Abstract

Objective

To determine whether an acupuncture technique specially developed for a surgical oncology population (intervention) reduces pain or analgesic use after thoracotomy compared to a sham acupuncture technique (control).

Methods

One hundred and sixty two cancer patients undergoing thoracotomy were randomized to group A) preoperative implantation of small intradermal needles which were retained for 4 weeks or B) preoperative placement of sham needles at the same schedule. Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) of pain and total opioid use we evaluated during the in-patient stay; Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) and Medication Quantification Scale (MQS) were evaluated after discharge up to 3 months after the surgery.

Results

The principal analysis, a comparison of BPI pain intensity scores at the 30 day follow-up, showed no significant difference between the intervention and control group. Pain scores were marginally higher in the intervention group 0.05 (95% C.I.: 0.74, -0.64; p=0.9). There were also no statistically significant differences between groups for secondary endpoints, including chronic pain assessments at 60 and 90 days, in-patient pain, and medication use in hospital and after discharge.

Conclusion

A special acupuncture technique as provided in this study did not reduce pain or use of pain medication after thoracotomy more than a sham technique.

Keywords: Acupuncture, thoracotomy, pain, sham acupuncture

Introduction

Thoracotomy is associated with high levels pain in the immediate post-operative period (acute post-thoracotomy pain). Some patients experience continuing pain lasting greater than 60 days, termed post-thoracotomy pain syndrome (PTPS or chronic post-thoracotomy pain). This pain can persist for years. In one study, about 30% of patients still experience pain up to 4 to 5 years after surgery (1). Trauma to the intercostal nerve is the most likely cause. The pain has neuropathic and nonneuropathic components. Post-thoracotomy pain causes distress, impediment of pulmonary function and mobility, leading to increased post-operative morbidity. Acute pain is managed with one or more of a number of strategies including PCA, epidural, paravertebral and other interventions. The treatment of chronic post-thoracotomy pain is more difficult (2)(3)(1).

Acupuncture is a complementary medicine modality that originated in traditional Chinese medicine practices (4). Clinical studies have documented its benefit in the management of certain painful conditions such as joint osteoarthritis (5), pain during labor (6), lower back pain (7), pain post oral surgery (8) and pain post abdominal surgery (9). The Kotani study (9) is especially relevant to post-thoracotomy pain. In this randomized controlled study a special acupuncture technique – insertion of intradermal needles preoperatively, significantly reduced pain score in the first two days after operation, when compared to a sham technique (9). This technique, could be more applicable in Western medicine practice than is traditional acupuncture, because patients can be sent home with indwelling needles, obviating the need for repeated hospital visits to receive acupuncture treatment.

Inspired by the Kotani study, we conducted and published a pilot study to demonstrate the feasibility of using intradermal acupuncture needles to treat post-thoracotomy pain (10). Here we report data from a subsequent randomized controlled trial to determine whether placement of intradermal acupuncture needles are superior to sham technique in the treatment of acute and chronic post-thoracotomy pain.

Methods

Study Design

This was a randomized, sham- controlled, subject-blinded trial. The duration of the intervention was 4 weeks.

Study Subjects

Informed consent was obtained before subject enrollment according to a clinical trial protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). Recruitment took place between February 2005 and January 2007.

All study participants were cancer patients age 18 years or older scheduled for unilateral thoracotomy at MSKCC. Patients meeting were excluded if their surgery involved hemiclamshell, clamshell, extrapleural approach, chest wall involvement or esophagectomy, as these more extensive procedures have a higher risk of complications. Patients who had received acupuncture treatment in the previous six weeks also were ineligible, to discount any persisting effect of acupuncture. Additional ineligibility factors included patients with platelets <20,000 or INR >2.5 or ANC <0.5, known cardiac conditions with high or moderate risk of endocarditis as defined by the American Heart Association (11) because the intradermal acupuncture needles remained in the skin for up to 4 weeks, inability to remove the needles without assistance or who had no home assistance and were unable or unwilling to return to the hospital if they elected to remove the needles prior to their post-discharge visit.

Randomization

Randomization was stratified by epidural anesthesia (yes/no) using blocks of random length, and accomplished using a secure, password protected institutional computer system, stratified by permuted blocks of random length. The system is designed to ensure that allocation cannot be guessed before a patient is registered nor changed afterwards, thus ensuring full allocation concealment. After subject registration and randomization, a research assistant who was otherwise unconnected with the trial accessed allocation and telephoned the acupuncturist with details of allocation. Patients were blind to study group; the acupuncturists and the designated research assistant were aware of which patients received true and which sham treatment.

Intervention

Within two hours prior to surgery, following placement of an epidural catheter but before induction of anesthesia, 9 small intradermal acupuncture needles were inserted in a sterile fashion on each side of the spine corresponding to the BL-12 to BL-19 acupuncture points and an extra point (Wei Guan Xia Shu) (covering the T2 to T9 dermatomes). The BL points are points comparable to those demonstrated to have anti-nociceptive effects in prior trial of abdominal surgery (T9-L3 dermatomes) (9) but located more rostral. In addition, one stud was placed in each leg (ST-36 point) and one in each auricle (Shenmen point). ST-36 and Shenmen are commonly used to treat pain.

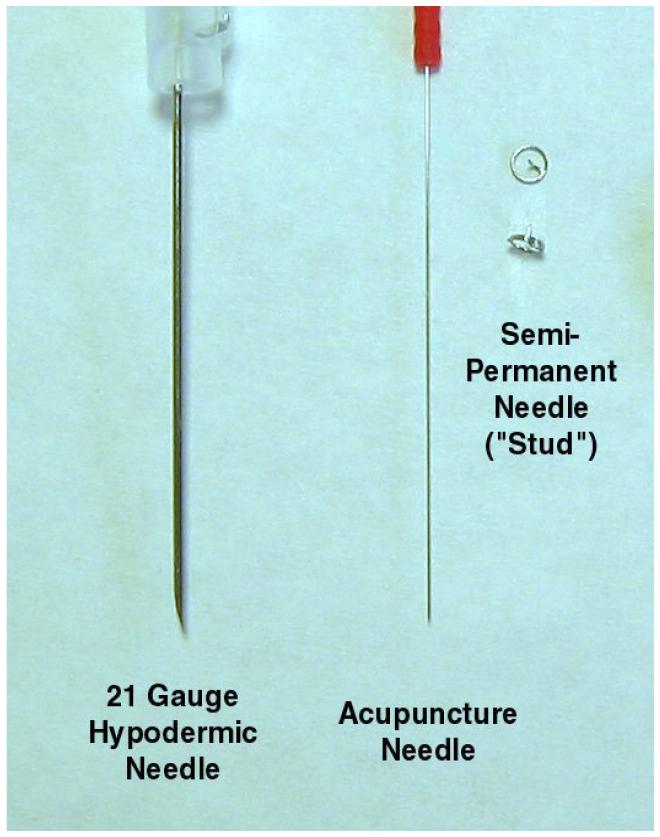

The sterile intradermal needles, which we term “studs,” are ∼1.5mm long with a diameter of ∼ 0.2mm. They have the appearance of miniature thumbtacks. Upon placement, the short needle penetrates the epidermis and provides stimulation whereas the ring at the end of the stud (4 mm in diameter) keeps it from entering the skin completely and being lost in the subcutaneous tissue(Figure 1). The needles are shorter than what was used in the Kotani study (1.5 mm vs 5 mm). The studs were covered with Tegaderm (3M) transparent films which is impermeable to micro-organisms but permeable to both water vapor and air. Pre-operative acupuncture took place in the MSKCC Pre-surgical Center. The studs were exchanged with new ones one week after the initial placement. Those at ST-36 and Shenmen were removed one week later. Those at the back were removed 3 weeks later. The total period of acupuncture intervention was 4 weeks. We believed that a long period of stimulation would be required given the severity of thoracotomy pain.

Figure 1.

Acupuncture needles

Treatment in the control group was identical to that for the true acupuncture group with the following exceptions. Studs placed in the back were dummy studs with a ring but no needle. The back studs were placed halfway between the upper and lower border of spinous processes T2 to T10, approximately 0.5 cun (∼1.25cm) from the spine. The leg studs were placed at 2 cun (∼5cm) posterior to GB-34 on the posterior of the lower leg. No studs were placed in the ear. Instead sham studs were placed on the anterior arm, 3 cun (∼ 5cm) proximal and 3 cun (∼ 5cm) medial to the midpoint of the antecubital crease. There are no known acupuncture points near these two locations. Sham studs were placed at different points to prevent tactile stimulation at acupuncture points.

Evaluation

The primary endpoint was Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) pain intensity score at day 30 post-operation. The BPI is a validated pain measurement tool that measures both the intensity of pain (sensory dimension) and interference of pain in the patient’s life (reactive dimension)(12). On the BPI, mild pain is defined as a worst pain score of 1 - 4, moderate pain is defined as a worst pain score of 5 - 6, and severe pain is defined as a worst pain score of 7 – 10..Secondary endpoints included BPI, a 0–10 Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) of pain, total opioid use and Medication Quantification Scale (MQS) at 1, 2 and 4 weeks (for acute post-thoracotomy pain), and at 2 and 3 months post-operatively (for chronic post-thoracotomy pain). MQS is a reliable, valid and sensitive method of assessing medication use in chronic pain patients, in which drugs are scaled relative to their recommended daily doses (13).

Statistical methods

Sample size calculations were based on data from our pilot study (10). The mean BPI pain score at the 30 day follow-up in the pilot study was 2.7 with a standard deviation of 1.48. As a conservative measure, we took the upper 75th centile of the standard deviation (1.63). Although our analysis was adjusted for baseline score, we did not incorporate any further correction to the standard deviation on the assumption of a low correlation between baseline and follow-up score. We set a minimum clinically significant difference of 25%, giving a hypothesized score in the control group close to 3.6. With a 5% alpha and a power of 80%, 52 evaluable patients per group were required.

The principal analysis was a comparison of BPI pain intensity scores at the 30 day follow-up. Secondary analyses were BPI total and pain interference at 30 days; BPI scores for post-discharge, 60 and 90 days; area-under-the-curve for NRS pain at rest, on movement and on coughing for the first five days post-surgery; total opiate use, in mg oral morphine equivalents, and non-opiate MQS in first five days after surgery. All analyses were conducted by analysis of covariance with the randomization stratum (epidural anesthesia) as covariate. In the BPI analyses, baseline BPI score was used as a covariate. Baseline BPI scores were missing for 15 patients. In patients who did provide baseline BPI data, scores were low, and were not strongly correlated with other variables. Accordingly, we used simple mean imputation to obtain a score to enter into the model. Patients were analyzed in their randomized groups, regardless of treatment assignment. There were, however, two exceptions to the intention-to-treat principle: patients who did not receive surgery or those who were judged by a blinded investigator to have had no chance of receiving acupuncture, were excluded from analysis. An example of the latter would be a patient whose surgery was moved two hours forward due to a change in scheduling, such that the acupuncturist arrived after the patient had sent to the operating room. Sensitivity analysis was planned to account for missing posttreatment data but this was found not to be warranted. All analyses were conducted using Stata 9.2 (Stata Corp., College Station, Tx).

Results

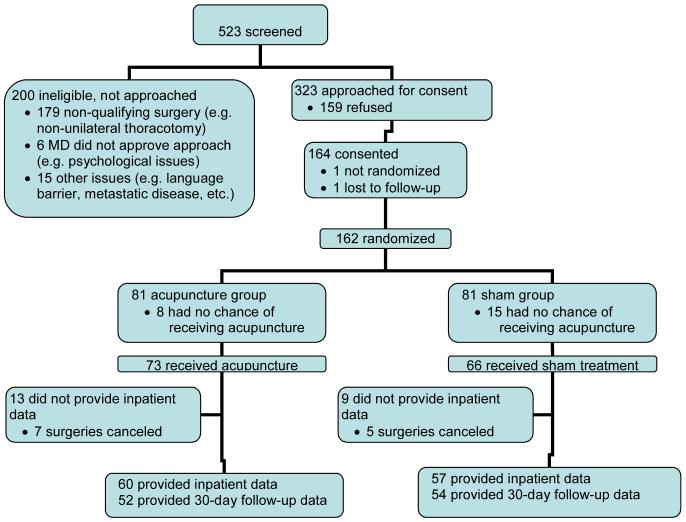

Participant flow through the trial is shown in Figure 2. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study subjects. Acupuncture and sham groups are well balanced for age, gender, use of epidural analgesia and operation type. About 80% of participants received epidural analgesia. The majority of patients (118, 72%) were accrued by three of six surgeons with all surgeons accruing equal numbers of patients to each arm of the study.

Figure 2.

Participant Flow (Description and Number of Subjects)

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study subjects who provided data for the primary endpoint

| Allocation | Acupuncture | Sham |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 52 | 54 |

| Age: Median (Interquartile range) |

65 (58, 72) | 63 (57, 70) |

| Female | 24 (46%) | 30 (56%) |

| Epidural | 42 (81%) | 43 (80%) |

| Operation | ||

| Full | 3 (6%) | 6 (11%) |

| Partial | 49 (94%) | 48 (89%) |

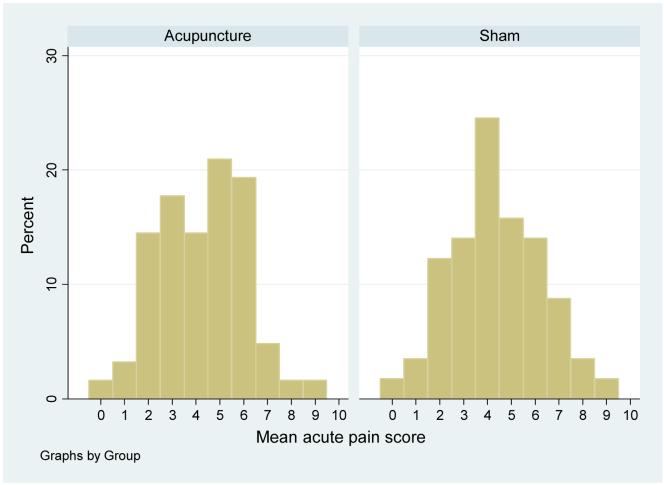

Pain scores during follow-up, as measured by the Brief Pain Inventory at Day 10 and Day 30 (for “acute post-thoracotomy pain”), as well as Day 60 and Day 90 (for ”chronic post-thoracotomy pain”), are shown in Table 2. In the primary analysis (Day 30), pain scores were marginally higher in the acupuncture group 0.05 (95% C.I.: 0.74, -0.64; p=0.9). For no BPI domain at any follow-up were there significant differences between groups. Moreover, the 95% confidence intervals rarely include a difference in favor of acupuncture greater than 1 point. Pain scores during hospitalization, as recorded by numerical rating scales, are shown in Table 3. Again, there are no statistically significant differences between groups. Figure 3 shows acute pain score, averaged for the three domains, separately for the acupuncture and sham groups.

Table 2. Brief pain inventory scores throughout the trial.

(Data are given as mean (SD). The pre-specified primary analysis is bolded.)

| Domain | Baseline | Day 10 | Day 30 | Day 60 | Day 90 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acp | Sham | Acp | Sham | Diff.* | p | Acp | Sham | Diff.* | p | Acp | Sham | Diff.* | p | Acp | Sham | Diff.* | p | |

| Total | n=47: 0.79 (1.54) |

n=43: 1.19 (2.07) |

n=44: 2.95 (1.96) |

n=47: 3.20 (1.80) |

0.21 (1.00, -0.58) |

0.6 | n=52: 2.45 (2.02) |

n=54: 2.64 (1.95) |

0.13 (0.89, -0.64) |

0.7 | n=42: 1.28 (1.50) |

n=44: 1.95 (2.27) |

0.48 (1.24, -0.28) |

0.2 | n=44: 1.54 (1.58) |

n=45: 1.49 (2.03) |

-0.12 (0.56, -0.81) |

0.7 |

| Intensity | 1.04 (1.76) |

1.26 (2.04) |

3.15 (2.05) |

3.01 (1.46) |

-0.18 (0.56, -0.92) |

0.6 |

2.47 (1.95) |

2.48 (1.75) |

-0.05 (0.64, -0.74) |

0.9 | 1.26 (1.35) |

1.79 (1.89) |

0.46 (1.12, -0.20) |

0.17 | 1.59 (1.69) |

1.69 (2.12) |

0.11 (0.91, -0.69) |

0.8 |

| Interference | 0.64 (1.66) |

1.14 (2.17) |

2.82 (2.29) |

3.32 (2.19) |

0.46 (1.42, -0.49) |

0.3 | 2.43 (2.33) |

2.73 (2.27) |

0.26 (1.15, -0.64) |

0.6 | 1.29 (1.70) |

2.05 (2.56) |

0.49 (1.35, -0.37) |

0.3 | 1.50 (1.68) |

1.37 (2.33) |

-0.28 (0.46, -1.01) |

0.5 |

Difference between groups: positive value indicates lower pain in acupuncture group. Values in brackets are the 95% C.I.

Table 3. Numerical rating scale scores during the in-patient stay.

Data are given as mean (SD).

| Variable | Acupuncture (n=62) | Sham(n=57) | Difference* | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain at rest | 2.53 (1.86) | 2.96 (2.00) | 0.44 (-0.26, 1.13) | 0.2 |

| Pain on movement | 4.53 (2.10) | 4.40 (2.03) | -0.13 (-0.86, 0.61) | 0.7 |

| Pain while coughing | 5.71 (2.37) | 5.76 (2.41) | 0.05 (-0.80, 0.89) | 0.9 |

Difference between groups: positive value indicates lower pain in acupuncture group. Values in brackets are the 95% C.I.

Figure 3.

Histogram of acute pain scores by group.

Whether the patients received epidural or not did not appear to impact the results. All analyses were conducted by analysis of covariance with the randomization stratum (epidural anesthesia) as covariate, meaning that the analysis was done for those with epidural, for non-epidural, and for the combined population. There were no significant differences in the results among these three subgroups.

Nineteen patients (32%) in the control group received antiemetics compared to 23 (37%) patients in the acupuncture group (odds ratio for acupuncture of 1.25; 95% C.I. 0.59, 2.65; p=0.6). Pain medication use is described in table 4. Medication use was similar in each group. Blinding was adequate: of patients who expressed a belief about assignment in response to questions about blinding, 14 of 26 in the acupuncture group and 16 of 27 in the sham guessed correctly.

Table 4. Medication scores.

Data are given as mean (SD)

| Variable | Acupuncture | Sham | Difference* | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication quantification scale | n=63: 10.37 (6.96) | n=59: 11.14 (7.78) | 0.76 (-1.88, 3.40) | 0.6 |

| Morphine equivalents (mg) | n=63: 1530 (1172) | n=59: 1563 (1093) | 28 (-330, 386) | 0.9 |

Difference between groups: positive value indicates lower pain in acupuncture group. Values in brackets are the 95% C.I.

Discussion

Post-thoracotomy pain is a common problem after thoracic surgery. In some patients the pain persists for months or even years after surgery. In addition to pharmacologic and behavioral therapies, acupuncture offers a potential therapeutic option, given previous reports of its benefit in treating other types of post-operative pain. However, traditional acupuncture techniques require multiple treatments by the acupuncturist, which may hinder its acceptance in Western clinical practice. In this study we evaluated a special acupuncture technique - perioperative stimulation with implanted small intradermal acupuncture needles -that requires only two encounters with the acupuncturist. A similar technique was previously reported to reduce pain after abdominal surgery. However, in this study we found that this particular acupuncture technique did not significantly reduce acute or chronic post-thoracotomy pain, nor did it reduce the use of pain medicine, when compared to a sham technique.

There could be several explanations for this result. First, acupuncture may be ineffective for post-thoracotomy pain. Yet several previous controlled studies showed that acupuncture provided analgesia after abdominal surgery (14) (15) and thoracic surgery (16). A second possible explanation is that the acupuncture technique used in this study may not deliver strong enough stimulation to produce analgesic effects.

A recently published randomized, sham controlled study of acupuncture did show reduction of pain medicine requirements in post-thoracotomy patients. In that study electrical stimulation was applied to acupuncture needles and treatment was given twice daily for 7 postoperative days. When compared with sham acupuncture, there was no statistically significant difference of pain scores between the two groups, but the cumulative dose of PCA morphine used on postoperative day 2 was significantly lower in the electroacupuncture group (16). Our intervention regimen provided less intense stimulation (implanted intradermal needles versus electroacupuncture) but over a longer period of time (4 weeks versus 1 week).

Our rationale for selecting this technique was based on two factors. First, a previous randomized controlled trial reported that preoperative intradermal acupuncture studs reduced postoperative pain, nausea and vomiting, analgesic requirement, and sympathoadrenal responses (9). This technique was thought to deliver less intense but longer-lasting stimulation, possibly more effective in the treatment of persisting postoperative pain (9). Second, traditional acupuncture regimens require frequent treatments by acupuncturists. In the current Western medical practice setting, this presents an access barrier, as many patients do not have the time or financial resources to return often for treatment. If the studs technique applied in this study were efficacious, we believed that it would find a wider application as it requires only preoperative placement of acupuncture needle and one postoperative visit to replace the needles.

Because in this study perioperative stimulation with intradermal acupuncture studs failed to show significant reduction in pain or in use of postoperative analgesic medication, we conclude that the acupuncture technique as provided in this study can not be recommended for the prevention or treatment of post-thoracotomy pain. The results of our study may not be generalizable to other acupuncture techniques or to other types of pain. Further research should apply a more intensive acupuncture regimen similar to those reported previously (16).

Acknowledgment

We appreciate the contributions of Drs. Kenneth Cubert and Neil Patel from the Department of Anesthesiology, and thank Jennifer Lee, Cheryl Co, Erika Greenidge, Kristine Brown, Elizabeth Seidler (Research Study Assistants) and Yi Chan, Chunyan Teng, K. Simon Yeung, Yi Lily Zhang, Carole Johnson, Sally Kao, Sissi Le (acupuncturists) for their work. The study was supported by National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine grant AT002989.

Research Support The study was supported by National Cancer for Complementary and Alternative Medicine grant AT002989.

Abbreviations

- ANC

absolute neutrophil count

- BPI

Brief Pain Inventory

- INR

International Normalization Ratio

- MQS

medication quantification scale

- MSKCC

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

- NRS

numerical rating scale

- PCA

patient controlled analgesia

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Prior Presentation: This study has not been presented elsewhere.

Ultramini-Abstract: A special acupuncture technique was evaluated for the treatment of post-thoracotomy pain. Small intradermal acupuncture needles implanted immediately before operation and retained for 4 weeks did not reduce pain intensity score at 30 days post-operation when compared to a sham technique.

References

- 1.Karmakar MK, Ho AM. Postthoracotomy pain syndrome. Thorac Surg Clin. 2004 Aug;14(3):345–52. doi: 10.1016/S1547-4127(04)00022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz J, Jackson M, Kavanagh BP, Sandler AN. Acute pain after thoracic surgery predicts long-term post-thoracotomy pain. Clin J Pain. 1996 Mar;12(1):50–5. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199603000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koehler RP, Keenan RJ. Management of postthoracotomy pain: acute and chronic. Thorac Surg Clin. 2006 Aug;16(3):287–97. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaptchuk TJ. Acupuncture: theory, efficacy, and practice. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Mar 5;136(5):374–83. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwon YD, Pittler MH, Ernst E. Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006 Nov;45(11):1331–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith CA, Collins CT, Cyna AM, Crowther CA. Complementary and alternative therapies for pain management in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD003521. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003521.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manheimer E, White A, Berman B, Forys K, Ernst E. Meta-analysis: acupuncture for low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2005 Apr 19;142(8):651–63. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-8-200504190-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lao L, Bergman S, Hamilton GR, Langenberg P, Berman B. Evaluation of acupuncture for pain control after oral surgery: a placebo-controlled trial. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999 May;125(5):567–72. doi: 10.1001/archotol.125.5.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kotani N, Hashimoto H, Sato Y, Sessler DI, Yoshioka H, Kitayama M, et al. Preoperative intradermal acupuncture reduces postoperative pain, nausea and vomiting, analgesic requirement, and sympathoadrenal responses. Anesthesiology. 2001 Aug;95(2):349–56. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200108000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vickers AJ, Rusch VW, Malhotra VT, Downey RJ, Cassileth BR. Acupuncture is a feasible treatment for post-thoracotomy pain: results of a prospective pilot trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2006;6:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dajani AS, Taubert KA, Wilson W, Bolger AF, Bayer A, Ferrieri P, et al. Prevention of bacterial endocarditis. Recommendations by the American Heart Association. Circulation. 1997 Jul 1;96(1):358–66. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.1.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994 Mar;23(2):129–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steedman Masters S, Middaugh SJ, Kee WG, Carson DS, Harden RN, Miller MC. Chronic-pain medications: equivalence levels and method of quantifying usage. Clin J Pain. 1992 Sep;8(3):204–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin JG, Lo MW, Wen YR, Hsieh CL, Tsai SK, Sun WZ. The effect of high and low frequency electroacupuncture in pain after lower abdominal surgery. Pain. 2002 Oct;99(3):509–14. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00261-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sim CK, Xu PC, Pua HL, Zhang G, Lee TL. Effects of electroacupuncture on intraoperative and postoperative analgesic requirement. Acupunct Med. 2002 Aug;20(23):56–65. doi: 10.1136/aim.20.2-3.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong RH, Lee TW, Sihoe AD, Wan IY, Ng CS, Chan SK, et al. Analgesic effect of electroacupuncture in postthoracotomy pain: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006 Jun;81(6):2031–6. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]