Abstract

The Z mutant of α1-antitrypsin (Glu342Lys) causes a domain-swap and the formation of intrahepatic polymers that aggregate as inclusions and predispose the homozygote to cirrhosis. We have identified an allosteric cavity that is distinct from the interface involved in polymerisation for rational structure-based drug design to block polymer formation. Virtual ligand screening was performed on 1.2 million small molecules and 6 compounds were identified that reduced polymer formation in vitro. Modelling the effects of ligand binding on the cavity and re-screening the library identified an additional 10 compounds that completely blocked polymerisation. The best antagonists were effective at ratios of compound to Z α1-antitrypsin of 2.5:1 and reduced the intracellular accumulation of Z α1-antitrypsin by 70% in a cell model of disease. Identifying small molecules provides a novel therapy for the treatment of liver disease associated with the Z allele of α1-antitrypsin.

Keywords: hepatic inclusions, cirrhosis, serpinopathies, drug design, serpins

Introduction

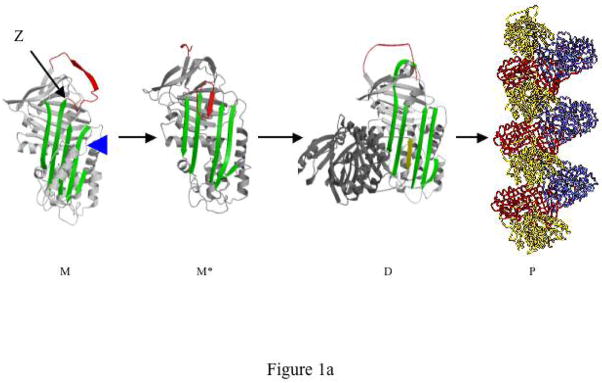

α1-Antitrypsin is synthesised in the liver and released into the plasma where it is the most abundant circulating protease inhibitor. Most individuals carry the normal M allele of α1-antitrypsin but 4% of the Northern European population are heterozygous for the severe Z deficiency variant (Glu342Lys). The Z mutation perturbs the relationship between β-sheet A and the exposed mobile reactive loop that binds to the target proteinase (Fig. 1)1. The resulting unstable intermediates2–4 then link sequentially to form loop-sheet polymers in which the reactive centre loop of one α1-antitrypsin molecule inserts as strand 4 of β-sheet A of another2,3,5–7. It is this accumulation of polymers within the endoplasmic reticulum of hepatocytes that underlies the Periodic acid Schiff positive inclusions that are the hallmark of Z α1-antitrypsin deficiency5,8–10. These inclusions predispose the Z α1-antitrypsin homozygote to hepatitis11, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma12. The resulting lack of circulating α1-antitrypsin allows uncontrolled proteolytic digestion within the lung and early onset panlobular emphysema (see reference13 for review).

Figure 1.

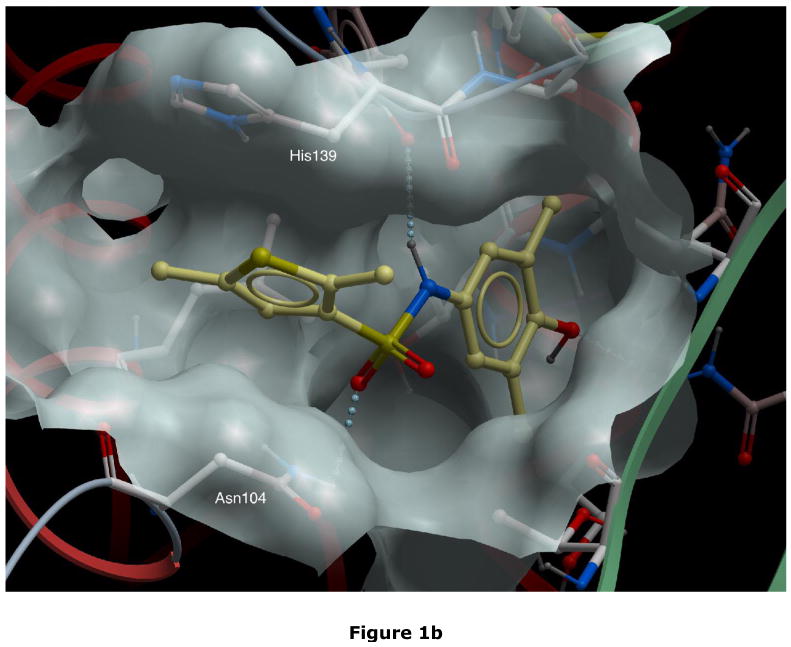

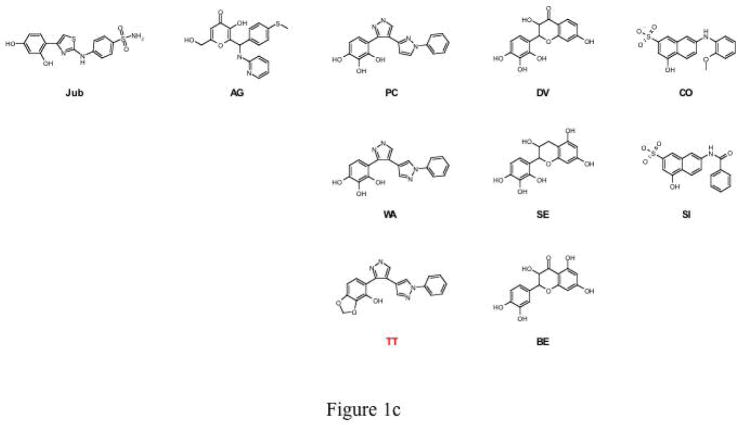

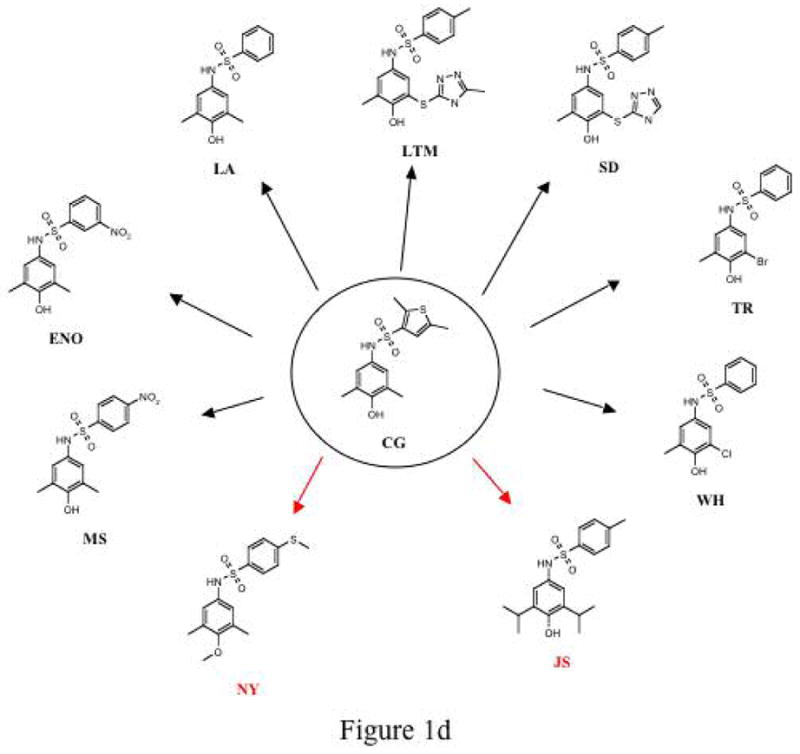

Rational drug design to prevent the polymerisation of α1-antitrypsin. Fig. 1a. Pathway of the polymerisation of α1-antitrypsin. The Z mutation of α1-antitrypsin (Glu342Lys at P17; arrowed) perturbs the structure of β-sheet A (green) and the mobile reactive centre loop (red) to form the intermediate M*. The patent β-sheet A can then accept the loop of another molecule (as strand 4) to form a dimer (D) which then extends into polymers (P)2–4. It is these polymers that accumulate within hepatocytes to cause liver disease5. The position of the lateral hydrophobic pocket that is the target of rational drug design is shown with a blue arrowhead. Note the change in conformation in this region of the molecule as it forms M* and then dimers and polymers. Fig. 1b. The predicted binding pose of CG to the lateral hydrophobic cavity with Asn104 in an alternate conformation. The residues that most effect the dimensions of the pocket, Asn104 and His139, are highlighted. Fig. 1c. The parent compounds Jub, AG, PC, DV and CO and their analogues that also blocked polymerisation. Compound TT (red) was designed as a control that did not block polymer formation. Fig. 1d. The parent compound CG and its analogues. Compounds labelled in red (NY and JS) are designed not to block polymerisation.

α1-Antitrypsin is the archetypal member of the serine proteinase inhibitor or serpin superfamily. The process of polymer formation is now recognised to underlie diseases associated with other members of this family. For example mutants of antithrombin14,15, C1-inhibitor16,17 and α1-antichymotrypsin3,18 cause the protein to form polymers that are retained within the liver thereby causing a plasma deficiency that results in thrombosis, angioedema and emphysema respectively. Perhaps most striking is our description of mutants of a neurone-specific protein, neuroserpin, that polymerise to cause a novel inclusion body dementia that we have called familial encephalopathy with neuroserpin inclusion bodies or FENIB19,20. In view of the common mechanism that underlies these disorders we have grouped them together as a new class of disease, the ‘serpinopathies’21.

The only curative treatment currently available for the cirrhosis associated with α1-antitrypsin deficiency is liver transplantation. Thus it is essential to develop effective strategies to block polymerisation in order to treat the associated disease22. Previous approaches have focused on chemical chaperones23,24 that stabilise the mutant protein and reactive loop peptides that can bind as strand 4 of β-sheet A of Z α1-antitrypsin and so prevent the acceptance of an exogeneous reactive loop4,25. However neither strategy has yet been proven to be a viable therapeutic option in man26. Finding a small drug that can bind to α1-antitrypsin and prevent polymerisation in vitro and in vivo is particularly challenging. Ideally, this small molecule should bind to a region of the protein that is distinct from the strand 4 position of β-sheet A for although this is the binding site of exogenous reactive loop peptides to form polymers (Fig. 1a), it is also critical for the inhibitory function of α1-antitrypsin27.

A lateral hydrophobic pocket was identified in crystal structures of α1-antitrypsin1,28. This pocket is lined by strand 2 of β-sheet A and β-helices D and E (Fig. 1a). It is patent in the native protein but is occupied as β-sheet A accepts an exogenous reactive loop peptide during polymer formation1. The potential utility of the cavity as a target for rational drug design was demonstrated by the introduction of the ‘cavity-filling’ mutation Thr114Phe29. This mutation retarded polymer formation and increased the secretion of Z α1-antitrypsin from a Xenopus oocyte expression system29. However it is unknown whether this pocket could be targeted with sufficient affinity by a small molecule ligand. We report here the use of structure based drug discovery to identify a lead small molecule antagonist that can bind to the lateral hydrophobic pocket of Z α1-antitrypsin and block polymerisation in vitro and in a cell model of disease.

Results and Discussion

In silico screening to identify small molecules that antagonise the polymerisation of α1-antitrypsin

The ICM PocketFinder analysis tool30 was used to determine if either of the two high resolution structures of native α1-antitrypsin (PDB codes: 1QLP1 and 1HP728) would be suitable for virtual screening. The lateral hydrophobic cavity was identified as being ‘druggable’ in both structures but the cavity in structure 1QLP was better suited to binding small molecules. Virtual screening with the ICM software suite (Molsoft L.L.C.) against a non-redundant library of approximately 1.2 million commercial drug-like compounds was performed on the original crystallographic coordinates (PDB 1QLP) of the lateral hydrophobic pocket. However, compounds nominated from screening the deposited structure were not effective in preventing the polymerisation of Z α1-antitrypsin. As a consequence side chain simulation analysis (see ‘Experimental section’) was performed in order to identify the most flexible residues that line the cavity. Asn104 was highlighted by computational analysis as the most flexible residue. Visual inspection confirmed that this residue had the most significant effects on the dimensions and drugability of the cavity. An alternate conformation for this target site was generated by modelling low energy conformations for Asn104 through internal coordinate Monte Carlo side chain simulations31. The resulting conformation differs from the PDB structure only in the position of the Asn104 side chain by 0.5Å root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) after optimal superposition.

Virtual screening with the non-redundant library of 1.2 million commercial drug-like compounds was then performed with this alternate conformation of α1-antitrypsin. Sixty-eight compounds from the initial screen of 1.2 million small molecules were selected for further characterisation in vitro.

Assessment of the effect of small molecules on polymerisation, structure and function of α1-antitrypsin

Most compounds nominated from the screen had no or negligible effects on polymerisation (Fig. 2) while some even accelerated polymer formation. Four compounds (denoted Jub, AG, CO and DV; Fig. 1c) reduced the rate of polymerisation, one compound (PC; Fig. 1c) prevented the formation of higher molecular mass polymers and one compound (CG; Fig. 1d) completely blocked polymerisation (Figs. 2a and 2b). CG (see Fig. 1b for predicted binding pose) completely blocked the polymerisation of Z α1-antitrypsin at 50μM (25-fold molar excess) but was still effective at reducing polymerisation at 20μM (10-fold molar excess) (Fig. 2c). PC effectively reduced polymerisation at 10μM (5-fold molar excess) although a dimer band was still present (Fig. 2d). CG and PC, and indeed all the compounds that reduced polymerisation of Z α1-antitrypsin caused an anodal band shift in the residual monomeric protein when analysed by non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Further analysis demonstrated that CG induced the band shift of Z α1-antitrypsin between 8 and 18 hours when incubated in 100-fold molar excess (data not shown). The band shift was not due to cleavage of the protein (as assessed by N-terminal sequencing analysis), denaturation (as assessed by far UV circular dichroism) or covalent linkage as CG is chemically inert. However the Z α1-antitrypsin:CG complex was remarkably stable with a melting temperature in excess of 100°C (which compares to a Tm of 54.1°C in 3.7% v/v ethanol in the absence of CG) and was inactive as a proteinase inhibitor. It was not possible to determine a value for the Kd between CG and Z α1-antitrypsin using intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence. We therefore used dialysis to determine whether this interaction with the compound led to an irreversible transition. Z α1-antitrypsin was incubated with a 100-fold molar excess of CG at 37°C for 3 days and then extensively dialysed (3×1 litre) against PBS. The anodal band shift remained after dialysis (Fig. 3a) with the complex being resistant to polymerisation when heated at 0.1mg/ml for a further 3 hours at 60°C. Thus the interaction between CG and Z α1-antitrypsin, or the conformational transition that ensues, was resistant to dialysis leading to a permanent non-polymerisable state.

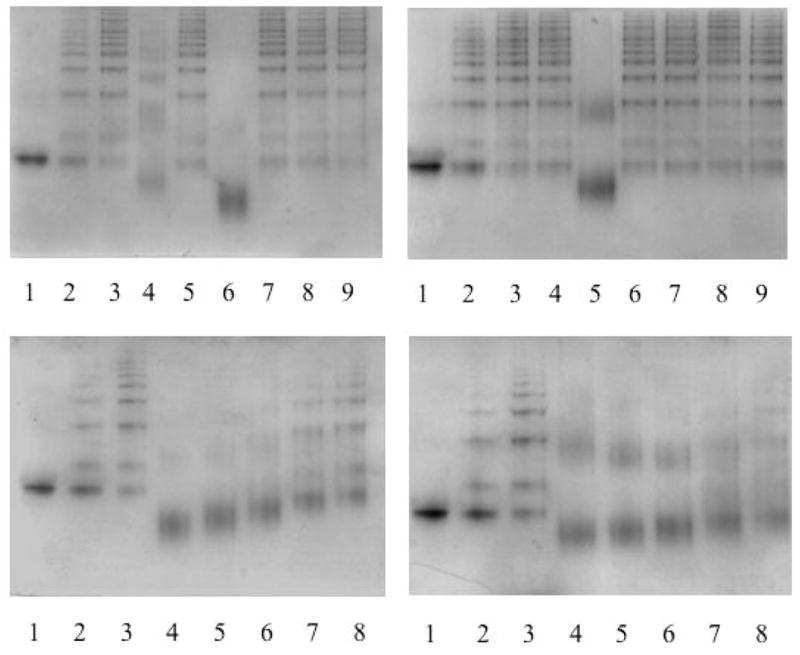

Figure 2.

7.5 % (w/v) non-denaturing PAGE to assess the effect of compounds identified in silico on the polymerisation of Z α1-antitrypsin. Each lane contains 2μg of protein. Fig. 2a (top left). Lane 1, monomeric Z α1-antitrypsin; lane 2, Z α1-antitrypsin heated at 0.1mg/ml and 41°C for 7 days; lane 3, Z α1-antitrypsin heated at 0.1mg/ml and 41°C for 7 days in the presence of 4.75% (v/v) DMSO; lanes 4–9, Z α1-antitrypsin heated at 0.1mg/ml and 41°C for 7 days with 100- fold molar excess of AG, BS, CG, EC, FP and GP respectively, all with a final concentration of 4.75% (v/v) DMSO. Fig. 2b (top right). Lane 1, monomeric Z α1-antitrypsin; lane 2, Z α1-antitrypsin heated at 0.1mg/ml and 41°C for 7 days; lane 3, Z α1-antitrypsin heated at 0.1mg/ml and 41°C for 7 days in the presence of 4.75% (v/v) DMSO; lanes 4–9, Z α1-antitrypsin heated at 0.1mg/ml and 41°C for 7 days with 100-fold molar excess of OC, PC, RS, SK, TCR and UX respectively, all with a final concentration of 4.75% (v/v) DMSO. Fig. 2c (bottom left). 7.5 % (w/v) non-denaturing PAGE to assess the effect of decreasing concentrations of CG on the polymerisation of Z α1-antitrypsin. Lane 1, monomeric Z α1-antitrypsin; lane 2, Z α1-antitrypsin heated at 0.1mg/ml and 41°C for 3 days; lane 3, Z α1-antitrypsin heated at 0.1mg/ml and 41°C for 3 days in the presence of 4.75% (v/v) DMSO; lanes 4–8, Z α1-antitrypsin heated at 0.1mg/ml and 41°C for 3 days with 200μM, 100μM, 50μM, 20μM and 10μM CG respectively, all with a final concentration of 4.75% (v/v) DMSO. Fig. 2d (bottom right). 7.5 % (w/v) non-denaturing PAGE to assess the effect of decreasing concentrations of PC on the polymerisation of Z α1-antitrypsin. Lane 1, monomeric Z α1-antitrypsin; lane 2, Z α1-antitrypsin heated at 0.1mg/ml and 41°C for 3 days; lane 3, Z α1-antitrypsin heated at 0.1mg/ml and 41°C for 3 days in the presence of 4.75% (v/v) DMSO; lanes 4–8, Z α1-antitrypsin heated at 0.1mg/ml and 41°C for 3 days with 200μM, 100μM, 50μM, 20μM and 10μM PC respectively, all with a final concentration of 4.75% (v/v) DMSO.

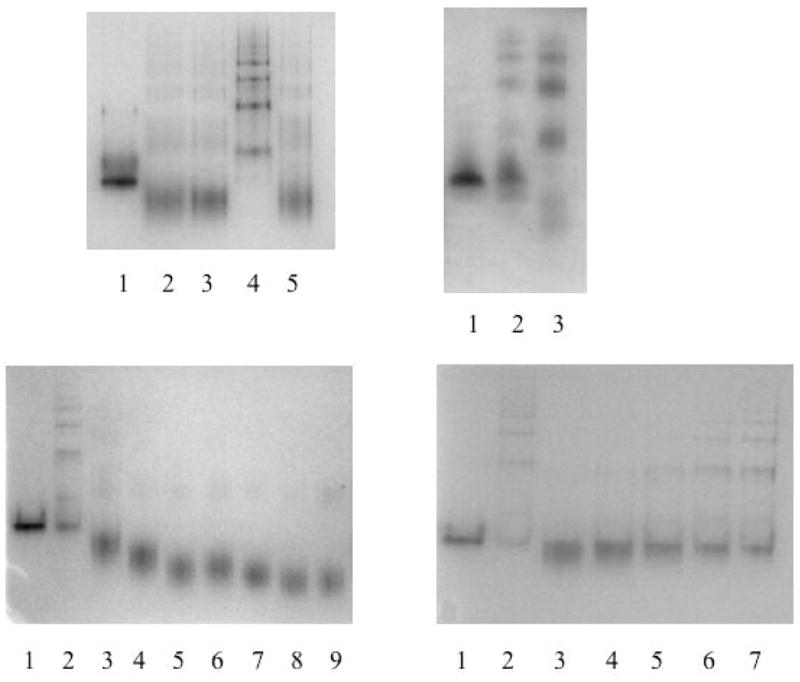

Figure 3.

The binding of CG and its analogues to Z α1-antitrypsin and other serpins. Fig. 3a (top left). 7.5 % (w/v) non-denaturing PAGE with each lane containing 2μg protein. The interaction between Z α1-antitrypsin and CG leads to an irreversible transition. Lane 1, Z α 1-antitrypsin; lane 2, Z α1-antitrypsin incubated with CG at 37°C for 3 days; lane 3, Z α1-antitrypsin incubated with CG at 37°C for 3 days and then dialysed in 3x1l PBS; lane 4, Z α 1-antitrypsin heated at 0.1mg/ml and 60°C for 3 hours; lane 5, Z α1-antitrypsin incubated with CG at 37°C for 3 days, dialysed in 3x1l PBS and then heated at 0.1mg/ml and 60°C for 3 hours. Fig. 3b (top right). CG does not inhibit the polymerisation of α1-antichymotrypsin. 7.5 % (w/v) non-denaturing PAGE with each lane containing 2μg protein. Lane 1, α1-antichymotrypsin; lane 2, α1-antichymotrypsin heated at 0.1mg/ml and 45°C for 3 days in 3.7% (v/v) ethanol; lane 3, α1-antichymotrypsin incubated at 0.1mg/ml and 45°C for 3 days with CG in 3.7% (v/v) ethanol. Fig. 3c (bottom left). Effect of the analogues of CG on the polymerisation of Z α1-antitrypsin. Lane 1, Z α1-antitrypsin; lane 2, Z α1-antitrypsin heated at 0.1mg/ml and 37°C for 3 days in 3.7% (v/v) ethanol; lanes 3–9, Z α1-antitrypsin heated at 0.1mg/ml and 37°C for 3 days in 100- fold molar excess of CG, LA, ENO, MS, SD, TR and WH respectively, all with a final concentration of 3.7% (v/v) ethanol. Fig. 3d (bottom right). Effect of the LTM on the polymerisation of Z α1-antitrypsin. Lane 1, Z α1-antitrypsin; lane 2 Z α1-antitrypsin heated at 0.1mg/ml and 37°C for 3 days in 3.7% (v/v) ethanol; lanes 3–7, Z α1-antitrypsin heated at 0.1mg/ml and 37°C for 3 days in 10μM, 7.5μM, 5μM, 2.5μM and 1μM of LTM respectively, all with a final concentration of 3.7% (v/v) ethanol.

Mass spectrometry was used to assess the binding of CG to Z α1-antitrypsin. Identical digest products were obtained for both Z α1-antitrypsin and the Z α1-antitrypsin:CG complex. There was 70% coverage of the protein sequence but CG was not associated with any of the identified fragments.

Assessment of the effect of small molecules on polymerisation of other member of the serpin superfamily

Members of the serine proteinase inhibitor or serpin superfamily are structurally homologous, but the lateral hydrophobic pocket is not present in antithrombin or α1-antichymotrypsin1. There is currently no crystal structure of native neuroserpin. CG caused an anodal migration of α1-antichymotrypsin, antithrombin and wildtype and mutant Syracuse (Ser49Pro)32 neuroserpin but did not prevent their polymerisation (Fig. 3b and data not shown).

In silico screening following modelling of ligand induced changes in the conformation of Z α1-antitrypsin

Even small ligand induced changes in the conformation of Z α1-antitrypsin can have major effects on binding affinity. These ligand induced changes were modelled for the best compounds, CG and PC, in order to target more relevant induced-fit pocket conformations for the second round of virtual screening. This was achieved by performing internal coordinate Monte Carlo side chain simulations in the presence of the ligand in its predicted binding pose31. The major difference between the resulting two conformations, selected for follow-up virtual screening, and the PDB structure are in the position of Asn104 and His139. Comparison of these conformations to the PDB structure show an RMSD of 0.77 and 1.0Å, respectively.

Virtual screening with the non-redundant library of 1.2 million commercial drug-like compounds against these newly derived conformations identified a further 19 compounds for in vitro testing. Ten of these compounds were structurally similar to the original active compounds, CG or PC. The PC analogue WA (Fig. 1c) had a similar effect to PC by allowing only the formation of dimers. BE and SE reduced polymer formation to the same extent as the parent molecule DV but the analogues of CO (e.g. SI) had little effect (Fig. 1c). The most potent blockers of polymerisation were analogues of CG: LA, ENO, MS, SD, TR, WH and LTM (Figs. 1d and 3c). LA completely blocked the polymerisation of Z α1-antitrypsin at 50μM (25-fold excess) and reduced polymerisation at 10μM (5-fold excess). WA, ENO, MS, SD, TR, WH and LTM completely blocked polymerisation at 10μM (5-fold excess) whilst WA and WH still had a modest effect at 7.5μM. SD, TR and LTM were effective at concentrations as low as 5μM (2.5-fold excess) (Fig. 3d and data not shown). Like the parent compounds, all analogues that blocked polymerisation caused an anodal band shift on non-denaturing PAGE and inactivated Z α1-antitrypsin as a proteinase inhibitor. The specificity of the compounds to the lateral hydrophobic pocket was assessed by selecting close analogues predicted not to bind the lateral hydrophobic pocket. None of these compounds (TT, NY and JS; Fig. 1c and 1d) had any demonstrable effect on the polymerisation of Z α1-antitrypsin.

Characterisation of the effect of the compounds in a cell model of Z α1-antitrypsin deficiency

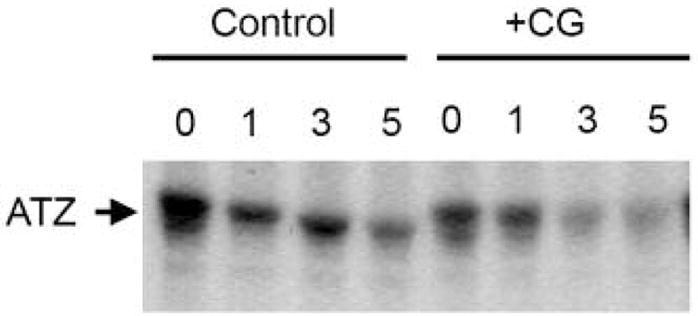

The effect of the small molecules on the intracellular fate of Z α1-antitrypsin was then assessed in murine hepatoma cells, Hepa1a. CG reduced the intracellular retention of Z α1-antitrypsin by 70% (Fig. 4) in keeping with an accelerated rate of clearance when compared to control cells. The majority of Z α1-antitrypsin was cleared 1–3 hours after pulse-labeling compared to 5 hours for Z α1-antitrypsin that was not treated with CG. There was no change in the electrophoretic mobility of Z α1-antitrypsin when isolated from cells incubated with CG. No increase in the secretion of Z α1-antitrypsin was detected (data not shown). Neither NY nor LTM accelerated the degradation nor increased secretion of Z α1-antitrypsin in this cell model of disease.

Figure 4.

The effect of CG on the secretion of Z α1-antitrypsin. Hepa1a cells were transiently transfected with Z α1-antitrypsin in the presence or absence of CG. Lanes 1–4, Z α1-antitrypsin radiolabeled with [35S]methionine and chased up to 5 hours. Immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrate that the half-life of the Z variant is between 3–5 hours. Lanes 5–8, transfected Hepa1a cells were treated with 100μM CG for 16h prior to the pulse-chase experiment. Z α1-antitrypsin was radiolabeled with [35S]methionine in the presence of CG and chased up to 5 hours. Glycan trimming of Z α1-antitrypsin was not detected in association with an increased rate of intracellular clearance.

Polymers of Z α1-antitrypsin are retained within hepatocytes where they aggregate to form the inclusions that underlie the associated liver disease. The pathways by which polymers are handled within hepatocytes are now being elucidated. Trimming of asparagine linked oligosaccharides target Z α1-antitrypsin polymers into an efficient non-proteosomal disposal pathway within hepatocytes33–35. However, the proteosome has an important role in metabolising Z α1-antitrypsin in some hepatic36 and extra-hepatic37,38 mammalian cell lines. Moreover, there is increasing evidence that the retained Z α1-antitrypsin stimulates an autophagic response within the hepatocyte39–41. Our data demonstrate that at least one of the small molecules (CG) is able to increase the clearance of Z α1-antitrypsin in a cell model of disease. Further studies are required to define the disposal pathways that clear the Z α1-antitrypsin:CG complex. However the resulting Z α1-antitrypsin had a normal electrophoretic mobility when isolated from cells which implies that treatment with CG either ablated the trimming of asparagine-linked oligosaccharides or that molecules were more rapidly degraded in response to the accelerated rate at which oligosaccharides were modified, such that only the unmodified population remained. The latter conclusion is most likely correct as cleavage of the appendages is an obligatory step in the intracellular degradation process. In either case the accelerated clearance of mutant protein provides strong support for the likely success of these compounds (or their derivatives) in vivo. The ability of CG to target the mutant protein for degradation would reduce the protein overload and therefore attenuate the hepatic toxicity associated with the accumulation of polymers of Z α1-antitrypsin.

In-vitro selectivity of CG

The Molecular Libraries Screening Center Network (MLSCN) is a consortium of academic laboratories responsible for screening compound libraries against cell and cell-free in-vitro assays (http://grants1.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-RM-04-017.html.). As of June 2007, the compound CG (PubChem ID: MLS000521559) has tested negative (between 5 to 10 μM) in all 30 MLSCN screens, including 9 cell (PubChem Assay ID (AID): 598, 602, 620, 648, 710, 719, 729, 731, 736) and 21 cell-free (AID: 583, 568, 618, 619, 629, 631, 632, 633, 639, 640, 687, 693, 690, 696, 697, 701, 704, 702, 717, 720, 722) assays. The targets in these assays include traditional enzyme active sites (e.g. protein kinase, tyrosine phosphatase and matrix metallo-proteinase), protein-protein and protein-RNA binding sites, as well as cytotoxic and reporter-based cell screens. This wide panel of screens shows that CG is not a promiscuous compound and is therefore less likely to have unwanted off-target effects.

Conclusion

Taken together our data demonstrate the successful use of structure-based drug design to target a cavity that is distinct from the interface involved in polymerisation of mutant α1-antitrypsin. The discovered compounds are effective at reducing the polymerisation of mutant Z α1-antitrypsin in vitro while the lead compound CG reduces aggregates of Z α1-antitrypsin in a cell model of disease. CG is highly selective as it is inactive in a diverse range of 29 cell-based and cell-free in-vitro assays. Our strategy represents a novel and highly effective approach to the treatment of the liver disease associated with homozygosity of the Z allele of α1-antitrypsin.

Experimental section

In silico screening to identify small molecules that antagonise the polymerisation of α1-antitrypsin

Virtual screening was performed with the original crystallographic coordinates of the lateral hydrophobic pocket of 1QLP1 against a non-redundant library of approximately 1.2 million commercial drug-like compounds from 10 vendors: Asinex (Russia), BioNet (UK), Chembridge (USA), Chemical Diversity (USA), IBS (Russia), Maybridge (USA), Sigma-Aldrich (USA), Specs (Netherlands), Tripos (USA) and TimTec (Russia). The screen was repeated following an assessment of the flexibility of the side chains of the pocket and modelling the effect of ligand induced changes. In each case the virtual screening results were ranked by their ICM-score and the following conditions were imposed to nominate compounds for biological testing: (i) a permissive cut off score that resulted in only the top 1% (approximately 400) of top scoring compounds being retained, (ii) the location of the ligand in the pocket and (iii) the ligand should make at least one hydrogen bond with the protein.

Side chain flexibility anaylsis

Analysis of the local flexibility around the lateral hydrophobic pocket was based on an ICM biased probability Monte Carlo simulation31 of the 17 side chains surrounding the pocket (N104, L110, Q105, H139, Q109, Q111, S140, L103, S56, L112, N116, L100, T114, T59, N186, I188 and Y138). Only the lowest energy representatives were selected for conformations closer than 15 degrees in side-chain torsion RMSD42. The RMSD of atoms with Boltzmann-weighted contributions from these filtered low energy conformations were then calculated. The side chain of Asn104 exhibited the maximal possible deviation (3.6Å).

Assessment of the effect of small molecules on polymerisation, structure and function of α1-antitrypsin

The lead compounds or analogues were solubilised to 2mg/ml in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) or 1mg/ml in 50% (v/v) ethanol before being diluted to 0.4mg/ml with PBS. α1-Antitrypsin was purified from the plasma of either PiM or PiZ homozygotes43 and the effect of compounds on polymerisation was assessed by incubation in 100-fold molar excess with 2μg of Z or M α1-antitrypsin (200μM compound to 2μM α1-antitrypsin). The final concentration of DMSO or ethanol was the same for each sample and the controls (4.75% (v/v) and 3.7% (v/v) respectively). Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy and thermal unfolding experiments were performed as detailed previously29. The effect of the compounds on the activity of α1-antitrypsin was assessed using an ELISA assay.

Mass spectrometry

The molecular mass of native Z α1-antitrypsin or Z α1-antitrypsin incubated with the small molecule was determined by MALDI. Assessment of binding of the small molecule to a domain of α1-antitrypsin was undertaken by precipitating native Z α1-antitrypsin or Z α1-antitrypsin incubated with the small molecule with acetone and then treating with cyanogen bromide and digesting with trypsin in 4M urea. This was performed with or without treatment with PNGase F to remove the glycans.

Effect of the compounds on other members of the serpin superfamily

Plasma antithrombin was from Dan Johnson, Dept. of Haematology, University of Cambridge, plasma α1-antichymotrypsin was from Sigma and wildtype neuroserpin and the Syracuse mutant of neuroserpin that causes FENIB (Ser49Pro) were purified as described previously32. These serpins were incubated at 0.1mg/ml in PBS at 37°C or 45°C for 3 or 7 days in the presence or absence of 200μM compound and 3.7% (v/v) ethanol. The effect on polymerisation was then assessed by 7.5% (w/v) non-denaturing PAGE.

Characterisation of the effect of the compounds in a cell model of Z α1-antitrypsin deficiency

The murine hepatoma cell line, Hepa1a was grown as monolayers in standard growth medium and split into 100-mm dishes at a density of 70% confluence. The following day cells were transfected with hATZ/pcDNA3.1 Zeo(+) (Z α1-antitrypsin subcloned into the unique EcoRI site of pcDNA3.1 Zeo (+)) using the Lipofectamine 2000 protocol. Twenty-four hours post-transfection the cells were collected and split at the same density into 60-mm dishes. The small molecules (CG, NY and LTM) were administered forty-eight hours post-transfection at a concentration of 100μM with the scientists being blind to the in vitro efficacy of the compounds that were being assessed. The cells were incubated with the small molecule for 16 hours and then subjected to methionine starvation in methionine-free medium supplemented with the small molecule for thirty minutes. [35S]methionine was added [0.075 mCi (1 Ci = 37 GBq) per 60-mm dish] during a twenty minute pulse followed by up to 5-hour chase in serum free DMEM (Gibco/BRL) containing 0.2mM unlabeled methionine with the small molecule. The cells were lysed with buffered Nonidet P-40 detergent at designed time points and immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and then detected by fluorography.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council (UK), the Wellcome Trust, Papworth NHS Trust and the NIH (5R01GM071872 and 1R01GM074832 to RA; 1R01DK064232 and 1R01DK075322 to RNS). MM is the recipient of an Alpha-1 Laurell Training Award (ALTA), RLP is a Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Fellow, BG is a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Fellow and SCLB is a Wellcome Trust Summer Student. We are grateful to Drs Sarah Maslen and Elaine Spencer, Department of Chemistry, University of Cambridge for assistance with mass spectrometry, Dr Charlotte Summers, Department of Medicine, University of Cambridge for the ELISA based activity assay and to Prof. Edwin Chilvers, Department of Medicine, University of Cambridge for helpful advice.

References

- 1.Elliott PR, Pei XY, Dafforn TR, Lomas DA. Topography of a 2.0Å structure of α1-antitrypsin reveals targets for rational drug design to prevent conformational disease. Protein Science. 2000;9:1274–1281. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.7.1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dafforn TR, Mahadeva R, Elliott PR, Sivasothy P, Lomas DA. A kinetic mechanism for the polymerisation of α1-antitrypsin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9548–9555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gooptu B, Hazes B, Chang W-SW, Dafforn TR, Carrell RW, et al. Inactive conformation of the serpin α1-antichymotrypsin indicates two stage insertion of the reactive loop; implications for inhibitory function and conformational disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 2000;97:67–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahadeva R, Dafforn TR, Carrell RW, Lomas DA. Six-mer peptide selectively anneals to a pathogenic serpin conformation and blocks polymerisation: implications for the prevention of Z α1-antitrypsin related cirrhosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:6771–6774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100722200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lomas DA, Evans DL, Finch JT, Carrell RW. The mechanism of Z α1-antitrypsin accumulation in the liver. Nature. 1992;357:605–607. doi: 10.1038/357605a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sivasothy P, Dafforn TR, Gettins PGW, Lomas DA. Pathogenic α1-antitrypsin polymers are formed by reactive loop-β-sheet A linkage. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33663–33668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004054200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Purkayastha P, Klemke JW, Lavender S, Oyola R, Cooperman BS, et al. α1-antitrypsin polymerisation: A fluorescence correlation spectroscopic study. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2642–2649. doi: 10.1021/bi048662e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu Y, Whitman I, Molmenti E, Moore K, Hippenmeyer P, et al. A lag in intracellular degradation of mutant α1-antitrypsin correlates with liver disease phenotype in homozygous PiZZ α1-antitrypsin deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9014–9018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.9014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janciauskiene S, Eriksson S, Callea F, Mallya M, Zhou A, et al. Differential detection of PAS-positive inclusions formed by the Z, Siiyama and Mmalton variants of α1-antitrypsin. Hepatology. 2004;40:1203–1210. doi: 10.1002/hep.20451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.An JK, Blomenkamp K, Lindblad D, Teckman JH. Quantitative isolation of alpha-l-antitrypsin mutant Z protein polymers from human and mouse livers and the effect of heat. Hepatology. 2005;41:160–167. doi: 10.1002/hep.20508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sveger T. Liver disease in alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency detected by screening of 200,000 infants. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:1316–1321. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197606102942404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eriksson S, Carlson J, Velez R. Risk of cirrhosis and primary liver cancer in alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:736–739. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198603203141202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lomas DA. The selective advantage of α1-antitrypsin deficiency. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1072–1077. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200511-1797PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruce D, Perry DJ, Borg J-Y, Carrell RW, Wardell MR. Thromboembolic disease due to thermolabile conformational changes of antithrombin Rouen VI (187 AsnØAsp) J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2265–2274. doi: 10.1172/JCI117589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Picard V, Dautzenberg M-D, Villoutreix BO, Orliaguet G, Alhenc-Gelas M, et al. Antithrombin Phe229Leu: a new homozygous variant leading to spontaneous antithrombin polymerisation in vivo associated with severe childhood thrombosis. Blood. 2003;102:919–925. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aulak KS, Eldering E, Hack CE, Lubbers YPT, Harrison RA, et al. A hinge region mutation in C1-inhibitor (Ala436ØThr) results in nonsubstrate-like behavior and in polymerization of the molecule. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:18088–18094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eldering E, Verpy E, Roem D, Meo T, Tosi M. COOH-terminal substitutions in the serpin C1 inhibitor that cause loop overinsertion and subsequent multimerization. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2579–2587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crowther DC, Serpell LC, Dafforn TR, Gooptu B, Lomas DA. Nucleation of α1-antichymotrypsin polymerisation. Biochemistry. 2002;42:2355–2363. doi: 10.1021/bi0259305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis RL, Shrimpton AE, Holohan PD, Bradshaw C, Feiglin D, et al. Familial dementia caused by polymerisation of mutant neuroserpin. Nature. 1999;401:376–379. doi: 10.1038/43894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis RL, Shrimpton AE, Carrell RW, Lomas DA, Gerhard L, et al. Association between conformational mutations in neuroserpin and onset and severity of dementia. Lancet. 2002;359:2242–2247. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09293-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lomas DA, Mahadeva R. Alpha-1-antitrypsin polymerisation and the serpinopathies: pathobiology and prospects for therapy. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1585–1590. doi: 10.1172/JCI16782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sidhar SK, Lomas DA, Carrell RW, Foreman RC. Mutations which impede loop/sheet polymerisation enhance the secretion of human α1-antitrypsin deficiency variants. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8393–8396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burrows JAJ, Willis LK, Perlmutter DH. Chemical chaperones mediate increased secretion of mutant α1-antitrypsin (α1-AT) Z: a potential pharmacologcial strategy for prevention of liver injury and emphysema. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1796–1801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devlin GL, Parfrey H, Tew DJ, Lomas DA, Bottomley SP. Prevention of polymerization of M and Z α1-antitrypsin (α1-AT) with Trimethylamine N-Oxide. Implications for the treatment of α1-AT deficiency. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24:727–732. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.6.4407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang YP, Mahadeva R, Chang WS, Shukla A, Dafforn TR, et al. Identification of a 4-mer Peptide Inhibitor that Effectively Blocks the Polymerization of Pathogenic Z α1-Antitrypsin. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:540–548. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0207OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teckman JH. Lack of effect of oral 4-phenylbutyrate on serum alpha-1-antitrypsin in patients with alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency: a preliminary study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39:34–37. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200407000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huntington JA, Read RJ, Carrell RW. Structure of a serpin-protease complex shows inhibition by deformation. Nature. 2000;407:923–926. doi: 10.1038/35038119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee C, Maeng J-S, Kocher J-P, Lee B, Yu M-H. Cavities of α1-antitrypsin that play structural and functional roles. Prot Sci. 2001;10:1446–1453. doi: 10.1110/ps.840101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parfrey H, Mahadeva R, Ravenhill N, Zhou A, Dafforn TR, et al. Targeting a surface cavity of α1-antitrypsin to prevent conformational disease. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33060–33066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.An J, Totrov M, Abagyan R. Pocketome via comprehensive identification and classification of ligand binding envelopes. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:752–761. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400159-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abagyan R, Totrov M. Biased probability Monte Carlo conformational searches and electrostatic calculations for peptides and proteins. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:983–1002. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belorgey D, Crowther DC, Mahadeva R, Lomas DA. Mutant neuroserpin (Ser49Pro) that causes the familial dementia FENIB is a poor proteinase inhibitor and readily forms polymers in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17367–17373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200680200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cabral CM, Choudhury P, Liu Y, Sifers RN. Processing by endoplasmic reticulum mannosidases partitions a secretion-impaired glycoprotein into distinct disposal pathways. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25015–25022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910172199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cabral CM, Liu Y, Moremen KW, Sifers RN. Organizational diversity among distinct glycoprotein ER-associated degradation programs. Molec Biol Cell. 2002;13:2639–2650. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-02-0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu Y, Swulius MT, Moremen KW, Sifers RN. Elucidation of the molecular logic by which misfolded α1-antitrypsin is preferentially selected for degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8229–8234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1430537100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teckman JH, Burrows J, Hidvegi T, Schmidt B, Hale PD, et al. The proteasome participates in degradation of mutant α1-antitrypsin Z in the endoplasmic reticulum of hepatoma-derived hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44865–44872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103703200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qu D, Teckman JH, Omura S, Perlmutter DH. Degradation of a mutant secretory protein, α1-antitrypsin Z, in the endoplasmic reticulum requires proteosome activity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22791–22795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Novoradovskaya N, Lee J, Yu Z-X, Ferrans VJ, Brantly M. Inhibition of intracellular degradation increases secretion of a mutant form of α1-antitrypsin associated with profound deficiency. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2693–2701. doi: 10.1172/JCI549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teckman JH, Perlmutter DH. Retention of mutant α1-antitrypsin Z in endoplasmic reticulum is associated with an autophagic response. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G961–G974. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.5.G961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perlmutter DH. Liver injury in α1-antitrypsin deficiency: an aggregated protein induces mitochondrial injury. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1579–1583. doi: 10.1172/JCI16787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kamimoto T, Shoji S, Hidvegi T, Mizushima N, Umebayashi K, et al. Intracellular inclusions containing mutant alpha1-antitrypsin Z are propagated in the absence of autophagic activity. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4467–4476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509409200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abagyan R, Argos P. Optimal protocol and trajectory visualization for conformational searches of peptides and proteins. J Mol Biol. 1992;225:519–532. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90936-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lomas DA, Evans DL, Stone SR, Chang W-SW, Carrell RW. Effect of the Z mutation on the physical and inhibitory properties of α1-antitrypsin. Biochemistry. 1993;32:500–508. doi: 10.1021/bi00053a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]