Abstract

FDH (10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase) suppresses cancer cell proliferation through p53 dependent apoptosis but also induces strong cytotoxicity in p53-deficient prostate cells. In the present study we have demonstrated that FDH induces apoptosis in PC-3 prostate cells through simultaneous activation of the JNK and ERK pathways with JNK phosphorylating c-Jun and ERK1/2 phosphorylating Elk-1. The JNK1/2 inhibitor SP600125 or ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 prevented phosphorylation of c-Jun and Elk-1, correspondingly and partially protected PC-3 cells from FDH-induced cytotoxicity. Combination of the two inhibitors produced an additive effect. The contribution from the JNK cascade to FDH-induced apoptosis was significantly stronger than from the ERK pathway. siRNA knockdown of JNK1/2 or “turning off” the downstream target c-Jun by either siRNA or expression of the dominant negative c-Jun mutant, TAM67, rescued PC-3 cells from FDH-induced apoptosis. The pull-down assays on immobilized c-Jun demonstrated that c-Jun is directly phosphorylated by JNK2 in FDH-expressing cells. Interestingly, the FDH-induced apoptosis in p53-proficient A549 cells also proceeds through activation of JNK1/2 but the down-stream target for JNK2 is p53 instead of c-Jun. Furthermore, in A549 cells FDH activates caspase 9 while in PC-3 cells it activates caspase 8. Our studies indicate that the JNK pathways are common downstream mechanism of FDH-induced cytotoxicity in different cell types while the endpoint target in the cascade is cell type specific. JNK activation in response to FDH was inhibited by high supplementation of reduced folate leucovorin, further indicating a functional connection between folate metabolism and MAPK pathways.

Keywords: apoptosis, FDH, Jun kinases, c-Jun, RNAi, PC-3 cells

Introduction

JNKs (c-Jun NH2 terminal kinase/stress activated protein kinases) (1) are members of the family of mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPK), which also includes extracellular signal regulated kinases (ERKs) and p38 kinase (2). MAPKs are activated by variety of extra- and intra-cellular stimuli and control a diverse array of cellular functions such as gene expression, inflammatory response, differentiation, cell cycle, cell proliferation and apoptosis (3, 4). Earlier studies correlated stress-related activation of JNK and p38 with induction of apoptosis, while activation of ERK pathways in response to cytokines and growth factors was primarily implicated in mitogenic and anti-apoptotic effects (3). Numerous later studies resulted in the revision of this simplified view and provided more integrated picture in which the specific role of MAPKs in cellular processes depends on the stress signal and the cell type (5–7). In accordance with this concept both pro-survival and pro-apoptotic effects of JNKs have been reported (8). A role of JNKs in induction of apoptosis is well established: activation of the JNK pathway in response to various stress stimuli has been demonstrated to lead to apoptosis in cell culture and animal models while interruption of the JNK pathway suppresses apoptosis in many cases (3, 9–11). However, effects of JNK on apoptotic signaling are cell type-dependent rather than universal (reviewed in (12)).

JNKs phosphorylate and activate transcription factor c-Jun (13), which regulates broad spectrum of events including apoptotic cell death and oncogenic transformation. In recent years, many other proteins were identified as JNKs targets (reviewed in (14, 15)). The list of JNKs substrates includes numerous transcription factors, hormone receptors, histones, members of Bcl-2 family of apoptosis-related proteins, the E3 ligase Itch and component of cell motility machinery (reviewed in (14)). Such a diversity of the JNK substrates together with existence of three JNK genes and multiple splice variants (13, 16, 17), could explain complex and sometime opposite effects of the JNK pathways as well as the cell-type specificity. The net effect of JNK activation also depends on the signaling pathways that are simultaneously activated (12). In this context it should be noted that different MAPKs can act upon the same protein targets: for example, two common JNK substrates, transcription factors ATF-2 (18) and Elk-1 (19), are also canonical substrates for p38 and ERK MAP kinases. At the same time, numerous studies indicate that phosphorylation of c-Jun in vivo is selectively catalyzed by JNKs (20).

JNK pathways are activated in response to a variety of stress stimuli, including UV irradiation, DNA damage, heat shock and oxidants, as well as inflammatory cytokines. (21, 22). We have recently shown that elevation of a folate enzyme, 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase (FDH), in A549 cells activates an apoptotic pathway, in which the p53 tumor suppressor is phosphorylated by JNK2 at Ser6 (23). Most cancer cells are FDH-deficient and elevation of the enzyme in these cells produces strong cytotoxic effects including suppression of proliferation and apoptosis (24–26). Potential mechanisms of FDH-induced cellular stress are: inhibition of de novo purine biosynthesis (26), altered methylation processes (27), and overall limitation of carbon units in the folate pool (28). An additional mechanism could be an increase of oxidative stress since the FDH substrate, 10-formyltetrahydrofolate, has been proposed to serve as an important cellular antioxidant (29). In A549 cell line, as well as in HCT-116 cells, both of which are p53-proficient, the FDH-induced suppressor effects are strictly p53-dependent (25, 26). At the same time FDH is cytotoxic in p53-deficient cell lines as well (24). The pathways through which FDH operates in these cells were not clear. In the present study, we examined the mechanisms of FDH-induced apoptosis in p53-null prostate cell line PC-3 and demonstrated that FDH still activates the JNKs pathway in these cells but it is diverted to the phosphorylation of c-Jun instead of p53.

Results

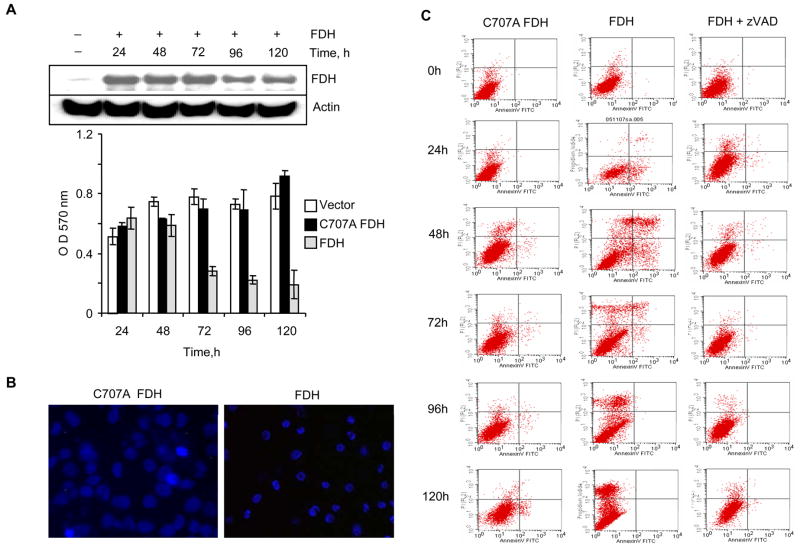

FDH induces apoptosis in PC-3 prostate cells

We have previously observed that FDH has strong cytotoxic effects on numerous cancer cell lines, including androgen-independent p53-null PC-3 prostate cells (24). To determine whether FDH induces apoptosis in these cells, we transiently transfected them with pcDNA3.1/FDH construct. Western blot analysis indicated appearance of FDH 24 h post-transfection and its levels remained constant up to 5 days post-transfection (Fig. 1A). Simultaneously, proliferation of FDH expressing cells was strongly inhibited (Fig. 1A). Expression of catalytically inactive C707A FDH mutant (24) did not inhibit proliferation (Fig. 1A), indicating specificity of the antiproliferative effects of catalytically active FDH. The induction of apoptosis in FfDH-expressing cells was evident from the cell morphology: Hoechst stained cells exhibited condensed and fragmented nuclei (Fig. 1B). Annexin V assay has further confirmed apoptosis, which was observed as early as 24 h post-transfection (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

FDH antiproliferative effects in PC-3 cells. A. Viable cells assessed by MTT assay at indicated time points after FDH expression (gray bars); C707A mutant expression (black bars); or after transfection with empty vector (control, open bars). Inset shows FDH levels evaluated by immunoblot. B. Fluorescence microscopy of Hoechst stained cells expressing FDH or its C707 mutant. Cells were incubated with Hoechst 33258 (2.5 μg/ml) for 10 min and examined using Olympus IX70 fluorescent microscope. C. Apoptosis detected by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) flow cytometry in PC-3 cells. Left panel (control), cells transfected for inactive C707A FDH expression; middle panel, cells transfected for FDH expression; right panel, cells transfected for FDH expression in the presence z-VAD-fmk. Time post-transfection is indicated.

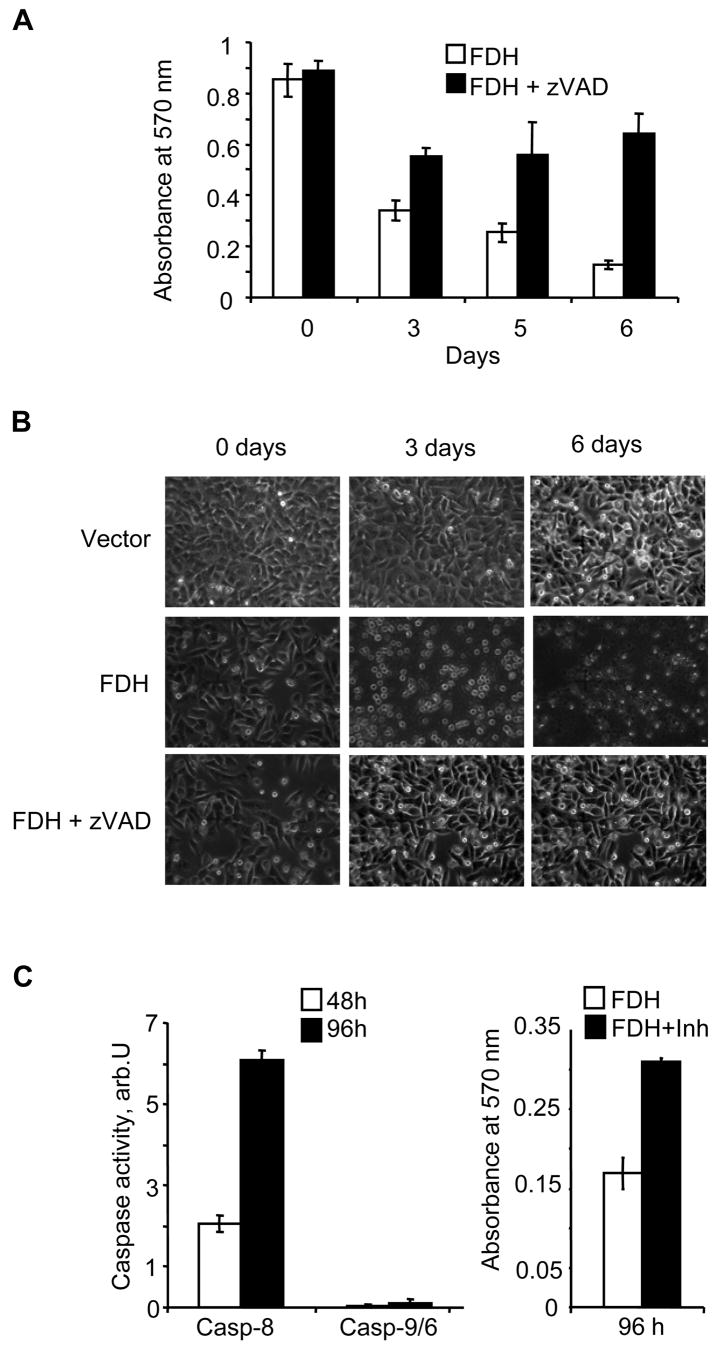

The pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk effectively protected PC-3 cells against FDH-induced cytotoxicity at 50 μM concentration (Fig. 2A). z-VAD-treated FDH-expressing cells displayed morphological characteristics of non-apoptotic cells in contrast to FDH-expressing non-treated cells, in which apoptotic morphology was clearly seen (Fig. 2B). In agreement with these data, annexin V assays demonstrated a strong suppression of FDH-induced apoptosis in presence of z-VAD-fmk (Fig. 1C). Caspase assays have shown strong increase of caspase 8 activity in FDH-expressing PC-3 cells while caspase 9 was not activated in these cells (Fig. 2C). In agreement with these data, treatment of cells with the caspase 8-specific inhibitor z-IETD-fmk (30) protected them from antiproliferative effects of FDH at 30 μM concentration (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Caspase inhibitors protect PC-3 cells from FDH suppressor effects. A. Proliferation of FDH expressing cells in the presence (black bars) and in the absence (open bars) of z-VAD-fmk assessed by MTT assays. B. Phase-contrast microscopy of “empty” vector transfected cells (upper panel), FDH transfected cells (middle panel) and FDH-transfected cells in the presence of z-VAD-fmk (lower panel). C. Activities of caspase 8 and 9/6 in FDH-expressing cells (left panel) and proliferation of the cells in the presence of the caspase 8 inhibitor z-IETD-fmk assessed by MTT assays (right panel). FDH post-transfection time is indicated.

FDH activates JNK and ERK in PC-3 cells

To investigate whether FDH-induced apoptosis is mediated via MAPK signaling pathways, we assessed phosphorylation of JNK1/2, ERK1/2, and p38 in FDH-transfected cells. FDH expression resulted in strong phosphorylation of JNK1/2 and ERK1/2 but not p38 (Fig. 3A). Phosphorylation of the kinases became prominent at 48 h post-transfection and stayed at maximum level till 96 h post-transfection. At the same time, basal levels of kinases themselves did not change (Fig. 3A). We have also examined levels of phosphorylated c-Jun, Elk-1, and ATF-2, canonical targets of MAPKs. Two of these proteins, c-Jun and Elk-1, demonstrated higher levels of phosphorylated form at 48–72 h FDH post-transfection, while phosphorylation of ATF-2 was not changed (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

FDH induces phosphorylation of JNK1/2 and ERK1/2 (A), and c-Jun and Elk-1 (B) in PC-3 cells. FDH post-transfection time is indicated.

MAPK inhibitors rescue PC-3 cells from FDH-induced apoptosis

To examine the specific role of JNK1/2 and ERK1/2 in PC-3 cells in response to FDH, we inhibited these kinases with the specific inhibitors SP600125 and PD98059, correspondingly. The JNK inhibitor completely blocked phosphorylation of c-Jun at concentration of 10 μM while the ERK inhibitor significantly decreased levels of phosphorylated Elk-1 at concentrations 10–50 μM (Fig. 4A). The level of phosphorylated ATF-2 was not affected by either of these inhibitors (Fig. 4A). In agreement with the decreased levels of phosphorylated c-Jun and Elk-1, we observed the decrease in number of apoptotic cells after FDH expression (Fig. 4B). However, protection from apoptosis was much more profound with the JNK inhibitor than with the ERK inhibitor as was seen in the clonogenic assays (Fig. 4C): survival rate compared to the control non-treated cells was 50% and 28%, correspondingly. Combination of the two inhibitors produced the additive effect with almost quantitative outcome (Fig. 4C). We have also observed the decrease in levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2 in the cells treated with PD98059 (Fig. 4A). Such effects, however, have been reported and they are likely the result of the inhibition of the ERK upstream kinase MAPKK1 (31, 32).

FIGURE 4.

MAPK inhibitors protect cells against FDH-induced apoptosis. A. Effects of the ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 and the JNK inhibitor SP600125 on phosphorylation of MAPKs and their substrates in FDH-expressing cells. Concentrations of inhibitors (μM) are indicated. B. Apoptosis detected by FACS flow cytometry in FDH expressing PC-3 cells: in the absence of MAPK inhibitors (left panel); in the presence of 10 μM of the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (middle panel); in the presence of 30 μM the ERK1/2 inhibitor (right panel). Time of FDH post-transfection is indicated. C. Colony formation by PC-3 cells expressing FDH and treated with SP600125, PD98059 or both simultaneously.

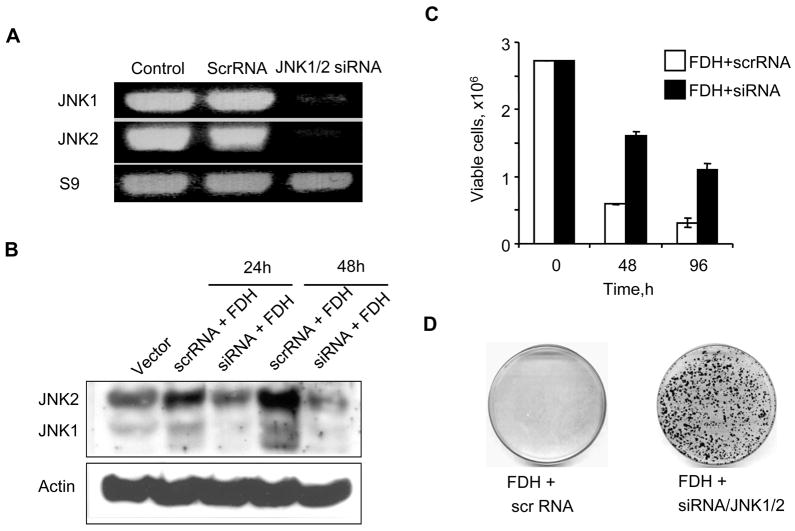

siRNA knock down of JNKs protects PC-3 cell from FDH suppressor effects

The experiments with the JNK inhibitor indicated that the JNK pathways are important for the response to FDH-related stress in PC-3 cells. This conclusion was further confirmed in experiments with siRNA knock down of JNKs. Both JNK1 and JNK2 were simultaneously targeted in these experiments. As can be seen in Fig. 5, A and B, the knock down was efficient with the strong decrease in the levels of mRNA and the protein for both JNK1 and JNK2. Cell viability assessed by trypan blue exclusion as well as clonogenic assay showed that JNK knock down protects PC-3 cells against FDH suppressor effects (Fig. 4, C and D).

FIGURE 5.

JNK knock down rescues PC-3 cells from cytotoxic effects of FDH. A. Levels of JNK1/2 mRNA measured by RT-PCR 48 h post-transfection with siRNA targeting simultaneously JNK1 and JNK2. Samples were normalized by the level of Sp9. B. Levels of JNK1/2 proteins after the siRNA silencing in response to FDH (time after FDH expression is indicated). Actin is shown as a loading control. C. Trypan blue exclusion assay of viable cells at different time FDH post-expression after transfection with JNK siRNA or scrambled RNA. D. Colony formation by PC-3 cells expressing FDH transfected with JNK siRNA or scrambled RNA.

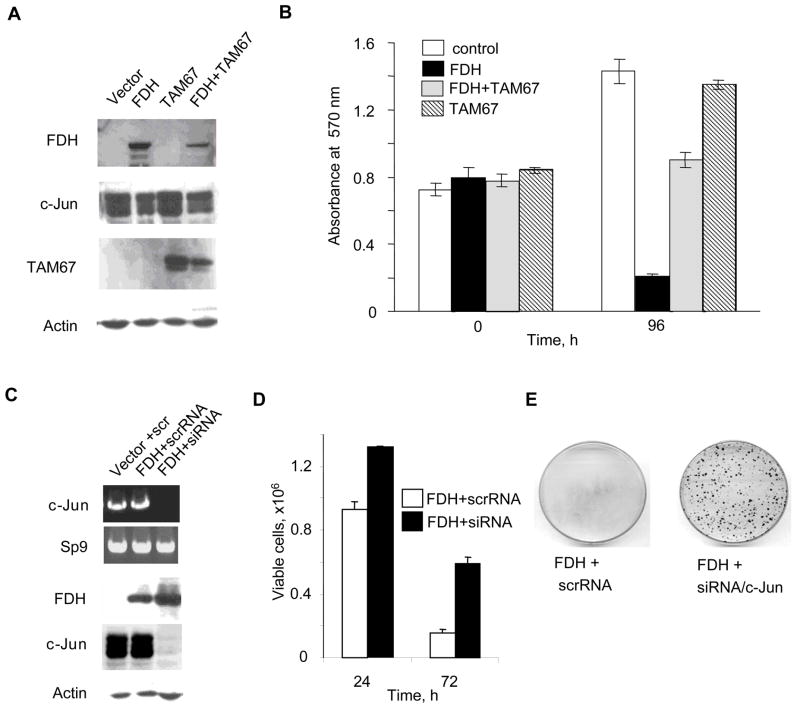

c-Jun is the downstream mediator of FDH stress in PC-3 cells

Phosphorylation of the canonical JNK target, c-Jun, in PC-3 cells in response to FDH (Fig. 3) implies its role in FDH effects. To study whether disabling c-Jun will block antiproliferative effects of FDH in these cells, we have expressed the dominant-negative truncated mutant of c-Jun, TAM67, which inhibits the c-Jun-mediated signaling pathways (33). We have observed that expression of TAM67 significantly decreased FDH antiproliferative effects in this cell line (Fig. 6, A and B) supporting the crucial function of c-Jun in response to FDH-induced stress. Additional support of the role of c-Jun in this system came from experiments with siRNA knock down of c-Jun, in which strong silencing of the protein was achieved using Steals RNA duplex (Fig. 6C). We have observed that, similarly to TAM67 mutant, the c-Jun silencing strongly protected PC-3 cells against FDH cytotoxicity (Fig. 6, D and E).

FIGURE 6.

c-Jun is the down stream target of JNK1/2 in the FDH induced apoptotic pathway in PC-3 cells. A. Levels of FDH, c-Jun and TAM67 after transient expression in PC-3 cells evaluated by immunoblotting. Actin is shown as a loading control. B. MTT assay of PC-3 cells expressing FDH, TAM67 or both simultaneously. C. siRNA silencing of c-Jun in FDH-expressing PC-3 cells (top panel, levels of c-Jun mRNA measured by RT-PCR, samples were normalized for Sp9; bottom panel, levels of FDH and c-Jun proteins assessed by immunoblot, actin is shown as a loading control). D. Trypan blue exclusion assay of viable cells at different time FDH post-expression after transfection with c-Jun siRNA or scrambled RNA. E. Colony formation by PC-3 cells expressing FDH transfected with c-Jun siRNA or scrambled RNA.

c-Jun is phosphorylated by JNK2 in response to FDH in PC-3 cells

We have previously shown that, in A549 cells, FDH induces a cascade in which JNK2 is the endpoint kinase phosphorylating p53 at Ser6 (23). In the present study we have found that JNK2 is also the ultimate kinase of the cascade in PC-3 cells but it uses a different substrate, c-Jun. We have used c-Jun immobilized on agarose beads to pull down the kinase that is responsible for c-Jun phosphorylation. These experiments have demonstrated that phosphorylated JNK2, but not JNK1 was pulled down from PC-3 cells after expression of FDH (Fig. 7A). In the absence of FDH, there was no JNK2 detected in the pulled down sample (Fig. 7A). In agreement with these results, in vitro kinase assay has demonstrated that c-Jun was phosphorylated in vitro by JNK2 pulled down from FDH expressing cells (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

c-Jun is phosphorylated by JNK2 in response to FDH in PC-3 cells. A. Levels of JNK1 and JNK2 and their phosphorylated forms pulled down from FDH expressing cells on immobilized c-Jun. B. In vitro kinase assay showing phosphorylation of c-Jun by the a kinase pulled down from FDH expressing cells.

Leucovorin supplementation inhibits FDH-mediated JNK activation

FDH suppressor effects can be reversed by supplementation of high concentrations of reduced folate leucovorin (5-formyltetrahydrofolate) (24, 34). To investigate whether the protective effects of leucovorin proceed through inhibition of the JNK pathway, we evaluated JNK phosphorylation in FDH-expressing PC-3 and A549 cells growing on media containing 10 μM of this reduced folate. We observed that leucovorin strongly inhibited FDH-induced phosphorylation of JNK in both cell lines (Fig. 8). We also observed the lack of phosphorylation of c-Jun in PC-3 cells and Ser6 of p53 in A549 cells in these experiments (Fig. 8). Another MAPK pathway activated by FDH in PC-3 cells, ERK, was inhibited as well: leucovorin resulted in complete abolishing phosphorylation of both ERK and its substrate Elk-1 while they are strongly phosphorylated in the absence of this supplementation (Fig. 8, A).

FIGURE 8.

High leucovorin supplementation prevents activation of MAPK pathways in response to FDH. A. Levels of phosphorylated JNK, ERK, c-Jun and Elk-1 in PC-3 cells in the presence and in the absence of leucovorin (LU) supplementation. B. Levels of phosphorylated JNK and Ser6 p53 in A549 cells in the presence and in the absence of leucovorin (LU) supplementation. Expression of FDH in Tet-On A549/FDH cells was induced by addition of 2.5 μg/ml doxycycline.

Discussion

We have previously demonstrated that FDH induces p53-dependent apoptosis in p53-proficient cell lines (25, 26). In A549 cells, this apoptosis proceeds through phosphorylation of p53 at Ser6 by JNKs while the canonical JNK target, c-Jun, was not phosphorylated in these cells in response to FDH (23). The fact that JNK apoptotic pathway can proceed in bypass of c-Jun is not unusual. For example, JNK-dependent apoptosis in the absence of c-Jun phosphorylation was observed in A549 cells in response to ceramides (35). In addition, JNK-independent phosphorylation of c-Jun can be a pro-survival factor in these cells (36).

Surprisingly, while disabling the p53 pathways in p53-proficient cells protects them from FDH-induced apoptosis and associated cytotoxicity (26), at the same time FDH induces antiproliferative effects in p53-deficient prostate cancer cell lines (24). This puzzling observation prompted us to investigate mechanisms of cytotoxicity in response to FDH in these cells. Since tumor-suppressor p53 is mutated in more than 50% of human cancers (37), clarification of this pathway might have important implications. Potentially, FDH as a metabolic regulator could induce non-apoptotic antiproliferative effects through depletion of important cellular metabolites. Indeed, strong decrease of FDH substrate, 10-formyltetrahydrofolate and associated depletion of ATP/GTP were observed in FDH-expressing cells (26, 34). We found, however, that similar to the p53-proficient cells FDH induces apoptosis in p53-deficient PC-3 cells. Moreover, the apoptosis in these cells also proceeds through activation of the JNK pathways as in A549 cells. In contrast to A549 cells, JNK phosphorylates c-Jun in response to FDH in PC-3 cells. Another difference with A549 cells was activation of ERK1/2 in PC-3 cells. Interestingly, in contrast to A549 cells, in which FDH-induced apoptosis is associated with activation of caspase 9 (25), in PC-3 cells this caspase was not active. Instead, activity of caspase 8 was strongly up-regulated in these cells in response to FDH. This is in agreement with several reports, which demonstrated connection between c-Jun/JNK pathway and caspase 8, but not caspase 9, activation in several cell lines (38–40). Of note, such a phenomenon was observed in PC-3 cells, in which JNK activation appears to be upstream of caspase 8 (38). In support of this conclusion, it has been recently shown that caspase 8 promoter has a c-Jun/AP1 regulatory site, which controls transcription in response to mitomycin C in Huh7 hepatoma cells (41).

In general, the JNK pathways are associated with phosphorylation of c-Jun that protects it from ubiquitine/proteasome degradation (42) and activates its function as a transcription factor (17, 43). Activation of JNKs and associated phosphorylation of c-Jun is a common event in PC-3 cells although final outcome can be either proapoptotic (44, 45) or prosurvival (46, 47). JNKs can also act upon such downstream targets as ATF-2 (18) and Elk-1 (19), which are substrates for other MAPKs (48). In our studies, JNK was responsible for c-Jun phosphorylation only, while Elk-1 was simultaneously phosphorylated by ERK1/2. Although ERK1/2 activation is commonly associated with cell proliferation and is viewed as anti-apoptotic factor, prolonged activation of ERK1/2 is often responsible for cell death (49). In PC-3 cells, for example, the ERK dependent apoptosis was demonstrated in response to phenylethyl isothiocyanate treatment (50). Apparently, the crosstalk between JNK and ERK pathway is a common phenomenon in PC-3 cells: several studies have shown that apoptosis in these cells proceeds through simultaneous activation of JNK and ERK, but not p38 (51–54). Similarly, JNK and ERK pathways were simultaneously activated in response to FDH in these cells. The lack of a synergistic effect between these two pathways in our experiments implies that they operate independently in response to FDH stress. Stronger contribution of JNKs to FDH-induced apoptosis and the previously established role of this pathway in FDH signaling in A549 cells (23) indicate that JNKs are the main downstream effectors of FDH and a common mechanism of its cytotoxicity in different types of cancer.

Further evidence for the conclusion regarding universal role of JNK in mediation of FDH cytotoxicity came from experiments with supplementation of FDH-expressing cells with the reduced folate leucovorin (5-formyltetrahydrofolate). We have earlier demonstrated that high concentration of leucovorin in culture medium protected cells against FDH and produced clones, which are FDH resistant (24, 34). Mechanism of the immediate protection by leucovorin supplementation is related to a strong increase of intracellular pool of reduced folates with simultaneous inhibition of FDH by the excess of tetrahydrofolate, the product of FDH-catalyzed reaction (34). Of note, the protective effect of leucovorin was observed in both PC-3 and A549 cell lines (24). Therefore, it would be expected that, if activation of JNK and phosphorylation of its substrates is the major down stream event in apoptotic response to FDH, this cascade should be disabled in protected cells despite of their origin. This was found to be the case: leucovorin prevented phosphorylation of JNK in both cell lines. In accordance with this finding, it also prevented phosphorylation of JNK targets, c-Jun and p53, in PC-3 and A549 cells, correspondingly. Interestingly, inhibition of the ERK component of FDH response was further observed in PC-3 cells supporting our conclusion that this pathway plays a pro-apoptotic role upon FDH expression in these cells.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that activation of JNK pathways is a common downstream event in FDH-induced cytotoxicity and answered the question of how FDH can induce apoptosis in p53-deficient cells. It also indicates that, depending on the cell type, the FDH-induced JNK signaling can diverge at the level of JNK substrate. In PC-3 cells, for example, this pathway proceeds through phosphorylation of a canonical JNK substrate, c-Jun, while in A549 cells c-Jun is not a target for FDH-induced JNKs. It is not clear at present what switches JNK activity to a different substrate in response to FDH. Obviously, availability of additional factors, such as scaffold proteins, or co-activation of additional pathways could contribute to this mechanism. For example, in PC-3 cells FDH induces ERK1/2, which is not the case in A549 cells. Of note, simultaneous activation of JNK/c-Jun and ERK/Elk-1 pathways is a common apoptotic response in PC-3 cells. Our study also indicates a functional connection between folate metabolism and MAPK pathways, although precise mechanisms of how folate regulates these pathways await further investigations.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

MAP kinase inhibitors were obtained from Calbiochem (PD98059) and Sigma (SP600125). Caspase inhibitors were from Calbiochem. Stock solutions of the inhibitors were prepared in DMSO. Inhibitors were added to the cell culture 24 h FDH post-transfection. Media containing inhibitors were replaced every 48h.

Cell culture

The prostate adenocarcinoma cell line PC-3 was obtained from American Type Culture Collection. Non-small cell lung carcinoma cell line A549 capable of Tet-On inducible expression of FDH was generated in our previous studies (25). Cell culture media and reagents were purchased from Invitrogen. Cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (complete medium) at 37 °C under humidified air containing 5% CO2. Cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion or by MTT cell proliferation assay using cell Titer 96 kit (Promega).

Transfection

PC-3 cells (about 1.4 × 106) were transfected with pcDNA3.1/FDH vector (2 μg) or co-transfected with pcDNA3.1/FDH vector (1 μg) and pcDNA3.1/TAM67 (1 μg) (a kind gift from Dr. Michael Birrer) using Amaxa electroporation kit ‘V’ according to the manufacturer’s directions. To allow the selection of transfected cells, 500 μg/ml of G418 (Sigma) was added to the culture 24 h post-transfection. FDH and TAM67 expression was detected by immunoblot assays.

Immunoblot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed using cell lysate prepared in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 1mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and protease inhibitor (Sigma). Cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblot with corresponding antibodies.

Antibodies

FDH was detected using in-house FDH-specific polyclonal antiserum (1:5,000); actin was detected using monoclonal antibodies (1:5000, Calbiochem). SAPK/JNK, Phos-SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), Phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), Phospho-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182), ATF-2, Phospho-ATF-2 (Thr71), c-Jun, Phospho-c-Jun (Ser63), Elk-1, Phospho-Elk-1(Ser383) were detected using antibodies from Cell Signaling Technology (1:1000). Antibody for ERK1/2, and p38 were purchased from Chemicon (1:1000).

In vitro kinase assay

In vitro assay of JNK was performed using MAP kinase assay kit (Cell Signaling Technology) according to manufacturer’s manual. Kinase activities were evaluated based on the phosphorylation of c-Jun (12) that was assessed by immunoblot with specific antibodies.

Apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was detected by Annexin-V labeling using Annexin-V-FLUOS staining kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Activities of caspase-8 and caspase- 9/6 were assayed by ApoAlert caspase assay Kit (Becton-Dickinson).

siRNA

PC-3 cells (1.4 × 106) were co-transfected with 65 nM of the siRNA duplex (targeting the sequence 5′-AAAGAAUGUCCUACCUUCU-3′ identical in JNK1 and JNK2 (55)) and 2 μg of pcDNA3.1/FDH vector using AMAXA electroporation kit ‘V’. Silencing of c-Jun was carried out in a similar manner using 75 nM of Stealth™ RNAi (Invitrogen). Two c-Jun target sequences, 5′-GCAAACCUCAGCAACUUCAACCCAG-3′ and 5′-GCAAAGAUGGAAACGACCUUCUAUG-3′, were used in these experiments with similar outcome. Scrambled Stealth™ RNAi (Invitrogen) was used as a negative control. Block-iT fluorescent oligo indicated a high efficiency of transfection. JNK1 and JNK2 or c-Jun mRNA and protein levels were evaluated by RT-PCR and immunoblot, correspondingly. Total RNA for RT-PCR was isolated using RNA Easy Protect Mini Kit (Qiagen). Reverse transcriptase reaction was performed with oligo (dT)18 primer using BD SMART™ cDNA synthesis kit (Clontech). Conventional PCR was carried out using specific primers and Pfu-Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene) as described (23).

Clonogenic assay

Colony formation by PC-3 cells after treatment with MAPK inhibitors or siRNA knock down of JNK or c-Jun were assessed 2–3 weeks FDH post-transfection. Colonies were visualized by staining with 0.2% crystal violet. The number of colonies was analyzed using Quantity One software (BioRad).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Michael Birrer for providing pcDNA3.1/TAM67 vector. This work was supported by the NIH grant CA95030.

References

- 1.Kyriakis JM, Banerjee P, Nikolakaki E, et al. The stress-activated protein kinase subfamily of c-Jun kinases. Nature. 1994;369(6476):156–60. doi: 10.1038/369156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kyriakis JM, Avruch J. Mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation. Physiol Rev. 2001;81(2):807–69. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xia Z, Dickens M, Raingeaud J, Davis RJ, Greenberg ME. Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases on apoptosis. Science. 1995;270(5240):1326–31. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weston CR, Lambright DG, Davis RJ. Signal transduction. MAP kinase signaling specificity. Science. 2002;296(5577):2345–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1073344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karin M. Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades as regulators of stress responses. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;851:139–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebisuya M, Kondoh K, Nishida E. The duration, magnitude and compartmentalization of ERK MAP kinase activity: mechanisms for providing signaling specificity. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 14):2997–3002. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu J, Lin A. Role of JNK activation in apoptosis: a double-edged sword. Cell Res. 2005;15(1):36–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weston CR, Davis RJ. The JNK signal transduction pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19(2):142–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verheij M, Bose R, Lin XH, et al. Requirement for ceramide-initiated SAPK/JNK signalling in stress-induced apoptosis. Nature. 1996;380(6569):75–9. doi: 10.1038/380075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YR, Meyer CF, Tan TH. Persistent activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1) in gamma radiation-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(2):631–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zanke BW, Boudreau K, Rubie E, et al. The stress-activated protein kinase pathway mediates cell death following injury induced by cis-platinum, UV irradiation or heat. Curr Biol. 1996;6(5):606–13. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00547-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leppa S, Bohmann D. Diverse functions of JNK signaling and c-Jun in stress response and apoptosis. Oncogene. 1999;18(45):6158–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derijard B, Hibi M, Wu IH, et al. JNK1: a protein kinase stimulated by UV light and Ha-Ras that binds and phosphorylates the c-Jun activation domain. Cell. 1994;76(6):1025–37. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90380-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bogoyevitch MA, Kobe B. Uses for JNK: the many and varied substrates of the c-Jun N-terminal kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70(4):1061–95. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00025-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bode AM, Dong Z. The functional contrariety of JNK. Mol Carcinog. 2007;46(8):591–8. doi: 10.1002/mc.20348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kallunki T, Su B, Tsigelny I, et al. JNK2 contains a specificity-determining region responsible for efficient c-Jun binding and phosphorylation. Genes Dev. 1994;8(24):2996–3007. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.24.2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta S, Barrett T, Whitmarsh AJ, et al. Selective interaction of JNK protein kinase isoforms with transcription factors. Embo J. 1996;15(11):2760–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta S, Campbell D, Derijard B, Davis RJ. Transcription factor ATF2 regulation by the JNK signal transduction pathway. Science. 1995;267(5196):389–93. doi: 10.1126/science.7824938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitmarsh AJ, Shore P, Sharrocks AD, Davis RJ. Integration of MAP kinase signal transduction pathways at the serum response element. Science. 1995;269(5222):403–7. doi: 10.1126/science.7618106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunn C, Wiltshire C, MacLaren A, Gillespie DA. Molecular mechanism and biological functions of c-Jun N-terminal kinase signalling via the c-Jun transcription factor. Cell Signal. 2002;14(7):585–93. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kyriakis JM, Avruch J. Sounding the alarm: protein kinase cascades activated by stress and inflammation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(40):24313–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ip YT, Davis RJ. Signal transduction by the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)--from inflammation to development. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10(2):205–19. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oleinik NV, Krupenko NI, Krupenko SA. Cooperation between JNK1 and JNK2 in activation of p53 apoptotic pathway. Oncogene. 2007;26(51):7222–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krupenko SA, Oleinik NV. 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase, one of the major folate enzymes, is down-regulated in tumor tissues and possesses suppressor effects on cancer cells. Cell Growth Differ. 2002;13(5):227–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oleinik NV, Krupenko SA. Ectopic expression of 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase in a549 cells induces g(1) cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1(8):577–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oleinik NV, Krupenko NI, Priest DG, Krupenko SA. Cancer cells activate p53 in response to 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase expression. Biochem J. 2005;391(Pt 3):503–11. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anguera MC, Field MS, Perry C, et al. Regulation of Folate-mediated One-carbon Metabolism by 10-Formyltetrahydrofolate Dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(27):18335–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510623200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krebs HA, Hems R, Tyler B. The regulation of folate and methionine metabolism. Biochem J. 1976;158(2):341–53. doi: 10.1042/bj1580341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brookes PS, Baggott JE. Oxidation of 10-formyltetrahydrofolate to 10-formyldihydrofolate by complex IV of rat mitochondria. Biochemistry. 2002;41(17):5633–6. doi: 10.1021/bi0120244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin DA, Siegel RM, Zheng L, Lenardo MJ. Membrane oligomerization and cleavage activates the caspase-8 (FLICE/MACHalpha1) death signal. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(8):4345–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duesbery NS, Webb CP, Leppla SH, et al. Proteolytic inactivation of MAP-kinase-kinase by anthrax lethal factor. Science. 1998;280(5364):734–7. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5364.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corvol JC, Valjent E, Toutant M, et al. Depolarization activates ERK and proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (PYK2) independently in different cellular compartments in hippocampal slices. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(1):660–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411312200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Domann FE, Levy JP, Birrer MJ, Bowden GT. Stable expression of a c-JUN deletion mutant in two malignant mouse epidermal cell lines blocks tumor formation in nude mice. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5(1):9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oleinik NV, Krupenko NI, Reuland SN, Krupenko SA. Leucovorin-induced resistance against FDH growth suppressor effects occurs through DHFR up-regulation. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurinna SM, Tsao CC, Nica AF, Jiffar T, Ruvolo PP. Ceramide promotes apoptosis in lung cancer-derived A549 cells by a mechanism involving c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase. Cancer Res. 2004;64(21):7852–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang Y, Hutter D, Liu Y, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 suppresses serum deprivation-induced death of A549 cells through differential effects on c-Jun and JNK activities. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(24):18234–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909431199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levine AJ. p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell. 1997;88(3):323–31. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghosh J. Inhibition of arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase triggers prostate cancer cell death through rapid activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;307(2):342–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoneda K, Furukawa T, Zheng YJ, et al. An autocrine/paracrine loop linking keratin 14 aggregates to tumor necrosis factor alpha-mediated cytotoxicity in a keratinocyte model of epidermolysis bullosa simplex. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(8):7296–303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307242200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim HJ, Lee KW, Kim MS, Lee HJ. Piceatannol attenuates hydrogen-peroxide- and peroxynitrite-induced apoptosis of PC12 cells by blocking down-regulation of Bcl-XL and activation of JNK. J Nutr Biochem. 2008;19(7):459–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liedtke C, Lambertz D, Schnepel N, Trautwein C. Molecular mechanism of Mitomycin C-dependent caspase-8 regulation: implications for apoptosis and synergism with interferon-alpha signalling. Apoptosis. 2007;12(12):2259–70. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fuchs SY, Dolan L, Davis RJ, Ronai Z. Phosphorylation-dependent targeting of c-Jun ubiquitination by Jun N-kinase. Oncogene. 1996;13(7):1531–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adler V, Franklin CC, Kraft AS. Phorbol esters stimulate the phosphorylation of c-Jun but not v-Jun: regulation by the N-terminal delta domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(12):5341–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shifrin VI, Anderson P. Trichothecene mycotoxins trigger a ribotoxic stress response that activates c-Jun N-terminal kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and induces apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(20):13985–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.13985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sah NK, Munshi A, Kurland JF, McDonnell TJ, Su B, Meyn RE. Translation inhibitors sensitize prostate cancer cells to apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) by activating c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(23):20593–602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211010200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Potapova O, Anisimov SV, Gorospe M, et al. Targets of c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase 2-mediated tumor growth regulation revealed by serial analysis of gene expression. Cancer Res. 2002;62(11):3257–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang YM, Bost F, Charbono W, et al. C-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase mediates proliferation and tumor growth of human prostate carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(1):391–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Edmunds JW, Mahadevan LC. MAP kinases as structural adaptors and enzymatic activators in transcription complexes. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 17):3715–23. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stanciu M, DeFranco DB. Prolonged nuclear retention of activated extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase promotes cell death generated by oxidative toxicity or proteasome inhibition in a neuronal cell line. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(6):4010–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104479200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao D, Singh SV. Phenethyl isothiocyanate-induced apoptosis in p53-deficient PC-3 human prostate cancer cell line is mediated by extracellular signal-regulated kinases. Cancer Res. 2002;62(13):3615–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xiao D, Choi S, Johnson DE, et al. Diallyl trisulfide-induced apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells involves c-Jun N-terminal kinase and extracellular-signal regulated kinase-mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2. Oncogene. 2004;23(33):5594–606. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu C, Shen G, Yuan X, et al. ERK and JNK signaling pathways are involved in the regulation of activator protein 1 and cell death elicited by three isothiocyanates in human prostate cancer PC-3 cells. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(3):437–45. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu C, Yuan X, Pan Z, et al. Mechanism of action of isothiocyanates: the induction of ARE-regulated genes is associated with activation of ERK and JNK and the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of Nrf2. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(8):1918–26. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sanchez AM, Malagarie-Cazenave S, Olea N, Vara D, Chiloeches A, Diaz-Laviada I. Apoptosis induced by capsaicin in prostate PC-3 cells involves ceramide accumulation, neutral sphingomyelinase, and JNK activation. Apoptosis. 2007;12(11):2013–24. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0119-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li G, Xiang Y, Sabapathy K, Silverman RH. An apoptotic signaling pathway in the interferon antiviral response mediated by RNase L and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(2):1123–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305893200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]