Abstract

Because the decision-making capacity of individuals with schizophrenia may fluctuate, additional protections for such persons who enroll in long-term research studies may be needed. For the NIMH-sponsored Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia study, new procedures were developed to help ensure an objective assessment of a patient's continued participation in the study if decision-making capacity lapsed. Each research participant had a subject advocate who could recommend that the subject be withdrawn from the study if capacity lapsed and continued participation was not in the subject's best interest. The main goals of the procedures were to protect the interests of subjects and to prevent unnecessary dropouts. We surveyed research personnel regarding the effectiveness and implementation of the procedures. Responses were received from 73 personnel at 49 research sites, representing 70% of possible respondents and 91% of eligible sites. A majority of respondents were favorably disposed toward subject advocates, and though most reported that the procedures had no discernible effect on study recruitment, subject autonomy, or subject retention, for those who reported an impact, it was almost always positive. Some respondents reported that the procedures helped by engaging family members and promoting a positive view of schizophrenia research. A majority thought that similar arrangements would be useful in future longitudinal research studies. Nonspecific benefits included good public relations and engagement of family members. Improved training regarding the procedures may be needed to achieve specific goals of enhanced patient autonomy and retention in the study.

Keywords: human-subject protections, longitudinal research, decision-making capacity, schizophrenia

An adequate level of decision-making capacity is necessary to provide valid consent for participation in research projects. For time-limited studies that will be completed shortly after consent is obtained (e.g., a single blood draw or diagnostic test), adequate capacity at the time that consent is given is all that is necessary. But for longitudinal studies involving participants with considerable potential for fluctuating capacity, a method to address diminished decision-making capacity in research participants is desirable.1,2 One of the purposes of informed consent is to facilitate research participants' ability to protect their own interests.3 If their underlying condition worsens as a project proceeds, or if the study leads to unexpected risks or discomforts, research participants have the right to stop their participation or to renegotiate the terms of their involvement. Without the capacity to recognize such changes in circumstances, participants may lose the ability to protect their interests.

Although investigators may commonly withdraw subjects when they believe that continued participation in a research project would not be in their interests, investigators and subjects may have conflicting interests when it comes to decisions about continuing in a study, making it hard for the former to act objectively. In this context, we developed a mechanism designed to promote the independent consideration of a subject's interests.4

As we have discussed previously, the development of a way to ensure that a research participant's interests are considered objectively has been hampered by the ambiguous legal climate surrounding the assignment of decision-making responsibility to third parties in research settings.4,5 Few states now clearly permit surrogates to make decisions about participation in research. In this article, we describe “subject advocate” procedures that were developed to help protect the interests of research subjects in a large, multiphase clinical trial. The procedures were an attempt to use a third party in order to provide independent input into the continued participation of a research participant if the participant's decision-making capacity lapsed. The subject advocate, as defined in the CATIE study, provided protection in a manner consistent with existing law. We present the results of an evaluation of these procedures that was intended to determine the effectiveness of the procedures in achieving their goals and to identify possible problems and improvements.

METHOD

The CATIE Schizophrenia Study

In the National Institute of Mental Health–sponsored Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia study, almost 1500 individuals with schizophrenia were enrolled in a study with a goal that required the long-term participation of subjects.6 The goal of the study was to determine the comparative long-term effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in “real-world” settings. Potential participants were screened for decision-making capacity using the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool–Clinical Research (MacCAT-CR) prior to randomization.7

CATIE subjects were asked to participate for 18 or more months so that longer-term outcomes could be assessed. In order to mimic usual treatment conditions, the protocol allowed participants who discontinued study treatments to receive subsequent study treatments. Upon enrollment, all participants were randomly assigned to double-blinded treatment with one of five antipsychotic drugs. If a participant discontinued the assigned drug for any reason, he or she entered a second phase of the study, in which a second FDA-approved antipsychotic drug was randomly assigned. If a participant discontinued the second drug, the participant entered a third phase, in which one of eight drug-treatment strategies was selected. One of the study's aims was to evaluate serial treatment strategies.

The Subject Advocate Role in CATIE

In some instances, it was expected that treatment discontinuation would be accompanied by diminished decision-making capacity. The role of “subject advocate” was developed as a practical way to protect subjects while helping the study achieve its scientific goals. Each potential study subject designated a subject advocate to participate in the initial consent discussion and to assist with decision making. If a family member or friend could not serve as subject advocate, a person not otherwise involved in the research (e.g., a social worker or case manager) was selected to serve in this role.

The initial decision about enrollment in the study was made by the subject, who had to have adequate decision-making capacity to do so. Subsequently, if a subject's capacity lapsed to the point where the subject could no longer protect his or her own interests, consultation with the subject advocate was required. The subject advocate could then recommend that the participant be withdrawn from the study if the advocate determined that the original risk/benefit ratio that led the subject to consent to participation had changed substantially and adversely with regard to the subject's interests. However, the subject advocate could permit a subject whose decision-making capacity had lapsed to remain in the study if the risk/benefit ratio had not been significantly and unfavorably altered and if the subject continued to consent to participate.

The primary goal of the subject advocate was to ensure that a research participant's interests were protected in the context of a multiphase clinical trial involving participants with a significant potential for fluctuating decision-making capacity. An important secondary goal was to help the study achieve its aims, including the evaluation of the effectiveness of serial treatment strategies for “real-world” patients with schizophrenia, including those with fluctuating decision-making capacity. By being available to assess the subject's interests through the study's multiple phases, the subject advocate could ensure that subjects were protected and that the study's generalizability would be enhanced.

Training for the subject advocate procedures was conducted at an investigators' meeting before subject recruitment began. The training session was available online throughout the conduct of the study. In addition, a written description of the subject advocate procedures was provided to all study personnel in the trial's Study Reference Manual. Personnel at the research sites were instructed to provide a handout describing the purpose of the procedures to potential subjects and subject advocates.

Evaluation of the Subject Advocate Procedures

To evaluate the implementation of subject advocate procedures, we conducted an anonymous online survey of research personnel at CATIE research sites. We invited the site's principal investigator and a second member of each site's research staff who should have been familiar with the subject advocate procedures to complete the survey. No more than two individuals from a site were allowed to respond to the questionnaire. Respondents provided information about their role in the project and answered questions regarding their understanding of subject advocate procedures, their interactions with subject advocates, and their opinions regarding the value and success of the procedures. We also sought to understand how institutional review boards at the sites responded to the procedures and solicited the respondents' advice regarding how the procedures could be improved. Procedures were approved by the Biomedical IRB at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

We then conducted pen-and-paper surveys of a subset of subjects and subject advocates at the clinical research sites. When subjects completed or left the study, we asked them to complete a survey with questions regarding their understanding of subject advocate procedures and their opinions regarding the value and success of the procedures. Sites also asked the subject advocates of participants leaving the study to complete a similar survey. Procedures for this phase of the study were approved by the Biomedical IRB at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and by the IRB at each of the participating research sites.

In this evaluation, we had no a priori hypotheses. We present descriptive statistics that were used to help determine the effectiveness of the procedures in achieving their goals, to demonstrate how the procedures were perceived by individuals who implemented them and by others who participated in the study, and to identify any problems with the implementation of the procedures.

Results

We received valid responses from 73 research personnel representing 70% of the 104 surveys distributed. Twenty-two of the respondents were study principal investigators (PIs), 40 were study coordinators, four were study recruiters, and seven were other personnel. Responses were received from at least one person at 49 of the 54 (91%) sites that were sent surveys.

We first sought to determine how well study personnel understood the purpose of the subject advocate procedures. All respondents identified either protection of subjects or promotion of autonomy as a purpose of having a subject advocate, but only 27% understood that improved retention was a goal of the procedures.

All respondents understood that the subject advocate had to be contacted if a participant had impaired decision-making capacity. All study coordinators and 91% of study PIs understood that the subject advocate was supposed to be present or contacted at the time the participant consented to the study.

In practice, respondents also contacted subject advocates in other circumstances. Fifteen percent of respondents said it was helpful to contact subject advocates if the participant was upset with research staff, and 31% said this was helpful when the participant requested to leave the study. Forty-three percent of respondents reported that it was useful to contact subject advocates whenever participants changed study phases (i.e., required a change in antipsychotic medicines).

Eighty percent of responding sites reported that their IRB(s) accepted the subject advocate procedures as proposed without change. Two sites reported that their IRB required the subject advocate to be present at each phase change, and four sites did not allow other, non-research personnel at the site to serve as subject advocate—instead, only people not employed by the research institution could serve in this role. Two sites were not allowed to contact the subject advocates directly but instead had to have the research participant make this contact. Seventy percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that their IRB thought the subject advocate procedures were a good idea, 28% neither agreed nor disagreed, and only one respondent (1%) disagreed with the statement.

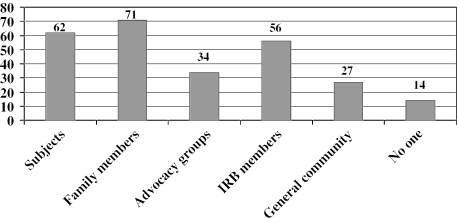

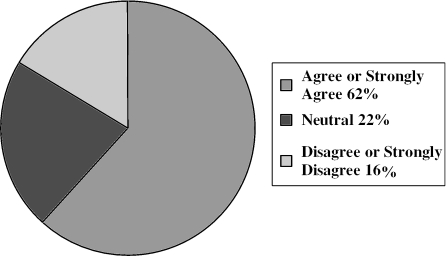

Table 1 shows how research personnel perceived the effectiveness of the subject advocate procedures in achieving their main goals. Sixty percent of respondents thought the procedures had no effect on retention of subjects in the study, while 38% thought they were helpful and one person (1%) thought they hindered retention. Regarding subject autonomy, 37% of respondents indicated that the subject advocate procedures had a very or somewhat positive effect on subjects' abilities to make their own decisions, while 58% thought there was no discernible effect and 5% thought there was a somewhat negative effect on subject autonomy. The table also shows that a majority of respondents agreed that the effort to obtain subject advocates was worthwhile and thought the procedures had no effect on subject recruitment. In addition, the table summarizes the several ways that respondents thought implementation of the subject advocate procedures could be improved. Figure 1 shows that respondents thought the procedures promoted a positive view of the CATIE study among a variety of constituencies. Figure 2 shows that considerably more than half of respondents (62%) agreed or strongly agreed that subject advocate procedures similar to those used in CATIE should be used in all future studies involving persons with schizophrenia. However, 11% of respondents disagreed with this, and 5% disagreed strongly. The remaining 22% were neutral.

Table 1.

Study Personnel Views of Subject Advocate Procedures (N = 73)

|

At your site, what effect did the subject advocate procedures have on enrolling people in the study (i.e., recruitment)? | ||

| Greatly helped | N = 2 | 3% |

| Somewhat helped | 12 | 16% |

| Had no discernible effect | 43 | 59% |

| Somewhat hindered | 16 | 22% |

| Greatly hindered |

0 |

0% |

|

At your site, what effect did the subject advocate procedures have on keeping subjects in the study (i.e., retention)? | ||

| Greatly helpful | 3 | 4% |

| Somewhat helpful | 25 | 34% |

| Had no discernible effect | 44 | 60% |

| Somewhat hindered | 1 | 1% |

| Greatly hindered |

0 |

0% |

|

At your site, what effect did the subject advocate procedures have on the subject's ability to make his or her own decisions (i.e., autonomy)? | ||

| Very positive effect | 2 | 3% |

| Somewhat positive effect | 25 | 34% |

| No discernible effect | 42 | 58% |

| Somewhat negative effect | 4 | 5% |

| Very negative effect |

0 |

0% |

|

Overall, the effort required to obtain a subject advocate for each subject was worthwhile. | ||

| Strongly agree | 16 | 22% |

| Agree | 33 | 45% |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 14 | 19% |

| Disagree | 10 | 14% |

| Strongly disagree |

0 |

0% |

|

Suggested improvements to subject advocate procedure implementation* | ||

| Additional training on SA procedures | 21 | 29% |

| Additional instructions about the SA procedures | 27 | 37% |

| Clearer indication of the subject advocate purpose | 35 | 48% |

| Clearer indication of times to contact the subject advocate | 33 | 45% |

| Clearer indication of frequency of subject/subject advocate meetings | 27 | 37% |

| Other | 7 | 10% |

Respondents could select all applicable responses. (total responses = 150)

Fig. 1.

Percentage of research personnel who endorsed the view that subject advocate procedures promoted a positive view of the CATIE study among subjects, family members, advocacy groups, IRB members, or the general community, or did not promote a positive view among anyone.

Fig. 2.

Subject advocate procedures similar to those used in the CATIE study should be used in all future studies involving persons with schizophrenia.

We asked all survey respondents to provide any comments they might have about the subject advocate procedures. The most common theme among the 31 comments provided concerned the difficulty of finding family members or friends to serve as subject advocate. Several respondents noted that many individuals in the study did not have anyone to designate as subject advocate, so site personnel had to identify someone to serve in this role. Several commented that having family members as subject advocate promoted more familial involvement, which was positive for the participant and the family member. There were mixed comments regarding non-family-member subject advocates. At one site, “several significant others” lost significance and had to be replaced. Case manager turnover at one site caused a similar problem. Sites that relied on non-research personnel at the site to serve as subject advocate noted scheduling difficulties. A site that used members of the local National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI) chapter noted that this promoted a positive view of research by the NAMI members. Good public relations were a consequence of the procedures noted by a few who commented.

Surveys of Subjects and Subject Advocates

The phase of the study involving surveys of subjects and subject advocates was implemented very late in the course of the study. A convenience sample of 41 subjects and 24 subject advocates provided responses at 10 sites. Subject advocates (42% were parents of subjects, 21% were friends or other relatives, 33% were clinicians whose patients or clients were enrolled in the study, and 4% were someone else designated by the site) had a positive view of their role. Seventy-six percent of advocates agreed or strongly agreed that the procedures allowed research participants greater freedom to make their own decisions. Seventy-nine percent agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that serving as subject advocate improved their opinion of schizophrenia research. No subject advocates who responded agreed that serving as advocate was a burden. Ninety-six percent agreed or strongly agreed that all schizophrenia research should include “someone like a CATIE subject advocate.”

Subject respondents also had a favorable view of the subject advocate mechanism. More than half of respondents (54%) agreed that having the subject advocate procedures positively influenced their decision to participate in the study. Thirty-two percent of respondents were neutral, 7% disagreed, and 7% did not respond.

On the other hand, some study participants thought the procedures interfered with their autonomy. Two people (5%) strongly agreed and three (7%) agreed with the statement “My subject advocate got in the way of my ability to make my own decisions.” Most respondents, however, disagreed (32%) or strongly disagreed (39%) with this statement; 5% were neutral.

Discussion

In this evaluation, we learned that subject advocate procedures had both intended and unintended consequences. Research personnel understood the purposes of subject advocate procedures, but some viewed the advocate's role as broader than intended. Most respondents thought the effort to obtain subject advocates was worthwhile. A majority felt that such procedures should be used in future longitudinal studies involving subjects with schizophrenia, although a few strongly disagreed with this.

It is less clear how successful the subject advocate procedures were in achieving the goals of helping to protect the rights of research participants whose decision-making capacity may have fluctuated, and of helping to retain such subjects in the longitudinal trial. A third of respondents thought the procedures aided retention in the study, but most felt there was no effect. Somewhat more than a third of respondents thought the procedures had a positive effect on subject autonomy, but most felt there was no discernible effect. On the other hand, almost no respondents discerned negative effects on subjects' rights or retention. Hence, although the presence of subject advocates had an impact on subjects at only a minority of sites, when they did have an effect, it was almost always a positive one.

Not all of the unintended consequences of the procedures were positive. Reports from some research personnel that they contacted subject advocates when subjects wanted to leave the study, and from some subjects that having a subject advocate interfered with their autonomy, suggest that better specification of the role of subject advocate was needed. A need for better training procedures was widely endorsed.

In addition, although sites rarely reported that having to find subject advocates interfered with study recruitment, any such interference could have had an adverse effect on study generalizability. And though most research personnel thought the effort to get subject advocates was worthwhile, we cannot demonstrate clearly that the benefits of the CATIE procedures outweighed the costs of the efforts.

A mechanism such as the CATIE subject advocate may be useful in future longitudinal research involving individuals with the potential for fluctuating decision-making capacity. Precisely where such problems are most likely to exist remains to be determined, and the extent of fluctuation may be less in patients with schizophrenia than has been thought.8 But this category might include subjects with other psychiatric disorders, dementias, and other medical disorders that affect brain functioning. If researchers use such a mechanism, research personnel will need careful training regarding procedures to make sure that the advocate's role is not used in unintended ways. Even if subject advocates directly impact the research participation of only a minority of subjects, they may have a positive impact by reassuring subjects, family members, IRB members, and other interested persons that subjects' interests will be protected.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Greenwall Foundation and NIH Research Grant #1 K23 MH67002-01A1 funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and the Office of the Director, Office of Behavioral and Social Research (OD/OBSSR).

This article was based on results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness project, supported with federal funds from the National Institute of Mental Health under contract NO1 MH90001.

The project was carried out by principal investigators from the University of North Carolina, Duke University, the University of Southern California, the University of Rochester, and Yale University in association with Quintiles, Inc.; the program staff of the Division of Interventions and Services Research of the NIMH; and investigators from 56 sites in the United States (CATIE Study Investigators Group). AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, L.P.; Eli Lilly and Company; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; Pfizer Inc.; and Zenith Goldline Pharmaceuticals, Inc. provided medications for the studies. This work was also supported by the Foundation of Hope of Raleigh, NC. We also thank Emily Bredthauer, MSW, for her excellent assistance on this project.

Appendix

The CATIE Study Investigators Group includes Lawrence Adler, MD, Clinical Insights; Mohammed Bari, MD, Synergy Clinical Research; Irving Belz, MD, Tri-County/ MHMR; Raymond Bland, MD, SIU School of Medicine; Thomas Blocher, MD, MHMRA of Harris County; Brent Bolyard, MD, Cox North Hospital; Alan Buffenstein, MD, The Queen's Medical Center; John Burruss, MD, Baylor College of Medicine; Matthew Byerly, MD, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas; Jose Canive, MD, Albuquerque VA Medical Center; Stanley Caroff, MD, University of Pennsylvania and Philadelphia VA Medical Center; Charles Casat, MD, Behavioral Health Center; Eugenio Chavez-Rice, MD, El Paso Community MHMR Center; John Csernansky, MD, Washington University School of Medicine; Pedro Delgado, MD, University Hospitals of Cleveland; Richard Douyon, MD, VA Medical Center; Cyril D'Souza, MD, Connecticut Mental Health Center; Ira Glick, MD, Stanford University School of Medicine; Donald Goff, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital; Silvia Gratz, MD, Eastern Pennsylvania Psychiatric Institute; George T. Grossberg, MD, St. Louis University School of Medicine-Wohl Institute; Mahlon Hale, MD, New Britain General Hospital; Mark Hamner, MD, Medical University of South Carolina and Veterans Affairs Medical Center; Richard Jaffe, MD, Belmont Center for Comprehensive Treatment; Dilip Jeste, MD, University of California-San Diego, VA Medical Center; Anita Kablinger, MD, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center; Ahsan Khan, MD, Psychiatric Research Institute; Steven Lamberti, MD, University of Rochester Medical Center; Michael T. Levy, MD, PC, Staten Island University Hospital; Jeffrey Lieberman, MD, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Gerald Maguire, MD, University of California-Irvine; Theo Manschreck, MD, Corrigan Mental Health Center; Joseph McEvoy, MD, Duke University Medical Center; Mark McGee, MD, Appalachian Psychiatric Healthcare System; Herbert Meltzer, MD, Vanderbilt University Medical Center; Alexander Miller, MD, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio; Del D. Miller, MD, University of Iowa; Henry Nasrallah, MD, University of Cincinnati Medical Center; Charles Nemeroff, MD, PhD, Emory University School of Medicine; Stephen Olson, MD, University of Minnesota Medical School; Gregory F. Oxenkrug, MD, St. Elizabeth's Medical Center; Jayendra Patel, MD, University of Massachusetts Health Care; Frederick Reimherr, MD, University of Utah Medical Center; Silvana Riggio, MD, Mount Sinai Medical Center-Bronx VA Medical Center; Samuel Risch, MD, University of California-San Francisco; Bruce Saltz, MD, Henderson Mental Health Center; Thomas Simpatico, MD, Northwestern University; George Simpson, MD, University of Southern California Medical Center; Michael Smith, MD, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center; Roger Sommi, PharmD, University of Missouri; Richard M. Steinbook, MD, University of Miami School of Medicine; Michael Stevens, MD, Valley Mental Health; Andre Tapp, MD, VA Puget Sound Health Care System; Rafael Torres, MD, University of Mississippi; Peter Weiden, MD, SUNY Downstate Medical Center; and James Wolberg, MD, Mount Sinai Medical Center.

References

- 1.Appelbaum PS. Drug-free research in schizophrenia: an overview of the controversy. IRB: A Review of Human Subjects Research. 1996;18:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Posever T, Chelmow T. Informed consent for research in schizophrenia: an alternative for special studies. IRB: A Review of Human Subjects Research. 2001;23:10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berg JW, Appelbaum PS, Lidz CW, Parker L. Informed Consent: Legal Theory and Clinical Practice. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stroup S, Appelbaum P. The subject advocate: protecting the interests of participants with fluctuating decisionmaking capacity. IRB. 2003;25(3):9–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SY, Appelbaum PS, Jeste DV, Olin JT. Proxy and surrogate consent in geriatric neuropsychiatric research: update and recommendations. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:797–806. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Byerly MJ, Glick ID, Canive JM, et al. The National Institute of Mental Health Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) project: schizophrenia trial design and protocol development. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:15–31. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Professional Resource Press, Sarasota, FL; 2001. The MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (MacCAT-CR) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moser DJ, Reese RL, Schultz SK, Benjamin ML, Arndt S, Fleming FW, Andreasen NC. Informed consent in medication-free schizophrenia research. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1209–1211. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]