Summary

Non-protein-coding (nc) RNAs are diverse in their modes of synthesis, processing, assembly, and function. The inventory of transcripts known or suspected to serve their biological roles as RNA has increased dramatically in recent years. Although studies of ncRNA function are only beginning to match the pace of ncRNA discovery, some principles are emerging. Here we focus on a framework for understanding functions of ncRNAs that have evolved in a protein-rich cellular environment, as distinct from ncRNAs that arose originally in the ancestral RNA World. The folding and function of ncRNAs in the context of ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes provide myriad opportunities for ncRNA gain of function, leading to a modern-day RNP Renaissance.

Introduction

Many eukaryotic genomes have a relatively sparse content of protein-coding loci. However, substantial regions beyond those devoted to protein-coding mRNA production are transcribed [1]. The rapid increase in ncRNA discovery has outpaced functional studies or even a system of annotation based on transcript biogenesis, processing, or fate. Still, broad classes of ncRNAs have emerged. Even the most short-lived transcripts, those degraded at the site of synthesis, can have significant biological activities. Indeed, at least some of the cis-acting natural antisense RNAs and ncRNAs that regulate gene expression, chromatin dynamics, and chromosome structure could function primarily as nascent transcripts [2–4]. Other transcripts, produced from a single DNA strand or synthesized in a bidirectional manner, form inter-or intramolecular duplexes to yield the ~20–30 nucleotide small RNA molecules that direct RNA silencing-related pathways [5].

This review focuses on a third class of functional ncRNA, which for simplicity here will be designated as structured ncRNA. The term “structured” is intended in a broad sense, referring to folded motifs that may be interspersed within a larger, mostly unstructured transcript or that may fold only in association with a particular ligand. The function of ncRNAs in this category is generally envisioned to require biologically stable accumulation, conferred by association with one or more proteins. RNPs that harbor ncRNAs have many possible forms, with static or dynamic subunit compositions and RNA-protein interactions of varying degrees of sequence- or structure-specificity.

Some structured ncRNAs emerged as functional molecules relatively early in evolution and in their extant versions can be considered descendants of an ancestral RNA World. However, the majority of ncRNAs appear to have evolved more recently. Here, we explore the properties of ncRNAs that evolved in a protein-rich cellular environment, in contrast with the ancestral ncRNAs that developed function prior to their acquisition of protein partners (or the very existence of proteins). This evolutionary distinction has implications for ncRNA function, as discussed in the first section below. Subsequent sections illuminate distinct mechanisms of ncRNA function, including ncRNA roles as scaffolds of macromolecular complex assembly, hybridization guides, templates for polymer synthesis, and beyond. Importantly, the selected ncRNA examples illustrate a range of evolutionary scenarios: acquisition of function by a novel transcript, diversification of RNPs assembled by a single ncRNA, and diversification of a ncRNA family that retains shared protein partners.

The RNP Renaissance

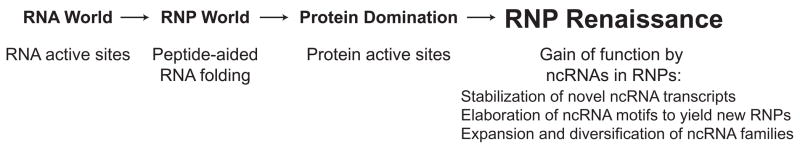

Current versions of the structured ncRNAs that debuted early, arising in a RNA-dominated World, have been paradigms for insights about fundamental principles of RNA folding and catalytic mechanisms [6]. These ncRNAs are proposed to have evolved their protein interaction partners in an early RNP World (Figure 1), driven by the ability of short peptides to improve and regulate RNA folding and function [7]. Following the transition to a largely Protein World, rich with protein enzyme active sites, the selective pressure for evolution of new catalytic RNAs would have been low [8]. However, predominance of protein-based catalysis has not halted the acquisition of new functions by ncRNAs [9]. Instead, we propose that the rich diversity of RNA-protein interaction modes evident in modern organisms facilitates ncRNA gain of function in the context of RNPs. To emphasize the important distinctions between ancestral and ‘modern-day’ evolution of function by ncRNAs, the post-protein explosion of ncRNA complexity can be termed the RNP Renaissance (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A modern-day RNP Renaissance. A putative series of evolutionary transitions is illustrated based on the suspected origin of life in an ancestral RNA World, followed by the rise of an early RNP World in which proteins facilitated the folding and catalytic activity of RNAs, eventually superceded by an explosion of protein complexity and the domination of enzymes with protein active sites. Based on widespread evidence for an ongoing evolutionary expansion of ncRNA complexity, we designate a modern-day RNP Renaissance distinct from the early RNP World in its protein-rich context for ncRNA gain of function.

RNPs with a ncRNA platform for protein assembly

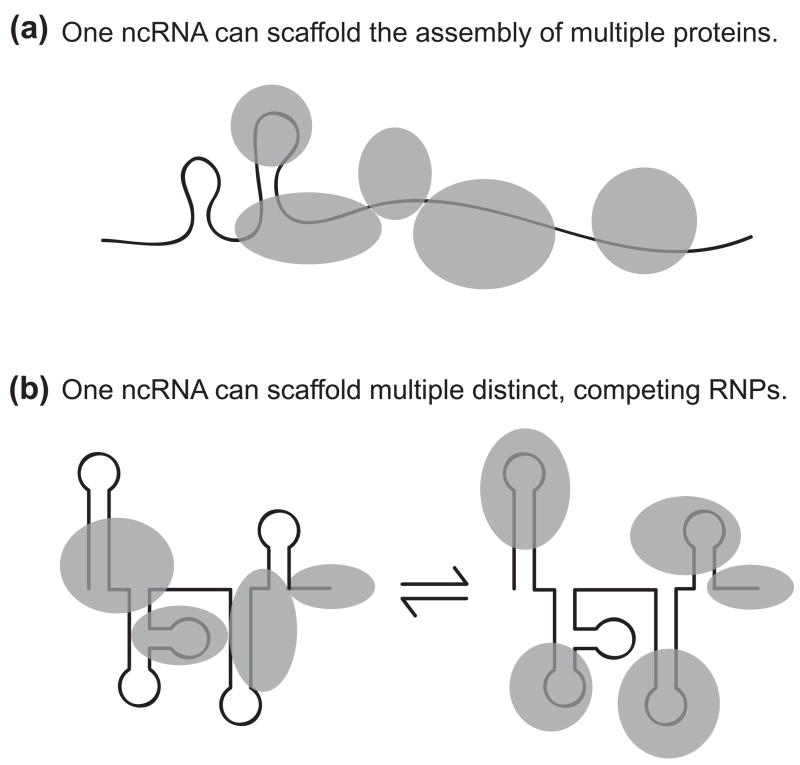

A well-documented, logical role for structured ncRNAs of the RNP Renaissance is to act as versatile platforms for protein assembly (Figure 2). This role capitalizes on the prior evolution of a large inventory of protein folds and an enormous structural diversity of protein-RNA interactions. Transcription can support synthesis of extremely long RNA polymers in vivo, and yet only short motifs are required for highly specific protein interactions. These features make RNA well suited for gain of function as a protein-bridging platform of macromolecular assembly. Indeed, the functions of most structured ncRNAs are likely to depend at least in part on their protein-scaffolding abilities.

Figure 2.

Non-coding RNA function as a scaffold of macromolecular assembly. The ability of even small RNA motifs (of less than 20 nucleotides) to fold uniquely and with high thermodynamic stability is one of several features that suggest ncRNA would be well suited to serve as a versatile scaffold of macromolecular assembly. Gain of RNP scaffold complexity can occur by increasing the number of proteins in a single macromolecular assembly, for example by recruiting additional proteins to join the complex, and/or by alternative assembly of distinct RNPs on a single ncRNA. (A) A long ncRNA can recruit multiple proteins that are independent or cooperative in their RNP assembly. Multimerization of the ncRNP is possible as well, either by RNA-RNA or protein interactions. In the case of the Drosophila roX RNAs, in addition to providing a scaffold, ncRNA motifs regulate the activity of bound proteins. (B) A single ncRNA can assemble distinct RNPs. In the case of human 7SK RNA, some RNP components are mutually exclusive in their ncRNA association. Distinct 7SK RNPs assemble and disassemble in a dynamic, stress-regulated equilibrium.

RNA scaffolds have distinct, unique structural properties. Constraints on the relative positioning of proteins bridged by RNA can be tight (if the scaffold is rigid), rotationally flexible (if the otherwise rigid scaffold has hinges), or variable over great distance (if the scaffold harbors segments of duplex RNA with many hinges, has extended single-stranded as well as duplex regions, or undergoes conformational dynamics on a biological time scale). Proteins may exchange from the scaffold with different kinetics, through mutually exclusive, independent, or coordinate interactions. While bridging of several different proteins may be the most common function served by RNA scaffolds, structured ncRNAs can also bridge or nucleate the assembly of multiple subunits of the same protein. For example, heat shock RNA 1 appears to function by trimerizing the heat shock transcription factor HSF1 [10], which stimulates HSF1 function as a transcriptional activator.

The use of RNA-scaffolded assemblies for chromatin specialization has evolved independently in numerous biological contexts. The Drosophila roX1 and roX2 RNAs are notable examples of this ncRNA function. RNPs assembled on functionally redundant roX1 or roX2 accomplish dosage compensation in males by increasing gene expression from the singleton X chromosome. The roX RNAs bind and bridge numerous proteins (Figure 2A), including chromatin-modifying enzymes [11]. These RNPs are preferentially recruited to specific chromosome loci and then spread to flanking binding sites, eventually generating a RNP-coated chromosome with a characteristic banding pattern. In addition to their scaffolding role, the roX RNAs either directly or indirectly serve as allosteric activators of RNP enzyme activity in chromatin modification [12]. Although chromatin surrounding a roX RNA expression site preferentially recruits roX RNPs, this feature is not a fundamental requirement for ncRNA function: sites of roX RNA expression and function can be physically unlinked [13]. Mammalian X-chromosome inactivation also involves spreading of ncRNA on chromatin, albeit in a manner more strictly cis-linked to the ncRNA expression locus [2]. These and other examples highlight the theme of ncRNA function in chromatin specification and raise the prospect that long, partially structured ncRNAs are particularly well suited to mediate protein spreading along the length of a chromosome.

The scaffolding function of ncRNAs can be exploited to regulate protein activities in response to changing cellular conditions, as demonstrated by the human 7SK RNA. This abundant nuclear ncRNA forms distinct RNP assemblies that are in dynamic, stress-regulated exchange (Figure 2B). In one RNP form, 7SK RNA negatively regulates the transcription elongation factor P-TEFb by sequestering it in a multisubunit RNP complex [14,15]. In alternate RNP(s), 7SK RNA interacts with a distinct set of proteins to form complexes predicted to have reciprocally related function [16–18]. 7SK RNA has long been thought to be vertebrate-specific, but recent evidence suggests that it has a wider evolutionary distribution [19]. This finding presents an opportunity to investigate the phylogenetic diversification of 7SK RNP composition and biological regulation as a model for understanding structured ncRNA gain of function in the RNP Renaissance.

RNPs in which the ncRNA defines base-pairing specificity

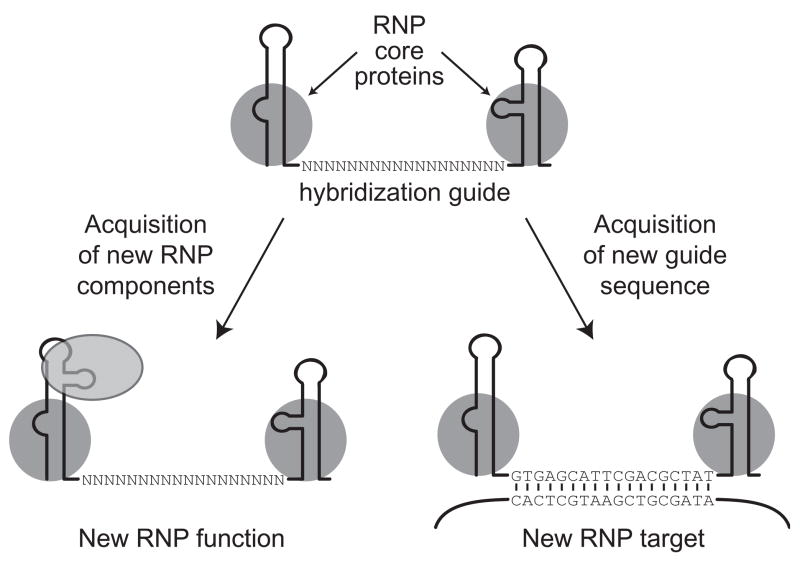

Another role for structured ncRNAs that has been particularly well-characterized is to act as a guide for Watson-Crick base-pairing. Even nascent transcripts can base-pair with a complementary nucleic acid target, if a suitable region of sequence is accessible for hybridization. But the RNP context of a structured ncRNA provides opportunities for improved hybridization specificity and expanded diversity in the biological outcome of hybrid formation. Large families of structured ncRNAs can share a conserved motif architecture that establishes both the specificity of ncRNA assembly with protein partners and the position of the sequence that will function as a hybridization guide (Figure 3). Gene duplication followed by guide-sequence divergence can expand the scope of RNP hybridization targets (Figure 3, right), while sequence changes in other regions of the ncRNA can expand the scope of RNP function in a different manner, giving entirely new biological roles to the ncRNA (Figure 3, left). In these examples, the RNA motifs and protein interaction partners that protect ncRNA biological stability are conserved while additional ncRNA motifs are reshaped through natural selection. Evolutionary adaptation of ncRNA in RNP context thus provides enormous potential for ncRNA-mediated diversification of RNP architecture and function.

Figure 3.

Non-coding RNA function as a specificity guide for Watson-Crick base-pairing. A single-stranded region within a structured ncRNA can be used as a hybridization guide or as a template for polymer synthesis. Within an expanded family of ncRNAs, the hybridization guide sequences of individual members can diverge while retaining the shared motifs essential for assembly of the RNP core (the path at right). New ncRNA motif additions can also occur (the path at left), for example creating a binding site for additional protein(s) that yield a new type of RNP with novel localization, function, and/or regulation.

The small nucleolar (sno) RNAs are representative structured ncRNA families that share motifs for protein interaction but possess divergent guide sequences for target hybridization. SnoRNAs typically guide base and sugar modifications of ribosomal RNA [20]. The shared snoRNP proteins include an enzyme that catalyzes the modification reaction, but its activity and substrate specificity depend on base-pairing of the snoRNA internal guide with the intended RNA target of modification. A subset of snoRNA family members have an additional motif that mediates preferential association with Cajal bodies rather than the nucleolus; these so-called scaRNAs modify small nuclear RNA rather than ribosomal RNA targets [21]. Newly evolved snoRNA family members have also been proposed to regulate adenosine-to-inosine editing and pre-mRNA splicing [22–24]. The snoRNA structural platform has even been appropriated to fulfill functions beyond target hybridization, for example acting within the vertebrate telomerase RNA to direct precursor processing, mature RNA accumulation as RNP, and RNP localization [25].

Beyond the biological exploitation of structured ncRNAs as specificity factors for hybridization to a target nucleic acid, structured ncRNAs can present an internal single-stranded region for use as template. Telomerase RNAs harbor a template for synthesis of the telomeric-repeat DNA at eukaryotic chromosome ends. Across evolution the family of telomerase RNAs has retained the presence of a template and the ability to recruit telomerase reverse transcriptase to copy it, but otherwise family members are highly divergent in RNA and RNP architecture. Divergent telomerase RNA structures adapt the enzyme to particular, organism-specific strategies of active RNP assembly, localization, and regulation [26]. The bacterial 6S RNA demonstrates that ncRNA-templated nucleic acid synthesis can be co-opted as a mechanism to regulate ncRNA function. The 6S RNA binds to a subset of RNA Polymerase holoenzymes to impose promoter-specific transcriptional inhibition in stationary phase [27]. Remarkably, beyond mediating polymerase inhibition by ncRNA-protein interaction, 6S RNA also harbors an internal region that functions as a template for RNA synthesis [28,29]. 6S RNA-directed RNA synthesis allows the polymerase to escape from 6S association during outgrowth from stationary phase.

A final example here illustrates that the templating function of ncRNA is not restricted to directing the synthesis of nucleic acids. The bacterial tmRNA instead provides an mRNA-like template for protein synthesis [30]. A region of tmRNA enters the decoding site of a ribosome stalled in translation and is paired with charged tRNAs to template the addition of a C-terminal peptide tag. The fusion protein is marked as a product of abortive translation and rapidly degraded. Even from the few examples described above, a remarkable breadth in the ability of structured ncRNAs to exploit Watson-Crick base-pairing for recognition of dNTPs, NTPs, or tRNA anticodons is evident.

Functional diversification of RNPs containing ncRNA

The great heterogeneity of possible RNA folds and RNP architectures suggests that a much wider scope of ncRNA function should be possible, beyond the use of modular RNA motifs for protein binding or base-pairing. It is less straightforward to define novel biochemical properties or functions of ncRNA than to uncover new examples from the known ncRNA playbook, particularly given the relatively few methods available for studying ncRNA versus protein folding, interactions, localization, and dynamics in vivo. Many structured ncRNAs with currently unknown roles will eventually be shown to function primarily by bridging associated proteins and/or base-pairing with nucleic acids. However, we suggest that especially in the context of biologically stable, structured ncRNAs already playing these roles, modular RNP architectures present opportunities for ncRNAs to explore additional mechanisms of function.

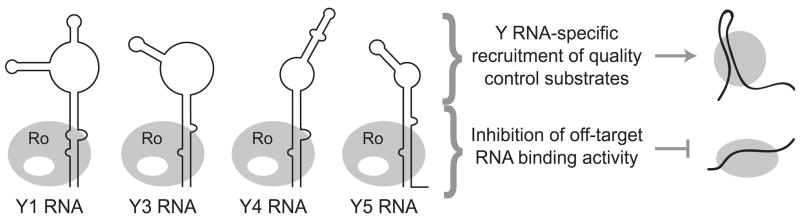

Expansion of the Y RNA family provides a potential example of novel ncRNA gain of function. Many organisms encode a single Y RNA, but higher eukaryotes have diversified a Y RNA family (Figure 4) with at least some members under positive selection for sequence divergence [31,32]. Y RNA biological stability requires association with its partner protein, Ro. Ro does not have enzymatic activity, but enzymes recruited transiently to the Ro platform are thought to mediate degradation of misfolded ncRNAs recognized by Ro as substrates for quality control [33]. A bound Y RNA is predicted to occlude the Ro surface required for high-affinity binding to misfolded RNA [34]. Thus, the ancestral Y RNA could have been a negative regulator of Ro association with potential ncRNA quality control substrates [33].

Figure 4.

Non-coding RNA function as a specificity factor for RNP-RNP interaction. Gain of function by ncRNA extends beyond its roles as a reaction catalyst, scaffold, or guide for base-pairing. One potential example of this less readily categorized gain of function can be illustrated by consideration of the human family of Y RNAs. Each Y RNA has a conserved motif required for biological stability through assembly with the protein Ro. Y RNA-Ro interaction may serve the general role of reducing Ro interaction with off-target ncRNAs. However, the central region of the Y RNA differs in sequence and structure across family members. This region, potentially in combination with a nearby surface of Ro, could mediate an individual ncRNA-specific gain of function by recruiting different RNP substrates for quality control surveillance.

Y RNA family members share the motifs necessary for Ro binding, but they are highly divergent in other sequence features (Figure 4). Like snoRNA families, the Y RNA family could have gained function by beneficial expansion of the scope of targets recruited to the shared protein platform. Unlike snoRNAs, however, Y RNAs lack single-stranded regions of conserved length and positioning that would be candidate motifs for mediating hybridization to RNA targets. Instead, the family of Y RNAs may specialize Ro function by recruiting particular misfolded ncRNA targets in their endogenous RNP context, via a RNP-RNP mode of recognition rather than simple RNA-RNA base-pairing [35]. Motifs specific to an individual Y RNA could be subject to ongoing selection for improved recognition of the evolving misfolded ncRNA targets of quality control surveillance.

Much remains to be understood about Y RNA and Y RNP function. Independent of the eventual roles defined for individual members of the Y RNA family, it will be interesting to uncover how expansion of this ncRNA family in shared RNP protein context led to gain of function compared to how gain of function was accomplished by assembly of a single ncRNA with alternate RNP protein partners, as discussed above for human 7SK RNA.

Conclusions

Knowledge about ncRNA has reached only the tip of an iceberg [36], but already the diversity of ncRNA functions resists easy categorization. Beyond elucidating additional details of specific modes of ncRNA function, further investigation will expand our knowledge of the scope of ncRNA roles in the RNP Renaissance and mechanisms by which ncRNA evolution generates functional complexity. These efforts will be facilitated by methods that can assess ncRNA localization and interactions in vivo. Innovative use of modified nucleic acids as hybridization probes greatly advanced the study of ncRNPs [37]. New tag-based ncRNA localization and RNP affinity purification methods [16,38,39] should enable a broader scope of analysis, including integration of ncRNAs into the current protein-centric versions of cellular interaction networks.

Are there discernable themes for the biological roles of structured ncRNAs arising in this modern-day RNP Renaissance? As a final point of speculation, we note that many structured ncRNAs function in a manner linked to cellular stress. Several independently evolved ncRNAs have been shown to be stabilized by stress and to act under these conditions to inhibit transcription [27,40–42]. Even ancestral ncRNAs may have gained roles in stress response: for example, under stress, mature tRNAs are processed by cleavage in the anticodon loop to generate transiently accumulating tRNA halves [43]. These and other examples of stress-associated ncRNAs could have been preferentially characterized due to their abundance or readily discernable regulation; in eukaryotes, these ncRNAs are often produced by RNA Polymerase III, facilitating their detection using bioinformatic analysis [44]. However, there may be a robust biological rationale for evolution of ncRNA roles during stress conditions. The minimal lag and low energetic cost of RNA synthesis relative to protein synthesis would be advantageous for a stress response, and, in fact, many forms of cellular stress disfavor a response requiring protein synthesis due to stress-induced translational repression. The repeating theme of roles for structured ncRNAs in cellular stress responses, along with a growing appreciation of extraordinary ncRNA diversity, suggest that there are important and widespread implications of the RNP Renaissance.

Acknowledgments

We thank Harry Noller for inspiration with the term RNP Renaissance and Suzanne Lee for discussion. Funding for non-coding RNA research in the Collins lab has been provided by the Cancer Research Committee of California and the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

J. Robert Hogg, JRH: Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, NY 10032; jh2721@columbia.edu.

Kathleen Collins, KC: Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720-3200; kcollins@berkeley.edu.

References

- 1.Amaral PP, Dinger ME, Mercer TR, Mattick JS. The eukaryotic genome as an RNA machine. Science. 2008;319:1787–1789. doi: 10.1126/science.1155472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prasanth KV, Spector DL. Eukaryotic regulatory RNAs: an answer to the ‘genome complexity’ conundrum. Genes Dev. 2007;21:11–42. doi: 10.1101/gad.1484207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pauler FM, Koerner MV, Barlow DP. Silencing by imprinted noncoding RNAs: is transcription the answer? Trends Genet. 2007;23:284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang X, Arai S, Song X, Reichart D, Du K, Pascual G, Tempst P, Rosenfeld MG, Glass CK, Kurokawa R. Induced ncRNAs allosterically modify RNA-binding proteins in cis to inhibit transcription. Nature. 2008;454:126–130. doi: 10.1038/nature06992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farazi TA, Juranek SA, Tuschl T. The growing catalog of small RNAs and their association with distinct Argonaute/Piwi family members. Development. 2008;135:1201–1214. doi: 10.1242/dev.005629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fedor MJ, Williamson JR. The catalytic diversity of RNAs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:399–412. doi: 10.1038/nrm1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noller HF. The driving force for molecular evolution of translation. RNA. 2004;10:1833–1837. doi: 10.1261/rna.7142404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strobel SA, Cochrane JC. RNA catalysis: ribozymes, ribosomes, and riboswitches. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2007;11:636–643. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brosius J. Echoes from the past--are we still in an RNP world? Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;110:8–24. doi: 10.1159/000084934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10**.Shamovsky I, Ivannikov M, Kandel ES, Gershon D, Nudler E. RNA-mediated response to heat shock in mammalian cells. Nature. 2006;440:556–560. doi: 10.1038/nature04518. The authors discover a missing component of the pathway for changes in transcription following heat shock: a ncRNA termed heat shock RNA 1. Among other findings, they show that this novel ncRNA is required for heat-shock induced higher-order assembly and functional activation of the transcription factor HSF1. The exact role of the ncRNA remains uncertain; its associations with protein partners remain to be fully defined. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deng X, Meller VH. Non-coding RNA in fly dosage compensation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:526–532. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park SW, Kuroda MI, Park Y. Regulation of histone H4 Lys16 acetylation by predicted alternative secondary structures in roX noncoding RNAs. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4952–4962. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00219-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meller VH, Rattner BP. The roX genes encode redundant male-specific lethal transcripts required for targeting of the MSL complex. EMBO J. 2002;21:1084–1091. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen VT, Kiss T, Michels AA, Bensaude O. 7SK small nuclear RNA binds to and inhibits the activity of CDK9/cyclin T complexes. Nature. 2001;414:322–325. doi: 10.1038/35104581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Z, Zhu Q, Luo K, Zhou Q. The 7SK small nuclear RNA inhibits the CDK9/cyclin T1 kinase to control transcription. Nature. 2001;414:317–322. doi: 10.1038/35104575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16**.Hogg JR, Collins K. RNA-based affinity purification reveals 7SK RNPs with distinct composition and regulation. RNA. 2007;13:868–880. doi: 10.1261/rna.565207. The authors introduce an entirely RNA-based method for affinity purification of RNPs assembled in vivo at endogenous level. The RNA affinity in Tandem (RAT) approach exploits two small RNA hairpin tags for sequential steps of RNP affinity purification to homogeneity. In this report, RAT is used for isolation of RNPs assembled on several human ncRNAs including the mixed population of alternative 7SK RNPs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Herreweghe E, Egloff S, Goiffon I, Jády BE, Froment C, Monsarrat B, Kiss T. Dynamic remodelling of human 7SK snRNP controls the nuclear level of active P-TEFb. EMBO J. 2007;26:3570–3580. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barrandon C, Bonnet F, Nguyen VT, Labas V, Bensaude O. The transcription-dependent dissociation of P-TEFb-HEXIM1-7SK RNA relies upon formation of hnRNP-7SK RNA complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:6996–7006. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00975-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gruber AR, Kilgus C, Mosig A, Hofacker IL, Hennig W, Stadler PF. Arthropod 7SK RNA. Mol Biol Evol. 2008 doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matera AG, Terns RM, Terns MP. Non-coding RNAs: lessons from the small nuclear and small nucleolar RNAs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:209–220. doi: 10.1038/nrm2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiss T. Biogenesis of small nuclear RNPs. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5949–5951. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vitali P, Basyuk E, Le Meur E, Bertrand E, Muscatelli F, Cavaillé J, Huttenhofer A. ADAR2-mediated editing of RNA substrates in the nucleolus is inhibited by C/D small nucleolar RNAs. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:745–753. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200411129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kishore S, Stamm S. The snoRNA HBII-52 regulates alternative splicing of the serotonin receptor 2C. Science. 2006;311:230–232. doi: 10.1126/science.1118265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogelj B. Brain-specific small nucleolar RNAs. J Mol Neurosci. 2006;28:103–109. doi: 10.1385/JMN:28:2:103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins K. Physiological assembly and activity of human telomerase complexes. Mech Ageing Dev. 2008;129:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins K. The biogenesis and regulation of telomerase holoenzymes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:484–494. doi: 10.1038/nrm1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wassarman KM. 6S RNA: a regulator of transcription. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65:1425–1431. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wassarman KM, Saecker RM. Synthesis-mediated release of a small RNA inhibitor of RNA polymerase. Science. 2006;314:1601–1603. doi: 10.1126/science.1134830. With Ref. 29, this study reveals yet another fascinating chapter in the story of 6S RNA function. **The authors show that a region within 6S RNA is used as template by the associated RNA polymerase holoenzyme during escape of the polymerase from ncRNA-mediated inhibition. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29**.Gildehaus N, Neusser T, Wurm R, Wagner R. Studies on the function of the riboregulator 6S RNA from E. coli: RNA polymerase binding, inhibition of in vitro transcription and synthesis of RNA-directed de novo transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:1885–1896. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm085. See annotation of Ref. 28 above; this study also demonstrates that a region within 6S RNA is used as a template by RNA polymerase. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore SD, Sauer RT. The tmRNA system for translational surveillance and ribosome rescue. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:101–124. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maraia R, Sakulich AL, Brinkmann E, Green ED. Gene encoding human Ro-associated autoantigen Y5 RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:3552–3559. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.18.3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perreault J, Perreault JP, Boire G. Ro associated Y RNAs in metazoans: Evolution and diversification. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1678–1689. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reinisch KM, Wolin SL. Emerging themes in non-coding RNA quality control. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stein AJ, Fuchs G, Fu C, Wolin SL, Reinisch KM. Structural insights into RNA quality control: the Ro autoantigen binds misfolded RNAs via its central cavity. Cell. 2005;121:529–539. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35**.Hogg JR, Collins K. Human Y5 RNA specializes a Ro ribonucleoprotein for 5S ribosomal RNA quality control. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3067–3072. doi: 10.1101/gad.1603907. The authors use entirely RNA-based RNP affinity purification to address the functional significance of evolutionary diversification of a family of human Y RNAs. They show that individual Y RNAs specialize the ncRNA and protein interaction partners of a Ro RNP in vivo. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nilsen TW. RNA 1997–2007: a remarkable decade of discovery. Mol Cell. 2007;28:715–720. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamond AI, Sproat BS. Antisense oligonucleotides made of 2′-O-alkylRNA: their properties and applications in RNA biochemistry. FEBS Lett. 1993;325:123–127. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81427-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez AJ, Condeelis J, Singer RH, Dictenberg JB. Imaging mRNA movement from transcription sites to translation sites. Seminars Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keryer-Bibens C, Barreau C, Osborne HB. Tethering of proteins to RNAs by bacteriophage proteins. Biol Cell. 2008;100:125–138. doi: 10.1042/BC20070067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40**.Mariner PD, Walters RD, Espinoza CA, Drullinger LF, Wagner SD, Kugel JF, Goodrich JA. Human Alu RNA is a modular transacting repressor of mRNA transcription during heat shock. Mol Cell. 2008;29:499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.013. The authors demonstrate a role for transcripts produced from repetitive human Alu elements in the inhibition of RNA Polymerase II transcription following heat shock. Alu RNAs thus join mouse B2 and numerous other ncRNAs as regulators of the response to cellular stress. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allen TA, Von Kaenel S, Goodrich JA, Kugel JF. The SINE-encoded mouse B2 RNA represses mRNA transcription in response to heat shock. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:816–821. doi: 10.1038/nsmb813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Espinoza CA, Allen TA, Hieb AR, Kugel JF, Goodrich JA. B2 RNA binds directly to RNA polymerase II to repress transcript synthesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:822–829. doi: 10.1038/nsmb812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee SR, Collins K. Starvation-induced cleavage of the tRNA anticodon loop in Tetrahymena thermophila. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42744–42749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510356200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dieci G, Fiorino G, Castelnuovo M, Teichmann M, Pagano A. The expanding RNA polymerase III transcriptome. Trends Genet. 2007;23:614–622. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]