Abstract

The definition and assessment of adherence vary considerably across studies. Increasing consensus regarding these issues is necessary to improve our understanding of adherence and the development of more effective treatments. We review the adherence literature over the past 3 decades to explore the definitions and assessment of adherence to oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia patients. A total of 161 articles were identified through MEDLINE and PsycINFO searches. The most common method used to assess adherence was the report of the patient. Subjective and indirect methods including self-report, provider report, significant other report, and chart review were the only methods used to assess adherence in over 77% (124/161) of studies reviewed. Direct or objective measures including pill count, blood or urine analysis, electronic monitoring, and electronic refill records were used in less than 23% (37/161) of studies. Even in studies utilizing the same methodology to assess adherence, definitions of an adherent subject varied broadly from agreeing to take any medication to taking at least 90% of medication as prescribed. We make suggestions for consensus development, including the use of recommended terminology for different subject samples, the increased use of objective or direct measures, and the inclusion in all studies of an estimate of the percentage of medication taken as prescribed in an effort to increase comparability among studies. The suggestions are designed to advance the field with respect to both understanding predictors of adherence and developing interventions to improve adherence to oral antipsychotic medications.

Keywords: adherence, oral antipsychotics, schizophrenia

Introduction

There is no question that adherence to medication is essential to maximizing outcomes for individuals with schizophrenia.1,2 While adherence is poor across a wide variety of physical and psychiatric conditions,1,3–5 the consequences of poor medication adherence can be devastating in schizophrenia, where the personal and societal costs of relapse are very high.1,2 Although we continue to develop new antipsychotic and adjunctive treatments with broader efficacy and improved side-effect profiles, levels of adherence remain alarmingly low.1,3

For decades, researchers have worked to explain the causes of poor adherence and to develop interventions.6–8 Unfortunately, there has been remarkably little agreement regarding the definition of adherence or how it is best measured. Medication adherence is often defined as “the extent to which a person's behavior coincides with medical … advice.”5(p2) However, different operational definitions and different assessment methods identify different subgroups of patients. If the same patient can be identified as adherent in one study and nonadherent in the next, how are we to combine information across studies? If we continue to proceed as if we are speaking about the same thing when we use the term “adherence,” our efforts to understand and improve it are likely to remain largely unsuccessful. Changing our terms from “noncompliance” to “adherence” to “concordance” has served to promote the idea that medication treatment should be a collaborative effort between doctor and patient, but it has done little to address the fundamental methodological problems in adherence research. An agreed-upon set of definitions and a better understanding of the measurement problems and how to address them are necessary if we are going to unravel the complex nature of adherence and intervene effectively in schizophrenia. With these goals in mind, we review the literature on adherence to oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia patients over the past 3 decades.

METHOD

We searched the literature published between 1970 and February 2006 using both MEDLINE and PsycINFO for articles containing the terms “adherence,” “concordance.” or “compliance” in combination with “schizophrenia.” In addition, we utilized the reference sections of review articles to identify articles we may have missed using these search terms. We eliminated case studies, articles that did not include at least 1 measure of medication adherence, articles examining only or primarily depot medications, studies involving mainly inpatients who were administered medication during the time adherence was assessed, studies using dropout from a clinical drug trial as the primary measure of adherence, and review articles. We identified a total of 161 articles. A minimum of 2 investigators read all studies and agreed that the assessment of adherence for each study fit into 1 or more of the following discrete categories: self-report, significant other report, treatment provider report, chart review, pill count, electronic refill records, electronic monitoring, blood or urine levels, urine level of tracer substances, and ability to take medication. A priori we defined self-report, provider report (physician, nurse, or caseworker), and chart review as more subjective/indirect assessments of adherence, and pill counts, electronic monitoring, blood or urine sampling, and electronic refill records as either more objective or more direct measures. Chart review was not included as a direct/objective measure due to the heavy reliance on chart information in the report of the patient and opinion of the treatment provider. In addition, each author made a determination as to whether the article represented a specific adherence study. An investigation was classified as an adherence study if the goal were to identify predictors of adherence to oral medication, to examine relationships between adherence and other variables, to investigate the assessment of medication adherence, or to examine the effects of a treatment specifically designed to improve medication adherence. Using these criteria, studies examining the effects of family therapy on outcomes and those examining reasons for relapse were not classified specifically as adherence studies.

Results

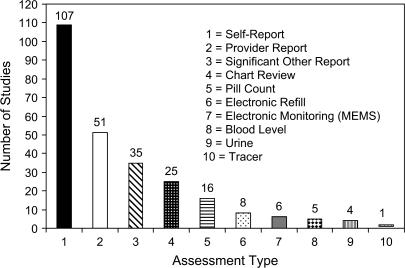

Table 1 lists the identified studies, the number of subjects, the methods of assessing adherence, and the criteria used to define adherence. Of 161 studies that were identified, 93 were classified as specifically adherence studies, and 68 were classified as general studies that included a measure of adherence to oral antipsychotic medication. The most common method used to assess adherence in both general and adherence studies was the report of the patient. Self-report was utilized alone or in combination with other methods a total of 107 times in 161 studies. Moreover, 25% (17/68) of general studies and over 36% (34/93) of all studies that specifically examined adherence to medication used self-report as the sole assessment of medication adherence. Self-report methodologies themselves differed greatly among studies and included ad hoc measures, interview (unspecified), semistructured interviews (unspecified), and semistructured interviews using the Rating of Medication Influences (ROMI),9 Treatment Compliance Interview (TCI),9 Drug Attitude Inventory (DAI),10 the medication compliance item from the Multnomah Community Ability Scale (MCAS),11 Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS),12 knowledge level, medication checklist, attitudes and insight, which asked subjects if there was a week or 2 weeks in the past variable period of time during which they stopped medication, and medication refusal.

Table 1.

Adherence Definitions and Methodology

| Author(s) | Study Description* | N | Adherence Assessment | Criteria for Adherence |

| Abas et al. (2003)14 | Reasons for admission to hospital, retrospective | 225 | Chart review | If stated and contributory to admission |

| Adams and Scott (2000)15 | Predicting adherence using the Health Belief Model* | 39 | Self-report (ROMI, TRQ, rating from 0–100); all information used by rater | Highly adherent = >75%, partially adherent definitely = <70%, or uncertain adherence |

| Adams and Howe (1993)16 | Predicting adherence, retrospective* | 42 | Self-report (medication taking behavior in the month prior to admission) | Self-rated: 0, 25, 50, 75, or 100% |

| Adewuya et al. (2006)17 | Attitudes of outpatients in Nigeria* | 312 | Attitudes only (DAI) | DAI continuous variable |

| Agarwal et al. (1998)18 | Factors contributing to noncompliance* | 78 | Self-report, significant other report, and provider report | Noncompliant = not taking medication, only took when had supply |

| Amador et al. (1993)19 | Assessment of insight in psychosis | 43 | Self-report | 4-point scale |

| Arango et al. (2006)20 | Compare oral versus depot zuclopenthixol | 46 | Provider report (based on key informant and patient) | Adherence = 0%, 33%, 66%, or 100%, nonadherence = <33% |

| Ayers et al. (1984)21 | Subjective response to antipsychotic medication | 20 | Self-report, provider report, UA (inpatient) self-report, family report, pill count (outpatient) | Noncompliant = 4 months and off medication during 9-month period |

| Bachmann et al. (2005)22 | Neurological soft signs | 39 | Self-report | Dichotomous: regular intake vs not |

| Bechdolf et al. 200523 | Cognitive behavior therapy | 88 | Self-report, provider report, family report | Kemp 4-point scale: complete or partial refusal to active participation |

| Birchwood et al. (1992)24 | Influence of ethnicity and family structure on relapse (retrospective) | 137 | Chart review (impression from outpatient appointments, small number cross-checked) | No criteria stated |

| Boczkowski et al (1985)25 | Intervention to improve adherence* | 36 | Self-report, significant other report, pill count (brought in) | 5-point scale, number missing/number prescribed × 100 |

| Brown et al. (1987)26 | Factors related to adherence* | 32 | Self-report (to doctor and case manager), pill count (brought in monthly) | No information on scale for self-report; pills remaining in patient's allotment |

| Byerly et al. (2005)27 | Clinician ratings versus MEMS* | 25 | Provider report; MEMS | 7-point scale (Kemp); noncompliance = ≤4 at any month; daily adherence (MEMS) <70% during any month. |

| Byerly et al. (2005)28 | Compliance therapy* | 30 | Self-report (MARS), clinician rating, MEMS | Days adherent based on openings vs prescribed for MEMS |

| Casper and Regan (1993)29 | Reasons for admission | 416 | Self-report (retrospective) | Noncompliance = discontinued medication for 2 or more weeks prior to admission |

| Casper (1995)30 | Identification of recidivists | 45 | Self-report (retrospective on admission), chart review | 3 weeks+ without prescribed medication in the past 3 years |

| Chan (1984)31 | Medication compliance in Chinese outpatients* | 36 | Self-report | Totally compliant or missed doses on ≤2 occasions vs noncompliant |

| Chen et al. (2005)32 | First-episode patients | 93 | Provider report based on self-report and significant other report | Adherence = 70%+ |

| Christensen et al. (2006)33 | Naturalistic study of patients on aripiprazole | 42 | Provider report | None set: informal impression of improved adherence |

| Christensen (1974)34 | Factors influencing community success | 126 | Self-report | Not taken vs taken as prescribed (no cutoff defined) |

| Coldham et al. (2002)35 | Prospective study of adherence in first-episode patients* | 200 | Chart review, provider report, dropout | 3-point scale: nonadherent, inadequate (skipped but never longer than 2 weeks at a time), good (rarely or never missed) |

| Cuffel et al. (1996)36 | Insight and adherence* | 89 | Self-report, significant other report | 5-point scale: never missed to completely stopped |

| Conte et al. (1996)37 | Intervention to improve adherence* | 10 | Self-report, significant other report (prior to previous hospitalizations) | No description of cutoff, but noncompliance reported as leading to hospitalization |

| Dani and Thienhaus (1996)38 | Characteristics of patients in US and India | 95 | Self-report, significant other report | No criteria stated |

| Day et al. (2005)39 | Attitudes toward medication* | 228 | Self-report (DAI, Morisky Compliance Scale) | Morisky = 4-item scale about forgetting or skipping; ordinal |

| Diaz et al. (2004)40 | MEMS feasibility* | 50 | MEMS | % adherence = openings/prescribed openings |

| Diaz et al. (2001)13 | Prospective comparison of adherence* | 14 | MEMS | % adherence = openings/prescribed openings |

| Dixon et al. (1997)41 | Adherence and assertive community treatment* | 77 | Self-report, provider report, significant other report, pill count (subsample), blood level (subsample) | Noncompliant = refused or missed more than 1 week |

| Dolder et al. (2004)42 | Assessment of medication beliefs* | 63 | Self-report (DAI, brief evaluation of medication influences and beliefs), refill record | Cumulative mean gap ratio, continuous |

| Donohoe et al. (2001)43 | Predictors of compliance* | 32 | Self-report compliance interview (retrospective prior to hospitalization) | Poor = 0–25%, partial = 26–74%, good = 75%+ |

| Dorevitch et al. (1993)44 | Pharmacist medication maintenance program* | 14 | Self-report and missed appointments | Noncompliance = not taking oral medication, missed injection, missed appointments |

| Dossenbach et al. (2005)45 | Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcomes study of antipsychotics | 5833 | Self-report (unclear measure) | % compliance |

| Drake et al. (1991)46 | Housing instability | 75 | Provider report (rating) | Noncompliance = 4 or 5 on a 5-point scale |

| Drake and Wallach (1989)47 | Substance abuse | 187 | Provider report (rating) | 5-point scale |

| Duncan and Rogers (1998)48 | Correlates of compliance* | 90 | Provider report (rating) | Compliant = 80%+, noncompliant = 50% or less, mixed group = 51–79% |

| Eaddy et al. (2005)49 | Compliance and utilization* | 7864 | Electronic refill records | Compliance = 80–125%, partial compliance = <80%, overcompliance = >125% |

| Eckman et al. (1990)50 | Intervention to improve adherence* | 160 | provider report, significant other report | % of medication taken as prescribed |

| Elbogen et al. (2005)51 | Depression and social stability as factors in nonadherence* | 528 | Self-report | 1 = nonadherence, never compliant = 0, sometimes = 1, usually = 2, always = 3 |

| Falloon et al. (1985)52 | Family management | 36 | Self-report, provider report, significant other report, pill count, plasma levels | Irregular compliance = <75% of prescribed dose during each 1–2 month period |

| Farabee et al. (2004)53 | Predictors of adherence among parolees* | 150 | Urine (metabolite indicating recent ingestion) | Presence vs absence |

| Favre et al. (1997)54 | Expressed emotion and compliance* | 59 | Self-report, provider report | Discontinuing medication during 9-month follow-up |

| Fernando et al. (1990)55 | Factors related to community tenure | 70 | Self-report | Excellent = 61–100%, moderate = 21–60%, poor = 0–20% |

| Fleischhacker et al. (2005)56 | European first-episode trial | 500 | Self-report (DAI, Hayward) | Hayward 7-point scale, DAI continuous |

| Frangou et al. (2005)57 | Telemonitoring of adherence* | 108 | MEMS and Internet monitor | % taken/prescribed over entire study period |

| Frank and Gunderson (1990)58 | Therapeutic alliance | 143 | Self-report, provider report, chart review | Noncompliant = unilaterally altered dose, did not take full dose (cutoffs unclear) |

| Freudenreich et al. (2004)59 | Attitudes, clinical variables, and insight* | 81 | Self-report (DAI) | DAI score |

| Gaebel et al. (2002)60 | Intermittent vs continuous medication strategies | 363 | Provider report (rating) | 4-point scale: 0 = good, 3 = bad |

| Gaebel and Pietzcker (1985)61 | 1-year outcome | 72 | Self-report and sometimes provider report (unclear when) | Whether medication taken continuously |

| Garavan et al. (1998)62 | Relationships between compliance, attitudes, and insight* | 82 | Self-report (structured clinical interview retrospective over preceding 3 months) | 4-point scale: 0–24%, 25–49%, 50–74%, 75+%; irregular compliance = <75% |

| Garcia-Cabeza et al. (2001)63 | Prospective naturalistic study comparing medications | 2657 | Provider report | High = 80%, moderate = 60–79%, low = 20–59%, nil = <20% |

| Gilmer et al. (2004)64 | Adherence to antipsychotics and health care costs* | 2801 | Electronic refill (Medi-Cal Database) | Cumulative possession ration (days medication available/days eligible for Medi-Cal); nonadherent = 0–49%, partially adherent = 50–79%, adherent = 80–110% |

| Giron and Gomez-Beneyto (1995)65 | Family attitudes and relapse | 80 | Self-report, significant other report | Poor compliance = 75% or less or if stopped for 1 month+ |

| Giron and Gomez-Beneyto (1998)66 | Family attitudes and relapse | 80 | Self-report, provider report, significant other report | Irregular compliance = <75 % or interrupted for 1 month+, noncompliant = failed to take medication 4 weeks+ |

| Glick et al. (1991)67 | Inpatient family intervention | 169 | Self-report, significant other report, provider report (if other reports unreliable) | 6-point scale (unclear) |

| Glick and Berg (2002)68 | Relapse and compliance with second-generation and first-generation antipsychotics* | 996 and 339, 2 studies | Pill counts (between visits implied, unclear) | Examined time to first noncompliance; compliance = 80–120% |

| Godleski et al. (2003)69 | Olanzapine therapy in patients previously taking depots | 26 | Self-report, pill count (brought in) | % taken as prescribed |

| Gray et al. (2004)70 | Medication management training for nurses | 60 | Self-report, provider report | 7-point scale: 1 = complete refusal, 7 = active participation |

| Green (1988)71 | Compliance and hospitalization* | 50 | Chart review | Identified in records as a precipitant to admission |

| Grunebaum et al. (2001)72 | Medication supervision in residential care* | 74 | Self-report | Days not taken in past month |

| Grunebaum et al. (1999)73 | Supported housing | 36 | Chart review | 5-point scale: 0%, about 25%, about 50%, about 75%, all doses; compliant = took at least 50% |

| Guimâon (1995)74 | Adherence intervention* | 10 | Self-report (ad hoc instruments) | 4-point scale (unspecified) |

| Hamera et al. (1995)75 | Substance abuse | 17 | Self-report (checklist) | Compliant = took all, some, or more than prescribed, noncompliant = did not take at all |

| Hayward (1995)76 | Intervention to improve adherence* | 21 | Self-report (DAI), provider report, significant other report | 7-point scale: complete refusal to active participation |

| Hertling et al. (2003)77 | Comparison of flupenthixol and risperidone | 144 | Self-report (attitudes) | Change in DAI score |

| Hodgins et al. (2005)78 | Conduct disorder in schizophrenia | 248 | Self-report (daily use), urine and hair analysis for substance use only | Report that patient took medication as prescribed |

| Hoffmann (1994)79 | Factors related to rehospitalization | 50 | Provider report (rating) | 6-point scale: 1 = low, 6 = high |

| Hogan et al. (1983)80 | Self-report scale of compliance* | 150 | Self-report (DAI), provider report (rating) | 7-point scale: habitual refusal to overrreliant on medication |

| Holzinger et al. (2002)81 | Subjective illness theories of patients | Self-report at DC and 3 months | Percentage Adherence | |

| Hornung et al. (1996)82 | Psychoeducation* | 191 | Self-report, chart review | Dichotomized, but no specific criteria |

| Hunt et al. (2002)83 | Compliance, substance abuse, and community survival* | 99 | Provider report, chart review (prescription data targeted) | % of medication |

| Ito and Oshima (1995)84 | EE study | 88 | Provider report (rating) | Regular intake, irregular intake, injection, or refusal/cessation |

| Jarobe and Schartz (1999)85 | Cognition and compliance* | 8 | Chart review (clinical trial, daily calendar of medication taken, so may have included pill count) | % |

| Jerrell (2002)86 | Cost-effectiveness of medications | 108 | Chart review (including prescribing information) | % |

| Jeste et al. (2003)87 | Cognitive impairment as predictor of adherence | 110 | Ability to take medication | Performance score |

| Joyce et al. (2005)88 | Cost-effectiveness and compliance of medications* | 1810 | Electronic refill records | Medication possession ratio (days available/days prescribed), examined persistence |

| Kamali et al. (2006)89 | Adherence in first episode* | 100 | Self-report, compliance interview | Nonadherent = 0–74%, adherent = 75%+ |

| Kamali et al. (2001)90 | Factors influencing compliance* | 66 | Self-report (structured interview), DAI | 4-point scale:0–24%, 25–49%, 50–74%, 75+%; regular compliance = 75%+ |

| Kamali et al. (2000)91 | Substance misuse and suicidal ideation | 102 | Self-report (structured interview) | Regular compliance = 75%+, others irregular |

| Kampman et al. (2004)92 | Indicators of compliance in first episode* | 80 | Chart review | No specific information presented |

| Kampman et al. (2002)93 | Indicators of compliance in first episode* | 59 | Self-report, pill count if subject did not ask for refill (no indication of n of subset) | Regular/irregular/discontinued |

| Kapur et al. (1992)94 | Riboflavin marker in compliance assessment* | 20 | Urine analysis of tracer, provider report (rating) | Presence or absence in 18–24 hour period, visual analog 0–100 |

| Kashner et al. (1991)95 | Family characteristics related to hospitalization and substance abuse | 121 | Chart review (retrospective) | No criteria stated |

| Kelly et al. (1987)96 | Health belief model and medication adherence* | 107 | Self-report (barriers and pill taking errors in past week) | Global score (continuous) |

| Kelly and Scott (1990)97 | Intervention to improve adherence* | 418 | Self-report (pill taking errors in past week) | Discontinuation (present/absent), dosage deviation (present/absent) |

| Kemp et al. (1996)98 | Adherence intervention* (continuation of above study) | 47 | Self-report (DAI), provider report, significant other report | 7-point scale: complete refusal to active participation |

| Kemp et al. (1998)99 | 74 | Self-report, provider report, significant other report (mean of 2 sources) | 7-point scale: complete refusal to active participation | |

| Kinon et al. (2003)100 | Open label olanzapine disintegrating tablets | 85 | Self-report (ROMI, TCI), plasma levels taken but not used due to interpatient variability | Continuous |

| Kiraly et al. (1998)101 | Risperidone treatment response | 101 | Provider report | 4-point scale: poor to good |

| Klingberg et al. (1999)102 | Psychoeducation* | 156 | Provider report (rating) | Dichotomized, but no specific criteria |

| Knapp et al. (2004)103 | Nonadherence and cost* | 658 | Self-report (survey of residential facilities) | Taking less or more than prescribed |

| Koukia et al. (2005)104 | Caregiver burden | 134 | Self-report, family report (unclear method) | Operational definition of medication compliance, variable unclear |

| Lecompte and Pelc (1996)105 | Adherence intervention* | 64 | Self-report (unclear) | Noncompliant = minimum of 2 hospitalizations due to noncompliance; length of hospital stay postintervention |

| Li and Arthur (2005)106 | Family education | 101 | Self-report | 4-point scale; noncompliance = stopping for 1 week+ or change in dose against medical advice |

| Lin et al. (1979)107 | Insight and adherence* | 100 | Self-report, provider or significant other report (as validation only) | Nonadherent = did not take, discontinued, other report rated as noncompliant |

| Linn et al. (1982)108 | Relapse in foster care | 151 | Self-report, provider report | Taken as prescribed with supervision, taken as prescribed without supervision, probably not taken |

| Linden et al. (2001)109 | Predicting adherence* | 122 | Dropouts from medication treatment | Noncompliant = dropout |

| Lindstrom (1989)110 | Retrospective clozapine efficacy | 96 | Self report, chart review | No specific information on cutoffs or definition |

| Linszen et al. (1998)111 | Early intervention | 76 | Provider report (rating), pill counts (occasional?) | 4-point scale: 0–24% (none/irregular), 25–49% (rather irregular), 50–74% (rather regular), 75–100% (regular) |

| Loffler et al. (2003)112 | Subjective reasons for compliance | 307 | Self-report (ROMI) | Scale score |

| Macpherson et al. (1997)113 | Drug refusal* | 54 | Self-report (SAI), provider report, chart review | Active refusal, passive acceptance, active pursual; always, usually, not usually, never |

| Macpherson et al. (1996)114 | Educational intervention* | 64 | Self-report (SAI) | Compliance subscale score |

| Marom et al. (2005)115 | Expressed emotion and 1-year follow-up of next116 | 108 | Self-report, chart review, recollection | Dichotomized at 50% |

| Marom et al. (2002)116 | Expressed emotion | 108 | Self-report, chart review (prior to admission), anamnesis | Dichotomized at 50% |

| Martic-Biocina and Baric (2005)117 | Assessment of reasons for stopping medication* | 42 | Self-report, reasons for stopping medication | No definition of compliance provided |

| McEvoy et al. (1984)118 | Relapse and compliance* | 32 | Self-report, provider report, significant other report | Dichotomized; taken as prescribed most of the time during previous 2 months |

| McEvoy et al. (1989)119 | Insight and psychopathology | 52 | Provider report (inpatient) | Active, passive, resistance, overt refusal |

| McFarlane et al. (1995)120 | Multiple family group vs psychoeducation | 172 | Provider report (rating based on all available sources; unclear what other sources and how many) | 6-point scale: 0, 25%, 50%, 75%, 90%, 100% |

| Menzin et al. (2003)121 | Prospective over 1 year at start of medication | 298 | Electronic refill (Medicaid data) | Number of days medication available over 1-year follow-up; medication discontinued or switch |

| Merinder et al. (1999)122 | Psychoeducation* | 79 | Chart review (prescribing information) | Noncompliant episode = no medication for 14 days; number of episodes |

| Nageotte et al. (1997)123 | Health belief model and medication adherence* | 101 | Self-report, significant other report | Compliant = took all or missed only occasionally |

| Nakonezny and Byerly (2006)124 | Adherence to first- and second-generation antipsychotics* | 61 | MEMS | Percentage; openings/prescribed for 1 month |

| Nelson et al. (1975)125 | Variables related to compliance* | 40 | Urine analysis | Negative samples/total samples × 100 |

| Ng et al. (2001)126 | Expressed emotion | 33 | Provider report (rating) based on self-report and significant other report | 4-point scale: 0–24% (none), 25–49% (irregular), 50–74% (vaguely regular), 75–100% (regular) |

| Norman and Malla (2002)127 | Adherence, substance abuse, and psychosis* | 90 | Self-report, provider report (WQLS) | 5-point scale: never to always |

| O'Donnell et al. (2003)128 | Compliance therapy* | 56 | Self-report(structured interview), significant other report, provider report | 0–24%, 25–49%, 50–74%, 75+%; compliance problem = <50% |

| Olfson et al. (2000)129 | Prediction of noncompliance* | 213 | Self-report | Compliance = 1 week+ off medication |

| Olfson et al. (1998)130 | Inpatient and outpatient linkage* | 104 | Self-report | 1 week+ off medication |

| Owen et al. (1996)131 | Nonadherence and substance abuse* | 135 | Self-report | 5-point scale: never missed to refused or stopped; compliant = rarely or never missed; those who rated 1 or 2 were “compliant,” 3 and up were considered “noncompliant” |

| Parker and Hadzi-Pavlovic (1995)132 | Life skills profile | 118 | Self-report, significant other report, provider report | Dichotomized but no specific information on how |

| Parkin et al. (1976)133 | Adherence postdischarge | 130 | Self-report; pill count (in home) | Percentage deviation from prescribed; nonadherence = >15% |

| Pristach and Smith (1990)134 | Compliance and substance abuse* | 42 | Self-report (chart review and information from significant other to verify; unclear how information used or how many had it) | Retrospective, not taking as prescribed prior to admission |

| Pyne et al. (2001)135 | Charts of patients who do not believe they are ill | 129 | Self-report, significant other report | 5-point scale: from never missed to completely stopped |

| Razali et al. (2000)136 | Comparison of psychosocial interventions | 143 | Other report, pill count (doubtful cases only not specified) | Noncompliant, 25%, 50%, 75%, 90%, 100%; 90% considered ideal |

| Razali and Yahya (1995)137 | Compliance intervention program* | 225 | Self-report | Good compliance = did not miss more than 2 doses on separate occasions, did not miss 2 consecutive doses in a 2-week period, and also attended all follow-ups or missed only 1; poor compliance = did not meet these criteria |

| Rettenbacher et al. (2004)138 | Attitudes toward illness and medication* | 61 | Self-report (plasma levels taken but not used in analysis—states these agreed with adherence designation but not reported) | Fully compliant = none missed; partially compliant = no more than 7 consecutive days missed, or nonauthorized dose reduction during preceding 3 months; noncompliant = missed >7 days |

| Rijcken et al. (2004)139 | Refill rate to assess compliance* | 429 | Electronic refill | Number of prescribed days/calendar days; compliance = 90%+ |

| Robinson et al. (2002)140 | Predictors of medication discontinuation in first episode* | 112 | Self-report, family report, provider report | Stopping medication for 1 week+ |

| Rosa et al. (2005)141 | Factors related to compliance* | 50 | Self-report (ROMI), family report | Noncompliance = <75% in preceding 30 days |

| Rosenheck et al. (2000)142 | Clozapine vs haloperidol | 423 | Pill count | Medication continuation and regimen compliance |

| Ruscher et al. (1997)143 | Compliance and attitudes* | 148 | Self-report | Noncompliant = dose or timing differences from prescribed, or discontinuation |

| Rzewuska (2002)144 | Compliance and course* | 94 | Self-report | Time taken during remission vs time not taken during remission |

| Sellwood and Tarrier (1994)145 | Demographics as predictor of noncompliance* | 256 | Provider report | Noncompliant = persistently refused all medication, vs all others |

| Sellwood et al. (2001); Sellwood et al. (2003)146,147 | Family intervention and compliance* (2003) | 79 | Self-report, chart review | <10%, 10–50%, 50–90%, 90%+; compliant = 90%+ |

| Seo and Min (2005)148 | Explanatory model of adherence* | 208 | Self-report, family report | % compliance continuous variable, no cutoff |

| Seltzer et al. (1980)149 | Psychoeducation* | 52 | Pill count and urine (brought in; n = 32) | Compliant = positive urine, 80% of pills taken |

| Serban and Thomas (1974)150 | Attitudes toward ambulatory treatment | 641 | Self-report, significant other report (SSFIPD) | Regular compliance vs irregular; cutoff not provided |

| Shvartsburd et al. (1984)151 | Blood levels in maintenance treatment | 21 | Self-report, pill count, blood | No specific information on cutoffs or criteria |

| Sibitz et al. (2005)152 | Attitudes toward medication* | 92 | Self-report (DAI) | Dichotomized based on DAI |

| Smith et al. (1997)153 | Insight and compliance* | 33 | Self-report, chart review, significant other report | % taken correctly |

| Sullivan et al. (1995)154 | Risk factors for hospitalization | 101 | Self-report, significant other report, chart review | Noncompliant = taken <50%; self-report unless conflicted with report of significant other |

| Suzuki et al. (2005)155 | Simplifying medication regimen* | 50 | Treatment provider report | At least partially compliant vs not at all |

| Svarstad et al. (2001)156 | Adherence and hospitalization* | 619 | Electronic refill (Medicaid claims) | Regular vs irregular users based on claim missed for 1 quarter |

| Svedberg et al. (2001)157 | First-episode patients | 71 | Chart review (prescribing information) | Noncompliant = too much or too little medication; totally noncompliant = refused |

| Swanson et al. (2004)158 | Atypicals and violence | 229 | Self-report | 5-point scale: never missed to completely stopped |

| Thompson et al. (2000)159 | Adherence rating scale* | 66 | Self-report (DAI and MAQ), provider ratings (where available), blood level (n = 17, lithium only) | Scale score: noncompliant = 0, compliant = 1 |

| Trauer and Sacks (1998)160 | Compliance views of clients and doctors* | 254 | Self-report, provider report (rating) | Active, passive, resistance, refusal; 0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 100% |

| Valenstein et al. (2001)161 | Adherence and depot medication | 1307 | Provider report | All, most, quite a bit, some, none; strict compliance = all; broad compliance = all or most |

| Van Putten et al. (1976)162 | Drug refusal* | 59 | Provider report (rating) | Dichotomized into refusers and compliers (anyone not refusing) |

| Vaughan et al. (2000)163 | Community treatment orders | 246 | Self-report, significant other report, chart review | Number of days of noncompliance prior to admission |

| Vauth et al. (2004)164 | Adherence assessment* | 184 | Self-report (ROMI) | 4-point scale |

| Velligan et al. (2003)1 | Adherence* | 68 | Self-report, pill count, blood levels | 5-point scale: compliant = 80%, blood level consistency |

| Verghese et al. (1989)165 | Course and outcome | 323 | Self-report (unspecified) | Regular vs irregular compliers (unspecified) |

| Weiden et al. (1995)166 | Postdischarge compliance* | 93 | Self-report (TCI, ROMI) | 5-point scale: completely noncompliant to completely compliant |

| Weiden et al. (2004b)167 | Compliance and obesity* | 304 | Self-report | 5-point scale: never missing to almost always; compliant = never missing, noncompliant = all others |

| Weiden et al. (2004a)168 | Partial compliance and rehospitalization* | 4325 | Electronic refill (Medicaid data) | Gaps in therapy, number of mean gaps, mean gap duration, consistency, persistence |

| Weiss et al. (2002)169 | Predictors of nonadherence* | 162 | Provider report | 4-point scale: active, passive, resistant, refusal; dichotomized into active adherence vs problem |

| Xiong et al. (1994)170 | Family intervention | 63 | Significant other report | Compliant = took >50% of medication for 75% of follow-up period |

| Yamada et al. (2006)171 | Reasons for noncompliance* | 90 | Self-report (ROMI) | Noncompliance = 1-week interruption during follow-up period |

| Yen et al. (2005)172 | Compliance and insight* | 139 | Self-report (SAI and ad hoc Medication Adherence Behavior Scale) | Continuous |

| Ziguras et al. (2001)173 | Influences of medication compliance | 168 | Self-report (MCAS) | 5-point scale: almost never complies to almost always complies; poor adherence = <30% |

Note: *Specific Adherence Study; DC = discharge; EE = Expressed Emotion; MAQ = Medication Adherence Questionnaire; SAI = Schedule for the Assessment of Insight; SSFIPD = Social Stress and Functioning Inventory in Psychotic Disorders; TRQ = Tablets Routine Questionnaire; UA = Urine Analysis; WQLS = Wisconsin Quality of Life Scale.

Other methods were used less frequently. In order of frequency, methods were treatment provider report, family or significant other report, chart review, pill count, electronic refill information, electronic monitoring, blood level, urine analysis of medication, and urine analysis of a tracer substance. Figure 1 illustrates the specific frequencies of use of each method in the 161 studies. The subjective/indirect measures of assessing adherence were used 218 times (some studies used more than 1 of these methodologies) and were the only measures used in 124 of the 161 studies. Out of 161 studies, pill counts, blood levels, urine analysis, electronic monitoring, electronic refill records, or tracers that could provide objective or direct data regarding medication adherence were used only 43 times, representing a total of 37 of 161 studies. Of these 37 studies, 27 were specifically adherence studies and 10 were general studies. In one-fourth of these studies, the objective methodology was used only in part of the sample, only when reports by the patient were questioned (no criteria provided), only when the patient brought the urine or pills in to be examined, or only when available (usually with no information on how many subjects had such data available). One study used ability to take medication in a performance-based assessment.

Fig. 1.

Number of Times Specific Adherence Methodologies Have Been Utilized.

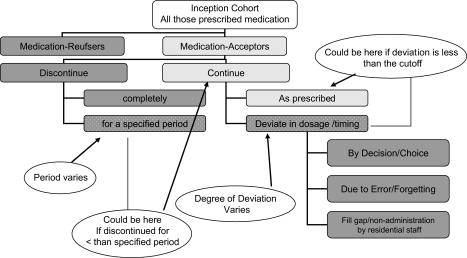

Even in cases where studies used the same methodology to assess adherence, the definition of adherence varied greatly. Figure 2 describes the various levels of discrimination between adherence and nonadherence and the numerous ways to define nonadherence to oral medication. Any inception cohort of individuals for whom it is recommended that medication be taken continuously can be divided into those who refuse and those who accept medication. In a study using this first level of discrimination depicted in Figure 2, those who agree to take medication (accept) would be adherent, and all others would be considered nonadherent. For those who accept the medication, the next level divides subjects into those who continue to use it for a period of time and those who discontinue use for some time period, which varies across studies. At this level, those who discontinue use are nonadherent, all those who continue using the medication, even if dosages vary considerably from what is prescribed, are considered adherent. The next level of inquiry examines only those who continue to take medication. These individuals may take medication as prescribed or not. How much an individual can vary from the prescribed dosage and still be considered compliant differs by study. Dosage deviations can be due to a decision that less medication is better, due to unintentional factors such as forgetting, or due to environmental barriers such as poverty and lack of transportation.

Fig. 2.

Defining Subjects in Adherence Studies.

With respect to dosage deviation, in the 161 articles we found dosage cutoffs that ranged from 50% to 90% and categorical classifications ranging from taking any of the prescribed medication to taking nearly every dose. Likert-type scales that were not divided into percentage of medication taken varied from 3 points to 7 points, with a variety of different terms for each point, including “overreliance on medication” at the high end of 1 scale.

For electronic refill data, a common adherence measure was the mean gap or the length of time for which no medication was available to the patient. An alternative measure examined patients who had gone a quarter without a claim for medication.

Several studies reported using Medication Event Monitoring System, or MEMS—pill bottle caps capable of recording the time and date each time the bottle is opened. Openings for other reasons (eg, filling), if known to the researchers, must be deleted to provide an accurate estimate of the number of doses taken. While MEMS is sometimes described as a “gold standard” of adherence assessment, in the studies using MEMS for schizophrenia patients, the fact of missing data was identified as a problem. One study reported close to 45% of data missing due to failures on the part of the patient to bring in the MEMS caps in order to download the information.13

Discussion

The review illustrates the heavy reliance in the field on self-report and other subjective/indirect measures of adherence, which are known to be significantly flawed. Unfortunately, each method used to assess adherence to oral medications in this population has its own drawbacks. Self-report often exaggerates the degree of adherence. A commonly cited quotation from subjects regarding self-report of adherence behavior goes as follows: “How do you expect me to remember when I forget to take my medication?” Provider report may be based on the report of the patient or on a worsening clinical condition, which may be related either to poor adherence or to a failure of the chosen medication to control symptoms. The report of significant others is affected by how much time the respondent spends with the identified subject and how directly involved the significant other may be in the subject's care. This method cannot be used when patients do not have sufficiently involved informants. Studies using chart review often did not specify the information available in the chart to make a determination about adherence. References to medication adherence in the chart may turn out to be based largely on self-report.

More direct or objective measures of assessment also have problems. Pill counts and refill records can be affected by the use of samples and old medications that are still available to the patient. Pill counts are often complicated by medication from earlier time periods that are added to current prescription bottles. This leaves the researcher with more pills to count than the number indicated on the bottle as dispensed by the pharmacy. Most studies reviewed expected patients to bring in bottles for the pill count; some required patients to bring in urine samples or electronic monitors (MEMS caps). This methodology is likely to bias results toward finding higher levels of compliance. Electronic monitoring can also be problematic when subjects do not replace the caps or take medication out of alternative bottles. While electronic monitoring is considered a gold standard in adherence research with other populations, the cognitive impairments and unstable living environments often found in patients with schizophrenia may make it necessary to use alternative methodologies such as home visits to retrieve MEMS data or using a system that automatically downloads adherence information.57,174

Electronic prescribing records provide an objective assessment of the medication obtained by the patient. Unfortunately, just because medication is available does not mean that it is taken. While this method is likely to underreport problems with adherence, utilizing electronic refill data in large samples can provide substantial power to examine relationships between adherence and outcomes from a cost perspective. Certain assumptions must be made in utilizing such data (eg, that prescriptions are not filled outside of the system). In addition, decisions must be made regarding how to deal with subjects taking more than 1 antipsychotic medication (eg, delete all subjects with multiple antipsychotic prescriptions during the specified period). Accuracy problems may occur when subjects are given unrecorded samples, when medications are filled outside the system, and when old medications from prior episodes of poor adherence are available to the patient.

Even blood levels cannot be considered a gold standard for adherence as they can be highly affected by behaviors in the days immediately prior to the blood draw. Thus, the sample obtained may not represent the level of adherence over a more extended time period (1 month, 3 months). Moreover, there is a great deal of individual variability in blood levels across patients. With the atypical antipsychotic medications there is very little data about appropriate or therapeutic blood levels to use as a criterion.100 In fact, in a recent study of olanzapine, blood levels were taken but not used as the primary measure of adherence for this reason.100 Obviously, the more intrusive or elaborate the method of adherence assessment, the more it will deviate from clinical practice and be less appropriate for use by practicing clinicians. Moreover, some adherence assessments can influence adherence behavior.

Few studies appropriately critique their own methods for assessing adherence or point out the problems encountered in obtaining the data using the chosen method(s). This can make it somewhat unclear whether the conclusions of the studies are fully supported by the data presented.

With respect to the definition of adherence, the field may not have as many definitions as studies, but the number of definitions is clearly problematic. More often than not, the definitions and rationales for the choices are not clearly explained. Because definitions differ, the same subject could be categorized differently depending on the study. For example, a patient who takes about 55% of his or her antipsychotic medication would be classified as adherent in a study examining medication refusal as the criterion for nonadherence. This same patient would be classified as nonadherent if he or she discontinued medication for at least a 1-week period in a study using this as the method to define the nonadherent group. In a study using a cutoff of taking at least 50% of medication, this patient would fall into the adherent group, even if he or she did not take any medication for a 1-week period because the measure used averages over a period of 1 month. The same patient would be nonadherent in a study using a higher cutoff percentage during the specified time period.

What is an appropriate percentage of medication for an individual to take before he or she is considered poorly adherent? Based on the review, the answer to this question is far from clear. Percentage of medication taken as prescribed could be used as a continuous variable. However, the percentage may have high variability, necessitating very large sample sizes before statistical significance could be found in treatment studies in which a treatment would have a moderate effect. In addition, the difference between taking 0% versus 25% or 80% versus 100% of prescribed medication may not be clinically significant. Therefore, grouping subjects into clusters of 0 to 29%, 30–69%, and 70–75%+ may make conceptual sense. Part of the difficulty may be that each investigator examines their data and chooses cut points based on natural breaks in their data. Arbitrarily choosing 80% as a cutoff for adherence may yield no adherent patients in some studies.

The issue of percentage of medication taken as prescribed to classify adherence is further complicated by the tendency over time for physicians to increase the dosage of medication when symptoms are not well controlled. Over time, dosages can creep up because patients are not fully adherent, making the full dose clinically inappropriate when the patient is taking medication as prescribed.

It is common to validate adherence measures against clinical outcome. This is best seen in studies of electronic pharmacy records in which gaps in having medication available predict hospitalization. However, there may be problems in using some clinical outcome data to validate adherence measures. It is not uncommon for treating physicians to base their impression of adherence on clinical state (symptomatology, clinical global impression). Therefore, it is possible that physician-rated adherence would have a stronger relationship with clinical state than adherence assessed through more objective means. It is also true that we do not know the clinical consequences of many types of nonadherence.

Suggestions for Consensus Development

Definitions

Given the confusion in the field, we would propose defining those who do not accept medication as “medication refusers” to distinguish them from individuals who continue to take medication but may have adherence problems. This latter group of medication acceptors can then be further divided by degrees of adherence. This is important because complete refusal may begin as a function of missed or skipped doses, either intentional or accidental. It is likely that what predicts medication refusal and what predicts irregular compliance, or what we call “dosage deviation,” may be very different. It is also likely that treatment approaches to these 2 groups of individuals may need to target very different variables, insight in the former case and cognitive deficits or environmental problems in the latter. It is unclear how patients who discontinue the use of medication for 1 week or longer compare with those who somewhat consistently take half of their prescribed dosage. Moreover, it is likely to be very important to distinguish those who deviate in dosage by choice versus those who inadvertently miss medication due to forgetting, misunderstanding, poverty, or other environmental barriers. The focus of intervention for these groups could vary considerably.

Study Design

Prospective studies that follow patients over time and examine adherence are necessary to determine predictors of problem adherence. The difficulties with retrospective data, particularly in the schizophrenia population, are numerous and include problems with inaccurate recall and backward reasoning (“I got sick, so I must have forgotten to take my medication”). Longer follow-up periods are likely to minimize the impact of assessing adherence on adherence behavior.

Comparability Among Studies

To increase comparability among studies, it would be helpful for each investigation to report an estimate of the mean percentage of medication taken during the follow-up period, even if the primary measure of adherence is operationalized otherwise. This would allow studies to be compared on a common variable. At the same time, this would allow investigators to group patients according to natural breaks in their data and the overall adherence level in their samples.

Assessment

We would suggest that all studies include at least 2 measures of adherence and that at least 1 of these be a direct or objective measure such as pill count, urine analysis, blood analysis (if problems discussed below have been addressed), electronic monitoring, pharmacy refill records, or the examination of tracer substances in blood or urine. Pharmacy refill records have been found to be useful for large samples, but it is unclear whether this method will be sensitive in smaller samples investigating the effects of clinical treatment. While it may be economically prohibitive in some studies and inconvenient in all studies, doing pill counts, downloading electronic monitoring devices, and collecting blood or urine are likely to be best accomplished during home visits. We have been able to decrease loss of data to less than 5% by downloading MEMS information from the caps on home visits using laptop computers. Alternatively, using more sophisticated electronic devices such as the Med-eMonitor174 is recommended. This device records the same type of data as MEMS but stores up to 5 different medications. Using an LCD readout, the monitor can query the subject as to whether a specific compartment has been opened for the purpose of taking medication or for some other reason. Most important, the monitor downloads adherence data automatically to a secure Web site, decreasing problems with data retrieval.174

An in-home setup at the beginning of studies that use electronic monitoring and pill counts can cut down on problems. For example, extra medications can be bagged and stapled and only recounted if the seal is broken. A box can be provided for patients to store empty bottles, making determinations of pills dispensed more accurate over time. Pill counts should be cross-referenced with prescribing records to deal with some of the problems described above, such combining bottles together. Training on the use of electronic monitoring devices, providing belt bags to carry the larger electronic pill containers, and using the more sophisticated devices may advance the field.

Because there is so much variability in blood-level data from patient to patient for the atypical antipsychotic medications, if blood samples are collected, obtaining individualized baseline levels during a period in which all medication taking is monitored may be ideal. Randomly drawn blood levels during a follow-up period can then be compared with the baseline levels for consistency between consecutive levels and consistency in plasma level/dose. However, unless better procedures for interpreting blood-level data become available in the near future for the atypical antipsychotic medications, it is unclear how blood-level data will assist the field in better understanding adherence.

The use of multivariable algorithms that combine measures to make a determination of adherence level needs further investigation. One approach would involve assessing larger samples of patients with multiple measures of adherence. With samples approaching 200, factor analytic techniques could be used to determine whether adherence could be conceptualized as a latent variable in which the various sources of error could be explicitly modeled.

While the assessment of the ability to take medication is important for this population, the ability to perform a task does not always translate into performing the task in the natural environment. Because adherence problems are likely to be multidetermined in the natural environment, the usefulness of ability as a proxy for actual adherence may be limited.

Irrespective of method, we recommend briefly describing the reasons for selection of the method, the pros and cons of the method selected, and the actual problems encountered in obtaining the data. For example, a recent study by Grymonpre et al.4 in an elderly population describes the problems encountered in their sample while obtaining pill counts. Including this type of information in a report would assist readers in evaluating the conclusions of the study.

In summary, to be successful in identifying predictors of adherence and developing interventions we need to do better in defining and assessing adherence. By putting into place some standardization of terms and procedures, the field is more likely to accomplish these goals. These suggestions for consensus development most closely apply to adherence to oral antipsychotic medications in psychosis patients. However, given that the vast majority of prescriptions for atypical antipsychotic medications are “off-label,” the problems in assessment and the recommendations made may be relevant for a wider range of populations.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Velligan, Dr. Lam, Dr. Ereshefsky, and Dr. Miller were supported in part during the writing of this paper by National Institutes of Mental Health grant R01 MH62850-05. Dr. Velligan, Dr. Miller, and Dr. Glahn were supported in part during the writing of this paper by National Institutes of Mental Health grant R01 MH61775-04.

References

- 1.Velligan DI, Lam F, Ereshefsky L, Miller AL. Psychopharmacology: perspectives on medication adherence and atypical antipsychotic medications. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:665–667. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.5.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiden P, Glazer W. Assessment and treatment selection for “revolving door” inpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Q. 1997;68:377–392. doi: 10.1023/a:1025499131905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dolder CR, Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Jeste DV. Antipsychotic medication adherence: is there a difference between typical and atypical agents? Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:103–108. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grymonpre RE, Didur CD, Montgomery PR, Sitar DS. Pill count, self-report, and pharmacy claims data to measure medication adherence in the elderly. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:749–754. doi: 10.1345/aph.17423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haynes RB. Introduction. In: Sackett DL, Taylor DW, editors. Compliance in Health Care. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenton WS, Blyler CR, Heinssen RK. Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23:637–651. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.4.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oehl M, Hummer M, Fleischhacker WW. Compliance with antipsychotic treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;102(suppl):83–86. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zygmunt A, Olfson M, Boyer CA, Mechanic D. Interventions to improve medication adherence in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1653–1664. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiden P, Rapkin B, Mott T, et al. Rating of Medication Influences (ROMI) scale in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1994;20:297–310. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hogan TP, Awad AG, Eastwood R. A self-report scale predictive of drug compliance in schizophrenics: reliability and discriminative validity. Psychol Med. 1983;13:177–183. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700050182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barker S, Barron N, McFarland B, Bigelow D. A community ability scale for chronically mentally ill consumers: part I. reliability and validity. Community Ment Health J. 1994;30(4):363–383. doi: 10.1007/BF02207489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson K, Kulkarni J, Sergejew AA. Reliability and validity of a new Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS) for the psychoses. Schizophr Res. 2000;42:241–247. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diaz E, Levine HB, Sullivan MC, et al. Use of the Medication Event Monitoring System to estimate medication compliance in patients with schizophrenia. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2001;26:325–329. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abas M, Vanderpyl J, Le Prou T, Kydd R, Emery B, Foliaki SA. Psychiatric hospitalization: reasons for admission and alternatives to admission in South Auckland, New Zealand. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2003;37:620–625. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams J, Scott J. Predicting medication adherence in severe mental disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101:119–124. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.90061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams SG, Jr, Howe JT. Predicting medication compliance in a psychotic population. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993;181:558–560. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199309000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adewuya AO, Ola BA, Mosaku SK, Fatoye FO, Eegunranti AB. Attitude towards antipsychotics among outpatients with schizophrenia in Nigeria. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113:207–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agarwal MR, Sharma VK, Kishore Kumar KV, Lowe D. Non-compliance with treatment in patients suffering from schizophrenia: a study to evaluate possible contributing factors. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1998;44:92–106. doi: 10.1177/002076409804400202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amador XF, Strauss DH, Yale SA, Flaum MM, Endicott J, Gorman JM. Assessment of insight in psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:873–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arango C, Bombín I, González-Salvador T, García-Cabeza I, Bobes J. Randomised clinical trial comparing oral versus depot formulations of zuclopenthixol in patients with schizophrenia and previous violence. Eur Psychiatry. 2006;21:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayers T, Liberman RP, Wallace CJ. Subjective response to antipsychotic drugs: failure to replicate predictions of outcome. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1984;4:89–93. doi: 10.1097/00004714-198404020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bachmann S, Bottmer C, Schroder J. Neurological soft signs in first-episode schizophrenia: a follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2337–2343. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bechdolf A, Kohn D, Knost B, Pukrop R, Klosterkotter J. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy and group psychoeducation in acute patients with schizophrenia: outcome at 24 months. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112:173–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Birchwood M, Cochrane R, Macmillan F, Copestake S, Kucharska J, Carriss M. The influence of ethnicity and family structure on relapse in first-episode schizophrenia: a comparison of Asian, Afro-Caribbean, and white patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;161:783–790. doi: 10.1192/bjp.161.6.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boczkowski JA, Zeichner A, DeSanto N. Neuroleptic compliance among chronic schizophrenic outpatients: an intervention outcome report. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53:666–671. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.5.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown CS, Wright RG, Christensen DB. Association between type of medication instruction and patients' knowledge, side effects, and compliance. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1987;38:55–60. doi: 10.1176/ps.38.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Byerly M, Fisher R, Whatley K, et al. A comparison of electronic monitoring vs. clinician rating of antipsychotic adherence in outpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2005;133:129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Byerly MJ, Fisher R, Carmody T, Rush AJ. A trial of compliance therapy in outpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:997–1001. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casper ES, Regan JR. Reasons for admission among six profile subgroups of recidivists of inpatient services. Can J Psychiatry. 1993;38:657–661. doi: 10.1177/070674379303801006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Casper ES. Identifying multiple recidivists in a state hospital population. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46:1074–1075. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.10.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan DW. Medication compliance in a Chinese psychiatric out-patient setting. Br J Med Psychol. 1984;57:81–89. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1984.tb01585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen EY, Hui CL, Dunn EL, et al. A prospective 3-year longitudinal study of cognitive predictors of relapse in first-episode schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Res. 2005;77(1):99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Christensen AF, Poulsen J, Nielsen CT, Bork B, Christensen A, Christensen M. Patients with schizophrenia treated with aripiprazole, a multicentre naturalistic study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113:148–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christensen JK. A 5-year follow-up study of male schizophrenics: evaluation of factors influencing success and failure in the community. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1974;50:60–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1974.tb07657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coldham EL, Addington J, Addington D. Medication adherence of individuals with a first episode of psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106:286–290. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.02437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cuffel BJ, Alford J, Fischer EP, Owen RR. Awareness of illness in schizophrenia and outpatient treatment adherence. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1996;184:653–659. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199611000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conte G, Ferrari R, Guarneri L, Calzeroni A, Sacchetti E. Reducing the “revolving door” phenomenon. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1512. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.11.1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dani MM, Thienhaus OJ. Characteristics of patients with schizophrenia in two cities in the U.S. and India. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47:300–301. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.3.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Day JC, Bentall RP, Roberts C, et al. Attitudes toward antipsychotic medication: the impact of clinical variables and relationships with health professionals. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:717–724. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.7.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diaz E, Neuse E, Sullivan MC, Pearsall HR, Woods SW. Adherence to conventional and atypical antipsychotics after hospital discharge. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:354–360. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dixon L, Weiden P, Torres M, Lehman A. Assertive community treatment and medication compliance in the homeless mentally ill. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1302–1304. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.9.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dolder CR, Lacro JP, Warren KA, Golshan S, Perkins DO, Jeste DV. Brief evaluation of medication influences and beliefs: development and testing of a brief scale for medication adherence. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:404–409. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000130554.63254.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Donohoe G, Owens N, O'Donnell C, et al. Predictors of compliance with neuroleptic medication among inpatients with schizophrenia: a discriminant function analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2001;16:293–298. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(01)00581-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dorevitch A, Aronzon R, Zilberman L. Medication maintenance of chronic schizophrenic out-patients by a psychiatric clinical pharmacist: 10-year follow-up study. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1993;18:183–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.1993.tb00610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dossenbach M, Arango-Davila C, Ibarra HS, et al. Response and relapse in patients with schizophrenia treated with olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, or haloperidol: 12-month follow-up of the Intercontinental Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcomes (IC-SOHO) study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1021–1030. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Drake RE, Wallach MA, Teague GB, Freeman DH, Paskus TS, Clark TA. Housing instability and homelessness among rural schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:330–336. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.3.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Drake RE, Wallach MA. Substance abuse among the chronic mentally ill. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1989;40:1041–1046. doi: 10.1176/ps.40.10.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duncan JC, Rogers R. Medication compliance in patients with chronic schizophrenia: implications for the community management of mentally disordered offenders. J Forensic Sci. 1998;43:1133–1137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eaddy M, Grogg A, Locklear J. Assessment of compliance with antipsychotic treatment and resource utilization in a Medicaid population. Clin Ther. 2005;27(2):263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eckman TA, Liberman RP, Phipps CC, Blair KE. Teaching medication management skills to schizophrenic patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990;10:33–38. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199002000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Elbogen EB, Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Van Dorn R. Medication non-adherence and substance abuse in psychotic disorders: impact of depressive symptoms and social stability. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193:673–679. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000180742.51075.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Falloon IR, Boyd JL, McGill CW, et al. Family management in the prevention of morbidity of schizophrenia: clinical outcome of a two-year longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:887–896. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790320059008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Farabee D, Shen H, Sanchez S. Program-level predictors of antipsychotic medication adherence among parolees. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2004;48:561–571. doi: 10.1177/0306624X04263884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Favre S, Huguelet MA, Vogel S, Gonzalez MA. Neuroleptic compliance in a cohort of first episode schizophrenics: a naturalistic study. Eur J Psychiatry. 1997;11:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fernando ML, Velamoor VR, Cooper AJ, Cernovsky Z. Some factors relating to satisfactory post-discharge community maintenance of chronic psychotic patients. Can J Psychiatry. 1990;35:71–73. doi: 10.1177/070674379003500111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fleischhacker WW, Keet IP, Kahn RS. The European First Episode Schizophrenia Trial (EUFEST): rationale and design of the trial. Schizophr Res. 2005;78(2–3):147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frangou S, Sachpazidis I, Stassinakis A, Sakas G. Telemonitoring of medication adherence in patients with schizophrenia. Telemed J E-Health. 2005;11(6):675–683. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2005.11.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Frank AF, Gunderson JG. The role of the therapeutic alliance in the treatment of schizophrenia: relationship to course and outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:228–236. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810150028006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Freudenreich O, Cather C, Evins AE, Henderson DC, Goff DC. Attitudes of schizophrenia outpatients toward psychiatric medications: relationship to clinical variables and insight. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1372–1376. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gaebel W, Janner M, Frommann N, et al. First vs multiple episode schizophrenia: two-year outcome of intermittent and maintenance medication strategies. Schizophr Res. 2002;53:145–159. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00182-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gaebel W, Pietzcker A. One-year outcome of schizophrenic patients: the interaction of chronicity and neuroleptic treatment. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1985;18:235–239. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1017372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Garavan J, Browne S, Gervin M, Lane A, Larkin C, O'Callaghan E. Compliance with neuroleptic medication in outpatients with schizophrenia: relationship to subjective response to neuroleptics; attitudes to medication and insight. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39:215–219. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Garcia-Cabeza I, Gomez JC, Sacristan JA, Edgell E, Gonzalez de Chavez M. Subjective response to antipsychotic treatment and compliance in schizophrenia: a naturalistic study comparing olanzapine, risperidone and haloperidol (EFESO Study) BMC Psychiatry. 2001;1:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gilmer TP, Dolder CR, Lacro JP, et al. Adherence to treatment with antipsychotic medication and health care costs among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:692–699. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Giron M, Gomez-Beneyto M. Relationship between family attitudes measured by the semantic differential and relapse in schizophrenia: a 2 year follow-up prospective study. Psychol Med. 1995;25:365–371. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700036266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Giron M, Gomez-Beneyto M. Relationship between empathic family attitude and relapse in schizophrenia: a 2-year follow-up prospective study. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24:619–627. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Glick ID, Clarkin JF, Haas GL, Spencer JH, Jr, Chen CL. A randomized clinical trial of inpatient family intervention: VI. mediating variables and outcome. Fam Process. 1991;30:85–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1991.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Glick ID, Berg PH. Time to study discontinuation, relapse, and compliance with atypical or conventional antipsychotics in schizophrenia and related disorders. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;17:65–68. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Godleski LS, Goldsmith LJ, Vieweg WV, Zettwoch NC, Stikovac DM, Lewis SJ. Switching from depot antipsychotic drugs to olanzapine in patients with chronic schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:119–122. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gray R, Wykes T, Edmonds M, Leese M, Gournay K. Effect of a medication management training package for nurses on clinical outcomes for patients with schizophrenia: cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:157–162. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Green JH. Frequent rehospitalization and noncompliance with treatment. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988;39:963–966. doi: 10.1176/ps.39.9.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grunebaum MF, Weiden PJ, Olfson M. Medication supervision and adherence of persons with psychotic disorders in residential treatment settings: a pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:394–399. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n0515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grunebaum M, Aquila R, Portera L, Leon AC, Weiden P. Predictors of management problems in supported housing: a pilot study. Community Ment Health J. 1999;35:127–133. doi: 10.1023/a:1018768614068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guimâon J. The use of group programs to improve medication compliance in patients with chronic diseases. Patient Educ Couns. 1995;26:189–193. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(95)00732-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hamera E, Schneider JK, Deviney S. Alcohol, cannabis, nicotine, and caffeine use and symptom distress in schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995;183:559–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hayward P. Medication self-management: a preliminary report on an intervention to improve medication compliance. J Ment Health. 1995;4:511–518. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hertling I, Philipp M, Dvorak A, et al. Flupenthixol versus risperidone: subjective quality of life as an important factor for compliance in chronic schizophrenic patients. Neuropsychobiology. 2003;47:37–46. doi: 10.1159/000068874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hodgins S, Tiihonen J, Ross D. The consequences of conduct disorder for males who develop schizophrenia: associations with criminality, aggressive behavior, substance use, and psychiatric services. Schizophr Res. 2005;78:323–335. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hoffmann H. Age and other factors relevant to the rehospitalization of schizophrenic outpatients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;89:205–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb08093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hogan TP, Awad AG, Eastwood R. A self-report scale predictive of drug compliance in schizophrenics: reliability and discriminative validity. Psychol Med. 1983;13:177–183. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700050182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Holzinger A, Loffler W, Muller P, Priebe S, Angermeyer MC. Subjective illness theory and antipsychotic medication compliance by patients with schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190:597–603. doi: 10.1097/01.NMD.0000030524.45210.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hornung WP, Kieserg A, Feldman R, Buchkremer G. Psychoeducational training for schizophrenic patients: background, procedure, and empirical findings. Patient Educ Couns. 1996;29:257–268. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(96)00918-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hunt GE, Bergen J, Bashir M. Medication compliance and comorbid substance abuse in schizophrenia: impact on community survival 4 years after a relapse. Schizophr Res. 2002;54:253–264. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ito J, Oshima I. Distribution of EE and its relationship to relapse in Japan. Int J Ment Health. 1995;24:23–37. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jarobe KS, Schartz SK. The relationship between medication noncompliance and cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 1999;5:S2–S8. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jerrell JM. Cost-effectiveness of risperidone, olanzapine, and conventional antipsychotic medications. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28:589–605. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jeste SD, Patterson TL, Palmer BW, Dolder CR, Goldman S, Jeste DV. Cognitive predictors of medication adherence among middle-aged and older outpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2003;63:49–58. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Joyce AT, Harrison DJ, Loebel AD, Ollendorf DA. Impact of atypical antipsychotics on outcomes of care in schizophrenia. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(8suppl):S254–S261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kamali M, Kelly BD, Clarke M, et al. A prospective evaluation of adherence to medication in first episode schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2006;21:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kamali M, Kelly L, Gervin M, Browne S, Larkin C, O'Callaghan E. Psychopharmacology: insight and comorbid substance misuse and medication compliance among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:161–166. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kamali M, Kelly L, Gervin M, Browne S, Larkin C, O'Callaghan E. The prevalence of comorbid substance misuse and its influence on suicidal ideation among in-patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101:452–456. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.101006452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kampman O, Kiviniemi P, Koivisto E, et al. Patient characteristics and diagnostic discrepancy in first-episode psychosis. Compr Psychiatry. 2004;45(3):213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kampman O, Laippala P, Vaananen J, et al. Indicators of medication compliance in first-episode psychosis. Psychiatr Res. 2002;110:39–48. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kapur S, Ganguli R, Ulrich R, Raghu U. Use of random-sequence riboflavin as a marker of medication compliance in chronic schizophrenics. Schizophr Res. 1992;6:49–53. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(91)90020-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kashner TM, Rader LE, Rodell DE, Beck CM, Rodell LR, Muller K. Family characteristics, substance abuse, and hospitalization patterns of patients with schizophrenia. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1991;42:195–196. doi: 10.1176/ps.42.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kelly GR, Mamon JA, Scott JE. Utility of the health belief model in examining medication compliance among psychiatric outpatients. Soc Sci Med. 1987;25:1205–1211. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kelly GR, Scott JE. Medication compliance and health education among outpatients with chronic mental disorders. Med Care. 1990;28:1181–1197. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199012000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kemp R, Hayward P, Applewhaite G, Everitt B, David A. Compliance therapy in psychotic patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1996;312:345–349. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7027.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]