Abstract

Delusional paranoia has been associated with severe mental illness for over a century. Kraepelin introduced a disorder called “paranoid depression,” but “paranoid” became linked to schizophrenia, not to mood disorders. Paranoid remains the most common subtype of schizophrenia, but some of these cases, as Kraepelin initially implied, may be unrecognized psychotic mood disorders, so the relationship of paranoid schizophrenia to psychotic bipolar disorder warrants reevaluation. To address whether paranoia associates more with schizophrenia or mood disorders, a selected literature is reviewed and 11 cases are summarized. Comparative clinical and recent molecular genetic data find phenotypic and genotypic commonalities between patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder lending support to the idea that paranoid schizophrenia could be the same disorder as psychotic bipolar disorder. A selected clinical literature finds no symptom, course, or characteristic traditionally considered diagnostic of schizophrenia that cannot be accounted for by psychotic bipolar disorder patients. For example, it is hypothesized here that 2 common mood-based symptoms, grandiosity and guilt, may underlie functional paranoia. Mania explains paranoia when there are grandiose delusions that one's possessions are so valuable that others will kill for them. Similarly, depression explains paranoia when delusional guilt convinces patients that they deserve punishment. In both cases, fear becomes the overwhelming emotion but patient and physician focus on the paranoia rather than on underlying mood symptoms can cause misdiagnoses. This study uses a clinical, case-based, hypothesis generation approach that warrants follow-up with a larger representative sample of psychotic patients followed prospectively to determine the degree to which the clinical course observed herein is typical of all such patients. Differential diagnoses, nomenclature, and treatment implications are discussed because bipolar patients misdiagnosed with schizophrenia are severely misserved.

Keywords: schizophrenia, bipolar, mania, depression, Kraepelinian dichotomy, paranoia, psychosis

Introduction

Modern psychiatry began in the mid- to late 19th century when several syndromes including paranoia were consolidated by Emil Kraepelin and called dementia praecox,1 later renamed “schizophrenia” by Eugene Bleuler in 1911.2 The “Kraepelinian dichotomy” described 2 separate diseases to explain severe mental illness, schizophrenia and manic-depressive insanity or bipolar disorder.1 Bleuler2 and then Schneider3 emphasized that psychosis, to include a paranoid delusional system, was pathognomonic of schizophrenia and discounted the diagnostic implications of mood symptoms. A very different idea was presented in 1905 when Specht4 said that all psychoses were derived from mood abnormalities.5 Kraepelin had also linked paranoia and mood when he used the term “paranoid depression” to describe an illness with a high rate of suicide, severe depression, paranoia, and auditory hallucinations.1,5 The 1933 introduction of schizoaffective disorder6 recognized the diagnostic relevance of mood symptoms in psychotic patients, linked schizophrenia (psychosis) and mood disorders, and eroded the concept of the Kraepelinian dichotomy.7–11 Some now consider schizoaffective disorder to be a psychotic mood disorder and not a subtype of schizophrenia or a separate disorder.7–12 In addition, certain authors in the United Kingdom have associated paranoia with depression and delusional guilt.5 One group in the 1970s implied that about 95% of their sample of patients diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia actually suffered from mania because “classic bipolar” patients were observed to suffer paranoid delusions.13

Despite these linkages of paranoia and psychosis with mood disorders, the concepts of Bleuler2 and Schneider3 that bound paranoia and all functional psychoses to schizophrenia prevailed, and such cases typically have been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia or postschizophrenic depression, not as psychotic mood disorders.5 Paranoia continues to be associated with schizophrenia, rather than with bipolar disorder, both as the most common subtype and as a core diagnostic symptom, as reflected in the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10), and major textbooks of psychiatry.14

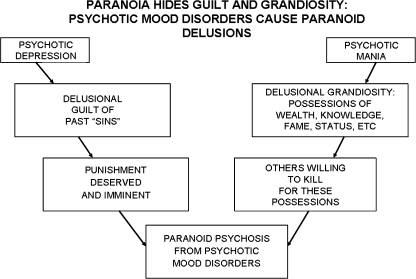

However, when mood disorders are explored as a source of paranoia, a different causal relationship presents itself (figure 1). If psychotic mood disorders explain many paranoid presentations, as suspected over 30 years ago,13 questions arise about the distinction between schizophrenia and psychotic mood disorders.7,8,13,15–19Selected reviews of symptoms, course, prognosis, family heritability, and epidemiology conclude that there are no disease-specific characteristics of schizophrenia and that the DSM diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia are common to psychotic bipolar disorder patients.7,8,15–20 Further indications of closure toward one disease derive from recent basic science data, especially molecular genetic and neurocognitive studies, that show considerable overlap and similarities between schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder.18–32 One author states that “ … of the (11) chromosome loci found for the transmission of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, eight have been found to overlap ....”28 Crow30,31 advances an explanation for the 3 or more loci that do not overlap between schizophrenia and bipolar that is compatible with a single disease to explain all 3 of the functional psychoses: “Epigenetic variation associated with chromosomal rearrangements that occurred in the hominid lineage and that relates to the evolution of language could account for predisposition to schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder and failure to detect such variation by standard linkage approaches.”

Fig. 1.

Psychotic Depression Can Cause Delusions of Exaggerated Severity of Past “Sins” Leading to Delusional Guilt. Such guilt stimulates thoughts that punishment is deserved and imminent. The fear of punishment, torture, and/or execution defines the paranoid psychosis that consumes these patients’ lives. Similarly, psychotic mania can cause delusional grandiosity of ownership of valuable possessions. A logical result is the delusional belief that others want these possessions and are going to kill to get them, leading to paranoid psychosis. Because these patients present with complaints of fear for their lives, the core symptoms of the mood disorder may be overlooked and a misdiagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia made.

There are established differences between psychotic and nonpsychotic bipolar disorders.15–17 Psychotic mood disorders are often phenotypically indistinguishable from schizophrenia, so it is likely that psychotic mood-disordered patients have been misdiagnosed with schizophrenia. Differences considered to exist between “schizophrenia” and “classic” (nonpsychotic) bipolar disorder may be explained by the differences between psychotic and nonpsychotic (classic) bipolar.

The symptom of paranoia, in particular, has been the focus of genetic studies. For example, although preliminary, familial aggregation data reveal that paranoid delusional proneness is an endophenotype common to patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder but not nonpsychotic bipolar disorder.16 Schulze et al17 extended this work by linking persecutory delusions (paranoia) to variance at a specific locus, the D-amino acid oxidase activator/G30, located on chromosome 13q34, in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and with psychotic bipolar disorder. More recent results link this locus primarily to mood disorders “across the traditional bipolar and schizophrenia categories.”29 Such genotypic overlap, when considered with the phenotypic similarities, suggests the hypothesis that the disease called paranoid schizophrenia may be psychotic bipolar disorder and not a separate disorder. Bipolar disorder is more likely than schizophrenia to be the single disease because bipolar is scientifically grounded with unique, disease-specific diagnostic criteria, while schizophrenia has no disease-specific criteria.7,12,15 The following review of 11 patients, each initially diagnosed with schizophrenia but subsequently revealed to suffer from a psychotic mood disorder, serves to illustrate these ideas (table 1). All subjects gave their written informed consent to participate in this Institutional Review Board-approved research.

Table 1.

Case Characteristics

| Case No. | Age/Sex; Job/School | ED Presentation | Initial Symptoms | Initial Diagnosis | Subsequent Symptoms | Paranoia Caused by | Actual Patient Experience (“Thread of Truth”) | Final Diagnosis |

| 1 | 58/M; Unemployed day laborer/college graduate, Vietnam Veteran | Handcuffed, paranoid, fearful, agitated, resistant, involuntary | Feared elimination by CIA; feared poison | PSa | Decreased sleep with increased activities; grandiosity; lost 20 pounds due to “no time to eat”; made over 300 phone calls to the CIA often between midnight and 4 AM | Believed that he possessed critical knowledge about the Vietnam war that was embarrassing to the US government who had sent the CIA to eliminate him | Had fought in Vietnam | BP-I manic, severe withb |

| 2 | 46/M; Military officer/college graduate, PhD in engineering | Escorted by MP’s, handcuffed, paranoid, fearful, agitated, resistant, involuntary | Feared for his life from assassination by KGB and NSA; coded messages from TV | PS | Decreased sleep with increased activities; grandiosity; called President Reagan multiple times; moved daily from motel to motel to escape assassination | Believed that he had a Star Wars missile design that the KGB and NSA wanted for themselves | Was a rocket engineer | BP-I manic, severe with |

| 3 | 28/M; Microbiology technician/college graduate | Delusional paranoia, assaultive, restrained in ED, involuntary | Feared his murder by Al Qaeda was imminent; feared poison | PS | Decreased sleep with increased activities; worked on his computer 24/7 for weeks; grandiosity; marked weight loss due to fear of poison | Believed God had named him as a Christian prophet and that Al Qaeda would assassinate him with anthrax because of his Christianity | Was a microbiologist and in New York City on November 11, 2001 | BP-I manic, severe with |

| 4 | 29/M; Musician | Police escort, delusional paranoia, violent, restrained, involuntary | Feared execution by Cuban Mafia; messages from TV and radio | PS | Decreased sleep with increased activities; grandiosity; moved from city to city to escape harm | Believed that he had a recording worth millions that the Cuban Mafia wanted | Was a Cuban musician who supported the anti-Castro effort | BP-I manic, severe with |

| 5 | 24/M; Unemployed/college graduate | Delusional paranoia, disorganized, voluntary | Feared execution by Cali Cartel | PS | Decreased sleep with increased activities; fleeing for his life; grandiosity; kept walking and lived on the street to avoid capture | Believed that he possessed a formula to make synthetic narcotics so the Cali Cartel wanted it and him dead | Was from Columbia, South America and a chemistry major | BP-I manic, severe with |

| 6 | 56/M; Unemployed house painter/high school graduate | Delusional paranoia, disorganized, suicidal, voluntary | Feared death at the hands of the devil and God; feared poison | PS, postschizophrenic depression | Psychotic, suicidal depression followed by psychotic mania when he ordered 10 000 oysters in the shells for a party for the governor of the state of North Carolina | Believed that he had sinned over 40 y before and deserved torture and death by God and the devil; believed that he was friend to the governor | Did steal $5 from his boss’ gas station at 15 y of age | MDD, severe withc; then BP-I, manic, severe with |

| 7 | 28/M; Fast-food restaurant worker/college graduate | Delusional paranoia, handcuffs, catatonia, coprophilia, involuntary | Feared his execution by hit men; poison | PS | Decreased sleep with increased activities; disorganization due to racing thoughts; grandiosity; premeditated corprophilia with a purpose to get transferred to escape hit men | Believed that he was to gain ownership of his bank, but hit men were sent to kill him to get the bank for themselves; planned on millions in purchases | Did make trips to the bank on a regular basis for his mom | BP-I manic, severe with |

| 8 | 40/F; Unemployed lawyer/law school graduate | Delusional paranoia, suicidal, voluntary | Auditory hallucinations keeping up a running commentary | PS | Psychotic, suicidal depression; delusional guilt; persecutory delusions; persistent psychosis with downward drift to homelessness; history of hypomanic episodes | Believed that she was such a failure that she deserved torture and death; then feared her torture and death | Lost several legal positions and then was fired from even menial jobs | BP-II, depressed, severe with |

| 9 | 54/F; Artist/master's degree | Police escort, delusional paranoia, assaultive, involuntary | Feared “rogue CIA and Cuban agents” trying to kill her; messages from TV | PS | Decreased sleep with increased activities; had flown from New York to Chicago at last minute; extensive grandiosity; angry; violent; loud; intrusive | Complex grandiose delusional system incorporating the jewels of the Queen of Spain, Fidel Castro, and the assassination of President Reagan | Had visited Spain and Cuba and had a distant relative with a low-level CIA position | BP-I, manic, severe with |

| 10 | 62/F; Unemployed/college graduate | Police escort, delusional paranoia, involuntary | Feared her imminent assassination by “anti-Jewish foreign agents” | PS | Decreased sleep with extensive writing to the US Department of State for 20–24 h a day sustained episodically over decades; fled lodging when TV or radio indicated she had been located; walked all night to escape; slept on the streets | Believed that she was an undercover foreign affairs advisor for the US State Department covertly tasked to protect the Jewish people | Had held a low-level job in the US government in her 20s | BP-I, manic, severe with |

| 11 | 36/F; Nurse/college graduate | Ambulance, unconscious due to overdose in a serious attempt to die | Feared her capture by law enforcement, sentencing to death and execution | PS or postschizophrenic depression | Psychotic suicidal depression; endorsed full manic episodes in the past with decreased sleep and a marked increase in dangerous activities due to spur of the moment impulses and lack of judgment | Believed that she had “murdered” by neglect a terminal, 4-y-old patient under her care in hospice | Had lost such a patient under her hospice care | BP-I, depressed, severe with |

Note: ED, emergency department; M, male; F, female; CIA, Central Intelligence Agency; MP, military police; KGB, (Soviet) State Security Committee; NSA, National Security Agency.

PS is schizophrenia, paranoid type.

BP-I, manic, severe with is bipolar type I, manic, severe with psychotic features.

MDD, severe with is major depressive disorder, severe with psychotic features.

Case 1

A 58-year-old Vietnam veteran living in a suburban neighborhood was presented to the emergency department (ED) in handcuffs accompanied by police. He reported to the interviewing psychiatrist that he had nailed shut his doors and windows except for small slits through which he “planned to fire on attacking Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) operatives.” Having amassed numerous small arms weapons including an illegal, fully automatic machine gun, he brought attention to himself by spraying automatic gunfire through his attic because he thought that “they had gotten into the attic.”

The patient's behavior and resistance in the ED necessitated involuntary commitment. On the unit, he was agitated and fearful, avoiding eye contact, any communication, and taking anything by mouth because he feared he would be poisoned. A thorough medical work-up for organic causes, including a urine drug screen, blood work, and imaging studies, was negative. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid type. After 3 days of intramuscular (IM) haloperidol (Haldol) 10 mg twice a day, he began to eat and drink as well as to reluctantly cooperate with the staff, providing further history.

This individual said that he had led illegal US government operations in Cambodia and had become convinced that the CIA intended to eliminate him for fear he would “publish his memoirs.” He said that during the past 2 weeks, he had called the CIA over 300 times, frequently between midnight and 4 AM. Further, he said that he had not slept or eaten for fear of “getting overrun” and had lost over 15 pounds. He admitted that his thoughts had been racing. The patient said that a war buddy he had called had told him to slow down and had finally hung up on him. He had stopped using his telephone for calls other than the CIA for “fear of wiretaps.”

Although he endorsed prior episodes of major depression, he had not sought treatment. His diagnosis was changed to bipolar disorder, type I (BP-I), manic, severe with psychotic features. Lithium was rapidly titrated to a therapeutic blood level and effectively stabilized his mood. In subsequent outpatient follow-up, the patient revealed that he had a paternal uncle who had previously been diagnosed with BP-I and was also taking lithium.

Case 2

Prior to the fall of the Soviet Union, a 46-year-old divorced senior military aerospace engineer presented to military police (MP) afraid for his life and with his briefcase chained to his wrist. His chief complaint was that the (Soviet) State Security Committee (KGB) and the National Security Agency (NSA) were following him and planned to “erase him.” He tried to leave the ED when he became suspicious of the interviewing physician. He was restrained by the MP’s and forcibly admitted to the locked unit. With affect of agitation and paranoia, he was prescribed an antipsychotic combined with a benzodiazepine. The patient's absent without leave status for over 2 months, his rank as an officer, and his high-level security clearance were confirmed. After 2 days on the unit, he admitted that he had “gone underground,” had moved every 2–3 days, and had not reported for duty in order to escape assassination. He claimed to have received coded messages from the TV over the previous 3–4 weeks, telling him that he was in danger of attack by the KGB “who had conspired with the NSA to eliminate him.” He was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid type.

Subsequently, the patient said that he had been working 20–24 hours every day for the past 2 months and had developed a “Star Wars” intercontinental ballistic missile interceptor system. A secret pocket of his briefcase contained several hundred pages of neatly drawn formulas, calculations, and scale drawings of his system. He had attempted numerous times to call the President, Ronald Reagan. He admitted losing weight, racing thoughts, no need for sleep, and increased energy during the previous 2/5 months. He had suffered 2 episodes of major depression in the past and had had several unrecognized hypomanic episodes, when he became more productive. He was given carbamazepine (Tegretol) that was appropriately titrated, and his diagnosis was changed to BP-I, manic, severe with psychotic features.

Case 3

A 28-year-old Eastern European, single, male, working as a microbiology technician, was brought to the ED by his parents. He tried to leave the ED, became assaultive, was forcibly restrained, and was admitted involuntarily. On the unit, he was mute, fearful, and socially withdrawn. He paced the floors, refusing food, water, or medicine because of his fear of poison. His laboratory work and physical examination revealed marked dehydration. He suffered a major motor seizure, but subsequent neurologic work-up was negative, and the seizure was attributed to his electrolyte imbalance. He was given IM antipsychotic medication and was forced to take intravenous fluid. The patient was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid type.

A medical student elicited the patient's history from his parents. They said that he had not slept for at least 2 weeks, had stopped going to work, and “was working on his computer 24/7.” They said that he had appeared distracted, frightened, and suspicious but was noncommunicative about whatever was bothering him. After several days on the unit, the patient said that he feared for his life because “God selected me as a prophet.” He said that Al Qaeda operatives had found out about his high Christian religious position and intended to kill him on September 11, 2002. This delusion may have related to his having been in New York a year earlier. The patient believed that Al Qaeda intended to send him anthrax and that he would die and be blamed for the resultant holocaust. He admitted that he suspected that the staff on the inpatient unit had been infiltrated by Al Qaeda operatives. It was learned that his maternal grandmother had suffered several “psychotic breakdowns.” His diagnosis was changed to BP-I, manic, severe with psychotic features, and mood-stabilizing medications were prescribed.

Case 4

A 29-year-old single male musician, of Cuban descent, presented to the ED in police custody. The patient was apprehended after striking a passerby on the street who he believed was a Cuban agent about to kill him. Saying that he feared for his life, he became suspicious of ED staff and seemed to be attending to unobserved external stimuli. He was prevented from leaving the ED after becoming aggressive, necessitating restraints, and involuntarily admission. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid type, and medicated with IM antipsychotics.

Because his psychosis resolved, the patient began to cooperate, revealing that he believed he possessed the recording of a song he had composed and performed that was “worth millions of dollars.” He believed the Cuban Mafia wanted the recording for the profit it would generate and were justifying their crime because his lyrics were anti-Castro in tone. Two weeks before his admission, he had begun staying up all night, vigilant, to protect himself, and was getting signals from the TV and radio warning him that the Cuban Mafia had located him. As a result, he had moved several times. As in the preceding cases, this patient's diagnosis and medications were appropriately changed, resulting in effective mood stabilization.

Case 5

A 24-year-old Columbian, unemployed, college graduate with a major in chemistry presented to the ED in a disheveled, unshaven, and unbathed state. He said that he had been fleeing from Cali Cartel agents for over 6 months, and when he sought protection from the police, they had told him to come to the ED. He was disorganized and suspicious, appearing to address unseen external stimuli. He was admitted voluntarily and diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid type.

More careful interviews with him revealed that the reason behind his fears was his belief that he had developed a formula to cheaply produce a very potent narcotic. His synthetic drug would eliminate the need to grow opium or coca. He believed the Cali Cartel had discovered his invention and had sent agents to torture and kill him for the formula. He knew the names of the Cartel bosses and discussed them as if they were intimate acquaintances. He had not slept for days, fleeing the Cartel's agents. Again, the diagnosis was changed.

Case 6

A 56-year-old unemployed house painter, escorted to the ED by the police, was voluntarily admitted to the psychiatric locked ward because “the devil is coming to take me away.” A passerby had called the police after seeing this man standing suspiciously on a bridge. Claiming that he deserved to die, he wanted to jump to his death before the devil got him. He was unshaven, unclean, and emaciated. On the unit, his affect remained terrified, tearful, and suspicious; he would not accept anything by mouth. He said that he heard voices of the devil and God arguing over who should kill him. He said that he heard the devil say that he was “coming up the hospital stairs” and “had corrupted the nursing staff.” He was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid type or postschizophrenic depression, and forcibly treated with IM haloperidol (Haldol).

As he began to improve, he endorsed the symptoms of a major depressive episode that had escalated over the prior 8 months. He repeatedly said that he deserved to die for a past “sin.” He asked for help to die in order to prevent “falling into the hands of the devil.” Several days later, he revealed that his sin was stealing $5 from the gas station where he worked when he was 15 years old. He said that he had had “a first date with a girlfriend and no money.” His diagnosis was changed to major depressive disorder, severe with psychotic features, and he was given amitriptyline (Elavil) in addition to the haloperidol.

Nine months later, he was readmitted in handcuffs. His wife had called the sheriff after a dump truck entirely filled their front yard with 10 000 fresh oysters in the shell. The patient exhibited racing thoughts, pressed speech, irritability, and said that he had not slept “for weeks” while planning a party for the state legislature and governor. His diagnosis and medications were changed again. Lithium combined with valproic acid (Depakote) stabilized his mood. The implications of his misdiagnoses and inappropriate pharmacotherapy are discussed below.

Case 7

A 28-year-old single, never-married male was escorted to the ED by law enforcement officers after neighbors reported his bizarre behavior. He had been kneeling motionless on his mother's front lawn and had remained in a stiff kneeling position (catatonic) when the police picked him up. He said that the “hit men” hidden across the street had aimed “deadly ray guns all around me so that if I moved an inch, I was dead.” He said that the hit men had been after him for over a year but had recently picked up his trail and his execution was imminent. He was college educated but worked menial jobs, had always lived with his mother, and described himself as a “loner.” On the second night of his inpatient stay, the staff found him cowered in the far corner of his room, naked, having smeared his feces in his hair, face, and mouth. He later said that he did this to get himself transferred to the state hospital because the staff at the academic medical center had been “infiltrated by the hit men.” He was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid type.

Because his psychosis began to resolve, he volunteered for a student interview course where he revealed that 3 years prior to his admission he had suffered a major depressive episode followed by a hypomanic period when he began to think that ownership of his mother's local bank that he frequented was going to be transferred to him. Over the ensuing months, he began to make plans about the use of his newfound wealth listing several million dollars of purchases that included a specific local mansion, a villa in France, and 6 cars. He said that he had planned on running for governor of the state. Over the weeks before his admission, he said that he could not sleep and had become terrified when he heard the voice of God warning him of danger from the hit men who were “closing in to kill me so that they could have the bank for themselves.” His diagnosis and medications were changed.

Case 8

A 40-year-old female, unemployed lawyer presented to the ED frightened for her life and unable to stop sobbing. She would not commit to safety saying that she deserved to die but was afraid. She had tried to escape punishment by not leaving her room for the past 2 weeks. She held a strong faith in God but believed he had told her that she would be punished and executed because she was a “worthless failure.” She wanted to take her own life rather than continuing to suffer the knowledge that she would soon be tortured and killed. The patient said that over the past several months, God had frequently kept up a running commentary on her activities, often threatening that her end was near. Because of her extensive auditory hallucinations, especially of God's voice “keeping up a running commentary”—one of Schneider's first-rank, traditionally pathognomonic symptoms of schizophrenia3,14—she was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid type.

As her condition improved, she said that her father, also a lawyer, had named her after a famous lawyer and had influenced her to go to law school against her wishes. After graduation, she was fired from several law firms because of episodes of depression. She considered herself an overwhelming failure, having let God and her family down. Over the past 6 months, she began to believe that she had a special relationship with God to “save the world from evil” and to make up for her failures as a lawyer. As she became more and more involved in charity work, she lost her menial but paying job and believed that another failure mandated her death. Because of a history of hypomanic episodes documented by a significant other and a family history of hypomania and/or mania, her diagnosis was changed to BP-II, depressed, severe with psychotic features. Lamotragine (Lamictil) was prescribed with only modest stabilizing effects. Despite combinations of at least 3 mood stabilizers plus atypicals, her condition deteriorated and became treatment resistant and persistent with chronic cognitive defects, especially poor executive function, preventing her employment. She became so irritable that she lost her house and family to divorce and alienated her once supportive biological family. At last contact, she had not been motivated to file for disability and may have been forced to live on the street.

Case 9

This obese, 54-year-old, single, female artist from New York City with a master's degree in art history from Tulane University was taken into custody in the Chicago Airport by law enforcement officers after her loud warnings of the imminent assassination of President Reagan and herself. In the ED, she became aggressive and was admitted involuntarily. Upon admission, she was frightened for her life from “rogue CIA and Cuban agents” who she believed were plotting to kill her and the president. God had warned her “in a clear voice” in the airport that the CIA agents had followed her from New York. The patient also believed that she received instructions through the TV in the airport. She was diagnosed with chronic paranoid schizophrenia because her records revealed over 10 prior admissions with this diagnosis.

After several days, her fear was obscured by uncharacteristic irritability and anger. She did not sleep until medicated with antipsychotic drugs. She revealed her delusional involvement in an elaborate scheme that included Fidel Castro, President Reagan, and the jewels of the Queen of Spain worth “millions of dollars.” Her delusions may have been seeded by the facts that she had visited Cuba and Spain as a small child and that a distant cousin held a position at the CIA. The patient endorsed for the past 6 months a lack of need for sleep, racing thoughts, irritability, and increased activities. She had experienced similar grandiosity prior to past hospitalizations. She suffered with tardive dyskinesia, having been given IM injections of fluphenizine (Prolixin) monthly for over 2 decades. Again, her diagnosis and treatment were changed on the basis of her disease-specific grandiosity and other core diagnostic symptoms of mania.

Case 10

A 62-year-old widowed, unemployed female, found on the street inappropriately hiding behind a car and wearing a white sheet, was escorted to the ED by law enforcement. She appeared to be fearful and was carrying on an incomprehensible, running “conversation” with no obvious interlocutor. She was admitted involuntarily. Her daughter, a registered nurse, said that her mother feared for her life from “anti-Jewish foreign agents” who she believed intended to assassinate her. She said that her mother moved frequently, sometimes weekly and in the middle of the night. She slept on the street to get away from the agents. She learned when she was safe and when the agents had discovered her new residence by way of “coded” TV and radio messages. The patient's daughter said that her mother had behaved in this manner for decades. She was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid type.

Further history from the daughter revealed that the patient often did not sleep more than an hour or 2 per night over months to years because she “had to write critical letters” to her US government handlers. Saying that she held a US State Department undercover position as a “foreign affairs advisor” and was tasked for the “protection of the Jewish race,” she had written hundreds if not thousands of multipage letters to the State Department. Her daughter described her as never depressed but constantly vigilant, hyper, grandiose, and suspicious. The patient believed that she had been involved in the J. F. Kennedy assassination. Her diagnosis, too, was changed to BP-I, but she refused medications and continued to function in a chronic and persistently psychotic state. Her life consisted of “corresponding” with the State Department on a daily basis and fleeing from motel to various relatives’ homes and back again.

Case 11

This 36-year-old, multiply divorced female nurse was brought by ambulance to the ED unconscious, after an overdose on benzodiazepines. After 3 days on a ventilator and 3 more days in the intensive care unit, she was transferred to psychiatry. There she said that she wanted to die at her own hands rather than be arrested by law enforcement, imprisoned, and sentenced to death in the electric chair. She believed that her death was imminent. She had suddenly stopped going to work for fear of being apprehended and arrested. She had suffered several hospitalizations, with the diagnosis of chronic paranoid schizophrenia, which was assigned at this admission as well. Postschizophrenic depression was also considered.

The patient said that once her incompetence was discovered by her hospital administration, she would be prosecuted and executed for murder. She felt that she deserved to be punished but was afraid of death. Her “crime” involved the death of a 4-year-old child suffering from terminal leukemia and under her hospice care. Upon careful questioning, the patient was admitted to past episodes of decreased need for sleep, increased activities, racing thoughts, the ability to work 3 jobs at once without fatigue, and poor decisions with dangerous outcomes such as unprotected sex with unknown men. These episodes lasted several months and were usually followed by severe depressions. Her diagnosis was changed to BP-I, depressed, severe with psychotic features. Stability of her mood required lithium, carbamazepine (Tegretol), and lamotragine (Lamictil).

Summary and Conclusions

These 11 cases clarify the contention that delusional paranoia can associate with a core disturbance of mood in functionally psychotic patients. In contrast to the concept of Bleuler2 and Schneider3, but as previously suggested,4,5 delusional guilt, due to severe depression, underlies the belief that punishment is deserved and imminent, but this is mixed with intense fear for survival (figure 1). Cases 6, 8, and 11 are examples (table 1). Just as psychotic depression can lead to guilt-induced paranoia, manic grandiosity readily proceeds to paranoia. Cases 1–5, 7, 9, and 10 demonstrate that mania can lead to grandiose delusions of ownership of possessions of exaggerated value that others want. The fear for survival, ie, paranoid delusions, develops and escalates as grandiose, manic patients begin to believe that others are willing to inflict harm to gain their possessions for themselves (figure 1). The elevated significance of those threatening, such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation, CIA, Internal Revenue Service, KGB, the Mafia, God, or the devil, is an indication of grandiosity and mania (table 2).

Table 2.

Symptoms Potentially Suggestive of a Psychotic Mood Disorder, Not Schizophrenia, in Functionally Psychotic Patients

| 1. Paranoia (fear for one's life: punishment, poison, torture, execution) |

| 2. Delusional grandiosity (valuable possessions) |

| 3. Delusional guilt (past sins) |

| 4. Persecution by high-profile groups (FBI, CIA, KGB, IRS, God, the devil, etc) |

| 5. Psychosis (both mood-congruent and mood-incongruent hallucinations and/or delusions) |

| 6. Atypical increase in goal-directed behavior/activities especially involving “spur of the moment” decisions: religious, legal, political, sexual, cleaning, phoning, writing, loud music, partying, travel |

| 7. Atypical increase in emotion: anger, elation, irritability, intrusiveness, sadness, crying, suicidality |

| 8. Absence of pleasure and/or emotion (depression): anhedonia, flat affect, avolition, alogia |

| 9. Behavior causing disturbance: police called, assaultive, loud, neighbor's complaints |

| 10. History of major depression or mania/hypomania |

| 11. Family history of bipolar or major depression |

| 12. DSM criteria for bipolar, manic, depressed, or mixed |

| 13. Good premorbid or current social life: school officer, sports, gangs, dated, past long-term relationship, formally married, children |

Note: FBI, Federal Bureau of Investigation; CIA, Central Intelligence Agency; KGB, (Soviet) State Security Committee; IRS, Internal Revenue Service; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Although these cases presented over a 25-year period, there are several commonalities (table 1). Each patient was admitted while experiencing an intense, delusional fear for his/her life. The majority were escorted to the ED by law enforcement, handcuffed, or involuntarily committed. Patient aggression and restraint were frequently due to a broadening paranoia that the ED or ward staff was part of the plot to kill them. At least 4 cases feared that they would be poisoned. Case 7 engaged in coprophagia in order to get himself transferred to the state hospital to escape the “infiltrated” academic ward staff. Coprophilia and coprophagia, traditionally considered pathognomonic of schizophrenia, can occur in psychotic mood disorders as shown in Case 7.18 Patient focus, at presentation, was on self-preservation, and these patients volunteered no mood symptoms, and questions about mood were apparently inadequate. The overwhelming paranoid psychoses consistently led to misdiagnoses of schizophrenia, paranoid type (table 1). However, the acquisition of additional history by various means in each case revealed fundamental mood-based symptoms that led to the delusional paranoia and to a change in the diagnosis to that of a mood disorder, severe with psychotic features.

Despite Kraepelin's recognition of a relationship between paranoia and depression,5 the influence from Bleuler2 and Schneider3 resulted in the association of paranoia and even depression with schizophrenia, not with a mood disorder. The DSM still uses symptoms common to moderate and severe depression, such as affective flattening, alogia, and avolition, as diagnostic “negative symptoms of schizophrenia.” Patients with “deficit schizophrenia” and restricted affect may also meet criteria for psychotic depression. Other examples of Bleuler's2 and Schneider's3 impact in linking depressive symptoms to schizophrenia rather than to mood are found in the ICD-10 and other literature that classify “postschizophrenic depression” as a subtype of schizophrenia. The hypothesis that this condition is a severe depression with psychotic symptoms that are remitting, revealing symptoms of depression, not a type of schizophrenia, can be tested. Cases in point are the diagnoses of postschizophrenic depression initially considered in Cases 6 and 11. These patients subsequently endorsed histories of manic episodes and thus warranted diagnoses of psychotic bipolar disorder, depressed. Recent conclusions from at least 3 groups imply that depression is a risk factor for subsequent psychosis and a diagnosis of schizophrenia,33–35 not a diagnosis of a psychotic mood disorder, despite the evidence that psychotic bipolar disorders usually begin with depression.36 Depression is a risk factor for psychotic depression and psychotic mania; psychotic thought processes are common to severe depression and mania.37

Traditionally considered unique to schizophrenia, psychosis, persistent cognitive defects, a “deficit” state of restricted affect, and “downward drift” are now described in severe bipolar patients, especially during depression and even during euthymia (table 3).38–41 Thus, as shown in the DSM-IV-TR “Specifiers” section in the chapter on mood disorders, some patients with severe mood disorders deteriorate and never reexperience euthymia or a prodromal level of function (table 3). Cases 8 and 10 are examples. This prognosis is not typical of mood-disordered patients, and the frequency of such a downhill, chronically dysfunctional course in mood-disordered patients, is underrecognized. Case 8 is illustrative of the potential for a classic BP-I patient to develop persistent psychosis without remission leading to a chronic “downhill drift” in society to permanent deficit dysfunctionality with marked cognitive defects.

Table 3.

DSM-IV-TR Specifiers for the Mood Disorders

| A. Presenting state—for BP: manic, depressed, mixeda; for UP: single episode or recurrent |

| B. Severity: mild, moderate, severe without or with psychotic featuresa; partial and full remission |

| C. Course/onset: chronic (symptoms over 2 y)a, seasonal affective D/O, rapid cyclinga (at least 4 episodes/y), postpartum onset (within 4 wk), with or without full interepisode recoverya |

| D. Features: catatonica, melancholic, atypicala |

Note: DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision; BP, bipolar; UP, unipolar; D/O, disorders.

Signs and symptoms associated or confused with schizophrenia.

This article concurs with prior conclusions that bipolar disorder is often misdiagnosed as unipolar depression or schizophrenia and that misdiagnosed bipolar patients are underserved as demonstrated by Case 6, who was misdiagnosed for years with unipolar depression and whose rate of cycling was likely increased because of the administration of antidepressants without mood-stabilizing medications.7,8,15,36,42,43 Several cases, especially 7, 9, 10, and 11, were repeatedly misdiagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective because of their psychotic symptoms and were given antipsychotic medications without mood stabilizers over many years with substantial ill effects. In addition to antipsychotic-induced movement disorders (Case 9), the rate of cycling and the risk for suicide increase in misdiagnosed bipolar patients not given mood-stabilizing medications.42,43 The use of antipsychotics in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia is increased both in dosage and in time of administration with greater risk for additional adverse effects such as the metabolic syndrome and sudden death in older patients.44,45

A canon of medicine holds that when one disease can account for symptoms attributed to several, there is usually only one: in this case, there is substantial support for the hypothesis that the disease is a psychotic mood disorder. However, paranoid schizophrenia remains the most common subtype, and paranoia has been said to be ubiquitous in all subtypes of schizophrenia,46 but “paranoid” delusions in functionally psychotic patients appear to derive instead from the grandiosity of mania or the guilt of depression (figure 1). The “continuum theory” proposes a single underlying process and variance at a common locus in support for an absence of zones of rarity between the traditional functional psychoses.12,15,30,31,40 A rapidly accumulating molecular genetic database from laboratories in both the United States and United Kingdom substantiates genotypic overlap in addition to the phenotypic similarities noted above.20–31 These data invite the hypothesis that schizophrenia has been confused with psychotic mood disorders and that psychotic mood may account for most, if not all, of the functional psychoses.7,8,12,13,15–19,21,27 Mixed states of psychotic bipolar disorder are most likely to be misdiagnosed as schizophrenia because symptom severity and chronicity of course are typically more severe, and these mixed bipolar patients are more likely to be treatment resistant. Such characteristics have traditionally been associated with schizophrenia, but severe mixed states of bipolar commonly demonstrate such symptom severity, course chronicity, and treatment resistance (table 3).

The core issue in the accurate diagnosis in functionally psychotic patients is the attention given to mood symptoms vs psychotic symptoms in the initial diagnostic interview. The traditional concept that “a touch of schizophrenia (psychosis) is schizophrenia” may be wrong and may warrant replacement with “a touch of mood disturbance in psychotic patients is a psychotic mood disorder.” In the absence of mood symptoms, organic disorders may explain some paranoid presentations.47,48 Site-specific deep brain electrode stimulations for the treatment of epileptic patients have implicated specific brain areas as sources of paranoid ideation.48

Limitations of this presentation include the review of only a selected, comparative literature reporting similarities and overlap between schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder. There are substantial data suggesting that schizophrenia is a bona fide disease distinct from bipolar disorder, but these results are extensive and have been reviewed elsewhere.12,13,15,18,20,27,30,38,49–51 One group has questioned the validity of all research on schizophrenia based on non-disease–specific diagnostic criteria.7 Some authors have suggested that the use of schizophrenia as a diagnosis be discontinued because the diagnostic criteria of schizophrenia are explained by psychotic mood disorders. Abandoning Kraepelin's dichotomy without observable pathophysiology is challenging despite his own reversal, but “the beginning of the end of the Kraepelinian dichotomy” has already been predicted.21 As previously noted, “Unfortunately, once a diagnostic concept such as schizophrenia … has come into general use it tends to become reified. That is, people too easily assume that it is an entity of some kind that can be evoked to explain the patient's symptoms and whose validity need not be questioned.52”

Acknowledgments

The author has had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The author would like to acknowledge Martha Breckenridge and Anita Swisher for technical assistance.

References

- 1.Kraepelin E. Clinical Psychiatry. New York, NY: William Wood Company; 1913. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bleuler E. Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias. New York, NY: International Universities Press; 1911. 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneider K. Clinical Psychopathology. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton, Inc.; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Specht G. Chronic mania and paranoia. Zbl Nervenheilk. 1905;28:590. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doran AR, Breier A, Roy A. Differential diagnosis and Diagnostic systems in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1986;9:17–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasanin J. The acute schizoaffective psychoses. Am J Psychiatry. 1933;13:97–126. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pope HG, Lipinski JF. Diagnosis in schizophrenia and manic-depressive illness, a reassessment of the specificity of “schizophrenic” symptoms in the light of current research. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35:811–828. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770310017001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lake CR, Hurwitz N. Schizoaffective disorders are psychotic mood disorders; there are no schizoaffective disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2006;143:255–287. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuang MT, Simpson JC. Schizoaffective disorder: concept and reality. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10:14–25. doi: 10.1093/schbul/10.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Procci WR. Schizo-affective psychosis: fact or fiction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:1167–1178. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770100029002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maier W. Do schizoaffective disorders exist at all? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;13:369–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lake CR, Hurwitz N. Schizoaffective disorder merges schizophrenia and bipolar disorders as one disease—there is no schizoaffective disorder: an invited review. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20:365–379. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3281a305ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abrams R, Taylor MA, Gaztanaga P. Manic-depressive illness and paranoid schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1974;31:640–642. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1974.01760170040006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition-TR. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maier W, Zobel A, Wagner M. Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: differences and overlaps. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19:165–170. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000214342.52249.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schurhoff F, Szoke A, Meary A, et al. Familial aggregation of delusional proneness in schizophrenia and bipolar pedigrees. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1313–1319. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulze TG, Ohlraun S, Czerski P, et al. Genotype-phenotype studies in bipolar disorder showing association between the DAOA/G30 locus and persecutory delusions: a first step toward a molecular genetic classification of psychiatric phenotypes. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2101–2108. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lake CR, Hurwitz N. 2 Names, 1 disease: does schizophrenia = psychotic bipolar disorder? Curr Psychiatry. 2006;5:43–60. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lake CR, Hurwitz N. The schizophrenias, the neuroses and the covered wagon. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3:133–143. doi: 10.2147/nedt.2007.3.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berrettini WH. Are schizophrenic and bipolar disorders related? A review of family and molecular studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:531–558. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00883-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craddock N, Owen MJ. The beginning of the end for the Kraepelinian dichotomy. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;184:384–386. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.5.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berrettini W. Evidence for shared susceptibility in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet. 2003;123:59–64. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.20014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hodgkinson CA, Goldman D, Jaeger J, et al. Disrupted in schizophrenia 1 (DISC1): association with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:862–872. doi: 10.1086/425586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maziade M, Roy MA, Chagnon YC, et al. Shared and specific susceptibility loci for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a dense genome scan in Eastern Quebec families. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:486–499. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green EK, Raybould R, Macgregor S, et al. Operation of the schizophrenia susceptibility gene, neuregulin 1, across traditional diagnostic boundaries to increase risk for bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:642–648. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schumacher J, Jamra RA, Freudenberg J, et al. Examination f G72 and D-amino-acid oxidase as genetic risk factors for schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:203–207. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Craddock N, O'Donovan MC, Owen M. The genetics of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder dissecting psychosis. J Med Genet. 2005;42:193–204. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.030718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fawcett J. What do we know for sure about bipolar disorder? Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1–2. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams NM, Green EK, Macgregor S, et al. Variation at the DAOA/G30 locus influences susceptibility to major mood episodes but not psychosis in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:366–373. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crow TJ. The continuum of psychoses and its genetic origins. The sixty-fifth Maudsley lecture. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;156:788–797. doi: 10.1192/bjp.156.6.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crow TJ. How and why genetic linkage has not solved the problem of psychosis: review and hypothesis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:13–22. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McIntosh AM, Harrison LK, Forrester K, Lawrie SM, Johnstone EC. Neuropsychological impairments in people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder and their unaffected relatives. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:378–385. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.5.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hafner H, Maurer K, Trendier G, an der Heiden W, Schmidt M, Konnecke R. Schizophrenia and depression: challenging the paradigm of two separate diseases—a controlled study of schizophrenia, depression and healthy controls. Schizophr Res. 2005;77:11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krabbendam L, Myin-Germeys I, Hanssen M, et al. Hallucinatory experiences and onset of psychotic disorder: evidence that the risk is mediated by delusion formation. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110:264–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiser M, Reichenberg A, Rabinowitz J, et al. Association between nonpsychotic psychiatric diagnoses in adolescent males and subsequent onset of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:959–964. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.10.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Angst J, Sellaro R, Stassen HH, Gamma A. Diagnostic conversion from depression to bipolar disorders; results of a long-term prospective study of hospital admissions. J Affect Disord. 2005;84:149–157. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lake CR. Disorders of thought are severe mood disorders: the selective attention defect in mania challenges the Kraepelinian dichotomy—a Review. Schizophr Bull. 2007 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm035. May 21, 2007; doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor MA. Are schizophrenia and affective disorder related? A selective review. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:22–32. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martinez-Aran A, Vieta E, Reinares M, et al. Cognitive function across manic or hypomanic, depressed and euthymic states in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:262–270. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zuibieta JK, Huguelet P, O'Neil RL, Giordani BJ. Cognitive function in euthymic bipolar I disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2001;102:9–20. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00242-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olincy A, Martin L. Diminished suppression of the P50 auditory evoked potential in bipolar disorder subjects with a history of psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:43–49. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goodwin FK. The biology of recurrence: new directions for the pharmacologic bridge. J Clin Psychiatry. 1989;50:40–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calabrese JR, Shelton MD, Bowden CL, et al. Bipolar rapid cycling: focus on depression as its hallmark. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:34–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zarate CA, Jr, Tohen M. Double-blind comparison of the continued use of antipsychotic treatment versus its discontinuation in remitted manic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:169–171. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Artaloytia JF, Arango C, Lahti A, et al. Negative signs and symptoms secondary to antipsychotics: a double-blind, randomized trial of a single dose of placebo, haloperidol, and risperidone in healthy volunteers. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:488–493. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carpenter WT, Jr, Bartko JJ, Carpenter CL, Strauss JS. Another view of schizophrenia subtypes. A report from the international pilot study of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:508–516. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770040068012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin MJ. A brief review of organic diseases masquerading as functional illness. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1983;34:328–332. doi: 10.1176/ps.34.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arzy S, Seeck M, Ortigue S, Spinelli L, Blanke O. Induction of an illusory shadow person; Stimulation of a site on the brain's left hemisphere prompts the creepy feeling that somebody is close by. Nature. 2006;443:287. doi: 10.1038/443287a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ketter T, Wang PW, Becker OV, Nowakowska C, Yang Y. Psychotic bipolar disorders: dimensionally similar to or categorically different from schizophrenia? J Psychiatr Res. 2004;38:47–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(03)00099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Korn ML. Schizophrenia and Bipolar disorder: an evolving interface. Medscape Psychiatr Ment Health. 2004;9:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moller HJ. Bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: distinct illnesses or a continuum? J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kendell R, Jablensky A. Distinguishing between the validity and utility of psychiatric diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:4–12. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]