Abstract

Carbohydrate craving, the overwhelming desire to consume carbohydrate-rich foods in an attempt to improve mood, remains a scientifically controversial construct. We tested whether carbohydrate preference and mood enhancement could be demonstrated in a double-blind, placebo-controlled self-administration trial. Overweight females who met strict operational criteria for carbohydrate craving participated in two three-day discrete choice trials over a two-week period. Participants reported their mood before and at several time points after undergoing a dysphoric mood induction and ingesting, under double-blind conditions, either a carbohydrate beverage or a taste-matched protein-rich nutrient balanced beverage. Every third testing day, participants were asked to self-administer the beverage preferred based on its previous mood effect. Results showed that, when rendered mildly dysphoric, carbohydrate cravers chose the carbohydrate beverage significantly more often than protein-rich beverage and reported that carbohydrate produced greater mood improvement. The carbohydrate beverage was perceived as being more palatable by the carbohydrate cravers, although not by independent taste testers who performed the pre-trial taste matching. Results support the existence of a carbohydrate craving syndrome in which carbohydrate ingestion medicates mildly dysphoric mood.

Keywords: carbohydrate craving, self-administration, self-medication, obesity

Introduction

The carbohydrate craving syndrome is often defined as a disorder of disturbed appetite and mood, characterized by an almost irresistible desire to consume sweet or starchy foods in response to negative mood states (Wurtman, 1990). Carbohydrate ingestion appears to trigger mood improvement in the carbohydrate craver (Lieberman, Wurtman, & Chew, 1986; Rosenthal et al., 1989) while non-carbohydrate cravers generally report fatigue after carbohydrate ingestion (Spring, Lieberman, Swope, & Garfield, 1986; Spring, Maller, Wurtman, Digman, & Cozolino, 1982–3). Accordingly, it is theorized that the carbohydrate craver preferentially selects and self-administers carbohydrate-rich foods in an attempt to self-medicate negative mood (Liebenluft, Fiero, Bartko, Moul, & Rosenthal, 1993; Wurtman & Wurtman, 1995). Mood improvement following carbohydrate ingestion is thought to occur via a tryptophan-mediated increase in brain serotonin (Gendall & Joyce, 2000; Sayegh et al., 1995; Velasquez-Mieyer et al., 2003; Wurtman & Wurtman, 1995) potentially alleviating a functional deficiency in brain serotonin and thus serving as self-medication (Pijl et al, 1993; Spring, Chiodo & Bowen, 1987; Wurtman, 1990; Wurtman & Wurtman, 1995).

The carbohydrate craving construct remains controversial, however, with many earlier studies supporting the theory criticized on the grounds of methodology and interpretation. A major difficulty in the research literature on carbohydrate craving has been the absence of a standardized, reliable operational definition of both carbohydrate foods and the carbohydrate craving construct itself (Drewnowski 1987; Fernstrom, 1988; Lieberman, Wurtman & Chew, 1986). Moreover, a significant design flaw in many studies has been that the high-carbohydrate and high-protein foods being compared have differed in hedonic and sensory value as well as macronutrient content (e.g. cookies vs beef jerky), with the carbohydrate options perceived as being more hedonically appealing. Consequently, a competing theory posits that greater preference for carbohydrate results from the higher sweet and/or fat content of such carbohydrate foods (Drewnowski, 1987; Drewnowski, Kurth, Holden-Wiltse & Saari, 1992; Fernstrom, 1988). A final important, albeit smaller, design flaw has been the failure to standardize the timing of testing in relation to the menstrual cycle in female participants. Menstrually-related effects on mood, appetite, and food craving are well-documented (Lieberman, Wurtman & Chew, 1986; Lissner, Stevens, Levitsky, Rasmussen & Strupp, 1988) and represent a potential confound to the study of macronutrient effects on mood.

There have also been some failures to replicate the finding that carbohydrate intake acutely improves mood in carbohydrate cravers (Christensen & Redig, 1993; Gendall, Joyce, & Abbott, 1999; Toornvliet et al., 1997) even in the presence of food choices that had been equated for taste and hedonic appeal (Toornvliet et al., 1997). In most studies, carbohydrate effects on mood were assessed in the presence of repeated blood draws. In this case, there is a likelihood that conditioned aversion responses to venipuncture (Redd et al., 1991) overrode any potential dietary effects on mood.

Given these methodological challenges, it remains unclear whether the carbohydrate craving self-medication theory remains viable or clinically useful. However, given that (a) many people attribute their weight management difficulties to carbohydrate craving, (b) carbohydrate craving has been associated with increased weight (Spring, Pingitore, & Zaragoza, 1997; Wurtman, 1987; Wurtman & Wurtman, 1995); (c) there is an epidemic of overweight and obesity in the United States (Mokdad et al., 2000) and (d) carbohydrate craving appears to be a predictor of poor response to weight loss treatment (Bray, York, & DeLany, 1992; Goodrick & Foreyt, 1991; Sitton, 1991), the need is heightened to understand mechanisms associated with overweight as well as difficulties with weight loss and weight loss maintenance (Yanovski, 2003).

The aim of this study was to test the validity of the carbohydrate craving construct by evaluating whether carbohydrate preference and subsequent mood improvement could be objectively demonstrated under double-blind conditions in a sample of overweight women who self-identified as carbohydrate-cravers and met strict operational criteria for carbohydrate craving. Hypotheses were that when rendered dysphoric and given a choice between hedonically, palatability and calorically-matched novel beverages, carbohydrate cravers will (1) self-administer a carbohydrate-rich, protein-free beverage in preference to a beverage that balances carbohydrate and protein; and (2) report greater mood elevation after consuming the carbohydrate beverage as compared to the protein-rich nutrient-balanced beverage.

Methods

Overview of Study Design

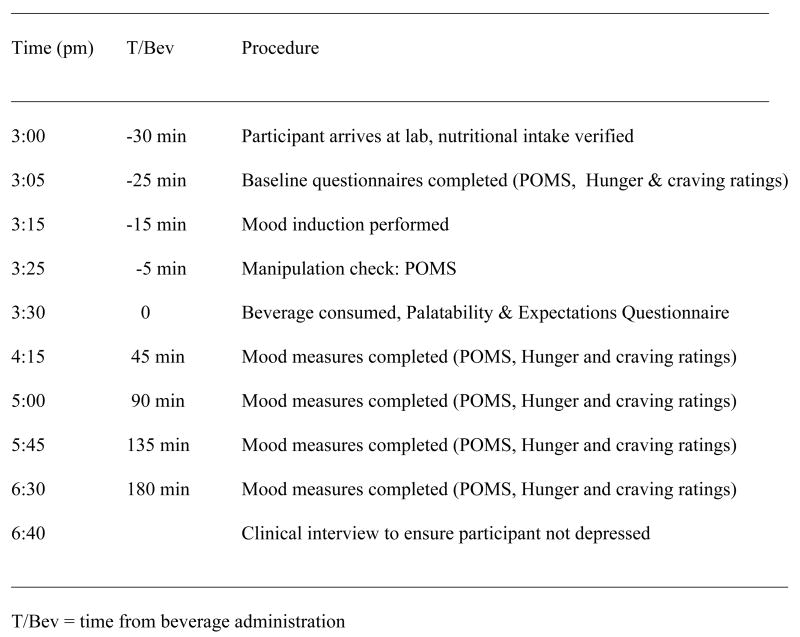

A repeated measures, double-blind self-administration protocol (based on a discrete trials choice paradigm) was used to test the carbohydrate self-administration construct. Participants meeting our stringent criteria for carbohydrate craving were told they would participate in a 2-week trial designed to study the effects of two novel beverages on mood. Two taste-matched beverages, one pure carbohydrate, one protein-rich but nutrient balanced were administered across two sets of three day discrimination trials, just after participants underwent a dysphoric mood induction. The discrete trials chart is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequence of testing days

| Test day | Trial | |

|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | 1 (Monday) | Exposure A |

| 2 (Tuesday) | Exposure B | |

| 3 (Wednesday) | Choice | |

| Week 2 | 4 (Monday) | Exposure B |

| 5 (Tuesday) | Exposure A | |

| 6 (Wednesday) | Choice |

Mood, hunger, and cravings were assessed for a period of three hours after macronutrient ingestion. All participants provided informed consent to participate in the study and were paid 150.00 for completing the protocol. This protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science and the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Participants

Potential participants were women from the Chicagoland area who responded to advertisements soliciting overweight women who crave sweet or starchy foods. Eligibility criteria required that participants were female, age 20–45, overweight, and met our stringent criteria for carbohydrate craving. Candidates were excluded from the study if they had diabetes, thyroid disease, anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa, a recent weight loss >5%, currently used antidepressants, anti-anxiety agents or other medications that might affect mood or appetite, or had an active drug or alcohol abuse problem in the past year. Also excluded were candidates who were pregnant, lactating, perimenopausal, or had undergone hysterectomy. A total of 80 women were initially screened for the study; the most frequent reason for study ineligibility was a higher BMI than specified in the protocol.

Eligibility screening

Prospective participants were screened by telephone to evaluate initial carbohydrate craving criteria, ascertain inclusion/exclusion criteria, and to appraise the study candidates’ willingness to complete the entire six-session trial. If initial entry criteria were met, participants were invited to the study location for two eligibility screening sessions. At the first session, each participant was weighed and height measured using a professional balance beam scale. Body mass index (BMI) was computed (weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) to determine that the participant met the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 1995) definition of overweight (BMI 25.1–29.9). Women in the overweight rather than obese category were studied in order to standardize macronutrient and calorie doses within the study. Psychopathology and eating disorder symptomatology was assessed using The Eating Disorder Inventory-2 (EDI-2; Garner, 1991), the Beck Depression Inventory-2 (BDI-2; Beck, Steer & Brown, 1996) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1994).

Each participant was asked to record descriptions of several “sad” autobiographical memories (for example, my parents telling me they were getting divorced), rating each memory on a scale of 1–10 to indicate the vividness of the memory and how sad/upset it made them feel. Three memories of approximately equal affective intensity and imaginal vividness (both scores ≥ 7) were selected for use in the dysphoric mood induction. Finally, participants were trained by a dietitian in the use of a 7-day diet record using food models, photographs of foods, and a food scale. Participants were trained to record intake immediately after eating and to describe ingredients, methods of food preparation, and portion sizes, as well as mood at each eating period. Participants recorded dietary intake for 7 days between days 7–21 of the menstrual cycle.

Carbohydrate craver criteria

Carbohydrate craving was defined as: (1) afternoon or evening urge to eat sweet or starchy foods at least four times per week; (2) afternoon or evening carbohydrate snacking (defined as foods eaten between meals that have a carbohydrate to protein ratio ≥ 6:1 at least four times per week (Yokogoshi & Wurtman, 1986) and corroborated by contemporaneous diet records; and (3) carbohydrate craving occurs in conjunction with dysphoria which is subsequently relieved by carbohydrate snacking. These criteria were developed based on critical evaluation that suggested that previous studies lacked both specificity for carbohydrate and objective assessment of carbohydrate intake (Drewnowski, 1987; Fernstrom, 1988), and did not include a measure of mood changes that are reported to accompany carbohydrate consumption (Wurtman, 1987).

To verify that each subject met objective criteria for carbohydrate craving, food intake data was analyzed by the Food Processor Version 5 nutrient analysis program (1992), which provided a nutritional breakdown of each day's diet, including micro- and macronutrient content, alcohol, and caffeine. This analysis was used to ensure that each participant demonstrated both reliable craving for carbohydrate and elevated near-pure carbohydrate intake (with less than 6% protein to avoid blocking the purported tryptophan-mediated mechanism of action; Teff et al., 1989), in the form of snacks at least four times per week, concurrent with dysphoric mood.

Protocol Measures

The Profile of Mood States (POMS; McNair, Lorr, & Droppleman, 1971) is a 65-item questionnaire that yields scores for tension, depression, anger, vigor, fatigue, and confusion. The POMS was used to enhance comparison and evaluate the consistency of findings with other studies of carbohydrate effects on mood. The composite dysphoria score (depression + tension + anger) has a possible score range of 0–144; the average dysphoria score for non-depressed, non-smokers is 6.5 (9.5) (Spring et al., 2007).

Expectations Questionnaire

Participants completed 10-point scales to indicate their expectations of how the drink will affect their mood (1=not at all, 10=extremely). Ratings were made of anticipated changes in anxiety, tension, depression, anger, fatigue, sleepiness, and vigor.

Beverage Palatability

Participants rated the palatability of the beverage using a 10-point scale (1=not palatable, 10=very palatable). Although the beverages had been normatively equated for taste, texture, and consistency, this measure assessed whether palatability matching was achieved for each individual participant.

Craving inventory

To determine whether the dysphoria induction was associated with food cravings, participants completed a 15-item craving inventory (modified from Sayegh et al., 1995) immediately post mood induction. The craving inventory required the participant to rate on a 10-point scale (1=not at all, 10=extremely) the degree of craving for (urge to eat) a variety of foods, including candy, potato chips, chocolate, ice cream, pastry, meat, cheese, yogurt, bread/pasta, fruits, and vegetables. The Craving Inventory has demonstrated reliability and validity in a study that assessed the effect of macronutrients on food cravings (Sayegh et al., 1995). The inventory was modified to include a rating of current hunger level on the same 10-point scale.

Test Beverages

The beverages were taste-matched (fruit punch) and calorie-matched (400 kcal), differing only in macronutrient content. The carbohydrate-rich, protein-poor beverage, Carboforce (manufactured by American Body Building Association) contained 100 grams of complex and simple carbohydrates, 0 grams of protein, and 0 grams of fat. The protein-rich, balanced nutrient beverage, Aminoforce (also manufactured by American Body Building Association) contained 22 grams of protein, 75 grams of carbohydrate, and 0 grams of fat. The protein-rich, balanced nutrient beverage was selected to simulate other real world food choices that would not have an effect on the putative neuromechanism for mood improvement following carbohydrate ingestion. As part of the study development beverage selection process, a panel of taste testers evaluated the two beverages side by side and rated them equivalent in flavor and palatability.

Testing procedure

To standardize pre-study calorie and macronutrient intakes, which could influence later macronutrient effects, participants were provided with standard packaged meals to be eaten with one serving of fruit (approximating their usual caloric intake) approximately 4 hours before participating in the trial. A four-hour window assures that subjects are in a fasting state relative to blood glucose levels (Christensen & Redig, 1993; Guyton, 1986). The study was conducted on Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays across two consecutive weeks. Standardized hormonal effects on mood, appetite, and carbohydrate craving was achieved by placing the testing sessions between day 7–21 of the menstrual cycle for each participant.

On each of the six study days, the participant reported to the lab at 3 pm. After verifying that the standardized meal had been consumed as directed, baseline measures of mood (POMS) and hunger were administered. Negative mood was induced by invoking one of the previously provided negative autobiographical accounts while listening to a musical negative mood induction (Albinoni’s Adagio in G minor, Prokofiev’s Russia under the Mongolian Yoke), music which has been shown to reliably induce dysphoric mood (Clark & Teasdale, 1985; Martin, 1990). The dysphoric mood induction, which combined autobiographic sad memories with sad music, was specifically designed for this study and has established efficacy across repeated testing sessions (Hernandez, Vander Wal, and Spring, 2003). Participants listened to the following instructions for the mood induction:

“As you can hear, there is music playing in the background. The music is to help you attain an unpleasant mood state. I’d like you to close your eyes, listen to the music, and try to remember the time when … [sad memory prompted, e.g. your parents told you they were getting divorced]. Try to really intensely get into the feelings of the music and your memory. It’s very important that you try to develop an unpleasant mood state that is as intense and as real as you can possibly make it. I want to remind you that we have a procedure to bring your mood back up to normal at the end of this experiment. So don’t be afraid to really intensely get into this mood.“

Mood was re-assessed via POMS post-mood induction to ensure that a dysphoric mood had been achieved. The subject was served a macronutrient beverage in an opaque covered cup to drink within 10 minutes. On one day of the week (e.g. Monday) the participant was served the carbohydrate beverage, on the other, she was served the protein-rich, nutrient-balanced beverage (e.g. Tuesday). The order of beverage administration was counterbalanced across subjects and days to eliminate order effects. Immediately after consuming the beverage, palatability and expectation ratings were completed. On the third day (Wednesday, the “test” day), the protocol was identical except that the participant was presented with both beverages and was asked to choose the preferred beverage, based on how it made her feel in the earlier exposure. All other aspects of the protocol were identical to the previous testing days.

Mood (POMS) and hunger and craving ratings were assessed at baseline, immediately post-mood induction, and 45, 90, 135, and 180 minutes after the consumption of each nutrient beverage. All assessments were written participant self-reports distributed and collected by research assistants who were blind to the macronutrient content of that day’s beverage. A clinical interview was administered at the end of the three hour trial to ensure the participant did not leave in a depressed state. The protocol timeline is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Protocol Timeline

Results

Participant characteristics

Participants were 21 moderately overweight females (BMI M=27.7, SD=2.4) the majority of whom were Caucasian (65%), with a mean age of 28.2 years (SD=8.4) who had completed, on average, just over two years of college (M=14.3 years, SD= 2.1). Although a small sample size, our power analysis suggested that this sample size would sufficiently power the study to detect a medium effect size in mood change and beverage discrimination. Nutrient analysis of diet records revealed that, consistent with self-reported carbohydrate craving and elevated carbohydrate intake, participants consumed the majority of their daily snack calories in the form of carbohydrate (M=619 kcals, SD=75.2) and consumed a large proportion of their overall calories as carbohydrates (M=1419 kcals, SD=150.2) similar to other studies of carbohydrate cravers (Wurtman, 1987). In most cases, participants snacked far more often than the minimal of 4 days required by the protocol. At screening, participants reported minimal symptoms of depression (BDI-II range 0–19, M = 3.4, SD=6.2). Two participants reported symptoms of mild depression, five subjects reported a history of depression, and three subjects reported symptoms consistent with binge eating disorder.

Self-administration of carbohydrate versus protein

We predicted that participants would self-administer the carbohydrate beverage significantly more often than would be expected by chance and significantly more often than the high protein balanced nutrient beverage. Descriptive statistics revealed that 81% (17) of participants chose the carbohydrate beverage on their first choice day and 67% (14) selected it on their second choice day. Fifty three percent of the participants (11) chose the carbohydrate beverage on both choice days. Only 9% (2) never chose the carbohydrate beverage.

Chi square analysis revealed that a significantly greater number of participants chose the carbohydrate beverage at both choice opportunities versus the high protein, nutrient-balanced beverage at both opportunities or high protein nutrient balanced once and carbohydrate once [χ2 (1, n=21) = 8.77, p <.01]. Even though blind to the nutrient content, carbohydrate cravers chose to self-administer carbohydrate significantly more often than the taste- and calorically-matched protein-rich nutrient balanced alternative.

Manipulation check

The effect of the mood manipulation was analyzed via repeated measures ANOVA with POMS dysphoria as the dependent variable and time (baseline and manipulation check) and day (1,2,3,4,5,6) as repeated measures. The mood induction significantly increased dysphoria at the manipulation check across all testing days by an average of 17.8 (sd 11.6) [F(1,20) = 54.1, p<.001] indicating that the mood induction was both successful and reliable. Dysphoria at manipulation check was significantly associated with increased carbohydrate craving (for sweets) across all testing days (r=.59, p<.01), but was not associated with increased hunger (r=.11, p=.64).

Mood effects of carbohydrate versus protein

Data from exposure trials were analyzed via repeated measures ANOVA. POMS dysphoria and vigor were chosen a priori as dependent measures. Beverage (carbohydrate vs protein-rich, balanced nutrient), week (1 vs. 2) and time (baseline, manipulation check, 90 and 135 minutes) were repeated measures factors. The 90 and 135 minute post-beverage assessments were used in the model, according to our a priori hypothesis which was based on the known timeline for biological and behavioral effects of carbohydrates (Spring, Lieberman, Swope, & Garfield, 1986).

Results showed a significant beverage by time interaction effect on POMS dysphoria [F(3,57) = 4.5, p<.05]. Simple effects analysis was used to evaluate change in dysphoria between the manipulation check and 90 and 135 minute time points. Paired sample t-tests using dysphoria change scores revealed that at 90 minutes, dysphoria was significantly more improved after carbohydrate intake (M= 19.7; SD 14.24) compared to protein-rich intake (M = 14.4; SD 11.48), t(20) = 2.31, p<.05. Similarly, dysphoria was significantly more improved after carbohydrate intake at 135 minutes (M = 20.3; SD 14.5) than after protein-rich intake (M =14.4; SD 11.4), t(20) = 2.34, p<.05. This macronutrient difference constitutes a medium effect size (ES=.5). No differential macronutrient effect on positive mood state (vigor) was identified. Cell means for mood scores are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

POMS scores by macronutrient condition (averaged across both exposure weeks)

| Time | Bl | M√ | 90 min | 135 min | Δ90 | Δ135 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M(SD) | M(SD) | M(SD) | M(SD) | M(SD) | M(SD) | |

| Dysphoria | ||||||

| Carbohydrate | 6.7 (6.6) | 25.0 (15.3) | 5.6 (4.3) | 4.9 (3.2) | −19.5* | −20.1* |

| Protein-mixed | 5.6 (4.2) | 20.9 (13.4) | 6.1 (6.5) | 5.3 (5.1) | −14.8 | −14.8 |

| Vigor | ||||||

| Carbohydrate | 11.7 (6.8) | 5.6 (4.8) | 7.8 (5.5) | 8.9 (6.4) | +2.7 | +2.9 |

| Protein-mixed | 11.8 (7.1) | 5.1 (4.8) | 8.2 (5.8) | 8.7 (6.0) | +3.3 | +3.5 |

M√= manipulation check

Δ =change in mood from manipulation check to 90 and 135 minutes

POMS=Profile of Mood States

significantly greater than mood change under protein-mixed condition p<.05

Expectations, hunger, and palatability

Repeated measures ANOVA was conducted using expectation rating for vigor and dysphoria (from exposure sessions only) as the dependent variables and beverage (carbohydrate vs. protein-rich) and week (1 vs. 2) as repeated measures. Results revealed an interaction of beverage and week for vigor [F(1,20)=4.4, p=.05]. Simple effects analysis revealed that participants had lower expectations for how vigorous the beverage would make them feel under the carbohydrate exposure condition during the second week. There were no significant differences on expectation of dysphoria (p>.10).

Paired samples t-tests at 90 and 135 minutes indicate that hunger was also not significantly different between beverages at 90 minutes (Carbohydrate M=3.11, SD 2.3; Protein-rich M=3.23, SD 2.9; t=.14, p=.89) and 135 minutes (Carbohydrate M=3.11, SD 2.7; Protein-rich M=3.66, SD 2.9; t=.57, p=.58). Palatability ratings, however, showed an interesting trend. Although the beverages were panel tested and reliably rated as equally palatable, many participants perceived the carbohydrate beverage as slightly but significantly more palatable than the protein-rich balanced nutrient beverage across the study (Carbohydrate M=6.1, SD 2.4; Protein-rich M= 4.0, SD 3.2; t=2.9, p<.01).

Discussion

We tested whether individuals who self-describe as carbohydrate cravers and meet rigorous criteria for carbohydrate craving would demonstrate carbohydrate preference and mood enhancement in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Specifically, we tested whether carbohydrate-cravers would self-administer a carbohydrate-rich beverage over a protein-rich balanced nutrient beverage in response to mildly dysphoric mood and report subsequent mood improvement, even when blind to the nutrient they were consuming. Our results showed that when rendered dysphoric, carbohydrate cravers reliably chose to self-administer carbohydrate over protein-rich balanced nutrient when asked to choose the beverage that made them feel better. As predicted, the carbohydrate beverage engendered a significantly greater antidepressant effect than did the protein-rich beverage. Our results demonstrate that in a highly controlled environment, the carbohydrate craver appears to successfully and saliently self-medicate mildly dysphoric mood via carbohydrate ingestion.

The strength of this study lies in its methodological rigor as a placebo-controlled, double-blind self-administration trial. Potential participants were carefully screened to meet study criteria for carbohydrate craving, and dietary records confirmed that (a) the majority of snacks were composed of carbohydrates, (b) that participants were frequent snackers, and (c) that participants snacked in response to unpleasant mood states. We controlled for potentially confounding variables by limiting the weight range of participants to the overweight category to standardize the biochemical effect of the carbohydrate dose. We carefully controlled for menstrual cycle phase in both dietary screening and testing, which although logistically challenging, enabled us to rule out hormone-related fluctuations in mood and craving as confounding variables. We also assessed whether beverage-specific differences in hunger level could account for carbohydrate preference or the reported mood changes, even though protein is consistently found to be more satiating than carbohydrate (Latner & Schwartz, 1999; Johnstone, Horgan, Murison, Bremner, & Lobley 2008; Poppitt, McCormack, & Buffenstein, 1998). Almost identical hunger ratings suggest that these preference and improved mood were not related to differential hunger. Finally, measurement reliability was enhanced by testing subjects over two complete cycles of the protocol. Taking all of these factors into account, this protocol is far more scientifically rigorous than previous studies of carbohydrate craving and remedies many of the earlier methodological problems in the carbohydrate craving literature.

The use of a dysphoric mood induction was unique to this macronutrient study. This mood induction offered a novel, personalized way to recreate the natural context in which carbohydrate-craving purportedly occurs. We included participants who were depressed (current or history) or binge eaters (current or history) because we believe that this enhances the generalizability of these findings to the population of carbohydrate cravers, although this may also introduce additional variability and a potential confound. Post hoc analyses showed that binge eaters did not contribute mood, choice, hunger, or palatability data that was significantly different than the other participants.

A finding of potential interest (although a limitation to this study) is that although the two beverages were panel tested and equated for taste, texture, and consistency, the carbohydrate beverage was perceived as being more palatable. This may indicate that carbohydrate cravers’ taste perception or perception of palatability is significantly different than non-carbohydrate cravers. Although we think it unlikely, perceived palatability could be related to mood improvement or to beverage choice, despite explicit instructions to participants to choose the beverage that improved mood and despite equal expectations for mood after drinking the beverages. We note that the panel testers rated the beverages in a side-by-side testing session in random order, a design that should afford a more precise comparison of the palatability of the beverages. It would be interesting to know how the study participants would have rated the beverages in a side-by-side testing session at screening. A follow-up study may benefit from incorporating this pre-protocol palatability assessment.

Participants were told during the informed consent process that the purpose of the study was to evaluate mood effects of beverages; therefore we may have engendered a demand effect. However, as this was a double blind, placebo controlled, counterbalanced study design, we would expect that such demand effects would be equally distributed across beverage assignment. In addition, our assessment of mood expectation post-beverage ingestion allowed analysis of beverage, time, and week effects of expectations on mood. No expectation effects were found for dysphoric mood. Finally, while we attempted to control for a variety of factors related to carbohydrate preference, it is possible that participants chose the carbohydrate beverage more often and reported more mood improvement as a result of some unmeasured quality.

The difference in mood change between the carbohydrate and protein-rich conditions was approximately 5.2 points on the POMS dysphoria scale, and one might inquire as to the clinical significance of this difference. While the POMS manual does not include published norms for the dysphoria composite score, it does include a total mood disturbance (TMD) score, which includes depression, tension, anger, fatigue, and confusion, minus vigor. The mean TMD score for undergraduate females is 16.3 (SD 30.4) and for women presenting for outpatient psychotherapy 23.2 (SD 41.6) (McNair, Lorr, & Droppleman, 1971), which is similar to the dysphoria score at manipulation check in this study. It is notable that the college student norm is approximately 6.9 points lower than the outpatient mean, also similar to our difference between beverage conditions. One of our previous studies found that the mean dysphoria composite score in non-depressed, non-smokers was 6.5 (SD 9.5) and under conditions of negative mood induction and acute tryptophan depletion, could rise as high as 18.9 (SD 12.5) in participants with a personal history of recurrent major depression. Taken together, these data suggest that a 5.2-point mood change difference among a largely non-depressed sample constitutes a significant mood change difference, which was further born out by a medium effect size. We do note that our investigation of the antidepressant effect was restricted to the mild to moderate dysphoria mood range and it is of interest that subjects tended to become more dysphoric in the manipulation check on the days that they were subsequently administered the carbohydrate beverage. This raises the possibility that the effect of carbohydrate-based mood improvement may be more prominent with more severe levels of depression.

While our small sample size afforded sufficient statistical power to detect differences in self-administration and mood change, a greater number of subjects might reveal greater or more pervasive macronutrient-induced mood change, possibly extending to effects on positive mood, which were not found in this study. It is also acknowledged that our largely self-selected sample may not be representative of the carbohydrate craving population as a whole. It would be useful to evaluate the carbohydrate-craving phenomenon in males, however we restricted the sample to females due to the higher prevalence of mood and eating disorders as well as to administer a standardized dose of carbohydrate sufficient to elevate the tryptophan ratio, since there has been doubt about whether previous studies’ loading doses were adequate to do so (Caballero, Finer & Wurtman, 1988). Lastly, generalizability of our results may be limited by the environment in which we tested participants. The laboratory setting, as opposed to a more naturalistic setting at home or work, offered a more rigorous test environment, increasing our ability to control extraneous factors which might alter the often-subtle mood effects of macronutrients. It is plausible that findings in this rather ascetic environment may not generalize to a more naturalistic setting.

Disturbed mood and eating patterns have consistently been observed among individuals labeled “carbohydrate cravers”. The self-administration of carbohydrates may be reinforced in carbohydrate-cravers by reduction of unpleasant mood states, or possibly by perception of palatability, a pattern that with repetition may result in overweight and obesity. These findings may suggest a need to assist carbohydrate-cravers in identifying alternative ways of alleviating dysphoric mood or discomfort other than carbohydrate intake. Such measures might include using carbohydrate-rich snack foods that are low in fat and calories, increasing physical activity or employing cognitive-behavioral techniques to reduce dysphoric mood (Spring, Pingitore & Zaragoza, 1997).

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by NIH grants F31 MH12311 to Dr. Corsica and RO1 HL63307 to Dr. Spring. The authors acknowledge Lisa Sanchez- Johnsen, Ph.D. and Jillon Vander Wal, Ph.D. for practical assistance in conducting the research and Christine Gagnon, Ph.D. for statistical consultation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Joyce A. Corsica, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science/Chicago Medical School, Rush University Medical Center

Bonnie J. Spring, University of Illinois at Chicago, Northwestern University

References

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bray GA, York B, DeLany J. A survey of the opinions of obesity experts on the causes and treatment of obesity. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1992;55:151S–154S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/55.1.151s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero B, Finer N, Wurtman R. Plasma amino acids and insulin levels in obesity: response to carbohydrate intake and tryptophan supplements. Metabolism. 1988;37(7):672–676. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(88)90089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen L, Redig C. Effect of meal composition on mood. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1993;107(2):346–353. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.2.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Teasdale JD. Constraints on the effects of mood and memory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;48:1595–1608. [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A. Changes in mood after carbohydrate consumption. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1987;46:703. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/46.4.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A, Kurth C, Holden-Wiltse J, Saari J. Taste preferences in human obesity: carbohydrates versus fats. Appetite. 1992;18:207–221. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(92)90198-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernstrom J. Tryptophan, serotonin and carbohydrate appetite: Will the real carbohydrate craver please stand up! American Institute of Nutrition. 1988;118:1417–1419. doi: 10.1093/jn/118.11.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food Processor Nutrition Analysis Software. Database version 5. Salem, OR: ESHA Research; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Garner DM. Eating Disorders Inventory-2. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gendall KA, Joyce PR. Meal-induced changes in tryptophan:LNAA ratio: Effects on craving and binge eating. Eating Behaviors. 2000;1:53–62. doi: 10.1016/s1471-0153(00)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendall KA, Joyce PR, Abbott RM. The effects of meal composition on subsequent craving and binge eating. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24:305–315. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrick G, Foreyt J. Why treatments for obesity don’t last. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1991;91:1243–1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyton AC. Textbook of medical physiology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez S, Vander Wal JS, Spring B. A negative mood induction procedure with efficacy across repeated administrations in women. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2003;25:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Weighing the options: Criteria for evaluating weight-management programs. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone AM, Horgan GW, Murison SD, Bremner DM, Lobley GE. Effects of a high-protein ketogenic diet on hunger, appetite, and weight loss in obese men feeding ad libitum. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008;87:44–55. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latner JD, Schwartz M. The effects of a high-carbohydrate, high-protein, or balanced lunch upon later food intake and hunger ratings. Appetite. 1999;33(1):119–128. doi: 10.1006/appe.1999.0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebenluft E, Fiero PL, Bartko JJ, Moul DE, Rosenthal NE. Depressive symptoms and the self-reported use of alcohol, caffeine, and carbohydrates in normal volunteers and four groups of psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:294–301. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.2.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman H, Wurtman J, Chew B. Changes in mood after carbohydrate consumption among obese individuals. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1986;45:772–778. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/44.6.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lissner L, Stevens J, Levitsky DA, Rasmussen KM, Strupp BJ. Variation in energy intake during the menstrual cycle: implications for food intake research. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1988;48:956–962. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/48.4.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M. On the induction of mood. Clinical Psychology Review. 1990;10:66–76. [Google Scholar]

- McNair D, Lorr M, Droppleman L. The Manual for the Profile of Mood States (POMS) San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Services; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Mokdad AH, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Bowman BA, Marks JS, Koplan JP. The continuing epidemic of obesity in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:1650–1651. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijl H, Koppeschaar HP, Cohen AF, Iestra JA, Schoemaker HC, Frolich M, Onkenhout W, Meinders AE. Evidence for brain serotonin-mediated control of carbohydrate consumption in normal weight and obese humans. International Journal of Obesity. 1993;17:513–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppitt SD, McCormack D, Buffenstein R. Short-term effects of macronutrient preloads on appetite and energy intake in lean women. Physiology and Behavior. 1998;64(3):279–285. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redd W, Silberfarb PM, Andersen BL, Andrykowski MA, Bovbjerg DH, Burish TG, et al. Physiologic and psychobehavioral research in oncology. Cancer. 1991;77(3):813–822. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910201)67:3+<813::aid-cncr2820671411>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal NE, Genhart M, Caballero B, Jacobsen F, Skwerer R, Coursey R, Rogers S, Spring B. Psychobiological effects of carbohydrate and protein rich meals in patients with seasonal affective disorder and normal controls. Biological Psychiatry. 1989;25:1029–1040. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(89)90291-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayegh R, Schiff I, Wurtman J, Spiers P, McDermott J, Wurtman R. The effect of a carbohydrate-rich beverage on mood, appetite, and cognitive function in women with pre-menstrual syndrome. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;86:520–528. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00246-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitton SC. Role of craving for carbohydrates upon completion of a protein-sparing fast. Psychological Reports. 1991;69:683–686. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1991.69.2.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Division; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Spring B, Chiodo J, Bowen D. Carbohydrates, tryptophan, and behavior: a methodological review. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;102:234–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spring B, Hitsman B, Pingitore R, McChargue D, Gunnarsdottir D, Corsica J, et al. Effect of tryptophan depletion on smokers and nonsmokers with and without a history of major depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spring B, Lieberman H, Swope G, Garfield G. Effects of carbohydrates on mood and behavior. Nutrition Review. 1986;44:51–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1986.tb07678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spring B, Maller O, Wurtman J, Digman L, Cozolino L. Effects of protein and carbohydrate meals on mood and performance: Interaction with sex and age. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1982–3;17:155–167. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spring B, Pingitore R, Zaragoza J. Eating styles and food choices associated with obesity and dieting. In: Dulecco R, editor. Encyclopedia of Human Biology. 2. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1997. pp. 551–564. [Google Scholar]

- Teff KL, Young SN, Blundell JE. The effect of protein or carbohydrate breakfasts on subsequent amino acid levels, satiety, and nutrient selection. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 1989;34(4):829–837. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90282-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toornvliet AC, Pijl H, Tuinenburg BM, Elte-de Wever BM, Pieters M, Frolich M, Onkenhout W, Meinders A. Psychological and metabolic responses of carbohydrate craving obese patients to carbohydrate, fat, and protein-rich meals. International Journal of Obesity. 1997;21:860–864. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasquez-Mieyer PA, Cowan PA, Arheart KL, Buffington CK, Spencer KA, Connelly BE, Cowan GW, Lustig RH. Suppression of insulin secretion is associated with weight loss and altered macronutrient intake and preference in a subset of obese adults. International Journal of Obesity. 2003;27:219–226. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.802227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtman J. Disorders of food intake. Excessive carbohydrate intake among a class of obese people. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1987:197–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb36211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtman J. Carbohydrate craving: relationship between mood and disorders of carbohydrate intake. Drugs. 1990;39(Supp 3):49–52. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199000393-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtman R, Wurtman J. Brain serotonin, carbohydrate craving, obesity, and depression. Obesity Research. 1995;3(4):477S–480S. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanovski S. Sugar and fat: cravings and aversion. Journal of Nutrition. 2003;133:835S–837S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.3.835S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokogoshi H, Wurtman R. Meal composition of plasma amino acid ratios: Effect of various proteins and carbohydrates, and of various protein concentrations. Metabolism. 1986;35:837–842. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(86)90225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]