Abstract

This study is a preliminary examination of the Activity Restriction Model of depressive symptoms. A total of 16 elderly Alzheimer's caregivers and 9 non-caregivers completed measures of activity restriction and depressive symptoms. Mediation was tested using the Sobel test with bootstrapping procedures. Results indicated that caregivers experienced significant elevations in depressive symptoms and activity restriction relative to non-caregivers (p < .05). Activity restriction significantly mediated the relationship between caregiving status and depressive symptoms (z = 2.29, p = .031), accounting for 86% of this relationship. Behavioral interventions for depression might be particularly relevant for Alzheimer's caregivers to reduce activity restriction and, thus, depressive symptoms.

Keywords: Depression, Activity Restriction Model, Behavior Therapy, Alzheimer's Disease, Caregiving

1. Introduction

Approximately 22% of dementia caregivers experience a depressive disorder, and caregivers' risk for experiencing a depressive disorder is approximately 3 to 38 times greater than that of non-caregivers (Cuijpers, 2005). This is not surprising considering the high level of burden experienced by caregivers, including their care recipients' increased memory and behavior problems, need for aid in performing daily activities, and emotional and psychiatric disturbance(s). A number of studies have shown that depressive symptoms are associated with health outcomes (Covinsky, Fortinsky, Palmer, Kresevic, & Landefeld, 1997; van der Kooy et al., 2007; Wassertheil-Smoller et al., 2004). Among caregivers, depressive symptoms may be particularly problematic because they have been associated with sympathetic hyperarousal to acute stressors (Mausbach et al., 2005), elevated plasma concentrations of the pro-inflammatory cytokine Interleukin-6 (IL-6), and ultimately to downstream health consequences such as cardiovascular disease (Lee, Colditz, Berkman, & Kawachi, 2003; Mausbach, Patterson, Rabinowitz, Grant, & Schulz, 2007). Therefore, given their impact on overall well-being, depressive symptoms are considered some of the most pressing concerns for this population.

The Activity Restriction Model (Williamson & Shaffer, 2000) suggests that major life stressors that result in restriction of normal or pleasurable activities will result in increased depressive symptoms. The Activity Restriction Model thereby proposes that activity restriction serves to mediate the relations between life stress and depressive symptoms. Williamson and colleagues have tested and found support for the Activity Restriction Model in several stressed populations, including limb amputees (Williamson, Schulz, Bridges, & Behan, 1994), breast cancer patients (Williamson, 2000), cancer caregivers (Williamson, Shaffer, & Schulz, 1998), and community-residing elderly outpatients (Williamson & Schulz, 1992).

To date, formal testing of the Activity Restriction Model among Alzheimer's caregivers has not been published. One study of a sample of dementia caregivers found that reduced engagement in pleasurable activities was associated with greater depressive symptoms (Thompson et al., 2002). However, this study did not examine the relations between caregiving stress and pleasurable activity; nor did they test a mediating model in which engagement in activities mediated the relations between stress and depressive symptoms. Nonetheless, the Activity Restriction Model is highly attractive for explaining depressive symptoms in this population given the disruption that caregiving has on engagement in normal activities. Indeed, caregivers report spending less time with other family members, giving up vacations, hobbies, or social activities, and getting less exercise than before caregiving (Alzheimer's Association and National Alliance for Caregiving, 2004; Clark & Bond, 2000). Others have found that dementia caregivers report greater disruption to social activities relative to non-caregivers (Haley, Levine, Brown, Berry, & Hughes, 1987) and caregivers of non-demented patients (Meller, 2001). Time spent in pleasurable activities is likely superseded by the considerable amount of time caregivers spend providing direct assistance to their care recipients (Ory, Hoffman, Yee, Tennstedt, & Schulz, 1999).

The purpose of this study was to conduct a preliminary test of the Activity Restriction Model in a sample of 16 elderly spousal Alzheimer's caregivers and 9 non-caregiver controls. Caregivers were hypothesized to experience greater symptoms of depression and activity restriction than their non-caregiver counterparts. Further, activity restriction was hypothesized to mediate the relations between caregiving status and depressive symptoms.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants were 25 older adults enrolled in the Alzheimer Caregiver Project (ACP) at the University of California, San Diego. Sixteen of the participants were spouses of an individual with Alzheimer's disease, and 9 were spouses of “healthy” (i.e., non-demented) individuals. Participants were primarily elderly (Mean age = 68.1 ± 10.7 years) and female (76%), and over half (54.5%) had greater than a high school education. Thirteen caregivers (81.2%) identified themselves as Caucasian and the remaining 3 identified themselves as Hispanic/Latino. All non-caregivers identified themselves as Caucasian. Caregivers were recruited through area Alzheimer's caregiver support groups, health fairs, and referrals from either the UCSD Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (ADRC) or other caregivers participating in the project. Non-caregiving controls were most often recruited through referral from caregiving participants and through area health fairs. All participants provided written, informed consent, and the project was approved by the UCSD Institutional Review Board (IRB).

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Demographic Characteristics

All participants were assessed for a number of demographic characteristics including age, gender, years married, educational attainment, and monthly household income.

2.2.2 Depressive Symptoms

All participants completed the Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression scale (CES-D)(Radloff, 1976). For this scale, participants were asked to respond to 20 statements by rating often they felt that way during the past week. Responses were as follows: 0 = “rarely or none of the time (<1 day)”; 1 = “some or a little of the time (1-2 days)”; 2 = “Occasionally or a moderate amount of time (3-4 days)”; and 4 = “Most or almost all the time (5-7 days)”. Individuals scoring 16 or greater on the CES-D have traditionally been considered “at risk” for clinical depression. Alpha reliability for this sample was .75.

2.2.3 Activity Restriction

Activity restriction was assessed using the Activity Restriction Scale (ARS) (Williamson & Schulz, 1992), which asks participants to what extent they have generally been restricted from engaging in 9 social and recreational activities (e.g., working on hobbies, sports and recreation, maintaining friendships). Responses are rated on a 5-point scale from 0 = “never or seldom did this” to 4 = “greatly restricted”. Scores could range from 0 to 36, and alpha reliability for the current sample was .90.

2.3 Data Analysis

Our analytic plan was to test whether or not activity restriction significantly mediated the relations between caregiving status and depressive symptoms. Mediation analyses followed the procedures described by Baron and Kenny (Baron & Kenny, 1986) and elaborated by Holmbeck (Holmbeck, 2002). Specifically, four regression analyses were conducted: 1) Depressive symptoms were regressed onto caregiving status, 2) activity restriction was regressed onto caregiving status, 3) depressive symptoms were regressed onto activity restriction, and 4) depressive symptoms were regressed onto both activity restriction and caregiving status. In this fourth and final regression, a significant reduction (from models 1 and 2 above) in the coefficient for caregiving status, but not activity restriction, suggested mediation. To evaluate whether mediation was significant, the Sobel test with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) (Sobel, 1982) was conducted using the bootstrapping procedure outlined by Preacher and Hayes (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). As described by Preacher and Hayes, bootstrapping is advantages for two reasons. First, it is nonparametric in nature and allows effect size estimation without assumption that the variables or the sampling distribution of the statistic are normal. Second, bootstrapping can be applied with greater confidence than non-bootstrapping approaches when using small sample sizes. These factors made using the bootstrapping procedure advantageous for the current study, which had a small sample size. A total of 2,000 bootstrapping samples were utilized in the current study.

Because an alternative model might be envisioned in which greater experience of depressive symptoms might mediate increased activity restriction, we conducted a secondary, exploratory analysis in which the placement of activity restriction and depressive symptoms in the model were reversed. That is, depressive symptoms were considered the mediator between caregiving status and activity restriction. The same procedures described above were used to test this model.

3. Results

3.1 Participant Characteristics

Prior to analysis of activity restriction and depressive symptoms, demographic characteristics of caregivers and non-caregivers were compared using t-tests and chi-square statistics for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Results indicated that the two groups were comparable in terms of age, years married, gender, education, and monthly income (see Table 1). Caregivers were marginally more likely to have a CES-D score greater or equal to 16 (χ2 = 3.78, df = 1, p = .052).

3.2 Test of the Activity Restriction Model

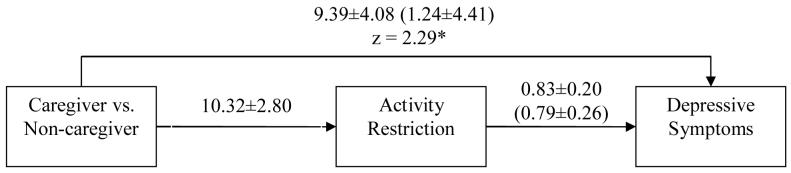

Our first regression examined the relations between caregiving status and depressive symptoms. Results indicated that caregivers had significantly greater depressive symptoms compared to non-caregivers (B = 9.39; t = 2.30, df = 23, p = .031). Our second regression, which examined the relations between caregiving status and activity restriction, was also significant (B = 10.32; t = 3.68, df = 23, p = .001). Third, activity restriction was significantly associated with depressive symptoms (B = 0.83; t = 4.12, df = 23, p < .001). Our final regression included both caregiving status and activity restriction as predictors of depressive symptoms. In this model, activity restriction remained a significant predictor of depressive symptoms (B = 0.79; t = 3.03, df = 22, p = .006), but caregiving status did not (B = 1.24; t = 0.28, df = 22, p = .781). The Sobel test of the indirect effect was significant (mean = 7.83; 95% CI = 0.03-17.76). We then used the formula provided by MacKinnon and Dwyer (MacKinnon & Dwyer, 1993) to estimate the percentage of the caregiving status to depressive symptoms path was accounted for by activity restriction. According to Holmbeck (Holmbeck, 2002), full mediation exists when the mediator accounts for 100% of the total effect. Results of our model indicated that activity restriction accounted for 86.8% of the path from caregiving status to depressive symptoms. The mediational model is presented graphically in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mediational model for the association between caregiver status and depressive symptoms, as mediated by activity restriction. Values on paths represent unstandardized coefficients ± SE. Coefficients in parentheses are from equations that include both caregiver status and activity restriction as predictors of depressive symptoms. Activity restriction accounted for 86% of the caregiver to depressive symptoms path.

3.3 Secondary Analysis – Depressive Symptoms as the Mediator of Activity Restriction

Our secondary analysis placed depressive symptoms as the mediating factor between caregiver status and activity restriction. Results of the direct effects of caregiving status on CES-D and Activity Restriction Scale scores are the same as our primary analysis described in section 3.2 above. The relations between CES-D scores and Activity Restriction Scale scores were also significant (B = 0.51; t = 4.12, df = 23, p < .001). However, in the final regression model, both caregiving status (B = 6.82; t = 2.55, df = 22, p = .018) and depressive symptoms (B = 0.37; t = 3.03, df = 22, p = .006) emerged as significant predictors of activity restriction. Bootstrapping results for the indirect effect were also not significant, as indicated by the 95% CI crossing over ‘0’ (mean = 3.38, 95% CI = −0.001-7.094; p > .05).

4. Discussion

Alzheimer's caregivers are at increased risk of experiencing depressive symptoms compared to their non-caregiving counterparts. The current study tested whether the Activity Restriction Model was a useful means of explaining differences in depressive symptoms between elderly Alzheimer's caregivers and non-caregiving controls. Indeed, results indicated that activity restriction significantly mediated the relations between caregiving status and depressive symptoms, with nearly 87% of the between-group differences being accounted for by activity restriction. These results are consistent with other research on the Activity Restriction Model (Williamson & Schulz, 1992, 1995; Williamson et al., 1994). However, whereas other research has examined the model among non-Alzheimer's caregivers (e.g., cancer caregivers), the current study is the first to test the model using Alzheimer's caregivers and non-caregiving control participants. Alzheimer's caregivers are unique in that research indicates they experience significantly higher levels of burden and psychiatric morbidity relative to other caregivers (Ory et al., 1999). Further, previous research did not formally test mediation using the Sobel statistic or provide the amount of variation in depressive symptoms was accounted for by activity restriction. This study, however, offered more advanced statistical testing of the Activity Restriction Model, including a “reverse” test in which depressive symptoms were placed as the mediator of activity restriction. In this latter analysis, results were not significant, thereby offering future research a glimpse at the potentially high importance of activity restriction for explaining symptoms of depression in Alzheimer's caregivers.

Perhaps the most important implication of this study is that activity restriction can be easily identified (i.e., observed) and clearly defined in behavioral terms. These factors make engagement in social and recreational activities a manageable target for behavioral interventions. Both behavioral and cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT) can be used to increase caregivers' activity levels and exposure to pleasurable environmental stimuli. Interestingly, recent literature has called into question the effectiveness of the cognitive components of CBT (Jacobson et al., 1996; Jacobson & Gortner, 2000). Rather, this literature suggests that behavioral interventions, such as those described by Lewinsohn (Lewinsohn, 1974) and Jacobson (Jacobson, Martell, & Dimidjian, 2001), may be particularly efficacious for reducing depressive symptoms. Indeed, caregiving interventions based on increasing caregivers' exposure to pleasant events have been shown to be efficacious (Coon, Thompson, Steffen, Sorocco, & Gallagher-Thompson, 2003; Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2000), although neither of these studies tested whether increased engagement in activities mediated the efficacy of the intervention for decreasing depressive symptoms. Future research should examine this mechanistic possibility.

This study was limited by its small sample, which places restrictions the generalizability of the findings and prevented the inclusion of covariates that might also explain between-groups differences in depressive symptoms. Most notable among these would be health symptoms and practice of avoidant coping, both of which have both shown to be powerful predictors of depressive symptoms among Alzheimer's caregivers (Schulz, O'Brien, Bookwala, & Fleissner, 1995). As such, these results should be considered preliminary and interpreted with caution. Replication of these findings, however, should be considered an important priority, as duplication of these results may have important implications for the treatment of depression in caregivers.

Another limitation was the cross-sectional nature of this study, thereby precluding temporal precedence from being established. Indeed, depressive symptoms may lead to reduced engagement in pleasurable activities, which in turn might exacerbate depressive symptoms. This phenomenon, commonly referred to as the “vicious cycle” or “downward spiral” in behavioral research, is difficult to establish statistically. Experimental manipulation of an independent variable with simultaneous control for extraneous variables is a key means of understanding the causal impact of one variable on another. In the context of the present research, one means of accomplishing this is through a randomized clinical trial of a behavioral intervention, whereby participants' engagement in pleasurable activities and exposure to environmental reinforcement can be “manipulated” via intervention components. Another means of establishing temporal relations between variables is through conducting prospective research. For example, repeated observations of the variables may be made over time and lagged relationships between these variables may be examined (Mausbach, Coon, Patterson, & Grant, In press). While our current study was cross-sectional, we did statistically explore the possibility that depressive symptoms mediated the relations between caregiving status and activity restriction. Results of this analysis were not significant, suggesting that activity restriction is better modeled as the mediating factor than the dependent variable.

We did not determine the presence of clinical depression via objective diagnostic assessment techniques. Rather, we focused on assessing caregivers' self-reported experience of depressive symptoms (i.e., CES-D scores). Indeed, the CES-D is typically used as a first step (i.e., a screening tool) in a more reliable diagnostic process. As such, it is unclear to what extent our sample suffered from a major depression diagnosis. Future studies may wish to incorporate a diagnostic assessment that includes more objective assessment of depressive disorders.

Despite its limitations, this study offers a preliminary look at the potential role of activity restriction in explaining increased depressive symptoms in elderly Alzheimer's caregivers relative to non-caregivers. Future research should consider a number of approaches to clarify these effects, including longitudinal studies of these relations (e.g., a randomized clinical trial of behavioral interventions for caregivers) and statistical inclusion of covariates that might also explain variance in depressive symptoms (e.g., health symptoms and avoidance coping). Overall, however, activity restriction appears to be a strong candidate for explaining depressive symptoms in this population.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging through awards 15301 and 23989.

References

- Alzheimer's Association and National Alliance for Caregiving Families Care: Alzheimer's Caregiving in the United States. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MS, Bond MJ. The effect on lifestyle activities of caring for a person with dementia. Psychology, Health, & Medicine. 2000;5(1):13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Coon DW, Thompson L, Steffen A, Sorocco K, Gallagher-Thompson D. Anger and depression management: Psychoeducational skill training interventions for women caregivers of a relative with dementia. The Gerontologist. 2003;43(5):678–689. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.5.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covinsky KE, Fortinsky RH, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, Landefeld CS. Relation between symptoms of depression and health status outcomes in acutely ill hospitalized older adults. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1997;126(6):417–425. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-6-199703150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P. Depressive disorders in caregivers of dementia patients: A systematic review. Aging & Mental Health. 2005;9(4):325–330. doi: 10.1080/13607860500090078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D, Lovett S, Rose J, McKibbin C, Coon D, Futterman A, et al. Impact of psychoeducational interventions on distressed family caregivers. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology. 2000;6(2):91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Haley WE, Levine EG, Brown SL, Berry JW, Hughes GH. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1987;35(5):405–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1987.tb04661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27(1):87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson DL, Martell CR, Dimidjian S. Behavioral Activation treatment for depression: Returning to contextual roots. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2001;8(3):255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Dobson KS, Truax PA, Addis ME, Koerner K, Gollan JK, et al. A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1996;64(2):295–304. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Gortner ET. Can depression be de-medicalized in the 21st century: Scientific revolutions, counter-revolutions and the magnetic field of normal science. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 2000;38(2):103–117. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Colditz GA, Berkman LF, Kawachi I. Caregiving and risk of coronary heart disease in U.S. women: A prospective study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;24(2):113–119. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00582-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM. A behavioral approach to depression. In: Friedman RJ, Katz MM, editors. The Psychology of Depression: Contemporary Theory and Research. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1974. pp. 157–178. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation Review. 1993;17(2):144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Coon DW, Patterson TL, Grant I. Engagement in activities is associated with affective arousal in Alzheimer's caregivers: A preliminary examination of the temporal relations between activity and affect. Behavior Therapy. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.10.002. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Dimsdale JE, Ziegler MG, Mills PJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Patterson TL, et al. Depressive symptoms predict norepinephrine response to a psychological stressor task in Alzheimer's caregivers. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67(4):638–642. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000173312.90148.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Patterson TL, Rabinowitz Y, Grant I, Schulz R. Depression and Distress Predict time to Cardiovascular Disease in Dementia Caregivers. Health Psychology. 2007;26(5):539–544. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.5.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meller S. A comparison of the well-being of family caregivers of elderly patients hospitalized with physical impairments versus the caregivers of patients hospitalized with dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2001;2(2):60–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ory MG, Hoffman RR, 3rd, Yee JL, Tennstedt S, Schulz R. Prevalence and impact of caregiving: A detailed comparison between dementia and nondementia caregivers. The Gerontologist. 1999;39(2):177–185. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36(4):717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1976;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, O'Brien AT, Bookwala J, Fleissner K. Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of dementia caregiving: Prevalence, correlates, and causes. The Gerontologist. 1995;35(6):771–791. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In: Leinhart S, editor. Sociological Methodology. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson LW, Solano N, Kinoshita L, Coon DW, Mausbach B, Gallagher-Thompson D. Pleasurable activities and mood: Differences between Latina and Caucasian dementia family caregivers. Journal of Mental Health and Aging. 2002;8(3):211–224. [Google Scholar]

- van der Kooy K, van Hout H, Marwijk H, Marten H, Stehouwer C, Beekman A. Depression and the risk for cardiovascular diseases: Systematic review and meta analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;22(7):613–626. doi: 10.1002/gps.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassertheil-Smoller S, Shumaker S, Ockene J, Talavera GA, Greenland P, Cochrane B, et al. Depression and cardiovascular sequalae in postmenopausal women: The Women's Health Initiative (WHI) Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004;164:289–298. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson GM. Extending the activity restriction model of depressed affect: Evidence from a sample of breast cancer patients. Health Psychology. 2000;19(4):339–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson GM, Schulz R. Pain, activity restriction, and symptoms of depression among community-residing elderly adults. Journal of Gerontology. 1992;47(6):P367–372. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.6.p367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson GM, Schulz R. Activity restriction mediates the association between pain and depressed affect: A study of younger and older adult cancer patients. Psychology and Aging. 1995;10(3):369–378. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.10.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson GM, Schulz R, Bridges MW, Behan AM. Social and psychological factors in adjustment to limb amputation. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality. 1994;9(5):249–268. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson GM, Shaffer DR. The activity restriction model of depressed affect: Antecedents and consequences of restricted normal activities. In: Williamson GM, Shaffer DR, Parmelee PA, editors. Physical Illness and Depression in Older Adults: A Handbook of Theory, Research, and Practice. Kluwer Academic/Plenum; New York: 2000. pp. 173–200. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson GM, Shaffer DR, Schulz R. Activity restriction and prior relationship history as contributors to mental health outcomes among middle-aged and older spousal caregivers. Health Psychology. 1998;17(2):152–162. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]