Abstract

Background

The low recurrence rate and tissue sparing benefit associated with Mohs micrographic surgery requires accurate interpretation of frozen sections by the Mohs surgeon.

Objective

To assess concordance between dermatopathologists and Mohs surgeons when reporting cutaneous malignancy in the Mohs surgery setting.

Methods

This study is a retrospective analysis of 1,156 slides submitted over 10 years as part of a pre-existing randomized, blinded, quality assurance protocol. Slides were read by one of five dermatopathologists and represent cases from three Mohs surgeons and five Mohs fellows. Agreement or disagreement was recorded.

Results

Of the 1,156 slides, 32 slides (2.8%) were disparate. Aside from differences regarding intra-epidermal neoplasia, the concordance rate was 99.7%.

Limitations

This study represents data collected at a single institution in the United States alone.

Conclusion

There was statistically significant concordance between Mohs surgeons and dermatopathologists in frozen section interpretation in the Mohs surgery setting. Discordance was primarily related to the interpretation of in situ malignancy.

More than one million cases of squamous cell (SCC) and basal cell carcinoma (BCC) occur annually in the United States1 with an increasing incidence in men and women under the age of 40.2 Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) provides tissue-sparing treatment of cutaneous neoplasms with a cure rate of 99% for primary BCCs and 97% for primary SCCs.3

The success rate of this procedure is dependent on accurate microscopic evaluation of carefully mapped specimens. The Mohs surgeon acts as pathologist and is therefore able to translate abnormal findings on the tissue map into appropriate sequential tumor removal.4 A critical component of the technique is the surgeon’s skill in interpreting histologic specimens, and yet no studies have analyzed Mohs surgeons’ capacity to read frozen sections compared to pathologists trained in dermatology.

Anatomic and surgical pathology units in the United States employ a quality assurance protocol that is recommended by the Association of Directors of Anatomic and Surgical Pathology.8 Peer review is considered the gold standard for judging diagnostic accuracy and the Association supports the review of randomly selected cases within a department for such examination.9 Similarly, a quality assurance program was developed in 1994 in the Section of Dermatologic Surgery and Cutaneous Oncology at the Yale School of Medicine where MMS is performed. In order to evaluate the reliability of frozen section interpretation rendered by the MMS surgeons, a decade of retrospective data from this quality assurance program was analyzed.

Methods

In the Yale Section of Dermatologic Surgery and Cutaneous Oncology, during the Mohs procedure, frozen sections were processed by trained histotechnicians, stained with hematoxylin and eosin and then reviewed by the Mohs surgeon. The surgeon reviewed the slides of each stage in concert with systematic tissue mapping and determined whether additional surgical excision should be performed. This project was granted an exemption by the Human Investigation Committee at Yale University (HIC number 0708002945).

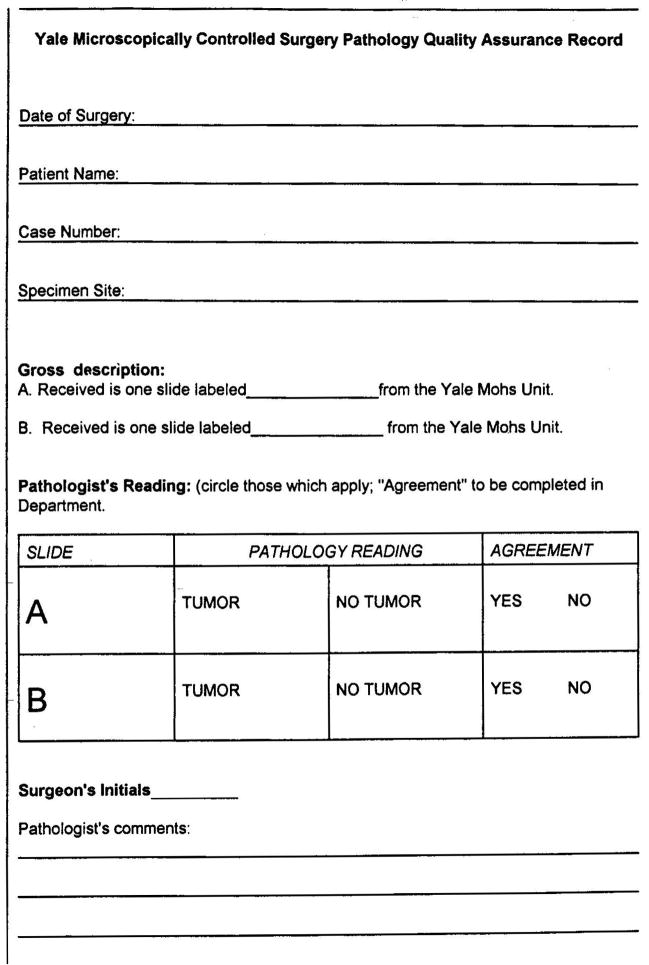

In the quality assurance program, the Mohs histotechnicians selected on average two slides from Mohs cases per surgeon per week at random. The histotechnicians were not aware of the type of tumor present on the slide when submitting them for quality assurance. The histotechnician selecting the slide recorded presence of “tumor” or “no tumor” in a binary system based on the documented findings of the Mohs surgeon as noted on the intraoperative Mohs map. Hence, the MMS surgeon was blinded as to which slides were reviewed in the quality assurance program. The selected slides were then sent for analysis to the Yale Section of Dermatopathology. After submission, the slide diagnosis of “tumor” or “no tumor” was similarly recorded by the dermatopathologists who were blinded to the MMS surgeon’s interpretation. The interpretation of each slide was recorded on a standardized quality assurance form which was kept on file in the MMS laboratory (Figure 1). The nature of the quality assurance form precluded descriptive annotations.

Figure 1.

Quality assurance form used as part of the quality assurance protocol in the Section of Dermatologic Surgery and Cutaneous Oncology at the Yale School of Medicine. Note the binary nature of the quality assurance form which precludes descriptive annotations by the slide interpreter however allows the pathologist and MMS surgeon to note resolution of any discrepancy under “Pathologist’s comments.”

A retrospective analysis was performed on 1,156 slides consecutively reviewed in the quality assurance program between 1996 and 2005. Histopathologic interpretation was performed by one of three Mohs surgeons or one of five Mohs fellows under the supervision of a Mohs surgeon. The slides were prepared using standard Mohs histotechnical procedures and were reviewed by a surgeon at the time of the procedure and within one week by one of five dermatopathologists.

The findings were converted into a data set using Microsoft Excel, and tumor type of each slide was also recorded in this data set. If discord occurred, the histotechnicians receiving the quality assurance form alerted the MMS surgeon who then reviewed the slides with the dermatopathologist and reviewed the patient record to assure appropriate care was provided. Documentation of this review was noted on the quality assurance form and included in the data.

The Mohs surgeons participating in the program all completed residency training in dermatology and fellowship training in Mohs surgery, with a range of experience of one to 20 years in practice. None of the Mohs surgeons completed a dermatopathology fellowship. The five dermatopathologists participating in the quality assurance program each completed training in anatomical and surgical pathology followed by fellowship in dermatopathology.

Results

A database of MMS surgeon and dermatopathologist readings was compiled, representing 1,156 slides sampled on a regular interval (in most cases weekly) from 1996 to 2005. In total, these slides represented removal of 582 basal cell carcinomas, 542 squamous cell carcinomas, and 31 tumors classified as “other” which represent nonmelanoma skin cancers treated by Mohs (6 dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, 6 atypical fibroxanthomas, 4 hypertrophic actinic keratoses suspicious for squamous cell carcinoma at the base, 2 microcystic adnexal carcinomas, 2 desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas, 1 actinic cheilitis refractory to other treatment modalities and 11 slides for which tumor type was not recorded on the quality assurance sheet including 2 of clear cell morphology). Of the BCC cases, 68 were recurrent, 12 were morpheaform, 10 exhibited features of SCC, and two were pigmented. Of the SCC cases, 86 were in situ (SCC-IS), 17 were recurrent, four were keratoacanthoma-type and two were acantholytic SCC. Since slides were sent at random, these samples represented tumor as well as clear stages. After consensus agreement between the dermatopathologist and the Mohs surgeon was reached on all slides, a total of 387 slides (33.5%) contained tumor.

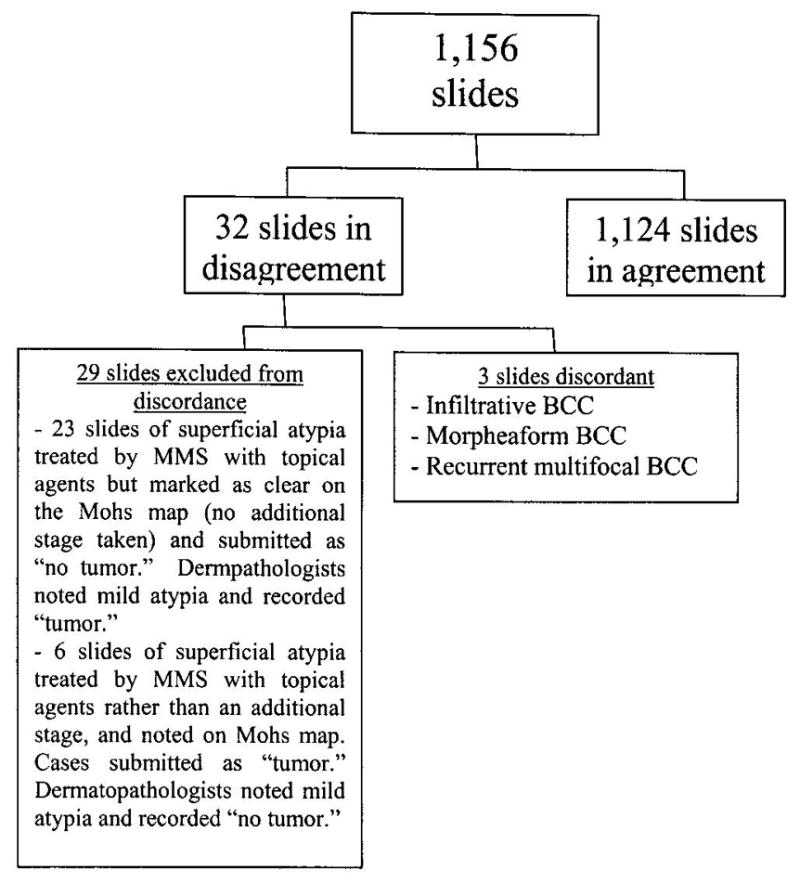

Of the 1,156 slides analyzed by both dermatopathologists and Mohs surgeons, 32 slides (2.8%) were initially read disparately (Figure 2). Of these 32 discordant slides, 21 (1.9% of total slides, 65.6% of discordant slides) were diagnosed as actinic keratoses (AK) or SCC-IS and eight (0.7% of total slides, 25% of discordant slides) contained foci of superficial basal cell carcinomas. In 29 of the 32 cases, the dermatopathologists marked “tumor” in 23 cases. An additional six cases were submitted by the Mohs histotechnicians and recorded as“tumor” based on the Mohs map, which highlights the binary quality assurance program. In other words, in the 23 cases read as containing “tumor” by the dermatopathologists, the Mohs map reflected a “clear” stage since in each of these cases, the Mohs surgeon noted the pathology but made the clinical decision to manage the underlying or residual disease using another modality rather than taking an additional stage. In the six cases submitted as “tumor” by the histotechnicians, who were working within the limits of the binary quality assurance protocol form, the Mohs map noted superficial atypia which the Mohs surgeon chose to treat with topical agents rather than taking another stage. As a result, the 29 cases were excluded from analysis as they do not represent true discordance. Of the three remaining discordant slides (0.3% of total slides, 9.4% of discordant slides), all three cases were read by the MMS surgeon as being suspicious for tumor but read as containing “no tumor” by the dermatopathologists. These three were cases of infiltrative BCC, morpheaform BCC and recurrent multifocal BCC. Therefore, after further review and analysis of the nature of the disagreements, the concordance rate regarding clinically significant decisions was 99.7% (n=1,153).

Figure 2.

1,156 slides were analyzed in an ongoing quality assurance program. Of the total number of slides, only three were considered to be truly discordant. Of the 32 slides in disagreement, 29 slides were in discordance simply due to the binary nature of the quality assurance sheet and thus were excluded from the discordant analysis.

Discussion

The quality assurance data for interpretation of Mohs histopathology specimens in the Yale Section of Dermatologic Surgery and Cutaneous Oncology demonstrated an overall concordance rate of 99.7% between MMS surgeons and dermatopathologists. There was 96.1% concordance among cases of SCC and 99.5% concordance in cases representing BCC. Importantly, cases where disagreement occurred were along the diagnostic spectrum represented by AK and SCC-IS, which has long been a topic of debate within the field of dermatopathology itself.10,11 This underscores the histopathologic challenge of distinguishing changes along the actinic damage spectrum. Because non-melanoma skin cancer, in the vast majority of cases is excised in solar damaged tissue, the discrepancies occurred in an area of pathologic evaluation consistent with the underlying disease process. The data thus suggest that a well-trained MMS surgeon is capable of accurately interpreting tumors histologically in the therapeutic setting. The reading of an AK or SCCIS in cases of SCC was anticipated as the Mohs surgeon is not only acting as a pathologist, but combines that task with the role of clinician who needs to incorporate other clinical data such as skin type and solar exposure into the decision-making process. Examination of the patient alone or the slides alone does not allow for this clinico-pathologic correlation which makes MMS uniquely different from any other tumor extirpation surgical technique.

In the three cases considered to contain tumor by the MMS surgeon but not the dermatopathologists, the nature of the malignancy clinically warranted additional excision and thus insured that no tumor was left behind due to misinterpretation of these slides. However, an additional and perhaps unnecessary Mohs stage was taken in each of these three cases leading to a larger defect that was then repaired.

A review of the literature shows no standard for reader reliability for BCC or SCC-IS in cases of SCC. The 21 cases of AK and SCC-IS demonstrate the well established intra-observer variability in reporting12 and is consistent with the discord among pathologists with various forms of actinic keratosis.

Although other authors have attempted to correlate13–15 the accuracy of Mohs sections through retrospective review of tissue sections, none has analyzed an ongoing quality assurance program spanning 10 years. Grabski et al. reviewed their quality assurance program at Brooke Army Medical Center involving 1,000 consecutive cases over a one year period and found an index of agreement of 98.9%.16 This study thus represents the only analysis of concordance using slides selected at random interpreted by both dermatopathologists and Mohs surgeons over such a time period. The 99.7% degree of concordance validates the Mohs surgical technique as a highly reliable means of histopathology-guided cancer extirpation.

Conclusion

In the final evaluation of 1,156 slides, 23 of 32 disparate interpretations resulted from dermatopathologists’ evaluation of actinic damage or in situ malignancy at the Mohs margins of invasive malignancy and an additional six disparate interpretations were a result of limitations of the binary system of the quality assurance program which does not allow for the listing of actinic keratosis. Understanding the histopathology in relation to the patient’s malignancy and in view of their individual solar damage is a challenge to the MMS surgeon who must make an immediate clinical decision. This is reflected in the three cases where the MMS surgeon erred on the side of caution, taking additional tissue in cases of infiltrative, morpheaform and recurrent multifocal BCC. It is also instructive that the MMS surgeons recognized keratinocyte atypia in all 29 cases and treated appropriately.

Our data suggests a 99.7% concordance rate in Mohs specimen interpretation between dermatopathologists and Mohs surgeons in our center. This level of concordance is consistent with that which is reported between and within anatomic pathologists and dermatopathologists when diagnosing non-melanoma malignancy in skin.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the participation of dermatopathologists Jennifer M. McNiff, MD, Rossitza Lazova, MD, Shawn Cowper, MD and Antonio Subtil, MD and MMS surgeon Samuel Book, MD in this study.

Funding sources: KM was supported by an NIH post-doctoral research fellowship (2 T32 AR007016-32).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The data in this article has been presented at the Mohs College 2007 Annual Meeting in Naples, Florida May 3–6, 2007.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. [Accessed February 11, 2007];Cancer Facts & Figures 2007. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/CAFF2007PWSecured.pdf.

- 2.Christenson LJ, Borrowman TA, Vachon CM, Tollefson MM, Otley CC, Weaver AL, et al. Incidence of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas in a population younger than 40 years. JAMA. 2005;294:681–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip: implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:976–90. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGovern TW, Leffell DJ. Mohs Surgery: the informed view. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1255–9. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.10.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohs FE. Chemosurgery. Clinics in Plastic Surgery. 1980;7:349–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohs FE. Microscopically controlled surgery for skin cancer. Springfield (IL): Charles C. Thomas; 1978. Chemosurgery. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swanson NA, Grekin RC, Baker SR. Mohs surgery: techniques, indications, and applications in head and neck surgery. Head & Neck Surgery. 1983;6:683–92. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890060209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Association of Directors of Anatomic and Surgical Pathology. Recommendation on quality control and quality assurance in anatomic pathology. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:1007–9. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199110000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Association of Directors of Anatomic and Surgical Pathology. Recommendations for Quality Assurance and Improvement in Surgical and Autopsy Pathology. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1469–71. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213303.13435.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones RE. Questions to the editorial board and other authorities. What is the boundary that separates a thick actinic keratosis from a thin squamous-cell carcinoma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:301–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ackerman AB. Solar keratosis is squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1216–7. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.9.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khanna M, Fortier-Riberdy G, Dinehart SM, Smoller B. Histopathologic evaluation of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: Results of a survey among dermatopathologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:721–6. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner RJ, Leonard N, Malcom AK, Lawrence CM, Dahl MGC. A retrospective study of outcome of Mohs’ micrographic surgery for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma using formalin fixed section. Br J of Dermatol. 2000;142:752–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smeets NWK, Kuijpers DIM, Nelemans P, Ostertag JU, Verhaegh MEJM, Krekels GAM, et al. Mohs’ micrographic surgery for treatment of basal cell carcinoma of the face – results of a retrospective study and review of the literature. Br J of Dermatol. 2004;151:141–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell RM, Barrall D, Wilkel C, Robinson-Bostom L, Dufresne RG. Post-Mohs micrographic surgical margin tissue evaluation with permanent histopathologic sections. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:655–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grabski WJ, Salasche SJ, McCollough ML, Berkland ME, Gutierrez JA, Finstuen K. Interpretation of Mohs micrographic frozen sections: A peer review comparison study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:670–4. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]