Abstract

Our previous report showed the existence of microaerophilic Bifidobacterium species that can grow well under aerobic conditions rather than anoxic conditions in a liquid shaking culture. The difference in the aerobic growth properties between the O2-sensitive and microaerophilic species is due to the existence of a system to produce H2O2 in the growth medium. In this study, we purified and characterized the NADH oxidase that is considered to be a key enzyme in the production of H2O2. Bifidobacterium bifidum, an O2-sensitive bacterium and the type species of the genus Bifidobacterium, possessed one dominant active fraction of NADH oxidase and a minor active fraction of NAD(P)H oxidase activity detected in the first step of column chromatography for purification of the enzyme. The dominant active fraction was further purified and determined from its N-terminal sequence to be a homologue of b-type dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHOD), composed of PyrK (31 kDa) and PyrDb (34 kDa) subunits. The genes that encode PyrK and PryDb are tandemly located within an operon structure. The purified enzyme was found to be a heterotetramer showing the typical spectrum of a flavoprotein, and flavin mononucleotide and flavin adenine dinucleotide were identified as cofactors. The purified enzyme was characterized as the enzyme that catalyzes the DHOD reaction and also catalyzes a H2O2-forming NADH oxidase reaction in the presence of O2. The kinetic parameters suggested that the enzyme could be involved in H2O2 production in highly aerated environments.

Obligatory anaerobes such as Clostridium, sulfate-reducing bacteria, and Bacteroides species are known as anaerobes that show inhibited growth in the presence of oxygen; however, recent research has revealed that these anaerobes show various types of oxic growth, depending on the concentration of oxygen, over a range of 0.1 to 21% in association with the expression of oxygen metabolic enzymes (5, 8, 11, 12, 17-20, 26, 30, 38, 44, 48).

The genus Bifidobacterium contains probiotic species beneficial for the human intestine, but its sensitivity to O2 decreases its viability during the stages of food processing, storage, and incorporation into the human intestine (42, 45). Several approaches have been taken to determine the mechanisms of bifidobacterial aerobic growth inhibition (10, 21, 43). de Vries and Stouthamer proposed that O2-sensitive Bifidobacterium species produce H2O2 through the reaction of NADH oxidase detected in cell extracts (10); however, the molecular-level mechanisms of growth inhibition and H2O2 production have since remained essentially unknown.

In our previous study, we classified Bifidobacterium species into oxygen-sensitive species and microaerophilic species (21, 22). Many species belonging to the genus Bifidobacterium show oxygen-sensitive growth profiles under highly aerated conditions (21). These species grow in liquid medium when shaken under 5% O2 conditions, but growth is inhibited under 10 to 20% O2 conditions with an accumulation of H2O2, and growth is recovered when they are cultured in the presence of exogenously added catalase. Microaerophilic species such as B. boum and B. thermophilum grow well even under 20% O2 and do not accumulate H2O2 (21). These observations indicate that the production of H2O2 is the primary reason for bifidobacterial aerobic growth inhibition. Two main theories, the existence of H2O2 production systems and the lack of H2O2 detoxification systems, have been proposed for O2-sensitive Bifidobacterium species. As to systems to reduce O2 to H2O2, only NADH oxidase activities have been detected in the cell extracts of all tested bifidobacterial species (21). Although the total NADH-dependent oxidase activities in cell extracts are similar among species, the type of NADH oxidase activity differs between O2-sensitive and microaerophilic species: O2-sensitive species show H2O2-forming activity, and microaerophilic species show H2O-forming activity (21).

In this study, we purified and characterized a protein that exhibits H2O2-forming NADH oxidase activity from an O2-sensitive species, Bifidobacterium bifidum, the type species of the genus Bifidobacterium (15). B. bifidum possesses a dominant active fraction and a minor active fraction of NADH oxidase activity during purification. The purified protein from the major active fraction is a homologue of b-type dihydroorotate (DHO) dehydrogenase (DHOD; EC 1.3.1.14, EC 1.3.3.1, EC 1.3.99.11), the enzyme that catalyzes the oxidation of DHO to orotate in pyrimidine biosynthesis (35). Previously, many enzymes that function as NADH oxidase in vivo have been purified and characterized; however, to our knowledge, no DHOD has been purified as a main source of NADH oxidase activity in cell extracts. The kinetics of the purified enzyme was studied to determine the functionality of its DHOD reaction, as well as its H2O2-forming NADH oxidase reaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strain and growth conditions.

B. bifidum JCM1255T (= ATCC 29521, DSM20456, IFO14252) was used in this study. B. bifidum was grown anaerobically at 37°C in a modified MRS medium (pH 6.7) described previously (21). Microaerobically grown B. bifidum cells (cultured statically but stirred with a magnetic stirrer in 3 liters of medium in a 5-liter flask with a cotton plug) were harvested for enzyme purification.

Chemicals.

All chemicals were of analytical grade. Orotic acid, DHO, ß-NADH, ß-NAD+, fumarate, cytochrome c, 2,3-dimethoxy-5-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone (Q0), ubiquinone 10 (Q10), menadione, and 2,6-dichlorobenzenoneindophenol (DCIP) were from Sigma. Water was prepared with an Ellix-10 Milli-Q ultrapure water system (Millipore, Tokyo, Japan).

Enzyme purification.

NADH oxidase activity was assayed spectrophotometrically in 1 ml of air-saturated 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.5) containing 0.15 mM NADH at 37°C. The reaction was started by the addition of enzyme solution, and the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm (ɛ340 = 6,220 M−1 cm−1) was monitored with a spectrophotometer (HITACHI U-3300; Hitachi, Japan). One unit of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzes the oxidation of 1 μmol NADH per min.

Microaerobically grown B. bifidum cells (80 g) were suspended in 240 ml of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, containing 0.1 mM DTT, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 5 mM EDTA, and then the cells were disrupted by treatment with a French pressure cell at 140 MPa. All purification procedures were carried out at 4°C or on ice. Cell-free extracts (CFE) were obtained by removing cell debris by centrifugation at 39,000 × g for 15 min. The cytoplasmic solution obtained by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 2 h was treated with 10% streptomycin sulfate (dissolved in 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.1) to remove nucleic acids. After centrifugation at 39,000 × g for 15 min, the supernatant was fractionated by the stepwise addition of solid ammonium sulfate (20%). The supernatant obtained after centrifugation at 30,000 × g was dissolved in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, containing 1 M ammonium sulfate, 5 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM PMSF, and 0.1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). After centrifugation at 39.000 × g for 15 min, the supernatant was subjected to Butyl-Toyopearl 650S (Tosoh, Tokyo, Japan) column chromatography. The enzyme was eluted with a linear gradient of 800 to 0 mM ammonium sulfate dissolved in the same buffer. After Butyl-Toyopearl chromatography, two main fractions of NADH oxidase activity were obtained. The major active fractions were collected and further purified. The solution after Butyl-Toyopearl chromatography was dialyzed against 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, containing 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM PMSF, 0.1 mM DTT, and 25 μM flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) for 6 h, and this procedure was repeated three times with freshly prepared buffer each time. The enzyme solution was then subjected to DEAE-Sephacel (Amersham-Pharmacia, Japan) column chromatography. The column was sequentially washed with the same buffer containing 0 and 150 mM NaCl and eluted with buffer containing 220 mM NaCl. The active fractions were pooled and dialyzed for 12 h against 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, containing 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM DTT, and 25 μM FAD and subjected to hydroxyapatite (Wako, Japan) column chromatography. After the enzyme solution was applied to the hydroxyapatite column, the protein was sequentially washed with 10 and 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, and eluted with 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5. The active fractions were collected and concentrated with Amicon Ultra (30,000-Da cutoff; Millipore, Cork, Ireland). The concentrated enzyme was subjected to POLOS HQ/H (PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, MA) column chromatography. The column was sequentially washed with 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, containing 0 M NaCl (stepwise) and 0 mM to 100 mM NaCl (linear gradient) and then eluted with a linear gradient of 100 to 250 mM NaCl. The active fraction was collected and concentrated with Amicon Ultra. After this chromatography, the enzyme purity in the active fractions was checked by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) with Coomassie brilliant blue staining or silver staining. With this enzyme concentrator, the basal buffer of the enzyme solution was changed to 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, by diluting the concentrated enzyme solution 100-fold with the new buffer, concentrating it to the original volume, and then repeating the dilution and concentration steps; the second concentrated enzyme solution was subjected to an enzyme assay. The protein concentration was determined by the dye-binding assay (7).

Native molecular weight, N-terminal amino acid sequence, and protein concentration analyses.

The purified enzyme was subjected to gel filtration column chromatography (HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200 pg; Amersham Pharmacia, Japan) to determine the native molecular weight. The molecular mass was calibrated with the following standard proteins (Amersham Pharmacia, Japan): bovine thyroglobulin (669 kDa), ferritin (440 kDa), catalase (232 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), bovine serum albumin (67 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), chymotrypsinogen (25 kDa), and RNase (13.7 kDa).

The purified enzyme was subjected to SDS-PAGE and electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Nippon Genetics, Tokyo, Japan). The N-terminal amino acid sequence was determined by the Edman degradation method with the peptide sequencer described previously (18). The UV-Vis absorption spectrum was recorded on a Hitachi U3300 spectrophotometer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) with a quartz cuvette with a 1-cm path length. The molar absorption coefficient of the purified protein was determined by averaging the quantities of alanine, proline, valine, threonine, and tyrosine from the quantitative amino acid analysis performed at the Toray Research Center, Inc. (Kamakura, Japan), with a Hitachi model L-8500 amino acid analyzer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

The flavin content was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography analysis according to a previously described method with a Capcell Pack C18 column (4.6 by 150 mm; Shiseido Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with 5 mM ammonium acetate-methanol buffer as the mobile phase (18). Flavin was identified with riboflavin, FAD, and flavin mononucleotide (FMN) as standards. Data represent the means ± standard deviations of three independent measurements.

Enzyme properties.

The pH optimum of the purified enzyme was determined in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer in a pH range of 5.0 to 8.0 at 37°C, which is the optimum growth temperature for B. bifidum. The temperature optimum of the purified enzyme was determined in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, over a range of 25 to 60°C. Enzyme inhibitors were added to the enzyme solution at a final concentration of 1 mM, and the solutions were incubated for 5 min at 37°C; reactions were started by the addition of an enzyme-inhibitor mixture (18).

H2O2 production by the B. bifidum NADH oxidase reaction was detected while monitoring O2 production with an oxygen electrode by adding catalase to the reaction vessel (18, 21). Catalase catalyzes the stoichiometric conversion of 1 mol H2O2 to 1 mol H2O and 0.5 mol O2. The H2O2-forming-type NADH oxidase produces 50% O2 after the addition of catalase to the total amount of O2 consumed by the NADH oxidase reaction. H2O-forming-type NADH oxidase produces no O2 after the addition of catalase.

The substrate specificity of the purified enzyme was assayed spectrophotometrically at 37°C with 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, containing 5 μM EDTA. Electron acceptors for the enzyme were investigated by adding various substrates (final concentration, 50 μM) to the anaerobic cuvette together with the enzyme solution. For all acceptors except O2, the reactions were carried out under anoxic conditions by purging the anaerobic glass cuvette containing the reaction buffer with O2-free argon gas. NADH (final concentration, 150 μM) or DHO (final concentration, 150 μM) was used as an electron donor for the enzyme. For the reactions of NADH:acceptor oxidoreductase and DHO:acceptor oxidoreductase, 1 U of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzes the reduction of 1 μmol of NADH (ɛ340 = 6,220 M−1 cm−1) or the production of 1 μmol of orotic acid (ɛ278 = 7,700 M−1 cm−1) per min, respectively. For the assays of DCIP and cytochrome c, 1 U of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzes the reduction of 1 μmol of DCIP (ɛ600 = 22,000 M−1 cm−1) or cytochrome c (ɛ550 = 18,500 M−1 cm−1) per min, respectively. The values for enzyme inhibition (percent), relative activities (percent), and the specific activities (U/mg protein) are the average of three independent measurements that varied by less than 5%.

Steady-state kinetics.

Kinetic parameters of the purified enzyme were determined by the following experiment. Initial rates were determined from linear plots of product formation (or substrate disappearance). The NADH oxidase assay, in which the oxidation of NADH is coupled to the reduction of O2, was performed with an oxygen electrode to monitor the decrease in O2 after the addition of NADH and enzyme solution. The DHOD assay, in which the oxidation of DHO is coupled to the reduction of NAD+, was performed with a spectrophotometer to monitor the reduction of NAD+ at 340 nm (ɛ340 = 6,220 M−1 cm−1) or the oxidation of DHO at 278 nm (ɛ278 = 7,700 M−1 cm−1). The NADH:orotate oxidoreductase assay, in which the oxidation of NADH is coupled to the reduction of orotate, was performed with a spectrophotometer to monitor the oxidation of NADH at 340 nm or the reduction of orotate at 278 nm (ɛ278 = 7,700 M−1 cm−1). All reactions were carried out in anaerobic glass cuvettes by O2-free techniques. For the NADH oxidase assay, buffer solutions containing different concentrations of dissolved O2 were prepared by purging with N2-based gas containing different O2 concentrations; the final dissolved O2 concentrations in the reaction cuvette were checked with an O2 electrode prefitted to a cuvette with a rubber seal to prevent oxygen contamination from outside of the cuvette. The apparent Km, Vmax, and kcat values for NADH and O2 (NADH oxidase reaction), DHO and NAD+ (DHO:NAD+ oxidoreductase), and NADH and orotate (NADH:orotate oxidoreductase) were determined by varying the concentrations of both NADH (14.4, 18.5, 25.6, 45.3, and 123 μM) and O2 (expected concentrations of 62.5, 125, 262.5, 625 and 1,087.5 μM; data were plotted based on the actual concentrations at measurements), both DHO (10, 30, 60, and 120 μM) and NAD+ (20, 40, 80, 120, and 200 μM), or both NADH (14.4, 18.5, 25.6, and 45.3 μM) and orotate (10.9, 19.9, 53.6, and 105.5 μM), respectively, in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5. The Michaelis-Menten constants were determined by nonlinear regression analysis with Enzyme Kinetics Module 1.3 (Sigma Plot 11; SYSTAT Software, Chicago, IL). The values given are the means ± standard errors of two independent measurements, each performed in duplicate.

Genetic analysis.

The degenerated sense primer for the N-terminal sequence of B. bifidum PyrDb (5′-ATGGAYGCNGTNACNGAYAC, in which Y is C or T and N is A, T, G, or C) and the antisense primer from the conserved region of PyrDb among other Bifidobacterium species (5′-CCNCCNANDCCDATDATNGG, in which N is A, C, G, or T and D is G, A, or T) were used for the first PCR. B. bifidum genome DNA was extracted and used as the template. The PCR fragment obtained (0.8 kb) was cloned into the pT7Blue vector (Novagen, Tokyo, Japan) and sequenced. Sequence analysis indicated that the PCR product obtained encoded the N-terminal part of the target protein. The extended genome region was further amplified with PCR primers obtained from the nucleotide sequence of a 0.8-kb PCR fragment by the method of DNA walking PCR technology according to the manufacturer's manual (DNA Walking Speedup Premix Kit; Seegene, Seoul, South Korea) (14). Extended genome regions (upstream region of pyrDb and downstream region of pyrDb) were amplified by DNA walking PCR technology, and the PCR products were directly sequenced. PCR primers were synthesized from the 5′ region of the pyrDb upstream PCR fragment (CGCAGGACATGCGCGACGAC) and from the 3′ region of the pyrDb downstream PCR fragment (AGCCCGTCAGCGCCGGATAC). With these primers, a 2.7-kb genome region was amplified with the B. bifidum genome as the template and the PCR product was directly sequenced.

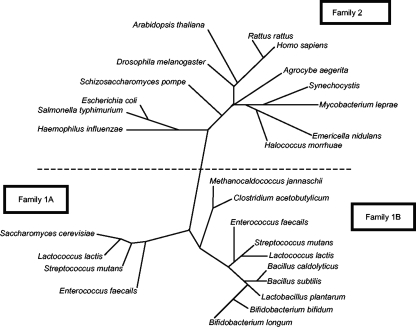

A multiple alignment of 22 currently known DHOD sequences reported by Björnberg et al. (6), together with our newly selected sequences of DHOD from Streptococcus mutans families 1A (NP_721028) and 1B (NP_721602), Clostridium acetobutylicum family 1B (NP_349257), Enterococcus (previously Streptococcus) faecalis family 1B (NP_815420), and Bifidobacterium longum family 1B (NP_695968), was made. A taxonomic analysis was performed with the ClustalW program (46) at DDBJ (http://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp). Phylogenetic trees were computed with ClustalW by the neighbor-joining method with Kimura's correction (bootstrap scores for 1,000 iterations). Trees were displayed with the TreeView program (36).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The 2.7-kb nucleotide sequence data reported here have been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank database under accession number AB374935.

RESULTS

Elution profiles of NADH oxidase activity at the first step of column chromatography.

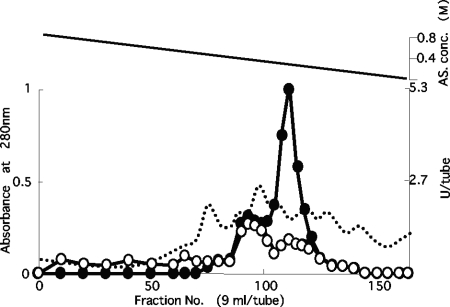

To characterize the enzyme that exhibits NADH oxidase activity in the CFE from O2-sensitive B. bifidum, we purified the enzyme. As the first step in the purification process, proteins were fractionated according to their hydrophobic properties (Fig. 1). In B. bifidum CFE, two elution peaks showing NADH oxidation activity were detected. These two elution peaks were differentially characterized using NADPH as an electron donor. The dominant active elution peak preferred NADH as the electron donor (Fig. 1). The minor peak showed almost the same oxidase activities with both NADH and NADPH. The peak fractions from both the major and minor elution peaks showed H2O2-forming-type NADH oxidase activity (approximately stoichiometric production of H2O2 was detected from the reduction of O2: e.g., 50 μl of eluate from a peak fraction of the major peak consumed 73.5 nmol O2/5 min/ml, and 37.5 nmol O2/ml was produced after catalase was added. A 50-μl volume of eluate from a peak fraction of the minor peak consumed 24.5 nmol O2/5 min/ml, and 10 nmol O2/ml was produced after catalase was added). No significant NAD(P)H oxidase activities were detected in either the unbound fraction or the washed fractions from the first column chromatography. Sometimes, H2O2-forming NADPH-specific oxidase activity was detected in fractions 60 to 70 (Fig. 1), which reached 10 to 15% of the total NAD(P)H oxidase activity.

FIG. 1.

Chromatographic elution profiles of B. bifidum NADH and NADPH oxidases. Cell extracts, after treatment with streptomycin sulfate and ammonium sulfate, were applied to a Butyl-Toyopearl column equilibrated with 1 M ammonium sulfate dissolved in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. After loading of the sample, bound proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of 800 to 0 mM ammonium sulfate (AS) dissolved in the same buffer. Dashed line, protein absorption at 280 nm; black circles, NADH oxidase activity; white circles, NADPH oxidase activity; solid line, ammonium sulfate concentration (conc.).

Purification of NADH oxidase from B. bifidum.

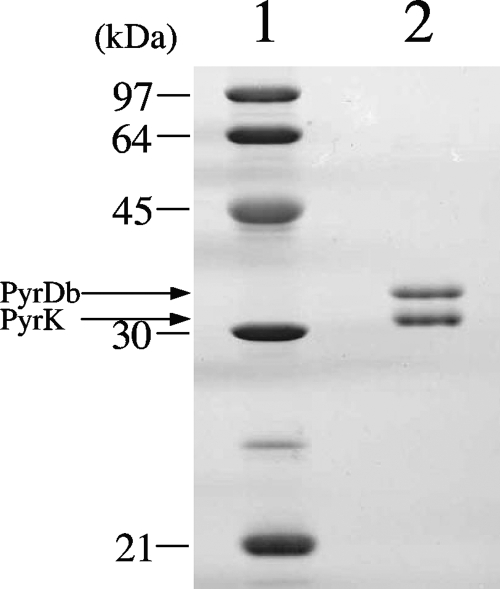

Both the major and minor active fractions were collected and purified through further column chromatography steps. In this report, the purification of the NADH oxidase from the major active fraction is described. The activity of the major active fraction exhibited 75 to 80% of the total NADH oxidase activity (calculated from the peak area of Butyl-Toyopearl column chromatography, n = 5; assayed in air-saturated 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5). The major active fraction after Butyl-Toyopearl column chromatography was collected, and the enzyme was further purified by several column chromatography steps (Table 1). For each step, only one predominant active elution peak was detected. After the final step of gel filtration chromatography, the purified fractions appeared as two bands (34 and 31 kDa) on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2).

TABLE 1.

Purification of NADH oxidase from microaerobically grown B. bifidum

| Purification step | Total activity (U) | Total protein (mg)a | Sp act (U/mg protein)a | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude extract | 256 | 6,050 | 0.042 | 100 |

| Ammonium sulfate | 221 | 2,800 | 0.078 | 86 |

| Butyl-Toyopearl 650S | 90 | 393 | 0.23 | 35 |

| 1st dialysis | 108 | 369 | 0.29 | 42 |

| DEAE-Sephacel | 70 | 92 | 0.76 | 27 |

| 2nd dialysis | 64 | 75 | 0.86 | 25 |

| Hydroxyapatite | 36 | 22 | 1.69 | 14 |

| POROS HQ/H | 17.6 | 0.66 | 26.7 | 6.9 |

Protein concentration was determined by the dye-binding assay (7).

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE of purified B. bifidum DHOD. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. The protein standards (lane 1) and purified protein (lane 2) are indicated, along with the corresponding molecular masses (indicated on the left in kilodaltons). Arrows indicate the corresponding subunit name deduced from the N-terminal amino acid sequences.

Determination of N-terminal amino acid sequence and gene cloning.

The N-terminal sequence of the purified enzyme was determined. The upper 34-kDa band (MDAVTDTNVYEPHQWKHSTI) showed homology to the bacterial DHOD large subunit, PyrDb. The 31-kDa band (PAATFTPVDDVVSQATSAG) showed homology to the bacterial DHOD small subunit, PyrK. Information on the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the purified DHOD and the predicted internal peptide sequence derived from a highly conserved region in the catalytic domain of the DHOD homologue from B. longum and B. adolescentis (e.g., IPIIGLGGI, positions 257 to 265 of the B. longum DHOD protein sequence, accession number NP_695968) was used to design degenerate primers, which were used for PCR amplification of the B. bifidum genome. A 0.8-kb PCR fragment was obtained that encoded an amino acid sequence perfectly matching the N-terminal sequence of the purified enzyme. To determine the genomic structure of the PyrK-PyrDb coding region, a nested-PCR-based genome-walking technique (14) was performed. A 2.7-kb portion of the genome region was amplified, and the PCR product was directly sequenced.

Sequence homology.

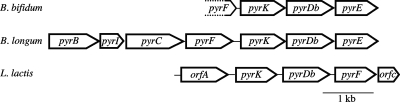

The nucleotide sequence of a 2.7-kb genome region was determined and was found to contain three open reading frames named pyrK, pyrDb, and pyrE (Fig. 3). Upstream of pyrK, a possible end codon for pyrF was found (10 of the residues [underlined] in the C-terminal 13-amino-acid [aa] sequence of B. bifidum PyrF [QDMRDDLRVNVYR] were identical to those in the C-terminal 13-aa sequence of B. longum PyrF [LDMRDNLRVAVYR, accession number NP_695970]). The pyrK gene encodes a protein of 276 aa. PyrK from B. bifidum showed 28.7% identity (64.8% similarity) to structurally and functionally well-characterized Lactococcus lactis protein PyrK (accession number NP_267503) (2, 39, 40). The cysteine ligands of the iron-sulfur cluster that is conserved among bacterial PyrK proteins (40) are all conserved in B. bifidum PyrK (Cys241, Cys246, Cys249, and Cys261). The pyrDb gene encodes a protein of 315 aa. PyrDb from B. bifidum also showed 42.1% identity (75.9% similarity) to L. lactis PyrDb (accession number NP_267502) (2, 39, 40). Both the bacterial PyrK and PyrDb proteins are known to act as DHOD via a heterotetramer structure containing two PyrK and two PyrDb subunits (4, 27, 32). The B. bifidum pyrE gene encodes a protein of 232 aa. B. bifidum PyrE showed 43.7% identity (82.2% similarity) to Escherichia coli PyrE (accession number P0A7E3) (37). PyrE catalyzes the orotate phosphoribosyltransferase reaction, which is the fifth step in the pyrimidine biosynthetic pathway (14, 35). In the genome databases of B. longum (accession number NC_004307) and B. adolescentis (accession number NC_008618), the pyrDb and pyrK genes are both located in a 6.5-kb operon structure comprising pyrB-pyrI-pyrC-pyrF-pyrK-pyrDb-pyrE (Fig. 3). The order of the pyrFKDbE genes identified in B. bifidum is the same as that in B. longum and B. adolescentis. The order of the pyrK and pyrDb genes is well conserved in the genomes of bacterial species such as L. lactis (pyrKDbF) (2), E. faecalis (pyrKDbFE) (genome accession no. NC_004668), Bacillus subtilis (pyrKDbFE) (16), and C. acetobutylicum (pyrFKDb) (34). Both the pyrE and pyrF genes are conserved in the bacterial genome, but their order and localization in the genome depend on the species.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of pyr gene clusters from B. bifidum, B. longum, and L. lactis (2). Open arrows indicate the sizes and transcriptional directions of the genes. In B. bifidum, a 2.7-kb genome region was determined. Upstream of pyrK, a possible end codon of pyrF was found. In B. longum, a 6.5-kb genome region was found to encode a pyr gene cluster (pyrB to pyrE) by the genome project. In L. lactis, a 3.2-kb genome region encodes a pyr gene cluster (pyrK to orfC). An orfA gene has been reported to be transcribed independently by the pyrK operon (2).

Molecular masses, subunit composition, and determination of flavin cofactors of B. bifidum DHOD.

Gel filtration of purified native DHOD yielded a single peak whose elution volume corresponded to an estimated molecular mass of 130 kDa. This demonstrates that the enzyme is a tetramer composed of two PyrDb subunits and two PyrK subunits.

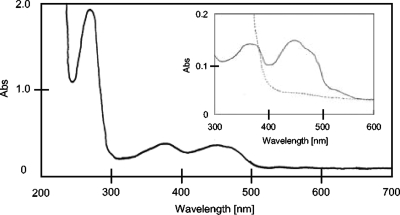

The purified enzyme (brownish yellow) showed a typical flavoprotein spectrum with absorption maxima at 280, 373, and 450 nm (A280/A373 = 4.0, A280/A450 = 4.0) with a shoulder above 500 nm (Fig. 4). The molar extinction coefficient at 450 nm was determined to be ɛ450 = 66.76 M−1 cm−1 (heterotetramer). The flavin content was calculated as 1.78 ± 0.08 mol FAD and 2.06 ± 0.08 mol FMN/mol protein (heterotetramer). The findings about the spectrum features and structural properties of B. bifidum DHOD are commonly conserved in other b-type DHODs of gram-positive bacteria, including Clostridium oroticum (previously classified as “Zymobacterium oroticum”) (4, 28), L. lactis (32), E. faecalis (27), and B. subtilis (16).

FIG. 4.

Absorption spectrum of DHOD. The absorption (Abs) spectrum of the purified DHOD enzyme in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, at 25°C was determined. The inset shows the enzyme absorption spectrum before (black line) and after (dashed line) anaerobic reduction with 0.15 mM NADH.

Catalytic properties.

The pH optimum for the NADH oxidase reaction was determined to be pH 6.5 or 7.5. The relative NADH oxidase activity at pH 7.0 corresponds to approximately 95% of the activity at pH 6.5 or 7.5. The purified enzyme showed thermostable characteristics by which the activity increased as the reaction temperature was increased up to 60°C at pH 6.5. To determine the kinetic properties, the following enzyme activities were assayed at 37°C (growth temperature) or at 25°C (for steady-state kinetics).

When DHO was used as the substrate with NAD+ as the electron acceptor under anaerobic conditions (corresponds to the DHOD reaction), the pH optimum was determined to be 7.5. The following kinetic data were obtained at pH 6.5, which is the pH optimum for the NADH oxidase reaction. This was done for two reasons, first to obtain a set of kinetic data for all activities under the same conditions and to compare the kinetic data to those found in previous reports (28) and second because the pH optimum for the growth of Bifidobacterium species is under acidic conditions below pH 7.0. The activity of the DHOD reaction at pH 6.5 corresponds to 70% of the activity at the optimum pH of 7.5.

The effects of inhibitors and metal ions on the enzyme reactions were investigated (Table 2). The NADH oxidase reaction and the DHOD reaction were both strongly inhibited by HgCl2 and p-chloromercuribenzoate, which are inhibitors of enzymes containing sulfhydryl groups in their catalytic centers (47). Quinine and quinacrine, known inhibitors of flavoproteins (3), did not produce any significant inhibition. Interestingly, cyanide treatment specifically inhibited the DHOD reaction completely but had no effect on the NADH oxidase reaction.

TABLE 2.

Effects of inhibitors on the NADH oxidase and DHO:NAD+ oxidoreductase activities of B. bifidum DHOD

| Inhibitor | % Inhibition

|

|

|---|---|---|

| NADH oxidase | DHO:NAD+ oxidoreductase | |

| None | 0 | 0 |

| HgCl2 | 100 | 100 |

| PCMBa | 100 | 100 |

| KCN | 9.3 | 100 |

| Quinine | 0 | 0 |

| Quinacrine | 0 | 19.2 |

PCMB, p-chloromercuribenzoate.

The purified enzyme showed a preference for NADH as the electron donor rather than NADPH (the specific activities of the NADH and NADPH oxidases were 29.1 and 2.5 U/mg of protein, respectively, assayed in air-saturated 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, at 37°C). In the NADH and NADPH oxidase reactions, 1 mol of H2O2 was produced per mol of reduced O2 (e.g., 1.2 μg of enzyme consumed 37.3 nmol of O2/5 min/ml, and 19.2 nmol of O2/ml was produced after catalase was added). This result indicates that the purified enzyme reduces O2 by 2 reducing equivalents to H2O2.

The enzyme catalyzed electron transfers from NADH and DHO to O2, orotate, Q0, cytochrome c, dichloroindophenol (an artificial electron acceptor used for NADH dehydrogenase), and menadione (Table 3). B. bifidum DHOD shows low oxidase activity when DHO is used as an electron donor. Although B. bifidum DHOD efficiently transfers electrons to substrates for the O2 respiratory chain such as quinones and cytochrome c, Bifidobacterium species lack a respiratory chain and do not have the ability to synthesize these compounds (29). These results proposed that the natural electron acceptor of B. bifidum DHOD under anaerobic growth conditions is NAD+, which is also suggested to be a natural electron acceptor for DHOD from other gram-positive bacteria lacking an O2 respiration chain such as L. lactis (32) and C. oroticum (4). Fumarate, which is the preferred electron acceptor for A-type DHOD (1), was not used as a substrate.

TABLE 3.

Determination of electron acceptors in the NADH oxidase and DHO:NAD+ oxidoreductase reactions of B. bifidum DHOD

| Electron acceptor | Relative activity (%)a

|

|

|---|---|---|

| NADH:acceptor oxidoreductase | DHO:acceptor oxidoreductase | |

| O2 | 100 | 14 |

| DCIP | 410 | 88 |

| Menadione | 187 | 54 |

| Q0 | 118 | 51 |

| Q10b | NDc | ND |

| NAD+ | —d | 24 |

| Cytochrome c | 144 | 33 |

| Orotate | 142.5 | — |

| Fumarate | ND | ND |

Relative activity (percent) was calculated relative to the activity of NADH:oxygen oxidoreductase.

Q10 was dissolved in 100% ethanol, and 10 μl of the solution was added to the assay solution (final volume, 1 ml).

ND, not detected.

—, cannot be used as a substrate in this assay.

Steady-state analyses were extended to include the reaction of NADH oxidase, DHO:NAD+ oxidoreductase, and NADH:orotate oxidoreductase (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The kinetic properties of the purified enzyme are compared with those of L. lactis b-type DHOD (9) and C. oroticum b-type DHOD (28) in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Kinetic parameters of b-type DHOD

| Kinetic parameter |

b-type DHOD

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| B. bifiduma | L. lactisb | C. oroticumc | |

| NADH oxidase | |||

| Km for NADH (μM)d | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 5.6 ± 0.9 | 36 |

| Km for O2 (μM) | 779 ± 82 | —e | 540 |

| Vmax (O2 μmol/min/mg) | 80.6 ± 4.5 | — | — |

| kcat (O2, s−1) | 85.0 ± 4.8 | 11.7 ± 0.3 | 41.7 |

| DHO:NAD+ oxidoreductase | |||

| Km for DHO (μM) | 74.0 ± 3.1 | 90 ± 6 | 170 |

| Km for NAD+ (μM) | 36.8 ± 4.8 | 62 ± 4 | 360 |

| Vmax (DHO μmol/min/mg) | 7.0 ± 0.2 | — | — |

| kcat (DHO, s−1) | 7.4 ± 0.2 | 49.3 ± 0.8 | 14.7 |

| NADH:orotate oxidoreductase | |||

| Km for NADH (μM) | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 50 |

| Km for orotate (μM) | 30.0 ± 2.8 | 21.3 ± 2.2 | 1,800 |

| Vmax (orotate μmol/min/mg) | 67.9 ± 2.4 | — | — |

| kcat (orotate, s−1) | 71.6 ± 2.5 | 25.7 ± 0.4 | 36.7 |

Protein concentration was determined by using the molar extinction coefficient. The maximum turnover number, kcat, was calculated on the basis of moles of substrate oxidized or reduced per second per catalytic subunit (heterodimer).

From reference 9. Assayed at pH 8.0, near the pH optimum of the DHOD reaction. The maximum turnover number, kcat, was calculated on the basis of moles of substrate oxidized or reduced per second per catalytic subunit (heterodimer).

From reference 28. Assayed at pH 6.76, near the pH optimum of the NADH oxidase reaction. The maximum turnover number, kcat, was calculated on the basis of moles of substrate oxidized or reduced per second per enzyme-bound flavin.

Measured at atmospheric O2 concentration.

—, data not provided.

DISCUSSION

DHOD is known as the enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of DHO to orotate. This conversion is the fourth step, and the sole redox reaction that produces NADH, in the pyrimidine biosynthetic pathway. This enzyme was first purified from an obligatory anaerobe, C. oroticum, grown in enrichment culture on orotic acid medium (25). Since then, several approaches have been taken to determine the enzyme's properties. Sequence analyses have defined two families of DHOD, families 1 and 2 (6). The family 2 enzyme is membrane associated and distributed widely from bacteria to eukaryotes (23, 24, 31). Family 1 enzymes are soluble and cytosolic (31-33), and they are further divided into two subgroups, families 1A and 1B (6). Family 1A enzymes are homodimers of PyrDb containing FMN as the only prosthetic group. The family 1B enzyme is a heterotetramer comprising two PyrDb and two PyrK subunits containing FMN and FAD. Phylogenetic analysis of B. bifidum DHOD shows a close relationship to family 1B-type DHOD (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Evolutionary tree for DHOD. An evolutionary tree depicting the relationships among 27 different DHOD sequences is shown. DHOD sequences were classified into three major families, 1A, 1B, and 2 (6).

From the analyses of gene structure and kinetic properties, the purified enzyme is suggested to have a function in pyrimidine biosynthesis in B. bifidum under anaerobic growth conditions. Here we purified B. bifidum DHOD, which shows H2O2-forming NADH oxidase activity. Family 1B-type DHOD has been reported to use molecular oxygen as an electron acceptor when DHO is used as an electron donor (6, 16, 27); however, the reactivity of the enzyme with molecular oxygen when NADH is used as an electron donor has received little attention. The kinetic reaction properties of the enzyme with respect to the NADH oxidase reaction have been well investigated in C. oroticum DHOD (28). According to the kinetic data for C. oroticum DHOD, the Km for O2 is 540 μM, where the Km for NADH is 36 μM when assayed at pH 6.76, near the pH optimum of the NADH oxidase reaction (Table 4). The kinetic parameters of the reactivity with oxygen in the NADH oxidase reaction resemble those of B. bifidum DHOD. The kinetic parameters of L. lactis b-type DHOD are provided at pH 8.0, the pH optimum of the DHOD reaction. The kinetic properties of B. bifidum DHOD with respect to the DHOD reaction are estimated to resemble those of L. lactis b-type DHOD (turnover numbers are difficult to compare because of the difference in pH conditions). It is difficult to compare the reactivity with oxygen in the NADH oxidase reaction between B. bifidum DHOD and L. lactis b-type DHOD because no data have been provided for the pH optimum of the NADH oxidase reaction in L. lactis b-type DHOD.

In anaerobes lacking an O2 respiratory chain, H2O-forming-type NADH oxidase has been purified and characterized as the central O2 metabolic enzyme from several bacterial species, including E. faecalis (41), S. mutans (13), Clostridium aminovalericum (18), and Thermotoga hypogea (49). This enzyme is distributed widely in the genome of anaerobes and facultative anaerobes and is proposed to be involved in the detoxification of O2 to H2O. The kinetic parameters for molecular oxygen have been reported for the H2O-forming-type NADH oxidases from C. aminovalericum (18) and T. hypogea (49) as Kms for O2 of 61.9 and 85 μM, respectively. The O2 concentration of the air-saturated medium is approximately 210 μM at the growth temperature, suggesting that the reactivity of the B. bifidum DHOD toward O2 (apparent Km for O2 = 779 ± 82 μM) is significantly lower than that of H2O-forming NADH oxidase. When comparing the specific activities of NADH oxidase reactions among enzymes under air-saturated conditions at 37°C, B. bifidum DHOD (29.1 U/mg protein) is estimated to have one-third to one-fifth of the specific activity of the H2O-forming NADH oxidase (e.g., the specific activity of C. aminovalericum NADH oxidase is 130 U/mg of protein [18] and that of S. mutans NADH oxidase is 100 U/mg of protein [13]). A BLAST search of the public genome databases for B. longum and B. adolescentis identified a homologue of H2O-forming NADH oxidase in B. longum (accession number NP_696431) but not in B. adolescentis. Although it is not clear whether the gene is conserved in B. bifidum, the H2O-forming-type activity was not detected in any fraction during purification. These results suggest that the gene does not exist or that the protein is expressed at levels below the detection limit in B. bifidum.

B. bifidum suffers oxidative growth inhibition over a range of 10 to 21% (air) O2 conditions (approximately 100 μM to 210 μM dissolved O2 in the medium). When the cells are grown under 5% O2 conditions (approximately 50 μM dissolved O2), they grow well without accompanying H2O2 production (21). These results indicated that H2O2 production depends on the concentration of dissolved O2. This O2-dependent growth of B. bifidum is closely correlated with the reactivity of B. bifidum DHOD to O2.

In this study, B. bifidum DHOD was proposed to play a central role in the production of H2O2 under highly aerated conditions. Although a gene disruption technique has not been established for Bifidobacterium species, mutation work will help to clarify the involvement of this enzyme in oxidative growth inhibition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Tohru Kodama and Junichi Nakagawa for valuable discussions. We also thank Jun Anzai, Tomohiro Kobayashi, Hiroshi Osawa, Kazuya Kobayashi, Hiroshi Fukuyama, and Kunifusa Tanaka for helpful technical assistance at the Tokyo University of Agriculture.

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for scientific research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to S.K.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 December 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen, P. S., P. J. Jansen, and K. Hammer. 1994. Two different dihydroorotate dehydrogenases in Lactococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 176:3975-3982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen, P. S., J. Martinussen, and K. Hammer. 1996. Sequence analysis and identification of the pyrKDbF operon from Lactococcus lactis including a novel gene, pyrK, involved in pyrimidine biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 178:5005-5012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appleby, C. A. 1969. Inhibitors of respiratory enzymes, photosynthesis and phosphorylation; uncoupling reagents, p. 380-387. In R. M. Dawson, D. C. Elliott, W. H. Elliott, and K. M. Jones (ed.), Data for biochemical research. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 4.Argyrou, A., M. W. Washabaugh, and C. M. Pickart. 2000. Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase from Clostridium oroticum is a class 1B enzyme and utilizes a concerted mechanism of catalysis. Biochemistry 39:10373-10384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baughn, A. D., and M. H. Malamy. 2004. The strict anaerobe Bacteroides fragilis grows in and benefits from nanomolar concentrations of oxygen. Nature 427:441-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Björnberg, O., P. Rowland, S. Larsen, and K. F. Jensen. 1997. Active site of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase A from Lactococcus lactis investigated by chemical modification and mutagenesis. Biochemistry 36:16197-16205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brioukhanov, A. L., and A. I. Netrusov. 2004. Catalase and superoxide dismutase: distribution, properties, and physiological role in cells of strict anaerobes. Biochemistry 69:949-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Combe, J. P., J. Basran, P. Hothi, D. Leys, S. E. Rigby, A. W. Munro, and N. S. Scrutton. 2006. Lys-D48 is required for charge stabilization, rapid flavin reduction, and internal electron transfer in the catalytic cycle of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase B of Lactococcus lactis. J. Biol. Chem. 281:17977-17988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Vries, W., and A. H. Stouthamer. 1969. Factors determining the degree of anaerobiosis of Bifidobacterium strains. Arch. Mikrobiol. 65:275-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolla, A., M. Fournier, and Z. Dermoun. 2006. Oxygen defense in sulfate-reducing bacteria. J. Biotechnol. 126:87-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fareleira, P., B. S. Santos, C. António, P. Moradas-Ferreira, J. LeGall, A. V. Xavier, and H. Santos. 2003. Response of a strict anaerobe to oxygen: survival strategies in Desulfovibrio gigas. Microbiology 149:1513-1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higuchi, M., M. Shimada, Y. Yamamoto, T. Hayashi, T. Koga, and Y. Kamio. 1993. Identification of two distinct NADH oxidases corresponding to H2O2-forming oxidase and H2O-forming oxidase induced in Streptococcus mutans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139:2343-2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hwang, I. T., Y. J. Kim, S. H. Kim, C. I. Kwak, Y. Y. Gu, and J. Y. Chun. 2003. Annealing control primer system for improving specificity of PCR amplification. BioTechniques 35:1180-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones, D., and M. D. Collins. 1986. Irregular, nonsporing gram-positive rods, p. 1261-1434. In P. H. A. Sneath, N. S. Mair, M. E. Sharpe, and J. G. Holt (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. The Williams & Wilkins Co., Baltimore, MD.

- 16.Kahler, A. E., and R. L. Switzer. 1996. Identification of a novel gene of pyrimidine nucleotide biosynthesis, pyrDII, that is required for dihydroorotate dehydrogenase activity in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178:5013-5016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawasaki, S., T. Nakagawa, Y. Nishiyama, Y. Benno, T. Uchimura, K. Komagata, K. Kozaki, and Y. Niimura. 1998. Effect of oxygen on the growth of Clostridium butyricum (type species of the genus Clostridium), and the distribution of enzymes for oxygen and for active oxygen species in clostridia. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 86:368-372. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawasaki, S., J. Ishikura, D. Chiba, T. Nishino, and Y. Niimura. 2004. Purification and characterization of an H2O-forming NADH oxidase from Clostridium aminovalericum: existence of an oxygen-detoxifying enzyme in an obligate anaerobic bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 181:324-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawasaki, S., J. Ishikura, Y. Watamura, and Y. Niimura. 2004. Identification of O2-induced peptides in an obligatory anaerobe, Clostridium acetobutylicum. FEBS Lett. 571:21-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawasaki, S., Y. Watamura, M. Ono, T. Watanabe, K. Takeda, and Y. Niimura. 2005. Adaptive responses to oxygen stress in obligatory anaerobes Clostridium acetobutylicum and Clostridium aminovalericum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8442-8450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawasaki, S., T. Mimura, T. Satoh, K. Takeda, and Y. Niimura. 2006. Response of microaerophilic Bifidobacterium boum and Bifidobacterium thermophilum to oxygen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:6854-6858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawasaki, S., M. Nagasaku, T. Mimura, H. Katashima, S. Ijuin, T. Satoh, and Y. Niimura. 2007. Effect of CO2 on the colony development of Bifidobacterium species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:7796-7798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knecht, W., U. Bergjohann, S. Gonski, B. Kirschbaum, and M. Löffler. 1996. Functional expression of a fragment of human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase by means of the baculovirus expression vector system, and kinetic investigation of the purified recombinant enzyme. Eur. J. Biochem. 240:292-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsen, J. N., and K. F. Jensen. 1985. Nucleotide sequence of the pyrD gene of Escherichia coli and characterization of the flavoprotein dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. Eur. J. Biochem. 151:59-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lieberman, I., and A. Kornberg. 1953. Enzymic synthesis and breakdown of a pyrimidine, orotic acid. I. Dihydro-orotic dehydrogenase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 12:223-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lobo, S. A., A. M. Melo, J. N. Carita, M. Teixeira, and L. M. Saraiva. 2007. The anaerobe Desulfovibrio desulfuricans ATCC 27774 grows at nearly atmospheric oxygen levels. FEBS Lett. 581:433-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marcinkeviciene, J., L. M. Tinney, K. H. Wang, M. J. Rogers, and R. A. Copeland. 1999. Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase B of Enterococcus faecalis. Characterization and insights into chemical mechanism. Biochemistry 38:13129-13137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller, R. W., and V. Massey. 1965. Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. I. Some properties of the enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 240:1453-1465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morishita, T., N. Tamura, T. Makino, and S. Kudo. 1999. Production of menaquinones by lactic acid bacteria. J. Dairy Sci. 82:1897-1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mukhopadhyay, A., A. M. Redding, M. P. Joachimiak, A. P. Arkin, S. E. Borglin, P. S. Dehal, R. Chakraborty, J. T. Geller, T. C. Hazen, Q. He, D. C. Joyner, V. J. Martin, J. D. Wall, Z. K. Yang, J. Zhou, and J. D. Keasling. 2007. Cell-wide responses to low-oxygen exposure in Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. J. Bacteriol. 189:5996-6010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagy, M., F. Lacroute, and D. Thomas. 1992. Divergent evolution of pyrimidine biosynthesis between anaerobic and aerobic yeasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:8966-8970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nielsen, F. S., P. S. Andersen, and K. F. Jensen. 1996. The B form of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase from Lactococcus lactis consists of two different subunits, encoded by the pyrDb and pyrK genes, and contains FMN, FAD, and [FeS] redox centers. J. Biol. Chem. 271:29359-29365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nielsen, F. S., P. Rowland, S. Larsen, and K. F. Jensen. 1996. Purification and characterization of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase A from Lactococcus lactis, crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction studies of the enzyme. Protein Sci. 5:852-856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nölling, J., G. Breton, M. V. Omelchenko, K. S. Makarova, Q. Zeng, R. Gibson, H. M. Lee, J. Dubois, D. Qiu, J. Hitti, Y. I. Wolf, R. L. Tatusov, F. Sabathe, L. Doucette-Stamm, P. Soucaille, M. J. Daly, G. N. Bennett, E. V. Koonin, and D. R. Smith. 2001. Genome sequence and comparative analysis of the solvent-producing bacterium Clostridium acetobutylicum. J. Bacteriol. 183:4823-4838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Donovan, G. A., and J. Neuhard. 1970. Pyrimidine metabolism in microorganisms. Bacteriol. Rev. 34:278-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Page, R. D. 1996. TreeView: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 12:357-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poulsen, P., K. F. Jensen, P. Valentin-Hansen, P. Carlsson, and L. G. Lundberg. 1983. Nucleotide sequence of the Escherichia coli pyrE gene and of the DNA in front of the protein-coding region. Eur. J. Biochem. 135:223-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rocha, E. R., T. Selby, J. P. Coleman, and C. J. Smith. 1996. Oxidative stress response in an anaerobe, Bacteroides fragilis: a role for catalase in protection against hydrogen peroxide. J. Bacteriol. 178:6895-6903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rowland, P., F. S. Nielsen, K. F. Jensen, and S. Larsen. 1997. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of the heterotetrameric dihydroorotate dehydrogenase B of Lactococcus lactis, a flavoprotein enzyme system consisting of two PyrDB subunits and two iron-sulfur cluster containing PyrK subunits. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53:802-804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rowland, P., S. Nørager, K. F. Jensen, and S. Larsen. 2000. Structure of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase B: electron transfer between two flavin groups bridged by an iron-sulphur cluster. Structure 8:1227-1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidt, H. L., W. Stöcklein, J. Danzer, P. Kirch, and B. Limbach. 1986. Isolation and properties of an H2O-forming NADH oxidase from Streptococcus faecalis. Eur. J. Biochem. 156:149-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shah, N. P. 2000. Probiotic bacteria: selective enumeration and survival in dairy foods. J. Dairy Sci. 83:894-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimamura, S., F. Abe, N. Ishibashi, H. Miyakawa, T. Yaeshima, T. Araya, and M. Tomita. 1992. Relationship between oxygen sensitivity and oxygen metabolism of Bifidobacterium species. J. Dairy Sci. 75:3296-3306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sund, C. J., E. R. Rocha, A. O. Tzinabos, W. G. Wells, J. M. Gee, M. A. Reott, D. P. O'Rourke, and C. J. Smith. 2008. The Bacteroides fragilis transcriptome response to oxygen and H2O2: the role of OxyR and its effect on survival and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 67:129-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Talwalkar, A., and K. Kailasapathy. 2004. The role of oxygen in the viability of probiotic bacteria with reference to L. acidophilus and Bifidobacterium spp. Curr. Issues Intest. Microbiol. 5:1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trudinger, P. A. 1969. Thiol reagents, p. 388-395. In R. M. Dawson, D. C. Elliott, W. H. Elliott, and K. M. Jones (ed.), Data for biochemical research. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 48.Wildschut, J. D., R. M. Lang, J. K. Voordouw, and G. Voordouw. 2006. Rubredoxin:oxygen oxidoreductase enhances survival of Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough under microaerophilic conditions. J. Bacteriol. 188:6253-6260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang, X., and K. Ma. 2005. Purification and characterization of an NADH oxidase from extremely thermophilic anaerobic bacterium Thermotoga hypogea. Arch. Microbiol. 183:331-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.