Abstract

In the light of the recent emergence of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the epidemic of tuberculosis (TB) in populations coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus, and the failure of Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) to protect against disease, new vaccines against TB are urgently needed. Two promising new vaccine candidates are the recombinant ΔureC hly+ BCG (recBCG), which has been developed to replace the current BCG vaccine strain, and modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA) expressing M. tuberculosis antigen 85A (MVA85A), which is a leading candidate vaccine designed to boost the protective efficacy of BCG. In the present study, we examined the effect of MVA85A boosting on the protection afforded at 12 weeks postchallenge by BCG and recBCG by using bacterial CFU as an efficacy readout. recBCG-immunized mice were significantly better protected against aerosol challenge with M. tuberculosis than mice immunized with the parental strain of BCG. Intradermal boosting with MVA85A did not reduce the bacterial burden any further. In order to identify a marker for the development of a protective immune response against M. tuberculosis challenge, we analyzed splenocytes after priming or prime-boosting by using intracytoplasmic cytokine staining and assays for cytokine secretion. Boosting with MVA85A, but not priming with BCG or recBCG, greatly increased the antigen 85A-specific T-cell response, suggesting that the mechanism of protection may differ from that against BCG or recBCG. We show that the numbers of systemic multifunctional cytokine-producing cells did not correlate with protection against aerosol challenge in BALB/c mice. This emphasizes the need for new biomarkers for the evaluation of TB vaccine efficacy.

One-third of the world's population is latently infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. This disease claims 2 million lives every year, and 9 million new cases of active disease occur annually (25). The currently available tuberculosis (TB) vaccine, Mycobacterium bovis BCG, protects against childhood TB meningitis and miliary TB; however, its efficacy wanes with time and it affords only variable protection against pulmonary disease (21). A more-effective TB vaccine is therefore a major global health priority.

Most current efforts to improve the level of protective immunity provided by BCG are focused on regimens that incorporate priming with BCG, recombinant BCG, or other attenuated mycobacteria followed by a heterologous booster immunization that aims to improve the duration and efficacy of the response. Two promising vaccine candidates are recombinant ΔureC hly+ BCG (recBCG), which has been developed to replace the current BCG vaccine strain, and the live vector modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA) expressing the abundant and immunogenic M. tuberculosis antigen 85A (MVA85A) (13), which is a leading booster vaccine.

recBCG is a recombinant urease C-deficient BCG strain expressing the membrane-perforating listeriolysin of Listeria monocytogenes. recBCG significantly improves protection against aerosol challenge with M. tuberculosis H37Rv and the Beijing family genotype over the level provided by the parental BCG strain (7). It has been suggested that listeriolysin promotes antigen translocation into the cytoplasm, as well as apoptosis of infected macrophages, leading to efficient cross-priming and the induction of a stronger CD8 T-cell response (7).

MVA85A induces a strong specific cellular immune response in mice and cattle (14, 18, 22). In BALB/c mice, BCG followed by MVA85A, both given intranasally, induced significantly greater protection following an aerosol M. tuberculosis challenge than did vaccination with BCG alone (6). Ongoing clinical trials show that MVA85A is safe and highly immunogenic in humans (13).

In the present study, we examined the effect of MVA85A boosting on the protection afforded by BCG and recBCG in two independent experiments carried out in two separate laboratories. We also evaluated which characteristics of the immune response induced by the priming or prime-boosting correlated with protection.

(Part of this work represents part of the Ph.D. thesis of Christiane Desel [2].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mycobacterial strains.

The construction of recBCG has been described previously (9). BCG Pasteur 1173P2 (originally provided by B. Gicquel, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) and recBCG were cultured in Dubos broth base supplemented with Dubos albumin medium (Difco; BD Diagnostics, Heidelberg, Germany) at 37°C. Mid-logarithmic cultures were aliquoted and stored at −70°C until use. M. tuberculosis (H37Rv strain, obtained from J. K. Seydel, Forschungsinstitut Borstel, Germany) was grown in Middlebrook 7H9 broth supplemented with BBL Middlebrook ADC enrichment (Difco; BD Diagnostics, Heidelberg, Germany). M. tuberculosis (Erdman strain) was provided by the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), U.S. FDA, Rockville, MD, and used directly from frozen stock.

Animals and immunizations.

The experiments in Oxford were performed with 6- to 8-week-old female BALB/c mice (Harlan Orlac, Blackthorn, United Kingdom), were approved by the animal use ethical committee of Oxford University, and fully complied with the relevant Home Office guidelines. BCG (1 × 105 CFU) and recBCG (1 × 106 CFU) were administered subcutaneously (s.c.) in the left hind footpad in a 30-μl volume.

In Berlin, female 6- to 8-week-old BALB/c mice were bred at the Bundesinstitut für Risikobewertung (BfR), Berlin, Germany, and kept under specific-pathogen-free conditions in filter bonnet cages with food and water ad libitum. Animal experiments were conducted with the approval of the Landesamt für Gesundheit und Soziales (LAGeSo, Berlin, Germany). BCG or recBCG was administered s.c. at the base of the tail at a dose of 1 × 106 CFU in a 100-μl volume.

In both Oxford and Berlin, the MVA85A booster immunization was administered intradermally (i.d.) 10 weeks after BCG or recBCG priming (boosted mice are referred to hereafter as the MB and recMB groups). Mice were anesthetized and immunized i.d. with 25 μl in each ear totaling 50 μl containing 1 × 106 PFU of MVA85A per mouse. The construction, design, and preparation of MVA85A is described in reference 14.

M. tuberculosis aerosol challenge.

Four weeks after the MVA85A booster immunization, mice were challenged by aerosol. In Oxford the challenge was performed with M. tuberculosis strain Erdman, using a modified Henderson apparatus. In Berlin mice were challenged by aerosol with M. tuberculosis strain H37Rv using a Glas-Col inhalation exposure system (Schuett-Biotec; Goettingen, Germany). Deposition in the lungs was measured 24 h after challenge and was ∼200 CFU per lung in both Oxford and Berlin.

Mice were sacrificed 12 weeks after M. tuberculosis challenge. Lungs were homogenized, and the bacterial load was determined by plating 10-fold serial dilutions of tissue homogenates on Middlebrook 7H11 agar plates (E & O Laboratories Ltd., Bonnybridge, United Kingdom) in Oxford or on Middlebrook 7H11 agar plates supplemented with BBL Middlebrook oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase enrichment (Difco; BD Diagnostics, Heidelberg, Germany), ampicillin, and cycloheximide in Berlin. Colonies were counted after 3 to 4 weeks of incubation at 37°C.

Cell isolations and peptides.

In Oxford, spleen cells were cultured in α-minimal essential medium (Sigma-Aldrich, United Kingdom) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, l-glutamine, 2-mercapthoethanol, penicillin, and streptomycin. In Berlin, spleen cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Biochrom) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, l-glutamine, 2-mercapthoethanol, penicillin, and streptomycin.

Cells were stimulated with purified protein derivative (PPD) at 20 μg/ml (SSI, Copenhagen, Denmark) or a pool of 60 15-mer peptides overlapping by 10 amino acids and covering the entire sequence of antigen 85A. Each peptide was used at a final concentration of 8 μg/ml during the stimulation. In some experiments, cells were stimulated with the CD4 (Ag85A99-118aa [TFLTSELPGWLQANRHVKPT]) and CD8 (Ag85A70-78aa [MPVGGQSSF] and Ag85A145-152aa [YAGAMSGL]) dominant peptide epitopes of antigen 85A at 2 μg/ml in Oxford or at 10−5 M in Berlin. Peptides were synthesized by Peptide Protein Research Ltd., Fareham, United Kingdom, or by JPT Peptide Technologies, Berlin, Germany.

Flow cytometry.

Cells harvested from the spleen were stimulated with PPD or pooled 85A peptides for 1 h at 37°C. GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences) was added according to the manufacturer's instructions, and cells were incubated for an additional 5 h before being stained for intracellular cytokines. Cells were washed and incubated with CD16/CD32 monoclonal antibodies to block Fc binding. Subsequently, the cells were stained for CD4, CD8, gamma interferon (IFN-γ), interleukin-2 (IL-2), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (eBioscience) by using a BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were fixed with phosphate-buffered saline-1% paraformaldehyde and run on a CyAN ADP analyzer (Dako, Ely, United Kingdom), and the results analyzed by using FlowJo software. The proportions of multiple-cytokine-producing cells were calculated by using Spice 4.1.6, kindly provided by M. Roederer, Vaccine Research Centre, NIAD, NIH, United States. Cells of three individual mice were analyzed per group. The cytokine frequencies and numbers presented are the values after subtraction of background of identically gated populations of cells from the same sample incubated with medium only.

ELISPOT, cytometric bead array (CBA), and Bio-Plex assays.

The enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) IFN-γ assay was carried out in Oxford as previously described (6), using coating and detecting antibodies from Mabtech Ab, Sweden. Spleen cells were assayed following 18 to 20 h of stimulation with PPD, individual 85A peptides, or peptide pool. Cells from three individual mice were tested in each group, and each condition was tested in duplicate.

For the CBA assays (BD Biosciences), amounts of 2 × 106 splenocytes were stimulated in 200 μl for 18 h with 20 μg/ml PPD or 8 μg/ml pooled 85A peptides. The levels of cytokines in the supernatant were measured by using mouse inflammation and Th1/Th2 CBA assays, following the manufacturer's instructions. Cells from three individual mice were tested for each group. Controls with cells cultured in medium alone were included, and the background cytokine production from these cultures subtracted.

The Bio-Plex bead-based assay (Bio-Rad, Munchen, Germany) was carried out in Berlin. Amounts of 2 × 106 splenocytes were stimulated for 18 h with 50 μg/ml PPD (SSI, Copenhagen, Denmark) or 10−5 M pooled 85A peptides. Cytokines in the supernatants were measured by using Bio-Plex mouse cytokine Th1/Th2 and IL-6 assays according to the manufacturer's instructions. The experimental groups consisted of five mice; two pairs of spleens were pooled, and one was processed individually, resulting in three samples of splenocytes per group of five mice for subsequent stimulation. Controls with cells cultured in medium alone were included, and the background cytokine production from these cultures subtracted.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed by using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. The experiments were performed once in Berlin and once in Oxford.

RESULTS

recBCG improves protection compared to BCG.

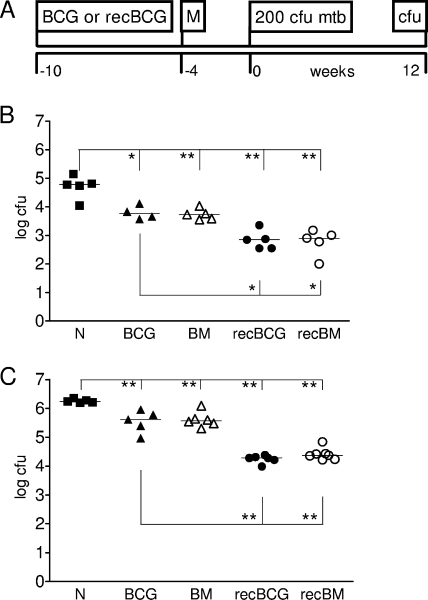

We used MVA85A to boost immunity in mice following BCG or recBCG s.c. priming. The boost was administered i.d. 10 weeks after the administration of BCG or recBCG (Fig. 1A). Aerosol challenge with either M. tuberculosis H37Rv (Berlin) (Fig. 1B) or Erdmann (Oxford) (Fig. 1C) was performed 4 weeks after the final immunization. Bacterial burdens in lungs and spleens were determined 12 weeks after M. tuberculosis challenge. This time point was chosen because recBCG has been shown to increase protection during the late phase of the immune response (7). recBCG increased protection in the lungs by approximately 1 log compared to the protection provided by parental BCG in both laboratories (Fig. 1). A similar increase of 1 log in the protection provided by recBCG over that from parental BCG was observed in the spleen (data not shown). MVA85A i.d. boosting did not increase protection over that afforded by BCG or recBCG in the lung or spleen.

FIG. 1.

RecBCG increases protection over that provided by BCG. BALB/c mice were immunized with BCG or recBCG and, 10 weeks later, boosted with MVA85A (M in panel A and BM or recBM in panels B and C). Naïve mice (N) were used as challenge controls. Mice were challenged with M. tuberculosis by aerosol 4 weeks after the boost and sacrificed 12 weeks later, and lung CFU enumerated. (A) Timeline. (B) Aerosol challenge with 200 CFU M. tuberculosis H37Rv in Berlin. (C) Aerosol challenge with 200 CFU M. tuberculosis Erdman in Oxford. Results are expressed as individual CFU counts, with median values shown by horizontal rules. Asterisks indicate significance (*, P = 0.01 to 0.05; **, P = 0.001 to 0.01).

Multifunctional cytokine responses.

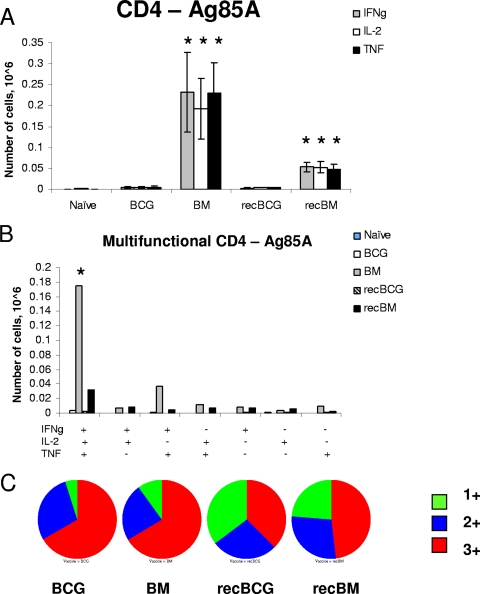

We next studied immune responses to the BCG or recBCG prime-boost immunizations 3 weeks after the boost and 1 week before the M. tuberculosis challenge. Because it has been demonstrated that CD4+ cells simultaneously producing IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α may provide optimal effector function and protection against Leishmania major, another intracellular pathogen, and possibly against M. tuberculosis (1), we defined the proportions of multifunctional cells in our immunized animals. Intracytoplasmic cytokine staining was performed in both laboratories with similar results, and the data from Oxford are presented below.

Antigen 85A responses by CD4 T cells.

We performed intracellular staining for cytokines IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α on splenocytes stimulated with a pool of peptides covering the whole of antigen 85A. MVA85A i.d. boosting induced the strongest 85A-specific CD4 T-cell response after BCG priming (BM group) (Fig. 2A and B). Most cells producing all three cytokines (3+ cells) were detected in the BM group, almost nine times more than in the recBM-immunized mice (180,000 cells versus 20,000). BCG or recBCG alone induced very few splenic 85A-specific CD4 T cells (<5,000).

FIG. 2.

Cytokine responses of splenic CD4 T cells to antigen 85A. Mice were primed with BCG or recBCG and boosted with MVA85A. Splenocytes were isolated 3 weeks after the boost and stimulated with pooled 85A peptides for 6 h. (A) The frequencies of IFN-γ-, IL-2-, and TNF-α-producing cells were determined by flow cytometry of CD4-gated cells. Error bars show standard errors of the means of the results for three mice per group. (B) The frequency of cells expressing each of the seven possible combinations of the cytokines is shown. +, present; −, absent. (C) Pie charts indicate the proportions of 1+, 2+, and 3+ cells, producing IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α. *, P value of <0.05 compared to results with BCG or recBCG; Ag, antigen; IFNg, IFN-γ.

Figure 2C summarizes the proportions of 3+ cells and cells producing either IFN-γ or TNF-α (1+ cells) or both IFN-γ and TNF-α (2+ cells) in the spleen. The BCG- and BM-immunized groups exhibited a much higher proportion of 3+ cells than the recBCG or recBM group. Despite the presence of more 3+ CD4 cells, the BCG and BM groups were less well protected than the recBCG and recBM groups. The administration of MVA85A in the recBCG regimen increased the proportion and absolute number of 3+ CD4 cells but did not improve protection compared to that from recBCG. No consistent pattern of differences between the groups in the levels of cytokine production (median fluorescence indices) was observed (data not shown).

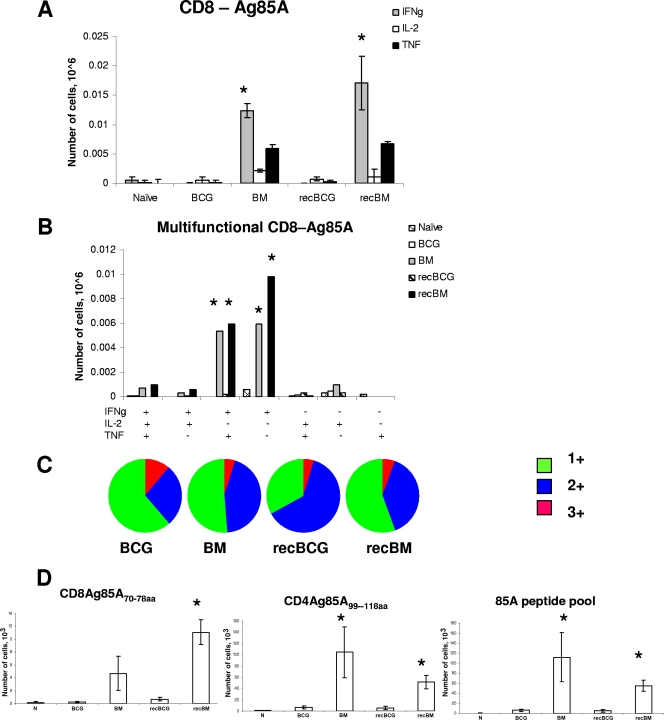

Antigen 85A responses by CD8 T cells.

MVA85A boosting of both parental and recBCG also induced CD8 T-cell responses against antigen 85A (Fig. 3A and B). The majority of the CD8 T cells in the recBM and BM mice were 2+ and 1+; only 0.025% of the CD8 T cells produced IL-2. Although the numbers of multifunctional CD8 T cells were approximately comparable in the BM and recBM groups (∼1,000 3+ and ∼12,000 2+ cells), the CFU in the lungs of these groups differed by 1 log after M. tuberculosis challenge. Furthermore, despite higher proportions and absolute numbers of multifunctional CD8 T cells present in the recBM mice than in the recBCG group, there was no difference in protection between these groups. Similarly, there were more 85A-specific CD8 T cells in the BM group than in the BCG group but no difference between them in protection. The overall quality of the 85A-specific CD8 T-cell response did not differ greatly between the groups (Fig. 3C), with the majority of the cells being 2+ and 1+.

FIG. 3.

Cytokine responses of splenic CD8 T cells to antigen 85A. Splenocytes were isolated 3 weeks after the MVA85A boost and stimulated with pooled 85A peptides for 6 h for ICS. (A) The frequencies of IFN-γ-, IL-2-, and TNF-α-producing cells were determined by flow cytometry on CD8-gated cells. (B) The frequency of cells expressing each of the seven possible combinations of the cytokines is shown. +, present; −, absent. (C) Pie charts indicate the proportions of 1+, 2+, and 3+ cells, producing IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α. (D) IFN-γ ELISPOT assay of splenocytes stimulated for 18 to 20 h with CD4 or CD8 individual peptides or 85A peptide pool. Cells from three individual mice were tested in each group, and each condition was tested in duplicate. Results are expressed as the means ± standard errors of the means of data for three mice per group. N indicates naïve mice. *, P value of <0.05 compared to results with BCG or recBCG; Ag, antigen; IFNg, IFN-γ.

The ability of MVA85A to induce functional CD8 and CD4 T-cell responses was confirmed by ELISPOT assays using the CD8-dominant H-2Ld 85A70-78aa peptide, the CD4 IEd-restricted 85A99-118aa peptide (3, 11), and a peptide pool covering the whole 85A antigen (Fig. 3D). The strongest response was directed against the dominant CD4 peptide, in agreement with previous studies of BALB/c mice (6, 17, 19). It is interesting to note that in the current experiments, in contrast to those reported previously (6), the antigen 85A-specific response differed very little in mice immunized with MVA85A alone and the MB mice (data not shown). The reason for the difference between these results is unclear but could have significance for the lack of enhanced efficacy with MVA85A boosting.

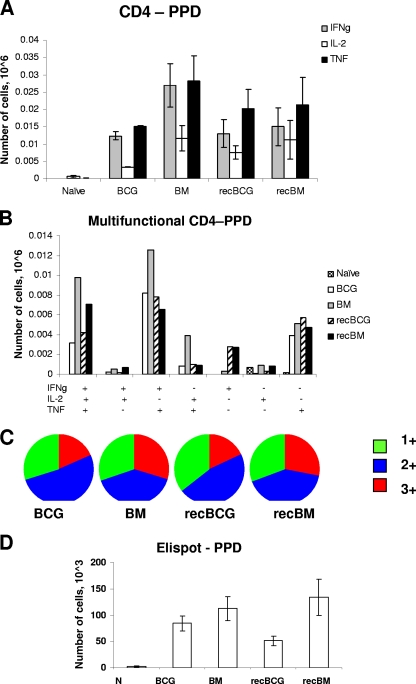

PPD-specific responses.

Following PPD stimulation in vitro, no significant differences in the magnitude and quality of the specific CD4 T-cell responses were detected between the regimens (Fig. 4). Interestingly, the PPD-specific CD4 T-cell response was not significantly boosted by MVA85A, suggesting that although antigen 85A was abundantly produced early during mycobacterial infection (10, 12), neither BCG nor recBCG primed appreciable numbers of antigen 85A-specific T cells in BALB/c mice. Minute numbers of CD8 T cells responding to PPD were detected (data not shown). A similar lack of boosting of the PPD response was observed after the administration of another strongly immunogenic vaccine, antigen 85A-expressing adenovirus, known as Ad85A (5).

FIG. 4.

Cytokine responses to PPD. Splenocytes were isolated 3 weeks after the MVA85A boost and stimulated with PPD for 6 h. (A) The frequencies of IFN-γ-, IL-2-, and TNF-α-producing cells were determined by flow cytometry on CD4-gated cells. (B) The frequency of cells expressing each of the seven possible combinations of the cytokines is shown. (C) Pie charts indicate the proportions of 1+, 2+, and 3+ cells, producing IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α. (D) IFN-γ ELISPOT assay of splenocytes stimulated for 18 to 20 h with PPD. Cells from three individual mice were tested in each group, and each condition was tested in duplicate. Results are expressed as the means ± standard errors of the means of data for three mice per group. N indicates naïve mice. IFNg, IFN-γ.

In a different experiment, we also assessed the immune responses at a later time point, 12 weeks after the boost (data not shown). The number of antigen 85A-specific cells did not change substantially in the spleen, suggesting that an antigen-specific memory T-cell population persisted for at least 3 months after the boost.

In summary, these results show that the magnitude of the response to antigen 85A in the spleen, measured as either the number of IFN-γ-secreting or multifunctional T cells, did not correlate with protection against aerosol challenge with M. tuberculosis in BALB/c mice. Conversely, the response to PPD did not differ between any of the regimens and yet the BCG- and recBCG-primed groups showed significantly different levels of bacterial burdens in the lungs.

Cytokine secretion.

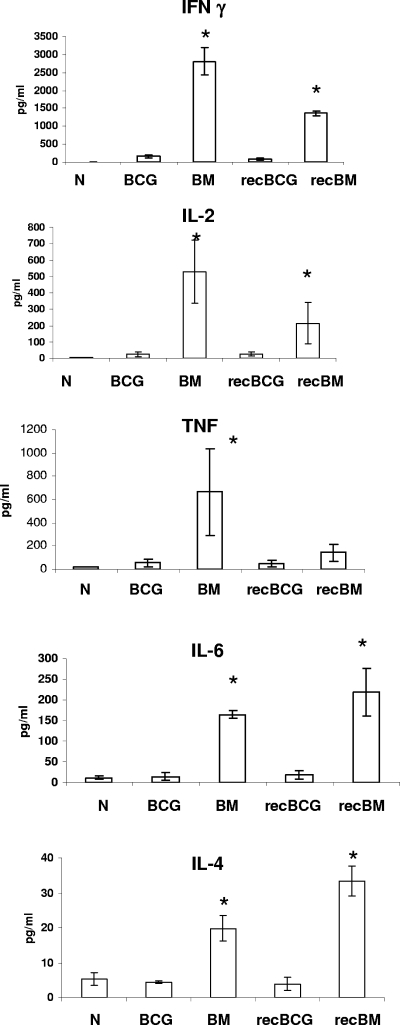

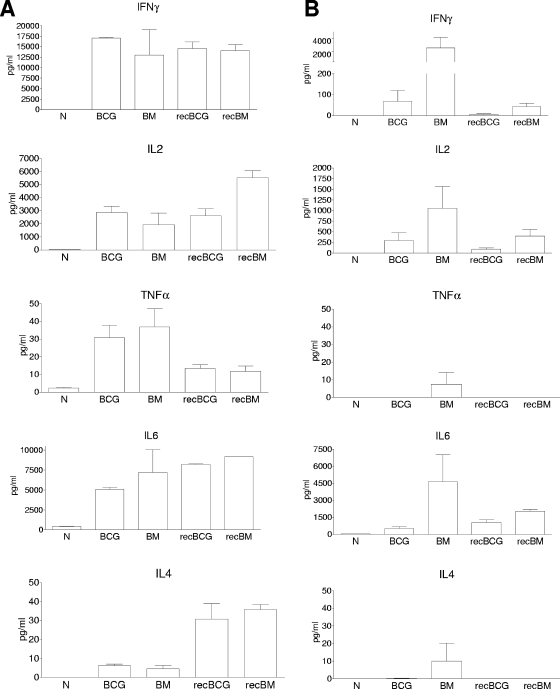

The quality of responses elicited in the spleen was also assessed by measuring the actual secretion of cytokines by CBA or Bio-Plex assay after 18 h of restimulation with the antigen 85A peptide pool or PPD. Boosting with MVA85A of both parental and recBCG induced more IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, IL-4, and IL-6 following antigen 85A stimulation than the other regimens (Fig. 5 and 6B). No significant differences in monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, IL-10, IL-5, or IL-12 production were detected after antigen 85A stimulation (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Spleen cell antigen 85A-specific cytokine responses. Splenocytes were isolated 3 weeks after the boost and stimulated with pooled antigen 85A peptides for 18 h. IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α, IL-4, and IL-6 production was determined by using a CBA assay in Oxford. All data are expressed in pg/ml. Controls with cells cultured in medium alone were included, and the background cytokine production from these cultures subtracted. Shown are the mean values for three mice per group, representative of two independent experiments. Results are expressed as the means ± standard errors of the means of data for three mice per group. N indicates naïve mice. *, P value of <0.05 compared to results with BCG or recBCG.

FIG. 6.

Spleen cell PPD-specific cytokine responses. Splenocytes were isolated 3 weeks after the boost and stimulated with PPD (A) or three antigen 85A peptides (Ag85A99-118aa, Ag85A70-78aa, and Ag85A145-152aa) (B) for 18 h. IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α, IL-4, and IL-6 production were determined by using a Bio-Plex bead-based assay in Berlin. Controls with cells cultured in medium alone were included, and the background cytokine production from these cultures subtracted. Experimental groups consisted of five mice; two pairs of spleens were pooled and one processed individually, resulting in three samples of splenocytes per group of five mice for subsequent stimulation. Results are expressed as the means ± standard errors of the means of data for three samples per group. N indicates naïve mice.

Stimulation with PPD induced higher cytokine production; however, there were no significant differences between the regimens in the production of IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, and TNF-α (Fig. 6A). Low, not significantly different amounts of IL-5, IL-10, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, and IL-12 were also detected (data not shown). It is striking that even though very few PPD-specific cells were detected by intracytoplasmic cytokine staining compared to the numbers of cells specific for antigen 85A, the PPD-stimulated cultures produced an impressive amount of cytokines. This might be due, in part, to the activation by PPD of other than CD4 and CD8 T cells, for example, γδ or NK cells.

DISCUSSION

Our data confirm that recBCG s.c. significantly increases protection compared to BCG 12 weeks after aerosol M. tuberculosis infection in BALB/c mice, in accordance with the results of previous studies in which the vaccines were administered intravenously (7). Boosting with MVA85A i.d. did not increase protection in combination with either BCG or recBCG.

The reduction in bacterial CFU in the lung afforded by the parental BCG was lower than expected in the Oxford experiment (0.7-log reduction versus results for naïve mice, compared to the usual 1.2- to 1.5-log reduction consistently observed in Oxford and seen in the Berlin experiment) (Fig. 1B). This may be because, although it was intended to administer 1 × 106 CFU BCG, subsequent analysis of the administered BCG suspension showed that only 1 × 105 CFU BCG had been given. Although previous studies have shown that the dose and route of application of BCG have a minor impact on vaccine-induced protection (8, 15, 16), it is still possible that the reduced dose did have an effect. However, irrespective of the level of protection afforded by the parental or recBCG, boosting with MVA85A i.d. in both laboratories did not increase BCG- or recBCG-induced protection in the lungs or spleen.

Recently, multifunctional cells have been proposed as a putative correlate of protection against Leishmania major (1). In the same study, multifunctional PPD-specific cells were detected in BCG-vaccinated mice and humans. However, there was no direct evidence that these are important for protection against M. tuberculosis, as no M. tuberculosis challenge was performed. In our experiments, MVA85A boosting induced strong splenic CD4 and, also, weak CD8 T-cell responses against antigen 85A as measured by specific multifunctional cytokine responses (BM and recBM groups). However, this did not parallel increased protection compared to that in the BCG and recBCG groups. In contrast, although there were no differences in the responses to antigen 85A or PPD between the animals immunized with BCG or recBCG only, there was more than 1 log of difference in protection between these two groups. Thus, neither the frequency of PPD- or antigen 85A-specific cells in the spleen nor the presence of multifunctional cells specific for these antigens correlated with protection in either primed or prime-boosted animals.

A similar lack of correlation with systemic IFN-γ responses has been shown following intravenous boosting with MVA85A in a mouse long-term survival experiment (18) or after oral and systemic vaccination with BCG (15). Recent data from BCG-vaccinated cattle also showed that the systemic IFN-γ response did not correlate with protection (23). Increased protection over that conferred by BCG can be achieved by regimens inducing a strong lung immune response. Intranasal immunization with adenovirus-expressing antigen 85A induces a large lung-resident population and significantly increases protection over that from BCG (19, 20). Similarly, intranasal administration of MVA85A increased protection (6) and this correlated with the induction of a large pulmonary CD4 T-cell response. Therefore, the route of administration of the booster vaccine appears to be important in obtaining increased protection over that from BCG or recBCG in mice. In contrast, in monkeys challenged intratracheally with M. tuberculosis and in cows challenged intratracheally with Mycobacterium bovis, i.d. boosting with MVA85A showed improved protection (F. Verreck, A. Hill, and H. McShane, unpublished data; M. Vordermeier, L. G. Hewinson, A. Hill, H. McShane, S. Gilbert, and B. Villerreal, personal communication), suggesting a possible difference between species in the importance of the route of MVA administration. The immunogenicity of i.d. MVA85A boosting, as judged by ELISPOT assays, appears substantially greater in cattle (22), humans (13), and macaques (F. Verreck et al., unpublished data) than in mice (6; this report).

In addition, a rapid accumulation of IFN-γ-secreting CD8 T cells in the lungs after M. tuberculosis challenge has previously been shown to correlate with BCG-induced protection (15). We do not know whether recBCG induces a similar or larger early influx of CD8 T cells, as we did not study early postchallenge events in these animals. However, we did not detect any differences between the lung immune responses in the groups before M. tuberculosis challenge (data not shown). In fact, there were very few antigen-specific T cells in the lungs of either primed or prime-boosted animals. Thus, the mechanism of enhanced protection conferred by recBCG, as well as the mechanism of protection conferred by BCG itself, remains to be determined. While recBCG priming only slightly increased the response to M. tuberculosis antigens measured in vitro, the MVA85A boosting substantially increased the antigen-specific T-cell response, suggesting that its mechanism of protection may differ from that of BCG or recBCG.

The lack of increased protection following boosting with MVA85A may relate to the interval between the BCG prime and the MVA boost or, alternatively, the time between the boost and challenge with M. tuberculosis. In our schedule, both the boost and the challenge are probably during the ongoing immune response to BCG (6) or MVA85A when effector or effector memory cells may be present, while in contrast, there is some evidence that central memory cells are important for protection (24). This needs further exploration.

In summary, in this collaborative study we have demonstrated that recBCG increases protection over that provided by parental BCG, with very similar results obtained in two independent laboratories. Although CD4 T cells and IFN-γ are important components of protection against M. tuberculosis (4), our data suggest that the measurement of systemic short-term in vitro-stimulated IFN-γ or multifunctional cytokine-producing T cells does not correlate with protection against aerosol challenge in BALB/c mice. A better understanding of the mechanisms underlying protection against TB will facilitate the rational design of biomarkers which can serve as surrogates of protection in clinical TB vaccine trials.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the European FP6 integrated project TBVAC to Stefan H. E. Kaufmann and to Adrian V. S. Hill. H.M. and A.V.S.H. are both Jenner Investigators and funded by the Wellcome Trust. H.M. is a Wellcome Trust senior clinical research fellow, and A.V.S.H. is a Wellcome Trust principal research fellow. C.S. was funded by the European Union FP5 framework program project AFTBVAC.

Editor: J. L. Flynn

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 December 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Darrah, P. A., D. T. Patel, P. M. De Luca, R. W. Lindsay, D. F. Davey, B. J. Flynn, S. T. Hoff, P. Andersen, S. G. Reed, S. L. Morris, M. Roederer, and R. A. Seder. 2007. Multifunctional TH1 cells define a correlate of vaccine-mediated protection against Leishmania major. Nat. Med. 13843-850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desel, C. 2008. Evaluation of novel vaccine candidates against tuberculosis in murine models of persistent and latent infection. Ph.D. thesis. Technische Universitaet Berlin, Berlin, Germany.

- 3.D'Souza, S., V. Rosseels, M. Romano, A. Tanghe, O. Denis, F. Jurion, N. Castiglione, A. Vanonckelen, K. Palfliet, and K. Huygen. 2003. Mapping of murine Th1 helper T-cell epitopes of mycolyl transferases Ag85A, Ag85B, and Ag85C from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 71483-493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flynn, J. L., J. Chan, K. J. Triebold, D. K. Dalton, T. A. Stewart, and B. R. Bloom. 1993. An essential role for interferon gamma in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Exp. Med. 1782249-2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forbes, E. K., C. Sander, E. O. Ronan, H. McShane, A. V. Hill, P. C. Beverley, and E. Z. Tchilian. 2008. Multifunctional, high-level cytokine-producing Th1 cells in the lung, but not spleen, correlate with protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis aerosol challenge in mice. J. Immunol. 1814955-4964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goonetilleke, N. P., H. McShane, C. M. Hannan, R. J. Anderson, R. H. Brookes, and A. V. Hill. 2003. Enhanced immunogenicity and protective efficacy against Mycobacterium tuberculosis of bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccine using mucosal administration and boosting with a recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara. J. Immunol. 1711602-1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grode, L., P. Seiler, S. Baumann, J. Hess, V. Brinkmann, A. Nasser Eddine, P. Mann, C. Goosmann, S. Bandermann, D. Smith, G. J. Bancroft, J. M. Reyrat, D. van Soolingen, B. Raupach, and S. H. Kaufmann. 2005. Increased vaccine efficacy against tuberculosis of recombinant Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guerin mutants that secrete listeriolysin. J. Clin. Investig. 1152472-2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gruppo, V., and I. M. Orme. 2002. Dose of BCG does not influence the efficient generation of protective immunity in mice challenged with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinburgh) 82267-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hess, J., D. Miko, A. Catic, V. Lehmensiek, D. G. Russell, and S. H. Kaufmann. 1998. Mycobacterium bovis Bacille Calmette-Guerin strains secreting listeriolysin of Listeria monocytogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 955299-5304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huygen, K., J. Content, O. Denis, D. L. Montgomery, A. M. Yawman, R. R. Deck, C. M. DeWitt, I. M. Orme, S. Baldwin, C. D'Souza, A. Drowart, E. Lozes, P. Vandenbussche, J. P. Van Vooren, M. A. Liu, and J. B. Ulmer. 1996. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a tuberculosis DNA vaccine. Nat. Med. 2893-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huygen, K., E. Lozes, B. Gilles, A. Drowart, K. Palfliet, F. Jurion, I. Roland, M. Art, M. Dufaux, J. Nyabenda, J. De Bruyn, J.-P. Van Vooren, and R. DeLeys. 1994. Mapping of TH1 helper T-cell epitopes on major secreted mycobacterial antigen 85A in mice infected with live Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Infect. Immun. 62363-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lozes, E., K. Huygen, J. Content, O. Denis, D. L. Montgomery, A. M. Yawman, P. Vandenbussche, J. P. Van Vooren, A. Drowart, J. B. Ulmer, and M. A. Liu. 1997. Immunogenicity and efficacy of a tuberculosis DNA vaccine encoding the components of the secreted antigen 85 complex. Vaccine 15830-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McShane, H., A. A. Pathan, C. R. Sander, S. M. Keating, S. C. Gilbert, K. Huygen, H. A. Fletcher, and A. V. Hill. 2004. Recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara expressing antigen 85A boosts BCG-primed and naturally acquired antimycobacterial immunity in humans. Nat. Med. 101240-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McShane, H., S. Behboudi, N. Goonetilleke, R. Brookes, and A. V. Hill. 2002. Protective immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis induced by dendritic cells pulsed with both CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell epitopes from antigen 85A. Infect. Immun. 701623-1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mittrucker, H. W., U. Steinhoff, A. Kohler, M. Krause, D. Lazar, P. Mex, D. Miekley, and S. H. Kaufmann. 2007. Poor correlation between BCG vaccination-induced T cell responses and protection against tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10412434-12439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palendira, U., A. G. Bean, C. G. Feng, and W. J. Britton. 2002. Lymphocyte recruitment and protective efficacy against pulmonary mycobacterial infection are independent of the route of prior Mycobacterium bovis BCG immunization. Infect. Immun. 701410-1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radosevic, K., C. W. Wieland, A. Rodriguez, G. J. Weverling, R. Mintardjo, G. Gillissen, R. Vogels, Y. A. Skeiky, D. M. Hone, J. C. Sadoff, T. van der Poll, M. Havenga, and J. Goudsmit. 2007. Protective immune responses to a recombinant adenovirus type 35 tuberculosis vaccine in two mouse strains: CD4 and CD8 T-cell epitope mapping and role of gamma interferon. Infect. Immun. 754105-4115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romano, M., S. D'Souza, P. Y. Adnet, R. Laali, F. Jurion, K. Palfliet, and K. Huygen. 2006. Priming but not boosting with plasmid DNA encoding mycolyl-transferase Ag85A from Mycobacterium tuberculosis increases the survival time of Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccinated mice against low dose intravenous challenge with M. tuberculosis H37Rv. Vaccine 243353-3364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santosuosso, M., S. McCormick, E. Roediger, X. Zhang, A. Zganiacz, B. D. Lichty, and Z. Xing. 2007. Mucosal luminal manipulation of T cell geography switches on protective efficacy by otherwise ineffective parenteral genetic immunization. J. Immunol. 1782387-2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santosuosso, M., S. McCormick, X. Zhang, A. Zganiacz, and Z. Xing. 2006. Intranasal boosting with an adenovirus-vectored vaccine markedly enhances protection by parenteral Mycobacterium bovis BCG immunization against pulmonary tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 744634-4643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trunz, B. B., P. Fine, and C. Dye. 2006. Effect of BCG vaccination on childhood tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis worldwide: a meta-analysis and assessment of cost-effectiveness. Lancet 3671173-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vordermeier, H. M., S. G. Rhodes, G. Dean, N. Goonetilleke, K. Huygen, A. V. Hill, R. G. Hewinson, and S. C. Gilbert. 2004. Cellular immune responses induced in cattle by heterologous prime-boost vaccination using recombinant viruses and bacille Calmette-Guerin. Immunology 112461-470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wedlock, D. N., M. Denis, H. M. Vordermeier, R. G. Hewinson, and B. M. Buddle. 2007. Vaccination of cattle with Danish and Pasteur strains of Mycobacterium bovis BCG induce different levels of IFNgamma post-vaccination, but induce similar levels of protection against bovine tuberculosis. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 11850-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whelan, A. O., D. C. Wright, M. A. Chambers, M. Singh, R. G. Hewinson, and H. M. Vordermeier. 2008. Evidence for enhanced central memory priming by live Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccine in comparison with killed BCG formulations. Vaccine 26166-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. 2007. Global tuberculosis control—surveillance, planning, financing. WHO Report 2007, WHO/HTM/TB/2007.376. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.