Abstract

This study was designed to describe the conflict resolution practices used in Mexican American adolescents' friendships, to explore the role of cultural orientations and values and gender-typed personality qualities in conflict resolution use, and to assess the connections between conflict resolution and friendship quality. Participants were 246 Mexican American adolescents (M = 12.77 years of age) and their older siblings (M = 15.70 years of age). Results indicated that adolescents used solution-oriented strategies most frequently, followed by nonconfrontation and control strategies. Girls were more likely than boys to use solution-oriented strategies and less likely to use control strategies. Familistic values and gender-typed personality qualities were associated with solution-oriented conflict resolution strategies. Finally, conflict resolution strategies were related to overall friendship quality: solution-oriented strategies were positively linked to intimacy and negatively associated with friendship negativity, whereas nonconfrontation and control strategies were associated with greater relationship negativity.

Keywords: Mexican American youth, Friendships, Conflict resolution, Gender

Introduction

Adolescents' friendships offer important opportunities for social development in part because of the behaviors adolescents learn while engaging in conflict episodes with their friends (Youniss and Smollar 1985). The conflict resolution strategies learned in adolescents' peer relationships are associated with both short-term and long-term relationship success. Research has shown that conflict resolution skills are linked to the maintenance of friendships in adolescence (Hartup 1993), to marital satisfaction (Gottman and Krokoff 1989), and to workplace success (Tjosvold 1998). In fact, some scholars have argued that conflict resolution skills are among the most important determinants of friendship quality (Crohan 1992; Laursen and Collins 1994). Although research suggests that conflict management is crucial to the maintenance of interpersonal relationships (Hartup 1993; Laursen and Collins 1994; Jensen-Campbell et al. 1996), very little is known about the conflict resolution strategies practiced in ethnic minority adolescents' friendships. Addressing a gap in the literature on normative development among ethnic minority youth (Hagen et al. 2004; McLoyd 1998), this study examined the nature and correlates of conflict resolution processes in Mexican American adolescents' friendships.

Dual Concern Model of Conflict Resolution

The literature on conflict resolution encompasses multiple typologies of resolution strategies. The most widely used categories, however, are based on the Dual Concern model (Pruitt 1982; Pruitt and Carnevale 1993). According to the premises of this model, the resolution strategy that a person uses is dependent upon the level of concerns for oneself versus others in a conflict. Collaboration (e.g., negotiation and compromise), generally the most adaptive form of resolution, occurs when there is high concern for both oneself and others. A second strategy, accommodation, occurs when individuals have high concern for others and low concern for oneself; individuals with this style tend to be taken advantage of in conflict situations. Although collaboration and accommodation were initially identified as separate dimensions in the Dual Concern model, recently they have been clustered together into one category generally labeled solution-orientation, negotiation or cooperation (e.g., Laursen 1993; Laursen et al. 2001). Controlling resolution strategies (e.g., competition, negativity, and antagonism), in contrast, are thought to reflect a high degree of concern for oneself and a low degree of concern for others. Finally, nonconfrontational strategies, including avoidant and withdrawing behaviors, are attributed to low concern for both oneself and others. For the present study, it is particularly relevant to note that, although the Dual Concern model suggests that nonconfrontation strategies represent low concern for both oneself and others, in collectivistic cultural contexts this may be an adaptive form of resolution for preserving relational harmony. Grounded in the more recent three-dimensional model (Laursen et al. 2001), the present study investigates three strategies for resolving conflicts in Mexican American adolescents' friendships: solution-orientation, nonconfrontation, and control.

The Role of Culture in Conflict Resolution

The nature of dyadic friendship processes in general and conflict resolution skills in these relationships have received scant attention in cross-cultural research on social development (Way 2006). A handful of studies suggest that conflict resolution preferences may be related to the level of individualism versus collectivism of the culture (e.g., Gabrielidis et al. 1997; Trubisky et al. 1991). Along these lines, Hofstede (1980) suggested that societies like the United States encourage values of individual achievement and personal freedom, whereas collectivist cultures like Mexico value group success and harmony. Gabrielidis et al. (1997) found that Mexican undergraduates preferred solution-oriented over control techniques, whereas Anglo American undergraduates preferred control resolutions. An important next step is to move beyond cross-cultural comparisons to explore within-group variability in conflict resolution strategies in particular ethnic minority groups.

We draw on a bi-dimensional model of cultural adaptation in examining the links between adolescents' cultural orientations and familism values, values considered to be particularly important in Mexican culture (e.g., Cauce and Domenech-Rodríguez 2002; Marín and Marín 1991), and their conflict resolution practices. According to this model, two independent and concurrent processes need to be considered: acculturation, or the process of adopting values and beliefs and being involved in the host culture, and enculturation, or involvement in and acceptance of beliefs, values, and practices related to the culture of origin (Berry 2003; Cabassa 2003; Phinney 1990). Using this framework, we examined connections between adolescents' conflict resolution strategies and both their cultural orientations and their familism values.

Researchers have suggested that the Mexican value of simpático, and its emphasis on harmonious interpersonal relations that maintain group accord (Delgado-Gaitan 1993; Triandis et al. 1984), is particularly relevant for the study of conflict management. Familistic values also emphasize group harmony within the nuclear and extended family (Marín and Marín 1991). We expected that adolescents who identified with Mexican culture and subscribed to familistic values would be more likely to avoid conflict or accommodate to others in conflict situations. Anglo orientation is often linked to conflict goals of self-interest and personal needs (Tinsley 2001). One might expect, then, that adolescents' identification with Anglo culture would be associated with the use of controlling strategies to resolve conflict.

Although some theoretical connections between culture and conflict resolution have been proposed, empirical evidence is limited. This study examines the conflict resolution behaviors used in Mexican American adolescents' friendships. We began by describing the conflict resolution strategies used in Mexican American adolescents' friendships and then explored the links between adolescents' cultural orientations and familistic values and their conflict management strategies. We hypothesized that adolescents would use solution-oriented strategies most frequently and that Mexican cultural orientation and familistic values would be positively related to nonconfrontational and solution-oriented resolution practices whereas Anglo cultural orientation would be related to more controlling resolutions in adolescents' friendships.

The Role of Gender in Conflict Resolution

Our second goal was to examine the role of gender in Mexican American adolescents' conflict resolution practices. In prior studies, researchers have found gender differences in communication that may be related to conflict resolution. For instance, Maccoby (1990, 1998) suggested that, by practicing social skills within primarily same-sex peer groups, the two sexes form distinctive patterns that carry over into adolescent and adult relationships. According to Maccoby's (1990, 1998) gender socialization perspective, females are more likely to use supportive interactive styles because of their extensive exposure to these strategies in their interactions with other females, and males are more likely to use restrictive and controlling interactive styles that work well in larger playgroups (Maccoby 1990, 1998). These different styles may translate to different strategies for resolving conflicts.

Gender differences have received scant attention in the current literature on adolescent conflict resolution. Some research with young children suggests that boys and girls do use different resolution strategies (e.g., Dunn and Herrera 1997), yet other studies find no such difference (Iskandar et al. 1995). Our previous research focusing on European American adolescents' close friendships in early adolescence supports Maccoby's (1990, 1998) ideas finding that girls are more likely than boys to use solution-oriented conflict resolution strategies, whereas boys are more likely than girls to compete in their disagreements (Bahr et al. 2002).

The role of gender and gender-typed personality qualities is particularly important to consider for Mexican American youth. Although early portrayals of Mexican American families as ascribing to rigidly traditional gender roles are no longer believed to be accurate (Baca-Zinn 1994; Williams 1990), gender is thought to be an organizing feature of family life in Mexican culture (Cauce and Dominech-Rodríguez 2002). In accordance with Maccoby's (1990, 1998) perspective and existing work on gender norms in Mexican culture, we hypothesized that girls would use more solution-oriented strategies and boys would use more nonconfrontational and controlling strategies.

We also assessed the connections between gender-linked personality traits and conflict resolution. Gender researchers have studied expressivity and instrumentality as stereotypically feminine and masculine personality qualities (Boldizar 1991). Expressive personality traits include being affectionate, sympathetic, and sensitive to the needs of others whereas instrumental traits include independence, assertiveness, and dominance (Bem 1974). To our knowledge, only one other study has explored the connections between expressive and instrumental personality qualities and conflict resolution. Tucker et al. (2003) examined the links between expressivity, instrumentality, and constructive conflict management with a sample of European American adolescents. Their results indicated that expressive traits were linked to the greater use of constructive resolution strategies with parents. By focusing on friendships rather than parent-child relationships, the present study extends the work by Tucker et al. (2003). We predicted that expressive traits would be linked to solution-oriented resolution strategies whereas instrumental traits would be linked to control.

Exploring the Links Between Conflict Resolution Strategies and Friendship Quality

Developmental perspectives underscore the significant role of friendships and peer relationships in adolescents' daily lives (Hartup 1993). Girls and boys from many different ethnic backgrounds highlight the importance of their relationships with other youth during the adolescent years (e.g., Azmitia et al. 2006; Way 2006). Adolescent friendships have been described as encompassing both positive (i.e., intimacy, closeness, emotional support) and negative (e.g., conflict, negativity, distrust) relationship dimensions (Furman and Buhrmester 1985; Way 2006). The development of intimacy in friendships has been described as a process that increases notably during adolescence, with children having more intimate knowledge of their friends as they transition from middle childhood to adolescence (Berndt 1982), and references to intimacy in friendships being described most frequently during mid- to late-adolescence (Bigelow and LaGaipa 1980). Studies of ethnic minority youth also highlight emotional support and intimacy as important dimensions of adolescents' friendships in diverse cultures in the U.S. (Azmitia et al. 2006; Way 2006). Negativity remains a salient component of adolescents' social relationships as well. Laursen (1996) found that adolescents report an average of seven disagreements per day. Although most of those conflicts are with their mothers, adolescents also experience significant conflict in their friendships (Furman and Buhrmester 1992; Laursen 1996). Studies of youth from other cultural backgrounds suggest that negativity is not exclusive to European American friendships (e.g., French et al. 2006).

The final goal of this study was to explore the role of conflict resolution in friendship quality. Conflict resolution has been considered by many researchers to be the most important determinant of overall relationship quality (Laursen and Collins 1994) and longevity (Hartup 1993). Furthermore, conflict resolution is particularly crucial to the maintenance of adolescents' friendships (Hartup 1993; Laursen and Collins 1994; Jensen-Campbell et al. 1996), a source of emotional support for teenagers from diverse ethnic backgrounds (Azmitia et al. 2006; Way 2006). Our predictions about the associations between conflict resolution and friendship quality were grounded in cultural and developmental perspectives. Because Mexican culture emphasizes harmony in interpersonal relationships (Delgado-Gaitan 1993; Triandis et al. 1984), we anticipated that solution-oriented strategies (i.e., efforts to come to mutually satisfying conflict resolutions) would be related to higher intimacy and lower negativity. We predicted that controlling strategies, which emphasize a preservation of individual rather than collective interests and goals, would be related to lower friendship intimacy and higher negativity in Mexican American adolescents' friendships. Finally, in considering nonconfrontation strategies, one possibility is that values of interpersonal harmony and collectivism may mean that avoiding disagreements is related to higher levels of intimacy and low levels of negativity in adolescents' friendships. Another possibility is that nonconfrontation is associated with more negativity and less emotional support because conflicts are not resolved in mutually satisfying ways (Laursen 1993). Thus, our examination of the associations between nonconfrontation strategies and friendship quality was exploratory.

Methodological Approach

Research on conflict resolution strategies in adolescent friendships is based primarily on a procedure whereby participants read a hypothetical situation and rate how they would handle themselves (e.g., Chung and Asher 1996; Iskandar et al. 1995; Jensen-Campbell et al. 1996; Selman et al. 1986). Several researchers have noted that when adolescents are given hypothetical conflicts to resolve, reporter biases inflate the frequency of negotiation and collaboration and minimize the frequency of control and avoidance (Laursen et al. 2001). It appears as though adolescents understand that they ought to attempt resolutions that are mutually satisfying for both parties, yet their actual behaviors may be less constructive in real life. Accordingly, the present study uses a non-hypothetical, self-report measure of conflict resolution developed in our pilot study based on the Dual Concern model (Pruitt and Carnevale 1993).

Hypotheses

In sum, we hypothesized relations between adolescents' conflict resolution strategies and their (1) cultural orientations and familism values, (2) gender-typed qualities, and (3) friendship qualities. Drawing on research highlighting the emphasis in Mexican culture on group harmony and accord (Delgado-Gaitan 1993; Triandis et al. 1984), we anticipated that strong ties to Mexican culture and strong familism values would be associated with higher levels of solution-oriented and avoidance strategies. Given values regarding self-orientation in Anglo culture (Tinsley 2001), we hypothesized that ties to Anglo culture would be positively associated with controlling resolution strategies. Our hypotheses regarding the role of gender were grounded in gender socialization perspectives (Maccoby 1990, 1998) suggesting that girls may use solution-oriented strategies more than boys and boys may use avoidance strategies more than girls. In addition, expressive personality qualities, which emphasize concern and sensitivity for others were expected to be linked to more solution-oriented strategies. Finally, we predicted that efforts to resolve conflicts in mutually satisfying ways (i.e., solution-orientation) would be linked to more intimacy and less negativity, and a focus on individual interests in resolving conflicts (i.e., controlling strategies) would be associated with less intimacy and more negativity in the friendship.

Method

Participants

The data came from a study of family socialization and adolescent development in Mexican American families (Updegraff et al. 2005). The 246 participating families were recruited through schools in and around a southwestern metropolitan area. Given the goal of the larger study, to examine normative family, cultural, and gender role processes in Mexican American families with adolescents, criteria for participation were as follows: (1) mothers were of Mexican origin; (2) 7th graders were living in the home and not learning disabled; (3) an older sibling was living in the home (in all but two cases, the older sibling was the next oldest child in the family); (4) biological mothers and biological or long-term adoptive fathers lived at home (all non-biological fathers had been in the home for a minimum of 10 years); and (5) fathers worked at least 20 h/week. Most fathers (i.e., 93%) also were of Mexican origin.

To recruit families, letters and brochures describing the study (in both English and Spanish) were sent to families, and follow-up telephone calls were made by bilingual staff to determine eligibility and interest in participation. Families' names were obtained from junior high schools in five school districts and from five parochial schools. Schools were selected to represent a range of socioeconomic situations, with the proportion of students receiving free/reduced lunch varying from 8 to 82% across schools. Letters were sent to 1,856 families with a Hispanic 7th grader who was not learning disabled. For 396 families (21%), the contact information was incorrect and repeated attempts to find updated information through school personnel or public listings were unsuccessful. An additional 42 (2.4) families moved between the initial screening and final recruitment contact, and 146 (10%) refused to be screened for eligibility. Eligible families included 421 families (23% of the initial rosters and 32% of those we were able to contact and screen for eligibility). Of those who were eligible (n = 421), 284 (or 67%) agreed to participate, 95 (23%) refused, and we were unable to recontact the remaining 42 families (10%) who were eligible to determine if they would participate. Interviews were completed by 246 families. Those who agreed but did not participate in the final sample (n = 38) were families that we were unable to locate to schedule the home interview, that were unwilling to participate when the interview team arrived at their home, or that were not home for repeated interview attempts. Because we had surpassed our target sample size (N = 240) we did not continue to recruit participants from the latter group.

Sample Characteristics

The younger adolescents in the family (the seventh grade target adolescents) were closely split between girls (n = 125) and boys (n = 121) and averaged 12.77 (SD = .58) years of age. The older adolescents were 50% girls and 50% boys and averaged 15.70 (SD = 1.54) years of age. The majority of both younger and older adolescents were born in the United States (62.2 and 53.7%, respectively) and the remaining were born in Mexico. Most of the adolescents (83%) spoke primarily English, and the remaining spoke Spanish.

Families represented a range of education and income levels. The percentage of families that met federal poverty guidelines was 18.3%, a figure similar to the 18.6% of two-parent Mexican American families living in poverty in the county from which the sample was drawn (U.S. Census, 2000). Median family income was $40,000 (for two parents and an average of 3.39 children). Mothers and fathers had completed an average of 10 years of education (M = 10.34; SD = 3.74 for mothers, and M = 9.88; SD = 4.37 for fathers). Most parents had been born outside the U.S. (71% of mothers and 69% of fathers); this subset of parents had lived in the U.S. an average of 12.4 (SD = 8.9) and 15.2 (SD = 8.9) years, for mothers and fathers, respectively. About two thirds of the interviews with parents were conducted in Spanish.

Procedures

Informed consent was obtained prior to the start of the home interview. Adolescents were interviewed individually using laptop computers in their preferred language (either English or Spanish). The interview took approximately 2 h to complete for both the seventh grade and older adolescents. Families received a $100 honorarium for participating in the home interview.

Measures

Adolescents identified their best friend as their closest same-sex friend; if they had several best friends, adolescents chose the friend they had known the longest. Adolescents were directed to think about this particular friendship when completing all measures in the study.

Summary of Pilot Study

A priority for our research was to include measures with demonstrated reliability and validity for Mexican American participants. Therefore, we conducted a pilot study of predominantly Mexican American (n = 172) adolescents from a low-income school district in the southwest United States. Data were collected in paper and pencil surveys from study hall classrooms chosen to target primarily 9th and 10th graders (12% of the students were in older grades). In this pilot sample, 22% of mothers and 20% of fathers did not complete high school, 31% of mothers and 24% of fathers had high school diplomas, and the remaining parents completed some college coursework. We developed our measure of conflict resolution, the foundation for the present study, from this pilot research and the psychometric assessment of the measure is detailed below.

Resolving Conflicts in Relationships Scale (RCR)

The RCR was developed to measure conflict resolution strategies in interpersonal relationships. The majority of the items were adapted from the Organizational Communication Conflict Instrument (OCCI; Putnam and Wilson 1982). This measure of adult conflict resolution has demonstrated high construct and predictive validity with adult samples (Putnam and Wilson 1982). We adapted this measure by including additional items from a conflict resolution measure developed after extensive focus groups with Mexican American parents (Ruiz et al. 1998). These items reflect how Mexican American families use subtle forms of negotiation and the phenomenon of “making peace” after a conflict episode. Finally, we chose items from a measure of conflict resolution used previously with adolescents (Bahr et al. 2002).

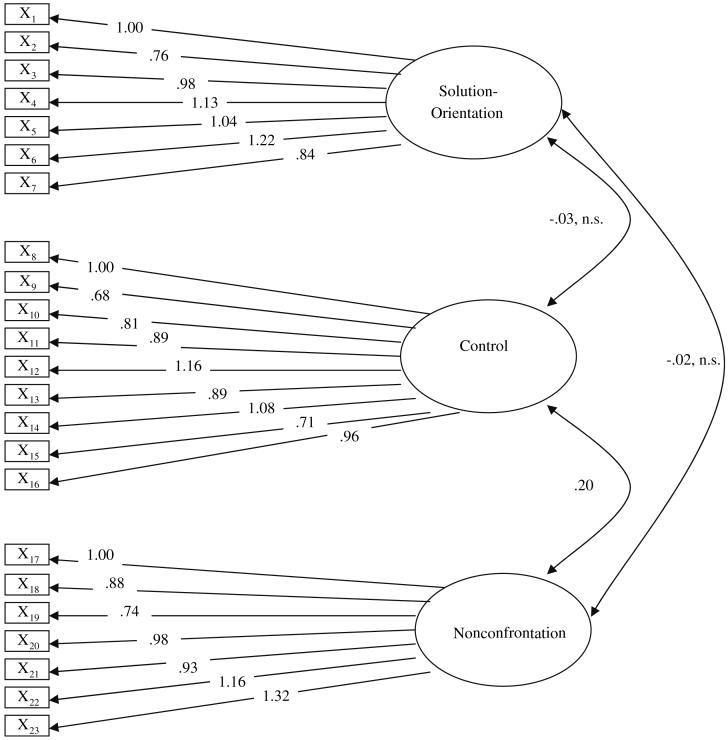

Using data from the pilot study, we first conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using Principle Axis Factoring techniques with a Promax rotation to formalize the subscales. The scree plot, rotated factor loadings, and eigenvalues indicated a three-dimension solution (Table 1). Seven items were eliminated because factor loadings were less than .40 or because the items double-loaded. All three subscales demonstrated adequate internal reliability; Cronbach's alphas were .84 for solution-orientation, .74 for nonconfrontation, and .73 for control. We then confirmed the structure of the scale by conducting a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on younger and older adolescents' conflict resolution using data from the present study. The CFA model included three latent constructs (see Fig. 1 for younger adolescents; the model for older adolescents was very similar and is not shown for brevity). Because estimates of the relations among latent variables are often positively biased when using the same reporter, the error terms of the indicators were correlated with each other (Kenny and Kashy 1992). We used Mplus (Muthen and Muthen 1999) to analyze the data using maximum likelihood estimation. The resulting model indicated good fit for both younger and older adolescents; χ2(205) = 274.28, p < .001; CFI = .95, RMSEA = .04; χ2(205) = 266.47, p < .01; CFI = .96, RMSEA = .03, respectively. Control and nonconfrontation were correlated (b = .20, p < .001; b = .22, p < .001 for younger and older adolescents, respectively), whereas solution-orientation was not correlated with control or nonconfrontation strategies. Cronbach's alphas were .74 for both younger and older adolescents' nonconfrontation, .84 for both younger and older adolescents' control, and .78 and .85 for younger and older adolescents' solution-orientation, respectively.

Table 1.

Rotated factor loadings of the resolving conflicts in relationships scale from PAF of pilot data (n = 159 Mexican American adolescents)a

| Nonconfrontation | Solution-orientation | Control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I avoid bringing up topics that my friend and I argue about | .45 | .12 | -.06 |

| I keep quiet about my views to avoid disagreements with my friend | .51 | .07 | -.09 |

| I hold back rather than argue with my friend | .58 | .13 | -.07 |

| I keep my feelings to myself when I disagree with my friend | .43 | -.11 | -.07 |

| I avoid my friend when we disagree | .62 | -.25 | .17 |

| I pretend things don't bother me so I don't have to argue with my friend | .54 | -.06 | .20 |

| I avoid discussing the problem with my friend | .61 | -.33 | .03 |

| I suggest we work together to create solutions to disagreements | .13 | .66 | -.01 |

| I offer many different solutions to disagreements | .32 | .56 | -.06 |

| My friend and I calmly discuss our differences when we disagree | -.12 | .58 | .17 |

| My friend and I talk openly about our disagreements | -.12 | .65 | .18 |

| I listen to my friend's point of view when we disagree | -.08 | .76 | -.03 |

| My friend and I work together to resolve disagreements | -.05 | .63 | -.03 |

| I like to reach a solution that my friend and I both agree to | -.02 | .69 | .03 |

| I argue with my friend without giving up my position | .07 | .05 | .40 |

| I raise my voice when trying to get my friend to accept my position | .09 | -.09 | .52 |

| I insist my position be accepted during a conflict with my friend | .13 | .16 | .42 |

| I refuse to give in to my friend when he/she disagrees with me | -.02 | .04 | .48 |

| I keep arguing until I get my way when my friend and I disagree | -.06 | -.18 | .64 |

| I have the last word when my friend and I disagree | -.02 | .03 | .61 |

| When my friend and I disagree, I want my view to win | -.04 | -.03 | .63 |

| I defend my opinion strongly with my friend | -.23 | .20 | .61 |

| When I feel I am right, I refuse to give in to my friend | -.12 | .00 | .70 |

Nonconfrontation accounted for 20.62% of the variance (eigenvalue = 6.19); solution-orientation accounted for 13.42% of the variance (eigenvalue = 4.03); control accounted for 7.44% of the variance (eigenvalue = 2.23)

Fig. 1.

Summary of confirmatory factor analysis for the RCR scale for younger adolescents (n = 243). Note: All coefficients are significant, p < .001 unless otherwise indicated

Cultural Orientations

Adolescents' cultural orientations were assessed using the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II (Cuéllar et al. 1995). This 30-item measure assesses Mexican cultural orientation (“I like to identify myself as a Mexican American”) and Anglo cultural orientation (I like to identify myself as an Anglo American”). Participants rate their agreement on a scale from 1, “Not at all,” to 5, “Extremely often or all the time.” This scale has demonstrated reliability and validity with Mexican American samples (Cuéllar et al. 1995). Cronbach's alphas were above .80 for both adolescents for both scales.

Familism

Older and younger adolescents completed the 16-item familism scale of the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale (Knight et al., under review). Five items were adapted from Sabogal et al. (1987) and the remaining items were developed through focus group work with Mexican American parents and adolescents. The items tapped adolescents' feelings of closeness in the family, obligations to the family, and adolescents' perceptions of their family as referent. Adolescents rated items (e.g., “Parents should teach their children that the family always comes first”) on a scale from 1, “Strongly disagree,” to 5, “Strongly agree.” Cronbach's alphas were above .86 for both adolescents' reports.

Gender-typed Personality Traits

Adolescents' gender-typed personality traits were assessed using an 18-item measure adapted from the Personality Characteristics Scale (PCS; Antill et al. 1993). Participants rated how much each statement described themselves on a scale from 1, “Almost never,” to 5, “Almost always.” Sample items include: “Competitive: This is the sort of person who tries hard to win and doesn't like other people to beat her/him,” and “Affectionate: This is the type of person who likes to show others how much s/he cares for them.” This adapted measure was included in the pilot study discussed above; it demonstrated high reliability for Mexican American adolescents, and cross-ethnic equivalency also was established. Higher scores indicated higher levels of expressivity and instrumentality and alphas ranged from .72 to .84 for both adolescents.

Friendship Intimacy

Adolescents completed an eight-item measure of relationship intimacy in their best friend relationships. The intimacy measure was originally developed by Blyth and Foster-Clark (1987). A sample item is “How much do you go to (friend name) for advice or support?” Answers ranged on a five-point scale from “Not at all” to “Very much,” with higher scores representing more intimate friendships. This measure has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity for Mexican American youth (Updegraff et al. 2002); alphas for the present study were .84 and .85 for younger and older adolescents, respectively.

Friendship Negativity

To assess relationship negativity in adolescents' best friendships, adolescents completed a five-item measure based on the conflict and antagonism subscales of Furman and Buhrmester's (1985) Network Relationship Inventory. The measure includes items about the extent to which the adolescent and his/her friend disagree, argue, and feel angry with each other. In prior work assessing friendship quality in a sample of Latino youth, the measure had acceptable alphas and factor structure (Updegraff et al. 2002). Participants rated how much the statements applied to their relationship on a five point scale ranging from “Not at all” to “Very much,” with higher scores indicating higher negativity. Alphas were .84 and .88 for younger and older adolescents, respectively.

Results

Results are organized to address the three goals of the present study. Means and standard deviations for all measures are listed in Table 2, and correlations among the study variables are in Table 3.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations of variables in the study separately for older and younger adolescents

| Older adolescents |

Younger adolescents |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Conflict resolution | ||||

| Nonconfrontation | 2.40 | .72 | 2.68 | .69 |

| Solution-orientation | 3.74 | .84 | 3.58 | .75 |

| Control | 2.66 | .77 | 2.56 | .76 |

| Cultural values | ||||

| Mexican orientation | 3.70 | .77 | 3.66 | .78 |

| Anglo orientation | 3.92 | .72 | 3.98 | .59 |

| Familism | 4.23 | .60 | 4.26 | .52 |

| Gender-typed personality traits | ||||

| Expressivity | 3.92 | .69 | 3.81 | .66 |

| Instrumentality | 3.69 | .63 | 3.65 | .65 |

| Friendship quality | ||||

| Intimacy | 3.93 | .70 | 3.76 | .71 |

| Negativity | 1.69 | .72 | 1.74 | .69 |

Table 3.

Correlations among variables for younger (above the diagonal) and older (below the diagonal) siblings (N = 246)

| Nonconfrontation | Solution-orientation | Control | Mexican Orientation | Anglo Orientation | Familism | Expressivity | Instrumentality | Intimacy | Negativity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonconfrontation | 0.21** | 0.35** | 0.08 | -0.03 | -0.01 | -0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.16* | |

| Solution-orientation | 0.06 | 0.17** | -0.01 | 0.14* | 0.19** | 0.30** | 0.21** | 0.38** | -0.15* | |

| Control | 0.31** | 0.04 | -0.05 | -0.02 | 0.00 | -0.10 | 0.29** | -0.01 | 0.33** | |

| Mexican orientation | 0.12 | -0.04 | 0.03 | -0.34** | 0.09 | 0.06 | -0.18** | -0.04 | -0.03 | |

| Anglo orientation | 0.01 | 0.16* | 0.12 | -0.42** | 0.09 | 0 22** | 0.29** | 0.17** | 0.04 | |

| Familism | 0.09 | 0.19** | -0.01 | 0.17* | 0.06 | 0.22** | 0.07 | 0.15* | -0.10 | |

| Expressivity | 0.06 | 0.40** | -0.01 | -0.01 | 0.29** | 0.26** | 0.34** | 0.13* | 0.01 | |

| Instrumentality | -0.05 | 0.32** | 0.23** | -0.17** | 0.45** | 0.03 | 0.40** | 0.24** | 0.09 | |

| Intimacy | -0.01 | 0.48** | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.24** | 0.30** | 0.31** | -0.13* | |

| Negativity | 0.19** | -0.23** | 0.40** | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.02 | -0.12 | 0.02 | -0.16* |

p < .05

p < .01

Goal 1: Describe Conflict Resolution in Mexican American Adolescents' Friendships

To describe the conflict resolution strategies used within younger and older adolescents' friendships, we ran 2 (Adolescent Gender) × 3 (Strategy: nonconfrontation, solution-orientation, and control) mixed-model ANOVAs with gender as the between-subjects factor and strategy as the within-subjects effect, separately for younger and older adolescents. We calculated Cohen's d (Cohen 1988) as a measure of effect size for all analyses; adjusted effect size measures were computed for within-group analyses (Cortina and Nouri 2000).

The pattern of results was similar for younger and older adolescents. A main effect for strategy was significant for both younger and older adolescents, F(2, 243) = 189.73, p < .001; F(2, 240) = 251.81, p < .001, respectively. Post-hoc tests showed that adolescents reported using solution-orientation more frequently than nonconfrontation (for younger adolescents, d = 1.24; for older adolescents, d = 1.72) and control (for younger adolescents, d = 1.35; for older adolescents, d = 1.27). Further, younger and older adolescents reported using nonconfrontation more than control, d = .17 and d = .36, respectively.

These main effects were qualified by significant strategy × gender interactions for both younger and older adolescents, F(2, 243) = 15.12, p < .001; F(2, 240) = 33.12, p < .001, respectively. Follow up tests revealed that girls reported using more solution-oriented strategies than boys (for younger adolescents, M = 3.75, SD = .71, for girls, M = 3.40, SD = .75, for boys, d = .48; for older adolescents, M = 4.07, SD = .74, for girls, M = 3.42, SD = .81, for boys, d = .84) and boys used more controlling strategies than did girls (for younger adolescents, M = 2.43, SD = .78, for girls, M = 2.69, SD = .72, for boys, d = .35; for older adolescents, M = 2.49, SD = .74, for girls, M = 2.84, SD = .77, for boys, d = .46). There were no gender differences in adolescents' reports of nonconfrontation.

To examine the relations between cultural orientations, familism values, and adolescents' conflict resolution strategies, we tested a series of multilevel models using SAS PROC MIXED. This approach is advantageous because it extends multiple regression to address the non-independence of nested data. In the present study, siblings were nested in families and we tested for differences in conflict resolution by birth order (i.e., older versus younger sibling).

The model partitioned the variance into two levels. At Level 1, the between-sibling model, predictor variables that differed across dyad members (i.e., age, birth order, gender, Anglo cultural orientation, Mexican cultural orientation, and familism) were included. To ease interpretation and to reduce multicollinearity, continuous variables were centered at their mean after data from siblings were pooled. Dichotomous variables were effect coded (i.e., for birth order, -1 versus 1 indicates younger versus older sibling; for gender, -1 versus 1 indicates boy versus girl) and interactions with birth order were included (i.e., Mexican orientation × birth order, Anglo orientation × birth order, and Familism × birth order). At Level 2, the between-family model, parental education (a variable common across siblings within the same family) was included as a control; including parental education was important because scholars suggest that studies of ethnic minority families often confound cultural background and socioeconomic status (McLoyd 1998). Analyses were conducted separately by conflict resolution strategy. Effect size estimates were calculated by adjusting the gamma weights to create effect sizes comparable to Cohen's d that control for all variables in each model (W. Osgood, personal communication, January 13, 2005). The model equations are detailed in the Appendix.

Predicting Solution-orientation

The multilevel model revealed that parental education was positively associated with solution-oriented strategy use, γ = .02, SE = .01, p < .05, d = .09. A significant gender effect revealed that girls used more solution-oriented strategies than did boys, γ = -.47, SE = .06, p < .001, d = .63. Finally, familism was positively associated with adolescents' use of solution-oriented strategies, γ = .22, SE = .06, p < .001, d = .17. There were no significant interactions between cultural variables and birth order, suggesting that these effects were consistent for older and younger siblings.

Predicting Control

The model predicting controlling resolution strategies revealed a significant gender effect indicating that boys used more controlling resolution strategies than did girls, γ = .29, SE = .07, p < .05, d = .39. There were no associations between control resolution strategies and age, birth order, or the cultural variables.

Predicting Nonconfrontation

The model predicting nonconfrontational resolution strategies revealed a significant age effect suggesting that age is negatively associated with the use of nonconfrontational resolution strategies, γ = -.08, SE = .02, p < .001, d = .23. Additionally, a main effect for Mexican orientation approached significance in the direction we hypothesized suggesting that Mexican orientation is positively related to use of nonconfrontational resolution strategies, γ = .08, SE = .04, p = .06, d = .09. No other predictors were significant.

Goal 2: To Examine the Links Between Gender-typed Qualities and Conflict Resolution

We used a similar analytic approach for assessing the links between adolescents' conflict resolution strategy use and gender and gender-linked personality qualities. At Level 1 we included adolescents' age, birth order, gender, expressive and instrumental personality qualities and interaction terms for birth order (i.e., expressivity × birth order, instrumentality × birth order). At Level 2 we included parental education.

Predicting Solution-orientation

As expected, the model predicting adolescents' solution-oriented resolution strategies revealed a significant positive effect for expressivity, γ = .30, SE = .05, p = .001, d = .27. Contrary to our hypotheses, however, a significant positive effect for instrumentality also emerged, γ = .13, SE = .05, p < .01, d = .11. There were no significant interactions with birth order suggesting that the effects were consistent for the two siblings; expressive and instrumental qualities were linked to adolescents' use of solution-orientation.

Predicting Control

As predicted, adolescents' use of controlling conflict resolution strategies was negatively related to expressivity, γ = -.17, SE = .05, p = .001, d = .15, and positively related to instrumentality, γ = .36, SE = .06, p = .001, d = .31. Further, as discussed above, a significant effect for gender indicated that boys used more controlling strategies than girls, but neither age nor birth order were associated with controlling resolution strategies.

Predicting Nonconfrontation

Age was positively associated with younger and older adolescents' use of nonconfrontation (discussed above). Further, parental education was negatively associated with adolescents' use of nonconfrontational resolution strategies, γ = -.02, SE = .01, p < .05, d = .11.

Goal 3: To Examine the Relations Between Conflict Resolution and Friendship Quality

Finally, we tested the links between adolescents' conflict resolution strategy use and their reports of friendship quality using a similar multilevel model. At Level 1 we included age, birth order, gender, and conflict resolution strategies. We also included interaction terms to test resolution strategy × birth order effects. At Level 2 we included parental education.

Predicting Intimacy

A significant gender effect emerged indicating that girls reported more intimate friendships than did boys, γ = -.62, SE = .05, p < .001, d = .87. Further, as predicted, a significant effect for solution-orientation revealed that friendship intimacy was positively related to solution-oriented strategies, γ = .37, SE = .03, p < .001, d = .39.

Predicting Negativity

All three main effects for conflict resolution strategies were significant in the expected directions. Solution-oriented strategies were negatively related to friendship negativity, γ = -.25, SE = .04, p < .001, d = .27, whereas nonconfrontational and controlling strategies were positively related to friendship negativity, γ = .16, SE = .05, p < .001, d = .15 and γ = .29, SE = .04, p < .001, d = .31, respectively. These associations were consistent across siblings.

Discussion

This study drew on models of culture and gender socialization in examining Mexican American adolescents' conflict resolution strategies with their close friends. The modest findings contribute to a growing literature on normative developmental processes in ethnic minority youth by providing descriptive information about Mexican American adolescents' conflict resolution strategies and exploring the role of cultural orientations and values and gender-typed qualities and to our understanding of the cultural context of ethnic minority friendship processes more broadly (Azmitia et al. 2006; Way 2006). In addition, by assessing the links between conflict resolution and relationship quality, the findings provide a foundation for future applied research directed at promoting positive social relationships for Mexican American youth.

Mexican American adolescents in this sample reported using solution-oriented conflict resolution strategies most often to resolve conflicts and disagreements with their close friends, and nonconfrontation and control less often. Considering that adolescents were reporting on their best friend relationships, cooperative strategies should be most common. This pattern of findings also is consistent with prior research suggesting that strategies demonstrating a concern for others (e.g., accommodation, solution-orientation) are common in relationships that are open to dissolution (Laursen et al. 2001) and with developmental perspectives suggesting that adolescents understand the consequences of conflict and that successful resolution of conflict is an important element of remaining friends (Laurson et al. 1996; Selman et al. 1986). It is important to note that adolescents were asked to identify a close friend, and if they had more than one close friend, to think about the friend they had a relationship with for the longest period of time. Thus, these findings reflect strategies adolescents reported using in close dyadic (same-sex) friendships and may be different from those used with casual acquaintances. Learning about the strategies used in different types of peer relationships (e.g., opposite-sex friendships, acquaintance relationships) will be an important direction of future research.

Adolescents' Cultural Orientations and Values and Conflict Resolution

This study examined the role of adolescents' cultural orientations and familistic values to learn how within-group variations in cultural processes may be associated with adolescents' conflict resolution skills. Modest associations were found between adolescents' familistic values and their use of solution-oriented strategies (i.e., working together to find a solution that is agreeable to both partners in the relationship) with close friends. To the extent that adolescents adopt values that reflect the importance of putting their family's needs before their own and maintaining harmony within the family, adolescents may be more likely to resolve conflicts outside of the family using strategies that reflect putting the friendship above their individual preferences.

Contrary to our expectations, we did not find associations between adolescents' global orientations toward Mexican and Anglo culture (i.e., the extent that adolescents are involved in Anglo and Mexican culture, as indicated by language usage, affiliations, etc.) and the strategies they used to resolve their conflicts with friends. This pattern of findings—revealing associations with conflict resolution for adolescents' familistic values but not their global orientations toward Mexican and Anglo culture—suggests that it is important to examine the specific cultural values and beliefs that may underlie relationship processes and outcomes rather than more global indices of cultural involvement (Gonzales et al. 2002). In future studies, it will be important to explore the links between other cultural values (e.g., individualism, collectivism, simpático) and conflict resolution practices to learn more about conflict resolution in Mexican American culture.

Gender and Conflict Resolution

Consistent with Maccoby's (1998) ideas, girls were more likely to report solution-oriented strategies, whereas boys were more likely to use control. The greater significance that girls place on close interpersonal relationships is consistent with their more frequent use of solution-oriented strategies, an approach that is likely to maintain close relationships. Boys, in contrast, tend to spend more time in larger group situations and in this study tended to use controlling strategies with their close friends, the types that may be most effective in all male social groups (Maccoby 1998). These gender differences may be exacerbated by our self-report strategies to the extent that girls and boys are more likely to describe using strategies that are defined as socially appropriate in same-sex interactions (i.e., negotiation and compromise among girls and control/dominance strategies among boys). Future work using observational methodology to examine gender differences in conflict resolution strategies will further our understanding of these processes.

We also examined the role of gender-typed personality qualities in adolescent conflict resolution, finding some modest associations. Consistent with our expectations, expressivity was positively associated with solution-oriented strategies and negatively associated with control strategies. Instrumental personality qualities, on others hand, were positively related both to strategies promoting individual needs and achievement (i.e., control) and to those promoting friendship goals (i.e., solution-orientation). The Dual Concern model (Pruitt 1982; Pruitt and Carnevale 1993), which suggests that the conflict strategies a person adopts is dependent upon his or her concern for oneself versus others, may partially explain these findings. Since empathetic concern for others is indicative of expressive personality qualities, it is not surprising that expressivity was linked to strategies that emphasize concern for others (i.e., solution-orientation). In contrast, competitive and dominating behaviors indicative of instrumental personality qualities suggest low concern for others. Consistent with this idea, we found that instrumentality was associated with controlling resolution strategies. However, the positive association between instrumentality and solution-orientation was unexpected. It is notable that instrumentality was positively associated with solution-orientation when expressive qualities were included in the model, suggesting that it will be important to consider how instrumentality and expressivity in combination are linked to conflict resolution strategies in future work.

We did not find gender differences in adolescents' use of nonconfrontation strategies (i.e., avoiding conflicts, failing to express one's own views). Nor did we find that non-confrontation strategies were associated with expressive or instrumental personality qualities. The reasons that adolescents avoid resolving conflicts may depend more on the nature of the conflict (e.g., they may avoid conflicts about sensitive issues) or the type of relationship (e.g., friendship versus parent-adolescent relationship) than on gender socialization processes.

Conflict Resolution and Friendship Quality

Conflict resolution is an important skill in the maintenance and quality of the friendship (Laursen and Collins 1994). Consistent with this idea, our findings revealed that solution-oriented strategies consistently were associated with friendship intimacy. Similar to findings with adults (Haferkamp 1992), favoring solution-oriented strategies was positively related to the degree of intimacy that adolescents perceived in their close friendships; however, the direction of these effects is not clear. Sullivan (1953) suggested that intimacy develops in relationships through self-disclosure and sharing. This may lead to better perspective taking and more concern for others' outcomes in a conflict situation. On the other hand, it may be that use of resolution strategies that demonstrate high concern for others leads to increased intimacy in the relationship. Laursen (1993) noted that adolescents perceived themselves as closer to their friend upon successful resolution of a conflict. The correlational design of the present study did not allow for interpretations of the direction of effect; future research should examine the bidirectional nature of the link between conflict resolution and friendship intimacy over time.

Contrary to our hypotheses, nonconfrontation and control were not related to intimacy. We predicted that these strategies would involve little consideration of the partner's well-being and would be negatively related to friendship intimacy. It may be that competitive and avoidant conflict resolution behaviors are not destructive in all types of interpersonal relationships. Although research with adult married samples suggests that avoidant and competitive behaviors are detrimental to relationship intimacy (Gottman and Krokoff 1989), conflict resolution strategies may have only limited relation to intimacy in best-friend relationships due to the open nature of the relationship. Further, cultural beliefs valuing group harmony are common for Mexican American individuals (Delgado-Gaitan 1993; Triandis, et al. 1984); it may be that for Mexican American adolescents, nonconfrontational resolution strategies are less detrimental to friendship intimacy because such avoidant behaviors are thought to maintain group accord.

All three conflict resolution strategies were associated with adolescents' reports of friendship negativity in the expected directions. When adolescents used more constructive strategies, there was less negativity in the friendship. And, when Mexican American adolescents used less adaptive strategies, specifically, controlling and avoidant resolution practices, higher levels of negativity were reported. These findings are consistent with the Dual Concern model (Pruitt 1982; Pruitt and Carnevale 1993). Because collectivistic cultures place a strong emphasis on concern for the group, the importance of being empathetic in conflict situations may be particularly important. Further, resolution strategies that emphasize self-interest (i.e. control) were negatively related to relationship quality; these strategies may be particularly harmful for Mexican American adolescents considering that controlling strategies focus on individual needs.

Limitations and Directions for Future Study

The present study was limited in its use of self-report measures gathered from adolescents. It will be important in future work to approach the study of Mexican American adolescents' conflict resolution from a dyadic perspective, taking into account how each member of the dyad describes the conflict resolution strategies employed and how the strategies of both partners are associated with the qualities of the friendship. In addition, very few researchers have observed the conflict resolution strategies that adolescents use in their friendships. Considerable attention has been directed at how the “insiders” of adolescent friendships perceive conflict resolution; an “outsider” perspective (i.e., observational research) will provide new insights about adolescent conflict resolution.

Our sample represented a specific group of Mexican American youth, i.e., those from two-parent predominantly immigrant families living in the southwestern U.S. As such, it will be important in future work to expand this research to include Mexican American youth who represent the diversity of this cultural group in the U.S. (e.g., youth from urban areas, border towns, later-generation families). Finally, future longitudinal work that includes multiple assessments of adolescents' cultural values, conflict resolution strategies, and friendship qualities will be important in shedding light on whether strong friendships produce better conflict resolution or better conflict resolution strategies promote stronger relationships.

Conclusion

In closing, we note that the present study contributes to the literature on adolescent conflict resolution in several ways. First, we took a first step in describing a normative social development dynamic in Mexican American adolescents by assessing the conflict resolution strategies adolescents described in their friendships and examining how they were linked to cultural values, gendered personal qualities, and friendship quality. As a corollary, the present study also examined the psychometric properties of a self-report measure of conflict resolution developed for Mexican American youth and designed to explore three types of conflict resolution strategies. Finally, we identified some of the conflict resolution strategies that may be central to promoting friendships for Mexican American adolescents. It will be important in future research to examine how conflict resolution strategies are related to other aspects of friendship quality and social development.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the families and youth who participated in this project, and to the following schools and districts who collaborated: Osborn, Mesa, and Gilbert school districts, Willis Junior High School, Supai and Ingleside Middle Schools, St. Catherine of Sienna, St. Gregory, St. Francis Xavier, St. Mary-Basha, and St. John Bosco. We thank Susan McHale, Ann Crouter, Mark Roosa, Nancy Gonzales, Roger Millsap, Jennifer Kennedy, Lorey Wheeler, Devon Hageman, and Lilly Shanahan for their assistance in conducting this investigation and Ann Crouter and Susan McHale for their comments on this paper. Funding was provided by NICHD grant R01HD39666 (Kimberly Updegraff, Principal Investigator, Ann C. Crouter and Susan M. McHale, co-principal investigators, Mark Roosa, Nancy Gonzales, and Roger Millsap, co-investigators) and the Cowden Fund to the School of Social and Family Dynamics at ASU.

Biographies

Shawna Thayer is currently a Quantitative Analyst for American Girl, a subsidiary of Mattel, Inc. She received her Ph.D. in Family Science from Arizona State University with major research interests in conflict resolution and adolescent development.

Kimberly Updegraff is an Associate Professor in the School of Social and Family Dynamics at Arizona State University. Her research focuses on culture and gender socialization processes in family and peer relationships.

Melissa Delgado is a doctoral candidate in the School of Social and Family Dynamics at Arizona State University; she is interested in culture, achievement, and adjustment in Mexican American youth.

Appendix

Goal 1 Models: Exploring the Links Between Culture and Conflict Resolution

Level 1:

CRij = β0j + β1j(Ageij) + β2j(Birth Orderij) + β3j(Genderij) + β4j(Anglo Cultural Orientationij) + β5j(Mexican Cultural Orientationij) + β6j(Familismij) + β7j(Anglo Cultural Orientationij × Birth Orderij) + β8j(Mexican Cultural Orientationij × Birth Orderij) + β9j(Familismij × Birth Orderij) + rij

Level 2:

β0j = γ00 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ0j

β1j = γ10 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ1j

β2j = γ20 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ2j

β3j = γ30 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ3j

β4j = γ40 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ4j

β5j = γ50 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ5j

β6j = γ60 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ6j

β7j = γ70 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ7j

β8j = γ80 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ8j

β9j = γ90 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ9j

Where for member i in family j, CRij = Conflict Resolution (Solution-orientation, Control, or Nonconfrontation).

Goal 2 Models: Exploring the Links Between Gender and Conflict Resolution

Level 1:

CRij = β0j + β1j(Ageij) + β2j(Birth Orderij) + β3j(Genderij) + β4j(Expressivityij) + β5j(Instrumental-ityij) + β6j(Expressivityij × Birth Orderij) + β7j(Instrumentatlityij × Birth Orderij) + rij

Level 2:

β0j = γ00 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ0j

β1j = γ10 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ1j

β2j = γ20 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ2j

β3j = γ30 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ3j

β4j = γ40 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ4j

β5j = γ50 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ5j

β6j = γ60 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ6j

β7j = γ70 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ7j

Where for member i in family j, CRij = Conflict Resolution (Solution-orientation, Control, or Nonconfrontation).

Goal 3 Models: Exploring the Links Between Conflict Resolution and Friendship Quality

Level 1:

FQij = β0j + β1j(Ageij) + β2j(Birth Orderij) + β3j(Genderij) + β4j(Solution-Orientationij) + β5j(Nonconfrontationij) + β6j(Controlij) + β7j(Solution-Orientationij × Birth Orderij) + β8j(Nonconfrontationij × Birth Orderij) + β9j(Controlij × Birth Orderij) + rij

Level 2:

β0j = γ00 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ0j

β1j = γ10 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ1j

β2j = γ20 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ2j

β3j = γ30 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ3j

β4j = γ40 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ4j

β5j = γ50 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ5j

β6j = γ60 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ6j

β7j = γ70 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ7j

β8j = γ80 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ8j

β9j = γ90 + γ01(Parent Educationj) + μ9j

Where for member i in family j, FQij = Friendship Quality (Intimacy or Negativity).

References

- Antill JK, Russell G, Goodnow JJ, Cotton S. Measures of children's sex typing in middle childhood. Australian Journal of Psychology. 1993;45:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Azmitia M, Ittel A, Brenk C. Latino-heritage adolescents' friendships. In: Chen X, French DC, Schneider BH, editors. Peer relationships in cultural context. Cambridge University Press; NY: 2006. pp. 426–451. [Google Scholar]

- Baca-Zinn M. Adaptation and continuity in Mexican-origin families. In: Taylor RL, editor. Minority families in the United States: A multicultural perspective. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1994. pp. 64–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bahr (Thayer) SM, Updegraff KA, Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL. Getting along: Conflict resolution strategies in adolescent friendships. Poster presented at the Society for Research on Adolescence; New Orleans, LA. 2002, April. [Google Scholar]

- Bem S. The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1974;42:155–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ. The features and effects of friendship in early adolescent. Child Development. 1982;53:1447–1460. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In: Chun KM, Organista PB, Marín G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2003. pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow BJ, LaGaipa JJ. The development of friendship values and choice. In: Chapman AJ, et al., editors. Friendship and social relations in children. Transaction Publishers; New Brunswick, NJ: 1980. pp. 15–44. [Google Scholar]

- Blyth DA, Foster-Clark F. Gender differences in perceived intimacy with different members of adolescents' social networks. Sex Roles. 1987;17:689–718. [Google Scholar]

- Boldizar JP. Assessing sex typing and androgyny in children: The Children's Sex Role Inventory. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:505–515. [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa LJ. Measuring acculturation: Where we are and where we need to go. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003;25:127–146. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodríguez M. Latino families: Myths and realities. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States. Praeger Press; Westport, CT: 2002. pp. 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Chung TY, Asher SR. Children's goals and strategies in peer conflict situations. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1996;42:125–147. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cortina JM, Nouri H. Effect size for ANOVA designs. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Crohan SE. Marital happiness and spousal consensus on beliefs about marital conflict: A longitudinal investigation. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1992;9:89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar I, Arnold B, Maldonado R. Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II: A revision of the original ARSMA scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17:275–304. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Gaitan C. Parenting in two generations of Mexican American families. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1993;16:409–427. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J, Herrera C. Conflict resolution with friends, siblings, and mothers: A developmental perspective. Aggressive Behavior. 1997;23:343–357. [Google Scholar]

- French DC, Lee O, Pidada SU. Friendships of Indonesian, South Korean, and U.S. youth: Exclusivity, intimacy, enhancement of worth, and conflict. In: Chen X, French DC, Schneider BH, editors. Peer relationships in cultural context. Cambridge University Press; NY: 2006. pp. 379–402. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Children's perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental psychology. 1985;56:1016–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development. 1992;63:103–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielidis C, Stephan WG, Ybarra O, Dos Santos Pearson VM, Villareal L. Preferred styles of conflict resolution: Mexico and the United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1997;28:661–677. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Morgan-Lopez AA, Saenz D, Sirolli A. Acculturation and the mental health of Latino youths: An integration and critique of the literature. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States. Praeger Press; Westport, CT: 2002. pp. 45–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Krokoff LJ. Marital interaction and satisfaction: A longitudinal view. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:47–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haferkamp CJ. Orientations to conflict: Gender, attributions, resolution strategies, and self-monitoring. Current Psychology: Research and Reviews. 1992;10:227–240. [Google Scholar]

- Hagen JW, Nelson MJ, Velissaris N. Comparison of research in two major journals on adolescence. Poster session presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence; Baltimore, MD. 2004, March. [Google Scholar]

- Hartup WW. Adolescents and their friends. In: Laursen B, editor. New directions for child development: Close friendships in adolescence. Jossey-Bass Publishers; San Francisco: 1993. pp. 3–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede GH. Culture's consequences: International differences in work-related values. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Iskandar N, Laursen B, Finkelstein B, Fredrickson L. Conflict resolution among preschool children: The appeal of negotiation in hypothetical disputes. Early Education and Development. 1995;6:359–376. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Campbell LA, Graziano WG, Hair EC. Personality and relationships as moderators of interpersonal conflict in adolescence. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1996;42:148–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA. Analysis of the multitraitmultimethod matrix by confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Saenz DS, Deardorff J, German M, Sirolli A, Fernandez C, Updegraff KA. The Mexican American Cultural Values Scale. (under review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B. The perceived impact of conflict on adolescent relationships. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1993;39:535–550. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B. Closeness and conflict in adolescent peer relationships: Interdependence with friends, romantic partners. In: Bukoski WM, Newcomb AF, Hartup WW, editors. The company they keep: Friendship in childhood and adolescence. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1996. pp. 186–210. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Collins WA. Interpersonal conflict during adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:197–209. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Finkelstein BD, Townsend Betts N. A developmental meta-analysis of peer conflict resolution. Developmental Review. 2001;21:423–449. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. The two sexes: Growing up apart, coming together. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. Gender and relationships: A developmental account. American Psychologist. 1990;45:513–520. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín B, Marín B. Research with Hispanic populations. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Changing demographics in the American population: Implications for research on minority children, adolescents. In: McLoyd VC, Steinberg L, editors. Studying minority adolescents: Conceptual, methodological, and theoretical issues. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahway, NJ: 1998. pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus: The comprehensive modeling program for applied researchers: User's guide. Los Angeles, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:499–514. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt DG. Negotiation behavior. Academic Press; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt DG, Carnevale PJ. Negotiation in social conflict. Brooks/Cole; Pacific Grove, CA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam LL, Wilson CE. Communicative strategies in organizational conflicts: Reliability and validity of a measurement scale. Organizational Communication. 1982;4:629–652. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz SY, Gonzales NA, Formoso D. Multicultural, multidimensional assessment of parent-adolescent conflict. Poster presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence; San Diego, CA. 1998, March. [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F, Marín G, Otero-Sabogal R, Vanoss Marín B, Perez-Stable EJ. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn't? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Selman RL, Beardslee W, Schultz l. H., Krupa M, Podorefsky D. Assessing adolescent interpersonal negotiation strategies: Toward the integration of structural and functional models. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:450–459. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan HS. The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. Norton; New York: 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Tinsley CH. How negotiators get to yes: Predicting the constellation of strategies used across cultures to negotiate conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2001;4:583–593. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.4.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjosvold D. Cooperative and competitive goal approach to conflict: Accomplishments and challenges. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 1998;47:285–342. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC, Marin G, Lisanksy J, Betancourt H. Simpatica as a cultural script of Hispanics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;47:1363–1375. [Google Scholar]

- Trubisky P, Ting-Toomey S, Lin S. The influences of individualism-collectivism and self-monitoring on conflict styles. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1991;15:65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker CJ, McHale SM, Crouter AC. Conflict resolution: Links with adolescents' family relationships and individual well-being. Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24:715–736. [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, Madden-Derdich DA, Estrada AU, Sales LJ, Leonard SA. Young adolescents' experiences with parents and friends: Exploring the connections. Family Relations. 2002;51:72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, McHale SM, Whiteman SD, Thayer SM, Delgado MY. Adolescents' sibling relationships in Mexican American families: Exploring the role of familism. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:512–522. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way N. The cultural practice of close friendships among urban adolescents in the United States. In: Chen X, French DC, Schneider BH, editors. Peer relationships in cultural context. Cambridge University Press; NY: 2006. pp. 403–425. [Google Scholar]

- Williams N. The Mexican American Family: Tradition and Change. General Hall, Inc.; Dix Hills, New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Youniss J, Smollar J. Adolescent relations with mothers, fathers, and friends. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1985. [Google Scholar]