Abstract

Deletion of glucose transporter gene Slc2a3 (GLUT3) has previously been reported to result in embryonic lethality. Here, we define the exact time point of growth arrest and subsequent death of the embryo. Slc2a3−/− morulae and blastocysts developed normally, implanted in vivo, and formed egg-cylinder-stage embryos that appeared normal until day 6·0. At day 6·5, apoptosis was detected in the ectodermal cells of Slc2a3−/− embryos resulting in severe disorganization and growth retardation at day 7·5 and complete loss of embryos at day 12·5. GLUT3 was detected in placental cone, in the visceral ectoderm and in the mesoderm of 7·5-day-old wild-type embryos. Our data indicate that GLUT3 is essential for the development of early post-implanted embryos.

Introduction

The glucose transporter family comprises 14 members, GLUT1–12, GLUT14 and HMIT1 (H+/myo-inositol symporter; Joost & Thorens 2001, Scheepers et al. 2004). GLUT3 exhibits a high affinity for glucose (Km=1·8 mM) and was identified as the neuronal glucose transporter primarily located in axons and dendrites (Mantych et al. 1992, Nagamatsu et al. 1992, McCall et al. 1994, Vannucci et al. 1997, Simpson et al. 2008). Expression of GLUT3 coincides with maturation and regional cerebral glucose utilization (Vannucci et al. 1998). However, deletion of one Slc2a3 allele did not alter maintenance of neuronal energy supply, motor abilities, learning, and memory in mice (Schmidt et al. 2008). By contrast, heterozygous disruption of the blood–brain barrier glucose transporter GLUT1 in Slc2a1+/− mice resulted in a dramatic phenotype with microencephaly, impaired motor activity, cerebral ataxia, and multiple spontaneous cortical seizures (Wang et al. 2006). GLUT3 is also expressed in other cells (sperm, pre- and post-implantation embryo circulating white blood cells, and carcinoma cells) where it triggers the specific requirements for glucose (Simpson et al. 2008). Several studies have demonstrated that GLUT3 is crucial for the optimal development of the embryo (Pantaleon et al. 1997, Moley et al. 1998, Simpson et al. 2008, Wyman et al. 2008). Until compaction of the morula, the mammalian embryo derives energy from pyruvate and lactate (Barbehenn et al. 1974). The switch to metabolize glucose as the primary energy source coincides with the expression of GLUT3 from the late cleavage stages onward (Mantych et al. 1992). During early mouse embryogenesis, the expression of seven GLUT isoforms has been described. GLUT1 and GLUT9 were found in all pre-implantation stages, GLUT2 and GLUT3 were detected at the eight-cell stage (Hogan et al. 1991, Pantaleon et al. 1997), and GLUT4 and GLUT8 at the blastocyst stage and thereafter (Hogan et al. 1991, Aghayan et al. 1992, Carayannopoulos et al. 2004). By contrast, GLUT12 has only been detected at the eight-cell stage of the pre-implanted embryo (Zhou et al. 2004). Thus, the trophectodermic GLUT3 appeared the main glucose transporter responsible for the uptake of maternal glucose into the blastocyst. Its apical localization in the trophectoderm provides the inner cell mass (ICM) with glucose together with the basolateral GLUT1 (Pantaleon et al. 1997, Pantaleon & Kaye 1998). Downregulation of GLUT3 expression with antisense oligonucleotides resulted in a marked reduction of glucose uptake and in a 50% decrease in the number of embryos progressing to blastocyst stage. These data indicated that expression of the high-affinity transporter GLUT3 correlates with the switch to a metabolic preference for glucose versus pyruvate (Pantaleon et al. 1997). Similar defects in embryo development were observed in mice in which diabetes mellitus was induced by streptozotocin. GLUT3 expression was downregulated in the blastocysts (Moley et al. 1998). In addition, in vitro culture in high glucose concentration induced a downregulation of GLUT3 and an intrauterine growth retardation after transfer of blastocysts into recipient mice (Wyman et al. 2008).

Recently, it was described that disruption of the Slc2a3 gene in mice leads to embryonic lethality. Slc2a3−/− embryos were detected at the blastocyst stage but displayed increased apoptosis and delayed development. However, despite cell death, Slc2a3−/− embryos implanted but were lost at embryonic day 8·5 (Ganguly et al. 2007). Here, we describe the exact time point of embryonic lethality, and identify the defect responsible for death of post-implanted embryos. We show that disruption of GLUT3 expression has no effect on blastocyst development, but arrests embryonic development at day 6·5 correlating with initiation of apoptosis in ectodermic cells.

Materials and Methods

Inactivation of the Slc2a3 gene

For the generation of Slc2a3 knockout mice, we used the ES cell clone XG611 (Bay Genomics, San Francisco, CA, USA). The clone was tested for a single integration event of the gene trap vector in the Slc2a3 gene (see below). ES cells of clone XG611 were injected into blastocysts that were implanted into pseudopregnant females. Chimeras were mated with C57BL/6 mice, and F1 progeny carrying the transgene were backcrossed five times onto the C57BL/6 background. Genotyping of blastocysts, embryos, and mice was performed by PCR (for wild-type allele, forward primer: 5′-CCCTGCATTCACCGTTCC-3′, reverse primer: 5′-GATGACTCCAGTGTTGTAGC-3′; for knockout allele, forward primer: 5′-GCAGATCGCATCGATAACTTCG-3′, reverse primer: 5′-AGTATCGGCCTCAGGAAGATCG-3′). The animals were housed in air-conditioned rooms (temperature 20±2 °C, relative moisture 50–60%) under a 12 h light:12 h darkness cycle. They were kept in accordance with the UK legal requirements for the care and use of laboratory animals, and all experiments were approved by the ethics committee of the Ministry of Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry (State of Brandenburg, Germany).

RNA preparation, first-strand cDNA synthesis, and sequencing

ES cells from clone XG611 were harvested for RNA preparation as described (Gawlik et al. 2008). Primers specific for GLUT3 or β-geo cassette used in the PCR were as follows: forward primer (f1): 5′-ATGCTTTCGGTGATAGTCCTT-3′; forward primer (f2): 5′-AGGAACACTTGCTGCCGAGA-3′; reverse primer (r1): 5′-AGTATCGGCCTCAGGAAGATCG-3′; and reverse primer (r2): 5′-ATTCAGGCTGCGCAACTGTTGGG-3′.

Southern blotting

Genomic DNA of ES cell clone XG611 was digested with either BglII or NcoI, separated on a 0·7% agarose gel, and blotted onto a Hybond-N+-nylon membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). To verify a single recombination of the gene trap vector in the ES cell clone, a 722 bp PCR fragment (forward primer: 5′-TTATCGATGAGCGTGGTGGTTATGC-3′, reverse primer: 5′-GCGCGTACATCGGGCAAATAATATC-3′) of the β-geo cassette of the gene trap vector was used as a probe for hybridization after labeling with [α32P]dCTP with a random priming kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Embryo recovery and culture

Eight- to ten-week-old GLUT3 heterozygous mice were intercrossed overnight. Matings were confirmed by the identification of a vaginal plug in the next morning. For immunohistochemical characterization of blastocysts, the animals were killed on embryonic day 3·5 (E3·5 dpc), and embryos were obtained by flushing the uterine horns and cultured under mineral oil at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in DMEM high glucose/Na-pyruvate medium (PAA Laboratories, Linz, Austria) containing 10% FCS (PAN, Aidenbach, Germany). For analysis of outgrowth, blastocysts were cultured in M2 medium (Sigma). For the characterization of the development of morulae to blastocysts, one-cell-stage embryos (E0·5 dpc) were isolated and cultured until day 2·5 or 3·5 dpc (morula or early blastocyst stage, respectively). Thereby one-cell-stage embryos were incubated in M2 medium (Sigma) containing 0·5 mg/ml hyaluronidase (Sigma). In order to remove the cumulus cells, the embryos were washed several times in M2 medium before cultivation in DMEM high glucose/Na-pyruvate medium (PAA Laboratories) containing 10% FCS (PAN).

Immunostaining of blastocysts

Goat anti-GLUT3 antibody (Zhou et al. 2002) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (M20; Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Additional stainings of GLUT3 were performed with a polyclonal anti-GLUT3 antibody described by Hellwig et al. (1992). The anti-GLUT1 antibody was described previously (Hellwig et al. 1992). Results were confirmed with an additional rabbit anti-GLUT1 antibody (Ogawa et al. 2007) purchased from Santa Cruz (H43). Blastocysts were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0·2% saponin (Sigma) in PBS containing 0·1% PVP for 30 min, and blocked with antibody diluent (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA, USA). Blastocysts were incubated with the primary and secondary antibodies. Nuclei and cytoskeleton were counterstained. Fluorescence was detected with laser scanning confocal immunofluorescent microscopy (Leica TCS SP2 system; Leica, Mannheim, Germany). Genotypes of blastocysts were determined by PCR thereafter. Therefore, blastocysts were reincubated with water and proteinase k supplemented PCR buffer and PCR was performed as described above.

Analysis of post-implanted embryos

For histological analysis, uteri were isolated at embryonic days 6·0, 6·5, and 7·5 post-coitum and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Serial sections (2 μm) were generated from the whole embryo (∼16 sections of 6·5-day-old embryo) and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or stained for GLUT3, GLUT1, and activated caspase 3 (Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Beverly, MA, USA), for E-cadherin (clone HECD-1 in a dilution of 1:400) and for N-cadherin (1:500; Zymed, South San Francisco, CA, USA), or MKI67 (1:50; DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark).

Results

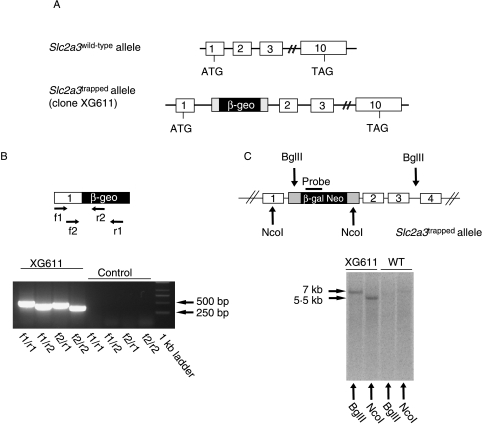

Disruption of the Slc2a3 gene

For the generation of conventional GLUT3 knockout mice (Slc2a3−/−), we used a gene trap ES cell clone (clone XG611). Insertion of the gene trap vector into intron 1 of Slc2a3 (Fig. 1A) resulted in a fusion protein consisting of five amino acids of GLUT3, neomycin phosphotransferase, and β-galactosidase. Correct integration of the gene trap vector into the Slc2a3 gene was verified by PCR (Fig. 1B). Sequence analysis of the PCR products indicated correct splicing of exon 1 to the splice acceptor site of the gene trap vector (data not shown). Digestion of genomic DNA from clone XG611 with either BglII or NcoI and hybridization with a β-galactosidase-specific probe resulted in single bands, indicating that the gene trap vector was integrated only once into the ES cell genome (Fig. 1B, right panel). For the generation of Slc2a3−/− mice, ES cells of clone XG611 were injected into blastocysts that were implanted into pseudopregnant females. Chimeras were mated with C57BL/6 mice, and F1 progeny carrying the transgene were backcrossed five times onto the C57BL/6 background.

Figure 1.

Disruption of the Slc2a3 gene by gene trapping. (A) Localization of the gene trap between exons 1 and 2 of the Slc2a3 gene. (B) Integration of the gene trap vector in intron 1 of the Slc2a3 gene in ES cell clone XG611 results in a fusion transcript containing exon 1 and the β-geo cassette. With the indicated primer pairs, four specific RT-PCR products were detected. (C) Southern blot analysis confirmed the single integration of the gene trap vector into the Slc2a3 gene of clone XG611. Genomic DNA was digested with BglII or NcoI and analyzed by Southern blotting with the indicated probe. A single 7 and 5·5 kb band respectively was detected in each panel.

Embryonic lethality of Slc2a3−/− mice prior to ED 12·5

Homozygous disruption of the Slc2a3 gene resulted in embryonic lethality, since only Slc2a3+/+ and Slc2a3+/− but no Slc2a3−/− mice could be genotyped after birth (Table 1). Approximately, twice as many Slc2a3+/− than Slc2a3+/+ mice were born, indicating that Slc2a3+/− mice had no disadvantage in embryonic development. In order to narrow down the time point at which disruption of Slc2a3 was lethal, embryos were isolated and genotyped at E12·5 dpc. Out of 40 embryos (5 litters) genotyped, no Slc2a3−/− mutants were detected, indicating that Slc2a3−/− mice die early in gestation.

Table 1.

Genotype distribution of progeny observed at weaning.

Tail biopsies were taken for genotyping by PCR as described in the Materials and Methods section.

| Number of animals | Distribution (%) | Expected (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | |||

| Slc2a3+/+ | 98 | 31 | 25 |

| Slc2a3+/− | 215 | 69 | 50 |

| Slc2a3−/− | 0 | 0 | 25 |

Disruption of Slc2a3 does not interfere with development of blastocysts

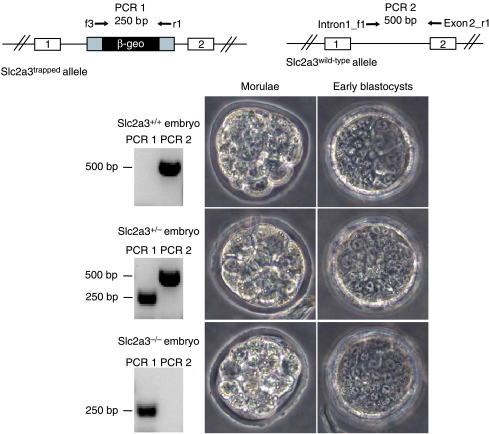

In order to determine whether ablation of GLUT3 results in an arrest of growth at the morula or blastocyst stage, 43 one-cell-stage embryos (0·5 dpc) of Slc2a3+/− mice matings (5 litters) were isolated and cultured until day 2·5 or 3·5 pc (morula or early blastocyst stage, respectively). The development of the embryos was documented by light microscopy, and genotypes of embryos were determined by PCR thereafter. Figure 2 illustrates that Slc2a3−/− morulae and blastocysts were indistinguishable from wild-type and Slc2a3+/− genotypes.

Figure 2.

Identification of Slc2a3−/− morulae and early blastocysts. Zygotes were isolated and cultured until the morula or early blastocyst stage, documented, and genotyped by PCR after lysis. PCR 1 generated a product of 250 bp corresponding to the trapped allele (upper left), and PCR 2 generated a 500 bp product of the wild-type allele (upper right). Images of a compacted morula (left) and an early blastocyst (right) of each genotype are shown together with the result of a representative genotyping reaction. Full colour version of this figure available via http://dx.doi.org/10.1677/JOE-08-0262.

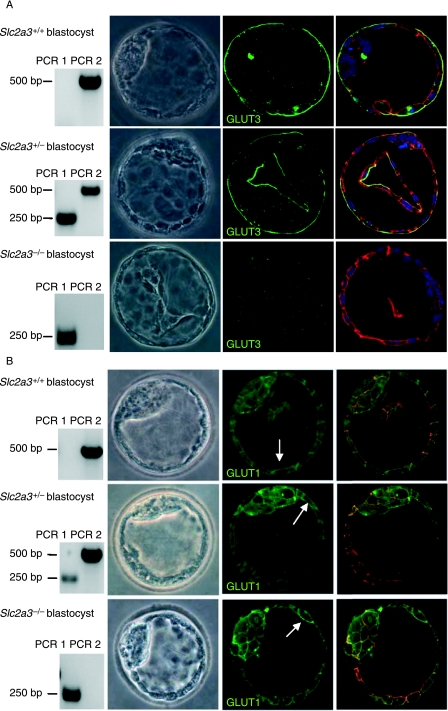

Growth of pre-implanted embryos was monitored for 24 h with blastocysts isolated from heterozygous matings at E3·5 dpc and individually cultured in vitro. From 10 litters, 25 Slc2a3+/+, 20 Slc2a3+/−, and 9 Slc2a3−/− blastocysts were obtained. The morphology of Slc2a3−/− blastocysts appeared normal with a proliferating ICM (Fig. 3A). Immunostaining of blastocysts with either of two anti-GLUT3 antibodies (middle panels) confirmed that all blastocysts genotyped as Slc2a3−/− lacked the GLUT3 protein (Fig. 3A). By contrast, Slc2a3+/+ and Slc2a3+/− blastocysts showed intense immunoreactivity. Here, GLUT3 was restricted to the apical membranes of the polarized epithelium (trophectoderm). In addition, staining for actin cytoskeleton and nuclei did not show any abnormality of Slc2a3−/− blastocysts (Fig. 3, right panels). In order to test the possibility of a compensatory increase or an altered subcellular distribution of GLUT1 in Slc2a3−/− blastocysts, an additional set of 13 blastocysts (4 litters) was stained with anti-GLUT1 antibody. GLUT1 immunoreactivity was predominantly detected in the basolateral, but also in the apical membranes of the trophectoderm and in the plasma membranes of cells from the ICM. No differences between Slc2a3+/+, Slc2a3+/−, and Slc2a3−/− blastocysts were detectable (Fig. 3B). The same result was obtained by a second anti-GLUT1 antibody (H43) demonstrating that the signals obtained by immunohistochemistry were specific (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Detection of GLUT3 and GLUT1 in Slc2a3+/+, Slc2a3+/−, and Slc2a3−/− blastocysts at day 4·5 pc. Blastocysts were isolated and stained for (A) GLUT3 or (B) GLUT1 in combination with an Alexa 488-labeled secondary antibody. Genotyping (left panels) was performed by PCR as described in the legend of Fig. 2. Nuclei (blue) and actin cytoskeleton (red) were counterstained. GLUT1 immunoreactivity is indicated by arrows.

In order to test whether extraembryonic components are affected in the absence of Slc2a3, we analyzed the trophoblast growth of isolated in vitro-cultivated embryos. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, see Supplementary data in the online version of the Journal of Endocrinology at http://joe.endocrinology-journals.org/content/vol200/issue1/, no difference in the proliferation capacity of trophectodermal cells was visible between wild-type, heterozygous, and knockout embryos.

Deletion of GLUT3 results in embryonic lethality at the gastrulation stage

In order to determine the exact time point of death of Slc2a3−/− mutants, uteri from heterozygous intercrosses were analyzed at different days of gestation (E6·0, 6·5, and 7·5 dpc). Genotypes were identified by the immunostaining of GLUT3. The distribution of the Slc2a3 alleles calculated for all embryos corresponded exactly with the Mendelian segregation, consistent with the conclusion that development and implantation of blastocysts was not affected by disruption of Slc2a3 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Genotype distribution of all embryos observed between embryonic days 6·0 and 7·5

| Slc2a3+/+ and Slc2a3+/− embryos | Slc2a3−/− embryos | Total number of embryos | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embryonic day | |||

| 6·0 | 6 | 3 | 9 |

| 6·5 | 17 | 6 | 23 |

| 7·5 | 24 | 8 | 32 |

| Sum 6·0–7·5 | 47 | 17 | 64 |

| Expected distribution (6·0–7·5) | 48 | 16 | 64 |

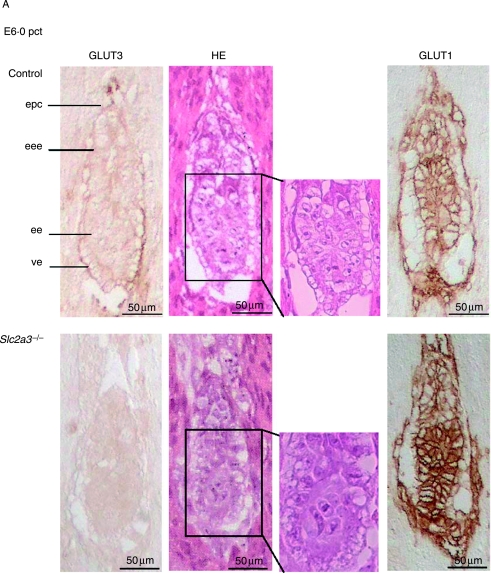

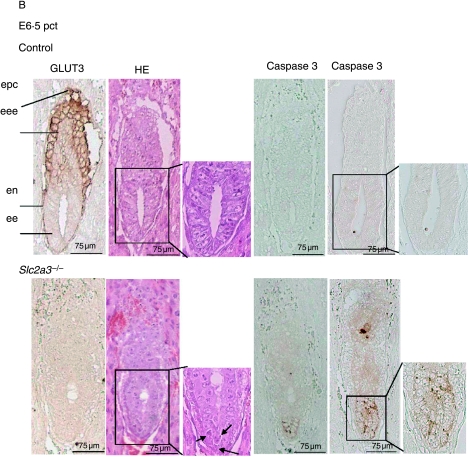

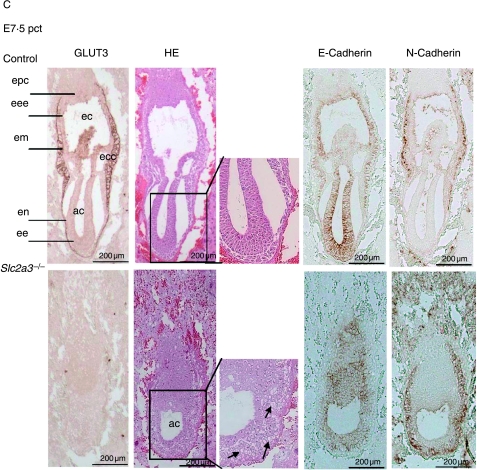

At E6·0 dpc, all embryos appeared normal with a well-organized ectoplacental cone, an extraembryonic and embryonic ectoderm, and a visceral endoderm (Fig. 4A). Slc2a3+/+ and Slc2a3+/− embryos were indistinguishable, with pronounced immunoreactivity of GLUT3 in the ectoplacental cone and visceral endoderm. Adjacent sections were stained for GLUT1, which was detected in all embryonic cells (Fig. 4A, right panels). Again, no compensatory increase in GLUT1 was detected. At E6·5 dpc, Slc2a3−/− mutants started to exhibit microscopical abnormalities in that the shape of cells within the ectoderm differed from that of control embryos. The ectodermal cell layer of the Slc2a3+/+ embryos composed of high columnar epithelial cells, whereas cells of Slc2a3−/− appeared round and uniform (see arrows in Fig. 4B). Furthermore, staining of embryos with an antibody against activated caspase 3-detected apoptotic cells in the distal part of the embryonic ectoderm (Fig. 4B). For quantification, we stained sections of six control and five knockout embryos in the area of the amniotic cavity with the anti-caspase 3 antibody and counted the activated caspase 3-positive cells. We detected 10·5±3·3 apoptotic cells in 6·5-day-old Slc2a3−/− embryos, but no apoptotic cell in control embryos (Mann–Whitney U-test, P<0·0043). In addition, no activated caspase 3-positive cells were obtained in E6·0 dpc embryos of both genotypes (data not shown). The number of caspase-positive cells was markedly increased in Slc2a3−/− embryos examined 4–6 h later (Fig. 4B, right panel). At E7·5 dpc, the development of Slc2a3−/− embryos was severely affected. Quantification of their mean length indicated that they were smaller than control embryos (mean length of Slc2a3−/− E7·5 dpc embryos, 600±30·9 μm; control embryos, 790·0±51·0 μm). In addition, the number of proliferating cells in the ectoplacental cone and the embryonic endoderm was reduced in Slc2a3−/− embryos (Supplementary Fig. 2, see Supplementary data in the online version of the Journal of Endocrinology at http://joe.endocrinology-journals.org/content/vol200/issue1/), supporting the finding of a marked growth retardation and a cessation of embryonic development in the absence of GLUT3. In addition, Slc2a3−/− embryos appeared to be disorganized. The higher magnification of HE-stained sections of 7·5-day-old embryos showed a vacuolization of ectodermal cells (see arrows in Fig. 4C). These cells still expressed the adhesion protein E-cadherin, at the cell surface and N-cadherin, a marker for the mesoderm (Hatta & Takeichi 1986). Thus, the Slc2a3−/− embryos started to develop the third germ layer. However, they did not develop the ectoplacental and exocoelomic cavities that were visible in control embryos at the age of 7·5 days. Instead, a condensed mass of cells was locatedin the region adjacent to the ectoplacental cone that contained a small amniotic cavity (Fig. 4C). By contrast, wild-type primitive streak-stage embryos exhibited a well-organized ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm, and had developed the ectoplacental cone and ectoplacental, exocoelomic, and amniotic cavities. Strikingly, GLUT3 immunoreactivity in primitive streak-stage embryos was restricted to the visceral endoderm and mesoderm, whereas the earliest signs of cell death were detected in the ectodermal cells of Slc2a3−/− embryos (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Defective development and apoptotic cell death in Slc2a3 mutant embryos. Histological analysis of Slc2a3−/− and control embryos (either Slc2a3+/+ or Slc2a3+/−). Serial sagittal sections of uteri from heterozygous matings at (A) day 6·0, (B) 6·5, and (C) 7·5 pc were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE), or used for staining of GLUT3, GLUT1, activated caspase 3, E-cadherin, or N-cadherin. ac, amniotic cavity; ec, ectoplacental cavity; ecc, exocoelomic cavity; ee, embryonic ectoderm; eee extraembryonic ectoderm; em, embryonic mesoderm; en, endoderm; epc, ectoplacental cone. Microscopical abnormalities in ectodermal cells of mutant embryos are indicated by arrowheads.

Discussion

The present data indicate that the glucose transporter GLUT3 is essential for substrate supply of the developing embryo, but not for the fertilization of oocytes or growth and implantation of blastocysts. Blastocyst formation was not affected by the absence of GLUT3 because Slc2a3−/− blastocysts were viable, capable to grow in vitro, and to implant in vivo. In wild-type blastocysts, GLUT3 was detected at the apical membrane of the trophectoderm (Fig. 3), as already described earlier (Pantaleon et al. 1997, Pantaleon & Kaye 1998), whereas GLUT1 was predominantly present in the basolateral and, to a smaller extent, in the apical membranes of the trophectoderm, and at the surface of cells from the ICM. This observation is in contrast to the results described by Pantaleon et al. (1997) and Pantaleon & Kaye (1998), who confined basolateral localization of GLUT1 in both morulae and blastocysts. One reason for this discrepancy might be the difference in the sensitivity of the anti-GLUT1 antibodies. A second reason for the discrepancy in GLUT1 distribution could be a difference in culture conditions, e.g., the glucose concentration. We cultivated blastocysts in the presence of 4·5 g glucose/l, which might alter the rate of glycolysis and thereby GLUT1 expression and/or localization. Several parameters, for example, oxygen concentration (Harvey et al. 2004), modify GLUT1 expression in blastocysts; also, glucose concentration itself was described to change GLUT1 protein levels in parallel with the transport activity (von der Crone et al. 2000) in other systems such as 3T3-L1 adipocytes.

Since ablation of GLUT1 (Wang et al. 2006) and also of GLUT8 (Membrez et al. 2006, Gawlik et al. 2008) did not affect implantation, blastocysts appear to be able to compensate for a reduction in the glucose transport capacity. This conclusion is in contrast to previous reports describing that in vitro cultivation of zygotes or two-cell embryos in the absence of glucose led to inhibition of blastocyst formation (Brown & Whittingham 1992) or a reduced number of ICM and trophectoderm cells (Brown & Whittingham 1991, Luisier et al. 2001). However, consistent with our results, Martin & Leese (1995) described that blastocysts developed in vitro from two-cell embryos in the complete absence of glucose, suggesting that pyruvate uptake can fully sustain the energy supply for blastocyst development.

In the present study, the absence of GLUT3 failed to alter expression or distribution of GLUT1 (Fig. 3B). By contrast, Ganguly et al. (2007) detected GLUT1 exclusively at the basolateral surface of wild-type blastocysts, at apical and basolateral membranes of heterozygous blastocysts, and in a scattered cytoplasmic distribution in Slc2a3−/− blastocysts. In addition, they detected Tunnel-positive, apoptotic cells in Slc2a3−/− blastocysts, whereas Slc2a3−/− blastocysts appeared healthy, and were able to grow in vitro and to implant into the uterus in the present study. It is unclear whether differences in the genetic background or in the conditions of blastocyst culture can account for these discrepant results. It should be noted, however, that Ganguly et al. (2007) distinguished the wild-type and Slc2a3+/− blastocysts not by genotyping but through the localization of GLUT3 (apical versus basolateral surface of the trophectoderm). Thus, the study lacks unambiguous proof that the observed differences between wild-type and heterozygote blastocysts are associated with the respective genotype.

The present data precisely identified the developmental stage and time point at which disruption of Slc2a3 is lethal. Slc2a3−/− embryos appeared normal until day 6·0, exhibited distinct morphological changes including apoptotic cells at day 6·5, were arrested in growth at day 7·5, and were completely lost at day 12·5 post-coitum. Ganguly et al. (2007) had indirect evidence that failure of Slc2a3−/− embryos occurred at neurulation, which begins with neural tube closure at embryonic day 8·5. They detected all three genotypes (wild-type, heterozygous, and knockouts) at embryonic day 8·5, but failed to find knockout embryos at day 9·5. According to our results Slc2a3−/−, embryos at day 8·5 were probably partially degraded. We discovered events of apoptosis starting at E6·5 dpc and a marked growth retardation and a cessation of development in the absence of GLUT3 at E7·5 dpc. This is similar to other knockout mice, e.g., the ZO2−/− mutant (Xu et al. 2008) or Arfrp1−/− mice (Mueller et al. 2002), in which apoptotic events during gastrulation resulted in a loss of the embryos at early time points.

Thus, lethality of Slc2a3−/− embryos started at day 6·5 by apoptosis of ectodermal cells. Two alternative hypotheses might explain why ectodermal cells that do not express GLUT3 undergo apoptosis. i) Defective placental development of Slc2a3−/− mice might be responsible for lethality of the embryos. ii) Reduced substrate supply via visceral endoderm that lack GLUT3 might arrest embryonic development. The finding that in vitro-cultivated Slc2a3−/− embryos did not show defects in trophectoderm development (Supplementary Fig. 1) might indicate that GLUT3 is a crucial transporter in a placenta-like function of the visceral endoderm, and that its disruption causes a deficiency in ectodermal cells.

Several studies have linked a reduced glucose transport to the initiation of apoptosis (Kan et al. 1994, Berridge et al. 1996). In the models of neuronal development and trophic factor deprivation, a decrease in glucose uptake is one of the earliest changes observed in the cascade of apoptosis (Johnson et al. 1996).

In summary, deletion of GLUT3 in mice arrests early embryonic development due to apoptosis of ectodermal cells shortly after implantation (E6·5 dpc). By contrast, the development of pre-implantation embryos is independent of GLUT3.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (GK1208, FOR441, AU178/3-1).

Acknowledgements

The skillful technical assistance of Brigitte Rischke and Elisabeth Meyer is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Aghayan M, Rao LV, Smith RM, Jarett L, Charron MJ, Thorens B, Heyner S. Developmental expression and cellular localization of glucose transporter molecules during mouse preimplantation development. Development. 1992;115:305–312. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.1.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbehenn EK, Wales RG, Lowry OH. The explanation for the blockade of glycolysis in early mouse embryos. PNAS. 1974;71:1056–1060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MV, Tan AS, McCoy KD, Kansara M, Rudert F. CD95 (Fas/Apo-1)-induced apoptosis results in loss of glucose transporter function. Journal of Immunology. 1996;156:4092–4099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JJ, Whittingham DG. The roles of pyruvate, lactate and glucose during preimplantation development of embryos from F1 hybrid mice in vitro. Development. 1991;112:99–105. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JJ, Whittingham DG. The dynamic provision of different energy substrates improves development of one-cell random-bred mouse embryos in vitro. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. 1992;95:503–511. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0950503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carayannopoulos MO, Schlein A, Wyman A, Chi M, Keembiyehetty C, Moley KH. GLUT9 is differentially expressed and targeted in the preimplantation embryo. Endocrinology. 2004;145:1435–1443. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von der Crone S, Deppe C, Barthel A, Sasson S, Joost HG, Schürmann A. Glucose deprivation induces Akt-dependent synthesis and incorporation of GLUT1, but not of GLUT4, into the plasma membrane of 3T3-L1 adipocytes. European Journal of Cell Biology. 2000;79:943–949. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly A, McKnight RA, Raychaudhuri S, Shin BC, Ma Z, Moley K, Devaskar SU. Glucose transporter isoform-3 mutations cause early pregnancy loss and fetal growth restriction. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;292:E1241–E1255. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00344.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawlik V, Schmidt S, Scheepers A, Wennemuth G, Augustin R, Aumüller G, Moser M, Al-Hasani H, Kluge R, Joost HG, et al. Targeted disruption of Slc2a8 (GLUT8) reduces motility and mitochondrial potential of spermatozoa. Molecular Membrane Biology. 2008;25:224–235. doi: 10.1080/09687680701855405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AJ, Kind KL, Pantaleon M, Armstrong DT, Thompson JG. Oxygen-regulated gene expression in bovine blastocysts. Biology of Reproduction. 2004;71:1108–1119. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.028639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta K, Takeichi M. Expression of N-cadherin adhesion molecules associated with early morphogenetic events in chick development. Nature. 1986;320:447–449. doi: 10.1038/320447a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellwig B, Brown FM, Schürmann A, Shanahan MF, Joost HG. Localization of the binding domain of the inhibitory ligand forskolin in the glucose transporter GLUT-4 by photolabeling, proteolytic cleavage and a site-specific antiserum. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1992;1111:178–184. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(92)90309-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan A, Heyner S, Charron MJ, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Thorens B, Schultz GA. Glucose transporter gene expression in early mouse embryos. Development. 1991;113:363–372. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.1.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EM, Deckwerth TL, Deshmukh M. Neuronal death in developmental models: possible implications in neuropathology. Brain Pathology. 1996;6:397–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1996.tb00872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joost HG, Thorens B. The extended GLUT-family of sugar/polyol transport facilitators: nomenclature, sequence characteristics, and potential function of its novel members. Molecular Membrane Biology. 2001;18:247–256. doi: 10.1080/09687680110090456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan O, Baldwin SA, Whetton AD. Apoptosis is regulated by the rate of glucose transport in an interleukin 3 dependent cell line. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1994;180:917–923. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luisier G, Urner F, Sakkas D. Facilitated glucose transporters play a crucial role throughout mouse preimplantation embryo development. Human Reproduction. 2001;16:1229–1236. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.6.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantych GJ, James DE, Chung HD, Devaskar SU. Cellular localization and characterization of Glut 3 glucose transporter isoform in human brain. Endocrinology. 1992;131:1270–1278. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.3.1505464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin KL, Leese HJ. Role of glucose in mouse preimplantation embryo development. Molecular Reproduction and Development. 1995;40:436–443. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080400407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall AL, Van Bueren AM, Moholt-Siebert M, Cherry NJ, Woodward WR. Immunohistochemical localization of the neuron-specific glucose transporter (GLUT3) to neuropil in adult rat brain. Brain Research. 1994;659:292–297. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90896-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Membrez M, Hummler E, Beermann F, Haefliger JA, Savioz R, Pedrazzini T, Thorens B. GLUT8 is dispensable for embryonic development but influences hippocampal neurogenesis and heart function. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2006;26:4268–4276. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00081-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moley KH, Chi MM, Knudson CM, Korsmeyer SJ, Mueckler MM. Hyperglycemia induces apoptosis in pre-implantation embryos through cell death effector pathways. Nature Medicine. 1998;4:1421–1424. doi: 10.1038/4013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller AG, Moser M, Kluge R, Leder S, Blum M, Büttner R, Joost HG, Schürmann A. Embryonic lethality caused by apoptosis during gastrulation in mice lacking the gene of the ADP-ribosylation factor-related protein 1. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2002;22:1488–1494. doi: 10.1128/mcb.22.5.1488-1494.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamatsu S, Kornhauser JM, Burant CF, Seino S, Mayo KE, Bell GI. Glucose transporter expression in brain. cDNA sequence of mouse GLUT3, the brain facilitative glucose transporter isoform, and identification of sites of expression by in situ hybridization. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:467–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa Y, Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Nandi A, Rosenblatt KP, Goetz R, Eliseenkova AV, Mohammadi M, Kuro-o M. BetaKlotho is required for metabolic activity of fibroblast growth factor 21. PNAS. 2007;104:7432–7437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701600104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantaleon M, Kaye PL. Glucose transporters in preimplantation development. Reproduction. 1998;3:77–81. doi: 10.1530/ror.0.0030077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantaleon M, Harvey MB, Pascoe WS, James DE, Kaye PL. Glucose transporter GLUT3: ontogeny, targeting, and role in the mouse blastocyst. PNAS. 1997;94:3795–3800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheepers A, Joost HG, Schürmann A. The glucose transporter families SGLT and GLUT: molecular basis of normal and aberrant function. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2004;28:364–371. doi: 10.1177/0148607104028005364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S, Richter M, Montag D, Sartorius T, Gawlik V, Hennige AM, Scherneck S, Himmelbauer H, Lutz SZ, Augustin R, et al. Neuronal functions, feeding behavior and energy balance in Slc2a3+/− mice. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90491.2008. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson IA, Dwyer D, Malide D, Moley KH, Travis A, Vannucci SJ. The facilitative glucose transporter GLUT3: 20 years of distinction. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;295:E242–E253. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90388.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannucci SJ, Maher F, Simpson IA. Glucose transporter proteins in brain: delivery of glucose to neurons and glia. Glia. 1997;21:2–21. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199709)21:1<2::aid-glia2>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannucci SJ, Clark RR, Koehler-Stec E, Li K, Smith CB, Davies P, Maher F, Simpson IA. Glucose transporter expression in brain: relationship to cerebral glucose utilization. Developmental Neuroscience. 1998;20:369–379. doi: 10.1159/000017333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Pascual JM, Yang H, Engelstad K, Mao X, Cheng J, Yoo J, Noebels JL, De Vivo DC. A mouse model for Glut-1 haploinsufficiency. Human Molecular Genetics. 2006;15:1169–1179. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyman A, Pinto AB, Sheridan R, Moley KH. One-cell zygote transfer from diabetic to nondiabetic mouse results in congenital malformations and growth retardation in offspring. Endocrinology. 2008;149:466–469. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Kausalya PJ, Phua DC, Ali SM, Hossain Z, Hunziker W. Early embryonic lethality of mice lacking ZO-2, but Not ZO-3, reveals critical and nonredundant roles for individual zonula occludens proteins in mammalian development. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2008;28:1669–1678. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00891-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R, Vander Heiden MG, Rudin CM. Genotoxic exposure is associated with alterations in glucose uptake and metabolism. Cancer Research. 2002;62:3515–3520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Kaye PL, Pantaleon M. Identification of the facilitative glucose transporter 12 gene Glut12 in mouse preimplantation embryos. Gene Expression Patterns. 2004;4:621–631. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]