Abstract

Protein engineering strategies have proven valuable for the production of a variety of well-defined macromolecular materials with controlled properties that have enabled their use in a range of materials and biological applications. In this work, such biosynthetic strategies have been employed in the production of monodisperse alanine-rich, helical protein polymers with the sequences [AAAQEAAAAQAAAQAEAAQAAQ]3 and [AAAQAAQAQAAAEAAAQAAQAQ]6. The composition of these protein polymers is similar to that of a previously reported family of alanine-rich protein polymers, but the density and placement of chemically reactive residues has been varied to facilitate the future use of these macromolecules in elucidating polymeric structure-function relationships in biological recognition events. Both protein polymers are readily expressed from E. coli and purified to homogeneity; characterization of their conformational behavior via circular dichroic spectroscopy (CD) indicates that they adopt highly helical conformations under a range of solution conditions. Differential scanning calorimetry, in concert with CD, demonstrates that the conformational transition from helix to coil in these macromolecules can be well-defined, with helicity, conformational transitions, Tm values, and calorimetric enthalpies that vary with the molecular weight of the protein polymers. A combination of infrared spectroscopy and CD also reveals that the macromolecules can adopt β-sheet structures at elevated temperatures and concentrations and that the existence and kinetics of this conformational transition appear to be related to the density of charged groups on the protein polymer.

Introduction

The use of biologically directed methods of synthesis has become a common tool for the production of macromolecules with well-defined molecular weights and sequences. The control over molecular weight allows the synthesis of monodisperse protein polymers that can display interesting liquid crystalline behaviors such as those seen in poly(benzyl-α-L-glutamates).1 The sequence control of biologically directed methods offers control over the placement of specific side groups displayed by amino acids as secondary structure can be intrinsically defined by the sequence of the protein polymer. Mimics of naturally occurring proteins including silk,2-6 elastin,7 and collagen6 have been synthesized via biological methods in order to take advantage of the excellent mechanical and biological properties of the natural proteins. For example, numerous studies of polypeptides based on silk protein sequences have been conducted in order to gain insight into the effect of secondary structure on the unmatched mechanical properties of various silks.3-8

The structure control gained from biologically directed methods of synthesis facilitates the production of artificial protein polymers with desired structure and properties for biomaterials applications. The biological synthesis of functional α-helical polypeptides and proteins offers the unique opportunity to investigate the importance of structure and functional group placement in the mediation of biological processes by biosynthetic macromolecules. In particular, the α-helix is a prominent motif in controlling protein assembly and the presentation of functional groups in natural proteins such as involucrin9 and the antifreeze proteins.10,11 The formation of the corneocyte protein envelope in the epidermis is suggested to be controlled by the folding of the protein innvolucrin into an appropriate helical conformation,9 and alanine-rich, α-helical, type I antifreeze proteins inhibit ice crystal growth in arctic fish through the controlled presentation of hydroxyl groups.10,11 Genetically synthesized functional α-helical polypeptides, however, have not been widely studied outside of investigations employing coiled-coil motifs,12-19 although there have been recent studies that exploit the display of functional groups along an alanine-rich α-helical backbone for applications in electrostatic assembly of nanostructured materials and in the manipulation of multivalent binding events.20-22

Numerous reports have explored synthetic polyalanine sequences as a model for the folding of the α-helix, as polyalanine has a high propensity for helicity and there are no side-chain stabilization effects to complicate determinations of helical propensity. Accordingly, fundamental studies of a large variety of alanine-rich peptides have shown these sequences convert from α-helical to random coil conformations with increasing temperature, and the fractional helicity and stability increase with peptide length.23,24 The conformational transitions of alanine-rich peptides have also been investigated in conjunction with understanding neurodegenerative disorders in which peptides undergo a conversion from cellular-allowed conformations (helix and random coil) to a β-sheet conformation.25 Specifically, certain alanine-rich peptides and proteins display α-helix, random coil, and β-sheet conformations depending on solution conditions26-28 and convert from an α-helix to a β-sheet structure when incubated at elevated temperatures.21,25 The determinants controlling such conformational behavior are of continued interest as they can relate to pathological conditions in vivo. Therefore, the synthesis of alanine-rich protein polymers via biological methods offers opportunities in a variety of applications including those in which control of functional group placement is important as well as those aimed at elucidating the structural determinants of protein aggregation processes.

We have previously reported the synthesis and characterization of a family of alanine-rich helical protein polymers of the general sequence [(AAAQ)y(AAAE)(AAAQ)y]x, which were synthesized via protein engineering strategies.21 Protein polymers from this family were shown to be highly α-helical at low temperatures and maintain that helicity under physiological temperatures and salt concentrations. These protein polymers also displayed an irreversible transition to β-sheet at temperatures above 55 °C. Here we report the biosynthesis and characterization of two additional alanine-rich helical protein polymer families, [AAAQEAAAAQAAAQAEAAQAAQ]x and [AAAQAAQAQAAAEAAAQAAQAQ]x, which possess very similar amino acid compositions to that of [(AAAQ)y(AAAE)-(AAAQ)y]x and should therefore exhibit similarly useful conformational properties. The sequences maintain a ratio of alanine (A) to glutamine residues (Q) of approximately 3:1. Alanine and glutamine both provide a high tendency for helix formation; the inclusion of the polar Q residues may minimize aggregation and increase solubility, as has been reported previously for alanine-rich peptides.29-31 The number of glutamic acid residues is manipulated via variations in the x value, while sequence differences permit variation in the glutamic acid density. Alterations in these sequences relative to the previously reported protein polymer have been made in order to control the density of the glutamic acid residues (E) along the helical backbone. These sequences, therefore, offer multiple families of protein polymers with desired conformational properties and varied densities of chemically reactive groups for future uses in the presentation of biologically active ligands and/or mediation of materials assembly. In this work, we report the design, synthesis, and characterization of the conformational properties of protein polymers with the specific sequences [AAAQEAAAAQAAAQAEAAQAAQ]3 (A3) and [AAAQAAQAQAAAEAAAQAAQAQ]6 (B6).

Materials and Methods

Materials

A mutagenized version of the pET-19b plasmid (altered via site-directed mutagenesis to eliminate a Sap I site32) was a gift of N. L. Goeden-Wood and J. D. Keasling. The expression plasmid pET-28b was obtained from EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA). The restriction endonuclease Eam1104 I was obtained from MBI Fermentas (Hanover, MD), while all other restriction endonucleases were obtained from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA) or Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Synthetic oligonucleotides were obtained from Sigma Genosys (The Woodlands, TX). Oligonucleotide and plasmid purification kits and nickel-chelated sepharose resin were obtained from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). General reagents for protein expression and purification were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) and Fisher Scientific (Fairlawn, NJ).

DNA Monomer and Cloning Plasmid Construction

All molecular biology procedures were conducted according to standard protocols33 and are not described in detail here. Two DNA sequences were designed to encode the amino acid sequences [AAAQEAAAAQAAAQAEAAQAAQ] and [AAAQAAQAQAAAEAAAQAAQAQ]. These DNA sequences were flanked by type IIS restriction enzyme recognition sites Bsa I and Eam1104 I, respectively (Figure 1a,b), to permit the removal of the monomer DNA sequence from a cloning plasmid. The use of the two different restriction enzymes in the design of these constructs resulted from difficulties encountered in the initial cloning of the [AAAQEAAAAQAAAQAEAAQAAQ] sequences with the Eam1104 I restriction enzyme. The Bsa I was therefore employed to provide a five base pair overhang, which improved the ligation of the sequences into the expression plasmid (see below). The additional alanine residue encoded at the end of both monomer sequences is included in order to maintain the continuity of the desired sequence upon multimerization after digestion with the type IIs restriction enzymes. The type IIS restriction sites were also flanked by EcoR I and BamH I restriction sites for efficient cloning of the oligonucleotide into the cloning plasmid pUC19. The protocols described in a previous paper21 were followed for ligation of the oligonucleotides encoding the monomer sequences and flanking restriction sites into the recipient cloning vector, pUC19. The plasmids containing the appropriate DNA sequences for [AAAQEAAAAQAAAQAEAAQAAQ] and [AAAQAAQAQAAAEAAAQAAQAQ] were identified via sequencing analysis and designated as pUC19-A and pUC19-KLK-B.

Figure 1.

DNA sequence of inserts used in plasmid construction. (a) Oligonucleotide sequence inserted into the cloning vector, pUC19, to yield pUC19-A. (b) Oligonucleotide sequence inserted into the cloning vector, pUC19, to yield pUC19-KLK-B. (c) Oligonucleotide sequence inserted into the expression vector pET28b to yield pET28b-JS1. (d) Oligonucleotide sequence inserted into the expression vector pET19b to yield pET19b-RF1. The double line in the sequences of (c) and (d) indicate extraneous bases inserted to increase the length of the DNA segment removed from pET28b and pET19b upon digestion with Bsa I or Sap I restriction enzymes, respectively.

Expression Plasmid Construction

The multiple cloning sites of two expression plasmids, pET28b and a mutagenized pET-19b,32 were modified by the insertion of an oligonucleotide linker. The linker designed for the pET28b plasmid (Figure 1c) contains terminal Nco I and BamH I restriction sites for insertion into the plasmid, and two internal Bsa I restriction sites allow for insertion of the oligonucleotide encoding the target protein polymer, [AAAQEAAAAQAAAQAEAAQAAQ]. A DNA linker inserted into the mutagenized pET-19b (Figure 1d) was also designed to contain terminal Nco I and BamH I restriction sites but contains two internal Sap I restriction sites, rather than Bsa I sites, which permit insertion of the oligonucleotide which encodes the protein polymer sequence [AAAQAAQAQAAAEAAAQAAQAQ]. Both DNA linkers were designed to encode N-terminal decahistidine fusion tags (Figure 1c,d), which permit protein polymer purification via metal chelate affinity chromatography. The DNA sequences encoding these linker sequences were annealed and ligated into their respective plasmids, as described previously.21 Plasmid DNA containing the correct Bsa I linker DNA sequence was designated as pET28b-JS1, and plasmid DNA containing the correct Sap I linker DNA sequence was designated as pET19b-RF1. Two different expression plasmids were selected for the insertion of the oligonucleotide linkers to ensure that the Bsa I and Sap I restriction sites in the linker sequence were the only such restriction sites and would therefore permit ligation of the genes encoding the target polypeptides in the appropriate region of the expression plasmid.

To isolate the oligonucleotide sequence for insertion into the expression plasmids, the plasmid pUC19-A was digested with the restriction enzyme Bsa I (50 °C, 4 h), and the DNA fragment corresponding to the target protein polymer (66 bp) was isolated via agarose gel electrophoresis. The purified monomer DNA was then ligated via treatment with T4 DNA ligase into the pET28b-JS1 plasmid that had been previously digested with Bsa I (50 °C, 4 h), dephosphorylated via treatment with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP), and purified. The production of expression plasmids carrying artificial repetitive genes of varying lengths was confirmed via restriction digest analysis of the plasmids with the enzymes BamH I and Nco I (37 °C, 1 h) and subsequent analysis via agarose gel electrophoresis. The isolation of the target DNA sequence, [AAAQAAQAQAAAEAAAQAAQAQ], from pUC19-KLK-B was performed via digestion of the cloning plasmid with Eam1104 I (37 °C, 16 h) and subsequent isolation via agarose gel electrophoresis. The pET19b-RF1 plasmid was digested with Sap I (37 °C, 16 h) to allow for the insertion of the purified DNA fragment, which was verified via restriction digest analysis. All gene sequences were confirmed via dideoxy sequencing analysis. The plasmids containing the target DNA sequences were designated as pET28b-JS1-AX (where X denotes the number of [AAAQEAAAAQAAAQAEAAQAAQ] repeats) or pET19b-RF1-BX (where X denotes the number of [AAAQAAQAQAAAEAAAQAAQAQ] repeats).

Protein Expression and Purification

The plasmids pET28b-JS1-A3 and pET19b-RF1-B6 were used to transform chemically competent cells of E. coli strain BL21(DE3)pLysS. Table 1 lists the protein polymer sequences expressed with their respective abbreviations and expected molecular weights.

Table 1.

Sequence, Molecular Weight, and Nominal Distance between Glutamic Acid Residues for Each of the Sequences Studied

| sequence | MW (Da) | approx spacing (Å) | no. of A | no. of Q | no. of E | A:Q | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A3 | [AAAQEAAAAQAAAQAEAAQAAQ]3 | 8875 | 17 | 45 | 15 | 6 | 3:1 |

| B6 | [AAAQAAQAQAAAEAAAQAAQAQ]6 | 14159 | 35 | 90 | 36 | 6 | 2.5:1 |

| C2a | [(AAAQ)5(AAAE)(AAAQ)5]2 | 9889 | 65 | 66 | 20 | 2 | 3.3:1 |

Previously reported.21 Included for comparison purposes.

Protein expression of A3 and B6 was conducted via standard methods employing chemical induction (isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside, IPTG, final concentration 0.4 mM) of cultures of the expression hosts (500 mL) supplemented with appropriate antibiotics (kanamycin (35 μg/mL) and chloramphenicol (35 μg/mL) for pET28b-JS1-A3; ampicillin (200 μg/mL) and chloramphenicol (35 μg/mL) for pET19b-RF1-B6). Cells were harvested 4 h after induction via centrifugation (6000 rpm, 10 min), the supernatant was decanted, and the cell pellets were resuspended in 8 M urea at pH 8.0 (1 g cell/ 4 mL buffer) and frozen at -20 °C. Protein expression was monitored via sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) of samples with normalized OD600 and visualized via Coomassie blue staining.

The target protein polymer was purified from the cell lysate via immobilized metal chelate affinity chromatography with stepwise pH gradient elution under denaturing conditions (Qiagen). Eluted protein polymer was dialyzed batchwise against distilled water at 4 °C for 5 days. The dialysate was lyophilized to yield 15-20 mg of the purified target protein polymer per liter of culture. The purity of the polypeptides was monitored via SDS-PAGE and confirmed via reverse-phase HPLC and amino acid analysis. The molecular weight of the purified polypeptide was confirmed via MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, the conformational properties of the protein polymers were characterized via circular dichroic spectroscopy, and thermally induced conformational changes were monitored via differential scanning calorimetry.

General Characterization

DNA sequencing of plasmids was performed by the College of Agriculture sequencing facility at the University of Delaware. Analysis of the amino acid composition of purified protein polymer was performed by the Molecular Analysis Facility at the University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA).

MALDI-TOF

MALDI-TOF analysis of purified protein polymer was performed at the Mass Spectrometry Facility in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at the University of Delaware on a Biflex III (Bruker, Billerica, MA). The samples were prepared in a 3,5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix with the calibration mixture of bovine insulin (MW = 5734.59), thioredoxin from E. coli (MW = 11 647.48), and horse apomyoglobin (MW = 16 952.56). Data were recorded using the Omni-FLEX program and subsequently analyzed in the XmassOmni program.

Circular Dichroic Spectroscopy

Circular dichroic spectra were recorded on an AVIV 215 spectrophotometer (Proterion Corp., Piscataway, NJ) or a Jasco J-810 spectrophotometer (Easton, MD) in a 1 mm path length quartz cuvette in the single-cell mount setup. Background scans of buffers (pH 2.3, 10 mM phosphate; pH 2.3, 10 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl) were recorded and manually subtracted from the sample spectra. Samples of A3 were made at a concentration of approximately 25-30 μM via dilution of a 113 μM stock solution of protein polymer in pH 2.3, 10 mM phosphate, while samples of B6 were made at a concentration of approximately 10-20 μM upon dilution of a 70 μM stock solution. Protein polymer concentrations were confirmed via quantitative amino acid analysis employing an internal standard, norvaline. Data points for the wavelength-dependent CD spectra were recorded at every nanometer, with a 1 nm bandwidth and a 5 s averaging time for each data point. Data points for the kinetic scans were recorded at 222 nm at 1 min intervals. The mean residue ellipticity, [θ]MRW (deg cm2 dmol-1), was calculated using the molecular weight of the protein polymer and cell path length.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry

Calorimetric experiments were performed on a Microcal VP-DSC (Northhampton, MA), equipped with sample cells with a volume of ~0.5 mL. Initially, both cells were filled with buffer (pH 2.3, 10 mM phosphate or pH 2.3, 10 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl) to determine the background, which was manually subtracted from data. Samples of A3 (113 μM) and B6 (70 μM) were heated at a constant rate of 1 °C/min and cooled at the machine-determined rate of ~6 °C/min. The raw data, in the form of heat flow (mcal/min), were converted to excess heat capacity, Cexp, using eq 1,

| (1) |

where q is the heat flow after background subtraction (mcal/min), M is the protein polymer molecular weight (g/mol), R is the heating rate (°C/min), c is the protein polymer concentration (g/mL), and V is the volume of the sample cell (mL). The Cexp curve was then integrated over the entire temperature range to yield the calorimetric enthalpy change, ΔHcal.

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

Infrared spectroscopic experiments were performed using a Nexus 670 FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Nicolet, Madison, WI) with unpolarized light and a MCT detector. Spectra taken at a resolution of 4 cm-1 from 400 to 4000 cm-1 were obtained by signal averaging 1000 scans. Samples were loaded into a liquid cell with a 15 μm Teflon spacer and quartz windows. Samples were prepared by the dissolution of A3 and B6 in pH 2.3, 10 mM phosphate buffer in D2O at concentrations of 100 and 400 μM. A background of pH 2.3, 10 mM phosphate buffer in D2O was subtracted from all sample spectra. The amide I region (1550-1750 cm-1) was deconvoluted into Gaussian peaks using the multiple-peak fitting function in Origin Data Analysis software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). Three peaks were employed for fitting the data, which was determined to be the optimal number of peaks for the fit based on assessment of χ2 and R2 values. Reported peak positions were calculated by the fitting procedure.

Results and Discussion

We have designed alanine-rich helical artificial protein polymers for the display of chemically reactive functional groups at varying densities in order to probe polymeric structure-function relationships and ultimately to produce functional polymeric architectures via elaboration of the chemically reactive groups. We have employed alanine (A), as it is a well-studied helix former, and glutamine (Q) to improve protein polymer solubility in aqueous solution. The specific number and position of glutamines in the sequences was chosen on the basis of energy minimization calculations in order to reduce the exposure of alanine-rich faces. Synthetic genes encoding the protein polymer sequences A3 and B6 were designed to place glutamic acid residues (E) at nominal distances of 17 and 35 Å, respectively (as determined via energy minimization calculations),21 along a chemically neutral backbone. A trimer of the A sequence and a hexamer of B sequence, although differing in molecular weight (Table 1), were used to maintain a constant number of chemically reactive glutamic acid residues (6) for subsequent investigations of structure-function relationships in the mediation of biological binding events. In the A3 and B6 sequences, more polar glutamine residues were regularly placed in order to minimize the length of alanine-rich regions. As in our previous investigations, the sequences reported here do not carry helix caps, salt bridges between residues at i and i + 4 positions,31,34-38 or coiled-coil domains,39-44 as these strategies introduce side chains that add undesirable chemical functionality for the ultimate uses of the protein polymers. Similarly, the choice of protein polymers functionalized with glutamic acid was motivated by their more facile protein expression and purification relative to the biosynthesis of highly cationic and thiolated protein polymers. The carboxylic acid side chain of E provides sites for chemical attachment of desired biologically or otherwise active moieties at a regular density in the sequence, and the presence of Q-E side chain interactions at the (i, i + 4) positions may provide some helix stabilization.31 The selective placement of a limited number of functional groups within the sequence offers the potential for isolating the specific novel macromolecular functions imparted by the functional groups. Although the presentation of functional groups at exact distances is not expected in solution because of the flexibility of the alanine-rich sequences,35,45 the regularity of the sequence and the controlled density of functional groups will provide unique opportunities to investigate structure-function relationships in these polymeric materials. Comparison of these protein polymers with similar and previously reported protein polymers will also allow elucidation of the possible effect of functional group density and amino acid sequence on the conformational behaviors of these macromolecules.21

Expression plasmids for helical protein polymers of varying molecular weights were produced via modified seamless cloning methods, as described previously.21,32,46 Expression plasmids of the correct sequence were transformed into the E. coli expression host BL21(DE3)pLysS to yield expression strains BL21(DE3)pLysS/pET28b-JS1-AX and BL21(DE3)pLysS/pET19b-RF1-BX. The protein polymers, A3 and B6, were expressed from bacterial expression strains BL21(DE3)pLysS/pET28b-JS1-A3 BL21(DE3)pLysS/pET19b-RF1-B6, with yields of ~15 mg/L. The target protein polymers produced from these expression hosts carry a decahistidine fusion tag (Figure 1c,d) that facilitates protein purification via immobilized metal chelate chromatography. The target protein polymers are selectively eluted after endogenous host proteins have been washed from the resin; representative purification results obtained via SDS-PAGE analysis are shown in the Supporting Information. Amino acid analysis (shown in the Supporting Information) and HPLC analysis (data not shown) of A3 and B6 indicate that the protein polymers purified in this manner are of at least 95% purity. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometric analysis of the protein polymers yield single peaks with masses that are consistent with those theoretically predicted (Supporting Information).

Circular dichroic spectroscopy was conducted to determine the secondary structure behavior of the protein polymers under various conditions. In the initial characterization, a phosphate buffer at pH 2.3 was employed so that the nonionic character of the protein polymer after modification of the Glu residues could be captured in these experiments. Results are shown in parts a and b of Figure 2 for protein polymers A3 and B6, respectively, in pH 2.3, 10 mM phosphate buffer. Both macromolecules display characteristic α-helical spectra with a maximum at 192 nm and a double minimum at 208 and 222 nm at low temperatures. The thermal melting curves of solutions of the two protein polymers at varying CD concentrations are identical, suggesting there is no detectable aggregation under these conditions, which was also suggested by analysis via native PAGE under a wider range of concentrations (data not shown). Further inspection of the data in Figure 2 indicates [θ]222/[θ]208 ratios near 1.1 for A3 and B6; a value of [θ]222/[θ]208 between 1.1 and 1.3 has been reported as characteristic of unaggregated and hydrated alanine-rich helical peptides.23

Figure 2.

Circular dichroic spectra of alanine-rich polypeptides in pH 2.3, 10 mM phosphate buffer. (a) CD spectra of A3 (23 μM) were collected in increments of 4 °C, at temperatures from 4 to 92 °C. (b) CD spectra of B6 (13 μM) were collected in increments of 4 °C at temperatures from 4 to 80 °C.

The mean residue ellipticity at 222 nm, [θ]222, which is indicative of α-helical content, was calculated to be -29 600 deg cm2 dmol-1 at 4 °C for A3 and -48 400 deg cm2 dmol-1 at 4 °C for B6. The fractional helicity for these alanine-rich protein polymers can be determined by comparing this experimental value of [θ]222 to a calculated value of 100% helicity determined for a polypeptide of a given length, which is based on an infinitely long α-helix having a value of -61 000 deg cm2 dmol-1.47,48 The fractional helicity of the protein polymers was determined to be 50% for A3 and 81% for B6. The differences in fractional helicity of the protein polymers A3 and B6 correlate with the differences in their molecular weights (8892 and 14 162 Da, respectively). The differences in helicity may also be related to the variations in their sequences; however, computational predictions of helicity49-53 show that the difference in helicity between the two sequences is insignificant (2.6%) when sequences of equal lengths are compared. The higher fractional helicity values previously reported for C2 (91%), despite its intermediate molecular weight (9889 Da), may be attributable to greater sequence regularity but may also be due to low-order oligomerization in this particular protein polymer (see below), which complicates simple comparisons based on molecular weight and sequence. Nevertheless, all three of these protein polymers adopt desired helical conformations and are currently being explored for their utility in controlling biologically relevant binding events.

The CD spectra for the protein polymers at various temperatures were also collected to ascertain any additional similarities or differences in the conformational behavior of the two macromolecules. As shown in Figure 2, a loss of ellipticity at 192 and 222 nm and a blue shift in the minimum at 208 nm are observed for both A3 and B6 with increasing temperature from 4 °C, indicating a conversion to a non-α-helical conformation. The presence of an isodichroic point at 203 nm in both sets of spectra indicates that these data can be approximated by a simple linear combination of helical and non-α-helical spectra and that the protein polymers undergo a transition between only two conformational states. While the high-temperature CD spectra of both macromolecules are similar to those reported for random coil structures, an increasing number of investigations suggest that the high-temperature spectra may also indicate a polyproline II helix structure,54-56 so we refer to the high-temperature spectra here simply as “non-α-helical”. The transition toward a non-α-helical structure begins at ~38 °C for A3, determined via analysis of full wavelength spectra and by estimating the temperature at which a 50% reduction in [θ]222 is observed. The lack of additional spectral changes above 76 °C suggests that the conformation change is complete at the elevated temperatures. In comparison, the midpoint of the conformational transition of B6 to a non-α-helical conformation occurs near 68 °C. The thermal stability of the α-helix has been shown to be dependent on length, with longer sequences maintaining helical structure at higher temperatures.23 The observed transition temperatures for A3, B6, and the previously reported C221 are consistent with the results of these prior investigations, as the temperature at which a measurable conformational change is observed (38, 68, and 45 °C, respectively) follows the trend in protein polymer lengths (93aa, 152aa, and 108aa, respectively).

The transition to a non-α-helical structure is completely reversible for both protein polymers, as indicated by the complete recovery of the initial low-temperature CD spectra upon cooling the samples from elevated temperatures. In contrast, complete reversibility was only observed at temperatures below 45 °C for C2,21 as the protein polymer converted irreversibly to β-sheet structure at temperatures above 45 °C. In the CD investigations reported here, there is no indication that A3 or B6 shows a similar conversion to β-sheet; their temperature-dependent conformational behavior is similar to that of other previously reported alanine-rich peptides.23,24,57,58

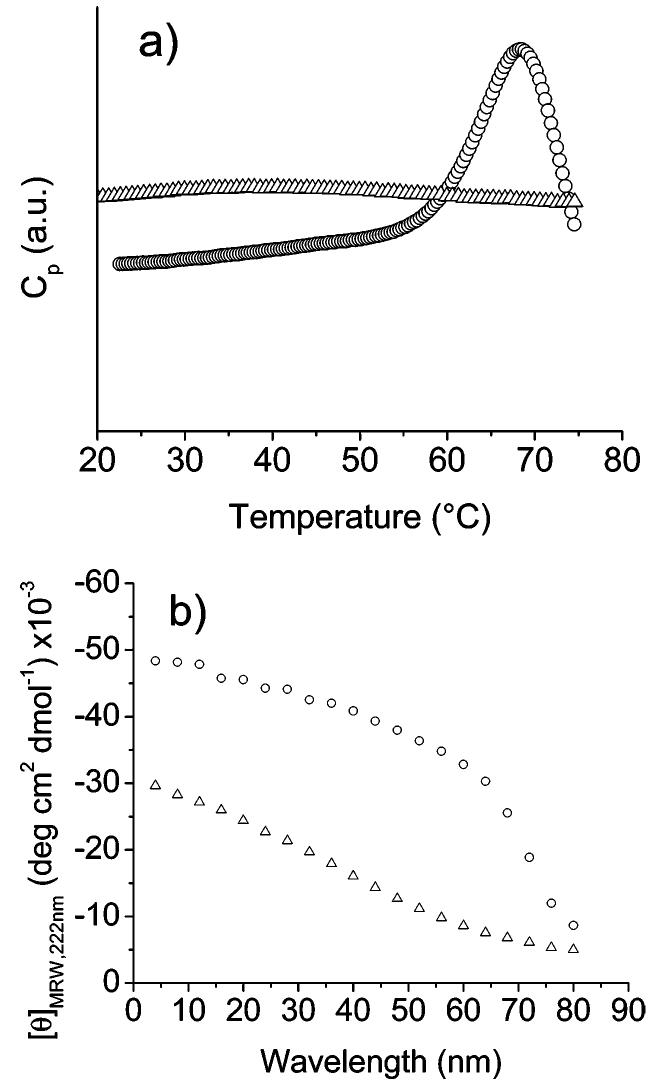

The thermal stability of the protein polymers at higher concentrations of 1 mg/mL in pH 2.3, 10 mM phosphate buffer was also monitored via differential scanning calorimetry. Figure 3a shows the calorimetric data for both A3 and B6 at a scan rate of 60 °C/h. Upon heating A3 from 17 to 75 °C, there are no distinct exothermic or endothermic transitions observed, suggesting the transition from α-helix to non-α-helix seen in the CD experiments is not cooperative. Similarly, in plots of [θ]222 vs temperature, as shown in Figure 3b, the helicity gradually decreases with temperature, consistent with both the DSC data and the reported behavior of other alanine-rich peptides.23 In contrast, the thermal scan of B6 (Figure 3a) clearly shows a cooperative endothermic transition with a peak at ~68 °C. This DSC-monitored transition corresponds directly with an apparently cooperative transition observed in the plot of [θ]222 vs temperature (Figure 3b). The calorimetric enthalpy, calculated via integration of the endothermic peak of the B6 transition, is ~60 kcal/mol, a value which is also consistent with other alanine-rich peptides and polypeptides.58 The lack of a cooperative transition for A3, compared to the cooperative transitions observed here for B6 and previously reported for C2,21 are consistent with the CD data and with the expected molecular weight dependence of cooperativity in conformational transitions as observed for globular proteins.59,60 Furthermore, both the Tm of the transitions for B6 and C2, and the corresponding enthalpy values, increase with molecular weight as expected in this molecular weight range (C2 < B6).59,60 Although changes in sequence may contribute to the differences in behavior of the protein polymers, the combination of the results from the helical prediction calculations, CD, and DSC suggest that the macromolecules exhibit controlled conformational behavior and thermal transitions that vary primarily with protein polymer molecular weight. Additional investigations of the behavior of macromolecules with these sequences, as a function of varying molecular weights, will further elucidate the detailed roles of molecular weight and sequence and will be presented in future reports.

Figure 3.

(a) Differential scanning calorimetry data for A3 (△) and B6 (○) in pH 2.3, 10 mM phosphate buffer. (b) Temperature dependence of [θ]222 monitored via CD spectroscopy for A3 (△) and B6 (○) in pH 2.3, 10 mM phosphate buffer.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was used to characterize the concentration dependence of the conformational behavior of the A3 and B6, as such dependence has been observed in other alanine-rich sequences.21,25 Representative infrared spectra of the two protein polymers in pH 2.3, 10 mM phosphate buffer in D2O are shown in Figure 4 for protein polymer concentrations of 100 and 400 μM. Deconvolution of the amide I region of the spectra yields calculated peak positions in all spectra at approximately 1660, 1645, and 1630 cm-1, which correspond to those reported for α-helix, random coil, and β-sheet structures, respectively,61,62 and comparison of the peak areas for the three structures provides insight regarding the predominant structure in the sample. The ratio of α-helix and random coil in A3 at both 100 and 400 μM (Figure 4a,b) is approximately 1:1, with a less significant contribution from β-sheet structures at both concentrations. The low contribution of β-sheet structure and the lack of change in the peak areas with increasing concentration suggest a low tendency to form β-sheet structures at elevated concentrations, which is consistent with the CD experiments that indicate a similar lack of β-sheet formation at elevated temperatures. The contribution of β-sheet structure in the IR spectra of A3, with no such contribution detected in the CD spectra, likely relates to the different protein polymer concentrations probed in the two different spectroscopic experiments. Parts c and d of Figure 4 show the spectra for B6 at 100 and 400 μM, respectively. Comparison of fitted peak areas indicates that the estimated α-helical content at the lower concentration is more than twice that of the β-sheet component, but upon a 4-fold increase in concentration, the relative β-sheet structure content increases and becomes approximately equal to that of the α-helix. It is unclear why the IR spectra of multiple and different samples of B6 reproducibly suggest a greater percentage of random coil character than α-helical character for this protein polymer as there was no such indication in CD experiments. Nevertheless, the IR results indicate an increase in β-sheet content with increasing protein polymer concentration and are generally consistent with previous results for C2.21 These results are also consistent with the reported tendency of other alanine-rich polypeptides to adopt β-sheet structure25,27,28 and suggest that the macromolecules have increasing tendencies toward β-sheet formation in the order A3 < B6 < C2, which correlates with the increasing distance between Glu residues of the protein polymers.

Figure 4.

Fourier transform infrared spectra of (a) A3 (100 μM), (b) A3 (400 μM), (c) B6 (100 μM), and (d) B6 (400 μM), in pH 2.3, 10 mM phosphate buffer in D2O. The experimental data (○) were fit using three peaks, shown as dotted lines, corresponding to α-helical, random coil, and β-sheet structures. The resulting fit is shown as the solid line through the experimental data.

Because the alanine and glutamine composition of the protein polymers reported here is similar to that of C2, we were initially surprised at the lack of conversion to β-sheet structure in the CD characterization of these protein polymers at low concentrations and elevated temperatures. The increased contribution of β-sheet structure observed via IR for solutions of B6 and C2 with increasing concentration suggested that at lower concentrations a similar transition may also occur but on a longer time scale than initially probed. Additional characterization via CD and DSC was therefore conducted. In previous DSC experiments on solutions of C2 at elevated temperatures,21 a post-peak exotherm was observed, indicating a kinetically slow conformational change to β-sheet. Similar DSC experiments for B6 also showed such an exotherm (Supporting Information), corroborating the conversion to β-sheet conformation for B6 under the DSC experimental conditions. The conformational behavior of A3 and B6 was therefore monitored via CD at low protein polymer concentration and at elevated temperatures over time; parts a and b of Figure 5 show a compilation of the CD spectra recorded every 8 min for A3 and B6, respectively, in pH 2.3, 10 mm phosphate buffer at 80 °C. There is no significant variation of the spectra in Figure 5a, indicating a lack of structural change in A3 after 25 h at 80 °C, which is consistent with the DSC and IR results. As shown in Figure 5b, the structure of B6 is primarily non-α-helical at 80 °C, with a minimum near 203 nm. After 7 h at 80 °C, the intensity at 203 nm decreases and a minimum at 218 nm and a maximum at 195 nm appear, indicating the conversion to β-sheet structure. Incubation of C2 at 80 °C causes a conversion to β-sheet within the first 10 min at the elevated temperature (Supporting Information). These data confirm the tendency of B6 to form β-sheet structures under appropriate conditions and also corroborate the IR data that indicate that the protein polymers have increasing propensities toward β-sheet formation with increasing distance between Glu residues of the macromolecules, in the order A3 < B6 < C2.

Figure 5.

Circular dichroic spectra of (a) A3 (23 μM) and (b) B6 (13 μM) in pH 2.3, 10 mM phosphate buffer at 80 °C. Spectra were taken every 8 min for 25.5 and 7 h, respectively.

Despite the fact that no turbidity is observed upon β-sheet formation in CD or DSC samples for any of the protein polymers, it is highly likely that these macromolecules are forming intermolecular β-sheet structures, as their sequences lack flexible regions necessary for the formation of intramolecular β-sheets. Indeed, native PAGE experiments confirm the formation of low-order intermolecular aggregates in solutions of C2 at elevated concentrations and temperatures and in solutions of B6 at elevated temperatures (data not shown). Therefore, an increased tendency toward β-sheet formation likely correlates with an increased tendency for intermolecular association by these macromolecules in aqueous solution. Given the moderate aqueous solubility of these sequences, differences in the extent of intermolecular association most likely result from differences in solubility based either on glutamic acid density or on the molecular weight of the macromolecule. The fact that the previously reported C2, which is of intermediate molecular weight of the three sequences, converts most readily to β-sheet as a function of temperature suggests that the origin of the effect lies primarily in a lower solubility as a result of the lower glutamic acid density, rather than lower solubility based on an increase in molecular weight of a moderately soluble sequence. In addition, the presentation of alanine residues in a regular (AAAQ) motif, as in the C2 sequence, may increase the tendency of the protein polymer to form intermolecular β-sheet structures via interaction of alanine segments, whereas the disruption of the alanine residue regularity may slow or eliminate the conversion to β-sheet, trends which were observed for B6 and A3, respectively. While it is impossible at present to determine the precise role of sequence in the increased tendency toward β-sheet formation for C2 vs B6 vs A3, these observations suggest that the increased tendency of these macromolecules to adopt intermolecular β-sheets is a function primarily of their hydrophobicity (glutamic acid residue density) rather than their molecular weight. A detailed and quantitative treatment of the association behavior of C2, B6, and additional sequences will be reported at a later date.

Owing to the observed β-sheet formation that could complicate the use of the helical macromolecules (after chemical modification) in biological applications, A3 and B6 were also characterized under physiologically relevant salt concentrations and at a pH range that may mimic the nonionic behavior of a modified Glu side chain (pH 2.3, 10 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl buffer (Supporting Information)). Both protein polymers maintain their α-helical character in the presence of isotonic salt. The addition of salt does not alter the helicity or induce stabilization of the α-helix upon heating in A3; however, for solutions of B6, the inclusion of 150 mM NaCl eliminates the transition from α-helix to a non-α-helical structure upon heating to 80 °C, similar to the stabilization of other alanine-rich sequences reported previously.21,30 Additionally, the mean residue ellipticity for both A3 and B6 in the pH 2.3, 10 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl buffer was measured at 222 nm as a function of time at a physiologically relevant temperature (37 °C). Despite the tendency of B6 to adopt β-sheet structures at elevated temperatures under other solution conditions, both A3 and B6 maintain a helical conformation at 37 °C, with the mean residue ellipticity at 222 nm remaining constant for over 12 h, suggesting the potential use of these protein polymers after modification of the glutamic acid residues and under biologically relevant conditions.

Conclusions

Alanine-rich amino acid sequences [AAAQEAAAAQAAAQAAQAAQ]x and [AAAQAAQAQAAAEAAAQAAQAQ]x were synthesized via protein engineering strategies to produce polypeptide sequences that might incorporate the architectural features of various naturally occurring alanine-rich proteins and synthetic alanine-rich peptides. Characterization of these macromolecules via CD, DSC, and FTIR methods indicates variations in their conformational behavior as a function of amino acid sequence, temperature, protein polymer concentration, and buffer conditions. Specifically, the helicity of the macromolecules, their measured melting temperature, and the calorimetric enthalpy of their unfolding increase, as expected, with molecular weight. Furthermore, variations in glutamic acid residue density and/or amino acid sequence are indicated to play an important role in the tendency of these protein polymers to adopt α-helical or β-sheet conformations under varying solution conditions. The observed dependence of conformational properties on sequence and functional group density suggests the potential to manipulate the behaviors of these types of macromolecular constructs by design, for biological and materials applications as well as for fundamental studies of protein aggregation events.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (1-P20-RR17716-01), the Army Research Office (DAAD19-02-1-0173), and the University of Delaware Research Foundation. We appreciate the donation of modified expression plasmids by Nichole Goeden-Wood and Jay Keasling. We thank Brian Morrison at the Molecular Analysis Facility at the University of Iowa for performing amino acid analysis and mass spectrometry. We appreciate the help of Ying Wang and Brian Polizzotti for mass spectrometry and gel electrophoresis data, respectively, on A3. We also thank Chris Roberts and Erin O'Dea for assistance with the DSC experiments.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Representataive purification results obtained via SDS-PAGE analysis; amino acid analysis; MALDI-TOF analysis; DSC trace of B6 showing irreversible transition at high temperatures; CD spectra for C2 showing conformational behavior upon incubation at 80 °C; CD spectra for A3 and B6 showing conformational behavior and stability in pH 2.3, 10 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl buffer. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References and Notes

- (1).Yu SM, Conticello V, Zhang G, Kayser C, Fournier MJ, Mason TL, Tirrell DA. Nature (London) 1997;389:187–190. doi: 10.1038/38254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Krejchi MT, Atkins EDT, Waddon AJ, Fournier MJ, Mason TL, Tirrell DA. Science. 1994;265:1427–1432. doi: 10.1126/science.8073284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Megeed Z, Cappello J, Ghandehari H. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2002;54:1075–1091. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Fahnestock SR, Irwin SL. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1997;47:23–32. doi: 10.1007/s002530050883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Qu Y, Payne SC, Apkarian RP, Conticello VP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:5014–5015. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Foo CWP, Kaplan DL. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2002;54:1131–1143. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Stephens JS, Fahnestock SR, Farmer RS, Kiick KL, Chase DB, Rabolt JF. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:1405–1413. doi: 10.1021/bm049296h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Winkler S, Szela S, Avtges P, Valluzzi R, Kirschner DA, Kaplan D. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1999;24:265–270. doi: 10.1016/s0141-8130(98)00088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Lazo ND, Downing DT. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:37340–37344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Davies PL, Baardsnes J, Kuiper MJ, Walker VK. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London, Ser. B. 2002;357:297–935. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Harding MM, Ward LG, Haymet ADJ. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;264:653–665. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Petka WA, Hardin JL, McGrath KP, Wirtz D, Tirrell DA. Science. 1998;281:389–392. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5375.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Frost DWH, Yip CM, Chakrabartty A. Biopolymers. 2005;80:26–33. doi: 10.1002/bip.20188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Vandermeulen GWM, Tziatzios C, Duncan R, Klok HA. Macromolecules. 2005;38:761–769. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Pandya MJ, Cerasoli E, Joseph A, Stoneman RG, Waite E, Woolfsow DN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:17016–17024. doi: 10.1021/ja045568c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Zimenkov Y, Conticello VP, Guo L, Thiyagarajan P. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:7237–7246. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kopecek J. Eur. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2003;20:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(03)00164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Vandermeulen GWM, Tziatzios C, Klok HA. Macromolecules. 2003;36:4107–4114. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Wang C, Stewart RJ, Kopecek J. Nature (London) 1999;397:417–420. doi: 10.1038/17092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Koltover I, Sahu S, Davis N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004;43:4034–4037. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Farmer RS, Kiick KL. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:1531–1539. doi: 10.1021/bm049216+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Wang Y, Kiick KL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. in press. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Miller JS, Kennedy RJ, Kemp DS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:945–962. doi: 10.1021/ja011726d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Williams L, Kather K, Kemp DS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:11033–11043. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Blondelle SE, Forood B, Houghten RA, Perez-Paya E. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8393–8400. doi: 10.1021/bi963015b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Blondelle SE, Forood B, Houghten RA, PerezPaya E. Biopolymers. 1997;42:489–498. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(19971005)42:4<489::AID-BIP11>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Gasset M, Baldwin MA, Lloyd DH, Gabriel J-M, Holtzman DM, Cohen F, Fletterick R, Prusiner SB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:10940–10944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Nguyen HD, Marchut AJ, Hall CK. Protein Sci. 2004;13:2909–2924. doi: 10.1110/ps.04701304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Cochran DAE, Penel S, Doig AJ. Protein Sci. 2001;10:463–470. doi: 10.1110/ps.31001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Scholtz JM, York EJ, Stewart JM, Baldwin RL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:5102–5104. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Scholtz JM, Qian H, Robbins VH, Baldwin RL. Biochemistry. 1993;32:9668–9676. doi: 10.1021/bi00088a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Goeden-Wood NL, Conticello VP, Muller SL, Keasling JD. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3:874–879. doi: 10.1021/bm0255342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Short Protocols in Molecular Biology. 4th ed. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Science. 1988;240:1648–1652. doi: 10.1126/science.3381086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Chakrabartty A, Baldwin RL. Adv. Protein Chem. 1995;46:141–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Aurora R, Rose GD. Protein Sci. 1998;7:21–38. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Penel S, Morrison RG, Mortishire-Smith RJ, Doig AJ. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;293:1211–1219. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Vila JA, Ripoll DR, Scheraga HA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:13075–13079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240455797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Cohen C, Parry AD. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Genet. 1990;7:1–15. doi: 10.1002/prot.340070102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Hodges RS. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1996;74:133–154. doi: 10.1139/o96-015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Schneider JP, Lombardi A, DeGrado WF. Folding Des. 1998;3:R29–R40. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0278(98)00011-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Micklatcher C, Chmielewski J. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1999;3:724–729. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(99)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Acharya A, Ruvinov SB, Gal J, Moll JR, Vinson C. Biochemistry. 2002;41:14122–14131. doi: 10.1021/bi020486r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Schnarr NA, Kennan AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:667–671. doi: 10.1021/ja027489b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Huang CY, Getahun Z, Wang T, DeGrado WF, Gai F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:12111–12112. doi: 10.1021/ja016631q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).McMillian RA, Lee TAT, Conticello VP. Macromolecules. 1999;32:3643–3648. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Kennedy RJ, Tsang K-Y, Kemp DS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:934–944. doi: 10.1021/ja016285c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Wallimann P, Kennedy RJ, Miller JS, Shalongo W, Kemp DS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:1203–1220. doi: 10.1021/ja0275360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Lacroix E, Viguera AR, Serrano L. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;284:173–191. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Munoz V, Serrano L. Biopolymers. 1997;41:495–509. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(19970415)41:5<495::AID-BIP2>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Munoz V, Serrano L. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;245:297–308. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Munoz V, Serrano L. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;245:275–296. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Combet C, Blanchet C, Geourjon C, Deléage G. TIBS. 2000;25:147–150. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01540-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Tiffany ML, Krimm S. Biopolymers. 1969;8:347. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Shi ZS, Olson CA, Rose GD, Baldwin RL, Kallenbach NR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:9190–9195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112193999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Chellgren BW, Creamer TP. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5864–5869. doi: 10.1021/bi049922v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Shalongo W, Dugad L, Stellwagen E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:8288–8293. [Google Scholar]

- (58).Scholtz JM, Marqusee S, Baldwin RL, York EJ, Stewart JM, Santoro M, Bolen DW. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:2854–2858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Richardson JM, Makhatadze GI. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;335:1029–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Medved LV, Privalov PL, Ugarova TP. FEBS Lett. 1982;146:339–342. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(82)80948-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Torii H, Tasumi M. In: Infrared Spectroscopy of Biomolecules. Mantsch HH, Chapman D, editors. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- (62).Surewicz WK, Mantsch HH, Chapman D. Biochemistry. 1993;32:389–394. doi: 10.1021/bi00053a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.