Abstract

Over the last decade schizophrenia researchers have turned their attention to earlier identification in the prodromal period of illness. A greater understanding of both risk and protective factors can lead to improved prevention and treatment strategies in this vulnerable population. This research, however, has far-reaching ethical implications. One year follow-up data from 50 individuals who met established criteria for a prodromal state is used to illustrate ethical issues that directly affect clinicians and future research strategies. At 1-year follow-up, the psychotic transition rate was 13%, but it increased in subsequent years with smaller sample sizes. One-half developed an affective psychosis. The converted sample was older (p > 0.05) than the nonconverted sample and more likely to have a premorbid history of substance abuse, as well as higher clinical ratings on “subsyndromal” psychotic items (delusional thinking, suspiciousness, and thought disorder). Despite a lack of conversion, the nonconverted sample remained symptomatic and had a high rate of affective and anxiety disorders with evidence of functional disability. This conversion rate is relatively low compared to similar studies at 1 year. Specific risk factors were identified, but these findings need to be replicated in a larger cohort. By examining the rate of conversion and nonconversion in this sample as an example, we hope to contribute to the discussion of implications for clinical practice and the direction of future research in the schizophrenia prodrome. Finally, our data strengthen the evidence base available to inform the discussion of ethical issues relevant to this important research area.

Keywords: first episode, substance abuse, familial

Introduction

Important aims of schizophrenia research have been not only to learn about the pathogenesis of the illness but also to improve our ability to diagnose early and hence provide early treatment for psychosis. Outcome studies have found an association between the duration of untreated psychosis and poor functional outcome,1 suggesting the possible toxic effect of psychosis on the brain,2 but clear causation has not been established. With the potential of making an impact on the course of schizophrenia by intervening early and preventing many of the devastating effects of the illness, greater emphasis in schizophrenia research has been placed on the identification of individuals in the prodromal phase of schizophrenia.

In 1996 Yung, McGorry and their colleagues3 set up a clinic in Australia to monitor and care for young people considered at a high risk for developing psychosis based on demographic and symptom measures. They selected individuals in an age range that is at higher risk for schizophrenia (14–30 years) who had recently developed subsyndromal psychotic symptoms and/or had a familial risk for schizophrenia plus a recent deterioration in functioning. Using these criteria, Yung et al. reported a 40% conversion rate to psychosis at the end of 1 year.4 The Australian program inspired the development of similar programs worldwide.5–13 These programs are actively engaged in studying individuals at risk for developing psychosis in an effort to learn more about the “at risk” states and to assess the predictive power and diagnostic efficiency of the prodromal criteria for the eventual development of schizophrenia.

These prodromal research programs may have far-reaching clinical implications. In addition, ethical considerations surrounding prodromal research remain a fundamental concern of investigators worldwide.6,14–17 For example, a number of questions have been raised in terms of how to best identify who is at risk and the potential stigmatization, loss of confidentiality, and insurability problems these individuals may encounter.15,18 The base rates for conversion to schizophrenia have not been established in large samples,15 and the early clinical trials in the at-risk population have been criticized for having too many false positives (or subjects who do not convert to schizophrenia) to justify early treatment with antipsychotic agents.15,17,19 The rate of false positives in some studies has been as high as 60–90 %,4,5,9,16,20–30 leading to unfavorable risk-to-benefit ratios in studies with lower conversion rates. The rates of conversion vary across studies, depending on prodromal assessment methods, age of the subjects, sample size, and follow-up time (Table 1). This false positive group likely includes individuals who fit the “prodromal” criteria but were not really destined to convert; those who are truly at risk and are somehow protected or have not had the second “hit” necessary to convert but still may develop psychosis in the future. There are also concerns regarding the risks of treating false positive subjects with unnecessary medication16,31 and the need for an exit strategy (when or if to ever stop treatment),15,32 as well as risks of treating true positives with placebo.16 Additionally, the heterogeneity of the at-risk samples has raised the question of whether antipsychotics should be the first line of treatment.15 In a recent review Corcoran, Malaspina, and Hercher14 note that the negative impact of intervention on the patients’ lives will potentially increase in any shift toward a target population that is younger, less symptomatic, or less strictly delineated.

Table 1.

Comparison of Prodromal Schizophrenia Studies

| Manuscript (Clinic) | Prodromal Assessment Instrument | Age (in years) Mean (SD) [Range] | Convert/Total (%) | Follow-up Mean (SD) [Range] | Psychosis Outcome | Notes |

| Klosterkotter et al. 20015 (CER Clinic) | BSABS, PSE9 | 29.3 (10.0) | 79/160 (49.4%) | 9.6 (7.6) | SZ | |

| 28.8 (9.8) | 77/110 (70%)a | years | ||||

| Carr et al. 200024 (PAS Clinic) | PACE Criteria | 17.6b | 2/23 (9%) | 14.6 months [4–34] | 50% SZform | |

| 50% PsyNOS | ||||||

| Mason et al. 200430 (PAS Clinic) | PACE Criteria | 17.3 (2.8) [13–28] | 37/74 (50%) | 26.3 (9.2) months | 19% SZ | Most conversions came from BLIPS group (14/23), followed by Attenuated group (21/43), and least from Trait and State Group (2/13). |

| 27% SAD | ||||||

| 19% MDD/P | ||||||

| 11% BPD/P | ||||||

| 24% not reported | ||||||

| Yung et al. 199626 (PACE Clinic) | PACE Criteria | 19 [15–26] | 7/33 (21.2%) | 1 year | Low conversion may be due to inclusion of first- and second-degree relatives of SZ patients in at-risk group. | |

| Yung et al. 199827 (PACE Clinic) | PACE Criteria/ CAARMS | [16–30] | 8/20 (40%) | 6 months | Only first-degree relatives of SZ patients included in “State/Trait” group. | |

| McGorry et al., 200225 (PACE Clinic) | CAARMS | 20 (3) [14–30] | 10/28 (36%) | 1 year | 44% SZ or SZform | Clinical Trial: No antipsychotic; received therapy and non-antipsychotic medication. |

| 19% MDD/P | ||||||

| 19% BPD/P | ||||||

| 6% Brief Psych | ||||||

| 6% PsyNOS | ||||||

| 20 (4) [14–30] | 6/31 (19%) | 1 year | 6% Sub Induced | Clinical Trial: Received antipsychotic and treatment offered above. | ||

| 20 (4) [14-30] | 6/33 (18.2%) | 1 year | not reported | Subjects who refused participation in drug trial | ||

| Yung et al. 20034 (PACE Clinic) | PACE Criteria | 19.1 (3.8) [14–28] | 20/49 (40.8%) | 1 year | 65% SZ | Subjects did not receive antipsychotic medication. |

| 5% SAD | ||||||

| 5% BPD/P | ||||||

| 10% MDD/P | ||||||

| 5% Brief Psych | ||||||

| 10% PsyNOS | ||||||

| Yung et al. 200428 (PACE Clinic) | CAARMS | 19.4 (3.5) [14–28] | 29/104 (17.9%) | 6 months | 55.5% SZ | Subjects did not receive neuroleptic medication. Subset of 49 subjects are from Yung 2003 sample. |

| 36/104 (34.6%) | 1 year | 25% Affect Psych | ||||

| 41/104 (39.4%) | 15–28 months | 5.5% SAD | ||||

| 5.5% Brief Psych | ||||||

| 5.5% PsyNOS | ||||||

| 3% Sub Induced | ||||||

| Yung 200420 abstract (PACE Clinic) | 23/92 (25%)c | 1 year | 92 total (59 randomized in treatment study, 33 followed without randomization). | |||

| 31/92 (34%)c | 2 year | |||||

| Lencz et al. 200323 (RAP Program) | SIPS, CHR+, CHR− | 16.4 (2.3) [11–22] | 9/34 (26.5%) | 24.7 months (15.9) | 44.4% SZ | Excluded subjects with history of symptoms that crossed into psychosis. Group is a subsample of Phase I in Cornblatt et al. 2003.29 |

| ≥ 6 months | 22.2% SAD | |||||

| 11.1% Del Dis | ||||||

| 22.2% PsyNOS | ||||||

| Cornblatt et al. 200329 (RAP Program) | SIPS, CHR+, CHR− | 16.4 (2.3)d [12–22] | CHR+sev 7/15 (47%) | ∼1 year | ||

| CHR+mod 2/19 (11%) CHR−0/14 (0%) | ≥ 6 months | |||||

| Cornblatt et al., 200467 (RAP Program) | SIPS, CHR+, CHR− | (25%) | ≥ 6 months | |||

| Larsen et al. | SIPS | 4/8 (50%) | 1 year | Unpublished data reported in McGlashan, Miller, and Woods 200165 | ||

| Miller et al. 20029 (PRIME Clinic) | SIPS | 17.8 (6.1)e | 6/13 (46%) | 6 months | ||

| 7/13 (54%) | 1 year | |||||

| Miller et al. 200466 abstract (PRIME Clinic) | SIPS | 8/20 (40%) | 1 year | Subjects randomized to placebo. | ||

| 12/17 (70.5%) | 2 years | |||||

| 13/17 (76%) | 3 years | |||||

| McGlashan et al. 200522abstract (PRIME Clinic) | SIPS | 21/60 (35%) | 2 years | Randomized double- blind placebo-controlled trial of olanzapine. Placebo conversion was 4 times olanzapine conversion. In no-treatment year, 3 of 9 of former olanzapine patients converted. | ||

| Skeate, Patterson, and Birchwood 200421 abstract (ED:IT) | BSABS, PACE criteria | 2/30 (6.6%) | 6 months |

Note: CER = Cologne Early Recognition Project, Cologne, Germany; BSABS = Bonn Scale for the Assessment of Basic Symptoms; PSE9 = Ninth Version of the Present State Examination; PAS = Psychological Assistance Program, New Castle, South Wales; PACE = Personal Assessment and Crisis Evaluation Clinic, Melbourne, Australia: PACE Criteria are composite of family history and symptom rating scales; ARMS = At-Risk Mental States; CAARMS = Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States; BLIPS = Brief Limited Intermittent Psychotic Symptoms; RAP = Recognition and Prevention Program, New York; CHR+ = clinical high risk with positive symptoms; CHR− = clinical high risk with negative symptoms; CHR+ sev = clinical high risk with severe (nonpsychotic) attenuated positive symptoms; CHR+ mod = clinical high risk with moderate attenuated positive symptoms; SIPS = Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes; PRIME = Prevention through Risk Identification, Management, and Education, New Haven, Conn; SZ = schizophrenia; SZform = schizophreniform; BPD/P = bipolar disorder with psychotic features; MDD/P = major depression with psychotic features; PsyNOS = Psychosis not otherwise specified; Brief Psych = Brief Psychotic Disorder; SAD = schizoaffective disorder; Del Dis = delusional disorder; Sub induced = substance induced psychosis; Aff Psy = affective psychosis.

Of the 160 subjects, 110 met prodromal sxs per BSABS, and 77 of the 110 converted.

Based on 60 subjects.

Conversion based on whole sample.

Based on larger sample of 62 subjects.

Based on larger sample. 13 met prodromal criteria.

Provocative and convincing arguments have been made for both initiating randomized clinical trials in the at-risk sample and withholding treatment until a more definitive diagnosis is made.11,15–17,31,33 It has been argued that we need “number needed to treat” data (NNT—the number of patients one needs to treat to prevent one additional bad outcome) from randomized clinical trials to assist patients and families in making informed decisions.17 With the brewing debate about potential treatment of prodromal subjects in the schizophrenia literature, concern has also been expressed that community clinicians may want to initiate early antipsychotic treatment in at-risk patients before we have definitive NNT data and decrease the pool of potential subjects for clinical trials in which base rates can be determined.16 Despite the controversy regarding risk/benefits of early interventions for schizophrenia, there are indications that the use of antipsychotics in children and adolescents has been increasing.34,35 Additionally, recent marketing by the pharmaceutical industry has advocated the use of atypical antipsychotics for a variety of nonpsychotic conditions such as mood or anxiety disorders.36–38 Now clinicians are more willing to use an antipsychotic agent to target a variety of mood, anxiety, or behavioral problems that do not necessarily include psychosis.

The CARE (Cognitive Assessment and Risk Evaluation) program is a National Institute of Mental Health–funded longitudinal study that is modeled after the program in Australia. One of the primary aims of the CARE program is to improve early identification of psychosis and decrease the false positive rate by also assessing brain-based vulnerability markers for schizophrenia. At-risk subjects in the CARE program receive treatment as usual (both pharmacological and psychosocial) according to presenting symptoms and are not participating in a clinical trial. The current report assesses the clinical and demographic data of 50 subjects enrolled in the CARE program at the end of 1 year. Comparisons are made between those individuals who had converted to psychosis and those who had not. Given the high false positive rate of this population in published reports, another objective was to further assess those individuals who did not convert to psychosis. The plan was to develop hypotheses as to why this population initially fit the prodromal criteria and did not convert to psychosis and to determine whether it is possible to identify factors that protected them or delayed conversion. Additionally, by examining the rate of conversion and nonconversion in this sample of individuals, we hope to contribute to the discussion of implications for clinical practice and the direction of future research in the schizophrenia prodrome. Finally, our data can serve to strengthen the evidence base available to inform the discussion of empirical ethics regarding this important area of research.

METHOD

A full description of the CARE program is detailed in a recent review.39 Fifty individuals (29 males and 21 females) between the ages of 12 and 30 were considered at risk for schizophrenia based on published criteria. The mean age of the sample was 18.7 years (range 12–30), and mean education was 10.8 years (range 6–16). Clinical and demographic information from a larger sample of 62 individuals, some of whom have not been followed for 1 year, is reported in the review article.39 The procedure of this study was fully explained to all subjects and/or their legal guardians. All subjects signed informed consent (or assent with parental consent if under age 18) (IRB# 030829). At-risk subjects were not told that they were specifically at risk for schizophrenia or psychosis but were presented with a broad differential diagnosis with a focus on presenting symptoms. It was made clear that they had been referred to the study because they had had changes in their thoughts, behavior, or emotions and that the research program was specifically interested in problems experienced by young people. They were told that the study was designed to understand more about the difficulties they were having and to provide support and education to them and their families. Past medical and school records were requested with consent. Subjects were also asked to identify a family informant to provide family history information, also with appropriate consent. Subjects were re-consented on a biannual basis after yearly institutional review board (IRB) reviews. At intake all potential at-risk subjects received a comprehensive clinical assessment and were reassessed at monthly intervals for 1 year. Any subject who needed psychiatric care during the course of the study was provided treatment regardless of their funding status. Some subjects were referred to outpatient clinics, and others already had a treating psychiatrist.

Recruitment and Assessment

We have a referral network in place in the city of San Diego that involves regular outreach and education. All potential participants were screened for possible exclusions (neurological illness, psychotic diagnosis) then interviewed using the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (SIPS)9 to determine whether they met entry criteria for a putative prodromal state (since this diagnosis can only truly be made retrospectively), according to the Criteria of Prodrome Syndromes (COPS) from the SIPS, as well as the CARE, prodromal criteria.39 Both sets of criteria include a Brief Intermittent Psychotic Symptom Syndrome, an Attenuated Positive Symptom Syndrome, and a Genetic Risk and Deterioration Syndrome that all require a recent onset of symptoms and/or functional deterioration. The CARE prodromal criteria use the same symptom severity criteria from the COPS but differ slightly in the frequency and duration of symptoms, as well as in the degree of functional decline (any decline in functioning per CARE versus a 30% drop in Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score required by the COPS) in the Genetic Risk and Deterioration Prodromal Syndrome. Axis I disorders were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV40 or the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children: Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS),41 and symptoms were assessed using the Schedules for Negative and Positive Symptoms42,43 (SANS/SAPS) Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).44 The Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders45 was used to assess Axis II disorders, and the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria46 was used to assess family history of mental disorders.

Statistical Analyses

The dependent variable in the analysis was conversion to psychosis as defined by the Psychotic Syndrome criteria of the SIPS. Comparisons were made between those individuals who had converted to psychosis and those who had not at 1 year. A Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis was performed to assess rate of conversion. Appropriate parametric or nonparametric analyses were performed to compare clinical and demographic variables between groups to identify risk factors for conversion to psychosis and potential protective factors. Additional exploratory analyses were performed to characterize the group of individuals who have not converted to psychosis.

Results

Follow-Up Assessment of At-Risk Subjects

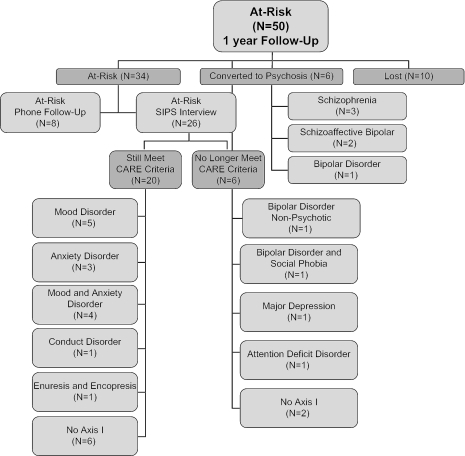

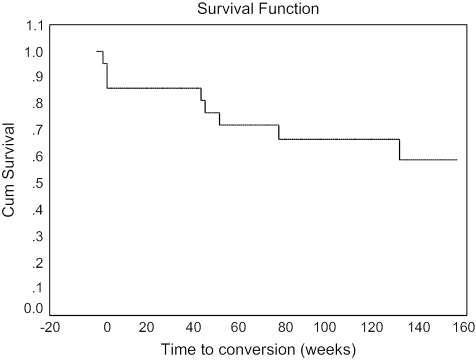

At 1-year assessment, 20% of the original at-risk sample was lost to follow-up, and 15% had made the transition to psychosis (see Figure 1). Using a Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis, the transition rate was 0.13 (SEM = 0.05) at 1 year (see Figure 2). Of those who became psychotic, 50% met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia, and 50% met criteria for bipolar disorder or schizoaffective disorder–bipolar type. One-half of the individuals who converted to psychosis did so within the first 4 weeks of the study, while the remainder made the conversion between 6 months and 1 year (mean 25.3 [SD = 24.3] weeks). Kaplan-Meier Survival Analyses performed at year 2 (0.20 [SEM = 0.07], N = 39) and year 3 (0.30 [SEM = 0.09], N = 31) showed an increasing rate of conversion in subsequent years with smaller sample sizes.

Fig. 1.

Flow Chart Showing 1-Year Follow-up Data of Individuals Identified as at Risk for Psychosis (N = 50) Using Established Criteria.

Fig. 2.

Survival Function of Subjects at Risk for Psychosis (N = 50) Over 3 Years.

Conversion to Psychosis

Baseline clinical and demographic variables were compared in order to identify predictors of a psychotic diagnosis at 1-year follow-up (see Table 2). The converted versus the nonconverted samples did not statistically differ in age, but the converted group had a mean age of 1.2 years greater than the nonconverted. All but one of the individuals who converted to psychosis were over 20 years of age. The converted group was more likely to have taken an antipsychotic agent, less likely to have a family history of psychosis in a first-degree relative, and more likely to have a history of substance abuse or dependence than the nonconverted group. The converted group also had higher clinical ratings at baseline on the SIPS positive items, SAPS, and BPRS than did the nonconverted group. Measures of delusional-like experiences, suspiciousness, and thought disorder on each of the scales best differentiated the converted from the nonconverted sample.

Table 2.

Comparison of Baseline Information of Individuals Who Had Converted to Psychosis at 1-Year Follow-up Versus Those Who Had Not

| At-Risk Subjects | Nonconverted (N = 34) | Converted (N = 6) | χ2 or t38 | p |

| Age (SD) | 18.3 (4.6) | 19.5 (3.0) | 0.61 | NS |

| Education (SD) | 10.7 (3.0) | 11.0 (1.7) | 0.23 | NS |

| Gender (male:female) | 21:13 | 2:4 | 1.69 | NS |

| Antipsychotic medication % | 21 | 67 | 5.43 | 0.02 |

| Psychotropic medication % | 56 | 83 | 1.60 | NS |

| Family history of psychosis % | 26 | 0 | 2.05 | NS |

| SPD diagnosis % | 47 | 33 | 0.39 | NS |

| Substance abuse history % | 29 | 83 | 6.33 | .012 |

| Comorbid mood disorder % | 53 | 33 | 0.78 | NS |

| Comorbid anxiety disorder % | 35 | 17 | 0.81 | NS |

| SIPS Positive Symptoms total (SD) | 10.1 (4.5) | 15.7 (4.7) | 2.81 | 0.008 |

| Unusual thought content | 2.7 (1.6) | 4.5 (1.4) | 2.63 | 0.012 |

| Suspiciousness | 1.9 (1.5) | 4.5 (1.2) | 4.05 | 0.000 |

| Grandiose ideas | 1.3 (1.6) | 1.7 (2.1) | 0.47 | NS |

| Perceptual abnormalities | 2.7 (2.1) | 2.2 (0.8) | 0.58 | NS |

| Disorganized communication | 1.4 (1.3) | 2.8 (1.5) | 2.42 | 0.021 |

| SIPS Negative Symptoms total (SD) | 9.5 (6.6) | 15.2 (8.6) | 1.85 | 0.07 |

| Social anhedonia or withdrawal | 1.7 (1.5) | 2.8 (2.0) | 1.66 | NS |

| Avolition | 2.0 (1.7) | 2.3 (1.2) | 0.42 | NS |

| Decreased expression of emotion | 1.4 (1.8) | 2.5 (1.8) | 1.35 | NS |

| Decreased experience of self | 0.9 (1.2) | 3.0 (2.3) | 3.38 | 0.002 |

| Decreased ideational richness | 0.9 (1.4) | 2.2 (1.5) | 2.17 | 0.036 |

| Deterioration in role functioning | 2.3 (1.8) | 2.7 (2.2) | 0.46 | NS |

| SIPS Disorganized Symptoms total (SD) | 6.2 (3.9) | 8.3 (5.1) | 1.16 | NS |

| Odd behavior or appearance | 1.4 (1.5) | 2.7 (1.8) | 1.85 | NS |

| Bizarre thinking | 1.5 (1.4) | 2.2 (1.7) | 1.04 | NS |

| Trouble with focus and attention | 1.9 (1.4) | 2.5 (1.5) | 0.87 | NS |

| Personal hygiene/social attentiveness | 1.2 (1.6) | 1.0 (1.3) | 0.26 | NS |

| SIPS General Symptoms total (SD) | 5.9 (4.0) | 8.8 (6.5) | 1.51 | NS |

| Sleep disturbance | 1.2 (1.3) | 2.0 (2.3) | 1.24 | NS |

| Dysphoric mood | 2.0 (1.5) | 2.8 (2.1) | 1.20 | NS |

| Motor disturbances | 0.9 (1.4) | 0.8 (1.0) | 0.13 | NS |

| Impaired tolerance to normal stress | 1.6 (1.7) | 3.0 (2.4) | 1.72 | NS |

| Global SAPS (SD) | 5.2 (2.7) | 8.0 (4.0) | 2.2 | 0.035 |

| Hallucinations | 1.6 (1.4) | 1.3 (0.8) | 0.37 | NS |

| Delusions | 1.9 (1.0) | 2.8 (1.0) | 2.15 | 0.038 |

| Bizarre behavior | 0.9 (1.1) | 1.3 (1.5) | 0.86 | NS |

| Formal thought disorder | 0.8 (1.2) | 2.3 (1.4) | −2.8 | 0.008 |

| Global SANS (SD) | 5.9 (4.1) | 8.5 (4.2) | –1.8 | NS |

| Affective blunting | 1.5 (1.5) | 2.7 (0.5) | –1.84 | NS |

| Alogia | 0.4 (0.9) | 1.0 (1.7) | –1.29 | NS |

| Avolition | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.7 (1.4) | 0.12 | NS |

| Anhedonia | 1.9 (1.4) | 2.3 (1.2) | –0.66 | NS |

| Attention | 0.3 (0.9) | 0.8 (1.3) | –1.37 | NS |

| BPRS Total (SD) | 14.8 (5.4) | 23.8 (2.6) | –4.0 | 0.000 |

| Thought disorder | 5.9 (3.3) | 10.0 (2.4) | –2.94 | 0.006 |

| Withdrawal-retardation | 3.8 (3.5) | 9.2 (3.9) | –3.44 | 0.001 |

| Anxious-depression | 5.3 (2.9) | 6.7 (3.9) | –0.99 | NS |

| Hostile-suspicious | 3.2 (2.0) | 4.7 (2.2) | –1.60 | NS |

| Activation | 1.1 (1.2) | 3.5 (2.4) | –4.02 | 0.000 |

| GAF (SD) | 53.3 (12.2) | 52.5 (7.5) | 0.15 | NS |

Note: SPD = Schizotypal Personality Disorder; SIPS = Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes; SAPS = Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms; SANS = Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; GAF = Global Assessment of Functioning.

“False Positive Group”

Of the 34 subjects who had not converted to psychosis at 1 year, 26 were seen in a face-to-face follow-up interview, while 8 were contacted and interviewed by phone, and it was determined that they had not converted to psychosis. Of the subjects who were interviewed in person, 6 no longer met CARE criteria for a prodromal state.

Of the 6 who no longer met CARE criteria at 1 year, 2 did not have an Axis I disorder, and 4 met DSM-IV criteria for major depression, social phobia, attention deficit disorder, and/or bipolar disorder. One subject without a clear Axis I disorder had intermittently met “prodromal criteria” throughout the year, did not receive pharmacologic treatment, and did not have symptoms that met severity threshold at 1 year. The other 5 subjects who no longer met CARE criteria had been on psychotropic medication (eg, antidepressant or mood stabilizer) during the last year, including 1 subject who had been on an antipsychotic since entry into the study.

Of the 20 subjects who still met CARE prodromal criteria at follow-up, 60% had subsyndromal psychotic symptoms that met inclusion criteria for the Attenuated Positive Symptom Group; 55% met criteria for schizotypal personality disorder, and 25% had a first-degree relative with schizophrenia, which put them in the Genetic Risk and Deterioration group. In terms of DSM-IV Axis I disorders, 20% had no Axis I disorder, 45% were diagnosed with a mood disorder (major depression, dysthymia, bipolar disorder, or mood disorder not otherwise specified [NOS]) and 30% were diagnosed with an anxiety disorder (panic disorder, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or anxiety disorder NOS). Thirty percent were receiving psychotropic medication (including antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and mood stabilizers but no antipsychotics), while 70% were unmedicated.

Discussion

In the current sample of individuals who were defined as at risk for psychosis based on clinical presentation, familial history of schizophrenia, and functional decline, there was a 13% risk of transition to psychosis within the first year. One-half developed schizophrenia, and one-half developed an affective psychosis. Individuals who had a greater severity of subsyndromal psychotic symptoms and had a history of drug abuse were more likely to make the conversion. This conversion rate is lower than some but not all published reports using similar entry criteria and may be related to the relatively young age of our sample (mean age 18.7) compared to other samples.5,9,28 Furthermore, the rate of conversion will likely be higher after 2 to 3 years. It is also possible that the ongoing support and monthly follow-up offered by the CARE program is reducing the rate of conversion.

Further analysis of “false positive” subjects, who had not converted to psychosis at 1-year follow-up, revealed that the majority remained symptomatic, despite not having developed full-blown psychosis. It is possible that mood or anxiety symptoms may have “masqueraded” as subsyndromal psychotic symptoms in some participants, who, with appropriate treatment (both pharmacologic and psychosocial) experienced symptom resolution. Conversely, it is possible that mood stabilizers provided a neuroprotective effect in the at-risk group and perhaps prevented the onset of psychosis.

Our results thus demonstrate the heterogeneous presentation of individuals identified using current “prodromal” criteria and support the notion that those thereby identified as at risk may benefit from early intervention.31 Because this was not a controlled treatment study, and all subjects received symptom-based treatment according to the standard of care, it is not possible to assess whether one treatment was superior over another. Instead, it appears clear that “one size does not fit all” when it comes to treating individuals identified as at risk for psychosis.

The relatively low conversion rate, the heterogeneous nature of the at-risk population, the small sample size of the converted group, and the lack of specificity for schizophrenia in this sample clearly limit interpretation of risk factors for psychosis in general and the ability to analyze important issues like specificity of psychotic diagnosis (affective disorder versus schizophrenia). Therefore, these findings need to be replicated in a larger sample with sufficient power to adequately interpret the results. Since clinicians use the information generated by studies such as this to assist with early identification and treatment of at-risk youth, it is essential that results be reported accurately and not overinterpreted.

Clinical and Ethical Implications

In other branches of medicine, if doctors can identify persons who are at high risk for developing a disease, they may recommend prophylactic medication to prevent the disease. The Framingham Heart Study identified risk factors for coronary heart disease and developed an algorithm based on demographic variables (age, gender, smoking), physiological measures (systolic blood pressure, electrocardiogram [ECG] criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy) and metabolic indices (total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein [HDL] cholesterol, diabetes mellitus) to help guide intervention efforts. A number of guidelines,47 including those derived from the Framingham study, have been developed that weigh risks (number of risk factors present) and potential benefit from primary prevention efforts targeting specific risk factors such as high blood pressure and/or serum cholesterol. In general, the guidelines state that risk factors are multiplicative; risk is highest in subjects with several risk factors; and specific drug therapy should only be initiated if absolute risk exceeds a certain threshold.

Similarly, when an individual presents with characteristics of prodromal schizophrenia, the clinician has to consider intervention by assessing demographic, clinical, and familial risk for the illness. In making this decision, several clinical and ethical dilemmas arise when treating the adolescent and young adult population. Because the recipients of the treatment are often minors (hence lacking legal competency and possibly lacking psychological capacity to consent),48 the physician must take on an active role in guiding treatment. The treatments are expensive and have newly discovered side effects (eg, weight gain and metabolic syndrome associated with antipsychotics)49 and potential risks (eg, higher rate of suicidal ideation reported with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors)50. The probability of actually developing schizophrenia in any individual is unknown (but may be extrapolated from some knowledge of the group), and it is likely that at least 50% will not develop schizophrenia. Optimal treatment therefore requires consideration of both clinical and ethical dimensions of decision making.

The ethical issues, clearly and thoroughly articulated recently by Corcoran, Malaspina, and Hercher,14 are multifaceted. They stem from tensions among basic ethical principles, such as balancing patient autonomy and provision of information necessary for informed consent, with beneficent concerns related to labeling a young person as “at risk” for psychosis. For instance, many are concerned about the potential for stigmatization, loss of confidentiality, and, theoretically at least, the potential for consequent uninsurability or discrimination in school or workplace settings.14 Moreover, given the ethical gray zones surrounding adolescent decision making,51 the issues become even more complex: Who should be given information? How should this information be provided? What special precautions should be taken? Furthermore, these cases go beyond simple diagnostic difficulty, as clinicians must try to mingle their knowledge base of prodromal schizophrenia, their attention to ethical and legal standards of informed consent, their sensitivity to cultural considerations (eg, with respect to values and preferences around psychoeducation and decision making), and their psychiatric professionalism into a cohesive and highly ethical diagnostic and treatment plan.

This is not an easy proposition, and schizophrenia researchers, in turn, must be wary of proposing easy solutions or simple treatment recipes. As schizophrenia investigators have turned their attention in the last decade not only to the treatment of established cases of schizophrenia but also to the earlier identification of potential cases of schizophrenia, consideration of prophylactic treatment has become a reality. Pharmacologic studies have been undertaken with initially favorable results.25,52 Given the excitement generated by the prospect of intervening early in the course of schizophrenia, many clinicians are more willing to consider early treatment with agents such as antipsychotics in the hope of preventing a psychotic break. Recent marketing by the pharmaceutical industry has advocated the use of atypical antipsychotics for a variety of nonpsychotic conditions such as mood or anxiety disorders, and clinicians may be more willing to use an antipsychotic agent to target any of the symptom dimensions. Based on the results of our study, however, we suggest a more conservative approach to addressing treatment in this heterogeneous sample of help-seeking individuals. Importantly, this approach cannot be characterized as “one size fits all.” Instead, similar to treatment guidelines for other major disorders in medicine, it must be tailored to the individual's presenting symptoms and risk factors (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment Recommendations

| Full diagnostic assessment, including differential diagnosis, by a doctoral-level clinician. | Presenting symptoms could be an emerging anxiety, affective, or substance abuse disorder. Other metabolic, endocrine, or neurological causes need to be ruled out. |

| Psychoeducation regarding the presenting symptoms and risk of ongoing substance abuse. | Education for the patient and family regarding the potential risks and symptoms to watch out for should be presented in a reassuring and nonstigmatizing manner. The use of substances can cloud the clinical picture and may provide a second “hit,” triggering a vulnerable person to become psychotic. |

| Psychosocial treatment, including crisis intervention, reduction of stress and ongoing support related to family, peer, or school/work problems. Also consider Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) to target specific symptoms. | Observed symptoms may be transient and in part related to developmental challenges in adolescence and young adulthood. Supportive approaches that include ongoing assessment of symptoms and stressors will help to reduce the intensity of symptoms. |

| Pharmacologic intervention should target the presenting symptoms. | Keep in mind the differential diagnosis when considering the addition of medication. Consider the use of mood stabilizers (ie, lithium or valproic acid), antidepressants, or short-term use of benzodiazepines prior to the use of antipsychotic agents if mood or anxiety disorders are prominent. Consider a brief trial with antipsychotics to target worsening subsyndromal psychotic symptoms if the above intervention is not effective. Long-term use of antipsychotics should be reserved for established diagnoses of DSM-IV psychotic disorders. |

Limitations in Current Research

An important aim of research into the schizophrenia prodrome should be to identify which combination of various risk factors can best identify individuals who are presently free of the overt disease but who would, in the future, develop the disease. Ideally, the methodology would be sensitive (pick up most of the potential cases) and specific (pick up cases that would develop schizophrenia, rather than other problems). To date, prodromal research has generated mixed results using the current model that relies on demographic variables, symptoms, and family history. The reported sensitivity and specificity of prodromal criteria are relatively high in some but not all reports, suggesting that we now have some capacity, albeit imperfect, to identify future cases. Of the future cases that are accurately predicted, only a portion goes on to develop schizophrenia rather than affective psychosis. Our current methodology is thus somewhat specific to psychosis but not necessarily schizophrenia.

One possible means of increasing the predictive power of current methods is to identify brain-based neurobiological markers that tap into vulnerability for psychosis and specifically schizophrenia.7,39,53 A number of potential endophenotypes for schizophrenia, including psychophysiological, neurocognitive, and neuroimaging measures, have shown promising preliminary results in predicting later psychosis.10,12,13,54–58 Additionally, with the rapid advances in the field of genetics, it may also be possible to identify genetic markers that can assist in predicting subgroups at risk for schizophrenia,13 much like the identified genes for specific types of breast cancer59 or early onset Alzheimer disease.60

One difficulty in the current state of prodromal schizophrenia research is that the sample sizes are often too small, with insufficient power, to reliably answer questions and draw conclusions from the data. Underpowered research studies raise ethical issues in and of themselves.61 Asking individuals to enroll in research with unclear risks and benefits also must be evaluated in the context of prodromal research. Potential risk factors for conversion can be identified in the individual studies, but it is more difficult to assess risk for subgroups within the sample, such as affective versus schizophreniform psychosis.

Suggested Directions for Future Research

Large-scale collaborative efforts with sufficient power to truly answer these important questions are clearly needed. Only with sufficient power to predict risk will it be possible to develop an algorithm (similar to the Framingham Heart Study) for determining how many, what type, and at what threshold risk factors require intervention. Once an algorithm for risk has been established, then prophylactic or preventive treatment can more systematically be administered. Further basic science research that investigates the neuroprotective effect of various agents such as omega fatty acids, lithium, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, antipsychotics, or glycine compounds may direct clinical researchers toward reasonable agents to use prophylactically in an at-risk population.17 Additionally, translational studies utilizing neurodevelopmental models and similar neurobiological methods may help to further specify treatments that might be indicated for subgroups with physiological impairments or functional brain changes.

Clinical studies of potential protective effects of atypical antipsychotics in first-episode schizophrenia represent an important direction for the field. Nonetheless, large-scale studies of antipsychotics in “prodromal schizophrenia” samples are premature, given the lack of specificity and the heterogeneous nature of the samples. It is also essential that researchers present results of ongoing trials in prodromal and first-episode samples in an accurate and contextually appropriate manner.62 Ethical standards must be maintained as the possibility of pharmaceutical interventions are explored.63 Careful planning before the trial begins can reduce the chances of biased results and erroneously negative results.31,64 Positive results in such trials are likely to have a large influence on the practice of clinicians who work with at-risk populations and will no doubt affect pharmaceutical marketing. Data from properly executed trials should be made available, including negative results that are often not reported and receive less interest from authors, editors, and sponsors than positive findings.64

Conclusions

The study of the schizophrenia prodrome offers the potential for early intervention and possible prevention of the illness, but the research remains challenging on multiple dimensions. The population at risk for schizophrenia that is identified based on established criteria is help-seeking and presents a heterogeneous clinical picture. Current criteria, based on demographic and clinical features, are not yet sensitive enough to reliably predict future psychosis, nor are we able to predict future schizophrenia versus other Axis I disorders.

Clinical and research implications of this field of research intersect in several ways with ethical considerations. First, the research has not reached a point where it can optimally inform clinicians faced with these complex patients. We have stressed that a “one size fits all” approach is not warranted. Instead, clinicians must still rely on a detailed assessment that includes knowledge of the intricacies of a differential diagnosis and longitudinal follow-up to determine the best course of treatment. Careful and sensitive psychoeducation, particularly with regard to the effects of substance use, is also vital.

As the promise of the Human Genome Project and other important large-scale genomic research projects is finally being fulfilled, some predict that these advances will enable clinicians, in the not too distant future, to pinpoint with a high degree of accuracy those people who are at very high risk for the development of neuropsychiatric disorders. Moreover, research on gene expression and effects on functioning and behavior may eventually allow clinicians to truly individualize treatments based on a person's neurobiological characteristics as determined by sensitive genetic tests. New ethical issues—some of which will certainly overlap with those described previously in the literature—will continue to emerge as this exciting research moves forward. Until that time, however, as the work presented in this article helps to demonstrate, consideration of the ethical implications of cutting-edge predictive psychiatric genetic and diagnostic research must take into account the variability in the accuracy of current diagnostic and predictive techniques, in order to avoid inappropriate stigmatization, inaccurate identification of risk patterns, potentially unwarranted treatment, and other unintended consequences.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health MH60720, Cognitive Assessment and Risk Evaluation (CARE). The authors wish to thank Karin Kristensen for her help in assessment and ongoing discussion of clinical issues and Kathleen Shafer, Iliana Marks, and Katherine Seeber for their technical and organizational assistance.

References

- 1.Addington J, Van Mastrigt S, Addington D. Duration of untreated psychosis: impact on 2-year outcome. Psychol Med. 2004;34(2):277–284. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lieberman JA. Is schizophrenia a neurodegenerative disorder? a clinical and neurobiological perspective. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46(6):729–739. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yung AR, McGorry PD. The initial prodrome in psychosis: descriptive and qualitative aspects. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1996;30(5):587–599. doi: 10.3109/00048679609062654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, et al. Psychosis prediction: 12-month follow up of a high-risk (“prodromal”) group. Schizophr Res. 2003;60(1):21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klosterkotter J, Hellmich M, Steinmeyer EM, Schultze-Lutter F. Diagnosing schizophrenia in the initial prodromal phase. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(2):158–164. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.2.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larsen TK, Friis S, Haahr U, et al. Early detection and intervention in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;103(5):323–334. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cadenhead KS. Vulnerability markers in the schizophrenia spectrum: implications for phenomenology, genetics, and the identification of the schizophrenia prodrome. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2002;25(4):837–853. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(02)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cornblatt BA. The New York high risk project to the Hillside recognition and prevention (RAP) program. Am J Med Genet. 2002;114(8):956–966. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.10520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, et al. Prospective diagnosis of the initial prodrome for schizophrenia based on the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes: preliminary evidence of interrater reliability and predictive validity. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(5):863–865. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myles-Worsley M, Ord L, Blailes F, Ngiralmau H, Freedman R. P50 sensory gating in adolescents from a Pacific Island isolate with elevated risk for schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55(7):663–667. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perkins DO. Evaluating and treating the prodromal stage of schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2004;6(4):289–295. doi: 10.1007/s11920-004-0079-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hambrecht M, Lammertink M, Klosterkotter J, Matuschek E, Pukrop R. Subjective and objective neuropsychological abnormalities in a psychosis prodrome clinic. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2002;43:s30–37. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.43.s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cannon TD, van Erp TG, Bearden CE, et al. Early and late neurodevelopmental influences in the prodrome to schizophrenia: contributions of genes, environment, and their interactions. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(4):653–669. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corcoran C, Malaspina D, Hercher L. Prodromal interventions for schizophrenia vulnerability: the risks of being “at risk.”. Schizophr Res. 2005;73:173–184. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cornblatt BA, Lencz T, Kane JM. Treatment of the schizophrenia prodrome: is it presently ethical? Schizophr Res. 2001;51(1):31–38. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00236-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGlashan TH. Psychosis treatment prior to psychosis onset: ethical issues. Schizophr Res. 2001;51(1):47–54. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00238-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGorry PD, Yung A, Phillips L. Ethics and early intervention in psychosis: keeping up the pace and staying in step. Schizophr Res. 2001;51(1):17–29. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00235-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corcoran C, Davidson L, Sills-Shahar R, et al. A qualitative research study of the evolution of symptoms in individuals identified as prodromal to psychosis. Psychiatr Q. 2003;74(4):313–332. doi: 10.1023/a:1026083309607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maier W, Cornblatt BA, Merikangas KR. Transition to schizophrenia and related disorders: toward a taxonomy of risk. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(4):693–701. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yung A. Two-year follow up of UHR individuals at the PACE clinic. Schizophr Res. 2004;70(suppl 1):43. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skeate A, Patterson P, Birchwood M. Transition to psychosis in a high-risk sample: the experience of ED:IT, Birmingham, UK. Schizophrenia Res. 2004;70(suppl 1):44. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGlashan T, Vaglum P, Friis S, et al. Early detection and intervention in first episode psychosis: empirical update of the TIPS and PRIME projects. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31(2):496. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lencz T, Smith CW, Auther AM, Correll CU, Cornblatt BA. The assessment of “prodromal schizophrenia”: unresolved issues and future directions. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(4):717–728. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carr V, Halpin S, Lau N, O'Brien S, Beckmann J, Lewin T. A risk factor screening and assessment protocol for schizophrenia and related psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34(suppl):S170–180. doi: 10.1080/000486700240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGorry PD, Yung AR, Phillips LJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of interventions designed to reduce the risk of progression to first-episode psychosis in a clinical sample with subthreshold symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(10):921–928. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yung AR, McGorry PD, McFarlane CA, Jackson HJ, Patton GC, Rakkar A. Monitoring and care of young people at incipient risk of psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):283–303. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yung AR, Phillips LJ, McGorry PD, et al. Prediction of psychosis. a step towards indicated prevention of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1998;172(33):14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, McGorry PD. Risk factors for psychosis in an ultra high-risk group: psychopathology and clinical features. Schizophr Res. 2004;67:131–142. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cornblatt BA, Lencz T, Smith CW, et al. The schizophrenia prodrome revisited: a neurodevelopmental perspective. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(4):633–651. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mason O, Startup M, Halpin S, Schall U, Conrad A, Carr V. Risk factors for transition to first episode psychosis among individuals with “at-risk mental states”. Schizophr Res. 2004;71:227–237. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schaffner KF, McGorry PD. Preventing severe mental illnesses: new prospects and ethical challenges. Schizophr Res. 2001;51(1):3–15. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kane JM, Krystal J, Correll CU. Treatment models and designs for intervention research during the psychotic prodrome. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(4):747–756. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marshall M, Lockwood A. Early intervention for psychosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(issue 2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bramble D. Annotation: the use of psychotropic medications in children: a British view. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2003;44(2):169–179. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyons JS, MacIntyre JC, Lee ME, Carpinello S, Zuber MP, Fazio ML. Psychotropic medications prescribing patterns for children and adolescents in New York's public mental health system. Community Ment Health J. 2004;40(2):101–118. doi: 10.1023/b:comh.0000022731.65054.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barbui C, Ciuna A, Nose M, et al. Off-label and non-classical prescriptions of antipsychotic agents in ordinary in-patient practice. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109(4):275–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2003.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kogut SJ, Yam F, Dufresne R. Prescribing of antipsychotic medication in a Medicaid population: use of polytherapy and off-label dosages. J Manag Care Pharm. 2005;11(1):17–24. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2005.11.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rawal PH, Lyons JS, MacIntyre JC, II, Hunter JC. Regional variation and clinical indicators of antipsychotic use in residential treatment: a four-state comparison. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2004;31(2):178–188. doi: 10.1007/BF02287380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seeber K, Cadenhead KS. How does studying schizotypal personality disorder inform us about the prodrome of schizophrenia? Curr Psychiatry Repr. 2005;7:41–50. doi: 10.1007/s11920-005-0024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders—Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Ryan N. Kiddie-SADS-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL, Version 1.0) Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, School of Medicine; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SANS) Iowa City: University of Iowa; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) Iowa City: University of Iowa; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. The Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV) Iowa City: Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Winokur G. The family history method using diagnostic criteria: reliability and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1977;34(10):1229–1235. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1977.01770220111013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Broedl UC, Geiss HC, Parhofer KG. Comparison of current guidelines for primary prevention of coronary heart disease: risk assessment and lipid-lowering therapy. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(3):190–195. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tan JO, Fegert JM. Capacity and competence in child and adolescent psychiatry. Health Care Anal. 2004;12(4):285–294. doi: 10.1007/s10728-004-6636-9. discussion 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Casey DE. Metabolic issues and cardiovascular disease in patients with psychiatric disorders. Am J Med. 2005;118(suppl 2):15S–22S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whittington CJ, Kendall T, Fonagy P, Cottrell D, Cotgrove A, Boddington E. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in childhood depression: systematic review of published versus unpublished data. Lancet. 2004;363:1341–1345. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miller VA, Drotar D, Kodish E. Children's competence for assent and consent: a review of empirical findings. Ethics Behav. 2004;14(3):255–295. doi: 10.1207/s15327019eb1403_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Woods SW, Breier A, Zipursky RB, et al. Randomized trial of olanzapine versus placebo in the symptomatic acute treatment of the schizophrenic prodrome. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(4):453–464. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00321-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cadenhead KS, Light GA, Shafer K, Braff DL. P50 suppression in individuals at risk for schizophrenia: the convergence of clinical, familial and vulnerability marker risk assessment. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(12):1504–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Copolov D, Velakoulis D, McGorry P, et al. Neurobiological findings in early phase schizophrenia. Brain Res Rev. 2000;31:157–165. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hawkins KA, Addington J, Keefe RS, et al. Neuropsychological status of subjects at high risk for a first episode of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2004;67:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Knowles L, Sharma T. Identifying vulnerability markers in prodromal patients: a step in the right direction for schizophrenia prevention. CNS Spectr. 2004;9(8):595–602. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900002765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seidman LJ, Pantelis C, Keshavan MS, et al. A review and new report of medial temporal lobe dysfunction as a vulnerability indicator for schizophrenia: a magnetic resonance imaging morphometric family study of the parahippocampal gyrus. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(4):803–830. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Auther AM, Lencz T, Smith CW, Bowie CR, Cornblatt BA. Overview of the first annual workshop on the schizophrenia prodrome. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(4):625–631. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bansal A, Critchfield GC, Frank TS, et al. The predictive value of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation testing. Genet Test. 2000;4(1):45–48. doi: 10.1089/109065700316462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blacker D, Tanzi RE. The genetics of Alzheimer disease: current status and future prospects. Arch Neurol. 1998;55(3):294–296. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.3.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Emanuel EJ, Wendler D, Grady C. What makes clinical research ethical? JAMA. 2000;283(20):2701–2711. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.20.2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marco CA, Larkin GL. Research ethics: ethical issues of data reporting and the quest for authenticity. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(6):691–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb02049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beran RG. Legal and ethical obligations to conduct a clinical drug trial in Australia as an investigator initiated and sponsored study for an overseas pharmaceutical company. Med Law. 2004;23(4):913–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cleophas RC, Cleophas TJ. Is selective reporting of clinical research unethical as well as unscientific? Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999;37(1):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McGlashan TH, Miller TJ, Woods SW. Pre-onset detection and intervention research in schizophrenia psychoses: current estimates of benefit and risk. Schizophr Bull. 2001;27(4):563–570. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miller TJ, Rosen JL, Andrea JD, Woods SW, McGlashan TH. Outcome of prodromal syndromes: SIPS predictive validity. Schizophr Res. 2004;70:44. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cornblatt B, Lencz T, Smith C, Auther A, Nakayama E, McLaughlin D. Neurocognitive risk factors identified in the New York Recognition and Prevention (RAP) Program. Schizophr Res. 2004;70:50. [Google Scholar]