Abstract

Cognitive deficits in people with schizophrenia are associated with poor functioning and lower quality of life. Because few studies have examined their relationship with service use or costs, it is unclear whether effective cognitive remediation interventions have potential for economic impacts. This study examined associations between cognition and costs among people with schizophrenia. Baseline data collected between 1999 and 2002 from a randomized controlled trial of cognitive remediation therapy were analyzed. A total of 85 participants were recruited from a London mental health trust if they had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, evidence of cognitive/social functioning difficulties, and at least 1 year since first contact with psychiatric services. Cognition levels, social functioning, symptoms, sociodemographic characteristics, and retrospective use of health/social care and other resources were measured. Average public sector costs were estimated to be £15 078 ($23 824) for a 6-month period. Associations between health/social care costs and type and severity of cognition were examined using structural equation models. No significant relationships were found between cognition and costs in a model based on 3 independent constituent components of cognition (cognitive shifting, verbal working memory, and response inhibition), although a model with covarying cognition components fitted the observed data well. A model with cognition as a single construct both fitted well and showed a significant relationship. In people with schizophrenia and severe cognitive impairment, improvements in either overall cognition or specific cognitive components may impact on costs. Further investigation in larger samples is needed to confirm this finding and to explore its generalizability to those with less severe deficits.

Keywords: service utilization, structural equation models, remediation

Introduction

Cognitive deficits in people with schizophrenia are associated with poor functioning and lower quality of life. There are associations between symptoms and community functioning,1 so treatment has generally focused on reducing positive, negative, and depressive symptoms of schizophrenia. However, growing attention is now being paid to cognitive deficits2,3 because they may be more directly related to functioning outcomes4,5,6 and predictive of future care.5 Although there has been a growth in the development of psychological interventions to improve cognition levels for people with severe mental illness, there is a lack of information about the relationship between cognitive deficit levels and costs. It is therefore unclear whether such interventions have the potential to impact upon the costs of care.

It is widely acknowledged that people with schizophrenia make heavy use of inpatient and community-based services. In an epidemiological study of people with psychoses in London, the rate of ever having being admitted to hospital for psychiatric problems was 94%, and 13% had an inpatient stay of greater than 1 year.7 Although heavy use of services may be entirely appropriate for managing the illness, there is, nevertheless, an increasing pressure to contain costs and use budgets as effectively as possible. If dependence on services could be reduced while maintaining or improving patient health and quality of life, there could be greater benefit to the health system and to society overall. Cognition has been shown to be associated with social functioning, community functioning, and work,2,8,9 but few studies have examined its relationship with service utilization or costs. Although the nature, pattern, and strength of any relationships between cognition and costs are likely to vary across different geographical settings due to variations in factors such as health care systems, social support systems, and demographics, it would, nevertheless, be valuable to identify whether any broad relationships are present.

This study set out to estimate public sector costs for people with schizophrenia with cognitive difficulties and to examine the relationship between cognition and health and social care costs. Previous studies of correlates of cognition (more generally) in people with schizophrenia have commonly reported cognition as a single summary measure or examined performance on a variety of tests that measure a number of cognitive functions in a nonspecific way.10 Consequently, findings have tended not to be specific about the constituent cognitive processes that may be important. This study differs firstly by examining factors that isolate specific cognitive processes and secondly by examining their relationship with costs.

METHOD

Participants and Setting

Participants were recruited to a randomized controlled trial of cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) vs standard care. Data in this article are from baseline assessments conducted prior to randomization. Inclusion criteria were diagnosis of schizophrenia based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV); evidence of some cognitive difficulties (scored at least 1 SD below the normative mean on the Rivermead Behavioral Memory Test,11 the Hayling and Brixton Tests,12 or the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test13); evidence of social functioning problems (scored at least one problem on the Social Behavior Schedule [SBS]14); estimated premorbid IQ > 65; and at least 1 year since first contact with psychiatric services. Written informed consent was obtained, and the study protocol was approved by the Institute of Psychiatry/South London and Maudsley National Health Service Trust Ethical Committee.

Data Collection

Graduate research psychologists collected individual-level data on a range of outcome measures through face-to-face interviews. Economic studies are likely to be of greater use to policy makers if they obtain the broadest possible perspective on costs; because people with schizophrenia were likely to make use of a broad range of services provided by a range of different agencies, it would have been infeasible to gather information from all service providers given the lack of comprehensive electronic records (such as insurance claims data in the United States) in the United Kingdom. Therefore, data were collected from health care staff and records and from self-reports by participants, using the Client Sociodemographic and Service Receipt Inventory.15 This covered questions about participants' current demographic profile, living situation, employment status, and income plus lost days from work, use of health, social care and criminal justice system resources, and social security benefits received for a retrospective 6-month period. The reliability of service utilization reports by people with mental health problems is generally encouraging. Mirandola et al16 compared total costs derived from 2 methods of collecting service use data for a range of psychiatric services, a self-report schedule, and a psychiatric case register. Although there was poor agreement about individual service components, there was good agreement between the 2 methods in terms of total service costs.

Costs

Unit costs were combined with individual-level resource volumes to obtain a cost per participant. Unit costs for health and social care services were based on UK national estimates in Netten et al,17 adjusted to reflect higher costs in London. Medication costs were based on prices reported by the Joint Formulary Committee.18 Specialist education services costs were estimated from Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy19 statistics. Social security benefit rates were obtained from the UK Department for Work and Pensions.20 Police contact costs were estimated from Finn et al.21 Unit costs were standardized to 2000/2001 prices. All costs are reported as mean values over 6 months in pounds sterling (£). Costs are also reported in US dollars ($) based on a 2001 purchasing power parity conversion rate of £1 = $1.5822 which equalizes the purchasing power of different currencies.

Cognition Measures

Cognition was assessed using 11 components (from the instruments listed below). In the structural equation models (SEMs) (described below), these were categorized into 3 domains (cognitive shifting, verbal working memory, and response inhibition) based on the factor structure suggested by an exploratory factor analysis in a previous study.23

Cognitive Shifting

Trail-Making Test24: time taken for part B.

Behavioral Assessment for Dysexecutive Syndrome (BADS)25: Zoo-Map Test, total raw score.

BADS: Key-Search, total raw score.

Spatial Response Inhibition Test26: median time taken in incompatible response condition minus simple reaction time.

Stroop Neuropsychological Screening Test27: Color-Word Task, number correct in 120 seconds.

Verbal Working Memory

Response Inhibition

Statistical Analysis

SEMs were used to explore relationships between cognition factors and costs because these allow the exploration of complex patterns in data. This method involves developing a theoretical model to specify causal relationships (which are represented using a path diagram) and testing these hypotheses by exploring how well the theoretical model explains the pattern of intercorrelations in a set of variables.31 Parameters in a model are estimated so that the covariance (or correlation) matrix of the observed variables, as predicted by the model, is as close as possible to the observed covariance matrix of these variables.32 Amos 5.0 (Analysis of MOment Structures)33 was used to fit the models. The extent to which the theoretical model fitted the data was quantified using the following goodness of fit statistics: (1) chi-square (χ2) values with associated P value (which should not be significant if there is a good model fit), (2) the goodness of fit index which identifies the absolute model fit, and (3) the comparative fit index which compares the performance of the specified models to the performance of a baseline (“null” or “independence”) model. Values for the latter 2 indices can vary from 0 to 1. Here, values >0.8 were considered to be consistent with an acceptable model fit.

SEMs were fitted to the observed correlation values of the variables to examine the relationship between cognition and health and social care costs. Cognition was explored using 3 approaches. Firstly, cognition variables were categorized into 3 latent variables, based on the factor structure suggested by an exploratory factor analysis in a previous study.23 The 3 latent variables represented cognitive shifting, verbal working memory, and response inhibition. This first model explored the independent effects of each cognition factor by assuming no relationship between them. An additional model in which the 3 cognition factors were allowed to covary was then explored. Finally, all 11 cognition variables were represented through a single latent variable, in keeping with previous studies that have used a single summary measure for cognition. Total health and social care costs were represented as a single observed variable.

To control for the effects of social behavior and symptomology, 4 further variables were added: the social withdrawal and antisocial behavior scores from the SBS14 and the total positive symptoms and depression items scores from the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).34 Demographic factors (age, gender, marital status, and ethnicity) were not associated with costs and were thus excluded to avoid unnecessarily reducing the power of the models.

Therefore, a total of 15 observed variables related to cognition, social behavior, and symptomology were included in the analyses. Where relevant, these were transformed (multiplied by −1) so that higher scores in all variables indicated better cognition/social behavior/symptoms. To reflect the different configurations of the variables of interest, 3 different models were developed.

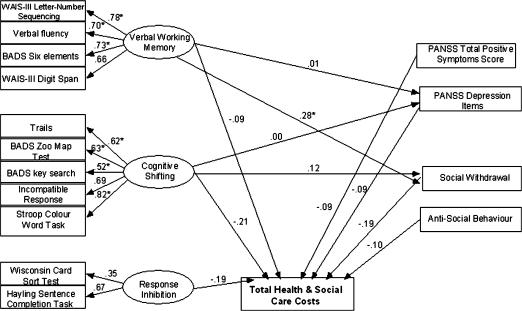

Observed cost variable with 3 independent latent cognition variables (Model 1; figure 1).

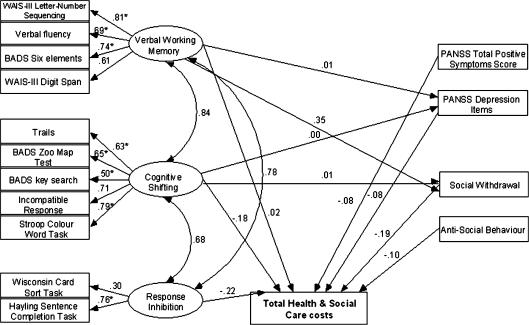

Observed cost variable with 3 covarying latent cognition variables (Model 2; figure 2).

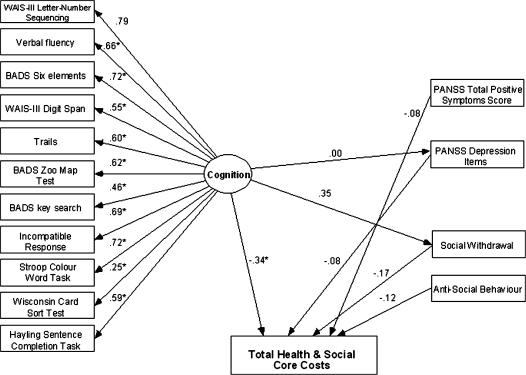

Observed cost variable with 1 latent cognition variable (Model 3; figure 3).

Path diagrams representing hypothesized relationships in each of these models are shown in figures 1–3. These models were exploratory and empirically based.

Fig. 1.

Model 1—Path Diagram for Model With 3 Independent Latent Cognition Variables. *Significant at the .05 level.

Fig. 2.

Model 2—Path Diagram for Model With 3 Covarying Latent Cognition Variables. *Significant at the .05 level.

Fig. 3.

Model 3—Path Diagram for Model With 1 Latent Cognition Variable. *Significant at the .05 level.

Descriptive data are based on available cases for each item and are for the full sample unless otherwise stated. Total costs were computed only for those cases with complete data across all cost items. A total of 14 of the 85 cases had some missing data on the cognition, social behavior, symptomology, or cost variables, reducing the available sample for the SEMs to 71. Missing values for cognition, social behavior, and symptomology variables were imputed for 8 cases to increase the number of cases available for the SEMs to 79. Imputation was carried out using the regression method imputation function in SPSS, based on all cognition, social behavior, and symptomology variables included in the models. The remaining 6 cases had missing data for total health and social care costs and were excluded from the SEMs because there was no reasonable basis on which to impute missing values. These 6 excluded cases were different to those included: they were older (mean age of 41 years vs 36 years), more likely to be female (50% vs 25%), had a lower total PANSS score (mean of 50 vs 61), and a lower total SBS score (mean of 4 vs 13). Because costs were correlated with PANSS and SBS scores, such a profile would suggest that the excluded cases were likely to have had lower costs than those included in the SEMs. However, data for accommodation costs (the largest cost driver) were available for 5 out of the 6 excluded cases and in fact showed slightly higher costs than for those included in the SEMs (£11 780 vs £9269).

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics, Cognition, and Social Functioning

A total of 85 participants were recruited to the study of which males were 62 (74%) (sample = 84), and the average age was 36 years. Singles were 80 (94%) (including divorced, separated, and widowed), and only 5 (6%) were married. White ethnicity participants were 38 (45%), with the remaining being black Caribbean (13; 16%), black African (4; 5%), black other (7; 8%), Indian (9; 11%), and other (13; 16%) (sample = 84). Table 1 reports mean scores for each of the cognition, SBS, and PANSS measures.

Table 1.

Mean Cognition, Social Functioning and Symptomology Scoresa for Participants Included in the Structural Equation Models (n = 79)

| Mean | SD | |

| Cognition | ||

| Trails | −179.16 | 138.98 |

| BADS Zoo-Map Test | 5.19 | 9.27 |

| BADS Key-Search | 8.34 | 6.02 |

| Spatial Response Inhibition Test | −1287.16 | 818.18 |

| Stroop Neuropsychological Screening Test | 70.50 | 25.73 |

| WAIS-III Letter-Number Sequencing | 6.60 | 3.12 |

| Controlled Oral Word Association Test | 26.94 | 10.66 |

| BADS Six Elements | 3.59 | 1.74 |

| WAIS-III Digit Span | 14.63 | 3.96 |

| Wisconsin Card Sorting Test | −39.24 | 25.80 |

| Hayling Sentence Completion Task | −21.29 | 19.97 |

| Social Behavior Schedule | ||

| Thought disturbance | 2.57 | 2.52 |

| Antisocial behavior | 0.80 | 1.53 |

| Depressed behavior | 0.82 | 1.06 |

| Social withdrawal | 3.57 | 3.37 |

| Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale | ||

| Total positive symptoms score | −13.45 | 5.32 |

| Depression items score | −1.58 | 1.10 |

Note: BADS, Behavioral Assessment for Dysexecutive Syndrome; WAIS-III, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Third Edition.

Where relevant, these variables were multiplied by −1 so that higher scores in all variables indicated better cognition/social behavior/symptoms.

Education, Employment, Income, and Living Arrangements

Participants had received an average of 11.5 years of schooling (sample = 83). Only 4 people had not completed secondary education, whereas 18 (22%) had completed further or tertiary education (sample = 82). Only 8 were in paid, voluntary, or sheltered employment (sample = 84). Of the 3 participants in paid employment, 1 had taken time off work due to illness in the previous 6 months, totalling 40 days off work. Of the 71 participants classified as unemployed, all but 1 had been unemployed for the entire 6-month assessment period. A total of 81 (96%) people were in receipt of state social security benefits (sample = 84), and 76 (91%) reported benefits to be their main source of income (sample = 84). Productivity losses associated with unemployment and time off work are excluded from the calculation of total societal costs to avoid double-counting social security benefit claims that may be associated with being out of work. A total of 17 (20%) people lived alone (with or without children), 4 (5%) with a spouse (with or without children), 17 (20%) with parents, and 46 (55%) with others (sample = 84). A total of 39 (47%) participants were living in domestic housing (owner occupied, privately rented, or rented from local authorities/housing associations).

Resource Use and Costs

A total of 45 (54%) participants described their usual place of living as a hospital or other specialized accommodation facility. Of these, the majority were either in a hospital psychiatric rehabilitation ward or a 24-hour–staffed facility.

Only one nonpsychiatric inpatient episode was reported (Table 2). Use of hospital outpatient services was modest except for 3 participants who had an average of 55 day hospital attendances each over 6 months. Day care centers were the most commonly used community-based day service, used by over a third of the group, with an average of 50 attendances each over 6 months (in the United Kingdom, day care centers are usually drop-in facilities which focus on providing advice and support and an environment for socializing and recreation, rather than treatment). Community mental health centers were used by a quarter of participants, at an average rate of 16 attendances each. The most commonly used primary and community care services were psychiatrist (74%), community psychiatric nurse (65%), and social worker (32%). A total of 3 people who had assistance from a home help or a care worker had on average 70 contacts each. The most widely used medication was clozapine, used by 29 (36%) participants. Only one person reported receiving no medications over the 6-month period. Contacts with criminal justice system services were rare—one person had spent one night in a police cell.

Table 2.

Use of Health and Social Care Services in Previous 6 Months

| Inpatient servicesa | Number (%) Who Used Service | Mean Number of Admissionsb | Mean Number of Daysb |

| Emergency/crisis center (n = 84) | 0 | ||

| General medical ward (n = 84) | 1 (1.2) | 1 | 4 |

| Other (n = 84) | 0 | ||

| Outpatient services | Number (%) who used service | Mean number of attendancesb | |

| Psychiatric outpatient visit (n = 83) | 16 (19.3) | 4.5 | |

| Other hospital outpatient visit (n = 83) | 6 (7.2) | 1.3 | |

| Day hospital (n = 83) | 3 (3.6) | 55 | |

| Other (n = 83) | 2 (2.4) | 9 | |

| Community-based day services | Number (%) who used service | Mean number of attendancesb | |

| Community mental health center (n = 83) | 21 (25.3) | 15.6 | |

| Day care center (n = 83) | 30 (36.1) | 50.4 | |

| Group therapy (n = 83) | 7 (8.4) | 14.3 | |

| Sheltered workshop (n = 83) | 2 (2.4) | 84 | |

| Specialist education (n = 83) | 7 (8.4) | 22.6 | |

| Other (n = 83) | 1 (1.2) | 24 | |

| Primary and community care services | Number (%) who used service | Mean number of attendancesb | |

| Psychiatrist (n = 82) | 61 (74.4) | 5.6 | |

| Psychologist (n = 82) | 13 (15.9) | 7.3 | |

| General practitioner (n = 82) | 18 (22.0) | 3.9 | |

| District nurse (n = 82) | 0 | ||

| Community psychiatric nurse/case manager (n = 82) | 53 (64.6) | 14.2 | |

| Social worker (n = 82) | 26 (31.7) | 7.3 | |

| Occupational therapist (n = 82) | 15 (18.3) | 28.4 | |

| Home help/care worker (n = 82) | 3 (3.7) | 70.3 | |

| Other (n = 82) | 8 (9.8) | 27.8 |

In order to avoid double-counting, stays in the following types of wards are not reported here due to inseparability from specialized accommodation reported as “usual living situation”: acute psychiatric ward, psychiatric rehabilitation ward, and long-stay ward.

Mean calculation based on users only.

Costs associated with these resources are given in Table 3. After adding the value of social security benefits claimed and criminal justice system costs, average total societal costs were £15 078 ($23 824) for a 6-month period. No participants had zero costs. Specialized accommodation costs dominated all other costs (62% of total societal costs and 73% of health and social care costs).

Table 3.

Public sector costs over 6 months, 2000/2001 prices

| Mean |

SD |

|||

| £ | $ | £ | $ | |

| Specialized/inpatient accommodationa | ||||

| Total (n = 84) | 9418.88 | 14 882 | 10 436 | 16 489 |

| Other inpatient services | ||||

| Emergency/crisis center (n = 84) | 0 | |||

| General medical ward (n = 84) | 11.52 | 18 | 106 | 167 |

| Other (n = 84) | 0 | |||

| Total (n = 84) | 11.52 | 18 | 106 | 167 |

| Outpatient services | ||||

| Psychiatric (n = 83) | 111.04 | 175 | 304 | 480 |

| Other outpatient specialties (n = 83) | 7.13 | 11 | 30 | 47 |

| Day hospital (n = 83) | 135.18 | 214 | 709 | 1120 |

| Other (n = 83) | 16.05 | 25 | 108 | 171 |

| Total (n = 83) | 269.40 | 426 | 763 | 1206 |

| Community-based day services | ||||

| Community mental health center (n = 83) | 276.68 | 437 | 756 | 1194 |

| Day care center (n = 83) | 595.15 | 940 | 1363 | 2154 |

| Group therapy (n = 83) | 13.72 | 22 | 62 | 98 |

| Sheltered workshop (n = 83) | 35.73 | 56 | 249 | 393 |

| Specialist education (n = 83) | 39.12 | 62 | 156 | 246 |

| Other (n = 83) | 2.33 | 4 | 21 | 33 |

| Total (n = 83) | 962.72 | 1521 | 1552 | 2452 |

| Primary and community care services | ||||

| Psychiatrist (n = 82) | 329.54 | 521 | 704 | 1112 |

| Psychologist (n = 82) | 76.75 | 121 | 275 | 435 |

| General practitioner (n = 82) | 25.90 | 41 | 126 | 199 |

| District nurse (n = 82) | 0 | |||

| Community psychiatric nurse/case manager (n = 82) | 337.24 | 533 | 841 | 1329 |

| Social worker (n = 82) | 142.13 | 225 | 406 | 641 |

| Occupational therapist (n = 82) | 244.24 | 386 | 1061 | 1676 |

| Home help/care worker (n = 82) | 22.80 | 36 | 146 | 231 |

| Other (n = 82) | 135.23 | 214 | 853 | 1348 |

| Total (n = 82) | 1313.82 | 2076 | 2058 | 3252 |

| Medications | ||||

| Total (n = 81) | 890.65 | 1407 | 655 | 1035 |

| Social security benefits | ||||

| Total (n = 84) | 2243.43 | 3545 | 1228 | 1940 |

| Criminal justice system services | ||||

| Total (n = 83) | 0.65 | 1 | 6 | 9 |

| Total (n = 79) | 15 078.39 | 23 824 | 10 961 | 17 318 |

Includes stays in staffed and unstaffed overnight facilities, acute psychiatric wards, psychiatric rehabilitation wards, and long-stay psychiatric wards.

Relationships Between Costs and Cognition

Table 4 presents goodness of fit statistics for the 3 models. The path coefficients (ie, regression loadings of one variable on another) are provided within the path diagrams (figures 1–3). Those significant at the .05 level are asterisked. No significant relationships were found between cognition and costs in the model that represented cognition through 3 independent latent variables (Model 1; figure 1), and the overall model was not a good fit. However, after accounting for the relationships between the 3 latent cognition variables (Model 2; figure 2), the model fitted well (as indicated by the higher goodness of fit indices, the lower χ2 value, and the nonsignificant-associated P value). Although the relationships between the cognition factors and costs were not significant, the model suggests differences between the 3 cognition factors in their relationship with costs: response inhibition had the greatest loading on costs (−0.22), and the association between verbal working memory and costs was positive (ie, better verbal working memory is associated with higher costs). Finally, in keeping with other studies of correlates of cognition, we examined a model with cognition as a single latent variable (Model 3; figure 3). Goodness of fit indices suggest that this model also fitted the observed data well, although not as well as Model 2. However, the estimated regression coefficient of overall cognition on cost in this equation was greater (−0.34) and was significant, indicating that participants with higher (better) cognition scores tended to have lower costs. It should be noted that the power of the tests are low, given the small number of participants. Statistical comparisons of the fit of the 3 models confirmed that both Models 2 and 3 were a better fit (P < .0001 for both comparisons) compared with Model 1 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Goodness of Fit Statistics for Structural Equation Models

| Goodness of Fit Index | Comparative Fit Index | χ2 | df | P | |

| Model 1: 3 independent latent cognition variables | 0.779 | 0.779 | 186.903 | 98 | <.0001 |

| Model 2: 3 covarying latent cognition variables | 0.866 | 0.866 | 107.891 | 95 | .1726 |

| Model 3: 1 latent cognition variable | 0.851 | 0.851 | 120.703 | 102 | .0997 |

| Comparisons of model fit | |||||

| Model 1 vs Model 2 | <.0001 | ||||

| Model 1 vs Model 3 | <.0001 | ||||

| Model 2 vs Model 3 | .0768 |

Discussion

Schizophrenia patients with severe cognitive deficits are cared for in a wide variety of settings at a considerable cost. As reported previously from an international review,35 accommodation formed the largest component in total care costs. Few studies of people with schizophrenia have measured such a wide range of costs, and this is the first study to explore their relationship to cognitive deficits in terms of the constituent factors of cognition.

None of the 3 cognition factors were independently related to costs. A model which accounted for the covariance between the cognitive factors fitted the data better but did not show significant relationships with costs. Cognition as a single construct showed an association with costs, although this model did not fit the data as well as the model with 3 covarying cognitive factors. The fact that response inhibition had the greatest loading on costs may suggest this to be an appropriate target for interventions if it was necessary to focus on specific aspects of cognition. However, the strong correlations between the cognition factors suggest that improving any one of the 3 cognitive factors may lead to improvements in the others and, therefore, additionally impact on costs indirectly.

However, it would be necessary to further explore whether there is a direct relationship between cognition and costs, or whether other factors, such as social behavior and symptoms, mediate this relationship. Evaluations of the cost-effectiveness of interventions that aim to improve cognition would also need to include factors that mediate the relationship between cognition and social functioning36 because this may in turn impact on costs. The relationship between cognition and costs in this study is unlikely to be accounted for by the social behavior variables because these had little variance. Additionally, given that PANSS symptom variables were correlated with SBS variables, it is also unlikely that symptomology accounts for the relationship. However, it may be relevant to include disorganization factors; in future studies this has been shown to correlate with several cognitive deficits37 and to relate to community functioning.1

The study was based on people with particularly severe cognitive difficulties. Although it was a group of people for whom poor cognitive functioning probably contributes most to outcome, the range of values in the cognition variables may not have been sufficiently broad to discriminate well between different cognitive functions and to demonstrate any strong relationships. It should also be noted that although the cost of health and social care is important from a funding perspective, using total costs as a summary measure may conceal important patient-centered effects such as changes in care patterns which have no net effect on total costs. Also, low costs cannot always be interpreted as beneficial to the individual and should thus be considered alongside the individual's quality of life and functioning. A previous exploratory study provides examples of both of these points. It showed that CRT and control groups had similar reductions in care costs over time, but CRT patients had significantly higher day care costs.38 Greater use of day care possibly confers further advantages, eg, better social functioning and quality of life. Therefore, a more appropriate approach may be to focus on how resources within a fixed budget are allocated and whether they are targeted at the services and treatments that are more likely to maximize relevant outcomes.

The study had some limitations. Firstly, although the sample was one of the largest reported data sets of schizophrenia patients with cognitive difficulties, it was not large enough for some of the asymptotic results of structural equation modeling to be strictly valid. For example, the ratio of model parameters to subjects may have been insufficient. The small sample size may have contributed to the finding of no relationships between costs and some of the behavioral, symptomology, and demographic factors. Skewness in the cost variable may also have contributed to imprecision of the coefficient estimates. Therefore, the results have to be interpreted with some caution. Secondly, it may be possible that specific cognitive functions are associated with specific aspects of care, but because our models examined the total costs of a range of services (as total costs provide a useful summary measure of highly variable service use profiles), such associations were undetected. Thirdly, the possibility of measurement error in the cost data cannot be ruled out due to the use of self-reported resource use data. However, the presence and/or effects of this are unclear. Finally, variations in national, local, and patient-level factors across different countries can lead to differences in relationships between treatment patterns, costs, and clinical outcomes. Therefore, the costs reported here, and their relationship with cognition, may not be applicable to other health care systems/settings.

The ongoing trial from which these baseline data came aims to determine whether CRT reduces cognitive deficit levels and costs. These data suggest that there may be potential for improvements in overall cognition, or even in one aspect of cognition, to impact upon health and social care costs.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the UK Department of Health, grant code RFG 757.

References

- 1.Norman RMG, Malla AK, Cortese L, et al. Symptoms and cognition as predictors of community functioning: a prospective analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:400–405. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.3.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey PD, Howanitz E, Parrella M, et al. Symptoms, cognitive functioning, and adaptive skills in geriatric patients with lifelong schizophrenia: a comparison across sites. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1080–1086. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.8.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson M, Keefe RSE. Cognitive impairment as a target for pharmacological treatment in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1995;17:123–129. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(95)00037-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:119–136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wykes T, Dunn G. Cognitive deficit and the prediction of rehabilitation success in a chronic psychiatric group. Psychol Med. 1992;22:389–398. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700030336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mueser KT, Bellack AS, Douglas MS, Wade JH. Prediction of social skill acquisition in schizophrenic and major affective disorder patients from memory and symptomatology. Psychiatry Res. 1991;37:281–296. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(91)90064-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCrone P, Thornicroft G, Phelan M, Holloway F, Wykes T, Johnson S. Utilisation and costs of community mental health services. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:391–398. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.5.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans JD, Bonda GR, Meyer PS, et al. Cognitive and clinical predictors of success in vocational rehabilitation in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;70:331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGurk R, Mueser KT. Cognitive functioning and employment in severe mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191:789–798. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000100921.31489.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Velligan DI, Bow-Thomas CC, Mahurin RK, Miller AL, Halgunseth LC. Do specific neurocognitive deficits predict specific domains of community function in schizophrenia? J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188:518–524. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200008000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson B, Cockburn J, Baddeley A, Hiorns R. The development and validation of a test battery for detecting and monitoring everyday memory problems. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1989;11:855–870. doi: 10.1080/01688638908400940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burgess PW, Shallice T. Hayling and Brixton Tests. Bury St Edmunds, UK: Thames Valley Test Company; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grant DA, Berg EA. A behavioural analysis of degree of reinforcement and ease of shifting to new responses in a Weigl-type card sorting problem. J Exp Psychol. 1948;38:404–411. doi: 10.1037/h0059831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wykes T, Sturt E. Social behaviour schedule [SBS] In: Wade DT, editor. Measurement in Neurological Rehabilitation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1992. pp. 283–284. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chisholm D, Knapp MRJ, Knudson HC, et al. Client socio-demographic and service receipt inventory—European version: development of an instrument for international research. EPSILON study 5. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;39(suppl):s28–s33. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.39.s28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mirandola M, Bisoffi G, Bonizzato P, Amaddeo F. Collecting psychiatric resources utilisation data to calculate costs of care: a comparison between a service receipt interview and a case register. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:541–547. doi: 10.1007/s001270050173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Netten A, Rees T, Harrison G. Unit Costs of Health and Social Care. Canterbury, Kent: University of Kent at Canterbury, PSSRU; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary, 44th edition. London, England: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; 2002. Sep, [Google Scholar]

- 19.CIPFA. Education Statistics 1999–2000 Actuals. London, England: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department for Work and Pensions. Benefits and services. 2003. Available at: http://www.dwp.gov.uk/lifeevent/benefits/index.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finn W, Hyslop J, Truman C. Mental Health Multiple Needs and the Police. London, England: 2000. Revolving Doors Agency. [Google Scholar]

- 22.OECD. Purchasing Power Parities. Comparative Price Levels. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reeder C, Newton E, Frangou S. Schizophr Bull. Vol. 30. 2004. Wykes T. Which executive skills should we target to affect social functioning and symptom change? A study of a cognitive remediation therapy program; pp. 87–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reitan RM. Validity of the Trail-Making Test as an indication of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills. 1958;8:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson BA, Alderman N, Burgess PW, Emslie H, Evans JJ, editors. Behavioural Assessment of the Dysexecutive Syndrome. Bury St Edmunds, UK: Thames Valley Test; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wykes T, Sturt E, Katz R. The prediction of rehabilitative success after three years. The use of social, symptom and cognitive variables. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:865–870. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.6.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trenerry MR, Crosson B, DeBoe J, Leber WR. Stroop Neuropsychological Screening Test. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gold JM, Carpenter C, Randolph C, Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR. Auditory working memory and Wisconsin Card Sorting Test performance in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:159–165. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830140071013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benton AL, Hamsher K. Multilingual Aphasia Examination. Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wechsler D. Weschsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferguson E, James D, O'Hehir F, Sanders A. Pilot study of the roles of personality, references, and personal statements in relation to performance over the five years of a medical degree. Br Med J. 2003;326:429–432. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7386.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunn G, Everitt BS, Pickles A. Modelling Covariances and Latent Variables Using EQS. London, England: Chapman and Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 33.SPSS. Amos 5.0. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc.

- 34.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knapp M, Mangalore R, Simon J. The global costs of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30:279–293. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the “right stuff?”. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:119–136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phillips WA, Silverstein SM. Convergence of biological and psychological perspectives on cognitive coordination in schizophrenia. Behav Brain Sci. 2003;26:65–82. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x03000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wykes T, Reeder C, Williams C, Corner J, Rice C, Everitt B. Are the effects of cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) durable? Results from an exploratory trial in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2003;61:163–174. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]