Abstract

Non-infectious uveitis is a predominantly T cell mediated autoimmune, intraocular inflammatory disease. To characterize the gene expression profile from patients with non-infectious uveitis, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from 50 patients with clinically characterized non-infectious uveitis syndrome. A pathway-specific cDNA microarray was used for gene expression profiling and real time PCR array for further confirmation. Sixty-seven inflammation and autoimmune associated genes were found differentially expressed in uveitis patients with twenty-eight of those genes being validated by real-time PCR. Several genes previously unknown for autoimmune uveitis, including IL-22, IL-19, IL-20 and IL-25/IL-17E, were found to be highly expressed among uveitis patients compared to the normal subjects with IL-22 expression highly variable among the patients. Furthermore, we show that IL-22 can affect primary human retinal pigment epithelial cells by decreasing total tissue resistance and inducing apoptosis possibly by decreasing phospho-Bad level. In addition, the microarray data identified a possible uveitis-associated gene expression pattern, showed distinct gene expression profiles in patients during periods of clinical activity and quiescence, and demonstrated similar expression patterns in related patients with similar clinical phenotypes. Our data provides the first evidence that a sub-set of IL-10 family genes are implicated in non-infectious uveitis and that IL-22 can affect human retinal pigment epithelial cells. The results may facilitate further understanding of the molecular mechanisms of autoimmune uveitis and other autoimmune originated inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: human, autoimmunity, non-infectious uveitis, microarray, peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Introduction

Intraocular inflammatory disease or uveitis is a major cause of visual handicap in the United States, causing an estimated >100, 000 new cases of ocular morbidity per year and 10% of the new cases of legal blindness (1). It has been generally accepted that non-infectious uveitis is an autoimmune disorder predominantly mediated by T helper cells (2, 3). Earlier studies on humans as well as in animal models demonstrated that Th1 mediated autoimmune responses play a pivotal role in this disease (4–6). Several autoantigens have been identified as potential triggers for autoimmune uveitis (7–9). However, the varied clinical appearance in humans and the varied response to immunosuppressive regimens suggest that multiple mechanisms may be involved. For example, less than a third of uveitis patients tested will have T cell responses to arrestin, or S-antigen, the most recognized autoantigen for uveitis in humans (10). In addition, susceptibility to the two most important antigens used to induce experimental animal uveitis, interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein (IRBP) and S-antigen, varies from species to species despite evolutionarily conserved structures (11) and documented T cell response from uveitis patients to IRBP has been scarce. Recent work has also indicated that, similar to multiple sclerosis (MS), Th17 cells may be one of key immune components that contribute to the molecular pathogenesis of autoimmune uveitis (12). To facilitate the understanding of the molecular mechanisms of autoimmune uveitis and other autoimmune diseases, we investigated the gene expression profile of autoimmune uveitis using cDNA microarray and real time PCR array on 50 clinically characterized uveitis patients. Our results identified a set of IL-10 family genes, including IL-22 that are highly expressed in uveitis patients when compared to that of normal subjects, but have not been previously implicated in non-infectious uveitis. An in vitro study demonstrated that IL-22 affected human primary retinal pigment epithelial cells by decreasing their total tissue resistance, a hall mark of tissue integrity of those retinal epithelial cells (13). Meantime, IL-22 induced apoptosis of cultured human primary retinal pigment epithelial cells which is associated with decreased phospho-Bad level. We also show that there exists a molecular pattern for gene expression among uveitis patients compared to normal controls.

Materials and Methods

Patients, normal controls and human fetal tissue

The research performed in this study followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and the NIH Institutional Review Board. Fifty-eight patients with well defined clinical diagnoses of non-infectious uveitic syndrome were enrolled into the National Eye Institute (NEI) after IRB approval (protocol #02-EI-0122). Patient consent was obtained prior to enrollment and the ocular status of the patients after enrollment was evaluated and recorded independently by ophthalmologists in the NEI Uveitis Clinic. Samples from 20 healthy donors as normal controls were obtained from the NIH Blood Bank (protocol #97-0134). Human fetal eyes of nominal gestation of 15 to 17 weeks were obtained from Advanced Bioscience Resources (Alameda, CA).

Cell culture on transwell filters

Primary cell cultures of human fetal retinal pigment epithelial (hfRPE) cells were prepared from human fetal eyes as described previously (13). Second passage cells were seeded in transwells (Corning Costar, 0.4km pores, polyester membranes). Media were changed every three days and the cultures were maintained for at least 3 weeks before experiments.

cDNA microarray analysis

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from patients or normal donors as described previously(14). Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, CA). RNA isolated from 20 healthy donors were pooled and served as normal control. Biotinylated probes were generated from 5 μg of total RNA from each RNA sample by incorporating biotinylated dUTP into synthesized cDNAs using a T7-polymerase linear amplification strategy. Probes were hybridized to a pathway-specific cDNA microarray chip (Inflammatory and autoimmune GEArray; SuperArray Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). Signals for specific binding were recorded by a CCD camera. A total of 51 microarray analyses were performed independently for all patient samples and one pooled normal sample. Gene expression profiling was analyzed using GEArray Suite software (SuperArray Inc., MD). Briefly, acquired digital images were aligned, computed for density, normalized based on negative controls and transformed into scores for gene expression based on an established algorithm (SupperArray Inc., MD). All scores for each gene in one array were then normalized on house-keeping genes, e.g, GAPDH and beta-2-microglobulin (B2M). The final scores of each of the genes of all arrays were then compared to those from a control array to obtain a ratio value. A 2-fold cut-off threshold was used to define if one gene is up-regulated or down-regulated, e.g., the expression of one gene from array X is equal or greater than 2-fold of that from control array is considered up-regulated gene while equal or less than 0.5-fold of the score from the same gene compared to the control array is considered down-regulated gene. The scatter plot and clustergram were acquired using the same software according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Real-time PCR analysis

Real-time PCR array analysis was performed to confirm microarray results. A total of 60 autoimmune and inflammatory disease related genes were examined for confirmation purposes by real-time PCR using a commercially available real-time PCR RT2 Profiler kit (SuperArray, MD). To correlate the clinical status of the uveitic condition to the gene expression profile, only samples from patients with clinically active disease were used for real-time PCR analysis. Active uveitis was defined as evidence of cells and flare in the anterior chamber of the eye or cells and haze in the posterior chamber of the eye. A total of 42 RNA samples from clinically active uveitis patients were pooled to compare to the pooled normal control sample. Two independent PCR array analyses were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 1 μg of each of the RNA samples from either uveitis patients or normal controls were reverse transcribed into cDNAs using a first strand cDNA RT kit (SuperArray, MD). Real-time PCR was performed using a 96-well format PCR array and an ABI 7500 real-time PCR unit (ABI, CA). Primers for all genes for real-time PCR confirmation of the microarray analysis had been pre-tested and confirmed by the manufacturer. Assay controls include positive and negative controls as well as 3 sets of house-keeping gene controls for normalization purposes. Analysis of real-time PCR results was performed following the manufacturer’s instructions (SuperArray Inc., MD). Data analysis is based on the ΔΔCt method with normalization of the raw data to housekeeping genes as described in the manufacturer’s manual. The detailed instruction for calculation and normalization can be found in the following website: www.superarray.com. A 2-fold cut-off threshold was used to define if one gene is up-regulated or down-regulated. To further confirm IL-22 expression results based on microarray and real-time PCR array data, a SYBR Green based qRT-PCR was used to analyze IL-22 expression between normal and uveitis patients. Briefly, RNA samples from 6 normal donors and 40 uveitis patients were tested for IL-22 gene expression using the qRT-PCR MasterMix from SuperArray Inc. following their Endpoint RT-PCR Manual (Gaithursburg, MD). Human GAPDH gene expression from the same RNA samples was also tested for normalization and quantification purposes. The results were expressed as the fold expression of IL-22 normalized on that of GAPDH. The IL-22 expression was considered not detectable if the ratio of IL-22 against GAPDH is smaller than 0.001. qRT-PCR primers for IL-22 and GAPDH were both from SuperArray Inc. and have been verified by the provider.

Western blot analysis

fRPE cells were cultured in the presence or absence of 50ng/ml of recombinant human IL-22 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) for 48 hours. Cells were then lysed in 100 μl of lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-Cl, 1% Triton X-100, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 50 mM glycerol-phosphate, 1 mM NaVO4 and 1X protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN)]. Complete cell lysis was achieved by immediately vortexing and then boiling in an equal amount of 2 X SDS protein loading buffer at 95°C for 5 minutes. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 3 min. Twenty microliter of each sample was loaded into a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel with a 4% stacking gel. For immunoblotting, primary antibody of anti-phospho-Bad was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Anti-β-actin antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA).

Resistance and apoptosis assay for RPE cells

The RPE monolayers on inserts with total tissue resistance (TER) above 100 Ω·cm2 were cultured with either RPE culturing media alone or in the presence of 50 ng/ml of human recombinant IL-22 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ). After 72 hours of stimulation with IL-22 of RPE monolayers on inserts, TER was measured using EVOM (WPI, FL). Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.; statistical significance (Student’s t test, two-tail) was accepted as p<0.05. For apoptosis analysis, experimental cells from the same experiments as described above were stained by Annexin (BD Bioscience, CA) after 72 hours culturing. Samples were acquired by a FACSCalibre flow cytometor and analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar, San Jose, CA).

Results

Differential gene expression among uveitis patients and normal subjects

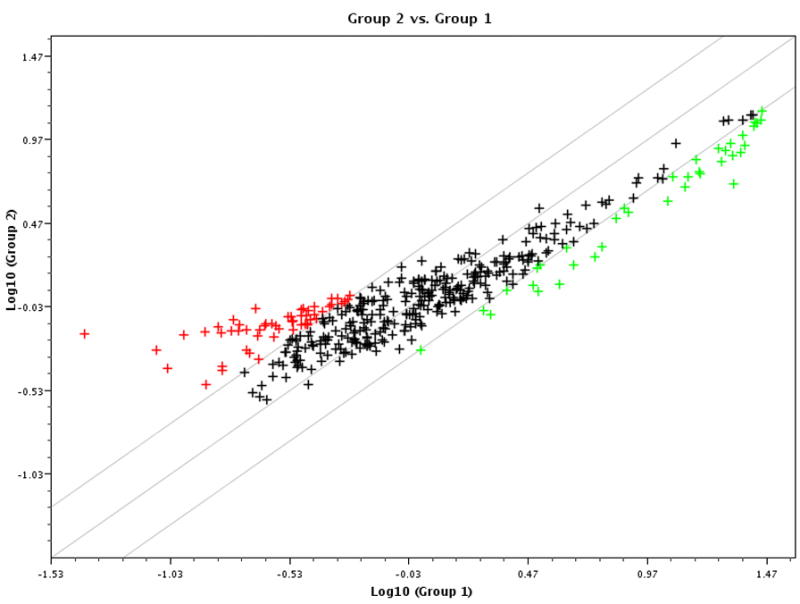

A total of 58 patients were enrolled into our microarray protocol. Table 1 summarizes the clinical information of all patients who were enrolled. The diagnoses, gender, race and clinical manifestations of the enrolled patients represent what is typically seen in the Uveitis Clinic of the National Eye Institute. Eight RNA samples did not qualify for the microarray analysis after quality control test. To test the validity of our strategy to use pooled RNA samples from normal donors as reference RNA sample to compare to individual RNA samples from uveitis patients, we ran microarray on 9 RNA samples, 8 individual RNA samples from normal donors vs. the pooled RNA sample from the same donors. A side-by-side analysis showed that the data derived from the 8 individual donors vs. the pooled sample from normal donors are very similar. Based on statistical correlation analysis, the average p value of correlation of the microarray data between the pooled vs. the 8 individual RNA samples is 0.88 (0.86–0.91). In addition, Clustergram analysis also demonstrated that there was a great similarity of gene expression patterns among the 8 individual normal donors when compared to the pooled RNA sample from the same donors (data not shown). Therefore, a total of 51 RNA samples, 50 from patients and one reference RNA pooled from 20 healthy donors, were analyzed for microarray analysis. Despite the high heterogeneity of gene expression among patients and between patients and controls, there were clear differences in gene expression patterns comparing those from patients to those from the normal pooled control RNA. Figure 1 is a scatter plot analysis showing genes that were differentially expressed among uveitis patients when compared to the normal donors with red symbols representing up-regulated genes and green symbols representing down-regulated genes. When a 2-fold cut-off threshold was applied, there were a total of 67 genes (16.7%) that were differentially expressed among uveitis patients when compared to normal controls with 56 genes up-regulated and 11 genes down regulated among the 400 inflammatory and autoimmune diseases associated genes in this pathway-specific cDNA array chip. A complete list of differentially expressed genes (2-fold cut-off) from cDNA microarray results for uveitis is provided in Table 2.

Table 1.

Patient information

| Asian Pacific | Black, not Hispanic | Hispanic | White, not Hispanic | Others | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 1 | 11 | 2 | 18 | 0 | 32(55%) |

| Male | 2 | 5 | 1 | 17 | 1 | 26(45%) |

| Total | 3 | 16 | 3 | 35 | 1 | 58 |

| Mean Age=36.7 yrs. (Range 6–78 yrs) | ||||||

| Clinical Diagnosis | Enrollment | |||||

| Intermediate Uveitis | 13 | |||||

| Behcet’s | 7 | |||||

| Panuveitis | 6 | |||||

| Sarcoidosis | 5 | |||||

| VKH | 5 | |||||

| Anterior Uveitis | 4 | |||||

| Retinal vasculitis | 3 | |||||

| Scleritis | 2 | |||||

| Others* | 13 | |||||

Include: multifocal choroiditis, serpiginous, etc.

Figure 1.

Scatter plot analysis of gene expression profiling on uveitis patients demonstrates differential gene expression. cDNA microarray analysis on 50 RNA samples from uveitis patients and 1 pooled sample from controls was performed. After normalization on house-keeping genes, e.g, GAPDH and beta-2-microglobulin (B2M), the final scores of each of the genes of all arrays were compared to those from the control array. The scatter plot was acquired as described in the Materials and Methods. The Y-axis represents log scores from uveitis patients (group 2) and the X-axis represents log scores from normal controls (group 1). Each symbol represents one gene with red-colored ones represent 2-fold higher expressed in uveitis patients (group 2), green-colored ones represent 2-fold lower expressed in uveitis patients and the black-colored ones represent within 2-fold cut-off threshold.

Table 2.

Gene list of differentially expressed genes in uveitis patients

| Position | UniGene | RefSeq No | Symbol | Description | Fold changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48 | Hs.10458 | NM_004590 | CCL16 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 16 | 16.6 |

| 171 | Hs.168132 | NM_172175 | IL15 | Interleukin 15 | 7.6 |

| 62 | Hs.251526 | NM_006273 | CCL7 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 7 | 5.9 |

| 112 | Hs.201300 | NM_006639 | CYSLTR1 | Cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 | 5.6 |

| 174 | Hs.41724 | NM_002190 | IL17 | Interleukin 17 (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated serine esterase 8) | 5.0 |

| 192 | Hs.73917 | NM_000589 | IL4 | Interleukin 4 | 5.0 |

| 63 | Hs. 271387 | NM_005623 | CCL8 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 8 | 4.6 |

| 172 | Hs.524117 | NM_002189 | IL15RA | Interleukin 15 receptor, alpha | 4.4 |

| 64 | Hs.301921 | NM_001295 | CCR1 | Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 1 | 4.4 |

| 80 | Hs.1634 | NM_001789 | CDC25A | Cell division cycle 25A | 4.1 |

| 222 | Hs.498997 | NM_014387 | LAT | Linker for activation of T cells | 3.8 |

| 252 | Hs.153629 | NM_005919 | MEF2B | MADS box transcription enhancer factor 2, polypeptide B (myocyte enhancer factor 2B) | 3.4 |

| 96 | Hs.2233 | NM_000759 | CSF3 | Colony stimulating factor 3 (granulocyte) | 3.4 |

| 239 | Hs.531754 | NM_145185 | MAP2K7 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 | 3.3 |

| 185 | Hs.272373 | NM_018724 | IL20 | Interleukin 20 | 3.0 |

| 368 | Hs.75516 | NM_003331 | TYK2 | Tyrosine kinase 2 | 2.9 |

| 237 | Hs.134859 | NM_005360 | MAF | V-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog (avian) | 2.8 |

| 89 | Hs.172928 | NM_000088 | COL1A1 | Collagen, type I, alpha 1 | 2.8 |

| 157 | Hs.43505 | NM_003639 | IKBKG | Inhibitor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells, kinase gamma | 2.7 |

| 254 | Hs.497723 | AF067420 | MGC27165 | Hypothetical protein MGC27165 | 2.7 |

| 158 | Hs.193717 | NM_000572 | IL10 | Interleukin 10 | 2.7 |

| 255 | Hs.126714 | NM_000246 | CIITA | Class II, major histocompatibility complex, transactivator | 2.7 |

| 127 | Hs.513470 | NM_032815 | NFATC2IP | Nuclear factor of activated T-cells, cytoplasrnic, calcineurin-dependent 2 interacting prot | 2.7 |

| 253 | Hs.314327 | NM_005920 | MEF2D | MADS box transcription enhancer factor 2, polypeptide D (myocyte enhancer factor 2D) | 2.6 |

| 139 | Hs.466828 | NM_019884 | GSK3A | Glycogen synthase kinase 3 alpha | 2.6 |

| 335 | Hs.517148 | NM_016397 | TH1L | TH1-ike (Drosophila) | 2.5 |

| 191 | Hs.694 | NM_000588 | IL3 | Interleukin 3 (colony-stimulating factor, multiple) | 2.5 |

| 160 | Hs.418291 | NM_000628 | IL10RB | Interleukin 10 receptor, beta | 2.5 |

| 236 | Hs.123119 | NM_005905 | SMAD9 | SMAD, mothers against DPP homolog 9 (Drosophila) | 2.5 |

| 187 | Hs.465645 | NM_019107 | C19orf10 | Chromosome 19 open reading frame 10 | 2.4 |

| 169 | Hs.336046 | NM_000640 | IL13RA2 | Interleukin 13 receptor, alpha 2 | 2.4 |

| 328 | Hs.133379 | NM_003238 | TGFB2 | Transforming growth factor, beta 2 | 2.4 |

| 223 | Hs.194236 | NM_000230 | LEP | Leptin (obesity homolog, mouse) | 2.4 |

| 141 | Hs.155111 | NM_032782 | HAVCR2 | Hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 2 | 2.4 |

| 313 | Hs.468426 | NM_144949 | SOCS5 | Suppressor of cytokine signaling 5 | 2.4 |

| 207 | Hs.436061 | NM_002198 | IRF1 | Interferon regulatory factor 1 | 2.3 |

| 170 | Hs.17987 | L15344 | TXLNA | Taxilin alpha | 2.3 |

| 7 | Hs.465709 | NM_000635 | RFX2 | Regulatory factor X, 2 (influences HLA class II expression) | 2.3 |

| 121 | Hs.86131 | NM_003824 | FADD | Fas (TNFRSF6)-associated via death domain | 2.3 |

| 334 | Hs.373550 | NM_003244 | TGIF | TGFB-induced factor (TALE family homeobox) | 2.3 |

| 67 | Hs.184926 | NM_005508 | CCR4 | Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 4 | 2.3 |

| 6 | Hs.73677 | NM_002918 | RFX1 | Regulatory factor X, 1 (influences HLA class II expression) | 2.3 |

| 256 | Hs.407995 | NM_002415 | MIF | Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (glycosylation-inhibiting factor) | 2.2 |

| 159 | Hs.504035 | NM_001558 | IL10RA | Interleukin 10 receptor, alpha | 2.2 |

| 109 | Hs.89714 | NM_002994 | CXCL5 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5 | 2.2 |

| 224 | Hs.36 | NM_000595 | LTA | Lymphotoxin alpha (TNF superfamily, member 1) | 2.2 |

| 153 | Hs.450230 | NM_000598 | IGFBP3 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 | 2.2 |

| 272 | Hs.9731 | NM_002503 | NFKBIB | Nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, beta | 2.1 |

| 106 | Hs.100431 | NM_006419 | CXCL13 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 13 (B-cell chemoattractant) | 2.1 |

| 156 | Hs.321045 | NM_014002 | IKBKE | Inhibitor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells, kinase epsilon | 2.1 |

| 251 | Hs.268675 | NM_005587 | MEF2A | MADS box transcription enhancer factor 2, polypeptide A (myocyte enhancer factor 2A) | 2.1 |

| 221 | Hs.409523 | NM_002286 | LAG3 | Lymphocyte-activation gene 3 | 2.1 |

| 143 | Hs.515126 | NM_000201 | ICAM1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (CD54), human rhinovirus receptor | 2.1 |

| 24 | Hs.437877 | NM_020547 | AMHR2 | Anti-Mullerian hormone receptor, type II | 2.1 |

| 47 | Hs.272493 | NM_004167 | CCL15 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 15 | 2.0 |

| 286 | Hs.1976 | NM_002608 | PDGFB | Platelet-derived growth factor beta polypeptide (simian sarcoma viral (v-sis) oncogene | 2.0 |

| 235 | Hs.465087 | NM_005904 | SMAD7 | SMAD, mothers against DPP homolog 7 (Drosophila) | 0.5 |

| 75 | Hs.2259 | NM_000073 | CD3G | CD3G antigen, gamma polypeptide (TiT3 complex) | 0.5 |

| 195 | Hs.68876 | NM_000564 | IL5RA | Interleukin 5 receptor, alpha | 0.5 |

| 263 | Hs.529244 | NM_003581 | NCK2 | NCK adaptor protein 2 | 0.5 |

| 325 | Hs.170009 | NM_003236 | TGFA | Transforming growth factor, alpha | 0.4 |

| 200 | Hs.624 | NM_000584 | IL8 | Interleukin 8 | 0.4 |

| 274 | Hs.2764 | NM_005007 | NFKBIL1 | Nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor-like 1 | 0.4 |

| 347 | Hs.211600 | NM_006290 | TNFAIP3 | Tumor necrosis factor, alpha-induced protein 3 | 0.4 |

| 242 | Hs.145605 | NM_006609 | MAP3K2 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 2 | 0.4 |

| 181 | Hs.126256 | NM_000576 | IL1B | Interleukin 1, beta | 0.4 |

| 215 | Hs.525704 | NM_002228 | JUN | V-jun sarcoma virus 17 oncogene homolog (avian) | 0.3 |

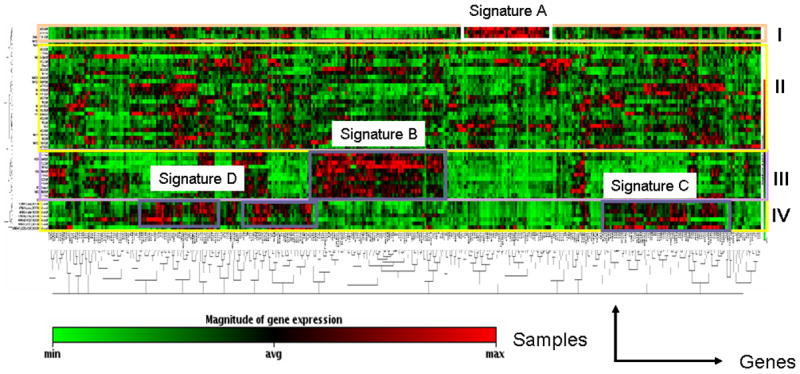

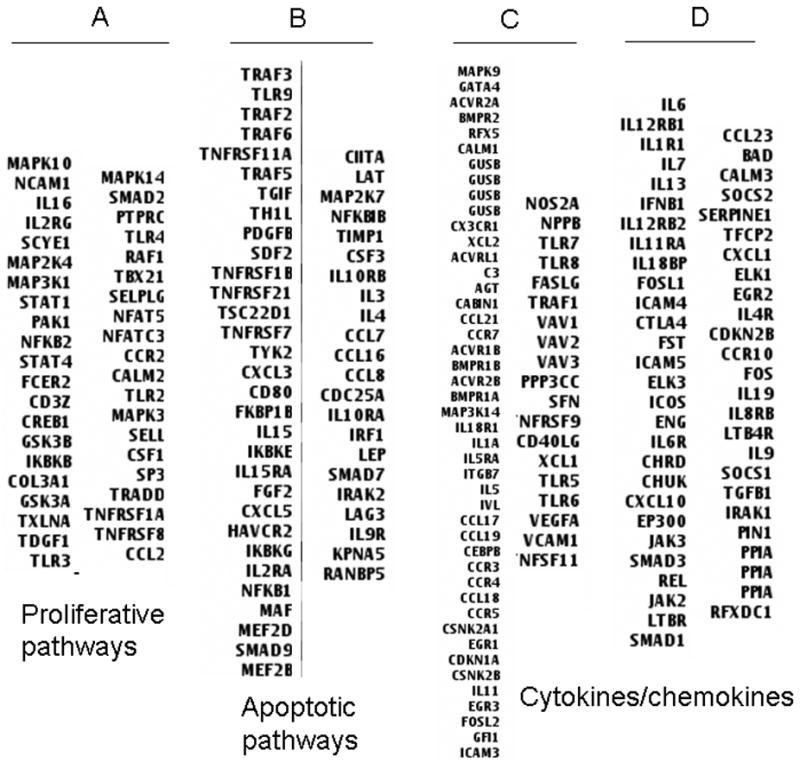

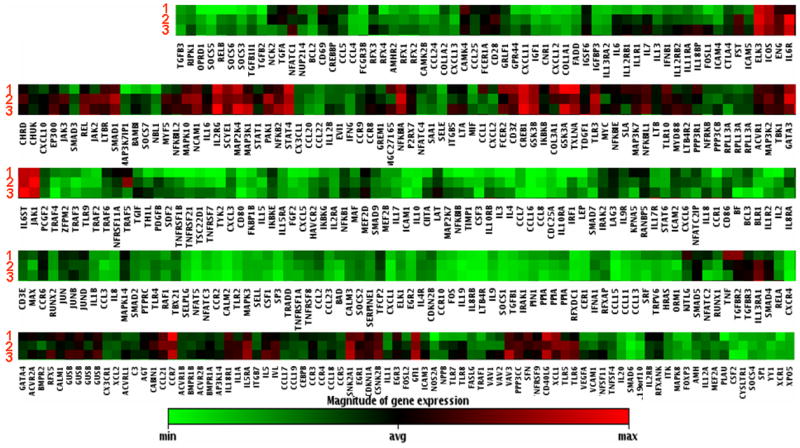

Gene expression profiling revealed 4 distinct sub-groups of uveitis patients

Non-infectious uveitis is considered a heterogeneous group of diseases comprised of a variety of clinical diagnoses and manifestations but all demonstrating intraocular inflammation. Based on this notion, we compared the differential gene expression patterns among uveitis patients using a density clustergram analysis with a red colored band representing higher and green representing lower gene expression after normalization to controls. There were clearly four distinct profiles (I, II, II and IV) based on their unique patterns of gene expression (Fig. 2). A detailed analysis of genes in those four profiles revealed 4 sets of genes with higher expression that define the differential gene expression profiling. A gene list for those 4 sets of genes, termed as signatures A, B, C and D is shown in Fig. 3. It is of interest that the genes within each set appeared functionally related. For example, genes in set A were more functionally associated with cell proliferative responses, genes in set B were more associated with cell apoptosis while most cytokine/chemokines were clustered in the set C and set D. One intriguing question is whether these molecular signatures reflect distinct molecular pathogeneses for autoimmune uveitis. However, our efforts to correlate clinical uveitic diagnoses with this differential gene expression profiling were not successful (see Discussion for details).

Figure 2.

Clustergram analysis of gene expression revealed 4 distinct gene expression profiles. cDNA microarray was performed as described above and clustergram analysis on microarray data was described in the Materials & Methods section. X-axis represents all genes listed in the cDNA microarray chip and Y-axis depicts gene expression profiles from all samples of uveitis patients normalized on normal controls. Each colored band represents expression of a single gene from one patient when compared to that from normal donors with higher expression in red and lower expression in green. Groups I, II, III and IV designate 4 sub-groups of gene expression profiles. Analysis of gene expression profiling among uveitis patients revealed 4 sets of genes designated as molecular signatures A, B, C and D that can be used to define the 4 sub-groups of gene expression profiles.

Figure 3.

List of the gene symbols for the four sets of molecular signatures A, B, C and D that define sub-groups of gene expression profiles. The four sets of genes were determined based on the results of clustergram analysis and expression levels of the clustered genes within each sub-group. The gene symbols were then extracted from the total gene list. The proposed functional association of genes within each set was also indicated.

Real-time PCR validated gene list provides evidence of involvement of previously uncharacterized genes in autoimmune uveitis

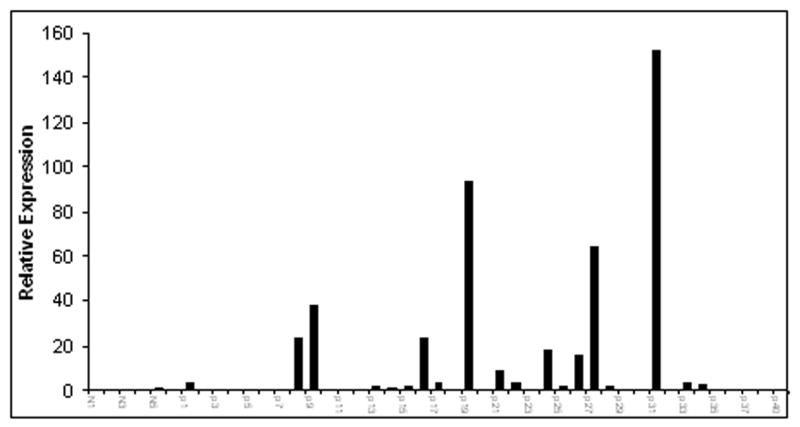

We then used quantitative real-time PCR to validate the microarray results. As shown in Table 3, real-time PCR analysis confirmed 18 up-regulated genes and 10 down-regulated genes in active uveitis patients as compared to those in normal controls (2-fold cut-off threshold). Some of the genes have been previously reported in association with autoimmune uveitis, e.g. CX3CR1, CCL19, CCL21, FasL, IFN-α, IL-4, -5, -6 and IL-8. However, several genes identified have not been previously associated with autoimmune uveitis including several cytokines from the IL-10 family and one cytokine from the IL-17 family. One set of IL-10 family genes including IL-19, IL-20 and IL-22 were of particular interest. IL-10 has been implicated to play a protective role in the mouse EAU model and is up regulated in human uveitis patients (6, 15, 16). However, IL-19, IL-20 and IL-22 have not been implicated in human uveitis. In addition, IL-25/IL-17E, which belongs to the IL-17 cytokine family, has also not been reported to be associated with autoimmune uveitis. Genes that have not been previously reported to be associated with autoimmune uveitis are highlighted in bold and italic in Table 3. To further confirm the microarray and real-time PCR array data, we tested IL-22 gene expression in 6 normal donors and 40 uveitis patients by using a SYBR Green based qRT-PCR strategy. As shown in Figure 4, five out of six normal donors had no detectable IL-22 transcript except 1 donor showed very low level of IL-22 expression by real-time PCR. However, 25 out of 40 (62.5%) uveitis patients tested positive for IL-22 expression with some patients demonstrated very high levels of IL-22 expression.

Table 3.

Differentially expressed genes in uveitis patients confirmed by Real-time PCR

| Up-regulated Genes | Down-regulated Genes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Symbol | Fold Up | RefSeq | Gene Symbol | Fold Down | RefSeq |

| IL22 | 16.5 | NM_020525 | CCL11 | −3.4 | NM_002986 |

| GDF5 | 7.6 | NM_000557 | IL8 | −3.7 | NM_000584 |

| IL19 | 7.0 | NM_013371 | CXCL14 | −5.2 | NM_004887 |

| CX3CR1 | 6.1 | NM_001337 | CXCL2 | −5.4 | NM_002089 |

| IL20 | 5.4 | NM_018724 | IL1B | −6.3 | NM_000576 |

| FASLG | 3.2 | NM_000639 | IL6 | −7.8 | NM_000600 |

| CCL21 | 3.0 | NM_002989 | CCL18 | −11.9 | NM_002988 |

| GDF10 | 2.9 | NM_004962 | CSF2 | −19.3 | NM_000758 |

| IL5 | 2.8 | NM_000879 | CCL20 | −21.7 | NM_004591 |

| CCL19 | 2.6 | NM_006274 | CCL7 | −24.0 | NM_006273 |

| CCR2 | 2.6 | NM_000648 | |||

| LTB | 2.5 | NM_002341 | |||

| TNFSF10 | 2.5 | NM_003810 | |||

| CXCL13 | 2.5 | NM_006419 | |||

| IFNA2 | 2.3 | NM_000605 | |||

| IL4 | 2.2 | NM_000589 | |||

| IL17E | 2.1 | NM_022789 | |||

| IL16 | 2.1 | NM_004513 | |||

Figure 4.

The expression of IL-22 in normal donors and uveitis patients. A SYBR Green based Real-time PCR analysis was performed to analyze IL-22 mRNA levels in both normal donors and uveitis patients as described in the Materials and Methods. Each bar on the X-axis represents one RNA sample from either normal donors or uveitis patients subjected to real-time PCR analysis for IL-22 transcript. The Y-axis represents relative expression of IL-22 levels.

IL-22 affects human primary pigment epithelial cells by decreasing their total tissue resistance and inducing apoptosis

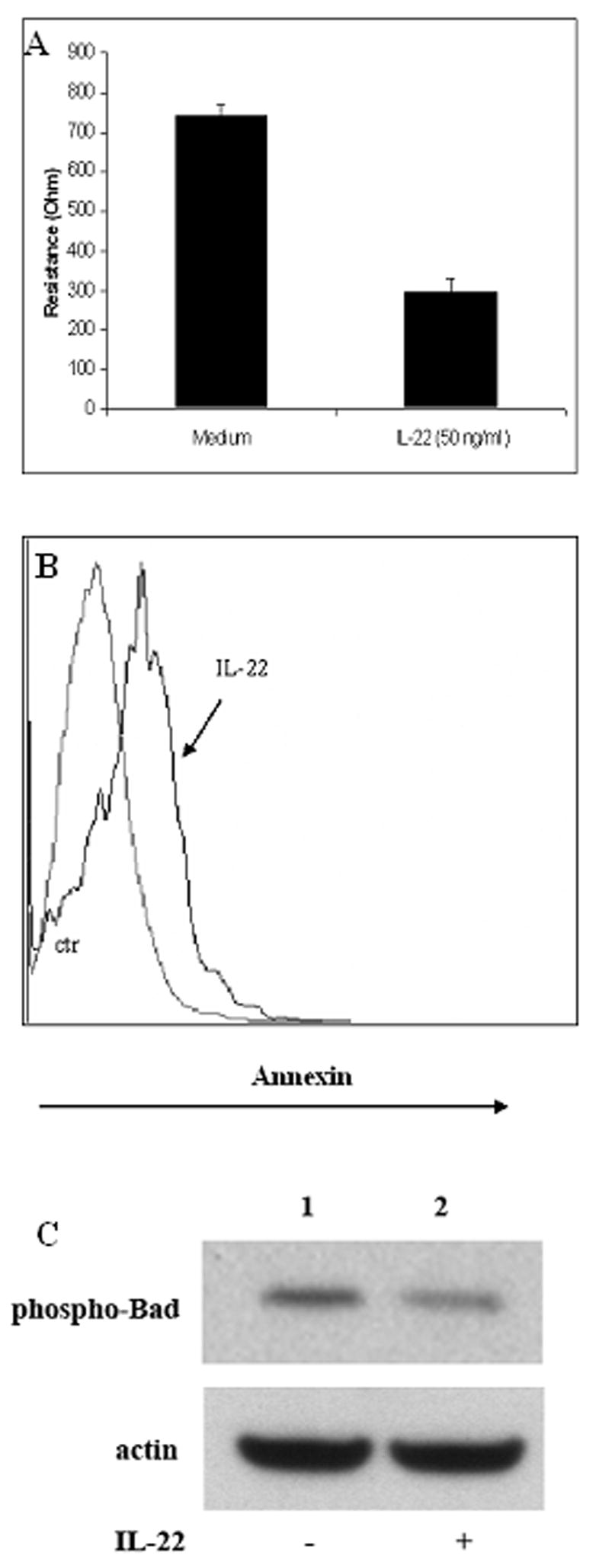

The expression of IL-22 has been recently shown to be associated with Th17 cells (17, 18). The primary target cells for IL-22 appeared to be epithelial cells(19, 20). To further understand the possible physiological impact and molecular mechanisms of IL-22 on ocular disease, we examined the effect of IL-22 on total epithelial resistance (TER) and the induction of apoptosis of human retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells. The retinal pigment epithelium forms the outer blood-retina barrier which physically separates the subretinal space (SRS) and the choroidal blood supply and actively participates in the creation of the immune privileged retinal environment by secreting various cytokines and chemokines (unpublished data). Both TER and apoptosis assays examine the physiological integrity of the retinal pigment epithelium, which is critical to preservation of the outer blood-retina barrier. As shown in Fig. 5, after 72 hours of stimulation, IL-22 significantly decreased total epithelium resistance (TER) by more than 60% as compared to matched controls (p<0.01). TER decreased from 742±29 to 296±37 Ω·cm2 (Panel A). IL-22 also induced RPE apoptosis when compared to the controls (Panel B). To further understand the mechanisms of IL-22 inducing apoptosis of RPE cells, we examined several proteins that are known to be involved in apoptosis signaling pathway, including cleaved caspase 3 and PARP, and phospho-Bad. We found that IL-22 seemed primarily targeting phosphorylated-Bad. As shown in Figure 5C, IL-22 treatment resulted in decreased phospho-Bad expression in RPE cells (panel C). However, there was no significant change in the levels of cleaved (active) caspase 3 and PARP expression which are also known to be involved in the apoptosis pathway (data not shown). This is the first evidence that IL-22 can target the human retinal pigment epithelial cells and potentially change their tissue integrity and preservation of the blood retinal barrier.

Figure 5.

IL-22 decreased total tissue resistance and induced apoptosis of primary human retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells. Monolayers of RPE cells grown on inserts were treated with recombinant human IL-22 (50 ng/ml). Resistance measurements and an apoptosis assay were performed after 72 hours of incubation with IL-22 as described in the Materials & Methods. Panel A shows summary bar-graph of total epithelium resistance (TER) changes after addition of IL-22 to hfRPE monolayers. Compared to matched controls TER significantly (~ 60%) decreased in IL-22 treated monolayers of RPE (n=3, p<0.01). Panel B is a histogram comparing Annexin staining for human primary RPE cells with and without IL-22 treatment. The grey-colored line is for control group while the bolded dark line for IL-22 treated RPE cells. There is a right shift of Annexin staining for IL-22 treated RPE cells when compared to the non-treated control group, indicating increased apoptosis induced by IL-22 treatment. In panel C, monolayers of RPE cells grown on inserts were treated with or without recombinant human IL-22 (50 ng/ml) for 48 hours, cells were lysed and subjected to Western analysis for phosphorylated-Bad. Although the beta-actin levels were comparable comparing IL-22 treated and untreated groups, the phosphorylated-Bad was decreased after IL-22 treatment.

Gene expression profiling on patient samples at distinct clinical stages

An important characteristic of uveitis is recurrence of disease (21). However, it is not clear for clinicians if this is a new inflammatory episode or is simply still the previous episode that has lingered. To address this question, we continuously monitored one patient over a 5-month span and collected samples during 3 distinct periods of disease activity, e.g. active, quiescent and recurrent/active stages. Interestingly, there were very few changes in gene expression profiling for the samples collected at the three time-points which represented three distinct clinical stages. As shown in Figure 6, arrays 1, 2 and 3 represent gene expression patterns when the disease was at clinically active, quiescent and recurrent/active stages respectively. The expression profiles (red=higher expression, green=lower expression after normalized with normal control group) of the 3 arrays were strikingly similar, notice that the colors distribution of the three profiles are very similar, suggesting the continuality of the underlying disease despite temporary relieve of clinical symptoms. However, analyses and data from more patients with similar clinical manifestations are required to further validate this initial observation.

Figure 6.

Clustergram analysis of gene expression profiles from samples for one patient collected at 3 clinically distinct stages. The numeric numbers represent different stages of the disease when the samples were collected and analyzed. Stage 1 is when the patient was having an initial active ocular inflammatory episode; stage 2 was when the disease quiescent and stage 3 when there was another active/recurrent episode. The X-axis listed all the gene symbols. Each colored band represents expression of a single gene from the patient at a specified clinical stage when compared to that from normal donors with higher expression in red and lower expression in green. Notice that the overall gene expression profiling of the samples at three stages is very similar.

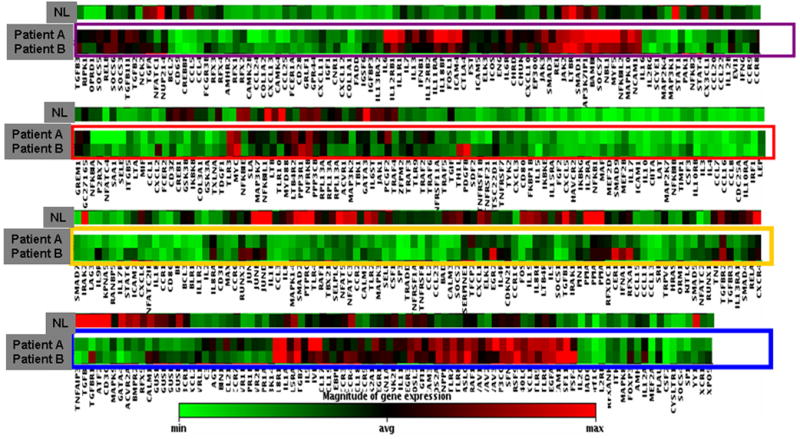

Gene expression profiling on samples from siblings with the same clinical diagnoses

Several lines of evidence suggest that genetic factors play an important role in autoimmune uveitis (22–24). During our study, we were able to enroll two male siblings, both diagnosed with intermediate uveitis. We performed a microarray analyses on their blood samples. Shown in Figure 7 is a clustergram comparing the gene profiling results of the siblings (labeled as patient A and patient B) vs. the pooled normal control samples (labeled as NL). The gene profiling patterns of the siblings (patient A and patient B) were dramatically different from that of normal controls, highlighting molecular evidence of differential gene expression of non-infectious uveitis patients. However, the expression profiles between the two siblings are very similar to each other (compare patient A to patient B). This is the first microarray analysis on such uveitis patients and the data further confirms the notion that genetic factors play an important role in ocular autoimmune diseases.

Figure 7.

Comparison of clustergram analysis of gene expression profiling of 2 male siblings (designated as patient A and patient B) with the same diagnosis of intermediate uveitis with that from normal controls (designated as NL). The cDNA microarray and clustergram analysis were performed as described above and in the Materials and Methods. The X-axis listed all the gene symbols in the cDNA microarray chips. The gene expression profiles from the 2 male siblings with the same diagnosis of intermediate uveitis (designated as patient A and patient B) were aligned with the profile from normal subjects (NL). As described above, each colored band represents expression of a single gene from either patient A or patient B or from normal subjects after normalization on house keeping genes, with higher expression in red and lower expression in green.

Discussion

The rationale to use pathway-specific cDNA microarray representing a portion of human genome is not only due to cost/efficiency consideration but is more importantly based on the fact that accumulated data have demonstrated that only a fraction of genes are actively transcribed (25). In addition, previous studies have provided strong evidence that non-infectious uveitis is an autoimmune, intraocular inflammatory disease (21). This study was initiated to investigate molecular profiles of non-infectious uveitis at the gene expression level. Therefore, using a pathway-specific cDNA microarray designed for autoimmune and inflammatory diseases is one of the reasonable strategies to meet our goals. We have analyzed RNA samples from 50 non-infectious uveitis patients using an inflammatory and autoimmune focused cDNA microarray. About 17% of the genes in this focused array were either up- or down-regulated in the uveitis patients when compared to normal controls. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first pathway specific and genome-wide demonstration of differential gene expression between non-infectious uveitis patients and normal controls. Since the RNA samples were purified from fresh PBMCs isolated immediately from whole blood, we believe that this differential gene expression pattern likely reflects the differential gene expression due to the disease activity of uveitis. By using clustergram analysis, we are able to classify uveitis into 4 sub-groups based on gene expression profiling results (Fig. 2). In addition, we have identified 4 sets of genes which define the four sub-groups of uveitis patients, designated as molecular signatures A, B, C and D. Although not all genes within each set were able to be completely categorized into a single general function, the genes within each set appear to be functionally related (Fig. 3).

The primary purpose for gene-expression profiling on autoimmune uveitis is to further understand molecular mechanisms and discover new pathways for this important ocular disease. Based on cDNA microarray data and real-time PCR validation data, we identified 28 genes that were either up- or down-regulated in the peripheral blood of uveitis patients with active disease when compared to normal control (Table 3). The majority of those genes (19 out of 28) have been previously reported to be associated with autoimmune uveitis, further validating the results of our study. However, among those up-regulated genes confirmed by real-time PCR, a set of IL-10 family genes, including IL-19, IL-20 and IL-22 which have not been previously associated with autoimmune uveitis are of particular interest. IL-10 has been implicated to play a protective role in the mouse EAU model and is up regulated in human uveitis patients (6, 15, 16). However, IL-19, IL-20 and IL-22 have not been implicated in human uveitis. The expression of IL-22 has been recently associated with Th17 cells (17, 18), a newly characterized T helper cell sub-population that are believed to primarily contribute to the pathogenesis of some Th1 mediated autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis(26–28). Th17 cells have also been implicated in the pathogenesis in a mouse uveitis model(12). IL-22 has little regulatory effect on immune cells but has primarily an effect on target tissues (29). It has been suggested that IL-22 may play an important role in autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis and ulcerative colitis (19, 20). Recently, IL-22 has been shown to interrupt the blood-brain barrier (BBB) tight junctions both in vitro and in vivo and it therefore promotes Th17 cells to transmigrate through the blood-brain barrier (30). The blood-retina barrier, similar to the blood-brain barrier, is well-known to be critical for the maintenance of intraocular homeostasis. Since Th17 cells have been implicated in the pathogenesis of autoimmune uveitis (12), we tested the effect of IL-22 on human primary retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). The data shows that IL-22 dramatically reduces total tissue resistance of human RPE cells and that IL-22 also induces RPE apoptosis (Fig. 5). The decrease of total epithelium resistance (TER) and the induction of apoptosis of RPE cells by IL-22 may have significant physiological and pathophysiological consequences in the eye. Epithelial electrical resistance measurement can be directly correlated to some barrier properties where in many cases TER decrease would result in an epithelial monolayer permeability increase (31–33). The reduction in TER would be consistent with the opening of a pathway that would allow biologically active molecules and immune system components to reach the site of retinal inflammatory injury in vivo(34, 35). Our data also showed that IL-22 decreased phospho-Bad level (Fig. 5C) and that might contributed to the induced apoptosis of fRPE cells. This data has not been reported in the literature and further investigation on the effect of IL-22 on phospho-Bad and its downstream signaling pathway will be very interesting. Overall, the data of IL-22’s effect on total tissue resistance as well as on inducing apoptosis suggests that IL-22 can affect the tissue integrity of RPE cells. Since RPE cells are critical for maintaining the blood-retina barrier, we would propose that IL-22 may target human RPE cells. Similar to what have been demonstrated in the multiple sclerosis that IL-22 affects on blood-brain barrier (30), IL-22 may disrupt the blood-retina barrier by reducing RPE total epithelial resistance and inducing RPE apoptosis. We suggest that this may be one of molecular mechanisms for uveitis pathogenesis. Our findings provide the first evidence that directly links IL-22 with human intraocular inflammatory disease.

One of the other applications of gene-expression profiling for clinical immunology is for molecular diagnoses such as in cancer (25, 36) or in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases (37, 38). We sought to correlate those four sub-groups of gene-expression profiles with clinical diagnoses and manifestations. However, we were not able to directly link the gene expression profiling data with clinical diagnoses. For example, patients with the diagnosis of intermediate uveitis can exhibit all four of the gene expression profiles. It is an intriguing question as to whether these molecular signatures can reflect distinctive molecular pathogenesis for autoimmune uveitis. Since all patients received at least 2 immunosuppressive agents for therapy, it is unlikely that immunosuppression would cause significant impact on the distinct molecular profiling results which resulted in the failure of correlation of clinical manifestation with the molecular profiling data. We propose, based on our data, that clinical manifestations may not necessarily be able to be correlated with molecular pathways of uveitic syndromes. In fact, similar observations have been made in large-B-cell lymphoma with no common set of genes expressed in all cases (39–41). We suggest that our data provided further evidence that underscore current challenges in the reconciliation of molecular signatures vs. clinical diagnoses. However, we can not completely exclude the possibility that this can also be simply due to the fact that there were not enough samples to reveal all possible patterns. Although we performed 51 microarray (50 patients plus 1 pooled normal control) analyses for this study, using this particular cDNA chip, a relatively small number of patients were represented in each sub-group of uveitis (table 1).

Nevertheless, the data for the first time demonstrate a unique pattern of differential gene expression between autoimmune uveitis patients and normal donors, as well as possible molecular sub-types among autoimmune uveitis patients. To further explore the applications of gene-expression profiling in autoimmune uveitis, we examined two other clinically relevant issues. The first question is if there is a difference of gene expression pattern for the same patient at different clinical stages. Many uveitis patients will typically experience multiple episodes of occurrence during the course of their disease. However, it is not well defined if those episodes were new or merely a continuation of the previous one. We examined the gene expression profiles of one particular patient with three defined clinical stages, active, quiescent and recurrent/active over a span of more than 5 months. We were surprised to see that the gene expression profiles from the three distinct stages are overall very similar (Fig. 6). This is a clear demonstration that the underlying mechanisms, represented by the consistent gene-expression profile, have not been changed despite temporary clinical regression with therapy. We propose that this represents strong molecular evidence that clinical quiescence may not be a true reflection of underlying disease inactivity for autoimmune uveitis. Molecular analyses, such as gene profiling, may prove to be a more reliable and accurate method in predicting the clinical prognosis for recurrent diseases. We also examined gene-expression profiles of a pair of male siblings who both have intermediate uveitis as a diagnosis. The gene expression profiles of the siblings were very similar to each other but dramatically different from the profile of normal controls (Fig. 7). Consistent with previous studies in both human and in a mouse uveitis model(22–24), our initial study on gene-expression profile data from 2 male siblings who suffered from the same uveitis support the hypothesis that genetic factors are important in the pathogenesis of human autoimmune uveitis. However, more data will be needed to further validate this initial observation.

This study not only implicated IL-22 in human uveitis, but also the involvement of both IL-19, IL20 and IL-25/IL-17E. It is of interest that IL-19 and IL-20, similar to IL-22, all belong to the IL-10 family. They share many biological characteristics with IL-22 and are shown to be associated with inflammatory disease (29). IL-25/IL-17E has been shown to boost type 2 immune response and allergy (42, 43). Although we do not currently understand the molecular mechanisms of the contribution of those cytokines to autoimmune uveitis, our finding that all those three genes are up regulated in human autoimmune intraocular inflammatory disease may suggest a novel mechanism that contributes to human autoimmune intraocular inflammatory disease (uveitis). Consistent with a recent report that Th17 cells are involved in the pathogenesis of autoimmune uveitis(12), the finding that IL-22, IL-19, IL-20 and IL-25/IL-17E may contribute to the pathogenesis of autoimmune intraocular inflammatory disease sheds new insight on the molecular mechanisms of uveitis, as well as other autoimmune inflammatory diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank NEI Uveitis clinical fellows, clinical coordinators and all patients who participated in this study. This work is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Eye Institute.

References

- 1.Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caspi RR. Immune mechanisms in uveitis. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1999;21:113–124. doi: 10.1007/BF00810244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nussenblatt RB. Proctor Lecture. Experimental autoimmune uveitis: mechanisms of disease and clinical therapeutic indications. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:3131–3141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caspi RR. Th1 and Th2 responses in pathogenesis and regulation of experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis. Int Rev Immunol. 2002;21:197–208. doi: 10.1080/08830180212063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nussenblatt RB, Scher I. Effects of cyclosporine on T-cell subsets in experimental autoimmune uveitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1985;26:10–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rizzo LV, Morawetz RA, Miller-Rivero NE, Choi R, Wiggert B, Chan CC, Morse HC, 3rd, Nussenblatt RB, Caspi RR. IL-4 and IL-10 are both required for the induction of oral tolerance. J Immunol. 1999;162:2613–2622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caspi RR, Roberge FG, Chan CC, Wiggert B, Chader GJ, Rozenszajn LA, Lando Z, Nussenblatt RB. A new model of autoimmune disease. Experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis induced in mice with two different retinal antigens. J Immunol. 1988;140:1490–1495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ham DI, Gentleman S, Chan CC, McDowell JH, Redmond TM, Gery I. RPE65 is highly uveitogenic in rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:2258–2263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nussenblatt RB, Kuwabara T, de Monasterio FM, Wacker WB. S-antigen uveitis in primates. A new model for human disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99:1090–1092. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1981.03930011090021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nussenblatt RB, Gery I, Ballintine EJ, Wacker WB. Cellular immune responsiveness of uveitis patients to retinal S-antigen. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;89:173–179. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(80)90108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Smet MD, Chan CC. Regulation of ocular inflammation--what experimental and human studies have taught us. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20:761–797. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(01)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amadi-Obi A, Yu CR, Liu X, Mahdi RM, Clarke GL, Nussenblatt RB, Gery I, Lee YS, Egwuagu CE. TH17 cells contribute to uveitis and scleritis and are expanded by IL-2 and inhibited by IL-27/STAT1. Nat Med. 2007;13:711–718. doi: 10.1038/nm1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maminishkis A, Chen S, Jalickee S, Banzon T, Shi G, Wang FE, Ehalt T, Hammer JA, Miller SS. Confluent monolayers of cultured human fetal retinal pigment epithelium exhibit morphology and physiology of native tissue. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3612–3624. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Z, Mahesh SP, Kim BJ, Buggage RR, Nussenblatt RB. Expression of glucocorticoid induced TNF receptor family related protein (GITR) on peripheral T cells from normal human donors and patients with non-infectious uveitis. J Autoimmun. 2003;21:83–92. doi: 10.1016/s0896-8411(03)00085-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demir T, Godekmerdan A, Balbaba M, Turkcuoglu P, Ilhan F, Demir N. The effect of infliximab, cyclosporine A and recombinant IL-10 on vitreous cytokine levels in experimental autoimmune uveitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2006;54:241–245. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.27948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayashi S, Guex-Crosier Y, Delvaux A, Velu T, Roberge FG. Interleukin 10 inhibits inflammatory cells infiltration in endotoxin-induced uveitis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1996;234:633–636. doi: 10.1007/BF00185297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreymborg K, Etzensperger R, Dumoutier L, Haak S, Rebollo A, Buch T, Heppner FL, Renauld JC, Becher B. IL-22 is expressed by Th17 cells in an IL-23-dependent fashion, but not required for the development of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2007;179:8098–8104. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang SC, Tan XY, Luxenberg DP, Karim R, Dunussi-Joannopoulos K, Collins M, Fouser LA. Interleukin (IL)-22 and IL-17 are coexpressed by Th17 cells and cooperatively enhance expression of antimicrobial peptides. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2271–2279. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugimoto K, Ogawa A, Mizoguchi E, Shimomura Y, Andoh A, Bhan AK, Blumberg RS, Xavier RJ, Mizoguchi A. IL-22 ameliorates intestinal inflammation in a mouse model of ulcerative colitis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:534–544. doi: 10.1172/JCI33194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng Y, Danilenko DM, Valdez P, Kasman I, Eastham-Anderson J, Wu J, Ouyang W. Interleukin-22, a T(H)17 cytokine, mediates IL-23-induced dermal inflammation and acanthosis. Nature. 2007;445:648–651. doi: 10.1038/nature05505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robert B, Nussenblatt SMW. uveitis. Elsevier; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mochizuki M, Kuwabara T, Chan CC, Nussenblatt RB, Metcalfe DD, Gery I. An association between susceptibility to experimental autoimmune uveitis and choroidal mast cell numbers. J Immunol. 1984;133:1699–1701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pennesi G, Caspi RR. Genetic control of susceptibility in clinical and experimental uveitis. Int Rev Immunol. 2002;21:67–88. doi: 10.1080/08830180212059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun B, Rizzo LV, Sun SH, Chan CC, Wiggert B, Wilder RL, Caspi RR. Genetic susceptibility to experimental autoimmune uveitis involves more than a predisposition to generate a T helper-1-like or a T helper-2-like response. J Immunol. 1997;159:1004–1011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Staudt LM. Molecular diagnosis of the hematologic cancers. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1777–1785. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrington LE, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, Turner H, Murphy TL, Murphy KM, Weaver CT. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1123–1132. doi: 10.1038/ni1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langrish CL, Chen Y, Blumenschein WM, Mattson J, Basham B, Sedgwick JD, McClanahan T, Kastelein RA, Cua DJ. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:233–240. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park H, Li Z, Yang XO, Chang SH, Nurieva R, Wang YH, Wang Y, Hood L, Zhu Z, Tian Q, Dong C. A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1133–1141. doi: 10.1038/ni1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sabat R, Wallace E, Endesfelder S, Wolk K. IL-19 and IL-20: two novel cytokines with importance in inflammatory diseases. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2007;11:601–612. doi: 10.1517/14728222.11.5.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kebir H, Kreymborg K, Ifergan I, Dodelet-Devillers A, Cayrol R, Bernard M, Giuliani F, Arbour N, Becher B, Prat A. Human TH17 lymphocytes promote blood-brain barrier disruption and central nervous system inflammation. Nat Med. 2007;13:1173–1175. doi: 10.1038/nm1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ban Y, Rizzolo LJ. A culture model of development reveals multiple properties of RPE tight junctions. Mol Vis. 1997;3:18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bradfield PF, Scheiermann C, Nourshargh S, Ody C, Luscinskas FW, Rainger GE, Nash GB, Miljkovic-Licina M, Aurrand-Lions M, Imhof BA. JAM-C regulates unidirectional monocyte transendothelial migration in inflammation. Blood. 2007;110:2545–2555. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-078733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang CW, Ye L, Defoe DM, Caldwell RB. Serum inhibits tight junction formation in cultured pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:1082–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muller WA. Leukocyte-endothelial-cell interactions in leukocyte transmigration and the inflammatory response. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:327–334. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zen K, Parkos CA. Leukocyte-epithelial interactions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:557–564. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenwald A, Staudt LM. Clinical translation of gene expression profiling in lymphomas and leukemias. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:258–263. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.32901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Villalta D, Tozzoli R, Tonutti E, Bizzaro N. The laboratory approach to the diagnosis of autoimmune diseases: is it time to change? Autoimmun Rev. 2007;6:359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whitney LW, Ludwin SK, McFarland HF, Biddison WE. Microarray analysis of gene expression in multiple sclerosis and EAE identifies 5-lipoxygenase as a component of inflammatory lesions. J Neuroimmunol. 2001;121:40–48. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00438-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE, Ma C, Lossos IS, Rosenwald A, Boldrick JC, Sabet H, Tran T, Yu X, Powell JI, Yang L, Marti GE, Moore T, Hudson J, Jr, Lu L, Lewis DB, Tibshirani R, Sherlock G, Chan WC, Greiner TC, Weisenburger DD, Armitage JO, Warnke R, Levy R, Wilson W, Grever MR, Byrd JC, Botstein D, Brown PO, Staudt LM. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403:503–511. doi: 10.1038/35000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenwald A, Wright G, Chan WC, Connors JM, Campo E, Fisher RI, Gascoyne RD, Muller-Hermelink HK, Smeland EB, Giltnane JM, Hurt EM, Zhao H, Averett L, Yang L, Wilson WH, Jaffe ES, Simon R, Klausner RD, Powell J, Duffey PL, Longo DL, Greiner TC, Weisenburger DD, Sanger WG, Dave BJ, Lynch JC, Vose J, Armitage JO, Montserrat E, Lopez-Guillermo A, Grogan TM, Miller TP, LeBlanc M, Ott G, Kvaloy S, Delabie J, Holte H, Krajci P, Stokke T, Staudt LM. The use of molecular profiling to predict survival after chemotherapy for diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1937–1947. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shipp MA, Ross KN, Tamayo P, Weng AP, Kutok JL, Aguiar RC, Gaasenbeek M, Angelo M, Reich M, Pinkus GS, Ray TS, Koval MA, Last KW, Norton A, Lister TA, Mesirov J, Neuberg DS, Lander ES, Aster JC, Golub TR. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma outcome prediction by gene-expression profiling and supervised machine learning. Nat Med. 2002;8:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang YH, Angkasekwinai P, Lu N, Voo KS, Arima K, Hanabuchi S, Hippe A, Corrigan CJ, Dong C, Homey B, Yao Z, Ying S, Huston DP, Liu YJ. IL-25 augments type 2 immune responses by enhancing the expansion and functions of TSLP-DC-activated Th2 memory cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1837–1847. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Angkasekwinai P, Park H, Wang YH, Wang YH, Chang SH, Corry DB, Liu YJ, Zhu Z, Dong C. Interleukin 25 promotes the initiation of proallergic type 2 responses. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1509–1517. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]