Abstract

Oral administration of bacterial superantigen Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin B (SEB) activates mucosal T cells but does not cause mucosal inflammation. We examined the effect of oral SEB on the development of mucosal inflammation in mice in the absence of regulatory T (Treg) cells. SCID mice were fed SEB 3 and 7 days after reconstitution with CD4+ CD45RBhigh or CD4+ CD45RBhigh plus CD4+ CD45RBlow T cells. Mice were sacrificed at different time points to examine changes in tissue damage and in T-cell phenotypes. Feeding SEB failed to produce any clinical effect on SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh and CD4+ CD45RBlow T cells, but feeding SEB accelerated the development of colitis in SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells alone. The latter was associated with an increase in the number of CD4+ Vβ8+ T cells expressing CD69 and a significantly lower number of CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ T cells. These changes were not observed in SCID mice reconstituted with both CD45RBhigh and CD45RBlow T cells. In addition, SEB impaired the development of Treg cells in the SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells alone but had no direct effect on Treg cells. In the absence of Treg cells, feeding SEB induced activation of mucosal T cells and accelerated the development of colitis. This suggests that Treg cells prevent SEB-induced mucosal inflammation through modulation of SEB-induced T-cell activation.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic inflammatory condition associated with alteration of immunoregulatory mechanisms responsible for the control of immune responses to commensal microbiotas and their products (15, 34). Under normal conditions, commensal microflora influences the development and function of local and systemic immune responses limiting an overactive inflammatory response (23, 38, 44). Conversely, bacterial pathogens or their products can stimulate both innate and acquired immune responses, resulting in overt acute and chronic mucosal inflammation (22).

Superantigens (SAgs) are microbial proteins that activate large subsets of T or B lymphocytes. Staphylococcal enterotoxins, toxic shock syndrome toxin 1, streptococcal SAg, and Mycoplasma arthritidis mitogen are examples of T-cell SAgs (24, 26, 28). T-cell SAgs bind to the variable region of the T-cell receptor (TCR) β or γ chain and cross-link with the major histocompatibility complex class II molecules (11, 13, 18, 29). Oral administration of Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin B (SEB) induces a transient mucosal T-cell activation followed by persistent anergy and deletion of T cells bearing the SEB-reactive Vβ8 TCR for up to 4 weeks after the treatment (33, 47). Given the large number of SAg-producing microbial agents in the gut flora, it is probable that the mechanism involved in regulation of mucosal immune T-cell responses to microbial SAgs is critical to the prevention of commensal bacterium-induced chronic inflammation (32). Furthermore, SAgs have been implicated in immune-mediated diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, psoriasis, and IBD (25, 26, 39, 40, 50, 51). Skewed TCR repertoires have been identified in patients with IBD (5, 37, 46), and a SAg-like protein derived from Pseudomonas fluorescens, I2, was identified in colonic lesions of over 50% of Crohn's disease patients in a study (8, 10, 14). However, the exact mechanism defining how SAg may contribute to inflammation in the intestinal mucosa is unknown.

Here we investigated the role of regulatory T (Treg) cells in the effect of orally administered SEB on T-cell subsets and on the development of mucosal inflammation. SCID mice were fed SEB after mice were reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells alone or CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells together with CD4+ CD45RBlow T cells. While feeding SEB had no clinical effect on SCID mice reconstituted with both CD4+ CD45RBhigh and CD4+ CD45RBlow T cells, feeding SEB accelerated the development of colitis in SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells alone. This was associated with activation and expansion of SEB-reactive CD4+ Vβ8+ T cells and prevention of the development of T cells expressing Foxp3. These results suggest that Treg cells modulate effector T-cell responses to enteric bacterium-derived SAgs, preventing excessive activation of mucosal T cells and preserving the normal intestinal structure and function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Congenic C.B-17 SCID mice and BALB/c mice were obtained from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN). DO11.10 breeders were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Female mice between 8 and 12 weeks of age were used in these studies. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines as approved by the Animal Care Review Board of McMaster University. All mice were housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions at the central animal facility at McMaster University. Donor and recipient mice in our colony were routinely screened for Helicobacter species infection by PCR capable of detecting ribosomal sequences common to all Helicobacter species and were free of infection (48).

Isolation and purification of CD45RBhigh and CD45RBlow CD4+ spleen cells.

CD4+ T-cell subsets from the spleens of BALB/c and DO11.10 mice were isolated and sorted as described previously (36). Briefly, single-cell suspensions were depleted of B220+, MAC1+, and CD8+ cells by negative selection using M-450 sheep anti-rat immunoglobulin G-coated Dynabeads (Dynal Biotech, Oslo, Norway). Purified anti-CD8α, anti-CD11b, and anti-MAC1 antibodies were obtained from BD PharMingen (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). CD4+ CD45RBhigh and CD4+ CD45RBlow T-cell fractions were sorted on a FACSVantage SE cell sorter (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) under sterile conditions. The purity of each subpopulation was >98%.

Reconstitution of SCID-bg mice with T-cell subsets and SEB treatment.

BALB/c- and DO11.10-derived CD4+ CD45RBhigh and CD4+ CD45RBlow T cells were washed and resuspended at 2 × 106 cells/ml in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Eight- to 12-week-old SCID mice each received either CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells (4 × 105 cells/mouse, intraperitoneally) alone or combined with CD45RBlow CD4+ T cells (2 × 105 cells/mouse) from BALB/c mice or CD4+ CD45RBhigh and CD45RBlow CD4+ T cells from BALB/c and DO11.10 mice or DO11.10 and BALB/c mice, respectively. At 3 and 7 days after T-cell reconstitution and before the onset of colitis in SCID mice that received CD4+ CD45RBhigh cells, recipient SCID mice were fed 10 μg of SEB (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) by gavage (intragastrically) in 200 μl of PBS with 400 μg of soybean trypsin inhibitor (Sigma) or soybean trypsin inhibitor alone in PBS. Mice were euthanized at different points of time after the second administration of SEB.

Histological examination.

To determine if there was a difference in or an effect on the development of chronic colonic inflammation, which usually takes about 6 to 8 weeks, mice were euthanized at the moment at which most animals receiving SEB reached end point or maximum weight loss (i.e., 6 weeks). At the time of harvesting, the colon was opened longitudinally and separated into ascending, transverse, and descending colon and cecum. Tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Each segment was analyzed for the severity of intestinal inflammation and graded by a gastrointestinal pathologist (C.J.S.) on a scale from 0 (no change) to 4 (most severe), as described previously (20). The scores at each segment were combined to provide an overall score of inflammation with a maximum score of 16.

LPL isolation.

Lamina propria lymphocytes (LPL) were prepared as previously described (9). Briefly, the small intestines from a group of four to five mice were removed and the Peyer's patches were carefully excised. For removal of epithelial cells and intraepithelial lymphocytes, the intestines were washed and cut into small pieces, and then the pieces were incubated with calcium- and magnesium-free Hanks' balanced salt solution supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum and 5 mM EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich) on a magnetic stirrer at 37°C for 30 min. This process was repeated three times. The tissues were then incubated with RPMI 1640 containing 10% bovine calf serum, antibiotics, 25 mM HEPES, and 1.5 mg/ml collagenase A (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) for 30 min at 37°C with stirring. The digestion was repeated three times. The isolated cells were pooled and separated on a 40/75% discontinuous Percoll gradient (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) centrifuged at 600 × g and 25°C for 20 min.

Phenotypic analysis by flow cytometry.

For flow cytometry analysis, suspensions of 5 × 105 mononuclear cells were suspended in PBS-0.2% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin supplemented with 0.1% (wt/vol) sodium azide and then incubated with relevant monoclonal antibody for 30 min at 4°C and washed. Three- or four-color flow cytometry acquisition was performed on a FACScan sorter (BD Biosciences). The following reagents and antibodies were obtained from BD PharMingen: fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated hamster anti-CD3ɛ (145-2C-11), phycoerythrin (PE)- and CyChrome-conjugated anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody (L3T4), PE-conjugated CD25 (interleukin-2 [IL-2] receptor α chain, p55), and PE- and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-F23.1 (Vβ8.1-3). Alexa Fluor (488)-conjugated anti-mouse Foxp3 and allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD4 antibody were obtained from Biolegend (San Diego, CA), and PE-Cy5.5-conjugated anti-mouse DO11.10 TCR (KJ1-26) antibody was from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). A total of 5 × 105 events gated on lymphocytes were collected by a FACScan sorter using the CellQuest software, and the data were analyzed with WinList version 5.0 (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME).

T-cell proliferation assays.

For the T-cell proliferation assay, 5 × 105 splenocytes were added to 96-well flat-bottomed tissue culture plates in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) and stimulated with SEB (5 μg/ml) for 72 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. The SAg SEB (5 μg/ml) was used as a stimulator. Cell cultures were pulsed with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine for the last 16 h, and proliferative responses were determined by measuring [3H]thymidine incorporation.

Statistical analysis.

Data were expressed as means ± standard errors of the means (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using the two-tailed Student t test for independent samples. The Mann-Whitney test was used for nonparametric data. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for time course data. The differences between the means of two groups were considered significant when the value of P was <0.05.

RESULTS

Feeding SEB to SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells accelerated onset of colitis.

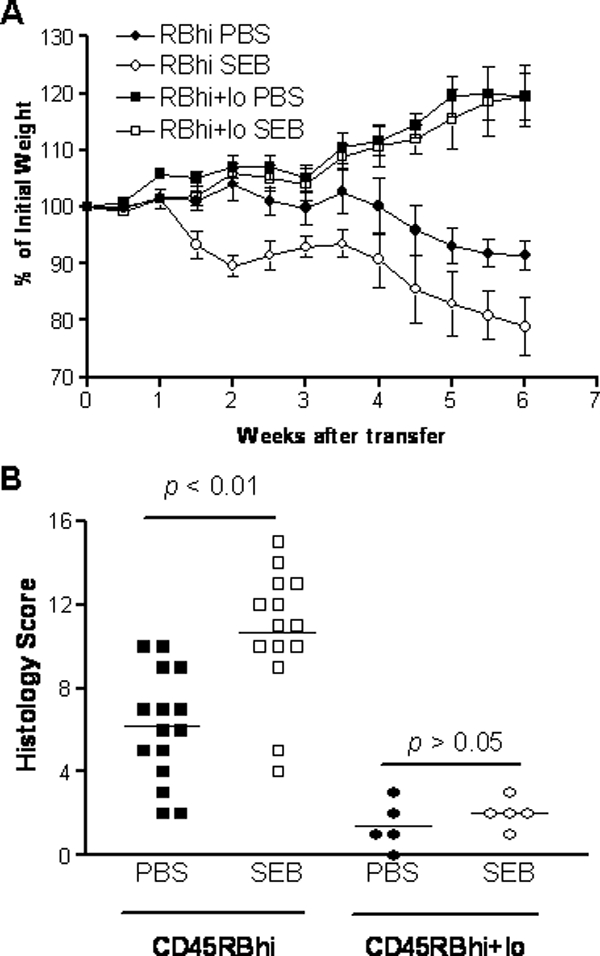

Feeding SEB causes rapid activation and cytokine production by T cells in murine gut-associated lymphoid tissues (47). To examine whether feeding SEB can influence the development of intestinal inflammation, we fed SEB to SCID mice during the first week after reconstitution with BALB/c-derived CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells. Control PBS-fed SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells developed a gradual and persistent weight loss with signs of diarrhea starting around 4 to 5 weeks after cell transfer. These mice developed bloody diarrhea and rectal prolapse by 8 to 10 weeks after reconstitution. The histology of the colon in these mice showed significant epithelial cell hyperplasia, lymphocyte infiltration, goblet cell depletion, and the occasional ulceration and crypt abscess as previously described (27). In contrast, SCID mice reconstituted with BALB/c CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells and fed SEB at days 3 and 7 after reconstitution developed significant weight loss beginning 24 h after the second feeding. The majority of these mice lost 20% of their original body weight within 4 to 6 weeks (Fig. 1A). The differences in body weight gain between SEB-fed and PBS-fed CD4+ CD45RBhigh T-cell recipients were statistically significant (P < 0.05 by ANOVA).

FIG. 1.

Oral SEB activates colitis in SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells. (A) Eight- to 12-week-old female C.B-17 SCID mice were reconstituted with 4 × 105 CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells or 4 × 105 CD4+ CD45RBhigh plus 2 × 105 CD4+ CD45RBlow T cells derived from BALB/c mice. Half of the mice were fed SEB (10 μg/mouse) at days 3 and 7. The changes in weight over time are expressed as percentages of initial body weight. The differences in body weight between SEB-fed and PBS-fed CD4+ CD45RBhigh T-cell recipients were statistically significant (P < 0.05 by ANOVA). SEB feeding had no significant effect on SCID mice reconstituted with both CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells and CD4+ CD45RBlow T cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments with four to five mice in each group. (B) Histological scores of colitis in SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ T-cell subsets from BALB/c mice. Mice were sacrificed 6 weeks after T-cell transfer, and colonic tissues were collected for histology examination. Inflammation was scored for the cecum and the proximal, middle, and distal colon, as described in Materials and Methods. Each data point represents the score of an individual mouse. The bars represents the means of the inflammatory scores for the groups. P < 0.01, SEB-fed versus PBS-fed SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells.

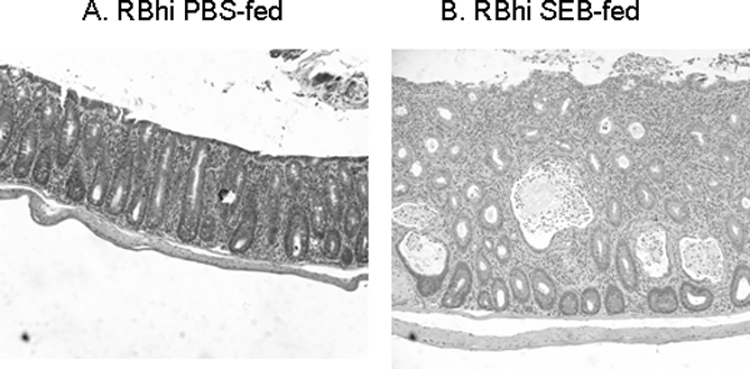

Microscopic examination of the colon showed a significant amplification of colonic inflammation in SEB-fed mice with extensive epithelial hyperplasia, massive lymphocyte infiltration, and numerous crypt abscesses (Fig. 2). Overall histological evaluation of all the segments of the colon showed that feeding SEB was associated with a significant increase in the severity of colitis. The mean histological score was 6.5 ± 1.0 for PBS-fed SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells, whereas the average score for SEB-fed SCID recipients was 11.0 ± 2.0 (Fig. 1B, P < 0.01). Thus, in the absence of Treg cells, feeding SEB to CD45RBhigh T-cell-reconstituted SCID mice caused a more severe colitis.

FIG. 2.

Representative photomicrographs of transverse colon from SCID mice 6 weeks after reconstitution with purified CD4+ CD45RBhigh T-cell subset. Marked increases in epithelial hyperplasia, lymphocyte infiltration, and crypt abscesses were seen in SEB-fed recipients (B) compared with PBS-fed recipients (A). Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Original magnification, ×100.

SEB feeding has no clinical effect on SCID mice reconstituted with both CD4+ CD45RBhigh and CD4+ CD45RBlow T cells.

SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh and CD4+ CD45RBlow T cells do not develop colitis (41). Feeding SEB to SCID mice that received both CD4+ CD45RBhigh and CD4+ CD45RBlow T cells also failed to induce weight loss (Fig. 1A) or histological evidence of inflammation (Fig. 1B). Similar results were observed in SCID mice reconstituted with unseparated CD4+ T cells (data not shown). In fact, repeated oral administration of SEB (10 μg per mouse, twice a week for 4 weeks) to SCID mice reconstituted with combined CD4+ CD45RBhigh and CD4+ CD45RBlow T cells failed to cause weight lose or colitis (data not shown).

Feeding SEB to SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells leads to early activation of T cells in the absence of Treg cells.

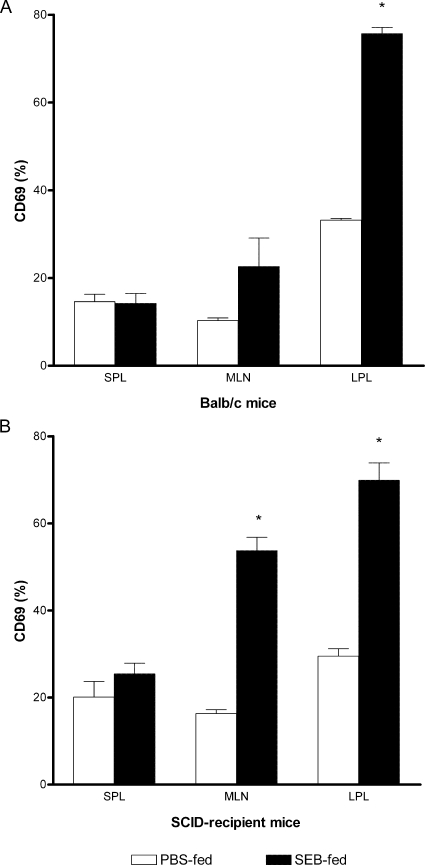

The significant weight loss and clinical signs of colitis seen immediately after the second SEB feeding in SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells suggested that oral SEB caused early T-cell activation. We examined the induction of T-cell early-activation marker CD69 on CD4+ Vβ8+ T cells in the spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN), and LPL from SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells during the first 72 h after the second SEB feeding. In SEB-fed BALB/c mice, a significant increase in the expression of CD69+ was detected on T cells in the LPL and a small but not statistically significant increase was detected in the MLN (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, feeding SEB to SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells alone caused a significant (P < 0.05) increase in the proportion of CD4+ Vβ8+ T cells expressing CD69 in LPL and MLN (Fig. 3B). There was no evidence of increased expression of CD69 on CD4+ Vβ8+ T cells in any of the tissues from SCID mice reconstituted with CD45RBhigh T cells and fed PBS alone, in spite of the development of colitis.

FIG. 3.

Activation of mucosal T cells after SEB feeding of SCID mice reconstituted with CD45RBhigh T cells. Naïve BALB/c (A) or CD45RBhigh T-cell-reconstituted SCID (B) mice were fed SEB or PBS twice as described. Lymphocytes from the spleen (SPL), MLN, or lamina propria were harvested 12 h after the last feeding and stained for three-color flow cytometric analysis. The expression of the activation marker CD69 was analyzed on the gated CD4+ Vβ8+ T-cell subpopulation. The results are expressed as the mean percentage for each group ± SEM. The results shown are representative of two independent experiments with seven to eight mice in each group. *, P < 0.05 versus PBS-fed group.

Feeding SEB induced expansion of CD4+ Vβ8+ T cells in SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells.

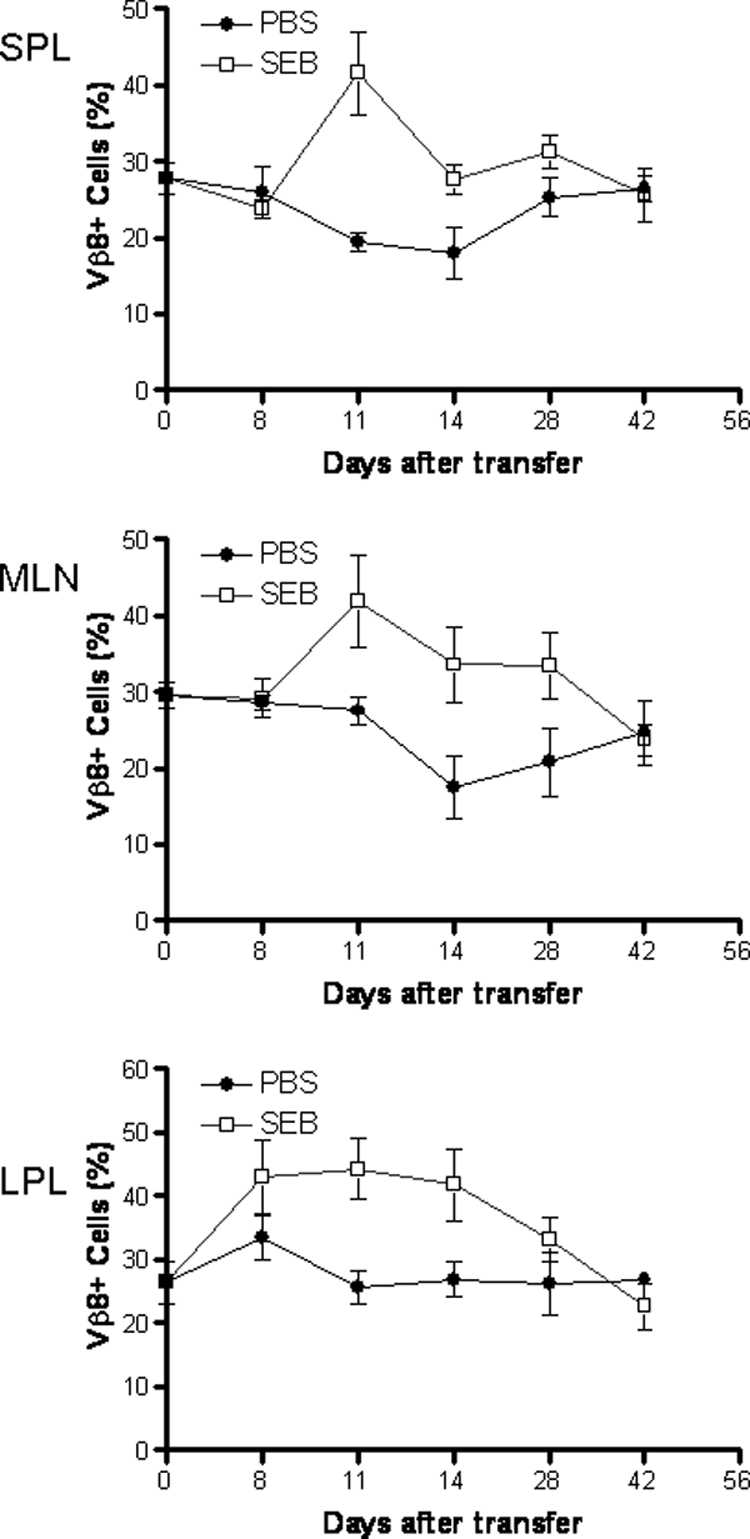

Previous studies showed that oral administration of SEB at high doses (e.g., 50 to 200 μg/mouse) or repeated oral administration of SEB at low doses (e.g., 1 to 10 μg/mouse) to immunocompetent BALB/c mice caused a degree of CD4+ Vβ8+ deletion which recovered within 4 weeks (33, 36, 47). We examined the changes in CD4+ Vβ8+ T cells in both mucosal and peripheral tissues at different time points after feeding SEB. We found that feeding SEB to SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells alone led to an increase in the percentage of CD4+ Vβ8+ T cells in spleen, MLN, and LPL by 12 h after the second feeding, and this remained significantly elevated for at least 4 weeks, while the percentage of CD4+ Vβ8+ T cells in the PBS-fed SCID recipients was unchanged (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Feeding SEB to SCID mice reconstituted with BALB/c CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells leads to expansion of CD4+ Vβ8+ T cells. SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells were fed SEB or PBS, as described. The percentages of CD4+ Vβ8+ T cells in total CD4+ cell populations in the spleen (SPL), MLN, and lamina propria were determined at various time points as indicated after cell reconstitution. CD4+ Vβ8+ T cells from all the examined compartments remained stable in PBS-fed SCID recipients. In contrast, SEB-reactive CD4+ Vβ8+ T cells increased shortly after SEB feeding and remained significantly elevated up to 28 days after transfer before dropping to the same level as that in PBS-fed mice. Data shown are means ± SEM, with n = 3 to 5 for each time point.

CD45RBlow T cells limited CD45RBhigh T-cell expansion in reconstituted SCID mice regardless of SEB administration.

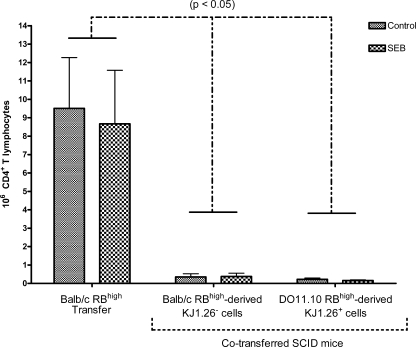

To determine if SEB induced a chronic effect on expansion of RBhigh-derived T cells and if RBlow was effective at controlling expansion of RBhigh T cells in SCID mice receiving both types (2), we examined the effect of SEB on the expansion of CD45RBhigh T cells in vivo, in the presence or absence of CD45RBlow Treg cells after 7 weeks. SCID mice were reconstituted with combined transfers of CD45RBhigh and CD45RBlow T-cell subsets from DO11.10 and BALB/c donor mice. CD4+ T cells from DO11.10 mice possess the transgenic TCR (KJ1-26+) specific for ovalbumin. This TCR has the Vβ8 chain that is reactive with SEB (52) and can be differentiated from the BALB/c TCR by the clonotype-specific monoclonal antibody KJ1-26. The effect of SEB on CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells from BALB/c (BALB/c RBhigh) donors transferred into SCID mice was compared with the effect in mice receiving both BALB/c RBhigh donor cells plus DO11.10 CD4+ CD45RBlow donor cells (DO11.10 RBlow) or DO11.10 RBhigh donor cells combined with BALB/c RBlow donor cells (Fig. 5). SCID recipient mice were fed SEB or PBS at 3 and 7 days after T-cell reconstitution, and the number of CD4+ T cells was estimated using the total number of mononuclear cell counts obtained after collection of spleen and the percentage of CD4+ cells detected in flow cytometry analysis. SEB did not have a chronic effect on total CD4+ T-cell expansion in spleen or MLN from SCID mice reconstituted with RBhigh cells alone or RBhigh and RBlow cells as observed at 7 weeks posttransfer. Furthermore, RBlow cells significantly limited expansion of RBhigh T cells in both SEB- and PBS-fed SCID mice receiving both cell types compared with SCID mice receiving only RBhigh cells.

FIG. 5.

CD45RBlow T cells limited CD45RBhigh T-cell expansion in reconstituted SCID mice regardless of SEB administration. Eight- to 12-week-old female C.B-17 SCID mice were reconstituted with 4 × 105 CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells derived from BALB/c (BALB/c RBhigh single-transfer) mice or 4 × 105 CD4+ CD45RBhigh plus 2 × 105 CD4+ CD45RBlow T cells derived from BALB/c and DO11.10 (BALB/c RBhigh double-transfer) mice, respectively, or DO11.10 and BALB/c (DO11.10 RBhigh double-transfer) mice, respectively. Data shown are means of RBhigh-derived T cells ± SEM, n ≥ 3, and significance was determined at P < 0.05. Lines above error bars indicate significant differences between recipient models within control or SEB-treated mice. No significant differences were observed between SEB-treated mice and PBS-treated controls.

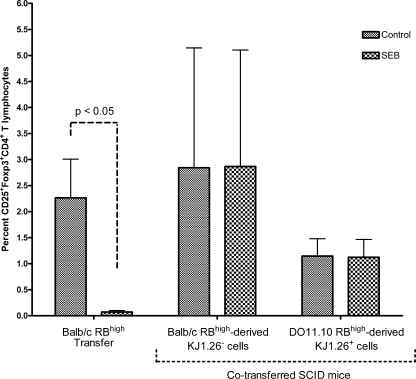

Feeding SEB impaired CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ T-cell development in SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells alone.

In order to determine if the presence of Treg cells modulates the development or function of effector T cells in mice fed SEB, we examined the expression of Treg cell markers in mice receiving donor cells. Feeding SEB significantly decreased the percentages of CD25+ CD4+, Foxp3+ CD4+, and CD25+ Foxp3+ CD4+ T cells in spleens of SCID mice that received BALB/c CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells alone (P < 0.05), suggesting that SEB prevented or delayed development of CD45RBhigh-derived Treg cells (Fig. 6; only CD25+ Foxp3+ double-positive CD4+ T cells are shown). However, SEB failed to alter the percentages of T cells expressing these Treg markers in spleens from SCID mice reconstituted with both RBhigh and RBlow T cells, indicating that Treg RBlow T cells modulated the effect of SEB on RBhigh-derived Treg cells. Moreover, SEB did not affect RBlow-derived Treg cells (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Oral SEB impaired development of CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ T cells in the absence of CD4+ CD45RBlow T cells. Eight- to 12-week-old female C.B-17 SCID mice were reconstituted with 4 × 105 CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells derived from BALB/c (BALB/c RBhigh) mice or 4 × 105 CD4+ CD45RBhigh plus 2 × 105 CD4+ CD45RBlow T cells derived from BALB/c and DO11.10 (BALB/c RBhigh + DO11.10 RBlow) mice, respectively, or DO11.10 and BALB/c (DO11.10 RBhigh + BALB/c RBlow) mice, respectively. Mice were fed SEB (10 μg/mouse) or PBS at days 3 and 7. Data shown are means of RBhigh-derived T cells ± SEM, n ≥ 3, and significance was determined (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The results presented here demonstrated that in the absence of Treg cells, mucosal exposure to a bacterially derived product with SAg activity, i.e., SEB, significantly activated the development of chronic intestinal inflammation. Specifically, oral administration of SEB to SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells was associated with activation of effector CD4+ T cells and expansion of SEB-reactive Vβ8+ T cells. Therefore, in the absence of Treg cells, bacterially derived SAg induced activation and expansion of effector T cells that may have accelerated the onset of colitis. In addition, oral administration of SEB to SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells impaired development of T cells expressing the Treg phenotypes, i.e., T cells expressing CD25+ Foxp3+.

Previous studies suggested that SAg-induced mucosal T-cell stimulation may be implicated in the development of IBD as evidenced by skewed TCR Vβ usage in IBD patients (1, 20). Indeed, systemic administration of the bacterial SAg SEB to mice induces a self-limiting enteropathy (6, 32) with stimulation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (19, 43) and release of tumor necrosis factor alpha, IL-1, IL-2, IL-6, and gamma interferon (26, 28). SAg can also increase proinflammatory cytokine production from both healthy and inflamed colonic mucosa, suggesting that SAg could be an important initiator of the inflammatory cascade through direct T-cell activation (12). Therefore, our finding that feeding SEB accelerated and aggravated colitis in SCID mice reconstituted with RBhigh T cells alone and that oral SEB induced expansion of responsive CD4+ Vβ8+ T cells in SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells provides one mechanism by which mucosal exposure to a SAg can induce mucosal inflammation.

Under normal circumstances interactions between the intestinal microflora and the host immune system are tightly regulated, preventing excessive local inflammation (15, 34). Feeding SAg to immunocompetent mice with normal gut flora fails to induce mucosal inflammation, suggesting that the normal mucosal environment also prevents or modulates the immune response to luminal SAg exposure (16, 31, 35). In addition, direct mucosal administration, e.g., intrarectal administration, of SEB to normal immunocompetent mice failed to induce inflammation (30). These findings support our results showing that feeding SEB to SCID mice reconstituted with combined CD4+ CD45RBhigh and CD4+ CD45RBlow T cells failed to induce T-cell activation or CD4+ Vβ8+ T-cell expansion. Furthermore, oral administration of SEB in naïve BALB/c mice and SCID mice reconstituted with both CD4+ CD45RBhigh and CD4+ CD45RBlow T cells, or unseparated CD4+ T cells, failed to induce any significant intestinal damage. Therefore, mucosal exposure to a SAg in the intestine is not sufficient to cause mucosal inflammation.

Several immune mechanisms, including Treg cells, restrict and regulate the response of the mucosal immune system to mucosal bacterial antigens (16, 35). An alteration of immune regulatory mechanisms in response to microbial products may result in the development of chronic inflammatory diseases such as Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis (7, 49). Our results showed that SEB impaired development of RBhigh-derived Treg cells. However, SEB did not affect Treg cells from the RBlow subset or RBhigh-derived Treg cells in the presence of RBlow. This would suggest that in addition to direct T-cell activation, SEB may alter development and function of RBhigh-derived Treg cells and that this effect is also modulated by the presence of Treg cells. It is not known how SEB affects the development of Treg cells, but it is possible that SEB altered the conversion of naïve T cells into effector T cells, while somehow blocking the expression of Foxp3 and the development of Treg cells. However, it is also likely that the microenvironment (e.g., cytokine and chemokine milieu) promoted by the conversion of naïve T cells into effector T cells might not have allowed for the development of Treg cells (45).

Finally, RBhigh T-cell proliferation or expansion in vivo was limited by the presence of RBlow T cells. In SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells, the number of CD4+ T cells recovered from spleen lymphocytes and MLN at the time of colitis was three to six times higher than that found in SCID mice reconstituted with both CD4+ CD45RBhigh and CD4+ CD45RBlow T-cell subsets (20). Previous studies showed that administration of regulatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10) protected recipient SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells from disease and decreased the number of recovered splenic CD4+ T cells (42). This may partially explain how Treg cells regulated RBhigh T-cell expansion in cotransfer to SCID mice. The finding that germfree mice do not develop oral tolerance to a fed antigen has led to the proposition that commensal microflora is important for the development of Treg cell function involved in the acquisition of tolerance (21). The mechanisms regulating the expansion and survival of CD4+ T cells in a mouse with a normal gut flora may therefore also involve Treg cells (2, 3, 17). Since most animal models of colitis like SCID mice reconstituted with naïve CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells are dependent on the presence of commensal flora (4, 49), the CD4+ T-cell expansion and infiltration into mucosal sites are likely a reflection of bacterial activation.

All together, the observation that mucosal exposure to bacterial SAg activated the development of intestinal inflammation in immunodeficient hosts may explain how gut flora and bacterium-derived products could lead to the development of chronic IBD in immune-dysregulated intestinal mucosa. The current study also demonstrated that Treg cells are critical to the control of T-cell responses to luminal bacterium-derived products and prevent potentially damaging inflammatory responses. In addition, we have demonstrated how SEB can alter Treg development, which contributes to the activation of effector T cells in a dysregulated environment. Therefore, our findings indicated that in the absence of Treg cells, a dysregulated response to SAg could lead to T-cell activation that synergizes with commensal gut flora to initiate and aggravate colitis.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (MOP#74470). Ken Croitoru has received support as an Ontario Minister of Health Career Scientist and as a Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of Canada IBD Scientist. Pengfei Zhou held a scholarship from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Editor: B. A. McCormick

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 December 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aisenberg, J., E. C. Ebert, and L. Mayer. 1993. T-cell activation in human intestinal mucosa: the role of superantigens. Gastroenterology 1051421-1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Annacker, O., O. Burlen-Defranoux, R. Pimenta-Araujo, A. Cumano, and A. Bandeira. 2000. Regulatory CD4 T cells control the size of the peripheral activated/memory CD4 T cell compartment. J. Immunol. 1643573-3580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Annacker, O., R. Pimenta-Araujo, O. Burlen-Defranoux, T. C. Barbosa, A. Cumano, and A. Bandeira. 2001. CD25+ CD4+ T cells regulate the expansion of peripheral CD4 T cells through the production of IL-10. J. Immunol. 1663008-3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aranda, R., B. C. Sydora, P. L. McAllister, S. W. Binder, H. Y. Yang, S. R. Targan, and M. Kronenberg. 1997. Analysis of intestinal lymphocytes in mouse colitis mediated by transfer of CD4+, CD45RBhigh T cells to SCID recipients. J. Immunol. 1583464-3473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baca-Estrada, M. E., D. K. Wong, and K. Croitoru. 1995. Cytotoxic activity of V beta 8+ T cells in Crohn's disease: the role of bacterial superantigens. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 99398-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benjamin, M. A., J. Lu, G. Donnelly, P. Dureja, and D. M. McKay. 1998. Changes in murine jejunal morphology evoked by the bacterial superantigen Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin B are mediated by CD4+ T cells. Infect. Immun. 662193-2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouma, G., and W. Strober. 2003. The immunological and genetic basis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3521-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiba, M., T. Nakamura, S. Hoshina, and Y. Kitagawa. 2001. Optimal cases and sites to search for primary microbial agents in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 1201066-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cong, Y., S. L. Brandwein, R. P. McCabe, A. Lazenby, E. H. Birkenmeier, J. P. Sundberg, and C. O. Elson. 1998. CD4+ T cells reactive to enteric bacterial antigens in spontaneously colitic C3H/HeJBir mice: increased T helper cell type 1 response and ability to transfer disease. J. Exp. Med. 187855-864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalwadi, H., B. Wei, M. Kronenberg, C. L. Sutton, and J. Braun. 2001. The Crohn's disease-associated bacterial protein I2 is a novel enteric T cell superantigen. Immunity 15149-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dellabona, P., J. Peccoud, J. Kappler, P. Marrack, C. Benoist, and D. Mathis. 1990. Superantigens interact with MHC class II molecules outside of the antigen groove. Cell 621115-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dionne, S., S. Laberge, C. Deslandres, and E. G. Seidman. 2003. Modulation of cytokine release from colonic explants by bacterial antigens in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 133108-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drake, C. G., and B. L. Kotzin. 1992. Superantigens: biology, immunology and potential role in disease. J. Clin. Immunol. 12149-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elson, C. O. 2000. Commensal bacteria as targets in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 119254-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elson, C. O., and Y. Cong. 2002. Understanding immune-microbial homeostasis in intestine. Immunol. Res. 2687-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fagarasan, S., and T. Honjo. 2003. Intestinal IgA synthesis: regulation of front-line body defences. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 363-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freitas, A. A., and B. Rocha. 2000. Population biology of lymphocytes: the flight for survival. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1883-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herman, A., J. W. Kappler, P. Marrack, and A. M. Pullen. 1991. Superantigens: mechanism of T-cell stimulation and role in immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 9745-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herrmann, T., and H. R. MacDonald. 1993. The CD8 T cell response to staphylococcal enterotoxins. Semin. Immunol. 533-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibbotson, J. P., and J. R. Lowes. 1995. Potential role of superantigen induced activation of cell mediated immune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of Crohn's disease. Gut 361-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang, H. Q., M. C. Thurnheer, A. W. Zuercher, N. V. Boiko, N. A. Bos, and J. J. Cebra. 2004. Interactions of commensal gut microbes with subsets of B- and T-cells in the murine host. Vaccine 22805-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufmann, S. H., and U. E. Schaible. 2005. Antigen presentation and recognition in bacterial infections. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1779-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly, D., S. Conway, and R. Aminov. 2005. Commensal gut bacteria: mechanisms of immune modulation. Trends Immunol. 26326-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kilpatrick, D. C. 1999. Mechanisms and assessment of lectin-mediated mitogenesis. Mol. Biotechnol. 1155-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kotzin, B. L., D. Y. Leung, J. Kappler, and P. Marrack. 1993. Superantigens and their potential role in human disease. Adv. Immunol. 5499-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lavoie, P. M., J. Thibodeau, F. Erard, and R.-P. Sekaly. 1999. Understanding the mechanism of action of bacterial superantigens from a decade of research. Immunol. Rev. 168257-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leach, M. W., A. G. Bean, S. Mauze, R. L. Coffman, and F. Powrie. 1996. Inflammatory bowel disease in C.B-17 scid mice reconstituted with the CD45RBhigh subset of CD4+ T cells. Am. J. Pathol. 1481503-1515. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, H., A. Llera, E. L. Malchiodi, and R. A. Mariuzza. 1999. The structural basis of T cell activation by superantigens. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17435-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Licastro, F., L. J. Davis, and M. Morini. 1993. Lectins and superantigens: membrane interactions of these compounds with T lymphocytes affect immune responses. Int. J. Biochem. 25845-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu, J., A. Wang, S. Ansari, R. M. Hershberg, and D. M. McKay. 2003. Colonic bacterial superantigens evoke an inflammatory response and exaggerate disease in mice recovering from colitis. Gastroenterology 1251785-1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macpherson, A. J., and T. Uhr. 2004. Induction of protective IgA by intestinal dendritic cells carrying commensal bacteria. Science 3031662-1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKay, D. M. 2001. Bacterial superantigens: provocateurs of gut dysfunction and inflammation? Trends Immunol. 22497-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Migita, K., and A. Ochi. 1994. Induction of clonal anergy by oral administration of staphylococcal enterotoxin B. Eur. J. Immunol. 242081-2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagler-Anderson, C. 2001. Man the barrier! Strategic defences in the intestinal mucosa. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 159-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagler-Anderson, C., A. K. Bhan, D. K. Podolsky, and C. Terhorst. 2004. Control freaks: immune regulatory cells. Nat. Immunol. 5119-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishimura, M., Y. Fujiyama, M. Niwakawa, T. Sasaki, and T. Bamba. 2002. In vivo cytokine responses in gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) and spleen following oral administration of staphylococcal enterotoxin B. Immunol. Lett. 8177-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogawa, H., H. Ito, A. Takeda, S. Kanazawa, M. Yamamoto, H. Nakamura, Y. Kimura, K. Yoshizaki, and T. Kishimoto. 1997. Universal skew of T cell receptor (TCR) V beta usage for Crohn's disease (CrD). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 240545-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ouwehand, A., E. Isolauri, and S. Salminen. 2002. The role of the intestinal microflora for the development of the immune system in early childhood. Eur. J. Nutr. 41(Suppl. 1)I32-I37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paliard, X., S. G. West, J. A. Lafferty, J. R. Clements, J. W. Kappler, P. Marrack, and B. L. Kotzin. 1991. Evidence for the effects of a superantigen in rheumatoid arthritis. Science 253325-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Posnett, D. N., I. Schmelkin, D. A. Burton, A. August, H. McGrath, and L. F. Mayer. 1990. T cell antigen receptor V gene usage. Increases in V beta 8+ T cells in Crohn's disease. J. Clin. Investig. 851770-1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Powrie, F., M. W. Leach, S. Mauze, L. B. Caddle, and R. L. Coffman. 1993. Phenotypically distinct subsets of CD4+ T cells induce or protect from chronic intestinal inflammation in C.B-17 scid mice. Int. Immunol. 51461-1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Powrie, F., M. W. Leach, S. Mauze, S. Menon, L. B. Caddle, and R. L. Coffman. 1994. Inhibition of Th1 responses prevents inflammatory bowel disease in scid mice reconstituted with CD45RBhi CD4+ T cells. Immunity 1553-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quaratino, S., G. Murison, R. E. Knyba, A. Verhoef, and M. Londei. 1991. Human CD4−CD8+αβ+ T cells express a functional T cell receptor and can be activated by superantigens. J. Immunol. 1473319-3323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rakoff-Nahoum, S., and R. Medzhitov. 2006. Role of the innate immune system and host-commensal mutualism. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 3081-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Samanta, A., B. Li, X. Song, K. Bembas, G. Zhang, M. Katsumata, S. J. Saouaf, Q. Wang, W. W. Hancock, Y. Shen, and M. I. Greene. 2008. TGF-beta and IL-6 signals modulate chromatin binding and promoter occupancy by acetylated FOXP3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10514023-14027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saubermann, L. J., C. S. Probert, A. D. Christ, A. Chott, J. R. Turner, A. C. Stevens, S. P. Balk, and R. S. Blumberg. 1999. Evidence of T cell receptor beta-chain patterns in inflammatory and noninflammatory bowel disease states. Am. J. Physiol. 276G613-G621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spiekermann, G. M., and C. Nagler-Anderson. 1998. Oral administration of the bacterial superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin B induces activation and cytokine production by T cells in murine gut-associated lymphoid tissue. J. Immunol. 1615825-5831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Streutker, C. J., C. N. Bernstein, V. L. Chan, R. H. Riddell, and K. Croitoru. 2004. Detection of species-specific helicobacter ribosomal DNA in intestinal biopsy samples from a population-based cohort of patients with ulcerative colitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42660-664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strober, W., I. J. Fuss, and R. S. Blumberg. 2002. The immunology of mucosal models of inflammation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20495-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sutton, C. L., J. Kim, A. Yamane, H. Dalwadi, B. Wei, C. Landers, S. R. Targan, and J. Braun. 2000. Identification of a novel bacterial sequence associated with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 11923-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Torres, B. A., and H. M. Johnson. 1998. Modulation of disease by superantigens. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 10465-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou, P., R. Borojevic, C. Streutker, D. Snider, H. Liang, and K. Croitoru. 2004. Expression of dual TCR on DO11.10 T cells allows for ovalbumin-induced oral tolerance to prevent T cell-mediated colitis directed against unrelated enteric bacterial antigens. J. Immunol. 1721515-1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]