Abstract

Recognition of the need to treat cognitive deficits in schizophrenia is compelling and well established, with empirical findings and conceptual arguments related to cognitive enhancement appearing regularly in the literature. Cognitive enhancement itself, however, remains at an early stage. Biological approaches have centered on the development of antipsychotic medications that also improve cognition, but the results have so far remained modest. As a way to facilitate the development of cognitive enhancers in schizophrenia, this article focuses on adjunctive pharmacological approaches to antipsychotic medications and highlights the need for systematic explorations of relevant brain mechanisms. While numerous conceptual criteria might be employed to guide the search, we will focus on 4 points that are especially likely to be useful and which have not yet been considered together. First, the discussion will focus on deficits in a particular cognitive domain, verbal declarative memory. Second, we will review the current status of preclinical and clinical efforts to improve declarative memory using antipsychotic medications, which is the main, existing mode of treatment. Third, we will examine an example of an adjunctive intervention—glucose administration—that improves memory in animals and humans, modulates function in brain regions related to verbal declarative memory, and is highly amenable to translational research. Finally, a heuristic model will be outlined to explore how the intervention maps on to the underlying neurobiology of schizophrenia. More generally, the discussion underlines the promise of cognitive improvement in schizophrenia and the need to approach the issue in a programmatic manner.

Keywords: cognitive enhancement, antipsychotic medication, medial temporal lobe

Introduction

The reduction of positive symptoms (ie, hallucinations and delusions) has traditionally been the main goal of pharmacological treatments for schizophrenia. Even as first- and second-generation antipsychotic medications allow many patients to approach that goal, however, residual disabilities involving neuropsychological and other clinical problems (eg, negative symptoms) continue to prevent patients from assuming functional, independent lives.1–5 While some antipsychotic medications may improve aspects of cognition (eg, Harvey and Keefe,6 Sharma and Mockler,7 Green and Braff8), the effects are modest3 and leave substantial deficits.2,9,10 These deficits, particularly in verbal declarative memory, sustained attention, and executive dysfunction, predict the disabilities in social problem solving, performance of daily/occupational activities, and acquisition of psychosocial skills that contribute to incomplete recovery in most patients.1–5,8

This problem highlights a growing consensus about a need for novel treatment approaches to target cognitive deficits independent of clinical symptoms,3,11–13 and raises the question of how to proceed. Thus far, the search for antipsychotic medications that also improve cognition continues to dominate the field, with the modest outcomes noted above. Another approach involves the development of focused treatment strategies that are adjunctive to, but independent of, antipsychotic medications, as is reflected in the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)–sponsored Treatment Units for Research on Neurocognition in Schizophrenia initiative. This article emphasizes the adjunctive approach and proposes a systematic exploration of brain mechanisms that might facilitate the development of cognitive enhancers in schizophrenia. Although numerous conceptual criteria might be utilized to guide the search for cognitive enhancers, the current discussion will focus on 4 that are likely to be useful. The first issue is to select one or more cognitive domains that are impaired in schizophrenia. In this discussion, dysfunction in long-term verbal declarative memory will be emphasized. The second issue involves the current status of preclinical and clinical efforts to improve declarative memory using antipsychotic medications, which is the main existing mode of treatment. The third point will be to review evidence for an example of an adjunctive treatment that improves memory in animals and humans. Glucose administration will be highlighted for this purpose because it improves declarative memory in a variety of situations that include schizophrenia, modulates brain regions and mechanisms involved in verbal declarative memory, and is highly amenable to translational research. The fourth point will be to review the extent to which the proposed approach—glucose administration—maps on to the underlying neurobiology of schizophrenia. Toward this end, a heuristic model of glucose administration and cognitive enhancement in schizophrenia will be advanced.

Verbal Declarative Memory and Schizophrenia

Overview

Verbal declarative memory is one of the several cognitive domains that have been studied extensively in schizophrenia. Performance in this domain involves the conscious recall and recognition of facts and episodes and also involves memory for relationships between different elements or dimensions of information.14 Among several brain regions that contribute to verbal declarative memory, the hippocampal region is among the most critical. From a functional perspective, deficits in verbal declarative memory are highly significant and contribute to difficulties in performing activities of daily living in multiple disorders and conditions, including, eg, Alzheimer disease. Deficits in verbal declarative memory in schizophrenia also contribute significantly to the difficulties in independent living and poor clinical outcomes described above,1–5 which underscores their importance as potential treatment targets.

Nature and Extent of Deficits

Cognitive problems are central to schizophrenia and affect the course and outcome of the disorder adversely.15–24 They often occur well before psychosis,25–30 near the first psychotic episode,31,32 and after remission from psychotic symptoms.33–35 Neuropsychological profiles in patients usually include widespread impairments.18,22,36–38

Deficits in verbal declarative memory are well established.39 More than 110 studies reviewed by our research group recently35 showed they are among the most robustly abnormal deficits in schizophrenia, with effect sizes that often exceed 1.0 SD.18,23,35,38,39 The nature of the dysfunction is heterogeneous. Some studies, eg, reported deficits in acquisition/encoding, memory storage (ie, abnormal forgetting), and retrieval,40,41 while others reported significantly abnormal rates of forgetting,19 at least in a portion of the sample.42 Most subjects with schizophrenia show rates of forgetting that are only subtly impaired relative to control subjects and are more like controls than they are like patients with Alzheimer disease.43 They do show prominent deficits in retrieval of information using free recall paradigms and/or difficulties encoding new information but better performance on cued or recognition conditions.35,42,44–46 Although some medications administered to patients with schizophrenia may themselves contribute to performance deficits in tests of verbal memory,47 the presence of memory deficits before or near the first psychotic episode reflects their intrinsic nature.48 Nonpsychotic biological relatives of patients with schizophrenia (who are not taking antipsychotic medication) also perform worse on encoding (but not rate of forgetting) than controls on tests of verbal declarative memory (Cirillo and Seidman35; Faraone et al49; Faraone et al50; Faraone et al51; Kremen and Hoff52; Stone WS, Tsuang MT, Faraone SV et al, unpublished data), which further supports the view that impairments in learning and memory reflect intrinsic features of the disorder rather than epiphenomena related to effects of medication, psychosis, or other cognitive dysfunctions.46

Neurobiological Correlates of Deficits in Declarative Learning and Memory: the Hippocampal Region

The hippocampal and parahippocampal areas are particularly important to the instantiation of verbal declarative memory14,53,54 and to related processes such as sensory information processing, context analysis, and sensory gating (eg, Eichenbaum,53 Freedman et al55). Morphometric and neurohistological studies strongly implicate abnormalities in temporal limbic and prefrontal structures in schizophrenia,56–58 including reduced volume in patients and in nonpsychotic, first-degree relatives of patients.21,59–63 Bilateral abnormalities are most common64 but are relatively greater on the left side.65 These findings are consistent with the hypothesized importance of temporal lobe structures in schizophrenia not only in relation to cognitive dysfunction but also to psychosis and other clinical dimensions that characterize the disorder.58,60,65–69 In contrast, bipolar disorder is not generally associated with reduced hippocampal volumes,70–72 though with exceptions.73

Impaired Hippocampal Recruitment and Function

Impaired hippocampal “recruitment” in schizophrenia during conscious recollection is particularly consistent with reduced hippocampal volume.59,60,74 Seidman et al21,62 reported significant and positive correlations between verbal memory performance and hippocampal volume (ie, smaller volumes were associated with poorer memory performance). Unlike most pathological conditions that involve the hippocampus and memory (eg, Alzheimer disease, stress-related conditions), there is less evidence of hippocampal cell loss (with exceptions, such as Benes et al64) but more evidence of decreased dendritic arborization, fewer neuronal connections, and less gene expression for molecules likely to be involved in neuronal plasticity (eg, non-N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptors, synaptophysin, SNAP-25, synapsin, complexin I and II, and GAP-43).59,60 To an extent, hippocampal abnormalities in schizophrenia are not specific. Although the hippocampus in bipolar disorder is not typically smaller, eg, many similar neurochemical anomalies characterize both conditions,75 particularly in regions that are involved in the type of synaptic plasticity that is important for learning and memory (CA 3 and CA 4).53 One interpretation of these findings is that smaller hippocampi in schizophrenia reflect fewer synaptic connections and less “pressure” than normal to respond to experience with adaptive synaptic remodeling and other forms of neuronal plasticity.60 An implication of this interpretation is that hippocampal function in schizophrenia is thus inefficient. This view is at least consistent with the empirical findings that information is harder to learn and to retrieve, although memory storage itself is not usually the main problem. It is unclear whether genetic and neurophysiological abnormalities alone are sufficient to account for memory impairments in schizophrenia. As will be suggested below, a combination of factors may be necessary to produce observable deficits.

Prefrontal Cortex and Medial Temporal Lobe Connectivity

A detailed discussion of the role of the prefrontal lobes in verbal declarative memory is beyond the scope of the current article. It should be noted, however, that multiple prefrontal brain regions mediate verbal declarative memory in addition to the hippocampal system76–78 and are also involved in working memory. These regions, and possibly the connections between frontal and temporal regions, are often abnormal in schizophrenia58,79–83 and are associated with verbal declarative memory.84

Moreover, frontal lobe pathology is associated with impaired performance on recall and recognition of episodic information.77,85 In this light, one or more underlying prefrontal processes, such as processing speed,86 selection of efficient task strategies,78 and the representation, maintenance, and updating of context information to control behavior81,87 (in concert with other factors such as attention span and motivation), likely contribute to prefrontal dysfunction, which then contributes to deficits in learning, retaining, and retrieving information. Implications of overlapping neurobiological and cognitive substrates for conceptually separate cognitive processes are (1) interventions that modulate function in 1 cognitive domain (eg, verbal declarative memory) may also modulate function in other domains (eg, working memory) and (2) cognitive function in a particular domain may be manipulated either directly or through manipulation of a related cognitive function.

Enhancement of Verbal Declarative Memory in Schizophrenia

Antipsychotic Medication Effects on Cognition

Until the advent of newer “atypical” antipsychotic medications, few improvements in cognition were associated with pharmacological treatments for schizophrenia,88 though this has been debated recently, particularly when appropriately low doses of typical antipsychotic medications were used.89 In 1 recent meta-analysis,90 17 of 23 studies demonstrated relatively superior performance of atypical antipsychotics on long-term memory, but the average difference vs typical antipsychotics (measured in SDs) was small (0.17). Nevertheless, at least some improvements in cognitive function are associated with atypical antipsychotic administration (eg, Sharma and Mockler,7 Green and Braff,8 McGurk,9 Stip,91 Keefe et al,92 Meltzer and McGurk,93 Kern et al,94 Purdon et al,95 Harvey and Keefe,96 Harvey et al,97 Weickert and Kleinman,98 Velligan et al,99 Keefe et al100). Although such gains are encouraging, the improvements are modest (with effect sizes usually <0.5) and substantially smaller than the usual deficit of 1.0–1.5.9,10,23 Notably, the range of improvement tends to be broad, with facilitation reported often in multiple cognitive domains (eg, Purdon et al,95 Harvey et al,97 Velligan et al,99 Keefe et al,100 Weickert101). Consistent with the pharmacological actions of these medications on multiple neurochemical systems, their actions on multiple aspects of cognition reflects their widespread effects on brain function.102

Similarly, pharmacological treatments administered in addition to antipsychotic medications that show promise to improve memory performance involve multiple neurochemical effects. These include, eg, rivastigmine and donepezil, both of which are cholinesterase inhibitors103,104 (but see also [Friedman et al,105 Tual et al,106 Freudenreich,107 Kumari et al108] for negative findings with donepezil), L-tryptophan, an amino acid precursor of serotonin,109 Ondansetron, a serotonergic 3 antagonist,110 mianserin, a serotonergic 2A antagonist,111 and modafinil, whose actions include histamine release.112 Moreover, adjunct pharmacological treatments that may improve other aspects of cognition in schizophrenia, such as attention, appear to do so through diverse neurochemical pathways. These include, eg, guanfacine, an alpha 2A adrenergic agonist,113,114 amphetamine, a monaminergic (ie, dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine) reuptake inhibitor,115–117 modafinil,112 and rivastigmine.103 Some of the drugs listed here (rivastigmine, modafinil) may influence both memory and attention/working memory (among other functions), consistent with the multiple effects demonstrated by antipsychotic medications on cognition.

So far, studies demonstrating positive effects of antipsychotic medications on cognition are largely limited to studies with humans. Studies with animals (rodents, usually) either do not show facilitation or even show impairment.118 Studies that do demonstrate facilitation in animals tend to involve attention,119,120 rather than memory. Conceptually, it is not necessary for an antipsychotic drug to improve cognition in animals in order to predict cognitive improvement in humans or to modulate biological systems that are related to enhanced cognition in people. Nevertheless, the lack of corresponding effects on tests of memory inhibits the development of useful animal models of pharmacological enhancement and slows down the development of translational research.

Multiple Neural Systems and Cognitive Enhancement

The ability of antipsychotic medications and adjunct treatments to modulate multiple aspects or domains of cognition in schizophrenia is consistent with a broader literature showing the multifactorial nature of cognition itself at both behavioral and neurobiological levels. Three related points are particularly relevant to the present discussion. First, interacting neurochemical substrates underlie the performance of most cognitive tasks (eg, White and McDonald,121 Poldrack and Packard,122 Gold,123,124 Myhrer125). Thus, similar to the effects of antipsychotic and adjunct medications, manipulations of different neurochemical systems often influence performance on the same tasks. These results are consistent with our own previous findings in mice showing that scopolamine (a muscarinic cholinergic antagonist, administered systemically)-induced impairments in memory were reversed not only with cholinergic agonists (physostigmine, oxotremorine) but also with adrenergic agonists (amphetamine, epinephrine) and glucose.126 Similarly, systemic glucose and physostigmine administration attenuated nonmnemonic behavioral alterations (ie, locomotor hyperactivity) induced by morphine and amphetamine.127 Second, these neurochemical systems contribute to the formation of neural systems that process and store certain types of information. Although several of these systems are capable of processing information independently of the others, they usually interact. Third, the nature of these interactions between different neural systems varies. Multiple systems of memory, eg, may be cooperative or competitive with each other.122,124,128–131

Several hypotheses may be derived from these findings. First, enhancement of a particular cognitive function does not necessarily have a discrete “solution.” Rather, modulation of neural systems that subserve a particular cognitive function may be achieved through modulation of more than 1 neurochemical system. Second, among neural systems that subserve tasks or components of cognitive tasks, the modulation of some of these systems will be more efficient for performing the task than will the modulation of other systems. In a task involving verbal declarative memory, eg, cognitive enhancement might involve the relative activation of neural systems that process that type of information most efficiently (eg, the hippocampal and parahippocampal regions). It will thus be important to select or develop treatments that target particular neurotransmitters represented in selected brain regions at the time they process that type of information.

Third, factors that influence the contribution of particular neural systems to cognitive tasks modulate the efficiency and manner in which those tasks are performed. These include hormonal influences, eg, that increase the “tone” of some neurochemical systems, while decreasing others. Other factors, such as level of education, may serve as proxy or relatively distal expressions of the benefits to the brain of certain environmental experiences. In this context, the instantiation of learned experiences may provide alternative neural pathways to mediate the performance of cognitive tasks. This view is consistent with recent formulations of “cognitive reserve” (eg, Whalley et al,132 Stern et al,133 Pai and Tsai,134 Le Carret et al,135 Springer et al136), and its consideration, in conjunction with effects of particular treatments, offers a way to conceptualize and assess the boundaries of cognitive enhancement. Fourth, the modest effects of antipsychotic medications on cognition suggest that additional psychopharmacological (and/or cognitive behavioral) interventions could add to their beneficial effects. The administration of adjunct treatments to antipsychotic medications, described above, emphasizes this point. The modest benefits of these attempts stress the early stage of the effort and the need for systematic study of potential mechanisms that could be utilized to promote memory facilitation. One such example, glucose administration, is considered next.

Glucose Administration and Memory

Overview

Effects of glucose on memory have been studied systematically for over 20 years in rodents and humans. The essential finding is that glucose, administered shortly before or after a training experience or prior to memory retrieval, improves memory for recent experiences in rodents, pigeons, and humans.137–145 Moreover, modest increases in circulating glucose improve memory in people with a variety of memory-impairing conditions such as normal aging,144,146,147 Alzheimer disease,148,149 Down syndrome,150 pretreatment with scopolamine or morphine,151,152 infantile amnesia,153,154 prenatal exposure to alcohol,155 and schizophrenia.12,156,157 The most consistently reported effect of glucose in studies with humans involves improvements in verbal declarative memory, as measured by recall of either narrative prose or of a list of words. Other manipulations (eg, emotionally arousing pictures) that increase blood glucose in young subjects also enhance recall.158,159 Several researchers noted that facilitation of memory by glucose is related to “cognitive demand”, whereby greater task difficulty is associated with greater facilitation of performance.160 A number of observations are consistent with this view. First, cognitively impaired older subjects often show more improvement after glucose administration than healthy older subjects,147 and tests that are amenable to facilitation by glucose in healthy older subjects may not show any improvement in younger subjects.144–146,161 Second, the facilitation of memory by glucose administration is usually greater on delayed recall than on immediate recall in tests of verbal memory (ie, delayed recall is more difficult).162 Third, some studies report lowered peripheral blood glucose levels after a demanding task.163 Although relationships between peripheral and central glucose utilization need clarification, the finding is consistent with the view that central resources are being used in performing the cognitive task. Fourth, nonmnemonic cognitive tasks that are facilitated by glucose, such as tests of attention, tend to be cognitively demanding.160,163–166 Taken together, these results from healthy adult subjects suggest that glucose availability is most useful in facilitating declarative memory when cognitive resources are in demand. In these circumstances, the magnitude of the effect is often large (eg, d ≥ 0.90),160,162,166–169 which supports its use as a heuristic intervention to reduce large (effect sizes ≥ 0.9) cognitive deficits in schizophrenia.23,35

Glucose Regulation and Memory

The above discussion suggests that memory performance may be related to glucose availability. Although, as noted, peripheral glucose administration is not always predictive of central glucose metabolism,145,170 there are several examples in which poor blood glucose regulation (and, presumably, availability) is related to poor memory. Among these are cognitive deficits that include verbal declarative memory in individuals with diabetes.171,172 At least some cognitive deficits, including memory, are reversed in patients with diabetes following administration of oral hypoglycemic agents and other treatments to normalize blood glucose levels.173–175 Second, glucose regulation and memory have been explored in the absence of diabetes. Several (though not all) studies involving aged subjects found that better recall of recently acquired information was associated with better glucose regulation (usually defined as the extent that blood glucose rises after an oral glucose challenge in a fasted subject, with small rises or quicker returns to baseline denoting better regulation in individual subjects).146,149,161,169,176–182 Stone et al183 obtained a parallel finding in old rats. Studies in younger subjects demonstrate more variable relationships between verbal declarative memory performance and glucose regulation than older subjects.145 They occur most reliably, however, when the task demands are relatively high for the healthy subjects.143,166,169,184 In one of these studies, glucose administration particularly improved memory in young subjects with poorer regulation.143 In another study by the same group,184 glucose administration improved memory only on the most difficult task.

Mechanisms of Glucose Actions

The mechanisms by which glucose modulates brain function, including memory, are multifactorial.145,185–188 Of particular importance to the current discussion is whether glucose administration and utilization modulate memory functions in ways that are direct or proximal enough to justify their exploration as treatment targets for impaired verbal declarative memory in schizophrenia. Among the reasons to question this assumption is the hypothesis that other influences, such as insulin, are either more proximal or more significant in explaining observed effects of glucose.

Glycogen storage in astrocytes, eg, is sensitive to insulin levels, possibly through modulation of glycogen synthase.189 This is potentially significant, in part, because levels of glycogenolysis in astrocytes have been shown to influence memory performance190 and also because astrocytes participate significantly in brain glucose uptake and metabolism, including glutamate-induced glycolysis and lactate production, which is transferred to neurons and oxidized via pyruvate in the tricarboxylic acid cycle to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (ie, “fuel”).186,187 Astrocytic glycolysis also has a stochiometic relationship to glutamate metabolism via the glutamate-glutamine cycle, with 1 glutamate molecule cycled for each glucose molecule metabolized to lactate.186,187 Insulin may thus modulate the availability of glucose used as fuel in neurons, including the availability of glucose used for the synthesis or metabolism of neurotransmitters involved in cognition, including memory (eg, glutamate, γ-aminobutyric acid).

Moreover, insulin administration itself may enhance memory (eg, Watson and Craft,188 Benedict et al,191 Craft et al,192 Kern et al193). Craft et al192 also demonstrated that insulin improved memory when glucose levels were kept constant at euglycemic levels through clamping procedures. It is important to note, however, that Craft et al192 did administer glucose to keep glycemic levels constant and that other findings show improved memory after administration of glucose or glucose analogs in the absence of increases in blood glucose.145,185,194

These findings show that parsing out the biological effects of glucose from those of insulin is often difficult due to multiple levels of interaction. Nevertheless, the modulation of memory or other aspects of brain function by insulin does not, by itself, support the conclusion that glucose effects may be explained as functions of insulin. In contrast, multiple studies show that glucose has direct effects in brain that are related to memory modulation, including paradigms in which microinjections of glucose or its metabolites were made into specific brain regions in animals and performance measured on specific tasks.185 Some of these studies showed that these microinjections improved memory by modulating neuronal excitability in specific regions by regulating ATP-sensitive potassium channels.195,196 Moreover, some factors that facilitate glucose effects (and improve memory), such as epinephrine administration, inhibit insulin. Other catecholamines, such as norepinephrine, have similar effects and also decrease astrocytic glycogen while increasing intracellular glucose and lactate levels.186 Finally, brain glucose uptake and metabolism are largely insulin-independent processes in humans,197 despite exceptions.189 Taken together, these findings support the view that glucose effects on memory are best conceptualized at this point in terms of their direct effects on brain function, rather than by the actions of insulin.

Glucose, Declarative Memory, and Medial Temporal Lobe Function

The literature on glucose effects on memory supports the following generalizations: (1) glucose improves verbal declarative memory in a variety of conditions and paradigms; (2) glucose is more effective when the task is difficult or demanding, which may mean that it is most effective when brain regions that process declarative memory are active; (3) poor glucose availability to relevant brain regions is associated with poor memory; and (4) additional glucose administration near the time of memory processing (eg, encoding or retrieval) may compensate for poor glucose availability in memory-impaired subjects or enhance processing ability in normal subjects.

The effect of glucose on memory is part of a broader spectrum of effects it exerts on brain and behavioral functions.142 Converging evidence across methodologies and species show that the medial temporal lobe, which is strongly involved in declarative memory,14,78 is particularly sensitive to glucose administration during learning and memory, especially in the presence of deficits in declarative memory performance.152,198–201 Although the findings do not identify the mechanisms by which the facilitation occurs, they are consistent with recent studies in rats showing that selective reductions in extracellular hippocampal glucose concentrations varied with the cognitive demand associated with different spatial memory tasks.170 The presence of these local decreases provides evidence that extracellular glucose is relatively compartmentalized and that greater demand during memory processing (presumably with more difficult tasks creating greater demand) produces a local extracellular glucose deficit that may be attenuated with glucose administration.170 It is particularly relevant that deficits in local glucose concentrations are greater and longer lasting under some conditions associated with poor memory, such as aging.200 The ability of glucose to improve memory under these circumstances may thus reflect its ability to reverse local deficits caused by cognitive activity involving the hippocampal and parahippocampal regions. It is of interest that intraseptal infusions of a drug (morphine) that impairs memory performance on a hippocampal-dependent task also prevents extracellular glucose reductions.201 Coadministration of glucose plus morphine both attenuates the memory deficit and results in reduced extracellular glucose levels. These findings raise the possibility of extracellular glucose levels as a marker of hippocampal function during learning.

A Model of Vulnerability to Memory Dysfunction in Schizophrenia

Glycemic Dyscontrol in Schizophrenia

The foregoing discussion provides evidence that poor glucose regulation or availability is associated with poor memory performance in a number of circumstances in rodents and humans. This raises the question of whether it is disturbed or vulnerable in schizophrenia. Several converging lines of evidence support this possibility, including (1) reports of impaired glucose regulation prior to the introduction of antipsychotic medications,202 and later, in unmedicated patients,203 patients treated with typical neuroleptic medications,204 and patients treated with newer antipsychotics205–208; (2) recent reports of elevated levels of diabetes in schizophrenia, compared with the general population (eg, Mukherjee et al,209 Subramaniam et al210), and impaired glucose regulation during first-episode psychosis in drug-naïve patients211; (3) elevated rates of type 1212,213 and type 2209,214 diabetes in the relatives of patients with schizophrenia; (4) an analysis from our laboratory showing evidence of genetic linkage between 3 regulatory enzymes involved in glycolysis and schizophrenia, including 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 2 (PFKFB2; chromosome 1q32.2), hexokinase 3 (HK3; chromosome 5q35.3), and pyruvate kinase 3 (PK3; chromosome 15q23)215; (5) an exaggerated glucose response to a metabolic challenge of 2-deoxyglucose in schizophrenia216; (6) common prepregnancy or pregnancy risk factors (including maternal diabetes) for schizophrenia and diabetes conditions217–219; (7) similarities in the multifactorial, polygenetic nature of schizophrenia and diabetes220–224; and (8) enhancement of verbal declarative memory in individuals with schizophrenia.

At least 3 published studies have thus far demonstrated enhanced memory performance in subjects with schizophrenia. Newcomer et al156 showed that an oral dose of glucose improved verbal declarative memory in a group of patients with schizophrenia but not in a group with bipolar disorder or in a healthy control group. The same group also reported improvements in spatial memory and processing speed in older (but not younger) patients.157 In both studies, subjects were stabilized on a variety of different antipsychotic medications. In the third study, we showed that glucose improved retention for a list of words in chronic patients who were stabilized clinically on clozapine (and in most cases, additional medications).12 Consistent with these findings, we demonstrated that the same dose of glucose that improved retention for the list of words also activated specific brain regions (eg, the left parahippocampus) during a verbal encoding task in a functional magnetic resonance imaging task (fMRI), compared with saccharin administration.225

While it is premature to conclude that glucose dysfunction is either necessary or sufficient to produce impaired memory in schizophrenia or that memory improvement following glucose administration implies underlying glucose dysfunction, these findings, taken together, are consistent with the hypothesis that glucose dysregulation occurs in schizophrenia and adds to the liability for memory dysfunction.

Disturbed glucose function in some patients with schizophrenia, in light of the importance of glucose regulation for cognition and brain function, also highlights a need to identify neurochemical factors that modulate glucose function. Among the most important of these are hormones/neurotransmitters that regulate glucose normally but function abnormally in schizophrenia. These include insulin/insulin resistance,226–228 cortisol,227,229 epinephrine, and norepinephrine.114,216,230 Because each of these hormones is disturbed in schizophrenia and influences glucose regulation and availability, it is likely that one or more of them interact with and contribute to effects attributed to glucose, as discussed above. Moreover, attention to these hormones is made more salient by numerous studies showing that each of them is related to learning and memory performance.231,232 For each of these reasons, they may contribute to and influence the “boundaries” of glucose effects.

A Model of Memory Enhancement and Hippocampal Function in Schizophrenia

As noted above, the mechanisms by which glucose facilitates hippocampal function are unclear. It is likely that multiple mechanisms are involved. For example, we and other groups have shown that glucose facilitates central cholinergic function, including hippocampal cholinergic function, during learning.152,198,199,233 It is also likely that factors that modulate glucose metabolism and function, such as insulin and cortisol,211,234–236 mediate its function to some extent. Wenk237 proposed that the role of glucose in the biosynthesis of a variety of neurotransmitters (eg, glutamate) may be related to its positive effects on memory. Moreover, glucose interactions with dopamine238–242 may be especially relevant for understanding both cognitive and clinical aspects of schizophrenia. Nevertheless, several lines of evidence discussed above point to the likelihood that elevated rates of poor glucose regulation may contribute to poor encoding and/or retrieval on tests of memory. One important question is whether poor glucose regulation is sufficient to produce memory deficits in schizophrenia. Although relatively poorer memory is associated with relatively poorer glucose regulation in healthy young adults in some studies,143 it seems unlikely that the subjects would be classified as having clinically significant deficits. Even young people with diabetes usually show little evidence of memory impairment.171 Older diabetic individuals, however, show more reliable deficits compared with age-matched controls.171 These findings suggest that in the absence of other impairing factors, poor glucose regulation alone may not suffice to produce memory impairment. In schizophrenia, however, other factors may be related to poor memory.

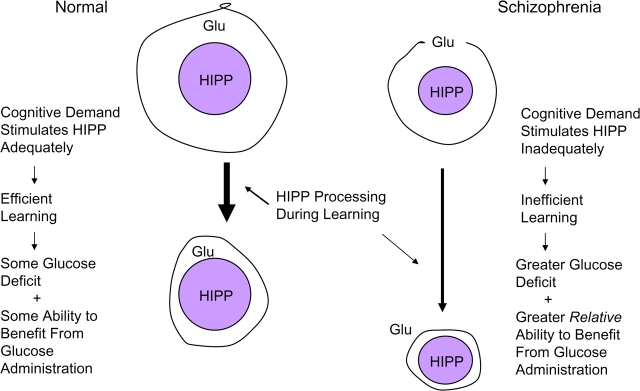

One of these, as discussed above, involves smaller hippocampi with fewer dendritic processes that are less sensitive to experiential stimuli that would normally produce adaptive, plastic responses (eg, encoding or retrieving new information).60 Interestingly, poor glucose regulation in nondemented, nondiabetic elderly people is associated with both poor memory and with smaller hippocampal volumes.180 In this context, lowered glucose availability, combined with a smaller, relatively inefficient hippocampus to utilize the glucose when it is available, may create or exacerbate local glucose deficits during the relatively extended periods of demand that coincide with inefficient learning (eg, slow learning) or retrieval. A representation of this view is illustrated in figure 1. We hypothesize that a normal hippocampus is stimulated to respond adequately by an appropriate cognitive demand, which leads to efficient learning. Extracellular glucose (GLU) is utilized by the hippocampus in the process, which results in a somewhat depleted store. The depletion increases sensitivity to glucose administration, which reverses the depletion, facilitates hippocampal function, and contributes to cognitive enhancement.

Fig. 1.

A Model of Glucose Enhancement in Schizophrenia.

In schizophrenia, we hypothesize that a smaller hippocampus that is “sluggish” or difficult to recruit will also be less efficient when it is recruited, which results in inefficient learning and ultimately a larger expenditure of glucose. This results in a larger extracellular glucose deficit and a correspondingly greater relative sensitivity to exogenous glucose administration. This view is consistent with observations from our laboratory and others showing that reduced performance of schizophrenic patients and their first-degree relatives on working memory tasks is associated with exaggerated activation in several regions, including the prefrontal cortex.243,244

In this model, Heckers' demonstration of poor hippocampal recruitment after encoding80 may reflect both a cause and/or an effect of poor hippocampal function; eg, prefrontal input may be impaired while the threshold for stimulation in an inefficient hippocampus may be higher than normal. If this view of the hippocampus in schizophrenia is correct, then abnormal hippocampal function could thus express itself through either less task-dependent activation than normal (eg, hippocampal inputs or recruitment did not rise to abnormally high threshold levels in a consistent manner) or through more activity-dependent activation than normal (eg, once a higher threshold for activity is met, greater than normal, but less regulated, levels of activity ensue). Either instance, however, is associated with inefficient learning and memory and with a partially reversible deficit in glucose availability.

Interestingly, positron emission tomography (PET) studies provide evidence that is consistent with the possibility that glucose uptake and/or metabolism may be altered in schizophrenia. One difference is that global decreases in uptake and metabolism have not been reported, to our knowledge, as they have been in diabetes.245 Consistent with the hypothesis of impaired regulation, however, are reports of both increased and decreased metabolic rates for glucose in different brain regions,246 including decreased rates in the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus247 and in temporal regions248 during verbal learning tasks.

Summary and Conclusions

This postulation of cognitive dysfunction and enhancement involving glucose regulation and administration is useful because it provides evidence that a simple intervention can serve as a heuristic model for improving memory and brain function in schizophrenia. Its emphasis here illustrates the potential value of focusing cognitive enhancement efforts on specific cognitive impairments in schizophrenia to facilitate advances in those areas, beyond levels that are likely to be associated with antipsychotic medications alone in the foreseeable future. The model also emphasizes the importance of translational research in developing and testing hypotheses and in identifying brain mechanisms involved in cognition that also map onto the neuropathology of schizophrenia.

Because no standard treatments for memory dysfunction have yet emerged, many unanswered questions remain. One that derives directly from the glucose model is whether factors that regulate or modulate glucose function, such as insulin, also enhance declarative memory. More generally, basic issues concern how and whether pharmacological interventions for memory (or other cognitive abilities) interact with specific antipsychotic medications and/or cognitive behavioral strategies to produce optimal levels of enhancement. It is likely that glucose administration itself, or other interventions that may cause or add to medication-induced hyperglycemia, will not be suitable as clinical treatments. Progress in the near future is likely to come from multiple sources, including attempts to translate findings in rodents or other nonhuman species to humans, using fMRI, PET scans, and other forms of neuroimaging. Glucose availability during learning in humans, eg, might be controlled with insulin-clamping procedures and assessed with hippocampal fMRI. Efforts aimed at increasing astrocytic glycogen storage, which would allow a larger supply of glucose in response to activity-dependent demands, along with other strategies aimed at improving glucose regulation in schizophrenia, offer encouraging avenues for exploration.

The robust nature of problems in learning and memory in schizophrenia raise basic questions about the efficacy of synaptic plasticity in schizophrenia and genetic and epigenetic mechanisms that control levels of plasticity. At some point, it will be important—and feasible—to link models of declarative memory dysfunction (and its potential treatments) to deficits in short-term forms of plasticity such as sensory gating paradigms (eg, p50 and prepulse inhibition) in addition to the longer term forms of plasticity inherent in declarative memory. Eventually, as genes involved in schizophrenia are identified (eg, Callicott et al,249 Blasi et al250), epigenetic modification of target genes through environmental and psychopharmacological interventions may serve to modify gene expression and function in ways that will lead to adaptive modifications in neuronal signaling pathways and in declarative memory. Steps in this direction would include explorations of whether putative cognitive enhancers such as glucose administration increase transcription factors such as c-fos, cyclic AMP-responsive element binding protein (CREB), or brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and alter gene expression in schizophrenia.

Cognitive enhancement in schizophrenia is at an early stage. However, interest in the field has increased greatly, and together with increased utilization of conceptual models to understand the nature, possibilities, and limits of cognitive improvement, better cognitive outcomes in schizophrenia are becoming increasingly more likely.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIMH (MH 43518, MH65562, and MH 63951 to Seidman), the National Association for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (Seidman), the Mental Illness and Neuroscience Discovery (Seidman) Institute, and the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health Commonwealth Research Center (Seidman).

References

- 1.Green MF. What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:321–330. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:119–136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carpenter WT, Gold JM. Another view of therapy for cognition in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:969–971. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01399-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujii DE, Wylie AM. Neurocognition and community outcome in schizophrenia: long-term predictive validity. Schizophr Res. 2002;59:219–223. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00328-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma T, Antonova L. Cognitive function in schizophrenia: deficits, functional consequences, and future treatment. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2003;26:25–40. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(02)00084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harvey PD, Keefe RSE. Cognition and the new antipsychotics. J Adv Schizophr Brain Res. 1998;1:2–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma T, Mockler D. The cognitive efficacy of atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998;18(suppl):12s–19s. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199804001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green MF, Braff DL. Translating the basic and clinical cognitive neuroscience of schizophrenia to drug development and clinical trials of antipsychotic medications. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:374–384. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGurk SR. The effects of clozapine on cognitive functioning in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 12):24–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bilder RM, Goldman RS, Volavka J, et al. Neurocognitive effects of clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in patients with chronic schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1018–1028. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyman SE, Fenton WS. What are the right targets for psychopharmacology? Science. 2003;299:350–351. doi: 10.1126/science.1077141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stone WS, Seidman LJ, Wojcik JD, Green AI. Glucose effects on cognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2003;62:93–103. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00406-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harvey PD, Geyer MA, Robbins TW, Krystal JH. Cognition in schizophrenia: from basic science to clinical treatment. Psychopharmacology. 2003;169:213–214. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1581-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broadbent NJ, Clark RE, Zola S, Squire LR. The medial temporal lobe and memory. In: Squire LR, Schacter DL, editors. Neuropsychology of Memory. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2002. pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seidman LJ. Schizophrenia and brain dysfunction: an integration of recent neurodiagnostic findings. Psychol Bull. 1983;94:195–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nuechterlein KH, Dawson ME. A heuristic vulnerability/stress model of schizophrenic episodes. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10:300–312. doi: 10.1093/schbul/10.2.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saykin AJ, Gur RC, Gur RE, et al. Neuropsychological function in schizophrenia. selective impairment in memory and learning. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:618–624. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810310036007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinrichs RW, Zakzanis KK. Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology. 1998;12:426–445. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.12.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seidman LJ, Stone WS, Jones R, Harrison RH, Mirsky AF. Cognitive effects of schizophrenia and temporal lobe epilepsy on memory. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1998;4:342–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kremen WS, Seidman LJ, Faraone SV, Toomey R, Tsuang MT. The paradox of normal neuropsychological function in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:743–752. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seidman LJ, Faraone SV, Goldstein JM, et al. Left hippocampal volume as a vulnerability indicator for schizophrenia: a magnetic resonance imaging morphometric study of nonpsychotic first-degree relatives. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:839–849. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.9.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nuechterlein KH, Barch DM, Gold JM, Goldberg TE, Green MF, Heaton RK. Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;72:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heinrichs RW. The primacy of cognition in schizophrenia. Am Psychol. 2005;60:229–242. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bromley E. A collaborative approach to targeted treatment development for schizophrenia: evaluation of the NIMH-MATRICS project. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31:954–961. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Auerbach J, Hans S, Marcus J. Neurobehavioral functioning and social behavior of children at risk for schizophrenia. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 1993;30:40–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirsky AF, Yardley SL, Jones BP, Walsh D, Kendler KS. Analysis of the attention deficit in schizophrenia: a study of patients and their relatives in Ireland. J Psychiatr Res. 1995;29:23–42. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)00041-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erlenmeyer-Kimling L, Rock D, Roberts SA, et al. Attention, memory, and motor skills as childhood predictors of schizophrenia-related psychoses: the New York High-Risk Project. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1416–1422. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.9.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erlenmeyer-Kimling L. Neurobehavioral deficits in offspring of schizophrenic parents: liability indicators and predictors of illness. Am J Med Genet (Neuropsychiatr Genet) 2000;97:65–71. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(200021)97:1<65::aid-ajmg9>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mirsky AF, Duncan CC. A neuropsychological perspective on vulnerability to schizophrenia: lessons from high-risk studies. In: Stone WS, Faraone SV, Tsuang MT, editors. Early Clinical Intervention and Prevention in Schizophrenia. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2004. pp. 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stone WS, Faraone SV, Seidman LJ, Olson EA, Tsuang MT. Searching for the liability to schizophrenia: concepts and methods underlying genetic high-risk studies of adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15:403–417. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bilder RM, Lipschutz-Broch L, Reiter G, Geisler SH, Mayerhoff DI, Lieberman JA. Intellectual deficits in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1992;18:437–448. doi: 10.1093/schbul/18.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saykin AJ, Shtasel DL, Gur RE, et al. Neuropsychological deficits in neuroleptic naive patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:124–131. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950020048005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spohn HE, Strauss ME. Relation of neuroleptic and anticholinergic medication to cognitive functions in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1989;98:367–380. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.98.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sweeney JA, Haas GL, Keilp JG, Long M. Evaluation of the stability of neuropsychological functioning after acute episodes of schizophrenia: one-year followup study. Psychiatry Res. 1991;38:63–76. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(91)90053-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cirillo MA, Seidman LJ. Verbal declarative memory dysfunction in schizophrenia: from clinical assessment to genetics and brain mechanisms. Neuropsychol Rev. 2003;13:43–77. doi: 10.1023/a:1023870821631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levin S, Yurgelun-Todd D, Craft S. Contributions of clinical neuropsychology to the study of schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1989;98:341–356. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.98.4.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blanchard JJ, Neale JM. The neuropsychological signature of schizophrenia: generalized or differential deficit? Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:40–48. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gold JM. Cognitive deficits as treatment targets in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;72:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aleman A, Hijman R, de Haan EH, Kahn RS. Memory impairment in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1358–1366. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beatty WW, Jocic Z, Monson N, Staton D. Memory and frontal lobe dysfunction in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993;181:448–453. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199307000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gold J, Randolph C, Carpenter C, Goldberg T, Weinberger D. Forms of memory failure in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1992;101:487–494. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.3.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paulsen JS, Heaton RK, Sadek JR, et al. The nature of learning and memory impairments in schizophrenia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1995;1:88–99. doi: 10.1017/s135561770000014x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heaton R, Paulsen JS, McAdams LA, et al. Neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenics. Relationship to age, chronicity, and dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:469–476. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950060033003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seidman LJ, Cassens GP, Kremen WS, Pepple JR. Neuropsychology of schizophrenia, in clinical syndromes in adult neuropsychology. In: White RF, editor. The Practitioner's Handbook. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers B.V.,; 1992. pp. 381–450. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brebion G, Amador X, Smith MJ, Gorman JM. Mechanisms underlying memory impairment in schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 1997;27:383–393. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weiss AP, Heckers S. Neuroimaging of declarative memory in schizophrenia. Scand J Psychol. 2001;42:239–250. doi: 10.1111/1467-9450.00234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brebion G, Bressan RA, Amador X, Malaspina D, Gorman JM. Medications and verbal memory impairment in schizophrenia: the role of anticholinergic drugs. Psychol Med. 2004;34:369–374. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Joyce E. Origins of cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia: clues from age at onset. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;86:93–95. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Faraone SV, Seidman LJ, Kremen WS, Pepple JR, Lyons MJ, Tsuang MT. Neuropsychological functioning among the nonpsychotic relatives of schizophrenic patients: a diagnostic efficiency analysis. J Abnorm Psychol. 1995;104:286–304. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Faraone SV, Seidman LJ, Kremen WS, Toomey R, Pepple JR, Tsuang MT. Neuropsychological functioning among the nonpsychotic relatives of schizophrenic patients: a four-year follow-up study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1999;108:176–181. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Faraone SV, Seidman LJ, Kremen WS, Toomey R, Pepple JR, Tsuang MT. Neuropsychological functioning among the nonpsychotic relatives of schizophrenic patients: the effect of genetic loading. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:120–126. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kremen WS, Hoff AL. Neurocognitive deficits in the biological relatives of individuals with schizophrenia. In: Stone WS, Faraone SV, Tsuang MT, editors. Early Clinical Intervention and Prevention with Schizophrenia. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2004. pp. 133–158. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eichenbaum H. The hippocampal system and declarative memory in humans and animals: experimental analysis and historical origins. In: Schacter D, Tulving E, editors. Memory Systems. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press; 1994. pp. 147–201. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eichenbaum H. Memory representations in the parahippocampal region. In: Witter M, Wouterlood F, editors. The Parahippocampal Region: Organization and Role in Cognitive Function. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 165–184. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Freedman R, Adams CE, Adler LE, et al. Inhibitory neurophysiological deficit as a phenotype for genetic investigation of schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet (Neuropsychiatr Genet) 2000;97:58–64. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(200021)97:1<58::aid-ajmg8>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davison K, Bagley C. Schizophrenia-like psychoses associated with organic disorders of the central nervous system: a review of the literature. Br J Psychiatry. 1969;4:113–184. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shenton ME, Dickey CC, Frumin M, McCarley RW. A review of MRI findings in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001;49:1–52. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00163-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weinberger DR, Berman KF, Suddath R, Torrey EF. Evidence of dysfunction of a prefrontal-limbic network in schizophrenia: a magnetic resonance imaging and regional cerebral blood flow study of discordant monozygotic twins. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:890–897. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.7.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harrison PJ. The hippocampus in schizophrenia: a review of the neuropathological evidence and its pathophysiological implications. Psychopharmacology. 2004;174:151–162. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1761-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weinberger DR. Cell biology of the hippocampal formation in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:395–402. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00331-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lawrie SM, Whalley HC, Abukmeil SS, et al. Brain structure, genetic liability, and psychotic symptoms in subjects at high risk of developing schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:811–823. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seidman LJ, Pantelis C, Keshavan MS, et al. A review and a new report of medial temporal lobe dysfunction as a vulnerability indicator for schizophrenia: a MRI morphometric family study of the parahippocampal gyrus. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:803–808. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seidman LJ, Wencel HE, McDonald C, Murray RM, Tsuang MT. Neuroimaging studies of nonpsychotic first-degree relatives of people with schizophrenia. In: Stone WS, Faraone SV, Tsuang MT, editors. Early Clinical Intervention and Prevention in Schizophrenia. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2004. pp. 179–210. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Benes FM, Kwok EW, Vincent SL, Todtenkopf MS. A reduction of nonpyramidal cells in sector CA2 of schizophrenics and manic depressives. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:88–97. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00138-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bogerts B. The temporolimbic system theory of positive schizophrenic symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23:423–435. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kraepelin E. Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia. Huntington, New York, NY: Robert Krieger; 1919/1971. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lipska BK, Weinberger DR. To model a psychiatric disorder in animals: schizophrenia as a reality test. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:223–239. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rajarethinam R, DeQuardo JR, Miedler J, et al. Hippocampus and amygdala in schizophrenia: assessment of the relationship of neuroanatomy to psychopathology. Psychiatry Res: Neuroimaging Sect. 2001;108:79–87. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(01)00120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rajarethinam R, Sahni S, Rosenberg DR, Keshavan MS. Reduced superior temporal gyrus volume in young offspring of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1121–1124. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Beyer JL, Kuchibhatla M, Payne ME, et al. Hippocampal volume measurement in older adults with bipolar disorder. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12:613–620. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.12.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blumberg HP, Kaufman J, Martin A, et al. Amygdala and hippocampal volumes in adolescents and adults with bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1201–1208. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.12.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Videbach P, Ravnkilde B. Hippocampal volume and depression: a meta-analysis of MRI studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1957–1966. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brambilla P, Harenski K, Nocoletti M, et al. MRI investigation of temporal lobe structures in bipolar patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:287–295. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(03)00024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nelson M, Saykin A, Flashman L, Riordan H. Hippocampal volume reduction in schizophrenia as assessed by magnetic resonance imaging: a meta-analytic study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:433–440. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.5.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Torrey EF, Barci BM, Webster MJ, Bartko JJ, Meador-Woodruff JH. Neurochemical markers for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression in postmortem brains. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:252–260. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schacter DL. Memory, amnesia and frontal lobe dysfunction. Psychobiology. 1987;15:21–36. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wheeler MA, Stuss DT, Tulving E. Frontal lobe damage produces episodic memory impairment. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1995;1:525–536. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700000655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wagner AD. Cognitive control and episodic memory: contributions from prefrontal cortex. In: Squire LR, Schacter DL, editors. Neuropsychology of Memory. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2002. pp. 174–192. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Goldman-Rakic P. Cerebral cortical mechanisms in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1994;10:22S–27S. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Heckers S, Rauch SL, Goff D, et al. Impaired recruitment of the hippocampus during conscious recollection in schizophrenia. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:318–323. doi: 10.1038/1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Barch DM, Csernansky JG, Conturo T, Snyder AZ. Working and long-term memory deficits in schizophrenia: is there a common prefrontal mechanism? J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111:478–494. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.3.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Berman KF. Functional neuroimaging in schizophrenia. In: Davis KL, Charney D, Coyle JT, Nemeroff C, editors. Neuropsychopharmacology: The Fifth Generation of Progress. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002. pp. 745–756. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Weiss AP, Schacter DL, Goff DC, Rausch SL, Alpert NM, Heckers S. Impaired hippocampal recruitment during normal modulation of memory performance in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:48–55. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01541-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Seidman LJ, Yurgelun-Todd D, Kremen WS, et al. Relationship of prefrontal and temporal lobe MRI measures to neuropsychological performance in chronic schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1994;35:235–246. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)91254-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Davidson PSR, Troyer AK, Moscovitch M. Frontal lobe contributions to recognition and recall: linking basic research with clinical evauation and remediation. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2006;12:210–223. doi: 10.1017/S1355617706060334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stuss DT, Alexander MP, Shallice T, et al. Multiple frontal systems controlling response speed. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43:396–417. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Braver TS, Barch DM. A theory of cognitive control, aging, cognition and neuromodulation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26:809–817. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cassens G, Inglis AK, Appelbaum PS, Gutheil TG. Neuroleptics: effects on neuropsychological function in chronic schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Bull. 1990;16:477–499. doi: 10.1093/schbul/16.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mishara AL, Goldberg TE. A meta-analysis and critical review of the effects of conventional neuroleptic treatment on cognition: opening a closed book. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:1013–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Thornton AE, Van Snellenberg JX, Sepehry AA, Honer W. The impact of atypical antipsychotic medications on long-term memory dysfunction in schizophrenia spectrum disorder: a quantitative review. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20:335–346. doi: 10.1177/0269881105057002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stip E. The effect of risperidone on cognition in patients with schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 1996;41:S35–S40. doi: 10.1177/070674379604100802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Keefe RS, Silva SG, Perkins DO, Lieberman JA. The effects of atypical antipsychotic drugs on neurocognitive impairment in schizophrenia: a review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:201–222. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Meltzer H, McGurk S. The effect of clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine on cognitive function in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:233–255. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kern R, Green M, Marshall B, et al. Risperidone vs. haloperidol on secondary memory: can newer antipsychotic medications aid learning? Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:223–232. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Purdon SE, Jones BD, Stip E, et al. Neuropsychological change during early phase schizophrenia during 12 months of treatment with olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol. The Canadian Collaborative Group for research in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:249–258. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Harvey PD, Keefe RSE. Studies of cognitive change in patients with schizophrenia following novel antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:176–184. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Harvey PD, Green MF, McGurk SR, Meltzer HY. Changes in cognitive functioning with risperidone and olanzepine treatment: a large-scale, double-blind, randomized study. Psychopharmacology. 2003;169:404–411. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1342-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Weickert CS, Kleinman JE. The neuroanatomy and neurochemistry of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1998;21:57–75. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70361-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Velligan DI, Prihoda TJ, Sui D, Ritch JL, Maples N, Miller AL. The effectiveness of quetiapine versus conventional antipsychotics in improving cognitive and functional outcomes in standard settings. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:524–531. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Keefe RSE, Seidman LJ, Christensen BK, et al. Long-term neurocognitive effects of olanzapine or low-dose haloperidol in first-episode psychosis. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Weickert TW, Goldberg TE, Marenco S, Bigelow LB, Egan MF, Wienberger DR. Comparison of cognitive performances during a placebo period and an atypical antipsychotic treatment period in schizophrenia: critical examination confounds. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1491–1500. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Meltzer HY. Mechanisms of action of atypical antipsychotic drugs. In: Davis KL, Charney D, Coyle JT, Nemeroff C, editors. Neuropsychopharmacology: The Fifth Generation of Progress. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkens; 2002. pp. 819–831. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lenzi A, Maltini E, Poggi E, Fabrizio L, Coli E. Effects of rivastigmine on cognitive function and quality of life in patients with schizophrenia. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2003;26:317–321. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200311000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Buchanan RW, Summerfelt A, Tek C, Gold J. An open-labeled trial of adjunctive donepezil for cognitive impairments in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2003;59:29–33. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00387-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Friedman JI, Adler DN, Howanitz E, et al. A double blind placebo controlled trial of donepezil adjunctive treatment to risperidone for the cognitive impairment of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:349–357. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01342-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tual N, Yazc KM, Yacolu AE, Gogus A. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial of adjunctive donepezil for cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004;7:117–123. doi: 10.1017/S1461145703004024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Freudenreich O, Herz L, Deckersbach T, et al. Added donepezil for stable schizophrenia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Psychopharmacology. 2005;181:358–353. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2235-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kumari V, Aasen I, Ffytche D, Williams SCR, Sharma T. Neural correlates of adjunctive rivastigmine treatment to antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2006;29:545–556. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Levkovitz Y, Ophir-Shaham O, Bloch Y, Treves I, Fennig S, Grauer E. Effect of L-tryptophan on memory in patients with schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191:568–573. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000087182.29781.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Levkovitz Y, Arnest G, Mendlovic S, Treves I, Fennig S. The effect of ondansetron on memory in schizophrenic patients. Brain Res Bull. 2005;65:291–295. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2003.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Poyurovsky M, Koren D, Gonopolsky I, et al. Effect of 5-HT2 antagonist mianserin on cognitive dysfunction in chronic schizophrenia patients: an add-on, double-blind placebo-controlled study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;13:123–128. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(02)00155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Turner DC, Clark L, Pomarol-Clotet E, McKenna P, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ. Modafinil improves cognition and attentional set shifting in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1363–1373. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Friedman JI, Adler DN, Temporini HD, et al. Guanfacine treatment of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:402–409. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00249-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Friedman JI, Stewart DG, Gorman JM. Potential noradrenergic targets for cognitive enhancement in schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2004;9:350–355. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900009330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Goldberg TE, Bigelow LB, Weinberger DR, Daniel DG, Kleinman JE. Cognitive and behavioral effects of the coadministration of dextroamphetamine and haloperidol in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:78–84. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Daniel DG, Weinberger DR, Jones DW, et al. The effect of amphetamine on regional cerebral blood flow during cognitive activation in schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 1991;11:1907–1917. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-07-01907.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Barch DM, Carter CS. Amphetamine improves cognitive function in medicated individuals with schizophrenia and in healthy volunteers. Schizophr Res. 2005;77:43–58. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hagan JJ, Jones DNC. Predicting drug efficacy for cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31:830–853. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gemperle AY, McAllister KH, Olpe H-R. Differential effects of iloperidone, clozapine and haloperidol on working memory of rats in the delayed non-matching-to-position paradigm. Psychopharmacology. 2003;169:354–364. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1459-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Terranova J-P, Chabot C, Barnoiun M-C, Depoortere R, Briebel G, Scatton B. SSR181507, a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist and 5-HT1A receptor agaonist, alleviates disturbances of novelty discrimination in a social context in rats, a putative model of selective attention deficit. Psychopharmacology. 2005;181:134–144. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.White NM, McDonald RJ. Multiple parallel memory systems in the brain of a rat. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2002;77:125–184. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2001.4008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Poldrack RA, Packard MG. Competition among multiple memory systems: converging evidence from animal and human brain studies. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41:245–251. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Gold PE. Acetylcholine modulation of neural systems involved in learning and memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2003;80:194–210. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gold PE. Coordination of multiple memory systems. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2004;82:230–242. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Myhrer T. Neurotransmitter systems involved in learning and memory in the rat: a meta-analysis based on studies of four behavioral tasks. Brain Res Rev. 2003;41:268–287. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00268-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Stone WS, Walser B, Gold SD, Gold PE. Scopolamine- and morphine-induced impairments of spontaneous alternation in rats: reversal with glucose and with cholinergic and adrenergic agonists. Behav Neurosci. 1991;105:264–271. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.105.2.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Stone WS, Rudd RJ, Gold PE. Glucose and physostigmine effects on morphine- and amphetamine-induced increases in locomotor activity in mice. Behav and Neural Biol. 1990;54:146–155. doi: 10.1016/0163-1047(90)91338-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Squire LR, Zola-Morgan S. The medial temporal lobe memory system. Science. 1991;253:1380–1386. doi: 10.1126/science.1896849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Cohen NJ, Eichenbaum H. Memory, Amnesia and the Hippocampal System. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Poldrack RA, Rodriguez P. How do memory systems interact? Evidence from human classification learning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2004;82:324–332. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Gabriele A, Packard MG. Evidence of a role for multiple memory systems in behavioral extinction. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2006;85:289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Whalley LJ, Deary IJ, Appleton CL, Starr JM. Cognitive reserve and the neurobiology of cognitive aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2004;3:369–382. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Stern Y, Habeck C, Moeller J, et al. Brain networks associated with cognitive reserve in healthy young and old adults. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:394–402. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Pai MC, Tsai JJ. Is cognitive reserve applicable to epilepsy? The effect of educational level on the cognitive decline after onset of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2005;46(suppl 1):7–10. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.461003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Le Carret N, Auriacombe S, Letenneur L, Bergua V, Dartigues JF, Fabrigoule C. Influence of education on the pattern of cognitive deterioration in AD patients: the cognitive reserve hypothesis. Brain Cogn. 2005;57:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Springer MV, McIntosh AR, Winocur G, Grady CL. The relations between brain activity during memory tasks and years of education in young and older adults. Neuropsychology. 2005;19:181–192. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.19.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Gold PE. Glucose modulation of memory storage processing. Behavior Neural Biol. 1986;45:342–349. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(86)80022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Gold PE, Vogt J, Hall JL. Glucose effects on memory: behavioral and pharmacological characteristics. Behav Neural Biol. 1986;46:145–155. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(86)90626-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Messier C, White NM. Contingent and non-contingent actions of sucrose and saccharin reinforcers: effects on taste preference and memory. Physiol Behav. 1984;32:195–203. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(84)90129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Messier C, White NM. Memory improvement by glucose, fructose and two glucose analogs: a possible effect of peripheral glucose transport. Behav Neural Biol. 1987;48:104–127. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(87)90634-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Gold PE, Stone WS. Neuroendocrine effects on memory in aged rodents and humans. Neurobiol Aging. 1988;9:709–717. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(88)80136-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Gold PE. Role of glucose in regulating the brain and cognition. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61(suppl):987S–995S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/61.4.987S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Messier C, Desrochers A, Gagnon M. Effect of glucose, glucose regulation and word imagery value on human memory. Behav Neurosci. 1999;113:431–438. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.113.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Korol DL. Enhancing cognitive function across the life span. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;959:167–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Messier C. Glucose improvement of memory: a review. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;490:33–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Hall JL, Gonder-Frederick LA, Chewning WW, Silveira J, Gold PE. Glucose enhancement of performance on memory tests in young and aged humans. Neuropsychologia. 1989;27:1129–1138. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(89)90096-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]