Abstract

The purpose of this project was to compare individual state regulations regarding menus for child-care centers and family child-care homes with national menu standards. For all 50 states and the District of Columbia, state regulations were compared with menu standards found in Caring for Our Children—National Health and Safety Performance Standards: Guidelines for Out-of-Home Child Care Programs. Specifically, these guidelines suggest that (a) menus must be posted or made available to parents, (b) menus must be dated, (c) menus must reflect food served, (d) menus must be planned in advance, and (e) menus must be kept on file. One additional standard, that menus in child care are reviewed by a nutrition professional, was added to this review. Data were collected between June and August of 2007. Substantial variation existed among state regulations regarding menus. For child-care centers, seven states (14%) included regulations on all five standards, and 13 states (25%) had regulations on four of the five menu standards. Ten states (20%) did not have any regulations on the five menu standards. For family child-care homes, only three states (6%) had regulations on all five menu standards; four states (8%) had regulations on four of the five menu standards. Twenty-seven states (53%) did not have any regulations on the five standards for menus. Within the same state, regulations for child-care centers and family child-care homes often did not match. Overall, great discrepancies were found between model child-care menu policies and current state regulations in most states. States have the opportunity to improve regulations regarding menus to ensure that child-care providers develop accurate, specific, and healthful menus.

In the United States, a substantial number of young children are in child care. Seventy-four percent of pre-school-aged children are in some form of nonparental care and 56% are in center-based child care (1). The amount of time children spend in child care each week has increased in recent years (2), and as a result children in child care may consume a large proportion of their daily energy intake at child-care facilities (3,4). Child-care providers are responsible for providing nutritionally adequate, healthful food to children, but may receive little guidance in this area.

Caring for Our Children—National Health and Safety Performance Standards: Guidelines for Out-of-Home Child Care Programs (CFOC), a collaborative effort from the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Public Health Association, and the US Department of Health and Human Services, provides standards related to injury and disease prevention and health promotion for children in child-care facilities (5). This resource includes menu standards for child-care facilities that are based on the best available evidence for planning healthful menus. Adhering to these standards is voluntary; child-care facilities are not required by law to meet these standards.

Child-care facilities are, however, required to comply with their state regulations. In each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia, child-care facilities are licensed and governed by a state agency responsible for enforcement of state regulations (6). Regulations regarding menus in child care vary substantially by state, and no comprehensive review has examined these regulations related to menus for child-care facilities. The purpose of this study was to compare individual state regulations regarding menus for child-care centers and family child-care homes with national standards put forth in CFOC. It was hypothesized that less than half of all states would have regulations in line with CFOC standards and that few states would have a regulation on the additional standard: menu review by a nutrition professional.

METHODS

Subjects

For this cross-sectional study, data were collected on individual state regulations for child-care centers and family child-care homes from the Web site for the National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care (7). This agency maintains a public access database of current state child-care regulations for all US states and the District of Columbia.

Selection of Key Items

One researcher (S.E.B.) reviewed individual state regulations regarding menus for child-care facilities and compared these with CFOC standards. Specifically, CFOC guidelines suggest that (a) menus must be posted or made available to parents; (b) menus must be dated; (c) menus must reflect food served; (d) menus must be planned in advance; and (e) menus must be kept on file. One additional standard was included in this regulations review. A separate post hoc review was conducted to assess the number of states that required that a nutrition professional review child-care menus. Although this was not a CFOC standard, menu review by a nutrition professional has the potential to substantially improve nutritional quality of foods served in child-care facilities. Given the vast number of children in child care and the minimum nutrition standards set by state agencies for foods served in child-care facilities, menu review by a nutrition professional is of critical importance and therefore was included as a standard in this review.

Review of Regulations

Regulations were reviewed for child-care centers and family child-care homes for all 50 US states and the District of Columbia (referred to in this paper as states) between June and August of 2007. One researcher read each state's regulations in their entirety and recorded regulations consistent with each of the CFOC standards and whether menu review by a nutrition professional was included in the state regulations. Regulations were considered consistent with CFOC standards if the wording was clear and specific and matched unequivocally the concept of each CFOC standard. For example, Delaware child-care center regulations state that, “A licensee shall ensure that menus are planned in advance, are dated and are posted in a prominent place. Menus noting actual food served shall be retained by the Center for thirty (30) days. Any changes made in actual food served on a particular date shall be documented on the menu on or before that date” (7). This state's regulations were consistent with all five CFOC menu standards.

Most states license two main classes of child-care facilities: child-care centers and family child-care homes. Child-care centers generally care for more children and typically have more staff members than family child-care homes. Family child-care homes are located in the residence of the owner and operator of the facility, who is often the only provider of care. States have varying definitions for the maximum number of children allowed to receive care in a family child-care home, but most limit enrollment to six or fewer children. As a result of these differences, states license each of these types of child-care facilities individually, with a unique set of regulations for each.

Nine states have only one regulation that governs both child-care centers and family child-care homes, 16 states have a separate regulation for centers and for family child-care homes, and 26 states have regulations for more than two distinct classes of facilities. Additional facility types were grouped into one of the two main classes (child-care centers or family child-care homes). For example, Hawaii issues a license for four types of facilities, which were grouped into two types as follows: group child-care centers and infant and toddler child-care centers were classified as child-care centers, and family child-care homes and group child-care homes were classified as family child-care homes. Delaware, by contrast, regulates child-care centers, large family child-care homes, and family child-care homes. In this case, the latter two types of facilities were classified as family child-care homes for this review.

Analysis

Frequencies were computed for the total number of regulations for each state for child-care centers and family child-care homes. The additional regulation (review of menus by a nutrition professional) was not included in the analysis because this regulation was not a CFOC standard. State regulations were examined by US census track regions, which included Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont in the Northeast; Arkansas, Alabama, District of Columbia, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia in the South; Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, North Dakota, Nebraska, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin in the Midwest; and Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming in the West. Mean number of regulations were computed for states in each census track region.

States reported the date of their most recent regulations update for centers (Figure 1) and family child-care homes (Figure 2). Further analyses examined the relationship between date of last update and total number of regulations reflecting CFOC standards. Spearman correlation coefficients were computed to examine the relationship between year of last update, treated as a continuous variable, and number of regulations in each state. For this analysis, a value of 0 to 22 was assigned, representing the range of years (1985−2007) when states made their last update. Next, year of last update was dichotomized into either “updated within the past 5 years” or “updated more than 5 years ago.” Mantel-Haenszel trend tests were used to explore associations between the dichotomized year variable and number of regulations in each state. Mantel-Haenszel trend tests were also used to assess correlations between geographic region (Northeast, South, Midwest, and West) and number of regulations in each state. Tests of association were conducted at an α=.05 significance level, and all analyses were done using SAS (version 9.1, 2004, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

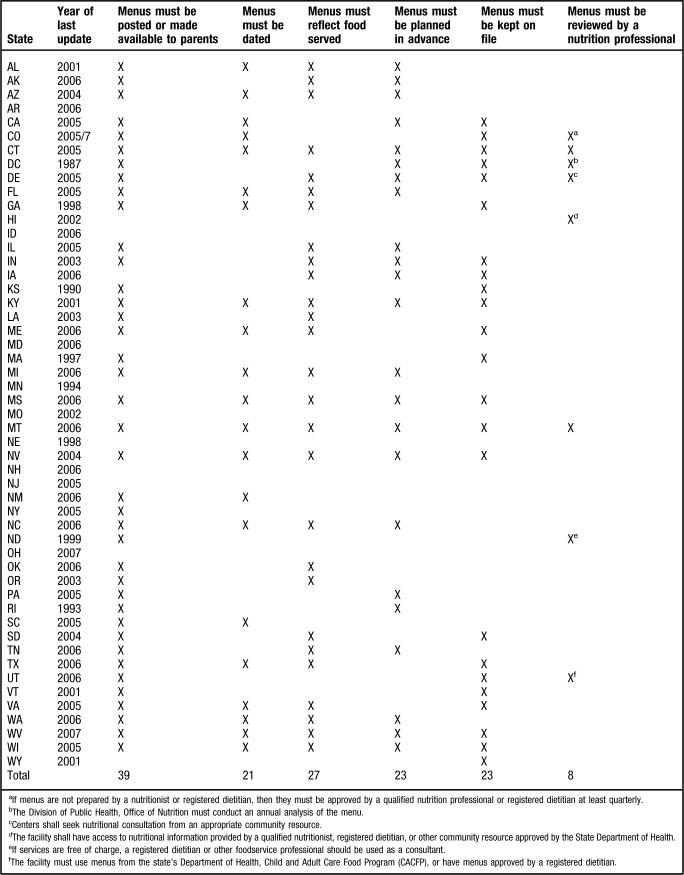

Figure 1.

State regulations regarding menus for child-care centers, 2007.

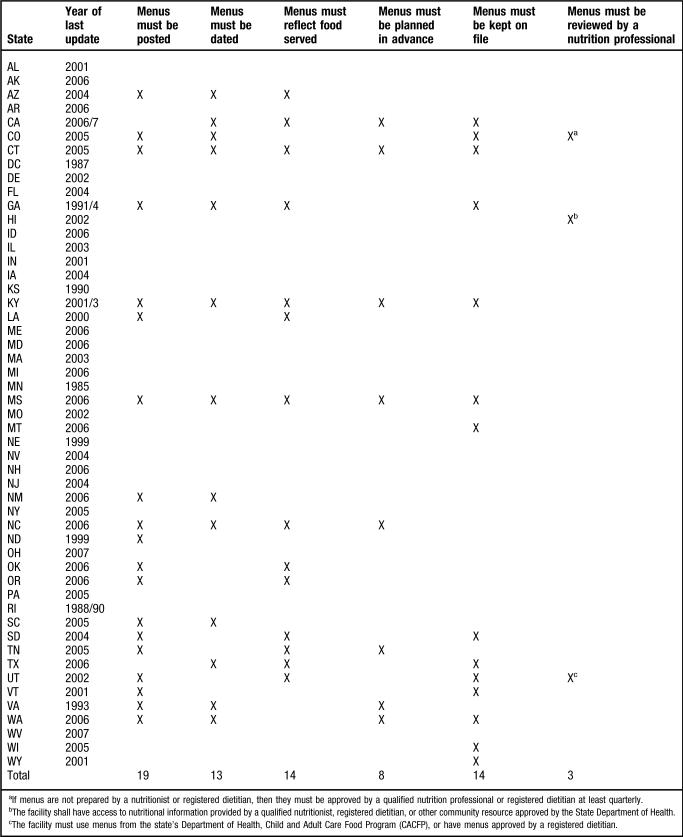

Figure 2.

State regulations regarding menus for family child-care homes, 2007.

RESULTS

Overview

States varied in their regulations regarding menus for both child-care centers (Figure 1) and family child-care homes (Figure 2). For centers, Connecticut, Kentucky, Mississippi, Montana, New York, West Virginia, and Wisconsin (14%) had regulations on all five of the menu standards, whereas Arkansas, Hawaii, Idaho, Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, and Ohio (20%) did not have any regulations on the five menu standards. For family child-care homes, only Connecticut, Kentucky, and Mississippi (6%) had regulations on all of the five menu standards. Twenty-seven states (Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, District of Columbia, Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and West Virginia) (53%) did not have any regulations on the five standards for menus for family child-care homes.

The number of regulations varied by US census region. States in the South had the greatest mean number of regulations for centers (3.24) and family child-care homes (1.94), compared with the Northeast, which had the smallest mean number of regulations for centers (2.00) and the Midwest, which had the lowest mean for family child-care homes (0.42).

Thirty-four states (67%) for centers and 31 states (61%) for family child-care homes had updated their regulations within the past 5 years. Conversely, regulations had not been updated in the past 10 years in seven states (14%) for centers, and in six states (12%) for family child-care homes. No associations were found between year of last update and number of regulations for either centers (Spearman's ρ=0.15, P=0.31) or family child-care homes (Spearman's ρ=0.09, P=0.52). No associations were found between year of last update, dichotomized into “updated in the last 5 years” compared with “updated greater than 5 years ago,” and number of regulations for centers (P=0.07) and number of regulations for family child-care homes (P=0.33). No associations between geographic region and number of state regulations were found for centers. An association between geographic location and number of regulations in each state for family child-care homes was observed. In particular, states in the South and the West had more regulations for family child-care homes than states in the Northeast and the Midwest (P=0.05).

CFOC Menu Standards

Menus Must Be Posted or Made Available to Parents

Ensuring that menus were posted or made available to parents was the most common regulation. Thirty-nine states (76%) had regulations to ensure that menus were either posted or made available to parents of children in child-care centers. Nineteen states (37%) required family child-care homes to either post their menus or make them available to parents.

Menus Must Be Dated

Twenty-one states (41%) required child-care centers to date their menus, and 13 states (25%) required family child-care homes to do so.

Menus Must Reflect Food Served

For child-care centers, 27 states (53%) required menus to reflect the actual foods served in the facility. For family child-care homes, 14 states (27%) required menus to reflect what was served by the child-care provider. Often, states specified that child-care providers must note any substitutions or deviations from the menu in advance of the meal or snack.

Menus Must Be Planned in Advance

Twenty-three states (45%) required child-care centers to plan their menus in advance, and eight states (16%) required this of family child-care homes. No specific timeframe or definition for in advance was included in any state regulation.

Menus Must Be Kept on File

Twenty-three states (45%) required child-care centers to keep copies of their menus on file in the facility, ranging from 1 week (Virginia) to 12 months (Mississippi and Montana). For family child-care homes, 14 states (27%) required menus be kept on file, ranging from 1 week (Utah) to 12 months (Mississippi). Three states (6%) required menus be kept on file but did not provide a specific duration (Iowa and Massachusetts for centers only, and Wyoming for centers and family child-care homes).

Additional Standard Added to this Review

Menus Must Be Reviewed by a Nutrition Professional

Eight states (16%) required child-care centers to have their menus reviewed by a nutrition professional. For family child-care homes, three states (6%) required menus to be reviewed by a nutrition professional. Specifically, centers in Connecticut were required to seek advice from a registered dietitian concerning nutrition and foodservice. In Colorado, if menus were not prepared by a nutrition professional, then menus needed to be approved by a qualified nutritionist or registered dietitian at least quarterly, for both centers and family child-care homes. In the District of Columbia, centers were required to have menus reviewed and analyzed annually by the Division of Public Health, Office of Nutrition. Hawaii required centers and family child-care homes to access nutrition information from a qualified nutritionist or dietitian, whereas in North Dakota this was only required of centers if these nutrition services were free. Utah required both centers and family child-care homes to use Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) (8) sample menus, or have their menus approved by a registered dietitian.

DISCUSSION

In this review, state regulations for child-care facilities varied widely regarding menus. For child-care centers, 10 states (20%) did not have any regulations related to the five menu standards, 13 states (25%) had regulations for four of the five menu standards, and only seven states (14%) included all five standards. For family child-care homes, 27 states (53%) did not have any regulations for the five standards for menus, four states (8%) had regulations for four of the five menu standards, and only three states (6%) had regulations for all five menu standards. Thus, great discrepancies were found between model child-care menu policies from CFOC and current regulations in most states.

Menus are a source of information for parents, regulators, and researchers. Accurate, specific menus can communicate nutrition information to parents and facilitate discussions about nutrition among child-care providers, parents, and children. Unless parents supply food for their preschool-aged children, the menu provided by the child-care facility often serves as the main way parents know what their children are eating at child care. Several researchers have also used menus to assess dietary in-take of children in child care (9,10), or to identify opportunities for nutrition intervention (9,11-14). There is some evidence, however, that menus rarely matched foods served to children (15).

State and federal regulators also rely on menus as a proxy for actual food served in child care because menu review is often the most cost-effective method to monitor and assess foods served in child care. CACFP is a federal entitlement program that provides nutrition education and reimbursement for meals and snacks to eligible child-care facilities (8). This program governs meal patterns and portion sizes, sets some minimal nutrition standards, and offers sample menus to help child-care providers develop comprehensive, accurate menus. Centers that participate in CACFP, which include all Head Start Program (16) centers, must provide copies of menus to ensure compliance with CACFP program requirements. Participants are required to date their menus and to ensure that menus reflect actual foods served. Therefore, in states without regulations reflecting these two CFOC standards, child-care facilities participating in CACFP should be engaging in these practices. In some cases, state regulations defer to CACFP guidelines for participating facilities. Utah, for example, requires their child-care facilities to either use menus provided by CACFP or use other menus approved by a registered dietitian. Given that not all child-care providers qualify for CACFP or choose to participate in it, the most comprehensive way to ensure that menus meet CFOC standards is to include those standards in state regulations.

There are several limitations to this review. First, this review may already be outdated if states have recently revised their regulations. A second limitation is that cities or other geographic areas within a state have the power to regulate child-care facilities in their jurisdiction. New York City, for example, recently enacted nutrition and physical activity regulations that were more stringent than those for the state of New York. A review of state regulations, therefore, may not capture all regulations governing child-care facilities in the United States. In addition, states often license more than two types of child-care facilities. For the purposes of this study, facilities were grouped as either a child-care center or a family child-care home. Various groupings of facilities may yield results that are different from those found in this review.

This review addresses regulations, not actual practice. The existence of a regulation does not necessarily ensure that child-care facilities are operating in accordance with the regulation. To assess compliance with regulations, state regulatory agency representatives visit child-care facilities in their state to ensure that child-care providers are adhering to state regulations. Twenty-nine states visit centers for routine inspections at least once per year, 16 visit every 2 years, and six visit every 3 or more years. For family child-care homes, states assess compliance less frequently (range: every 6 months to 10 years). Some states do not require routine inspections of family child-care homes unless a formal complaint has been filed. It seems likely that states who visit child-care facilities more often will have better adherence to their regulations, although no data are available. Additional or more stringent regulations may not be effective unless states have the capacity to enforce them. Child-care providers, however, are typically a compliant group because their livelihood and the health of the children depend on their adherence to regulations.

CONCLUSIONS

Several nutrition- and physical activity–related regulations for child-care facilities are worth examining; this review focused on regulations regarding menus. In this study, state regulations about menus for child-care facilities were compared with menu standards found in CFOC. Few states had regulations that met all five CFOC menu standards. Our results have several implications for nutrition professionals. First, nutrition professionals providing consultation to child-care facilities must be familiar with their state's regulations regarding menus.

A unique opportunity exists in states requiring menu review from a nutrition professional. Eight states require that a nutrition professional review the menus that child-care centers provide, even though this is not a CFOC standard. In those states, nutrition professionals may have great influence over foods and beverages served in child-care facilities, and consequently children's nutrient intake. Nutrition professionals are in a position to not only improve the quality of the foods on the menu, but also the quality of the menus themselves, by helping ensure that menus meet CFOC standards. Improved menu quality ensures that parents, regulators, and researchers receive accurate, specific menus.

Nutrition professionals also have the opportunity to encourage their states to adopt menu regulations that reflect standards in CFOC. States currently in the process of revising their regulations may wish to enhance their menu regulations, and nutrition professionals can be poised to help make those improvements. In this analysis, no relationship was found between number of regulations meeting CFOC menu standards and year of last update. States that recently updated their regulations were not necessarily adhering to national recommendations and including CFOC menu standards in their revision. More involvement from nutrition professionals may encourage states to adopt CFOC standards and enhance their regulations regarding menus. In this way, nutrition professionals can advocate for state policy change. When new regulations are proposed by states, there is often a public hearing period, when parents and health professionals can voice opinions on the proposed regulations. Nutrition professionals have the opportunity to participate in these hearings and advocate for regulations that promote healthful behaviors and environments in child-care settings. In particular, encouraging states to require menu review by a nutrition professional will help advance the field of nutrition and ensure nutritious meals and snacks are provided to children in child care. Nutrition professionals could include parents as key collaborators when advocating to regulatory agencies for enhanced regulations as well as additional enforcement of current regulations. State regulatory agencies typically respond well to recommendations and suggestions from parents.

Additional research in this area is needed. Future studies could explore the possible relationships between meeting standards included in this review and the nutritional quality of foods served in child-care facilities. Researchers could also assess the relationship between frequency of compliance checks by regulatory agencies and child-care facility adherence to state regulations. Of greatest importance, however, is the effect of regulation on the health of the children in child care. Future studies should examine the impact of menu regulations on health outcomes in children.

Acknowledgments

The authors did not receive any financial support for this research.

References

- 1.Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics . America's Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being, 2002. US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sturm R. Childhood obesity—What we can learn from existing data on societal trends, part 2. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2:A20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruening KSGJ, Passannante MR, McClowry S. Dietary intake and health outcomes among young children attending 2 urban day-care centers. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;12:1529–1535. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00375-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Padget A, Briley ME. Dietary intakes at child-care centers in central Texas fail to meet Food Guide Pyramid recommendations. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:790–793. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Academy of Pediatrics, American Public Health Association, National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care . Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: 2002. Chapter 4: Nutrition and Food Service. pp. 149–186. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Child Care . State Efforts to Enforce Safety and Health Requirements. US General Accounting Office GAO/HEHS-00−28; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care in Early Education Web site [June 3, 2007]; http://nrc.uchsc.edu.

- 8.US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. Child and Adult Care Food Program. USDA, Food and Nutrition Service Web site [June 21, 2007]; http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/Care.

- 9.Matwiejczyk L, McWhinnie JA, Colmer K. An evaluation of a nutrition intervention at childcare centres in South Australia. Health Promot J Austr. 2007;18:159–162. doi: 10.1071/he07159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oakley CB, Bomba AK, Knight KB, Byrd SH. Evaluation of menus planned in Mississippi child-care centers participating in the Child and Adult Care Food Program. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995;95:765–768. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(95)00213-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams CL, Bollella MC, Strobino BA, Spark A, Nicklas TA, Tolosi LB, Pittman BP. “Healthy-start”: Outcome of an intervention to promote a heart healthy diet in preschool children. J Am Coll Nutr. 2002;21:62–71. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2002.10719195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Briley ME, Buller AC, Roberts-Gray CR, Sparkman A. What is on the menu at the child care center? J Am Diet Assoc. 1989;89:771–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pollard CM, Lewis JM, Miller MR. Food service in long day care centres—An opportunity for public health intervention. Aust N Z J Public Health. 1999;23:606–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.1999.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romaine N, Mann L, Kienapple K, Conrad B. Menu planning for childcare centres: Practices and needs. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2007;68:7–13. doi: 10.3148/68.1.2007.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleischhacker S, Cason KL, Achterberg C. “You had peas today?”: A pilot study comparing a Head Start child-care center's menu with the actual food served. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:277–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Head Start Bureau. Head Start Performance Standards and Other Regulations. USDHHS, Administration for Children and Families Web site [June 21, 2007]; http://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/hslc.