Abstract

Background

The purpose of the current study is to evaluate the role of bioluminescence imaging (BLI) in the determination of NF-κB activation in cardiac allograft rejection and ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Methods

To visualize NF-κB activation, luciferase transgenic mice under the control of a mouse NF-κB promoter (NF-κB-Luc) were utilized as donors or recipients of cardiac grafts. Alternatively, NF-κB-Luc spleen cells were adoptively transferred into Rag2−/− mice with or without cardiac allografts. BLI was performed post-transplantation to detect luciferase activity that represents NF-κB activation.

Results

The results show that luciferase activity was significantly increased in the cardiac allografts when NF-κB-Luc mice were used as recipients as well as donors. Luciferase activity was also elevated in the wild-type (WT) cardiac allografts in Rag2−/− mice that were transferred with NF-κB-Luc spleen cells. CD154 mAb therapy inhibited luciferase activity and induced long-term survival of cardiac allografts. TLR-9 ligand, CpG DNA, enhanced luciferase activity and abrogated tolerance induction by CD154 mAb. Luciferase activity was also increased in ischemia-reperfusion injury of the cardiac grafts.

Conclusion

BLI using Luc-NF-κB mice is a non-invasive approach to visualize the activation of NF-κB signaling in mouse cardiac allograft rejection and ischemia-reperfusion injury. CD154 mAb can inhibit NF-κB activation, which is reversed by TLR engagement.

Keywords: BLI, cardiac transplantation, TLR, NF-κB, mice

INTRODUCTION

NF-κB is a potent pro-inflammatory signal transduction molecule, and NF-κB activation amplifies the expression of multiple chemokine and cytokine genes involved in the innate and adaptive immune responses (1, 2). However, our knowledge of the role of NF-κB in the mediation of alloimmune response remains limited due to the difficulties in obtaining in vivo data.

A quantitative method with transgenic mice for evaluating NF-κB activation in vivo has been developed recently using bioluminesce imaging (BLI) (3–5). The transgenic mice have been engineered to possess a construct comprising the proximal 59 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) long terminal repeat (LTR) driving the expression of Photinus luciferase complementary DNA (cDNA). The proximal HIV-LTR is a NF-κB-responsive promoter (3), containing a TATA box, an enhancer region between 282 and 2103. In these genetically modified mice (referred to as NF-κB-Luc mice), luciferase production and intracellular accumulation are dependent on NF-κB-activated gene transcription; therefore, BLI using NF-κB-Luc mice provides a useful in vivo reporter-based assay system in which to analyze NF-κB enhancer activity in response to a variety of inflammatory signals including alloimmune response (3, 6).

Previous reports show that the Toll-like receptor (TLR)/NF-κB signaling pathway had been implicated in the innate and adaptive responses in vivo (7, 8). After activation of TLR, MyD88, an adaptor, is recruited into the TLR complex that induces IL-1 receptor associated kinase (IRAK) and TNF receptor associated factor-6 (TRAF-6). Both IRAK and TRAF dissociate and activate the intracellular transcriptional factor, NF-κB. In this manner, NF-κB contributes to immunologically mediated diseases and alloimmune response (9, 10). Immunosuppressants, such as cyclosporine A, can inhibit NF-κB activation in a cardiac transplantation mouse model. Decreased mRNA levels of the p50/p65 subunits of NF-κB delayed rejection to cardiac allograft (1, 11, 12). Recent reports suggest that TLR signaling mediates the alloimmune response. TLR engagement prevents tolerance induction and impairs tolerance maintenance induced by CD154 mAb treatment (7, 11). The direct evidence that whether anti-CD154 monoclonal antibody (mAb) treatment can regulate NF-κB signaling is still lacking.

Increasing evidence has also suggested that the innate immune response involving the TLR/NF-κB pathway mediates tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury (13–15). TLR activation stimulates the downstream transcriptional factor, NF-κB. Activation of NF-κB induces gene programs leading to transcription of factors which promote inflammation, among them leukocyte adhesion molecules and cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNFα. A quantitative method of NF-κB assessment using transgenic NF-κB-Luc mice has been developed (3, 16, 17), which provides a useful in vivo reporter-based assay system in which to analyze NF-κB enhancer activity in response to a variety of inflammatory signals.

In this study, we used BLI for the detection of NF-κB activation in a cardiac transplantation mouse model and tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury. Our results show that luciferase activity is elevated in the cardiac allografts and the cardiac grafts suffering from ischemia-reperfusion injury. CD154 mAb therapy has the capacity of inhibiting NF-κB activation which can be reversed by TLR engagement with CpG DNA. The current study suggests that BLI using NF-κB-Luc mice is a useful non-invasive approach for the detection of NF-κB activation during allograft rejection and tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and cardiac transplantation

C57BL/6, Balb/c mice, and Rag2−/− were purchased from Jackson Laboratory, the National Cancer Institute (NIH, Frederick, MD), and Taconic (Hudson, NY). Mice expressing luciferase transgene under the control of a NF-κB promoter (NF-κB-Luc) on Balb/c (H-2d) and C57BL/6 (H-2b) were kindly provided by Dr. Tim Blackwell (17) and were utilized for the detection of NF-κB activation after cardiac transplantation using BLI. All mice were housed in pathogen-free conditions in the Division of Animal Care at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, according to the National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Heterotopic vascularized cardiac transplantation was performed using microsurgical techniques as described previously (18). The donor aorta was sutured to the recipient aorta in an end to side fashion using 10-0 sutures (USSC) and the inferior vena cava (IVC) to the recipient IVC in the same manner. Tolerance was induced by anti-CD154 mAb (MR1) at 1mg/mouse, i.v. at 0 d, +1 d, and +2 d relative to transplantation. The mAbs were purified in our laboratory following our previous protocol (7, 19, 20). For TLR engagement, CpG DNA (CpG-B ODN 1826, Coley Pharmaceutical Group Ltd, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) was administered (100 µg per mouse × 3 at day 0, day 1, and day 3). The day the graft stopped beating was defined as the time of rejection. Recently rejected and long-term surviving mice, engrafted with cardiac allografts, were sacrificed for histopathological examinations (20, 21). The grafts were frozen rapidly in liquid nitrogen or stored in 10% formalin solution and four to six µm sections were stained with H&E for the assessment of cell infiltration.

To visualize the NF-κB activation in the cardiac grafts that suffered from ischemia-reperfusion injury, syngeneic NF-κB-Luc (Balb/c) cardiac grafts were preserved in cold (4°C) University of Wisconsin (UW) solution for 16hr and then transplanted into WT Balb/c recipients. Syngeneic NF-κB-Luc (Balb/c) cardiac grafts were transplanted immediately into WT Balb/c recipients as control (with very short ischemic time).

In vivo bioluminescence imaging (BLI) BLI was performed as previously described (3, 5). After anesthesia with isoflurane, luciferin (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) was injected intravenously at a dose of 50mg/kg for NF-κB-Luc mice as recipients and 100mg/kg for NF-κB-Luc as donors. Mice were housed inside a light-tight box and imaged with an ICCD camera (Hamamatsu C2400-32, Xenogen Corp). Bioluminescence in control mice without transplantation was also assessed. Light emission through the ventral body was detected as photon counts over a standardized area of the organs of interest using the ARGUS-50 software for image processing expressed as Regions of Interest (ROI) (3, 22, 23). Since luciferase production is under the control of the NF-κB promoter, luciferase activity represents NF-κB activation and the value of ROI represents the density of luciferase activity. Bioluminescence is dependent on tissue penetration, and the intensity or light emission from the cardiac grafts may vary. To reduce the variability, all mice were positioned on their back, which allowed us to obtain signal intensity in a standard bed fashion.

Tissue luciferase activity tests

Luciferase in the spleen, draining lymph nodes (along with the aorta adjacent to cardiac graft), and cardiac grafts were determined by Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Medison, WI). The tissues were pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in a lysis buffer, and clarified by centrifugation at 12,000 g for 2 min at 4°C. Luciferase activity was measured in the tissue by adding 100 µl of freshly reconstituted luciferase assay buffer to 20 µl of tissue lysate. Luciferase activity is expressed as relative light units (RLU) normalized for protein content measured by Bradford assay.

Splenocytes transfer

Whole splenocytes were obtained from NF-κB-Luc mice. Briefly, the spleen was removed, and single-cell suspensions were prepared. The spleen cells were washed twice in PBS, and red blood cells were lysed with an ammonium chloride and potassium solution. The viable washed cells were counted using Trypan-blue exclusion. Different numbers of whole splenocytes (5 × 106, 10 × 106, and 20 × 106) were injected intravenously into Rag2−/− mice on the day of cardiac transplantation followed by the detection of BLI and luciferase activity post-transplantation. In another group, mice were transferred with NF-κB-Luc spleen cells alone, and the luciferase activity was assessed. One month after adoptive cell transfer the cardiac allografts were transplanted, and the luciferase activity was re-assessed.

Statistics

The graft survival days were presented as mean survival time ± standard deviation (MST ± SD) and evaluated for statistical significance by ANOVA analysis (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA). P-value of < 0.05 or less was considered as significant.

RESULTS

BLI defines NF-κB activation in cardiac graft transplantation

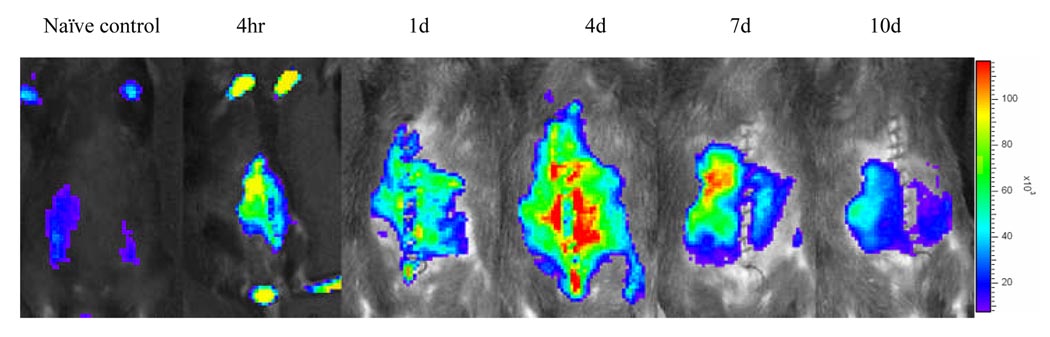

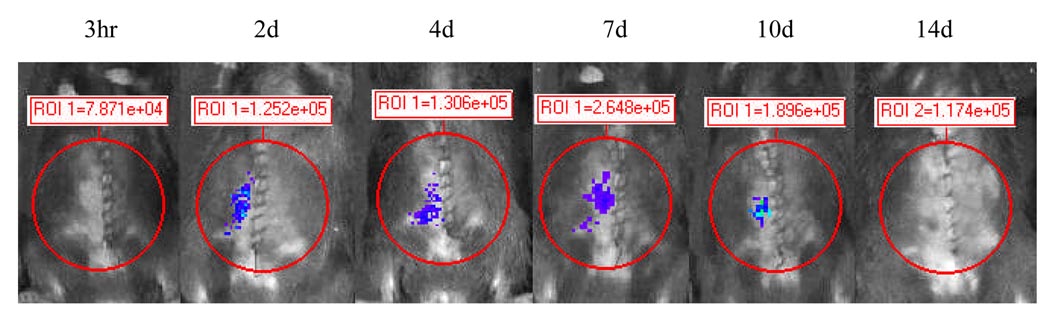

NF-κB-Luc C57BL/6 mice (female, 22 to 24 grams) were used as recipients of WT Balb/c cardiac allografts, and BLI was examined at the different timepoints post-transplantation. Increased luciferase activity was observed in the cardiac allografts at 4 hr following cardiac transplantation (Fig. 1a). The highest luciferase activity in the recipient abdomen was on day 4. Tissue luciferase activity was significantly increased in the cardiac allograft and surrounding lymph nodes (Fig. 1b). Next, NF-κB-Luc C57BL/6 mice were used as donors of the cardiac allografts that were transplanted into WT Balb/c mice. Figure 2 (upper panel) showed that luciferase activity was elevated in the NF-κB-Luc cardiac allografts up to 10 days. The results suggest that NF-κB activation is increased in the cardiac allografts when NF-κB-Luc mice used as either recipients or donors.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a BLI evaluates luciferase activity in NF-κB-Luc recipients engrafted with wild-type (WT) cardiac allografts.

NF-κB-Luc (C57BL/6) mice were used as recipients of WT Balb/c cardiac allografts. Luciferase activity was analyzed by BLI at 4hr, 1d, 4d, 7d, and 10 d post-transplantation after i.v. injection of luciferin (50mg/kg). Increased luciferase activity (or light emission expressed as Regions of Interest, ROI) was observed in the abdomen engrafted with cardiac allografts compared to the mouse without cardiac transplantation (naïve control).

Figure 1b Tissue luciferase activity in NF-κB-Luc recipients engrafted with WT cardiac allografts.

Cardiac graft, spleen, and drainage lymph nodes surrounding cardiac graft were collected at 7d after the completion of BLI. Tissue luciferase activity was performed as described in the Materials and Methods. Increased luciferase activity (referred as relative light units, RLU) was found in the cardiac allograft (X ± SE = 38,900 ± 8,909) and lymph nodes (X ± SE = 35,600 ± 6,654, n = 4) compared to that in the spleen (X ± SE = 9,998 ± 345, p < 0.05).

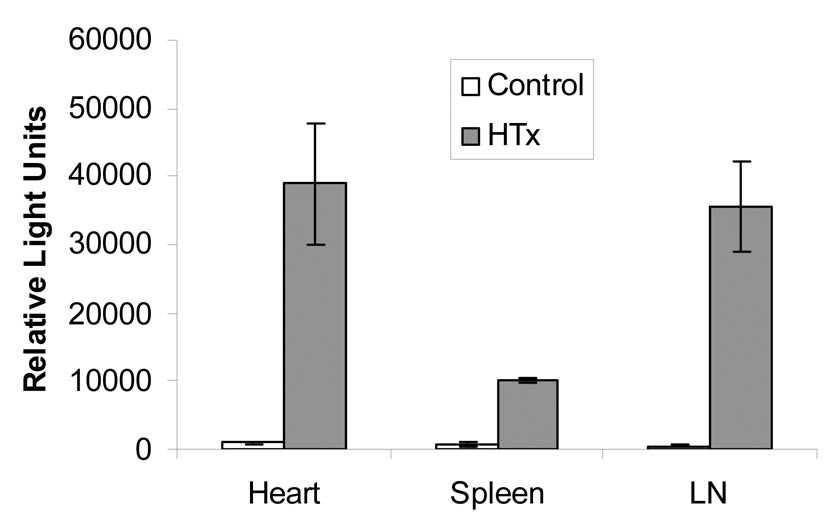

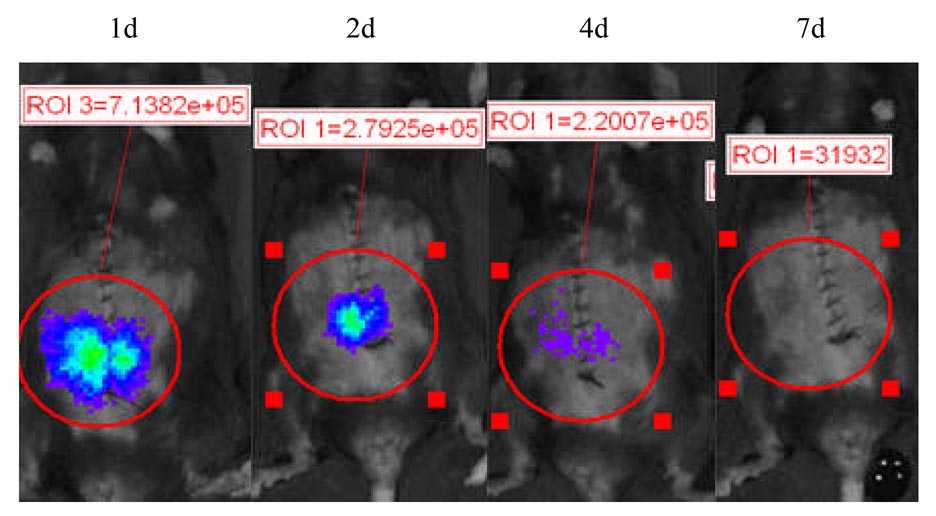

Figure 2. Luciferase activity was elevated after ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Syngeneic (Balb/c) NF-κB-Luc cardiac grafts with or without 16 hr preservation in UW solution were transplanted into WT Balb/c recipients, and luciferase activity was elevated after transplantation. The mean value of luciferase activity (X ± SE) was 2.48e+05 ± 5,850, 4.88e+05 ± 4,858, 3.65e+05 ± 7,125, 1.85e+05 ± 4,213, and 1.22e+05 ± 2,134 in the syngeneic cardiac grafts without ischemia-reperfusion injury (Syngeneic cardiac graft without IRI, n = 5) at 3 hr, 2 d, 4 d, 7d, and 10 d post-transplantation respectively. Compared to syngeneic cardiac grafts without IRI, luciferase activity in the syngeneic cardiac grafts with IRI (Syngeneic cardiac graft with IRI, n = 4) was 4.48e+05 ± 29,578, p<0.05; 2.85e+06 ± 54,867, p<0.05; 1.85e+06 ± 15,756, p<0.05; 2.05e+05 ± 5,831, p>0.05; and 1.55e+05 ± 4,428, p>0.05 at the same timepoint.

The role of NF-κB activation in the mediation of tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury has been documented (2, 8, 24). Figure 2 (lower panel) shows that luciferase activity in the preserved cardiac graft was significantly increased, compared to that in the cardiac grafts immediately transplanted into recipients with very short ischemic time (less than 30 minutes, Fig. 2, upper panel). The results suggest that cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury is associated with NF-κB activation that can be detected by BLI.

Either recipient- or donor-derived cells activate NF-κB signaling pathway

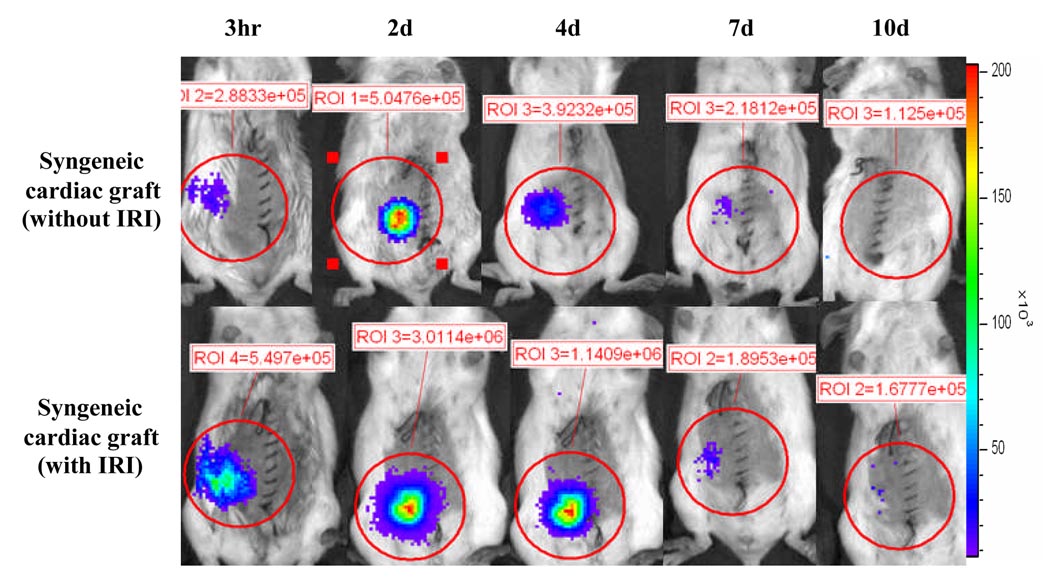

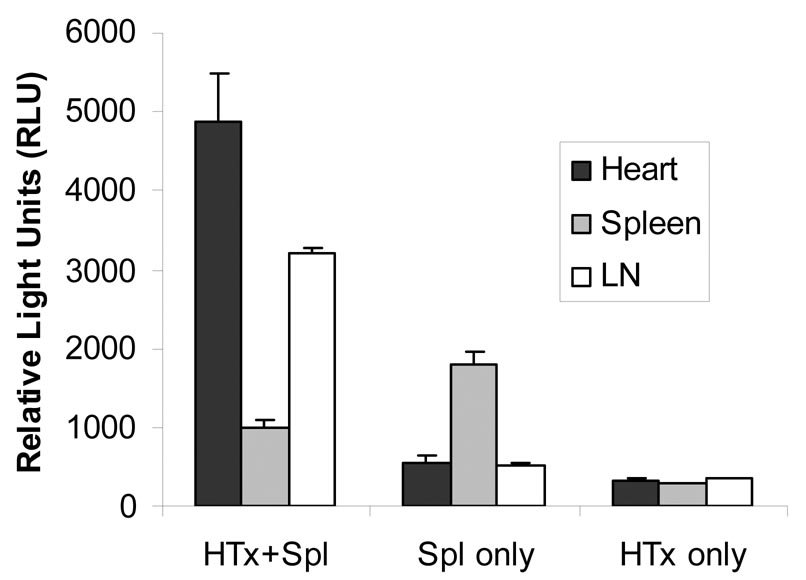

To define the specific role of NF-κB in the leukocyte compartment during allograft rejection, NF-κB-Luc (C57BL/6, 5 × 106, 10 × 106 and 20 × 106) whole splenocytes were adoptively transferred into Rag2−/− mice (C57BL/6) engrafted with WT Balb/c cardiac allografts on the day of transplantation. The results in Figure 3a show that Balb/c allografts were rejected in Rag2−/− mice transferred with different numbers of NF-κB-Luc (C57BL/6) spleen cells. Tissue luciferase activity in the cardiac grafts was elevated up to 10 days post-transplantation with the transfer of 10 × 106 NF-κB-Luc (C57BL/6) spleen cells (Fig. 3b). On day 7, the selected mice were sacrificed and cardiac grafts, spleen, and lymph nodes were collected for tissue luciferase activity. Tissue luciferase activity was observed in the cardiac grafts and the lymph nodes surrounding cardiac allograft (Fig. 3c, Spl+Heart). However, increased tissue luciferase activity in the spleen was observed in mice transferred with spleen cells without cardiac transplantation (Fig. 3c, Spl only).

Figure 3. Adoptive transfer of NF-κB-Luc spleen cells.

a) NF-κB-Luc (C57BL/6) spleen cells (20 × 106, 10 × 106, and 5 × 106) were transferred into Rag2−/− (C57BL/6) mice on the day of transplantation of WT Balb/c cardiac allografts. Allograft rejection was induced, and all cardiac allografts were rejected in a mean survival time (MST) of 9.8 days when transferred with 20 × 106 NF-κB-Luc spleen cells (MST ± SD = 9.8 ± 2.1d, n = 4), 17 days with 10 × 106 NF-κB-Luc spleen cells (MST ± SD = 14.5 ± 3.8d, n = 4), and 17.8 days with 5 × 106 NF-κB-Luc spleen cells (MST ± SD = 17.8 ± 5.1d, n = 4). b) Luciferase activity was elevated for up to 10 days after transfer of 20 ×106 NF-κB-Luc (C57BL/6) spleen cells. Although the cardiac allografts were rejected when transferred with NF-κB-Luc spleen cells less than 20 × 106 (Fig 3a), luciferase activity can be only detected at d 4 or d 7 (data not shown). c) Tissue luciferase activity was measured as described in the Materials and Methods. When cardiac transplantation, in combination with spleen cells, was performed, the highest luciferase activity was observed in the cardiac allograft and surrounding lymph nodes (Heart+Spl). NF-κB-Luc spleen cells migrate to the spleen in the absence of cardiac allograft (Spl only). No luciferase activity was observed in cardiac transplantation only (HTx only, n = 3 in each group). d) NF-κB-Luc (Balb/c) cardiac allografts were transplanted into Rag2−/− recipients (n = 5). Luciferase activity in the cardiac grafts was determined by BLI. The results show that luciferase activity was elevated up to 4 days post-transplantation and diminished by day 7 with the same dynamic change to that in syngeneic cardiac graft (Fig. 3a). The results suggest that donor-derived NF-κB activation is independent of recipient lymphocyte stimulation.

We hypothesize that NF-κB can be activated without recipient-derived lymphocyte activation since increased luciferase activity was observed in the syngeneic cardiac grafts. NF-κB-Luc (Balb/c) cardiac allografts were transplanted into T and B cell deficient Rag2−/− mice to define if donor-derived cells involve activation of NF-κB. As expected, an increased luciferase activity was observed in the NF-κB-Luc grafts, which was diminished by day 7 (Fig. 3d); thus, donor-derived cells are enough to drive NF-κB activation independent of recipient-derived T and B stimulator cells. The results suggest that either donor-or recipient-derived cells have the ability to activate NF-κB signal in response to variety of stimulations.

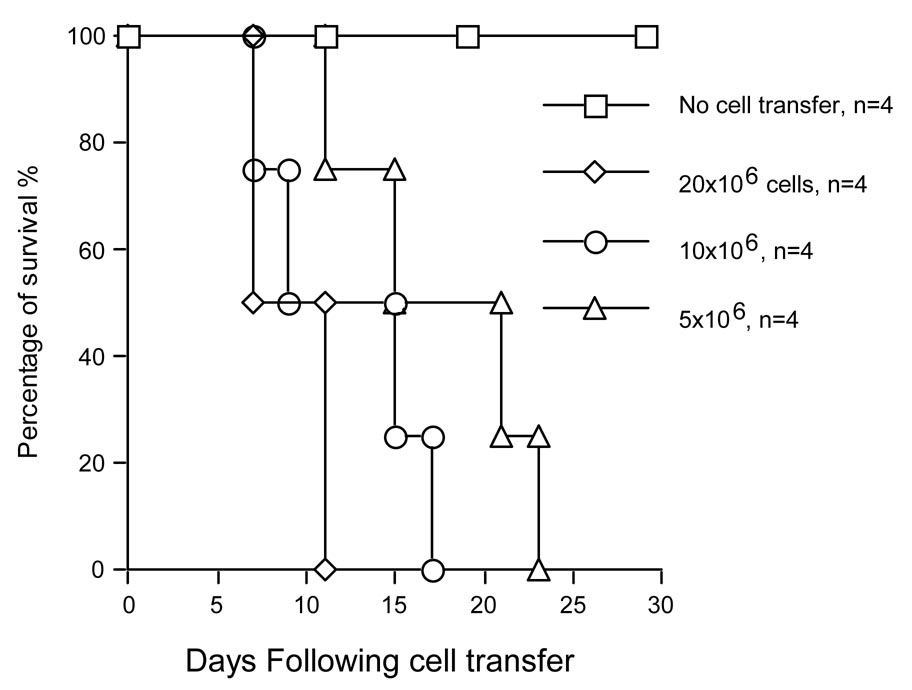

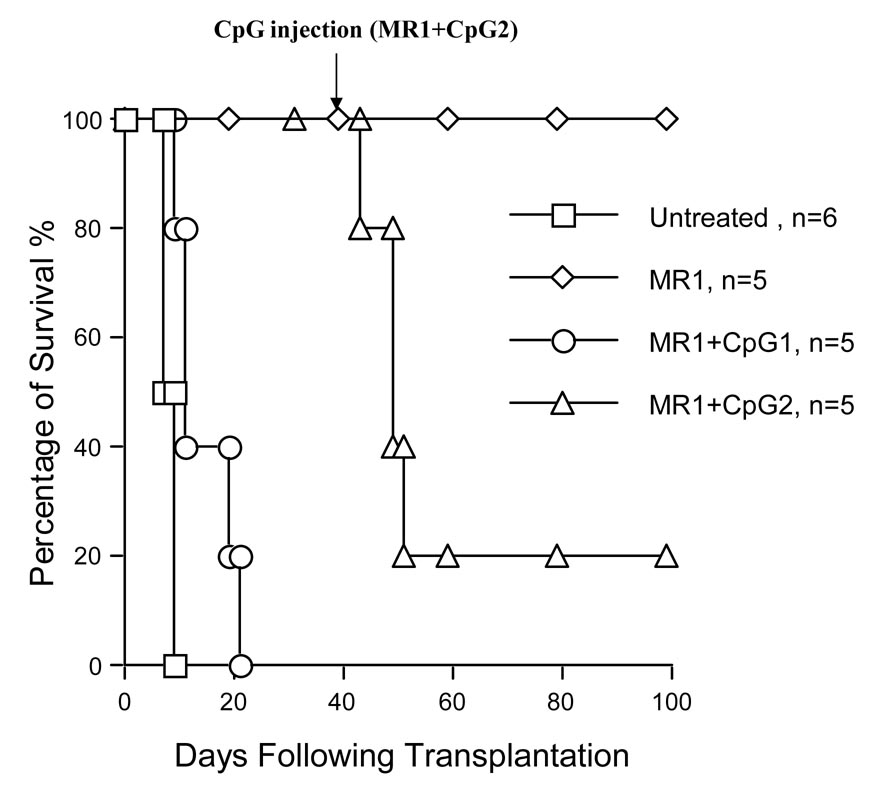

Anti-CD154 mAb therapy inhibits NF-κB activation which can be reversed by TLR engagement

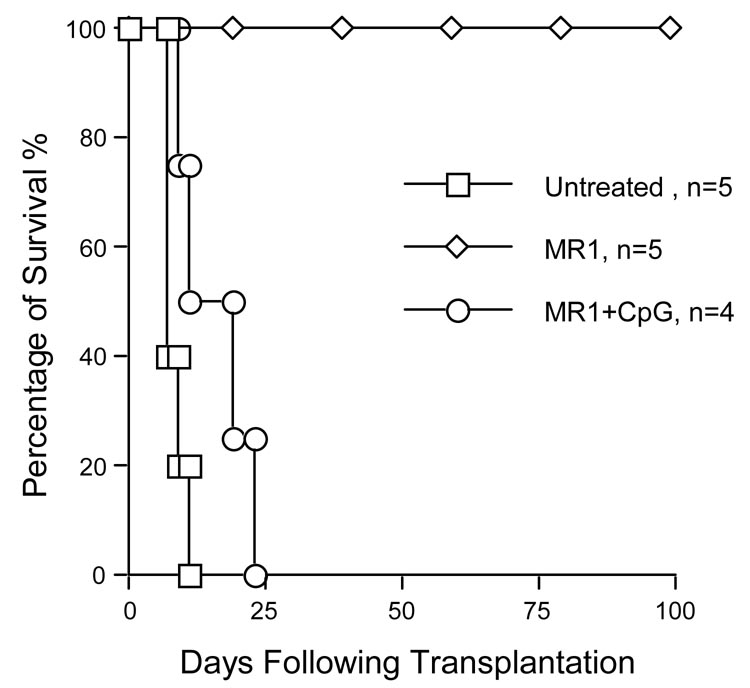

Previous reports have demonstrated that CD154 mAb therapy induces long-term survival of cardiac allograft and decreases mRNA levels of NF-κB and IκB genes (2, 20, 25, 26). TLR engagement with CpG DNA impaired tolerance induced by costimulatory blockade (7). In the current study, we analyzed the role of anti-CD154 mAb in the inhibition of NF-κB activation in a cardiac transplantation mouse model. WT cardiac allografts (C57BL/6) were transplanted into NF-κB-Luc (Balb/c) mice with or without anti-CD154 (MR1, 1mg per mouse × 3) treatment. The results in Figure 4a show that anti-CD154 mAb therapy induced long-term survival of cardiac allografts in NF-κB-Luc recipients. Administration of CpG DNA on day of transplantation (100µg per mouse × 3, i.p.) abrogated tolerance induced by CD154 blockade, and all cardiac grafts were rejected within 20 days (Fig.4a MR1 + CpG1). In addition, CpG DNA treatment starting at 30d post-transplantation can also elicit allograft rejection and reverse the inhibition of NF-κB activation by CD154 blockade (Fig.4a MR1 + CpG2).

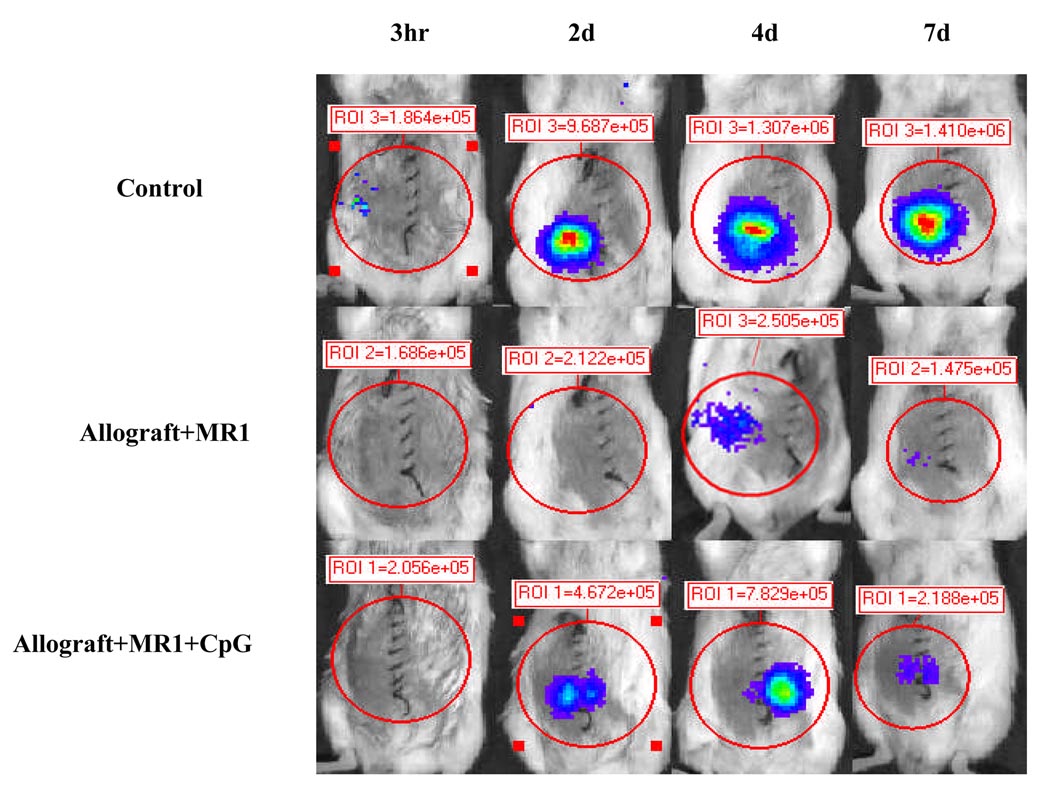

Figure 4. TLR engagement reverses CD154 mAb-induced tolerance and enhances NF-κB activation.

a) When NF-κB-Luc (Balb/c) mice were used as recipients of WT C57BL/6 cardiac allografts, the untreated cardiac allografts were rejected within 9 days (MST ± SD = 7.5 ± 0.5d, n = 6). In anti-CD154 mAb-treated mice (MR1, 1mg per mouse × 3), tolerance to cardiac allografts was induced (MST > 100d, n = 5); however, TLR engagement with TLR-9 ligand, CpG DNA (100µg/mouse × 3 at 0d, +1d, and +3d relative to transplantation), reverses tolerance induction (MR1+CpG1, MST ± SD = 14.5 ± 5.4d, n = 5). In addition, when the recipients were received CpG DNA injection (100 µg per mouse × 3) at day 30 following transplantation, tolerance was abrogated and 80% of cardiac allografts were rejected within 20 days after CpG DNA injection (MR1+CpG2, MST ± SD ≥ 18.8 ± 7.2d, n = 5). b) When NF-κB-Luc (C57BL/6) mice were used as donors of cardiac allografts, the untreated cardiac allografts were rejected within 9 days (MST ± SD = 7.6 ± 0.89d, n = 5). Anti-CD154 mAb therapy induced tolerance to cardiac allografts (MST > 100d, n = 5). TLR engagement with CpG DNA (100µg/mouse × 3 at 0d, +1d, and +3d relative to the transplantation) reverses tolerance induction (MR1+CpG, MST ± SD = 16.4 ± 3.85d, n = 4). c) We asked if donor-derived NF-κB signaling could be inhibited by anti-154 mAb and if CpG DNA can reverse this inhibition. NF-κB-Luc (C57BL/6) mice were used as donors of cardiac allografts treated with anti-CD154 mAb (MR1, 1mg per mouse × 3) and CpG DNA. Anti-CD154 mAb therapy inhibits luciferase activity in the cardiac allografts (middle panel, Allograft+MR1, n = 6), compared to control that received cardiac transplantation without any immunosuppressant (upper panel, Control). CpG DNA (100µg/mouse × 3) enhanced luciferase activity post-transplantation (lower panel, Allograft+MR1+CpG, n =4).

To determine if anti-CD154 mAb can inhibit NF-κB activation in donor-derived cell, NF-κB-Luc (C57BL/6) cardiac allografts were transplanted into WT Balb/c mice. The results in Figure 4b show that anti-CD154 mAb induced long-term survival of cardiac allografts and inhibited luciferase activity; and additional CpG DNA elicited an elevation of luciferase activity in anti-CD154 mAb treated cardiac allografts (Fig. 4b and c). The data indicate that NF-κB-Luc mice, when used as donors or recipients of cardiac allografts, have the same biological characterization with WT combination (19). Anti-CD154 mAb therapy can inhibit both recipient cell- and donor cell-derived NF-κB activation, which can be reversed by TLR engagement.

DISCUSSION

NF-κB is a rapid response transcription factor for genes whose products are critical for inflammatory reaction and alloimmune response (1, 27). The availability of genetically modified transgenic NF-κB-Luc mice provides a useful reporter-based assay system in which to analyze NF-κB enhancer activity in response to a variety of inflammatory signals. Since luciferase production is under the control of NF-κB promoter, NF-κB activation is required for transcriptional activity of luciferase and luciferase activity represents the activation of NF-κB. The current results suggest that luciferase activity can be detected in the cardiac grafts when NF-κB-Luc mice are used as recipients. To characterize if donor-derived passenger leukocytes are involved in the NF-κB activation, NF-κB-Luc mice were used as donors of the cardiac allografts. The results show that luciferase activity is elevated in the cardiac allografts up to 10 days and the cardiac allografts are rejected within 7 – 10 days. Our observation of a significant increase of luciferase activity in the cardiac allografts is consistent with previous report by Tanaka (23), in which BLI visualized migration and proliferation of passenger leukocytes in both syngeneic and allogeneic recipients. The current results suggest that recipient-derived lymphocytes and donor-derived passenger cells have the ability to activate NF-κB.

A growing body of the literature suggests that tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury activates TLR/NF-κB signaling pathway (13, 28, 29). Here, we report that long-term ischemia reperfusion (16 hr) of cardiac grafts will lead to significant increase of luciferase activity that is elevated up to 10 days. In the syngeneic cardiac grafts immediately transplanted into recipients with very short ischemic time, temporary increase of luciferase activity is observed that diminished within 4 days. The results indicate that antigen-independent insults, such as tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury, can stimulate the innate immune response and elicit NF-κB activation, and the visualization of NF-κB activation by BLI is a useful approach to analyze, in vivo, tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury.

To define the source of cells involved in NF-κB activation, NF-κB-Luc spleen cells are adoptively transferred into Rag2−/− mice on the day of cardiac allograft transplantation. NF-κB-Luc spleen cells lodge in the cardiac allograft and the lymph nodes surrounding cardiac allograft. In the absence of cardiac allograft, these cells migrate to the other parts of the body, such as the feet, the tail, and the native spleen. To further confirm allograft-mediated activation of NF-κB, the cardiac allografts are transplanted back to Rag2−/− mice transferred with NF-κB-Luc spleen cells alone two weeks later. As expected, luciferase activity in the cardiac allografts recurs by day 7 post-transplantation. The results indicate that NF-κB-Luc spleen cells are recruited into the area where alloimmune response occurs resulting in NF-κB activation.

We hypothesized that NF-κB can be activated in the absence of recipient lymphocytes since luciferase activity is transiently increased in syngeneic cardiac grafts (NF-κB-Luc Balb/c to WT Balb/c). A previous study has shown that cardiac grafts survive in T and B cell deficient Rag2−/− mice indefinitely without any immunosuppressant (30). The current results suggest that luciferase activity in cardiac grafts is observed at 3 hr and maintains for up to 4 days in Rag2−/− mice, suggesting that NF-κB can be activated independent of recipient-derived T or B cell stimulation.

Anti-CD154 mAb therapy has been demonstrated to induce donor specific tolerance (19, 31). Previous reports indicate that anti-CD154 mAb decreases mRNA level of NF-κB (2, 32). Our results show that anti-CD154 mAb reduces NF-κB activation and induces tolerance to cardiac allograft evidenced by decreased luciferase activity when NF-κB-Luc mice were used as recipients of cardiac allografts. The inhibition of NF-κB activation occurs after 2 days of cardiac transplantation. Our previous results suggest that tolerance induced by anti-CD154 mAb therapy can be abrogated by additional TLR-9 ligand, CpG DNA (7). Indeed, the current data show that tolerance cannot be induced by anti-CD154 mAb when administration of CpG DNA is on the day of transplantation. CpG DNA can also abrogate tolerance induced by anti-CD154 mAb 30 days after transplantation and enhance NF-κB activation.

We observed that anti-CD154 mAb therapy has the ability to inhibit not only recipient cell-derived but also donor cell-derived NF-κB activation. NF-κB activation is diminished in NF-κB-Luc cardiac allografts when transplanted into WT mice treated by anti-CD154 mAb and this inhibition is reversed by TLR engagement. The current results collectively suggest that TLR engagement with CpG DNA abrogates anti-CD154 mAb-induced tolerance and restores the NF-κB signaling pathway.

In conclusion, our model provides a useful approach to visualize NF-κB activation non-invasively and quantitatively from passenger leukocytes and recipient lymphocytes in a cardiac transplantation mouse model. NF-κB is activated in allograft rejection and tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury. TLR engagement prevents anti-CD154 therapy-mediated tolerance induction through activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation (1-2005-77 to DPY). We thank Janene Pierce for helpful proofreading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee JI, Burckart GJ. Nuclear factor kappa B: important transcription factor and therapeutic target. J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;38(11):981. doi: 10.1177/009127009803801101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Csizmadia V, Gao W, Hancock SA, et al. Differential NF-kappaB and IkappaB gene expression during development of cardiac allograft rejection versus CD154 monoclonal antibody-induced tolerance. Transplantation. 2001;71(7):835. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200104150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sadikot RT, Blackwell TS. Bioluminescence imaging. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2(6):537. doi: 10.1513/pats.200507-067DS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yull FE, Han W, Jansen ED, et al. Bioluminescent detection of endotoxin effects on HIV-1 LTR-driven transcription in vivo. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51(6):741. doi: 10.1177/002215540305100605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roth DJ, Jansen ED, Powers AC, Wang TG. A novel method of monitoring response to islet transplantation: bioluminescent imaging of an NF-kB transgenic mouse model. Transplantation. 2006;81(8):1185. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000203808.84963.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen X, Zhang X, Larson CS, Baker MS, Kaufman DB. In vivo bioluminescence imaging of transplanted islets and early detection of graft rejection. Transplantation. 2006;81(10):1421. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000206109.71181.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L, Wang T, Zhou P, et al. TLR engagement prevents transplantation tolerance. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(10):2282. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsung A, Hoffman RA, Izuishi K, et al. Hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury involves functional TLR4 signaling in nonparenchymal cells. J Immunol. 2005;175(11):7661. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thornley TB, Brehm MA, Markees TG, et al. TLR agonists abrogate costimulation blockade-induced prolongation of skin allografts. J Immunol. 2006;176(3):1561. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou P, Hwang KW, Palucki DA, et al. Impaired NF-kappaB activation in T cells permits tolerance to primary heart allografts and to secondary donor skin grafts. Am J Transplant. 2003;3(2):139. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ueki S, Yamashita K, Aoyagi T, et al. Control of allograft rejection by applying a novel nuclear factor-kappaB inhibitor, dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin. Transplantation. 2006;82(12):1720. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000250548.13063.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaibori M, Sakitani K, Oda M, et al. Immunosuppressant FK506 inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression at a step of NF-kappaB activation in rat hepatocytes. J Hepatol. 1999;30(6):1138. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80270-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen XD, Ke B, Zhai Y, et al. Toll-like receptor and heme oxygenase-1 signaling in hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(8):1793. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lentsch AB. Activation and function of hepatocyte NF-kappaB in postischemic liver injury. Hepatology. 2005;42(1):216. doi: 10.1002/hep.20779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frantz S, Tillmanns J, Kuhlencordt PJ, et al. Tissue-Specific Effects of the Nuclear Factor {kappa}B Subunit p50 on Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Am J Pathol. 2007 doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blackwell JM, Searle S. Genetic regulation of macrophage activation: understanding the function of Nramp1 (=Ity/Lsh/Bcg) Immunol Lett. 1999;65(1–2):73. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(98)00127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blackwell TS, Yull FE, Chen CL, et al. Multiorgan nuclear factor kappa B activation in a transgenic mouse model of systemic inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(3 Pt 1):1095. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9906129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corry RJ, Winn HJ, Russell PS. Primarily vascularized allografts of hearts in mice. The role of H-2D, H-2K, and non-H-2 antigens in rejection. Transplantation. 1973;16(4):343. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197310000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin D, Dujovny N, Ma L, et al. IFN-gamma production is specifically regulated by IL-10 in mice made tolerant with anti-CD40 ligand antibody and intact active bone. J Immunol. 2003;170(2):853. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.2.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yin D, Ma L, Zeng H, Shen J, Chong AS. Allograft tolerance induced by intact active bone co-transplantation and anti-CD40L monoclonal antibody therapy. Transplantation. 2002;74(3):345. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200208150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen J, Chong AS, Xiao F, et al. Histological characterization and pharmacological control of chronic rejection in xenogeneic and allogeneic heart transplantation. Transplantation. 1998;66(6):692. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199809270-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Everhart MB, Han W, Sherrill TP, et al. Duration and intensity of NF-kappaB activity determine the severity of endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. J Immunol. 2006;176(8):4995. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka M, Swijnenburg RJ, Gunawan F, et al. In vivo visualization of cardiac allograft rejection and trafficking passenger leukocytes using bioluminescence imaging. Circulation. 2005;112(9 Suppl):I105. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.524777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takahashi Y, Ganster RW, Gambotto A, et al. Role of NF-kappaB on liver cold ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283(5):G1175. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00515.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larsen CP, Alexander DZ, Hollenbaugh D, et al. CD40-gp39 interactions play a critical role during allograft rejection. Suppression of allograft rejection by blockade of the CD40-gp39 pathway. Transplantation. 1996;61(1):4. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199601150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niimi M, Pearson TC, Larsen CP, et al. The role of the CD40 pathway in alloantigen-induced hyporesponsiveness in vivo. J Immunol. 1998;161(10):5331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper M, Lindholm P, Pieper G, et al. Myocardial nuclear factor-kappaB activity and nitric oxide production in rejecting cardiac allografts. Transplantation. 1998;66(7):838. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199810150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyd JH, Mathur S, Wang Y, Bateman RM, Walley KR. Toll-like receptor stimulation in cardiomyoctes decreases contractility and initiates an NF-kappaB dependent inflammatory response. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;72(3):384. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrade CF, Kaneda H, Der S, et al. Toll-like receptor and cytokine gene expression in the early phase of human lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25(11):1317. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krieger NR, Yin DP, Fathman CG. CD4+ but not CD8+ cells are essential for allorejection. J Exp Med. 1996;184(5):2013. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phillips NE, Markees TG, Mordes JP, Greiner DL, Rossini AA. Blockade of CD40-mediated signaling is sufficient for inducing islet but not skin transplantation tolerance. J Immunol. 2003;170(6):3015. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smiley ST, Csizmadia V, Gao W, Turka LA, Hancock WW. Differential effects of cyclosporine A, methylprednisolone, mycophenolate, and rapamycin on CD154 induction and requirement for NFkappaB: implications for tolerance induction. Transplantation. 2000;70(3):415. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200008150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]