Abstract

Despite numerous studies asserting the prevalence of marital conflict among families of children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), evidence is surprisingly less convincing regarding whether parents of youth with ADHD are more at-risk for divorce than parents of children without ADHD. Using survival analyses, this study compared the rate of marital dissolution between parents of adolescents and young adults with and without ADHD. Results indicated that parents of youth diagnosed with ADHD in childhood (n=282) were more likely to divorce and had a shorter latency to divorce than parents of children without ADHD (n=206). Among a subset of those families of youth with ADHD, prospective analyses indicated that maternal and paternal education level, paternal antisocial behavior, and child age, race/ethnicity, and oppositional-defiant/conduct problems each uniquely predicted the timing of divorce between parents of youth with ADHD. These data underscore how parent and child variables likely interact to exacerbate marital discord and, ultimately, dissolution among families of children diagnosed with ADHD in childhood.

Keywords: ADHD, ODD/CD, Antisocial behavior, Divorce, Marital conflict

Discord between parents of youth with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is not uncommon. Parents of children with ADHD report less marital satisfaction, fight more often, and use fewer positive and more negative verbalizations during childrearing discussions than parents of children without ADHD (Barkley, Fischer, Edelbrock, & Smallish, 1991; Jensen, Shervette, Xenakis, & Bain, 1988; Johnston & Behrenz, 1993). Studies also highlight the link between severity of child behavior and interparental discord, reporting greater discord among parents of youth with ADHD and comorbid oppositional-defiant disorder (ODD) or conduct disorder (CD) than parents of youth with ADHD-alone or without ADHD (Barkley, Anastopoulos, Guevremont, & Fletcher, 1992; Lindahl, 1998; Wymbs, Pelham, Gnagy, & Molina, 2008). Given the stressful nature of parenting children with ADHD (Johnston & Mash, 2001), the common presence of multiple environmental stressors in these families (Counts, Nigg, Stawicki, Rappley, & Von Eye, 2005), and the linkage between these variables and marital conflict (Cummings & Davies, 1994), the elevated rates of interparental discord in families of youth with ADHD is not surprising.

The prevalence and severity of conflict between parents of children with ADHD is concerning given data suggesting that specific conflict resolution tactics predict later divorce. Specifically, couples observed to exhibit elevated levels of maladaptive problem-solving methods are more likely to divorce (Gottman, Coan, Carrere, & Swanson, 1998; Gottman & Levenson, 1992; Rogge & Bradbury, 1999; Rogge, Bradbury, Hahlweg, Engl, & Thurmaier, 2006). Heyman and colleagues (Heyman & Hunt, 2007; Heyman & Slep, 2001), conversely, caution against over-interpreting findings from divorce prediction studies given the prevalence of important methodological limitations (e.g., failing to cross-validate prediction equations). Acknowledging their concern, this line of research, at a minimum, underscores the potential of highly discordant couples (e.g., parents of children with ADHD) divorcing over time.

Surprisingly, research has not consistently found that divorce rates differ between parents of children and adolescents with and without ADHD. Although several studies revealed a greater prevalence of divorce among families of children and adolescents with ADHD (Barkley, Fischer, Edelbrock, & Smallish, 1990; Brown & Pacini, 1989; Faraone, Biederman, Keenan, & Tsuang, 1991; Jensen et al., 1988), an equal number found no differences (Barkley et al. 1991; McGee, Williams, & Silva, 1984; Minde et al., 2003; Schachar & Wachsmuth, 1991). These conflicting findings likely occurred for two reasons: (1) all but two studies (Barkley et al. 1990, 1991) assessed parents of pre-adolescents and (2) all studies used a single assessment point. Investigations using longitudinal data sets with families of children across a wider age-range are needed to examine the probability of divorce over a greater passage of time. Furthermore, because young children are not the only ones negatively affected by divorce, but adolescents and young adults as well (Amato, 2000), studies are needed to compare the prevalence of divorce in families with or without ADHD youth of all ages.

Marital relations researchers have identified a number of variables that place couples at risk for divorce (e.g., Gottman, 1994). Amato and Rogers (1997) conceptualize that distal contextual factors and proximal interpersonal behaviors predispose couples to engage in marital discord and, ultimately, divorce. Indeed, both distal characteristics, such as prior marriage and education level (Emery, 1999), and proximal variables, like depression and substance abuse/dependence (Amato & Rogers, 1997), portend risk of divorce for married couples. Curiously, Amato and Rogers’s model (1997) did not account for the potential influence of distal or proximal child factors on risk of divorce. This is noteworthy because proximal disruptive child behavior has been shown to exacerbate proximal adult behavior linked with divorce, including stress and alcohol consumption (Pelham et al., 1997, 1998) and interparental discord (Schermerhorn, Cummings, Chow, & Goeke-Morey, 2007; Wymbs et al., 2007). Distal child variables (e.g., child age, race/ethnicity, number of offspring) have also been linked with marital dissolution (Emery, 1999). In brief, studies are sorely needed to examine the unique influence of distal/proximal parent and child variables on risk of divorce.

Another proximal parent risk factor particularly relevant for parents of children with externalizing disorders is antisocial behavior (e.g., Lahey et al., 1988). Evidence supports a hereditary link between parental antisocial personality disorder and child ADHD/ODD/CD (Faraone, Biederman, Jetton, & Tsuang, 1997; Pfiffner, McBurnett, Rathouz, & Judice, 2005), which may also represent a distal variable contributing to the risk of divorce in these families (Emery, Waldron, Kitzmann, & Aaron, 1999; Jockin, McGue, & Lykken, 1996). Since antisocial adults exhibit harmful interpersonal behaviors like aggression, which is a reliable predictor of divorce potential (Heyman, O’Leary, & Jouriles, 1995) and completion (Rogge & Bradbury, 1999), research is needed to examine the role that parental antisociality may play in exacerbating marital dissolution in families of children with ADHD.

This study sought to address the aforementioned gaps in the extant literature by: 1) Comparing the rate of divorce between parents of adolescents and young adults with and without ADHD in childhood and 2) Investigating the degree to which empirically/theoretically-relevant parent and child characteristics prospectively predict marital dissolution in these families. We hypothesized that parents of youth diagnosed with ADHD in childhood were more likely to have a shorter latency to divorce than parents of youth without ADHD. Based on Amato and Rogers (1997) conceptual model of divorce, we expected that distal (level of education, marital history) and proximal parent variables (substance abuse, depression, antisocial behavior) would uniquely predict the rate of divorce in a subset of the families of children with ADHD. Extending their model, we hypothesized that distal (age, race/ethnicity) and proximal child factors (ADHD symptom severity, ODD/CD symptom severity) would also uniquely predict the rate of divorce in the context of the distal/proximal parent risk factors.

Method

Participants

Data were gathered from parents of adolescents and young adults with and without ADHD participating in the Pittsburgh ADHD Longitudinal Study (PALS; Faden et al., 2004; Molina, Pelham, Gnagy, Thompson, & Marshal, 2007). All adolescents and young adults with ADHD (probands) in PALS were recruited from a pool of 516 adolescents and young adults who had been diagnosed with ADHD as children and attended the Summer Treatment Program (STP; Pelham, Fabiano, Gnagy, Greiner, & Hoza, 2005) conducted at the ADD Clinic at the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic (WPIC) in Pittsburgh, PA during the years from 1987–1996. Of the eligible probands, 493 were re-contacted and 364 were interviewed (70.5% participation rate) for PALS. Participating probands were compared with nonparticipating probands on demographic (e.g., age at first treatment, race/ethnicity, parental education level, and marital status) and diagnostic (e.g., parent and teacher ratings of ADHD and related symptomatology) variables. Only one of 14 comparisons was significant at the p <.05 significance level: Participants had a slightly lower average CD symptom rating.

Briefly, all probands met diagnostic criteria in childhood for DSM-III-R (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1987) or DSM-IV (APA, 1994) ADHD. Proband age at initial evaluation ranged from 5.0 to 16.9 years, with 90.0% being between the ages of 5 and 12. Diagnostic information was collected using several sources, including the parent and teacher Disruptive Behavior Disorders (DBD) Rating Scale (Pelham, Gnagy, Greenslade, & Milich, 1992) and a structured interview consisting of the DSM descriptors for ADHD, ODD, and CD, with situational and severity probes (instrument available at http://wings.buffalo.edu/adhd). Exclusionary criteria included a full scale IQ less than 80, a history of seizures or other neurological problems, and/or a history of pervasive developmental disorder, schizophrenia, or other psychotic or organic mental disorders.

Two-hundred forty demographically similar adolescents and young adults without ADHD (controls) and their parents were recruited locally from 1999–2001 to participate in PALS. Most adolescent controls were recruited through several large pediatric practices (40.8% of control sample) that serve patients from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. The remaining controls, particularly young adults, were recruited via advertisements in local newspapers and the university hospital newsletter (27.5%), local universities and colleges (20.8%), and other methods (word of mouth, etc.). A telephone screening interview administered to parents of potential controls gathered basic demographic characteristics, presence of exclusionary criteria, and a checklist of ADHD symptoms. Individuals who met DSM-III-R criteria for ADHD --either currently or historically-- were excluded. Control participants were not excluded on the basis of subthreshold ADHD or other psychiatric disorders. Controls were matched as a group to probands based on age (within one year), gender, race/ethnicity, and parent level of education.

Of note, only 282 of the 364 (77.5%) proband families and 206 of the 240 (85.8%) control families participating in PALS were eligible for the present study. Ineligible PALS families were excluded from this study for the following reasons: 1) 32 parents of probands and 11 parents of controls were never married during the life of the target child; 2) 40 proband and 16 control parents did not complete PALS follow-up measures or refused to participate in this study; and 3) 10 proband and 7 control parents were widowed. Eligible and ineligible PALS proband and control families were compared across a number of demographic variables collected at follow-up. Among the 10 demographic variables examined, only three variables differed between eligible and ineligible families: paternal level of education, maternal race/ethnicity, and child race/ethnicity. Across proband and control groups (there were no differences across diagnostic status), ineligible families tended to have fathers who reported low education levels and minority parents/children than families who were eligible for this study.

Table 1 displays demographic data gathered during the first follow-up visit for PALS proband and control families included in this study. Paternal age and race/ethnicity were not collected at follow-up because mothers tended to complete the demographics questionnaire and were only required to contribute their own age and race/ethnicity. Paternal education was collected because it was one of the demographic matching variables.

Table 1.

Demographic information for adolescents or young adults and their parents at PALS follow-up.

| Non-ADHD n=206 | ADHD n=282 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent/Young Adult | |||

| Age (M, SD) | 17.07 (3.13) | 17.73 (3.32) | <.01 |

| % Male | 88.8 | 88.3 | .94 |

| % Caucasian | 88.8 | 85.6 | .67 |

| Years Since STP (M, SD) | NA | 8.28 (2.64) | NA |

| ADHD symptoms | .23 (.27) | 1.22 (.70) | <.01 |

| ODD/CD symptoms | .32 (.35) | 1.20 (.78) | <.01 |

| Parents | |||

| Mother Age (M, SD) | 46.26 (5.40) | 46.29 (6.09) | .96 |

| % Caucasian Mothers | 91.9 | 90.7 | .92 |

| Years Married Before Birth of Child (M, SD) | 5.36 (4.01) | 4.76 (3.97) | .11 |

| Maternal Level of Education (M, SD) a | 6.94 (1.86) | 6.85 (1.68) | .60 |

| % High School Graduate or GED | 16.7 | 11.0 | - |

| % Partial College or Specialized Training | 23.2 | 28.4 | - |

| % Associates or 2-Year Degree | 8.1 | 14.4 | - |

| % College or University Graduate | 24.7 | 27.3 | - |

| % Graduate Professional Training | 27.3 | 17.8 | - |

| Paternal Level of Education (M, SD) a | 6.75 (1.92) | 6.07 (2.04) | <.01 |

| % High School Graduate or GED | 19.9 | 24.7 | - |

| % Partial College or Specialized Training | 22.5 | 25.5 | - |

| % Associates or 2-Year Degree | 7.3 | 10.2 | - |

| % College or University Graduate | 26.2 | 13.7 | - |

| % Graduate Professional Training | 23.0 | 18.0 | - |

Note. Proband diagnostic status determined in childhood.

Response Scale for level of education ranged from 1 (< 7th grade education) to 9 (Graduate professional training). 4 = High school graduate or GED; 5 = Specialized training; 6 = Partial college; 7 = Associates or 2-year degree; 8 = Standard college or university education.

The sample used for the Cox regression analyses was a subset of the ADHD sample described in Table 1 because childhood data, used as predictors in these prospective analyses (see below), were only collected from families of probands. Of the 282 families of youth with ADHD and marital outcome data, 191 (67.7%) had complete data for all child and parent family predictor variables. However, because 44 divorces occurred prior to gathering childhood data, prospective Cox regression analyses were only possible with 147 proband families, including 23 families (15.6%) who experienced divorce after baseline data collection.

Procedure

Childhood data were collected for proband families during intake assessments for the STP. As indicated in Table 1, these baseline assessments took place an average of 8 years prior to their first PALS follow-up visit. Several baseline measures were considered potential predictors of divorce in this study (see below).

The PALS follow-up protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Following collection of written informed consent, PALS youth and their parents were interviewed individually by post-baccalaureate research staff. In cases where distance prevented participant travel to WPIC, information was collected through a combination of mailed and telephone correspondence; home visits were offered as need dictated. During the first PALS follow-up assessment, parents provided their marital history, and completed measures assessing lifetime major depression, antisocial behavior, and substance abuse (see below).

Measures

Divorce history

During the first PALS follow-up visit, parents (usually mothers) indicated their current marital status and time since most recent divorce (if applicable). In the event respondents reported multiple divorces, they were asked to report when they divorced the biological parent of the adolescent or young adult in PALS.

Years of marriage between the biological parents of PALS probands or controls after the birth of the youth defined “latency to divorce” in this study. The child’s birth date, not the parent’s date of marriage, was used as the starting point to enable clear analysis of the impact of child behavior as a potential risk factor for divorce.

Distal child variables

At STP intake (on average, 8 years prior to first PALS follow-up visit), parents (usually mothers) were asked to indicate the age and race/ethnicity of the proband.

Distal parent variables

Similarly, parent respondents also reported during the baseline assessment how many years they were married to the proband’s biological parent before the birth of the proband, their own level of education, and whether they were married previously.

Proximal child variables

Severity of youth ADHD and ODD/CD in childhood was determined during the baseline assessment using the DBD rating scale (Pelham et al., 1992), which asked parents (usually mothers) and teachers to denote the frequency with which children exhibited symptoms of these disorders (0=Not at All to 3=Very Much). The maximum ratings across parent and teacher reports of ADHD and ODD/CD symptoms were identified separately for each item and averaged to create two scores, one indicating the baseline severity of ADHD and one indicating the baseline severity of ODD/CD, for each child.

Proximal parent variables

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Nonpatient Edition (SCID-I; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996) was administered to mothers and fathers during the first PALS follow-up assessment (on average, 8 years after STP intake) to assess psychiatric symptoms and diagnose disorders according to DSM-IV criteria. SCID-I utilizes an open-ended format designed to approximate the differential diagnosis of an experienced clinician during a clinical diagnostic interview. Test-retest reliability for diagnoses generated by the SCID-I are excellent (Williams et al., 1992). For the purposes of this study, a dichotomous variable (0=No, 1=Yes) was generated to indicate whether parents met diagnostic criteria established by the SCID-I for “lifetime” prevalence of major depression and substance abuse disorders. Similarly, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorder (SCID-II; First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams, & Benjamin, 1997) was administered during the first PALS follow-up visit to evaluate for lifetime prevalence of antisocial personality disorder. Given the limited number of fathers participating in PALS, mothers were asked to complete the SCID-I/II on the biological father of their child in the event the father did not complete the interviews themselves. Among the cases included in the Cox regression analyses, 78 (53.1%) included maternal reports of paternal lifetime history of antisocial behavior.

Intercorrelations were computed for the distal/proximal child and parent risk factors among data collected from families of children with ADHD eligible for the Cox regression analyses (n=147). As seen in Table 2, most correlations were less than.30. Only four correlations were greater than.30: a) maternal and paternal education (r =.33), b) maternal and paternal marital history (r =.59), c) paternal substance abuse and antisocial behavior (r =.42), and d) child ADHD and ODD/CD severity (r =.37).

Table 2.

Intercorrelations among Cox regression predictor variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Years Married | -- | |||||||||||

| 2. Maternal Education | .18* | -- | ||||||||||

| 3. Paternal Education | .09 | .33*** | -- | |||||||||

| 4. Maternal Marital History | −.16 | .14 | −.05 | -- | ||||||||

| 5. Paternal Marital History | −.19* | .09 | −.19* | .59*** | -- | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| 6. Maternal Substance Dx | −.23** | −.13 | −.03 | −.06 | .01 | -- | ||||||

| 7. Paternal Substance Dx | −.04 | −.04 | .05 | .11 | .11 | .24** | -- | |||||

| 8. Maternal Depression | −.02 | .03 | .00 | .20* | −.04 | .08 | .09 | -- | ||||

| 9. Paternal Antisocial | −.09 | .03 | .04 | .14 | .16 | .23** | .42*** | .18* | -- | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| 10. Child Age at STP | −.05 | −.09 | −.10 | −.18 | −.17* | .03 | −.11 | −.09 | .02 | -- | ||

| 11. Child Race/Ethnicity | −.19 | .06 | .08 | .03 | .05 | .03 | −.02 | −.01 | .05 | .03 | -- | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| 12. Child ADHD | −.11 | −.05 | −.14 | .02 | .02 | .08 | .08 | .13 | .04 | −.16 | .08 | -- |

| 13. Child ODD/CD | −.05 | −.03 | −.18* | .11 | .09 | .12 | .09 | .22** | .02 | −.06 | −.05 | .37*** |

Note. Sample for this correlation table is comprised only of families of children with ADHD eligible for the Cox regression analyses (n=147). Years Married = Years parents were married before birth of child; Education = Highest level of education achieved by parent (1 = < 7th grade education to 9 = Graduate professional training); Marital History (0=Not previously married, 1=Previously married); Substance Dx = Lifetime history of drug or alcohol abuse/dependence (0=No abuse/dependence, 1=History of abuse/dependence). Maternal Depression = Lifetime history of major depressive disorder (0=Never depressed, 1=History of depression); Paternal Antisocial = Lifetime history of antisocial personality disorder (0=Never antisocial, 1=History of antisocial); Child age at STP = Age of child when attending Summer Treatment Program; Child Race/Ethnicity (1=Caucasian, 2=Non-Caucasian); Child ADHD = Average Severity of ADHD symptoms derived from combined parent and teacher ratings on DBD scale (0=Not at all, 1=Just a little, 2=Pretty much, 3=Very Much) administered at STP intake; Child ODD/CD = Average Severity of ODD/CD symptoms derived from combined parent and teacher ratings on DBD scale (0=Not at all, 1=Just a little, 2=Pretty much, 3=Very Much) administered at STP intake.

p <.05;

p <.01

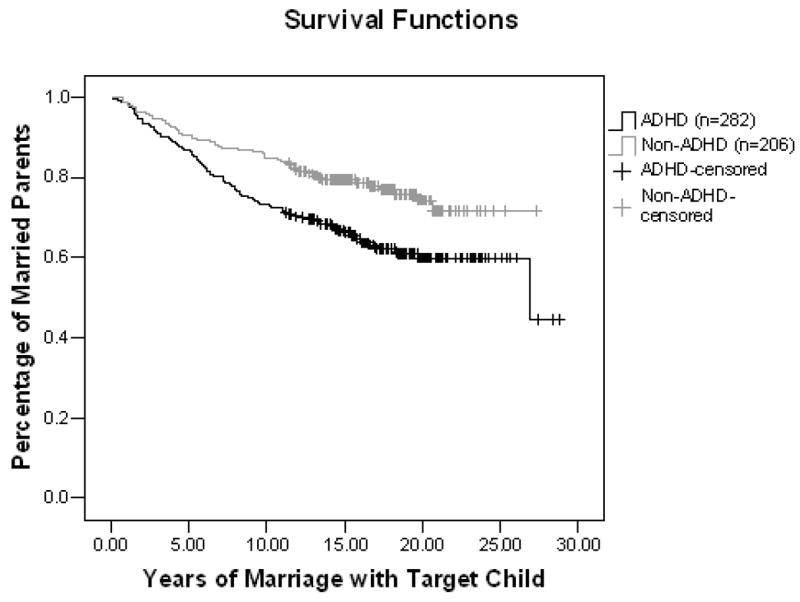

Analytical Design

Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were performed to evaluate whether the latency to divorce differed between parents of probands and controls. Survival time was considered “years of marriage with target child” (x-axis) and the occurrence of a divorce between the biological parents during the lifetime of the proband/control was considered the “critical event.” The Breslow statistic was used to test for between group differences in the latency to divorce between parents of youth with and without ADHD.

Cox regression analyses were conducted to examine the relative strength of distal/proximal child and parent risk factors towards the prediction of divorce among a subset of families of children with ADHD eligible for these analyses. Marital history, substance abuse, parent psychopathology, and child race/ethnicity variables were considered categorical when entered into the regression model. The remaining variables were entered as continuous predictors. No a priori hypotheses were specified regarding whether specific distal/proximal child and parent variables were more likely to uniquely predict divorce. Risk factors were entered as blocks into the regression equation in the following order to explore the relative strength of prediction: Distal parent, proximal parent, distal child, and proximal child.

Results

Survival analyses indicated that parents of probands have a shorter latency to divorce than parents of controls (Breslow = 10.28, p <.01; see Figure 1). Follow-up chi-square analyses revealed that the proportion of proband parents experiencing divorce (22.7%) was significantly greater than control parents (12.6%) by the time their children were 8-years-old, χ2 (488) = 8.03, p <.01. The proportion of families experiencing divorce after youth were 8-years-old did not differ between probands (15.3%) and controls (10.7%), χ2 (488) = 2.15, p =.14.

Figure 1.

Survival curves displaying latency to divorce between parents of adolescents and young adults with and without ADHD.

Next, using data from the subset of proband families eligible for Cox regression analyses (n=147), relative risk ratios (likelihood of divorce given presence of specific risk factor independent of other risk factors) were computed for the predictors of divorce. Paternal antisocial behavior evinced the largest relative risk ratio (5.53). Variables with moderate risk included maternal (2.70)/paternal (2.24) divorce history, maternal (2.37)/paternal (2.53) substance use, maternal depression (2.17), and child race/ethnicity (2.64). Risk of divorce appeared minimal for years married (1.38), maternal (.77)/paternal (.75) education, child age (.56), ADHD severity (1.32), and ODD/CD severity (1.43).

Prospective Cox regression analyses using the subset of proband families with complete childhood data (n=147) found that maternal and paternal level of education, paternal lifetime antisocial disorder, child age at STP, child race/ethnicity, and baseline child ODD/CD behavior each uniquely predicted the latency to divorce in families of probands (see Table 3). The rate of divorce increased in families with mothers who had less education, fathers with more education and antisocial behavior, and younger, racial/ethnic minority children attending the STP with elevated ODD/CD behavior problems. Years of marriage before birth of proband, maternal and paternal marital history, maternal and paternal lifetime history of substance abuse disorder, maternal lifetime history of depression, and proband ADHD behavior at baseline failed to uniquely predict rate of divorce in the regression.

Table 3.

Statistics for Cox regression model assessing prospective prediction of latency to divorce among parents of youth with ADHD.

| Distal Parent Variables a | B | SE | Wald | Hazard | CI (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years Married e | 0.01 | .08 | 0.00 | 1.01 | .86–1.17 |

| Maternal Education e | −0.67 | .26 | 6.53* | 0.52 | .31–.86 |

| Paternal Education e | 0.38 | .16 | 5.61* | 1.47 | 1.07–2.01 |

| Maternal Marital History f | 0.65 | .87 | 0.54 | 1.91 | .34–10.58 |

| Paternal Marital History f | 0.68 | .76 | 0.81 | 1.97 | .45–8.67 |

|

| |||||

| Proximal Parent Variables b | B | SE | Wald | Hazard | CI (95%) |

|

| |||||

| Maternal Substance Dx f | 0.43 | .55 | 0.61 | 1.54 | .52–4.55 |

| Paternal Substance Dx f | −0.36 | .56 | 0.43 | 0.70 | .23–2.07 |

| Maternal Depression f | 0.00 | .56 | 0.00 | 1.00 | .33–3.01 |

| Paternal Antisocial f | 2.46 | .63 | 15.15** | 11.75 | 3.40–40.61 |

|

| |||||

| Distal Child Variables c | B | SE | Wald | Hazard | CI (95%) |

|

| |||||

| Child Age at STP e | −0.44 | .14 | 9.43** | 0.64 | .49–.85 |

| Child Race/Ethnicity f | 1.85 | .67 | 7.52** | 6.34 | 1.69–23.74 |

|

| |||||

| Proximal Child Variables d | B | SE | Wald | Hazard | CI (95%) |

|

| |||||

| Child ADHD e | −0.38 | .61 | .39 | 0.68 | .21–2.26 |

| Child ODD/CD e | 1.84 | .73 | 6.27* | 6.27 | 1.49–26.36 |

Note. N= 147. Overall χ2 = 53.20, p <.01. Wald = Test of significance for Cox regression; Hazard = Odds of divorce over time; Years Married = Years parents were married before birth of child; Education = Highest level of education achieved by parent (1 = < 7th grade education to 9 = Graduate professional training); Marital History = Percentage married previously (0=Not previously married, 1=Previously married); Substance Dx = Percentage with lifetime history of drug or alcohol abuse/dependence (0=No abuse/dependence, 1=History of abuse/dependence). Maternal Depression = Percentage with lifetime history of major depressive disorder (0=Never depressed, 1=History of depression); Paternal Antisocial = Percentage with lifetime history of antisocial personality disorder (0=Never antisocial, 1=History of antisocial); Child age at STP = Age of child when attending Summer Treatment Program; Child Race/Ethnicity = Percentage of Non-Caucasian children (1=Caucasian, 2=Non-Caucasian); Child ADHD = Average Severity of ADHD symptoms derived from combined parent and teacher ratings on DBD scale (0=Not at all, 1=Just a little, 2=Pretty much, 3=Very Much) administered at STP intake; Child ODD/CD = Average Severity of ODD/CD symptoms derived from combined parent and teacher ratings on DBD scale (0=Not at all, 1=Just a little, 2=Pretty much, 3=Very Much) administered at STP intake.

χ2 Change = 12.40, p <.05

χ 2 Change = 20.65, p <.01

χ2 Change = 11.30, p <.01

χ2 Change = 6.92, p <.05

Continuous predictor

Categorical predictor

p <.05;

p <.01

Hazard ratios (likelihood of divorce given presence of specific risk factor in context of other risk factors) highlighted the clear risk of divorce between proband parents if fathers had a lifetime history of antisocial behavior (see Table 3). Hazard was also elevated for proband parents of racial/ethnic minority children and children with higher ODD/CD ratings. Of note, confidence intervals were quite large for the paternal antisocial behavior, child race/ethnicity, and child ODD/CD hazard ratios. Therefore, the reliability of the mean hazard ratios is questionable for these variables. Hazard was relatively small for the other significant predictors of latency to divorce (i.e. maternal/paternal education, child age at STP).

Post hoc analyses were conducted to examine an alternative explanation for, and otherwise explicate, the Cox regression results discussed above. First, we explored whether discrepancy in parent education levels predicted latency to divorce in lieu of the unique contribution of individual parent education levels. Parent education discrepancy was computed by subtracting the highest level of education attained by mothers from the highest level of education attained by fathers. When substituting parent education discrepancy for maternal/paternal education variables, results indicated that differences in parent education level uniquely predicted rate of divorce (B=.48, SE=.15, Wald=10.02, p <.01). Unique and nonsignificant predictors included in the remainder of the Cox regression model were no different from those reported in Table 3 when parent education was entered separately. Thus, parent education discrepancy seems to be a more parsimonious explanation for how education influences the occurrence/rate of divorce between parents of children with ADHD.

Because maternal and paternal education, paternal antisocial behavior, and child ODD/CD variables were significant predictors of divorce latency and strongly correlated with other predictor variables included in the model (r >.30; see above), another set of secondary analyses sought to rule out the effects of multicollinearity in our Cox regression analyses. Multicollinearity was tested by running a series of models with highly correlated predictors excluded one at a time. Multicollinearity was assumed to be present if the standard deviations of the point estimates for the predictors remaining in the model changed substantially in the absence of the related variable withheld from the analyses. Tests revealed that standard deviations of maternal and paternal education, paternal antisocial behavior, and child ODD/CD were undisturbed by removing correlated variables from the model, thereby suggesting that our results were not an artifact of, or influenced by, multicollinearity among the predictor variables.

Next, we explored the influence of missing data on the results of the Cox regression analyses. Predictor variables with the highest rates of missing data were maternal and paternal education (17.0% missing), maternal depression (21.8% missing), and paternal antisocial behavior (24.8% missing). While withholding maternal and paternal education from the full model, the remaining variables from the available cases (n=171) continued to significantly predict rate of divorce (e.g., paternal antisocial, child age, child race/ethnicity, and child ODD/CD were unique, statistically significant predictors at p <.05). While withholding maternal depression, the remaining variables from the available cases (n=165) continued to significantly predict latency to divorce (e.g., maternal/paternal education, paternal antisocial behavior, child age, race/ethnicity, and ODD/CD were unique, statistically significant predictors at p <.05). However, when paternal antisocial behavior was withheld from the model, results of the Cox regression analyses conducted with variables from the available cases (n=155) yielded slightly different results. Paternal education, child age and race/ethnicity still significantly predicted rate of divorce, but maternal education and child ODD/CD were no longer statistically significant predictors. Overall, it does not appear that missing data has limited conclusions drawn from the Cox regression analyses conducted with a sample including only cases with complete data.

Lastly, we submitted the original Cox regression model to a logistic regression analysis in order to investigate whether significant predictors of divorce rate would also predict the occurrence of divorce. Results of the logistic regressions indicated that paternal antisocial behavior (B = 2.43, SE =.70, Wald = 12.15, p <.01, Hazard = 11.36), non-Caucasian descent of the child (B = 1.83, SE =.84, Wald = 4.78, p <.05, Hazard = 6.21), and elevated child ODD/CD behavior ratings (B = 1.72, SE =.88, Wald = 3.86, p =.05, Hazard = 5.61) each uniquely increased risk of experiencing divorce (Overall Model χ2 (14) = 40.28, p <.01). Unlike the results of the Cox regression, only trends for statistical significance emerged for maternal/paternal education level and baseline child age. No predictors failing to uniquely predict rate of divorce in the Cox regression model significantly predicted occurrence of divorce in the logistic regression analyses. Results of the logistic regression analyses, thus, generally corroborated the findings of the Cox regression analyses.

Discussion

This is the first study to compare the durability of marriages between parents of youth with and without ADHD from birth through young adulthood. We found that married parents of youth diagnosed with ADHD in childhood demonstrated a shorter latency to divorce than parents of children without ADHD. Prospective analyses with a subset of families of youth with ADHD displayed that child age at referral, race/ethnicity, and ODD/CD symptom severity, as well as maternal/paternal education and paternal antisocial behavior uniquely predict latency to divorce.

Parents of youth diagnosed with ADHD in childhood (22.7%) were more likely to divorce by the time their children were eight-years-old than parents of youth without ADHD (12.6%). These results are similar to findings of Barkley and colleagues (1990), who reported that mothers of youth with ADHD were three-times more likely to separate or divorce from the fathers of their children than mothers of youth without ADHD. Yet, these findings extend the work of Barkley et al. and others (Brown & Pacini, 1989; Faraone et al., 1991; Jensen et al., 1988) by demonstrating that parents of clinic-referred children with ADHD are not only more likely to divorce, but also display a shorter latency to divorce than parents of children without ADHD. Since parents of youth with ADHD are likely to dissolve marriages more quickly than parents of youth without ADHD, children with ADHD are at greater risk for poor outcomes upon enduring the deleterious sequalae of divorce upon at an earlier age (Amato, 2000; Emery, 1999).

Certainly, our data should not be interpreted to suggest that having a child diagnosed with ADHD is the only risk factor for marital dissolution in these families. Rather, disruptive child behavior likely interacts over time with additional family stressors to spark marital conflict and ultimately divorce. Surprisingly, only one study (Devine & Forehand, 1996) has prospectively studied the impact of both youth and parent variables toward the prediction of divorce. Devine and Forehand found, somewhat unexpectedly, that adolescent conduct problems and anxious-withdrawn behavior did not contribute to the prediction of parental divorce. Adding to the extant literature, we compared the relative and unique strength of distal/proximal child and parent variables as predictors of latency to divorce in a subset of families of youth diagnosed with ADHD in childhood. Prospective analyses revealed that lower maternal education level, higher paternal education and antisocial behavior, young child age at referral, racially/ethnically-diverse children, and elevated child ODD/CD behavior ratings each uniquely increased risk of divorce between parents of youth diagnosed with ADHD in childhood.

We believe this is the first study to find that both parent and child variables uniquely predict the occurrence and rate of divorce. Moreover, this is the only study to demonstrate that severity of disruptive child behavior (sp. ODD/CD) increases risk of marital dissolution. Externalizing child behavior has been causally-linked with factors associated with divorce, such as marital discord (e.g., Wymbs et al., 2007) as well as parental stress and alcohol consumption (Pelham et al., 1997, 1998). Yet, we found no studies across the divorce literature reporting that proximal child factors account for variance beyond distal/proximal parent factors towards the prediction of marital dissolution. It was surprising that child ADHD symptom severity failed to predict the occurrence or rate of divorce in our sample of families of youth diagnosed with ADHD in childhood. Given the clinic-referred, treatment-seeking nature of the sample, the lack of variability among the pre-treatment ADHD ratings may have prevented this variable from contributing to risk of divorce in our analyses. Alternatively, perhaps children with ADHD and severe ODD/CD are indicators for families having significant difficulty resolving interpersonal conflicts. Indeed, parents of children with ADHD and comorbid ODD/CD tend to engage in more frequent acts of overt interparental conflict and use more negative verbalizations during childrearing discussions than parents of children without ADHD (e.g., Lindahl, 1998; Wymbs et al., 2008). Studies are needed to replicate these analyses with a community sample of children with and without ADHD in order to allow for an investigation of mediating factors (e.g., parent-child conflict) prospectively linking proximal child variables (e.g., ADHD and ODD/CD symptom severity) with marital discord and divorce.

Child age and race/ethnicity also prospectively predicted divorce in our subset of families of youth with ADHD. Specifically, married parents of young or non-Caucasian children with ADHD were more likely to divorce and have a shorter latency to divorce than parents of old or Caucasian children with ADHD. These distal child variables may be proxies for more common precipitants of divorce: racial/ethnic-minority parents and marital distress. Adults in racial/ethnic minority groups are less likely to initiate and sustain marriages than Caucasian adults (Emery, 1999). Further, given the common decline in marital satisfaction upon the start of childrearing, marriages are more at-risk to end early in a child’s life than later (Emery, 1999). Because paternal race/ethnicity or marital satisfaction data from couples was not collected at baseline, we were unable to test whether these variables indeed uniquely predicted latency to divorce. Future work examining predictors of divorce in families of children with ADHD should account for parent race/ethnicity and marital satisfaction in their prospective models.

Similar to reviews of non-referred populations (Emery, 1999), parent education level predicted divorce in our sample of married parents of children with ADHD. Curiously, the direction of the association between parent education and occurrence/rate of divorce differed by parent gender, such that marital dissolution occurred more frequently and quickly with less educated mothers or more educated fathers. Since divorce is more common among undereducated adults (Emery, 1999), finding that elevated paternal education levels increased risk of divorce was unusual. Secondary analyses revealed that couples with more discrepant levels of education were more likely to experience divorce than couples with more similar education levels. We are aware of only one other study that investigated whether differences in educational attainment between spouses forecasts marital dissolution. Using a national sample of non-referred adults, Weiss and Willis (1997) discovered that couples with similar levels of schooling at the time of marriage were less likely to divorce. Therefore, our results suggesting that spousal education difference uniquely predicts the likelihood of divorce in families of youth with ADHD is consistent with the available research.

This study also replicated the findings of Lahey and colleagues (1988), who reported that divorce between parents of children with disruptive behavior disorders was associated with parental antisocial behavior. Indeed, relative risk and hazard ratios indicated that married parents of youth with ADHD in this study were much more likely to eventually divorce if the father evinced a lifetime history of antisocial personality disorder. The relative weight of this variable was notable given that additional risk factors in the regression model commonly associated with marital dissolution and antisocial behavior (e.g., history of divorce, paternal substance abuse, maternal depression) failed to significantly predict rate of divorce in the context of paternal antisocial behavior. Secondary analyses displaying how proximal child risk factors (sp. ODD/CD severity) only predict rate of divorce when considered in the context of paternal antisociality also underscore the relative importance of paternal antisocial behavior in models of divorce. Work is needed to test potential mechanisms (e.g., genetics) linking paternal antisociality and marital dissolution in families of children with ADHD.

The generalizability of results discussed above is limited for a number of reasons. Given the composition of our sample, findings may not be relevant to those other than families of college-educated, Caucasian parents with male children. Similarly, results of the Cox regression analyses presented herein may not be meaningful for parents of children with ADHD who are undiagnosed or untreated in childhood or for parents of children with ADHD who divorce early. It is also difficult to disentangle whether elevated rates of divorce in the ADHD families in this study is unique to ADHD or clinic-referred families in general. Still, at least one study indicates marital dissolution is more commonly associated in families of youth with conduct disorder than families of youth with anxiety or depressive disorders (Fendrich, Warner, & Weissman, 1990). Confidence intervals for several hazard ratios, particularly paternal antisocial behavior, child race/ethnicity, and child ODD/CD severity, were quite large. As such, caution should be taken before relying on the mean hazard ratios presented for these variables. A subset of the paternal antisocial behavior ratings were completed by mothers, thus potentially confounding the outcome of the regression analyses, particularly among mothers who divorced their child’s father. Although theoretically and empirically justified, only two child and four parent psychopathology variables were entered as proximal predictors of divorce. Additional forms of child (e.g., internalizing symptoms; Stroehschein, 2005) and parent (e.g., anxiety, ADHD; Robin & Payson, 2002; Yoon & Zinbarg, 2007) psychopathology may influence the longitudinal course of marriages between parents of children with ADHD. Relatedly, additional distal child (e.g., IQ) and parent (e.g., attitude toward divorce) factors not included in our model may also contribute to risk of divorce. Last, although careful training of research staff prepared them for conducting clinical interviews, inter-rater reliability data were unavailable when this manuscript was prepared. Thus, some error may be present among these data.

Despite these limitations, our findings demonstrate the likelihood of divorce among married parents of youth diagnosed with ADHD in childhood. These data are concerning in light of evidence underscoring the generally negative consequences of divorce for both children and adults (Amato, 2000). Clearly, studies are needed to investigate means to broaden the therapeutic effect of evidence-based treatments for ADHD in order to enhance marital stability in these families (Chronis, Chacko, Fabiano, Wymbs, & Pelham, 2004). One promising direction is to evaluate the efficacy of relationship distress/divorce prevention programming for parent couples of youth with ADHD. Relationship distress and divorce prevention protocols have a substantial evidence base in non-referred populations (Halford, Markman, Kline, & Stanley, 2003), including demonstrations of longitudinal maintenance (e.g., Markman, Renick, Floyd, Stanley, & Clements, 1993). Given the benefits of brief marital therapy for distressed couples of children with ODD/CD receiving behavioral parent training (e.g., Dadds, Schwartz, & Sanders, 1987), relationship distress/divorce prevention programs delivered as an adjunctive treatment for married parents of young children with ADHD may improve long-term marital relations and child outcomes in these families. Furthermore, in light of evidence underscoring the likelihood of children being prescribed stimulant medication around the time of parental divorce (Strohschein, 2007), implementing relationship distress/divorce prevention programming in conjunction with behavioral parent training may also reduce the need for children with ADHD and disruptive behavior disorders to take medication unnecessarily.

Taken together, this study brings to light the susceptibility to divorce of married parents of youth diagnosed with ADHD. It is important to note, however, that marital dissolution is not always harmful to those involved. In fact, most children—especially those whose parents no longer engage in intense conflict—are resilient (Kelly & Emery, 2003). Unfortunately, children exhibiting chronic behavior problems prior to divorce are likely to react poorly to marital dissolution (Hetherington & Stanley-Hagan, 1999). With this in mind, clinicians and researchers treating children with ADHD and disruptive behavior disorders should routinely assess marital functioning between their parents and, if need be, intervene with discordant parents in order to prevent these children from experiencing the negative effects of divorce. On the other hand, because divorce may promote better outcomes for children than those who continue to witness frequent, intense, and unresolved marital conflict, particularly regarding childrearing issues (Cummings & Davies, 1994; Emery, 1999), marital dissolution may be an appropriate outcome for highly distressed couples raising difficult-to-manage children.

Contributor Information

Brooke S. G. Molina, University of Pittsburgh

Elizabeth M. Gnagy, University at Buffalo, State University of New York

Tracey K. Wilson, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

Joel B. Greenhouse, Carnegie Mellon University

References

- Amato PR. The consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:1269–1287. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Rogers SJ. A longitudinal study of marital problems and subsequent divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1997;59:612–624. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3 Revised. Washington, DC: Author; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Anastopoulos AD, Guevremont DC, Fletcher KE. Adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Mother-adolescent interactions, family beliefs and conflicts, maternal psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1992;20:263–287. doi: 10.1007/BF00916692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Edelbrock C, Smallish L. The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children diagnosed by research criteria: I. An 8-year prospective follow-up study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1990;29:546–557. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199007000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Edelbrock C, Smallish L. The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children diagnosed by research criteria—III. Mother-child interactions, family conflicts and maternal psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1991;32:233–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RT, Pacini JN. Perceived family functioning, marital status, and depression in parents of boys with attention deficit disorder. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 1989;22:581–587. doi: 10.1177/002221948902200911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis AM, Chacko A, Fabiano GA, Wymbs BT, Pelham WE. Enhancements to the behavioral parent training paradigm for families of children with ADHD: Review and future directions. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2004;7:1–27. doi: 10.1023/b:ccfp.0000020190.60808.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counts CA, Nigg JT, Stawicki JA, Rappley MD, Von Eye A. Family adversity in DSM-IV ADHD combined and inattentive subtypes and associated disruptive behavior problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:690–698. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000162582.87710.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Children and Marital Conflict: The Impact of Family Dispute and Resolution. New York: The Guilford Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Schwartz S, Sanders MR. Marital discord and treatment outcome in behavioral treatment of child behavior problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:396–403. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.3.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine D, Forehand R. Cascading toward divorce: The roles of marital and child factors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:424–427. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE. Marriage, Divorce, and Children’s Adjustment. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE, Waldron M, Kitzmann KM, Aaron J. Delinquent behavior, future divorce or nonmarital childbearing, and externalizing behavior among offspring: A 14-year prospective study. Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13:568–579. [Google Scholar]

- Faden VB, Day NL, Windle M, Windle R, Grube JW, Molina BSG, Pelham WE, Jr, Gnagy EM, Wilson TK, Jackson KM, Sher KJ. Collecting longitudinal data through childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood: Methodological challenges. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:330–340. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000113411.33088.fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Keenan K, Tsuang MT. Separation of DSM-III attention deficit disorder and conduct disorder: Evidence from a family-genetic study of American child psychiatric patients. Psychological Medicine. 1991;21:109–121. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700014707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Jetton JG, Tsuang MT. Attention deficit disorder and conduct disorder: Longitudinal evidence for a familial subtype. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:291–300. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendrich M, Warner V, Weissman MM. Family risk factors, parental depression, and psychopathology in offspring. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:40–50. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders--Non-patient Edition (SCID-I/NP, Version 2.0) Biometrics Research Department; New York State Psychiatric Institute: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Benjamin LS. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders. American Psychiatric Publishing Inc; Arlington, VA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM. What Predicts Divorce? The Relationship between Marital Processes and Marital Outcomes. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Coan J, Carrere S, Swanson C. Predicting marital happiness and stability from newlywed interactions. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Levenson RW. Marital processes predictive of later dissolution: Behavior, physiology, and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:221–233. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford WK, Markman HJ, Kline GH, Stanley SM. Best practice in couple relationship education. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2003;29:385–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb01214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Stanley-Hagan M. The adjustment of children with divorced parents: A risk and resiliency perspective. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:129–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, Hunt AN. Replication in observational couples research: A commentary. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2007;69:81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, O’Leary KD, Jouriles EN. Alcohol and aggressive personality styles: Potentiators of serious physical aggression against wives? Journal of Family Psychology. 1995;9:44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, Slep AMS. The hazards of predicting divorce without crossvalidation. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2001;63:473–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PS, Shervette RE, Xenakis SN, Bain MW. Psychosocial and medical histories of stimulant-treated children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1988;27:798–801. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198811000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jockin V, McGue M, Lykken DT. Personality and divorce: A genetic analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:288–299. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.2.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C, Behrenz K. Childrearing discussions in families of nonproblem children and ADHD children with higher and lower levels of aggressive-defiant behavior. Canadian Journal of School Psychology. 1993;9:53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C, Mash EJ. Families of children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Review and recommendations for future research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2001;4:183–207. doi: 10.1023/a:1017592030434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JR, Emery RE. Children’s adjustment following divorce: Risk and resilience perspectives. Family Relations. 2003;52:352–362. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Hartdagen SE, Frick PJ, McBurnett K, Conner R, Hynd GW. Conduct disorder: Parsing the confounded relation to parental divorce and antisocial personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:334–337. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl KM. Family process variables and children’s disruptive behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12:420–436. [Google Scholar]

- Markman HJ, Renick MJ, Floyd FJ, Stanley SM, Clements M. Preventing marital distress through communication and conflict management training: A 4- and 5-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:70–77. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee R, Williams S, Silva PA. Background characteristics of aggressive, hyperactive, and aggressive-hyperactive boys. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1984;23:280–284. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60503-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minde K, Eakin L, Hechtman L, Ochs E, Bouffard R, Greenfield B, Looper K. The psychosocial functioning of children and spouses of adults with ADHD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:637–646. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BSG, Pelham WE, Jr, Gnagy EM, Thompson AL, Marshal MP. ADHD risk for heavy drinking and alcohol use disorder is age-specific in adolescence and young adulthood. Alcoholism: Experimental and Clinical Research. 2007;31:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00349.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Fabiano GA, Gnagy EM, Greiner AR, Hoza B. The role of summer treatment programs in the context of comprehensive psychosocial treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In: Hibbs E, Jensen P, editors. Psychosocial Treatments for Child and Adolescent Disorders: Empirically Based Strategies for Clinical Practice. 2. Washington, DC: APA; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Gnagy EM, Greenslade KE, Milich R. Teacher ratings of DSM-III-R symptoms for the disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31:210–218. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Lang AR, Atkeson B, Murphy DA, Gnagy EM, Greiner AR, Vodde-Hamilton M, Greenslade KE. Effects of deviant child behavior on parental distress and alcohol consumption in laboratory interactions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25:413–424. doi: 10.1023/a:1025789108958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Lang AR, Atkeson B, Murphy DA, Gnagy EM, Greiner AR, Vodde-Hamilton M, Greenslade KE. Effects of deviant child behavior on parental alcohol consumption: Stress-induced drinking in parents of ADHD children. The American Journal on Addictions. 1998;7:103–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfiffner LJ, McBurnett K, Rathouz PJ, Judice S. Family correlates of oppositional and conduct disorders in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:551–563. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-6737-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin AL, Payson E. The impact of ADHD on marriage. The ADHD Report. 2002;10:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Rogge RD, Bradbury TN. Till violence does us part: The differing roles of communication and aggression in predicting adverse marital outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:340–351. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogge RD, Bradbury TN, Hahlweg K, Engl J, Thurmaier F. Predicting marital distress and dissolution: Refining the two-factor hypothesis. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:156–159. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachar RJ, Wachsmuth R. Family dysfunction and psychosocial adversity: Comparison of attention deficit disorder, conduct disorder, normal, and clinical controls. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 1991;23:332–348. [Google Scholar]

- Schermerhorn AC, Cummings EM, DeCarlo CA, Davies PT. Children’s influence in the marital relationship. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:259–269. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohschein LA. Parental divorce and child mental health trajectories. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:1286–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Strohschein LA. Prevalence of methylphenidate use among Canadian children following parental divorce. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2007;176:1711–1714. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss Y, Willis RJ. Match quality, new information, and marital dissolution. Journal of Labor Economics. 1997;15:S293–S329. doi: 10.1086/209864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB, Spitzer RL, Davies M, Borus J, Jowes MJ, Kane J, Pope HG, Jr, Rounsaville BJ, Wittchen HU. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) II: Multi-site test-retest reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49:630–636. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080038006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wymbs BT, Carducci C, DiLorenzo R, McClure P, Snow D, Tong P, Carter N, Valin S, Pelham WE. Do Disruptive Children Cause Interparental Discord? Results of Observational Coding; 2007, August; Poster presented at the annual conference of the American Psychological Association; San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Wymbs BT, Pelham WE, Gnagy EM, Molina BSG. Mother and adolescent reports of interparental discord among families of adolescents with and without attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2008;16:29–41. doi: 10.1177/1063426607310849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon KL, Zinbarg RE. Generalized anxiety disorder and entry into marriage or a marriage-like relationship. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2007;21:955–965. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]