996;13(6):493–497. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(96)00154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Parsons JT, Stirratt MJ. A double epidemic: Crystal methamphetamine drug use in relation to HIV transmission among gay men. Journal of Homosexuality. 2001;41(2):17–35. doi: 10.1300/J082v41n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M. Sexually transmitted infections among HIV seropositive men and women. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2000;76(5):350–354. doi: 10.1136/sti.76.5.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosunen E, Kaltiala-Heino R, Rimpelä M, Laippala P. Risk-taking sexual behaviour and self-reported depression in middle adolescence--A school-based survey. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2003;29(5):337–344. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2003.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert S, Keegan A, Petrak J. Sex and relationships for HIV positive women since HAART: A quantitative study. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2005;81(4):333–337. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.013516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lien N, Lytle LA, Komro KA. Applying theory of planned behavior to fruit and vegetable consumption of young adolescents. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2002;16(4):189–197. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-16.4.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Semple SJ, Strathdee SA, Zians J, Patterson TL. Efficacy of a behavioral intervention for increasing safer sex behaviors in HIV-negative, heterosexual methamphetamine users: Results from the Fast-Lane study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;34:263–274. doi: 10.1007/BF02874551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Semple SJ, Strathdee SA, Zians J, Patterson TL. (In Press). Efficacy of a behavioral intervention for increasing safer sex behaviors in HIV-negative, heterosexual methamphetamine users: Results from the Fast-Lane study Annals of Behavioral Medicine [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. Guilford Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Molitor F, Truax SR, Ruiz JD, Sun RK. Association of methamphetamine use during sex with risky sexual behaviors and HIV infection among non-injection drug users. The Western Journal of Medicine. 1998;168(2):93–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Kennedy CL. Club drugs: Reasons for and consequences of use. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2004;36(3):295–302. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2004.10400030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell DW, Parsons JT, Halkitis PN, Mizuno Y, Woods WJ. Substance use and sexual transmission risk behavior of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13(12):185–200. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schifter DE, Ajzen I. Intention, perceived control, and weight loss: an application of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;49(3):843–851. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.49.3.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. Determinants of condom use stage of change among heterosexually-identified methamphetamine users. AIDS and Behavior. 2004;8(4):391–400. doi: 10.1007/s10461-004-7323-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrier LA, Harris SK, Sternberg M, Beardslee WR. Associations of depression, self-esteem, and substance use with sexual risk among adolescents. Preventive Medicine. 2001;33(3):179–189. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC, Cain D, Cherry C, Jooste S, Mathiti V. Alcohol and risk for HIV/AIDS among sexually transmitted infection clinic patients in Cape Town, South Africa. Substance Abuse. 2006;27(4):37–43. doi: 10.1300/j465v27n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjoberg S, Kim K, Reicks M. Applying the theory of planned behavior to fruit and vegetable consumption by older adults. Journal of Nutrition for the Elderly. 2004;23(4):35–46. doi: 10.1300/J052v23n04_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]