Abstract

Background

No reduction in either coronary mortality or sudden cardiac death (SCD) has been demonstrated in overviews of randomized trials of treatment of hypertension with diuretics.

Methods

An overview was conducted of coronary mortality and SCD in randomized controlled antihypertensive trials in which an epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) inhibitor/ hydrochlorthiazide (HCTZ) combination was used. Secondarily, an analogous overview in which thiazide diuretic was used alone was performed. Randomized trials that used an ENaC inhibitor/ HCTZ combination (or, alternatively, thiazide diuretic alone) were identified from previous meta-analyses, searches of PubMed, search of the Cochrane Clinical Trials database, and review of publications that addressed the consequences of treating hypertension. Trials in which participants were randomized to either an ENaC inhibitor combined with a thiazide diuretic (or to a thiazide diuretic alone) or to control treatment for at least one year and in which coronary mortality was reported were included. Numbers of events in individual trials were abstracted independently by 2 authors.

Results

Significant reductions in both coronary mortality and SCD were observed in the overview of trials in which elderly patients received an ENaC inhibitor/ HCTZ combination. The odds ratio (OR) for coronary mortality was 0.59 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.44, 0.78) and for SCD was 0.60 (95% CI 0.38, 0.94). In contrast, an overview of the trials using thiazide diuretics alone showed no significant reductions of either coronary mortality (OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.81, 1.09) or SCD (OR 1.27; 95% CI 0.93, 1.75).

Conclusions

Use of an ENaC inhibitor combined with HCTZ for treatment of hypertension in the elderly results in favorable effects on coronary mortality and SCD.

INTRODUCTION

Diuretic drugs are central to the treatment of hypertension. It is therefore appropriate to consider ways in which their benefit can be optimized. Placebo controlled trials have demonstrated that diuretics are highly efficacious in reducing cerebrovascular accidents and yield a smaller but significant reduction in non-fatal myocardial infarction. However, no significant reduction in coronary deaths has been demonstrated even when the data from all of these trials have been combined by meta-analysis 1.

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) constitutes a major subset of coronary deaths in hypertensive patients, and the wasting of potassium induced by diuretics has focused attention on SCD during diuretic therapy. Two case-controlled observational studies have provided evidence that the use of potassium-sparing agents in combination with thiazide diuretics was associated with a reduction in primary cardiac arrest 2, 3. Moreover, potassium wasting enhances the development of experimental ischemic ventricular fibrillation 4–6. The concerted evidence suggesting that SCD could be an adverse effect of thiazides led us to conduct an overview of coronary mortality and SCD in randomized controlled trials in which hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) was combined with an epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) inhibitor 7–9. Included in the overview are previously unpublished data on sudden cardiac death from 2 of these trials.

As a secondary objective, these same endpoints were assessed in an overview of 16 trials that employed a thiazide without mandated use of a potassium-sparing drug.

METHOD

Selection of the trials

Randomized controlled clinical trials of diuretic-based antihypertensive treatment that evaluated coronary mortality were sought from the previous and repeated meta-analyses dating back to 1990 that had identified these outcome trials 1, 10–13, from searches of PUBMED from 1985, from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (2006, Issue 2) and from review of publications addressing the consequences of treating hypertension. Randomized trials that compared treatment of at least one year duration with placebo, or in one instance with “usual care” 14 were selected. Trials that used concomitant interventions on other risk factors in addition to thiazide diuretics, such as the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial, were excluded because any inference regarding the effect of thiazides is confounded by the concomitant interventions 15.

For the overview of ENaC inhibitor/HCTZ combination therapy, trials in which the protocol designated that an ENaC inhibitor was to be used routinely in combination with a thiazide diuretic were selected. Conversely, those not meeting this criterion were included in the overview of trials not mandating the use of potassium-sparing diuretics. Numbers of total coronary deaths and SCDs in the individual trials were abstracted independently by two authors (PRH and JAO).

Trials mandating use of an ENaC inhibitor

The primary objective of this evaluation is an overview of the outcomes of coronary mortality and sudden cardiac death in the trials of antihypertensive therapy in which the protocol designated that an ENaC inhibitor was to be used routinely in combination with a thiazide diuretic. Three such trials were identified (Table 1), which evaluated a total of 5761 patients for 32,657 patient years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the trials mandating the use of an ENaC inhibitor in combination with a thiazide.

| Active Treatment | Control Treatment | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | ENaC Inhibitor | HCTZ Daily dose | Mean Age | Fatal CHD | SCD | No. Rand | Fatal CHD | SCD | No. Rand |

| EWPHE | Triamterene | 25mg | 72 | 29 | 6 | 416 | 47 | 7 | 424 |

| MRC-Older adults | Amiloride | 25mg | 70 | 33 | 17 | 1081 | 110 | 54 | 2213 |

| STOP-HTN | Amiloride | 25mg | 76 | 10 | 4 | 812 | 20 | 12 | 815 |

| Total: All trials | 72 | 27 | 2309 | 177 | 73 | 3452 | |||

Abbreviations: HCTZ = hydrochlorothiazide; CHD = coronary heart disease; No. Rand. = number randomized

EWPHE = European Working Party on Hypertension in the Elderly trial

MRC-Older Adults = Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults

STOP-HTN = Swedish Trial on Old Patients with Hypertension

The European Working Party on Hypertension in the Elderly (EWPHE) trial8 conducted from 1972–1984 enrolled patients over age 60 with diastolic blood pressure (BP) on placebo in the range of 90–119 mm Hg and a systolic pressure in the range of 160–239. Initial treatment was daily administration of hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg daily together with triamterene 50 mg. This dose could be doubled, and subsequently methyldopa 250–1000 mg could be added if required for BP control.

The Swedish Trial on Old Patients with Hypertension (STOP-Hypertension)9 was conducted from 1985–1991 in patients ages 70–84 years old with systolic BP 180–230 mm Hg and diastolic BP exceeding 90, or a diastolic 105–120 irrespective of systolic pressure. Patients were randomized to drug treatment or placebo, and the individual centers chose the initial treatment from 4 options: hydrochlorothiazide 25mg plus amiloride 2.5 mg, atenolol 50 mg, metoprolol 100 mg, or pindolol 5 mg daily. If BP was not controlled on the initial regimen, the diuretic combination was added to the β-adrenoreceptor antagonist, and vice versa. Of the 765 patients completing the treatment arm, the diuretic combination had been administered to 627 (82%); in 246 it was the initial treatment and in 381 it was added if blood pressure was not controlled within 2 months with a β-adrenoreceptor antagonist alone (Ekbom, et al., 1992).

The Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults (MRC-Older Adults)7 conducted from 1982–1990 enrolled patients aged 65–74 with systolic BP of 160–209 mm Hg and diastolic BP less than 115. The treatment arm that employed the diuretic combination as initial therapy was included in this overview together with the corresponding placebo arm; this trial also evaluated a β-adrenoreceptor antagonist in a separate arm. A substudy conducted during the early phase of recruitment for the trial compared the antihypertensive effects of 5mg amiloride plus 50 mg hydrochlorothiazide with those of 2.5 mg amiloride plus 25 mg hydrochlorothiazide. As the higher dose did not lower blood pressure to a greater extent than the lower dose, all patients were placed on 2.5 mg amiloride/25 mg hydrochlorothiazide beginning midway of the recruitment phase of the trial. If BP was not controlled on this treatment, nifedipine was added.

Analysis of sudden cardiac death

Data on SCD were published in the report of the STOP-Hypertension trial. The unpublished data on SCD in the EWPHE trial8 were provided for this overview. Data on the SCD endpoint in the largest of these trials, MRC-Older Adults, had been collected but had not been analyzed. Occurrence of a fatal coronary event was the primary endpoint of this trial, and data collection was organized to provide a basis for this diagnosis that included SCD. Accordingly, a blinded analysis of sudden cardiac death was performed on summaries of the fatal event that included notes from the general practitioner, hospital inpatient and outpatient notes, electrocardiographic recordings, necropsy findings, and death certificate. The blinded analysis of sudden cardiac deaths in this trial utilizing prespecified criteria was conducted by two of the authors (KTM and JNR) to determine those attributed to SCD.

Prespecified criteria for determining sudden cardiac death

SCD was defined as either a sudden, pulseless condition or collapse that is consistent with a ventricular tachyarrhythmia and is fatal, or a cardiac arrest with resuscitation in which both cardiopulmonary resuscitation and defibrillation were required. The event was characterized as SCD if it was a witnessed sudden collapse or arrest; this could have occurred without preceding symptoms or could have immediately followed lightheadedness, palpitations, dyspnea or the signs or symptoms of myocardial ischemia if these occurred in the absence of shock or Class IV congestive heart failure, and could also have been associated with documented ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation at the start of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. An unwitnessed death was characterized as SCD if it occurred in a person previously known to be well, including those occurring during sleep. Deaths were not considered to be SCD where documentation or autopsy evidence suggested a noncardiac cause as the etiology of death or if there had been a different cardiac cause such as bradycardia or heart failure. In the presence of severe congestive heart failure, death was judged not to be due to arrhythmia if death from cardiac failure appeared probable within four months of the fatal episode.

Trials not mandating use of any potassium-sparing drug

Sixteen trials were identified that compared placebo, or in one instance “usual care”, with thiazide diuretics that were used without protocol requirement for a potassium-sparing agent (Table 2). In fourteen of these, the thiazide was administered as the initial drug. In the Coope Trial19, atenolol was employed as initial therapy, and 60% of the patients received bendrofluazide 5 mg as the second step in therapy. In the Barraclough trial24, 53% received the thiazide initially and with its additional use as supplemental therapy, 93% of the patients in the trial received the thiazide. The HDFP trial was unique in permitting prescription of potassium-sparing diuretics (spironolactone or triamterene) as supplementary or alternative to the thiazide diuretic “if needed”. It is estimated that approximately 1/4 of stepped care patients received spironolactone and a much smaller number received triamterene.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the trials not mandating use of a potassium-sparing drug.

| Coronary Mortality | Sudden Coronary Death | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Treatment | Control Treatment | Active Treatment | Control Treatment | |||||||

| Trial | Thiazide Dose | Mean Age | Fatal CHD | No. Rand | Fatal CHD | No. Rand | SCD | No. Rand | SCD | No. Rand |

| MRC16 | High | 52 | 59 | 4297 | 97 | 8654 | 33 | 4297 | 45 | 8654 |

| USPHS17 | High | 44 | 2 | 193 | 2 | 196 | 1 | 193 | 1 | 196 |

| VA-NHLBI18 | High | 38 | 2 | 508 | 0 | 504 | 2 | 508 | 0 | 504 |

| Coope19 | High | 69 | 25 | 419 | 28 | 465 | ||||

| VA-I20 | High | 51 | 0 | 68 | 1 | 63 | ||||

| ANBPS21 | High | 50 | 5 | 1721 | 11 | 1706 | ||||

| VA II22 | High | 51 | 6 | 186 | 11 | 194 | 4 | 186 | 8 | 194 |

| PATS23 | High | 60 | 17 | 2841 | 13 | 2824 | ||||

| Subtotal | High | 116 | 10233 | 163 | 14606 | 40 | 5184 | 54 | 9548 | |

| Barraclough24 | Unknown | 56 | 0 | 58 | 1 | 58 | ||||

| Carter25 | Unknown | 2 | 49 | 2 | 48 | |||||

| HSCSG26 | Intermediate | 59 | 4 | 233 | 7 | 219 | 2 | 233 | 2 | 219 |

| Oslo27 | Intermediate | 45 | 6 | 406 | 2 | 379 | 6 | 406 | 2 | 379 |

| SHEP-Pilot28 | Intermediate | 72 | 9 | 443 | 3 | 108 | 7 | 443 | 2 | 108 |

| HYVET Pilot29 | Intermediate | 84 | 11 | 426 | 5 | 426 | ||||

| Subtotal | Intermediate | 30 | 1508 | 17 | 1132 | 15 | 1082 | 6 | 706 | |

| SHEP30 | Low | 72 | 59 | 2365 | 73 | 2371 | 23 | 2365 | 23 | 2371 |

| Subtotal | All trials, without KSD | 207 | 14213 | 256 | 18215 | 78 | 8631 | 83 | 12625 | |

| HDFP14 | Intermediate; optional KSD | 51 | 131 | 5485 | 148 | 5455 | ||||

| Total | All trials | 338 | 19698 | 404 | 23670 | 78 | 8631 | 83 | 12625 | |

“High” thiazide dose = Starting dose of hydrochlorothiazide of 50 mg daily or the equivalent dose of a thiazide-like diuretic

“Intermediate” thiazide dose = Starting dose of hydrochlorothiazide of 25 mg daily or equivalent.

“Low” thiazide dose = chlorthalidone 12.5 mg daily.

KSD = Potassium Sparing Diuretics

MRC = Medical Research Council trial of treatment of mild hypertension

USPHS = United States Public Health Service Hospitals Intervention Trial in Mild Hypertension

VA-NHLBI = Veterans Administration-National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Feasibility Trial: Treatment of Mild Hypertension

Coope = Randomized trial of treatment of hypertension in elderly patients in primary care

VA-I = Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension: Results in patients with diastolic BP 115–129

ANBPS = Australian Therapeutic Trial in Mild Hypertension

VA II = Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension II: Results in patients with diastolic BP 90–114

PATS = Post-Stroke Antihypertensive Treatment Study

Barraclough = Control of moderately raised BP

Carter = Hypotensive therapy in stroke survivors

HSCSG = Hypertension-Stroke Cooperative Study Group

Oslo = The Oslo Study

SHEP- Pilot = Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program Pilot Study

HYVET-Pilot = Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial Pilot Study

SHEP = Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program

HDFP = Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program

The relevant aspects of 13 of these 16 trials have been characterized in previous meta-analyses1, 11. The three trials not previously included and described in these overviews are the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program – Pilot (SHEP-Pilot), Post Stroke Antihypertensive Treatment Study (PATS) and Hypertension in the Very Elderly – Pilot Study (HYVET-Pilot) trials. The characteristics of these 3 trials are described in the WEB Supplemental Data.

Statistical Methods

Meta-analysis was performed using fixed-effect models to examine the combined odds ratio (OR) estimate31. Approximate 95% confidence intervals (CI) were based on the asymptotic normality of the combined estimates and were obtained by exponentiating the upper and lower confidence limits for the log OR. Heterogeneity was calculated using the chi-square test of homogeneity; none of these tests were significant for any of the comparisons reported here. Meta-regression was used to analyze the linear trend between the risk of coronary mortality and thiazide dose32. Statistical analyses were performed with the statistical software R (version 2.2.0, www.r-project.org), SPSS for Windows (version 14.0, SPSS, Chicago), and the Confidence Interval Analysis software (version 2.0.0)33. In R, the rmeta package (version 2.12) by Thomas Lumley was used. The meta-regression analyses were performed using Stata (version 9.0, StataCorp, College Station, TX). A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical tests were two-sided.

RESULTS

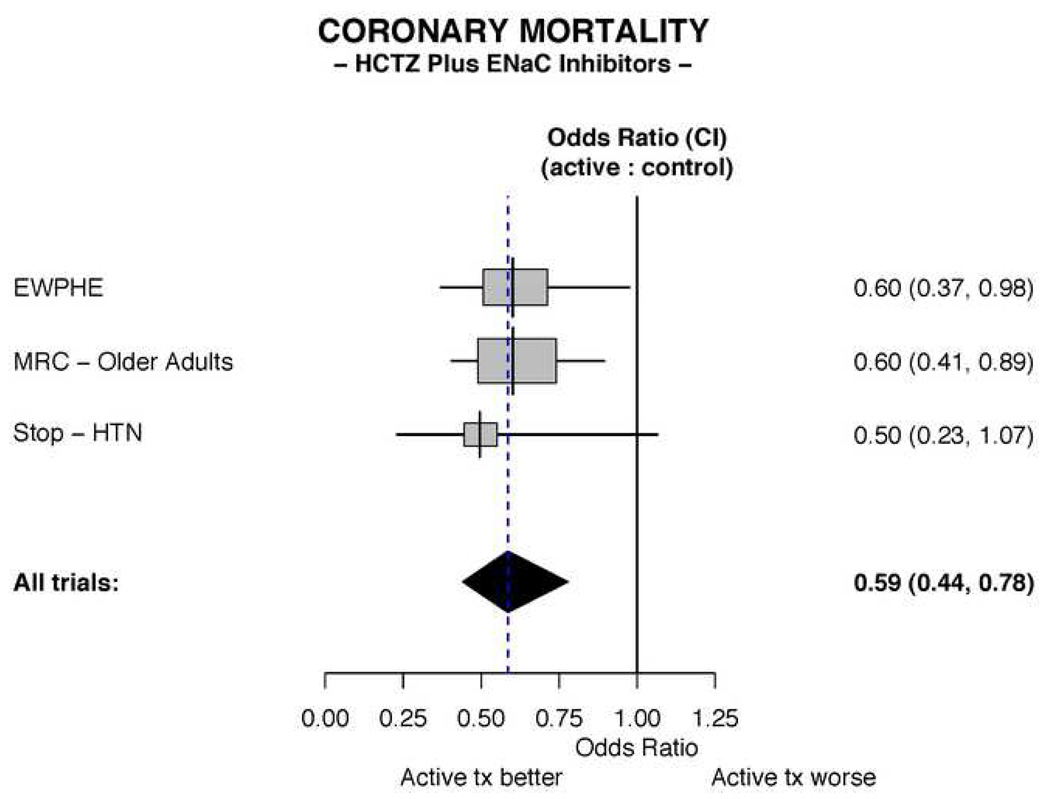

Coronary mortality in trials mandating ENaC inhibitor-HCTZ combination therapy

In the three trials employing an ENaC inhibitor together with HCTZ (Table 1), a total of 249 coronary deaths were reported. In the meta-analysis of these trials conducted in elderly patients, a substantial and significant reduction in coronary mortality was observed in the groups receiving the diuretic combination (Figure 1). The odds ratio for coronary mortality in the actively treated group compared to controls is 0.59 (95% CI 0.44, 0.78).

Figure 1. Meta-analysis of coronary mortality in trials mandating an ENaC inhibitor combined with a thiazide.

The All Trials odds ratio depicted in the figure is calculated by the fixed effects method. Abbreviations: HCTZ = hydrochlorothiazide; CI = Confidence interval.

Sudden cardiac death in trials mandating ENaC inhibitor-HCTZ combination therapy

SCD had been reported as an endpoint in the STOP-HTN trial, and previously unreported data on sudden coronary death from the EWPHE trial was provided for this analysis. As SCDs had not been characterized in the initial analysis of the MRC-Older Adults trial, a blinded analysis of coronary deaths was conducted to determine the subset that resulted from SCD.

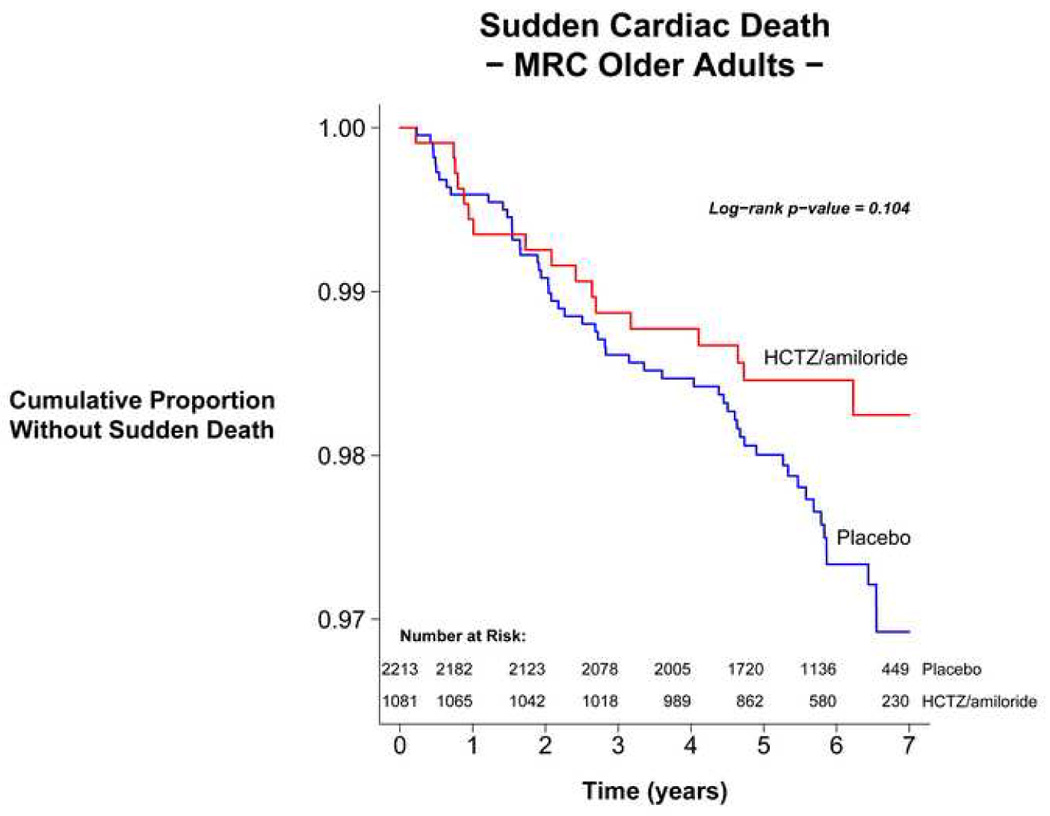

SCD in the MRC-Older Adults Trial

Results from the analysis of the MRC-Older Adults trial yielded 15.7 SCD per thousand in the treated patients and 24.4 per thousand in those on placebo. The odds ratio for SCD in this individual trial is 0.64 (95% CI 0.37, 1.11) in those actively treated versus controls. A survival analysis is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Survival analysis of sudden cardiac deaths in the MRC-Older Adults trial.

Survival was assessed using time from randomization to sudden death. Survival curves were constructed by the Kaplan-Meier method40 with the p value calculated using the log-rank test31.

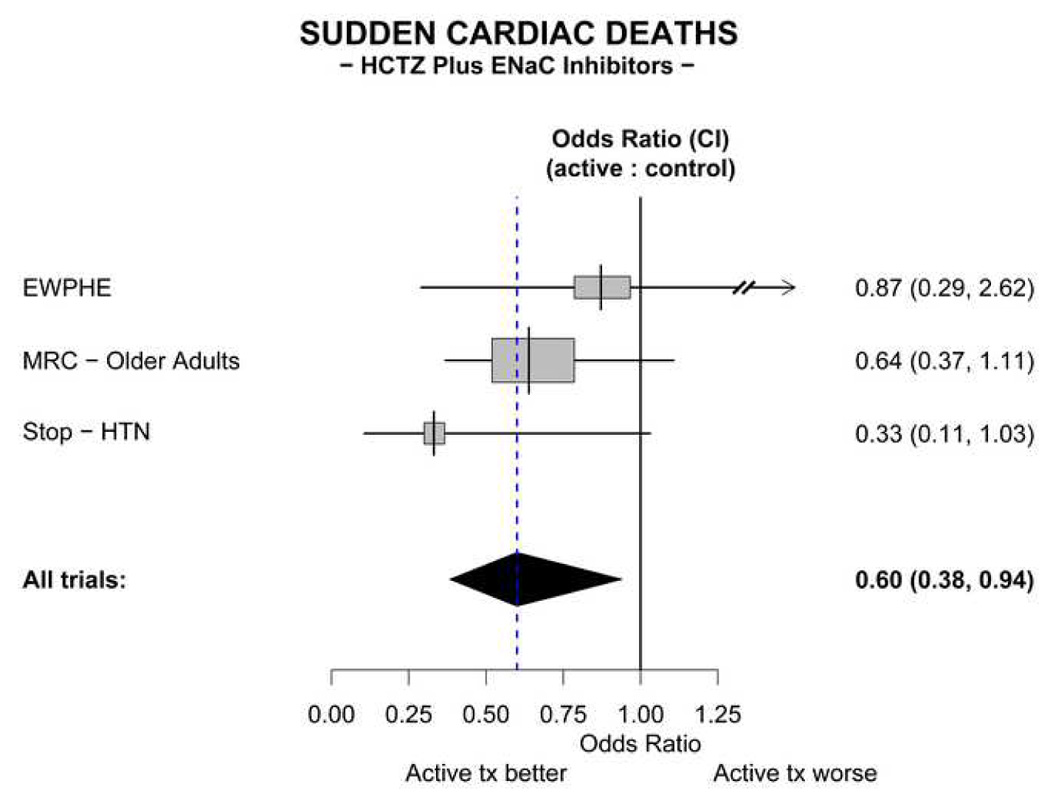

Meta-analysis of SCDs

In the three trials, there were a total of 100 SCDs. A large and significant reduction in SCD in the ENaC inhibitor-HCTZ treated patients is observed in the meta-analysis. SCD occurred in 11.7 patients per thousand in the treated patients, compared with 21.1 per thousand in the placebo group. The odds ratio for SCD in the treated patients compared to the controls is 0.60 (95% CI 0.38, 0.94) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Meta-analysis of sudden cardiac deaths in trials mandating an ENaC inhibitor combined with a thiazide.

The All trials odds ratio depicted in the figure is calculated by t he fixed effects method.

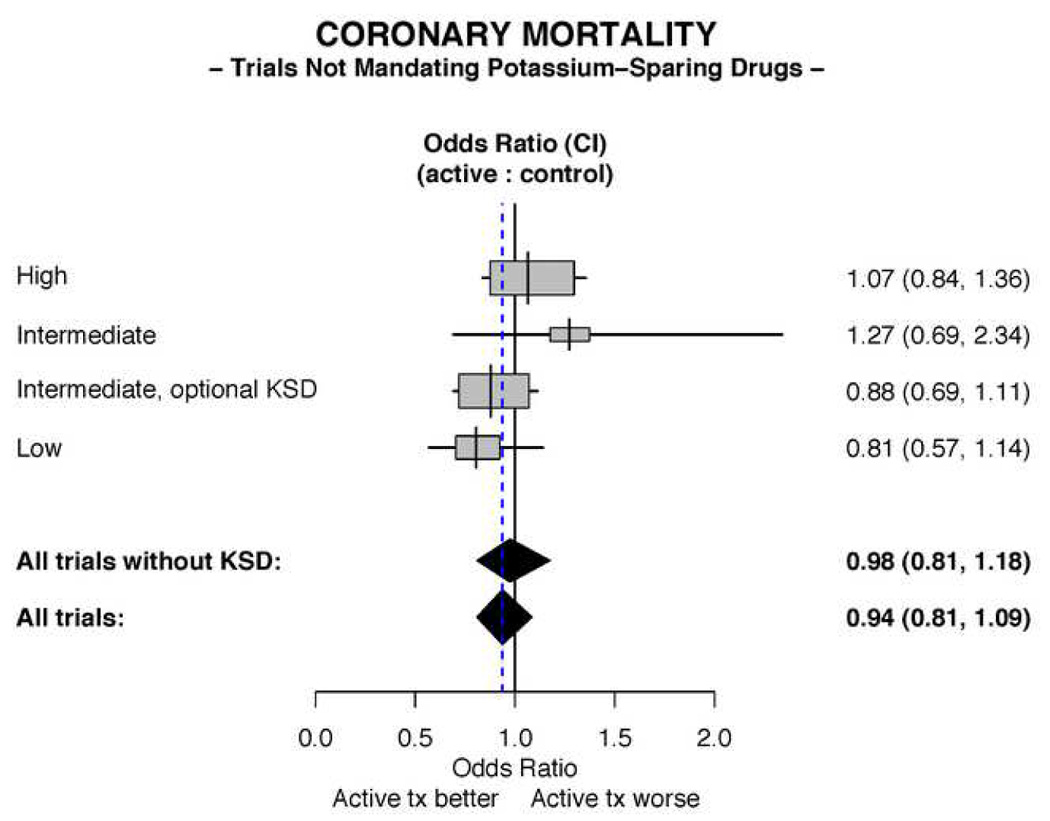

Coronary mortality in trials of diuretics that did not mandate concomitant ENaC inhibitors

In the overview of the 16 trials utilizing diuretics without mandated concomitant potassium-sparing agents (Table 2), the trials were categorized according to dose of diuretic (when reported). In these trials, no significant benefit of therapy on cardiac mortality is demonstrated (Figure 4). The overall odds ratio for coronary mortality in the treatment groups compared to controls is 0.94 (95% CI 0.81, 1.09).

Figure 4. Meta-analyses of coronary mortality in trials not mandating use of a potassium-sparing diuretic.

The All trials and All trials without KSD odds ratios depicted in the figure are calculated by the fixed effects method. The trial designated as “Intermediate, optional KSD” is the HDFP trial.

Excluding HDFP, the only trial that allowed use of potassium-sparing drugs “if needed” as well as the only trial with a “usual care” control group, yields an odds ratio for coronary mortality in the treated patients compared to controls of 0.98 (95% CI 0.81, 1.18).

There is a suggested trend toward a more favorable outcome in the single trial employing the lowest dose of diuretic. A meta-regression of the effect of the high plus intermediate vs. the low dose diuretic yielded a p for trend = 0.15. This comparison is likely underpowered due to the small number of studies involving the intermediate and lowest doses.

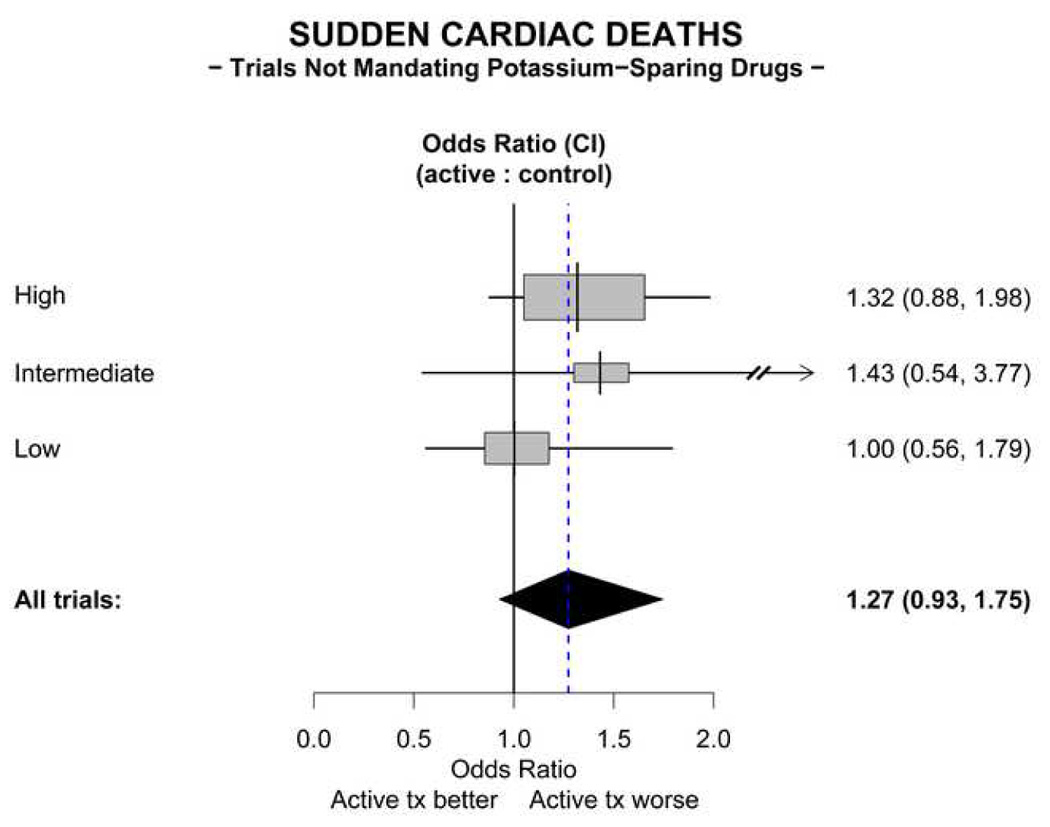

Sudden cardiac death in trials that did not mandate concomitant K+- sparing diuretics

In 8 trials that assessed SCD, a total of 161 events were reported (Table 2). No benefit of thiazide diuretics administered without a potassium-sparing drug on sudden coronary death is demonstrated; indeed, there is a non-significant trend toward a treatment-induced increase in sudden coronary death (Figure 5). The odds ratio for sudden coronary death in treated patients compared with untreated patients is 1.27 (95% CI 0.93, 1.75).

Figure 5. Meta-analysis of sudden cardiac deaths in trials not mandating use of a potassium-sparing diuretic.

The All trials odds ratio depicted in the figure is calculated using the fixed effects method. Abbreviation: KSD = potassium–sparing drugs.

Comparison of the trials mandating ENaC inhibitors with those not requiring K+ sparing diuretics

The trials mandating ENaC inhibitors (ENaC-I trials) all were conducted in the elderly with mean ages of 72, 70, and 76. The trials not mandating potassium- sparing diuretics (Thiazide Alone Trials) included a wider age range (mean ages 38–84) that overlapped the ages in the ENaC-I trials; 5 of the 16 Thiazide Alone Trials studied patients with mean ages ≥ 60. In order to address whether the effect differed as a function of the mean age of patients in the Thiazide Alone Trials, we conducted a meta-regression including the mean age of subjects in the study (<60 vs. >=60) as a predictor for the 14 studies providing this information. The analysis suggested that there was no significant effect of age on the meta-estimates obtained in this study (p = 0.57).

Many of the Thiazide Alone Trials were conducted earlier than the ENaC-I trials, but 222,28 were conducted more recently. Some of these earlier Thiazide Alone Trials evaluated patients with more severe hypertension (eg. Veterans’ Administration I (VA I), Veterans’ Administration II (VA II) and the Hypertension-Stroke Cooperative Study Group (HSCSG)). Although the Thiazide Alone Trials utilized doses of thiazide that ranged from high to low, the group of these with an “intermediate dose” received a dose comparable to that administered in the ENaC-I trials. All of the ENaC-I trials utilized a placebo control group, whereas the HDFP trial compared a “stepped care” group with a group referred to their primary physicians for treatment. However, eliminating HDFP from the analysis of coronary deaths in the Thiazide Alone Trials did not materially change the results.

The antihypertensive effect of a thiazide is known to be enhanced by concomitant administration of an ENaC inhibitor in a subset of the hypertensive population34. Accordingly, the question of whether the favorable outcomes in the trials mandating the use of an ENaC inhibitor with the thiazide could be attributed to a greater reduction of BP was addressed. In trials employing a stepped care approach designed to achieve a target BP reduction in all treated patients, an escalation of diuretic dose and/or addition of another agent would be utilized as needed to achieve a target BP. Thus the extent of BP reduction achieved by the initial dose of thiazide would have little or no effect on the ultimate reduction of BP. Given the goal of the stepped care design to bring all treated patients to target BP, it is not surprising that the magnitude of BP reduction in such trials has been shown to be dependent on the level of pre-treatment BP21. All of the trials mandating use of an ENaC inhibitor employed a form of stepped care, and were placebo-controlled. All but 4 of the Thiazide Alone trials also utilized a placebo-controlled stepped care design. To address the possibility that the trials lacking a stepped care design could have influenced the outcome of the Thiazide Alone trials, an additional meta-analysis of only the placebo-controlled Thiazide Alone trials that did employ a stepped care design (excluding the 4 that did not) was performed (Supplemental Table 1); the odds ratio for coronary mortality in the actively treated group compared to placebo was found to be 1.01 (95% CI 0.83, 1.23), and the odds ratio for SCD in the actively treated group compared to placebo was 1.29 (95% CI 0.93, 1.78). In this group of placebo-controlled stepped care Thiazide Alone trials, the weighted average diastolic BP reduction relative to placebo was - 6.18 mm Hg, and in the ENaC Inhibitor trials it was - 7.7 mm Hg. To further verify that the magnitude of BP reduction in trials with stepped care design is not the determinant of therapeutic effectiveness, the relationship of BP reduction to coronary mortality was assessed in this group of placebo-controlled stepped care designed Thiazide Alone trials in which there was a wide range of BP reductions (WEB Appendix Table 1). A meta-regression performed to assess whether there was a trend in the odds ratio for coronary mortality with respect to blood pressure reduction indicated that there was no significant trend (P=0.706).

In order to allow comparisons of the BPs achieved in the trials with current targets set by the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7), weighted average BP levels were computed. In the treatment arm of the ENaC Inhibitor trials, BP was reduced to a weighted average of 157/84. BP at baseline in these trials had been 188/97. Reporting on BP levels during treatment in the Thiazide Alone trials was incomplete. Only 11 of 16 trials reported systolic BP during treatment, an insufficient number from which to compute a weighted average systolic BP. Fifteen of the 16 trials reported a weighted average diastolic BP of 83.

The fraction of coronary deaths attributable to SCD was similar in the control groups of the ENaC-I trials (41.2%) and in the Thiazide Alone Trials (42.6%).

Whereas differences between the trials and their similarities are addressed here, the primary goal of this evaluation is to assess the effect of the use of the thiazide/ENaC inhibitor combination on coronary mortality and SCD. Analysis of the Thiazide Alone trials is a separate and secondary evaluation to address the question of whether addition of the newer trial data and the removal of data from the ENaC-I trial (EWPHE) would alter the conclusion of no benefit on coronary mortality derived from the earlier major meta-analysis1. These separate analyses should not be considered as an indirect comparison.

DISCUSSION

Treatment of elderly hypertensive patients with an ENaC inhibitor combined with HCTZ reduces coronary mortality significantly and substantially. In addition, a parallel and significant reduction in SCD by an ENaC inhibitor/HCTZ combination is demonstrated by meta-analysis. SCD is a major cause of mortality in treated hypertensive patients, constituting 42% of the coronary deaths in the placebo groups of the trials addressed in this report. Accordingly, a therapeutic strategy targeted at its prevention is of great importance.

ENaC inhibitors prevent thiazide-induced potassium wasting. The ENaC, located primarily in the cortical collecting duct, transports sodium into the tubular epithelial cell, a process coupled to potassium secretion. ENaC activity is stimulated by mineralocorticoids. Therefore, thiazides, by increasing angiotensin II-dependent aldosterone secretion, promote ENaC activity, sodium reabsorption and potassium loss. Amiloride also inhibits the Na+/H+ exchanger located in a number of cell types, including cardiomyocytes, but at much higher concentrations than required to inhibit ENaC.

In addition to preventing thiazide-induced potassium loss, antagonism of the mineralocorticoid-induced sodium reabsorption by ENaC inhibitors provides a mechanistic basis for augmentation of the antihypertensive effect of thiazides by ENaC inhibitors. A recent trial demonstrated that administration of amiloride produced a further reduction in arterial pressure when added to a diuretic-based antihypertensive regimen in elderly African-American patients34. Enhancement of the antihypertensive potency of thiazides by addition of an ENaC inhibitor is unlikely, however, to have affected the ultimate BP reduction in stepped care designed trials, as the level of BP reduction in such trials is a function of the pre-treatment BP21. Accordingly, it is not surprising that the analysis presented here indicates that the odds ratios for coronary outcomes are not determined by the extent of BP reduction in the Thiazide Alone trials. Further, exclusion of the Thiazide Alone trials not employing the stepped care design did not improve the odds ratios for coronary outcomes. The principal consequence of the enhancement of the antihypertensive effect of the initial dose of thiazide by co-administration of an ENaC inhibitor would be that fewer patients would be advanced to a higher dose of thiazide or receive a second class of antihypertensive agent. The resultant sparing of some of the patients from a higher dose of thiazide would be of importance only if thiazides do indeed exert a dose-dependent adverse effect on coronary outcomes.

There is no evidence that thiazides given alone protect from SCD. The failure of thiazides administered without potassium-sparing drugs to reduce SCD in the trials analyzed here is highly unlikely to be the result of a type II statistical error given the non-significant trend towards an increase in sudden coronary death compared to control in these trials.

These results impel consideration of the hypothesis that inhibition of the ENaC protects against thiazide-induced SCD. An increase in SCD caused by thiazide-induced potassium depletion has biologic plausibility. Ischemic ventricular fibrillation is the major cause of SCD in ambulatory patients35–37. In canine models of ischemic ventricular fibrillation, potassium depletion increases both spontaneous and induced ventricular fibrillation4, 5. Ischemia-induced ventricular fibrillation in the perfused rat heart is inversely proportional to potassium concentration over a range of 2–8 mM6. These experimental observations could be the basis for a hypothesis that in acute coronary syndromes in humans, potassium depletion by thiazide diuretics would increase the coupling of ischemia to ventricular fibrillation. According to that hypothesis, reduction in SCD by ENaC inhibitor/thiazide combinations could represent abrogation of an adverse effect of thiazide-induced potassium depletion, leading to survival of the ischemia for sufficient time to reach a medical facility and to receive treatments that markedly improve outcome. However, consideration also must be given to the alternative hypothesis that ENaC inhibitors exert a primary beneficial effect on coronary mortality and SCD, a hypothesis that does not require postulation of an adverse effect of thiazides on these endpoints.

Congruent with the findings in controlled trials analyzed here are the results of two observational studies. A case-control study from Seattle3 found that the risk of primary cardiac arrest in patients receiving a potassium-sparing agent together with a thiazide was lower than that of patients treated with a thiazide alone (odds ratio = 0.3; 95% CI 0.1–0.7), and that the increased risk in patients treated with thiazide alone was dose-dependent. A case-control study from Rotterdam2 also found that the risk of SCD in patients treated with thiazide alone was greater than in those also receiving a potassium-sparing agent (relative risk = 1.8; 95% CI 1.0–3.1).

Whereas the evidence provides a basis for preferential utilization of an ENaC inhibitor/HCTZ combination as diuretic monotherapy in elderly hypertensive patients, the findings also raise important questions. The interchangeability of the ENaC inhibitors is not established. The bulk of the data in the meta-analysis of sudden coronary death is derived from treatment with amiloride. The ratio of ENaC inhibitor dose to that of the thiazide is crucial. Aldosterone antagonists also prevent thiazide-induced potassium wasting. A randomized controlled clinical trial to ascertain whether an aldosterone antagonist combined with a thiazide is equivalent or even superior to an ENaC inhibitor/HCTZ combination would be highly appropriate. Indeed, the perivascular myocardial fibrosis produced by aldosterone occurs independently of the action of the mineralocorticoid on renal ENaC38.

The safety of an ENaC inhibitor/HCTZ combination used in conjunction with other antihypertensive agents that conserve potassium must be addressed. It is well established that ENaC inhibitors should not be given together with or even immediately following an aldosterone antagonist. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor antagonists used alone produce only slight potassium retention, but consideration should be given to the potential that their use together with an ENaC inhibitor or an aldosterone antagonist may adversely elevate serum potassium in patients at risk for hyperkalemia, including those with renal insufficiency, or concurrent administration of a cyclooxygenase inhibitor or high doses of inhibitors of the rennin-angiotensin system.

The stepped care protocols employed in the ENaC Inhibitor trials were limited to two steps (the diuretic plus one additional drug), and yielded a weighted average BP during treatment of 157/84. This level of BP reduction does not achieve the goals of the JNC 7 guidelines (140/90 except for patients with diabetes or renal disease in whom the goal is 130/80). In patients not reaching the target BP with 2 drugs, JNC 7 recommends adding additional agents until the goal is achieved. Given the favorable cardiac outcomes in the ENaC Inhibitor trials, the amiloride/hydrochlorothiazide combination should provide an appropriate therapeutic platform upon which additional agents could be added. The need to add additional agents to the regimen of some patients reinforces the necessity of understanding the safety of combining the amiloride/hydrochlorothiazide combination with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers.

The extent to which the benefit of the ENaC inhibitor/HCTZ combination on SCD extends into younger age groups also is unresolved, as all of the trials on this drug combination were performed in elderly patients. Although the rate of SCD increases with advancing age, the proportion of coronary deaths that are sudden is higher at the younger end of the age spectrum39, accounting for 62% of the coronary deaths in men aged 45–54. Thus, identification of a diuretic regimen that reduces SCD in middle aged patients is of high importance. The optimal evidence would be that from a randomized controlled trial. Until such data might become available, therapeutic decisions in younger patients should be based on the sum of the available evidence.

In conclusion, evidence from controlled clinical trials in concert with observational studies supports the use of an ENaC inhibitor/HCTZ combination as the initial diuretic intervention to reduce sudden coronary death and coronary mortality in elderly hypertensive patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to the investigators of the trials that constitute these analyses, to Thomas W. Meade and Valerie McCormack for providing the data from the MRC-Older Adults trial, and to William D. Dupont for valuable advice. JAO had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GM 15431). JAO is the Thomas F. Frist, Sr. Professor of Medicine. JAO is a consultant for Merck.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Collins R, Peto R, MacMahon S, et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 2, Short-term reductions in blood pressure: overview of randomised drug trials in their epidemiological context. Lancet. 1990;335(8693):827–838. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90944-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoes AW, Grobbee DE, Lubsen J, Man in 't Veld AJ, van der Does E, Hofman A. Diuretics, betablockers, and the risk for sudden cardiac death in hypertensive patients. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123(7):481–487. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-7-199510010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siscovick DS, Raghunathan TE, Psaty BM, et al. Diuretic therapy for hypertension and the risk of primary cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(26):1852–1857. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406303302603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garan H, McGovern BA, Canzanello VJ, et al. The effect of potassium ion depletion on postinfarction canine cardiac arrhythmias. Circulation. 1988 Mar;77(3):696–704. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.77.3.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hohnloser SH, Verrier RL, Lown B, Raeder EA. Effect of hypokalemia on susceptibility to ventricular fibrillation in the normal and ischemic canine heart. Am Heart J. 1986 Jul;112(1):32–35. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(86)90674-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curtis MJ, Hearse DJ. Ischaemia-induced and reperfusion-induced arrhythmias differ in their sensitivity to potassium: implications for mechanisms of initiation and maintenance of ventricular fibrillation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1989 Jan;21(1):21–40. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(89)91490-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults: principal results. MRC Working Party. Bmj. 1992;304(6824):405–412. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6824.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amery A, Birkenhager W, Brixko P, et al. Mortality and morbidity results from the European Working Party on High Blood Pressure in the Elderly trial. Lancet. 1985;1(8442):1349–1354. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91783-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahlof B, Lindholm LH, Hansson L, Schersten B, Ekbom T, Wester PO. Morbidity and mortality in the Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension (STOP-Hypertension) Lancet. 1991;338(8778):1281–1285. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92589-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grobbee DE, Hoes AW. Non-potassium-sparing diuretics and risk of sudden cardiac death. J Hypertens. 1995;13(12 Pt 2):1539–1545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hebert PR, Moser M, Mayer J, Glynn RJ, Hennekens CH. Recent evidence on drug therapy of mild to moderate hypertension and decreased risk of coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 1993 Mar 8;153(5):578–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Psaty BM, Lumley T, Furberg CD, et al. Health outcomes associated with various antihypertensive therapies used as first-line agents: a network meta-analysis. Jama. 2003 May 21;289(19):2534–2544. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Staessen JA, Gasowski J, Wang JG, et al. Risks of untreated and treated isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly: meta-analysis of outcome trials. Lancet. 2000 Mar 11;355(9207):865–872. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)07330-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borhani NO, Blaufox MD, Oberman A, Polk BF. Incidence of coronary heart disease and left ventricular hypertrophy in the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1986 Nov-Dec;29(3 Suppl 1):55–62. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(86)90034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research Group. Multiple risk factor intervention trial. Risk factor changes and mortality results. JAMA. 1982 Sep 24;248(12):1465–1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medical Research Council Working Party on Mild Hypertension. Coronary heart disease in the Medical Research Council trial of treatment of mild hypertension. Br Heart J. 1988;59(3):364–378. doi: 10.1136/hrt.59.3.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith WM. Treatment of mild hypertension: results of a ten-year intervention trial. Circ Res. 1977;40(5 Suppl 1):I98–I105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evaluation of drug treatment in mild hypertension: VA-NHLBI feasibility trial. Plan and preliminary results of a two-year feasibility trial for a multicenter intervention study to evaluate the benefits versus the disadvantages of treating mild hypertension. Prepared for the Veterans Administration-National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Study Group for Evaluating Treatment in Mild Hypertension. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1978;304:267–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1978.tb25604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coope J, Warrender TS. Randomised trial of treatment of hypertension in elderly patients in primary care. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986 Nov 1;293(6555):1145–1151. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6555.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressures averaging 115 through 129 mm Hg. Jama. 1967;202(11):1028–1034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Australian therapeutic trial in mild hypertension. Report by the Management Committee. Lancet. 1980;1(8181):1261–1267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. II. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressure averaging 90 through 114 mm Hg. Jama. 1970;213(7):1143–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.PATS Collaborating Group. Post-stroke antihypertensive treatment study. A preliminary result. Chin Med J (Engl) 1995 Sep;108(9):710–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Control of moderately raised blood pressure. Report of a co-operative randomized controlled trial. Br Med J. 1973;3(5877):434–436. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carter AB. Hypotensive therapy in stroke survivors. Lancet. 1970;1(7645):485–489. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(70)91577-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hypertension- Stroke Cooperative Study Group. Effect of antihypertensive treatment on stroke recurrence. Jama. 1974;229(4):409–418. doi: 10.1001/jama.1974.03230420021019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Helgeland A. Treatment of mild hypertension: a five year controlled drug trial. The Oslo study. Am J Med. 1980;69(5):725–732. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90438-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perry HM, Jr, Smith WM, McDonald RH, et al. Morbidity and mortality in the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) pilot study. Stroke. 1989;20(1):4–13. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bulpitt CJ, Beckett NS, Cooke J, et al. Results of the pilot study for the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial. J Hypertens. 2003 Dec;21(12):2409–2417. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200312000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) Jama. 1991;265(24):3255–3264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986 Sep;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Egger M, Smith G, Altman D. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-analysis in Context. 2nd ed. London: BMJ Publishing Co; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altman D, Machin D, Bryant T, Gardner M. 2nd ed. London: British Medical Journal; 2000. Statistics with confidence - confidence intervals and statistical guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saha C, Eckert GJ, Ambrosius WT, et al. Improvement in blood pressure with inhibition of the epithelial sodium channel in blacks with hypertension. Hypertension. 2005 Sep;46(3):481–487. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000179582.42830.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burke AP, Farb A, Malcom GT, Liang Y, Smialek JE, Virmani R. Plaque rupture and sudden death related to exertion in men with coronary artery disease. Jama. 1999 Mar 10;281(10):921–926. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davies MJ, Thomas A. Thrombosis and acute coronary-artery lesions in sudden cardiac ischemic death. N Engl J Med. 1984 May 3;310(18):1137–1140. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198405033101801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spaulding CM, Joly LM, Rosenberg A, et al. Immediate coronary angiography in survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 1997 Jun 5;336(23):1629–1633. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706053362302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Campbell SE, Janicki JS, Matsubara BB, Weber KT. Myocardial fibrosis in the rat with mineralocorticoid excess. Prevention of scarring by amiloride. Am J Hypertens. 1993 Jun;6(6 Pt 1):487–495. doi: 10.1093/ajh/6.6.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schatzkin A, Cupples LA, Heeren T, Morelock S, Kannel WB. Sudden death in the Framingham Heart Study. Differences in incidence and risk factors by sex and coronary disease status. Am J Epidemiol. 1984 Dec;120(6):888–899. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaplan E, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Statistical Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.