Abstract

We evaluated the influence of psychotherapy attendance on treatment outcome in 90 dually (cocaine and heroin) dependent outpatients who completed 70 days of a controlled clinical trial of sublingual buprenorphine (16 mg, 8 mg, or 2 mg daily, or 16 mg every other day) plus weekly individual standardized interpersonal cognitive psychotherapy. Treatment outcome was evaluated by quantitative urine benzoylecgonine (BZE) and morphine levels (log-transformed), performed three times per week. Repeated-measures linear regression was used to assess the effects of psychotherapy attendance (percent of visits kept), medication group, and study week on urine drug metabolite levels. Mean psychotherapy attendance was 71% of scheduled visits. Higher psychotherapy attendance was associated with lower urine BZE levels, and this association grew more pronounced as the study progressed (p = 0.04). The inverse relationship between psychotherapy attendance and urine morphine levels varied by medication group, being most pronounced for subjects receiving 16 mg every other day (p = 0.02). These results suggest that psychotherapy can improve the outcome of buprenorphine maintenance treatment for patients with dual (cocaine and opioid) dependence.

Keywords: Buprenorphine, Cocaine, Heroin, Dual dependence, Psychotherapy

1. Introduction

Buprenorphine is a partial mu-opioid receptor agonist and kappa-opioid antagonist recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of opioid dependence (FDA Talk Paper & T02-38, 2002). This approval, along with provisions of the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (Public Law 106-310, 106th Congress, 2000), allow for the use of buprenorphine in office-based treatment settings. This contrasts with other FDA-approved opioid agonist medications, such as methadone, which can only be prescribed at specialized, DEA-approved substance abuse treatment programs. Cocaine is frequently used by patients receiving opioid-agonist treatment for opioid dependence; such use is associated with poor treatment outcome (Leri, Bruneau, & Stewart, 2003). Buprenorphine has previously been investigated for the treatment of concomitant opioid and cocaine dependence. Some clinical trials conducted in dually-dependent (opioid and cocaine) patients show that buprenorphine reduces cocaine use (Gastfriend, 1993; Kosten, Kleber, & Morgan, 1989a, 1989b; Oliveto, Feingold, Schottenfeld, Jatlow, & Kosten, 2001; Schottenfeld, Pakes, Ziedonis, & Kosten, 1993). Other studies, especially those using lower buprenorphine doses, find no such effect (Oliveto, Kosten, Schottenfeld, & Ziedonis, 1993; Schottenfeld, Pakes, Oliveto, Ziedonis, & Kosten, 1997; Strain, Stitzer, Liebson, & Bigelow, 1994). A recent study by our group showed significant efficacy of buprenorphine sublingual solution in the treatment of dual (cocaine and opiate) dependence with doses of at least 8 mg daily (Montoya et al., 2004). Subjects in that study also received individual, standardized interpersonal cognitive psychotherapy. We address here the question: Does psychotherapy attendance influence buprenorphine treatment outcome?

The combination of non-pharmacological interventions with pharmacotherapy is a common clinical practice in drug abuse treatment in order to obtain a synergistic effect from the two treatment modalities (Covi, Hess, Schroeder, & Preston, 2002; Montoya et al., 2000). In particular, non-pharmacological interventions can improve cocaine-dependence treatment outcome during opioid agonist treatment (McLellan, Arndt, Metzger, Woody, & O'Brien, 1993). Among the behavioral therapies, contingency management has been the most thoroughly investigated for the treatment of cocaine dependence in methadone-maintained individuals. Contingency management, based on the principles of operant conditioning, uses voucher-based incentives (Higgins, Budney, & Bickel, 1994). This approach has been particularly effective in improving retention and increasing cocaine abstinence (Higgins, Alessi, & Dantona, 2002; Robles et al., 2000; Silverman et al., 1996). Contingency management also appears to improve the treatment outcome of opioid agonist therapy (Bickel, Amass, Higgins, Badger, & Esch, 1997; Preston, Umbricht, & Epstein, 2000). It also showed promising results in reducing cocaine use in a sample of dually (cocaine and heroin) dependent patients treated with buprenorphine (Downey, Helmus, & Schuster, 2000). However, contingency management can be expensive, and does not seem to be widely used by drug abuse treatment programs (Petry & Simcic, 2002).

Less research has been reported on other psychotherapies for treatment of opioid and cocaine dependence. The most commonly used are cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal psychotherapies. Cognitive-behavioral therapy is based on social learning principles and has shown efficacy when used in manualized protocols (Carroll et al., 1994). Interpersonal psychotherapy is a brief, individual psychological treatment whose goals are reduction or cessation of cocaine use and development of more productive strategies for dealing with social and interpersonal problems associated with the onset and perpetuation of cocaine use (Rounsaville, Gawin, & Kleber, 1985; Rounsaville & Kleber, 1985). Although the effect of contingency management has been reported to be significantly greater during acute treatment, cognitive-behavioral therapy seems to produce comparable long-term outcomes (Epstein, Hawkins, Covi, Umbricht, & Preston, 2003; Rawson et al., 2002).

Studies looking at the effect of psychotherapy attendance on treatment outcome have shown varying results. A study comparing three doses of cognitive behavioral psychotherapy for cocaine dependence showed no differences among groups; however, even the less intensive schedule was effective (Covi et al., 2002). On the other hand, more frequent attendance at group therapy or at self-help (12-step) group meetings has been associated with greater abstinence in patients with alcohol and other drug use (Fiorentine & Hillhouse, 2003). A recent study of dually dependent (cocaine and heroin) outpatients treated with buprenorphine plus desipramine and contingency management showed that participants did better with more intensive psychosocial interventions during treatment (Kosten, Poling, & Oliveto, 2003).

In the present study, we examined the relationship between attendance at standardized, manual-based psychotherapy sessions during buprenorphine maintenance treatment and drug use by dually (cocaine, heroin) dependent outpatients (Montoya et al., 2004). We hypothesized that greater attendance at psychotherapy sessions would be associated with lower heroin and cocaine use.

2. Methods

We conducted a secondary analysis of data from a randomized, double-blind clinical trial testing the efficacy of sublingual buprenorphine (2 mg, 8 mg, or 16 mg daily, or 16 mg every other day) for the treatment of comorbid cocaine and opioid dependence (Montoya et al., 2004). The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Bayview Institutional Review Board, and was conducted in a sample of 200 opioid- and cocaine-dependent subjects (DSM-IIIR criteria) in the outpatient clinic of the National Institute on Drug Abuse Intramural Research Program (NIDA IRP; Baltimore, MD).

Subject inclusion criteria were age 21-50 years, comorbid current cocaine and opioid dependence (by DSM-IIIR criteria), self-reported use of cocaine and opioids within the past 14 days, use of at least $50 per day of heroin and $100 per week of cocaine at some time over the past month, two urine samples positive for opioids and for cocaine during the screening process, and not currently in drug abuse treatment elsewhere. Excluded were individuals unable to understand or fill out questionnaires, with a current unstable medical or psychiatric disorder, and pregnant or nursing women. HIV-infected individuals with CD4 T cell count < 200/mL were also excluded due to the risk that their impaired immune status might interfere with study participation.

Of the 200 subjects enrolled in the trial, 179 were considered evaluable, having completed the 4-day buprenorphine induction period and having achieved their target buprenorphine dose. For this report, we analyzed data from the 90 patients who completed the scheduled 70-day maintenance buprenorphine treatment period. This avoided any confounding of treatment outcome by differences in study retention.

2.1. Procedures

Applicants received a thorough medical and behavioral/psychological evaluation. After qualification and consent, subjects had their first clinic visit within one week. Subjects were scheduled to participate in a 91-day treatment program that required daily clinic visits. At each visit they ingested a medication dose, had physiologic measures taken, and provided self-report data on outcome measures. At three visits each week (usually Monday, Wednesday, Friday), they gave a urine sample (for drug assay) under staff observation. Subjects were discharged for missing three consecutive medication doses or six psychotherapy sessions. Cancelled or rescheduled sessions did not count as missed sessions. Urine samples were assayed semi-quantitatively using the Abuscreen OnLine DAT immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, IN) for morphine and benzoylecgonine (BZE), both with a lower limit of quantification of 100 ng/mL.

2.2. Pharmacotherapy

Sublingual buprenorphine doses escalated to the targeted dose by day 5 (dose escalation phase) then remained at the target until day 70 (maintenance phase). Over the last 20 days, doses were decreased to 0 (withdrawal phase). Matching buprenorphine placebo was given on days of 0-mg buprenorphine dosing.

2.3. Psychotherapy

Subjects received weekly individual standardized drug abuse psychotherapy, based on cognitive-behavioral therapy (Carroll et al., 1994) and some elements of interpersonal therapy (Rounsaville, Gawin, & Kleber, 1985). The therapy was based on a manual developed by investigators at the NIDA IRP (Covi et al., 2002).

The therapy manual had two parts. Part I provided an overview of the course of treatment and discussed general issues of conducting treatment at each session. Part II provided a more detailed description of the 21 therapeutic techniques that could be used during the treatment based on the specific needs of the patient. The therapy manual offered a wide range of techniques and options for use by counselors. These included the identification of drug craving cues, recognition of interpersonal relationships, reframing and improvement of the decision-making process, overcoming helplessness, managing symptoms of depression and anxiety, increasing ability to relax without drugs, and increasing structure in the patient's life.

The therapy itself had four phases: (1) review of personal history, formulation of problems and goals, and development of a therapeutic alliance; (2) development of strategies to achieve treatment goals and control drug use; (3) strengthening of strategies and skills that prevent drug use, learning to use available support resources; and (4) resolution of separation and termination issues (Covi & Lipman, 1987; Covi, Hess, Kreiter, & Haertzen, 1995).

The urine toxicology test results were available to counselors and were part of the evaluation of patients' treatment progress. In addition, these results were discussed with members of the treatment team in the weekly clinical case conferences in order to formulate treatment goals for the following week. There were no negative contingencies for having drug-positive urine tests and no positive contingencies (payment or vouchers to exchange for goods or services) for attending psychotherapy sessions or having drug-free urine tests.

2.4. Psychotherapists

Individuals with a master's degree in a psychotherapy-related discipline provided the psychotherapy. One of the authors (LC) developed the therapy manual (Covi et al., 2002), trained the therapists and provided therapy supervision throughout the study. Fidelity to the therapy manual and study protocol, as well as patients' treatment progress, were reviewed at weekly clinical case conferences attended by all therapists, the therapist supervisor, the study nurse, and at least one of the investigators.

2.5. Data analysis

Because psychotherapy attendance was mandatory only during weeks 2-10 of the study (the buprenorphine maintenance phase) and because we were interested in drug use outcomes while subjects were being actively maintained on buprenorphine, rather than when medication was being withdrawn, the psychotherapy attendance and urine toxicology data used for this report were limited to this 9-week period. Psychotherapy attendance data were analyzed as percent visits kept; i.e., the number of psychotherapy visits attended, whether as scheduled or rescheduled, divided by the total number of scheduled or rescheduled visits.

Thrice-weekly quantitative urine benzoylecgonine and morphine levels were used as outcome measures. Quantitative urinalysis (drug metabolite concentration) was used rather than qualitative urinalysis (metabolite present/absent) because drug metabolite levels have been shown to have good discriminative validity, correlate well with self-reported drug use (Delucchi, Jones, & Batki, 1997), and confer additional statistical power for detecting a treatment effect (Batki, Manfredi, Jacob, & Jones, 1993). Urine test results were log-transformed to normalize their right-skewed distributions. Histograms of the log-transformed concentrations looked approximately Gaussian and did not reveal any potential outliers.

Sociodemographic and psychiatric correlates of psychotherapy attendance were identified using t-tests and Spearman correlation coefficients. To identify those variables that could potentially confound the relationship between psychotherapy attendance and urine metabolite levels, any subject characteristic showing a statistically significant (p < 0.05) association with overall percent psychotherapy visits kept (weeks 2-10) was then tested for a significant association with urine metabolite levels by including each separately as an independent variable in repeated-measures linear regression models having log(BZE) and log(morphine) for weeks 2 through 10 as outcome measures.

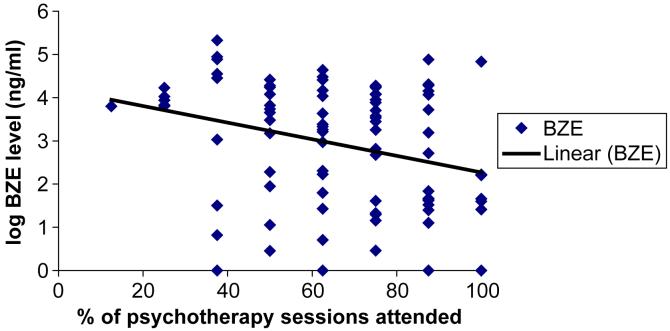

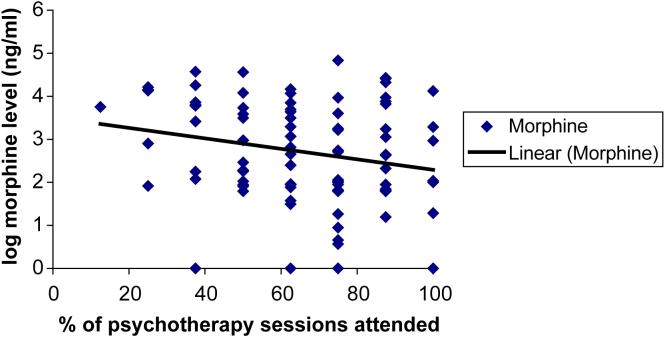

The relationship between psychotherapy attendance and urine metabolite levels was first evaluated using scatterplots of the cumulative percent of visits attended through week 9 versus urine metabolite levels during week 10 (Figs. 1 and 2). Relationships observed in the graphs were further evaluated using repeated-measures linear regression. The outcome measures were the log-transformed concentrations of urine BZE and morphine collected thrice weekly during weeks 3 to 10, with psychotherapy attendance as the time-varying covariate (percent visits attended through the previous week). For example, percent visits attended through week 2 was the covariate for urine drug metabolite levels during week 3, percent visits attended through week 3 was the covariate for urine drug metabolite levels during week 4, and so on through week 9 for psychotherapy and week 10 for urine drug metabolite levels. For each outcome measure, an initial regression model was fit that included psychotherapy attendance, treatment group, study week, the interaction terms (psychotherapy attendance × treatment group, psychotherapy attendance × study week, study week × treatment group, and psychotherapy attendance × study week × treatment group), and any potential confounding variables. Statistical significance of model terms was evaluated using F tests; whether regression coefficients differed from zero was determined using t tests. If the three-way interaction term was not significant (p > 0.05), it was dropped and the model re-fit. If two-way interaction terms in the re-fit model were not significant, they were dropped and the model again re-fit. The final model retained only significant interaction terms and all main effects. All analyses were conducted using SAS v. 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Fig. 1.

Scatterplot of relationship between psychotherapy attendance and urine benzoylecgonine (BZE) levels for 90 cocaine- and opioid-dependent outpatients treated with buprenorphine.

Fig. 2.

Scatterplot of relationship between psychotherapy attendance and urine morphine levels for 90 cocaine- and opioid-dependent outpatients treated with buprenorphine.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

The 90 subjects who completed the 70-day buprenorphine maintenance period were 72.2% male, 75.6% African-American, with mean age 33.7 ± 6.32 (SD) years. Thirty percent of patients had no high school diploma or equivalent, and 37.8% were unemployed. Only 5.6% of the subjects were HIV-positive; 21.1% declined HIV testing upon admission so their HIV status was unknown. All subjects met DSM-IIIR criteria for concurrent opioid and cocaine dependence; self-reported use at baseline was 29.3 ± 29.6 (SD) mg/day of opioids and 1.34 ± 1.54 (SD) g/day of cocaine. Common lifetime psychiatric diagnoses (DSM-IIIR) were: alcohol dependence 27.8%, phobia 21.1%, antisocial personality disorder 12.2%, post-traumatic stress disorder 11.1%, depression 4.4%, dysthymia 2.2%. The only significant difference among medication groups was in educational attainment (Table 1); there were significant associations of buprenorphine dose with both years of education, F(3,86) = 3.49, p = 0.02, and proportion lacking a high school diploma, χ2 = 10.3, df = 3, p = 0.02.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, baseline drug use, and psychiatric characteristics of 90 cocaine- and opioid-dependent outpatients completing 10 weeks of buprenorphine maintenance treatment

| 16 mg qd (n = 22) | 16 mg qod (n = 26) | 8 mg qd (n = 20) | 2 mg qd (n = 22) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Male | 77.3% | 69.2% | 65.0% | 77.3% | 0.75 |

| % African-Americans | 72.7% | 69.2% | 75.0% | 86.4% | 0.56 |

| Age† | 34.0 (7.5) | 33.7 (5.4) | 32.8 (5.8) | 34.2 (6.9) | 0.91 |

| % Single | 50.0% | 57.7% | 55.0% | 66.7% | 0.73 |

| % Unemployed | 36.4% | 38.5% | 50.0% | 27.3% | 0.51 |

| % No HS Diploma | 31.8% | 46.2% | 35.0% | 4.6% | 0.016 |

| Years ed.† | 11.6 (1.6) | 11.1 (1.4) | 11.5 (1.8) | 12.5 (0.99) | 0.019 |

| % HIV+ * | 5.6% | 5.0% | 14.3% | 0% | 0.39 |

| Baseline daily use†: | |||||

| Cocaine, g | 1.1 (0.8) | 1.2 (1.2) | 1.0 (1.3) | 2.2 (2.4) | 0.06 |

| Opioids, mg | 28.2 (20.5) | 30.0 (35.6) | 20.8 (21.5) | 37.7 (36.0) | 0.37 |

| Lifetime Psych Dx: | |||||

| Alcohol dependence | 22.7% | 19.2% | 40.0% | 31.8% | 0.41 |

| Antisocial Pers Dis | 9.1% | 19.2% | 15.0% | 4.6% | 0.46 |

| Depression | 9.1% | 3.9% | 0% | 4.6% | 0.73 |

| Dysthymia | 4.6% | 3.9% | 0% | 0% | 0.99 |

| Phobia | 9.1% | 30.8% | 35.0% | 9.1% | 0.08 |

| PTSD | 13.6% | 15.4% | 5.0% | 9.1% | 0.79 |

| % Therapy appts kept† | 72.9 (21.5) | 70.7 (23.7) | 69.7 (21.1) | 70.4 (17.9) | 0.96 |

Mean (SD)

Overall, 21.1% of the individuals declined to be tested and thus their HIV status was unknown.

Subjects who completed 10 weeks of buprenorphine maintenance (n = 90) were significantly less likely to have a diagnosis of alcohol dependence (27.8% vs. 42.7%, p = 0.027 by Fisher's exact test) or antisocial personality disorder (12.2% vs. 26.4%, χ2 = 6.19, df = 1, p = 0.01) than those who did not complete the 10-week buprenorphine maintenance period (n = 110). There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups on any other characteristic listed in Table 1 (data not shown).

3.2. Psychotherapy attendance

Of the 738 scheduled psychotherapy visits during study weeks 2-10 (mean of 8.2 scheduled visits per subject), 158 (21.4%) were missed without prior notification (“no shows”), 41 (5.6%) were cancelled by the subject, 16 (2.2%) were rescheduled but not attended, 39 (5.3%) were rescheduled and attended, and 484 (65.6%) were attended as scheduled. The mean percent of visits kept per subject was 71.0% (median 75.0%, range 22.2-100%); 17.8% of subjects kept all their scheduled psychotherapy visits and 15.6% kept less than half their visits. The four medication groups did not differ significantly in psychotherapy attendance (Table 1).

Ethnicity was associated with psychotherapy attendance. African-Americans kept a lower proportion of psychotherapy visits than did Caucasians: 68.1% vs. 79.7% (t = -2.31, df = 88, p = 0.02). Gender, age, marital status, employment, HIV status, educational attainment, baseline opioid and cocaine use, and lifetime psychiatric diagnoses were not significantly associated with psychotherapy attendance (data not shown).

Ethnicity was associated with both outcome measures. African-American ethnicity was associated with higher urine BZE levels, beta = 0.58 ± 0.18, F(1,88) = 9.99, p = 0.002, and higher urine morphine levels, beta = 0.79 ± 0.14, F(1,88) = 30.61, p < 0.0001. Thus, ethnicity was identified as a possible confounding factor and included as a covariate in multiple regression analyses used to determine the effect of psychotherapy attendance on urine drug metabolite levels.

3.3. Psychotherapy attendance and subsequent drug use

A scatterplot of the relationship between psychotherapy attendance (percent of visits kept) and cocaine use (urine BZE levels) suggested a significant relationship between psychotherapy attendance through study week 9 and urine BZE levels during week 10, the end of buprenorphine maintenance (Fig. 1). Regression analysis showed no significant main effect of psychotherapy attendance on urine BZE (p = 0.19), but there was a significant psychotherapy attendance by study week interaction (p = 0.04), indicating that the influence of psychotherapy attendance grew more pronounced as the study progressed (Fig. 1, Table 2). There was no significant psychotherapy attendance by medication group interaction, indicating that the effect of psychotherapy attendance was similar across all four buprenorphine doses.

Table 2.

Repeated measures linear regression modeling of the effects of psychotherapy attendance (% visits kept), buprenorphine medication group, and study week on urine drug metabolite levels in 90 cocaine- and opiate-dependent outpatients

| Log(BZE) | Log(Morphine) | |

|---|---|---|

| Percent visits kept |

F(1,1698) = 1.75, p = 0.19 |

F(1,1697) = 4.29, p = 0.039 -0.12 ± 0.33 |

| Medication group* |

F(3,85) = 3.96, p = 0.011 |

F(3,85) = 3.07, p = 0.032 |

| 8qd | -0.14 ± 0.22 | -0.16 ± 0.36 |

| 16qod | 0.051 ± 0.21 | 0.63 ± 0.34 |

| 16qd | -0.62 ± 0.22† | -0.35 ± 0.37 |

| Study week |

F(1,1698) = 3.78, p = 0.052 |

F(1,1697) = 0.24, p = 0.63 |

| Ethnicity |

F(1,85) = 7.42, p = 0.0078 |

F(1,85) = 25.95, p < 0.0001 |

| African-American | 0.49 ± 0.18† | 0.72 ± 0.14† |

| % Visits kept × week |

F(1,1698) = 4.06, p = 0.044 |

[not in model] |

| % Visits kept × medication group |

[not in model] |

F(3,1697) = 3.16, p = 0.024 |

Tests of significance for all terms are shown; individual parameter estimates with standard errors are shown only for significant main effects.

2 mg qd is reference group; parameter estimates for other medication groups reflect the difference between that group and the reference group.

parameter significantly different from zero (p < 0.05) by t-test

As was true for cocaine use, the scatterplot between urine morphine levels during week 10 and percent psychotherapy visits kept through week 9 suggested an inverse relationship between psychotherapy attendance and opioid use (Fig. 2). However, repeated measures regression analysis showed a significant interaction between psychotherapy attendance and medication group along with a significant main effect of psychotherapy attendance, indicating that the effect of psychotherapy attendance varied by medication group. Urine morphine level at week 10 versus psychotherapy attendance during weeks 2 to 9 analyzed separately for each buprenorphine dose group suggested that the inverse relationship between psychotherapy attendance and opioid use is strongest for subjects randomized to receive 16 mg every other day. There was no significant main effect of study week or psychotherapy attendance by study week interaction, indicating that the effect of psychotherapy attendance occurred throughout the study.

4. Discussion

Psychotherapy has traditionally been an integral part of the treatment of psychiatric disorders, particularly substance use disorders (Colom, Vieta, Martinez, Jorquera, & Gasto, 1998; Montoya et al., 2000). Even when pharmacotherapy is the primary component of treatment, as with opioid agonist treatment for opioid dependence, some form of psychotherapy is usually included (Etheridge, Craddock, Dunteman, & Hubbard, 1995). Consequently, clinicians and clinical investigators make efforts to motivate patients to attend psychotherapy while receiving pharmacotherapy (Barber, Foltz, Crits-Christoph, & Chittams, 2004; Montoya, Hess, Preston, & Gorelick, 1995; Siqueland et al., 2002). Studies of other psychiatric disorders, such as affective disorders, anxiety disorders, and schizophrenia, have shown the positive influence of psychotherapy on pharmacotherapy outcome (Barrowclough et al., 1999; Colom, Vieta, Reinares, et al., 2003; Colom, Vieta, Martinez-Aran, et al., 2003; Colom, Vieta, Martinez, Jorquera, & Gasto, 1998; Paykel et al., 1999; Tarrier et al., 1999). For substance use disorders, several studies have shown that therapist and patient adherence and providing more psychotherapy improve treatment outcome (Barber et al., 2001; Crits-Christoph et al., 2001; Fiorentine, 2001; Fiorentine & Hillhouse, 2003), but these studies did not involve pharmacological treatment. Furthermore, these studies did not differentiate the influence of attendance on specific substance use disorders. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the positive relationship between attendance at prescribed psychotherapy sessions and the outcome of buprenorphine treatment.

Non-adherence by patients to the prescribed treatment is a difficult issue in health care, especially in the treatment of substance use disorders (Barber et al., 2004; Barber, Crits-Christoph, & Luborsky, 1996). Psychotherapy attendance may depend on the psychological characteristics of the patient (e.g., capacity for insight), empathy between the therapist and the patient, the patient's perceived need for treatment, efficacy of the intervention, and external factors (e.g., court mandated therapy, employment supervision, or losing of some rights; Colom, 2002; Lingam & Scott, 2002). In this study, psychotherapy attendance seemed to have been influenced mainly by internal factors; external factors played only a small role. All patients were volunteers, the medication was administered double blind, no contingent vouchers were offered, and only those subjects who completed the treatment were included in the analysis. In addition, there was little or no interaction between psychotherapy attendance and buprenorphine dose on treatment outcome, suggesting that the effect of medication dose on psychotherapy attendance was minimum. However, we cannot rule out that the contingency of being discharged from the study for missing more than six psychotherapy sessions or the perceived benefit of the opioid agonist therapy may have been external factors that motivated subjects to comply with the psychotherapy. Of the subject characteristics that we evaluated, only ethnicity was significantly associated with psychotherapy attendance. Clearly, more research is needed on the characteristics of non-adherent psychiatric patients (Lingam & Scott, 2002).

A strength of this study is its robustness. By limiting the analysis to study completers, the effect of the psychotherapy was not confounded by the likelihood that the subjects most committed to treatment were the ones who show more treatment improvement. In addition, the effect of psychotherapy attendance was apparent against a background of high levels of psychotherapy attendance and treatment participation and administration of an effective treatment medication (buprenorphine).

Limitations of this study include the lack of data on the quality or duration of each psychotherapy visit, the characteristics of the therapist, and therapist adherence to the treatment manual. The generalizability of the findings may also be limited by including in the analysis only subjects who completed the treatment. However, given the lack of systematic evaluation of the influence of psychotherapy attendance on pharmacotherapy trials in substance abuse, and the design strengths of this study (standardized, manual-based psychotherapy in the context of a controlled clinical trial of a medication with significant therapeutic effect), we believe that the results are useful and valid.

The results of this study suggest that psychotherapy should be an integral part of the buprenorphine treatment plan for patients with dual cocaine and opioid dependence. Now that buprenorphine is available for use in office-based environments, it may be advisable for clinicians to include a psychotherapy component of treatment, either directly themselves or through referral elsewhere. There is a need for systematic research on the effect of psychotherapy on other pharmacological treatments for substance use disorders, the factors that may affect psychotherapy attendance, compliance and/or adherence, and the efficacy of behavioral and/or psychotherapeutic interventions to improve treatment adherence.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIDA intramural funds. A preliminary version was presented at the College on Problems of Drug Dependence, 65th annual scientific meeting, Bal Harbour, FL, June, 2003.

We thank Ms. Judy Hess for helping with training of therapists and monitoring the fidelity of the therapy manual and Ms. Lina Montoya for helping with the design of the figures.

References

- Barber JP, Crits-Christoph P, Luborsky L. Effects of therapist adherence and competence on patient outcome in brief dynamic therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:619–622. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.3.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber JP, Foltz C, Crits-Christoph P, Chittams J. Therapists' adherence and competence and treatment discrimination in the NIDA Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;60:29–41. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber JP, Luborsky L, Gallop R, Crits-Christoph P, Frank A, Weiss RD, Thase ME, Conolly MB, Gladis M, Foltz C, Siqueland L. Therapeutic alliance as a predictor of outcome and retention in the National Institute on Drug Abuse Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:119–124. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrowclough C, Tarrier N, Lewis S, Sellwood W, Mainwaring J, Quinn J, Hamlin C. Randomised controlled effectiveness trial of a needs-based psychosocial intervention service for carers of people with schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;174:505–511. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.6.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batki SL, Manfredi LB, Jacob P, III, Jones RT. Fluoxetine for cocaine dependence in methadone maintenance: quantitative plasma and urine cocaine/benzoylecgonine concentrations. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1993;13:243–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Amass L, Higgins ST, Badger GJ, Esch RA. Effects of adding behavioral treatment to opioid detoxification with buprenorphine. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:803–810. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Nich C, Gordon LT, Wirtz PW, Gawin F. One-year follow-up of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for cocaine dependence. Delayed emergence of psychotherapy effects. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:989–997. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950120061010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colom F. The mechanism of action of psychotherapy. Bipolar Disorders. 2002;4(Suppl 1):102. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.4.s1.46.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez A, Jorquera A, Gasto C. What is the role of psychotherapy in the treatment of bipolar disorder? Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 1998;67:3–9. doi: 10.1159/000012252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, Reinares M, Goikolea JM, Benabarre A, Torrent C, Comes M, Corbella B, Parramon G, Corominas J. A randomized trial on the efficacy of group psychoeducation in the prophylaxis of recurrences in bipolar patients whose disease is in remission. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:402–407. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.4.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colom F, Vieta E, Reinares M, Martinez-Aran A, Torrent C, Goikolea JM, Gasto C. Psychoeducation efficacy in bipolar disorders: Beyond compliance enhancement. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2003;64:1101–1105. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covi L, Hess JM, Kreiter NA, Haertzen CA. Effects of combined fluoxetine and counseling in the outpatient treatment of cocaine abusers. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1995;21:327–344. doi: 10.3109/00952999509002701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covi L, Hess JM, Schroeder JR, Preston KL. A dose response study of cognitive behavioral therapy in cocaine abusers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;23:191–197. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covi L, Lipman RS. Cognitive behavioral group psychotherapy combined with imipramine in major depression. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1987;23:173–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crits-Christoph P, Siqueland L, McCalmont E, Weiss RD, Gastfriend DR, Frank A, Moras K, Barber JP, Blaine J, Thase ME. Impact of psychosocial treatments on associated problems of cocaine-dependent patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:825–830. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.5.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delucchi KL, Jones RT, Batki SL. Measurement properties of quantitative urine benzoylecgonine in clinical trials research. Addiction. 1997;92:297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey KK, Helmus TC, Schuster CR. Treatment of heroin-dependent poly-drug abusers with contingency management and buprenorphine maintenance. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;8:176–184. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DH, Hawkins WE, Covi L, Umbricht A, Preston KL. Cognitive-behavioral therapy plus contingency management for cocaine use: findings during treatment and across 12-month follow-up. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:73–82. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etheridge RM, Craddock SG, Dunteman GH, Hubbard RL. Treatment services in two national studies of community-based drug abuse treatment programs. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1995;7:9–26. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90303-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA Talk Paper & T02-38 Subutex and Suboxone approved to treat opiate dependence. 2002 Available: http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/ANSWERS/2002/ANS01165.html. (Retrieved 10-8-2002)

- Fiorentine R. Counseling frequency and the effectiveness of outpatient drug treatment: revisiting the conclusion that “more is better”. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2001;27:617–631. doi: 10.1081/ada-100107659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentine R, Hillhouse MP. Why extensive participation in treatment and twelve-step programs is associated with the cessation of addictive behaviors: an application of the addicted-self model of recovery. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2003;22:35–55. doi: 10.1300/J069v22n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gastfriend D. Buprenorphine treatment of cocaine abuse. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 1993;12:155–170. doi: 10.1300/J069v12n03_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Alessi SM, Dantona RL. Voucher-based incentives. A substance abuse treatment innovation. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27:887–910. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK. Applying behavioral concepts and principles to the treatment of cocaine dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1994;34:87–97. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten T, Poling J, Oliveto A. Effects of reducing contingency management values on heroin and cocaine use for buprenorphineand desipramine-treated patients. Addiction. 2003;98:665–671. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TR, Kleber HD, Morgan C. Role of opioid antagonists in treating intravenous cocaine abuse. Life Sciences. 1989a;44:887–892. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(89)90589-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TR, Kleber HD, Morgan C. Treatment of cocaine abuse with buprenorphine. Biological Psychiatry. 1989b;26:637–639. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(89)90090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leri F, Bruneau J, Stewart J. Understanding polydrug use: review of heroin and cocaine co-use. Addiction. 2003;98:7–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingam R, Scott J. Treatment non-adherence in affective disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002;105:164–172. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.1r084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Arndt IO, Metzger DS, Woody GE, O'Brien CP. The effects of psychosocial services in substance abuse treatment. JAMA. 1993;269:1953–1959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya ID, Gorelick DA, Preston KL, Schroeder JR, Umbricht A, Cheskin LJ, Lange WR, Contoreggi C, Johnson RE, Fudala PJ. Randomized trial of buprenorphine for treatment of concurrent opiate and cocaine dependence. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2004;75:34–48. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya ID, Hess JM, Preston KL, Gorelick DA. A model for pharmacological research-treatment of cocaine dependence. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1995;12:415–421. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(95)02017-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya ID, Svikis D, Marcus SC, Suarez A, Tanielian T, Pincus HA. Psychiatric care of patients with depression and comorbid substance use disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2000;61:698–705. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n0917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveto A, Kosten T, Schottenfeld R, Ziedonis D. Cocaine abuse among methadone-maintained patients [letter] American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:1755. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.11.1755a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveto AH, Feingold A, Schottenfeld R, Jatlow P, Kosten TR. Desipramine in opioid-dependent cocaine abusers maintained on buprenorphine vs methadone. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;56:812–820. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.9.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paykel ES, Scott J, Teasdale JD, Johnson AL, Garland A, Moore R, Jenaway A, Cornwall PL, Hayhurst H, Abbott R, Pope M. Prevention of relapse in residual depression by cognitive therapy: a controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:829–835. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.9.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Simcic F., Jr. Recent advances in the dissemination of contingency management techniques: clinical and research perspectives. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;23:81–86. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston KL, Umbricht A, Epstein DH. Methadone dose increase and abstinence reinforcement for treatment of continued heroin use during methadone maintenance. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:395–404. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Law 106-310 2000. 1. C. Drug Addiction Treatment Act.

- Rawson RA, Huber A, McCann M, Shoptaw S, Farabee D, Reiber C, Ling W. A comparison of contingency management and cognitive-behavioral approaches during methadone maintenance treatment for cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:817–824. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles E, Silverman K, Preston KL, Cone EJ, Katz E, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. The brief abstinence test: voucher-based reinforcement of cocaine abstinence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;58:205–212. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Gawin F, Kleber H. Interpersonal psychotherapy adapted for ambulatory cocaine abusers. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1985;11:171–191. doi: 10.3109/00952998509016860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Kleber HD. Psychotherapy/counseling for opiate addicts: strategies for use in different treatment settings. International Journal of the Addictions. 1985;20:869–896. doi: 10.3109/10826088509047757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schottenfeld RS, Pakes J, Ziedonis D, Kosten TR. Buprenorphine: dose-related effects on cocaine and opioid use in cocaine-abusing opioid-dependent humans. Biological Psychiatry. 1993;34:66–74. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90258-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schottenfeld RS, Pakes JR, Oliveto A, Ziedonis D, Kosten TR. Buprenorphine vs methadone maintenance treatment for concurrent opioid dependence and cocaine abuse. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:713–720. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830200041006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Higgins ST, Brooner RK, Montoya ID, Cone EJ, Schuster CR, Preston KL. Sustained cocaine abstinence in methadone maintenance patients through voucher-based reinforcement therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:409–415. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830050045007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siqueland L, Crits-Christoph P, Gallop R, Barber JP, Griffin ML, Thase ME, Daley D, Frank A, Gastfriend DR, Blaine J, Connolly MB, Gladis M. Retention in psychosocial treatment of cocaine dependence: predictors and impact on outcome. American Journal of the Addictions. 2002;11:24–40. doi: 10.1080/10550490252801611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strain EC, Stitzer ML, Liebson IA, Bigelow GE. Buprenorphine versus methadone in the treatment of opioid-dependent cocaine users. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;116:401–406. doi: 10.1007/BF02247469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarrier N, Pilgrim H, Sommerfield C, Faragher B, Reynolds M, Graham E, Barrowlough C. A randomized trial of cognitive therapy and imaginal exposure in the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:13–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]