Abstract

Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) infection of the small bowel is very rare. The disease course is more severe than that of C. difficile colitis, and the mortality is high. We present a case of C. difficile enteritis in a patient with ileal pouch-anal anastamosis (IPAA), and review previous case reports in order to better characterize this unusual condition.

1. INTRODUCTION

C. difficile infection is associated with antibiotic-induced pseudomembranous colitis. This infection is usually thought to be restricted to the colon. Isolated small bowel C. difficile enteritis is rare and can manifest in the absence of a colon.

C. difficile has been shown to colonize small bowel mucosa in about 3% of the population, which then serves as a reservoir for infection [1]. Most carriers are asymptomatic. Altered intestinal anatomy and antibiotic use have been implicated in triggering symptomatic infection. Fecal flora in the small bowel of patients who had undergone a colectomy is altered to resemble that of the colon. Morphological changes (colonic-type metaplasia with partial villous atrophy) which occur in the mucosa of an ileal pouch secondary to altered fecal flow may predispose to infection [2]. These factors may increase small bowel colonization by C. difficile. Alteration of fecal flora by antibiotic can trigger symptomatic infection.

The clinical presentation of C. difficile colitis is typically mild, occasionally progressing to fulminant colitis. The disease course is more fulminant when small bowel is affected, with reported mortality ranging from 60–83% [3]. We report a case of fulminant C. difficile enteritis in a patient with ileal pouch-anal anastamosis (IPAA), and review previous reports of this unusual condition.

2. REPORT OF A CASE

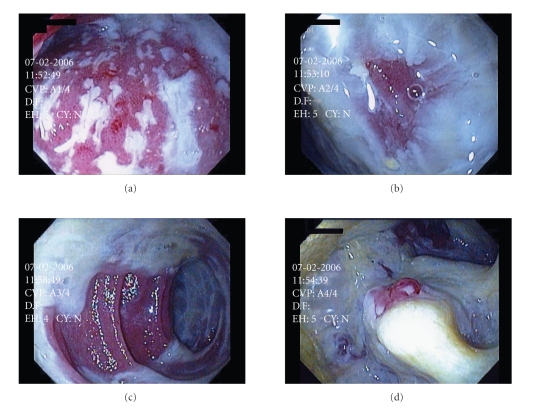

A 42-year-old man underwent proctocolectomy with IPAA and ileostomy for medically refractory ulcerative colitis (UC). The patient returned for ileostomy takedown six months later. His hospital course was complicated by a urinary tract infection, which was treated with ciprofloxacin. The patient was discharged tolerating a regular diet with good bowel function. The patient returned 10 days later complaining of a three-day history of nausea, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Patient was febrile (38.3°C), tachycardic (138), with elevated white blood cell count (17.000), creatinine (2.5), and platelet count (1450). CT scan of the abdomen showed dilated small bowel with fluid and air to the ileoanal anastomosis. Blood, urine, and stool cultures were sent, and empiric intravenous piperacillin/ tazobactam and vancomycin were started. However, the patient became progressively more septic and required vasopressors for blood pressure support. Unexpectedly, C. difficile enzyme immunoassay (EIA) came back positive for toxins A and B, and the patient started on oral vancomycin and metronidazole. Flexible endoscopy was performed and revealed copious amounts of mucus with adherent pseudomembranes throughout the pouch and distal small bowel (Figure 1). Over the next few days, the patient remained in critical condition, but then slowly stabilized. Vasopressors were weaned; WBC and creatinine came down to normal limits. Within 7 days of admission, patient was restarted on a diet and was ultimately discharged after a 12-day hospitalization. At one year follow up, the patient still occasionally has frequent bowel movements, but his stool cultures have remained negative for C. difficile toxins.

Figure 1.

Flexible endoscopy of pelvic pouch demonstrating copious amounts of mucus with adherent pseudomembranes throughout the pouch and distal small bowel, consistent with C. difficile infection.

3. DISCUSSION

PubMed literature search for C. difficile enteritis was performed and revealed 26 cases from 1980–2008 (Table 1) [3–22]. There was significant age variability, with a range of 18 to 83 years of age (mean 50.3). Sixteen of the 26 patients had inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), thirteen patients had ulcerative colitis, and three had Crohn's disease. Ten patients had total colectomies and six underwent IPAA. All but three patients had altered intestinal anatomy. Twenty four patients had recent hospitalization and/or operation as well as recent antibiotic use. Thirteen patients were septic and required ICU admission. In all 26 cases, the stool assays were positive for C. difficile toxin. Diagnosis of small bowel involvement was made based on biopsy, pathology, or autopsy results. Only seven patients were evaluated endoscopically. Four underwent flexible sigmoidoscopy, and three of those had pseudomembranes. Of the patients with IPAA, only two were examined endoscopically and no pseudomembranes were visualized. One patient had an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) which demonstrated pseudomembranes in the duodenum. Treatment in all but two patients included metronidazole or vancomycin, or a combination of both. Two patients were resistant to metronidazole. Fourteen of the 26 underwent operative intervention. Mortality rate was 35%.

Table 1.

Previously reported cases of small bowel C. difficile.

| Author | Age | IBD | Intestinal operation | Recent hospitalization/operation | Recent Abx | ICU/Sepsis | OR | Endoscopy | Treatment | Death | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LaMont and Trnka [4] 1980 | 23 | Crohn's | Partial colectomy | No | No | No | No | EGD—pseudomembranes in duodenum | Vancomycin | No | |

| 2 | Shortland et al. [5] 1983 | 70 | No | Ileal conduit | Yes | Yes | — | No | Sigmoidoscopy—pseudomembranes | Vancomycin | Yes | |

| 3 | Testore et al. [6] 1984 | 69 | No | APR | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | — | — | Yes | |

| 4 | Miller et al. [7] 1989 | 18 | No | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Flexible sigmoidoscopy—inflammation; no pseudomembranes | Streptomycin | No | 2 jejunal perforations |

| 5 | Kuntz et al. [8] 1993 | 53 | UC | TAC | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | Vancomycin, flagyl | Yes | Intramural gas on CT |

| 6 | Tsutaoka et al. [9] 1994 | 66 | No | Rt hemicolectomy + APR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | Vancomycin, flagyl | Yes | |

| 7 | Yee et al. [10] 1996 | 71 | No | TAC | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | Flagyl | Yes | |

| 8 | Kralovich et al. [11] 1997 | 65 | No | Jejunal-ileal bypass | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Flexible sigmoidoscopy—pseudomembranes | Vancomycin, flagyl | Yes | |

| 9 | Vesoulis et al. [12] 2000 | 56 | Crohn's | TPC | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | Flagyl | No | |

| 10 | Freiler et al. [13] 2001 | 26 | UC | TAC | Yes | Yes | No | No | — | Flagyl | No | |

| 11 | Jacobs et al. [14] 2001 | 83 | — | — | Yes | Yes | — | Yes | — | — | No | |

| 12 | Tjandra et al. [15] 2001 | 60 | No | Sigmoid colectomy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Flexible sigmoidoscopy—pseudomembranes | Vancomycin, flagyl | Yes | |

| 13 | Mann et al. [16] 2003 | 35 | UC | IPAA | No | No | No | No | Flexible endoscopy—inflammed, ulcerated mucosa | Vancomycin; resistant to flagyl | No | Chronic pouchitis |

| 14 | Hayetian et al. [17] 2006 | 80 | No | LAR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | Flagyl | Yes | Ileal perforation |

| 15 | Hayetian et al. [17] 2006 | 83 | No | None | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | Vancomycin, flagyl | No | Ileal perforation |

| 16 | Kim et al. [18] 2007 | 65 | Crohn's | TPC | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | — | Flagyl | Yes | |

| 17 | Lundeen et al. [3] (6 patients) 2007 | Mean 35.3 | UC (6 patients) | 3 IPAA 3 TAC | 6/6 | 6/6 | 1/6 | 1/6 | — | Vancomycin, flagyl | No | |

| 18 | Wood et al. [19] 2008 | 48 | UC | IPAA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Flexible endoscopy—normal pouch | Flagyl | No | |

| 19 | Follmar et al. [20] 2008 | 49 | UC | IPAA | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | — | Vancomycin, resistant to flagyl | No | Or–mesh removal |

| 20 | Fleming et al. [21] 2008 | 54 | UC | TAC | Yes | Yes | ? | No | — | Flagyl, vancomycin, rifampin | No | |

| 21 | Yafi et al. [22] 2008 | 21 | UC | TAC | Yes | Yes | ? | Yes | — | Vancomycin | No | Pelvic abscess |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total | 50.3 | 16/26 | 23/26 | 24/26 | 24/26 | 13/26 | 14/26 | 7/26 | 21/26 | 9/26 | ||

Our patient was similar to the previously reported cases of C. difficile enteritis in that he had a history of IBD, recent surgery, and antibiotic use. He required ICU admission secondary to sepsis, but he did not require operative intervention. Unlike any of the previously reported cases, our patient's pouch endoscopy revealed pseudomembranes, facilitating timely intervention and his ultimate recovery.

C. difficile enteritis appears to have a fulminant course, with high risk of sepsis, need for operation, and mortality. It is unclear why the disease course is more severe than in colitis. Increased small bowel permeability is one potential explanation. Delay in diagnosis and treatment may play a role as well.

The clinical presentation can be similar for both enteritis and colitis. Symptoms include diarrhea, dehydration, and increased ileostomy output. Unlike colitis, enteritis more commonly presents with systemic manifestations such as fever, hypotension, leukocytosis and thrombocytosis [3], and occasionally with peritonitis or bowel perforation [7, 17].

C. difficile enteritis may be difficult to differentiate from other inflammatory processes, and requires high degree of suspicion to make the diagnosis. C. difficile has also been implicated as a cause of chronic pouchitis in patients with IPAA [16], and should be suspected in this setting. Given the higher risk that IBD patients may have for developing C. difficile enteritis, it is important to be able to differentiate it from an exacerbation of IBD. Diagnosis is made by identifying C. difficile toxin A or B in the stool. Similarly, endoscopy should be utilized in patients with suspected small bowel involvement even with history of prior colectomy. This may facilitate differentiation between Crohn's enteritis, pouchitis, and C. difficile enteritis.

As with our patient, most cases will respond to treatment with metronidazole or vancomycin. However, more virulent and resistant strains have been reported [23]. Some patients will need emergent surgical resection of any perforated or gangrenous bowel if they fail to respond to medical treatment.

C. difficile enteritis is emerging with increased frequency and can have devastating results. Patients with IBD and prior colectomy are at increased risk. Prompt identification of the organism via stool culture and endoscopy may result in more favorable outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There are no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to declare. The manuscript has been seen and approved by all authors and the material is previously unpublished. Author contributions are as follows: E. Boland presented a study design and the manuscript preparation; J. S. Thompson presented a study design and a critical revision of the manuscript.

NOMENCLATURE

- APR:

Abdominoperineal resection

- TAC:

Total abdominal colectomy

- TPC:

Total proctocolectomy

- IPAA:

Ileal pouch-anal anastamosis.

References

- 1.Testore GP, Nardi F, Babudieri S, Giuliano M, Di Rosa R, Panichi G. Isolation of Clostridium difficile from human jejunum: identification of a reservoir for disease? Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1986;39(8):861–862. doi: 10.1136/jcp.39.8.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apel R, Cohen Z, Andrews CW, Jr., McLeod R, Steinhart H, Odze RD. Prospective evaluation of early morphological changes in pelvic ileal pouches. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(2):435–443. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lundeen SJ, Otterson MF, Binion DG, Carman ET, Peppard WJ. Clostridium difficile enteritis: an early postoperative complication in inflammatory bowel disease patients after colectomy. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2007;11(2):138–142. doi: 10.1007/s11605-006-0022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LaMont JT, Trnka YM. Therapeutic implications of Clostridium difficile toxin during relapse of chronic inflammatory bowel disease. The Lancet. 1980;1(8165):381–383. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)90939-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shortland JR, Spencer RC, Williams JL. Pseudomembranous colitis associated with changes in an ileal conduit. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1983;36(10):1184–1187. doi: 10.1136/jcp.36.10.1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Testore GP, Pantosti A, Panichi G, et al. Pseudomembranous enteritis associated with Clostridium difficile . Italian Journal of Gastroenterology. 1984;16(3):229–230. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller DL, Sedlack JD, Holt RW. Perforation complicating rifampin-associated pseudomembranous enteritis. Archives of Surgery. 1989;124(9):p. 1082. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1989.01410090092020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuntz DP, Shortsleeve MJ, Kantrowitz PA, Gauvin GP. Clostridium difficile enteritis. A cause of intramural gas. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 1993;38(10):1942–1944. doi: 10.1007/BF01296124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsutaoka B, Hansen J, Johnson D, Holodniy M. Antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous enteritis due to Clostridium difficile . Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1994;18(6):982–984. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.6.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yee HF, Jr., Brown RS, Jr., Ostroff JW. Fatal Clostridium difficile enteritis after total abdominal colectomy. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 1996;22(1):45–47. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199601000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kralovich KA, Sacksner J, Karmy-Jones RA, Eggenberger JC. Pseudomembranous colitis with associated fulminant ileitis in the defunctionalized limb of a jejunal-ileal bypass: report of a case. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 1997;40(5):622–624. doi: 10.1007/BF02055391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vesoulis Z, Williams G, Matthews B. Pseudomembranous enteritis after proctocolectomy: report of a case. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2000;43(4):551–554. doi: 10.1007/BF02237205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freiler JF, Durning SJ, Ender PT. Clostridium difficile small bowel enteritis occurring after total colectomy. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2001;33(8):1429–1431. doi: 10.1086/322675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs A, Barnard K, Fishel R, Gradon JD. Extracolonic manifestations of Clostridium difficile infections: presentation of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 2001;80(2):88–101. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200103000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tjandra JJ, Street A, Thomas RJ, Gibson R, Eng P, Cade J. Fatal Clostridium difficile infection of the small bowel after complex colorectal surgery. ANZ Journal of Surgery. 2001;71(8):500–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.2001.02083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mann SD, Pitt J, Springall RG, Thillainayagam AV. Clostridium difficile infection—an unusual cause of refractory pouchitis: report of a case. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2003;46(2):267–270. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6533-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayetian FD, Read TE, Brozovich M, Garvin RP, Caushaj PF. Ileal perforation secondary to Clostridium difficile enteritis: report of 2 cases. Archives of Surgery. 2006;141(1):97–99. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim KA, Wry P, Hughes E, Jr., Butcher J, Barbot D. Clostridium difficile small-bowel enteritis after total proctocolectomy: a rare but fatal, easily missed diagnosis. Report of a case. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2007;50(6):920–923. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0784-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood MJ, Hyman N, Hebert JC, Blaszyk H. Catastrophic Clostridium difficile enteritis in a pelvic pouch patient: report of a case. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2008;12(2):350–352. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0440-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Follmar KE, Condron SA, Turner II, Nathan JD, Ludwig KA. Treatment of metronidazole-refractory Clostridium difficile enteritis with vancomycin. Surgical Infections. 2008;9(2):195–200. doi: 10.1089/sur.2006.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleming F, Khursigara N, O'Connell N, Darby S, Waldron D. Fulminant small bowel enteritis: a rare complication of Clostridium difficile-associated disease. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20758. to appear in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yafi FA, Selvasekar CR, Cima RR. Clostridium difficile enteritis following total colectomy. Techniques in Coloproctology. 2008;12(1):73–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warny M, Pepin J, Fang A, et al. Toxin production by an emerging strain of Clostridium difficile associated with outbreaks of severe disease in North America and Europe. The Lancet. 2005;366(9491):1079–1084. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67420-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]