Abstract

Spores of Bacillus anthracis are enclosed by an exosporium composed of a basal layer and an external hair-like nap. The nap is apparently formed by a single glycoprotein, while the basal layer contains many different structural proteins and several enzymes. One of the enzymes is Alr, an alanine racemase capable of converting the spore germinant l-alanine to the germination inhibitor d-alanine. Unlike other characterized exosporium proteins, Alr is nonuniformly distributed in the exosporium and might have a second spore location. In this study, we demonstrated that expression of the alr gene, which encodes Alr, is restricted to sporulating cells and that the bulk of alr transcription and Alr synthesis occurs during the late stages of sporulation. We also mapped two alr promoters that are differentially active during sporulation and might be involved in the atypical localization of Alr. Finally, we constructed a Δalr mutant of B. anthracis that lacks Alr and examined the properties of the spores produced by this strain. Mature Δalr spores germinate more efficiently in the presence of l-alanine, presumably because of their inability to convert exogenous l-alanine to d-alanine, but they respond normally to other germinants. Surprisingly, the production of mature spores by the Δalr mutant is defective because approximately one-half of the nascent spores germinate and lose their resistance properties before they are released from the mother cell. This phenotype suggests that an important function of Alr is to produce d-alanine during the late stages of sporulation to suppress premature germination of the developing spore.

Bacillus anthracis, the causative agent of anthrax, is a gram-positive, rod-shaped, spore-forming bacterium. Sporulation of B. anthracis, which is similar to sporulation of other Bacillus species, is induced by starvation of vegetative cells for certain essential nutrients (19). Spore formation begins with asymmetric septation that divides the developing cell into a smaller forespore compartment and a larger mother cell compartment, each of which contains a copy of the genome. The mother cell then engulfs the forespore and surrounds it with three protective layers, a cortex composed of peptidoglycan, a closely apposed proteinaceous coat, and a loosely fitting exosporium. After a spore maturation stage, the mother cell lyses to release the mature spore, which is dormant and capable of surviving in the natural soil environment for many years. When spores encounter an aqueous environment containing appropriate nutrients, they can germinate and grow as vegetative cells. Germination is activated by small-molecule germinants, such as l-alanine or a combination of ribonucleosides and amino acids, which interact with germinant-specific receptors in the cell membrane separating the spore core and cortex (22, 34, 40).

The study of B. anthracis spores has expanded greatly in recent years, primarily because of concerns about their use as a biological weapon. The outermost layer of the spore, the exosporium, has been of particular interest because it is both the target of numerous detection devices and the first point of contact with the immune system of an infected host (10, 31). The exosporium serves as a semipermeable barrier that excludes large, potentially harmful molecules, such as antibodies and hydrolytic enzymes (3, 14). The exosporium of B. anthracis and closely related species, such as Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis, is a prominent structure comprising a paracrystalline basal layer and an external hair-like nap (3, 15). Most, if not all, of the filaments of the nap are formed by the collagen-like glycoprotein BclA (5, 39). The basal layer contains numerous structural proteins and at least three enzymes, each of which is capable of degrading a particular spore germinant (36). One of these enzymes is the putative spore-specific alanine racemase Alr, encoded by the alr gene (35). Unlike other characterized exosporium proteins, Alr is nonuniformly incorporated into the spore. Reactivity to anti-Alr monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) indicates that Alr is evenly distributed in most of the exosporium but is not present or is sequestered in a cap-like region of the exosporium covering one end of the spore (37). Additionally, Alr is the only basal layer protein that also has been found in the coat layer of the spore (6). Like other alanine racemases, Alr catalyzes the pyridoxal 5′-phosphate-dependent interconversion of l-alanine and d-alanine (1); l-alanine is a germinant, while d-alanine is a potent germination inhibitor (12). It has been argued that when a spore is in the soil, Alr-catalyzed production of d-alanine suppresses germination under conditions that do not permit viable cell growth (33, 36, 38, 43). Recent studies also have suggested that during infection of a mammalian host, the same Alr activity is necessary to suppress ill-timed germination and thereby enhance the survival of B. anthracis (29).

In this study, we confirmed that Alr synthesis is restricted to sporulating cells and showed that it occurs predominantly in the late stages of sporulation. We mapped two alr promoters that are differentially active during the early and late stages of sporulation and demonstrated that there is biphasic alr transcription during sporulation. We constructed and characterized a mutant strain of B. anthracis in which the alr gene was deleted. Spores produced by this strain were shown to germinate more efficiently in the presence of l-alanine, while they germinated with the same efficiency as wild-type spores in the presence of other germinants. Finally, we discovered an unexpected role for Alr during sporulation; namely, Alr is required to suppress premature germination during the late stages of spore development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and mutant construction.

The Sterne 34F2 veterinary vaccine strain of B. anthracis, obtained from the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, Fort Detrick, MD, was used as the wild-type strain. The Sterne strain is not a human pathogen because it lacks plasmid pXO2, which is necessary to produce the capsule of the vegetative cell. A Δalr mutant of the B. anthracis Sterne strain, designated CLT296, was constructed by allelic exchange essentially as previously described (10). This construction procedure precisely deleted the entire chromosomal alr gene and replaced it with a spectinomycin resistance cassette, which was confirmed by DNA sequence analysis.

Preparation of spores and culture samples.

Spores were prepared by growing B. anthracis strains at 37°C in liquid Difco sporulation medium with shaking until sporulation was complete, typically 48 to 72 h (30). Spores were purified by extensive washing and sedimentation through a two-step gradient consisting of 20% and 50% Renografin, stored at 4°C in water, and quantitated microscopically as previously described (35). The resulting essentially 100% phase-bright spores were termed purified spores. Other spores were prepared as described above except that sedimentation through the Renografin gradient was omitted; these spores were referred to as washed spores. Vegetative and sporulating cells were harvested by centrifugation from cultures grown as described above (10). Culture density was measured spectrophotometrically at 600 nm, and spore development was monitored by phase-contrast microscopy.

Isolation of cellular RNA and primer extension mapping.

Cellular RNA was extracted from sporulating cells with hot phenol, treated with RNase-free DNase, purified, analyzed to determine the concentration and quality, and stored as described previously (10). The 5′ ends of alr transcripts were identified by primer extension mapping as described previously (27), with the following minor modifications. For each primer extension reaction, 50 μg of cellular RNA and excess oligodeoxynucleotide primer were used. The sequence of the primer, which was labeled with 32P at its 5′ end, was 5′-GTGTAACGTTGTTATAAATGGCATC. This primer hybridizes to codons 17 to 25 of the alr transcript. We also included 20 U of the RNase inhibitor SUPERaseIN (Ambion) in each reaction mixture and used SuperScript III (Invitrogen) as the reverse transcriptase. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 55°C for 1 h. The same volume of each reaction mixture was analyzed on a 5% polyacrylamide sequencing gel alongside a dideoxy DNA sequencing ladder of the alr sequence generated with the primer used for primer extension mapping. Primer extension products and sequencing ladders were visualized by autoradiography. In addition to the standard procedure involving identification of transcript-specific primer extension products by alignment with bands in a sequencing ladder, identities were confirmed by spiking sequencing reactions with primer extension products prior to analysis by gel electrophoresis.

RT-PCR.

Levels of alr transcripts in isolated cellular RNA were measured by using the SuperScript III One-Step reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) system with Platinum Taq High Fidelity as directed by the manufacturer (Invitrogen). Each 25-μl reaction mixture contained 100 ng of cellular RNA and excess DNA primers with the sequences 5′-CCGCTCGAGATCGAAGGTCGTATGGAAGAAGCACCATTTTATCG and 5′-CCGCTCGAGCTATATATCGTTCAAATAATTAATTAC. For cDNA synthesis, reaction mixtures were incubated at 55°C for 30 min, and the products were denatured by incubation at 94°C for 2 min. The PCR conditions were 94°C for 14 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 1 min for 25 cycles, followed by a final incubation at 68°C for 5 min. This reaction amplified a 1.2-kb DNA fragment containing the entire alr gene. PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel with Tris-aceate-EDTA buffer and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide.

Immunoblotting.

Samples containing ∼109 vegetative or sporulating cells were collected and resuspended in 30 μl of 62.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 100 mM dithiothreitol, 0.012% bromophenol blue, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol. The samples were placed in a boiling water bath for 8 min to solubilize proteins, which were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) using a 4 to 12% NuPAGE gel (Invitrogen). The proteins in the gel were then electrophoretically transferred from the gel to a nitrocellulose membrane. Following the instructions in the manual for a Bio-Rad Immuno-Blot assay kit, the membrane was blocked with gelatin, probed with a primary MAb at a concentration of 5 μg/ml for 1 h, and washed. The membrane was then probed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (heavy and light chains) secondary antibody for 1 h, washed, and developed with a horseradish peroxidase developer solution. The primary antibody used in this procedure was anti-Alr MAb AR-1, which was prepared as previously described (37).

Germination assay.

Germination of purified spores was monitored essentially as previously described (30). Briefly, ∼109 spores were washed several times in cold (4°C) deionized water, resuspended in 1 ml of water, and then activated by incubation at 65°C for 30 min. Spores were added to 1 ml of germination buffer containing 20 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 7.4) and 200 mM NaCl to obtain a final concentration of 107 spores/ml. Germination was initiated by addition of one or more of the following germinants: l-alanine, inosine, and l-serine (the final concentrations are indicated below). Samples were incubated at 23°C, and their densities were monitored spectrophotometrically at 580 nm. Decreases in the optical density at 580 nm (OD580) were proportional to the number of germinated spores. In addition, samples (>100 cells) were examined by phase-contrast microscopy to confirm the percentage of germinated (phase-dark) spores. Each germination assay was performed at least three times using independent spore preparations, and the results were essentially the same (typically less than 10% deviation from the mean). Average values are presented below.

Resistance properties of spores.

The resistance of purified spores to the organic solvents chloroform, methanol, and phenol and to lysozyme was measured as previously described (30). Sensitivity to heat (80°C for 10 min) was measured using either purified or washed spores, again as previously described (30). The numbers of viable cells before and after heating were determined by plating samples on LB plates, incubating the plates overnight at 37°C, and counting colonies. To confirm the death of phase-dark spores, a sample containing 107 heat-treated spores was added to 1 ml of LB medium, the suspension was incubated for 2 h at 37°C, and the cells were harvested by centrifugation. The spore pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of LB medium, and germination and outgrowth were monitored using phase-contrast microscopy. Killed spores did not germinate and grow into short chains.

Phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy.

Sporulating cells were monitored by phase-contrast microscopy, and images were captured with a Spot charge-coupled device digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Inc.) and displayed by using Spot (v4.0) software. For examination of spores by fluorescence microscopy, slides were prepared essentially as previously described (41). The immobilized spores on the slides were treated with an Alexa 488-labeled MAb, either anti-Alr MAb AR-1 or anti-BclA MAb EF12 (37). Fluorescence microscopy was performed with a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope equipped with a Y-FL epifluorescence attachment.

RESULTS

Two alanine racemases of B. anthracis.

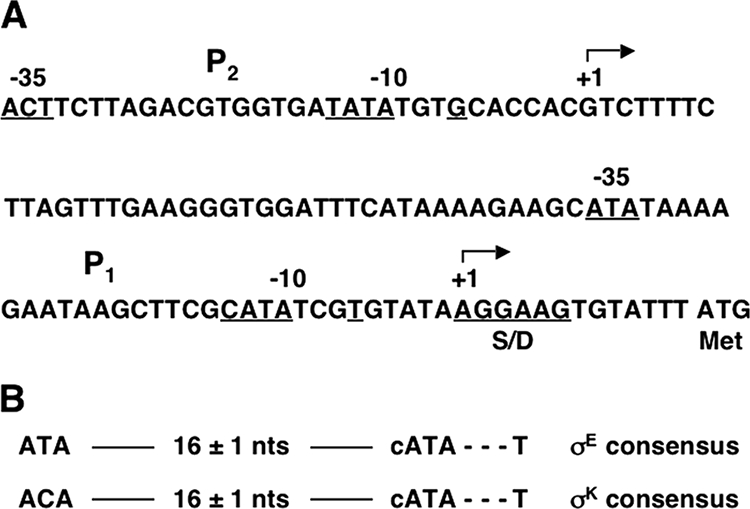

The chromosome of B. anthracis contains two genes that encode alanine racemases, alr (BAS0238) and dal (BAS1932). Each gene appears to be located in a one-gene operon (24). The dal gene is preceded by a putative promoter sequence recognized by the primary sigma factor σA (37), and high levels of dal transcripts are detected only in vegetative cells (4; O. N. Chesnokova and C. L. Turnbough, Jr., unpublished data). Thus, Dal appears to be the enzyme that produces d-alanine for cell wall biosynthesis in vegetative cells (13). On the other hand, the 118-bp intergenic region upstream of the alr gene (Fig. 1A) does not contain a σA-specific promoter sequence (24); instead, it contains multiple promoter-like sequences that might be recognized by either of the mother cell-specific sigma factors, σE and σK (11, 17). σE and σK, which recognize similar promoter sequences (Fig. 1B), are active during the early and late stages of sporulation, respectively (20). Additionally, Alr is readily detectable in spores but undetectable in vegetative cells (6, 37). Evidently, Alr is a spore-specific enzyme involved in the control of spore germination.

FIG. 1.

Sequence of the alr promoter region and consensus sequences recognized by mother cell sigma factors. (A) The −10 and −35 regions of alr promoters designated P1 and P2 are labeled and underlined. Transcription start sites identified by primer extension mapping are labeled +1, and bent arrows indicate the direction of transcription. The alr Shine-Dalgarno sequence (S/D) and translation initiation (Met) codon are indicated. (B) Consensus sequences for promoters recognized by σE and σK. In these sequences, capital letters indicate the most conserved residues. nts, nucleotides.

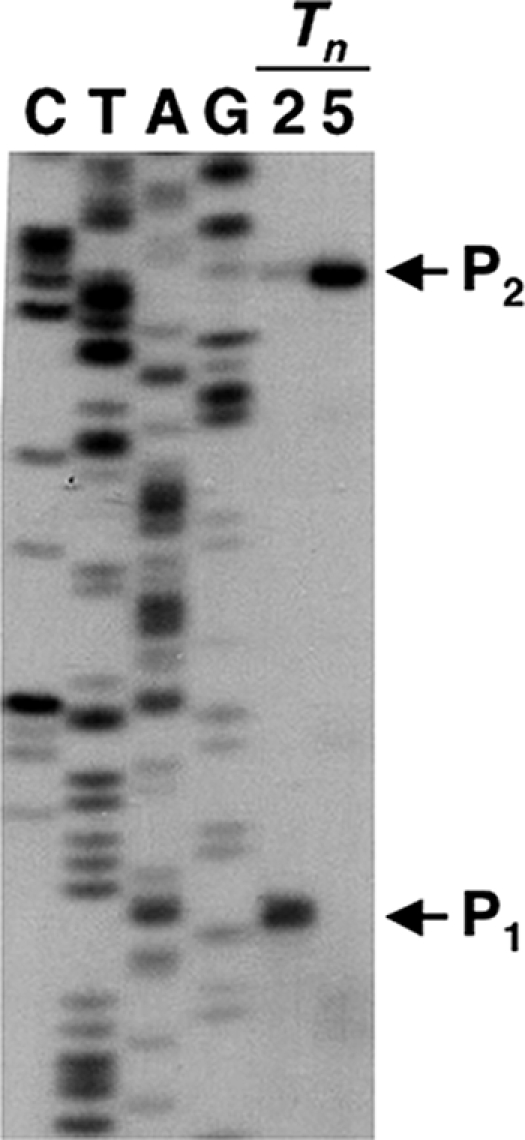

Identification of alr promoters.

To locate alr promoters, we used primer extension mapping to determine the 5′ ends of alr transcripts isolated from cells harvested during the early (T2) and late (T5) stages of sporulation (sampling times are indicated by Tn, where n is the number of hours after the start of sporulation, which is designated T0). Mother cells begin to lyse and release free spores at approximately T9. Analysis of the alr transcripts in cells harvested at T2 revealed two primer extension product bands (Fig. 2). The major band corresponded to alr transcripts initiated at an A residue located six bases downstream from the −10 region of an apparent σE-recognized promoter. The sequence of this promoter, which we designated P1 (Fig. 1A), matches the consensus sequence for σE-specific promoters. The minor band corresponded to alr transcripts initiated at a G residue located seven bases downstream from the −10 region of an apparent promoter sequence that roughly resembles the consensus sequence for σK-specific promoters. This promoter, which was designated P2 (Fig. 1A), is located 73 bases upstream of promoter P1. Apparently, promoter P2 was recognized weakly by σE, resulting in production of a low level of a second alr transcript at T2. In contrast, the analysis of alr transcripts in cells harvested at T5 revealed only one primer extension product band corresponding to transcripts initiated at promoter P2 (Fig. 2). The intensity of this band was severalfold greater than the intensities of the bands in the T2 analysis, indicating that promoter P2 was preferentially recognized by σK and suggesting that there was a substantially higher level of alr transcription at T5. In addition, these results demonstrated that promoter P1 was not recognized by σK. We also analyzed alr transcripts in cells harvested at T6 and T7, and the results were qualitatively the same as the results for transcripts harvested at T5. In control experiments, we demonstrated that the primer extension products described above were not present in similar analyses of cellular RNA isolated from a B. anthracis strain in which the entire alr gene was deleted (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Primer extension mapping of alr transcripts isolated from B. anthracis cells during the early and late stages of sporulation. Lanes C, T, A, and G contained a dideoxy sequencing ladder produced with a DNA template containing the alr locus and a sequencing primer labeled with 32P at the 5′ end; the sequencing primer was the primer used for primer extension mapping. The sequencing ladder was labeled to correspond to the sequence of the nontemplate strand. Lanes Tn contained primer extension products, and the number above each lane indicates the time (in hours after the start of sporulation) at which transcripts were isolated. The positions of primer extension product bands corresponding to alr transcripts initiated at promoters P1 and P2 are indicated by arrows. Bands were visualized by autoradiography.

Transcription initiation at some σE-dependent and σK-dependent promoters is positively or negatively controlled by DNA-binding regulatory proteins, SpoIIID and GerR in the case of σE-dependent promoters and GerE in the case of σK-dependent promoters (11, 17). The consensus sequences for SpoIIID (GGACAAG) and GerE (RWWTRGGYNNYY) binding sites have been established (8, 11), and we searched the alr promoter region for similar sequences. We did not find sequences similar to the SpoIIID consensus sequence, but at least one sequence very similar to the GerE consensus sequence was found at positions −114 to −103 relative to the promoter P2 transcription start site (24). Possibly, GerE binds to this site and facilitates transcription from promoter P2. This activation might compensate for a promoter sequence that only partially matches the consensus σK recognition sequence.

Expression of alr during the cell cycle of B. anthracis.

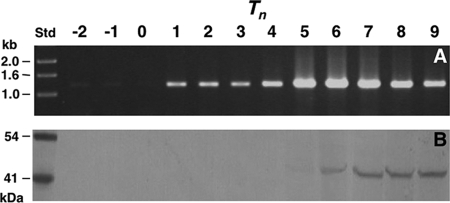

To more closely examine the levels of alr transcription during growth and sporulation, we used RT-PCR to detect alr transcripts in equal amounts of RNA isolated from cell samples harvested hourly from a culture of B. anthracis (Fig. 3A). The results showed that alr transcripts were effectively not present in vegetative cells harvested at T−2 and T−1 or cells harvested at T0. In contrast, alr transcripts were readily detected at similar levels in cells harvested between T1 and T4, which corresponds to the early stages of sporulation when σE is active. However, these levels were severalfold lower than those detected in cells harvested between T5 and T9, which corresponds to the late stages of sporulation when σK is active. This apparently biphasic mode of transcription, which was not detected in a previous transcriptional profile analysis of B. anthracis (4), could result in biphasic synthesis of Alr.

FIG. 3.

Cellular levels of alr transcripts and Alr during growth and sporulation of B. anthracis. Tn indicates the sampling time; the numbers above the lanes indicate the time (in hours) relative to the start of sporulation. Lane Std contained size standards. (A) Levels of alr transcripts measured by RT-PCR, with the PCR products visualized by gel electrophoresis and staining. (B) Levels of Alr measured by immunoblotting of cellular proteins separated by SDS-PAGE.

To measure the amount of Alr synthesized during growth and sporulation, we used immunoblotting to detect Alr in approximately equal numbers of cells that were harvested hourly from the B. anthracis culture described above (Fig. 3B). The anti-Alr MAb AR-1 was used as the probe. AR-1 does not cross-react with Dal, which is 41% identical to Alr (37). The results showed that Alr, which has a molecular mass of 43,662 Da, was not detected between T−2 and T4, even though alr transcripts were produced during part of this time. It is possible that Alr was synthesized from T1 to T4 at levels too low to be detected by our assay. A very light Alr band was detected at T5, and dark Alr bands were detected from T6 to T9. The levels of Alr did not strictly correspond to the levels of alr transcripts during this time period (Fig. 3). Presumably, this observation reflected the onset of detectable Alr production at T5 and the accumulation of Alr in sporulating cells at later time points.

Characterization of a Δalr mutant strain and selected properties of Δalr spores.

To examine the functions of Alr, we constructed a Δalr mutant strain of B. anthracis in which the entire alr gene was deleted. The growth rate of the Δalr strain in rich liquid medium was essentially identical to that of the wild-type strain. The typical level of production of spores (i.e., phase-bright, density gradient-purified spores termed purified spores) by the Δalr strain was approximately one-half that by the wild-type strain, which is discussed in more detail below. We confirmed that purified Δalr spores lacked Alr by SDS-PAGE analysis, immunoblotting, and fluorescence microscopy as previously described (6). Purified Δalr spores appeared to contain an intact exosporium with a normal hair-like nap; when these spores were treated with Alexa 488-labeled anti-BclA MAb EF12 and examined by fluorescence microscopy, the spore-associated fluorescence was essentially identical to that of similarly treated wild-type spores (37). Furthermore, the resistance of purified Δalr spores to heat, lysozyme, and the organic solvents chloroform, methanol, and phenol was essentially the same as that of purified wild-type spores (data not shown).

Germination of purified Δalr spores.

We also compared the germination of heat-activated wild-type and Δalr spores in the presence of various germinants. Spore germination was monitored by determining the decrease in OD580, which accompanied rehydration of the spore core and hydrolysis of the cortex (34). The decrease in OD580 was directly proportional to the number of germinating cells, and a 70% decrease in the OD580 corresponded to germination of essentially all spores. The extent of germination was assessed using samples taken at numerous time points during incubation. At selected time points, the percentages of phase-dark germinating cells were also determined by phase-contrast microscopy; these percentages are the percentages described below.

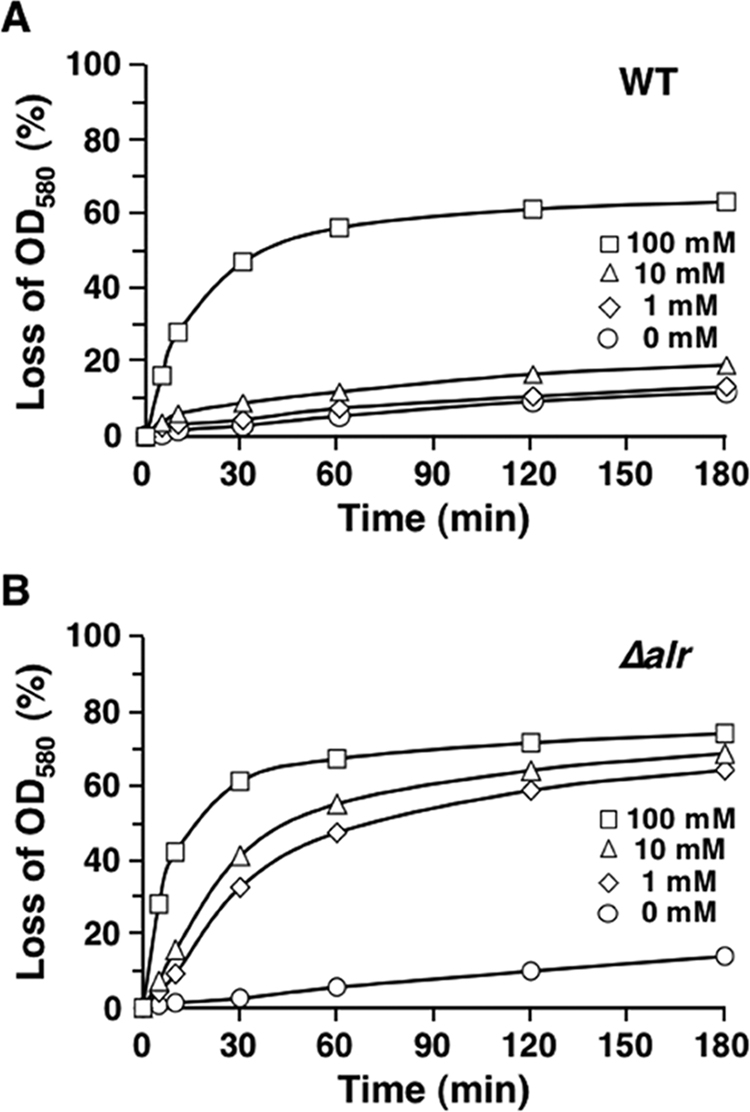

We initially examined germination in spore suspensions incubated for 3 h in the presence of 0, 1, 10, and 100 mM l-alanine (Fig. 4). In the case of wild-type spores, little germination (4% after 3 h) was detected in suspensions containing 0 and 1 mM l-alanine (Fig. 4A). The level of germination was modestly higher (7% after 3 h) in the presence of 10 mM l-alanine. In contrast, germination was nearly complete (90% after 3 h) in the presence of 100 mM l-alanine. Interestingly, in this sample the number of germinating cells reached a plateau after 1 h of incubation and did not increase significantly later (Fig. 4A). Similar plateaus at lower percentages of germination were observed when wild-type spores were incubated in the presence of 25, 50, and 75 mM l-alanine (data not shown). These patterns suggested that germination was inhibited prior to the germination of all spores, perhaps because of the production of d-alanine. The results obtained with the Δalr spores were strikingly different. Although clearly concentration dependent, germination of these spores was extensive even at low concentrations of l-alanine. After 1 h of incubation, the percentages of phase-dark cells were 64, 79, and 99% with 1, 10, and 100 mM l-alanine, respectively (Fig. 4B). Additional incubation resulted in essentially complete germination with all three concentrations of l-alanine. The apparent inhibition of germination observed with wild-type spores was not observed with Δalr spores.

FIG. 4.

l-Alanine-activated germination of spores produced by the wild-type and Δalr strains of B. anthracis. Wild-type (A) and Δalr (B) spores were incubated in the presence of the different concentrations of l-alanine indicated, and germination was monitored by determining the decrease in the OD580 at selected time points. A 70% decrease in the OD580 corresponded to germination of essentially all spores in the sample. WT, wild type.

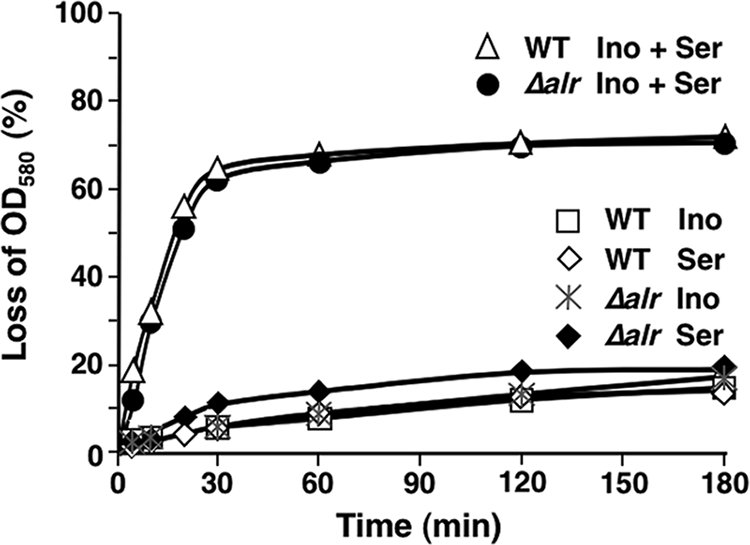

We also examined germination in the presence of a different stimulus, 1 mM inosine and the amino acid cogerminant l-serine at a concentration of 1 mM (22). Neither 1 mM inosine nor 1 mM l-serine alone effectively stimulated germination of wild-type or Δalr spores (Fig. 5). However, in the presence of the two compounds, germination occurred rapidly and efficiently for both spore types. The rates of germination of wild-type and Δalr spores were essentially the same, and nearly all spores germinated within 30 min (Fig. 5). Another amino acid that can serve as a cogerminant for inosine is l-alanine. In a separate experiment, we showed that the germination profiles of wild-type and Δalr spores in the presence of 1 mM inosine and 1 mM l-alanine (data not shown) were essentially identical to the profiles observed with 1 mM inosine and 1 mM l-serine (Fig. 5). Taken together, our results indicate that Alr suppresses germination of wild-type spores in the presence of l-alanine alone and has no effect on germination activated by other germinants. Similar conclusions were drawn from a characterization of ΔalrA spores of B. thuringiensis (42).

FIG. 5.

Germination of wild-type and Δalr spores in the presence of inosine and the amino acid cogerminant l-serine. As indicated, spores were incubated in the presence of 1 mM inosine (Ino) and/or 1 mM l-serine (Ser), and germination was monitored by determining the decrease in the OD580. WT, wild type.

Germination of nascent spores within mother cells of the Δalr mutant.

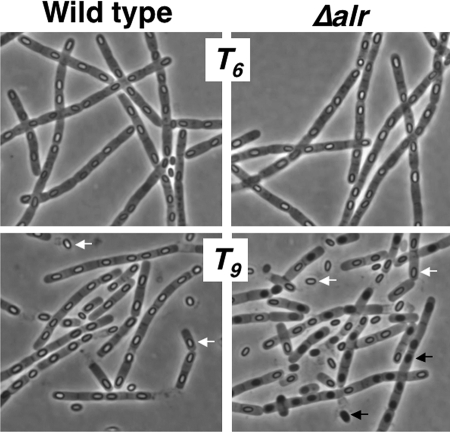

Although liquid cultures of the wild-type and Δalr strains grew similarly, we observed a curious difference between the densities of the two cultures during sporulation. Between T6 and T9, the turbidity of the Δalr culture decreased by one-third, while the turbidity of the wild-type culture remained essentially constant. To analyze this difference, we monitored sporulating cells of both strains by phase-contrast microscopy. From T0 to T6, the appearance of sporulating cells of the wild-type strain and the appearance of sporulating cells of the Δalr strain were essentially identical; by T6, most mother cells in both cultures contained phase-bright forespores (Fig. 6). In the wild-type culture, there was little additional change in the appearance of sporulating cells at T7 and T8; however, at T9, mother cells began to lyse and release mature phase-bright spores (Fig. 6). In contrast, an unusual change was observed in the Δalr culture starting at T7; namely, phase-bright forespores began to turn phase dark, indicating that they were germinating within the mother cell (Table 1). The number of phase-dark forespores (technically germinating cells) increased until T9, when mother cell lysis began (Fig. 6). At this time, approximately 50% of all forespores had turned phase dark. Once the spores were released from the mother cell, the appearance of phase-bright and phase-dark spores did not change (Table 1). Evidently, the conversion of forespores from phase bright to phase dark accounted for the decrease in optical density of the Δalr culture from T6 to T9.

FIG. 6.

Examination of sporulating wild-type and Δalr cells by phase-contrast microscopy. Micrographs were taken at T6 and T9. The white and black arrows indicate phase-bright and phase-dark spores, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Percentages of forespores that turned phase dark during sporulation of wild-type and Δalr strains of B. anthracis

| Time | % of forespores that turned phase dark

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Δalr | |

| T6 | 0 | 0 |

| T7 | 0 | 6 |

| T8 | 0 | 16 |

| T9 | <1 | 48 |

| T21 | <1 | 50 |

The conversion of phase-bright spores to phase-dark germinating cells is typically accompanied by the loss of resistance properties, such as heat resistance (30). To determine if this conversion caused Δalr spores to become sensitive to heat, we purified spores from a 48-h Δalr culture by extensive washing. This procedure removed essentially all vegetative material and left a 1:1 mixture of phase-bright and phase-dark spores called washed spores. These spores were examined to determine their resistance to heat by incubating them at 80°C for 10 min. Plating spores before and after heat treatment showed that 49% ± 1% of the spores were killed (Table 2). Microscopic examination of the spores following incubation in a rich medium revealed that only the phase-dark spores were killed. As a control, we prepared washed wild-type spores, essentially all of which were phase bright, and examined their heat resistance. Within experimental error, all washed wild-type spores were heat resistant (Table 2). These observations indicate that the phase-dark spores produced by the Δalr strain had in fact lost their resistance to heat and presumably other resistance properties as well. In this analysis, we did not use spores purified by sedimentation through a density gradient. After sedimentation, only phase-bright spores are in the pellet; phase-dark spores remain at the top of the gradient along with vegetative debris. This separation accounts for the yield of purified Δalr spores that was 50% lower than the typical yield of wild-type spores as mentioned above.

TABLE 2.

Heat sensitivities of washed Δalr and wild-type spores

| Spores | % Phase bright | No. of coloniesa

|

% Survival | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not heated | Heated | |||

| Δalr | 50 | 437 | 210 | 48 |

| Δalr | 50 | 156 | 77 | 50 |

| Wild type | 99 | 311 | 305 | 98 |

| Wild type | 99 | 65 | 65 | 100 |

Two concentrations of spores of each strain were examined.

DISCUSSION

A remarkable feature of the B. anthracis exosporium is that it contains at least three enzymes that presumably remain active for many years in the harsh soil environment. In addition to Alr, these enzymes include an annotated inosine-uridine-preferring nucleoside hydrolase encoded by BAS2693, which we recently showed is actually a purine-specific nucleoside hydrolase (O. N. Chesnokova and C. L. Turnbough, Jr., unpublished data). This enzyme is capable of degrading the germinants inosine and adenosine to nongerminant products. The B. thuringiensis homolog of this enzyme also was recently shown to be a purine-specific nucleoside hydrolase, which is capable of suppressing inosine- or adenosine-induced spore germination (26). The third exosporium enzyme is a superoxide dismutase encoded by BAS1378, which catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide free radicals to hydrogen peroxide and oxygen (35). This enzyme could protect the spore from toxic levels of superoxide generated by macrophages and other host cells during infection (2, 28), or it could participate in oxidative cross-linking of exosporium proteins (18). Additionally, it has been reported that germination of B. anthracis spores is stimulated by exposure to low levels of superoxide ions (2). Presumably, the flux of superoxide could be effectively eliminated by the exosporium superoxide dismutase, which would suppress spore germination. Thus, all three of the characterized exosporium enzymes are capable of degrading germinants and apparently suppressing spore germination. Although germination is an essential step in the B. anthracis cell cycle, these observations suggest that the spore is designed so that germination is inhibited under certain conditions.

Conditions under which suppression of germination might be advantageous include exposure of spores to aqueous soil environments that contain nutrients at levels that are not high enough to support viable cell growth and an eventual increase in the spore number (32). In this instance, exosporium enzyme activities could degrade germinants presumably present at low concentrations and, in the case of Alr, could also synthesize the germination inhibitor d-alanine (43). Suppression of spore germination might also be beneficial during infection, which requires ingestion of spores by resident macrophages (or other phagocytes) and transit of spore-containing macrophages to regional lymph nodes (7, 9, 16). During this process, spores germinate and become vegetative bacteria, a step necessary for eventual bacterial amplification and disease. Once a spore germinates, however, the outgrowing cell is susceptible to killing by the engulfing macrophage (21, 25). It has been proposed that this killing is modulated by the anatomical location of the macrophage within the host and that lymph nodes provide a relatively favorable niche for bacterial survival (16). Therefore, suppression of germination until spores reach a lymph node should enhance bacterial survival. Such a delay in germination might be achieved through higher, or more effective, exosporium enzyme activities early in infection; a mechanism for regulating these activities or their effects on germination during infection has not been established. Recent studies have demonstrated, however, that endogenous d-alanine can inhibit germination of B. anthracis spores during infection (29).

In this study, we described a previously unrecognized event during which suppression of germination is beneficial for B. anthracis. Our results indicate that during spore formation, Alr converts endogenous l-alanine to d-alanine and thereby inhibits germination of the forespore within the mother cell. In the absence of Alr, approximately one-half of the forespores germinate. The resulting germinating cells, which are eventually released from the mother cell, do not possess the resistance properties of mature spores. In this case, d-alanine appears to be an effective germination inhibitor even in the presence of the complex mixture of metabolites within the mother cell. Previous studies have demonstrated the ability of d-alanine to inhibit germination in complex growth media (21, 29). It is also possible that the other exosporium enzymes, particularly purine nucleoside hydrolase, contribute to the suppression of premature germination within the mother cell. Additional experiments are required to confirm such a role. Furthermore, many other Bacillus species produce spores containing a spore-associated alanine racemase (23). In the case of spores that naturally lack a recognizable exosporium, this enzyme is found in the spore coat (19). It is likely, therefore, that these other Bacillus species also employ a spore-specific alanine racemase to suppress germination of the developing forespore, thereby maximizing the production of resistant spores. At present, it is not clear whether attachment of the alanine racemase to the forespore is required for this process. It is possible that soluble alanine racemase within the mother cell is capable of synthesizing enough d-alanine to inhibit forespore germination.

Another possible function of Alr during sporulation is the production of d-alanine for cortex biosynthesis. The glycan strands of the cortex are cross-linked via peptide side chains containing d-alanine (13). Although the level of cross-linking in the cortex is much lower than that in the cell wall, cross-linking is required for spore core dehydration, spore heat resistance, and rapid spore germination (13). In this study, we observed that phase-bright Δalr spores appear to be normal when they are examined microscopically, that they are as resistant to heat as wild-type spores, and that they germinate normally in the presence of inosine and an amino acid cogerminant, suggesting that Δalr spores contain a normally cross-linked cortex. If this is the case, the most likely source of d-alanine for the biosynthesis of the Δalr spore cortex is Dal. In B. anthracis, it appears that Dal is made predominantly in vegetative cells, but it could persist in sporulating cells. Alternatively, a low level of Dal could be synthesized during sporulation. It is interesting that Yan et al. recently reported the expression pattern of the dal homolog alrB in B. thuringiensis (42). Similar levels of transcripts of alrB were detected during vegetative growth and sporulation, which is markedly different from the pattern of dal transcription observed in B. anthracis (4). The reason for the apparently different dal/alrB expression patterns in B. anthracis and B. thuringiensis is unclear, and additional experiments are required to confirm this fundamental difference between these closely related species.

An additional surprise in this study was the discovery of a biphasic mode of transcription of the alr operon during sporulation, which has not been reported for other operons encoding proteins involved in exosporium formation. Transcription of the alr operon appears to occur at a low level during the early stages of sporulation when σE is active and at a high level during the late stages of sporulation when σK is active. This biphasic pattern involves two alr promoters designated P1 and P2. Early in sporulation, most alr transcription is initiated at promoter P1, which has a sequence that matches the consensus σE recognition sequence. A small fraction of alr transcription during this time is initiated at the more upstream promoter, P2, which has a sequence that roughly matches the consensus σK recognition sequence. Apparently, promoter P2 is recognized weakly by σE. Late in sporulation, all detectable alr transcription is initiated at promoter P2, indicating that this promoter is primarily a σK-dependent promoter and that promoter P1 is a σE-specific promoter. Evidently, the biphasic mode of alr transcription is due to a sigma factor-dependent switch in promoter selection during sporulation. It is possible that this switch is aided by activation of promoter P2 by the regulatory protein GerE, which might compensate for relatively weak intrinsic binding of σK to this promoter.

It is tempting to speculate that biphasic alr transcription is involved in the nonuniform distribution of Alr within the spore. However, we were unable to detect Alr in cells during the early stages of sporulation, which appears to be inconsistent, although not completely incongruous, with this hypothesis. This failure might have been due to very low levels or tight sequestration of Alr. Further studies are required to determine whether biphasic transcription of the alr operon plays a role in the localization of Alr in the spore.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant AI057699.

We thank Evvie Allison for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 12 December 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Au, K., J. Ren, T. S. Walter, K. Harlos, J. E. Nettleship, R. J. Owens, D. I. Stuart, and R. M. Esnouf. 2008. Structures of an alanine racemase from Bacillus anthracis (BA0252) in the presence and absence of (R)-1-aminoethylphosphonic acid (l-Ala-P). Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F 64327-333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baillie, L., S. Hibbs, P. Tsai, G.-L. Cao, and G. M. Rosen. 2005. Role of superoxide in the germination of Bacillus anthracis endospores. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 24533-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ball, D. A., R. Taylor, S. J. Todd, C. Redmond, E. Couture-Tosi, P. Sylvestre, A. Moir, and P. A. Bullough. 2008. Structure of the exosporium and sublayers of spores of the Bacillus cereus family revealed by electron crystallography. Mol. Microbiol. 68947-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergman, N. H., E. C. Anderson, E. E. Swenson, M. M. Niemeyer, A. D. Miyoshi, and P. C. Hanna. 2006. Transcriptional profiling of the Bacillus anthracis life cycle in vitro and an implied model for regulation of spore formation. J. Bacteriol. 1886092-6100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boydston, J. A., P. Chen, C. T. Steichen, and C. L. Turnbough, Jr. 2005. Orientation within the exosporium and structural stability of the collagen-like glycoprotein BclA of Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol. 1875310-5317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boydston, J. A., L. Yue, J. F. Kearney, and C. L. Turnbough, Jr. 2006. The ExsY protein is required for complete formation of the exosporium of Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol. 1887440-7448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cleret, A., A. Quesnel-Hellmann, A. Vallon-Eberhard, B. Verrier, S. Jung, D. Vidal, J. Mathieu, and J. N. Tournier. 2007. Lung dendritic cells rapidly mediate anthrax spore entry through the pulmonary route. J. Immunol. 1787994-8001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crater, D. L., and C. P. Moran, Jr. 2001. Identification of a DNA binding region in GerE from Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1834183-4189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dixon, T. C., M. Meselson, J. Guillemin, and P. C. Hanna. 1999. Anthrax. N. Engl. J. Med. 341815-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong, S., S. A. McPherson, L. Tan, O. N. Chesnokova, C. L. Turnbough, Jr., and D. G. Pritchard. 2008. Anthrose biosynthetic operon of Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol. 1902350-2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eichenberger, P., M. Fujita, S. T. Jensen, E. M. Conlon, D. Z. Rudner, S. T. Wang, C. Ferguson, K. Haga, T. Sato, J. S. Liu, and R. Losick. 2004. The program of gene transcription for a single differentiating cell type during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. PLoS Biol. 2e328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fey, G., G. W. Gould, and A. D. Hitchens. 1964. Identification of d-alanine as the auto-inhibitor of germination of Bacillus globigii spores. J. Gen. Microbiol. 35229-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foster, S. J., and D. L. Popham. 2002. Structure and synthesis of cell wall, spore cortex, teichoic acids, S-layers, and capsules, p. 21-41. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives. From genes to cells. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 14.Gerhardt, P. 1967. Cytology of Bacillus anthracis. Fed. Proc. 261504-1517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerhardt, P., and E. Ribi. 1964. Ultrastructure of the exosporium enveloping spores of Bacillus cereus. J. Bacteriol. 881774-1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guidi-Rontani, C. 2002. The alveolar macrophage: the Trojan horse of Bacillus anthracis. Trends Microbiol. 10405-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helmann, J. D., and C. P. Moran, Jr. 2002. RNA polymerase and sigma factors, p. 289-312. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives. From genes to cells. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 18.Henriques, A. O., and C. P. Moran, Jr. 2000. Structure and assembly of the bacterial endospore coat. Methods 2095-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henriques, A. O., and C. P. Moran, Jr. 2007. Structure, assembly, and function of the spore surface layers. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61555-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hilbert, D. W., and P. J. Piggot. 2004. Compartmentalization of gene expression during Bacillus subtilis spore formation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68234-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu, H., Q. Sa, T. M. Koehler, A. I. Aronson, and D. Zhou. 2006. Inactivation of Bacillus anthracis spores in murine primary macrophages. Cell. Microbiol. 81634-1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ireland, J. A. W., and P. C. Hanna. 2002. Amino acid- and purine ribonucleoside-induced germination of Bacillus anthracis ΔSterne endospores: gerS mediates responses to aromatic ring structures. J. Bacteriol. 1841296-1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanda-Nambu, K., Y. Yasuda, and K. Tochikubo. 2000. Isozymic nature of spore coat-associated alanine racemase of Bacillus subtilis. Amino Acids 18375-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanehisa, M., S. Goto, M. Hattori, K. F. Aoki-Kinoshita, M. Itoh, S. Kawashima, T. Katayama, M. Araki, and M. Hirakawa. 2006. From genomics to chemical genomics: new developments in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 34D354-D357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang, T. J., M. J. Fenton, M. A. Weiner, S. Hibbs, S. Basu, L. Baillie, and A. S. Cross. 2005. Murine macrophages kill the vegetative form of Bacillus anthracis. Infect. Immun. 737495-7501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang, L., X. He, G. Liu, and H. Tan. 2008. The role of a purine-specific nucleoside hydrolase in spore germination of Bacillus thuringiensis. Microbiology 1541333-1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu, J., and C. L. Turnbough, Jr. 1994. Effects of transcriptional start site sequence and position on nucleotide-sensitive selection of alternative start sites at the pyrC promoter in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1762938-2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lynch, M., and H. Kuramitsu. 2000. Expression and role of superoxide dismutases (SOD) in pathogenic bacteria. Microb. Infect. 21245-1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKevitt, M. T., K. M. Bryant, S. M. Shakir, J. L. Larabee, S. R. Blanke, J. Lovchik, C. R. Lyons, and J. D. Ballard. 2007. Effects of endogenous d-alanine synthesis and autoinhibition of Bacillus anthracis germination on in vitro and in vivo infections. Infect. Immun. 755726-5734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicholson, W. L., and P. Setlow. 1990. Sporulation, germination and outgrowth, p. 391-450. In C. R. Harwood and S. M. Cutting (ed.), Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., West Sussex, United Kingdom.

- 31.Oliva, C. R., M. K. Swiecki, C. E. Griguer, M. W. Lisanby, D. C. Bullard, C. L. Turnbough, Jr., and J. F. Kearney. 2008. The integrin Mac-1 (CR3) mediates internalization and directs Bacillus anthracis spores into professional phagocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1051261-1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petras, S. F., and L. E. Casida. 1985. Survival of Bacillus thuringiensis spores in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 501496-1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Redmond, C., L. W. Baillie, S. Hibbs, A. J. Moir, and A. Moir. 2004. Identification of proteins in the exosporium of Bacillus anthracis. Microbiology 150355-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Setlow, P. 2003. Spore germination. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6550-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steichen, C., P. Chen, J. F. Kearney, and C. L. Turnbough, Jr. 2003. Identification of the immunodominant protein and other proteins of the Bacillus anthracis exosporium. J. Bacteriol. 1851903-1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steichen, C. T., J. F. Kearney, and C. L. Turnbough, Jr. 2005. Characterization of the exosporium basal layer protein BxpB of Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol. 1875868-5876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steichen, C. T., J. F. Kearney, and C. L. Turnbough, Jr. 2007. Non-uniform assembly of the Bacillus anthracis exosporium and a bottle cap model for spore germination and outgrowth. Mol. Microbiol. 64359-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stewart, B. T., and H. O. Halvorson. 1953. Studies on the spores of aerobic bacteria. I. The occurrence of alanine racemase. J. Bacteriol. 65160-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sylvestre, P., E. Couture-Tosi, and M. Mock. 2002. A collagen-like surface glycoprotein is a structural component of the Bacillus anthracis exosporium. Mol. Microbiol. 45169-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiner, M. A., T. D. Read, and P. C. Hanna. 2003. Identification and characterization of the gerH operon of Bacillus anthracis endospores: a differential role for purine nucleosides in germination. J. Bacteriol. 1851462-1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams, D. D., and C. L. Turnbough, Jr. 2004. Surface layer protein EA1 is not a component of Bacillus anthracis spores but is a persistent contaminant in spore preparations. J. Bacteriol. 186566-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan, X., Y. Gai, L. Liang, G. Liu, and H. Tan. 2007. A gene encoding alanine racemase is involved in spore germination in Bacillus thuringiensis. Arch. Microbiol. 187371-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yasuda, Y., K. Kanda, S. Nishioka, Y. Tanimoto, C. Kato, A. Saito, S. Fukuchi, Y. Nakanishi, and K. Tochikubo. 1993. Regulation of l-alanine-initiated germination of Bacillus subtilis spores by alanine racemase. Amino Acids 489-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]