Abstract

The conjugative transfer of Agrobacterium plasmids is controlled by a quorum-sensing system consisting of TraR and its acyl-homoserine lactone (HSL) ligand. The acyl-HSL is essential for the TraR-mediated activation of the Ti plasmid Tra genes. Strains A6 and C58 of Agrobacterium tumefaciens produce a lactonase, BlcC (AttM), that can degrade the quormone, leading some to conclude that the enzyme quenches the quorum-sensing system. We tested this hypothesis by examining the effects of the mutation, induction, or mutational derepression of blcC on the accumulation of acyl-HSL and on the conjugative competence of strain C58. The induction of blc resulted in an 8- to 10-fold decrease in levels of extracellular acyl-HSL but in only a twofold decrease in intracellular quormone levels, a measure of the amount of active intracellular TraR. The induction or mutational derepression of blc as well as a null mutation in blcC had no significant effect on the induction of or continued transfer of pTiC58 from donors in any stage of growth, including stationary phase. In matings performed in developing tumors, wild-type C58 transferred the Ti plasmid to recipients, yielding transconjugants by 14 to 21 days following infection. blcC-null donors yielded transconjugants 1 week earlier, but by the following week, transconjugants were recovered at numbers indistinguishable from those of the wild type. Donors mutationally derepressed for blcC yielded transconjugants in planta at numbers 10-fold lower than those for the wild type at weeks 2 and 3, but by week 4, the two donors showed no difference in recoverable transconjugants. We conclude that BlcC has no biologically significant effect on Ti plasmid transfer or its regulatory system.

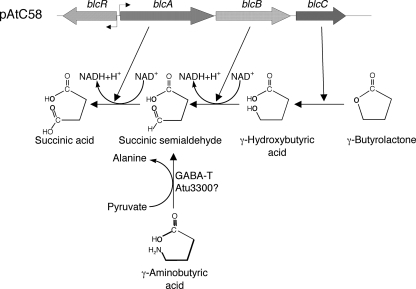

Two isolates of Agrobacterium tumefaciens, strains C58 and A6, produce a lactonase, BlcC (AttM), that degrades acyl-homoserine lactone (HSL) quorum-sensing signals (3, 57). blcC, which encodes the lactonase, is part of the three-gene blcABC operon (Fig. 1) that confers on the bacteria the ability to utilize γ-butyrolactone (GBL) as the sole source of carbon and energy (3, 6). The operon is located on the 543-kbp plasmid pAtC58 in strain C58 (3) and on the linear chromosome of strain A6 (57). The expression of the operon is controlled by BlcR, a repressor coded for by a gene located just upstream of and oriented in reverse to blcABC (Fig. 1) (3, 6, 57). The operon is strongly induced by two intermediates of the catabolic pathway, γ-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) and succinyl semialdehyde (SSA), very weakly by GBL, and not at all by acyl-HSLs (3, 6, 57). In strain A6, the operon also has been reported to be under the control of the stringent response system and induced during entry into stationary phase (52, 57, 58).

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization of the blc operon of pAtC58 and the pathway for degradation of GBL conferred by this operon. Gene organization is from the genome sequence of pAtC58 (GenBank accession number NC_003064). The main pathway and gene-enzyme relationships were described previously by Chai et al. (6). The shunt by which GABA enters the pathway is speculative.

The conjugative transfer of pTiC58 and pTiA6, the Ti plasmids found in strains C58 and A6, is controlled by the quorum-sensing transcription factor TraR, which itself is encoded by the Ti plasmids (18, 38; reviewed in reference 54). The activator induces the expression of three Ti plasmid transfer operons, traAFB, traCDG, and traI-trb (19, 27). Functional TraR requires the acyl-HSL quorum-sensing signal N-(3-oxo-octanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone (60), synthesized by TraI, which is also encoded by the Ti plasmid (21), as a ligand. Signal production is essential; traI mutants do not transfer the Ti plasmid unless the cultures are supplemented with exogenous quormone (45). The quorum-dependent activation of Ti plasmid conjugative transfer systems is itself controlled in a hierarchical manner by a second signaling system. The Ti plasmids confer on their bacterial hosts the ability to induce plant cancers called crown galls. The galls arise following the transfer and integration of a specific small segment of the Ti plasmid, called the T region, from the bacterium into nuclear DNA of target plant cells (42). The resulting tumors produce metabolites, called opines, that the bacteria utilize as sole sources of carbon and energy (9, 15). The opines, which are synthesized by the transformed plant cells using enzymes coded for by genes on the integrated T-DNA, also induce conjugative transfer functions in the bacteria by directly controlling the expression of traR (15). In strain C58, agrocinopines, produced by tumors induced by this strain, control the expression of traR through the opine-modulated repressor AccR on pTiC58 (2, 39). In octopine-type Ti plasmids such as pTiR10 and pTiA6, octopine regulates expression of traR through OccR, an opine-modulated activator encoded on the plasmid (18, 19, 53). The quorum-dependent expression of the Ti plasmid tra regulon thus requires the exposure of the bacteria to the conjugative opine followed by an accumulation of the acyl-HSL signal necessary to generate active TraR. Quite clearly, the development of conjugative competence in A. tumefaciens has evolved to be intimately linked to the niche provided by the crown gall tumor (24, 25, 34, 35, 46).

The expression of BlcC results in greatly diminished levels of accumulation of the acyl-HSL signal in culture supernatants (3, 7, 57), and the lactonase has been reported to interfere with the acyl-HSL-dependent quorum-sensing system that controls Ti plasmid conjugative transfer (57). Such inhibition constitutes one example of a phenomenon called quorum quenching (reviewed in references 1, 10, and 11), and BlcC, based on it ability to degrade acyl-HSLs synthesized by the donor bacteria, has been called a quorum-quenching lactonase (3, 7, 57, 58).

While it is clear that the expression of the lactonase can affect levels of extracellular quormone in culture, the role of this enzyme in quenching the quorum-dependent induction of the Ti plasmid conjugative transfer systems has not been rigorously assessed. Little is known concerning the regulation of the blc operon in planta, and no studies have reported the effect of this enzyme on the development or maintenance of conjugative transfer either in culture or, more importantly, in situ. Moreover, given the dependence of the regulatory circuitry controlling the induction of the conjugative transfer system on the development of the crown gall tumors and their subsequent production of opines, it is not at all clear that the bacteria will express the blc operon and the tra regulon at the same time in the infected plant.

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that BlcC is a quorum-quenching lactonase by assessing the influence of the enzyme on both extracellular and intracellular quormone accumulation and on the development and maintenance of Ti plasmid conjugative transfer both in culture and in situ on developing crown gall tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58 is a classical nopaline/agrocinopine, biovar 1 pathogen. Strain NTL4 (30) is a derivative of strain C58 that lacks pTiC58 but still harbors pAtC58, which codes for the blcABC operon. Strain C58C1RS (37) lacks pTiC58, is resistant to rifampin and streptomycin, and contains a derivative of pAtC58 with an uncharacterized deletion that has removed the blc operon. This strain fails to utilize GBL (data not shown). Strain C58C1, the parent of C58C1RS, harbors an apparently full-sized pAtC58, contains a copy of blc, and grows with GBL as the sole carbon source (data not shown). We constructed a derivative of this strain, C58NTRS, that is resistant to rifampin and streptomycin by selecting sequentially for mutants that are resistant to the two antibiotics. The new strain is otherwise indistinguishable from C58C1 (data not shown). Strain AB153, a reconstructed derivative of C58 that harbors pTiC58 and pAtC58 (33), was used in several experiments. pTiC58ΔaccR contains a deletion in accR that removes opine control and renders the plasmid transfer constitutive (trac) (2). pKPC12 is a derivative of pTiC58 that contains an inactive mutant allele of traR (39). This Ti plasmid fails to transfer and produces only small amounts of acyl-HSL. Ti plasmids were marked with a kanamycin resistance cassette as previously described (45). The nonpolar traI mutant pTiC58ΔtraIKm was constructed as previously described (45). Agrobacterium and Rhizobium spp. listed in Table 1 are from our collection.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of blcC among Agrobacterium and Rhizobium isolates

| Straina | Biovarf | TraR-QS (reference)b | C58 blcC homolog(s)c | Growth ond:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | GBL | ||||

| Agrobacterium spp. | |||||

| C58* | 1 | E, S (39) | SA+, G+ | +++++ | +++++ |

| A6* | 1 | E, S (59) | SA+ | +++++ | +++++ |

| 15955* | 1 | E, S (16) | SA+ | +++++ | +++ |

| R10 | 1 | E, S (18) | SA+ | +++++ | +++++ |

| Ach5 | 1 | E, S (59) | SA+ | +++++ | ++++ |

| IIBv7 | 1 | ND | SA+ | +++++ | ++++ |

| Chry5* | 1 | E, S (34) | SA+ | +++++ | ++ |

| Ant4* | 1 | E (51) | SA+ | +++++ | +++ |

| Bo542* | 1 | E, S (34) | SA− | +++++ | − |

| T37 | 1 | E (14) | SA− | +++++ | + |

| K599* | 1 | S (4) | SA− | +++++ | + |

| B6S3e | 1 | E, S (46) | SA− | +++++ | − |

| B6-Schile | 1 | E, S (46) | SA− | +++++ | − |

| K84* | 2 | E, S (35) | SA−, G− | +++++ | − |

| J73 | 2 | ND | SA− | +++++ | + |

| AB2-73* | 2 | E (50) | SA− | +++++ | − |

| A4* | 2 | E, S (36) | SA− | +++++ | − |

| K299* | 2 | E (35) | SA− | +++++ | + |

| 8196 | 2 | E (36) | SA− | +++++ | − |

| S4 | 3 | S | SA− | +++++ | − |

| TM4 | 3 | ND | SA− | +++++ | − |

| R. leguminosarum 3841 | NA | E, S (55) | G+ | +++++ | ++++ |

| R. etli CFN42 | NA | E, S (48) | G− | +++++ | + |

All listed strains are held in our collection. Strains marked with an asterisk have been reported to produce N-(3-oxooctanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone (4).

TraR-QS, presence of a plasmid coding for a TraR-type quorum-sensing system; E, experimentally determined; S, determined by sequence analysis; ND, no data available.

Determined by moderate-stringency Southern analysis using a blcC probe (SA+ and SA−) and by Blastn, Blastp, and TBlastn analyses of genome sequences available in public databases (G+ and G−).

Growth on solid minimal medium with the indicated substrate as the sole carbon source was assessed visually and graded from +++++ (luxuriant growth) to − (no detectable growth).

Two isolates of strain B6 with different plasmid complements (20).

NA, not applicable.

Media, growth conditions, and reagents.

Agrobacterium and Rhizobium spp. were grown at 28°C. LB or MG/L medium (28) was used as the rich liquid medium, while nutrient agar (Difco), yeast extract mannitol agar, or TY (55) agar was used as the rich solid medium. AB medium (8) supplemented with mannitol (0.2%) (ABM) or with GBL (26 mM; Sigma Chemical Co.) was used as the minimal medium for culturing Agrobacterium spp. Rhizobium spp. were grown on the minimal medium described previously by Ramírez-Romano et al. (41). Antibiotics were included in medium at the following concentrations: rifampin (Rf) at 50 μg per ml, streptomycin (Sm) at 200 μg per ml, kanamycin (Km) at 50 μg per ml, and gentamicin at 25 μg per ml. Growth in liquid cultures was monitored turbidometrically using a Klett colorimeter (red filter) or a Perkin-Elmer spectrophotometer at 600 nm and quantified by viable-colony counts (45). Succinic semialdehyde was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO).

Mutant and reporter constructions.

A 2,098-bp PCR-generated fragment containing the blcC gene from pAtC58 was cloned into the BamHI site of pSF208, a derivative of pBluescript SK(+) in which the EcoRV and SmaI sites had been removed. A 251-bp internal fragment containing the first 224 bp of blcC was removed from this construct by digestion with EcoRV and ScaI and replaced with a gentamicin resistance cassette from pMGM (32). This allele of blcC was marker exchanged into pAtC58 by homologous recombination to produce pAtC58ΔblcC. To construct a blcR mutant, a PCR fragment containing 699 bp of sequence downstream of blcR was fused with a 976-bp PCR fragment containing the first 204 bp of blcR of the blcR-blcA intergenic region and a 5′ 718-bp segment of blcA, and this fragment was cloned into pBluescript II SK(+). The resulting construct is missing the 3′ half of blcR but contains almost 700 bp of pAtC58 DNA directly downstream of the lactonase gene. The gentamicin resistance gene cassette from pMGM was inserted at the BamHI fusion site, and the construct was marker exchanged into pAtC58 to produce pAtC58ΔblcR.

A blcC::lacZ reporter fusion in pAtC58 was constructed by cloning a 272-bp internal fragment of the lactonase gene as an EcoRI-XbaI fragment into pVIK111 (22), generating a translational fusion between the fragment of blcC and lacZYA. The introduction of this nonreplicating plasmid into Agrobacterium strains yielded genomic reporters by Campbell insertions (22).

Expression constructs.

The construction and properties of pSRKGm::traR, in which the expression of traRC58 is tightly regulated and inducible with IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside), were previously described (26). For the construction of pSRKTc::traR, The entire traR expression cassette from pSRKGm::traR was excised as a 2.5-kb BstBI fragment and cloned into BstBI-digested pSRKTc (26). In the absence of IPTG, this construct does not induce the transfer of wild-type pTiC58 (<10−8 transconjugants per input donor). A PCR-generated fragment containing the entire blcC gene from pAtC58 was cloned into pRK415 (23) to yield pRK415::blcC. In this construct, blcC is constitutively expressed from the lac promoter of the vector.

Cloning and purification of BlcC.

The blcC gene was amplified from genomic DNA of C58 by PCR, and the amplicon was cloned into pQE30 (Qiagen), generating a version of the gene with an in-frame His6 sequence at its 5′ end. In this construct, the expression of blcC is under the control of the T5 promoter. The His-tagged BlcC protein was overexpressed in Escherichia coli M15 cells (Qiagen) grown in LB induced with IPTG at 20°C, and the soluble product was purified by Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity chromatography and dialyzed into 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 10% glycerol.

Purification of TraR.

The active dimer TraR expressed from pETR in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells grown with 25 nM 3-oxo-C8-HSL was purified as previously described (40). The purified protein is stable in solution and tightly retains the acyl-HSL ligand (40).

Quantitation of acyl-HSLs.

Acyl-HSLs in culture supernatants, in cell pellets, or from enzyme assay buffer were extracted with ethyl acetate and quantified on thin-layer chromatography plates as previously described by using strain NTL4(pZLR4) as the bioreporter (17, 31, 45).

Matings.

All matings were conducted by the spot plate method using C58C1RS or C58NTRS as a recipient as described previously (37, 45). In this method, volumes of dilutions of donors are spotted onto selective medium onto which a culture of the recipient has been spread as a lawn. Each colony appearing within a spot represents a transconjugant derived from mating with a single donor cell. Since the donors cannot transcribe genes or translate message on the mating plates, this method assesses the conjugative competence of the donor population at the instant that the cells are spotted onto the lawn of recipients. Frequencies are expressed as transconjugant colonies arising per number of donor cells spotted.

In planta matings.

Donors and recipients were grown in MG/L medium to late exponential phase, and population densities were normalized to ca. 108 CFU per ml. Wounds measuring 2.5 cm were produced between the first and second nodes on 6- to 10-week-old tomato plants (Sunny Hybrid; Asgrow) grown in standard potting mix in the greenhouse. The wounds were inoculated with 10-μl suspensions of donors, of recipients, or of a mixture of the two. Inoculated plants were maintained in the greenhouse without pesticides. At 2 weeks after infection and at weekly intervals thereafter, three plants from each treatment were chosen at random, the wounded segment was dissected, and each segment was macerated in 10 ml of sterile 0.9% saline. Volumes of 0.1 and 1.0 ml of the macerates were spread onto selection plates: ABM with Km for donors, ABM with Rf and Sm for recipients, and ABM with Km, Rf, and Sm for transconjugants. Tumors were first visible between weeks 2 and 3 following inoculation.

β-Galactosidase assays.

β-Galactosidase activity, expressed as units per 109 cells, was quantified as described previously (28).

Southern analysis.

Genomic DNA was extracted from bacterial cultures (29) and digested with EcoRV, HindIII, or BglII, and fragments were separated by electrophoresis and transferred onto nylon membranes (29). The membranes were incubated with the blcC gene labeled with digoxigenin under conditions of moderate stringency, and hybridizing fragments were detected by chemiluminescence as described in the digoxigenin application manual (Roche Diagnostics).

RESULTS

BlcC is inducible by pathway intermediates but not by GBL or entry into stationary phase.

There are differences in the literature with respect to conditions under which the blc operon expresses (3, 6, 7, 52, 57, 58). For our studies, it was important to verify under what conditions this gene set is induced. We monitored the expression of the operon in strain C58 grown in minimal mannitol medium under several conditions by monitoring levels of β-galactosidase from a blcC::lacZ fusion recombined into pAtC58. The reporter was induced about 20-fold by SSA but only twofold in cultures supplemented with GBL (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). Moreover, no change in the basal level of expression was detectable in unsupplemented cultures at any phase of growth, including late exponential and early stationary, mid-stationary, and late stationary phases (see Fig. S1B and S1C in the supplemental material). Induction by SSA was rapid, peaking after about 5 h of incubation. As previously reported (7), growth with γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) also induced the operon (see Fig. S1D in the supplemental material). SSA yielded the highest levels of induction at concentrations as low as 500 μM, while growth with GABA even at 10 mM yielded induction levels about twofold lower (see Fig. S1D in the supplemental material). Consistent with previous studies (3, 6, 57), a strain harboring pAtC58ΔblcR blcC::lacZ in which the repressor gene blcR is deleted constitutively expressed the operon at high levels and in all growth phases (see Fig. S1C in the supplemental material).

The finding that GBL does not significantly induce the blcC reporter suggests that the lactone is not a true inducer of the operon. However, blcC is mutated in our reporter, and GBL has been reported to induce the wild-type operon (3). These observations suggest that the lactonase is required to convert GBL to an inducing intermediate, either GHB or SSA. We tested this hypothesis by examining the effect of GBL on the induction of the blcC::lacZ reporter in a strain that also expresses a cloned copy of blcC in trans. When grown with lactone, reporter strains also expressing blcC expressed the reporter fusion at levels 10-fold higher than did strains grown without supplement (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). We conclude that in strain C58, the blc operon is controlled strictly by BlcR in response to inducing substrates including SSA and GABA and that the operon does not autoinduce to any significant level as the cells enter stationary phase.

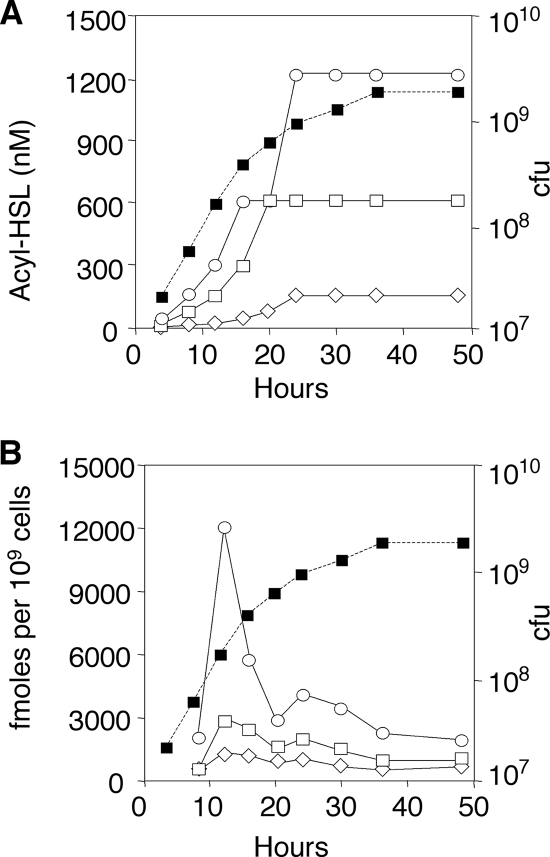

Induction of BlcC strongly affects extracellular but not intracellular levels of acyl-HSL.

We assessed the influence of the lactonase on the levels of accumulation of the acyl-HSL in cultures of strain NTL4 harboring pTiC58ΔaccR, a Ti plasmid that is constitutive for transfer and for the synthesis of the quormone. When cultured in the absence of an inducer, extracellular acyl-HSL accumulated to a maximum level of about 0.6 μM at about 20 h of growth and plateaued as the cells entered stationary phase (Fig. 2A). In cultures in which the expression of blcC was induced with SSA, the signal was detectable but accumulated to levels four- to eightfold lower than that in the uninduced culture (Fig. 2A). A strain deleted for blcC accumulated acyl-HSL to levels about twice that of the blcC+ parent (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Expression of blcC strongly affects extracellular but not intracellular levels of acyl-HSL. Strain NTL4(pTiC58ΔaccRKm) harboring pAtC58 (□ and ⋄) or pAtC58ΔblcC (○) was grown in ABM alone (□ and ○) or ABM with SSA at 500 μM (⋄). Samples were removed at the indicated times and assayed for levels of extracellular (A) and intracellular (B) quormone. A growth curve representative of the three cultures is shown (▪). The experiment was repeated once, with qualitatively similar results.

We also determined the amount of the acyl-HSL retained by the cells as a measure of levels of active intracellular TraR (5, 31). In contrast to the greatly decreased levels of extracellular signal, bacteria grown with SSA retained significant amounts of the acyl-HSL, about half the level detected in cells grown without inducer (Fig. 2B). The ΔblcC mutant accumulated intracellular quormone at levels two- to fourfold higher than that of the blcC+ parent during exponential phase (Fig. 2B). However, the intracellular signal in the blcC mutant dropped to levels approximating those of the blcC+ parent as the cells transitioned into stationary phase.

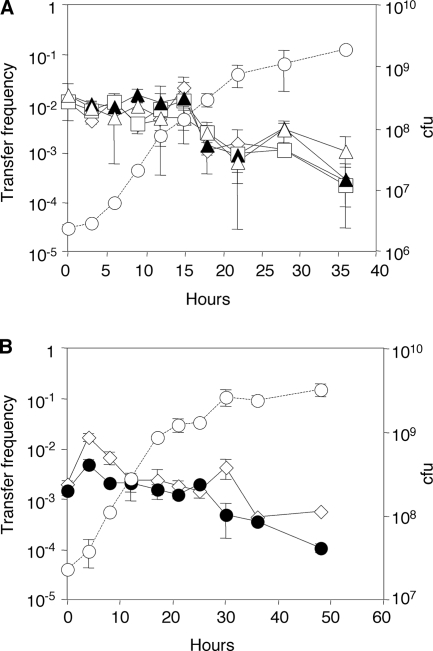

BlcC does not significantly affect conjugative transfer of pTiC58ΔaccR.

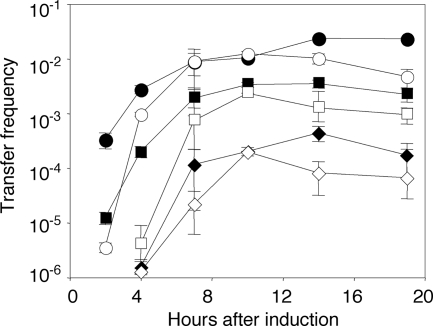

If the lactonase quenches quorum sensing, the induction of the blc operon should affect conjugative transfer frequencies. To test this hypothesis, we examined the influence of BlcC on the transfer properties of our trac Ti plasmid. Donors harboring pTiC58ΔaccRKm were cultured in minimal mannitol medium with or without SSA, samples were taken during growth, and cells were tested for conjugative transfer. Donors incubated with SSA transferred their plasmids at frequencies indistinguishable from those in which the blc operon was not induced at all time points tested (Fig. 3A). We also compared transfer frequencies of donors in which blcC or blcR had been deleted. Donors harboring pAtC58ΔblcC or those harboring pAtC58ΔblcR that constitutively expresses the blc operon transferred the Ti plasmid at frequencies similar to that of donors harboring wild-type pAtC58 (Fig. 3A and B). We conclude from these experiments that either the induced or constitutive expression of the blc operon has no significant effect on conjugative transfer from donors in which the tra system is already induced.

FIG. 3.

BlcC lactonase does not affect conjugative transfer of a transfer-constitutive mutant of pTiC58. (A) Wild type compared with a blcC mutant. (B) Wild type compared with a blcR mutant. Cultures of strain NTL4(pTiC58ΔaccRKm) harboring pAtC58 (□ and ⋄), pAtC58ΔblcC (▴ and ▵) or pAtC58ΔblcR (•) were grown in ABM alone (⋄, ▴, and •) or in ABM supplemented with SSA at 500 μM (□ and ▵). Samples were removed at the indicated times, and frequencies of transfer to C58C1RS, expressed as transconjugants per donor, were measured by drop-plate mating. A growth curve (○) representative of the tested donor cultures is shown. Measurements were performed in triplicate at each time point, and the experiment was repeated once.

BlcC does not degrade the acyl-HSL bound by TraR.

The induction of blcC had only a modest effect on quormone retention by the cells (Fig. 2B) and failed to significantly affect transfer in transfer-constitutive donors (Fig. 3), suggesting that the acyl-HSL bound by TraR is not degraded by the lactonase. We tested this hypothesis by incubating the ligand-bound dimer form of TraR with a purified preparation of BlcC. As a control, we incubated the lactonase with authentic 3-oxo-C8-HSL in solution. While the enzyme rapidly degraded the free signal, the amount of acyl-HSL bound by TraR was not detectably decreased following the addition of lactonase (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

Induction of BlcC has no significant influence on development of conjugative competence.

Although BlcC had no effect on conjugation from donors already committed for transfer, the lactonase might interfere with the induction of the transfer process by preventing the accumulation of the quormone to levels required to activate TraR. The transfer of pTiC58 is induced by the agrocinopine opines, which control the transcription of traR (39). Since this opine is not available, we constructed a donor in which traR is under the control of a very tightly regulated lac promoter (26). In the absence of the lac inducer IPTG, the Ti plasmid does not transfer from such donors, while the addition of IPTG results in transfer at frequencies similar to that of pTiC58ΔaccR (26). In this system, IPTG functions as the surrogate conjugative opine.

To test the influence of the lactonase on the activation of the transfer system, we designed a system in which we could independently induce the expression of blcABC and traR. Donors harboring wild-type pAtC58; Ti plasmid pKPC12, in which traR is mutant; and pSRKGm::traR were cultured in ABM supplemented with IPTG to induce traR and also SSA to induce the blc operon of pAtC58. Samples were removed at intervals, and the donors were tested for conjugative competence by mating with strain C58C1RS. Donors in which the blc operon was induced simultaneously with the tra regulon developed conjugative competence and transferred their Ti plasmids at rates and frequencies indistinguishable from those of donors in which only the transfer system was induced (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Preinduction but not simultaneous induction of BlcC lactonase transiently and modestly affects induction of transfer of pTiC58. (A) Simultaneous induction. A culture of NTL4(pKPC12, pSRKGm::traR) in ABM was split into two subcultures. IPTG was added to both cultures (▪ and ▵), SSA (500 μM) was added to one culture (▵), and the two cultures were reincubated. (B) Preinduction. Two cultures of NTL4(pKPC12, pSRKGm::traR), one in ABM and the other in ABM with SSA (500 μM), were grown for 4 h. IPTG was added to both (time zero), and the subculture containing IPTG only was further divided into two subcultures, one left untreated (□) and the other supplemented with SSA (•). The culture with SSA was similarly divided into two subcultures. The four cultures were incubated for 4 h, at which time SSA was added to one of the two subcultures that had been pretreated with SSA (▴) (arrow), and growth was continued. In both sets of experiments, donors sampled at the indicated times were tested for conjugative competence in drop-plate matings with C58C1RS. A growth curve representative of the tested donor cultures is shown (○). Measurements were performed in triplicate at each time point, and the experiment was repeated once.

We considered the possibility that the preinduction of the blc operon is required to produce enough lactonase to significantly affect the production of the acyl-HSL and the consequent development of the conjugative transfer system. To test this hypothesis, we precultured the donor in medium containing SSA for 4 h to induce the blc operon and then added IPTG to induce traR. Four hours after the induction of traR, we split the culture and added a second dose of SSA to one subculture to ensure the continued expression of the lactonase. In parallel, we cultured the donor under conditions in which only traR was induced. As described above, samples were removed at intervals after the addition of IPTG, and donors were tested for conjugative competence. The preinduction of the blc operon resulted in an initial frequency of transfer about threefold lower than that in donors in which the operon was not induced (Fig. 4B). This difference was reduced to about 1.5-fold by 5 h, and by 10 h, both populations of donors transferred the Ti plasmid with the same efficiencies. The addition of a second dose of SSA to the preinduced donor culture did not further affect transfer frequencies (Fig. 4B). In all three cultures, transfer frequencies remained high even after the donors had transitioned into stationary phase.

As a most stringent test of the hypothesis, we assessed the effect of the constitutive expression of the lactonase on the induction of conjugative competence. Donors harboring our inducible traR system and either wild-type pAtC58 or pAtC58ΔblcR, in which the blc operon is constitutively expressed at high levels (see Fig. S1C in the supplemental material), were cultured in fresh ABM, IPTG was added at several concentrations to induce expression of traR to different levels (26), and incubation of the culture was continued. Samples were removed at intervals, and the donors were tested for conjugative transfer by matings with C58C1RS. Growth with IPTG at 1 mM resulted in a rapid induction of conjugative competence, with transconjugants first appearing in both donors at 2 h (Fig. 5). Donors harboring wild-type pAtC58 transferred the Ti plasmid at frequencies almost 2 orders of magnitude higher than those containing the blcR mutation. Donors harboring pAtC58ΔblcR incubated with lower, suboptimal concentrations of IPTG showed delays in the development of conjugative transfer (Fig. 5). However, in all cases, conjugative transfer from donors constitutively expressing the blc operon rose to levels of the corresponding wild-type donors by the second or third sampling time (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Effects of blcC on induction of transfer depend on levels of expression of traR. Cultures of NTL4(pKPC12, pSRKTc::traR), one with pAtC58 (closed symbols) and the other with pAtC58ΔblcR (open symbols), were grown to early exponential phase in ABM. At time zero, IPTG was added to induce traR at concentrations of 50 μM (⧫ and ⋄), 100 μM (▪ and □), and 1 mM (• and ○). Growth was continued, samples were removed at the indicated times, and donors were tested for conjugative competence. Measurements were performed in triplicate at each time point, and the experiment was repeated once.

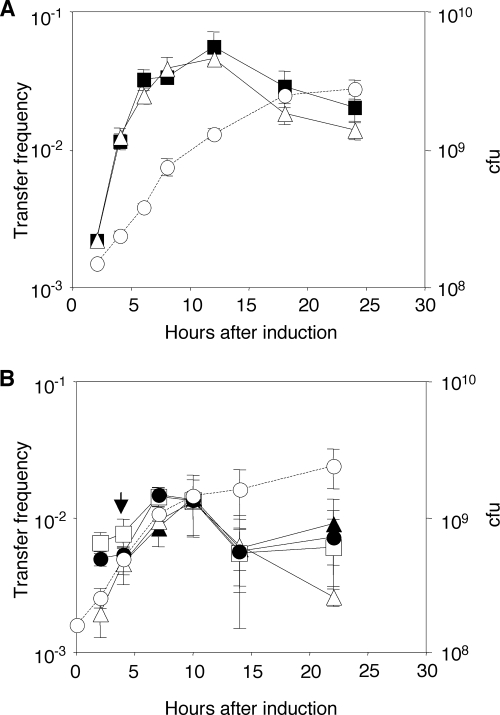

BlcC does not significantly affect transfer of the Ti plasmid in planta.

The regulation of Ti plasmid transfer is tuned via opines to the habitat of the crown gall tumors (9, 15). We assessed the influence of the lactonase on the quorum-sensing system in the natural habitat by measuring Ti plasmid transfer occurring on developing tumors induced by the donors. Tomato plants were inoculated with suspensions of donor cells, either the wild type or mutant for blcC; with recipient cells; and with mixtures of one or the other donor and recipients. At intervals, segments of stems at the inoculation sites were removed, and macerates were plated onto medium selective for donors, for recipients, and for transconjugants. Plants infected with the pathogenic donors developed visible tumors between 2 and 3 weeks after inoculation.

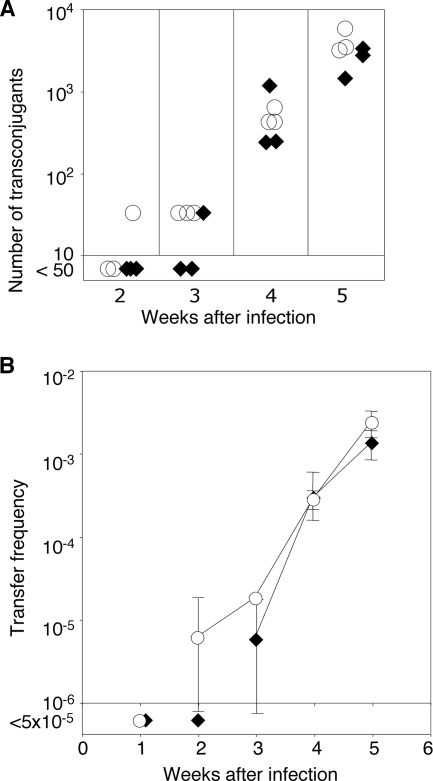

In plants infected with wild-type donors, total numbers of recoverable donors and recipients increased by about 20-fold over the first week, plateauing at levels of about 107 and 106 CFU, respectively (see Fig. S4A and S4B in the supplemental material). Transconjugants were detectable 2 weeks postinoculation in plants infected with the blcC donor and after 3 weeks in plants infected with the wild-type donor (Fig. 6A). At 3 weeks postinfection, two plants infected with the wild-type donor yielded no detectable transconjugants (<50 transconjugants per tumor), while the third plant yielded the same number of transconjugants as the plants infected with the blcC donor. From week 4 on, the numbers of transconjugants that were isolatable from plants infected with either donor were not significantly different (Fig. 6A). Expressing the data as number of transconjugants per donor yielded the same pattern; although initially delayed by 1 week, from week 4 on, the efficiency of transfer from blcC+ donors in planta was indistinguishable from that seen with donors that do not produce the lactonase (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

blcC does not significantly affect in planta transfer of pTiC58. Tomato plants were wounded and inoculated with mixtures of NTL4(pTiC58Km,pAtC58) (⧫) or NTL4(pTiC58Km, pAtC58ΔblcC) (○) as tumorigenic donors and C58C1RS as the recipient. Beginning at week 2, wound sections from three plants were removed at weekly intervals for each mating set and macerated individually, and macerates were plated onto medium selective for donors, recipients, and transconjugants as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Numbers of transconjugants obtained per plant. Each symbol, which represents the average of data for three determinations, represents the datum from one plant at each sampling time point. (B) Frequency of transfer expressed as number of transconjugants recovered per donor.

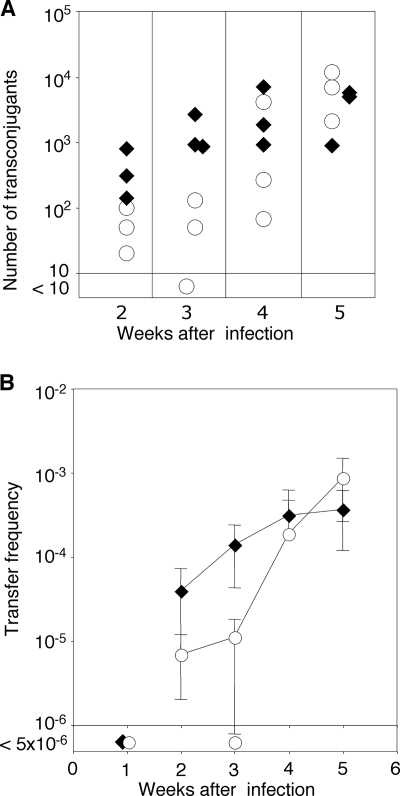

It is conceivable that tomato plants do not produce inducers of the blc operon. To address this possibility, we conducted an in planta mating as described above using the ΔblcR mutant that constitutively expresses the operon as one of the donors. While the number of recoverable wild-type donors remained relatively constant over the course of the experiment, the numbers of ΔblcR donors decreased more than 10-fold at week 2 postinfection (see Fig. S5A in the supplemental material). However, by week 4, ΔblcR donors were recoverable at numbers equal to those of the wild type. The number of recoverable recipients remained relatively constant over the course of the experiment (see Fig. S5B in the supplemental material). Transconjugants were first detectable 2 weeks after infection in crosses with both wild-type and ΔblcR donors, and their numbers increased throughout the 6 weeks of the experiment (Fig. 7A). Compared to the ΔblcR donors, wild-type donors yielded up to 10 times as many transconjugants at weeks 2 and 3 postinfection. However, by weeks 4 and 5, there was little difference in the numbers of transconjugants recovered from tumors representing either mating (Fig. 7A). Transfer efficiencies, expressed as the number of transconjugants per donor, showed similar patterns (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

Constitutive expression of the blc operon exerts a modest early and transient effect on in planta transfer of pTiC58. Tomato plants were infected with mixtures of NTL4(pTiC58Km, pAtC58) (⧫) or NTL4(pTiC58Km, pAtC58ΔblcR) (○) as tumorigenic donors and C58C1RS as the recipient, and the wound sites were sampled and analyzed as described in the legend of Fig. 6. (A) Numbers of transconjugants obtained per plant. Each symbol, which represents the average of data from three determinations, represents the datum from one plant at each sampling time point. (B) Frequency of transfer expressed as number of transconjugants recovered per donor.

Our standard recipient strain, C58C1RS, harbors a copy of pAtC58 that contains an uncharacterized deletion that has removed the blc operon. The use of this strain allowed us to focus on the role of the lactonase produced by the donors. However, in these matings, we could not address the possibility that the BlcC lactonase produced by a blc+ recipient could influence the development of conjugative competence. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a set of in planta matings between wild-type C58 and, as recipients, strain C58C1RS (ΔblcRABC) and the blc+ strain C58NTRS. In the two sets of matings, transconjugants were recoverable at similar numbers at 2 weeks postinfection (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). From week 4 on, matings with the blc wild-type recipient yielded six- to eightfold more transconjugants than did matings with the Δblc mutant (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material).

The quormone is essential for conjugative transfer in planta.

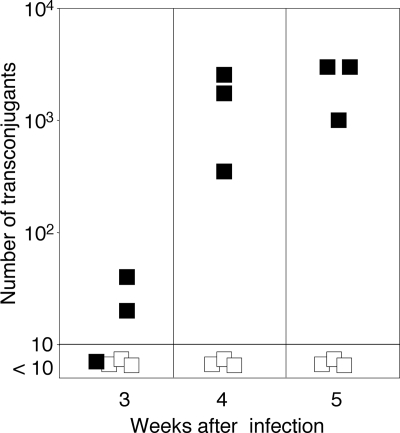

It is possible that tomato plants produce a lactonase-resistant agonistic mimic of acyl-HSL (47). To test this hypothesis, we compared plasmid transfer from wild-type donors with that from donors harboring a Ti plasmid with a nonpolar deletion of traI, which encodes the acyl-HSL synthase (45). In tumors induced by the wild-type donor, transconjugants were detectable at week 3, with their numbers increasing almost 100-fold over the next 2 weeks (Fig. 8). However, no transconjugants were detected in tumors induced by the ΔtraI donor at any time point (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Conjugative transfer in planta requires the acyl-HSL signal. Tomato plants were infected with mixtures of NTL4(pTiC58Km) (▪) or NTL4(pTiC58ΔtraIKm) (□) as donors and C58C1RS as the recipient. The wound sites were sampled and analyzed for the conjugative competence of the Agrobacterium donors as described in the legend of Fig. 6. The data represent the average of the total numbers of transconjugants recovered from three plants of each mating at each time point.

The blc operon is not widely distributed in the genus Agrobacterium.

If it is a dedicated component of the TraR-type quorum-sensing system, the blc operon should be widely distributed among bacteria that harbor plasmids in which transfer is controlled by this regulatory system. We tested this hypothesis by examining a representative group of field isolates of Agrobacterium spp. as well as two members of the genus Rhizobium that harbor plasmids in which conjugation is known to be controlled by TraR-mediated quorum sensing (48, 55). As assessed by Southern analysis, 8 of the 20 agrobacterial isolates tested, with representatives from all three biovars of the genus, contain a detectable homolog of blcC (Table 1). Growth studies showed a strong correlation between the presence of this homolog and utilization of GBL as a sole carbon source. Among the two Rhizobium isolates tested, R. leguminosarum contains the entire blc operon and can utilize GBL, while R. etli lacks this gene system and fails to grow with this substrate (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Quorum quenching as a natural phenomenon should result in quantitatively and temporally significant changes in quorum-regulated phenotypes as a result of conditions that induce the inhibitory mechanism. In the case of Ti plasmid transfer, quorum quenching by BlcC should cause demonstrably significant and lasting changes in transfer frequencies of the Ti plasmid under conditions in which the lactonase is produced by the donor cells. There is little from our results to support the hypothesis that this enzyme exerts such effects on the regulation of Ti plasmid transfer. While the expression of lactonase significantly decreased levels of extracellular quormone (Fig. 2), there was little effect of this enzyme on the endpoint of the process, the conjugative proficiency of Ti plasmid donors. Inducing the expression of blcC did not significantly affect the induction of transfer in donors harboring wild-type Ti plasmids (Fig. 4) or steady-state rates of transfer from donors harboring trac plasmids in culture (Fig. 3). Where normal levels of induced expression of blcC did influence transfer, the effect was modest (≤10-fold), early, and transient (Fig. 4 and 5).

More to the point, the role of its conjugative transfer system is to disseminate the Ti plasmid to appropriate recipients in the environs of the crown gall tumor (24, 25; reviewed in references 9 and 15). blcC either regulated or constitutively expressed in the donor significantly influenced neither the numbers of Ti plasmid-containing transconjugants nor the rate at which they appeared in planta (Fig. 6 and 7). Similarly, the expression of the lactonase by recipients had no inhibitory effect on Ti plasmid transfer from donors coresident on the tumors (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). The greatest effect, again transient, was observed in matings on tumors induced by donors in which blcR had been deleted (Fig. 7). However, under these conditions, blcC is constitutively expressed at levels significantly higher than those observed in wild-type cells grown with optimum amounts of inducers such as SSA and GABA (see Fig. S1D in the supplemental material). It is unlikely that the wild-type operon can be induced to such high levels, either in culture or in planta, casting doubt on the biological relevance of even this relatively low level of inhibition. Moreover, while such blcR donors transferred their Ti plasmids at frequencies up to 10-fold lower than those of blcR+ donors early in the infection, by 5 weeks after inoculation, numbers of transconjugants had reached wild-type levels (Fig. 7). In its wild-type state, BlcC had at best only a modest early effect on the development of conjugative competence in the tumorigenic donors and no demonstrable effect on the long-term emergence of transconjugants in the habitat of the tumor. Finally, the finding that donors that are unable to synthesize an acyl-HSL do not transfer their Ti plasmids at detectable frequencies in planta (Fig. 8) shows that the quormone is essential and that tomato plants do not produce acyl-HSL mimics that might compensate for signal degradation by the lactonase.

Although greatly reducing the amount of extracellular quormone, the expression of the lactonase only modestly affected the levels of intracellular signal (Fig. 2), taken to be a gauge of the amount of active TraR in the cell (5, 31). In culture, 3-oxo-C8-HSL fully activates Ti plasmid transfer at an extracellular concentration as low as 1 nM (45). Assuming free diffusion of the quormone and an average cell volume of 1.5 μm3, this concentration represents between 10 and 20 molecules of signal per cell, corresponding to between 5 and 10 copies of TraR dimer. In culture, signal can accumulate to μM levels (Fig. 2) (57), an amount about 1,000-fold higher than that needed to fully induce the quorum-sensing system. This requirement for only a few molecules of signal per cell may explain why BlcC, even when induced to maximum levels, does not significantly affect the quorum-sensing system.

Zhang et al. (57) previously reported that the expression of the blc operon of strains A6 and C58 is induced during entry into stationary phase. Since they observed a concurrent decrease in the amount of extracellular quormone, they concluded that such induction could serve to shut down conjugation during entry into stationary phase. However, consistent with a previous report by Carlier et al. (3), we did not observe an increase in the expression of blc in stationary-phase cells of C58 in the absence of an inducer (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). In addition, quormone levels stayed high in stationary-phase cultures in which the blc operon was not induced with exogenous substrate. Ligand-bound TraR is stable (40, 63), and the acyl-HSL bound by the dimer is not accessible to degradation by BlcC (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). These observations make it unlikely that the lactonase plays a role in turning over active TraR in any stage of growth. Moreover, if the role of the lactonase is to degrade the signal, the hypothesis predicts that conjugative proficiency would rapidly decay since the signal would become limiting. The transfer of the Ti plasmid from A. tumefaciens B6 apparently decreases substantially in stationary phase (46), an observation consistent with the hypothesis. However, the BlcC lactonase cannot be responsible for this decay; strain B6 lacks the blcC gene and fails to grow with GBL (Table 1). Moreover, a null mutation in or the overexpression of blcC had no significant effect on the conjugative competence of strain C58 in any stage of growth including stationary phase (Fig. 3 and 4). This observation is consistent with recent studies showing that C58 retains conjugative competence well into stationary phase even when extracellular quormone is removed (45). These results strongly suggest that BlcC does not play a role in returning the quorum-sensing system to its off state at any stage of the culture cycle.

More likely, blc has evolved for the catabolism of butyryl compounds. The operon responds to and confers the utilization of GBL as well as its catabolic intermediates GHB and SSA but not acyl-HSLs (3). Interestingly, GBL is itself at best a very poor inducer of the operon (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Induction following growth with this substrate apparently requires its conversion to SSA, which is a strong inducer (6). Although GBL has not been reported to be present in plants, GABA, which does accumulate in plants, induces the blc operon in C58 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) (7), presumably following its conversion to SSA by a GABA-T-like transaminase (Fig. 1). While such an activity has not been reported for Agrobacterium, the genome of strain C58 encodes a protein, Atu3300, that is 66% similar to GABA-T from tomato at the amino acid sequence level. To date, gene sets orthologous in sequence and organization to the blcABC operon and its blcR regulator have been identified in the genomes of only three other bacteria, Yersinia intermedia ATCC 29909, Azorhizobium caulinodans ORS571, and Rhizobium leguminosarum 3841. The operon is not present in another Rhizobium sp., R. etli CNF42, or in other members of the family Rhizobiaceae for which a complete or draft genome sequence is available. Within the agrobacteria, sequences homologous to blcC were detected by Southern analysis in 8 of the 20 isolates that we examined (Table 1). However, of the 12 isolates that lack these sequences, 10 harbor plasmids for which there is either direct or circumstantial evidence for transfer systems controlled by a TraR-dependent quorum-sensing system. While there is a strong association between the presence of the operon and the utilization of GBL, there is no such correlation with a functional TraR-type regulatory system (Table 1). Interestingly, all of the blc+ agrobacteria are members of the biovar 1 subgroup, although not all biovar 1 strains contain the gene. Similarly, while the two Rhizobium isolates examined harbor plasmids with TraR-dependent transfer systems (48, 55), only R. leguminosarum contains the blc operon (Table 1). Moreover, only this isolate catabolizes GBL. Based upon these observations, we propose that the biologically relevant function of the blc operon concerns the catabolism of its butyryl substrates.

Quite clearly, engineered quorum-quenching systems can impact the quorum-sensing systems of targeted bacteria, including pathogens of plants and animals (12, 13, 43, 44, 49, 62). Directed quorum quenching could well be used as an intervention strategy for controlling disease. Moreover, most likely, niches will be found in which quorum-quenching factors produced by one member of a natural consortium influence the signaling systems of other members of the microbial flora (1, 56, 61). It also is conceivable that bacteria that use a quorum-quenching mechanism to modulate their own quorum-sensing system will be found. However, our studies clearly show that the BlcC lactonase produced by Agrobacterium isolates does not quench Ti plasmid quorum sensing to a biologically significant level and is not a dedicated component of the Ti plasmid quorum-sensing regulatory system. Any influence of BlcC on conjugative transfer and its regulation by TraR requires the high-level, continuous expression of the blc operon and is transient, of marginal magnitude, and apparently inadvertent. Given that the blcC system is the only example described to date, the existence of such lactonases or other acyl-HSL-degrading enzymes that have evolved to moderate quorum-sensing systems is an interesting hypothesis still in need of a supporting biological system.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

In a recent paper, Shephard and Lindow (Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:45-53, 2009) reported that Pseudomonas syringae B728a produces two potent acylases, HacA and HacB, that degrade acyl-HSL quorum-sensing signals. However, they showed that expression of these two enzymes does not affect phenotypes known to be controlled by the acyl-CHSL-dependent quorum-sensing system of this bacterium.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant no. R01 GM52465 from the NIH to S.K.F.

We appreciate valuable comments and suggestions from members of the laboratory and from Allen Kerr.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 November 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bauer, W. D., and J. B. Robinson. 2002. Disruption of bacterial quorum sensing by other organisms. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 13234-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck von Bodman, S., G. T. Hayman, and S. K. Farrand. 1992. Opine catabolism and conjugal transfer of the nopaline Ti plasmid pTiC58 are coordinately regulated by a single repressor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89643-647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlier, A., R. Chevrot, Y. Dessaux, and D. Faure. 2004. The assimilation of γ-butyrolactone in Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 interferes with the accumulation of the N-acyl-homoserine lactone signal. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 17951-957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cha, C., P. Gao, Y.-C. Chen, P. D. Shaw, and S. K. Farrand. 1998. Production of acyl-homoserine lactone quorum-sensing signals by gram-negative, plant-associated bacteria. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 111119-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chai, Y., and S. C. Winans. 2004. Site-directed mutagenesis of a LuxR-type quorum-sensing transcription factor: alteration of autoinducer specificity. Mol. Microbiol. 51765-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chai, Y., C. S. Tsai, H. Cho, and S. C. Winans. 2007. Reconstitution of the biochemical activities of the AttJ repressor and the AttK, AttL, and AttM catabolic enzymes of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 1893674-3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chevrot, R., R. Rosen, E. Haudecoeur, A. Cirou, B. J. Shelp, E. Ron, and D. Faure. 2006. GABA controls the level of quorum-sensing signal in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1037460-7464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chilton, M. D., T. C. Currier, S. K. Farrand, A. J. Bendich, M. P. Gordon, and E. W. Nester. 1974. Agrobacterium tumefaciens and bacteriophage PS8 DNA not detected in crown gall tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 713672-3676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dessaux, Y., A. Petit, S. K. Farrand, and P. J. Murphy. 1998. Opines and opine-like molecules involved in plant-Rhizobiaceae interactions, p. 173-197. In H. P. Spaink, A. Kondorosi, and P. J. J. Hooykaas (ed.), The Rhizobiaceae, molecular biology of model plant-associated bacteria. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 10.Dong, Y.-H., and L.-H. Zhang. 2005. Quorum sensing and quorum-quenching enzymes. J. Microbiol. 43101-109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong, Y.-H., L. Y. Wang, and L.-H. Zhang. 2007. Quorum-quenching microbial infections: mechanisms and implications. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 3621201-1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong, Y.-H., S.-F. Zhang, J.-L. Xu, and L.-H. Zhang. 2004. Insecticidal Bacillus thuringiensis silences Erwinia carotovora virulence by a new form of microbial antagonism, signal interference. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70954-960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dong, Y.-H., L. H. Wang, J.-L. Xu, H.-D. Zhang, X.-F. Zhang, and L.-H. Zhang. 2001. Quenching quorum-sensing dependent bacterial infection by an N-acyl homoserine lactonase. Nature 411813-817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellis, J. G., A. Kerr, A. Petit, and J. Tempé. 1982. Conjugal transfer of nopaline and agropine Ti-plasmids—the role of agrocinopines. Mol. Gen. Genet. 186269-274. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farrand, S. K. 1998. Conjugal plasmids and their transfer, p. 199-233. In H. P. Spaink, A. Kondorosi, and P. J. J. Hooykaas (ed.), The Rhizobiaceae, molecular biology of model plant-associated bacteria. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 16.Farrand, S. K., C. I. Kado, and C. R. Ireland. 1981. Suppression of the tumorigenicity by the IncW R plasmid pSa in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Mol. Gen. Genet. 18144-51. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farrand, S. K., Y. Qin, and P. Oger. 2002. Quorum-sensing system of Agrobacterium plasmids: analysis and utility. Methods Enzymol. 358452-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuqua, W. C., and S. C. Winans. 1994. A LuxR-LuxI-type regulatory system activates Agrobacterium Ti plasmid conjugal transfer in the presence of a plant tumor metabolite. J. Bacteriol. 1762796-2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuqua, W. C., and S. C. Winans. 1996. Localization of OccR-activated and TraR-activate promoters that express two ABC-type permeases and the traR gene of Ti plasmid pTiR10. Mol. Microbiol. 201199-1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamada, S. E., and S. K. Farrand. 1980. Diversity among B6 strains of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 1411127-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hwang, I., P.-L. Li, L. Zhang, K. R. Piper, D. M. Cook, M. E. Tate, and S. K. Farrand. 1994. TraI, a LuxI homologue, is responsible for production of conjugation factor, the Ti plasmid N-acylhomoserine lactone autoinducer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 914639-4643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalogeraki, V., and S. C. Winans. 1997. Suicide plasmids containing promoterless reporter genes can simultaneously disrupt and create fusions to target genes of diverse bacteria. Gene 18869-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keen, N. T., S. Tamaki, D. Kobayashi, and D. Trollinger. 1988. Improved broad-host-range plasmids for DNA cloning in gram-negative bacteria. Gene 70191-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerr, A. 1969. Transfer of virulence between isolates of Agrobacterium. Nature 2231175-1176. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerr, A., P. Manigault, and J. Tempé. 1977. Transfer of virulence in vivo and in vitro by Agrobacterium. Nature 265560-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan, S. R., J. Gaines, R. M. Roop II, and S. K. Farrand. 2008. Broad host range expression vectors with tightly regulated promoters and their use for examining the influence of TraR and TraM expression on Ti plasmid quorum sensing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 745053-5062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, P.-L., and S. K. Farrand. 2000. The replicator of the nopaline-type Ti plasmid pTiC58 is a member of the repABC family and is influenced by the TraR-dependent quorum-sensing regulatory system. J. Bacteriol. 182179-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo, Z.-Q., and S. K. Farrand. 1999. Signal-dependent DNA binding and functional domains of the quorum-sensing activator TraR as identified by repressor activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 969009-9014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo, Z.-Q., and S. K. Farrand. 2001. The Agrobacterium tumefaciens rnd homolog is required for TraR-mediated quorum-dependent activation of Ti plasmid tra gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 1833919-3930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo, Z.-Q., T. E. Clemente, and S. K. Farrand. 2001. Construction of a derivative of Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 that does not mutate to tetracycline resistance. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 1498-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo, Z.-Q., S. Su, and S. K. Farrand. 2003. In situ activation of the quorum-sensing transcription factor TraR by cognate and noncognate acyl-homoserine lactone ligands: kinetics and consequences. J. Bacteriol. 1855665-5672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murillo, J., H. Shen, D. Gerhold, A. Sharma, D. A. Cooksey, and N. T. Keen. 1994. Characterization of pPT23B, the plasmid involved in syringolide production by Pseudomonas syringae pv. Tomato PT23. Plasmid 31275-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nair, G. R., Z. Liu, and A. N. Binns. 2003. Reexamining the role of the accessory plasmid pAtC58 in the virulence of Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58. Plant Physiol. 133989-999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oger, P., and S. K. Farrand. 2001. Co-evolution of the agrocinopine opines and the agrocinopine-mediated control of TraR, the quorum-sensing activator of the Ti plasmid conjugation system. Mol. Microbiol. 411173-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oger, P., and S. K. Farrand. 2002. Two opines control conjugative transfer of an Agrobacterium plasmid by regulating expression of separate copies of the quorum-sensing activator gene traR. J. Bacteriol. 1841121-1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petit, A., C. David, G. Dahl, J. G. Ellis, P. Guyon, F. Casse-Delbart, and J. Tempé. 1983. Further extension of the opine concept: plasmids in Agrobacterium rhizogenes cooperate for opine degradation. Mol. Gen. Genet. 190204-214. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piper, K. R., and S. K. Farrand. 2000. Quorum sensing but not autoinduction of Ti plasmid conjugal transfer requires control by the opine regulon and the antiactivator TraM. J. Bacteriol. 1821080-1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piper, K. R., S. Beck von Bodman, and S. K. Farrand. 1993. Conjugation factor of Agrobacterium tumefaciens regulates Ti plasmid transfer by autoinduction. Nature 362448-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piper, K. R., S. Beck von Bodman, I. Hwang, and S. K. Farrand. 1999. Hierarchical gene regulatory systems arising from fortuitous gene associations: controlling quorum sensing by the opine regulon in Agrobacterium. Mol. Microbiol. 321077-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qin, Y., S. Su, and S. K. Farrand. 2007. Molecular basis of transcriptional antiactivation. TraM disrupts the TraR-DNA complex through stepwise interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 28219979-19991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramírez-Romano, M. A., I. Masulis, M. A. Cevallos, V. González, and G. Dávila. 2006. The Rhizobium etli sigma70 (SigA) factor recognizes a lax consensus promoter. Nucleic Acid Res. 341470-1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ream, W. 1989. Agrobacterium tumefaciens and interkingdom genetic exchange. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 27583-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Romero, M., S. P. Diggle, S. Heeb, M. Cámara, and A. Otero. 2008. Quorum quenching activity in Anabaena sp. PCC 7120: identification of AiiC, a novel AHL-acylase. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 28073-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sio, C. F., L. G. Otten, R. H. Cool, S. P. Diggle, P. G. Braun, R. Bos, M. Daykin, M. Cámara, P. Williams, and W. J. Quax. 2006. Quorum quenching by an N-acyl-homoserine lactone acylase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Infect. Immun. 741673-1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Su, S., S. R. Khan, and S. K. Farrand. 2008. Induction and loss of Ti plasmid conjugative competence in response to the acyl-homoserine lactone quorum-sensing signal. J. Bacteriol. 1904398-4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tempé, J., C. Estrade, and A. Petit. 1978. The biological significance of opines. II. The conjugative activities of the Ti plasmid of Agrobacterium tumefaciens, p. 153-160. In M. Ridé (ed.), Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Plant Pathogenic Bacteria. INRA Press, Angers, France.

- 47.Teplitski, M., J. B. Robinson, and W. D. Bauer. 2000. Plants secrete substances that mimic bacterial N-acyl homoserine lactone signal activities and affect population density-dependent behaviors in associated bacteria. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13637-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tun-Garrido, C., P. Bustos, V. González, and S. Brom. 2003. The conjugative transfer of p42a from Rhizobium etli CFN42, which is required for mobilization of the symbiotic plasmid, is regulated by quorum sensing. J. Bacteriol. 1851681-1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ulrich, R. L. 2004. Quorum quenching: enzymatic disruption of N-acylhomoserine lactone-mediated bacterial communication in Burkholderia thailandensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 706173-6180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Unger, L., S. F. Ziegler, G. A. Huffman, V. C. Knauf, R. Peet, L. W. Moore, M. P. Gordon, and E. W. Nester. New class of limited-host-range Agrobacterium mega-tumor-inducing plasmids lacking homology to the transferred DNA of a wide-host-range, tumor-inducing plasmid. J. Bacteriol. 164723-730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Vaudequin-Dransart, V., A. Petit, W. S. Chilton, and Y. Dessaux. The cryptic plasmid of Agrobacterium tumefaciens cointegrates with the Ti plasmid and cooperates for opine degradation. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 7583-591.

- 52.Wang, C., H.-B. Zhang, L.-H. Wang, and L.-H. Zhang. 2006. Succinic semialdehyde couples stress response to quorum-sensing signal decay in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Mol. Microbiol. 6245-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang, C., H.-B. Zhang, G. Chen, L. Chen, and L.-H. Zhang. 2006. Dual control of quorum sensing by two TraM-type antiactivators in Agrobacterium tumefaciens octopine strain A6. J. Bacteriol. 1882435-2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.White, C. E., and S. C. Winans. 2007. Cell-cell communication in the plant pathogen Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 3621135-1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilkinson, A., V. Danino, F. Wisniewski-Dyé, J. K. Lithgow, and J. A. Downie. 2002. N-Acyl-homoserine lactone inhibition of rhizobial growth is mediated by two quorum-sensing genes that regulate plasmid transfer. J. Bacteriol. 1844510-4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wopperer, J., S. T. Cardona, B. Huber, C. A. Jacobi, M. A. Valvano, and L. Eberl. 2006. A quorum-quenching approach to investigate the conservation of quorum-sensing-regulated functions within the Burkholderia cepacia complex. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 721579-1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang, H.-B., K.-H. Wang, and L.-H. Zhang. 2002. Genetic control of quorum-sensing signal turnover in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 994638-4643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang, H.-B., C. Wang, and L.-H. Zhang. 2004. The quormone degradation system of Agrobacterium tumefaciens is regulated by starvation signal and stress alarmone(p) ppGpp. Mol. Microbiol. 521389-1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang, L., and A. Kerr. 1991. A diffusible compound can enhance transfer of the Ti plasmid in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 1731867-1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang, L., P. J. Murphy, A. Kerr, and M. E. Tate. 1993. Agrobacterium conjugation and gene regulation by N-acyl-homoserine lactones. Nature 362446-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang, L.-H. 2003. Quorum-quenching and proactive host defense. Trends Plant Sci. 8238-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhu, H., Y. L. Shen, D. Z. Wei, and J. W. Zhu. 2008. Inhibition of quorum sensing in Serratia marcescens H30 by molecular regulation. Curr. Microbiol. 56645-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhu, J., and S. C. Winans. 1999. Autoinducer binding by the quorum-sensing regulator TraR increases affinity for target promoters in vitro and decreases TraR turnover rates in whole cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 981507-1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.