Abstract

A whole cell-based assay using Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains that overexpress Candida albicans CDR1 and MDR1 efflux pumps has been employed to screen natural product extracts for reversal of fluconazole resistance. The tropical green alga Penicillus capitatus was selected for bioassay-guided isolation, leading to the identification of capisterones A and B (1 and 2), which were recently isolated from this alga and shown to possess antifungal activity against the marine pathogen Lindra thallasiae. Current work has assigned their absolute configurations using electronic circular dichroism and determined their preferred conformations in solution based on detailed NOE analysis. Compounds 1 and 2 significantly enhanced fluconazole activity in S. cerevisiae, but did not show inherent antifungal activity when tested against several opportunistic pathogens, or cytotoxicity to several human cancer and non-cancerous cell lines (up to 35 μM). These compounds may have a potential for combination therapy of fungal infections caused by clinically relevant azole-resistant strains.

The molecular mechanisms of antifungal drug resistance may involve a variety of factors such as mutation of target genes and decreased drug concentrations in the cells due to overexpression of efflux pumps.1,2 In recent years, the rapid development of such drug resistance, particularly for azole antifungals, has highlighted the need for new strategies in antimycotic therapies.1-5 Efflux pump inhibition has been considered as a promising approach in this regard. Two families of efflux pumps found in Candida albicans include the major facilitators (multidrug resistance, MDR) that are fueled by a proton gradient and the P-glycoprotein ABC transporters (Candida drug resistance, CDR) that require ATP hydrolysis for energy. Within each family, several subtypes have been discovered (i.e., CDR1, CDR2, MDR1).1,2 We have established a whole cell-based assay using Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains that overexpress C. albicans CDR1 and MDR1 efflux pumps to screen for natural products that can reverse fluconazole resistance and may not be necessarily antifungal.6

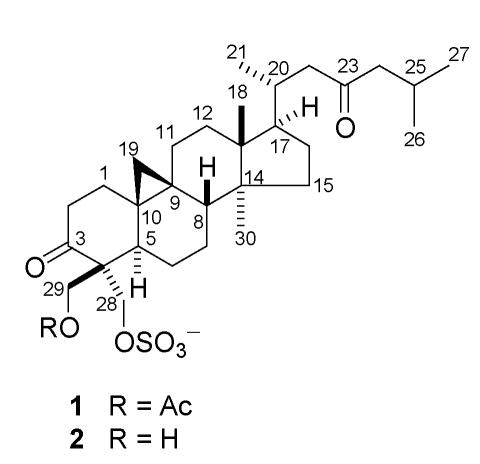

In a continuing effort to search for new efflux inhibitors from natural sources, we have screened over 5000 marine extracts from the National Cancer Institute Open Repository. In the presence of a subinhibitory concentration of fluconazole, an extract of the tropical green alga Penicillus capitatus (Halimedaceae) that had an IC50 value of 55 μg/mL against S. cerevisiae DSY 415 strain (overexpressing the CDR1 efflux pump) and an IC50 value of < 6 μg/mL against S. cerevisiae DSY 416 strain (overexpressing the MDR1 efflux pump) was selected for bioassay-guided fractionation. Two cycloartanone triterpene sulfates (1 and 2) that significantly enhanced fluconazole activity in the two efflux pump overexpressing strains were identified. Analysis of the spectroscopic data including high resolution MS, IR, and NMR permitted identification of compounds 1 and 2 as capisterones A and B, respectively, that were recently isolated from this alga and shown to possess antifungal activity against the marine pathogen Lindra thallasiae. However, the absolute configuration and conformation of the two compounds were undefined.7 This report describes the assignment of their absolute configuration and conformation as well as their biological activities.

Compound 1 showed a negative specific rotation, −6.3 (MeOH, c 0.80), in contrast to most naturally occurring cycloartan-3-ones and its derivatives which generally have a positive optical rotation value;8-19 while compound 2 gave a small positive specific rotation, +2.1 (MeOH, c 0.33). The above specific rotation values for the two compounds are also close to those reported by Puglisi et al.7 This posed the question whether these compounds still possess the absolute configuration of the typical naturally occurring cycloartane skeleton. Although acetylation of 2 may induce a negative optical rotation in 1, unambiguous evidence is needed to address the absolute configuration of the two compounds.

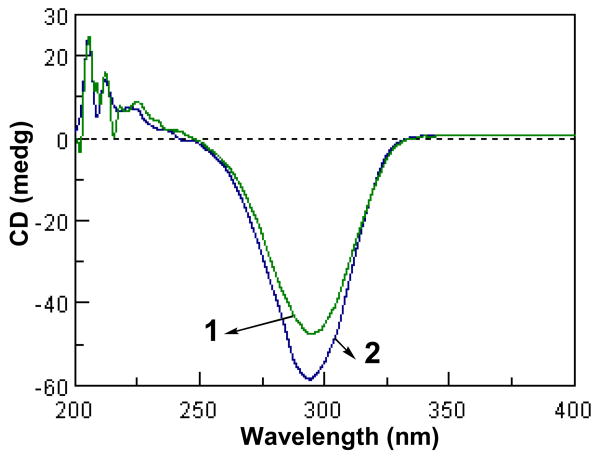

Circular dichroism (CD) and optical rotatory dispersion (ORD) have played important roles in determining the absolute configuration of chiral molecules. In particular, the recent advances on theoretical calculations of CD spectra and optical rotations have greatly enhanced their value in this regard.20-22 It has been reported that 3-keto-5α-steroids and their 4α-methyl derivatives exhibit a positive Cotton effect around 300 nm in their ORD spectra, while their 4,4-dimethyl derivatives (or natural triterpenoids) displayed a negative Cotton effect in this region.8 For cycloartan-3-ones, the introduction of the 9,19-cylopropyl functionality does not affect the sign of the Cotton effect in their ORD/CD spectra (presumably due to retention of the A-ring conformation),8,23-25 although additional substitutions on ring B or other rings may alter the sign of the Cotton effect.23 Compounds 1 and 2 exhibited strong negative Cotton effects around 290 nm in their CD spectra. When compared with the cycloartan-3-one compounds which generally give a negative Cotton effect in the 290-300 nm range in their ORD or CD spectra,23-25 compounds 1 and 2 should possess the same absolute configuration for the tetracyclic ABCD-ring system as in the naturally occurring cycloartane triterpenes. The very similar CD Cotton effects of 1 and 2 indicate that the acetyl substitution in 1 does not contribute to its overall CD absorption curve (Fig.1), although this derivatization did alter the sign of the specific rotation from positive in 2 to negative in 1.

Fig. 1.

Experimental CD spectra of compounds 1 and 2.

Theoretical calculation of the electronic CD spectrum (ECD) of compound 2 based on the arbitrarily assigned absolute configuration as shown in its structural formula was performed using time-dependant density functional theory (TDDFT)26-29 with 6-31G* basis set by Gaussian0330 program package. The results were in agreement with the experimental CD spectrum: a high-amplitude negative Cotton effect was obtained at 293 nm, which was attributable to the n→π* transition of the C=O functionality. Detailed calculating data of excitation energies, oscillator strengths, and rotational strengths for the three transition states requiring lowest excitation energies are summarized in Table 1 for compound 2. This is the first correlation of calculated and experimental CD results for this class of compounds. Thus, the absolute configuration of compound 2 has been firmly established as shown for typical naturally occurring cycloartanane triterpenes which are biosynthesized in a highly stereoselective way.31 Since a direct chemical conversion of 2 into 1 has been achieved by acetylation,7 compound 1 should possess the same absolute configuration.

Table 1.

Calculated CD Data for Compound 2

| E (ev) | λ (nm) | f a | Rvelocityb | Rlengthb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.2315 | 293 | 0.0007 | −17.7165 | −18.9575 |

| 4.3083 | 287 | 0.0001 | −1.7954 | −5.6371 |

| 4.7717 | 259 | 0.0013 | −1.1733 | −0.5280 |

Oscillator strengths;

Rotatory strengths in cgs (10-40 erg. esu. cm/Gauss)

Cycloartane triterpenes and their glycosides which are widely distributed in terrestrial plants, but rarely isolated from marine sources, are an important class of biologically active compounds.7, 8-19 Few studies have investigated the conformation of this class of compounds in solution, although it is presumed that the conformation of the tetracyclic ABCD-ring system may be similar to those whose single crystal structures have been determined by X-ray crystallographic analysis. Verotta et al.32 studied the conformation of two cycloartan-3-ol glucosides by using NMR in pyridine-d6 and molecular modeling (AM1). They proposed that the most stable conformer (focusing on the aglycone moiety) possesses a chair conformation for ring A and half-chair conformation for both rings B and C. A less stable conformation in which ring C adopts a half-boat form may also exist due to an equilibrium with the former in solution. They further demonstrated that the hydroxyl substitution at C-6 of the aglycone does not significantly affect the overall conformations of the tetracyclic ABCD-ring system. Horgen et al.16 also briefly described the conformation of a cycloartan-3-ol sulfate in MeOH-d4 based on NOE evidence and molecular modeling (HyperChem, MM+ force field). A twisted-boat conformation for ring C was evident from the notable NOE correlation between H-11α and Me-30. It is important to understand the conformations of biologically active compounds in solution since they exert biological functions in aqueous media. The two simple biologically active cycloartanone compounds 1 and 2 are apparently ideal models for providing conformational information within this class of compounds.

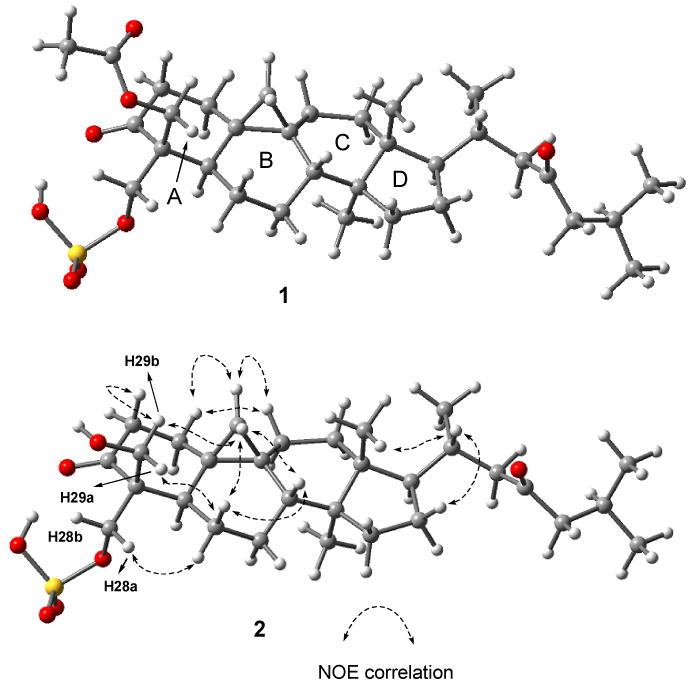

Previous structure elucidation of capisterones A (1) and B (2) was primarily based on the analysis of their NMR spectra recorded in DMSO-d6.7 Here, improved resolution for the NMR spectra of both compounds was achieved in MeOH-d4. Well-resolved NOESY spectra were obtained to assign their relative configuration and conformation in solution. For example, in the case of compound 2, notable NOE correlations were observed between H-19β and H-6β (axial)/H-8β (axial), H-19α and H-1β (equatorial) /H-11β (equatorial), Me-30 and H-17α (axial), and Me-18 and H-20. The NOE correlation between one of the methylene proton and H-6β permitted assignment of this proton as H-29a (pro-S) while the H-29b (pro-R) showed a correlation with H-2β (axial). The assignments of the remaining geminal protons were also facilitated by the NOE correlations. All the observed NOE correlations satisfactorily supported the preferred conformation of 2 as shown in Figure 2, which was generated by Chem3D Pro™ 8.0 and energy-minimized by MM2, and then optimized at B3LYP/6-31G* level with Gaussian03 program package30 (see geometrical data in Table 2). The three six-membered rings A-C adopted chair, twisted and twisted-boat conformations, respectively, while the five-membered ring D was in a slightly distorted envelope conformation. The twisted-boat conformation of ring C is supported by the NOE correlation between H-11α (axial) and Me-30 and the theoretically calculated interatomic distance of 2.064 Å. This is in agreement with the finding by Horgen et al.16 in the case of a cycloartan-3-ol compound as discussed above. The calculated torsion angles for 2 are almost identical to those of an analog, (24R)-24,25-dihydroxycycloartan-3-one, which were determined by an X-ray crystallographic analysis33 (Table 2). This may suggest that the preferred conformation for this class of compounds in solution is generally in agreement with their crystal structures. Also, it is noted that all the calculated distances between the protons in this preferred conformation that show NOE correlations listed in Table 2 are less than 2.6 Å. To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive NOE analysis of cycloartan-3-one derivatives,8-19 and thus leading to the assignment of a preferred conformation of compound 2 in solution with the aid of advanced computational methods (B3LYP/6-31G*). This information indeed furnished the foundation for the theoretical calculation of its ECD spectrum. Since the accuracy and reliability of a theoretically calculated CD spectrum largely depends on conformational analysis, the agreement of the calculated and experimental ECD spectra of compound 2 confirmed the presence of the assigned conformer in solution.

Fig. 2.

Preferred conformations of compounds 1 and 2 in CD3OD.

Table 2.

Selected Geometric Parameters for Compound 2

| Torsion angle (°) | 2a | 2b | Ref. compoundc |

|---|---|---|---|

| O3-C3-C2 | 116.51 | 119.70 | 119.37 |

| O3-C3-C4 | 118.01 | 122.77 | 122.27 |

| C19-C9-C10 | 60.11 | 59.36 | 59.44 |

| C1-C2-C3-O3 | −158.11 | −133.98 | −138.3 |

| O3-C3-C4-C5 | 162.61 | 137.95 | 138.7 |

| C7-C8-C9-C19 | 91.11 | 89.03 | 89.1 |

| C6-C5-C10-C19 | − 49.11 | − 48.29 | − 49.1 |

| C5-C10-C19-C9 | 108.91 | 108.69 | 109.1 |

| C14-C13-C17-C20 | −161.21 | −165.03 | −165.5 |

| C15-C16-C17-C20 | 146.01 | 149.30 | 151.1 |

| C20-C17-C16 | 111.51 | 112.87 | 112.22 |

| C20-C17-C13 | 120.11 | 119.50 | 120.70 |

Data from the conformer generated by Chem3D Pro 8.0.

Data from conformer optimized by B3LYP/6-31G*.

X-ray data of (24R)-24,25-dihydroxycycloartan-3-one.33

Similarly, the 1H and 13C NMR assignments of compound 1 in MeOH-d4 were facilitated by 2D NMR including COSY, HMQC, HMBC, and NOESY. The NOE correlation patterns in the NOESY spectrum of 1 were identical to those in 2, indicating that both shared a similar conformation in solution as shown in Fig.2.

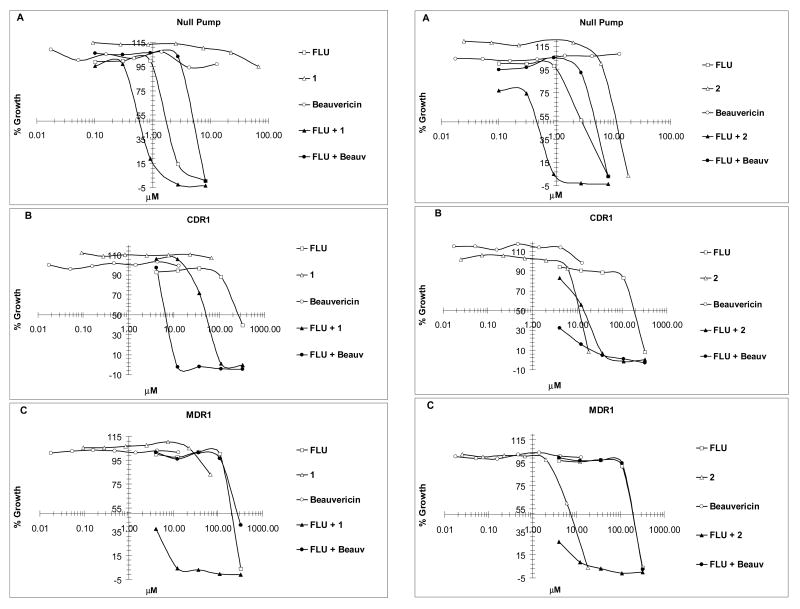

Compounds 1 and 2 were examined for their fluconazole reversal activity by a checkerboard assay that measures the combination treatment effect of two agents on a microbe, in which a fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) value is used to define the effect to be synergistic (FIC ≤ 0.5), additive (0.5<FIC ≤ 1), indifferent (1<FIC ≤ 2), or antagonistic (FIC > 2).34 Two S. cerevisiae strains that overexpress C. albicans CDR1 (DSY 415) and MDR1 (DSY 415) efflux pumps were used in this study, along with the null pump strain (DSY 390).6 Compound 1 alone was inactive against the above three strains (IC50 > 67 μM), while compound 2 did show some inherent antifungal activity (IC50, 7∼11 μM) against the three strains. Both compounds significantly enhanced fluconazole activity in the CDR1 and MDR1 efflux pump-overexpressing strains (FIC < 0.5) (Fig. 3, Table 3). In particular, compound 1 showed strong synergistic effects in the MDR1 strain (FIC, 0.08). It appears that the MDR efflux strain is more susceptible to the two compounds.

Fig.3.

Dose-response curves of fluconazole (FLU) and compounds 1 and 2 alone and FLU in combination with 1 (22.5 μM), 2 (6.0 μM) and beauvericin (Beauv) (12.8 μM) in the null pump (A), CDR1 (B) and MDR1 (C) S. cerevisiae strains.

Table 3.

Fractional Inhibitory Concentrations (FICs)a,b of Combination Treatment of Fluconazole (FLU)c with 22.5 μM 1, 6.03 μM 2, or 12.8 μM beauvericin using IC50 as an endpoint.

| Sample | Null Pump | CDR1 | MDR1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.55 | 0.33 | 0.08 |

| 2 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.15 |

| Beauvericind | 2.67 | 0.05 | 2.00 |

FIC ≤ 0.5 = synergistic; 0.51-1.0 = additive; 1.1-2.0 = indifferent; >2.0 = antagonistic.

FICs are estimated due to lack of IC50 values for 1 or beauvericin alone (inactive at highest test concentrations of 67.4 and 12.8 μM, respectively.)

FLU concentrations used for FIC calculations: 0.91 μM for null pump and 108.8 μMfor CDR1 and MDR1.

A positive control of CDR1 pump.

Compounds 1 and 2 did not show any inherent antifungal activity when tested against several opportunistic pathogens in our antifungal assay panel consisting of C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. krusei, Cryptococcus neoformans and Aspergillus fumigatus35,36 and were not cytotoxic agasint several human cancer cell lines (KB, SK-MEL, BT-549, and SK-OV-3) and non-cancerous Vero cells (up to 35 μM).37 Studies on the potential of these compounds and their derivatives for combination treatment of fungal infections caused by clinically relevant azole-resistant strains are underway.

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures

Optical rotations were measured on Autopol® IV automatic polarimeter. CD spectra were obtained on a JASCO J-715 spectropolarimeter. IR spectra were recorded on an ATI Mattson Genesis Series FTIR spectrometer. NMR spectra were recorded on Varian Mercury-400BB or Varian Inova-600 instruments. High resolution TOFMS were measured on an Agilent Series 1100 SL equipped with an ESI source. Column chromatography was done on silica gel (40 μm, J. T. Baker) and reversed-phase silica gel (RP-18, 40 μm, J. T. Baker). Semi-preparative HPLC was conducted on an ODS (Prodigy®) column (250 × 10 mm, 10 μm) using UV detector at 220 nm. TLC was performed on silica gel sheets (Silica Gel 60 F254, Merck, Germany) and reversed-phase plates (RP-18 F254S, Merck, Germany). General procedures for antifungal and cytotoxicity assays have been described in our previous papers.35-37

Algal Material

The original algal material P. capitatus was collected in Sweetings Cay, Bahamas (Western Atlantic, Caribbean, Longitude: 77°55″ W, Latitude: 26°36″ N) by the Harbor Branch Oceanographic in early 1988. The NCI received the material on March 18, 1988, from which a CHCl3-MeOH (1:1) extract was prepared. A voucher for this sample is being kept at the Smithsonian Herbarium (voucher #: Q66130939).

Isolation

The CHCl3-MeOH extract (331.3 mg) was chromatographed on silica gel (42 g) eluting with CH2Cl2 (300 mL), CH2Cl2-MeOH (9:1, 750 mL; 6:1, 840 mL) and MeOH (200 mL) to afford 10 pooled fractions (A-J) according to TLC. Fr. D (29.4 mg) and fr. F (18.9 mg) which showed enhanced activity for reversal of fluconazole resistance in our bioassay system were purified by HPLC (ODS) using 70% MeOH to yield compound 1 (10.5 mg) and 2 (5.3 mg), respectively.

Capisterone A (1): White powder, −6.3 (MeOH, c 0.80) {ref. 7: −9.6 (MeOH, c 0.019)}; CD (c 0.0011 M, MeOH) λ ([θ]) 294 (− 4 309) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 3474 (br), 2954, 2817, 1738, 1711, 1646, 1468, 1378, 1229, 1010, 813 cm−1 [In contrast to the sodium salt form of capisterone A in the previous report,7 the strong IR absorption band at 3474 (br) cm−1 indicated the presence of a hydroxyl group in the molecule due to the free hydrogen form or at least partial hydrogen form]; NMR (CD3OD) and HRTOFMS data: see Supporting Information.

Capisterone B (2):White powder, +2.1 (MeOH, c 0.33) {ref. 7: +0.19 (MeOH, c 0.0052)}; CD (c 0.0011 M, MeOH) λ ([θ]) 294 (− 5 325) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 3431 (br), 2955, 2872, 1709, 1469, 1377, 1266, 1219, 1065, 999, 826 cm−1 [In contrast to the sodium salt form of capisterone B in the previous report,7 the broad IR absorption at 3431 cm−1 indicated the presence of a hydroxyl group in the molecule due to the free hydrogen form or at least partial hydrogen form]; NMR (CD3OD) and HRTOFMS data: see Supporting Information.

Computational method

Theoretical calculation of CD spectrum for compound 2 was performed with Gaussian03 program package.30 B3LYP/6-31G* method was employed to optimize the geometry of compound 2 (gas form) and vibrational analysis was done at the same level. Calculation on the electronic CD spectrum was then performed using time-dependant density functional theory (TDDFT) with 6-31G* basis set. 26-29

Assay for Reversal of Fluconazole Resistance in S. cerevisiae Strains

The detailed procedure has been described in a previous paper.6 The growth inhibition is shown in Fig. 3. The fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) is calculated by the formula [IC50 of test compound in combination with fluconazole (FLU)/ IC50 of test compound + IC50 of FLU in combination with test compound/ IC50 of FLU alone]. Beauvericin, a cyclic depsipeptide known to inhibit the CDR1 pump, is used as a positive control.

Supplementary Material

NMR and MS spectral data of compounds 1 and 2. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was conducted in a facility constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement Program Grant Number CO6 RR-14503-01 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health. We thank the Natural Products Branch Repository Program at the National Cancer Institute for providing marine extracts from the NCI Open Repository. We gratefully acknowledge Ms. Marsha Wright for biological testing, Dr. D. Chuck Dunbar and Mr. Frank M. Wiggers for obtaining spectroscopic data, and Ms. Sharon Sanders for technical assistance. This work was supported by the NIH, NIAID, Division of AIDS, Grant No. AI 27094 and the USDA Agricultural Research Service Specific Cooperative Agreement No. 58-6408-2-0009.

References and Notes

- 1.White TC, Bowden RA, Marr KA. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:382–402. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.2.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White TC, Holleman S, Dy F, Mirels LF, Stevens DA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1704–1713. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.6.1704-1713.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanglard D. Curr Opinion Microbiol. 2002;5:379–85. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(02)00344-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White TC, Harry J, Oliver BG. Mycota. 2004;12:319–337. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong-Beringer A, Kriengkauykiat J. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23:1441–1462. doi: 10.1592/phco.23.14.1441.31938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacob MR, Hossain CF, Mohammed KA, Smillie TJ, Clark AM, Walker LA, Nagle DG. J Nat Prod. 2003;66:1618–1622. doi: 10.1021/np030317n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puglisi MP, Tan LT, Jensen PR, Fenical W. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:7035–7039. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Djerassi C, Halpern O, Halpern V, Riniker B. J Am Chem Soc. 1958;80:4001–4015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boar Robin B, Romer C Richard. Phytochemistry. 1975;14:1143–1146. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isaev MI, Gorovits MB, Abubakirov NK. Khim Prirod Soed. 1985:431–485. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isaev MI, Gorovits MB, Abubakirov NK. Khim Prirod Soed. 1989:156–175. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishizawa M, Emura M, Yamada H, Shiro M, Chairul, Hayashi Y, Tokoda H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:5615–5618. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greca MD, Fiorentino A, Monaco P, Previtera L. Phytochemistry. 1994;35:1017–1022. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Govindan M, Abbas SA, Schmitz FJ. J Nat Prod. 1994;57:74–78. doi: 10.1021/np50103a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshikawa K, Katsuta S, Mizumori J, Arihara S. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:1229–1234. doi: 10.1021/np000126+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horgen FD, Sakamoto B, Scheuer PJ. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:210–216. doi: 10.1021/np990448h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gutierrez-Lugo MT, Sing MP, Maiese WM, Timmermann BN. J Nat Prod. 2002;65:872–875. doi: 10.1021/np020044g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang HJ, Tan GT, Hoang VD, Hung NV, Cuong NM, Soejarto DD, Pezzuto JM, Fong HHS. J Nat Prod. 2003;66:263–268. doi: 10.1021/np020379y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hossain CF, Jacob MR, Clark AM, Walker LA, Nagle DG. J Nat Prod. 2003;66:398–400. doi: 10.1021/np020431q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stephens PJ, McCann DM, Butkus E, Stončius S, Cheeseman JR, Frisch MJ. J Org Chem. 2004;69:1948–1958. doi: 10.1021/jo0357061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bringmann G, Mühlbacher J, Reichert M, Dreyer M, Kolz J, Speicher A. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:9283–9290. doi: 10.1021/ja0373162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiberg KH, Vaccaro PH, Cheeseman JR. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:1888–1896. doi: 10.1021/ja0211914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isaev MI, Moiseeva GP, Gorovits MB, Abubakirov NK. Khim Prir Soed. 1986:614–618. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herz W, Watenabe K, Kulanthaivel P, Blount JF. Phytochemistry. 1985;24:2645–2654. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kusano G. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2001;121:497–521. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.121.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grimme S, Harren J, Sobanski A, Vögtle G. Eur J Org Chem. 1998:1491. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Furche G. J Chem Phys. 2001;114:5982. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yabana K, Bertsch GG. Phys Rev A. 1999;60:1271. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Autschbach J, Ziegler T, Van Gisbergen JA, Baerends EJ. J Chem Phys. 2002;116:6930. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Zakrzewski VG, Montgomery JA, Jr, Vreven T, Kudin KN, Burant JC, Millam JM, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Barone V, Mennucci B, Cossi M, Scalmani G, Rega N, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Klene M, Li X, Knox JE, Hratchian HP, Cross JB, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Ayala PY, Morokuma K, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Zakrzewski VG, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Strain MC, Farkas O, Malick DK, Rabuck AD, Raghavachari K, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cui Q, Baboul AG, Clifford S, Cioslowski J, Stefanov BB, Liu G, Liashenko A, Piskorz P, Komaromi I, Martin RL, Fox DJ, Keith T, Al-Laham MA, Peng CY, Nanayakkara A, Challacombe M, Gill PMW, Johnson B, Chen W, Wong MW, Gonzalez C, Pople JA. Gaussian 03, Revision B.02. Gaussian, Inc.; Pittsburgh PA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shibuya M, Adachi S, Ebizuka Y. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:6995–7003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verotta L, Orsini F, Tatò M, El-Sebakhy NA, Toaima SM. Phytochemistry. 1998;49:845–852. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhattacharyya K, Kar T, Palmer RA, Potter BS, Inada A. Acta Crystallogr C. 2000;56:979–980. doi: 10.1107/s0108270100004820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li R. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1401–1405. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.6.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li XC, Jacob MR, ElSohly HN, Nagle DG, Walker LA, Clark AM. J Nat Prod. 2003;65:1132–1135. doi: 10.1021/np030196r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li XC, Ferreira D, Jacob MR, Zhang QF, Khan SI, ElSohly HN, Nagle DG, Smillie TJ, Walker LA, Clark AM. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6872–6873. doi: 10.1021/ja048081c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muhammad I, Dunbar DC, Khan SI, Tekwani BL, Bedir E, Takamatsu S, Ferreira D, Walker LA. J Nat Prod. 2003;66:962–967. doi: 10.1021/np030086k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

NMR and MS spectral data of compounds 1 and 2. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.