Abstract

In eubacteria, trigger factor (TF) is the first chaperone to interact with newly synthesized polypeptides and assist their folding as they emerge from the ribosome. We report the first characterization of a TF from a psychrophilic organism. TF from Psychrobacter frigidicola (TFPf) was cloned, produced in Escherichia coli, and purified. Strikingly, cross-linking and fluorescence anisotropy analyses revealed it to exist in solution as a monomer, unlike the well-characterized, dimeric E. coli TF (TFEc). Moreover, TFPf did not exhibit the downturn in reactivation of unfolded GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) that is observed with its E. coli counterpart, even at high TF/GAPDH molar ratios and revealed dramatically reduced retardation of membrane translocation by a model recombinant protein compared to the E. coli chaperone. TFPf was also significantly more effective than TFEc at increasing the yield of soluble and functional recombinant protein in a cell-free protein synthesis system, indicating that it is not dependent on downstream systems for its chaperoning activity. We propose that TFPf differs from TFEc in its quaternary structure and chaperone activity, and we discuss the potential significance of these differences in its native environment.

The folding of cytosolic proteins is coordinated by three chaperone systems in eubacteria: trigger factor (TF), DnaK and its cofactors DnaJ and GrpE, and GroEL, together with its cofactor GroES. As TF alone interacts with the ribosomes, it is the first chaperone to bind newly synthesized polypeptides and assist their folding, whereupon it passes them to downstream chaperone systems (12). It has recently been shown that, for multidomain proteins, TF and the DnaK system cooperate to slow down folding and cause a shift to a posttranslational folding mode (24). TF also plays an important role in the regulation of protein translocation due to its position at the ribosome exit tunnel (1, 24).

TF is highly abundant in E. coli (up to 40 μM), with most TF molecules existing in an equilibrium between its monomeric and dimeric states in the cytosol (28). The high cytosolic concentration of TF has recently been linked to a distinct functional role of the chaperone in maintaining newly translated polypeptides in a folding-competent state in the E. coli cytoplasm (35). A distinct antichaperone activity has also been described for TF, however, whereby substoichiometric concentrations of TF lead to increased polypeptide aggregation, whereas high TF/polypeptide ratios can also delay folding as the chaperone maintains polypeptides in a non-native state without promoting their complete refolding (9).

E. coli TF (TFEc) is composed of an N-terminal ribosome-binding tail (domain I), an internal domain with peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase (PPIase) activity (domain II), and a C-terminal domain III that is involved in its chaperone activity (26). The importance of the PPIase domain remains unclear as TF binds non-native nascent polypeptides lacking proline residues (29), while its PPIase activity is also not required for its chaperoning function (15).

Cold-adapted microorganisms, such as psychrophiles and psychrotrophs, are capable of growth at temperatures as low as 0°C. Few molecular chaperones from such bacteria have been investigated in detail, and although TF homologues have been identified in the genomes of pychrophiles such as Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis, Psychrobacter arcticus, or Shewanella frigidimarina, neither their biochemistry nor their importance in cold adaptation has been characterized to the same degree as for GroEL (36). Here, therefore, we present the first detailed investigation of a cold-adapted TF homologue, from Psychrobacter frigidicola (TFPf), and reveal its unexpected behavior: TFPf displays no dimerization, and, importantly, does not exhibit the in vitro chaperonelike holding activity characteristic of TF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

P. frigidicola (DSM 12411) was obtained from DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany and grown in Marine broth. E. coli TOP10 (Invitrogen) and E. coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen) strains were used for cloning and recombinant protein production, respectively, while E. coli W3110 and E. coli W3110 Δtig (6) were used for protein translocation studies. The pIG6scFv2H12 vector was used for expression of the 2H12 scFv antibody fragment (7). pACYC184 and pBADHisB were obtained from NEB Biolabs and Invitrogen, respectively.

Cloning of P. frigidicola tig gene.

DNA manipulations were carried out according to the method of Sambrook and Russell (30a). A 3′ partial sequence of the tig gene was initially amplified from P. frigidicola genomic DNA by PCR using degenerate primers. The 5′ region was then amplified with the primers TFS1 (CTTGGCTACGCGCAGCATTTTTGATTTCG) and TFS2 (GCCGCTTTACCAGCCAATTCTTCAGCTTGG) using an LA Taq PCR in vitro cloning kit (Takara Corp.). The complete arabinose promoter cassette from pBADHisB was amplified and cloned into HindIII-digested pACYC184 to yield the expression vector p15ara. Finally, complete tig genes from P. frigidicola (tigPF) and E. coli (tigEc) were amplified by PCR with or without a C-terminal His6 tag and 5′-NdeI and 3′-PstI flanking restriction sites and cloned using these sites into p15ara to yield p15aratighisPF and p15aratighisEC vectors. The tigPf and tigEc genes were subcloned without His6 tags as BamHI/PstI and BamHI/XhoI fragments, respectively, into pBADHisB.

Expression and purification of TFs from E. coli and P. frigidicola.

TFPf and TFEc were expressed from p15aratighisPF and p15aratighisEC, respectively, in E. coli BL21(DE3). Expression was induced at 25°C in Luria-Bertani medium by the addition of 1 mg of arabinose/ml. The cells were harvested, and proteins were extracted in buffer A (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]) with the addition of 5% CelLytic reagent (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.3 kU of rLysozyme (Invitrogen)/ml, and 50 μg of DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich)/ml. After centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C, the samples were loaded onto a Ni2+-NTA HiTrap cartridge (GE Healthcare), followed by stepwise washing of the resin with buffer A containing NaCl from 100 to 500 mM. The resin was then washed with buffer A containing imidazole from 20 to 250 mM, and fractions containing eluted TF were pooled, dialyzed against 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 1 mM dithiothreitol at 4°C overnight, concentrated, and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Fractions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting (16).

GAPDH refolding assay.

Refolding of denatured GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) was performed based on Huang et al. (10). Denatured enzyme was diluted 50-fold in GAPDH buffer (0.1 M potassium phosphate [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM dithiothreitol) containing 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 3.75, 5, 7.5, 10, or 20 μM TF. The reaction was maintained at 4°C for 30 min, followed by 180 min at 25°C or 15°C. The GAPDH activity was measured by mixing 1-μl reaction aliquots with 99 μl of GAPDH buffer in the presence of 700 μM β-NAD (Sigma-Aldrich) and 700 μM d-l-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich). This was followed by measurement of the synthesized NADH at 340 nm (Tecan microplate spectrophotometer; Genios). The data were fitted to a single exponential equation (Prism program; GraphPad Software), and the relative activity recovered was calculated by dividing the rate constant for refolded GAPDH by the rate constant determined with nondenatured enzyme.

RCM-RNase T1 refolding assay.

RNase T1 from Aspergillus oryzae (Sigma-Aldrich) was denatured, reduced, and carboxymethylated using dithiothreitol as the reducing agent, according to the published protocol (27). Refolding was induced by dilution of reduced and carboxymethylated RNase T1 (RCM-RNase T1) to a final concentration of 0.5 μM in 1.6 M NaCl-0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) in a spectrofluorometer (Cary Eclipse; Varian). TFPf or TFEc was included in the reaction mixture at 0.1 or 0.2 μM. The data were fitted to a single-exponential equation (Prism program).

Glutaraldehyde cross-linking.

TFPf or TFEc (5 μg) was incubated at concentrations of 0.5, 2.5, 10, 20, or 30 μM for assays at 25°C and at 0.15, 0.625, 2.5, 10, or 20 μM for assays at 15°C in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5)-100 mM NaCl-1 mM EDTA for 25 min. Cross-linking was initiated by the addition of 0.1% glutaraldehyde, and the reaction was quenched after 15 min by incubation in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) for 10 min at the relevant assay temperature. Samples were precipitated for 10 min on ice using 10% trichloroacetic acid and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm and 4°C for 30 min. Pellets were solubilized in 8 M urea in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (10% gel) and Coomassie brilliant blue staining.

Fluorescence anisotropy.

Both TFPf and TFEc were labeled by using the Alexa Fluor 532 monoclonal antibody kit (Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturers' protocol. The procedure was optimized to achieve a labeling ratio of approximately one fluorophore per protein. The concentration of protein (M) was calculated by using UV-visible absorption spectroscopy and the following formula: M = (A280 − (A530 × 0.09))/ɛ280, where A280 is the absorbance at 280 nm and A530 is the absorbance at 530 nm, with ɛ280 TFPf = 10,240 cm−1 M−1 and ɛ280 TFEc = 15,930 cm−1 M−1. Labeling ratios (LR) of 1.1 for TFPf and 1.3 for TFEc were calculated by using the following formula: LR = A530/(81,000 × M).

Alexa Fluor 532-labeled TFPf or TFEc (50 nM) was titrated with increasing concentrations of the corresponding unlabeled TF, followed by detection of TF homodimerization by observation of the change in fluorescence anisotropy (r). Fluorescence was measured in a Cary Eclipse spectrofluorometer (Varian) equipped with a variable temperature, Peltier-controlled cell holder (TLC-50F Quantum Northwest) and manual excitation and emission polarizers. The excitation wavelength was 532 nm, and the emission wavelength was 554 nm. The excitation and emission slits were set at 5 and 20 nm, respectively. Anisotropy was measured by using an L-format detection configuration. All titration measurements were performed in 20 mM Tris-HCl-150 mM NaCl-1 mM EDTA buffer (pH 7.5), and samples were incubated at 25°C. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and data were fitted (Origin Software, version 7.5; OriginLab) by using the following equation:

|

where robs is the observed change in anisotropy, TFlab is the fluorescently labeled TF, a = Kd + [TFlab] + [TF], and Kd is the dissociation constant. Since increased concentrations of unlabeled TFs led to an increase in fluorescence intensity, a correction factor (F), where F = intensitymax/intensitymin, was applied. The intensitymax is understood to be the emission intensity from the bound form, while intensitymin, is the intensity of the unbound form (17).

TF-assisted cell-free protein synthesis.

The gene encoding the 2H12 anti-domoic acid scFv antibody fragment was amplified from pIG6scFv2H12 (7), and a T7 promoter was added by overlap PCR. A recombinant M2 FLAG tag was also added at the C terminus of the encoded scFv to detect the synthesized protein. Cell-free translation of the scFv was carried out using 2 pmol/μl of linear template in the PURE System (Post Genome Institute Co., Ltd.), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Where indicated, TFPf or TFEc was added at 2.5, 5, 10, or 20 μM. After incubation for 1 h at 37°C, an equal volume of water was added, and samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm and 4°C for 20 min. Pellets were solubilized in 8 M urea in PBS, and soluble and insoluble fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with an anti-M2 FLAG antibody. The binding of scFv molecules was tested by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to published procedures (7). Briefly, wells of a 96-well microtiter plate were coated with 10 μg of domoic acid (Calbiochem, United Kingdom)/ml conjugated to ovalbumin, followed by blocking with 5% milk powder in PBS. Detection of bound scFv was carried out with an anti-M2 FLAG antibody, followed by the addition of an anti-mouse peroxidase-conjugated antibody and TMB substrate (Sigma-Aldrich).

scFv2H12 export monitoring.

E. coli BL21(DE3) cells containing pIG6scFv2H12 and either p15aratigPF or p15aratigEC plasmids were grown in LB medium containing 1 mg of arabinose/ml at 37°C. Alternatively, E. coli W3110 or E. coli W3110 Δtig cells containing pIG6scFv2H12 and pBADHisB, pBADtigPF, or pBADtigEC constructs were grown at 37°C in LB medium containing 0.05 to 0.125 mg of arabinose/ml. When the optical density at 600 nm reached ∼0.5, scFv expression was induced by the addition of 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside), followed by growth at 25°C for 3 h. The cells were harvested, and protein was extracted with 5% CelLytic reagent, 0.3 kU of rLysozyme/ml, and 50 μg of DNase I/ml in PBS. Insoluble protein fractions were pelleted by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm and 4°C for 20 min and solubilized in 8 M urea in PBS. Soluble and insoluble fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with an anti-His6 tag peroxidase-conjugated antibody.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Isolation of the tig gene from P. frigidicola.

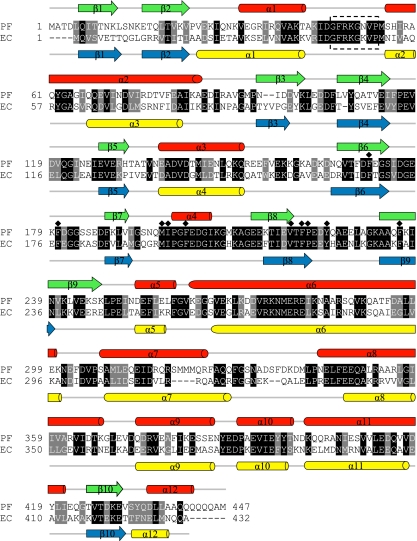

The tig gene from P. frigidicola was cloned and sequenced, and its sequence was confirmed in a further, independent cloning before deposition in GenBank under accession no. EU221522. The 1,341-bp open reading frame encodes a predicted protein of 447 amino acids with an expected mass of 50,629 Da and 58.3% sequence homology with TFEc. Despite this relatively low primary amino acid sequence identity, however, the predicted TFPf protein reveals a secondary structure organization very similar to that of TFEc (Fig. 1). Conserved, putative domains corresponding to the three known domains found in TF's distinctive “crouching dragon” conformation (22) were identified: the TFPf N-terminal domain exhibits a characteristic TF signature sequence (47GFRKGNVP; underlined residues are conserved) essential for ribosome binding (14), while the conserved residues Phe171, Phe180, Met197, Ile198, Phe201, Val218, Phe220, Pro221, Tyr224, and Phe236 (Fig. 1, diamonds) in the PPIase catalytic site, of which Ile198, Tyr224, and Phe236 are strictly conserved in the FK506-binding protein (FKBP) PPIase family, were also identified in the predicted P. frigidicola protein sequence (Fig. 1). In addition to the overall organization of TF domains I, II, and III, the P. frigidicola chaperone exhibits an extended cluster of glutamine residues at its C-terminal end. Similar clusters of amino acids have been noted previously in TF proteins from psychrobacteria, but their role is unclear.

FIG. 1.

Sequence alignment of trigger factors from P. frigidicola and E. coli. The predicted amino acid sequences of E. coli and P. frigidicola TFs were aligned using CLUSTAL W (34). Invariant residues are indicated on a black background, and similar residues are indicated on a gray background. Predicted secondary structures, determined with PORTER (30), are shown above the TFPf and below the TFEc sequences: α-helices are drawn as cylinders, β-strands are drawn as arrows, and other elements are drawn as solid lines. The conserved ribosome-binding motif is boxed in dashed lines, and residues conserved in the PPIase catalytic site are indicated by diamonds.

PPIase activity of TFPf.

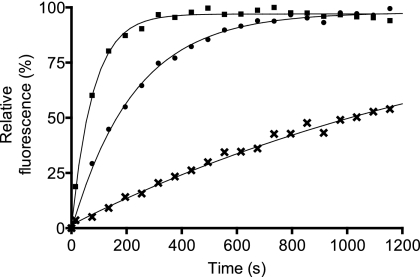

TFPf and TFEc were purified to homogeneity using Ni2+-IMAC (immobilized metal affinity chromatography). Although the PPIase activity of TF is not essential for its in vivo function and appears to be unnecessary also for its chaperone activity (13), the FKBP-like substrate-binding pocket of TF is nevertheless known to play a role in the recognition of and interaction with hydrophobic patches in nascent or unfolded proteins (29). The PPIase activity of TFPf was investigated, therefore, by following refolding of RCM-T1, which is limited by the rate of trans to cis isomerization of its peptidyl-prolyl bonds at Pro39 and Pro55 (31). After denaturation at 15°C (pH 8.0) in the absence of salt, RCM-T1 was found to refold slowly into its active form in 1.6 M salt in the presence of TFPf (Fig. 2). This refolding confirmed the presence of a PPIase activity in the P. frigidicola chaperone, as predicted from analysis of the primary sequence.

FIG. 2.

PPIase activity of P. frigidicola and E. coli TFs. PPIase activity of TFs against the RCM-RNase T1 model substrate. RCM-RNase T1 refolding was monitored by an increase in intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence at 320 nm after excitation at 268 nm. Symbols: •, TFPf; ▪, TFEc; ×, buffer.

TFPf does not present the holding-chaperone activity characteristic of TFEc.

The chaperone activity of TF can be monitored, independently of its peptidyl-prolyl isomerization activity, by measuring its ability to refold GAPDH in vitro (10, 13, 15). In the present study, GAPDH exhibited a low level of spontaneous refolding (ca. 10%) (Fig. 3A), while the yield of reactivated enzyme increased with increasing TFEc concentration, up to a maximum of 40% at 3.75 μM TFEc. At higher chaperone concentrations, however, the reactivation yield decreased dramatically, to as low as 3% in the presence of 20 μM TFEc. This well-known phenomenon, whereby TFEc protects non-native substrates from aggregating but without promoting their complete folding, has been characterized extensively with substrates such as lysozyme (9), carbonic anhydrase II, and creatine kinase (21), as well as GAPDH (10), and is proposed to result from the formation of a stable complex between partially folded substrate and dimeric TF (10, 20).

FIG. 3.

Effect of TF concentration on reactivation of GAPDH at 25°C and 15°C. Refolding of denatured GAPDH was monitored by measuring its enzymatic activity 3 h after 50-fold dilution (final concentration 2.5 μM) in the presence of increasing concentrations of TFPf (•), TFEc (▪), or BSA (×) at 25°C (A) or at 15°C (B).

In the case of TFPf-assisted refolding, the GAPDH reactivation yield again increased with increasing TF concentration, until a plateau at almost 40% of GAPDH activity was reached at 5 μM TFPf. Surprisingly, however, the slowdown in reactivation apparent at higher concentrations of TFEc was not observed with TFPf, which suggests that TFPf cannot stably bind GAPDH folding intermediates in the same manner as TFEc. In this regard, the behavior of TFPf is more similar to that of “true” chaperones such as GroEL (38), DsbC (4), and PDI (2) than to TFEc. In order to further investigate this phenomenon, GAPDH refolding was also analyzed at 15°C, the optimal growth temperature of P. frigidicola. Although the spontaneous refolding of GAPDH was slightly increased at the lower temperature (Fig. 3B) and the holding effect of TFEc was now clearly evident at chaperone concentrations as low as 2.5 μM, TFPf exhibited a pattern of activity very similar to that observed at 25°C (Fig. 3A), but with a slightly increased (ca. 44%) maximal recovery of GAPDH activity.

Since the suppression of GAPDH reactivation by TFEc has been attributed to the ability of TFEc to dimerize and complex with partially folded GAPDH, we compared the dimerization ability of both TFs in order to determine the basis for the difference between the polypeptide-holding properties of the two chaperones.

TFPf does not form dimers in vitro.

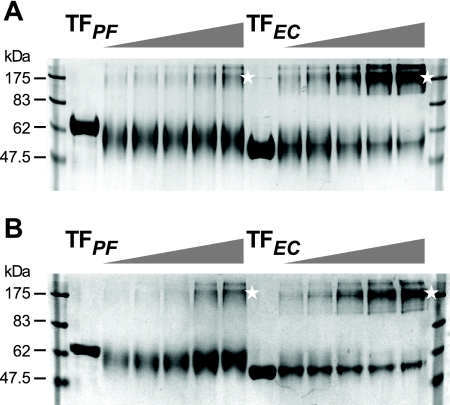

Previously published studies indicate that TFEc exists in a monomer-dimer equilibrium in solution (28). In order to investigate TFPf dimerization, therefore, we initially utilized a glutaraldehyde cross-linking approach to determine the quaternary structure of the purified chaperone at different concentrations.

As expected, TFEc exhibited extensive, concentration-dependent dimerization, leading to the appearance of a dominant product with abnormal migration that corresponds to ∼175 kDa (Fig. 4A, star). Higher-molecular-weight products visible in the gel at higher TFEc concentrations are most likely higher oligomeric or aggregated species. Strikingly, TFPf did not undergo a monomer-to-dimer conversion, even at concentrations as high as 30 μM. While this observation is important in demonstrating that dimerization of TF is not a prerequisite for its chaperone function reported in Fig. 3, it also supports the hypothesis that dimer formation may be important in its polypeptide holding ability. In order to investigate dimerization under conditions more physiologically relevant to TFPf, cross-linking was repeated at 15°C, at which temperature both TFs presented behavior similar to that observed at 25°C (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Analysis of quaternary structures of TFs at 25°C and 15°C by cross-linking. Increasing concentrations (indicated by triangles above the lanes) of TFPf and TFEc were cross-linked using 0.1% glutaraldehyde, precipitated using trichloroacetic acid, and separated by SDS-10% PAGE. (A) Cross-linking at 25°C, with TF concentrations of 0.5, 2.5, 10, 20; and 30 μM; (B) cross-linking at 15°C, with TF concentrations of 0.15, 0.625, 2.5, 10, and 20 μM. Equal amounts of protein were loaded in each lane. The first lane of each TF gradient was not treated with glutaraldehyde. Cross-linked dimers are indicated by stars.

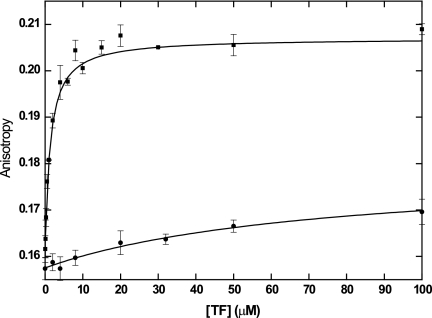

While glutaraldehyde cross-linking has been widely used to characterize TF dimers (26), cross-linking experiments can be limited by the low specificity of the cross-linking agent and the positioning of the target amino acids at the protein surface. In order to confirm these initial observations, therefore, the quaternary structure of TFPf was further analyzed by using steady-state fluorescence anisotropy to characterize changes in protein size (3).

Titration of fluorescently labeled TFs with the corresponding unlabeled TF allowed the resultant changes in anisotropy to be plotted against the concentration of unlabeled TF, with data fitted to a model specific for dimerization, according to the equation for calculating robs provided above. Equilibration of 50 nM labeled TFEc with the unlabeled chaperone at concentrations of up to 100 μM yielded a significant increase in anisotropy (Fig. 5), indicating multimerization of TFEc with a dimer-monomer dissociation constant of 2.8 ± 0.3 μM. This measurement is consistent with the range of Kd values previously determined for TFEc by using high-pressure liquid chromatography (1 μM) (28) and analytical ultracentrifugation (23, 28), which validated the approach prior to characterization of the P. frigidicola chaperone.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of quaternary structure of TFs at 25°C by fluorescence anisotropy. Alexa Fluor 532-TF (50 nM) was titrated against increasing concentrations of unlabeled TF. The change in anisotropy is plotted against the unlabeled protein concentration, as indicated. Symbols: •, TFPf; ▪, TFEc.

As shown in Fig. 5, and in accordance with results from the cross-linking analysis, no significant change in anisotropy was detected for TFPf, even at up to 100 μM unlabeled protein, whereas dimerization was clearly evident with the E. coli chaperone at concentrations as low as 0.5 μM. Similar results were observed with TFPf at 15°C (data not shown). Although both the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of TF molecules have been demonstrated to be involved in dimerization (22, 26, 35, 39), and shortening of the TFEc C terminus by only 13 amino acids almost completely inhibits dimerization while leaving the chaperone activity of the protein unaffected (39), the specific residues that mediate TF dimerization have yet to be identified. It remains difficult to explain the structural basis for the lack of dimerization of TFPf, therefore, but these results indicate nonetheless that, unlike the previously characterized TF from E. coli, TFPf may exist in exclusively monomeric form in the P. frigidicola cytoplasm.

In order to further delineate functional differences between the E. coli and P. frigidicola TFs that may arise from their different quaternary structures, we investigated the ability of TFPf to complement a Δtig mutation in the E. coli GP179 (MC4100 Δtig ΔdnaKJ) host strain (6). Despite successful complementation by TFEc, however, it was not possible to assess complementation by TFPf due to its low-level expression under the same conditions in the E. coli host (data not shown).

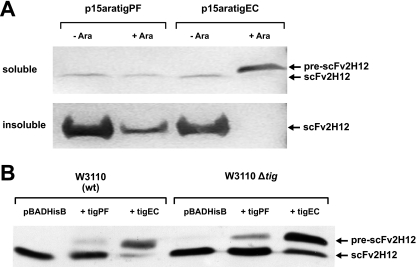

TFPf exhibits reduced retardation of protein export in E. coli.

Previous studies indicate that TFEc, upon binding nascent polypeptides under physiological conditions, can impede their export from the cytoplasm. Since this effect is inversely proportional to the concentration of TF in the cytoplasm (19), it raises the possibility that it might be mediated by the dimeric form of TF (20). Previous work by our own group also demonstrated that periplasmic export of a recombinant scFv antibody fragment, with an OmpA leader peptide, was severely impaired upon coproduction of TFEc (8). In order to further investigate the potential significance of the lack of dimerization of TFPf observed in vitro, therefore, we used the same scFv expression model to examine the effect of TFPf on retarding polypeptide translocation of the cytoplasmic membrane in E. coli.

Upon coproduction of TFEc, the 2H12 scFv occurred almost exclusively in its unprocessed form in E. coli BL21, i.e., with the OmpA leader peptide still attached at its N terminus (Fig. 6A). This indicates that translocation of the recombinant polypeptide across the cytoplasmic membrane is almost completely blocked by elevated intracellular concentrations of TFEc. Coproduction of TFPf at a similar level and under the same conditions had no such effect on scFv secretion, however, since only the processed (and, therefore, translocated) form of the scFv was detectable in cellular preparations (Fig. 6A). In order to investigate whether this lack of retardation could be due to competition for substrate between TFPf and endogenous TFEc in the cell, the export analysis was repeated in parallel in E. coli W3110 and E. coli W3110 Δtig strains. While an unprocessed scFv product could be detected in TFPf-expressing cultures in this analysis, albeit at a dramatically lower concentration than with the E. coli chaperone, no difference in protein export was observed between the parental and Δtig strains (Fig. 6B). Therefore, the lack of retardation observed with TFPf is likely to be due to its inability to form stable complexes with newly translated polypeptides during folding, unlike TFEc which remains stably bound to nascent polypeptide chains for extended periods (19) and so impedes their secretion.

FIG. 6.

Effect of TFs on the periplasmic export of 2H12 scFv in E. coli. (A) 2H12 scFv was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells, with TFPf and TFEc coexpressed from p15aratigPF and p15aratigEC, respectively. Soluble (upper) and insoluble (lower) fractions were analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-His6 tag antibody. (B) pBADHisB + tigPf and + tigEc represent E. coli W3110 or E. coli W3110 Δtig cells expressing 2H12 scFv in the presence of pBADHisB control, pBADtigPF, and pBADtigEC plasmids, respectively. Whole-cell extracts were analyzed as described above. Arrows indicate bands of the expected sizes of the processed and unprocessed scFv polypeptides.

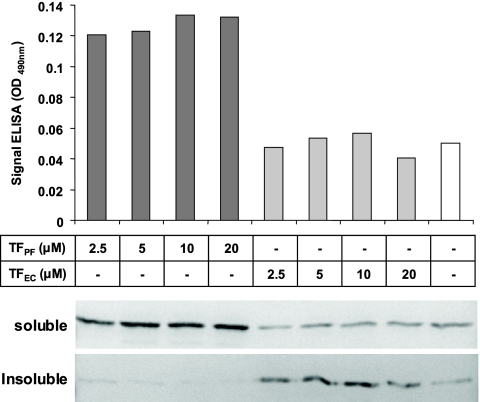

TFPf can assist folding of newly translated proteins independently of other chaperones.

In order to better evaluate the ability of TFPf to fold newly translated polypeptides, we expressed the 2H12 scFv, in the absence of a leader peptide, in a cell-free protein synthesis system. Systems such as the PURE model used in the present study (33), which is based on purified cellular (E. coli) components but lacks endogenous chaperones, allow delineation of the role of individual chaperones in cotranslational protein folding, as recently demonstrated with E. coli TF (11, 18).

We added TFEc or TFPf during translation of the scFv to create a coupled translation-folding scheme in vitro. Analysis of the reactions clearly indicated that TFPf does not simply suppress the aggregation of the scFv, as indicated by Western blot analysis, but also assists its correct folding, as judged by ELISA (Fig. 7). This effect was independent of TFPf concentration in the range 2.5 to 20 μM, whereas the addition of up to 20 μM TFEc led to no improvement in either the solubility or the yield of functional scFv. Conversely, the two TFs led to similar increases in the solubility and functionality of the same 2H12 scFv in E. coli cell expression experiments, however, resulting in up to sixfold increases in the volumetric yield of functional scFv (data not shown). This apparent discrepancy between the effects of E. coli TF on scFv folding in cell-free and cell-based environments can be explained by its requirement to transfer many aggregation-sensitive proteins to downstream chaperone systems such as DnaK/J/GrpE or GroES/EL in the cell to ensure their successful folding (11). Of considerably more interest to the present study, however, is the fact that TFPf could assist the folding of the target protein independently of downstream chaperone machineries, providing another indication of the significantly different folding properties of the P. frigidicola and E. coli chaperones.

FIG. 7.

Effect of increasing concentrations of TFs on cell-free protein synthesis. Various concentrations of TFPf and TFEc were added to a cell-free protein synthesis system prior to production of the 2H12 scFv recombinant antibody fragment. Activity of the soluble scFv was monitored by ELISA. Soluble and insoluble fractions were separated by centrifugation and analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-M2 FLAG antibody. The results are representative of two independent experiments.

Conclusion.

In the present study, we have demonstrated that TF from P. frigidicola does not dimerize or exhibit the characteristic holding-chaperone activity of its E. coli homologue. In addition, it refolds denatured RCM-T1, a process that requires peptidyl-prolyl isomerization, and it can promote the correct folding of a model scFv antibody fragment in the absence of additional chaperones in a cell-free protein synthesis system. The results presented indicate, therefore, that TFPf behaves as a “true” monomeric chaperone in its ability to independently promote the correct folding of polypeptide substrates. Since chaperones from psychrophiles have previously been found to have new adaptive features to facilitate protein folding and stability at low temperatures (5), it will be instructive to determine whether these novel characteristics of TFPf reflect its cold adaptation or distinctive, as-yet-undiscovered, mechanisms in P. frigidicola.

This first characterization of a TF from a psychrophilic species has revealed striking properties of TFPf. In combination with other recent studies in the field (18, 25, 32, 37), it significantly advances our molecular understanding of the functioning of TF. Given in particular that a specific mechanistic role has been proposed for dimeric TFEc in posttranslational protein folding (20), the present results highlight that dimerization may not be a universal feature among bacteria and that the physiological relevance of dimer formation remains to be fully understood.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Genevaux for kindly providing the E. coli GP179 and W3110 Δtig strains and for helpful discussions and A. Schröder for technical assistance.

This study was supported by grant CFTD/04/106 from Enterprise Ireland Science and Technology Agency (S.R.). D.M.T. and A.G.R. acknowledge the support of the National Biophotonics Imaging Platform, a PRTLI-IV funded initiative, and Science Foundation Ireland for the fluorescence instrumentation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 December 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Buskiewicz, I., E. Deuerling, S. Q. Gu, J. Jockel, M. V. Rodnina, B. Bukau, and W. Wintermeyer. 2004. Trigger factor binds to ribosome-signal-recognition particle (SRP) complexes and is excluded by binding of the SRP receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1017902-7906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai, H., C. C. Wang, and C. L. Tsou. 1994. Chaperone-like activity of protein disulfide isomerase in the refolding of a protein with no disulfide bonds. J. Biol. Chem. 26924550-24552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chauvin, F., L. Brand, and S. Roseman. 1994. Sugar transport by the bacterial phosphotransferase system: characterization of the Escherichia coli enzyme I monomer/dimer transition kinetics by fluorescence anisotropy. J. Biol. Chem. 26920270-20274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, J., J. L. Song, S. Zhang, Y. Wang, D. F. Cui, and C. C. Wang. 1999. Chaperone activity of DsbC. J. Biol. Chem. 27419601-19605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrer, M., H. Lunsdorf, T. N. Chernikova, M. Yakimov, K. N. Timmis, and P. N. Golyshin. 2004. Functional consequences of single:double ring transitions in chaperonins: life in the cold. Mol. Microbiol. 53167-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Genevaux, P., F. Keppel, F. Schwager, P. S. Langendijk-Genevaux, F. U. Hartl, and C. Georgopoulos. 2004. In vivo analysis of the overlapping functions of DnaK and trigger factor. EMBO Rep. 5195-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu, X., R. O'Dwyer, and J. G. Wall. 2005. Cloning, expression and characterisation of a single-chain Fv antibody fragment against domoic acid in Escherichia coli. J. Biotechnol. 12038-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu, X., L. O'Hara, S. White, E. Magner, M. Kane, and J. G. Wall. 2007. Optimisation of production of a domoic acid-binding scFv antibody fragment in Escherichia coli using molecular chaperones and functional immobilisation on a mesoporous silicate support. Protein Expr. Purif. 52194-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang, G. C., J. J. Chen, C. P. Liu, and J. M. Zhou. 2002. Chaperone and antichaperone activities of trigger factor. Eur. J. Biochem. 2694516-4523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang, G. C., Z. Y. Li, J. M. Zhou, and G. Fischer. 2000. Assisted folding of d-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase by trigger factor. Protein Sci. 91254-1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaiser, C. M., H. C. Chang, V. R. Agashe, S. K. Lakshmipathy, S. A. Etchells, M. Hayer-Hartl, F. U. Hartl, and J. M. Barral. 2006. Real-time observation of trigger factor function on translating ribosomes. Nature 444455-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kandror, O., M. Sherman, R. Moerschell, and A. L. Goldberg. 1997. Trigger factor associates with GroEL in vivo and promotes its binding to certain polypeptides. J. Biol. Chem. 2721730-1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kramer, G., H. Patzelt, T. Rauch, T. A. Kurz, S. Vorderwulbecke, B. Bukau, and E. Deuerling. 2004. Trigger factor peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase activity is not essential for the folding of cytosolic proteins in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 27914165-14170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kramer, G., T. Rauch, W. Rist, S. Vorderwulbecke, H. Patzelt, A. Schulze-Specking, N. Ban, E. Deuerling, and B. Bukau. 2002. L23 protein functions as a chaperone docking site on the ribosome. Nature 419171-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kramer, G., A. Rutkowska, R. D. Wegrzyn, H. Patzelt, T. A. Kurz, F. Merz, T. Rauch, S. Vorderwulbecke, E. Deuerling, and B. Bukau. 2004. Functional dissection of Escherichia coli trigger factor: unraveling the function of individual domains. J. Bacteriol. 1863777-3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lakowicz, J. R. 2006. Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy, 3rd ed., p. 373. Springer Science, New York, NY.

- 18.Lakshmipathy, S. K., S. Tomic, C. M. Kaiser, H. C. Chang, P. Genevaux, C. Georgopoulos, J. M. Barral, A. E. Johnson, F. U. Hartl, and S. A. Etchells. 2007. Identification of nascent chain interaction sites on trigger factor. J. Biol. Chem. 28212186-12193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee, H. C., and H. D. Bernstein. 2002. Trigger factor retards protein export in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 27743527-43535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu, C. P., S. Perrett, and J. M. Zhou. 2005. Dimeric trigger factor stably binds folding-competent intermediates and cooperates with the DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE chaperone system to allow refolding. J. Biol. Chem. 28013315-13320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu, C. P., and J. M. Zhou. 2004. Trigger factor-assisted folding of bovine carbonic anhydrase II. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 313509-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ludlam, A. V., B. A. Moore, and Z. Xu. 2004. The crystal structure of ribosomal chaperone trigger factor from Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10113436-13441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maier, R., B. Eckert, C. Scholz, H. Lilie, and F. X. Schmid. 2003. Interaction of trigger factor with the ribosome. J. Mol. Biol. 326585-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maier, T., L. Ferbitz, E. Deuerling, and N. Ban. 2005. A cradle for new proteins: trigger factor at the ribosome. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15204-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merz, F., D. Boehringer, C. Schaffitzel, S. Preissler, A. Hoffmann, T. Maier, A. Rutkowska, J. Lozza, N. Ban, B. Bukau, and E. Deuerling. 2008. Molecular mechanism and structure of trigger factor bound to the translating ribosome. EMBO J. 271622-1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merz, F., A. Hoffmann, A. Rutkowska, B. Zachmann-Brand, B. Bukau, and E. Deuerling. 2006. The C-terminal domain of Escherichia coli trigger factor represents the central module of its chaperone activity. J. Biol. Chem. 28131963-31971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mucke, M., and F. X. Schmid. 1992. Enzymatic catalysis of prolyl isomerization in an unfolding protein. Biochemistry 317848-7854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patzelt, H., G. Kramer, T. Rauch, H. J. Schonfeld, B. Bukau, and E. Deuerling. 2002. Three-state equilibrium of Escherichia coli trigger factor. Biol. Chem. 3831611-1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patzelt, H., S. Rudiger, D. Brehmer, G. Kramer, S. Vorderwulbecke, E. Schaffitzel, A. Waitz, T. Hesterkamp, L. Dong, J. Schneider-Mergener, B. Bukau, and E. Deuerling. 2001. Binding specificity of Escherichia coli trigger factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9814244-14249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pollastri, G., and A. McLysaght. 2005. Porter: a new, accurate server for protein secondary structure prediction. Bioinformatics. 211719-1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30a.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 31.Schmid, F. X. 1993. Prolyl isomerase: enzymatic catalysis of slow protein-folding reactions. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 22123-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi, Y., D. J. Fan, S. X. Li, H. J. Zhang, S. Perrett, and J. M. Zhou. 2007. Identification of a potential hydrophobic peptide binding site in the C-terminal arm of trigger factor. Protein Sci. 161165-1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimizu, Y., A. Inoue, Y. Tomari, T. Suzuki, T. Yokogawa, K. Nishikawa, and T. Ueda. 2001. Cell-free translation reconstituted with purified components. Nat. Biotechnol. 19751-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 224673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomic, S., A. E. Johnson, F. U. Hartl, and S. A. Etchells. 2006. Exploring the capacity of trigger factor to function as a shield for ribosome bound polypeptide chains. FEBS Lett. 58072-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tosco, A., L. Birolo, S. Madonna, G. Lolli, G. Sannia, and G. Marino. 2003. GroEL from the psychrophilic bacterium Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis TAC 125: molecular characterization and gene cloning. Extremophiles 717-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ullers, R. S., D. Ang, F. Schwager, C. Georgopoulos, and P. Genevaux. 2007. Trigger Factor can antagonize both SecB and DnaK/DnaJ chaperone functions in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1043101-3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zang, Y., X. Zhang, D. Yuan, Y. Zhang, J. Zhu, H. Lu, C. Chang, and J. Qin. 2006. Expression, purification, and characterization of a novel recombinant fusion protein, rhTPO/SCF, in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr. Purif. 47427-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeng, L. L., L. Yu, Z. Y. Li, S. Perrett, and J. M. Zhou. 2006. Effect of C-terminal truncation on the molecular chaperone function and dimerization of Escherichia coli trigger factor. Biochimie 88613-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]