Abstract

Several neurological diseases, including Parkinson disease and dementia with Lewy bodies, are characterized by the accumulation of α-synuclein phosphorylated at Ser-129 (p-Ser-129). The kinase or kinases responsible for this phosphorylation have been the subject of intense investigation. Here we submit evidence that polo-like kinase 2 (PLK2, also known as serum-inducible kinase or SNK) is a principle contributor to α-synuclein phosphorylation at Ser-129 in neurons. PLK2 directly phosphorylates α-synuclein at Ser-129 in an in vitro biochemical assay. Inhibitors of PLK kinases inhibited α-synuclein phosphorylation both in primary cortical cell cultures and in mouse brain in vivo. Finally, specific knockdown of PLK2 expression by transduction with short hairpin RNA constructs or by knock-out of the plk2 gene reduced p-Ser-129 levels. These results indicate that PLK2 plays a critical role in α-synuclein phosphorylation in central nervous system.

The importance of α-synuclein to the pathogenesis of Parkinson disease (PD)4 and the related disorder, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), is suggested by its association with Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites, the inclusions that characterize these diseases (1–3), and demonstrated by the existence of mutations that cause syndromes mimicking sporadic PD and DLB (4–6). Furthermore, three separate mutations cause early onset forms of PD and DLB. It is particularly telling that duplications or triplications of the gene (7–9), which increase levels of α-synuclein with no alteration in sequence, also cause PD or DLB.

α-Synuclein has been reported to be phosphorylated on serine residues, at Ser-87 and Ser-129 (10), although to date only the Ser-129 phosphorylation has been identified in the central nervous system (11, 12). Phosphorylation at tyrosine residues has been observed by some investigators (13, 14) but not by others (10–12). Phosphorylation at Ser-129 (p-Ser-129) is of particular interest because the majority of synuclein in Lewy bodies contains this modification (15). In addition, p-Ser-129 was found to be the most extensive and consistent modification in a survey of synuclein in Lewy bodies (11). Results have been mixed from studies investigating the function of phosphorylation using S129A and S129D mutations to respectively block and mimic the modification. Although the phosphorylation mimic was associated with pathology in studies in Drosophila (16) and in transgenic mouse models (17, 18), studies using adeno-associated virus vectors to overexpress α-synuclein in rat substantia nigra found an exacerbation of pathology with the S129A mutation, whereas the S129D mutation was benign, if not protective (19). Interpretation of these studies is complicated by a recent study showing that the S129D and S129A mutations themselves have effects on the aggregation properties of α-synuclein independent of their effects on phosphorylation, with the S129A mutation stimulating fibril formation (20). Clearly, determination of the role of p-Ser-129 phosphorylation would be helped by identification of the responsible kinase. In addition, identification will provide a pathologically relevant way to increase phosphorylation in a cell or animal model.

Several kinases have been proposed to phosphorylate α-synuclein, including casein kinases 1 and 2 (10, 12, 21) and members of the G-protein-coupled receptor kinase family (22). In this report, we offer evidence that a member of the polo-like kinase (PLK) family, PLK2 (or serum-inducible kinase, SNK), functions as an α-synuclein kinase. The ability of PLK2 to directly phosphorylate α-synuclein at Ser-129 is established by overexpression in cell culture and by in vitro reaction with the purified kinase. We show that PLK2 phosphorylates α-synuclein in cells, including primary neuronal cultures, using a series of kinase inhibitors as well as inhibition of expression with RNA interference. In addition, inhibitor and knock-out studies in mouse brain support a role for PLK2 as an α-synuclein kinase in vivo.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Kinase Assays—To prepare biotinylated α-synuclein substrate, a cysteine residue was introduced into the C terminus (141C-αSyn) of the recombinant α-synuclein expression construct previously described (11), using site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange XL, Stratagene), and the resulting α-synuclein mutant was prepared (11). The C-terminal cysteine was biotinylated with maleimide-polyethylene glycol 2-biotin (Pierce). PLK1, -2, -3, and -4 (Carna Biosciences) or CK 2 (New England Biolabs) were mixed with 66 nm biotin-141C-α-synuclein (33 nm) and 0.2 mm phospholipid vesicles (75% soybean phosphatidylcholine (Sigma Aldrich), 25% 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sre-glycero-3-phosphate (Avanti Polar Lipids) in buffer A (25 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 2 mm dithiothreitol, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin). The kinase reaction was started by adding an equal volume of buffer B (25 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 2 mm dithiothreitol, 0.2 mm ATP, 0.2 mm MgCl2) and incubated at 30 °C for 30 min. Europium cryptate-labeled p-Ser-129-specific11A5 antibody (2 nm) and streptavidin-allophycocyanin (7.5 nm) were added in the same reaction volume of buffer C (25 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 0.8 m KF, 66 nm EDTA, 0.1% bovine serum albumin), and fluorescence intensity was measured. Uniform phosphorylation of the p-Ser-129 α-synuclein standard was confirmed by reverse phase-high pressure liquid chromatography and mass spectroscopy. The p-Ser-129 α-synuclein standard curve was obtained under the same conditions as for measurement of assay samples, without kinase. Unphosphorylated α-synuclein was added to keep the total synuclein constant at 33 nm. For inhibitor studies, compounds were serially diluted in buffer B, with a PLK2 concentration of 0.3 nm.

Targeted Gene Disruption and Generation of Plk2–/– Mice—plk2–/– mice were prepared by Caliper Life Sciences. A plk2 targeting construct was designed to replace all 14 plk2 exons (deletion between sequences 5′-CAGCCAGCCGGCGCGTATTTAAAGC-3′ and 5′-AGCACGGGTTCCTGACACGTCAG-3′) with a Neo cassette (targeting vector FtNwCD, Caliper Life Sciences). This targeting construct was used to disrupt the plk2 gene in C57BL6 embryonic stem cells. These embryonic stem cells were injected into blastocysts and implanted into pseudo-pregnant females. Resulting germ line chimeras were crossed to C57BL/6N Tac mice, and heterozygous offspring were intercrossed to produce PLK2-null animals. Similar to a previous report (23), few live plk2–/– homozygous offspring were observed. Mice were genotyped by PCR using the following primers: 5′-CTGTGCTCGACGTTGTCACTG-3′ and 5′-GATCCCCTCAGAAGAACTCGT-3′ for the disrupted allele and 5′-CTTGCTCGTACTCATCACGGCA-3′ and 5′-AACCTAGTCACTTAGCAATGCCAGGT-3′ for the wild-type allele.

Preparation of Lentiviral Constructs—The lentiviral plasmid designated pAGMK was generated by modifying the parent lentiviral plasmid pCSC-SP-PW-GFP1 (24) as described in the supplemental materials. The cDNA coding for α-synuclein or α-synuclein (E46K) was cloned into pAGMK to replace green fluorescent protein, using the AgeI/PmeI sites. The Plk2 short hairpin RNA (shRNA) containing plasmid (TRCN0000000869, CCGGGTGACGGTGCTGAAATACTTTCTCGAGAAAGTATTTCAGCACCGTCACTTTTT) was obtained from Sigma. The procedures for lentivirus production are described in the supplemental materials. After the total RNA was isolated, the efficiency of mRNA knockdown by shRNA was determined by TaqMan quantitative RT-PCR with the Applied Biosystems Gene-Assay kit using the protocol provided by the supplier. The relative copy number of PLK2 mRNA in the cellular extract was calculated after normalization to a housekeeping mRNA, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Cortical Cultures from PLK2 Knock-out Mice—Embryonic day 15 embryos were obtained from heterozygous PLK2 knockout crossed C57Bl6 mice (International Animal Care and Use Convention (IACUC) protocol MO-PH-05-08). Each embryo was placed in a distinct Petri dish for subsequent genotyping analysis as described above. Cultures, at least 95% neuronal, were prepared as described by Wright et al. (25). After 14 days in culture, cells were washed in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and lysed in ice-cold cell extraction buffer (CEB; 10 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm NaF, 20 mm Na2P2O7, 2 mm Na3VO4, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholate). Plates were snap-frozen on dry ice and stored at –80 °C. Duplicate plates from each culture were harvested for qRT-PCR as detailed below. RNA was extracted from samples and purified using the Qiagen RNeasy 96 kit according to the Qiagen protocol.

Transfection of HEK293 Cells—HEK293 cells were co-transfected with pAGMK-α-synuclein (wild type), along with either pCMV6-XL4 empty vector or pCMV6-XL4 vector containing PLK2 (OriGene Technologies, Rockville, MD). Cells were plated at a density of 4,000 cells/well into poly-d-lysine-coated 96-well plates. The following day, growth medium was replaced with 293 medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, 10% fetal bovine serum, 20 mm glutamine, 1 mm sodium pyruvate), and cDNAs were incubated at room temperature with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) for 15 min prior to transfection with 100 nm siRNA and Lipofectamine 2000 per well following the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were washed in cold phosphate-buffered saline 48 h after transfection and then harvested in CEB. Plates were snap-frozen on dry ice and stored at –80 °C.

Compound Treatment of Swiss-Webster Cortical Cultures and of Transfected HEK293 Cells—Mouse cortical cultures were prepared as described above from embryonic day 15 Swiss-Webster embryos, except that the embryonic cortices were pooled. Cells were maintained for 14 days prior to inhibitor treatment. Transfected HEK293 cells were prepared as described above. The following inhibitors were diluted into medium, and cells were treated for 2 h: BI2536, N-[4-(4-aminothieno[2,3-d]pyrimidin-5-yl)phenyl]-N′-(3-methylphenyl)urea (APMU), and 2-dimethylamino-4,5,6,7-tetrabromo-1H-benzimidazole (DMAT; Calbiochem). After 2 h, cells were washed and lysed as described above.

In Vivo Experiments—Female 9-week-old FVB/N mice (20–26 g each) were purchased from Taconic. All experiments were approved by the IACUC of Elan Pharmaceuticals and conducted in accordance with its guidelines. Drug administration was by intravenous tail vein injection with one 30 mg/kg dose of BI2536 or vehicle at a 5 ml/kg dose volume in 0.9% saline. Animals were euthanized by carbon dioxide 3 h after dosing. Brains were removed, rinsed in 0.9% saline, and separated into left and right hemispheres. The cortex was dissected from the right hemisphere, frozen on dry ice, and kept at –80 °C until used for quantitation of α-synuclein levels.

ELISA Assay—Protein concentration of lysates was measured using the Micro BCA Kit (Pierce Biotechnology). Total α-synuclein and p-Ser-129 α-synuclein levels were each normalized to the total protein measured in each lysate, and a ratio of phosphorylated synuclein to total synuclein was calculated. Total and p-Ser-129 α-synuclein levels were quantified by sandwich ELISA using 1H7 as the capture antibody and biotinylated 5C12 or biotinylated 11A5 as the total or phosphosynuclein reporter antibodies as described (11) with the exception that cells were lysed in CEB instead of guanidine, and Costar EIA/RIA high binding 96-well plates (Corning) were used.

qRT-PCR Analysis of PLK2 Knock-out Mouse Cortical Cultures—cDNA from mouse cortical culture RNA was made using the SuperScript II first-strand synthesis system from Invitrogen. Gene expression assays from Applied Biosystems containing fluorogenic quantitative PCR primer/probe sets were obtained for mouse PLK2. Each cDNA was added to the qPCR master mix containing Applied Biosystems TaqMan universal PCR master with uracil N-glycosylase and ROX reference dye, 900 nm each of the forward and reverse primer, and 200 nm of the fluorogenic probe. qRT-PCR was carried out using one cycle of 50 °C, 2 min, 95 °C, 2 min and 40 cycles of 95 °C, 15 s and 60 °C, 1 min. For each well, the relative copy number of the gene of interest was normalized to total RNA as measured by the RiboGreen 96-well kit (Invitrogen).

RESULTS

To identify potential α-synuclein kinases, we screened HEK293 cells overexpressing α-synuclein for reduction of the p-Ser-129 modification, using the Ambion Silencer kinase siRNA library (Applied Biosystems). Such knockdown approaches have the advantage of avoiding artificial activity resulting from overexpression. Several kinases whose reduction decreased synuclein phosphorylation were identified (26). Of the candidate kinases, PLK2 was of particular interest because the siRNAs against this enzyme provided the largest and most consistent decrease in α-synuclein phosphorylation. Importantly, PLK2, as well as the closely related PLK3, are expressed in brain (27, 28).

PLK Family Members Directly Phosphorylate α-Synuclein—To confirm that PLK2 can directly phosphorylate α-synuclein, we examined the proteins in vitro. PLK2 was compared with the other members of the PLK family, as well as CK2, which has been previously shown to phosphorylate α-synuclein (10). Phosphorylation at Ser-129 was measured with a fluorescence assay using an antibody specific for phosphorylation at this residue (11); no other phosphorylation was observed by mass spectroscopy. PLK2 and -3 efficiently phosphorylated α-synuclein (Fig. 1A), with results consistent with complete phosphorylation of the 33 nm synuclein substrate (compare with the 33 nm p-Ser-129 (pS129) standard, Fig. 1A, inset). PLK1 had lower activity, comparable with that of CK2. To ensure that all enzymes were active, their abilities to phosphorylate another substrate, casein, were verified (supplemental Fig. S1). PLK4 had no measurable activity against either substrate but was able to autophosphorylate, suggesting that both casein and synuclein may be poor substrates for this enzyme.

FIGURE 1.

Phosphorylation of α-synuclein Ser-129 by PLK2. A, phosphorylation of a biotinylated α-synuclein substrate by recombinant PLK1 (▪), PLK2 (•), PLK3 (⋄), PLK4 (□), and CK2 (○). Phosphorylation of the substrate at Ser-129 was measured using a phosphorylation-specific antibody with the kinase assay described under “Experimental Procedures.” Acceptor/donor ratio (A/D ratio) is a ratio of acceptor and donor fluorescence intensities. Inset, acceptor/donor ratios of the p-Ser-129 (pS129) synuclein standard. B and C, reduction of PLK2 mRNA (B) and p-Ser-129 α-synuclein (C) by lentiviral constructs either containing a scrambled sequence (Control) or expressing PLK2 shRNA, in human cortical cultures overexpressing α-synuclein (E46K mutant). The relative multiplicity of infection (MOI) is shown. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. Relative copy numbers (copy#) of PLK2 mRNA were determined by qPCR (“Experimental Procedures”) and normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA. Ratios of p-Ser-129 to total α-synuclein were determined by ELISA.

Inhibition or Reduction of PLK2 Decreases α-Synuclein Phosphorylation—To establish the role of PLK2 in neurons, the effect of knockdown of PLK2 levels in human cortical cultures was investigated using shRNA in lentiviral vectors. As shown in Fig. 1, B and C, transduction with the PLK2 shRNA vectors caused substantial reduction of PLK2 message levels (by as much as 64%) and a parallel reduction of p-Ser-129 α-synuclein (as much as 78%). No effect was observed on PLK3 mRNA or total α-synuclein levels, and there was no cellular toxicity detected by Alamar Blue assay, suggesting that the effect on phospho-α-synuclein was mediated by specific mRNA silencing (data not shown).

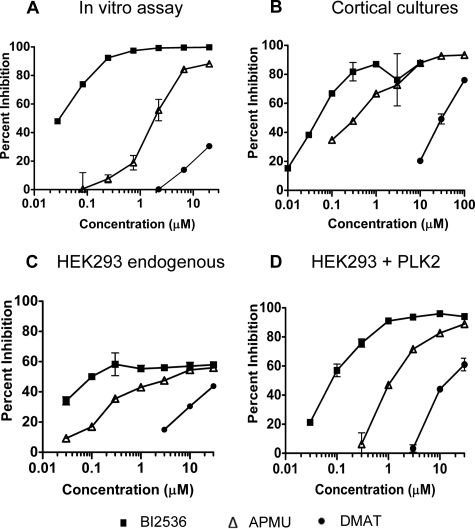

We have compared the potency of selected kinase inhibitors against PLK2 in mouse primary cortical cultures with their potency in the biochemical PLK2 assay. Many of the studies investigating CK2 as an α-synuclein kinase have used the inhibitor DMAT. We also find that DMAT inhibits α-synuclein phosphorylation in mouse cortical cultures, with an EC50 around 30 μm. However, it also inhibits PLK2 in the biochemical assay (Fig. 2, A and B). APMU (compound 3 in Johnson et al. (29)), which has good activity against PLK2 and -3 but is inactive against PLK1, inhibited α-synuclein phosphorylation in mouse cortical cultures. These results, together with the lower activity for PLK1 (Fig. 1A), suggest a limited role, if any, for PLK1 as an α-synuclein kinase. BI2536 has high potency and specificity for PLK family kinases (30) (see profiling results in supplemental Table S1). This compound inhibited up to 85–90% of α-synuclein phosphorylation in the cortical cultures, with an EC50 in multiple assays of 50–100 nm.

FIGURE 2.

Reduction of p-Ser-129 α-synuclein by inhibition of PLK2. A–D, inhibition of α-synuclein phosphorylation by BI2536 (▪), AMPU (▵), or DMAT (•) by recombinant PLK2 in the in vitro kinase assay (A), in mouse cortical cultures (B), and in HEK293 cells by endogenous kinase (transfected with empty vector) (C) or by transfected PLK2 (D). Levels of p-Ser-129 α-synuclein were measured by in vitro kinase assay (A) or by ELISA (B–D); the percentage of inhibition relative to controls with DMSO vehicle alone is shown.

Because comparison of inhibitor potencies in cells and in vitro can be complicated by the ability of cells to exclude or accumulate different inhibitors, we compared the potency of inhibitors in HEK293 cells transfected with PLK2 (Fig. 2C) or with vector controls (endogenous HEK293 cell kinases only, Fig. 2D). Transfection with PLK2 increases the levels of synuclein phosphorylation over 10-fold so that almost all of the activity could be attributed to the transfected kinase. Good agreement was observed between inhibitor potencies in the presence and absence of overexpressed PLK2. In the absence of kinase transfection, the maximum inhibition of p-Ser-129 α-synuclein was around 60%. The remainder may be due to an additional kinase in these cells.

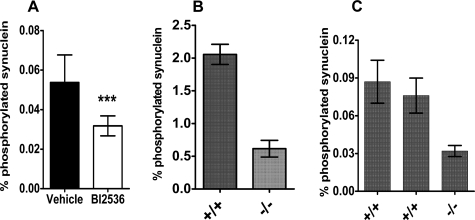

BI2536 was used to validate the role of PLK family members in α-synuclein phosphorylation in vivo. Mice were dosed intravenously with BI2536, the brains were collected, and the levels of total and p-Ser-129 α-synuclein in cortical extracts were measured by ELISA. As shown in Fig. 3A, consistent and significant inhibition of α-synuclein phosphorylation was observed.

FIGURE 3.

Reduction of p-Ser-129 α-synuclein by PLK inhibition in vivo and by PLK2 knock-out. A, mice were treated with either vehicle or 30 mg/kg of BI2536, eight mice per group. Levels of total and p-Ser-129 α-synuclein were measured as under “Experimental Procedures.” B, cortical cultures were prepared from a PLK2 knock-out mouse (–/–) or a wild-type littermate control (+/+). Values shown are the means of triplicate cultures from each donor; error bars show standard deviations. C, fraction of α-synuclein phosphorylated in cerebral cortices from a PLK2 knock-out (–/–) and two wild-type control (+/+) 2–3-month-old mice. Each bar represents results from a single brain; error bars represent standard deviation of assay replicates. Total α-synuclein levels were not altered in either cortical cultures or intact brains (data not shown).

The effect of removal of the plk2 gene on α-synuclein levels was also investigated using PLK2 knock-out mice. Primary cortical cultures from a homozygous knock-out mouse were compared with those from wild-type (plk2+/+) littermates. Measurement of mRNA levels by qRT-PCR showed that PLK2 expression was completely ablated. Comparison of α-synuclein and p-Ser-129 α-synuclein levels in primary cortical cultures from knock-out and wild-type littermates showed that α-synuclein phosphorylation was decreased by about 70%. A similar decrease was observed in soluble α-synuclein in 2–3-month-old cortices (Fig. 3, B and C).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have shown that members of the PLK family, specifically PLK1, -2, and -3, phosphorylate Ser-129 of α-synuclein in vitro, suggesting that they are capable of acting as direct α-synuclein kinases. Studies with inhibitors additionally suggest that PLK2 and PLK3 are responsible for the majority of α-synuclein phosphorylation in cultured neurons and in mouse brain. PLK2-specific shRNA knockdown and genetic deletion of the plk2 gene in mice identify a role for this kinase in particular.

Previous studies of PLK2 have identified several properties that are particularly intriguing for an α-synuclein kinase. It is induced by excitotoxic glutamate agonists (27). Furthermore, Sheng and colleagues have proposed that PLK2 has a critical role in maintaining dendritic spine stability (31) and modulating excitatory glutaminergic synaptic connections (32, 33). Thus, the involvement of PLK2 in α-synuclein phosphorylation provides a potential link between excitotoxic responses and Lewy pathology. Investigation of how the biology of PLK2 relates to the pathogenesis of PD and DLB should help clarify the role of synuclein phosphorylation in these diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Pearl Tang, Anna Liao, and Chris Nishioka for expert technical work; Seymond Pon and Melissa Monahan for managing and tracking the mice used in this study; Wes Zmolek, Eric Goldbach, and Heather Zhang for determining in vivo compound levels; Donald E. Walker for mass spectroscopic expertise; and Eugene M. Johnson, J. William Langston, and particularly Dale Schenk for support and helpful discussions.

Author's Choice—Final version full access.

Note Added in Proof—Brit Mollenhauer and Michael G. Schlossmacher have recently identified PLK2 in a survey of proteins in mouse brain interacting with α-synuclein. Their chapter, “Purification and quantification of neural α-synuclein: Relevance for patho-genesis and biomarker development,” is in Nass, R., and Przedborski, S. (2008) Parkinson's Disease, Molecular and Therapeutic Insights from Model Systems, Elsevier Academic Press Inc., Burlington, MA.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains a supplemental figure, a supplemental table, and supplemental procedures.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PD, Parkinson disease; APMU, N-[4-(4-aminothieno[2,3-d]pyrimidin-5-yl)phenyl]-N′-(3-methylphenyl)urea; DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies; DMAT, 2-dimethylamino-4,5,6,7-tetrabromo-1H-benzimidazole; CK2, casein kinase II; PLK, polo-like kinase; p-Ser-129, phospho-Ser-129; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-PCR; qRT-PCR, quantitative RT-PCR; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; siRNA, small interfering RNA; CEB, cell extraction buffer; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

References

- 1.Spillantini, M. G., Crowther, R. A., Jakes, R., Hasegawa, M., and Goedert, M. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95 6469–6473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spillantini, M. G., Schmidt, M. L., Lee, V. M. Y., Trojanowski, J. Q., Jakes, R., and Goedert, M. (1997) Nature 388 839–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baba, M., Nakajo, S., Tu, P. H., Tomita, T., Nakaya, K., Lee, V. M., Trojanowski, J. Q., and Iwatsubo, T. (1998) Am. J. Pathol. 152 879–884 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kruger, R., Kuhn, W., Muller, T., Woitalla, D., Graeber, M., Kosel, S., Przuntek, H., Epplen, J. T., Schols, L., and Riess, O. (1998) Nat. Genetics 18 106–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polymeropoulos, M. H., Lavedan, C., Leroy, E., Ide, S. E., Dehejia, A., Dutra, A., Pike, B., Root, H., Rubenstein, J., Boyer, R., Stenroos, E. S., Chandrasekharappa, S., Athanassiadou, A., Papapetropoulos, T., Johnson, W. G., Lazzarini, A. M., Duvoisin, R. C., Di Iorio, G., Golbe, L. I., and Nussbaum, R. L. (1997) Science 276 2045–2047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zarranz, J. J., Alegre, J., Gomez-Esteban, J. C., Lezcano, E., Ros, R., Ampuero, I., Vidal, L., Hoenicka, J., Rodriguez, O., Atares, B., Llorens, V., Gomez Tortosa, E., Del Ser, T., Munoz, D. G., and De Yebenes, J. G. (2004) Ann. Neurol. 55 164–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chartier-Harlin, M. C., Kachergus, J., Roumier, C., Mouroux, V., Douay, X., Lincoln, S., Levecque, C., Larvor, L., Andrieux, J., Hulihan, M., Waucquier, N., Defebvre, L., Amouyel, P., Farrer, M., and Destee, A. (2004) Lancet 364 1167–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ibanez, P., Bonnet, A. M., Debarges, B., Lohmann, E., Tison, F., Pollak, P., Agid, Y., Durr, A., and Brice, P. A. (2004) Lancet 364 1169–1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singleton, A. B., Farrer, M., Johnson, J., Singleton, A., Hague, S., Kachergus, J., Hulihan, M., Peuralinna, T., Dutra, A., Nussbaum, R., Lincoln, S., Crawley, A., Hanson, M., Maraganore, D., Adler, C., Cookson, M. R., Muenter, M., Baptista, M., Miller, D., Blancato, J., Hardy, J., and Gwinn-Hardy, K. (2003) Science 302 841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okochi, M., Walter, J., Koyama, A., Nakajo, S., Baba, M., Iwatsubo, T., Meijer, L., Kahle, P. J., and Haass, C. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 390–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson, J. P., Walker, D. E., Goldstein, J. M., De Laat, R., Banducci, K., Caccavello, R. J., Barbour, R., Huang, J., Kling, K., Lee, M., Diep, L., Keim, P. S., Shen, X., Chataway, T., Schlossmacher, M. G., Seubert, P., Schenk, D., Sinha, S., Gai, W. P., and Chilcote, T. J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 29739–29752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waxman, E. A., and Giasson, B. I. (2008) J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 67 402–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirzaei, H., Schieler, J. L., Rochet, J. C., and Regnier, F. (2006) Anal. Chem. 78 2422–2431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellis, C. E., Schwartzberg, P. L., Grider, T. L., Fink, D. W., and Nussbaum, R. L. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 3879–3884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujiwara, H., Hasegawa, M., Dohmae, N., Kawashima, A., Masliah, E., Goldberg, M. S., Shen, J., Takio, K., and Iwatsubo, T. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4 160–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen, L., and Feany, M. B. (2005) Nat. Neurosci. 8 657–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freichel, C., Neumann, M., Ballard, T., Muller, V., Woolley, M., Ozmen, L., Borroni, E., Kretzschmar, H. A., Haass, C., Spooren, W., and Kahle, P. J. (2007) Neurobiol. Aging 28 1421–1435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahle, P. J., Neumann, M., Ozmen, L., Muller, V., Jacobsen, H., Spooren, W., Fuss, B., Mallon, B., Macklin, W. B., Fujiwara, H., Hasegawa, M., Iwatsubo, T., Kretzschmar, H. A., and Haass, C. (2002) EMBO Rep. 3 583–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorbatyuk, O. S., Li, S., Sullivan, L. F., Chen, W., Kondrikova, G., Manfredsson, F. P., Mandel, R. J., and Muzyczka, N. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105 763–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paleologou, K. E., Schmid, A. W., Rospigliosi, C. C., Kim, H. Y., Lamberto, G. R., Fredenburg, R. A., Lansbury, P. T., Jr., Fernandez, C. O., Eliezer, D., Zweckstetter, M., and Lashuel, H. A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 16895–16905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishii, A., Nonaka, T., Taniguchi, S., Saito, T., Arai, T., Mann, D., Iwatsubo, T., Hisanaga, S. i., Goedert, M., and Hasegawa, M. (2007) FEBS Lett. 581 4711–4717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pronin, A. N., Morris, A. J., Surguchov, A., and Benovic, J. L. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 26515–26522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma, S., Charron, J., and Erikson, R. L. (2003) Mol. Cell Biol. 23 6936–6943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marr, R. A., Guan, H., Rockenstein, E., Kindy, M., Gage, F. H., Verma, I., Masliah, E., and Hersh, L. B. (2004) J. Mol. Neurosci. 22 5–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright, S., Malinin, N. L., Powell, K. A., Yednock, T., Rydel, R. E., and Griswold-Prenner, I. (2007) Neurobiol. Aging 28 226–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chilcote, T. J., Banducci, K., Frigon, N. L., Basi, G. S., Anderson, J. P., Goldstein, J., Griswold-Prenner, I., and Chereau, D. (August 9, 2007) World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Patent WO/2007/089862

- 27.Kauselmann, G., Weiler, M., Wulff, P., Jessberger, S., Konietzko, U., Scafidi, J., Staubli, U., Bereiter-Hahn, J., Strebhardt, K., and Kuhl, D. (1999) EMBO J. 18 5528–5539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simmons, D. L., Neel, B. G., Stevens, R., Evett, G., and Erikson, R. L. (1992) Mol. Cell Biol. 12 4164–4169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson, E. F., Stewart, K. D., Woods, K. W., Giranda, V. L., and Luo, Y. (2007) Biochem. 46 9551–9563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steegmaier, M., Hoffmann, M., Baum, A., Lenart, P., Petronczki, M., Krssak, M., Gurtler, U., Garin-Chesa, P., Lieb, S., Quant, J., Grauert, M., Adolf, G. R., Kraut, N., Peters, J. M., and Rettig, W. J. (2007) Curr. Biol. 17 316–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pak, D. T. S., and Sheng, M. (2003) Science 302 1368–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seeburg, D. P., Feliu-Mojer, M., Gaiottino, J., Pak, D. T. S., and Sheng, M. (2008) Neuron 58 571–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seeburg, D. P., and Sheng, M. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28 6583–6591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.