Abstract

The purpose of this open-label, uncontrolled study was to evaluate the feasibility of administering off-label buprenorphine in combination with ancillary medications for inpatient short-term detoxification of heroin-dependent patients at a psychiatric facility. A sample of 20 heroin-dependent patients admitted to an urban psychiatric hospital was administered buprenorphine 6, 4, and 2 mg/day during the first, second, and third day of detoxification, respectively, and then observed during the fourth and fifth day. Eighty-five percent of the subjects abused other substances, 75% reported cocaine abuse/dependence, 75% had comorbid mood disorders. All subjects completed the medication phase of the study. No clinically significant adverse events were reported. There was a significant decrease in the Clinical Investigation Narcotic Assessment (CINA) total score between baseline and days 2 through 5. The results suggest that buprenorphine is well tolerated and may be beneficial for medically supervised short-term withdrawal from heroin for hospitalized psychiatric patients.

Keywords: Buprenorphine, Detoxification, Heroin dependence, Psychiatric comorbidity, Psychiatric hospitalization

1. Introduction

Heroin addiction is a growing problem in the US, particularly among psychiatric patients. The number of heroin-related treatment admissions, emergency room visits, and overdose deaths has increased significantly over the past years. Incident estimates vary depending on the sampling procedure. However, 18% of patients treated by a nationally representative sample of psychiatrists in the US were diagnosed with at least one substance use disorder (Montoya et al., 2000). Another study conducted in a sample of 396 consecutively enrolled depressed patients found a 60% lifetime prevalence of substance dependence (Fava et al., 1996). An analysis of opioid-dependent patients seeking methadone maintenance treatment found that 47% had a psychiatric diagnosis other than substance abuse (Brooner, King, Kidorf, Schmidt, & Bigelow, 1997).

Comorbid substance use disorders represent an important challenge for the clinician. It can be difficult to differentiate between primary and secondary depression in opioid abusers. Effects from intoxication, withdrawal, and/or lifestyle choices such as sleep disturbance, appetite and weight changes, psychosis, and dysphoria can mimic the symptoms of mood or psychotic disorders. To make matters more complex, it can take weeks for these symptoms to resolve. In fact, a study of heroin abusers stabilized patients on at least 50 mg of methadone and waited 4-5 weeks to complete a final psychiatric evaluation (Brooner et al., 1997). The authors found that 85% of those who initially presented with depressive symptoms were eventually diagnosed with a substance-induced mood disorder. Identification of underlying psychiatric disorders in opioid abusers can be critical since these patients have a greater number of lifetime substance use diagnoses, more medical problems, more severe psychiatric symptoms and psychosocial problems, and poorer treatment compliance and outcomes (Brooner et al.,1997; Dixon, 1999; Dixon, McNary, & Lehman, 1998).

Thus, the clinician in an acute psychiatric inpatient setting is faced with a difficult task. Research has demonstrated that substance abuse and mental health treatment should be integrated in order to achieve optimal response (Dixon, 1999; RachBeisel, Scott, & Dixon, 1999). The psychiatrist must quickly and effectively diagnose and treat psychiatric disorders, as well as relieve withdrawal distress. Despite the fact that it is not life threatening, improper management of opiate withdrawal during inpatient psychiatric treatment makes diagnosing other psychiatric disorders impossible and produces great physical discomfort and psychological distress that may result in agitation, violence, premature discharge, heroin use relapse, and risk of overdose. Therefore, opiate withdrawal must be considered a medical priority when treating patients admitted to a residential ward.

Finding optimal treatment for heroin dependence is a matter of some urgency. Clonidine and methadone are the two medications most widely used for the treatment of heroin withdrawal on psychiatric inpatient units. While both are safe and effective, each has some disadvantages. Clonidine, an α-2 adrenergic antihypertensive, may cause sedation and hypotension, and may not completely block opiate withdrawal (Cheskin, Fudala, & Johnson, 1994; Nigam, Ray, & Tripathi, 1993; O'Connor et al., 1997; Gowing, Ali, & White, 2000a). Methadone, an opiate agonist, is a Schedule II Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) medication that can only be administered under stringent legal procedures and requires longer periods of time for dose tapering, which often are impractical in an acute setting and uncomfortable for patients (Strain, Bigelow, Liebson, & Stitzer, 1999). These disadvantages have important practical implications for the treatment of substance abusing psychiatric patients because they are often admitted for only short-term treatment and should complete any opiate withdrawal therapy while in the inpatient setting.

Buprenorphine is a partial μ-agonist and κ-antagonist. It has an agonist ceiling effect with high affinity and slow dissociation from mu opioid receptors. Clinically, this means that buprenorphine has a limited risk for toxicity and overdose, low abuse liability, longer duration of action, improved comfort during withdrawal, and efficacy at doses as low as 2 mg/d (Amass, Kamien, & Mikulich, 2000; Lange, Fudala, Dax, & Johnson, 1990; Walsh, Preston, Stitzer, Cone, & Bigelow, 1994). Buprenorphine has been shown to be efficacious in placebo-controlled trials for the detoxification of opiate withdrawal (Liu, Cai, Wang, Ge, & Li, 1997; Blennow, Fergusson, & Medvedeo, 2000; Umbricht et al., 1999). Studies suggest that it can be as efficacious as methadone and more efficacious than clonidine (O'Connor et al., 1997; Cheskin et al., 1994; Nigam et al., 1993; Gowing, Ali, & White, 2000b). The agent may be administered by the intravenous, sublingual, or buccal route (Kuhlman, Lalani, Magluilo, Levine, & Darwin, 1996). Buprenorphine has been shown to be safe and produces mostly innocuous side-effects such as headaches, sedation, nausea, constipation, anxiety, and dizziness (Walsh et al., 1994; Gowing et al., 2000b). It does not appear to produce significant hypotension, the side effect that often limits clonidine's utility (Cheskin et al., 1994; Nigam et al., 1993).

Psychiatric inpatient settings are in great need of safe and effective treatments for opiate-dependent patients that will control their withdrawal symptoms without requiring the individual be transferred to a long-term narcotic treatment clinic that is DEA-licensed to prescribe Schedule II medication. Given its pharmacological and clinical characteristics, buprenorphine may be a suitable alternative for treatment of opiate-dependent patients in residential psychiatric settings. Previously published studies have primarily assessed the efficacy of buprenorphine for detoxification in research facilities. To our knowledge, there are no trials that measure the utility of buprenorphine detoxification in a psychiatric hospital. The purpose of this study is to assess the feasibility to administer, and the benefits of buprenorphine in patients admitted to a psychiatric facility. The results should be useful for clinicians and clinical-investigators interested in providing safe and effective medications for these patients who are at a great psychosocial and medical disadvantage.

2. Materials and methods

This is an open-label, uncontrolled, dose-tapering study to evaluate the feasibility of buprenorphine for managing withdrawal symptoms in heroin-dependent psychiatric inpatients. The study was conducted from December of 1998 through July of 1999, on a psychiatric inpatient unit of the Walter P. Carter Center (WPCC), in Baltimore, Maryland. The WPCC is an urban facility that serves as a state psychiatric acute admission hospital for uninsured Baltimore residents. The study protocol and consent form were reviewed and approved by the WPCC, the University of Maryland School of Medicine, and the Maryland Institutional Review Boards before implementation.

2.1. Subjects

All WPCC admissions were evaluated by psychiatrists and accepted to the facility solely based on psychiatric symptoms. Once transferred to the unit, individuals were screened for history of heroin dependence with physiological dependence during a clinical admission assessment based on the DSM IV criteria. Patients were eligible to participate in the study if they used heroin daily for at least 2 weeks prior to admission, were currently experiencing heroin withdrawal symptoms, and were between 18 and 65 years of age. Exclusion criteria included physical dependence on alcohol or other sedative hypnotics, pregnancy or lactation, opioid use in the past 12 hours, enrollment in a methadone, buprenorphine, or LAAM maintenance program in the past 30 days, or evidence of a disease where a research buprenorphine protocol might be contraindicated (delirium, dementia, or active hepatic dysfunction). Patients who were oriented to time, person, and place, understood the protocol, and agreed to provide informed consent were allowed to participate in the study. Given the pilot design and absence of a comparison group, no statistical assumption and power calculations were conducted. The enrollment was planned for 20 subjects in order to assess feasibility without compromising the safety of a large number of patients.

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Clinical Institute Narcotic Assessment

The Clinical Institute Narcotic Assessment (CINA), a widely used measure of opiate withdrawal, evaluates subjective symptoms (myalgias, nausea, abdominal complaints, chills) and objective signs (piloerection, sweating, tremor, restlessness, lacrimation, yawning) of heroin withdrawal (Peachey & Lei, 1988). A trained nurse administered the rating scale at baseline to assess initial opioid withdrawal and then 3 times per day (before buprenorphine was administered, if applicable) during the 5-day protocol.

2.2.2. Opiate Withdrawal Treatment Satisfaction

During the discharge interview, subjects' satisfaction with their opiate withdrawal treatment was assessed by asking the following questions: 1) Would you recommend buprenorphine detoxification to a friend?; 2) Compared to previous withdrawal treatments, buprenorphine was: much better, the same, much worse; and 3) On a scale of 1-5 (1 = no withdrawal and 5 = no change in symptoms), how much would you say buprenorphine helped?

2.3. Intervention

Participants were administered injectable buprenorphine sublingually by a nurse according to the dose schedule presented in Table 1. Since the sublingual buprenorphine tablet was not commercially available, subjects were given the injectable formulation to hold under their tongues for 3-5 minutes under direct nursing observation.1 The medication dose and frequency, as well as duration of therapy, was chosen based on a previously published short-term detoxification protocol conducted in a substance abuse research unit (Cheskin et al., 1994). Subjects were offered standard hospital protocol medications for opioid withdrawal symptoms not relieved by buprenorphine, such as ibuprofen for muscle aches, kaopectate for diarrhea and abdominal cramps, and prochlorperazine for nausea and vomiting.

Table 1.

Daily buprenorphine dose schedule

| Day | Morning dose | Afternoon dose | Evening dose |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 mg SL | 2 mg SL | 2 mg SL |

| 2 | 2mg SL | 1 mg SL | 1 mg SL |

| 3 | 1mg SL | 1 mg SL | 0 mg SL |

| 4 | No drug | No drug | No drug |

| 5 | No drug | No drug | No drug |

SL = sublingual.

2.4. Data analyses

The primary outcome measures were retention in treatment, change in CINA scores over time, reported or observed adverse events, administration of ancillary medications, and results of the Opiate Withdrawal Treatment Satisfaction (OWTS) scale. Retention in treatment was analyzed as the percent of subjects admitted to the study, which remained at the end of each day and at the end of the 5-day protocol. Day 3 was defined as “end of medication” and Day 5 as “end of observation period.” CINA scores were analyzed by comparing the result of the mean score at baseline vs. the result of the mean score of each day of treatment using a paired t-test. Patients were asked about adverse effects during their stay in the inpatient unit and at the exit interview. At the end of the 5-day observation period or at discharge, whichever was sooner, data on concomitant medications was collected from the medication administration record in the patient chart. Adverse events and ancillary medications were reported as the percent of active subjects who presented with the symptoms or were administered the ancillary medications. The results of the OWTS scale were analyzed as the percent of respondents for each item. α level was set at 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Subjects characteristics

As shown in Table 2, the sample consisted of primarily younger to middle aged African American adults. All of the patients were transferred from emergency room settings after presenting with suicidical ideation and/or depressed mood (Table 3). Half had attempted suicide or had a specific plan to attempt suicide. Patients were assessed by a psychiatrist during their hospitalization. On discharge, the majority were diagnosed with substance-induced mood or psychotic disorders (Table 4). However, a few had more persistent symptoms suggestive of major depressive disorder or depressive disorder NOS. All patients were diagnosed as opiate dependent (Table 4), and most met the DSM-IV criteria for other substance use disorders (85%) (e.g., cocaine abuse/dependence [75%]).

Table 2.

Demographics characteristics (n = 20)

| Demographic characteristic | Demographic data |

|---|---|

| Mean age in years (range) | 34 (22-51) |

| Male | 13 (65%) |

| Female | 7 (35%) |

| African American | 19 (95%) |

| Caucasian | 1 (5%) |

Table 3.

Presenting psychiatric symptoms

| Psychiatric symptom | Number of patients (percentage) |

|---|---|

| Depressed mood and/or suicidal Ideation |

20 (100%) |

| Attempted suicide or had a specific plan | 10 (50%) |

| Vegetative symptoms | 9 (15%) |

| Auditory hallucinations | 4 (5%) |

Table 4.

Diagnosis

| Diagnosis | Number (percentage) |

|---|---|

| DSM-IV admission diagnosis | |

| R/O substance-induced mooda | 17 (85%) |

| R/O depressive disorder NOS | 10 (50%) |

| R/O major depressive disorder | 4 (20%) |

| “Depression due to general medical condition” | 1 (5%) |

| R/O adjustment disorder with depressed mood | 1 (5%) |

| R/O dysthymia | 1 (5%) |

| DSM-IV discharge diagnosis | |

| Substance-induced mood | 15 (75%) |

| Depressive disorder NOS | 3 (15%) |

| Major depressive disorder | 1 (5%) |

| Psychosis NOS | 1 (5%) |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 1 (5%) |

| Substance use disorders diagnosed on discharge | |

| Heroin dependence | 20 (100%) |

| Cocaine abuse dependence | 15 (75%) |

| Cannabis abuse/dependence | 3 (15%) |

| Amphetamine dependence | 1 (5%) |

| Abused multiple substances | 17 (85%) |

Only 6 (30%) of these patients had rule out substance-induced mood disorder as their primary diagnosis on admission.

3.2. Treatment retention and outcome

All study subjects completed the 3-day buprenorphine protocol and 17 (85%) remained in the hospital for at least 5 days. The three patients (15%) who did not stay for the additional 2 days of monitoring reported complete resolution of withdrawal symptoms and cited personal business as their reasons for leaving early.

3.3. Opiate withdrawal and adverse events

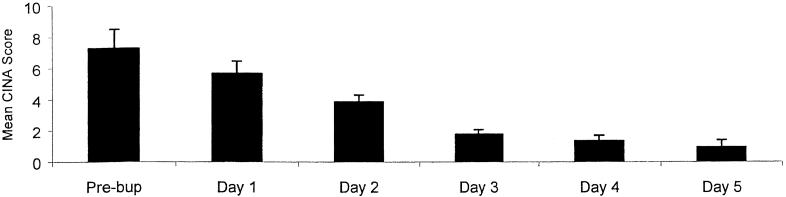

The mean (SE) CINA score (see Fig. 1) before buprenorphine administration was 7.2 (1.2). After buprenorphine administration, the mean CINA score for the first day of detoxification went down to 5.7 (0.8). Although this decrease was not statistically significant, it was clinically observed that all patients accepted the medication and opted to continue in treatment. Comparisons of CINA results before and after buprenorphine administration showed a significant (p < 0.01) decrease on days 2 and 3 of detoxification and even after buprenorphine had been discontinued on days 4 and 5 of treatment. The most common subjective symptoms of withdrawal were mild mylagias, nausea, and abdominal complaints. The most frequent objective signs of withdrawal were rhinohrrhea and restlessness. Concomitant as needed medications (Ibuprofen, prochlorperazine, or kaopectate) were requested by 10 of the subjects during the 5-day monitoring period (Table 5). Seven of the 10 or 35% of all subjects requested a concomitant medication for a withdrawal complaint. Ibuprofen for the treatment of myalgias was most commonly employed. Eight (40%) patients were maintained on psychotropic medication during their admission and four (20%) were discharged with psychotropic medication (Table 5). No patient reported side effects from the buprenorphine to the interviewer on discharge or to the nursing staff as documented in the chart. However, three patients received, as needed, medications for headaches while receiving buprenorphine.

Fig. 1.

Mean (SE) CINA scores for all patients completing the 3-day buprenorphine detoxification (n = 20).

Table 5.

Concomittant medication administration

| Pt | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | None | None | None | None |

| 2 | None | None | Diphen 50mg-insomnia | None | Ibu 800mg-headache |

| 3 | None | Diphen 50mg-insomnia APAP 650mg-headache |

None | None | None |

| 4 | None | None | None | None | None |

| 5 | Ibu 800mg-muscle ache Pro-nausea Diphen 50mg-insomnia |

Ibu 800mg-toothache Pro-vomiting |

Ibu 800mg-toothache Diphen 50mg-insomnia |

Ibu 1600mg-toothache Diphen 50mg-insomnia |

None |

| 6 | Traz 100mg qhs | Fluox 40mg | Fluox 40mg Traz 100mg |

Fluox 40mg | None |

| 7 | Ibu 1600mg-bodyaches | None | Ibu 800mg-backache | None | None |

| 8 | None | Parox 20 mg Ibu 1600mg-back pain |

Ibu 800mg-back pain Diphen 50mg-insomnia |

Parox 20mg Diphen 50mg-insomnia |

Parox 20mg |

| 9 | None | Traz 100 mg | Traz 100 mg | None | None |

| 10 | Diphen 50mg-insomnia | Diphen 50mg-insomnia Ibu 800mg-backache APAP 650mg-headache |

Diphen 50mg-insomnia | APAP 650mg-joint pain | Diphen 50mg-insomnia |

| 11 | Ibu 800mg-back pain Diphen 50mg-insomnia |

Fluox 60mg Ibu 800mg-toothache |

Fluox 60mg Ibu 800mg-toothache |

Fluox 60mg APAP 650mg-toothache Ibu 800mg-toothache Diphen 50mg-insomnia |

Fluox 60mg Ibu 800mg-joint pain Diphen 50mg-insomnia |

| 12 | Diphen 50mg-insomnia | None | Diphen 50mg-insomnia | Diphen 50mg-insomnia | Diphen 50mg-insomnia |

| 13 | None | None | None | None | None |

| 14 | None | None | Traz 50mg | Traz 50mg | Traz 50mg APAP 650mg-headache |

| 15 | Nortrip 25mg Diphen 50mg-insomnia |

Nortrip 25mg Diphen 50mg-insomnia |

Nortrip 25mg | Nortrip 25mg Diphen 50mg-insomnia |

Nortrip 25mg Diphen 50mg-insomnia |

| 16 | Ibu 800mg-muscle aches | None | None | None | None |

| 17 | None | None | None | None | None |

| 18 | Ibu 1600mg-arm and hip pain Diphen 50mg |

Ibu 1600mg-arm and hip pain Diphen 50mg |

Ibu 1600mg-arm and hip pain Diphen 50mg |

None | None |

| 19 | None | Ibu 800mg-back pain | Risp 2mg Traz 100mg |

Risp 2mg Traz 100mg |

Risp 2mg Parox 20mg Traz 100mg |

| 20 | Ibu 800 mg-muscle ache Pro nausea |

Ibu 800 mg-muscle ache Pro nausea |

Ibu 800 mg-muscleache APAP 650mg-headache |

Traz 200mg-insomnia Ibu 800mg-pain |

MOM constipation |

Diphen = Diphenhydramine; Ibu = Ibuprofen; APAP = Acetaminophen; Traz = Trazodone; Fluox = Fluoxetine; Parox = Paroxetine; Nortrip = Nortriptyline; Risp = Risperidone; Pro = Prochlorperazine; MOM = Milk of Magnesia.

3.4. Treatment satisfaction

Based on responses to the OWTS scale, 18 (90%) subjects stated that they would recommend buprenorphine to a friend for detoxification. The two who would not do so cited discomfort with the dosage administration (difficulty holding the buprenorphine under the tongue) as the reason for this response. Sixteen (80%) had received a pharmacologic detoxification previously, but not necessarily at this facility. Fifteen (94%) of these patients stated that buprenorphine was much better than previous detoxifications (primarily clonidine). One of the 16 patients stated that buprenorphine relieved his symptoms as well as methadone. None of the patients who had been previously detoxified reported that buprenorphine was less effective than alternative treatment strategies.

4. Discussion

Patients admitted to acute urban psychiatric facilities often have substance related disorders that can complicate their diagnosis and treatment. Those with heroin dependence require a safe and effective method for providing short-term detoxification. While methadone and clonidine have been available for this purpose for many years, they have important disadvantages. Given its pharmacological characteristics, buprenorphine may be a good alternative. Our open-label study suggests that the injectable buprenorphine formulation used sublingually may be beneficial for medically supervised opiate detoxification of heroin-dependent subjects during an inpatient psychiatric hospitalization. This conclusion is based on the high retention in treatment, decrease in withdrawal scores, lack of reported adverse events, and high degree of patient satisfaction.

Humanely managing opioid withdrawal on an inpatient psychiatric unit is necessary to provide optimal care and to retain patients in the hospital long enough to correctly diagnose and treat them. Previous buprenorphine detoxification studies have primarily been efficacy trials conducted in substance abuse research units. Controlled conditions allow for more reliable conclusions. However, the rigorous standards employed in these trials are often not possible in a real-world setting. This study is the first trial that assesses buprenorphine's utility in detoxifying patients hospitalized in a psychiatric facility.

The off label use of medications is common practice in medicine, particularly in psychiatry. Opioid withdrawal has been treated off label for many years with clonidine. Buprenorphine is FDA-approved for the management of pain. Although it is anticipated that it will be accepted by the FDA for the treatment of heroin withdrawal/dependence, it currently can only be administered for research purposes under an Investigational New Drug Application (IND). However, the Narcotic Addict Treatment Act of 1974 (Title 21 Section 1306.07 (b)) allows a licensed physician to use any FDA-approved narcotic medication for 3 days to relieve the acute withdrawal symptoms of heroin-addicted patients without an IND or registration as a narcotic treatment program. Such emergency treatment is frequently referred to as the 3-day rule. Furthermore, 1306.07 (c) states that this section is not intended to impose any limitations on a physician or authorized staff to administer or dispense narcotic drugs in a hospital to maintain or detoxify a person as an incidental adjunct to medical or surgical treatment of conditions other than addiction. Our subjects were admitted to the psychiatric hospital for treatment of psychiatric illness. As it turns out, many had mood disorders that were likely related to their addiction. However, they were not admitted for the treatment of their addiction, per se, making short term detoxification with buprenorphine possible under the 3-day rule.

The study was viewed as a success by patients and staff, leading the hospital administration to redesign the detoxification protocols with the intent of potentially eliminating clonidine and adding buprenorphine. All subjects in this study were able to complete the buprenorphine detoxification successfully without side effects requiring cessation of the protocol. None of the buprenorphine detoxified patients asked to be discharged due to detoxification dissatisfaction. Nursing staff also supported the use of this protocol because they felt patients were less agitated and irritable, which helped reduce one-on-one monitoring, use of restraints, patient fights, staff time, and potential staff/patient injuries. A review of historical data from the patients admitted to this trial revealed that those who had been previously detoxified at our facility (primarily with clonidine) more frequently requested early discharges (56% vs. 15%) and concomitant medications (24 units vs. 13 units), supporting the hypothesis that buprenorphine was beneficial and well-tolerated. Future research will focus on collecting objective data to support these observations.

Study limitations include a small sample size and open label design without a control group. A little less than half the patients were treated with psychotropic medications. However, it is unlikely that this therapy contributed greatly to the resolution of psychiatric symptoms, other than insomnia, due to the short treatment duration. This study was not conducted on a research unit. Consequently, while nursing staff were trained to complete the CINA scale, there may not have been consistent interrater reliability. However, these authors believe that this treatment environment probably more closely mimics other urban inpatient facilities than a research setting might. Finally, although illicit drug use was not objectively monitored, patients were evaluated for subjective symptoms of intoxication by nursing staff and remained on a locked psychiatric unit throughout the detoxification. Many of these limitations are consistent with what would be expected in nonresearch setting (Wells, 1999). A larger study may further substantiate the findings.

In conclusion, this trial suggests that injectable buprenorphine administered sublingually for 3 days appeared to be beneficial in preventing heroin withdrawal symptoms, well-tolerated, and accepted by a psychiatric inpatient population at an inner city hospital. Future research should compare this agent to standard treatments such as clonidine and methadone in a similar setting and investigate the transition to long-term substance abuse and psychiatric treatment.

Acknowledgments

No financial support was provided for conducting this study or preparing this manuscript. The authors would like to acknowledge Rolley E. Johnson, Pharm.D., for his contributions in selecting the dosage form administration for the study and Robert Walsh, Chief of the Regulatory Branch of the Division of Treatment Research and Development of NIDA, for providing expertise on regulatory issues in medications development.

Footnotes

Based on a protocol suggested by R. E. Johnson, Pharm.D. (Personal communication, 1998).

References

- Amass L, Kamien JB, Mikulich SK. Efficacy of daily and alternate-day dosing regimens with the combination buprenorphinenaloxone tablet. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;58:143–152. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blennow G, Fergusson A, Medvedeo A. Buprenorphine as a new alternative for detoxification of heroin addicts. Laekartidningen. 2000;97:1830–1833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooner RK, King VL, Kidorf M, Schmidt CW, Bigelow GE. Psychiatric and substance use comorbidity among treatment-seeking opioid abusers. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54(1):71–80. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830130077015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheskin LJ, Fudala PJ, Johnson RE. A controlled comparison of buprenorphine and clonidine for acute detoxification from opioids. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1994;36:115–121. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L. Dual diagnosis of substance abuse in schizophrenia: prevalence and impact on outcomes. Schizophrenia Research. 1999;35(Suppl):93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L, McNary S, Lehman AF. Remission of substance use disorder among psychiatric inpatients with mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:239–243. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Abraham M, Alpert J, Nierenberg AA, Pava JA, Rosenbaum JF. Gender differences in Axis I comorbidity among depressed outpatients. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1996;38:129–133. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(96)00004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowing L, Ali R, White J. Opioid antagonists and adrenergic agonists for the management of opioid withdrawal. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2000a;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002021. CD002021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowing L, Ali R, White J. Buprenorphine for the management of opioid withdrawal (Cochrane Review) The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2000b;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002025. CD002025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman JJ, Lalani S, Magluilo J, Levine B, Darwin WD. Human pharmacokinetics of intravenous, sublingual, and buccal buprenorphine. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 1996;20(6):369–378. doi: 10.1093/jat/20.6.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange WR, Fudala PJ, Dax EM, Johnson RE. Safety and side-effects of buprenorphine in the clinical management of heroin addiction. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1990;26:19–28. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(90)90078-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZM, Cai ZJ, Wang XP, Ge Y, Li CM. Rapid detoxification of heroin dependence by buprenorphine. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 1997;18(2):112–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya ID, Svikis D, Marcus SC, Suarez A, Tanielian T, Pincus HA. Psychiatric care of patients with depression and comorbid substance use disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2000;61:698–705. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n0917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigam AK, Ray R, Tripathi BM. Buprenorphine in opiate withdrawal: a comparison with clonidine. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1993;10:391–394. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90024-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor PG, Carroll KM, Shi JM, Schottenfeld RS, Kosten TR, Rounsaville BJ. Three methods of opioid detoxification in a primary care setting. A randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1997;127:526–530. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-7-199710010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peachey JE, Lei H. Assessment of opioid dependence with naloxone. British Journal of Addiction. 1988;83:193–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb03981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RachBeisel J, Scott J, Dixon L. Co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders: a review of recent research. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50:1427–1434. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.11.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strain EC, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA, Stitzer ML. Moderate- vs high-dose methadone in the treatment of opioid dependence: a randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281:1000–1005. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.11.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbricht A, Montoya ID, Hoover DR, Demuth KL, Chiang CT, Preston KL. Naltrexone shortened opioid detoxification with buprenorphine. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1999;56:181–190. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SL, Preston KL, Stitzer ML, Cone EJ, Bigelow GE. Clinical pharmacology of buprenorphine: ceiling effects at high doses. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 1994;55:569–580. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1994.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KB. Treatment research at the crossroads: the scientific interface of clinical trials and effectiveness research. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(1):5–10. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]