Abstract

The rate of substance-use disorders in patients with mental illnesses within the psychotic spectrum, such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder, is higher than the rate observed in the general population and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Although there are currently 3 medications approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of alcohol dependence, no medications have been approved for the specific treatment of dually diagnosed patients. A small but growing body of literature supports the use of 2 of these medications, disulfiram and naltrexone, in dually diagnosed individuals. This article outlines a review of the literature about the use of disulfiram and naltrexone for alcoholism and in patients with comorbid mental illness. In addition, results are presented of a 12-week randomized clinical trial of disulfiram and naltrexone alone and in combination for individuals with Axis I disorders and alcohol dependence who were also receiving intensive psychosocial treatment. Individuals with a psychotic spectrum disorder, including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder, had worse alcohol outcomes than those without a psychotic spectrum disorder. Individuals with a psychotic spectrum disorder had better alcohol-use outcomes on an active medication compared with placebo, but there was no clear advantage of disulfiram or naltrexone or of the combination. Retention rates and medication compliance in the study were high and exceeded 80%. Pharmacotherapeutic strategies should take into account the advantages and disadvantages of each medication. Future directions of pharmacotherapeutic options are also discussed.

Keywords: psychosis, alcoholism, naltrexone, disulfiram, comorbidity, pharmacotherapy

Introduction

The rate of substance-use disorders in patients with mental illnesses within the spectrum of psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder, is higher than the rate observed in the general population1 and has been associated with increased psychotic symptoms,2 an increased rate of medication noncompliance,3,4 more frequent and longer hospitalizations,3 a higher rate of crisis-oriented service utilization, and consequently a higher cost of care.3,5 Social problems associated with substance abuse in these patients include legal entanglements,6 housing instability, lower rates of employment, and poor money management.2 After nicotine, the most common drug of abuse is alcohol. No medications have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the specific treatment of dually diagnosed patients, and research findings from relatively homogenous groups of alcoholics without comorbid disorders may not be applicable to this group of patients. Only a few controlled trials have evaluated the potential of various medications to treat these combined disorders.7–9

There are several reasons why patients with comorbid psychotic spectrum Axis I disorders may particularly benefit from effective medication treatments for their alcohol abuse. Alcohol-dependent patients with psychotic disorders may have greater reluctance to participate in treatment and self-help groups (such as Alcoholics Anonymous) where most members do not have comorbid psychiatric disorders.10 In addition, negative symptoms in psychotic disorders may undermine the patients' motivation, while cognitive symptoms may impair their ability to learn new material in psychosocial treatments. In contrast, pharmacological treatments are generally familiar to dually diagnosed patients and require less new learning than psychosocial treatments, and dose scheduling can be readily integrated into treatment. Therefore, research evaluating pharmacotherapies for dually diagnosed individuals may have a positive clinical impact in the treatment of these disorders.

Disulfiram

Disulfiram was the first medication approved by the FDA for treatment of alcohol dependence. Disulfiram alters normal metabolism of ingested alcohol to produce mildly toxic acetaldehyde, resulting in an aversive reaction characterized by vomiting, flushing, headache, and severe anxiety and rarely even death. This reaction is sufficiently strong that most individuals compliant with the medication completely stop drinking. This absolute prohibition of drinking is both the greatest strength and the greatest weakness of disulfiram.

Clinical studies do not clearly support the efficacy of disulfiram for the treatment of alcoholism in comparison with placebo.11 In fact, the largest study to date, a Veterans Affairs (VA) multisite cooperative study with more than 600 veterans, showed that disulfiram- and placebo-treated patients had similar outcomes.12 Compliance with the study medication (disulfiram and placebo) was the best predictor of positive outcome. Nevertheless, only 19% of the subjects were compliant with the medication. While this study has often been cited as undermining disulfiram's efficacy, it lacked any systematic procedures that have been demonstrated to enhance compliance such as supervised use, administration by a significant other, or behavioral contracting.13–16 Rejecting disulfiram's use in a clinical setting based on this study is premature. In fact, disulfiram is unique among agents for treatment of alcohol dependence in that it has the potential to foster complete abstinence. It may be especially useful in the abstinence initiation phase because it may eliminate impulsive alcohol use, and patients can time discontinuation around planned lapses or slips.

Clinical reports have suggested that disulfiram can precipitate a number of psychiatric symptoms, including delirium, depression, anxiety, mania, and psychosis.17 Disulfiram acts centrally by inhibiting dopamine beta-hydroxylase, resulting in an excess of dopamine and decreased synthesis of norepinephrine. This is the proposed mechanism of action for precipitation of psychotic and depressive symptoms.18 However, most clinical reports indicating psychiatric problems with disulfiram were collected before 1970 when medication dosages were higher than those used currently and the definitions of the psychiatric symptoms had not been standardized. Aside from these early clinical reports, there are a few recent, promising studies of the use of disulfiram in patients manifesting comorbid psychiatric disorders.17,19 In one naturalistic study of disulfiram in patients with dual disorders (including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, anxiety, and personality disorders), there were no reports of disulfiram worsening psychotic symptoms and disulfiram was thought to be a useful adjunct to appropriate psychiatric medications in the alcohol-use disorder population.19

Naltrexone

The μ-opioid antagonist naltrexone has been FDA approved for treatment of alcohol dependence since 1994. Naltrexone was tested in humans after preclinical studies suggested that opiate antagonists reliably reduce alcohol consumption under a variety of circumstances.20 The clinical benefits of naltrexone were first evaluated by Volpicelli et al,21 who used naltrexone as an adjunctive treatment to standard psychotherapy in a placebo-controlled, double-blind, study of 70 recently detoxified alcoholic volunteers. The results showed that naltrexone-treated individuals reported lower levels of alcohol craving, fewer drinks and drinking days, and lower rates of relapse than did placebo-treated patients. Volpicelli's initial findings were then replicated and extended by others.22,23 A meta-analysis of the placebo-controlled trials published from 1992 to 2000 concluded that naltrexone had a modest effect on drinking measures.24 Three aspects of naltrexone's effects have emerged from these and other studies: (a) it reduces craving or enhances the ability to maintain abstinence; (b) it alters the rewarding experience of intoxication; and (c) it reduces the priming effect of taking an initial drink, reducing the likelihood of relapse to heavy drinking. In addition, a few studies have suggested that “targeted” naltrexone, ie, naltrexone taken not in the traditional daily dosage as a relapse prevention but taken when experiencing craving, may be effective in reducing heavy drinking in nonabstinent individuals.25,26 In all these clinical studies, naltrexone was effective in the context of a standard effective psychosocial intervention. In a recently conducted large, multisite clinical trial, the Combining Medications and Behavioral Interventions (COMBINE) trial, comparing the efficacy of naltrexone, acamprosate, and behavioral treatments, naltrexone was shown to have a moderate effect on alcohol-use outcomes when prescribed with a behavioral intervention that is similar to primary care visits.27

There are negative studies as well.28,29 The largest negative study to date is a multisite VA cooperative trial of 627 alcohol-dependent veterans, in which there was no effect of naltrexone on the percentage of relapse days, drinking days, and drinks per drinking days.30 It has been hypothesized that the VA cooperative study results may not be generalizable to all patients manifesting alcohol dependence because the veterans were overwhelmingly male, older, and with longer duration of alcoholism than the subjects enrolled in previous trials with naltrexone.31 In addition, subjects manifesting comorbid major psychiatric disorders, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depression, and generalized anxiety disorders (GADs), were not excluded (patients with psychotic disorders were excluded) but did not receive psychotropics. In contrast, naltrexone was effective in reducing alcohol use in patients manifesting comorbid psychiatric disorders in another study where subjects were included but only if treated with psychotropic medications at stable doses for at least 3 months prior to randomization.32 Therefore, patients with better controlled psychiatric conditions may find naltrexone effective, or naltrexone may work synergistically with psychotropic medications in improving drinking outcomes.

A few other pilot studies have evaluated naltrexone in dually diagnosed patients. In a retrospective study on 72 psychiatric patients treated with naltrexone for alcohol-use disorders, 82% of them reduced significantly their drinking.33 Naltrexone decreased alcohol use and improved depressive symptoms in an open-label study with patients manifesting alcohol dependence.34 There is some evidence that clinicians who treat patients with these disorders do in fact preferentially prescribe medications to dually diagnosed individuals. In evaluating the utilization of naltrexone in the VA system nationally, despite a very low rate (2% of patients with alcohol dependence were prescribed naltrexone), the presence of a comorbid mental disorder was one of the clinical factors associated with an increase likelihood of being prescribed naltrexone.35

To our knowledge, we conducted the only controlled, randomized clinical trial with naltrexone in 31 patients manifesting schizophrenia and alcohol dependence.7 Naltrexone-treated patients had fewer drinking days and heavy drinking days and less craving in comparison with patients treated with placebo. Overall, naltrexone was well tolerated and did not cause a worsening of psychosis. The results of the study suggested naltrexone is safe and effective in conjunction with standard psychosocial and pharmacological treatments in patients manifesting schizophrenia. Further studies in patients with alcohol dependence and schizophrenia are currently underway.36,37

Disulfiram vs Naltrexone

We conducted a multicenter controlled trial of the efficacy of naltrexone and disulfiram alone and in combination in individuals (n = 254) with a heterogeneous set of comorbid mental disorders, many of whom were concurrently receiving pharmacotherapy for their symptoms.38 In this 12-week outpatient study, individuals were randomized to 1 of 4 groups: (1) naltrexone alone, (2) placebo alone, (3) disulfiram and naltrexone, or (4) disulfiram and placebo. There results showed that some, but not all, drinking outcomes were significantly better when assigned to any active medication vs placebo. There was no overall advantage of one medication over the other, and no advantage of the combination of both medications, although disulfiram had some surprising effects, including a positive effect on craving. There was a high rate of abstinence overall, with 177 (69.7%) of all subjects achieving “complete” abstinence during the 12-week trial. These medications, including the combination, had tolerable side effects consistent with those seen in nondually diagnosed patients.

A Report on the Effectiveness of Naltrexone and Disulfiram

The purpose of the present study was (1) to evaluate the relationship between the diagnosis of a psychotic spectrum disorder and treatment outcomes including alcohol use in response to disulfiram and naltrexone, alone and in combination; (2) to evaluate what effect these medications had on the symptoms of psychosis; and (3) to evaluate the relationship between psychosis and side effects and adverse events in response to disulfiram and naltrexone, alone and in combination. Because of the relatively small number of subjects who had schizophrenia alone, all subjects with disorders within the psychotic spectrum, including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder, were included for the purposes of this report. A model of “psychotic spectrum disorders” is supported by previous research,39 and the grouping of patients with different psychiatric disorders in a category of “severe and persistent mental illness” has been used to develop behavioral treatments for drug abuse.40 Both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder share pronounced and debilitating psychotic symptoms with devastating consequences and share similar treatments. These disorders are also clinically distinct from the psychiatric disorders most commonly found in samples, like ours,38 of alcohol-dependent individuals.

METHOD

Subjects

This study was approved by the Human Subjects Subcommittee of the VA Connecticut Healthcare System and the Northampton and Bedford, Mass, VAs. The present sample (n = 251, 3 subjects were dropped from the original sample for this report because of missing data) consisted of outpatients treated in clinics at these 3 VA sites, who met criteria for a current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) major Axis I disorder and alcohol dependence, determined by structured clinical interview,41 and who were abstinent no more than 29 days. The Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS)42 was also administered at baseline to characterize the severity of alcohol dependence. Those individuals on psychiatric medication were on a stable regimen (no changes) of psychiatric medication for at least 2 weeks prior to randomization. Exclusion criteria included unstable psychotic symptoms or serious current psychiatric symptoms, such as suicidal or homicidal ideation, or medical problems that would contraindicate the use of naltrexone and disulfiram, including liver function tests over 3 times the normal level.

Treatments

After providing written informed consent, subjects completed an intake assessment, which included a physical examination, laboratory assessments, and an interview with a psychiatrist. Following completion of these baseline assessments, 254 subjects were randomized to 1 of 4 groups for a 12-week trial, but only 251 were included in this analysis because of missing data. Randomization included (1) open randomization to disulfiram 250 mg or no disulfiram and (2) randomization to naltrexone 50 mg or placebo in a double-blind fashion. This resulted in the following groups: (1) naltrexone alone, (2) placebo alone, (3) disulfiram and naltrexone, or (4) disulfiram and placebo. The use of a placebo control condition for disulfiram may lead to the temptation for individuals to sample alcohol in order to “test” the blind, leaving questions about safety and the ability to maintain a true medication blind. For that reason, individuals were randomized to either disulfiram or no disulfiram, and disulfiram was dispensed in an open-label fashion. The dispensing of naltrexone was placebo controlled and double blind.

Study medications were dispensed in bottles with Microelective Events Monitoring (MEMS) caps in order to monitor compliance at every visit. Subject participated in “treatment as usual” at the site from which they were recruited. All 3 sites relied heavily on intensive rehabilitation treatment with supportive housing and recommended aftercare during early abstinence. The methods from this study were described in more detail previously.38

Assessments

Primary outcomes were measures of alcohol use. The substance-abuse calendar, based on the Timeline Follow-Back Interview,43 was administered by trained research personnel at each weekly visit to collect a detailed self-report of daily alcohol and other substance use throughout the 84-day treatment period as well as for the 90-day period prior to randomization. Craving was assessed weekly using the Obsessive Compulsive Drinking and Abstinence Scale (OCDS).44

Psychiatric symptoms were assessed using the Psychotic Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS)45 and were administered by the research staff at the baseline and biweekly during treatment.

Side effects and common adverse symptoms were evaluated by the research staff weekly using Hopkins Symptom Checklist.46 The symptoms that are known to be associated with naltrexone and disulfiram treatment were specifically evaluated and have been described in detail previously.38

Data Analysis

The results presented in this article represent a post hoc analysis of a previously analyzed data set.38 Demographic, substance-use variables, and psychiatric medications at baseline and adverse events during treatment were compared by either diagnosis condition (psychotic spectrum disorder vs nonpsychotic spectrum disorder) or condition and medication group using χ2 analyses for dichotomous and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. The primary outcome variables were consecutive days of abstinence, total number of days of abstinence, and the number of heavy drinking days (defined as 5 or more standard drinks) per week calculated from the substance-abuse calendar data. Outcome variables were analyzed using random effects regression models with repeated measures47 and a priori contrasts for the intent to treat sample. The primary contrasts were (1) the combination of disulfiram/naltrexone vs either disulfiram or naltrexone alone, (2) disulfiram alone vs naltrexone alone, and (3) any medicine vs placebo. ANOVA models were used for continuous outcomes not evaluated longitudinally using the same contrasts (eg, ADS scores, consecutive days of abstinence).

Results

Study Participants

The subjects for this study were all 251 veterans who were enrolled in the Mental Illness Research Education Clinical Center Naltrexone Disulfiram Treatment Trial.38 The subject characteristics and results have been previously described in more detail elsewhere.38 Within the entire sample, 66 (26%) subjects met current DSM-IV criteria for a psychotic spectrum disorder, while 185 (73%) did not. Within the group of patients with psychotic spectrum disorders, 7 (11%) individuals met criteria for schizoaffective disorder, 11 meet criteria for schizophrenia, and 48 (73%) had bipolar disorder. Within the group that did not have a psychotic spectrum disorder, 150 (81%) had major depressive disorder, 86 (46%) had PTSD, 26 (14%) had panic disorder, and 20 (11%) had GAD. These numbers exceed 185 because many subjects had more than one diagnosis. There were no differences in age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, or education in a comparison of the subsample of patients who had psychotic spectrum disorders and those who did not (see table 1). A total of 220 (87.6%) subjects were prescribed psychiatric medications during the study. As expected, there were significant differences between the psychotic spectrum and nonpsychotic spectrum subjects in prescribed atypical antipsychotics (15% vs 2%, respectively, χ2 = 15.58, P = .00), typical antipsychotics use (29.6% vs 17.3%, respectively, χ2 = 6.55, P = .01), and lithium (15% vs 2%, respectively, χ2 = 13.41, P = .001). There were no significant differences between the psychotic spectrum and nonpsychotic spectrum subjects in prescribed anticonvulsants. There were significant different in baseline PANSS-positive scores between those with psychotic spectrum disorders and those without psychotic spectrum disorders (10.39 ± 2.99 vs 9.46 ± 2.55, respectively, F1,62 = 5.55, P = .02) but no significant differences in PANSS-negative scores or PANSS-general scores.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Sample |

|||||

| Variable | Nonpsychotic Spectrum Disorder (n = 185) | Psychotic Spectrum Disorder (n = 66) | Total (n = 251) | Statistics | |

| Age (mean, SD) | 47.49 (8.31) | 45.58 (7.24) | 46.98 (8.07) | F = 2.74 | P = 0.10 |

| Gender (n, %) | χ2 | P | |||

| Male | 181 (98%) | 63 (95%) | 244 (97%) | 1.02 | 0.31 |

| Female | 4 (2%) | 3 (5%) | 7 (3%) | ||

| Total | 185 | 66 | 251 | ||

| Race (n, %) | χ2 | P | |||

| Native American | 7 (4) | 1 (1.5) | 8 (3) | 2.41 | 0.66 |

| Black | 33 (18) | 10 (15) | 43 (17) | ||

| Hispanic | 10 (5) | 2 (3) | 12 (5) | ||

| White | 134 (72) | 52 (79) | 186 (74) | ||

| Others | 1 (1) | 1 (1.5) | 2 (1) | ||

| Total | 185 | 66 | 251 | ||

| Marital status (n, %) | χ2 | P | |||

| Single | 37 (20) | 25 (38) | 62 (25) | 11.0 | 0.05 |

| Married | 23 (13) | 4 (6) | 27 (11) | ||

| Widowed | 6 (3) | 2 (3) | 8 (3) | ||

| Divorced | 89 (48) | 23 (35) | 112 (45) | ||

| Separated | 23 (13) | 8 (12) | 31 (12) | ||

| Living with partner | 6 (3) | 4 (6) | 10 (4) | ||

| Total | 184 | 66 | 250 | ||

| Education | F | P | |||

| Years (mean, SD) | 12.9 (1.8) | 12.8 (1.9) | 12.9 (1.9) | 0.39 | 0.53 |

| Medicationsa (%) | χ2 | P | |||

| Atypical antipsychotics | 2 | 15 | 5.5 | 15.58 | 0.00 |

| Typical antipsychotics | 14.5 | 28.7 | 18.3 | 6.55 | 0.01 |

| Lithium | 2.7 | 15 | 6 | 13.42 | 0.00 |

| Anticonvulsants | 26 | 35 | 29b | 2.61 | 0.27 |

| Measures of alcohol drinking (mean, SD) | F | P | |||

| Years of ethanol use (lifetime) | 25.84 (9.82) | 26.65 (8.86) | 26.05 (9.57) | 0.35 | 0.55 |

| Number of drinks (30 days) | 326.95 (350.11) | 264.88 (336.57) | 311.36 (347.07) | 1.37 | 0.24 |

| Heavy drinking days (30 days) | 14.08 (12.02) | 11.68 (11.41) | 13.45 (11.89) | 1.99 | 0.16 |

| Drinking days (30 days) | 15.33 (12.03) | 13.21 (11.72) | 14.77 (11.96) | 1.53 | 0.22 |

| ADS total score (mean, SD) | 22.20 (8.72) | 21.88 (8.79) | 22.12 (8.72) | F = 0.7 | P = 0.80 |

| PANSS baseline score (mean, SD) | F | P | |||

| Positive scale | 9.46 (2.55) | 10.39 (2.99) | 9.71 (2.70) | 5.55 | 0.02 |

| Negative scale | 9.92 (3.51) | 10.73 (3.55) | 10.14 (3.53) | 2.52 | 0.15 |

| General scale | 24.86 (5.27) | 24.19 (5.51) | 24.68 (5.33) | 0.75 | 0.38 |

Note: ADS = Alcohol Dependence Scale; PANSS = Psychotic Positive and Negative Symptom Scale.

Some subjects were prescribed more than one medication.

Data for 2 subjects not available.

As a measure of baseline substance use, drinking data were reported for the first 30 days of the baseline data that were collected for 90 days before they entered treatment. As shown in table 1, there were no significant differences between those with psychotic spectrum disorders and those without in number of years of alcohol use, number of drinks in the first 30 days of the baseline period, drinking days, heavy drinking days, or ADS scores.

Within the group of subjects with psychotic spectrum disorders, baseline PANSS scores were compared between diagnostic groups to evaluate group differences in baseline psychopathology. There were no significant differences in PANSS-general scores at baseline between those with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder (n = 18) and those with bipolar disorder (n = 46, 2 had missing baseline PANSS scores) (25.7 ± 6.2 vs 23.6 ± 5.5, respectively) or in PANSS-positive scores (11.3 ± 3.6 vs 10.4 ± 2.7, respectively). There were significant differences between those with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder in PANSS-negative symptoms (12.8 ± 4.4) compared with those with bipolar disorder (9.9 ± 2.8) (F1,62 = 10.6, P = .002).

Treatment Retention and Medication Compliance

Treatment retention was defined as the number of days between the first and last medication dose taken based on the MEMS data. There were no significant differences in overall retention in the group of subjects with psychotic spectrum disorders and those without. Further, there were no significant interactions between the diagnosis of a psychotic spectrum disorder and treatment group in treatment retention. Similarly, there was no significant difference in completion status between subjects with a psychotic spectrum disorder and those without. The completion rate in both groups was almost 90% (89% for subjects with psychotic spectrum disorder and 87% for subjects without). Medication compliance was high overall in this study (82.7%), and there were no significant differences in the group of subjects with psychotic spectrum disorders and those without. Further, there were no significant interactions between the diagnosis of a psychotic spectrum disorder and treatment group in medication compliance.

Alcohol-Use and Craving Outcomes

In the entire sample, subjects significantly decreased their alcohol use from baseline to posttreatment in all outcome measures. There was a very high overall rate of abstinence (177 or 69.7% of the total sample reported 100% abstinence) during the active phase of the study. Overall, subjects assigned to either naltrexone or disulfiram reported significantly fewer drinking days per week (F1,246 = 5.71, P = .02) and more consecutive days of abstinence (F1,246 = 4.49, P = .04) than those assigned to placebo. There were no significant differences by treatment condition in the percentage of heavy drinking days or in the number of abstinent days for the entire study period. There were no advantages in any of the measures of alcohol consumption for subjects who received both medications compared with those treated with either active medication alone.

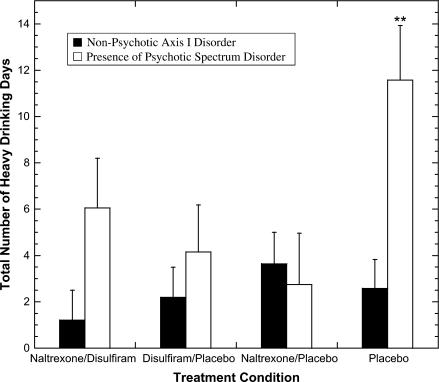

Overall, subjects with psychotic spectrum disorders had fewer days of consecutive abstinence, fewer total days of abstinence, and more heavy drinking days than those without psychotic spectrum disorders. In all, 38% of the subjects with psychotic spectrum disorders relapsed, compared with 23% of those without (χ2 = 5.17, df = 1, P < .05). Further, there were significant interactions between the diagnosis of a psychotic spectrum disorder and medication condition on several alcohol-use outcomes. In each case, subjects with psychotic spectrum disorders that were treated with active medication (disulfiram or naltrexone) had significantly better outcomes when compared with subjects on placebo (see table 2). Specifically, those with psychotic spectrum disorders who were treated with active medication had significantly more days of abstinence (t = 2.8, P = .01) and fewer total heavy drinking days (t = 2.31, P = .02) when compared with placebo (see figure 1). There were no significant differences in outcome in those treated with naltrexone compared with those treated with disulfiram and no advantage of the combination compared with either alone.

Table 2.

Primary Outcome Variables by Diagnosis of Psychotic Spectrum Disorder

| Interaction (treatment contrast by psychotic spectrum disorder) |

|||||||||||||

| Disulfiram/Naltrexone (mean, SD) | Disulfiram/Placebo (mean SD) | Naltrexone (mean SD) | Placebo (mean SD) | By Diagnosis (df = 1,243) (t, P) | DNd vs DPd (t, P) | DPd vs Nd (t, P) | Any medication vs Pd (t, P) | ||||||

| Alcohol-use outcomesa | |||||||||||||

| Maximum consecutive days of abstinence | 2.05, .04 | 0.79, .43 | 1.47, .14 | 1.50, .14 | |||||||||

| Psychotic spectrum (n = 66) | 69.2 (20.8) | 61.1 (28.8) | 67.6 (26.1) | 47.2 (34.3) | |||||||||

| Nonpsychotic spectrum (n = 185) | 68.8 (25.5) | 75.3 (20.2) | 66.7 (25.8) | 64.8 (28.3) | |||||||||

| Total days abstinentb | 3.23, .00 | 1.07, .29 | 0.90, .37 | 2.80, .01 | |||||||||

| Psychotic spectrum (n = 59) | 77.4 (12.8) | 78.8 (11.6) | 80.4 (7.0) | 68.4 (18.8) | |||||||||

| Nonpsychotic spectrum (n = 164) | 82.3 (4.0) | 81.6 (8.3) | 79.6 (11.4) | 80.8 (8.6) | |||||||||

| Total number of heavy drinking days | 2.93, .00 | 1.41, .16 | 0.81, .42 | 2.31, .02 | |||||||||

| Psychotic spectrum (n = 66) | 6.06 (11.5) | 4.16 (10.8) | 2.75 (5.7) | 11.57 (15.6) | |||||||||

| Nonpsychotic spectrum (n = 185) | 1.21 (2.9) | 2.20 (8.1) | 3.64 (10.8) | 2.58 (7.6) | |||||||||

| OCDS total score change over timec | n | n | n | n | z, P | z, P | z, P | z, P | Time z, P | ||||

| Pre | |||||||||||||

| Psychotic spectrum (n = 52) | 9.00 (7.4) | 13 | 14.2 (7.8) | 13 | 10.9 (4.9) | 14 | 14.3 (8.9) | 12 | 1.06, .29 | 1.60, .11 | 0.77, .44 | 0.21, .83 | −10.53, .00 |

| Nonpsychotic spectrum (n = 160) | 15.2 (8.9) | 39 | 10.5 (8.6) | 43 | 13.2 (7.8) | 37 | 15.7 (7.9) | 41 | |||||

| Post | |||||||||||||

| Psychotic spectrum (n = 50) | 6.0 (10.4) | 13 | 5.3 (4.4) | 12 | 8.4 (9.3) | 14 | 5.6 (9.1) | 11 | |||||

| Nonpsychotic spectrum (n = 158) | 5.9 (6.9) | 38 | 3.8 (5.9) | 43 | 5.2 (6.5) | 37 | 4.7 (7.5) | 40 | |||||

Note: OCDS = Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale.

The alcohol outcome measures were calculated from the TLFB for the entire treatment period of 12 weeks or 84 days.

df = 1,215.

Statistics from the OCDS analyses represent the treatment contrast by psychotic spectrum disorders by time effects.

DN is disulfiram and naltrexone group, DP is disulfiram and placebo group, N is naltrexone group, and P is placebo group.

Fig. 1.

Total Number of Heavy Drinking Days (defined as 5 or more standard drinks per day) During Active Treatment for Subjects With Psychotic Spectrum Disorders vs Those With Other Axis I Disorders. **Significant difference for any drug vs placebo: P = .014.

Based on the OCDS,48 there were no significant differences between psychotic spectrum and the no psychotic spectrum subjects on the total OCDS scores. Subjects overall reported significantly lower measures of craving over time. There was no effect of medication condition on overall OCDS scores (see table 2).

Effect of Study Treatments on PANSS Symptoms

There were neither significant changes in positive, negative, or general PANSS scores by time nor any significant interactions of treatment and time in the subsample of subjects with psychotic spectrum disorders (n = 66).

Safety and Side Effects

Overall, there were significant differences between the side effects reported by the psychotic spectrum group and nonpsychotic spectrum group, where subjects with psychotic spectrum disorders were more likely to report abdominal pain (59% vs 43%, respectively, χ2 = 6.9, P = .009), sweating (70% vs 57%, respectively, χ2 = 5.0, P = .02), and tremors (61% vs 43%, respectively, χ2 = 8.1, P = .004). There were no significant differences by medication group in abdominal pain, sweating, or tremors within the group of subjects with psychotic spectrum disorders.

There were 6 serious adverse events in subjects with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder out of a total of 14 for the entire sample.38 The adverse events in the subjects who had schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder included 1 cardiac event (disulfiram/placebo treated). The adverse events (5) in the subjects who had bipolar disorder included 1 medical hospitalization (disulfiram/placebo treated), 3 psychiatric hospitalizations (disulfiram/placebo treated, disulfiram/naltrexone treated, and placebo treated), and 1 death (placebo treated). The death was thought to be cardiac but determined not to be study related because the subject was on placebo. In the entire sample, there was one alcohol-disulfiram reaction, but it occurred in an individual with a nonpsychotic spectrum disorder.

Discussion

The results from this 12-week randomized clinical trial of disulfiram and naltrexone suggest that individuals with Axis I psychotic spectrum disorders (1) showed no difference in treatment retention or medication compliance compared with subjects with nonpsychotic spectrum disorders, (2) had more heavy drinking days and fewer days of abstinence overall than individuals with nonpsychotic spectrum disorders, (3) did better if treated with either naltrexone or disulfiram compared with placebo, (4) had no change in psychotic symptoms, and (5) had no more side effects or adverse reactions than subjects with nonpsychotic spectrum disorders. For both psychotic spectrum disorder and nonpsychotic spectrum disorder patients, there was no clear advantage of the combination of disulfiram and naltrexone over either alone. This study supports the use of these medications for the treatment of alcohol dependence in individuals with comorbid psychotic spectrum disorders.

Results from this study suggest that individuals with psychotic spectrum disorders are particularly suited for treatment with medications for alcohol dependence. This may be because the medication is more effective in this group of patients or may be in part because patients with a psychotic spectrum disorder may not be able to benefit as fully from the forms of treatments that have been developed for noncomorbid alcohol-dependent individuals, so medication effects may be more readily apparent. The high placebo rate in the subjects with nonpsychotic spectrum disorders suggests they may have benefited more from the psychosocial treatment in direct contrast to those with psychotic spectrum disorders. Another factor that may have influenced outcome is that a larger percentage of patients with psychotic spectrum disorders were on neuroleptics. There are a number of studies that have suggested that the dopamine system plays an important role in alcohol dependence49 and neuroleptics may influence alcohol-use outcomes. The small sample size in this study precludes the evaluation of the role other medications may have had on substance-use outcomes.

Because the results from this study do not differentiate between naltrexone and disulfiram in clinical efficacy, consideration of the clinical characteristics of a patient and the advantages and disadvantages of these medications may be the deciding factors in the choice of medication. Naltrexone's advantages include its potential to reduce craving, to alter the rewarding experience of intoxication, and to reduce the priming effect of taking an initial drink and thereby reducing the likelihood of relapse to subsequent heavy drinking. In contrast to disulfiram, naltrexone use does not lead to a powerful aversive reaction if patients consume alcohol; therefore, patients may be more willing to initiate naltrexone treatment and to continue to take the medication because they know that drinking is not prohibited. Despite naltrexone's theoretical advantages over disulfiram in terms of fostering patient acceptance, compliance has been shown to be a major factor in treatment efficacy of naltrexone as well.50,51 It should be noted that in our study, there was no advantage of naltrexone over disulfiram in measures of compliance. Of interest is the current development of a depot preparation of naltrexone52 that may help address issues of compliance. This depot formulation has not yet been formally tested in this patient population.

Disulfiram's advantage is that it definitively fosters complete abstinence. It is especially useful in the abstinence initiation phase because it eliminates impulsive alcohol use, although it does not help with use planned over a several day period. The total prohibition of drinking may also reduce preoccupation with alcohol because craving has been shown to be related to perceived availability of abused substances.53 Results from the main trial were surprising because we found an unexpected advantage of disulfiram over naltrexone in levels of craving,38 which may be consistent with this hypothesis. Disulfiram's disadvantages include the potential for worsening of psychiatric symptoms, reluctance on the part of clinicians to prescribe it for “vulnerable” populations, and limited patient acceptance. Based on a careful evaluation of symptoms on a biweekly basis, we found no evidence that disulfiram at a dose of 250 mg causes a worsening of psychotic symptoms. Psychotic spectrum disorder patients were also compliant with medications and were no more likely than nonpsychotic spectrum patients to drink with disulfiram. It must be noted that this group of subjects were considered clinically stable, were adequately treated with psychotropic medication, and were found to have only mild symptoms of psychosis. Further, only subjects willing to be randomized to disulfiram who were perhaps highly motivated were included in this trial. Therefore, results from this trial may not be generalizable to all dually diagnosed individuals, particularly those who are more unstable or those not motivated for treatment and who represent a serious clinical challenge.54

While the study was designed to test these medications in a “real-world setting,” there are some other limitations that may influence the generalizability of this study. The study was conducted in the VA setting, in predominately male subjects. Subjects were mostly recruited from settings that relied on intensive rehabilitation with supportive housing, and this may have accounted for the high rates of abstinence. The lack of systematic data on psychosocial treatment did not allow for the evaluation of the effect of psychosocial intervention on alcohol-use outcomes. Further, the small sample size and heterogeneity of diagnostic disorders preclude the evaluation of the effect of these medications on specific diagnostic groups. Nevertheless, overall our data have clinical utility and suggest that naltrexone and disulfiram should be seriously considered for the clinical management of patients with psychotic spectrum disorders and alcohol dependence.

Future Directions

Disulfiram and naltrexone represent only 2 of the 3 medications approved by the FDA for the treatment of alcohol dependence. Acamprosate (Campral®) was approved by the FDA in 2004 largely on the basis of 3 pivotal large European clinical trials, with supporting evidence from several additional European studies.55 Acamprosate is a homotaurine derivative, and some studies suggest that it may attenuate glutamate effects at n-methyl-d-aspartate glutamate receptors or facilitate the function of gamma-amino-butyric acid-A receptors.56,57

Acamprosate has been studied in over 16 trials with over 4500 outpatients.58 Most of the studies showed a significant advantage of acamprosate over placebo in abstinence and cumulative abstinence.58 A meta-analysis of all studies published to date with a sample size in the range of 3077–3204 found that outcomes with acamprosate were significant but modest,24 with the most robust effect of acamprosate on cumulative abstinent days. Because acamprosate is not metabolized in the liver (unique among the antidipsotropic medications), it may be particularly useful in patients with alcoholism complicated by liver disease. It has been used safely with other medications commonly prescribed in alcohol-dependent individuals (antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, etc.).56 It is recommended for individuals who have achieved abstinence; therefore, acamprosate may be an excellent choice for pharmacotherapy when initiated in a setting where patients have a high likelihood of reaching initial abstinence. Some authors have suggested acamprosate is indicated for a broad range of patients with alcohol dependence, although it has not been rigorously tested in severe alcoholism or in patients with serious Axis I disorders. Unfortunately, in the recent multisite COMBINE trial, acamprosate had no effect on alcohol-use outcomes.27

Another promising line of inquiry is the use of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of substance-use disorders in comorbid populations. Some recent evidence, most of it involving clozapine, supports the hypothesis that the newer generation of antipsychotics may result in a reduction in comorbid substance misuse in patients with schizophrenia.59 Most of this evidence is based on case reports60–63 and retrospective chart reviews.64–66 Clearly, definitive clinical trials are still needed to determine the efficacy of atypicals in treating substance-use disorders in individuals with schizophrenia.

Reports have suggested that anticonvulsants may reduce alcohol intake and craving.67,68 The most promising, topiramate, has been shown to decrease drinking in subjects manifesting alcohol dependence.69 Clinically, there are case reports of alcohol-dependent patients manifesting comorbid bipolar disorder in whom oxcarbazepine was associated with improvement in psychiatric symptoms and reduced intake of alcohol and cannabis.70 More recently, in a controlled study with valproic acid in alcohol dependence and comorbid bipolar disorder, valproate therapy was found to decrease heavy drinking in comparison with placebo.9

Overall, patients with alcohol dependence and comorbid psychotic spectrum disorders such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder, seem to be particularly well suited to pharmacotherapies to treat their alcohol-use disorders. Currently, only naltrexone and disulfiram have been formally evaluated, and studies are needed to evaluate acamprosate, the latest FDA-approved medication for alcoholism in the seriously mentally ill. Exciting new directions include the use of atypical neuroleptics or anticonvulsants, which enjoy the advantage of treating both the underlying psychiatric disorder and the alcohol-use disorder. Of course, these medications have all been effective in the context of psychosocial interventions, and this underscores the need for comprehensive treatment for this population.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs–Yale Alcohol Research Center [Principal Investigator (PI): J. Krystal], the New England Mental Illness Research Education Clinical Center (PI: B. Rounsaville), a VA Merit Grant, and the Stanley Foundation.

References

- 1.Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study. JAMA. 1990;264:2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dixon L. Dual diagnosis of substance abuse in schizophrenia: prevalence and impact on outcomes. Schizophr Res. 1999;35(suppl):S93–S100. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerding LB, Labbate LA, Measom MO, Santos AB, Arana GW. Alcohol dependence and hospitalization in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1999;38:71–75. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owen RR, Fischer EP, Booth BM, Cuffel BJ. Medication noncompliance and substance abuse among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47:853–858. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.8.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miles H, Johnson S, Amponsah-Afuwape S, Finch E, Leese M, Thornicroft G. Characteristics of subgroups of individuals with psychotic illness and a comorbid substance use disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:554–561. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallace C, Mullen PE, Burgess P. Criminal offending in schizophrenia over a 25-year period marked by deinstitutionalization and increasing prevalence of comorbid substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:716–727. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petrakis IL, O'Malley S, Rounsaville B, Poling J, McHugh-Strong C, Krystal JH. Naltrexone augmentation of neuroleptic treatment in alcohol abusing patients with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology. 2004;172:291–297. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1658-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ziedonis D, Richardson T, Lee E, Petrakis IL, Kosten T. Adjunctive desipramine in the treatment of cocaine abusing schizophrenics. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1992;28:309–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salloum IM, Cornelius JR, Daley DC, Kirisci L, Himmelhoch JM, Thase ME. Efficacy of valproate maintenance in patients with bipolar disorder and alcoholism: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:37–45. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noordsy DL, Schwab B, Fox L, Drake RE. The role of self-help programs in the rehabilitation of persons with severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Community Ment Health J. 1996;32:71–81. doi: 10.1007/BF02249369. ; discussion 83–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garbutt J, West S, Carey T, Lohr K, Crews F. Pharmacological treatment of alcohol dependence, a review of the evidence. JAMA. 1999;281:1318–1325. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.14.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuller RK, Branchey L, Brightwell DR, et al. Disulfiram treatment of alcoholism: a Veterans Administration cooperative study. JAMA. 1986;256:1449–1455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bigelow G, Stricker D, Liebson E, Griffiths R. Maintaining disulfiram ingestion among outpatient alcoholic: a security-deposit contingency contracting procedure. Behav Res Ther. 1976;14:378–381. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(76)90028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keane TM, Foy DW, Nunn B, Rychtarik RG. Spouse contracting to increase antabuse compliance in alcoholic veterans. J Clin Psychol. 1984;40:340–344. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198401)40:1<340::aid-jclp2270400162>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Farrell TJ, Bayog RD. Antabuse contracts for married alcoholics and their spouses: a method to maintain antabuse ingestion and decrease conflict about drinking. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1986;3:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(86)90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuller R, Roth H, Long S. Compliance with disulfiram treatment of alcoholism. J Chronic Dis. 1983;36:161–170. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(83)90090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larson EW, Olincy A, Rummans TA, Morse RM. Disulfiram treatment of patients with both alcohol dependence and other psychiatric disorders: a review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1992;16:125–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher CM. ‘Catatonia’ due to disulfiram toxicity. Arch Neurol. 1989;46:797–804. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520430094024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mueser K, Noordsy D, Fox L, Wolfe R. Disulfiram treatment for alcoholism in severe mental illness. Am J Addict. 2003;12:242–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Froehlich J, O'Malley S, Hyytia P, Davidson D, Farren C. Preclinical and clinical studies on naltrexone: what have they taught each other? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:533–539. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000057943.57330.AB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volpicelli J, Alterman A, Hayashida M, O'Brien C. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:876–880. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820110040006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Malley S, Jaffe A, Chang G, Schottenfeld R, Meyer R, Rounsaville B. Naltrexone and coping skills therapy for alcohol dependence. A controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:881–887. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820110045007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anton RF, Moak DH, Waid R, Latham PK, Malcolm RJ, Dias JK. Naltrexone and cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment of outpatient alcoholics: result a placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1758–1764. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.11.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kranzler H, Van Kirk J. Efficacy of naltrexone and acamprosate for alcoholism treatment: a meta-analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1335–1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heinala P, Alho H, Kiianmaa K, Lonnqvist J, Kuoppasalmi K, Sinclair JD. Targeted use of naltrexone without prior detoxification in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a factorial double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21:287–292. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200106000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kranzler HR, Armeli S, Tennen H, et al. Targeted naltrexone for early problem drinkers. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:294–304. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000084030.22282.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anton RF, O'Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial [see comment] JAMA. 2006;295:2003–2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kranzler H, Modesto-Lowe V, Van Kirk J. Naltrexone vs. nefazodone for treatment of alcohol dependence. A placebo-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:493–503. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gastpar MT, Bonnet U, Boning J, et al. Lack of efficacy of naltrexone in the prevention of alcohol relapse: results from a German multicenter study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22:592–598. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200212000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krystal JH, Cramer J, Krol W, Kirk G, Rosenheck R. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. New Engl J Med. 2001;345:1734–1739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fuller R, Gordis E. Naltrexone treatment for alcohol dependence. New Engl J Med. 2001;345:1770–1771. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200112133452411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morris PL, Hopwood M, Whelan G, Gardiner J, Drummond E. Naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial [comment] Addiction. 2001;96:1565–1573. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961115654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maxwell S, Shinderman MS. Use of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol use disorders in patients with concomitant major mental illness. J Addict Dis. 2000;19:61–69. doi: 10.1300/J069v19n03_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salloum I, Cornelius J, Thase M, Daley D, Kirisci L, Spotts C. Naltrexone utility in depressed alcoholics. Psychopharmacology. 1998;34:111–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petrakis IL, Leslie D, Rosenheck R. Use of naltrexone in the treatment of alcoholism nationally in the department of veterans affairs. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1780–1784. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000095861.43232.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Batki S, Dimmock J, Leontieva L, et al. Recruitment and characteristics of alcohol dependent patients with schizophrenia. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:78A. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Batki S, Dimmock J, Cornell M, Wade M, Carey K, Maisto S. Directly observed naltrexone treatment of alcohol dependence in schizophrenia: preliminary analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:83A. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petrakis IL, Poling J, Levinson C, Nich C, Rounsaville B. Naltrexone and disulfiram in patients with alcohol dependence and comorbid psychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1128–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sbrana A, Dell'Osso L, Benvenuti A, et al. The psychotic spectrum: validity and reliability of the Structured Clinical Interview for the Psychotic Spectrum. Schizophr Res. 2005;75:375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bellack A, Bennett M, Gearon J, Brown C, Yang Y. A randomized clinical trial of a new behavioral treatment for drug abuse in people with severe and persistent mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:426–432. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.First MD, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (Patient Edition) (SCID-P). Biometric Research. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skinner HA, Horn JL. Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS): User's Guide. Toronto, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline Follow-Back: a technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R, Allen J, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption. Totowa, NJ: The Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anton RF, Moak DH, Latham PK. The Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale: a new method of assessing outcome in alcoholism treatment studies [published erratum appears in Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:576] Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:225–231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830030047008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kay S, Fiszbein A, Opler L. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci. 1974;19:1–15. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830190102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hedeker D, Gibbons R, Davis J. Random regression models for multicenter clinical trials data. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1991;27:73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anton RF, Moak DH, Latham P. The Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale: a self-rated instrument for the quantification of thoughts about alcohol and drinking behavior. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:92–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koob GF. Neurobiology of addiction Toward the development of new therapies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;909:170–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chick J. UK multicenter study of naltrexone as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of alcoholism: efficacy results. Abstr X World Congr Psychiatry. 1996;1:230. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Volpicelli JR, Rhines KC, Rhines JS, Volpicelli LA, Alterman AI, O'Brien CP. Naltrexone and alcohol dependence. Role of subject compliance [see comment] Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:737–742. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830200071010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kranzler HR, Wesson DR, Billot L, Drug G. Naltrexone depot for treatment of alcohol dependence: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1051–1059. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000130804.08397.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sinha R, O'Malley SS. Craving for alcohol: findings from the clinic and the laboratory. Alcohol Alcohol. 1999;34:223–230. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Herbeck DM, Fitek DJ, Svikis DS, Montoya ID, Marcus SC, West JC. Treatment compliance in patients with comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders. Am J Addict. 2005;14:195–207. doi: 10.1080/10550490590949488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Approval Package for: Application Number 21–431; 2004. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/nda/2004/21-431_Campral.htm. Accessed August 1, 2006

- 56.Mason BJ, Goodman AM, Dixon RM, et al. A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic drug interaction study of acamprosate and naltrexone. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:596–606. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00368-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Littleton J. Acamprosate in alcohol dependence: how does it work? Addiction. 1995;90:1179–1188. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.90911793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mason B. Treatment of alcohol-dependent outpatients with acamprosate: a clinical review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(20):42–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Buckley PF. Substance abuse in schizophrenia: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 3:):26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Albanese MJ, Khantzian EJ, Murphy SL, Green AI. Decreased substance use in chronically psychotic patients treated with clozapine [letter] Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:780–781. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.5.780b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yovell Y, Opler LA. Clozapine reverses cocaine craving in a treatment-resistant mentally ill chemical abuser: a case report and a hypothesis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1994;182:591–592. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199410000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marcus P, Snyder R. Reduction of comorbid substance abuse with clozapine. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:959. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.6.959a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Drake RE, Xie H, McHugo GJ, Green AI. The effects of clozapine on alcohol and drug use disorders among patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:441–449. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Volavka J. The effects of clozapine on aggression and substance abuse in schizophrenic patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 12:):43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Green AI, Burgess ES, Dawson R, Zimmet SV, Strous RD. Alcohol and cannabis use in schizophrenia: effects of clozapine vs. risperidone. Schizophr Res. 2003;60:81–85. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00231-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zimmet SV, Strous RD, Burgess ES, Kohnstamm S, Green AI. Effects of clozapine on substance use in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: a retrospective survey. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20:94–98. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200002000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mueller TI, Stout RL, Rudden S, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of carbamazepine for the treatment of alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:86–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kranzler HR, Burleson JA, Korner P, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine as an adjunct to relapse prevention in alcoholics. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:391–397. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Johnson B, Ait-Daoud N, Bowden C, et al. Oral topiramate for treatment of alcohol dependence: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:1677–1685. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nasr S. Oxcarbazepine for mood disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1793. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]