Abstract

Bacillus subtilis yabE encodes a predicted resuscitation-promoting factor/stationary-phase survival (Rpf/Sps) family autolysin. Here, we demonstrate that yabE is negatively regulated by a cis-acting antisense RNA which, in turn, is regulated by two extracytoplasmic function σ factors: σX and σM.

Extracytoplasmic function (ECF) σ factors often regulate gene expression in response to environmental stresses that affect the cell envelope (12). In Bacillus subtilis, there are seven ECF σ factors. The best understood are σM, σW, and σX, which control partially overlapping regulons related to cell envelope homeostasis and antibiotic resistance.

As a class, ECF σ factors recognize structurally similar promoters characterized by a conserved AAC motif in the −35 region (12, 21). In previous studies, we have defined consensus sequences for σM, σW, and σX (2, 8, 17, 18, 30). Promoters recognized by one or more of these three σ factors (designated PECF) generally conform to the consensus TGwAAC-N16-CGwCta (where w represents A or T and lowercase letters indicate residues that are less highly conserved) or TGwAAC-N16-CGTAta (preferentially recognized by σW). Since these three σ factors recognize overlapping sets of promoters, it is typically not possible to assign a given candidate promoter to one or another regulon by sequence alone (3, 16, 30, 38). In addition to conservation within these core (−35 and −10) recognition elements, active promoters are often associated with AT-rich upstream promoter elements (UP elements), and the spacer region adjacent to the −35 element often has a T-rich sequence (12).

In previous studies, we have focused our attention on those candidate PECF elements upstream of coding sequences (2, 17, 18). Here, we report the identification of a PECF downstream of and convergent with the yabE gene. YabE is a cell wall binding protein with similarity in its N-terminal domain to Mycobacterium tuberculosis RpfB (31). The C terminus of YabE contains an Sps (stationary-phase survival) domain in place of the Rpf domain, and YabE has been designated the founding member of the SpsB subfamily of muralytic enzymes (31). Rpf/Sps family proteins function as resuscitation-promoting factors that can restore growth to dormant cells, presumably by catalyzing peptidoglycan cleavage to allow renewed cell wall growth (5, 20). The bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study

| Bacterial strain, plasmid, or primer | Description or primer designation and sequencea (5′-3′) | Reference and/or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| B. subtilis | ||

| CU1065 | W168 SPβatt trpC2 | 40; lab stock |

| HB0020 | CU1065 sigW::mls | Lab stock |

| HB0031 | CU1065 sigM::kan | Lab stock |

| HB0047 | CU1065 rsiX::spc | Lab stock |

| HB0097 | CU1065 sigM::kan sigX::spc | Lab stock |

| HB7007 | CU1065 sigX::spc | Lab stock |

| HB4773 | CU1065 amy::PECF-lacZ | This study |

| HB4774 | HB7007 amy::PECF-lacZ | This study |

| HB4775 | HB0047 amy::PECF-lacZ | This study |

| HB4779 | HB0020 amy::PECF-lacZ | This study |

| HB4780 | HB0031 amy::PECF-lacZ | This study |

| HB4782 | HB0097 amy::PECF-lacZ | This study |

| HB5339 | CU1065 yocH::kan | Lab stock |

| HB4784 | CU1065 yabE::spc | This study |

| HB4785 | CU1065 yuiC::mls | This study |

| HB4786 | CU1065 yocH::kan yabE::spc yuiC::mls | This study |

| E. coli DH5α | φ80dlacZΔM15 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 relA1 deoR Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 | Lab stock |

| Plasmids | ||

| pDG1661 | Vector for integration of lacZ fusions at amyE locus | 9 |

| pWE23 | PECF-lacZ in pDG1661 | This study |

| pMAD | Vector for allelic replacement | 1 |

| pWE24 | yabE-FLAG gene in pMAD | This study |

| Primers | ||

| 3382 | PECF-fwd-HindIII; CCCAAGCTTCCTCCAAGACAAAATAAAAAC | |

| 3383 | PECF-rev-BamHI; CGGGATCCCATTCCGCTAGGCTCCAAAG | |

| 3592 | ECF-GSP1; GGCAAGCTGCAGCGGTTGTT | |

| 3593 | ECF-GSP2; CAGCGACAGGCGTCAATTTA | |

| 3933 | yabE-GSP1; CGTCCATGTCTGCTGTTATC | |

| 3934 | yabE-GSP2; GCAGGTGTGATCTTGTCTTC | |

| 3539 | yabE-specific probe; CGTAGTCGAAGTCGTCCAGATCTTCTTTTGTTTCCCTGCATCATTCACAGTAACCTGAAA | |

| 3541 | Antisense strand-specific probe; GGGAAATAAAACAGTCAAAATTAAAATCTTAAATTAGTATATACTTATGTATTCAGAGGG | |

| 3772 | yabE-up-fwd-EcoRI; CGGAATTCGTCACCGATGTAGTTGAAGA | |

| 3543 | yabE-up-FLAG-rev; TTATTTATCATCATCATCTTTATAATCCGGCCGATTTAAGATTTTAATTTTGA | |

| 3544 | yabE-do-FLAG-fwd; CGGCCGGATTATAAAGATGATGATGATAAATAATATATACTTATGTATTCAGA | |

| 3826 | yabE-do-rev-NcoI; ATACCATGGCTCAGCTGAAATGTCACTCGG | |

| 3546 | yabE-up-fwd; GGAAGACTTAGCGTGGATTA | |

| 3547 | yabE-up-rev (spec); CGTTACGTTATTAGCGAGCCAGTCGTCAACCCTCCCTTCTCTTT | |

| 3548 | yabE-do-fwd (spec); CAATAAACCCTTGCCCTCGCTACGGCGATTAAAGGGAACAAGAT | |

| 3549 | yabE-do-rev; GGTATCGAGCGCACTCATAA | |

| 3935 | yuiC-up-fwd; CACATGATCTGACTTTATTG | |

| 3936 | yuiC-up-rev (mls); GAGGGTTGCCAGAGTTAAAGGATCGGTCATCAGCAAACGTCTGA | |

| 3937 | yuiC-do-fwd (mls); CGATTATGTCTTTTGCGCAGTCGGCGCAAGTGTTCAGAAATCAAT | |

| 3938 | yuiC-do-rev; GCTCTGATTGTTGAACCGCA |

Restriction sites are underlined.

Rpf proteins in the actinobacteria are the best understood. Rpf was originally discovered as a secreted protein that restores growth to dormant Micrococcus luteus cells and was subsequently found to be encoded by an essential gene (26, 28). In Corynebacterium glutamicum, Rpf proteins are dispensable but an rpf1 rpf2 double-mutant strain displays a prolonged lag phase when exiting from stationary phase (10). Rpf proteins in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which encodes five members of this protein family (29), are the most well known. A mutant lacking all five proteins still grows well in vitro but is defective in the restoration of growth after stationary phase (19). Strains lacking one or more Rpf proteins are also defective in animal models of tuberculosis (7, 32, 36). The RpfB protein is particularly important, as evidenced by the delayed reactivation of the single rpfB mutant observed previously (36). RpfB interacts with a peptidoglycan endopeptidase, RipA, at cell division sites (13, 14). In contrast with those in the actinobacteria, the roles of Rpf/Sps family proteins in the low-GC-content gram-positive bacteria are poorly understood. Based on sequence comparisons, it is likely that these proteins, like their actinobacterial homologs (5, 27, 35), function as peptidoglycan hydrolases (autolysins). Specifically, the Sps domain of YabE corresponds to the conserved 3D domain (named for three conserved Asp residues) that constitutes the catalytic site of the Escherichia coli MltA lytic transglycosylase (37).

Pattern searches for PECF elements performed using the SubtiList database identified a sequence downstream of and convergent with the yabE gene (Fig. 1A) that is highly conserved in other Bacillus strains (Fig. 1B). To determine if this putative promoter (PECF) was active, this DNA region was amplified from B. subtilis chromosomal DNA and cloned into pDG1661, which contains a promoterless lacZ gene (9). The resulting plasmid was digested with ScaI and introduced by transformation into the B. subtilis CU1065 wild type (40). An overnight culture was diluted 1:100 in 50 ml of Luria-Bertani (LB) medium and grown at 37°C with vigorous shaking, and the β-galactosidase activity was monitored during growth as described previously (24). PECF activity peaked in the late-logarithmic-phase cells (Fig. 2A).

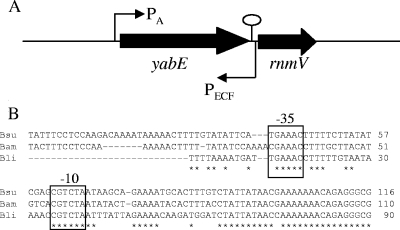

FIG. 1.

(A) Organization of yabE and the downstream PECF element. Promoter sites are indicated by bent arrows with a subscript to indicate the relevant holoenzyme(s). A putative transcription terminator downstream of yabE is indicated by an oval. RnmV is an RNase M5/primase-related protein involved in the maturation of the 5S rRNA (6). (B) Alignment of PECF elements from various bacilli. The intergenic region between yabE and rnmV of B. subtilis (Bsu) was aligned with the corresponding sequences from B. amyloliquefaciens (Bam) and B. licheniformis (Bli) by using the ClustalW2 program (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw2/index.html). The putative −10 and −35 regions are indicated. The run of seven A residues near the end of the sequence shown corresponds to the run of U residues in the yabE transcription terminator.

FIG. 2.

(A) Growth phase regulation of PECF. The β-galactosidase activity of the PECF-lacZ fusion in the wild type (CU1065) was assayed during growth in LB medium, with samples taken every 1 h for the measurement of the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) and the β-galactosidase activity. Solid squares represent growth at an optical density at 600 nm, while solid triangles represent β-galactosidase activity. (B) Mapping of the transcriptional start sites of yabE and ECF-directed antisense transcripts by the rapid amplification of cDNA 5′ ends. The putative −10 and −35 regions are underlined. The transcription start sites are in bold, and the translation start site is italicized. PA is the promoter corresponding to σA. Met indicates the start codon (methionine).

We verified the transcriptional start sites for both yabE and the PECF-directed antisense transcript by the rapid amplification of cDNA 5′ ends. Total RNA was isolated from the wild-type strain at the time of maximal expression (∼3 h) by using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). After DNase treatment, 2 μg of RNA was used as a template for reverse transcription using Multiscribe reverse transcriptase (Taqman; Roche) and a gene-specific primer (GSP1). The resulting cDNA was purified and ligated to a poly(dC) tail with terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase (New England Biolabs). The resulting cDNA was amplified by PCR using the poly(dG) primer to anneal at the poly(dC) tail and a second gene-specific primer (GSP2) complementary to a region upstream of GSP1. PCR products were separated by gel electrophoresis and sequenced. The resulting start site for the PECF is consistent with the assigned −35 and −10 elements (Fig. 2B). Unexpectedly, the yabE start site was at position +60 downstream of the assigned TTG start codon. This start site corresponds to a consensus σA promoter (11) with −35 (TTGACA) and −10 (TATAAT) elements (Fig. 2B). This promoter sequence is also conserved among closely related bacilli, as is a downstream ATG start codon (data not shown). These findings, together with sequence comparisons between YabE and other orthologs, suggest that the translation start codon of this gene was misannotated previously.

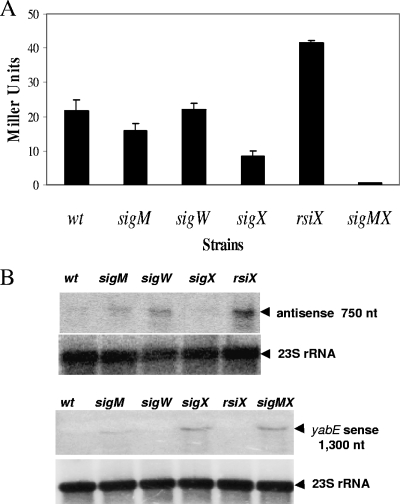

To determine which ECF σ factors regulate PECF, we measured the expression of a PECF-lacZ fusion in strains with one or more ECF σ factor genes disrupted (Fig. 3A). PECF is dependent primarily on σX, and as expected, the activity in a strain lacking the anti-σX factor RsiX was elevated. Interestingly, the expression of this promoter was weakly reduced in a ΔsigM::kan mutant (8) but not in a ΔsigW::mls mutant (17). Mindful of the potential for regulatory overlap between ECF σ factors (3, 16, 22, 25, 30), we tested a sigM sigX double-mutant strain and found that the double deletion eliminated the expression of PECF. Thus, we conclude that PECF is transcribed by both the σX and σM forms of RNA polymerase.

FIG. 3.

(A) PECF-directed antisense expression is dependent on σX and σM. The β-galactosidase activity of the PECF-lacZ fusion was assayed in various ECF deletion strains indicated by the relevant gene. Cultures were grown in LB medium, and samples were taken when cells reached late log phase. Data are expressed as averages ± standard deviations of results for triplicate samples. wt, wild type. (B) Regulation of yabE by an antisense RNA. Total RNA (15-μg) samples prepared from late-log-phase cultures of various deletion strains after growth in LB medium were analyzed by Northern blotting. RNA was separated, blotted, and hybridized with [γ-32P]ATP-labeled strand-specific probes for the yabE and the antisense RNA transcripts (indicated with arrowheads). The level of 23S rRNA is shown underneath as a loading control (2 μg of RNA was loaded). nt, nucleotides.

Next, we performed Northern blot analysis to monitor the size and abundance of the PECF-directed transcript. Fifteen micrograms of total RNA was isolated from cells in late-logarithmic-phase growth and run on a 1% formaldehyde denaturing gel by using NorthernMax denaturing gel buffer and running buffer (Ambion). The RNA was transferred onto a Zeta-Probe blotting membrane (Bio-Rad). The Northern analysis confirmed that the ∼750-nucleotide antisense RNA was highly transcribed in the ΔrsiX background (Fig. 3B). In a parallel analysis, we found that yabE was expressed as a monocistronic transcript (∼1,300 nucleotides) whose abundance varied inversely with that of the PECF-directed antisense transcript (Fig. 3B). These results are consistent with the hypothesis that the antisense RNA prevents the accumulation of the yabE transcript, presumably by pairing with and facilitating the degradation of the sense transcript. Although we attempted to detect YabE (using a C-terminal FLAG epitope tag), we were unable to detect the protein either in cells or in the secreted protein fraction (data not shown).

B. subtilis contains four genes encoding Rpf/Sps family proteins: yabE, yocH, yuiC, and yorM (31). YocH is an autolysin under the control of the essential YycFG two-component system (15). Our strains do not contain yorM, which is located within the SPβ prophage. In order to determine the physiological role of yabE, we constructed yabE, yocH, and yuiC single-deletion mutants, as well as a triple mutant, by using long flanking homology PCR as described previously (23). In the actinobacteria, Rpf is assayed by the ability to restore growth to washed cells inoculated at high dilutions or into nutrient-poor medium (20, 26). To test whether B. subtilis growth was affected by the loss of these rpf-like genes, stationary-phase cultures in LB medium were serially diluted from 10−1 to 10−7 in LB or minimal medium. In parallel, the same cells were washed several times with LB or minimal medium prior to dilution. Samples of 200 μl were incubated in a microtiter plate at 37°C with continuous shaking, and growth was monitored in a Bioscreen C analyzer (Laboratory Systems, Finland) using a 600-nm filter. Under these conditions, there were no significant differences between the wild type and any of the deletion strains, nor did we detect substantial differences in sporulation efficiency or stationary-phase survival (data not shown). Similar results in a different B. subtilis strain background have been observed previously (M. Young, personal communication). These results indicate that the genes are dispensable under these conditions. Further studies will be required to define the roles of the proteins in cell wall turnover, growth, and/or long-term survival. One hint may be provided by the observation that both yabE and yocH are upregulated during growth under high-salt conditions (34). Both the σX and σM regulons are activated by antibiotics that inhibit cell wall synthesis (4, 8, 23). Thus, antisense regulation of YabE is consistent with the notion that the downregulation of cell wall lytic enzymes is adaptive when cell wall synthesis is impaired. Indeed, yocH is positively regulated by the YycFG two-component system, which simultaneously downregulates IseA (YoeB), an inhibitor of autolysins (33, 39).

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that two ECF σ factors, σX and σM, control the expression of an antisense RNA for yabE. The expression of this RNA is correlated with decreased accumulation of the yabE sense transcript, presumably due to the degradation of the resulting duplex RNA. The coregulation of genes involved in antibiotic resistance (22) and of the expression of teichoic acid synthesis genes and cell division functions in B. subtilis W23 (25) by σX and σM has been observed previously. The discovery of this ECF σ factor-regulated antisense RNA, together with the recent finding of σM-dependent promoter elements within genes (8), suggests that current assignments of the regulons for ECF σ factors are likely incomplete. It can be anticipated that future studies, using chromatin immunoprecipitation-microarray analysis and powerful sequencing-based transcriptomics approaches, will facilitate a more complete inventory of ECF σ factor-dependent transcription.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mike Young for helpful discussions of the Rpf/Sps family proteins and for sharing unpublished results.

This work was supported by a grant from the NIH (GM-047446).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 December 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnaud, M., A. Chastanet, and M. Debarbouille. 2004. New vector for efficient allelic replacement in naturally nontransformable, low-GC-content, gram-positive bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 706887-6891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao, M., P. A. Kobel, M. M. Morshedi, M. F. Wu, C. Paddon, and J. D. Helmann. 2002. Defining the Bacillus subtilis σW regulon: a comparative analysis of promoter consensus search, run-off transcription/macroarray analysis (ROMA), and transcriptional profiling approaches. J. Mol. Biol. 316443-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao, M., C. M. Moore, and J. D. Helmann. 2005. Bacillus subtilis paraquat resistance is directed by σM, an extracytoplasmic function sigma factor, and is conferred by YqjL and BcrC. J. Bacteriol. 1872948-2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao, M., T. Wang, R. Ye, and J. D. Helmann. 2002. Antibiotics that inhibit cell wall biosynthesis induce expression of the Bacillus subtilis σW and σM regulons. Mol. Microbiol. 451267-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen-Gonsaud, M., P. Barthe, C. Bagneris, B. Henderson, J. Ward, C. Roumestand, and N. H. Keep. 2005. The structure of a resuscitation-promoting factor domain from Mycobacterium tuberculosis shows homology to lysozymes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12270-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Condon, C., D. Brechemier-Baey, B. Beltchev, M. Grunberg-Manago, and H. Putzer. 2001. Identification of the gene encoding the 5S ribosomal RNA maturase in Bacillus subtilis: mature 5S rRNA is dispensable for ribosome function. RNA 7242-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Downing, K. J., V. V. Mischenko, M. O. Shleeva, D. I. Young, M. Young, A. S. Kaprelyants, A. S. Apt, and V. Mizrahi. 2005. Mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis lacking three of the five rpf-like genes are defective for growth in vivo and for resuscitation in vitro. Infect. Immun. 733038-3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eiamphungporn, W., and J. D. Helmann. 2008. The Bacillus subtilis σM regulon and its contribution to cell envelope stress responses. Mol. Microbiol. 67830-848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerout-Fleury, A. M., N. Frandsen, and P. Stragier. 1996. Plasmids for ectopic integration in Bacillus subtilis. Gene 18057-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartmann, M., A. Barsch, K. Niehaus, A. Puhler, A. Tauch, and J. Kalinowski. 2004. The glycosylated cell surface protein Rpf2, containing a resuscitation-promoting factor motif, is involved in intercellular communication of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Arch. Microbiol. 182299-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helmann, J. D. 1995. Compilation and analysis of Bacillus subtilis σA-dependent promoter sequences: evidence for extended contact between RNA polymerase and upstream promoter DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 232351-2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helmann, J. D. 2002. The extracytoplasmic function (ECF) σ factors. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 4647-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hett, E. C., M. C. Chao, L. L. Deng, and E. J. Rubin. 2008. A mycobacterial enzyme essential for cell division synergizes with resuscitation-promoting factor. PLoS Pathog. 4e1000001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hett, E. C., M. C. Chao, A. J. Steyn, S. M. Fortune, L. L. Deng, and E. J. Rubin. 2007. A partner for the resuscitation-promoting factors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 66658-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howell, A., S. Dubrac, K. K. Andersen, D. Noone, J. Fert, T. Msadek, and K. Devine. 2003. Genes controlled by the essential YycG/YycF two-component system of Bacillus subtilis revealed through a novel hybrid regulator approach. Mol. Microbiol. 491639-1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang, X., K. L. Fredrick, and J. D. Helmann. 1998. Promoter recognition by Bacillus subtilis σW: autoregulation and partial overlap with the σX regulon. J. Bacteriol. 1803765-3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang, X., A. Gaballa, M. Cao, and J. D. Helmann. 1999. Identification of target promoters for the Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function σ factor, σW. Mol. Microbiol. 31361-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang, X., and J. D. Helmann. 1998. Identification of target promoters for the Bacillus subtilis σX factor using a consensus-directed search. J. Mol. Biol. 279165-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kana, B. D., B. G. Gordhan, K. J. Downing, N. Sung, G. Vostroktunova, E. E. Machowski, L. Tsenova, M. Young, A. Kaprelyants, G. Kaplan, and V. Mizrahi. 2008. The resuscitation-promoting factors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis are required for virulence and resuscitation from dormancy but are collectively dispensable for growth in vitro. Mol. Microbiol. 67672-684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keep, N. H., J. M. Ward, M. Cohen-Gonsaud, and B. Henderson. 2006. Wake up! Peptidoglycan lysis and bacterial non-growth states. Trends Microbiol. 14271-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lane, W. J., and S. A. Darst. 2006. The structural basis for promoter −35 element recognition by the group IV σ factors. PLoS Biol. 4e269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mascher, T., A. B. Hachmann, and J. D. Helmann. 2007. Regulatory overlap and functional redundancy among Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function σ factors. J. Bacteriol. 1896919-6927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mascher, T., N. G. Margulis, T. Wang, R. W. Ye, and J. D. Helmann. 2003. Cell wall stress responses in Bacillus subtilis: the regulatory network of the bacitracin stimulon. Mol. Microbiol. 501591-1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics, p. 352-355. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 25.Minnig, K., J. L. Barblan, S. Kehl, S. B. Moller, and C. Mauel. 2003. In Bacillus subtilis W23, the duet σXσM, two σ factors of the extracytoplasmic function subfamily, are required for septum and wall synthesis under batch culture conditions. Mol. Microbiol. 491435-1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukamolova, G. V., A. S. Kaprelyants, D. I. Young, M. Young, and D. B. Kell. 1998. A bacterial cytokine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 958916-8921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mukamolova, G. V., A. G. Murzin, E. G. Salina, G. R. Demina, D. B. Kell, A. S. Kaprelyants, and M. Young. 2006. Muralytic activity of Micrococcus luteus Rpf and its relationship to physiological activity in promoting bacterial growth and resuscitation. Mol. Microbiol. 5984-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mukamolova, G. V., O. A. Turapov, K. Kazarian, M. Telkov, A. S. Kaprelyants, D. B. Kell, and M. Young. 2002. The rpf gene of Micrococcus luteus encodes an essential secreted growth factor. Mol. Microbiol. 46611-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukamolova, G. V., O. A. Turapov, D. I. Young, A. S. Kaprelyants, D. B. Kell, and M. Young. 2002. A family of autocrine growth factors in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 46623-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiu, J., and J. D. Helmann. 2001. The −10 region is a key promoter specificity determinant for the Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic-function σ factors σX and σW. J. Bacteriol. 1831921-1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ravagnani, A., C. L. Finan, and M. Young. 2005. A novel firmicute protein family related to the actinobacterial resuscitation-promoting factors by non-orthologous domain displacement. BMC Genomics 639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russell-Goldman, E., J. Xu, X. Wang, J. Chan, and J. M. Tufariello. 2008. A Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rpf double-knockout strain exhibits profound defects in reactivation from chronic tuberculosis and innate immunity phenotypes. Infect. Immun. 764269-4281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salzberg, L. I., and J. D. Helmann. 2007. An antibiotic-inducible cell wall-associated protein that protects Bacillus subtilis from autolysis. J. Bacteriol. 1894671-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steil, L., T. Hoffmann, I. Budde, U. Volker, and E. Bremer. 2003. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling analysis of adaptation of Bacillus subtilis to high salinity. J. Bacteriol. 1856358-6370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Telkov, M. V., G. R. Demina, S. A. Voloshin, E. G. Salina, T. V. Dudik, T. N. Stekhanova, G. V. Mukamolova, K. A. Kazaryan, A. V. Goncharenko, M. Young, and A. S. Kaprelyants. 2006. Proteins of the Rpf (resuscitation promoting factor) family are peptidoglycan hydrolases. Biochemistry (Moscow) 71414-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tufariello, J. M., K. Mi, J. Xu, Y. C. Manabe, A. K. Kesavan, J. Drumm, K. Tanaka, W. R. Jacobs, Jr., and J. Chan. 2006. Deletion of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis resuscitation-promoting factor Rv1009 gene results in delayed reactivation from chronic tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 742985-2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Straaten, K. E., B. W. Dijkstra, W. Vollmer, and A. M. Thunnissen. 2005. Crystal structure of MltA from Escherichia coli reveals a unique lytic transglycosylase fold. J. Mol. Biol. 3521068-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wecke, T., B. Veith, A. Ehrenreich, and T. Mascher. 2006. Cell envelope stress response in Bacillus licheniformis: integrating comparative genomics, transcriptional profiling, and regulon mining to decipher a complex regulatory network. J. Bacteriol. 1887500-7511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamamoto, H., M. Hashimoto, Y. Higashitsuji, H. Harada, N. Hariyama, L. Takahashi, T. Iwashita, S. Ooiwa, and J. Sekiguchi. 2008. Post-translational control of vegetative cell separation enzymes through a direct interaction with specific inhibitor IseA in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 70168-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zahler, S. A., R. Z. Korman, R. Rosenthal, and H. E. Hemphill. 1977. Bacillus subtilis bacteriophage SPβ: localization of the prophage attachment site, and specialized transduction. J. Bacteriol. 129556-558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]