Abstract

Rates of tobacco use among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia have been estimated as high as 80%. A variety of hypotheses have been proposed to explain the high rate of tobacco use among this vulnerable group. This study examined the tobacco industry's efforts to establish and promulgate beliefs about schizophrenic individuals’ need to smoke and the hazards of quitting. The current study analyzed previously secret tobacco industry documents. The initial search was conducted during January–July 2005 in the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library. The search yielded 280 records dating from 1955 to 2004. Documents indicate the tobacco industry monitored or directly funded research supporting the idea that individuals with schizophrenia were less susceptible to the harms of tobacco and that they needed tobacco as self-medication. The tobacco industry promoted smoking in psychiatric settings by providing cigarettes and supporting efforts to block hospital smoking bans. The tobacco industry engaged in a variety of direct and indirect efforts that likely contributed to the slowed decline in smoking prevalence in schizophrenia via slowing nicotine dependence treatment development for this population and slowing the rate of policy implementation vis-à-vis smoking bans on psychiatric units.

Keywords: nicotine, smoking, cigarettes, psychiatry, mentally ill, tobacco companies

Introduction

Individuals with mental illness are one of the largest remaining groups of smokers, accounting for 44% to 46% of cigarettes sold in the United States.1,2 This equates to 180 billion cigarettes or $37 billion in tobacco industry sales annually.3,4 Tobacco use is particularly prevalent among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, with estimates ranging from 49% to 80%.2,5,6 A variety of hypotheses have been proposed to explain the high rate of tobacco use among this vulnerable group. Despite a lack of compelling scientific support, beliefs prevail that individuals with schizophrenia need to smoke as a form of self-medication; that quitting smoking will worsen their psychiatric symptoms; that they cannot and do not want to quit their tobacco use; and that they may hold some special immunity from tobacco-related diseases.7–10

This study examined the role the tobacco industry has played in promoting and maintaining cigarette use among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia. The tobacco industry documents provide insight into industry motives, strategies, tactics, and data.11 Prior research has reported on the tobacco industry's strategies to manipulate data on the health risks of smoking, including funding and publishing research that supports their position, suppressing research that does not support their position, and disseminating their data and interpretations to the lay press and policy makers.12 The current study examined evidence of these tactics in relation to the industry's efforts to establish and promulgate beliefs about schizophrenic individuals’ need to smoke and the hazards of quitting. An awareness of the tobacco industry's efforts to preserve smoking among individuals with schizophrenia is needed to better inform treatment and policy strategies.

METHODS

The 1998 Minnesota Consent Judgment and Master Settlement Agreement resulted in the public availability of nearly 40 million pages of the industry's internal documents. The initial search was conducted during January–July 2005 in the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library (http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/) using keyword terms “psychosis,” “psychotic,” or “schizo*.” (Use of an asterisk as a “wild card” character allows for a search of variations of word or phrases—in this case, schizophrenia, schizophrenic, and schizoaffective disorder.) The search yielded 280 records; the Council for Tobacco Research (CTR) archive provided the largest number of records with 130 hits (The CTR, formed by US tobacco companies in 1954 as the Tobacco Industry Research Committee (TIRC), was formed with the premise of funding research. Internal documents have revealed, however, that the TIRC served largely for public relations purposes, to convince the public that the hazards of smoking had not been proven13).

Expanded searches were prompted by clues identified in reviewed documents, including named individuals, specific programs, and expansion of dates and reference (BATES) numbers. Additional follow-up searches were conducted on tobacco document collection sites searchable by text words (http://tobaccodocuments.org/ and http://www.pmdocs.com/), including the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library, which obtained text word search capability in March 2006. Identified documents ranged in date from 1955 through the year 2004.

A postpositivist analytic approach was used,13 with findings organized into 3 main areas concerning tobacco industry (1) investigations of the health effects of smoking in individuals with schizophrenia, (2) research on the self-medication hypothesis specific to tobacco use and schizophrenia, and (c) involvement in policy efforts to maintain tobacco use in psychiatry settings. As relevant, we supplemented industry documents with recent research literature on tobacco use and schizophrenia. Lastly, we conducted systematic searches of PubMed and PsychInfo to identify publications resulting from tobacco industry–funded studies.

Results

Health Effects of Smoking in Individuals With Schizophrenia

Earliest evidence of tobacco industry interest in individuals with schizophrenia dates to the mid-1950s with curiosity about apparent low levels of cancer despite high rates of smoking in this patient group.14 The tobacco industry catalogued reports of low cancer rates in schizophrenics15–18 and questioned whether it would be “practical and sensible to … attempt to quantify these relationships.”19 The reports of cancer in schizophrenia were often based on proportionate mortality, calculated as the number of deaths due to cancer divided by total deaths from all causes, which was later criticized as flawed because of the higher total death rate among patients with schizophrenia due to the increased incidence of syphilis and tuberculosis.20 Further, the reports did not account for the possibility that the institutionalized psychiatric settings had failed to detect cancer in these patients.21–23 Nevertheless, the belief that chronic schizophrenics were somehow biologically resistant to cancer prevailed at least until the late 1980s.24

Research funded in the 1960s–1970s by CTR, Philip Morris (PM), and American Brands proposed that persons who denied or repressed grief were more likely to develop cancer than those who expressed emotion.25–27 This research was used to explain why smokers with schizophrenia had low rates of lung cancer—“long-term schizophrenics, outwardly calm … have no capacity for the repression of significant emotional events and no need to contain emotional conflict.”28 The tobacco industry's research on psychosomatic causes of cancer ultimately came under scrutiny for its “scientific integrity,”29–31 and they grew concerned of criticism that they were “financing and giving publicity to an immense smoke-screen.”32

Two proposals were submitted to CTR, in 1964 and 1997, to examine evidence of elevated rates of cancer and lung disease among patients with schizophrenia and the potential relationship to smoking.33,34 Both proposals were denied funding.35,36 One was “denied in principle but referred to the study group on the psycho-physiological aspects of smoking,”37 “for working over.”38 CTR questioned “whether some other kind of use could profitably be made of his data collection methods.”39 An internal letter at CTR read, “What we need to know is whether he has been in the habit of getting worthwhile results that can be depended on.”40 The investigator was unknown to CTR, so it was not known whether he had a track record of producing results that supported the tobacco industry's interests. Ultimately, the work was not funded.35

Recently, government-funded, well-controlled, epidemiologic studies have demonstrated an increased risk of lung cancer among patients with schizophrenia relative to age-matched controls, with the increases attributed to smoking, and no support for the hypothesis of a genetic protection against cancer in families with schizophrenia.41,42 Individuals with schizophrenia also are at elevated risk for the development of tobacco-related cardiovascular disease43 and respiratory disorders.44

Tobacco Industry–Sponsored Research on the “Self-Medication” Hypothesis

The tobacco industry monitored the scientific literature45,46 and funded internal and external research on the “self-medication hypothesis,” which posited that patients with schizophrenia needed to smoke to manage their psychiatric symptoms. Twenty-eight proposals relating to schizophrenia were identified in the tobacco industry documents, of which 7 were ultimately funded; all 7 sought to expose the beneficial self-medicating effects of nicotine and smoking for schizophrenics. The tobacco industry also conducted internal research on the use of nicotine and its analogues for schizophrenia.

Funded External Research

The funded researchers had long histories of tobacco industry support. Five of the 7 funded proposals were submitted by foreign investigators. The tobacco industry was known to fund foreign researchers for studies considered too sensitive to conduct in the United States in an effort to prevent discovery of study information through litigation.47 The studies are described below. Notably, the results of many of the funded studies were not published in the scientific literature. (An example is how INBIFO in Germany [Institut Fur Biologische Forschung or Institute for Biological Research] was set up to hide PM funding for research and protect it. Research showing greater toxicity of sidestream rather than mainstream smoke was not published.48)

In 1982, a Canadian researcher submitted a proposal to the Canadian Tobacco Manufacturer's Council (CTMC) to study “Tobacco Smoking as a Coping Mechanism in Psychiatric Patients” with particular attention to “possible tobacco-induced normalization of arousal deficits in … schizophrenics.”49 The investigator emphasized that his proposed studies “promise to bear fruitful findings. It is particularly interesting that the psychiatrists, who are medical professionals, are very aware of the role of tobacco use in patients and are very interested in these studies. If tobacco can be shown to be an efficient form of ‘self-medication’ for these patients then this would be [a] significant bonus for the tobacco industry.”50 The $84 281 budget request indicated the psychiatric patient subjects were to be paid with money or cigarettes.50 Correspondence within RJ Reynolds (RJR) Research and Development noted that the investigator “has been sponsored by CTMC for some years … his own salary was paid by us—so he was totally dependent on CTMC funding … once again, he seems to be looking at this from our point of view. Apart from his project with children, all previous requests have been approved by the CTMC in general and by RJR in particular.”51 It was a common practice for the tobacco industry's funded research to bypass scientific peer review and instead be funded on the basis of the potential to protect and promote the interests of the companies.52,53 The investigator was funded, though our search of the literature was unable to identify publications arising from this particular study.

In 1987, a US investigator was funded for 3 years by CTR for a study of nicotinic receptors in normal and disease states including schizophrenia.54 The study raised concern among the reviewers who suggested that animal studies be initiated first, warning, “Studies in man, these studies included, can be risky; and risks to human subjects should be avoided whenever possible.”55 Despite the reviewers’ concerns that the study be conducted in animals before humans due to the potential risks to human subjects, the study was approved as initially proposed with a budget of $416 551. The second year report listed 8 publications with 3 acknowledging CTR funding.56 Our literature search, however, did not identify publications from this group concerning nicotinic receptors in schizophrenia.

The tobacco industry funded research to examine latent inhibition and prepulse inhibition (PPI), a measure of attention and sensory gating, in patients with schizophrenia. Funded by CTR for 2 proposals in 1994 and 1997, UK investigators reported that nicotine enhanced PPI in both healthy and schizophrenia groups.57–59 Tobacco industry funding was acknowledged in some,59 but not all, articles appearing to result from these studies.60 Funded by PM in 1994, an investigator in New Zealand examined whether nicotine improves neural inhibition in smoking and nonsmoking schizotypes (defined by the investigator as the trait underlying schizophrenia).61 He received $250 000 plus an additional $3000 was budgeted for study completion. Study findings were discussed with colleagues and reanalyzed but apparently never published.62

In 1994, investigators in Sweden submitted a proposal to CTR with the goals “to facilitate and guide the development of improved pharmacological treatments, including nonaddictive drugs, to assist in smoking cessation programs … to develop more rational pharmacotherapies for mentally ill patients in order to facilitate a smoke-free environment for physicians and other staff members in psychiatric hospitals.”63 The budget request was $336 123. The investigator had been supported by CTR since the 1980s with prior reviews noting, “ … it is clear that there is a strong dependence on our support.”64 The 1994 proposal was funded. The 1997 progress report, however, suggested a primary focus on the self-medication hypothesis with no mention of efforts to develop tobacco treatments for this patient population. Reported findings were “The data strongly support our initial hypothesis that nicotine, indeed, provides a form of self-medication in schizophrenia, especially against so-called negative symptoms.”65 The progress report listed 17 resulting publications, 5 of which did not acknowledge CTR funding66–70; none of the 17 publications concerned tobacco treatment in schizophrenia.

In 1998, US investigators were funded by PM to characterize the pharmacological properties of nicotine using functional magnetic resonance imaging.71 The project was positioned with “direct relevance to ongoing research in schizophrenia …. For these individuals, nicotine may substantially reverse certain cognitive deficits, and we aim to determine the brain mechanisms underlying this potential therapeutic benefit.” One of the reviewers, a research scientist at PM, discouraged funding, stating “I simply do not see this as one of our key business interests. Again, since we extensively fund such research I defer to those who successfully justify such expenditures.”72The research was viewed by PM to be of “great interest to the public health community,”73 and the proposal was funded at $178 930 per year for 3 years.74,75 The researchers presented their funded work at a scientific meeting.76 Further search in PubMed failed to identify any other publications specific to the project.

Unfunded External Research

The twenty-one unfunded proposals were submitted between 1966 and 1999, to TIRC/CTR, RJR, PM, and Brown and Williamson. Proposal objectives included study of tobacco-related cancers among patients with schizophrenia (detailed above)33,34; smoking prevalence among schizophrenics77; social uses of tobacco among psychiatric patients78,79; nicotine's effects on neuroleptic blood levels80; nicotine withdrawal effects in schizophrenia81; vitamin depletion in schizophrenia due to tobacco use82; animal models of nicotine's effects in schizophrenia83; genes related to aggression in schizophrenia84; nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in schizophrenia and neurotransmitter differentiation85–89; the dopamine D4 receptor's role in the pathophysiology and treatment of schizophrenia90,91; and use of nicotine and nicotine metabolites for treating schizophrenia.92–95 One of the review letters emphasized that the decision to deny funding “does not reflect in any way upon scientific merit96;” 6 other researchers were encouraged to seek funds elsewhere.36,97–101 Only 2 of the 21 unfunded proposals were submitted by foreign investigators; both aimed to examine the role of nicotine and nicotinic receptors in the treatment of schizophrenia.

Internal Research

Tobacco industry internal research on schizophrenia focused on the use of nicotine and nicotine analogs as pharmaceutical agents. By 1989, RJR owned the rights to over 130 nicotine analogs with the goal “to understand how nicotine interacts with the central nervous system” and to apply this knowledge to “evaluation of various aspects of new products.”102 RJR's initial interests included a specific question into “nicotinic effects in schizophrenia.”103 Goals were to “positively impact [the] research community's attitude about nicotine,” “improve [the] public perception of nicotine through marketing of products,” and “change [the] perception of nicotine in [the] medical community.”103 Additional benefits included “evaluation of various aspects of new products,” having “a vehicle for RJRT scientists to contribute to the literature in this area,” and to “gain credibility for RJR and gain access to leading scientists, active in nicotine research, throughout the world.”102

In 1997, RJR “formed a wholly-owned subsidiary known as Targacept, Inc.,” named for “targeted receptors.”104 Targacept was developed “to rapidly commercialize RJRT's nicotine pharmaceutical technologies,”105 and, it has been suggested, to circumvent nicotine regulation.106 One goal was development of an add-on drug to help with concentration and attentional deficits in schizophrenia, with an estimated target market of $1.5–$6 billion.105,107 In presentations for venture capital, Targacept emphasized the knowledge of their scientific advisory board including leading schizophrenia researchers.105,108 In industry documents and the popular press, RJR explicitly stated that the developed drugs were not to be used for smoking cessation,109,110 rationalizing that the tobacco treatment pharmaceutical market was already saturated. Yet at the time (January 1999), there were only 4 drugs for treating tobacco dependence compared with 15 medications for treating schizophrenia.111

Promoting Smoking in Psychiatric Patients

The tobacco industry promoted smoking in psychiatric patients using both direct (ie, distribution, advertising, scientific publications, and meetings) and indirect (ie, policy effort) strategies. Figure 1 shows an advertisement for Merit cigarettes with the headline reading, “Schizophrenic.”112 It is not clear whether the marketing campaign targeted individuals with schizophrenia or was aimed at the general public, seeking to capitalize on the common misunderstanding of schizophrenia as reflecting a split personality: here, lower tar and big taste.

Fig. 1.

A 1986 Advertisement for Philip Morris’ Merit Cigarettes Suggests Evidence of Direct Marketing of Tobacco Products to Individuals with Schizophrenia.113 The ad shows a double image of a pack of Merit cigarettes and reads, “Schizophrenic … For New Merit, having two sides is just normal behavior.”

The tobacco industry disseminated its position through the scientific literature, popular press, and policy settings. A book published by a former RJR researcher included discussion of smoking to self-medicate psychopathology.113 A review article in Chemistry and Industry titled “Nicotine: Helping those who help themselves?”114 suggested that “nicotine may have beneficial effects that are ‘therapeutic’ rather than addictive.” The author concluded that “many people who use tobacco … do so because of some potential therapeutic benefit they receive, such as to relieve depression, schizophrenia or pain,” and emphasized that “we first need to pull away from this concept of demonism and treat nicotine and its analogues like any other drug.” The author encouraged the use of nicotine even among nonsmokers with schizophrenia. Tobacco industry documents indicate the author received funding from CTR and PM from at least 1977–1994 and contributed to papers conceived by PM.115–119 Another CTR, PM, and RJR-funded researcher120–123 published at least 11 review articles and an edited textbook concerning the merits of nicotine and nicotine analogues in the treatment of schizophrenia.124–127 The same researcher held scientific conferences sponsored by RJR128 and PM129,130 from 1995 to 2006 with presentations on the therapeutic indications and targeting of nicotinic treatments for schizophrenia.131–133 Though not mentioned in meeting announcements,134 tobacco industry sponsorship was acknowledged in the programming materials.135,136 Participants included leading academic nicotine researchers and tobacco industry scientists. The meeting proceedings were published127,137 without recognition of tobacco industry funding.127 Previous research has revealed that publications resulting from tobacco industry–sponsored conference proceedings are more likely to present unbalanced data and be authored by tobacco industry–affiliated individuals than nontobacco industry–sponsored publications.138 On behalf of the American Tobacco Company, a psychiatrist with research expertise in the genetics of schizophrenia provided expert commentary to the Food and Drug Administration Drug Abuse Advisory Committee arguing that nicotine is nonaddictive.139

The most direct approach to promoting tobacco consumption was through provision of cigarettes to psychiatric institutions. In 1975, a letter from the Associate General Counsel for PM to the President of the Tobacco Institute indicated that mental health facilities were ordering cigarettes on a tax-free basis specifying the cigarettes were “to be used for patient treatment.”140 Other letters came from medical staff at psychiatric institutions requesting cigarette donations for their patients. In 1980, a letter from the medical director at the National Institute of Mental Health's St Elizabeth's Hospital requested a donation from RJR of 5000 cigarettes per week for their psychiatric inpatients, stating the hospital was no longer able to purchase cigarettes for patients because of the change in the Department of Health and Human Services’ (DHHS) regulations.141 RJR staff determined who was responsible for the policies and encouraged the medical director to contact the DHHS Secretary to cancel the regulations.142 In 1992, a case manager in Oregon wrote to RJR requesting “outdated or damaged cigarettes” in donation to the county mental health center's prevocational program for use as payment for patients’ work activities.143 In 1996, a social worker from a mental health center in Texas wrote to RJR for cigarette donations stating “with all the publicity of smoking harming so many people, this would be a positive aspect of smoking. [The] lung cancer rate in schizophrenics appears to be ‘lower’ than the general population rate of cancer.”144 A tax-exempt letter was enclosed. In 2000, a staff psychiatrist at the Hawaii State Hospital wrote to RJR requesting cigarettes for a patient stating, “providing a cigarette is generally much more effective at decreasing agitation than most medications I can provide.”145 It is unclear whether these requests were granted.

The tobacco industry worked indirectly to promote smoking in psychiatric patients via financial contributions and ties to patient advocacy groups. At a cost of $1000 per table, Brown and Williamson accepted an invitation to attend a black tie affair for the Schizophrenia Foundation, Kentucky with the promise that they would be provided “any guest you may wish among our public officials or Legislators.”146 A 1987 fax from the public relations firm Hill & Knowlton to RJR included contact information for the president of the American Schizophrenia Association. A handwritten note indicated, “good list for press conference invites.”147 The tobacco industry also hired legal counsel to monitor research on hospital smoking restrictions and to fight policy efforts aimed at restricting smoking among psychiatric staff and patients148,149; they contacted a teamster official to offer assistance with grievance procedures against smoking bans at a state mental hospital150; and coordinated testimony to allow smoking in psychiatric hospitals in Maine.151,152

In 1990, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) mandated that all hospitals in the United States implement smoke-free environments by December 31, 1993. The JCAHO decision made hospitals the first worksites to attempt an industry-wide smoking ban. The proposal included all hospital-based care. The tobacco industry evaluated the legislation and considered one of its usual tactics—congressional lobbying. However, a 1991 memo from the RJR Public Issues Department to the RJR Vice President for Federal Government Affairs concluded “there is little connection between JCAHO and Congress by which we can request assistance and expect JCAHO to pay closer attention than it would to its members.”153 Instead, the memo suggested that “of the hospitals that have contacted us, we should consider having them write JCAHO … to challenge the reasonableness prior to the standard being implemented. In essence, the first shot to JCAHO should come from some of its members.”153

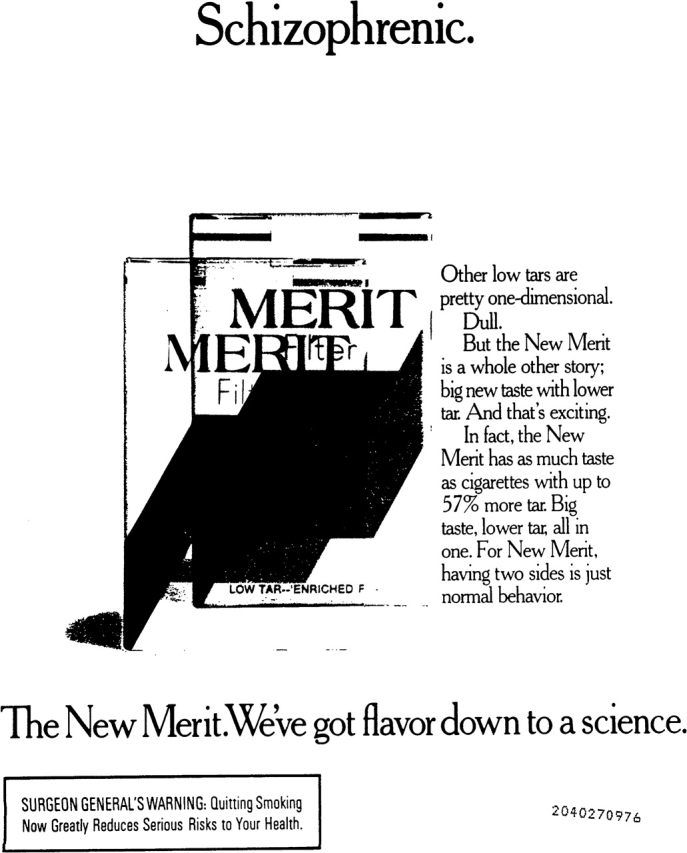

A strong response to the JCAHO mandate came from the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (AMI, now NAMI) and Friends and Advocates of the Mentally Ill (FAMI). These patient advocacy groups emphasized the need for mentally ill patients to smoke, based on the self-medication hypothesis discussed above. In a 1994 article in Psychiatric News, a publication of the American Psychiatric Association, the executive director of FAMI stated, “The issue is important to us because it is important in the lives of people with mental illness.”154 A 1995 AMI/FAMI policy paper, approved by the Board of Directors, asserted “Psychiatric patients should have access to discrete smoking areas,” stating “nicotine may work to reduce their psychotic symptoms” and “it is inhumane to rob these patients of their autonomy and dignity by infringing on one of the few remaining freedoms historically allowed patients.”155 AMI/FAMI launched a “Campaign to bring discrete smoking areas to city hospital.” Figure 2 is an example of campaign materials found in the tobacco industry documents.156

Fig. 2.

An Example of Campaign Materials from the Alliance for the Mentally Ill (AMI) and Friends and Advocates of the Mentally Ill (FAMI) in Opposition to the Mandate to Make all Hospitals, Including Psychiatric Units, Smoke Free.154

PM monitored the popular press reporting on AMI/FAMI's opposition to the hospital smoking bans. A vocal leader in the effort was a member of the AMI/FAMI board of directors who, according to a 1994 Wall Street Journal article, “organized a tidal wave of letters and petitions to the Joint Commission.”157 The article reported that her “crusade is backed by the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill. The group says it hasn't had any contact with the tobacco industry.” The board member's business card, however, was found among the PM documents with this handwritten note and her signature on the back: “Philip Morris: FAMI is fighting the city, HHC and Bellevue Hospital bureaucracy. The patients in the psychiatric inpatient units, emergency unit and admissions units need a discrete smoking area and not be forced to go cold turkey.”158,159 A 1995 PM “Hearing Report/Bill Signing Report” summarized a public event held by the New York City mayor to discuss the proposed environmental tobacco smoke restriction bill. The report noted that the board member “of the Friends of the Mentally Ill spoke in opposition to the bill.”160 Another PM document lists FAMI as a witness for the Smoke-Free Air Act hearing.161

JCAHO ultimately “yielded to massive pressure from mental patients and their families, relaxing a policy that called on hospitals to ban smoking.”162 The acting director of the commission's Department of Interpretation explained that “The mental health advocacy groups came out in opposition to our original policy and we sat down with them and, as a result of those discussions, revised the standard.”162 An exception was made to allow continued smoking in psychiatric inpatient and substance use facilities for long-term patients.

Despite JCAHO's decision and state legislation to permit smoking in inpatient psychiatric facilities, some hospitals voluntarily implemented smoking bans, and reports in the literature suggest little difficulty in converting to a smoke-free environment.163 Even among psychiatric inpatient units with smoke-free policies, however, tobacco cessation treatment is rarely provided,164 and most patients return to smoking immediately upon discharge.165

Discussion

This analysis of internal tobacco industry documents shows that the industry has attempted to promote and maintain tobacco use among individuals with schizophrenia. The industry has monitored or directly funded research supporting the idea that individuals with schizophrenia are less susceptible to the harms of tobacco and that they need tobacco as self-medication. Through its funding mechanisms, the tobacco industry has influenced the types of questions asked about tobacco use among patients with schizophrenia. Industry executives reviewed grants based on whether they could trust the scientists or knew the scientists had previously produced research favorable to the industry. The industry did not fund studies that might expose tobacco as harmful. Lastly, our finding that the results of some industry-funded studies were not published in the scientific literature raises the question of whether findings unfavorable to the industry were suppressed.47,166 Investigations into tobacco industry documents have demonstrated similar tactics of driving the research agenda through funding and publication to influence research and policy on the harms of secondhand smoke.52,167

More than 40 years after publication of the 1964 Surgeon General's Report on lung cancer and tobacco,168 it is now recognized that tobacco use places patients with schizophrenia at increased risk for lung cancer, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory disorders.42–44 The tobacco industry's efforts to promote research showing that schizophrenic patients were less susceptible to lung cancer may have contributed to this 4-decade delay.

The mentally ill are one of the largest remaining groups of smokers and yet astoundingly little research has been published on treatment of their tobacco dependence. A search of PubMed on February 12, 2005 using the keywords “schizophrenia” and “nicotine, tobacco or smoking” yielded 534 publications. Only 12, however, evaluated cessation treatment for this patient group. Evidence in the documents suggests the tobacco industry restructured proposal objectives away from smoking cessation and toward the self-medication hypothesis.

The tobacco industry has promoted smoking among patients with schizophrenia through research funding and dissemination; has used the self-medication hypothesis to garner exceptions to permit continued smoking among hospitalized psychiatric patients; and has sought credibility through development of nicotine analog medications for the mentally ill. Though the current article does not attempt to systematically review the literature on the cognitive effects of nicotine and nicotine analogs in schizophrenia, it is worth mentioning findings from a few studies. In summarizing the literature, investigators recently have concluded that nicotine's neurocognitive effects in schizophrenia are comparable to effects seen in healthy adults, are greatly limited by tachyphylaxis, and are not clinically significant.169 A recent study of nicotine's neurocognitive effects in schizophrenia reported small increases in attention among nonsmokers, decreased attention among nicotine-abstinent smokers, and no effects on learning and memory, language, or visuospatial/constructional abilities.170 Among studies that have reported cognitive enhancements of nicotine in smokers with schizophrenia, many have used nicotine-deprived heavy smokers; have reported effects in some outcomes, but not others; and, again, have shown effects comparable to nonpsychiatric samples. For example, an investigation of the nicotine nasal spray with chronic smokers with schizophrenia who were deprived of nicotine overnight (for 10–12 hours) reported small effects on enhanced attention and spatial working memory.171 The study did not assess nicotine withdrawal effects, a weakness they acknowledged in their design. A study comparing smokers with and without schizophrenia who were deprived of nicotine and then given active or placebo nicotine patch, reported 1 of 8 diagnosis-by-nicotine interactions as significant, though had the study controlled for multiple comparisons, the finding would have been nonsignificant.172 Additionally, the analyses did not control for differences in baseline plasma cotinine levels between the 2 groups, and the authors acknowledged that the effect of antipsychotic medication, rather than diagnosis, could not be excluded. Of the 13 patients with schizophrenia, all 13 were taking antipsychotics with metabolism known to be induced by smoking (ie, olazapine, clozapine, and haloperidol). In a third study comparing the effects of transdermal nicotine on cognition in nonsmokers with schizophrenia and nonpsychiatric controls, nicotine modestly improved attentional performance in both groups, with a greater improvement among schizophrenia patients on errors of commission and performance on a Card Stroop task.173 The study did not control for group differences in IQ, age, education, or history of smoking (60% among patients and 25% among controls). Studies have not examined the implications of giving nicotine to never or former smokers on future smoking behavior.

Moving beyond nicotine, the National Institute of Mental Health Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia initiative has identified the alpha 7 nicotinic receptor as one of the top rated potential therapeutic targets, and research in this area is likely to expand.174 A recent proof-of-concept trial of an α7 nicotinic agonist in schizophrenia reported nonsignificant effects on performance when the effect of repeated testing was controlled.169 Strongest effects were seen at the lowest dose suggesting possible tachyphylaxis. In August 2007, Targacept announced its Phase IIb clinical trial of an α7 nicotinic agonist for addressing cognitive deficits in schizophrenia.175The President and Chief Executive Officer of Targacept explained, “Research has shown that almost 90% of schizophrenics smoke. One explanation for this high rate of smoking is that schizophrenic patients may be self-medicating with nicotine in order to address the cognitive impairment associated with the disease and thus function better.” Smoking cessation is now listed on the company’s Web site as a yet to-be-determined target for product development.

Effective tobacco cessation treatments are needed, and if the tobacco industry, and now Targacept, truly wanted to help mentally ill smokers, they would be leveraging their knowledge of nicotine drugs to reduce tobacco use in this vulnerable group. The National Institutes of Health and the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program are funding investigations in this area, and initial findings suggest good reason for optimism for helping individuals with schizophrenia quit smoking.176–178 Importantly, a 3-day investigation of placebo versus baseline or active patch did not find acute exacerbation of clinical symptoms, challenging the self-medication hypothesis.179

The tobacco industry documents were obtained through litigation and thus provide an incomplete picture of the tobacco industry's activities in this area. The mentally ill are a disenfranchised group and are less likely to pursue litigation, so documents specific to the schizophrenic population may be missing. Furthermore, advocacy groups for the mentally ill have focused on maintaining their tobacco use rather than treating this deadly addiction. While opponents of secondhand smoke exposure have vigorously fought for antismoking legislation, psychiatric and substance abuse treatment centers have been exempted. The documents we found were largely limited to the year 2000, and thus current activity is unknown. Given these limitations, published research literature and news material were incorporated to provide a relevant historical, research, and clinical context for the obtained documents. We conducted extensive searches in PubMed and PsychInfo to identify publications resulting from the tobacco industry–funded studies, but it is possible that the work was published in journals not indexed by these databases including nonpeer reviewed journals and texts.

Beliefs that individuals with schizophrenia need to smoke as a form of self-medication, that quitting smoking will worsen their psychiatric symptoms, and that they cannot and do not want to quit their tobacco use have been some of the biggest barriers to tobacco treatment for schizophrenic patients.7–10 The tobacco industry has contributed to the promulgation of these beliefs. The problem of tobacco use among schizophrenic individuals will not go away unless effective treatments for smoking cessation are developed and delivered to smokers with mental illness. Might it be that the mentally ill are the largest remaining group of smokers, not because they need to smoke but rather because they are among the last to be treated? Given the tobacco industry's track record on research related to tobacco and schizophrenia, it is unlikely that the industry will make a valid effort to develop cessation treatments for this population.

Funding

State of California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (#13KT-0152); the National Institute on Drug Abuse (#K23 DA018691, #K05 DA016752, and #P50 DA09253).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Desiree Leek for her editorial assistance. Disclosures: Drs Prochaska, Hall, and Bero report no competing interests. Paper presented at the 2007 Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association in San Francisco, CA.

References

- 1.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, Stinson FS, Dawson DA. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1107–1115. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284:2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Federal Trade Commission. Federal Trade Commission Cigarette Report for 2003. Washington, DC: Federal Trade Commission; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Womach J. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes JR. Possible effects of smoke-free inpatient units on psychiatric diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:109–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poirier MF, Canceil O, Bayle F, et al. Prevalence of smoking in psychiatric patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26:529–537. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levin ED, Wilson W, Rose JE, McEvoy J. Nicotine-haloperidol interactions and cognitive performance in schizophrenics. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;15:429–436. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(96)00018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barak Y, Achiron A, Mandel M, Mirecki I, Aizenberg D. Reduced cancer incidence among patients with schizophrenia. Cancer. 2005;104:2817–2821. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalack GW, Meador-Woodruff JH. Smoking, smoking withdrawal and schizophrenia: case reports and a review of the literature. Schizophr Res. 1996;22:133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(96)80441-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandyk R, Kay SR. Tobacco addiction as a marker of age at onset of schizophrenia. Int J Neurosci. 1991;57:259–262. doi: 10.3109/00207459109150699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bero L. Implications of the tobacco industry documents for public health and policy. Annu Rev Public Health. 2003;24:267–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.100901.140813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bero LA. Tobacco industry manipulation of research. Public Health Rep. 2005;120:200–208. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carter SM. Tobacco document research reporting. Tob Control. 2005;14:368–376. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.010132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis NDC. Research in Dementia Praecox. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Modrzewska K, Book JA. Schizophrenia and malignant neoplasms in a north Swedish population. Lancet. 1979;1:275–276. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)90806-7. Bates No. 10412696B/2697. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yjp4aa00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gopalaswamy AK, Morgan R. Smoking in chronic schizophrenia correspondence. Br J Psychiatry. 1986;149:523. Bates No. 508153978. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ncj13a00. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jancar J. Cancer in the long-stay hospitals. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:550–551. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.5.550a. Bates No. 2025876464/6465. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ams24e00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rice D. No lung cancer in schizophrenics? Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:128. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.1.128b. Bates No. 501729733. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rog23a00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lincoln JE. Schizophrenics. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perrin GM, Pierce IR. Psychosomatic aspects of cancer: a review. Psychosom Med. 1959;21:397–421. doi: 10.1097/00006842-195909000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breen MJ. The incidence of lung cancer among schizophrenic males versus nonschizophrenic males. A dissertation presented to the graduate faculty of the School of Education United States International University. 1981 Bates No. 504848496/8514. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cuq18c00. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fox BH, Howell MA. Cancer risk among psychiatric patients: a hypothesis. Int J Epidemiol. 1974;3:207–208. doi: 10.1093/ije/3.3.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsuang MT, Perkins K, Simpson JC. Physical diseases in schizophrenia and affective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1983;44:42–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris AE. Physical disease and schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1988;14:85–96. doi: 10.1093/schbul/14.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bahnson CB. Letter to Dr. Hockett Requesting Continued Research Funding on Dr. Kissen's Unit in Glasgow. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hetsko C. Memo to William W. Shinn Confirming American Brands’ $8,000 Contribution to Dr. Claus Bahnson's Project. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holtzman A. Special Project—Dr. Claus Bahnson. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parfitt DN. Lung cancer and schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1981;138:179–180. doi: 10.1192/bjp.138.2.179. Bates No. 1003050027/0028. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/anp97e00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colby FG. Report on trip to Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcus MG. The shaky link between cancer and character. Psychol Today. 1976;10 52,54,59,85. Bates No. 2023065144/5147. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qnk48e00. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wakeham H. Letter about Doubts of Dr. Bahnson's Research Involvement. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Todd GF. Private Letter No. 12 to Mr. Addison Yeaman. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaudet FJ, Owen HE. Application for Research Grant Exploring Cancer Rates and Cigarette Use among Different Types of Schizophrenia. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavietes MH. Cigarette Smoking in Schizophrenic Patients. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hockett RC. Research Application from Frederick J. Gaudet. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McAllister HC. Decline of Research Support for Dr. Marc Lavietes. [Google Scholar]

- 37.CTR Collection. Confidential Report Scientific Advisory Board Meeting New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 38.CTR Collection. New proposals. 1964. Bates No. HK2039136/9136. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gvo2aa00. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hockett RC. Letter to Dr. Taguiri Concerning Research Proposals, Including Smoking and High Academic Achievement. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson EB. Letter to Dr. Hockett. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dalton SO, Laursen TM, Mellemkjaer L, Johansen C, Mortensen PB. Risk for cancer in parents of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:903–908. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.5.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lichtermann D, Ekelund J, Pukkala E, Tanskanen A, Lonnqvist J. Incidence of cancer among persons with schizophrenia and their relatives. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:573–578. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goff DC, Sullivan LM, McEvoy JP, et al. A comparison of ten-year cardiac risk estimates in schizophrenia patients from the CATIE study and matched controls. Schizophr Res. 2005;80:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Himelhoch S, Lehman A, Kreyenbuhl J, Daumit G, Brown C, Dixon L. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among those with serious mental illness. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2317–2319. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gullotta . WSA Categorization form Smoking Behavior: Clinical Depression and Schizophrenia. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Southwick MA. Literature Search: Schizophrenia and Nicotine. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Glantz SA, Slade J, Bero LA, Hanauer P, Barnes DE. The Cigarette Papers. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deithelm PA, Rielle J-C, McKee M. The whole truth and nothing but the truth? The research that Philip Morris did not want you to see. Lancet. 2005;366:86–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66474-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knott V. Tobacco Smoking as a Coping Mechanism in Psychiatric Patients: Psychological, Behavioral and Physiological Investigations Phase I. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Knott V. Research Proposal. Tobacco Smoking as a Coping Mechanism in Psychiatric Patients: Psychological, Behavioral and Physiological Investigations. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crawford DA. Letter to Dr. R. Suber in the Consideration Dr. Knott's Research Proposal. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barnes DE, Bero LA. Industry-Funded Research and Conflict of Interest: An Analysis of Research Sponsored by the Tobacco Industry through the Center for Indoor Air Research. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1996;21:515–542. doi: 10.1215/03616878-21-3-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bero L, Barnes DE, Hanauer P, Slade J, Glantz SA. Lawyer control of the tobacco industry's external research program. The Brown and Williamson documents. JAMA. 1995;274:241–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amey MB, Wong DF. Application for Research Grant: In Vivo Studies of Nicotinic Cholinergic Receptors in the Human Brain. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith C. Comments on Dr. Wang's Grant Proposal: In Vivo Studies of Nicotinic Cholinergic Receptors in the Human Brain. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stone D. Second Renewal Application: In Vivo Studies of Nicotinic Cholinergic Receptors in the Human Brain. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gray JA. CTR Progress Report Mediation by Catecholamine Systems of Effects of Nicotine on Behaviours. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gray JA. Project Details: Nicotine Neuroprotection and Animal Models of Neurodegenerative Cognitive Dysfunction. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gray JA, Joseph MH, Hemsley DR, et al. The role of mesolimbic dopaminergic and retrohippocampal afferents to the nucleus accumbens in latent inhibition: implications for schizophrenia. Behav Brain Res. 1995;71:19–31. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(95)00154-9. Bates No. 50379603/9615. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/iek98d00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Postma P, Gray JA, Sharma T, et al. A behavioural and functional neuroimaging investigation into the effects of nicotine on sensorimotor gating in healthy subjects and persons with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:589–599. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mangan GL. Application to Philip Morris USA for Research Funding. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mangan GL. Facsimile Transmission Header Sheet Completion of Philip Morris Research Programme at the University of Auckland. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hedqvist P, Svensson TH. Research Grant Application. Nicotine Dependence in Psychiatric Illness: an Experimental Study. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Glenn JF. Brief Site Visit Report. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Svensson TH. CTR Progress Report (for Competing Renewal Application) Nicotinic Dependence in Psychiatric Illness: an Experimental Study. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Svensson TH, Mathe JM, Andersson JL, Nomikos GG, Hildebrand BE, Marcus M. Mode of action of atypical neuroleptics in relation to the phencyclidine model of schizophrenia: role of 5-HT2 receptor and alpha1-adrenoreceptor antagonism. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;15(suppl 1):11S, 18S. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199502001-00003. Bates No. 50733819/3826. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ixi46d00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nisell M, Nomikos GG, Svensson TH. Systemic nicotine-induced dopamine release in the rat nucleus accumbens is regulated by nicotinic receptors in the ventral tegmental area. Synapse. 1994;16:36–44. doi: 10.1002/syn.890160105. Bates No. 50708314/8314. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/luf46d00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nisell M, Nomikos GG, Svensson TH. Infusion of nicotine in the ventral tegmental area or the nucleus accumbens of the rat differentially affects accumbal dopamine release. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1994;75:348–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1994.tb00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nisell M, Nomikos GG, Svensson TH. Nicotine dependence, midbrain dopamine systems and psychiatric disorders. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1995;76:157–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1995.tb00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grillner P, Bonci A, Svensson TH, Bernardi G, Mercuri NB. Presynaptic muscarinic (M3) receptors reduce excitatory transmission in dopamine neurons of the rat mesencephalon. Neuroscience. 1999;91:557–565. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00619-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Furlong P, Tanabe J. Project Proposal Effects of Nicotine on Brain Activation. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kassman A. SRRC Proposals: Tanabe, Bilder & Lajtha/Friedman. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gullotta FP. Bilder/Lajtha Grant. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Philip Morris Collection. Approval of Grant Proposal Entitled: “Effects of Nicotine on Brain Activation”. [Google Scholar]

- 75.McAlpin L. Philip Morris Voucher. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bidler RM, Lajtha A, Thomas T. Nicotine Effects on Cognition: Meta-analysis and Implications for Neuroimaging. [Google Scholar]

- 77.de Leon J. Epidemiology of Tobacco Use in Psychiatric Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Esser AH, Lee MG. Application for Research Grant: The Social Use of Tobacco. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hoyt WT. Research Funding Decline for Dr. Aristide H. Esser. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smith RC. Effects of Smoking on Blood Levels of Neuroleptic and Antidepressant Drugs. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Goff DC. Nicotine in Schizophrenia. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Barclay GL, Devlin RJ, Grant FW, McDonald RD, Ozerengin MF, Voorhees W. Application for Research Grant: Vitamin “C” Depletion in Tobacco Smokers. Influence on Psychopathology and Therapeutic Drug Requirements in a Mental Hospital Setting. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Deutsch SI. Effect of Nicotine in an Animal Model of Schizophrenia. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lachman H. Molecular Genetic Analysis of Aggression in Rats. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Javaid JI, Longone P, Pesold C. Functional Characterization of Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor (NACHR) Subtypes. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liu Y, Nisbett N. Research Grant Application: Physiological Role(s) of SNAP-25. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nawa H. Neurotransmitter Differentiation of Neural Precursors in the Brain. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Paskevich PA, Tarazi FI. Research Grant Application Localization and Regulation of Neurotensin Receptor and Gene Expression. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Regehr WG. The Control of Synaptic Transmission in the Mammalian Brain by Presynaptic Waveform. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Arnason B. Drug abuse and the Dopamine Transporters. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tarazi FI. Pharmacological and Functional Characterization of Dopamine D4 Receptor. 1996 Bates No. 50549783/9786. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cok36d00. [Google Scholar]

- 92.RJ Reynolds Collection. Review of a Proposal Submitted by Sheila Carter, M.D. 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Callery PS. Metabolites of Tobacco Constituents Related to GABA as Potential Therapeutic Entities. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ellis C. WWSA Project Justification Role of Neuronal Nicotinic Receptors in Brain Function. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hayes AW. Letter to Dr. D.A. Crawford Concerning Review of Research Grants. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hockett RC. Research Proposal Decline for Robert C. Smith. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Glenn JF. Rejection for Dr. Neve's Research Proposal: Drug Abuse and the Dopamine Transporter. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Glenn JF. Decline of Dr. Yuechueng Liu's Research Proposal: Physiological Role(s) of SNAP-25. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Glenn JF. Rejection of Dr. F. Tarazi's Research Proposal: Localization and Regulation of Neurotensin Receptor and Gene Expression. [Google Scholar]

- 100.McAllister HC. Decline of Research Funds for Donald C. Goff. [Google Scholar]

- 101.McAllister HC. Decline of Support for Dr. Wade Regehr's Research Proposal. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lippiello PM, Fluhler EN. Nicotine Receptor Pharmacology. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lillpiello PM, Caldwell WS, DeBethizy JD, Smith CJ, Pritchard WS. Progress Report on the RJRT-Hoechst-Roussel Collaborative Scientific Program. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wellesley MA. Corporate Overview of Pharmaceutical Related Technologies of the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Targacept. Targacept Key Messages. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Vagg R, Chapman S. Nicotine analogues: a review of tobacco industry research interests. Addiction. 2005;100:701–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Targacept. Targacept Pharmaceutical Technologies of the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Targacept. Targacept Leader in Neuronal Nicotinic Receptor-Based pharmaceutical R&D. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hwang S. “R.J. Reynolds Hopes to Spin Nicotine Into Drugs”. Wall St J. 1999 Jun 28:Sect. B1. Bates No. 535070496/0497. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hzp11c00. [Google Scholar]

- 110.RJ Reynolds Collection. Nicotinic Compound Q&A. [Google Scholar]

- 111.US Department of Health & Human Services FDA/Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. A Catalog of FDA Approved Drug Products. 2006 [cited 1/17/2006]. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/ [Google Scholar]

- 112.Philip Morris Collection. Advertisement: schizophrenic [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gilbert DG. Smoking: Individual Differences, Psychopathology, and Emotion. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rosecrans JA. Nicotine: helping those who help themselves? Chem Ind. 1998:525–529. Bates No. 2063591851/1855. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ryp67e00. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tobacco Institute Collection. Active Projects. [Google Scholar]

- 116.American Tobacco Collection [Google Scholar]

- 117.Council for Tobacco Research [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nixon G. Fax [Google Scholar]

- 119.Philip Morris Collection. Pharmacology of Nicotine. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Levin ED. Thank You to Robert F. Gertenbach for $75,000/year Grant Concerning the Behavioral and Neural Mechanisms Underlying Nicotine-Induced Cognitive Facilitation. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Levin ED. Thank You to Dr. Robert F. Gertenbach for $85,000 Grant to Investigate Beneficial Effect Nicotine Has on Memory Function. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Levin ED. Thank You for $43,777 Gift to Support Work on Nicotinic Psychopharmacology at Duke. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Levin ED. Thank You to Dr. McAllister for $92,000 Grant to Investigate Beneficial Effect Nicotine Has on Memory Function. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Levin ED, Karan L, Rosecrans J. Nicotine: an addictive drug with therapeutic potential. Med Chem Res. 1993:509–513. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Levin ED, Rezvani AH. Development of nicotinic drug therapy for cognitive disorders. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;393:141–146. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00885-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Levin ED, Rezvani AH. Nicotinic treatment for cognitive dysfunction. Curr Drug Targets. 2002;1:423–431. doi: 10.2174/1568007023339102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Levin ED. New York, NY: CRC Press. Chapter 11 by Joseph McEvoy Nicotine and Schizophrenia; 2001. Nicotinic receptors in the nervous system; pp. 227–234. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Levin ED. Letter to RJR's Dr. J. Donald DeBethizy Requesting $15,000 for Duke's Nicotine Research Symposium. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Levin ED. Thank You to Dr. Frank Gullotta of Phillip Morris-USA for $10,000 Donation to Duke Nicotine Conference. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Levin ED. Request for Monetary Contribution for Duke Nicotine Conference from Dr. Frank Gullotta of Phillip Morris-USA. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Levin ED. First Annual Duke Nicotine Research Symposium. Neurobehavioral Effects of Nicotine. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Philip Morris Collection. Synopsis of the 5th Annual Duke Nicotine Research Conference. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Rose JE, Levin ED. Duke Nicotine Research Conference. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Brandt L, Brearley E. Future Events: 5th Annual Duke Nicotine Research Conference, Targeting Nicotinic Treatments [Google Scholar]

- 135.Duke University. Third Annual Duke Nicotine Research Conference, Nicotinic Systems: Molecular Heterogenecity And Individual Differences Program. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Lipowicz PJ. 6th Duke Nicotine Research Conference Trip Report. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Lukas RJ, Bencherif M, Eisenhour CM. Regulation by Nicotine of its Own Receptors. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Bero LA, Galbraith A, Rennie D. Sponsored symposia on environmental tobacco smoke. JAMA. 1994;271:612–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Cloninger CR. The State of Texas vs. the American Tobacco Company, et al. Videotaped Oral Deposition of C. Robert Cloninger. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Holtzman A. Memo to Horace Kornegay about Tax-Free Cigarettes for Patient Treatment. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Torrey EF. Cigarette Donation Request for Long-Term Psychiatric Patients. [Google Scholar]

- 142.RJ Reynolds Collection. Letter Declining Request for Cigarette Supply at Saint Elizabeth's Hospital. [Google Scholar]

- 143.Buckingham J. Cigarette Request for Day Treatment Program for Mentally Ill Adults. [Google Scholar]

- 144.Hayworth P. [Google Scholar]

- 145.Robertson ES. Hawaii State Hospital Request to RJ Reynolds for Cigarettes. [Google Scholar]

- 146.Ardery PP. Kentucky's Legislators Thank You Letter. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Reynolds RJ. West Palm Beach/Ft. Lauderdale Fax for Conference Invites. [Google Scholar]

- 148.Shook, Hardy, Bacon . Report on Recent ETS and IAQ Developments. [Google Scholar]

- 149.Shook, Hardy, Bacon . Report on Recent ETS and IAQ Developments. [Google Scholar]

- 150.Lyons J. Support of Region III Public Smoking Issues. [Google Scholar]

- 151.Doyle JR. Memo to Kent Wold Including the Maine Public Health Association Bulletin. [Google Scholar]

- 152.Doyle JR. Letter to Lawrence Tilton about Smoking in Restaurants Bill (L.D. 603) Being Set for Hearing on Wednesday, April 3, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 153.Payne T. Hospital Accreditation. [Google Scholar]

- 154.Mental Illness Advocacy Group Battling Hospital Smoking Ban in New York from Psychiatric News [Google Scholar]

- 155.Alliance for the Mentally Ill, Friends & Advocates of the Mentally Ill. AMI/ FAMI Policy Paper on Nicotine Addiction and Psychiatric Patients. [Google Scholar]

- 156.Alliance for the Mentally Ill, Friends & Advocates of the Mentally Ill. Plea for Freedom to Smoke for Bellevue Hospital Psychiatric Patients. [Google Scholar]

- 157.Miller MW. Wall St J. Mental Patients Fight to Smoke in the Hospital. [Google Scholar]

- 158.Konopka H. Note to Philip Morris. [Google Scholar]

- 159.Konopka H. Hellen Konopka AMI and FAMI Business Card. [Google Scholar]

- 160.Philip Morris Collection. Hearing Report/Bill Signing Report. [Google Scholar]

- 161.Connelly, McLaughlin . Witnesses for Smoke-Free Air Act Hearing. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 162.Foderaro LW. NY Times. Battling demons, and nicotine hospitals’ smoking bans are new anxiety for mentally ill. [Google Scholar]

- 163.El-Guebaly N, Cathcart J, Currie S, Brown D, Gloster S. Smoking cessation approaches for persons with mental illness or addictive disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:1166–1170. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.9.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Prochaska JJ, Gill P, Hall SM. Treatment of tobacco use in an inpatient psychiatric setting. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:1265–1270. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.11.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Prochaska JJ, Fletcher L, Hall SE, Hall SM. Return to smoking following a smoke-free psychiatric hospitalization. Am J Addict. 2006;15:15–22. doi: 10.1080/10550490500419011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Yano E. Japanese spousal smoking study revisited: how a tobacco industry funded paper reached erroneous conclusions. Tob Control. 2005;14:227–233. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.007377. discussion 233–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Barnes DE, Bero LA. Why review articles on the health effects of passive smoking reach different conclusions. JAMA. 1998;279:1566–1570. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.US Department of Health Education and Welfare. Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee of the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 169.Olincy A, Harris JG, Johnson LL, et al. Proof-of-concept trial of an alpha7 nicotinic agonist in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:630–638. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Harris JG, Kongs S, Allensworth D, et al. Effects of nicotine on cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:8. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Smith RC, Warner-Cohen J, Matute M, et al. Effects of nicotine nasal spray on cognitive function in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:637–643. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Jacobsen LK, D'Souza DC, Mencl WE, Pugh KR, Skudlarksi P, Krystal JH. Nicotine effects on brain function and functional connectivity in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:850–858. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Barr RS, Culhane MA, Jubelt LE, et al. The effects of transdermal nicotine on cognition in nonsmokers with schizophrenia and nonpsychiatric controls. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007 doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301423. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Scriabine A. CNS FORUM Advancements in clinical trials and drug development Philadelphia, PA, USA, July 29–30, 2003. CNS Drug Rev. 2003;9:389–395. [Google Scholar]

- 175.Targacept. Press Release: Targacept announces initiation of phase IIb development of AZD3480 (TC-1734) for cognitive deficits in schizophrenia [Google Scholar]

- 176.Evins AE, Cather C, Deckersbach T, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of bupropion sustained-release for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25:218–225. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000162802.54076.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Spiegel EP, Schrock DA, Smith MW. Effectiveness of a Transdermal Nicotine Replacement Intervention in Schizophrenic Smokers. New Orleans, La: American Psychological Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 178.Williams JM, Ziedonis DM, Foulds J. A case series of nicotine nasal spray in the treatment of tobacco dependence among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:1064–1066. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Dalack GW, Becks L, Hill E, Pomerleau OF, Meador-Woodruff JH. Nicotine withdrawal and psychiatric symptoms in cigarette smokers with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:195–202. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]