Abstract

The impact of Cryptosporidium parvum infection on host cell gene expression was investigated by microarray analysis with an in vitro model using human ileocecal HCT-8 adenocarcinoma cells. We found changes in 333 (2.6%) transcripts at at least two of the five (6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h) postinfection time points. Fifty-one of the regulated genes were associated with apoptosis and were grouped into five clusters based on their expression patterns. Early in infection (6 and 12 h), genes with antiapoptotic roles were upregulated and genes with apoptotic roles were downregulated. Later in infection (24, 48, and 72 h), proapoptotic genes were induced and antiapoptotic genes were downregulated, suggesting a biphasic regulation of apoptosis: antiapoptotic state early and moderately proapoptotic state late in infection. This transcriptional profile matched the actual occurrence of apoptosis in the infected cultures. Apoptosis was first detected at 12 h postinfection and increased to a plateau at 24 h, when 20% of infected cells showed nuclear condensation. In contrast, experimental silencing of Bcl-2 induced apoptosis in 50% of infected cells at 12 h postinfection. This resulted in a decrease in the infection rate and a reduction in the accumulation of meront-containing cells. To test the significance of the moderately proapoptotic state late in the infection, we inhibited apoptosis using pancaspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK. This treatment also affected the progression of C. parvum infection, as reinfection, normally seen late (24 h to 48 h), did not occur and accumulation of mature meronts was impaired. Control of host apoptosis is complex and crucial to the life of C. parvum. Apoptosis control has at least two components, early inhibition and late moderate promotion. For a successful infection, both aspects appear to be required.

Cryptosporidium parvum is an obligate intracellular apicomplexan parasite and a well-recognized cause of severe diarrheal disease in many mammalian species, including humans (15). It primarily infects epithelial cells of the gastrointestinal tract, resulting in acute and profuse watery diarrhea that is typically self-limited in immunocompetent individuals but persistent and potentially life threatening in immunocompromised hosts (8, 16). Previous in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated (9) that C. parvum infection induces expression of a variety of host immune modulators that activate both the innate and adaptive immune responses, including the accumulation of specific lymphocyte populations within the intestinal villi and increased secretion of several proinflammatory cytokines. Infected cells are structurally affected, as evidenced by polymerization of host cell actins and reorganization of cytoskeleton components (9, 13, 19, 26, 34, 38). Such host responses are accompanied by blunting of intestinal villi, hyperplasia of crypt cells, and decreased sodium absorption (26, 30). On a cellular level, C. parvum infection of epithelial cells is intracellular but extracytoplasmic and requires the establishment of a parasitophorous vacuole.

Apoptosis has been demonstrated to be an important defense mechanism for the host in response to many infections (36, 49). Predictably, many parasites possess the ability to modulate host cell apoptosis (11, 22, 29). Does apoptosis contain Cryptosporidium infection? In natural and experimental infections in vivo, the picture is complex. Apoptosis has been observed in association with infection; however, a simple correlation between pathology and apoptosis does not exist (30, 41). In vitro, Cryptosporidium induces apoptosis in a small minority of the infected cells (5, 33, 35), which is not enough to ward off infection. Cryptosporidium has apparently evolved countermeasures to keep the host cells in a survival mode. Indeed, the infected cells acquire resistance to various chemical agents that trigger apoptosis (6, 28, 33, 35). Additionally, the host appears to be equipped with a second line of defense also involving apoptosis: uninfected bystander cells die due to FasL secreted from the infected cells (5, 6, 33, 35). Cryptosporidium activates the NF-κB pathway in the infected cells and survives, while the host can contain the infection by surrounding the infected cells with a zone of apoptosis.

Here we report genome-wide expression profiling of C. parvum-infected intestinal epithelial cells and the functional significance of host cell apoptosis for the infection process. Our results revealed that parasite infection of host epithelial cells is a complex process involving the regulation of 333 host genes. The largest functional group identified from the microarray included 51 genes that are related to cellular apoptosis. Apoptosis gene transcript profiles suggested that host proapoptotic gene expression is actively downregulated early in infection but is favored at late stages. Experimental induction and inhibition of cell apoptosis altered C. parvum infection and development, suggesting that C. parvum actively subverts host apoptosis in a biphasic manner to complete its life cycle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. parvum infection assays.

C. parvum (Iowa isolate) oocysts were purchased (Bunch Grass Farm, Drury, ID) and stored at 4°C in 2.5% potassium dichromate for up to 3 months. Monolayers of human ileocecal adenocarcinoma cells (HCT-8; ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum as previously described (43, 48). Cells in log phase were plated at 2 × 106 cells per 150- by 25-mm tissue culture dish and infected as previously described (43, 48). Briefly, purified oocysts were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), sterilized in 33% bleach-PBS for 7 min on ice, washed in Hanks' buffered saline solution, and added to HCT-8 cultures. Following a 2-h excystation period at 37°C, cells were washed with warm Hanks' buffered saline solution, and cultures were incubated in C. parvum infection medium consisting of RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum, 35 mg of ascorbic acid, 1.0 mg of folic acid, 4.0 mg of 4-aminobenzoic acid, 2.0 mg of calcium pantothenate, and 0.1 U of insulin per ml (48) for up to 72 h. For Bcl-2 small interfering RNA (siRNA) silencing experiments, the cells were transfected with 100 nM Bcl-2 siRNA duplexes (Ambion, Austin, TX) 48 h prior to parasite infection. For caspase inhibition experiments, 50 μM of Z-VAD-FMK or analog (Z-FA-FMK) (Biovision, Mountain View, CA) was added to the culture medium 2 h before infection.

Microarray hybridization.

At 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h postinfection, total RNA was extracted from infected cells using Trizol reagent (Gibco BRL Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) and poly(A)+ RNA was isolated using oligo(dT) cellulose columns (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). cRNA probes were synthesized from ∼2.0 μg of poly(A)+ RNA, fragmented, and hybridized to an HG-U95Av2 (Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, CA) probe array that contained probe sets for over 12,600 human genes and/or transcripts. Approximately 15 μg of fragmented cRNA was hybridized to the arrays at 45°C for 16 h and was subsequently washed and stained with a streptavidin-phycoerythrin conjugate using the GeneChip Fluidics station protocol EukGE_WS2 (Affymetrix). Each hybridized microarray chip was scanned twice at 3-μm resolution with a confocal scanner (Hewlett-Packard).

Statistical analysis of gene chip data.

Gene expression data obtained from scanning the U95A chips were initially analyzed using the Microarray Suite 5.0 software package (Affymetrix). The fluorescence intensities of each DNA microarray were scaled by a factor of 1,000. A minimum value of 500 was required for genes to be classified as “expressed.” Data analyses were performed using GeneSpring software (version 5.0; Silicon Genetics, Redwood City, CA). The expression signal of each gene in C. parvum-infected cells was normalized to that in the mock-infected sample. As preliminary analysis of single time point measurements of mock-infected samples at 24 h and 72 h revealed no significant changes in gene expression, triplicate 24-h mock-infected samples were used for subsequent analysis. The average change of gene expression in infected cells at a time point was then calculated as the sum of signal values from three replicates divided by the sum of three values from the mock infection samples. Group comparison between C. parvum-infected and mock-infected cells was performed using the Welch analysis of variance parametric test (P value cutoff of 0.05) and the Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate multiple testing correction. Differentially expressed genes were identified as those with an average change of ±1.8-fold (cutoffs of 1.8 and 0.555 for up- and downregulated genes, respectively) at two or more surveyed time points.

Regulated genes were annotated using GeneSpring's “Build Ontology (Go Slims)” constructor, which hierarchically groups genes into meaningful biological categories based on Gene Ontology Consortium classifications. Genes with similar expression profiles were hierarchically clustered using the Quality Threshold cluster algorithm (minimum standard correlation, 0.9).

qRT-PCR analysis of gene expression.

For quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis, poly(A)+ RNA (0.5 μg) was reverse transcribed in a 20-μl reaction mixture primed by random hexamers using Superscript II (200 units; Invitrogen). cDNAs were diluted 1:1,250 in water. For validation of Bcl-2 silencing, 2 μg total RNA was digested with DNase using the RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed in a 20-μl reaction mixture with the Superscript II set (200 units; Invitrogen). Each 15-μl PCR mixture contained 3 μl of the diluted cDNA, SYBR green PCR master mix (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), and gene-specific primers (Table 1) at 50 nM. qRT-PCR analysis was performed on a real-time PCR system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using a two-step PCR protocol with denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 min for 50 cycles. The size of the PCR amplicon and specificity of the amplification were confirmed by visualization on 2% agarose gels. qRT-PCR data were analyzed using the comparative threshold cycle method as described in the Mx3000P real-time PCR system instruction manual (software version 2.0; Stratagene). Expression of each target gene was normalized against the expression of eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1A in the same sample. The relative level of target gene expression, compared to that in mock-infected cells, was determined for each of the genes.

TABLE 1.

Primers for qRT-PCR analysis

| Protein | Cluster | Primers |

|---|---|---|

| EEF1A | Housekeeping | TGTCAAGGATGTTCGTCGTG, GCCTGGATGGTTCAGGATAA |

| P8 | 1 | GCCTGGATGAATCTGACCTC, GTGTTGGCAGCAGCTTCTCT |

| DDIT3 | 1 | GCTCTGATTGACCGAATGGT, TCTGGGAAAGGTGGGTAGTG |

| DSIP1 | 2 | TGGTGGCCATAGACAACAAG, TGCTCCTTCAGGATCTCCAC |

| CEBPB | 2 | AGATGTTCCTACGGGCTTGTT, ACAGACGCCTCTTTTCTCATAG |

| ATF4 | 2 | AACAACAGCAAGGAGGATGC, GCATGGTTTCCAGGTCATCT |

| MT1B | 3 | TCCTGCAAGTGCAAAGAGTG, TGATGAGCCTTTGCAGACAC |

| MT2A | 3 | CTTGCAATGGACCCCAACT, TCTTCTTGCAGGAGGTGCAT |

| MT1X | 3 | GCTTCTCCTTGCCTCGAAAT, CTTGCAGGAGGTGCATTTG |

| MT1G | 3 | CTTGCAATGGACCCCAACT, AGGAGCAGCAGCTCTTCTTG |

| DnaJA1 | 4 | GCTGCAACGGAAGGAAGAT, CCAGTCCTGGTTCTTGGTCT |

| HSPA8 | 4 | TCTGCTGTGGACAAGAGTACG, TCTCAGCTTCCTGGACCATAC |

| HSPCA1 | 4 | TTCACAGATGGGGTAACGTG, TACTTAGGCATCCGGCTTGA |

| AMD | 4 | GCCAGGAAAATTTGTGACCA, TCTGGCAATCAAGACGCTTA |

| STRA13 | 4 | CAAGACCAAAGAAGCAGCAG, CACGGCTGAGATCCCTAGAA |

| CFLAR | 5 | ACAGGAATGTTCTCCAAGCA, AGATCAGGACAATGGGCATA |

| HSPA1 | Unclassified | TGAGCAAGGAGGAGATCGAG, TTCTTGGCTGACACCCTCTC |

Detection of apoptotic cells and C. parvum infection.

Cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.2% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 (in PBS, pH 7.4). Cells were sequentially incubated with primary mouse monoclonal antibody against C. parvum Cp65.10 (1), which recognizes all C. parvum developmental stages, anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated with Cy3, and the nuclear dye 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 10 μg/ml). Samples were observed with an IX70 inverted microscope (40×) (Olympus America, Melville, NY). Cells showing nuclear changes characteristic of apoptosis by DAPI staining were identified and scored. Parasites at different developmental stages were classified into three groups based on their sizes and morphologies in accordance with prior reports (23, 35). Total infection rate, numbers of the parasites with different sizes in the entire parasite population, total apoptotic cells, and the number of apoptotic cells colocalized with parasites were recorded. All treatments were performed in four replicates. More than 2,000 cells from a representative microscopic field were scored for each replication. Medians were compared by rank sum test in pairwise comparisons. With four replicates, if the ranges do not overlap, the medians are significantly different at a P value of 0.05.

Bcl-2 gene silencing by RNA interference.

Chemically synthesized siRNAs for Bcl-2 and control (scrambled) siRNAs corresponding to sequences that did not match any human transcripts were purchased (Ambion, Austin, TX). The sequence of Bcl-2 siRNA targeting is 5′-GGAUUGUGGCCUUCUUUGA-3′. Transfections were performed at approximately 70% confluence in 24-well plates using SiPORT amine transfection agent (Ambion, Austin, TX) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells (2.5 × 105) were seeded in complete growth medium the day before transfection. For each transfection, 3 μl SiPORT amine was diluted into 46 μl Opti-MEM serum-free medium. siRNA-amine complexes were prepared by mixing 1.25 μl of siRNA (20 μm) with 49 μl Opti-MEM serum-free medium containing amine. The final concentration of the siRNA was 100 nM. Transfections were performed in 250 μl of serum-free medium for 24 h. Thereafter, 0.5 ml of fresh medium containing 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum was added to achieve complete growth conditions. In each experiment, untreated controls were included. Bcl-2 knockdown at 24 h and 48 h was confirmed by qRT-PCR using the primers 5′-ATGTGTGTGGAGAGCGTCGTCAA-3′ and 5′-ACAGTTCCACAAAGGCATCC-3′. Cells were infected with C. parvum oocysts 48 h after transfection.

Microarray data accession number.

The array data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and are accessible through GEO series accession number GSE2077.

RESULTS

Transcript profiling of HCT-8 cell gene expression during C. parvum infection.

C. parvum infection of HCT-8 cells proceeds fairly synchronously for the first 24 h. In the present study, intestinal epithelial cell gene expression during C. parvum infection was investigated by oligonucleotide microarray analysis of RNAs isolated from three biologically independent time course experiments at five time points over a 72-h infection period. Of the ∼12,600 genes queried on the Affymetrix HG-U95Av2 probe array, 333 genes (2.6%) showed significantly (P < 0.05) altered expression compared to expression in mock-infected cells, with an average change of at least 1.8-fold at at least two time points. Raw gene expression data and detailed analysis results are accessible online at the GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; GEO accession number GSE2077). Because the largest class of regulated genes were those involved in apoptosis, we focused subsequent experiments on apoptosis-related genes during C. parvum infection.

Apoptosis genes regulated by C. parvum infection.

Of the 333 genes with altered expression following C. parvum infection, 10 genes were apoptosis regulators, including general apoptosis inducer genes (DDIT3, DUSP6, LUC7A, P8, and PHLDA2 genes) and those specifically associated with the death receptor (extrinsic) apoptotic pathway (CFLIP, IER3, and LGALS genes) or the mitochondrial (intrinsic) apoptotic pathway (BBC3 and CYCS genes) (21, 24, 39, 42). An additional 41 transcripts with altered expression patterns during C. parvum infection included genes that have been reported to be associated with apoptotic processes. As shown in Table 2, these genes are typically annotated in other functional groups, such as heat shock and stress response, cell metabolism, nucleic acid binding, signal transduction, and transcriptional regulation. Thus, a total of 51 (15.4%) of the host cell transcripts impacted during C. parvum infection were related to apoptotic processes. An additional 10 transcripts encoding apoptosis-related proteins were altered at least 1.8-fold at single time points (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Apoptosis-related proteins whose genes have altered expression during C. parvum infection in HCT-8 cellsa

| Protein | Description | Role in apoptosis |

|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | ||

| DDIT3 | DNA damage-inducible transcript 3 | Induces growth arrest and apoptosis in response to stress signals or DNA damage |

| P8 | Candidate of metastasis 1 | Induction of apoptosis |

| Cluster 2 | ||

| LAMB1 | Laminin, beta 1 | Induction of apoptosis |

| BBC3 | BCL2 binding component 3 | p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA); binds to Bcl-2 and Bcl-X(L) |

| LGALS8 | Lectin, galactoside binding, soluble, 8 (galectin 8) | Apoptosis regulator activity |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor | Induces phosphorylation of Bcl-2 protein |

| ERBB3 | v-erb-b2 erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 3 protein (avian) | Involved in ErbB2/ErbB3/Akt signaling; inhibition protects cells from UV B-induced apoptosis |

| LGALS1 | Lectin, galactoside binding, soluble, 1 (galectin 1) | Apoptosis regulator activity |

| DSIPI | Delta sleep inducing peptide, immunoreactor | Decreases Bcl-xl expression and promotes apoptosis |

| PPP1R15A | Protein phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 15A | Apoptosis regulator activity |

| BTG1 | B-cell translocation gene 1 protein, antiproliferative | Apoptotic sensitizer that is highly expressed in apoptotic cells |

| CEBPB | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) beta | Induces growth arrest and apoptosis in response to stress signals or DNA damage |

| CEBPG | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) gamma | Induces growth arrest and apoptosis in response to stress signals or DNA damage |

| DDIT4 | DNA damage-inducible transcript 4 | Induces growth arrest and apoptosis in response to stress signals or DNA damage |

| ATF4 | Activating transcription factor 4 (tax-responsive enhancer element B67) | Member of the ATF/CREB family, with both transcription activator and repressor activities |

| Cluster 3 | ||

| MT1B | Metallothionein 1B (functional) | Possible negative regulation of apoptosis |

| MT2A | Metallothionein 2A | Possible negative regulation of apoptosis |

| MT1X | Metallothionein 1X | Possible negative regulation of apoptosis |

| MT1G | Metallothionein 1G | Possible negative regulation of apoptosis |

| MT3 | Metallothionein 3 (growth inhibitory factor) | Possible negative regulation of apoptosis |

| Cluster 4 | ||

| AMD1 | Adenosylmethionine decarboxylase 1 | Inhibits apoptosis via decreasing polyamine availability |

| DNAJA1 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily A, member 1 | Antiapoptotic activities via hsp70-DnaJ chaperone pairing |

| TM4SF1 | Transmembrane 4 superfamily member 1 | Tumor antigen |

| HSPA8 | Heat shock 70-kDa protein 8 | Blocks apoptosis by binding apoptosis protease activating factor 1 (Apf-1) |

| DUSP4 | Dual-specificity phosphatase 4 | Inactivates JNK to inhibit apoptosis progression |

| PCNA | Proliferating cell nuclear antigen | Blocks apoptosis via interaction with the antiapoptotic protein Mcl-1 |

| HSPCA | Heat shock 90-kDa protein 1α | Suppresses Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis by preventing the cleavage of Bid |

| STRA13 | Stimulated by retinoic acid 13 | Inhibits apoptosis via the STAT pathways |

| IL1RN | Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist | Inhibits death receptor-mediated apoptosis via inhibiting the binding of interleukin 1B |

| FGFR1OP | FGFR1 oncogene partner | Positive regulation of cell proliferation |

| DNAJA1 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily A, member 1 | Antiapoptotic activities via hsp70-DnaJ chaperone pairing |

| HSPE1 | Heat shock 10-kDa protein 1 (chaperonin 10) | Inhibits apoptosis via posttranslational modification of Bcl-xl |

| AHSA1 | AHA1, activator of heat shock; 90-kDa protein | Activator of HSP90 |

| TM4SF1 | Transmembrane 4 superfamily member 1 | |

| ANXA2 | Annexin A2 | Ca2+-dependent RNA-binding protein that interacts with c-myc RNA |

| CYCS | Cytochrome c, somatic | Apoptosis regulator activity |

| MYCBP | c-myc binding protein | Stimulates transcription activity of c-myc (induces or inhibits apoptosis through pathways involving p53 and members of the Bcl-2 family) |

| ANXA1 | Annexin A1 | Calcium-dependent proapoptotic effect |

| PHLDA2 | Pleckstrin homology-like domain, family A, member 2 | Involved in Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis via upregulation of Fas expression |

| Cluster 5 | ||

| DUSP5 | Dual-specificity phosphatase 5 | Direct target of p53, downregulating mitogen- or stress-activated protein kinases |

| EGR1 | Early growth response 1 | Induces apoptosis via upregulating p53 expression |

| CFLAR | CASP8 and FADD-like apoptosis regulator | Dual-function regulator for caspase-8 activation and CD95-mediated apoptosis |

| LUC7A | Cisplatin resistance-associated overexpressed protein | Apoptosis regulator activity |

| CSE1L | CSE1 chromosome segregation 1-like (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) | Apoptosis regulator activity |

| DUSP6 | Dual-specificity phosphatase 6 | Strongly tumor suppressive, induces apoptosis |

| Unclassified | ||

| PHLDA1 | Pleckstrin homology-like domain, family A, member 1 | Inhibition of detachment induced apoptosis; also involved in Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis via upregulation of Fas expression in T cells |

| EGR3 | Early growth response 3 | Induces apoptosis via upregulating p53 expression |

| HSPA1A | Heat shock 70-kDa protein 1A | Binds Apf-1 |

| IER3 | Immediate early response 3 | Inhibitor of Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis (target of p53) |

| FOS | v-fos FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog | Member of AP-1 protein family; activated during transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1)-dependent apoptosis |

| FOSB | FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog B | Member of AP-1 protein family; activated during TGF-β1-dependent apoptosis |

All genes encoding the listed proteins showed at least a 1.8-fold change in expression at two or more of five time points examined.

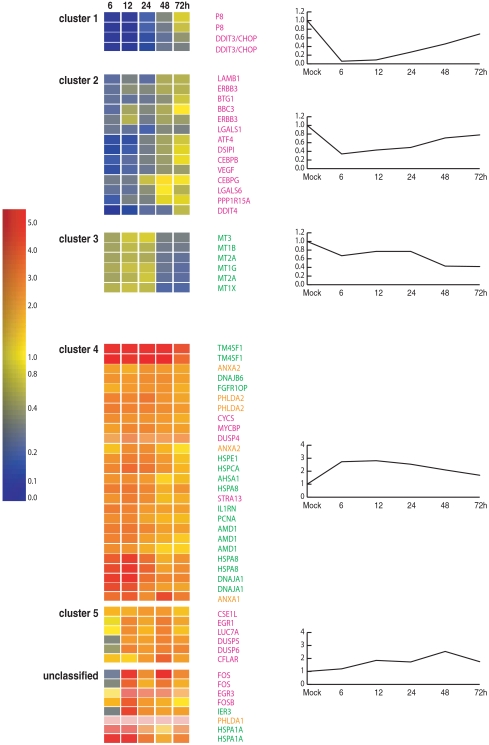

Differentially expressed apoptosis genes were hierarchically clustered based on their expression patterns through the 72-h infection time course (Fig. 1). All of the 21 downregulated genes were grouped into three clusters (clusters 1, 2, and 3), each displaying a distinct expression pattern regardless of the parameters used for clustering. Similarly, 24 upregulated apoptosis genes were consistently grouped into two clusters (clusters 4 and 5). The remaining six genes all showed increased expression but were not clustered.

FIG. 1.

C. parvum-modulated transcripts of apoptosis genes in the host. Shown is relative transcript abundance in infected cultures compared to that in uninfected cultures. The color bar at the left indicates the change (n-fold), and graphs at the right display the average expression profile of genes in the cluster. Genes in pink are proapoptotic genes, genes in green have antiapoptotic roles, and genes in brown have dual roles in apoptosis.

Biphasic regulation of apoptotic genes at different infection times.

As shown in Fig. 1, cluster 1 included two genes that were downregulated greater than 10-fold at early stages of C. parvum infection (6, 12, and 24 h) and then their expression gradually increased through 72 h. Both the P8 and DDIT3/CHOP genes are proapoptotic. Genes in cluster 2 shared a similar expression pattern, but the downregulation was for a shorter period (6 and 12 h only) and was reduced (up to 5-fold versus 50-fold for the DDIT3/CHOP gene in cluster 1) compared to that for cluster 1 genes. All 13 genes in cluster 2 were proapoptotic, including genes encoding apoptosis regulators (LGALS8, LGALS1, and PPP1R15A), proteins interacting with Bcl-2 family proteins (Puma/BBC3, VEGF, and DSIPI), and transcriptional regulators (ATF4, DDIT4, ERBB3, and CEBPB/G) (Table 2). In contrast, genes in cluster 3 were downregulated only at late stages of infection (48 and 72 h) (Fig. 1). All six genes in this cluster encode different members of the metallothionein family, proposed negative regulators of apoptosis (32, 44).

In contrast, cluster 4 contained apoptosis-related genes whose transcript levels were markedly increased in early stages of infection (6 and 12 h) (Fig. 1). Most transcripts returned to normal levels at late stages of infection. Eleven of these genes are reported to have antiapoptotic effects (Table 2), including genes also annotated as heat shock and stress response genes (HSPA8, HSPCA, HSPE1, AHSA1, DnaJA1, and DnaJB6 genes), tumor-associated genes (TM4SF1 and FGFR1OP genes), and genes encoding proteins blocking the death-receptor apoptotic (IL1RN) and mitochondrion-mediated apoptotic (PCNA) pathways. The AMD1 gene also clustered here and is involved in polyamine biosynthesis, which can suppress apoptosis. Note that cluster 4 also included proapoptotic genes, such as the ANXA1, ANXA2, CYCS, MYCBP, STRA13, DUSP4, and PHLDA2 genes.

All six genes in cluster 5 encoded proteins favoring apoptosis progression. Their expression levels slowly increased throughout the in vitro C. parvum life cycle in HCT-8 cells and were moderately upregulated at late stages of infection (48 and 72 h). This cluster included genes encoding two dual-specificity phosphatases (DUSP5 and DUSP6) that can activate apoptosis.

The remaining six genes had unique expression patterns that differed from each other and did not cluster. In general, genes that inhibit apoptosis (FOS, FOSB, HSPA1A, IER3, and PHLDA1 genes) had higher expression levels at early stages of infection, similar to cluster 4 genes. One proapoptotic gene, the EGR3 gene, was unchanged at 6 h but was significantly upregulated thereafter (Table 2; Fig. 1). Taken together, the host transcriptome was indicative of an early (2 to 24 h) antiapoptotic state that became proapoptotic thereafter.

Confirmation of microarray data by qRT-PCR analysis.

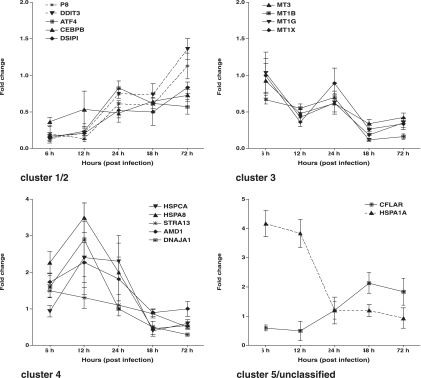

To validate gene expression data generated by microarray analysis, qRT-PCR analysis was conducted for 16 genes selected from all clusters (Fig. 2). Primers for each transcript are shown in Table 1. The expression of five proapoptotic genes, the P8, DDIP3, DSIPI, ATF4, and CEBPB genes from clusters 1 and 2, was downregulated at early stages of infection, whereas the four antiapoptotic metallothionein genes were repressed at late stages, consistent with their respective expression patterns revealed by microarray analysis (Fig. 1). Similarly, the upregulation of three heat shock genes and one additional antiapoptotic gene from clusters 3 and 4 at early stages of C. parvum infection was confirmed, as were the respective expression patterns of the CFLAR (cluster 5) and HSPA1 (unclassified group) genes. In sum, the qRT-PCR results confirmed a biphasic regulation of apoptosis-regulated genes detected by microarrays. The absolute magnitudes but not the overall patterns of differential expression at specific time points determined by qRT-PCR analysis varied from those determined by microarray analysis, reflecting the difference between microarray and qRT-PCR analysis (54).

FIG. 2.

qRT-PCR analysis of apoptosis gene expression in C. parvum-infected cells. Data represent mean changes in gene expression in infected cells relative to that in uninfected cells. Error bars indicate sample standard deviations of three replicate experiments.

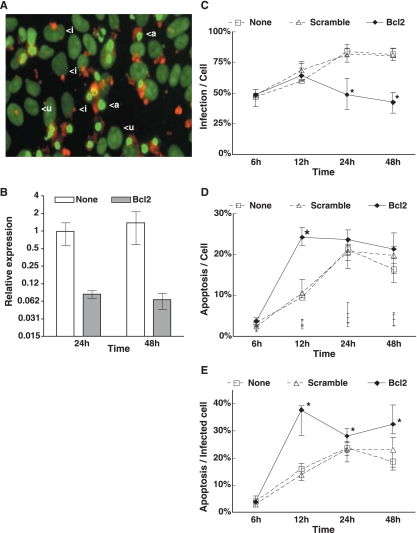

Bcl-2 gene knockdown increases apoptosis and decreases parasite infection.

Bcl-2, the central regulator of apoptosis, is actively regulated in C. parvum-infected epithelial cells (35). Together with BBC3, VEGF, and DSIPI, Bcl-2 may inhibit apoptosis at early infection stages. To assess the biological significance of early apoptosis inhibition on the progression of parasite infection, HCT-8 cells were infected following knockdown of host Bcl-2 gene expression by siRNA silencing. The level of Bcl-2 mRNA in siRNA-treated cultures was less than 10% of that in untreated cells, as confirmed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 3B). Cellular apoptosis and C. parvum were visualized together and quantified by fluorescence microscopy. Apoptosis was detected by chromatin condensation characteristic of late apoptosis in DAPI-stained cells (Fig. 3A). Parasites were detected using a pan-C. parvum monoclonal antibody that recognizes all developmental stages, and stages were classified into three groups based on their morphologies and sizes (23, 35). Uninfected controls with and without siRNA treatment showed less than 3% apoptosis at all time points (Fig. 3D). As shown in Fig. 3A, nonapoptotic cells displayed intact nuclei and diffuse nuclear DNA staining, whereas apoptotic cells were characterized by condensed chromatin and intense DNA staining. These apoptotic bodies were often observed in the focal plane above the monolayer and colocalized with C. parvum. In HCT-8 cells without siRNA treatment, the percentage of C. parvum-infected cells increased from 50% at 6 h to 81% at 48 h (Fig. 3C). In contrast, in cultures where Bcl-2 gene expression was silenced and apoptosis was increased, the percentage of cells infected with C. parvum decreased by 1.4- and 2-fold at 24 h and 48 h, respectively. We conclude that promotion of early apoptosis by Bcl-2 knockdown inhibits C. parvum infection.

FIG. 3.

Bcl-2 knockdown hinders C. parvum infection. (A) Fluorescence micrograph of C. parvum-infected HCT-8 cells in apoptosis. HCT-8 cells were infected by C. parvum (red) for 24 h. Nuclear DNA is visualized in green. <a, infected and apoptotic cell; <i, infected and nonapoptotic cell; <u, uninfected and nonapoptotic cell. Scale bar = 10 μm. (B) Efficiency of Bcl-2 silencing. Relative abundance of Bcl-2 transcripts after siRNA treatment was measured by qRT-PCR. Mean values and standard errors (error bars) from triplicate samples are expressed relative to the values at 24 h with no siRNA treatment (infection only). (C) Frequency of C. parvum-infected cells. (D) Frequency of cells in apoptosis. Only the ranges are shown for the three uninfected control cultures, no treatment, scramble RNA treatment, and Bcl-2 siRNA treatment. The slightly larger ranges at 24 h observed for the uninfected cultures were not specific to Bcl-2 siRNA. (E) Frequency of apoptosis among infected cells. All data points represent medians ± ranges for four replicates. Asterisks indicate that the medians were significantly different (P < 0.05) from those for cells not treated with Bcl-2-specific siRNA. HCT-8 cells were infected at an oocyst-to-host cell ratio of 1:1.

The number of apoptotic cells in infected control cultures increased from 3.1% at 6 h to 22.1% at 24 h, then remained unchanged through 48 h (Fig. 3D). C. parvum-infected cultures treated with scrambled siRNA were not significantly different from cultures subjected to C. parvum infection alone (Fig. 3D and E). Over 95% of apoptotic cells were infected with parasites. However, the percentage of apoptotic cells sharply increased to 50% at 12 h following Bcl-2 siRNA treatment (Fig. 3D and E). Thus, Bcl-2 silencing promotes apoptosis associated with C. parvum infection of HCT-8 cells.

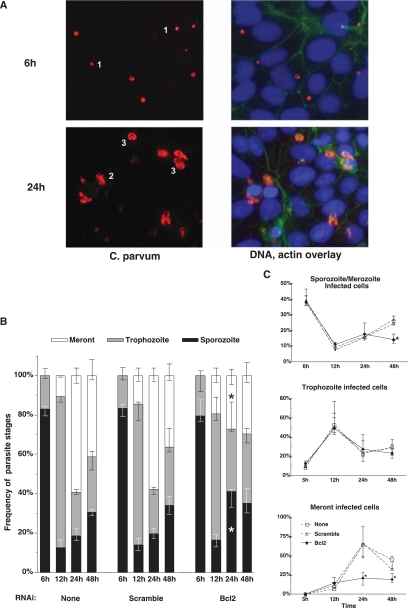

The impact of early apoptosis on C. parvum development was examined. In a normal course of infection, the parasites grow relatively synchronously for the first 24 h. Through 6 h, parasites were largely sporozoites and appear as small, intensely stained structures at the periphery of the cell (Fig. 4A). At 12 h, they had reached predominately trophozoite stage, observable as larger more diffusely stained plaques or ring-like structures. By 24 h, the majority of the parasites became meronts, taking on the appearance of large circular structures with heterogeneous staining (Fig. 4A). Meronts are the product of three mitoses and consist of eight cells termed merozoites. Upon release from the meront, merozoites infect new cells. Merozoites and sporozoites are indistinguishable by morphology; however, small parasites that appear after 24 h are considered merozoites. At 48 h and beyond, the culture consists of one-third each of merozoites, trophozoites, and meronts. Thus, by scoring for morphology and constructing a life history, we can track parasite development (Fig. 4B). Infected-cell cultures treated with Bcl-2 siRNA and control cultures showed similar percentages of each parasite developmental stage through 12 h. However, at 24 h, Bcl-2 gene silencing increased the proportion of sporozoites from roughly 20% to 40%, while meronts decreased to 25%. At 48 h, the proportions of three parasite stages were similar and remained unchanged between 24 h and 48 h in response to Bcl-2 gene silencing. The relative increase in the small parasites at 24 h could be due to the destruction of meronts or due to accelerated release and reinfection of merozoites. The frequency of cells infected by small parasites did not change after 12 h when Bcl-2 was silenced (Fig. 4C), which suggested that the parasites were eliminated by apoptosis. In concordance, we saw no increase in meront-infected cells beyond 12 h (Fig. 4C). These data show that apoptosis of the host cells during early infection inhibits C. parvum development.

FIG. 4.

Bcl-2 knockdown inhibits C. parvum growth. (A, left) Fluorescence micrograph of C. parvum. 1, sporozoites; 2, trophozoites; 3, meronts. (Right) Overlay of nuclear (blue) and actin (green) staining atop parasites (red). (B) Frequency distribution for three parasite stages. Median values of four replicate experiments were converted to percentages. Error bars indicates the ranges. The asterisk indicates that the median value was significantly different from that for cells not treated with Bcl-2-specific siRNA. (C) Infection rate for different parasite stages. All data points represent the medians of four replicates. The error bars indicates the ranges. Asterisks indicate significant differences in the median values compared to no siRNA or scramble siRNA treatment.

Caspase inhibition decreases C. parvum infection and development at low infection dose.

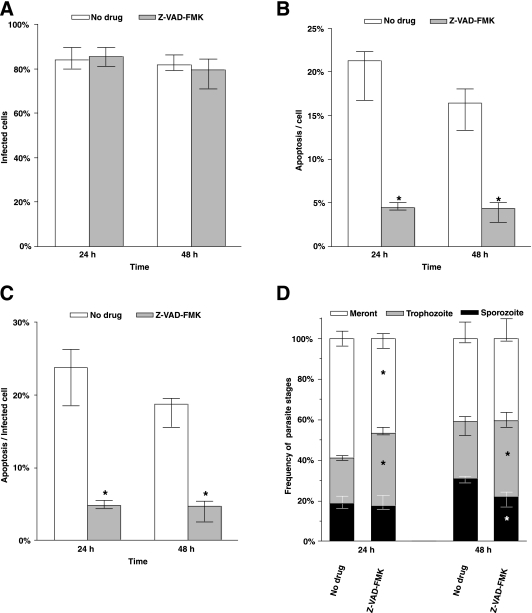

The above data suggested that early induction of cellular apoptosis impedes C. parvum growth and maturation. C. parvum-induced apoptosis of the epithelial cells can be inhibited by caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK (28). We therefore examined the impact of inhibiting apoptosis on C. parvum infection and growth. Cells were treated for 2 h with Z-VAD-FMK prior to infection with C. parvum oocysts at a 1:1 ratio. Initial infection kinetics was not affected by Z-VAD-FMK treatment, as over 80% of cells were infected with parasites at 24 h and 48 h in cultures with or without the caspase inhibitor (Fig. 5A). When the cultures were treated with the caspase inhibitor, the frequency of apoptotic cells sharply decreased to less than 5% at 24 h and 48 h (Fig. 5B and C). Moreover, caspase inhibition changed the ratio of parasites in different developmental stages at 24 h and 48 h (Fig. 5D), resulting in fewer meronts and more trophozoites at 24 h and at 48 h. In addition, a significant reduction (P < 0.05) of small parasites (sporozoites/merozoites) was observed in cells treated with Z-VAD-FMK compared to numbers in control cultures. These data suggested that caspase activation is necessary for C. parvum growth.

FIG. 5.

Effects of caspase inhibition on C. parvum infection. (A) Frequency of infected cells. (B) Frequency of apoptosis in the culture. (C) Frequency of apoptosis among infected cells. (D) Frequency distribution of three parasite stages. Median values of four replicate experiments were converted to percentages. HCT-8 cells were infected at 1:1 (oocysts to host cells). All data points represent medians of four replicate experiments. Error bars indicates the ranges. Asterisks indicate that the median values were significantly different from the values for untreated culture.

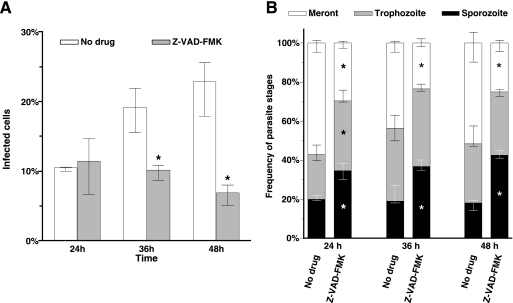

In the previous experiment, we had anticipated that inhibition of apoptosis would promote parasite infection, since more host cells would escape apoptosis, allowing for more parasites to develop and reinfect. To account for the possibility that we did not observe a continuous increase in the number of infected cells because there were insufficient uninfected cells to support reinfection, we performed C. parvum infection at a low (1:10) oocyst-to-HCT-8 ratio. As expected, in cultures without caspase inhibitor treatment, the percentage of infected cells increased during the infection time course, from 10% at 24 h to 23% at 48 h. Surprisingly, when caspases were inhibited, the infection rate plateaued at 12% at 24 h (Fig. 6A), indicating that caspase inhibition hindered C. parvum infection. Based on the cell number increase and morphology, the growth of HCT-8 cells in cultures with caspase inhibitor treatment was similar to that in cultures without treatment (data not shown), and thus host cell growth cannot account for the difference in the infection rate.

FIG. 6.

Caspase inhibition delays C. parvum development. (A) Frequency of infected cells. (B) Frequency distribution for three parasite stages. Median values of four replicate experiments were converted to percentages. HCT-8 cells were infected at 1:10 (oocysts to host cells). All data points represent medians of four replicate experiments. Error bars indicate the ranges. Asterisks indicate that the values were significantly different from the values for untreated culture.

Apoptosis at late infection time points may mechanically facilitate the release of merozoites for reinfection. According to this model, apoptosis inhibition should increase the numbers of meronts (mature parasites) and decrease the numbers of small parasites (merozoites) found within infected cells. In cultures without caspase inhibitor treatment, the percentages of merozoites ranged between 18 and 23% and did not change significantly (P > 0.05) between 24 and 48 h (Fig. 6B). The percentage of trophozoites increased from 21% at 24 h to 32% at 36 h and remained at 31% until 48 h, while the percentages of meronts were 57%, 43%, and 52%, respectively. In contrast, when caspases were inhibited, we observed a significant (P < 0.05) increase in small parasites (sporozoites) at all time points (Fig. 6B). Correspondingly, the percentages of meronts observed were significantly (P < 0.05) lower at all time points compared to percentages for control cultures. The percentage of trophozoites in the parasite population also showed a significant increase at 24 h (36%), but not at 48 h (32%), when caspases were inhibited. These results demonstrated that caspase inhibition did not prevent egress of parasites and reinfection and suggested that blocking apoptosis at later infection times and/or caspase inhibition impaired the normal development of the parasites.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that apoptosis is a critical aspect of the host cell-C. parvum interaction. Genome-wide expression profiling revealed that a high percentage of apoptosis-related genes were regulated during C. parvum infection of intestinal epithelial cells. C. parvum infection is a complex process involving change in 333 host cell genes. The largest functional group identified was 51 genes that are related to apoptosis. Analysis of the apoptosis gene transcript profiles suggests that the balance of apoptotic gene expression is actively downregulated at early infection stages but is upregulated at late stages of infection. Experimental upregulation or downregulation of host cell apoptosis impedes C. parvum infection and development in a manner consistent with biphasic control of host cell apoptosis. These data indicate that C. parvum actively subverts host apoptosis to complete its complex intracellular life cycle.

At 6 h and 12 h postinfection, we observed virtually no apoptosis. Correspondingly, the early transcriptome of infected HCT-8 cells reflected inhibition of apoptosis: mRNAs encoding proapoptotic proteins, including BBC3/Puma, DDIT3/CHOP, and DSIPI, were downregulated, and mRNAs encoding antiapoptotic proteins, such as hsp70, hsp10, DnaJ/hsp40, and hsp90 (27, 40, 47), were rapidly upregulated. In particular, hsp70 and DnaJ block apoptosis by neutralizing apoptosis-inducing factors and by preventing the translocation of Bax to mitochondria (27, 40).

When we experimentally reduced Bcl-2 expression, this induced massive apoptosis at 12 h, reduced infection, and virtually eliminated accumulation of meront stages necessary for subsequent reinfection. Mammalian cells respond to infection by apoptosis mediated by the proapoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family; BBC3/Puma, DSIPI, Bax, Bak, Bim/Bod, and Bad are involved in the mitochondrion-mediated pathway of apoptosis during human immunodeficiency virus, Sendai virus, and Chlamydia trachomatis infection (2, 4, 12, 18, 45, 53, 55). Infection with both hepatitis C virus and Japanese encephalitis virus induces DDIT3/CHOP expression and sensitizes cells to apoptosis by downregulation of Bcl-2 (4, 45). Pathogens have evolved countermeasures to subvert apoptosis immediately. For example, many viruses encode homologs of Bcl-2 to inhibit apoptosis (3, 46, 52). Other pathogens inhibit release of cytochrome c from mitochondria (7, 10, 17, 31, 50, 51) and inhibit caspase activation (25, 37). Since C. parvum required Bcl-2 to inhibit apoptosis, the direct inhibition of Bax and Bak was not the primary mechanism utilized at the early infection stage. More likely, C. parvum reconfigures the transcriptome to affect the strong Bcl-2 block.

We found three positive associations between apoptosis and Cryptosporidium infection: (i) a modest occurrence of apoptosis among infected cells after 24 h, (ii) a shift in the transcriptome of the culture toward the proapoptotic state at 36 to 72 h, and (iii) an inhibition of parasite maturation and infection in response to caspase inhibition. Does this mean a positive role for apoptosis in Cryptosporidium infection? Superficially, the modest 15 to 20% apoptosis, it may be argued, is evidence of a brief moment during infection that we are able to only glimpse because we don't have perfect synchrony in the infection. However, this does not explain why the frequency of apoptosis does not fall after the frequency of meronts falls, nor does it explain the absence of postegress apoptotic cells. We think the modest apoptosis rate is due to the host succeeding in trapping Cryptosporidium in apoptosis. In agreement, Elliott and Clark (14) have shown that, in 100% of the cases, spent host cells die of nonapoptotic death after parasite egress.

The host transcriptome shift toward a proapoptotic state occurs at the time when the culture becomes a mixed-cell population even if we had achieved 100% infection. The culture at this time contains parasites of different ages and dying cells after parasite egress. Since biochemical techniques measure the population average, we cannot distinguish between a global shift in the entire population from the emergence of novel subpopulations that have distinctly different behavior. Except for the period around 24 h, the majority of cells contain young parasites that ought to require protection from apoptosis. Therefore, the small shift toward a proapoptotic transcriptome is probably due to a subpopulation of the cells that arise later in the culture.

Z-VAD-FMK prevented continued spread of infection past 24 h, apparently due to the lack of normal parasite development. We reasoned that, if apoptosis has any positive role for the parasite, it ought to be at a late stage in development near the time of egress. However, Z-VAD-FMK did not trap the parasites as meronts; it hindered the normal maturation of the parasites. We think it is unlikely that Cryptosporidium requires apoptosis; rather we propose a caspase-dependent cellular process in the host that is required for parasite maturation. Alternatively Z-VAD-FMK may inhibit something directly in Cryptosporidium.

The regulatory mechanism involved in parasite infection and host cell apoptosis is complicated. Many pathogens can protect the host cells from apoptosis (11, 20). Is the parasite actively reprogramming the host or just sneaking in? Does the host defense not involve suicide? Stealth strategy by the parasite or passive survival strategy by the host would not depend on Bcl-2, since Bcl-2 knockdown per se did not trigger apoptosis. It was the Cryptosporidium infection that caused the large increase in apoptosis under Bcl-2 depletion. Similarly, it was the infection that caused the overall change in the transcriptome of the culture toward antiapoptosis. We think the host was trying to defend by apoptosis and the parasite was enhancing Bcl-2 to counteract this defense. Between 24 h and 48 h, the merozoites appear and reinfect, resulting in an equal-part mixture of merozoites, trophozoites, and meronts. This was when survivin protects from apoptosis (28). This strong apoptosis inhibition can protect the cells even from staurosporine, yet depletion of survivin or XIAP results in high caspase activity, suggesting that Bcl-2 is not effective at this stage and/or that the caspases were not activated by the mitochondrial pathway. Contrastingly, at 6 h, cells are sensitive to staurosporine, indicating that survivin was not yet able to inhibit the staurosporine-activated pathway and that Bcl-2 cannot protect the cell from the staurosporine-activated pathway. Both sporozoites (at 6 h) and merozoites (after 24 h) need protection from apoptosis, and this requirement is met at least in part by upregulating two different host factors. The host cells may change between 6 h and >24 h by exposure to Cryptosporidium or parasite-infected cells such that, by 24 h, the upstream pathways that sense and activate apoptosis are different. In either case, Cryptosporidium appears capable of inhibiting apoptosis. The 24-h to 48-h period is further complicated: between 20 and 15% cells were apoptotic and contained almost exclusively meronts, and the transcriptome changed slightly toward apoptosis. One can dismiss these small changes by ascribing them to escapes or breakdown of antiapoptosis control. However, the slight increase in the average was likely due to a large increase in a small subset of the cells since most of the time, the exception being a brief period around 24 h, the majority of the parasites are not mature enough to forgo apoptosis inhibition. Furthermore, inhibition of all caspases was clearly inhibitory to parasite development, illustrating the complex adaptation of C. parvum to the ever-changing host cell. Insights into the mechanisms by which C. parvum manipulates apoptosis of infected epithelial cells to complete its life cycle may provide for therapeutic interventions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter Southern for critical reading of the manuscript and the University of Minnesota Imaging Center for their technical help in conducting fluorescence microscopy.

This work was supported in part by grants R01-AI065246-02 from the National Institutes of Health and 99 35204-8614 from the National Research Initiative of the USDA Cooperative State Research, Education and Extension Service.

Editor: J. F. Urban, Jr.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 December 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrahamsen, M. S., C. A. Lancto, B. Walcheck, W. Layton, and M. A. Jutila. 1997. Localization of alpha/beta and gamma/delta T lymphocytes in Cryptosporidium parvum-infected tissues in naive and immune calves. Infect. Immun. 652428-2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen, J. L., J. L. DeHart, E. S. Zimmerman, O. Ardon, B. Kim, G. Jacquot, S. Benichou, and V. Planelles. 2006. HIV-1 Vpr-induced apoptosis is cell cycle dependent and requires Bax but not ANT. PLoS Pathog. 2e127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benedict, C. A., P. S. Norris, and C. F. Ware. 2002. To kill or be killed: viral evasion of apoptosis. Nat. Immunol. 31013-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan, S. W., and P. A. Egan. 2005. Hepatitis C virus envelope proteins regulate CHOP via induction of the unfolded protein response. FASEB J. 191510-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, X. M., G. J. Gores, C. V. Paya, and N. F. LaRusso. 1999. Cryptosporidium parvum induces apoptosis in biliary epithelia by a Fas/Fas ligand-dependent mechanism. Am. J. Physiol. 277G599-G608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, X. M., S. A. Levine, P. L. Splinter, P. S. Tietz, A. L. Ganong, C. Jobin, G. J. Gores, C. V. Paya, and N. F. LaRusso. 2001. Cryptosporidium parvum activates nuclear factor κB in biliary epithelia preventing epithelial cell apoptosis. Gastroenterology 1201774-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark, C. S., and A. T. Maurelli. 2007. Shigella flexneri inhibits staurosporine-induced apoptosis in epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 752531-2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colford, J. M., Jr., I. B. Tager, A. M. Hirozawa, G. F. Lemp, T. Aragon, and C. Petersen. 1996. Cryptosporidiosis among patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Factors related to symptomatic infection and survival. Am. J. Epidemiol. 144807-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deng, M., C. A. Lancto, and M. S. Abrahamsen. 2004. Cryptosporidium parvum regulation of human epithelial cell gene expression. Int. J. Parasitol. 3473-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diao, J., A. A. Khine, F. Sarangi, E. Hsu, C. Iorio, L. A. Tibbles, J. R. Woodgett, J. Penninger, and C. D. Richardson. 2001. X protein of hepatitis B virus inhibits Fas-mediated apoptosis and is associated with up-regulation of the SAPK/JNK pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2768328-8340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DosReis, G. A., and M. A. Barcinski. 2001. Apoptosis and parasitism: from the parasite to the host immune response. Adv. Parasitol. 49133-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elco, C. P., J. M. Guenther, B. R. Williams, and G. C. Sen. 2005. Analysis of genes induced by Sendai virus infection of mutant cell lines reveals essential roles of interferon regulatory factor 3, NF-κB, and interferon but not toll-like receptor 3. J. Virol. 793920-3929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott, D. A., and D. P. Clark. 2000. Cryptosporidium parvum induces host cell actin accumulation at the host-parasite interface. Infect. Immun. 682315-2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elliott, D. A., and D. P. Clark. 2003. Host cell fate on Cryptosporidium parvum egress from MDCK cells. Infect. Immun. 715422-5426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fayer, R. 1997. Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- 16.Fayer, R., U. Morgan, and S. J. Upton. 2000. Epidemiology of Cryptosporidium: transmission, detection and identification. Int. J. Parasitol. 301305-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer, S. F., T. Harlander, J. Vier, and G. Hacker. 2004. Protection against CD95-induced apoptosis by chlamydial infection at a mitochondrial step. Infect. Immun. 721107-1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer, S. F., J. Vier, S. Kirschnek, A. Klos, S. Hess, S. Ying, and G. Hacker. 2004. Chlamydia inhibit host cell apoptosis by degradation of proapoptotic BH3-only proteins. J. Exp. Med. 200905-916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forney, J. R., D. B. DeWald, S. Yang, C. A. Speer, and M. C. Healey. 1999. A role for host phosphoinositide 3-kinase and cytoskeletal remodeling during Cryptosporidium parvum infection. Infect. Immun. 67844-852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hacker, G., and S. F. Fischer. 2002. Bacterial anti-apoptotic activities. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harada, H., and S. Grant. 2003. Apoptosis regulators. Rev. Clin. Exp. Hematol. 7117-138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heussler, V. T., P. Kuenzi, and S. Rottenberg. 2001. Inhibition of apoptosis by intracellular protozoan parasites. Int. J. Parasitol. 311166-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hijjawi, N. S., B. P. Meloni, U. M. Morgan, and R. C. Thompson. 2001. Complete development and long-term maintenance of Cryptosporidium parvum human and cattle genotypes in cell culture. Int. J. Parasitol. 311048-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroemer, G., and J. C. Reed. 2000. Mitochondrial control of cell death. Nat. Med. 6513-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lannan, E., R. Vandergaast, and P. D. Friesen. 2007. Baculovirus caspase inhibitors P49 and P35 block virus-induced apoptosis downstream of effector caspase DrICE activation in Drosophila melanogaster cells. J. Virol. 819319-9330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laurent, F., D. McCole, L. Eckmann, and M. F. Kagnoff. 1999. Pathogenesis of Cryptosporidium parvum infection. Microbes Infect. 1141-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, C. Y., J. S. Lee, Y. G. Ko, J. I. Kim, and J. S. Seo. 2000. Heat shock protein 70 inhibits apoptosis downstream of cytochrome c release and upstream of caspase-3 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 27525665-25671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, J., S. Enomoto, C. A. Lancto, M. S. Abrahamsen, and M. S. Rutherford. 2008. Inhibition of apoptosis in Cryptosporidium parvum infected intestinal epithelial cells is dependent on survivin. Infect. Immun. 763784-3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luder, C. G., U. Gross, and M. F. Lopes. 2001. Intracellular protozoan parasites and apoptosis: diverse strategies to modulate parasite-host interactions. Trends Parasitol. 17480-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lumadue, J. A., Y. C. Manabe, R. D. Moore, P. C. Belitsos, C. L. Sears, and D. P. Clark. 1998. A clinicopathologic analysis of AIDS-related cryptosporidiosis. AIDS (London) 122459-2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Machida, K., K. Tsukiyama-Kohara, E. Seike, S. Tone, F. Shibasaki, M. Shimizu, H. Takahashi, Y. Hayashi, N. Funata, C. Taya, H. Yonekawa, and M. Kohara. 2001. Inhibition of cytochrome c release in Fas-mediated signaling pathway in transgenic mice induced to express hepatitis C viral proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 27612140-12146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McAleer, M. F., and R. S. Tuan. 2001. Metallothionein protects against severe oxidative stress-induced apoptosis of human trophoblastic cells. In Vitro Mol. Toxicol. 14219-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCole, D. F., L. Eckmann, F. Laurent, and M. F. Kagnoff. 2000. Intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis following Cryptosporidium parvum infection. Infect. Immun. 681710-1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDonald, V. 2000. Host cell-mediated responses to infection with Cryptosporidium. Parasite Immunol. 22597-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mele, R., M. A. Gomez Morales, F. Tosini, and E. Pozio. 2004. Cryptosporidium parvum at different developmental stages modulates host cell apoptosis in vitro. Infect. Immun. 726061-6067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moss, J. E., A. O. Aliprantis, and A. Zychlinsky. 1999. The regulation of apoptosis by microbial pathogens. Int. Rev. Cytol. 187203-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nogal, M. L., G. Gonzalez de Buitrago, C. Rodriguez, B. Cubelos, A. L. Carrascosa, M. L. Salas, and Y. Revilla. 2001. African swine fever virus IAP homologue inhibits caspase activation and promotes cell survival in mammalian cells. J. Virol. 752535-2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riggs, M. W. 2002. Recent advances in cryptosporidiosis: the immune response. Microbes Infect. 41067-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rossi, D., and G. Gaidano. 2003. Messengers of cell death: apoptotic signaling in health and disease. Haematologica 88212-218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saleh, A., S. M. Srinivasula, L. Balkir, P. D. Robbins, and E. S. Alnemri. 2000. Negative regulation of the Apaf-1 apoptosome by Hsp70. Nat. Cell Biol. 2476-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sasahara, T., H. Maruyama, M. Aoki, R. Kikuno, T. Sekiguchi, A. Takahashi, Y. Satoh, H. Kitasato, Y. Takayama, and M. Inoue. 2003. Apoptosis of intestinal crypt epithelium after Cryptosporidium parvum infection. J. Infect. Chemother. 9278-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scaffidi, C., S. Fulda, A. Srinivasan, C. Friesen, F. Li, K. J. Tomaselli, K. M. Debatin, P. H. Krammer, and M. E. Peter. 1998. Two CD95 (APO-1/Fas) signaling pathways. EMBO J. 171675-1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schroeder, A. A., A. M. Brown, and M. S. Abrahamsen. 1998. Identification and cloning of a developmentally regulated Cryptosporidium parvum gene by differential mRNA display PCR. Gene 216327-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shimoda, R., W. E. Achanzar, W. Qu, T. Nagamine, H. Takagi, M. Mori, and M. P. Waalkes. 2003. Metallothionein is a potential negative regulator of apoptosis. Toxicol. Sci. 73294-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Su, H. L., C. L. Liao, and Y. L. Lin. 2002. Japanese encephalitis virus infection initiates endoplasmic reticulum stress and an unfolded protein response. J. Virol. 764162-4171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sundararajan, R., and E. White. 2001. E1B 19K blocks Bax oligomerization and tumor necrosis factor alpha-mediated apoptosis. J. Virol. 757506-7516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takayama, S., J. C. Reed, and S. Homma. 2003. Heat-shock proteins as regulators of apoptosis. Oncogene 229041-9047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Upton, S. J., M. Tilley, and D. B. Brillhart. 1995. Effects of select medium supplements on in vitro development of Cryptosporidium parvum in HCT-8 cells. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33371-375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vaux, D. L., G. Haecker, and A. Strasser. 1994. An evolutionary perspective on apoptosis. Cell 76777-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wasilenko, S. T., T. L. Stewart, A. F. Meyers, and M. Barry. 2003. Vaccinia virus encodes a previously uncharacterized mitochondrial-associated inhibitor of apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10014345-14350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Westphal, D., E. C. Ledgerwood, M. H. Hibma, S. B. Fleming, E. M. Whelan, and A. A. Mercer. 2007. A novel Bcl-2-like inhibitor of apoptosis is encoded by the parapoxvirus ORF virus. J. Virol. 817178-7188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Widmer, I., M. Wernli, F. Bachmann, F. Gudat, G. Cathomas, and P. Erb. 2002. Differential expression of viral Bcl-2 encoded by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and human Bcl-2 in primary effusion lymphoma cells and Kaposi's sarcoma lesions. J. Virol. 762551-2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ying, S., B. M. Seiffert, G. Hacker, and S. F. Fischer. 2005. Broad degradation of proapoptotic proteins with the conserved Bcl-2 homology domain 3 during infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect. Immun. 731399-1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yuen, T., E. Wurmbach, R. L. Pfeffer, B. J. Ebersole, and S. C. Sealfon. 2002. Accuracy and calibration of commercial oligonucleotide and custom cDNA microarrays. Nucleic Acids Res. 30e48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhong, Y., M. Weininger, M. Pirbhai, F. Dong, and G. Zhong. 2006. Inhibition of staurosporine-induced activation of the proapoptotic multidomain Bcl-2 proteins Bax and Bak by three invasive chlamydial species. J. Infect. 53408-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]