Abstract

How can the central nervous system make accurate decisions about external stimuli at short times on the basis of the noisy responses of nerve cell populations? It has been suggested that spike time latency is the source of fast decisions. Here, we propose a simple and fast readout mechanism, the temporal Winner-Take-All (tWTA), and undertake a study of its accuracy. The tWTA is studied in the framework of a statistical model for the dynamic response of a nerve cell population to an external stimulus. Each cell is characterized by a preferred stimulus, a unique value of the external stimulus for which it responds fastest. The tWTA estimate for the stimulus is the preferred stimulus of the cell that fired the first spike in the entire population. We then pose the questions: How accurate is the tWTA readout? What are the parameters that govern this accuracy? What are the effects of noise correlations and baseline firing? We find that tWTA sensitivity to the stimulus grows algebraically fast with the number of cells in the population, N, in contrast to the logarithmic slow scaling of the conventional rate-WTA sensitivity with N. Noise correlations in first-spike times of different cells can limit the accuracy of the tWTA readout, even in the limit of large N, similar to the effect that has been observed in population coding theory. We show that baseline firing also has a detrimental effect on tWTA accuracy. We suggest a generalization of the tWTA, the n-tWTA, which estimates the stimulus by the identity of the group of cells firing the first n spikes and show how this simple generalization can overcome the detrimental effect of baseline firing. Thus, the tWTA can provide fast and accurate responses discriminating between a small number of alternatives. High accuracy in estimation of a continuous stimulus can be obtained using the n-tWTA.

Author Summary

Considerable experimental as well as theoretical effort has been devoted to the investigation of the neural code. The traditional approach has been to study the information content of the total neural spike count during a long period of time. However, in many cases, the central nervous system is required to estimate the external stimulus at much shorter times. What readout mechanism could account for such fast decisions? We suggest a readout mechanism that estimates the external stimulus by the first spike in the population, the tWTA. We show that the tWTA can account for accurate discriminations between a small number of choices. We find that the accuracy of the tWTA is limited by the neuronal baseline firing. We further find that, due to baseline firing, the single first spike does not encode sufficient information for estimating a continuous variable, such as the direction of motion of a visual stimulus, with fine resolution. In such cases, fast and accurate decisions can be obtained by a generalization of the tWTA to a readout that estimates the stimulus by the first n spikes fire by the population, where n is larger than the mean number of baseline spikes in the population.

Introduction

In recent years, there has been growing interest in coding information about external stimuli by the fine temporal structure of the neural dynamic response [1]–[18]. Several studies have shown that response latency is modulated by external stimuli [1]–[4]. Many cells in the middle temporal (MT) cortex code for the direction of motion of visual stimuli, and can be characterized by a preferred direction of the stimulus, to which they respond maximally, see e.g., [19],[20]. Osborne et al. [1] reported that the MT cells respond with the shortest delay when the stimulus is in their preferred direction and that the response delay increases as the stimulus direction diverges from the preferred direction of the cell. In the auditory system of the ferret, Nelken et al. [2] showed response-latency tuning in primary auditory cortex cells to the direction of a virtual sound source. In a recent work Gollisch and Meister [18] showed that relative first-spike times of retinal ganglion cells carry considerable information about the external stimulus, but they did not suggest a concrete readout mechanism.

Here we study the accuracy of a simple readout mechanism, the temporal-Winner-Take-All (tWTA), which extracts information from response latency. The tWTA estimates the stimulus by the identity of the cell that fired the first spike in a population of cells, in contrast to the conventional rate-Winner-Take-All (WTA), which estimates the stimulus by the identity of the cell that fired the most spikes. For example, the tWTA estimate for the direction of motion of a visual stimulus from the responses of a population of MT cells would be the preferred direction of the cell that fired the first spike in the entire population.

Considerable theoretical effort has been devoted to the study of the accuracy of population code readout mechanisms, such as the population-vector, optimal-linear and ideal observer readouts. Of particular interest in the investigation of these readouts was the dependence of the readout accuracy on the population size and the effects of noise correlations in the neuronal responses. In this work, we quantify tWTA accuracy. To this end, we address three specific questions. One, what are the essential features of the neuronal dynamic response to the stimulus to which the tWTA is sensitive? Two, how does the tWTA accuracy depend on the population size? Three, what are the effects of noise correlations and baseline firing on tWTA accuracy?

These questions are addressed in the framework of a statistical model for the dynamic response of MT cells to a moving visual stimulus. In the first part of the results section we investigate tWTA accuracy in a two-column competition model, and in the second part we study tWTA accuracy in the framework of a hypercolumn model. Both parts start by defining the statistical model of the neuronal dynamic response and then follow with an investigation of tWTA accuracy in the absence of noise correlations and baseline firing. In the final stage of each part, correlations and baseline firing are introduced and their effect on tWTA accuracy is investigated.

Results

tWTA Readout Accuracy in a Two Competing Columns Model

The model

We study tWTA accuracy in a model of two competing MT columns coding for the

direction of motion of visual stimuli. Each column is comprised of  homogeneous cells. We denote the preferred direction of

the cells in column 1 by

homogeneous cells. We denote the preferred direction of

the cells in column 1 by  and the preferred direction of the cells in column 2 by

and the preferred direction of the cells in column 2 by  . Without loss of generality, we take

. Without loss of generality, we take  , which is equivalent to measuring all angles with respect

to

, which is equivalent to measuring all angles with respect

to  . We denote the probability density of a single cell

. We denote the probability density of a single cell  (

( ) in column

) in column  with preferred direction

with preferred direction  to fire its first spike at time

to fire its first spike at time  given that stimulus

given that stimulus  was presented at time

was presented at time  by

by  . Assuming that first-spike times are statistically

independent, the probability density of the first spike in the entire column

. Assuming that first-spike times are statistically

independent, the probability density of the first spike in the entire column  at time

at time  is given by the product of three terms: the probability

density of a specific cell to fire its first at time

is given by the product of three terms: the probability

density of a specific cell to fire its first at time  ,

,  , the probability that that the first spike times of the

rest

, the probability that that the first spike times of the

rest  cells in the population occurred after time

t,

cells in the population occurred after time

t,  , and the

, and the  different possibilities of choosing the cell that fired

the first spike:

different possibilities of choosing the cell that fired

the first spike:

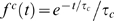

| (1) |

| (2) |

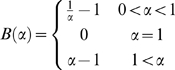

The function  is the logarithm of the probability of a single cell

firing its first spike after time

is the logarithm of the probability of a single cell

firing its first spike after time  , and it has the following properties:

, and it has the following properties:  ,

,  and

and  . Equation (1) can also be obtained by taking the

derivative of the probability that the first spike in the column occurred

after time

. Equation (1) can also be obtained by taking the

derivative of the probability that the first spike in the column occurred

after time  :

:  , with respect to first spike time,

, with respect to first spike time,  .

.

Throughout this section, we will quantify tWTA accuracy by using the two

alternative forced choice (2AFC) paradigm. In a 2AFC discrimination task,

the system is given a stimulus, either  or

or  , randomly with equal probabilities. Presentation of the

stimulus generates a population response in the two columns,

, randomly with equal probabilities. Presentation of the

stimulus generates a population response in the two columns,  and

and  , which are distributed as defined above. The task of the

readout is to infer, on the basis of these spike times, whether the stimulus

was

, which are distributed as defined above. The task of the

readout is to infer, on the basis of these spike times, whether the stimulus

was  or

or  . We will use the probability of correct discrimination,

. We will use the probability of correct discrimination,  , and the error rate,

, and the error rate,  , as measures of the tWTA performance. We will use the term

sensitivity to designate the inverse of the stimulus

difference,

, as measures of the tWTA performance. We will use the term

sensitivity to designate the inverse of the stimulus

difference,  , at which

, at which  crosses a certain threshold,

crosses a certain threshold,  . This latter measure is related to the

‘just noticeable difference’ used

in psychophysics.

. This latter measure is related to the

‘just noticeable difference’ used

in psychophysics.

tWTA accuracy in the absence of correlations

Assuming that column 1 responds faster to a stimulus in direction  than column 2 and vice versa for stimulus

than column 2 and vice versa for stimulus  , we define the tWTA readout in the 2AFC task as follows:

, we define the tWTA readout in the 2AFC task as follows:

|

(3) |

For the sake of convenience, we take  and

and  . This choice equalizes the probability of correct response

given stimulus

. This choice equalizes the probability of correct response

given stimulus  and given stimulus

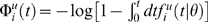

and given stimulus  . The probability of correct response,

. The probability of correct response,  , is given by the probability that population 1 fired the

first spike, given stimulus

, is given by the probability that population 1 fired the

first spike, given stimulus  . Thus,

. Thus,  can be written as the integration over all possible

first-spike times,

can be written as the integration over all possible

first-spike times,  , of the probability density that population 1 fired its

first spike at time

, of the probability density that population 1 fired its

first spike at time  multiplied by the probability that the first spike time of

population 2 is large than

multiplied by the probability that the first spike time of

population 2 is large than  :

:

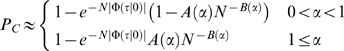

| (4) |

In the limit of large populations,  , the integral in the right-hand-side of equation (4) will

be dominated by the region in which the exponent obtains its maximum. Since

, the integral in the right-hand-side of equation (4) will

be dominated by the region in which the exponent obtains its maximum. Since  is a monotonically decreasing function of

is a monotonically decreasing function of  , this region is the region of small

, this region is the region of small  . For small

. For small  , we approximate

, we approximate  by:

by:

| (5) |

where  is the scale parameter,

is the scale parameter,  is the shape parameter,

is the shape parameter,  is the delay parameter and

is the delay parameter and  for

for  and 0 otherwise.

and 0 otherwise.

Relation to the peri stimulus time histogram (PSTH) in an inhomogeneous Poisson process (IHPP)

The IHPP is widely used to model the stochastic nature of the neural temporal

response [21],[22] and is fully

defined by the PSTH. In the context of first spike-time distribution, the

choice of an IHPP model does not limit the generality of the model, since

every PSTH,  , of an IHPP could be mapped to first spike time

distribution,

, of an IHPP could be mapped to first spike time

distribution,  , and vice versa. For a given IHPP with PSTH,

, and vice versa. For a given IHPP with PSTH,  , the first spike time distribution is given by (see e.g.,

[21],[22])

, the first spike time distribution is given by (see e.g.,

[21],[22])

| (6) |

In the other direction, we want to obtain the PSTH,  , that will yield a specific first spike time distribution,

, that will yield a specific first spike time distribution,  , in an IHPP model. The probability density that the first

spike has occurred in time

, in an IHPP model. The probability density that the first

spike has occurred in time  in an IHPP model, can be written as the product of the

probability density of spiking at that time,

in an IHPP model, can be written as the product of the

probability density of spiking at that time,  , multiplied by the probability that there were no prior

spikes,

, multiplied by the probability that there were no prior

spikes,  ; hence,

; hence,  . Thus we obtain the reciprocal relation

. Thus we obtain the reciprocal relation

| (7) |

which could be verified by substituting equation (7) into

equation (6). For small  :

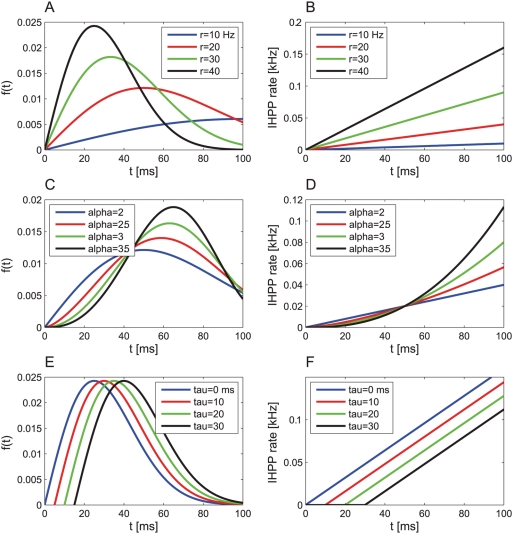

:  . Thus, the scale parameter corresponds to the scale of the

PSTH, the shape parameter governs the initial acceleration of the PSTH, and

the delay parameter measures the temporal shift of the PSTH. Figure 1 illustrates how

the different parameters that characterize the initial neural response:

scale, shape and delay, affect the first spike probability density and the

corresponding PSTH. Note that whereas

. Thus, the scale parameter corresponds to the scale of the

PSTH, the shape parameter governs the initial acceleration of the PSTH, and

the delay parameter measures the temporal shift of the PSTH. Figure 1 illustrates how

the different parameters that characterize the initial neural response:

scale, shape and delay, affect the first spike probability density and the

corresponding PSTH. Note that whereas  and

and  are very similar for small

are very similar for small  , for large

, for large  ,

,  decays to zero while

decays to zero while  may continue to increase. Below we study the different

effects of the tuning of these parameters on the accuracy of the tWTA.

may continue to increase. Below we study the different

effects of the tuning of these parameters on the accuracy of the tWTA.

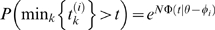

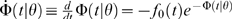

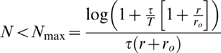

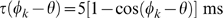

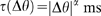

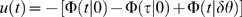

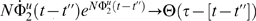

Figure 1. Three examples showing the effects of the scale parameter (a,b),

the shape parameter (c,d), and the delay parameter (e,f) on the

first spike time probability density,  , (left column) and the PSTH rate,

, (left column) and the PSTH rate,  , of a corresponding inhomogeneous Poisson process

(right column).

, of a corresponding inhomogeneous Poisson process

(right column).

The PSTHs were taken to be of the form of  (compare with equation 5), and

(compare with equation 5), and  is obtained via the relation of equation (6). The

parameters used to generate the plots are as follows. For a and b:

is obtained via the relation of equation (6). The

parameters used to generate the plots are as follows. For a and b:  ,

,  , and

, and  as appears on the figure. For (c,d):

as appears on the figure. For (c,d):  ,

,  , and

, and  as appears on the figure. For (e,f):

as appears on the figure. For (e,f):  ,

,  , and

, and  as appears on the figure.

as appears on the figure.

Effect of scale parameter tuning

We first consider a simple model in which the scale is the only parameter

that is tuned to the stimulus. In this case, we can write  near

near  as the product of a function of the stimulus and a

function of time:

as the product of a function of the stimulus and a

function of time:

| (8) |

where  is independent of

is independent of  . Expanding

. Expanding  in small

in small  ,

,  and substituting in equation (4), we obtain to a leading

order in

and substituting in equation (4), we obtain to a leading

order in

|

(9) |

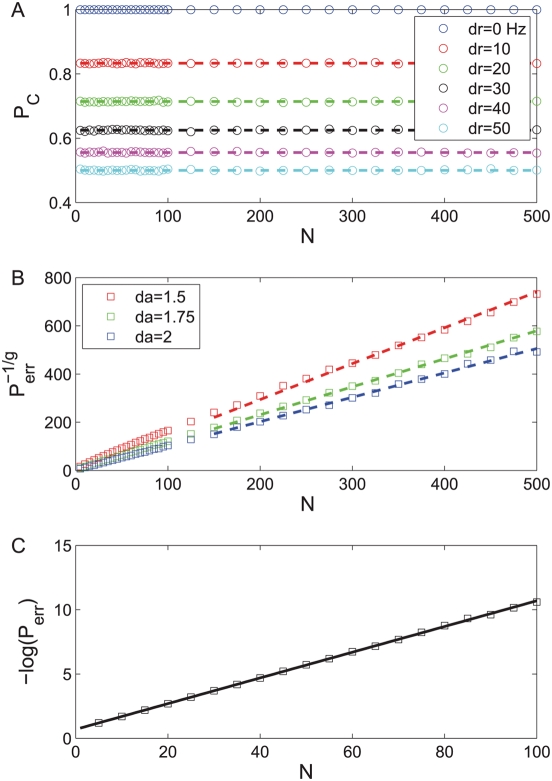

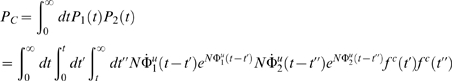

Hence, in this case, the probability of correct response is

at chance level,  , when the neural response has the same scale for the two

alternatives,

, when the neural response has the same scale for the two

alternatives,  , and increases monotonically in the ratio

, and increases monotonically in the ratio  . The accuracy of the tWTA is not improved by increasing

. The accuracy of the tWTA is not improved by increasing  : The same accuracy will be obtained with

: The same accuracy will be obtained with  and

and  cells, but, somewhat faster for the

cells, but, somewhat faster for the  case. Figure

2a shows the probability of correct discrimination as a function

of

case. Figure

2a shows the probability of correct discrimination as a function

of  for different values of

for different values of  from top to bottom. The open circles are estimates of the

tWTA accuracy obtained by averaging the tWTA accuracy over 106

realizations of the neural stochastic response. The dashed line shows the

analytical prediction of equation 9 with

from top to bottom. The open circles are estimates of the

tWTA accuracy obtained by averaging the tWTA accuracy over 106

realizations of the neural stochastic response. The dashed line shows the

analytical prediction of equation 9 with  .

.

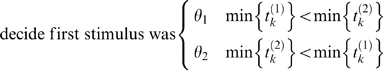

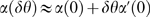

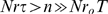

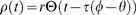

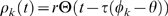

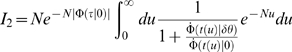

Figure 2. tWTA performance in a 2AFC discrimination task between stimulus

0° and  in a two-column model as function of the number of

cells in the population.

in a two-column model as function of the number of

cells in the population.

Open symbols show numerical estimation of the tWTA performance as

obtained by averaging the probability of correct discrimination over

106 realizations of the stochastic neural responses.

Probability distribution of first spike times followed an IHPP with

the following PSTHs. (a) Scale parameter tuning:  with

with  and

and  from top to bottom. The dashed lines show the

analytical prediction of equation (9). (b) Shape parameter tuning:

from top to bottom. The dashed lines show the

analytical prediction of equation (9). (b) Shape parameter tuning:  with

with  ,

,  and

and  from top to bottom. The tWTA performance is shown

in terms of

from top to bottom. The tWTA performance is shown

in terms of  where

where  . The dashed lines show linear regression lines in

keeping with the prediction of equation (12). (c) Delay parameter

tuning:

. The dashed lines show linear regression lines in

keeping with the prediction of equation (12). (c) Delay parameter

tuning:  with

with  ,

,  and

and  . The tWTA performance is shown in terms of minus

the log of the error rate. The solid line shows the analytical

prediction of equation (15).

. The tWTA performance is shown in terms of minus

the log of the error rate. The solid line shows the analytical

prediction of equation (15).

Effect of shape parameter tuning

In the case where only the shape parameter,  , is tuned to the stimulus, we write:

, is tuned to the stimulus, we write:

| (10) |

where  is independent of

is independent of  . We assume that population 1, with preferred direction

. We assume that population 1, with preferred direction  , fires faster than population 2, with preferred direction

, fires faster than population 2, with preferred direction  , given stimulus

, given stimulus  , in the sense that for short times the probability of

firing of cell in population 2 is larger than that in population 1; hence,

, in the sense that for short times the probability of

firing of cell in population 2 is larger than that in population 1; hence,  . To compute

. To compute  in the limit of large populations, equation (4), it is

convenient to make a change of variables to

in the limit of large populations, equation (4), it is

convenient to make a change of variables to  , yielding:

, yielding:

|

(11) |

where  is the time derivative of

is the time derivative of  ,

,  . To leading order in small

. To leading order in small  for

for  ,

,  . Applying Watson's Lemma [23] we obtain the

asymptotic approximation for the error rate:

. Applying Watson's Lemma [23] we obtain the

asymptotic approximation for the error rate:

| (12) |

Hence, in this case, the probability of error decays

algebraically with  to zero. This scaling of the readout accuracy with

population size is similar to the scaling of the conventional rate-WTA

accuracy with population size [24]. For small

to zero. This scaling of the readout accuracy with

population size is similar to the scaling of the conventional rate-WTA

accuracy with population size [24]. For small  ,

,  , we obtain:

, we obtain:

| (13) |

Thus, although in this case tWTA sensitivity improves by

utilizing larger populations, this logarithmic improvement is extremely

slow. Figure 2b shows

the discrimination error rate to the power of  as a function of

as a function of  for different values of

for different values of  from top to bottom. The open squares are estimates of the

tWTA accuracy obtained by averaging tWTA accuracy over 106

realizations of the neural stochastic response. The dashed lines show linear

regression fits to the curves, in keeping with the asymptotic relation of

equation (12).

from top to bottom. The open squares are estimates of the

tWTA accuracy obtained by averaging tWTA accuracy over 106

realizations of the neural stochastic response. The dashed lines show linear

regression fits to the curves, in keeping with the asymptotic relation of

equation (12).

Effect of delay parameter tuning

In the case where the delay parameter,  , is the only the parameter that is tuned to the stimulus,

we write:

, is the only the parameter that is tuned to the stimulus,

we write:

| (14) |

where  is the Heavyside function:

is the Heavyside function:  for

for  and 0 otherwise. In this case. we find (see Methods) that the probability of error

decays exponentially fast with the population size,

and 0 otherwise. In this case. we find (see Methods) that the probability of error

decays exponentially fast with the population size,  :

:

| (15) |

| (16) |

where  is defined in Methods. Hence, in this case, the tWTA error rate decays to zero

exponentially with

is defined in Methods. Hence, in this case, the tWTA error rate decays to zero

exponentially with  , in contrast to the slow algebraic scaling of the

conventional rate-WTA accuracy with the population size [24]. For small

, in contrast to the slow algebraic scaling of the

conventional rate-WTA accuracy with the population size [24]. For small  , we can expand the delay parameter,

, we can expand the delay parameter,  , in

, in  and approximate

and approximate  ; for small

; for small  , we thus find that tWTA sensitivity grows algebraically

with

, we thus find that tWTA sensitivity grows algebraically

with  :

:

| (17) |

in contrast to the logarithmic scaling of the conventional rate-WTA sensitivity with population size [24]. Figure 2c shows minus the logarithm of the discrimination error rate in the case of delay parameter tuning to the stimulus. The open squares are estimates of the tWTA accuracy obtained by averaging tWTA accuracy over 106 realizations of the neural stochastic response. The solid line shows the analytical prediction of equation (15).

The different effects exerted by scale, shape and delay parameters on the

scaling of the tWTA accuracy with the population size highlights the

sensitivity of the tWTA to fine details of the first-spike-time

distribution. Nevertheless, in the general case, all parameters will be

tuned to the stimulus. The dominant contribution to the tWTA accuracy will

result from the tuning of the delay parameter. Hence, the tWTA error rate

will decay exponentially fast to zero with  , and the sensitivity will scale algebraically with

, and the sensitivity will scale algebraically with  . We will therefore focus hereafter on models in which the

delay parameter is tuned to the stimulus and ignore the tuning of other

parameters to the stimulus.

. We will therefore focus hereafter on models in which the

delay parameter is tuned to the stimulus and ignore the tuning of other

parameters to the stimulus.

Two important factors may have a considerable effect on the tWTA accuracy are addressed below. The first is noise correlations in the fluctuations of first spike times of different cells. It has been shown that noise correlations have a considerable effect on population code readout accuracy [25]–[29]. The second factors is nonzero baseline firing rate.

Effect of correlations on the tWTA accuracy

How should the covariance between first spike times of different cells be

modeled? One possible mechanism that can cause correlated firing is having a

shared input. Two cells that receive a common input that fluctuates above

its mean will integrate it over time and reach spiking threshold sooner than

their average first spike time. If the common input fluctuates below its

average value, spike time of both cells will be delayed. It is reasonable to

assume that cells that are functionally close, i.e., have

similar preferred directions, will have more common input. Hence, their

first spike times are expected to be more positively correlated. motivated

by this intuition, we model correlations by adding a uniform random shift,  , to the spike times of the cells in column

, to the spike times of the cells in column  , which represents the effect of fluctuations in shared

inputs to cells in every column. Thus, we write the first spike time

, which represents the effect of fluctuations in shared

inputs to cells in every column. Thus, we write the first spike time  of neuron

of neuron  in population

in population  as the sum of a correlated term and an independent term:

as the sum of a correlated term and an independent term:

| (18) |

where  are statistically independent, given the stimulus, with

probability distribution

are statistically independent, given the stimulus, with

probability distribution  . We assume that, given stimulus

. We assume that, given stimulus  ,

,  is delayed relative to

is delayed relative to  by

by  , i.e.,

, i.e.,  for

for  whereas

whereas  for

for  . The correlated components,

. The correlated components,  and

and  , are independent, with probability distribution

, are independent, with probability distribution  . In the limit of large

. In the limit of large  , the probability of correct discrimination is given by

(see Methods):

, the probability of correct discrimination is given by

(see Methods):

| (19) |

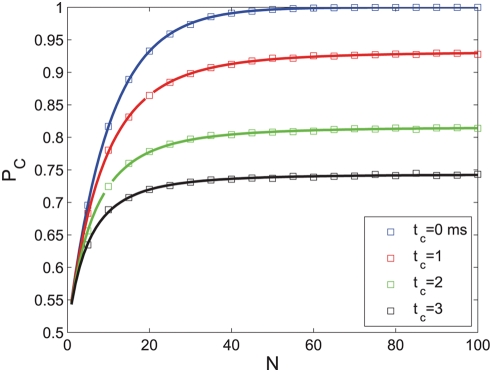

Hence, for large populations, the uncorrelated fluctuations

can be ignored, and the probability of correct discrimination saturates to a

size-independent limit. Figure

3 shows the performance of the tWTA, in terms of percent correct

discrimination, as a function of the number of cells in each column,  , for increasing values of

, for increasing values of  from top to bottom. In the simulations, we used a model in

which only the delay parameter is tuned to the stimulus. Specifically we

took:

from top to bottom. In the simulations, we used a model in

which only the delay parameter is tuned to the stimulus. Specifically we

took:  with

with  and

and  . For the correlated, part we used

. For the correlated, part we used  . In this case we obtain (see Methods):

. In this case we obtain (see Methods):

|

(20) |

| (21) |

In the absence of correlations,  , equation (20) converges to equation (15) with

, equation (20) converges to equation (15) with  and

and  . The error rate,

. The error rate,  , decays to zero exponentially with the number of cells,

, decays to zero exponentially with the number of cells,  . In the presence of correlations,

. In the presence of correlations,  , for small populations,

, for small populations,  , the tWTA error rate decays exponentially with

, the tWTA error rate decays exponentially with  , as in the uncorrelated case, equation (15). When

, as in the uncorrelated case, equation (15). When  , tWTA performance reaches the saturation regime, and tWTA

accuracy converges to a finite limit for

, tWTA performance reaches the saturation regime, and tWTA

accuracy converges to a finite limit for  :

:

| (22) |

Hence, in the presence of correlations for large  , the tWTA error rate is an increasing function of

, the tWTA error rate is an increasing function of  , which saturates to chance level (chance level:

, which saturates to chance level (chance level:  ) in the limit of

) in the limit of  .

.

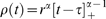

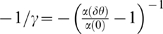

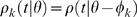

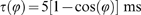

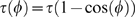

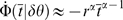

Figure 3. Effect of correlations on the tWTA readout accuracy.

The probability of tWTA correct response,  , in the presence of noise correlations is shown as

a function of the population size,

, in the presence of noise correlations is shown as

a function of the population size,  . Open squares show numerical estimation of the

probability of correct response by averaging over 105

trials of simulating the network stochastic response. The model was

defined as in section ‘effect of correlations on the tWTA

accuracy’. We write the first spike time

. Open squares show numerical estimation of the

probability of correct response by averaging over 105

trials of simulating the network stochastic response. The model was

defined as in section ‘effect of correlations on the tWTA

accuracy’. We write the first spike time  of neuron

of neuron  in population

in population  as the sum of a correlated term and an independent

term:

as the sum of a correlated term and an independent

term:  (see equation 18), where

(see equation 18), where  are statistically independent, given the stimulus,

with probability distribution

are statistically independent, given the stimulus,

with probability distribution  . Specifically, here we took:

. Specifically, here we took:  with

with  and

and  . The probability density of the correlated part,

. The probability density of the correlated part,  , is given by

, is given by  . The parameters that were used for the simulations

are:

. The parameters that were used for the simulations

are:  ,

,  and

and  from top to bottom. The solid lines show the

analytical result of equation (20).

from top to bottom. The solid lines show the

analytical result of equation (20).

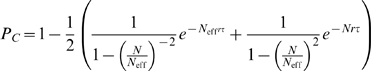

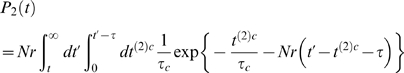

Effect of baseline firing on tWTA accuracy

In the above analysis we assumed zero baseline firing for all cells. However, nonzero baseline firing may have a significant effect on the tWTA accuracy. To incorporate baseline firing into our model, it is most convenient to use the framework of the IHPP, which is defined by the PSTH. The PSTHs of the two populations are modeled by:

| (23) |

where,  is the baseline firing rate (

is the baseline firing rate ( ) and

) and  is the duration in which both columns fire at baseline

prior to responding selectively to the stimulus. The function

is the duration in which both columns fire at baseline

prior to responding selectively to the stimulus. The function  is the tuning of the delay parameter. As above we take

is the tuning of the delay parameter. As above we take  and

and  . In this case, we find:

. In this case, we find:

| (24) |

|

(25) |

| (26) |

| (27) |

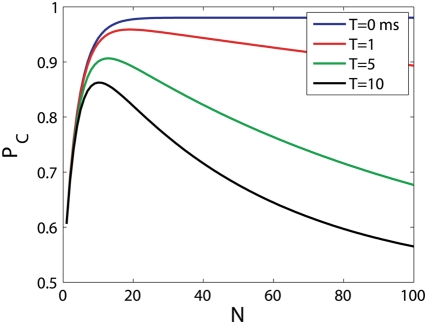

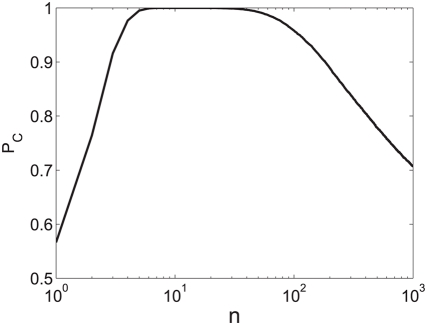

Figure 4 shows the

probability of correct discrimination as a function of  for different values of

for different values of  from top to bottom. For any positive

from top to bottom. For any positive  , the probability of correct discrimination,

, the probability of correct discrimination,  , decays to chance level,

, decays to chance level,  , exponentially fast with

, exponentially fast with  for large

for large  . This decay results from the fact that the probability of

not spiking in the time interval before time

. This decay results from the fact that the probability of

not spiking in the time interval before time  decays to zero exponentially with

decays to zero exponentially with  . For

. For  , the probability of correct response will saturate

exponentially to

, the probability of correct response will saturate

exponentially to  (compare with equation (9)) which can be high for low

baseline firing rate,

(compare with equation (9)) which can be high for low

baseline firing rate,  . For small

. For small  , there exists a region,

, there exists a region,  , in which

, in which  increases with

increases with  .

.

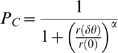

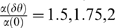

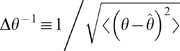

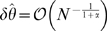

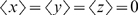

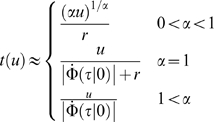

Figure 4. Effect of baseline firing on tWTA readout accuracy.

The probability of tWTA correct response,  , in the case of nonzero baseline firing is shown

as a function of the population size,

, in the case of nonzero baseline firing is shown

as a function of the population size,  , equation (24), for

, equation (24), for  from top to bottom. Parameters used for this graph

are:

from top to bottom. Parameters used for this graph

are:  ,

,  and

and  .

.

The temporal n Winners-Take-All (n-tWTA)

To overcome the detrimental effect of baseline firing we generalize the tWTA

to a family of readouts,  , that are determined by the subgroup of cells that fired

the first

, that are determined by the subgroup of cells that fired

the first  spikes. In a 2AFC competition between two homogeneous

columns, the

spikes. In a 2AFC competition between two homogeneous

columns, the  estimates the stimulus by the preferred direction of the

column that fired the first

estimates the stimulus by the preferred direction of the

column that fired the first  spikes. In the model of delayed step function response

PSTH, equation (23), spikes that are fired in the absolute delay period,

from time 0 to time

spikes. In the model of delayed step function response

PSTH, equation (23), spikes that are fired in the absolute delay period,

from time 0 to time  , are independent of the stimulus and hence carry no

information. The informative time of spiking is that from time

, are independent of the stimulus and hence carry no

information. The informative time of spiking is that from time  to time

to time  , where firing rates of the cells depend on the stimulus.

For a given population size,

, where firing rates of the cells depend on the stimulus.

For a given population size,  , the mean number of spikes fired during the absolute delay

time is

, the mean number of spikes fired during the absolute delay

time is  . During the informative period, an average of

. During the informative period, an average of  spikes is being fired by the informative group. Taking

spikes is being fired by the informative group. Taking  diminishes the detrimental effect of baseline firing and

conserves the essential information embedded in the temporal order of the

neural responses. Figure

5 shows the percent correct discrimination of the

diminishes the detrimental effect of baseline firing and

conserves the essential information embedded in the temporal order of the

neural responses. Figure

5 shows the percent correct discrimination of the  , as a function of

, as a function of  . In this case, the average number of baseline spikes fired

during the absolute delay time is

. In this case, the average number of baseline spikes fired

during the absolute delay time is  , and

, and  does indeed increase as

does indeed increase as  is increased from

is increased from  and to almost perfect discrimination at about

and to almost perfect discrimination at about  . During the informative period of spiking, an average of

. During the informative period of spiking, an average of  spikes are fired by the ‘correct’

group. As expected, the probability of correct discrimination deteriorates

for

spikes are fired by the ‘correct’

group. As expected, the probability of correct discrimination deteriorates

for  . In this example, the performance of the

. In this example, the performance of the  will decay to chance level in the limit of large

will decay to chance level in the limit of large  , since we did not incorporate any scale differences in the

firings of the two populations. Thus, a reasonable choice of

, since we did not incorporate any scale differences in the

firings of the two populations. Thus, a reasonable choice of  can eliminate the effect of baseline firing and greatly

improve the performance of the tWTA.

can eliminate the effect of baseline firing and greatly

improve the performance of the tWTA.

Figure 5. Performance of the  readout in a 2AFC discrimination task in a

two-column model.

readout in a 2AFC discrimination task in a

two-column model.

The probability of correct discrimination of the  readout is shown as function of

readout is shown as function of  . The probability of correct discrimination was

estimated by averaging over 105 realizations of the

neural stochastic response in an IHPP model for spike time

distribution as defined in equation (23) with:

. The probability of correct discrimination was

estimated by averaging over 105 realizations of the

neural stochastic response in an IHPP model for spike time

distribution as defined in equation (23) with:  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  .

.

Note that the optimal region for  , depends on the population size. For any fixed

, depends on the population size. For any fixed  , increasing the population size increases the number of

baseline spikes fired during the absolute delay period,

, increasing the population size increases the number of

baseline spikes fired during the absolute delay period,  . Hence, for

. Hence, for  the

the  performance will decay to chance level. An alternative

performance will decay to chance level. An alternative  generalization is to estimate the stimulus by the

preferred direction of the first single cell that fired

generalization is to estimate the stimulus by the

preferred direction of the first single cell that fired  spikes, see [2]. Results for

this later generalization are qualitatively similar to those of the former

in this model.

spikes, see [2]. Results for

this later generalization are qualitatively similar to those of the former

in this model.

tWTA Estimation Accuracy in a Hypercolumn Model

The model

We study the tWTA estimation accuracy in a hypercolumn model of  cells coding for an angular variable,

cells coding for an angular variable,  , such as the coding for the direction of motion of a

visual stimulus by MT cells. Each cell

, such as the coding for the direction of motion of a

visual stimulus by MT cells. Each cell  is characterized by its preferred direction

is characterized by its preferred direction  to which it responds fastest. Spike time distributions of

different cells are modeled by independent IHPPs with PSTH

to which it responds fastest. Spike time distributions of

different cells are modeled by independent IHPPs with PSTH  , for cell

, for cell  ,

,  .

.

The tWTA estimate of the stimulus is given by the preferred direction,  , of the cell

, of the cell  that fired the first spike

that fired the first spike

| (28) |

where  denotes the time of the first spike of cell

denotes the time of the first spike of cell  , following presentation of the stimulus. Throughout this

section, we quantify tWTA sensitivity by the inverse of the root-mean-square

estimation error,

, following presentation of the stimulus. Throughout this

section, we quantify tWTA sensitivity by the inverse of the root-mean-square

estimation error,  , where

, where  denotes averaging of

denotes averaging of  over the distribution of spike times for a given external

stimulus

over the distribution of spike times for a given external

stimulus  .

.

tWTA accuracy in the absence of correlations

The probability of the tWTA estimator to be  , is given by the probability that the first spike in the

population was fired by the cell with preferred direction

, is given by the probability that the first spike in the

population was fired by the cell with preferred direction  :

:

| (29) |

Empirical examples of first spike time tuning to an angular external stimulus

is shown for example in [1],[2]. Since tuning of

the delay parameter makes the dominant contribution to the tWTA accuracy

(see above), we now analyze the case of a delayed step function PSTH model

with stimulus-independent scale and shape parameters. Specifically, we take

the instantaneous firing rate of cell  with preferred direction

with preferred direction  , given that stimulus

, given that stimulus  was presented at time

was presented at time  , to be:

, to be:

| (30) |

This simple choice of PSTH does not limit the generality of

our results but rather clarifies the analysis such that our conclusions are

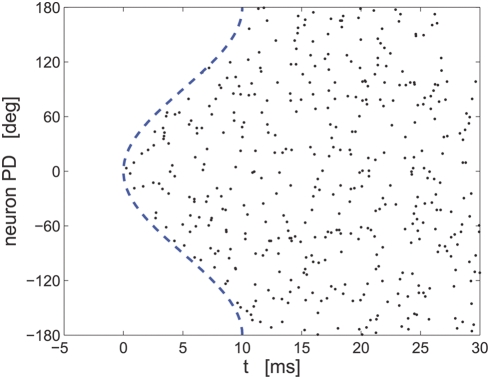

not obscured by non-relevant parameters. Figure 6 shows typical population

response to stimulus  . The dots on row

. The dots on row  show the spike times of a single cell with preferred

direction

show the spike times of a single cell with preferred

direction  . The dashed line shows the delay tuning function,

. The dashed line shows the delay tuning function,  , which yields the minimum possible spike time for each

preferred direction.

, which yields the minimum possible spike time for each

preferred direction.

Figure 6. Simulation of a hypercolumn population raster plot.

Spiking responses of 360 cells coding for an external stimulus  during a single trial are shown. Each line shows

the spike-times of a single cell. The cells are arranged according

to their preferred directions. Spike times of cell with preferred

direction

during a single trial are shown. Each line shows

the spike-times of a single cell. The cells are arranged according

to their preferred directions. Spike times of cell with preferred

direction  was modeled by an IHPP with PSTH

was modeled by an IHPP with PSTH  , where

, where  is the rate and the latency function is

is the rate and the latency function is  . The dashed line shows

. The dashed line shows  .

.

The delay tuning function,  , is assumed to be a periodic function of

, is assumed to be a periodic function of  . We further assume that the delay function,

. We further assume that the delay function,  , is a continuous, even function of its argument with a

single minimum at

, is a continuous, even function of its argument with a

single minimum at  . For cells with preferred directions close to the

stimulus, we can approximate the delay function by:

. For cells with preferred directions close to the

stimulus, we can approximate the delay function by:

| (31) |

where  characterizes the delay tuning function near its unique

minimum, for a smooth delay function

characterizes the delay tuning function near its unique

minimum, for a smooth delay function  , and

, and  is a constant in units of time. Since the tWTA is affected

only by the fastest cells, we can use the approximation of equation (31) to

describe the delay function of the entire hypercolumn, bearing in mind that

the likelihood of cells with preferred directions that are far removed from

the stimulus to affect the tWTA decays exponentially fast with

is a constant in units of time. Since the tWTA is affected

only by the fastest cells, we can use the approximation of equation (31) to

describe the delay function of the entire hypercolumn, bearing in mind that

the likelihood of cells with preferred directions that are far removed from

the stimulus to affect the tWTA decays exponentially fast with  .

.

Using the continuum limit approximation for the exponent in the right hand

side of equation (29), we evaluate the conditional probability density of

the estimation error of  and obtain:

and obtain:

| (32) |

In the limit of large  ,

,  is of

is of  in

in  for

for  and decays exponentially with

and decays exponentially with  for

for  . Hence, we obtain the following scaling law for the tWTA accuracy:

. Hence, we obtain the following scaling law for the tWTA accuracy:

| (33) |

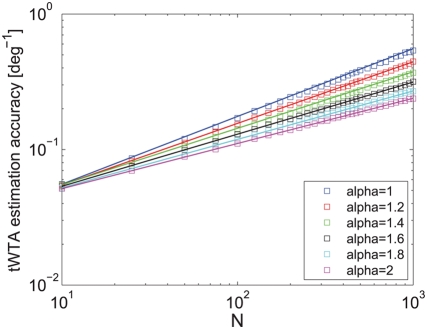

As in the two-column competition in the 2AFC paradigm, the

sensitivity of the tWTA readout in a hypercolumn model scales

algebraically fast with  , in the absence of noise correlations and in the limit of

low baseline firing. This fast scaling is in contrast to the slow

logarithmic scaling of the conventional rate-WTA readout accuracy wih the

population size [24]. Figure 7 shows tWTA sensitivity, in terms

of the inverse root mean square estimation error, as a function of the

population size in a hypercolumn model for

, in the absence of noise correlations and in the limit of

low baseline firing. This fast scaling is in contrast to the slow

logarithmic scaling of the conventional rate-WTA readout accuracy wih the

population size [24]. Figure 7 shows tWTA sensitivity, in terms

of the inverse root mean square estimation error, as a function of the

population size in a hypercolumn model for  from top to bottom. The open squares show numerical

estimation of the sensitivity as obtained by averaging tWTA error over

104 realizations of simulating the network stochastic

response. The solid lines show fits using the analytical result of equation

(33) with

from top to bottom. The open squares show numerical

estimation of the sensitivity as obtained by averaging tWTA error over

104 realizations of simulating the network stochastic

response. The solid lines show fits using the analytical result of equation

(33) with  from top to bottom.

from top to bottom.

Figure 7. Estimation accuracy of the tWTA readout in a hypercolumn model.

The accuracy of the tWTA readout, in terms of one over the squared

estimation error of estimating  , is plotted as a function of the population size,

in an IHPP hypercolumn population model, equation(30). The latency

tuning was modeled by

, is plotted as a function of the population size,

in an IHPP hypercolumn population model, equation(30). The latency

tuning was modeled by  (where

(where  is measured in radian) with

is measured in radian) with  from top to bottom. Accuracy was measured by

averaging the squared estimation error over 10,000 trials of

simulating the neuronal stochastic response (squares). The solid

lines show the analytical fit using equation (33).

from top to bottom. Accuracy was measured by

averaging the squared estimation error over 10,000 trials of

simulating the neuronal stochastic response (squares). The solid

lines show the analytical fit using equation (33).

Effect of correlations on the tWTA estimation accuracy

To model first spike time correlations in a hypercolumn, we write the spike times of each cell as the sum of correlated and uncorrelated parts

| (34) |

where the uncorrelated parts,  , are taken to be distributed according to an IHPP with a

PSTH

, are taken to be distributed according to an IHPP with a

PSTH  . For the sake of simplicity, we take

. For the sake of simplicity, we take  . The terms

. The terms  ,

,  and

and  are the correlated components of the spike times. The

are the correlated components of the spike times. The  term represent the effect of shared input to the entire

hypercolumn, whereas,

term represent the effect of shared input to the entire

hypercolumn, whereas,  and

and  represent the effect of shared input that is stronger for

columns that are functionally closer, i.e., have smaller preferred

directions difference. We assume that the correlated noise has zero means

represent the effect of shared input that is stronger for

columns that are functionally closer, i.e., have smaller preferred

directions difference. We assume that the correlated noise has zero means  and variance

and variance  and

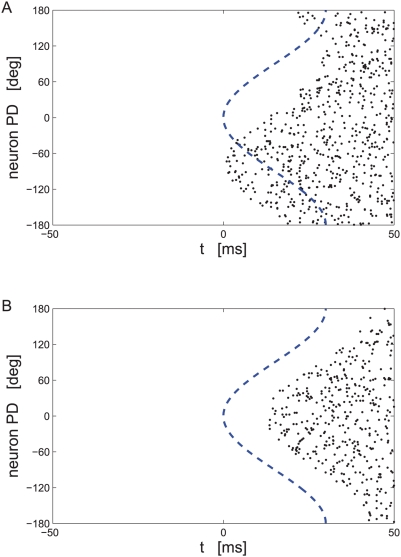

and  . Figure

8 shows typical realizations of the population response during a

single trial of presenting stimulus

. Figure

8 shows typical realizations of the population response during a

single trial of presenting stimulus  in the presence of noise correlations. In Figure 8b

in the presence of noise correlations. In Figure 8b

and

and  . The uniform correlations generates collective

fluctuations that shift the entire population response right (as in the

specific realization in the figure) and left of the dashed line that shows

. The uniform correlations generates collective

fluctuations that shift the entire population response right (as in the

specific realization in the figure) and left of the dashed line that shows  . Nevertheless, this fluctuation exists in a collective

mode of the neural responses that does not alter the order of firing and

hence does not affect tWTA accuracy. In Figure 8a

. Nevertheless, this fluctuation exists in a collective

mode of the neural responses that does not alter the order of firing and

hence does not affect tWTA accuracy. In Figure 8a

and

and  . In this case, the collective fluctuations shift the

response of the entire population up and down (as in the specific

realization in the figure). These fluctuations limit the accuracy in which

the tWTA can estimate the stimulus. In the limit of large

. In this case, the collective fluctuations shift the

response of the entire population up and down (as in the specific

realization in the figure). These fluctuations limit the accuracy in which

the tWTA can estimate the stimulus. In the limit of large  , the error is dominated by the correlated response.

Neglecting the uncorrelated part of the fluctuations, we obtain (see Methods):

, the error is dominated by the correlated response.

Neglecting the uncorrelated part of the fluctuations, we obtain (see Methods):

| (35) |

where  is measured in radians. Note that equation (35) takes the

form of a signal-to-noise ratio, where the signal is the modulation

amplitude of the delay function,

is measured in radians. Note that equation (35) takes the

form of a signal-to-noise ratio, where the signal is the modulation

amplitude of the delay function,  , and the noise is the component of collective noise

correlations that affect the tWTA estimation,

, and the noise is the component of collective noise

correlations that affect the tWTA estimation,  . The tWTA sensitivity, equation (35), is independent of

the collective fluctuations in the uniform direction,

. The tWTA sensitivity, equation (35), is independent of

the collective fluctuations in the uniform direction,  .

.

Figure 8. Simulation of a hypercolumn population raster in the presence of correlations.

Spiking responses of 360 cells coding for an external stimulus  during a single trial are shown. Every line shows

the spike-times of a single cell. The cells are arranged according

to their preferred directions. Spike times are distributed as

defined in the section ‘effect of correlations on tWTA

accuracy’, see equation (34), with

during a single trial are shown. Every line shows

the spike-times of a single cell. The cells are arranged according

to their preferred directions. Spike times are distributed as

defined in the section ‘effect of correlations on tWTA

accuracy’, see equation (34), with  and

and  . For the correlated part: (a)

. For the correlated part: (a)  ,

,  ; (b)

; (b)  ,

,  . The dashed line shows

. The dashed line shows  .

.

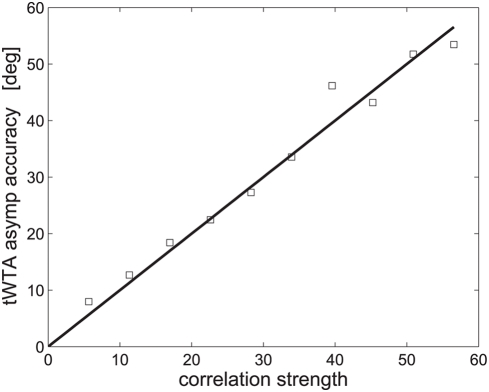

Figure 9 shows the

asymptotic accuracy of the tWTA as a function of the noise-to-signal ratio  . The solid line shows the analytical result of equation

(35) in the limit of large

. The solid line shows the analytical result of equation

(35) in the limit of large  . The open squares show numerical estimation of asymptotic

accuracy using a population of size

. The open squares show numerical estimation of asymptotic

accuracy using a population of size  cells. The finite size of the network limits the ability

of the numerical estimate to follow the analytic curve at high accuracy (low

noise levels). To compensate somewhat for this effect, an extremely high

firing rate was used in the simulations.

cells. The finite size of the network limits the ability

of the numerical estimate to follow the analytic curve at high accuracy (low

noise levels). To compensate somewhat for this effect, an extremely high

firing rate was used in the simulations.

Figure 9. Effect of correlations on the asymptotic tWTA estimation accuracy in a hypercolumn model.

tWTA accuracy, in terms of the root mean square estimation error,  , is shown as a function of the

correlations' strength,

, is shown as a function of the

correlations' strength,  , in a hypercolumn model, as defined in section

‘effect of correlations on the tWTA estimation

accuracy’, see equation (34). The solid line shows the

analytical asymptotic value, equation (35). Open squares show the

numerical estimation of the asymptotic value as calculated by

averaging the tWTA estimation error over 100 trials in a hypercolumn

model of

, in a hypercolumn model, as defined in section

‘effect of correlations on the tWTA estimation

accuracy’, see equation (34). The solid line shows the

analytical asymptotic value, equation (35). Open squares show the

numerical estimation of the asymptotic value as calculated by

averaging the tWTA estimation error over 100 trials in a hypercolumn

model of  cells. The latency function that was used was:

cells. The latency function that was used was:  . To minimize the effect of finite

. To minimize the effect of finite  , an extremely high firing rate of

, an extremely high firing rate of  was used in the IHPP simulations.

was used in the IHPP simulations.

Effect of baseline firing on the tWTA accuracy

The effect of nonzero baseline firing on tWTA estimation accuracy is studied

in the framework of a hypercolumn IHPP model with a delayed step function

PSTH. Specifically, we took the following PSTH for the response of cell  with preferred direction

with preferred direction  :

:

| (36) |

where  is the absolute delay,

is the absolute delay,  is the tuning of the delay parameter with

is the tuning of the delay parameter with  . For

. For  in the limit of large

in the limit of large  , we can approximate the probability of the tWTA estimator

to be

, we can approximate the probability of the tWTA estimator

to be  , equation (29), by:

, equation (29), by:

| (37) |

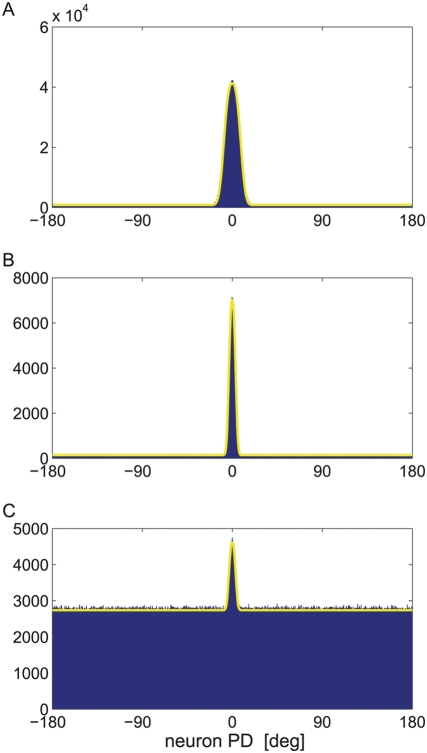

where  is a normalizing factor of the probability distribution.

Figure 10a and 10b

show histograms of tWTA estimations of stimulus

is a normalizing factor of the probability distribution.

Figure 10a and 10b

show histograms of tWTA estimations of stimulus  for

for  and

and  , respectively, in this model with

, respectively, in this model with  . The solid line shows the analytical approximation,

equation (37). The distribution is characterized by a narrow peak around

zero error, with a width that decreases to zero as

. The solid line shows the analytical approximation,

equation (37). The distribution is characterized by a narrow peak around

zero error, with a width that decreases to zero as  grows to infinity and a uniform probability for large

errors. The ratio of the peak distribution of the zero error (at

grows to infinity and a uniform probability for large

errors. The ratio of the peak distribution of the zero error (at  ) to the distribution of a specific large error is given by

) to the distribution of a specific large error is given by  . However, since the width of the peak decreases as

. However, since the width of the peak decreases as  increases (compare Figure 10a and 10b), the average squared

estimation error increases for large

increases (compare Figure 10a and 10b), the average squared

estimation error increases for large  , even in for

, even in for  , in contrast to the effect of baseline firing in the 2AFC,

where at

, in contrast to the effect of baseline firing in the 2AFC,

where at  the probability of correct response is an increasing

function of

the probability of correct response is an increasing

function of  . A hallmark of the tWTA readout is the high kurtosis of

the estimation error.

. A hallmark of the tWTA readout is the high kurtosis of

the estimation error.

Figure 10. Effect of baseline firing on the tWTA estimation in a hypercolumn model.

Histograms of tWTA estimation of stimulus  were obtained in a model of delayed step function

response to the stimulus, equation (36), with

were obtained in a model of delayed step function

response to the stimulus, equation (36), with  , and parameters:

, and parameters:  ,

,  and

and  . Population size was

. Population size was  in (a) and

in (a) and  in (b,c). Histograms were estimated using

106 repetitions in (a,b) and using 107

repetitions in (c). The solid lines are analytical approximations of

equation (37) in (a,b) and equation (38) in (c).

in (b,c). Histograms were estimated using

106 repetitions in (a,b) and using 107

repetitions in (c). The solid lines are analytical approximations of

equation (37) in (a,b) and equation (38) in (c).

In the case of  , using equation (37), one obtains

, using equation (37), one obtains

| (38) |

Hence, in this case the peak to base ratio of the

distribution is decreased and decays exponentially to zero with the product  . This effect is shown by the histogram of tWTA estimation

errors in Figure 10c

where we took

. This effect is shown by the histogram of tWTA estimation

errors in Figure 10c

where we took  and

and  (compare with Figure 10b where

(compare with Figure 10b where  and

and  ). The solid line shows the analytical approximation of

equation (38).

). The solid line shows the analytical approximation of

equation (38).

Discussion

At the time of the first spike, the tWTA is the ideal observer and, in the case of

angle estimation, it is also the population vector readout. If a decision must be

made at very short times, then the tWTA is the best readout. It is therefore

important that we know and understand the capabilities and limitation of this

readout. Scaling of the tWTA accuracy with the population size,  , can show a wide range of behaviors: from constant in

, can show a wide range of behaviors: from constant in  (equation 9), through logarithmic (equation 13) to algebraic

(equation 17). These different scaling regimes depend on fine details of the tuning

of the probability distribution of the first-spike-times or alternatively on the

initial rise of the PSTH response to the stimulus. In the generic case in which

scale, shape and delay parameters are all tuned to the stimulus, the tWTA accuracy

will increase algebraically with

(equation 9), through logarithmic (equation 13) to algebraic

(equation 17). These different scaling regimes depend on fine details of the tuning

of the probability distribution of the first-spike-times or alternatively on the

initial rise of the PSTH response to the stimulus. In the generic case in which

scale, shape and delay parameters are all tuned to the stimulus, the tWTA accuracy

will increase algebraically with  , in contrast to the expected logarithmic slow scaling of the

conventional rate-WTA readout [24]. Nevertheless, the tWTA is expected to show high

sensitivity to the inherent neuronal diversity at the level of single cell response

properties (see e.g., [30]). This sensitivity of the tWTA predicts

considerable subject-to-subject variability in psychophysical performance as well as

large fluctuations in the psychophysical accuracy for the same subject under

different stimuli conditions, such as discriminating

, in contrast to the expected logarithmic slow scaling of the

conventional rate-WTA readout [24]. Nevertheless, the tWTA is expected to show high

sensitivity to the inherent neuronal diversity at the level of single cell response

properties (see e.g., [30]). This sensitivity of the tWTA predicts

considerable subject-to-subject variability in psychophysical performance as well as

large fluctuations in the psychophysical accuracy for the same subject under

different stimuli conditions, such as discriminating  and

and  versus discriminating

versus discriminating  and

and  .

.

Noise correlations in the fluctuations of first-spike times of different cells have a

drastically detrimental effect on the tWTA accuracy, limiting the effective number

of degrees of freedom in the network and resulting in finite error levels, even in

the limit of large  , see e.g., equations (21), (22) and (35) and Figures 3 and 9. This effect is similar to that has been

reported in population coding literature [25]–[29],[31], and

depends on the correlations structure. Here we investigated the effect of

correlations that had simple spatial structure and no temporal structure. A

drastically detrimental effect on the tWTA accuracy is caused by neuronal response

covariance which generates collective fluctuation that resembles the

‘signal’, i.e., similar to the tuning of the delay parameter

(see Figure 8). For a detailed

discussion on the effects of correlations structure see [27]. The temporal

structure of response covariance may also have a considerable effect. For example,

if the correlations depend on the absolute time, in a manner that they are

negligible for small

, see e.g., equations (21), (22) and (35) and Figures 3 and 9. This effect is similar to that has been

reported in population coding literature [25]–[29],[31], and

depends on the correlations structure. Here we investigated the effect of

correlations that had simple spatial structure and no temporal structure. A

drastically detrimental effect on the tWTA accuracy is caused by neuronal response

covariance which generates collective fluctuation that resembles the

‘signal’, i.e., similar to the tuning of the delay parameter

(see Figure 8). For a detailed

discussion on the effects of correlations structure see [27]. The temporal

structure of response covariance may also have a considerable effect. For example,

if the correlations depend on the absolute time, in a manner that they are

negligible for small  and build up later in time, then they will not necessarily cause

saturation of the tWTA accuracy. However, better empirical understanding of first

spike time correlations is required to yield sufficient constraint for theoretical

study of this issue. It is important to emphasize that by correlations we mean first

spike time covariance of simultaneously recorded cells, in contrast

to other types of correlations [5].

and build up later in time, then they will not necessarily cause

saturation of the tWTA accuracy. However, better empirical understanding of first

spike time correlations is required to yield sufficient constraint for theoretical

study of this issue. It is important to emphasize that by correlations we mean first

spike time covariance of simultaneously recorded cells, in contrast

to other types of correlations [5].

In a 2AFC, task nonzero baseline firing has a twofold detrimental effect on the tWTA

accuracy. The first is in the case in which the onset of the tWTA readout precedes

the stimulus response of the fastest cell in the entire population,  . In this case, the tWTA accuracy will decrease as

. In this case, the tWTA accuracy will decrease as  is increased beyond some optimal value

is increased beyond some optimal value  . This effect can be minimized by obtaining a more accurate

estimate for the minimal response time of the cells in the population, i.e.,

effectively decreasing

. This effect can be minimized by obtaining a more accurate

estimate for the minimal response time of the cells in the population, i.e.,

effectively decreasing  [5]. The

second effect is a saturating effect, which limits the maximal accuracy that can be

obtained by the tWTA,

[5]. The

second effect is a saturating effect, which limits the maximal accuracy that can be

obtained by the tWTA,  , even for

, even for  . Note that, although

. Note that, although  is less than 1, psychophysical accuracy is also finite. The value

of

is less than 1, psychophysical accuracy is also finite. The value

of  can be rather high in cases in which the baseline firing is small

relative to the stimulus response. These effects can be decreased for any given

can be rather high in cases in which the baseline firing is small

relative to the stimulus response. These effects can be decreased for any given  by using a generalized

by using a generalized  readout that makes a decision according to the population that

fired the first n spikes, see Figure 5. Nevertheless, for any given fixed value

of

readout that makes a decision according to the population that

fired the first n spikes, see Figure 5. Nevertheless, for any given fixed value

of  , increasing the population size,

, increasing the population size,  , will decrease the

, will decrease the  performance to chance level, for

performance to chance level, for  . Hence, for fast decisions there are advantages to reading out the

responses of small neuronal populations rather than larger populations.

. Hence, for fast decisions there are advantages to reading out the

responses of small neuronal populations rather than larger populations.

Baseline firing has similar detrimental effects on the tWTA readout in estimation

tasks (see Figure 10). A

hallmark of the tWTA readout that can serve as a prediction is its high kurtosis.

There are various ways to generalize the tWTA to use more than one spike in order to

overcome the detrimental effect of baseline firing. One option is that readout is

determined by the preferred direction of the single cell that fired the first  spikes. An alternative generalization is to define the readout by

a ‘vote’ of cells that fired the first

spikes. An alternative generalization is to define the readout by

a ‘vote’ of cells that fired the first  spikes in the population. In the later case, different weights may

be assigned to the votes. The utility of the different possible generalizations is

expected to depend largely on the structure of the correlations in the neuronal

initial dynamic response to the stimulus.

spikes in the population. In the later case, different weights may

be assigned to the votes. The utility of the different possible generalizations is

expected to depend largely on the structure of the correlations in the neuronal

initial dynamic response to the stimulus.

In a series of highly influential papers, Thorpe and colleagues (see e.g., [12],[14]), have highlighted

the possible role of spike latency as primary source of information in the CNS and

have shown, for example, how an image falling on the retina could be reconstructed

from a spike latency (see also work of [15]). In the context of

this work, their readout could be thought of as a specific choice for the  generalization. Here, we presented a systematic investigation of

the tWTA accuracy that allows for comparison with psychophysical accuracy; hence,

enables testing of the hypothesis that tWTA is actually used by the CNS. In

addition, our analysis provides a framework that allows for the understanding and

the investigation of the effects of correlations and baseline firing on the tWTA

accuracy.

generalization. Here, we presented a systematic investigation of

the tWTA accuracy that allows for comparison with psychophysical accuracy; hence,

enables testing of the hypothesis that tWTA is actually used by the CNS. In

addition, our analysis provides a framework that allows for the understanding and

the investigation of the effects of correlations and baseline firing on the tWTA

accuracy.

Neural network implementations of the tWTA

Considerable theoretical effort has been devoted to the investigation of

neural network models that can implement the conventional rate-WTA [32]–[43]. These studies

have focused on inputs that are constant in time and differ by their scale.

However, it has been acknowledged that the temporal structure of the inputs

may have a considerable effect on the WTA readout [43]. This effect

shows the sensitivity of existing rate-WTA neural network models to the

order of firing and demonstrates the capability of neural networks to

implement a tWTA computation. Indeed one can imagine the responses of the

(assumed excitatory) hypercolumn network that code for the external stimulus

by their spike time latency, being input to a  readout layer of laterally all to all connected inhibitory

neurons. Once, input to a inhibitory cell crosses firing threshold of

readout layer of laterally all to all connected inhibitory

neurons. Once, input to a inhibitory cell crosses firing threshold of  excitatory post synaptic potential, it will fire and

silence the rest of the network. Investigation of various neural network

implementations, their limitations and deviations from the mathematically

ideal tWTA and the computational consequences of these deviations if exist

is beyond the scope of the current work and will be addressed elsewhere.

excitatory post synaptic potential, it will fire and

silence the rest of the network. Investigation of various neural network

implementations, their limitations and deviations from the mathematically

ideal tWTA and the computational consequences of these deviations if exist

is beyond the scope of the current work and will be addressed elsewhere.

The neural code

To what extent does the CNS use the tWTA as a readout mechanism? Readout

mechanisms used by the CNS are necessarily dynamic processes that may

involve inhibition and hence generate WTA-like competition between inputs

from different columns. If fast decisions between a small number of

alternatives are required, then the tWTA can provide the correct result with

high probability. In such a case, we predict that the readout will be

determined by competition between relatively small groups

of cells rather than by the entire cell population that responds to the

stimulus so as to decrease the effect of baseline firing. Such decisions

include, for example, estimation of the direction of motion of a visual

stimulus at a low resolution of 45°. However, for discrimination

between many alternatives the tWTA is limited by the baseline firing. Why is

this task more sensitive to baseline firing? Consider an example in which

estimation of the direction of motion of a visual stimulus is required at a

precision of 3.6°. For this angular resolution, a population of at

least  cells is needed. Let us assume that at the stimulus onset

the ‘correct’ cell fires at a rate of

cells is needed. Let us assume that at the stimulus onset

the ‘correct’ cell fires at a rate of  while the rest of the population fires at a baseline rate

of

while the rest of the population fires at a baseline rate

of  . During the first

. During the first  of stimulus presentation, the

‘correct’ cell will fire an average of

of stimulus presentation, the

‘correct’ cell will fire an average of  spike, while the rest of the cells will fire an average of

spike, while the rest of the cells will fire an average of  spikes; thus, the tWTA is expected to err in more than

3.6° in about 50% of the cases. Hence, fine estimation

tasks cannot rely on the single first spike, and our theory

predicts that in these cases the first

spikes; thus, the tWTA is expected to err in more than

3.6° in about 50% of the cases. Hence, fine estimation

tasks cannot rely on the single first spike, and our theory

predicts that in these cases the first  spikes must be considered where

spikes must be considered where  should be larger than the average number of baseline

spikes. How should the

should be larger than the average number of baseline

spikes. How should the  combine the information from the first

combine the information from the first  spikes? The answer to this question depends on the

temporal structure of correlations, fine details of the PSTH, and on our

assumptions on the computational capabilities of this readout and is beyond

the scope of the current paper. The current work provides the essential

framework for addressing this question. To further study the hypothesis that

the CNS actually uses the tWTA better empirical understanding of the tuning

of first spike time distribution to the stimulus, baseline firing, and the

spatial and temporal structure of noise correlations is required.

spikes? The answer to this question depends on the

temporal structure of correlations, fine details of the PSTH, and on our

assumptions on the computational capabilities of this readout and is beyond

the scope of the current paper. The current work provides the essential

framework for addressing this question. To further study the hypothesis that

the CNS actually uses the tWTA better empirical understanding of the tuning

of first spike time distribution to the stimulus, baseline firing, and the

spatial and temporal structure of noise correlations is required.

Methods