Abstract

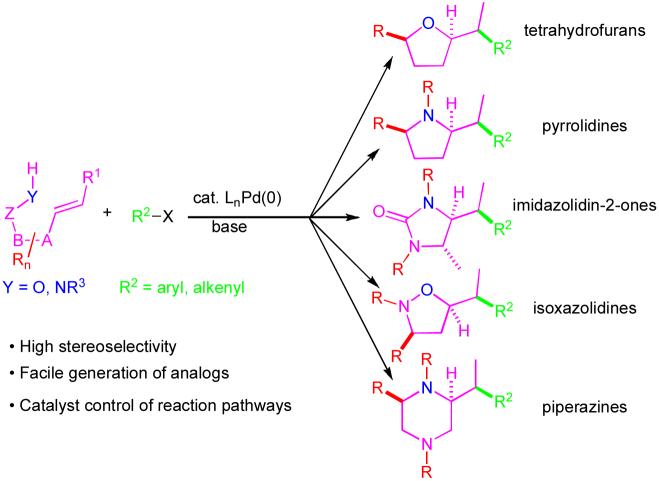

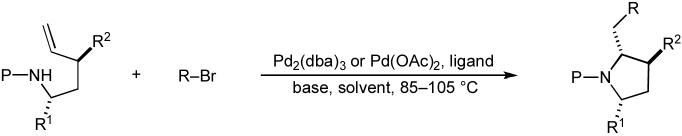

The development of Pd-catalyzed carboetherification and carboamination reactions between aryl/alkenyl halides and alkenes bearing pendant heteroatoms is described. These transformations effect the stereoselective construction of useful heterocycles such as tetrahydrofurans, pyrrolidines, imidazolidin-2-ones, isoxazolidines, and piperazines. The scope, limitations, and applications of these reactions are presented, and current stereochemical models are described. The mechanism of product formation, which involves an unusual intramolecular syn-insertion of an alkene into a Pd-Heteroatom bond is also discussed in detail.

Keywords: Alkenes, Catalysis, Heterocycles, Palladium, Stereoselective Synthesis

1 Introduction

Saturated heterocyclic compounds are of great importance in medicinal chemistry and chemical biology due to the fact that many biologically active molecules contain these moieties.1 The vast majority of these compounds are five- or six-membered heterocycles with one or two oxygen or nitrogen atoms, and many contain stereocenters around or adjacent to the ring.

Due to the significance of heterocycles such as those described above, many methods have been developed for their construction.2-4 Ring formation is most commonly achieved through intramolecular SN2 reactions, halocyclizations, reductive aminations, cycloadditions, or ring-closing alkene metathesis reactions. Despite the utility of these strategies, control of relative stereochemistry can be problematic in reactions that generate new stereocenters. In addition, several of these strategies are limited in their applicability to the preparation of analogs or libraries of derivatives from a common precursor. Finally, although many methods effect closure of the heterocyclic ring with formation of a new carbon-heteroatom bond adjacent to the ring, few existing transformations allow for ring closure with concomitant formation of a C-C bond adjacent to the ring.3,4 Thus, the development of new methods for the stereoselective and convergent construction of substituted heterocycles remains an active area of research, with many opportunities for improvement of scope and stereocontrol, and for creation of new strategic disconnections.

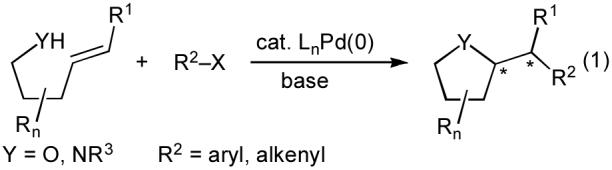

Due to our interest in the synthesis of biologically active molecules, and the limitations of existing methods for the stereoselective preparation of substituted heterocycles such as tetrahydrofurans and pyrrolidines, we elected to examine a new strategy for the construction of these moieties. We felt that a particularly attractive transformation would involve the coupling of a γ-unsaturated alcohol or amine with an aryl or alkenyl halide (eq 1).5 The alcohol or amine substrates could be prepared in a few steps using straightforward chemistry, and a large number of aryl and alkenyl halides are commercially available. Moreover, this transformation would generate a carbon-carbon bond, a carbon-heteroatom bond, and up to two stereocenters in a single step.6-8

|

We initially envisioned that these new carboetherification or carboamination reactions could potentially be facilitated through the use of a palladium catalyst system and a stoichiometric amount of a base. This approach was quite attractive, as the active catalysts could be generated in situ from the combination of air stable palladium complexes such as Pd2(dba)3 or Pd(OAc)2 and commercially available phosphine ligands. The reactivity could be tuned simply by varying the nature of the phosphine used in a given transformation. In addition, under these conditions, it seemed plausible that the desired products could potentially be formed through five different catalytic cycles involving basic organometallic reactions such as oxidative addition and migratory insertion.9 Thus, if one mechanistic pathway could not be accessed in any given system, perhaps the desired product could still be produced through a different mechanism. Finally, all of these pathways involved at least one step with little or no literature precedent, and there seemed to be considerable opportunity for new discovery.

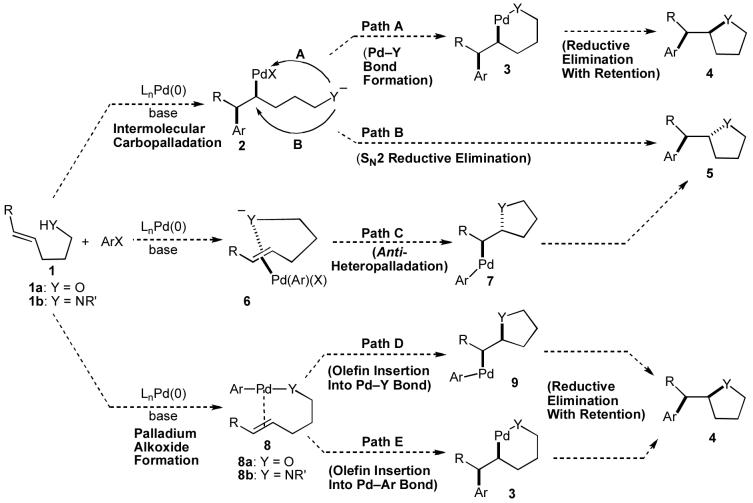

As outlined in Scheme 1, two possible mechanisms for the conversion of substrates such as 1 to heterocyclic products would involve oxidative addition of the aryl halide to Pd(0) followed by intermolecular Heck-type carbopalladation to provide 2.10 Although the steps leading to intermediate 2 are well-precedented, conversion of this intermediate to the desired products 4 or 5 would require either sp3C-Y bond-forming reductive elimination from palladium alkoxide/amide 3 (Scheme 1, Path A), or SN2-like reductive elimination directly from 2 (Path B).11 Neither of these two pathways is well-precedented, as only a few examples of sp3 carbon-heteroatom bond-forming reductive eliminations from late transition metal complexes have been described, most of which involve high-oxidation state metal complexes.11

Scheme 1.

Mechanistic possibilities

A third possible mechanism involves coordination of the alkene to the Pd(Ar)(X) species generated upon oxidative addition of the aryl halide to Pd(0) to provide 6. This intermediate could undergo anti-heteropalladation to afford 7 (Scheme 1, Path C),12 which would be converted to 5 through well-known C-C bond-forming reductive elimination. Anti-heteropalladation reactions are also well-precedented with relatively electrophilic PdX2 complexes. However, these processes are not as common with less electrophilic Pd(Ar)(X) intermediates.5a,12

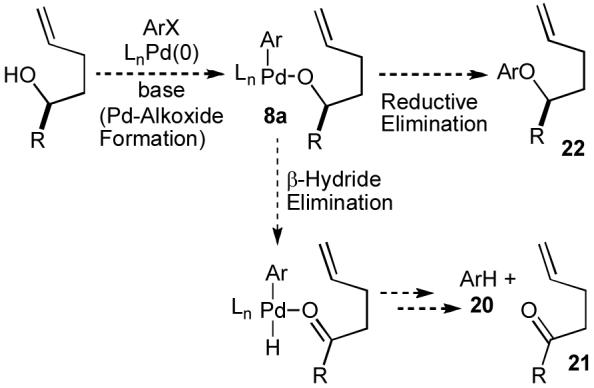

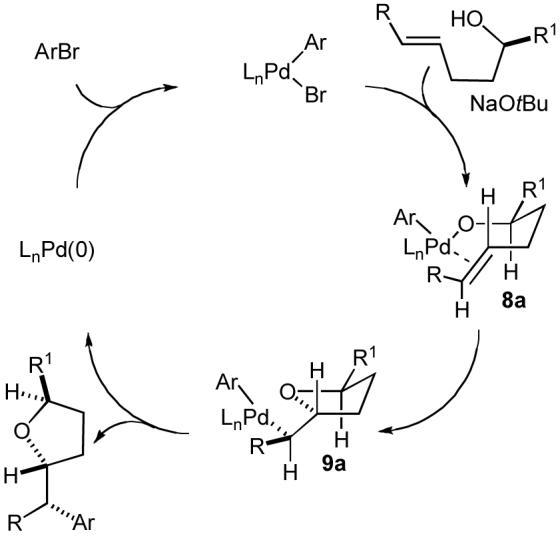

Two other mechanistic scenarios involve the formation of an intermediate Pd(Ar)(YR) complex (8) via oxidative addition of the aryl halide to Pd(0) followed by Pd-O or Pd-N bond formation.13 This intermediate could be further transformed via syn-intramolecular insertion of the alkene into the Pd-Y bond of 8 to afford 9.14,15 Finally C-C bond-forming reductive elimination from 9 would provide 4 (Scheme 1, Path D).16 However, insertions of alkenes into late transition metal-heteroatom bonds are rare, and no well-defined examples of insertions of unactivated alkenes into Pd-N or Pd-O bonds had been reported.14,15 Alternatively, insertion of the alkene into the Pd-C bond of 8 followed by the aforementioned sp3C-Y bond forming reductive elimination of the resulting complex 3 could also yield 4 (Path E).11

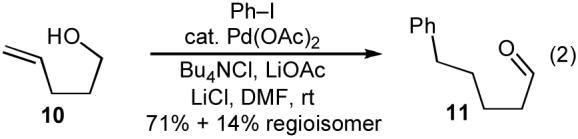

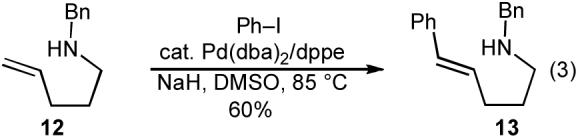

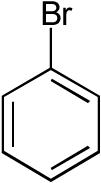

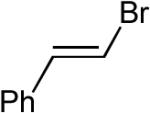

Although it appeared that the conversion of 1 to 4 or 5 could potentially be achieved, we were concerned that a number of undesirable side reactions might be problematic. For example, alcohols and amines are known to undergo O-arylation or N-arylation when treated with aryl halides in the presence of a palladium catalyst and a base, and can also effect reduction of aryl halides to arenes under these conditions.13 In addition, Pd-catalyzed Heck arylation of the alkene could compete with our desired transformation.10 Indeed, a thorough literature search turned up only three examples of Pd-catalyzed reactions of aryl halides with γ-hydroxy or γ-amino alkenes, two of which afforded Heck-arylation products. As shown in eq 2, the Pd-catalyzed reaction of 10 with iodobenzene produced aldehyde 11, which is generated via intermolecular carbopalladation of the alkene followed by β-hydride elimination/reinsertion processes.17 The Pd-catalyzed reaction of related substrate 12 with iodobenzene provided styrene derivative 13 (eq 3).18

|

|

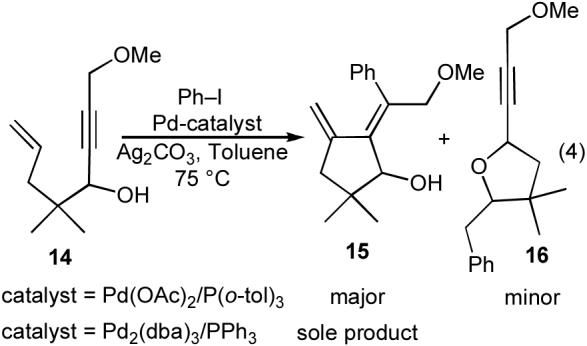

A third transformation we found in our literature search provided promise that the conversion of 1 to 4 or 5 could be achieved. In 1992, Trost described the Pd(OAc)2/P(o-tol)3-catalyzed reaction of iodobenzene with enyne 14, which gave a mixture of the expected diene 15 along with tetrahydrofuran 16 as a side product (eq 4).19 The impact of catalyst structure on product distribution, which is a central theme of this Account, was apparent in this early study, as use of a catalyst composed of Pd2(dba)3/PPh3 afforded only the diene product 15.

|

2 Pd-Catalyzed Synthesis of Tetrahydrofurans from γ-Hydroxy Alkenes and Aryl Halides

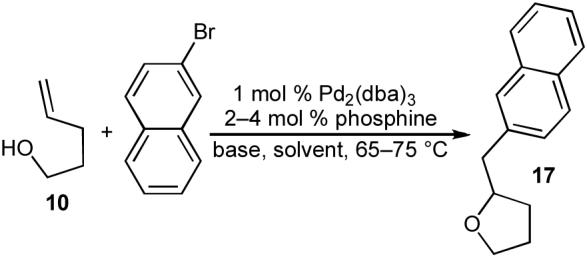

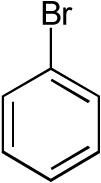

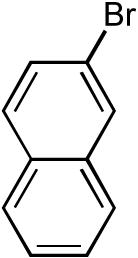

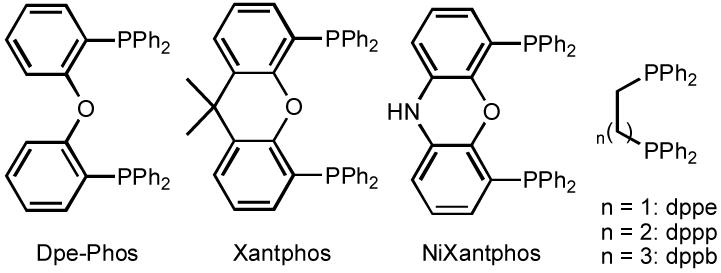

In our preliminary studies on the synthesis of tetrahydrofurans via Pd-catalyzed carboetherification reactions, we examined the coupling of 4-penten-1-ol (10) with 2-bromonaphthalene.20 We initially surveyed the conditions employed by Trost that led to the formation of a tetrahydrofuran side product (16) during the transformation of 14 to 15 (eq 4). As shown in Table 1, these conditions provided only a trace amount of the desired product 17 (ca. 2-3% yield by GC).21 In order to optimize this transformation we first explored the use of different bases, as we felt that the nucleophilicity of the heteroatom may be important, and a stronger base could provide a greater equilibrium concentration of a nucleophilic alkoxide derived from 10. After surveying several bases we found that NaOtBu provided improved but still unsatisfactory results (20% yield). The main side product formed in this reaction was naphthalene, and it seemed likely that this product was generated via β-hydride elimination of a palladium(aryl)alkoxide complex such as 8a (Scheme 1).22 At this point it was unclear if 8a was along or outside of the catalytic cycle, but it seemed plausible that a chelating bis-phosphine ligand could diminish the rate of this side reaction and potentially provide improved yields.13 After some experimentation, we found that the bidentate ligand Dpe-phos23 provided significantly improved results (45% yield), and use of 2 equiv of both NaOtBu and 2-bromonaphthalene with this ligand afforded 17 in 76% yield.

Table 1.

Optimization studies

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Base | Solvent | Phosphine | Yield |

| Ag2CO3 | Toluene | P(o-tol)3 | ∼2-3%a |

| NaOtBu | THF | P(o-tol)3 | 20%a |

| NaOtBu | THF | Dpe-phos | 45%a |

| NaOtBu | THF | Dpe-phos | 76%b |

Conditions: 1.0 equiv alcohol, 1.1. equiv 2-bromonaphthalene, 1.2 equiv base, 1 mol % Pd2(dba)3, 4 mol % P(o-tol)3 or 2 mol % Dpe-phos, solvent (0.25 M), 65-75 °C.

The reaction was conducted using 2.0 equiv 2-bromonaphthalene and 2.0 equiv NaOt-Bu.

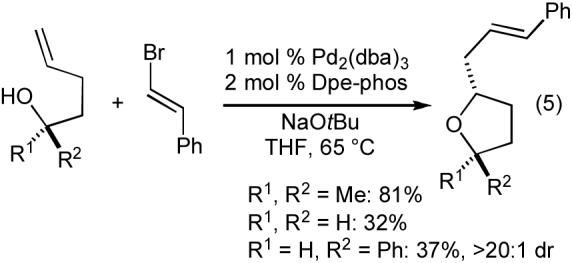

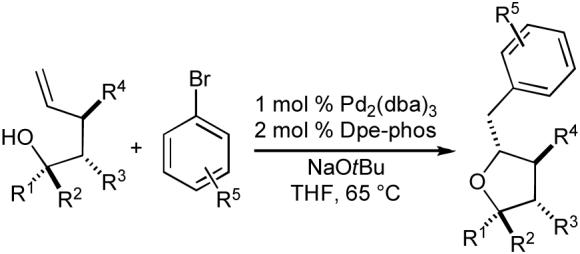

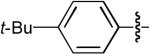

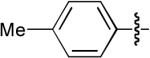

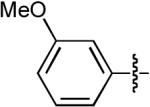

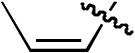

With suitable reaction conditions in hand, we proceeded to explore the scope of the tetrahydrofuran-forming reactions.20 A few representative examples of these transformations are illustrated below (Table 2). In general, the reactions are effective with primary, secondary, and tertiary alcohols. Good to excellent diastereoselectivities are obtained in the preparation of tetrahydrofurans that are trans-2,5-disubstituted or trans-2,3-disubstituted (entries 1-3). However, reactions that afford 2,4-disubstituted tetrahydrofurans proceed with modest diastereoselectivity (entry 4). A number of electron-neutral or electron-rich aryl bromides are suitable coupling partners in these transformations, but lower yields are obtained with electron-poor aryl bromides due to competing O-arylation of the alcohol substrate. Reactions of alkenyl halides with tertiary alcohols proceed in good yield, although modest yields are obtained in analogous reactions of primary or secondary alcohols (eq 5).

|

Table 2.

Synthesis of tetrahydrofurans

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | dr | Yielda |

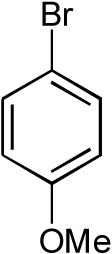

| 1 | H | Ph | H | H | p-OMe | >20:1 | 62% |

| 2 | Me | Ph | H | H | p-t-Bu | >20:1 | 77% |

| 3 | Me | Me | H | Me | p-Ph | 8:1 | 78% |

| 4 | H | H | Ph | H | m-OMe | 2:1 | 84% |

| 5 | (CH2)4 | H | H | o-Me | _ | 60% | |

| 6 | H | (CH2)4 | H | p-Ph | >20:1 | 70% | |

Conditions: 1.0 equiv alcohol, 2.0. equiv ArBr, 2.0 equiv NaOt-Bu, 1 mol % Pd2(dba)3, 2 mol % Dpe-phos, THF (0.25 M), 65 °C.

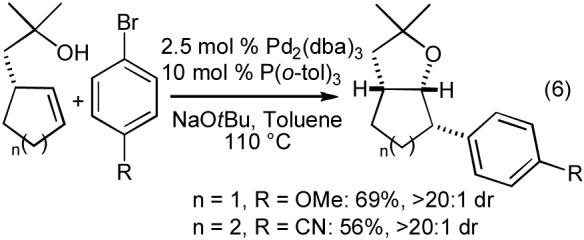

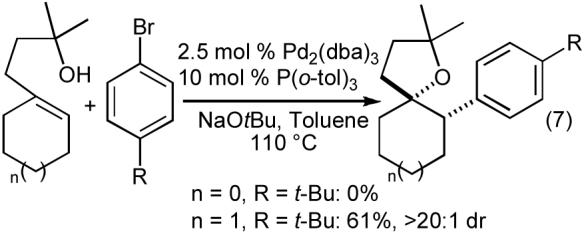

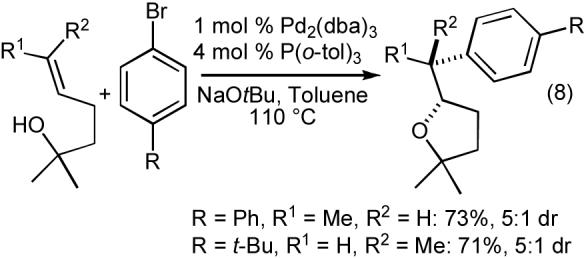

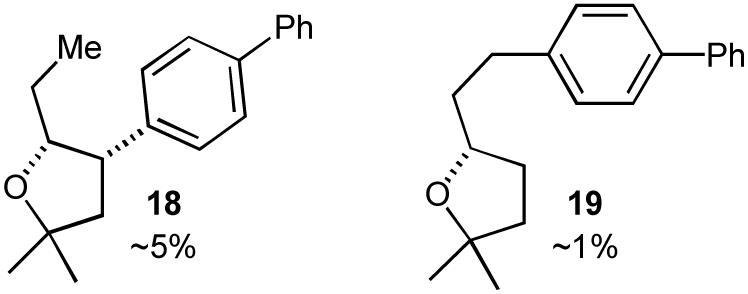

The tetrahydrofuran-forming reactions were also effective with tertiary alcohols bearing pendant internal alkenes when slightly modified reaction conditions were employed. Use of 1-2.5 mol % Pd2(dba)3, 4-10 mol % P(o-tol)3, and a reaction temperature of 110 °C provided good results with these more sterically encumbered substrates.24,25 As shown in eq 6-8, these reactions proceed with net syn-addition of the oxygen atom and the aryl group across the C-C double bond. Reactions of cyclic alkenes afforded products with >20:1 dr, and both fused bicyclic (eq 6) and spirocyclic (eq 7) molecules were generated in good yield. Transformations involving acyclic internal alkenes also produced the desired tetrahydrofurans in good yield, but with only modest (ca. 5:1) diastereoselectivity (eq 8). Interestingly, the reactions of acyclic internal alkenes also led to the formation of two additional product regioisomers (Figure 1, 18 and 19). As described in Section 2.1, the generation of these side products ultimately provided valuable insight into the mechanism of the tetrahydrofuran-forming carboetherification reactions.

|

|

|

Figure 1.

Minor regioisomers formed in the Pd-catalyzed reaction of E-2-methylhept-5-en-2-ol with 4-bromobiphenyl (eq 8).

2.1 Mechanism of Tetrahydrofuran Formation

As noted in Section 1, it seemed plausible that the tetrahydrofuran products of the carboetherification reactions could be formed through five different mechanistic pathways. However, several key results described in Section 2.0 allowed us to rule out many of these mechanistic scenarios.24a First of all, the transformations of internal alkenes illustrated in eq 6-8 (along with several other related examples), all provide products that result from syn-addition of the aryl group and the oxygen atom across the alkene double bond. Close examination of the mechanistic scenarios outlined in Scheme 1 indicates that two of the five pathways (Paths B and C) would provide products (5) resulting from anti-addition across the alkene. Thus, paths B and C could be ruled out on the basis of the observed syn-addition stereochemistry.

We were able to discount a third mechanistic possibility (Scheme 1, Path A) on the basis of stereoselectivity. As shown below (Scheme 2), the high stereoselectivity (>20:1 dr) observed in the conversion of secondary alcohols to trans-2,5-disubstituted tetrahydrofurans (Table 2, entries 1-2) is not consistent with a mechanism involving intermolecular carbopalladation. The facial selectivity of the carbopalladation is unlikely to be high when the nearest stereocenter is three atoms removed from the site of reaction, and, in contrast to our observations, the 2,5-disubstituted tetrahydrofuran products would likely be formed as ∼1:1 mixtures of cis:trans diastereomers.

Scheme 2.

Intermolecular carbopalladation diastereoselectivity

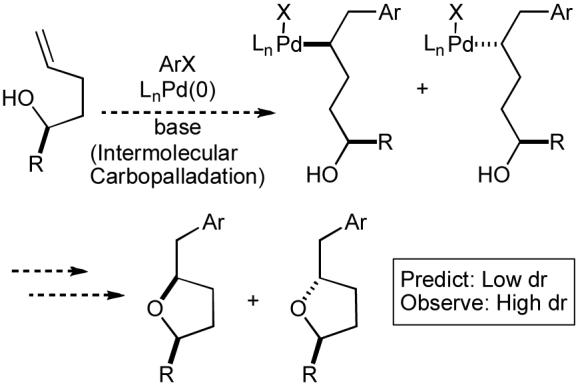

As illustrated in Scheme 1, mechanistic pathways D and E both involve palladium(aryl)(alkoxide) complexes22 (e.g. 8a) as key intermediates. Strong evidence that these complexes are present in the reaction mixture was obtained through the identification of three side products that are formed in many of these reactions. As shown in Scheme 3, two major side products are usually observed in reactions of primary and secondary alcohols: arenes (20) that result from reduction of the aryl bromide, and carbonyl derivatives (21) that derive from oxidation of the alcohol. The most likely mechanism for formation of 20 and 21 involves β-hydride elimination from palladium(aryl)(alkoxide) 8a.22 In addition, reactions that involve electron-poor aryl bromides generate side products formed through O-arylation of the alcohol substrate (e.g. 22). These side products are likely produced by C-O bond-forming reductive elimination from complex 8a.22

Scheme 3.

Formation of side products

Pathways D and E (Scheme 1) both involve the same intermediate LnPd(Ar)(OR) complex (8a), and should provide tetrahydrofuran products with the same relative stereochemistry (syn-addition). The principal difference between these two pathways lies in the chemoselectivity of the alkene insertion step. If the reactions were to proceed via Path E, the alkene would undergo insertion into the Pd-C bond of complex 8a to provide 3. However, the formation of regioisomeric tetrahydrofuran products 18 and 19 (Figure 1) in reactions of acyclic internal alkenes cannot be adequately explained by this mechanism. The product regiochemistry would be set by the C-C bond-forming carbopalladation, and there does not appear to be a plausible pathway by which 3 could be converted to 18 or 19.26

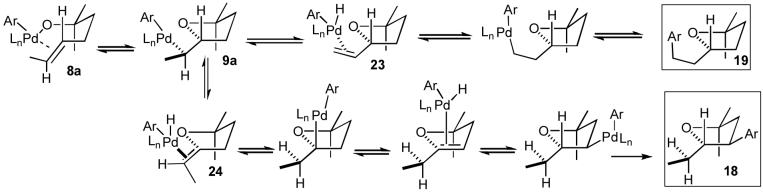

In contrast, the formation of side products 18 and 19 can easily be explained if the carboetherification reactions proceed through alkene insertion into the Pd-O bond of 8a to afford 9a. As shown in Scheme 4, 18 and 19 most likely derive from β-hydride elimination processes that occur from 9a after syn-oxypalladation. The conversion of 9a to 23 via β-elimination of one of the methyl-group hydrogen atoms can ultimately lead to 19, whereas β-elimination of the methine hydrogen atom of 9a would yield 24, which could subsequently be converted to 18 after a series of reversible reinsertion/β-elimination steps.

Scheme 4.

Formation of regioisomers

Mechanistic pathway D (Scheme 1), as illustrated with 3-dimensional structures in Scheme 5, can also account for the formation of tetrahydrofuran products that are trans-2,5-disubstituted or trans-2,3-disubstituted (Table 2, entries 1-3). The syn-oxypalladation from intermediate 8a likely occurs through a highly organized cyclic transition state in which the Pd-O bond and the C-C π-bond are eclipsed, and the substituents on the tether are oriented in a pseudoequatorial position. This would result in the stereoselective formation of intermediate 9a, which could undergo reductive elimination to afford the observed product with high diastereoselectivity.

Scheme 5.

Catalytic cycle and stereochemistry (mechanistic pathway D)

The mechanism shown in Scheme 1 (Path D) and Scheme 5 can both explain and predict the results of most tetrahydrofuran-forming reactions between aryl halides and γ-hydroxy alkenes. However, the observation that transformations of acyclic internal alkenes proceed with only ca 3-5:1 selectivity for syn- vs. anti-addition across the double bond (eq 8) could not be explained by this mechanism alone. It was also unclear why syn-addition selectivity was modest with acyclic internal alkenes but high with cyclic internal alkenes (eq 6-7, >20:1 dr). To gain further insight, we sought to identify the pathway that led to formation of the minor diastereomer in these reactions.

It seemed likely that the minor diastereomer observed in reactions of acyclic internal alkenes could arise through two pathways: a) anti-oxypalladation of 6 followed by C-C bond-forming reductive elimination from 7 (Scheme 1, Path C), or b) syn-oxypalladation from 8a to provide 9a, (Scheme 1, Path D) followed by a series of β-hydride elimination/reinsertion processes similar to those that lead to the generation of regioisomers 18 and 19 (Scheme 4).27 Further analysis of these two possibilities suggested that a set of experiments involving deuterium-labeled alkene substrates should provide definitive information. If the formation of two diastereomers results from competing syn- vs. anti-oxypalladation (Scheme 1, Paths C vs. D), both stereoisomeric products should bear the labeled atom at the same position. In contrast, if the minor stereoisomer is generated through β-hydride elimination processes, the two stereoisomers should be produced with the deuterium label at different positions (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

Deuterium labeling experiment

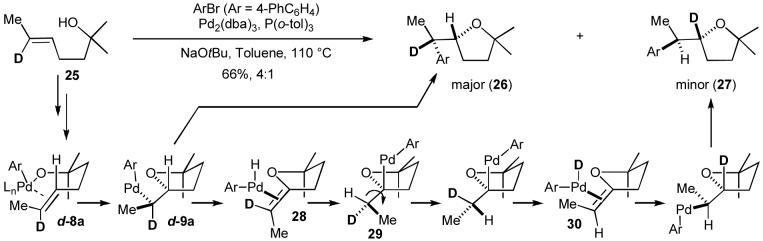

A representative deuterium labeling experiment is shown below (Scheme 6).24a Treatment of 25 with 4-bromobiphenyl and NaOtBu in the presence of a catalyst composed of Pd2(dba)3 and P(o-tol)3 led to the generation of syn-addition product 26 (deuterated at the benzylic position) and anti-addition product 27 (deuterated at the 2-position of the tetrahydrofuran ring) in a 4:1 ratio.28,29 Thus, it appears that both the major and minor stereoisomer are produced via syn-oxypalladation from intermediate 8a to provide 9a. The major stereoisomer 26 is formed directly from 9a through C-C bond-forming reductive elimination. In contrast, the minor stereoisomer 27 is formed through syn-β-hydride elimination from 9a to give 28 followed by reinsertion to provide 29. Rotation around the C2-C1’ bond of 29 followed by a second β-hydride elimination provides 30, which is converted to 27 through reinsertion followed by reductive elimination. The differences in diastereoselectivity observed in reactions of cyclic vs. acyclic alkenes are also explained by these results, as a similar mechanism for erosion of stereochemistry after syn-oxypalladation is not possible with a cyclic alkene substrate.

In addition to providing insight into the stereoselectivity of carboetherification reactions, these results provide further support for the mechanism shown in Scheme 5 and Scheme 1, Path D .24a The other mechanistic scenarios outlined in Scheme 1 (Paths A-C and E) cannot satisfactorily explain the results of our deuterium labeling studies.

3 Pd-Catalyzed Synthesis of Pyrrolidines from γ-Amino Alkenes and Aryl Halides

Despite our successful development of Pd-catalyzed carboetherification reactions between γ-hydroxy alkenes and aryl bromides, several facts suggested that the optimization of related transformations for the synthesis of pyrrolidines from γ-amino alkenes was unlikely to be straightforward. As noted above (eq 3), previous efforts to convert N-benzyl-4-pentenylamine (12) to an N-benzyl-2-benzylpyrrolidine via Pd(0)-catalyzed coupling with iodobenzene were unsuccessful.18 In addition, based on our studies on tetrahydrofuran synthesis, it seemed likely that pyrrolidine-forming reactions of this type would proceed through LnPd(Ar)(NRR’) complexes 8b as key intermediates (Scheme 1, Path D). However, Pd-catalyzed N-arylation reactions of amines are known to proceed via similar intermediates, and C-N bond-forming reductive eliminations from LnPd(Ar)(NRR’) complexes are relatively facile compared to analogous C-O bond forming reductive eliminations from LnPd(Ar)(OR) complexes.13 Thus, it seemed that competing N-arylation of the γ-amino alkene substrates could be quite problematic, even though competing O-arylation in our tetrahydrofuran-forming reactions was seldom observed.

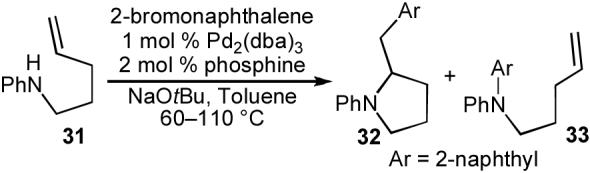

In our preliminary experiments we elected to study the coupling of N-phenyl-4-pentenylamine (31) with 2-bromonaphthalene.30a We felt that the decreased nucleophilicity of the aniline derivative 31 (relative to an aliphatic amine) might help to minimize competing N-arylation of the substrate. In addition, N-aryl amines are much easier to handle than aliphatic amines, as they can be purified by silica gel chromatography in relatively nonpolar solvent mixtures, and are less prone to react with atmospheric oxygen and carbon dioxide. As shown in Table 3, treatment of 31 with 2-bromonaphthalene (1.1 equiv) using the conditions that were optimized for tetrahydrofuran-forming reactions of primary alcohols (NaOtBu, 1 mol % Pd2(dba)3, 2 mol % Dpe-phos) did provide significant amounts of the desired pyrrolidine product 32. However, competing N-arylation, which generated side product 33, was problematic under these conditions. After some optimization, we found that improved results were obtained using either dppe or dppb as ligand,23 and our best conditions afforded 32 in 94% isolated yield.

Table 3.

Optimization studies

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand | Temp. | Ratio 32:33 | Yielda,b |

| Dpe-phos | 110 °C | 3:1 | 64% |

| Dppe | 110 °C | >20:1 | 100% |

| Dppb | 60 °C | >20:1 | 100% (94%) |

Conditions: 1.0 equiv amine, 1.1. equiv 2-bromonaphthalene, 1.2 equiv NaOtBu, 1 mol % Pd2(dba)3, 2 mol % ligand, toluene (0.25 M), 60-110 °C.

Yields refer to GC yields measured against an internal standard. Yields in parentheses are isolated yields.

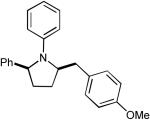

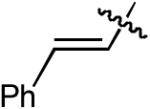

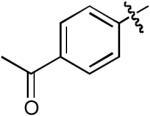

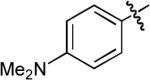

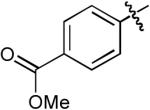

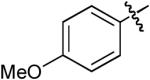

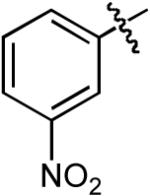

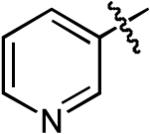

After successfully developing conditions to effect our desired carboamination reaction, we proceeded to explore the synthesis of a variety of substituted N-aryl pyrrolidines (35) using this method. Representative examples of these transformations are shown in Table 4.30a The best yields and regioselectivities were typically obtained in reactions of substrates bearing electron-withdrawing groups on the N-aryl moiety. However, acceptable results were also obtained with electron-neutral or electron-rich N-aryl substituents. Carboamination reactions of substrates substituted at C1 or C3 (34, R2 or R4 ≠ H) afforded 2,5-cis- and 2,3-trans-disubstituted products with good to excellent diastereoselectivity (entries 3, 5, 7 and 8), and a number of different aryl halides were effectively coupled. Alkenyl halides were also suitable coupling partners provided that P(2-furyl)3 was used as the supporting ligand for palladium (entries 6-8).30b This modification of the catalyst system minimized competing N-alkenylation of the substrate. Importantly, the E or Z stereochemistry of the alkenyl halide was preserved in the pyrrolidine product.

Table 4.

N-Aryl pyrrolidine synthesis

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

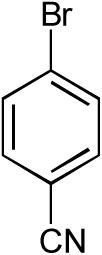

| Entry | R | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | Ligand | Ratio 35:36 | dr | Yielda |

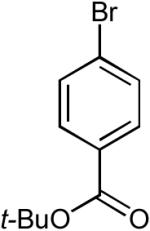

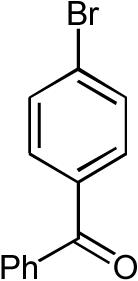

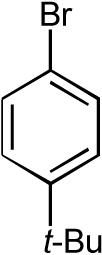

| 1 |  |

OMe | H | H | H | Dppb | 35:1 | - | 75% |

| 2 |  |

CN | H | H | H | Dppb | >100:1 | - | 86% |

| 3 |  |

OMe | Me | H | H | Dppe | 10:1 | >20:1 | 66% |

| 4 |  |

OMe | H | Ph | H | Dppe | 8:1 | 2:1 | 88% |

| 5 |  |

OMe | H | H | Ph | Dppe | 10:1 | >20:1 | 68% |

| 6 |  |

H | H | H | H | P(2-furyl)3 | >20:1 | - | 88% |

| 7 |  |

OMe | Me | H | H | P(2-furyl)3 | 7:1 | >20:1 | 79% |

| 8 |  |

OMe | H | H | Ph | P(2-furyl)3 | >20:1 | 10:1 | 55% |

Conditions: 1.0 equiv amine, 1.1-2.0 equiv R-Br, 1.2 equiv NaOtBu, 1 mol % Pd2(dba)3, 2-4 mol % ligand, toluene (0.25 M), 60-110 °C.

In addition to the desired pyrrolidine 35, these transformations also generated small amounts of regioisomers that had been arylated/alkenylated at C3 (36). These products appear to be formed through a similar mechanism as the analogous 3-aryl-2-ethyltetrahydrofuran side products (18) described in Scheme 4. In some instances the formation of small amounts of side products resulting from reduction of the aryl or alkenyl bromide substrates were also observed.

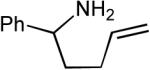

3.1 Tandem Pd-Catalyzed N-Arylation/Carboamination Reactions of Primary Amines

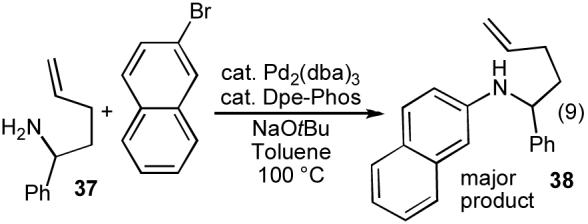

In order to further expand the scope of our carboamination chemistry, we sought to transform primary N-(4-pentenyl)amine substrates to 2-benzylpyrrolidine derivatives lacking N-substituents. Due to the volatility of 4-pentenylamine, we chose to initially examine reactions of 2-phenyl-4-pentenylamine (37). Unfortunately, catalysts that provided excellent results with the related N-arylated substrates shown in Table 4 (Pd2(dba)3/dppb or dppe) were not effective for the carboamination of 37 with 2-bromonaphthalene, and the bulk of the starting materials did not react.31 Use of a catalyst composed of Pd2(dba)3 and Dpe-phos led to consumption of starting material, but the major product (38) resulted from simple N-arylation of the substrate (eq 9).

|

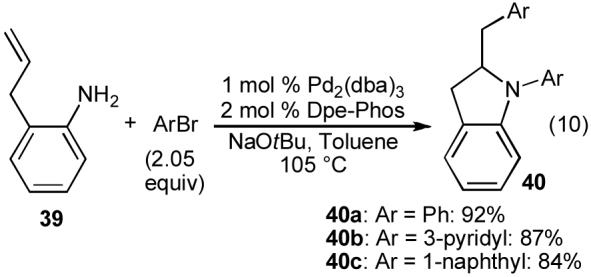

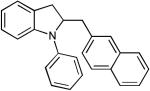

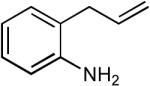

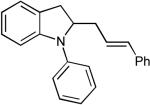

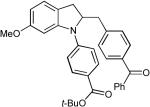

Although we were unsuccessful in our efforts to convert 37 to the desired NH pyrrolidine product, we wondered if it might be possible to develop conditions to effect a one-pot N-arylation/carboamination reaction of primary amines. In order to maximize our likelihood of success, and to minimize other factors that could complicate analysis of reaction mixtures, we elected to examine coupling reactions between bromobenzene (2.05 equiv) and the simple, non-volatile, achiral substrate 2-allylaniline (39) in our preliminary studies. Use of dppb or dppe as ligands for this transformation again provided unsatisfactory results. However, we were pleased to find that use of Dpe-phos as a ligand afforded N-phenyl-2-benzylindoline (40a) in 92% yield (eq 10).32a A number of other aryl bromides were also coupled with 2-allylaniline to provide N-aryl-2-benzylindoline derivatives (e.g. 40b-c) in high yield.

|

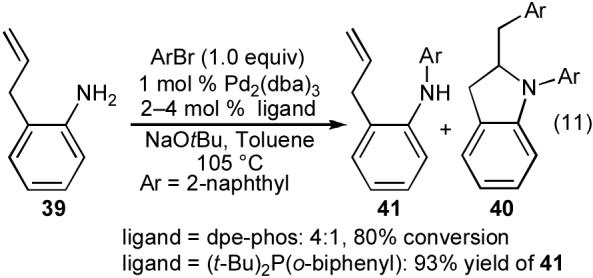

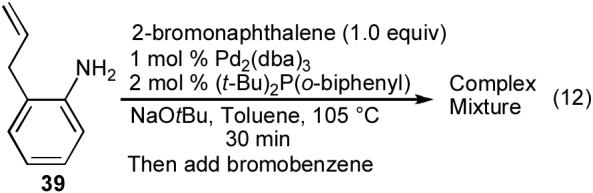

Our successful synthesis of indolines containing two identical aryl groups such as 40a-c prompted us to explore the preparation of related compounds bearing two different aryl groups. However, treatment of 2-allylaniline with 1 equiv of 2-bromonaphthalene using the conditions shown above afforded a mixture of mono- and diarylated products 41 and 40. We were able to obtain high selectivity for monoarylated product 41 when (t-Bu)2P(o-biphenyl) was employed as the ligand (eq 11). However, attempts to sequentially add two different aryl bromides to 39 using the Pd2(dba)3/(t-Bu)2P(o-biphenyl) catalyst led to the formation of complex mixtures of products (eq 12). Thus, it appeared that the catalyst providing optimal selectivity for the first step of the sequence (N-arylation of 39) did not function well in the second step (carboamination of 41).

|

|

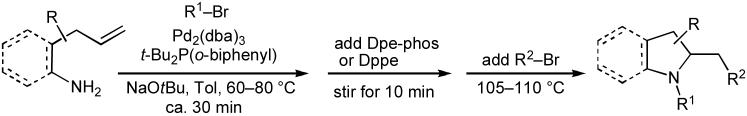

Fortunately, we were able to solve this problem by taking advantage of the fact that the monodentate ligand (t-Bu)2P(o-biphenyl) worked well for the N-arylation, a chelating ligand (Dpe-phos) was effective for the carboamination, and displacement of a monodentate ligand from a metal by a chelating ligand should be a favorable process. As such, we developed an in situ ligand exchange protocol that effected modification of the catalyst structure under the reaction conditions. By simply monitoring the reaction progress and then adding a small amount (2 mol %) of Dpe-phos to the reaction mixture after the first aryl bromide was consumed we were able to obtain excellent yields of the desired indoline products; representative examples are shown in Table 5 (entries 1-3).30b,32a A similar strategy ultimately proved effective for the conversion of primary aliphatic amine substrates to N-aryl-2-benzylpyrrolidine derivatives (entries 4-5).32b The chelating ligand dppe generally provided the best results for the carboamination step of these latter transformations.

Table 5.

Tandem Pd-catalyzed N-arylation/carboamination

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Substrate | R1-Br | R2-Br | Product | dr | Yielda |

| 1 |  |

|

|

|

- | 88% |

| 2 |  |

|

|

|

- | 69% |

| 3 |  |

|

|

|

- | 78% |

| 4 |  |

|

|

|

>20:1 | 68% |

| 5 |  |

|

|

|

9:1 | 71% |

Conditions: 1.0 equiv amine, 1.0 equiv R1-Br, 2.1-2.4 equiv NaOtBu, 0.5-1.0 mol % Pd2(dba)3, 1.0-2.0 mol % (t-Bu)2P(o-biphenyl), toluene (0.125-0.25 M), 60-80 °C. Stir until R1-Br is consumed. Then add 2 mol % Dpe-phos (aromatic amines) or dppe (aliphatic amines). Stir 10 min, then add 1.0-1.2 equiv R2-Br, heat to 105-110 °C.

3.2 Pd-Catalyzed Carboamination Reactions of N-Protected γ-Aminoalkenes

Despite the utility of the Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions described above for the synthesis of N-aryl pyrrolidines, it was unclear that we would be able to access N-H or N-alkyl pyrrolidines using this transformation. We had been unsuccessful in our attempts to carry out carboamination reactions of primary γ-amino alkenes (eq 9), and removing aryl groups from amines is not a simple task. Methods have been developed to effect the cleavage of p-methoxyphenyl protecting groups from amines, but deprotection of these compounds can be difficult.33 In addition, we had observed the best regioselectivities in transformations of substrates bearing N-(p-cyanophenyl) substituents, which cannot easily be cleaved to liberate “unprotected” products.

Due to the problems with N-aryl “protecting groups” outlined above, we sought to identify more traditional nitrogen protecting groups, such as amides or carbamates, that would be compatible with the carboamination chemistry. In addition to providing a means to access N-alkyl and/or N-H pyrrolidines, we felt the use of these electron-withdrawing protecting groups could potentially address two other limitations of the carboamination reactions: regioselectivity and functional group tolerance. We reasoned that substrates bearing electron-withdrawing protecting groups might be converted to 2-benzylpyrrolidine derivatives with high regioselectivity, as excellent regioselectivities were obtained in reactions of γ-(N-arylamino)alkene substrates with electron-poor N-aryl groups. Moreover, the NH proton of amides and carbamates is relatively acidic (pKa = 23-26 in DMSO) compared to that of aniline (pKa = 30.6 in DMSO).34 This increased acidity might allow for use of relatively weak bases in the carboamination reactions, which could result in improved functional group tolerance.

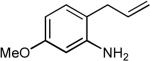

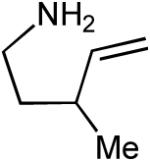

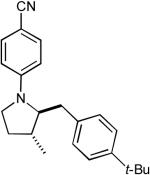

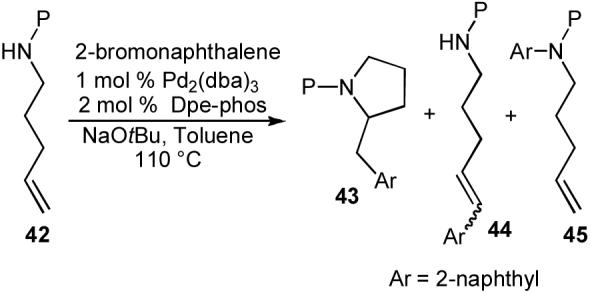

To probe the feasibility of conducting carboamination reactions of N-protected γ-aminoalkenes, we elected to initially explore the reactivity of 4-pentenylamine derivatives (42) bearing different nitrogen protecting groups. NaOtBu was selected as the base for these experiments, as this base had provided optimal results in our other carboamination and carboetherification reactions. A quick survey of ligands in reactions of N-acyl-4-pentenylamine indicated that bis-phosphines with relatively wide bite angles provided good results. Thus, Dpe-phos was used as the ligand for our protecting group study. As shown in Table 6, the efficiency of these reactions was highly dependent on the nucleophilicity/basicity of the substrate amino group. Varying amounts of desired pyrrolidine 43 and undesired side products that result from competing Heck arylation (44) or N-arylation (45) of the starting material were generated. Poor yields of 43 were obtained with an electron-rich N-benzyl protected substrate and with a very electron-poor p-trifluoromethylbenzoyl protected substrate. However, satisfactory results were obtained with 4-pentenylamines bearing N-boc- or N-acyl protecting groups. These substrates were transformed to the desired pyrrolidine products (43) in good yields with excellent regioselectivities.35a

Table 6.

Protecting group effects

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| P | GC ratioa,b (isolated yield) | ||

| 43 | 44 | 45 | |

| Bn | 0 | 40c | 34 |

| Ac | 88 (72%) | 12 | 0 |

| Boc | 82 (77%) | 4c | 0 |

| 4-MeO-Bz | 77 (63%) | 23 | 0 |

| Bz | 58 (48%) | 42 | 0 |

| 4-F3C-Bz | 0 | 89c | 0 |

Conditions: 1.0 equiv amine, 1.2 equiv 2-bromonaphthalene, 1.2 equiv NaOtBu, 1 mol % Pd2(dba)3, 2 mol % Dpe-phos, toluene (0.25 M), 110 °C.

Small amounts of other products were also observed.

Alkene stereoisomers and regioisomers were obtained.

After suitable protecting groups were identified, we sought to further optimize reaction conditions to allow for the use of relatively weak bases in these transformations. Our optimization studies indicated that the nature of both the solvent and the precatalyst had a significant impact on reactivity when weak bases were employed. After considerable experimentation, we arrived at optimized conditions in which Cs2CO3 was used as the base, dioxane or dme as the solvent, and Pd(OAc)2 as the source of palladium.35b Under these conditions, several ligands with wide bite angles (e.g. Dpe-phos, Xantphos, and NiXantphos)23 provided satisfactory results.

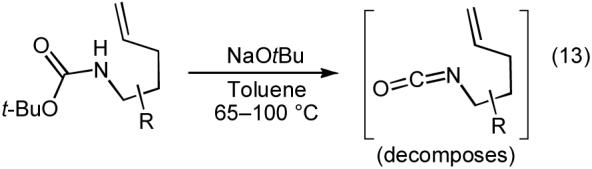

Representative examples of Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions of N-boc and N-acyl protected γ-aminoalkenes are shown in Table 7. All products were formed as single regioisomers, and these transformations can be used to generate cis-2,5- and trans-2,3-disubstituted pyrrolidines (entries 5-10) with good to excellent diastereoselectivity. The main side products observed in these reactions result from competing Heck-arylation of the alkene (e.g. 44),10 or from decomposition of staring materials containing carbamate protecting groups. These substrates undergo base-mediated eliminations to provide isocyanates, which react further and/or decompose (eq 13).36 In general, use of NaOtBu leads to increased amounts of products derived from substrate decomposition, whereas use of Cs2CO3 results in increased generation of Heck-arylation side products.

|

Table 7.

Synthesis of N-protected pyrrolidines

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R | P | R1 | R2 | Base | Solvent | Pd-Source | Liganda | drb | Yield |

| 1 |  |

Boc | H | H | NaOtBu | Toluene | Pd(OAc)2 | Dppe | - | 75%c |

| 2 |  |

Boc | H | H | Cs2CO3 | DME | Pd(OAc)2 | Dpe-phos | - | 76% |

| 3 |  |

Ac | H | H | NaOtBu | Toluene | Pd2(dba)3 | Xantphos | - | 67% |

| 4 |  |

Cbz | H | H | Cs2CO3 | DME | Pd(OAc)2 | Dpe-phos | - | 88% |

| 5 |  |

Boc | Ph | H | NaOtBu | Toluene | Pd2(dba)3 | Dppb | >20:1 | 60% |

| 6 |  |

Boc | Ph | H | Cs2CO3 | Dioxane | Pd(OAc)2 | Dpe-phos | >20:1 | 75% |

| 7 |  |

Ac | Ph | H | NaOtBu | Toluene | Pd2(dba)3 | Dppb | >20:1 | 82% |

| 8 |  |

Boc | H | Me | Cs2CO3 | Dioxane | Pd(OAc)2 | Dpe-phos | 15:1 | 76% |

| 9 |  |

Ac | H | Me | NaOtBu | Toluene | Pd2(dba)3 | Dpe-phos | >20:1 (10:1) | 61% |

| 10 |  |

Cbz | H | Me | Cs2CO3 | Dioxane | Pd(OAc)2 | Dpe-phos | 12:1 | 80% |

Conditions: 1.0 equiv amine, 1.1-1.2 equiv R-Br, 1.2-2.3 equiv base, 1 mol % Pd2(dba)3 or 2 mol % Pd(OAc)2, 2-4 mol % ligand, toluene or dioxane or dme (0.25 M), 85-105 °C.

Diastereomeric ratios are for isolated products. Diastereomeric ratios observed in crude reaction mixtures are given in parentheses if they changed upon isolation.

The reaction was conducted at 65 °C.

The carboamination reactions can be conducted with a number of different aryl bromide coupling partners that are electron-rich, electron-neutral, electron-poor, or heteroaromatic (Table 7).35 Alkenyl halides can also be employed as coupling partners, although competing N-alkenylation can be problematic. However, use of dppe as a ligand minimizes this side reaction, and 2-allylpyrrolidine derivatives can be prepared in good yield (entry 1).

Although functional group tolerance is modest when NaOtBu is employed as the base, use of Cs2CO3 leads to greatly improved functional group tolerance, and products bearing methyl esters, alkyl acetates, enolizable ketones, and nitro groups can be prepared under these relatively mild conditions. In addition, the use of Cs2CO3 allows for transformations of N-Cbz-protected substrates, which rapidly decomposed when NaOtBu was employed as the base.

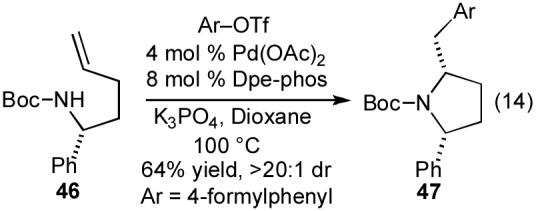

The development of reaction conditions involving weak bases has also expanded the scope of this method to allow the coupling of aryl triflate electrophiles. These compounds decompose to the corresponding phenols when NaOtBu is employed as base, but substitution of the mild base K3PO4 for NaOtBu allows for the conversion of N-protected γ-aminoalkenes and aryl triflates to 2-benzylpyrrolidine derivatives in good yield and diastereoselectivity. For example, treatment of 46 with 4-formylphenyl triflate and K3PO4 in the presence of the Pd(OAc)2/Dpe-phos catalyst provided 47 in 64% yield as a single diastereomer (eq 14).35b

|

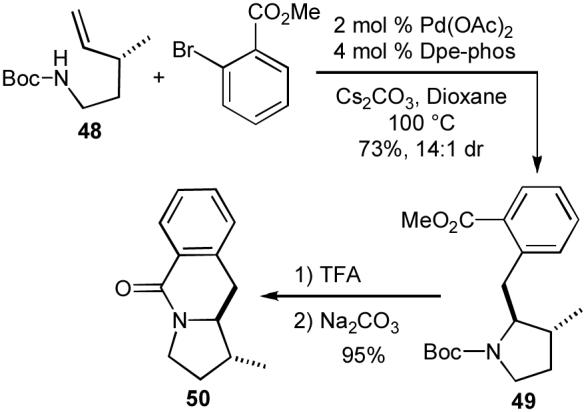

The extension of our carboamination reactions to N-protected γ-aminoalkenes has also allowed us to synthesize interesting compounds that we could not access using transformations of γ-N-(arylamino)alkenes. For example, we were able to generate tetrahydropyrroloisoquinolin-5-one 50 in good yield and diastereoselectivity by conducting a Pd-catalyzed carboamination of 48 with methyl-2-bromobenzoate, which provided 49 in 73% yield and 14:1 dr. Treatment of 49 with acid then base afforded 50 in 95% yield (Scheme 7).35b

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of tetrahydropyrroloisoquinolin-5-one 50

3.3 Mechanism of Pd-Catalyzed Carboamination Reactions: Surprises and Utility

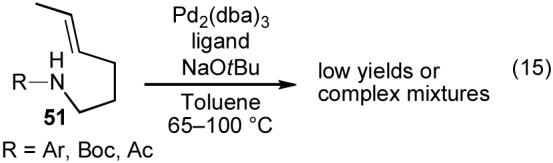

Many aspects of the Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions were quite similar to the tetrahydrofuran-forming carboetherification reactions. The conditions used in these transformations were nearly identical, and the γ-amino alkene substrates employed in the carboamination reactions were essentially nitrogen-containing variants of the substrates for tetrahydrofuran-forming reactions. Finally, carboamination reactions of N-arylated γ-aminoalkenes generated 3-aryl pyrrolidine side products (Table 4, 36) that were analogous to the 3-aryl tetrahydrofuran side products that were occasionally observed in the carboetherification reactions (Figure 1, 18). Thus, it seemed likely that the mechanism of the carboamination reactions was closely related to the mechanism for tetrahydrofuran formation shown above (Scheme 5). In order to provide further evidence to support (or perhaps refute) this hypothesis, we sought to examine carboamination reactions of internal alkene substrates to determine if products resulting from syn-addition would be formed. Unfortunately, our initial efforts to employ acyclic internal alkene substrates 51 were unsuccessful. Reactions of N-arylated derivatives provided complex mixtures of inseparable products, and reactions of N-boc or N-acyl protected derivatives gave very low yields due to competing substrate decomposition (eq 15).37

|

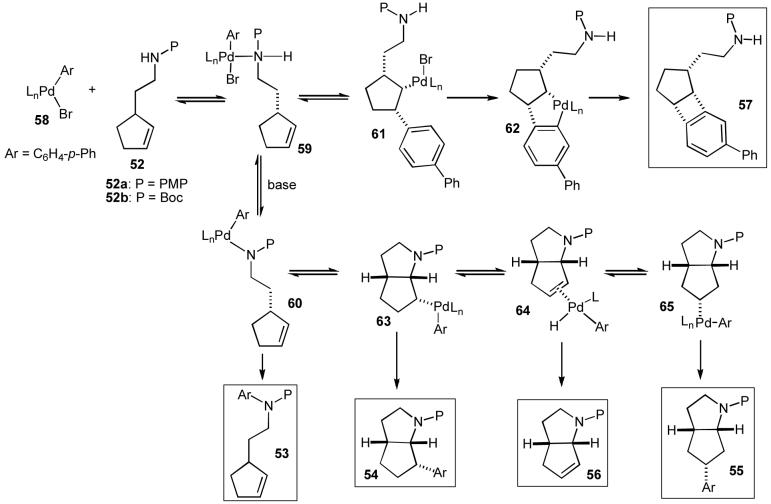

Although our efforts to effect Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions of acyclic internal alkenes were largely unsuccessful,37 when we examined transformations of N-protected cyclopent-2-enyl ethylamine derivatives (52a-b), very intriguing results were obtained. As shown below (eq 16), treatment of N-(4-methoxyphenyl)protected substrate 52a with 4-bromobiphenyl in the presence of a Pd2(dba)3/P(o-tol)3 catalyst and NaOtBu generated a mixture of four isolable products (53-56).30a The Pd-catalyzed reaction of boc-protected substrate 52b with 4-bromobiphenyl and NaOtBu provided only the expected product 54b, which results from syn-addition across the alkene, in moderate yield (eq 17).35a,38 However, use of Cs2CO3 as base and dioxane as solvent for the coupling of 52b with 4-bromobiphenyl led to formation of benzocyclobutene 57 rather than the expected pyrrolidine 54b (eq 18).38,39

In order to explain the origin of products 53-57 we proposed the following hypothesis (Scheme 8).30a,35a,40 It appears likely that the pyrrolidine-forming reactions are mechanistically analogous to the tetrahydrofuran-forming reactions insofar as both transformations involve syn-insertion of an alkene into the Pd-heteroatom bond of intermediate palladium(aryl)(alkoxide) or palladium(aryl)(amido) complexes. This intermediate is generated by oxidative addition of the aryl bromide to Pd(0) followed by formation of the Pd-heteroatom bond as described previously (Scheme 1, Path D). The Pd-N bond-forming step is likely to be reversible, and the position of the equilibrium presumably is related to both the acidity of the NH proton and the strength of the base used in the reaction.13,41,42 In addition, the alkene insertion step may be reversible,43 and it is likely that both the rate of insertion and the position of this equilibrium depend on the basicity, nucleophilicity, and/or leaving group ability of the amino group, as well as the steric encumbrance of both the alkene and the complex formed after aminopalladation.

|

Scheme 8.

Mechanistic hypothesis

For example, in the case of the transformations of 52b shown in eq 17-18, oxidative addition of 4-bromobiphenyl to Pd(0) would afford 58. Coordination of the nitrogen atom to the metal would provide 59, which could be deprotonated to yield 60.42 When a relatively weak base (e.g. Cs2CO3, eq 18) is employed in these reactions, the equilibrium between 59 and 60 presumably lies towards 59, and the deprotonation of 59 may also be kinetically slow due to the insolubility of Cs2CO3.41 In addition, the combination of steric encumbrance of intermediate 63 with the relatively good leaving group ability of a carbamate anion may drive the equilibrium between 63 and 60 towards 60. For these reasons, it appears that when boc-protected substrate 52b is subjected to carboamination reaction conditions with the weak base Cs2CO3 the formation of intermediate 63 is kinetically and/or thermodynamically unfavorable. Under these conditions, complex 59 may undergo directed carbopalladation44 to provide 61, which lacks β-hydrogen atoms with a syn relationship to the metal. Intermediate 61 is then further transformed via aromatic C-H activation45 followed by C-C bond forming reductive elimination from the resulting intermediate 62 to generate the observed benzocyclobutene 57.

In contrast, use of a strong, soluble base (e.g. NaOtBu, eq 17) in the reaction of 52b likely increases the rate of deprotonation and also drives the 59-60 equilibrium towards 60.41 This intermediate undergoes selective syn-alkene insertion into the Pd-N bond to yield 63, followed by C-C bond-forming reductive elimination to provide the expected product 54. Competing β-hydride elimination from 63 to afford 64 appears to be relatively slow when P = Boc, which may be due to stabilizing coordination of the carbamate carbonyl to the metal.46,47 Competing C-N bond-forming reductive elimination from 60 to provide 53 is also slow when P = Boc due to the relatively low nucleophilicity of the nitrogen atom.13 Thus, substrate 52b is selectively converted to 54 under these conditions.

With the relatively electron-rich PMP-protected substrate 52a (eq 16) the reactivity of intermediates 60 and 63 changes considerably. The increased nucleophilicity of the p-methoxyaniline nitrogen atom (relative to a carbamate) increases the facility of C-N bond-forming reductive elimination from 60,13 which leads to product 53. In addition, β-hydride elimination from 63 to generate 64 also appears to be more facile with the PMP-protected derivative. From complex 64, displacement of the alkene from the metal affords observed alkene product 56. Alternatively, reinsertion of the alkene into the Pd-H bond of 64 with the opposite regiochemistry provides 65, which can undergo C-C bond-forming reductive elimination to yield 55.

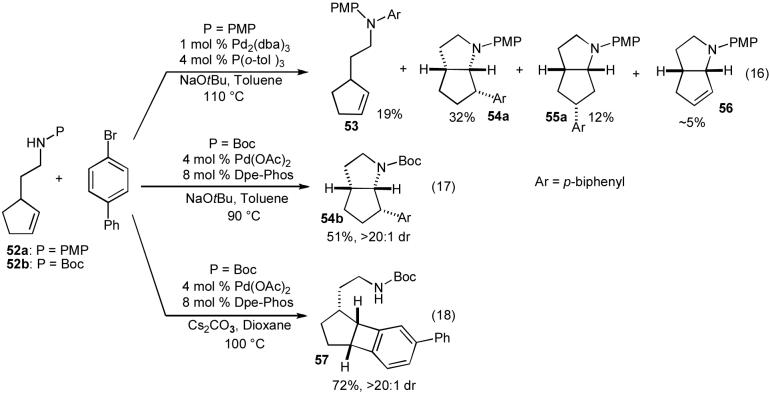

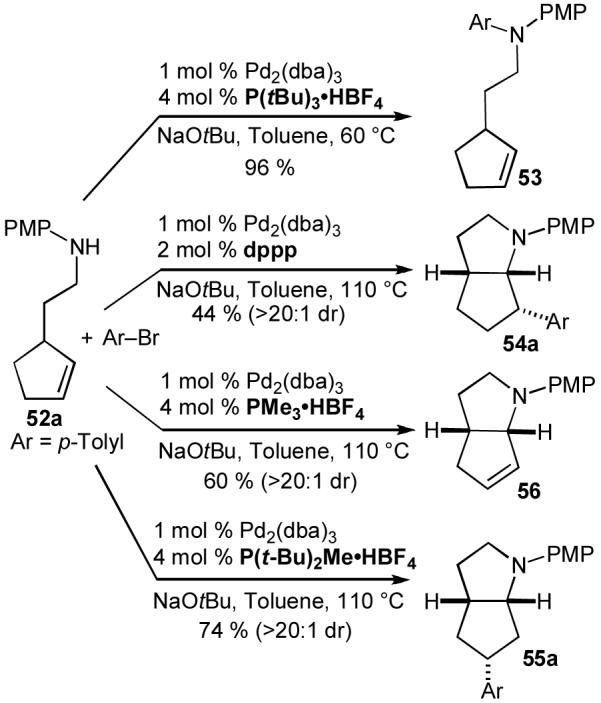

The mechanistic hypothesis outlined above suggested to us that it might be possible to tune the reactivity of the palladium catalyst used in the coupling of PMP-protected substrate 52a such as to allow for selective formation of any one of the four products 53-56.40 A few general principles concerning the effect of phosphine ligands on the rates of fundamental organometallic transformations guided our optimization studies. First of all, sterically bulky ligands facilitate reductive elimination whereas small ligands inhibit reductive elimination.13,48 Therefore, a very bulky ligand might be expected to facilitate rapid reductive elimination from 60 to selectively form 53. In contrast, a very small ligand might be expected to slow the reductive elimination processes that lead to 53, 54, 55, and thereby provide selectivity for 56.

Two facts suggested that it might be possible to selectively generate 5-aryl azabicyclo[3.3.0]octane 54a from 52a. Chelating ligands slow the rate of β-hydride elimination from metal complexes,49 and C-C bond-forming reductive elimination is typically faster than C-N bond-forming reductive elimination.13 Therefore, a chelating (or pseudo-chelating) ligand with the proper steric and electronic properties might minimize C-N bond forming reductive elimination from 60 and β-hydride elimination from 63 without completely inhibiting C-C bond-forming reductive elimination to yield 54a.

Finally, the ligand substitution process that liberates alkene 56 from complex 64 is likely to proceed via an associative mechanism,50 in which reaction of an external nucleophile with 64 is required to displace 56. Therefore, ligands that are electron-rich and of moderate size might disfavor formation of 56. Under these conditions, it seemed likely that 55 would be generated as the major product because intermediate complex 65 appeared to be more thermodynamically stable than 63 due to a steric interaction between the N-PMP group and the metal fragment in 63.

After some experimentation we found that use of an appropriate phosphine ligand allowed for selective coupling of 52a with 4-bromotoluene to afford either 53, 55a, or 56 in moderate to good yield with excellent diastereoselectivity (Scheme 9). The selectivity for formation of 54a was modest, as competing N-arylation afforded a roughly 1:1 mixture of 53 and 54a under optimal conditions. However, we were able to improve selectivity for this regioisomer by replacing the N-p-methoxyphenyl group with a N-p-cyanophenyl group (Table 8, entry 1). Subsequent experiments revealed that a number of N-aryl-5- and 6-aryl azabicyclo[3.3.0]octane derivatives could be prepared in good yield using the concepts described above. Representative examples of these transformations are shown in Table 8; all products were obtained with >20:1 dr.40

Scheme 9.

Selective conversion of 52a to 53-56

Table 8.

Synthesis of azabicyclo[3.3.0]octanes

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R | Ar | R1 | R2 | Yielda |

| 1b | CN | p-C6H4Me | H | Ar | 69% |

| 2b | CO2t-Bu | p-C6H4OMe | H | Ar | 58% |

| 3c | H | p-C6H4CN | Ar | H | 76% |

| 4c | Cl | p-C6H4CO2t-Bu | Ar | H | 71% |

Conditions: 1 equiv amine, 1.4 equiv ArBr, 1.2 equiv NaOtBu, 1 mol % Pd2(dba)3, 2 mol % ligand, toluene (0.25 M), 110 °C. All products were obtained with >20:1 dr.

Ligand = 2-diphenylphosphino-2′-(N,N-dimethylamino)biphenyl.

Ligand = P(t-Bu)2Me·HBF4.

In addition to the synthetic utility of the transformations described above, our studies on Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions of N-aryl and N-boc cyclopent-2-enylethylamines provided further evidence in support of a mechanism for pyrrolidine formation that involves syn-insertion of an alkene into a Pd-N bond as a key step. The products of the reactions shown in eq 16-17, Scheme 9, and Table 8 all result from net syn-addition of the aryl group and the amino moiety across the alkene. Moreover, the ligand, base, and protecting group effects described above, along with a considerable amount of data generated in reactions involving other phosphine ligands,40 are best explained by this mechanistic proposal.

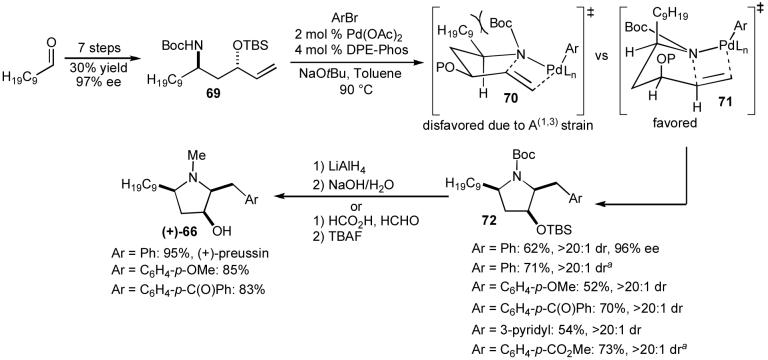

3.4 Application of Pd-Catalyzed Carboamination of N-Protected γ-Aminoalkenes to the Stereoselective Synthesis of (+)-Preussin and Analogs

In order to demonstrate the synthetic utility of Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions of N-protected γ-aminoalkenes for applications in target oriented synthesis, we sought to apply this transformation to the construction of a natural product. The 3-hydroxypyrrolidine alkaloid (+)-preussin (Figure 2, 66)51 appeared to be a very attractive target to pursue as an initial application for several reasons. This molecule has long been known for its antifungal properties, and more recent screens have also indicated that preussin has antiviral and antitumor activity, and is a selective inhibitor of cyclin-E kinase.52 In addition to the interesting biological activity of this compound, we felt that our approach to the synthesis of (+)-preussin would have significant advantages over prior strategies used for its construction. Most previously reported syntheses of preussin install the aryl moiety early in the sequence, and are not generally amenable to the rapid generation of analogs bearing different aryl groups.53,54 In contrast, our alkene carboamination strategy would allow for installation of the aryl group towards the end of the synthesis, and would serve as a means to prepare new, previously inaccessible analogs that may also have interesting biological activities.

Figure 2.

(+)-Preussin

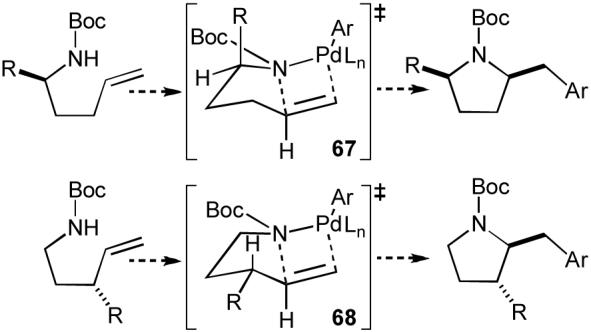

Our proposed route to preussin also raised an interesting question about stereocontrol in carboamination reactions of relatively complicated substrates. The three substituents on the pyrrolidine ring of preussin, located at C2, C3, and C5, are oriented cis to one another. We had previously found that reactions of substrates substituted at C1 provided cis-2,5-disubstituted pyrrolidines (e.g. Table 7, entries 5-7) with high diastereoselectivity (>20:1 in all cases examined). This selectivity presumably arises from cyclization through transition state 67, in which the C1-substituent is oriented in a pseudoaxial position to minimize A(1,3)-strain (Scheme 10).55 Importantly, the relative stereochemistry between the 2- and 5-substituents on preussin was identical to that obtained in carboamination reactions of simple substrates.

Scheme 10.

Pyrrolidine stereochemistry

In contrast, our prior experiments also demonstrated that substrates bearing substituents at the allylic position (e.g. Table 7, entries 8-9) were converted to trans-2,3-disubstituted products with good diastereoselectivity (10 to 15:1). These reactions likely proceed through transition state 68, in which the allylic substituent is oriented in a pseudoequatorial position. Therefore, the relative stereochemistry between the 2- and 3-substituents on preussin is opposite of the stereochemistry typically obtained our carboamination reactions. In order to obtain the correct stereoisomer needed to prepare preussin, the effect of the substituent adjacent to the substrate nitrogen atom would need to dominate over the effect of the allylic substituent. However, this seemed possible, as the allylic group appeared to impart lower inherent control over stereochemistry. The diastereoselectivities of our carboamination reactions that afforded 2,3-disubstituted products were typically slightly lower than transformations that yielded 2,5-disubstitued products. Moreover, the substrate needed to prepare preussin would contain a relatively large alkyl group on C1, whereas the allylic substituent would be a relatively small ether group, which should further favor formation of the correct stereoisomer needed to prepare the natural product.

Fortunately, our hypothesis concerning the relative influence of the substrate substituents on the stereochemical outcome of the key Pd-catalyzed carboamination reaction proved to be correct. As shown below (Scheme 11), we have developed a concise route for the synthesis of (+)-preussin that effects installation of the aryl group one step from the final target.56 The key intermediate in our synthesis is a protected trans-1,3-amino alcohol derivative (69), which is generated in seven steps and 30% overall yield from decanal. This intermediate was converted to pyrrolidine 72 (Ar = Ph) in 62% yield with >20:1 dr through a Pd(OAc)2/Dpe-phos catalyzed carboamination reaction with bromobenzene. The major diastereomer appears to result from cyclization via transition state 71, in which the C9-chain is oriented in a pseudoaxial position to avoid an unfavorable A(1,3)-strain interaction with the carbamate protecting group (transition state 70). Finally, the pyrrolidine 72 (Ar = Ph) was converted to the natural product 66 through a one-pot reduction and deprotection sequence using LiAlH4 followed by workup with aqueous base.

Scheme 11.

Synthesis of (+)-preussin and analogs

a. The reaction was conducted using Cs2CO3 as base and dioxane as solvent.

The route shown in Scheme 11 also allows for facile generation of preussin analogs bearing different aryl groups. In all cases the pyrrolidine products are obtained with excellent diastereoselectivity and good chemical yield. The transformations are effective using either NaOtBu or Cs2CO3 as base,35b,56 which allows for the synthesis of functionalized derivatives. The reduction/deprotection sequence can also be carried out using mild conditions (formic acid/formaldehyde followed by TBAF) that tolerate the presence of sensitive functional groups.

4 Synthesis of Imidazolidin-2-ones via Pd-Catalyzed Carboamination Reactions

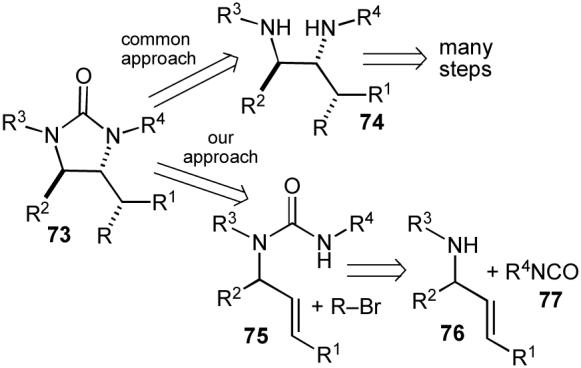

Having successfully developed a new synthesis of tetrahydrofurans and pyrrolidines via carboetherification or carboamination reactions of alkenes bearing pendant heteroatoms, we began to explore the possibility of extending the scope of these transformations to the construction of other interesting heterocycles that contain more than one heteroatom. We elected to begin our investigations in this area by developing a new synthesis of imidazolidin-2-ones.57 These cyclic ureas are very attractive targets due to their importance in pharmaceutical and medicinal chemistry. For example, several very potent HIV protease inhibitors contain cyclic urea moieties,58 and these scaffolds are also displayed in 5-HT3-receptor antagonists59 and NK1 antagonists.60 In addition, imidazolidin-2-ones have been employed as chiral auxiliaries,61 and as intermediates in the synthesis of amino acids and 1,2-diamines.62

Although a number of methods have been developed for the generation of cyclic ureas such as imidazolidin-2-ones (73),63 the most common strategy involves the often cumbersome synthesis of 1,2-diamines (74) followed by catalytic or reagent-based carbonylation reactions that install the carbonyl group (Scheme 12). In contrast, we felt that Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions of acyclic N-allylureas (75) with aryl/alkenyl halides would provide a simple means of preparing imidazolidin-2-ones from readily available precursors: allylic amines (76) and isocyanates (77). This strategy would provide the desired compounds in only two steps, and should allow for installation of different groups at several positions on the ring.64

Scheme 12.

Retrosynthesis of imidazolidin-2-ones

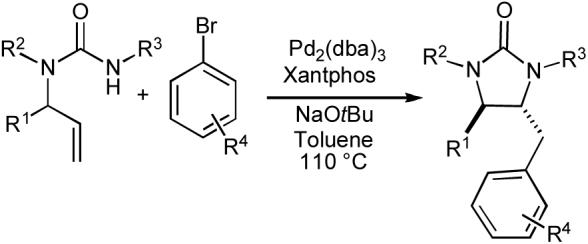

In order to establish the feasibility of using Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions for urea synthesis, we prepared N1-phenyl-N3-ethyl-N3-allylurea from N-allylaniline and ethyl isocyanate (92% yield) and examined its reactivity towards p-bromotoluene in the presence of NaOtBu and a palladium catalyst. After minimal optimization we found that the use of standard carboamination conditions along with the bisphosphine ligand Xantphos23 provided the desired imidazolidin-2-one in 59% isolated yield (Table 9, entry 1). The modest yield obtained in this reaction was due to competing base-mediated decomposition of the substrate. Fortunately, when the substituents on the nitrogen atoms of the urea substrate were modified, excellent yields were obtained. Representative examples of these transformations are shown below.

Table 9.

Synthesis of imidazolidin-2-ones

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | drb | Yielda |

| 1 | H | Ph | Et | p-Me | - | 59% |

| 2 | H | Bn | PMP | o-Me | - | 71% |

| 3 | Me | Bn | PMP | p-CN | 12:1 (8:1) | 88% |

| 4 | (CH2)3 | PMP | m-CF3 | >20:1 | 87% | |

| 5 | (CH2)4 | PMP | H | 20:1 (11:1) | 78% | |

Conditions: 1.0 equiv substrate, 1.2 equiv ArBr, 1.2 equiv NaOtBu, 1 mol % Pd2(dba)3, 2 mol % Xantphos, toluene (0.25 M), 110 °C.

Diastereomeric ratios are for isolated products. Diastereomeric ratios observed in crude reaction mixtures are given in parentheses if they have changed upon isolation.

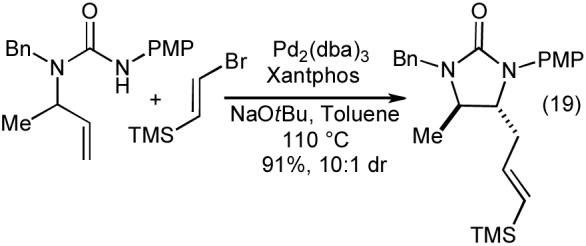

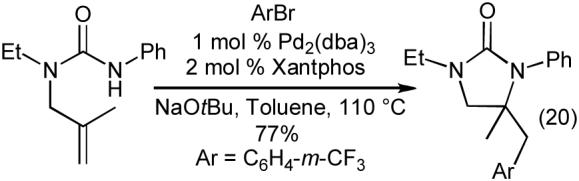

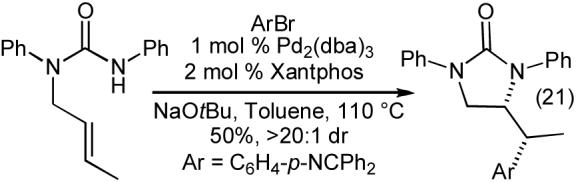

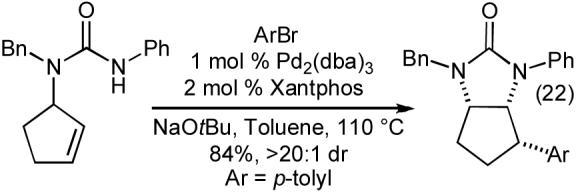

The carboamination reactions of N-allylureas are effective with a number of different aryl and heteroaryl bromides (Table 9), as well as alkenyl bromides (eq 19). Substrates bearing an allylic substituent are converted to trans-4,5-disubstituted imidazolidin-2-ones with good to excellent diastereoselectivities (Table 9, entries 3-5 and eq 19). The Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions of N-allylureas can also be conducted using substrates bearing 1,1- or 1,2-disubstitued alkenes (eq 20-22). The transformations proceed with net syn-addition across the double bond, and appear to be mechanistically analogous to the pyrrolidine-forming carboamination reactions described above.

|

|

|

|

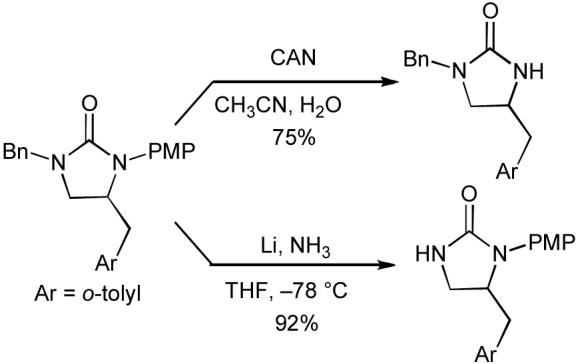

In general, the best yields of imidazolidin-2-one products are obtained when the N1-atom bears an aromatic group. Importantly, when the two nitrogen atoms are protected with a benzyl group and a p-methoxyphenyl group (e.g. entry 2), the protecting groups can be selectively cleaved from the product using Li/NH3 or CAN, respectively (Scheme 13).

Scheme 13.

Selective deprotection

5 Synthesis of Isoxazolidines via Pd-Catalyzed Carboetherification Reactions

The successful application of our carboamination chemistry to the synthesis of imidazolidin-2-one products gave us confidence that our Pd-catalyzed carboetherification reactions could also be employed for the synthesis of oxygen-containing heterocycles that contain more than one heteroatom. Isoxazolidines were very attractive targets for our first studies in this area, as these scaffolds are displayed in a variety of biologically active molecules.65 Isoxazolidines are also versatile intermediates in organic synthesis,66 and their N-O bonds can be cleaved under mild reducing conditions to afford 1,3-amino alcohols.67

Isoxazolidines are most commonly prepared using 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions between nitrones and alkenes.68 Although these reactions are generally quite efficient, formation of mixtures of regioisomers can be problematic in reactions of unactivated alkene substrates. In addition, the selective synthesis of isoxazolidine stereoisomers that result either from nitrone addition to an alkene in an exo fashion, or from nitrone addition to the more hindered face of an alkene is quite difficult.

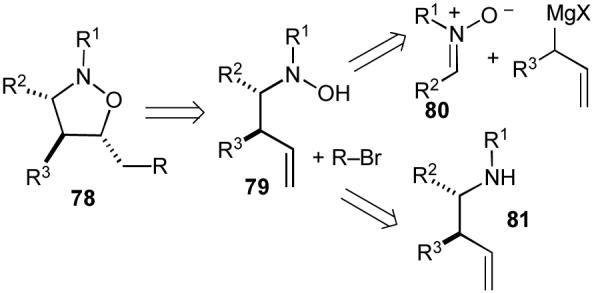

We envisioned that our approach to the synthesis of isoxazolidines (78) would involve Pd-catalyzed carboetherification reactions of N-butenylhydroxylamine derivatives (79). These substrates could be prepared as shown in Scheme 14 via addition of allylmagnesium bromide to an appropriate nitrone (80),69 or via oxidation of an N-butenylamine derivative (81).70 This strategy was expected to provide isoxazolidine products with excellent control of regioselectivity as observed in our related tetrahydrofuran-forming reactions.20 Moreover, the stereochemical model for the tetrahydrofuran-forming reactions20,24 suggested that we might be able to access some isoxazolidine stereoisomers that could not be prepared using dipolar cycloaddition chemistry. Finally, the key intermediate palladium(aryl)(alkoxide) complexes in these reactions (analogous to 8a in Scheme 5) would not contain β-hydrogen atoms. Thus, the problematic β-hydride elimination side reactions that we frequently encountered in our tetrahydrofuran-forming carboetherifications would not be problematic in the hydroxylamine carboetherification reactions.

Scheme 14.

Retrosynthetic analysis

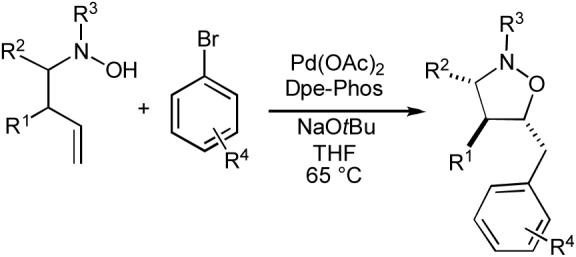

In our preliminary experiments we examined the reactivity of N-butenyl hydroxylamine and the corresponding N-boc- and N-benzyl-protected derivatives in Pd-catalyzed carboetherification reactions with 4-bromobiphenyl. We were gratified to discover that the N-benzyl protected substrate was transformed to the desired isoxazolidine in 80% yield using conditions that were very similar to those employed in tetrahydrofuran-forming reactions (Table 10, entry 1).71-74

Table 10.

Synthesis of isoxazolidines

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | drb | Yielda |

| 1 | H | H | Bn | p-Ph | - | 80% |

| 2 | Me | H | Bn | p-C(O)Ph | >20:1 (5:1) | 56% |

| 3 | H | Ph | t-Bu | p-Ph | 3:1 | 61% |

| 4 | H | (CH2)3 | o-Me | >20:1 (10:1) | 82% | |

| 5 | H | (CH2)4 | m-OMe | 19:1 (9:1) | 94% | |

Conditions: 1.0 equiv substrate, 1.2 equiv ArBr, 1.2 equiv NaOtBu, 2 mol % Pd(OAc)2, 2 mol % Dpe-phos, THF (0.125 M), 65 °C.

Diastereomeric ratios are for isolated products. Diastereomeric ratios observed in crude reaction mixtures are given in parentheses if they have changed upon isolation.

Having demonstrated the feasibility of our strategy for isoxazolidine synthesis, we proceeded to examine stereoselective reactions of substrates bearing substituents at the allylic or homoallylic position. As shown in Table 10 (entries 2-3), transformations of these substrates to monocyclic cis-3,5-disubstituted or trans-4,5-disubstituted isoxazolidines generally proceeded in good yield. However, the diastereoselectivities in these reactions were modest (ca 3 to 5:1). In contrast, reactions of pyrrolidine- or piperidine-derived N-butenyl hydroxylamines (entries 4-5) afforded products with much better diastereoselectivity (9 to 10:1). Importantly, the stereochemical outcome of these latter transformations is complementary to that of nitrone cycloaddition reactions. The Pd-catalyzed reactions favor formation of the (2R*, 3aS*) isomers, whereas dipolar cycloaddition reactions of pyrrolidine- or piperidine-derived nitrones with allylbenzene derivatives typically afford products with the (2S*, 3aS*) relative stereochemistry.75

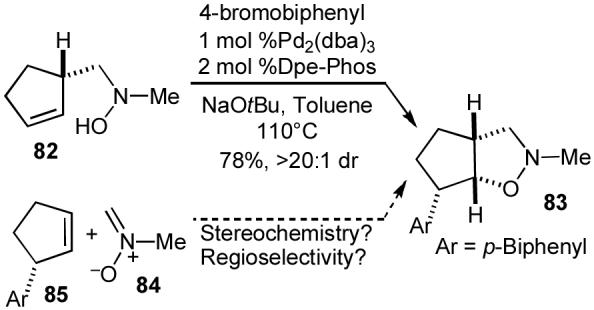

The conversion of cyclopentene derivative 82 to isoxazolidine 83 also highlights the complementarity of our strategy to traditional methods for isoxazolidine synthesis. As shown in Scheme 15, the major stereoisomer formed in this reaction would be very difficult to generate using dipolar cycloaddition chemistry,68 as nitrone 84 would need to attack the more sterically hindered face of a 2-substituted cyclopentene dipolarophile (85) with high regioselectivity in an electronically unbiased system.

Scheme 15.

Stereochemical complementarity

6 Synthesis of Piperazines via Pd-Catalyzed Carboamination Reactions

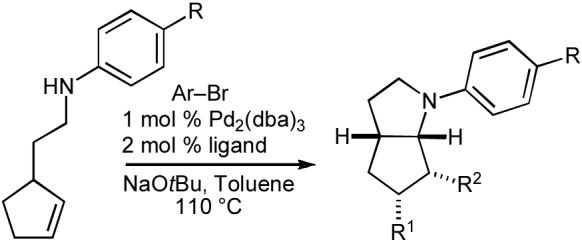

The vast majority of our work on Pd-catalyzed carboetherification and carboamination reactions has been directed towards the preparation of five-membered ring heterocycles. However, recently we have begun to explore the extension of this chemistry to the construction of larger rings. Our first studies to this end have involved the development of a new synthesis of piperazines using Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions. These molecules attracted our attention for several reasons. The piperazine scaffold is found in a large number of biologically active molecules, and plays an important role in medicinal chemistry and drug development.76 The presence of substituents around the ring has a large impact on biological activity,77 but some substitution patterns are difficult to access using existing synthetic methods. For example, the asymmetric construction of 2,6-dialkyl piperazines often requires at least six synthetic steps.78

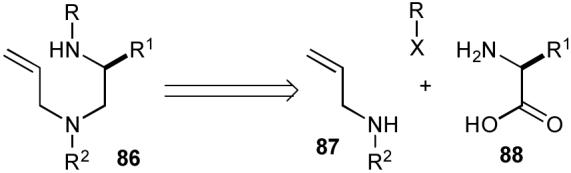

In addition to the biological significance of piperazines and the potential synthetic utility of a new method for their construction, the requisite substrates for the synthesis of piperazines via Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions had several attractive features. As shown in Scheme 16, it seemed likely that these substrates (86) could be constructed from three readily available precursors: enantiomerically pure amino acids (88), allylic amines (87), and aryl, acyl, or alkyl halides. In addition, it should be possible to tune both the reactivity of the substrate and the biological properties of the product by varying the N-substituents and the R1 group. Finally, it also seemed likely that the cyclization of these substrates could be facilitated by a Thorpe-Ingold type effect induced by the R2 substituent on the N4-atom.79

Scheme 16.

Retrosynthetic analysis of substrates for piperazine formation

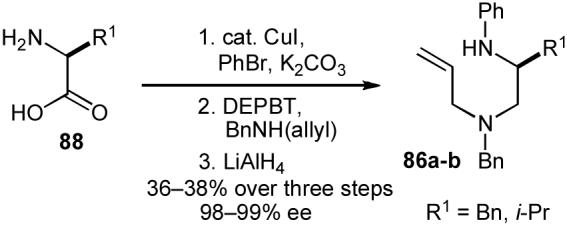

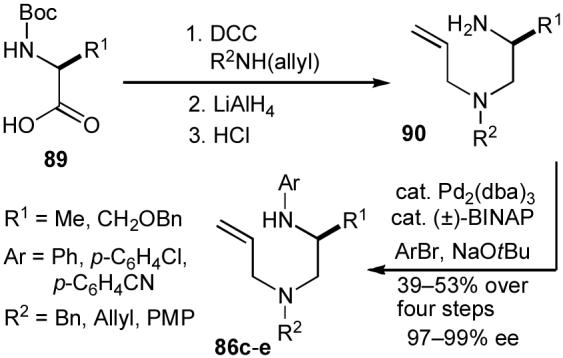

In order to begin our experiments, we first prepared a series of enantiopure substrates (86). As shown below, these compounds were synthesized via one of two routes. Unprotected amino acids (88) were converted to substrates 86a-b (Scheme 17) via Cu-catalyzed N-arylation80 followed by conversion to a N-allyl amide81 and reduction (36-38% yield over three steps). Alternatively, in some instances it was advantageous to use N-boc-protected amino acids (89) as starting materials due to their accessibility and/or ease of handling and purification of synthetic intermediates (Scheme 18). The protected amino acids 89 were transformed to diamines 90 via amide bond formation followed by reduction and cleavage of the boc-protecting group. Palladium-catalyzed N-arylation13 of 90 then afforded the desired compounds 86c-e in 39-53% yield over four steps. Both routes provided substrates with ee’s ranging from 97-99%.

Scheme 17.

Substrate synthesis 1.

Scheme 18.

Substrate synthesis 2.

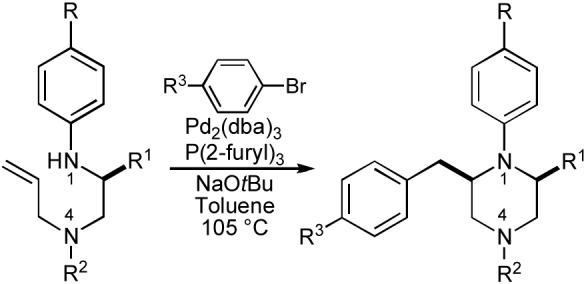

With substrates in hand, we proceeded to examine the Pd-catalyzed carboamination of 86a (R1 = Bn) with 1-bromo-4-t-butylbenzene. Interestingly, ligands such as dppb, dppe, Dpe-phos and Xantphos, which generally provided good results in pyrrolidine-forming reactions, afforded only modest yields of the desired piperazine derivative. After some optimization we discovered that the monodentate phosphine ligand P(2-furyl)3 gave the best results in this reaction, and the desired product was obtained in 63% yield with >20:1 dr (Table 11, entry 1).82 The enantiomeric purity of the substrate (99% ee) was retained in the product.83

Table 11.

Synthesis of enantiomerically enriched cis-2,6-disubstituted piperazines

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R | R1 | R2 | R3 | dr (ee) | Yielda |

| 1 | H | Bn | Bn | t-Bu | >20:1 (99%) | 63% |

| 2 | H | i-Pr | Bn | t-Bu | >20:1 (99%) | 51%b |

| 3 | CN | CH2OBn | Bn | CF3 | 14:1 (98%) | 69% |

| 4 | H | Me | Allyl | OMe | >20:1 (99%) | 53% |

| 5 | Cl | Me | PMP | H | >20:1 (99%) | 51% |

Conditions: 1.0 equiv amine, 1.2. equiv ArBr, 1.2 equiv NaOt-Bu, 1 mol % Pd2(dba)3, 8 mol % P(2-furyl)3, toluene (0.2 M), 105 °C.

The reaction was conducted using 2 mol % Pd2(dba)3 and 16 mol % P(2-furyl)3.

The Pd-catalyzed piperazine-forming reactions are effective with various combinations of amine substrates and aryl halide electrophiles. Representative examples are shown in Table 11. Importantly, the concise synthetic route and the broad availability of precursors allows for relatively facile incorporation of different groups at four positions on the ring. For example, substrates derived from several different amino acids, including phenylalanine (entry 1), valine (entry 2), serine (entry 3), and alanine (entries 4-5) are converted to the desired piperazine products with good to excellent diastereoselectivity, and uniform retention of enantiomeric purity (R1 = Bn, i-Pr, CH2OBn, or Me). Several different substituents can also be incorporated on N4, including benzyl, allyl, and p-methoxyphenyl groups. The cyclizing N1 atom can bear electron-neutral or electron-poor aromatic groups, and several electronically different aryl halide coupling partners can be used in these reactions to provide the fourth point of diversity.

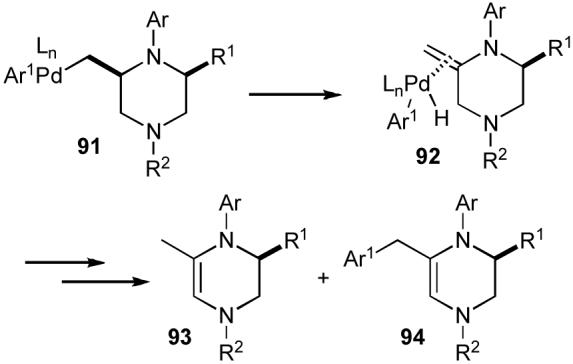

The major side products formed during the course of piperazine generation (93-94) appear to derive from competing β-hydride elimination from intermediate 91 to provide 92, which can then be further transformed to the observed side products (Scheme 19). This data suggests that the mechanism of the piperazine-forming reactions is closely related to that of the pyrrolidine-forming reactions described above (Scheme 1, path D).

Scheme 19.

Side products

7 Summary and Future Outlook

The development of Pd-catalyzed carboetherification and carboamination reactions over the past several years has led to a useful and straightforward approach to a broad array of saturated oxygen- and nitrogen-containing heterocycles. The products are usually obtained with excellent diastereoselectivity and in good chemical yield. These reactions provide access to many compounds that would be difficult to prepare with previously existing methods, and also allow for the conversion of a single alcohol or amine starting material into an array of different products.

In addition to the synthetic utility of these transformations, mechanistic studies have provided new insight into alkene syn-heteropalladation reactions, which were uncommon transformations prior to the start of this work.14 A number of groups are now investigating various aspects of these processes,15 and it is likely that new catalytic transformations will arise from these collective studies.

Although considerable progress has been made in this area, a number of interesting and important problems remain unsolved. Development of new catalysts or conditions that effect transformations of very sterically hindered and/or highly substituted substrates would be of great utility. There are also many opportunities for the development of cascade processes and catalytic asymmetric versions of these reactions. In addition, there is great potential for the application of these methods to the synthesis of biologically active targets, and the extension of this chemistry to the synthesis of a number of other useful heterocycles.

Acknowledgment

We thank the NIH-NIGMS (GM 071650), the Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation, Research Corporation, 3M, Amgen, Eli Lilly, and GlaxoSmithKline for their generous support of the research described in this account.

Biography

John P. Wolfe was born in Greeley, CO, and received his B.A. degree from the University of Colorado, Boulder in 1994. As an undergraduate he conducted research in the labs of Professor Gary A. Molander. He received his Ph.D. degree in 1999 from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology under the guidance of Professor Stephen L. Buchwald. Following the completion of his Ph.D. studies, he spent three years as an NIH postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Professor Larry E. Overman at the University of California, Irvine. He joined the faculty at the University of Michigan in July, 2002, where he is currently an Associate Professor of Chemistry.

Professor Wolfe’s current research is directed towards the development of new palladium-catalyzed reactions for the stereoselective synthesis of heterocycles, and studies of alkene insertion processes of late transition metal alkoxide and amido complexes. Other research interests include the development of new tandem reactions, and the total synthesis of biologically active natural products. His research accomplishments have been recognized with several awards, including the Dreyfus New Faculty Award (2002), the Research Corporation Innovation Award (2002), the 3M Untenured Faculty Award (2003-2005), the Amgen Young Investigator Award (2004), the Lilly Grantee Award (2005), the Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Award (2006), and the GlaxoSmithKline Scholar Award (2008-2009).

References

- (1).For reviews on biologically active tetrahydrofurans and pyrrolidines, see:Kang EJ, Lee E. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:4348. doi: 10.1021/cr040629a.Saleem M, Kim HJ, Ali MS, Lee YS. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2005:696. doi: 10.1039/b514045p.Bermejo A, Figadere B, Zafra-Polo M-C, Barrachina I, Estornell E, Cortes D. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2005:269. doi: 10.1039/b500186m.Daly JW, Spande TF, Garraffo HM. J. Nat. Prod. 2005;68:1556. doi: 10.1021/np0580560.Hackling AE, Stark H. Chem. BioChem. 2002;3:946. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20021004)3:10<946::AID-CBIC946>3.0.CO;2-5.Lewis JR. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2001;18:95. doi: 10.1039/a909077k.

- (2).For select recent reviews on metal-catalyzed or -mediated reactions for the synthesis of heterocycles, see:D’Souza DM, Mueller TJJ. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1095. doi: 10.1039/b608235c.Chemler SR, Fuller PH. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1153. doi: 10.1039/b607819m.Minatti A, Muniz K. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1142. doi: 10.1039/b607474j.Zeni G, Larock RC. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:4644. doi: 10.1021/cr0683966.Conreaux D, Bouyssi D, Monteiro N, Balme G. Curr. Org. Chem. 2006;10:1325.Muzart J. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:5955.Wolfe JP, Thomas JS. Curr. Org. Chem. 2005;9:625.Nakamura I, Yamamoto Y. Chem Rev. 2004;104:2127. doi: 10.1021/cr020095i.Zeni G, Larock RC. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:2285. doi: 10.1021/cr020085h.Deiters A, Martin SF. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:2199. doi: 10.1021/cr0200872.Barluenga J, Santamaria J, Tomas M. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:2259. doi: 10.1021/cr0306079.McReynolds MD, Dougherty JM, Hanson PR. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:2239. doi: 10.1021/cr020109k.

- (3).For reviews on the synthesis of tetrahydrofurans, see:Wolfe JP, Hay MB. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:261. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2006.08.105.Miura K, Hosomi A. Synlett. 2003:143.Koert U. Synthesis. 1995:115.Harmange J-C, Figadere B. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1993;4:1711.Cardillo G, Orena M. Tetrahedron. 1990;46:3321.Boivin TLB. Tetrahedron. 1987;43:3309.

- (4).For reviews on the synthesis of pyrrolidines, see:Bellina F, Rossi R. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:7213.Coldham I, Hufton R. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2765. doi: 10.1021/cr040004c.Pyne SG, Davis AS, Gates NJ, Hartley JP, Lindsay KB, Machan T, Tang M. Synlett. 2004:2670.Felpin F-X, Lebreton J. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003:3693.

- (5).For related transformations of γ-hydroxy or γ-amino allenes or alkynes see:Balme G, Bouyssi D, Lomberget T, Monteiro N. Synthesis. 2003:2115.Kang S-K, Baik T-G, Kulak AN. Synlett. 1999:324.Jacobi PA, Liu H. Org. Lett. 1999;1:341. doi: 10.1021/ol990684j.Walkup RD, Guan L, Mosher MD, Kim SW, Kim YS. Synlett. 1993:88.Luo FT, Schreuder I, Wang RT. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:2213.Luo FT, Wang RT. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:6835.Arcadi A, Cacchi S, Marinelli F. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:3915.Davies IW, Scopes DIC, Gallagher T. Synlett. 1993:85.Wolf LB, Tjen KCMF, Rutjes FPJT, Hiemstra H, Schoemaker HE. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:5081.

- (6).Other metal-catalyzed or metal-mediated reactions of γ-hydroxy or γ-amino alkenes that generate heterocycles with formation of both a carbon-heteroatom bond and a carbon-carbon bond have also been reported. For examples of Cucatalyzed intramolecular carboamination of N-(arylsulfonyl)-2-allylanilines and related derivatives, see:Sherman ES, Fuller PH, Kasi D, Chemler SR. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:3896. doi: 10.1021/jo070321u.Sherman ES, Chemler SR, Tan TB, Gerlits O. Org. Lett. 2004;6:1573. doi: 10.1021/ol049702+.For Pd(II)-catalyzed alkoxycarbonylation of alkenes bearing tethered nitrogen nucleophiles, see:Harayama H, Abe A, Sakado T, Kimura M, Fugami K, Tanaka S, Tamaru Y. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:2113. doi: 10.1021/jo961988b.For carboamination reactions between alkenes and N-allylsulfonamides, see:Scarborough CC, Stahl SS. Org. Lett. 2006;8:3251. doi: 10.1021/ol061057e.For carboamination of vinylcyclopropanes, see:Larock RC, Yum EK. Synlett. 1990:529.For Pd(II)-catalyzed alkoxycarbonylation of alkenes bearing tethered oxygen nucleophiles, see:Semmelhack MF, Bodurow C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:1496.Semmelhack MF, Zhang N. J. Org. Chem. 1989;54:4483.McCormick M, Monahan R, III, Soria J, Goldsmith D, Liotta D. J. Org. Chem. 1989;54:4485.Semmelhack MF, Kim C, Zhang N, Bodurow C, Sanner M, Dobler W, Meier M. Pure Appl. Chem. 1990;62:2035.and references cited therein.

- (7).For Pd-catalyzed reactions of β-amino alkenes with alkenyl halides that afford pyrrolidine products via formal 1,1-addition to the alkene, see:Harris GD, Jr., Herr RJ, Weinreb SM. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:2528.Harris GD, Jr., Herr RJ, Weinreb SM. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:5452.Larock RC, Yang H, Weinreb SM, Herr RJ. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:4172.

- (8).For a review on Pd(0)- and Pd(II)-catalyzed carboetherification and carboamination reactions, see:Wolfe JP. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007:571.

- (9).Crabtree RH. The Organometallic Chemistry of the Transition Metals. 4nd ed. John Wiley and Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2005. [Google Scholar]