Abstract

In the Digitalis Investigation Group trial, digoxin-associated reduction in the combined end point of heart failure (HF) hospitalization or HF mortality was significant in systolic but not in diastolic HF. To assess whether this apparent disparity can be explained by differences in baseline characteristics and sample size, we used propensity score matching to assemble a cohort of 916 pairs of systolic and diastolic HF patients who were balanced in all measured baseline covariates. We estimated hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) of the effect of digoxin on outcomes separately in systolic and diastolic HF, at 2 years (protocol pre-specified) and at the end of 3.2 years of median follow up. HF hospitalization or HF mortality occurred in 28% and 32% of systolic (HR when digoxin was compared with placebo =0.85, 95% CI =0.67 to 1.08, p =0.188), and 20% and 25% of diastolic (HR =0.79, 95% CI =0.60 to 1.03, p =0.085) HF patients respectively receiving digoxin and placebo. At 2 years, HR for this combined end point were similar for systolic (0.72, 95% CI =0.55 to 0.95, p =0.022) and diastolic (0.69, 95% CI =0.50 to 0.95, p =0.025) HF. Digoxin also reduced 2-year HF hospitalization in both systolic (HR =0.73, 95% CI =0.54 to 0.97, p =0.033) and diastolic (HR =0.64, 95% CI =0.45 to 0.90, p =0.010) HF. In conclusion, as in systolic HF, digoxin was equally effective in diastolic HF, who constitutes half of all patients with HF, yet has few evidence-based therapeutic options.

Keywords: Digoxin, Heart Failure, Systolic, Diastolic, Morbidity, Mortality

With over one million hospitalizations each year, heart failure (HF) is the number one reason for hospital admission among population ≥65 years in the United States.1 Nearly half of the five million HF patients have diastolic HF and these patients are as likely as systolic HF patients to be hospitalized for HF.2,3 HF hospitalization is associated with increased mortality, and risk of post-discharge mortality is similar in both systolic and diastolic HF.4 Yet, few interventions to reduce HF hospitalization have been tested in diastolic HF. In the Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) trial, digoxin significantly reduced HF hospitalization in systolic HF (left ventricular ejection fraction {LVEF} ≤45%) in the main trial (n=6800), but not in diastolic HF (LVEF >45%) in the ancillary trial (n=988).5,6 This disparity in the effect of digoxin has been attributed to the smaller sample size of the DIG ancillary trial and potential baseline differences between systolic and diastolic HF patients.2,7 However, this has never been systematically examined and may have contributed to a potential underuse of digoxin in diastolic HF.8,9 We examined the effect of digoxin on outcomes separately in propensity-matched systolic and diastolic HF patients of equal sample size.

Methods

We used a public-use copy of the DIG dataset obtained from the NHLBI. The rationale, design, and results of the DIG trial have been previously reported.5 Briefly, 7788 chronic HF patients in normal sinus rhythm were randomized to receive digoxin or placebo. These patients were recruited from 302 clinical centers in the US (186) and Canada (116) between 1991 and 1993. Patients with LVEF ≤45% (n = 6800) were enrolled in the main trial and those with LVEF >45% (n = 988) were enrolled in the ancillary trial. Patients received 4 different daily doses of digoxin or matching placebo (0.125, 0.25, 0.375, and 0.5 mg).5 Most patients were receiving diuretics (>80%) and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (>90%).

Our main outcome was the combined end point of HF hospitalization or HF mortality because it was the primary outcome of the DIG ancillary trial and was used as the basis of US Food and Drug Administration approval of digoxin. Since this combined end point was primarily driven by a reduction in HF hospitalization, we also examined that outcome separately. We analyzed the effect of digoxin on these outcomes both at study end and at 2 years of follow up. The 2-year analysis was pre-specified in the DIG protocol and was also the basis of FDA approval.10,11 Outcomes data were classified by DIG investigators who were blinded to the patient’s study-drug assignment and were 98.9% complete.12

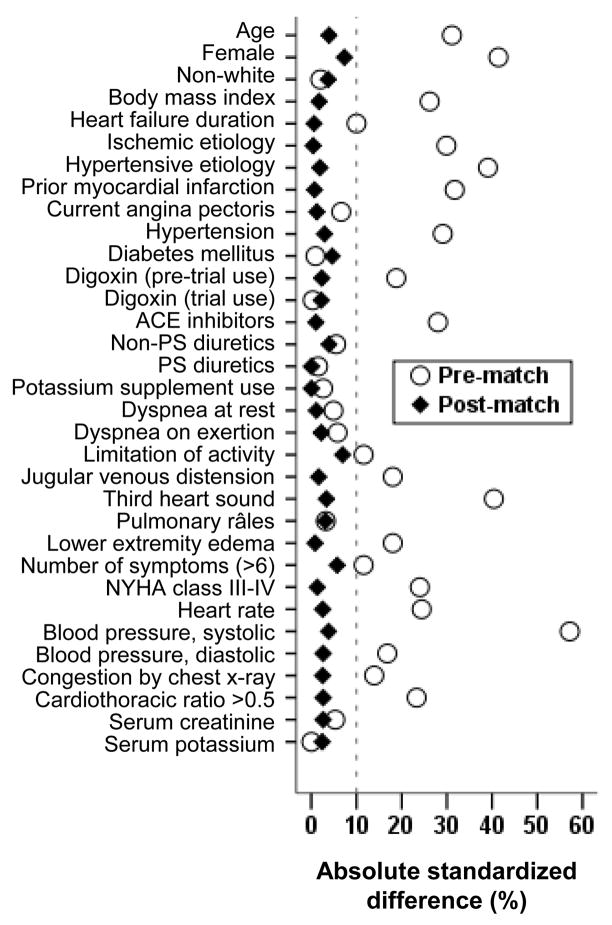

To ensure that the effect of digoxin in systolic and diastolic HF patients would not be in part due to differences in baseline characteristics between these 2 groups, we assembled a propensity-matched population in which 916 pairs of systolic and diastolic HF patients were balanced in all measured baseline covariates. We calculated propensity scores for diastolic HF for each patient using a non-parsimonious multivariable logistic regression model adjusting for all measured baseline covariates displayed in Figure 1.13,14 Absolute standardized differences of <10% for all measured covariates suggested inconsequential post-match imbalance.13,15,16

Figure 1.

Absolute standardized differences before and after propensity score matching comparing covariate values for patients with systolic (ejection fraction ≤45%) and diastolic (ejection fraction >45%) heart failure

(ACE=angiotensin-converting enzyme; NYHA=New York Heart Association; PS=potassium sparing)

Kaplan-Meier cumulative plots for digoxin and placebo were constructed and compared using log-rank statistics, separately for systolic and diastolic HF. Cox proportional-hazards models were used to compare the effects of digoxin on both outcomes. To determine if the effect of digoxin persisted despite baseline differences, we repeated our analyses in a cohort of 988 systolic HF patients, randomly selected from the 6800 patients in the main trial. All analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat basis, with 2-sided values of p <0.05 considered significant, using SPSS 15 for Windows.17

Results

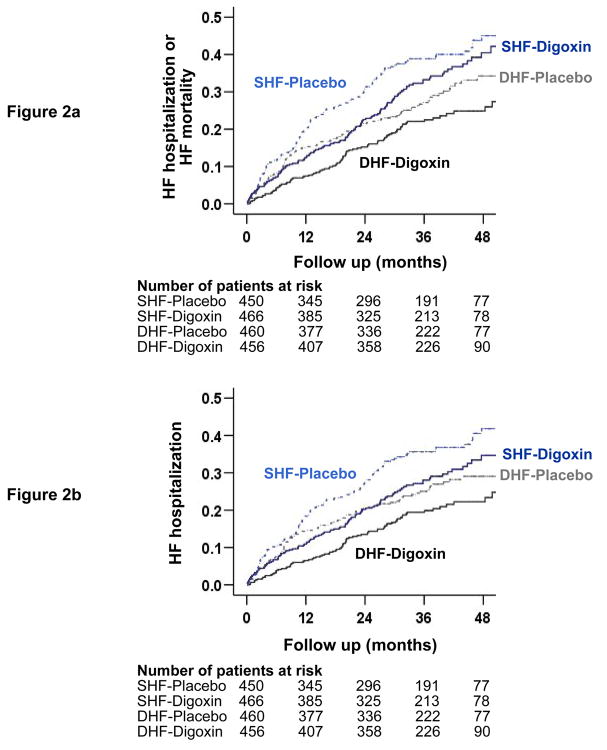

Imbalances in baseline characteristics between patients with systolic and diastolic HF in the original dataset, and balance achieved after propensity matching are displayed in Figure 1. Baseline patient characteristics between patients receiving digoxin and placebo for matched systolic and diastolic HF patients are displayed in Table 1. The effect of digoxin on the combined end point of HF hospitalization or HF mortality was similar among systolic (hazard ratio {HR} = 0.85, 95% confidence interval {CI} = 0.67 to 1.08, p = 0.188) and diastolic (HR = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.60 to 1.03, p = 0.085) HF (Table 2 and Figure 2a). There was no significant interaction between digoxin and LVEF, regardless whether it was used as a categorical (using a 45% cut-off; p = 0.655) or a continuous variable (p = 0.991). The effect of digoxin on HF hospitalization was also similar in both systolic (HR = 0.80, 95% CI = 0.62–1.03, p = 0.079) and diastolic (HR = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.57 to 1.03, p = 0.074) HF (Table 2 and Figure 2b), also without any interaction.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics of the propensity-matched systolic and diastolic heart failure patients, by treatment group

| N (%) or mean (±SD) | Left ventricular ejection fraction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤45% (N=916)

|

>45% (N=916)

|

|||||

| Placebo (N=450) | Digoxin (N=466) | P Value | Placebo (N=460) | Digoxin (N=456) | P Value | |

| Age (years) | 67 (10) | 67 (11) | 0.561 | 67 (10) | 66 (11) | 0.607 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 32 (8) | 31 (8) | 0.390 | 55 (8) | 55 (8) | 0.744 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.4) | 0.859 | 1.27 (0.39) | 1.24 (0.39) | 0.367 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 62 (20) | 61.5 (19) | 0.580 | 61.4 (20) | 63.4 (21) | 0.138 |

| Duration of heart failure (months) | 28 (32) | 25 (30) | 0.156 | 28 (37) | 25 (30) | 0.107 |

| Age ≥65 years | 292 (65%) | 287 (62%) | 0.300 | 293 (64%) | 280 (61%) | 0.474 |

| Female | 161 (36%) | 154 (33%) | 0.384 | 173 (38%) | 174 (38%) | 0.864 |

| Nonwhite | 74 (16%) | 63 (14%) | 0.215 | 59 (13%) | 66 (15%) | 0.468 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 214 (48%) | 238 (51%) | 0.287 | 229 (50%) | 207 (45%) | 0.184 |

| Cardiothoracic ratio >0.5 | 218 (48%) | 240 (52%) | 0.355 | 234 (51%) | 236 (52%) | 0.789 |

| New York Heart Association functional class | ||||||

| I | 82 (18%) | 72 (16%) | 0.225 | 96 (21%) | 84 (18%) | 0.405 |

| II | 276 (61%) | 273 (59%) | 255 (55%) | 273 (60%) | ||

| III | 87 (19%) | 115 (25%) | 101 (22%) | 95 (21%) | ||

| IV | 5 (1%) | 6 (1%) | 8 (2%) | 4 (1%) | ||

| Signs or symptoms of heart failure* | ||||||

| 0 | 3 (1%) | 9 (2%) | 0.413 | 4 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 0.401 |

| 1 | 17 (4%) | 12 (3%) | 10 (2%) | 6 (1%) | ||

| 2 | 38 (8%) | 40 (9%) | 31 (7%) | 33 (7%) | ||

| 3 | 38 (8%) | 42 (9%) | 51 (11%) | 36 (8%) | ||

| ≥4 | 354 (79%) | 363 (78%) | 364 (79%) | 378 (83%) | ||

| Previous myocardial infarction | 231 (51%) | 248 (53%) | 0.568 | 241 (52%) | 241 (53%) | 0.889 |

| Current angina pectoris | 126 (28%) | 140 (30%) | 0.496 | 131 (29%) | 140 (31%) | 0.461 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 142 (32%) | 135 (29%) | 0.394 | 133 (29%) | 125 (27%) | 0.614 |

| Hypertension | 254 (56%) | 284 (61%) | 0.167 | 252 (55%) | 273 (60%) | 0.120 |

| Previous digoxin use | 162 (36%) | 163 (35%) | 0.747 | 175 (38%) | 160 (35%) | 0.353 |

| Primary cause of heart failure | ||||||

| Ischemic | 265 (59%) | 283 (61%) | 0.876 | 272 (59%) | 274 (60%) | 0.932 |

| Non-ischemic | 185 (41%) | 183 (39%) | 188 (41%) | 182 (40%) | ||

| Hypertensive | 98 (22%) | 86 (19%) | 86 (19%) | 91 (20%) | ||

| Idiopathic | 48 (11%) | 51 (11%) | 53 (12%) | 51 (11%) | ||

| Concomitant medications | ||||||

| Non-potassium sparing diuretics | 357 (79%) | 355 (76%) | 0.252 | 357 (78%) | 340 (75%) | 0.280 |

| Potassium sparing diuretics | 39 (9%) | 34 (7%) | 0.444 | 39 (9%) | 34 (8%) | 0.568 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 402 (89%) | 401 (86%) | 0.131 | 403 (88%) | 397 (87%) | 0.803 |

| Nitrates | 195 (43%) | 196 (42%) | 0.697 | 182 (40%) | 188 (41%) | 0.608 |

| Daily dose of study medication (mg) | ||||||

| 0.125 | 82 (18%) | 97 (21%) | 0.695 | 103 (23%) | 99 (22%) | 0.277 |

| 0.250 | 310 (69%) | 311 (67%) | 315 (69%) | 303 (67%) | ||

| 0.375 | 51 (11%) | 51 (11%) | 34 (7%) | 50 (11%) | ||

| 0.500 | 6 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 3 (1%) | ||

The clinical signs or symptoms studied included râles, elevated jugular venous pressure, peripheral edema, dyspnea at rest or on exertion, orthopnea, limitation of activity, S3 gallop, and radiological evidence of pulmonary congestion.

Table 2.

Effect of digoxin on outcomes at the study end in systolic & diastolic heart failure (HF) patients

| Outcomes | Original data (N=7788) with 6800 SHF and 988 DHF patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic HF* | Placebo (n=3403) | Digoxin (n=3397) | Absolute rate difference (%) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|

|

|||||

| HF hospitalization or HF mortality | 1291 (38%) | 1041 (31%) | − 7.3 | 0.75 (0.69–0.82) | <0.001 |

| HF hospitalization | 1180 (35%) | 910 (27%) | − 7.9 | 0.72 (0.66–0.79) | <0.001 |

|

|

|||||

| Diastolic HF† | Placebo (n=496) | Digoxin (n=492) | Absolute rate difference (%) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|

|

|||||

| HF hospitalization or HF mortality | 119 (24%) | 102 (21%) | − 3.3 | 0.82 (0.63–1.07) | 0.136 |

| HF hospitalization | 108 (22%) | 89 (18%) | − 3.7 | 0.79 (0.59–1.04) | 0.094 |

| Matched data (N=1832) with 916 SHF and 916 DHF patients

|

|||||

| Systolic HF | Placebo (n=450) | Digoxin (n=466) | Absolute rate difference (%) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|

|

|||||

| HF hospitalization or HF mortality | 143 (32%) | 132 (28%) | − 3.5 | 0.85 (0.67–1.08) | 0.188 |

| HF hospitalization | 131 (29%) | 113 (24%) | − 4.9 | 0.80 (0.62–1.03) | 0.079 |

|

|

|||||

| Diastolic HF | Placebo (n=460) | Digoxin (n=456) | Absolute rate difference (%) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|

|

|||||

| HF hospitalization or HF mortality | 113 (25%) | 93 (20%) | − 4.2 | 0.79 (0.60–1.03) | 0.085 |

| HF hospitalization | 102 (22%) | 82 (18%) | − 4.2 | 0.77 (0.57–1.03) | 0.074 |

Adapted from: The Digitalis Investigation Group Investigators. N Engl J Med 1997;336:525–533.

Adapted from: Ahmed A, et al. Circulation 2006; 114(5):397–403.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier plots for (a) combined end point of heart failure (HF) hospitalization or HF mortality, and (b) HF hospitalization alone in systolic (SHF) and diastolic (DHF) heart failure patients receiving digoxin or placebo

At the end of 2 years of follow up, the effect of digoxin on the combined end point was similar among systolic (0.72, 95% CI = 0.55 to 0.95, p = 0.022) and diastolic (0.69, 95% CI = 0.50 to 0.95, p = 0.025) HF and digoxin also reduced HF hospitalization in both systolic (0.73, 95% CI = 0.54 to 0.97, p = 0.033) and diastolic (0.64, 95% CI = 0.45 to 0.90, p = 0.010) HF (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of digoxin on outcomes at the end of 2 years in systolic & diastolic heart failure (HF) patients

| Outcomes | Original data (N=7788) with 6800 SHF and 988 DHF patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic HF* | Placebo (n=3403) | Digoxin (n=3397) | Absolute rate difference (%) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|

|

|||||

| HF hospitalization or HF mortality | 999 (29%) | 735 (22%) | − 7.8 | 0.69 (0.63–0.76) | <0.001 |

| HF hospitalization | 920 (27%) | 667 (20%) | − 7.4 | 0.68 (0.62–0.75) | <0.001 |

|

|

|||||

| Diastolic HF† | Placebo (n=496) | Digoxin (n=492) | Absolute rate difference (%) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|

|

|||||

| HF hospitalization or HF mortality | 90 (18%) | 67 (14%) | − 4.5 | 0.71 (0.52–0.98) | 0.034 |

| HF hospitalization | 86 (17%) | 59 (12%) | − 5.3 | 0.66 (0.47–0.91) | 0.012 |

| Matched data (N=1832) with 916 SHF and 916 DHF patients

|

|||||

| Systolic HF | Placebo (n=450) | Digoxin (n=466) | Absolute rate difference (%) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|

|

|||||

| HF hospitalization or HF mortality | 114 (25%) | 89 (19%) | − 6.2 | 0.72 (0.55–0.95) | 0.022 |

| HF hospitalization | 102 (23%) | 80 (17%) | − 5.5 | 0.73 (0.54–0.97) | 0.033 |

|

|

|||||

| Diastolic HF | Placebo (n=460) | Digoxin (n=456) | Absolute rate difference (%) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|

|

|||||

| HF hospitalization or HF mortality | 86 (19%) | 62 (14%) | − 5.1 | 0.69 (0.50–0.95) | 0.025 |

| HF hospitalization | 82 (18%) | 55 (12%) | − 5.6 | 0.64 (0.45–0.90) | 0.010 |

Adapted from: GlaxoSmithKline. Lanoxin (digoxin) tablets, USP: Full prescribing information. 2001.

Adapted from: Ahmed A, et al. Circulation 2006; 114(5):397–403.

Among a random subset of systolic HF patients (n=988), digoxin use was associated with non-significant reduction in the combined end points (HR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.70–1.06, p = 0.158) and HF hospitalization (HR = 0.81, 95% CI 0.65–1.01, p = 0.059). These associations were similar to those observed in diastolic HF (n=988) in the DIG ancillary trial (Table 2).6

Discussion

Findings from the present analysis demonstrate that digoxin use was associated with a significant reduction in HF hospitalization during the first 2 years of follow-up and a near-significant reduction at the study end in both systolic and diastolic HF patients. These findings are important as patients with diastolic HF are as likely as systolic HF patients to be hospitalized and yet there are few evidence-based recommendations for these patients. Moreover, nearly half of all HF patients have diastolic HF and this number is expected to increase in the coming decades with the aging of the population.1

There were 2 distinct differences between systolic and diastolic HF patients in the DIG trial. The sample size of patients with diastolic HF was approximately 7 times smaller (988 versus 6800) and despite their older age, they had better survival profiles than systolic HF patients. Treatment effect is generally more pronounced in subgroups of patients with higher burden of disease severity and poorer outcomes.18 However, when we examined the effect of digoxin in a random subset of 988 systolic HF patients, who had different baseline characteristics than those with diastolic HF (Figure 1, pre-match), we found similar results suggesting that the lack of a significant effect of digoxin in diastolic HF in the DIG trial was more likely a function of sample size, and is less likely due to differences in baseline patient characteristics between systolic and diastolic HF patients.

Our finding of a similar effect of digoxin in systolic and diastolic HF patients is mechanistically plausible. The neurohormonal activation is a common pathophysiological pathway in both systolic and diastolic HF that may contribute to disease progression. Growing evidence points to neurohormonal antagonism as a more probable mechanism of action of digoxin in HF than its cardiac positive inotropic effect. Digitalis has been shown to reduce the activity of the sympathetic nervous system and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system by inhibiting the sodium-potassium adenosine triphosphatase enzyme respectively in vagal afferent fibers and the kidneys.1 The beneficial effect of digoxin lost statistical significance after the first 2 years of follow up, and more importantly, the effect of digoxin was not harmful in later years. This diminished late effect may be due to cross-over in later years and the use of higher doses of digoxin in the DIG trial, as evidenced from later post-hoc analyses, which may have resulted in higher cumulative digoxin serum concentrations in later years and elimination of earlier benefits.11,19 Low-dose digoxin is a strong independent predictor of low serum digoxin concentrations, which have been shown to reduce mortality.11

Evidence on the treatment of diastolic HF remains scarce. The effect of candesartan on HF hospitalization in diastolic HF was very similar to the effect of digoxin in the ancillary DIG trial.7,9 However, digoxin has fewer side effects and is less expensive, an important consideration for patients in the developing nations.7 Perindopril was among the few other drugs tested in diastolic HF and it had no effect on the primary outcome of all-cause death or unplanned HF hospitalization.20 Currently, irbesartan and aldosterone are being studied in diastolic HF in 2 separate large randomized clinical trials.21,22

A key limitation of the current analysis is the use of smaller sample size of systolic HF that resulted in non-significant effect of digoxin on the combined end point. However, the magnitude of the effect was similar to that observed in the main trial. Yet, findings from the current analysis demonstrate that digoxin may be effective in reducing HF hospitalization in both systolic and diastolic HF. These findings are relevant to contemporary diastolic HF patients as since the DIG trial no new drug has been shown to be effective in these patients. Digoxin in low dosages should be used in systolic HF patients with or without atrial fibrillation who remain symptomatic despite therapy with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, and approved beta-blockers, especially in those who cannot afford or tolerate these drugs. In patients with diastolic HF, digoxin should be prescribed to reduce symptoms and hospitalizations. Digoxin may also be helpful in controlling heart rate for those with atrial fibrillation which is more prevalent in diastolic HF.23

Acknowledgments

Funding support: Dr. Ahmed is supported by the National Institutes of Health through grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (5-R01-HL085561-02 and P50-HL077100), and a generous gift from Ms. Jean B. Morris of Birmingham, Alabama.

“The Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) study was conducted and supported by the NHLBI in collaboration with the DIG Investigators. This Manuscript was prepared using a limited access dataset obtained from the NHLBI and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the DIG Study or the NHLBI.”

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration Information: Information on DIG dataset can be found at the following NHLBI website: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/deca/descriptions/dig.htm

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hunt SA. ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:e1–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed A, Perry GJ, Fleg JL, Love TE, Goff DC, Jr, Kitzman DW. Outcomes in ambulatory chronic systolic and diastolic heart failure: a propensity score analysis. Am Heart J. 2006;152:956–966. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatia RS, Tu JV, Lee DS, Austin PC, Fang J, Haouzi A, Gong Y, Liu PP. Outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in a population-based study. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:260–269. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed A, Allman RM, Fonarow GC, Love TE, Zannad F, Dell’italia LJ, White M, Gheorghiade M. Incident heart failure hospitalization and subsequent mortality in chronic heart failure: a propensity-matched study. J Card Fail. 2008;14:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Digitalis Investigation Group Investigators. The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:525–533. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702203360801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmed A, Rich MW, Fleg JL, Zile MR, Young JB, Kitzman DW, Love TE, Aronow WS, Adams KF, Jr, Gheorghiade M. Effects of digoxin on morbidity and mortality in diastolic heart failure: the ancillary digitalis investigation group trial. Circulation. 2006;114:397–403. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed A, Young JB, Gheorghiade M. The underuse of digoxin in heart failure, and approaches to appropriate use. CMAJ. 2007;176:641–643. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gheorghiade M, Zannad F, Sopko G, Klein L, Pina IL, Konstam MA, Massie BM, Roland E, Targum S, Collins SP, Filippatos G, Tavazzi L. Acute heart failure syndromes: current state and framework for future research. Circulation. 2005;112:3958–3968. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.590091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Held P, McMurray JJ, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Ostergren J. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM-Preserved Trial. Lancet. 2003;362:777–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Digitalis Investigation Group Investigators. Protocol: Trial to Evaluate the Effect of Digitalis on Mortality in Heart Failure. Bethesda, Md: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 1991. Digitalis Investigation Group. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmed A, Rich MW, Love TE, Lloyd-Jones DM, Aban IB, Colucci WS, Adams KF, Gheorghiade M. Digoxin and reduction in mortality and hospitalization in heart failure: a comprehensive post hoc analysis of the DIG trial. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:178–186. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins JF, Howell CL, Horney RA. Determination of vital status at the end of the DIG trial. Control Clin Trials. 2003;24:726–730. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed A, Husain A, Love TE, Gambassi G, Dell’Italia LJ, Francis GS, Gheorghiade M, Allman RM, Meleth S, Bourge RC. Heart failure, chronic diuretic use, and increase in mortality and hospitalization: an observational study using propensity score methods. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1431–1439. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levesque R SPSS. A guide for SPSS and SAS users. 2. SPSS; Chicago (Ill): 2005. Macros, SPSS programming and data management. available for download at http://www.spsstools.net/spss_programming.htm 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Agostino RB., Jr Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17:2265–2281. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981015)17:19<2265::aid-sim918>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Normand ST, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Ayanian JZ, Ryan TJ, Cleary PD, McNeil BJ. Validating recommendations for coronary angiography following acute myocardial infarction in the elderly: a matched analysis using propensity scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:387–398. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.SPSS for Windows R. Chicago: SPSS Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rothwell PM. Treating individuals 2. Subgroup analysis in randomised controlled trials: importance, indications, and interpretation. Lancet. 2005;365:176–186. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17709-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rathore SS, Curtis JP, Wang Y, Bristow MR, Krumholz HM. Association of serum digoxin concentration and outcomes in patients with heart failure. JAMA. 2003;289:871–878. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.7.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cleland JGF, Tendera M, Adamus J, Freemantle N, Polonski L, Taylor J on behalf of PEPCHFI. The perindopril in elderly people with chronic heart failure (PEP-CHF) study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2338–2345. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carson P, Massie BM, McKelvie R, McMurray J, Komajda M, Zile M, Ptaszynska A, Frangin G. The irbesartan in heart failure with preserved systolic function (I-PRESERVE) trial: rationale and design. J Card Fail. 2005;11:576–585. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.06.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.TOPCAT Study Investigators. [Accessed March 17, 2008];Treatment of preserved cardiac function heart failure with an aldoserone antagonist. 2008 http://www.topcatstudy.com/

- 23.Yancy CW, Lopatin M, Stevenson LW, De Marco T, Fonarow GC. Clinical presentation, management, and in-hospital outcomes of patients admitted with acute decompensated heart failure with preserved systolic function: a report from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) Database. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]