Abstract

All T cell functions require establishing contacts with other cells. In the last ten years, the immunological synapse, the contact-site between T cells and their partners, has been the object of numerous investigations and recent advances in imaging technologies have provided significant insights into the mechanism of immunological synapse formation and its functional outcomes. Considering all the available data, the immunological synapse can be defined as a dynamic structure, formed between a T cell and one or more antigen-presenting cells, showing lipid and protein segregation, signaling compartmentalization, and bidirectional information exchange though soluble and membrane-bound transmitters. In this review, we present the current views on the immunological synapse and discuss about some interesting unresolved questions.

Key words: T lymphocyte, immunological synapse, signaling, microcluster, TCR, lipid raft, costimulation

Introduction

T lymphocytes are activated when their T-cell receptors (TCRs) recognize and interact with specific antigenic complexes formed by antigen-derived peptides bound to integral membrane proteins encoded by the class I or class II genes of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). TCR ligands are therefore not soluble but presented on the surface of an antigen-presenting cell (APC). Since a single APC presents on its membrane many different combinations of peptide-MHC (pMHC) molecules, the number of specific antigenic complexes for a T cell can be very low (10–100).1–3 Thus, the elaborate process of T-cell activation, resulting in a variety of cellular responses, including proliferation, secretion of cytokines and cytotoxic mediators, can be initiated by the interaction of TCRs with very few ligands. Moreover, T cells must be able to discriminate precisely between an infectious stimulus and a non-infectious one, and tune their response in accordance with the molecular context in which the antigen is presented. Thus, whereas the interaction between an individual TCR and its ligand occurs over a time-frame of a few seconds, the interaction between a single T cell-APC pair can be sustained for several hours.4 During the prolonged interaction with APCs, the T lymphocyte can scan the surface of its partner, organize a specialized junction to compartmentalize signaling molecules and integrate signals continually delivered by its TCRs and costimulatory receptors. This long-lasting contact is necessary to ensure the sustained signaling that initiates and maintains gene transcription and promotes T-cell cycle progression.5,6

The fact that T cells are activated through an interaction with other cells has three intriguing consequences. First, several receptors are simultaneously triggered, allowing T cells to interpret the context in which antigen is presented. Second, signaling compartmentalization allows spatiotemporal segregation of signaling messengers, this segregation being necessary to activate specific downstream responses. Last, effector functions are localized toward the specific T-cell target.

During physiological T-cell stimulation, the organization of an “immunological synapse”—a complex specialized junction between the T cell and the APC—is pivotal to sustain and amplify signaling, and costimulatory molecules actively participate in this process by reorganizing actin cytoskeleton and recruiting lipid rafts into the T-APC junction.

The Immunological Synapse: Structure and Functions

The immunological synapse (IS) is a high-order, dynamic structure formed at the T-cell plasma membrane, as a consequence of the interaction between TCRs and pMHC molecules displayed at the APC surface.7

TCR triggering leads to a general relocation of T-cell molecules and organelles—a process termed polarization8—which involves complex asymmetric redistribution of membrane receptors and signaling molecules, reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton, and repositioning of the Golgi apparatus and the microtubule-organizing centre (MTOC). In particular, at the contact-region between T cell and its partner, major rearrangements are known to occur, leading to the organization of ‘supramolecular activation clusters’.9 Several in vitro imaging studies have shown that the formation of the mature IS requires the coordinated organization of signaling and cytoskeletal components into two distinct compartments within the T cell-APC contact site9,10: an inner ring termed central supramolecular activation cluster (cSMAC), highly enriched in TCR and pMHC complexes and signaling molecules (CD2, CD28, PKC-θ, Lck, Fyn, CD4 and CD8), which is formed within minutes of T cell-APC contact, and an outer ring termed peripheral supramolecular activation cluster (pSMAC), which contains the adhesion molecule leukocyte function-associated molecule-1 (LFA-1). In addition, there is a more peripheral region than pSMAC, which is called distal (d)SMAC, enriched in CD43 and CD45 molecules.11,12 The molecular segregation process begins as inverse of the pattern of the mature synapse, with a central cluster of adhesion molecules surrounded by a peripheral ring of engaged TCR13 and is thought to be dependent on actin-cytoskeleton rearrangements14: T-cell treatment with cytochalasin D leads to free diffusion of TCRs within the cell surface and lack of molecular segregation at the contact region.15

The expression “immunological synapse” was firstly associated to the specialized junction between a T lymphocyte and an APC, but it is now widely used to describe any effector-target cell contact site; its most important feature is the molecular organization of transmembrane proteins into activating clusters which results in integration of key signals delivered through several receptor systems.16

Whether the formation of a mature IS, with a well-defined cSMAC surrounded by a pSMAC, represents an absolute physiological requirement in T cell activation is still a controversial issue. Although cSMAC and pSMAC formation has been demonstrated in several experimental systems, such as CD4+ T cells stimulated by antigen-loaded B cells17 and in lipid planar bilayers containing pMHC complexes as artificial models of APC,18 there are indeed productive interactions that do not result in cSMAC formation. Thus, multi-focal synapses, characterized by a pSMAC and multiple cSMACs, have been described during interactions between thymocytes and thymic epithelial cells19–20 or CD8+ lymphocytes and their targets.21–22 When dendritic cells (DCs) were used as APCs, both “classical” and multi-focal synapses have been observed,23–24 even though T cell-DC interactions are in general less stable than the T-B cell ones, and more dependent on APC cytoskeleton.25 Considering the great diversity of possible structures, current terminology refers to an IS as the contact region between T cells and their partners during prolonged interactions.

cSMAC formation observed in productively activated T cells has been initially reported as involved in early T-cell signaling events by driving receptor aggregation.13 However, it has been proved later that TCR signaling can be initiated before the organization of detectable activation clusters26 suggesting that, rather than being a prerequisite for TCR signaling, IS represents a complex structure consequent to TCR stimulation. The idea that the cSMAC is not involved in the primary signaling for T-cell activation is supported by the correlation between the inability to form a mature IS observed in CD2-associated protein (CD2AP) deficient mice and T-cell hyper-responsiveness.27 Binding of CD2AP to the cytoplasmic domain of CD2 is induced by T-cell activation and is required for receptor clustering at the T cell-APC contact region.28 In the absence of CD2AP, T cells show impaired TCR recycling and/or degradation,29 suggesting a role for cSMAC in TCR downregulation and in signal exhaustion. This theory is supported by the recent observation that lysobisphosphatidic acid (LBPA), a lipid generated in multi-vescicular bodies in late lysosomal pathway, is found in proximity of most cSMACs but not in the peripheral T cell-APC contact region.30

Spatiotemporal segregation, integration and balancing of signaling are likely the main IS functions. A single signaling pathway can often modulate a wide variety of cellular events, indicating that spatiotemporal segregation of messengers plays a key role in activating specific downstream responses. The polarized and compartmentalized nature of the T-cell IS may thus facilitate local signaling, leading to specific cellular responses at specific location and times. Establishing checkpoints for signaling is also a very important aspect in T-cell activation. The activating and inhibitory molecular interactions have half-lives in the order of seconds,31,32 while the duration of signaling that is required to achieve T-cell priming ranges from few to several hours. In addition, physiological T-cell activation is generally achieved by very few antigenic complexes on the APC, suggesting that signaling amplification is an important requirement for T-cell priming. Recent studies demonstrated recruitment of low-affinity self-pMHC complexes into the IS of the APC, where they may contribute to T cell activation by providing low levels of additive signaling.33,34

Another possible role for the IS is favoring polarized secretion of cytokines or cytotoxic granules toward the T-cell partner/target. In a polarized, IS-forming T cell trafficking of vesicles is directed to the T cell-APC contact region and this may be important to facilitate T-cell functions. However, recent evidence indicated that polarized secretion is not a general rule. In CD4+ T cells, while IL-2 and IFNγ are indeed secreted in a polarized fashion toward the APC, other cytokines, such as IL-4 and TNF, or chemokines are secreted in a multidirectional manner.35 In addition, the release of lytic granules by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) does not require formation of a mature IS,36–38 can simultaneously occur at distinct sites of the T cell and, at least in vitro, can be uncoupled, in terms of time and space, with the stable, stimulatory synapse.39

CD28 Costimulation: Building an IS

Several receptors are stimulated by their ligands during the sustained T cell-APC interaction. Although the classical “two-signals” model of T-cell activation—proposing that T-cell priming requires “signal one” delivered by the TCR and “signal two” by CD28, in whose absence TCR stimulation result in T-cell anergy—can be considered obsolete, it is however clear that TCR-signaling amplification by CD28 plays a key role under physiological conditions of T-cell activation.40

Ligand-dependent CD28 recruitment into the cSMAC has been described,41 although CD28 signaling starts prior to cSMAC formation.42

CD28 is required for induction of gene transcription and is responsible of lowering T-cell threshold of activation, allowing T-cell priming by few antigenic complexes,43 suggesting that the molecule acts as an enhancer of early TCR signaling.44 By reorganizing lipid rafts and regulating the actin-cytoskeleton rearrangements,45–47 CD28 recruits signaling molecules such as Lck and PKC-θ into the IS, thus generating an environment where signal transduction is organized and amplified.48–50 In support of this role of CD28, it has been recently shown that CD28 in-trans costimulation fails to induce IL-2 transcription.51

The C-terminal proline motif of CD28 seems to be required for the costimulatory function of this molecule52,53 and is responsible for CD28-mediated lipid rafts recruitment into the IS.49 The same domain mediates association of CD28 with filamin-A (FLNa), an actin-binding protein with signaling-scaffold properties that accumulates at the IS in response to CD28 coligation.47 Interestingly, FLNa knockdown in human T lymphocytes results in loss of both lipid-raft recruitment into the IS and CD28 costimulation, whereas anti-CD3 induced response, as measured by IFNγ production, is not affected.47

While selective accumulation of lipid microdomains at the IS has been clearly established, the role of rafts in T-cell activation is still under investigation. A prevailing model suggests that raft redistribution influences the segregation of signaling proteins required in T-cell activation, thus favoring spatiotemporal compartmentalization of signaling.48,54,55 Recently, this hypothesis was confirmed by a study on the transmembrane tyrosine-phosphatase CD45, showing that CD45 partitioning into rafts dictates whether the phosphatase functions as a negative or positive regulator of T-cell activation.56

During lymphocyte activation, lipid rafts may function as platforms for the formation of multi-component transduction complexes. Indeed, these microdomains are constitutively enriched in proteins involved in the early phases of TCR signaling, such as the Src-family kinases Lck and Fyn, the adapter protein LAT, phosphoprotein associated with glycosphingolipid-enriched domains (PAG) or Csk-activating protein (Cbp) and Lck-interacting molecule (LIME).57 In addition, the composition of raft-associated proteins changes after T-cell stimulation, suggesting that rafts are dynamic platforms for T-cell signaling. Finally, lipids raft may be involved in regulating membrane elasticity that, in turn, controls the fitting of the T cell-APC at the IS.57

The New Concepts

Microclusters: Signaling units at the IS.

As already mentioned, the organization of a mature IS, with defined c- and pSMACs, is not required for TCR signaling. Indeed, recent evidence indicate that microclusters of signaling molecules, at the periphery of the IS, are responsible for initiating and maintaining T-cell activation.58,59 TCR microclusters contain key signaling molecules, such as Lck, Zap70, LAT and SLP-76 and are responsible of tyrosine phosphorylation and calcium fluxing in an actin polymerization-dependent manner. The generation of these early signaling events occurs within seconds after T-cell contact with a planar bilayer used as artificial model of APC60,61 and with B cells,59 suggesting a non-uniform distribution of TCR and MHC molecules on the cell surface.62,63 In agreement, clustered pMHC molecules inserted in planar lipid bilayers exert enhanced T-cell activation as compared with uniformly-distributed MHC ligands.64

A single-molecule-imaging analysis revealed that microclusters are relatively static, although their components are in a highly-dynamic state, moving in and out of the cluster.65 TCR microclusters move independently toward the center of the IS and fuse to form large clusters: the interconnected large clusters become then immobilized at the center of the IS, and form the TCR-cSMAC.61 Migration towards the centre to form cSMAC correlates with loss of their association with adaptors molecules and loss of phosphotyrosine activity,59 while retention of microclusters in the periphery is associated with sustained calcium influx and phosphotyrosine activity.58,61 TCR microclusters continue to form after cSMAC organization and are sites of TCR signaling, based on the recruitment of key signaling molecules.62 This model suggests that early-signaling events provide a highly-dynamic microenviroment enabling large-scale molecular reorganization processes observed in the formation of a mature synapse. The long-lasting signaling required for T cell activation seems thus to be provided by newly formed microclusters at the cell-cell contact site.

Whereas cSMAC size is directly correlated with antigen density, the size of microclusters appears to be independent of the antigen concentration.61 The mechanisms of TCR-microcluster formation are still unknown, although the actin cytoskeleton seems to be involved. Latruculin A inhibits movement of preexisting microclusters and formation of new ones, without disturbing already-formed microclusters and cSMAC. This correlates with a reduction in the ongoing calcium elevation.61

In vivo imaging: From stable to dynamic IS.

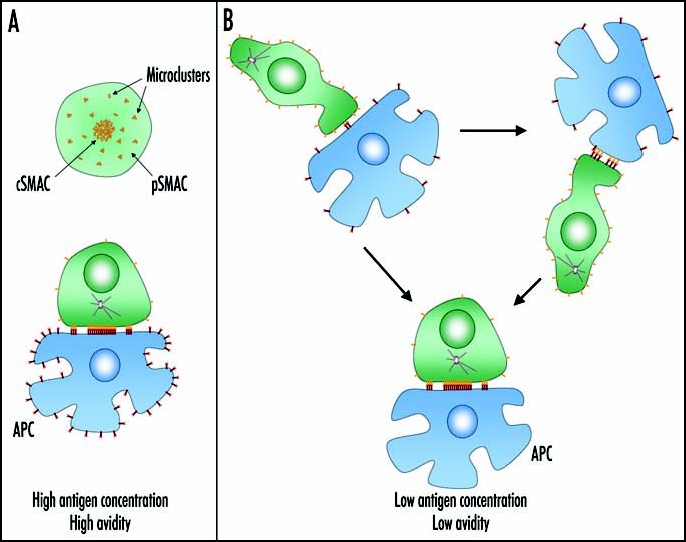

The fact that TCR-signaling microclusters are organized within seconds after T-cell interaction with APCs suggests to review the previous definition of IS, in favor of a new dynamic model. Recent sophisticated imaging techniques, permitting direct observation of T cell-DC interaction in lymph nodes,66–69 provided new insights in understanding the complex dynamics of in vivo T-cell activation. Two-photon microscopy analysis revealed that in vivo T cell-APC pairing occurs only after a long series of short encounters of rapidly moving T cells with numerous APCs. In lymph nodes, both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells may have transient, dynamic interactions with DCs69,70 before they choose the partner and form stable conjugates. However, it's only during this prolonged interaction that T cells are induced to proliferate and produce cytokines, indicating that productive T-cell activation corresponds to the formation of a stable IS.69 After this period, T cell-DC return to short-lived contacts. Thus, in contrast to what observed in vitro, T cell-APC interactions are highly dynamic during a first phase, corresponding to T-cell entrance into lymph node, and this may be strategic to find the right partner. Moreover, these data indicate that, even when in contact with antigen-specific DCs, T cells can be distracted by signals present in the environment, which prevent formation of stable pairs. This prolonged period of transient interactions is not observed when antigen is presented by many resident DCs,71 suggesting that antigen concentration regulates T cell-DC dynamics in vivo. As illustrated in Figure 1, when antigen is not limiting or when the TCR/pMHC interactions are characterized by high avidity, encounters between T cells and APCs likely result in quick formation of stable conjugates, followed by organization of classical IS. In contrast, when pMHC complexes are few and do not engage the TCR with high avidity, T cells may require several short-lived interactions with APCs before forming stable pairs.

Figure 1.

A dynamic immunological synapse. In vitro and in vivo experiments suggest that, depending on antigen concentration and/or TCR avidity, the encounter between T cells and APCs may rapidly result in the formation of a stable IS, described by a central signaling-silent TCR cluster and peripheral TCR signaling microclusters (A), or may be characterized by short-lived interactions finally culminating in formation of a stable conjugate (B). We speculate that TCR-pMHC interactions occurring during short-lived encounters induce receptor clustering and allow T cell activation by APCs carrying few specific pMHC complexes.

The concept that IS formation is a highly-dynamic process is confirmed by the observation that a single T cell can form ISs with different APCs at the same time, and finally polarize their secretory machinery toward the APC that is providing the strongest stimulus.72 This dynamic aspect may be extremely important in the case of CTLs, which can serially kill numerous target cells73 and may need rapid pairing with and detach from the target cells.74,75

Chemokines and their receptors: Soluble transmitters at the IS.

The in vivo data, showing T cells unable to form stable conjugates with APCs after entry in lymph nodes and hesitating between several potential partners, may be explained by the presence in the environment of chemoattractive signals competing with TCR stop signals.61,76 However, chemokines may have a different role during IS formation. Although the contribution of costimulatory molecules to IS formation has long been recognized, only recently chemokine receptors have been described as new T-cell costimulatory molecules.76 During T-cell activation, recruitment of CCR5 and CXCR4 chemokine receptors into the IS, by a mechanism requiring chemokine secretion by APCs, results in prolonged T cell-APC interaction, and facilitates T-cell activation by reinforcing T cell-APC pair attraction and delivering costimulatory signals.77 TCR activation leads to a major change in the signaling of chemokine receptors that, in this condition, couple preferentially to Gq/G11 instead of Gi,77 thus inducing cell adhesion rather than chemotaxis,78,79 either by enhancing LFA-1 affinity80,81 or by overriding Gi-mediated chemotactic signaling. In addition, Gq-mediated signaling also triggers the translocation of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) to the nucleus,82 providing another additional mechanism by which chemokine-receptor engagement at the IS may enhance T-cell activation.

A dual role for chemokines in T-cell activation has been therefore proposed76: while the presence of chemoattractant forces when T cells are searching for the right partner may indeed prevent T cell-APC pairing, production of chemokines by the APCs, and subsequent accumulation and trapping of Gq-coupled chemokine receptors at the IS, may represent a strategy to reinforce T cell-APC interaction and facilitate T-cell activation.

At the IS, chemokines may act as soluble transmitters allowing information exchange during contact between several types of immune cells, thus representing the functional equivalent of neurotransmitters at the neurological synapse.83

Future Research on the IS

Understanding the dynamic synapse.

Although the emerging imaging techniques are providing new insights into the dynamics involved in IS formation, further studies are necessary to elucidate several unresolved questions concerning events occurring at this level in vivo.

In lymph nodes, before conjugates turn stable, most T lymphocytes have dynamic interactions with DCs leading to upregulation of activation markers in a significant proportion of T cells, suggesting that productive TCR signaling is occurring. These results are compatible with a multiphasic, balanced model of activation, in which T cells integrate signals from dynamic short contacts with DCs in order to achieve polarization toward the “best” APC (Fig. 1). In vitro experiments, aimed at periodically blocking signal transduction in T cells interacting with APCs, have supported the idea that T cells can be activated by intermittent signals.84,85 However, the molecular changes that a T cell requires to choose one single APC, stop and organize a mature IS are still obscure.

In the absence of a stable interaction, transient TCR-signaling microclusters are probably organized at the membrane of T cell during its short-lived encounters with several APCs. Whether these transient microclusters are different, in terms of signaling, compared with those organized during a stable T cell-APC interaction is an interesting question to be addressed. In addition, it is tempting to speculate about the possible relation between the TCR-signaling microclusters organized upon antigen recognition and the multivalent architecture of the TCR/CD3 complex recently described.86 In particular, it would be interesting to evaluate whether TCR-signaling microclusters are preferentially assembled from mono- or multivalent TCR/CD3 complexes and what is the role of lipids and cytoskeletal proteins in stabilizing TCR nano- and microclusters.

The immunological synapse dissolution.

Once the IS between a T cell and an APC is formed, the interaction may be stable in the absence of disturbing influences but can be destroyed by cell division, death of the APC or external influences, such as chemokines. Recent progress has greatly increased the understanding of the T-cell orchestrated signaling networks that regulate the process of synapse formation. Yet, a major question concerning the mechanisms regulating IS disassembly remains unresolved. The mechanism proposed, but not completely elucidated, involves downmodulation of TCRs and adhesion molecules,87,88 upregulation and recruitment into the IS of receptors delivering inhibitory signals,89 and redistribution of molecules such as CD43, a cell-surface mucin that has been proposed to function as a negative regulator of T cell signaling, into the contact zone.90

One of the best-studied negative regulators of T cell activation is the cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4).91 Mice lacking CTLA-4 develop a severe autoimmune phenotype with organ destruction.92 How CTLA-4 suppresses excessive immune responses and autoimmunity is still unclear. Proposed mechanisms include ligand competition with the costimulatory molecule CD28, activation of inhibitory signaling pathways93 and effects on membrane lipid rafts.94 Recently, it has been shown that, in the presence of antigen, T cells expressing CTLA-4 continue their random migration at unchanged velocities, whereas CTLA-4-null T cells slow down and form long-lasting conjugates with APCs.95

Conclusions

The expression “immunological synapse” was used to underline the similarities between the junction formed by T cells with their partners and the specialized contact-region between neurons. Although the IS, in contrast to the neurological synapse, is not stable and is characterized by a bi-directional transmission of information between T cells and APCs, it is indeed a structurally and functionally compartmentalized area of the plasma membrane, in which communication between cells occurs through soluble and membrane-bound transmitters. During the last ten years, several laboratories have focused their studies on the IS, using imaging techniques often accompanied with classical biochemical or cell biology approaches. Importantly, in most of the cases, the IS study has not been a mere description of cell-cell interaction or molecular segregation, but it greatly contributed to our understanding of the T cell activation process. We believe that important insights may still stem from this area of study and further work is indeed needed to understand how analogic signals collected at the IS are converted in a digital-like signal determining the choice between T cell tolerance or activation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Marco Necci for graphics and Adelaida Sarukhan for critical reading of the manuscript. A.V. is supported by grants from Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC) and MIUR PRIN.

Abbreviations

- APC

antigen presenting cell

- CD

cluster designation

- cSMAC

central supramolecular activation clusters

- CTL

cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- CTLA 4

cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4

- DC

dendritic cell

- dSMAC

distal supramolecular activation cluster

- IS

immunological synapse

- LBPA

lysobisphosphatidic acid

- LFA 1

leukocyte function associated molecule 1

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- MTOC

microtubule organizing centre

- pSMAC

peripheral supramolecular activation cluster

- TCR

T cell receptor

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Cell Adhesion & Migration E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/celladhesion/abstract.php?id=3982

References

- 1.Harding CV, Unanue ER. Quantitation of antigen-presenting cell MHC class II/peptide complexes necessary for T-cell stimulation. Nature. 1990;346:574–576. doi: 10.1038/346574a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christinck ER, Luscher MA, Barber BH, Williams DB. Peptide binding to class I MHC on living cells and quantitation of complexes required for CTL lysis. Nature. 1991;352:67–70. doi: 10.1038/352067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sykulev Y, Joo M, Vturina I, Tsomides TJ, Eisen HN. Evidence that a single peptide-MHC complex on a target cell can elicit a cytolytic T cell response. Immunity. 1996;4:565–571. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80483-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mempel TR, Henrickson SE, Von Andrian UH. T-cell priming by dendritic cells in lymph nodes occurs in three distinct phases. Nature. 2004;427:154–159. doi: 10.1038/nature02238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Timmerman LA, Clipstone NA, Ho SN, Northrop JP, Crabtree GR. Rapid shuttling of NF-AT in discrimination of Ca2+ signals and immmunosuppression. Nature. 1996;383:837–840. doi: 10.1038/383837a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huppa JB, Gleimer M, Sumen C, Davis MM. Continuous T cell receptor signalling required for synapse maintenance and full effector potential. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:749–755. doi: 10.1038/ni951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis MM, Boniface JJ, Reich Z, Lyons D, Hampl J, Arden B, Chien Y. Ligand recognition by alpha beta T cell receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:523–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kupfer A, Dennert G, Singer SJ. Polarization of the Golgi apparatus and the microtubule-organizing center within cloned natural killer cells bound to their targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:7224–7228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.23.7224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monks CR, Freiberg BA, Kupfer H, Sciaky N, Kupfer A. Three-dimensional segregation of supramolecular activation clusters in T cells. Nature. 1998;395:82–86. doi: 10.1038/25764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee KH, Holdorf AD, Dustin ML, Chan AC, Allen PM, Shaw AS. T cell receptor signaling precedes immunological synapse formation. Science. 2002;295:1539–1542. doi: 10.1126/science.1067710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delon J, Kaibuchi K, Germain RN. Exclusion of CD43 from the immunological synapse is mediated by phosphorylation-regulated relocation of the cytoskeletal adaptor moesin. Immunity. 2001;15:691–701. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00231-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freiberg BA, Kupfer H, Maslanik W, Delli J, Kappler J, Zaller DM, Kupfer A. Staging and resetting T cell activation in SMACs. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:911–917. doi: 10.1038/ni836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grakoui A, Bromley SK, Sumen C, Davis MM, Shaw AS, Allen PM, Dustin ML. The immunological synapse: A molecular machine controlling T cell activation. Science. 1999;285:221–227. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dustin ML, Cooper JA. The immunological synapse and the actin cytoskeleton: Molecular hardware for T cell signaling. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:23–29. doi: 10.1038/76877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krummel MF, Sjaastad MD, Wulfing C, Davis MM. Differential clustering of CD4 and CD3zeta during T cell recognition. Science. 2000;289:1349–1352. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5483.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dustin ML, Shaw AS. Costimulation: Building an immunological synapse. Science. 1999;283:649–650. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5402.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monks CR, Freiberg BA, Kupfer H, Sciaky N, Kupfer A. Three-dimensional segregation of supramolecular activation clusters in T cells. Nature. 1998;395:82–86. doi: 10.1038/25764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groves JT, Dustin ML. Supported planar bilayers in studies on immune cell adhesion and communication. J Immunol Methods. 2003;278:19–32. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(03)00193-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hailman E, Burack WR, Shaw AS, Dustin ML, Allen PM. Immature CD4(+)CD8(+) thymocytes form a multifocal immunological synapse with sustained tyrosine phosphorylation. Immunity. 2002;16:839–848. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00326-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richie LI, Ebert PJ, Wu LC, Krummel MF, Owen JJ, Davis MM. Imaging synapse formation during thymocyte selection: Inability of CD3zeta to form a stable central accumulation during negative selection. Immunity. 2002;16:595–606. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00299-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Purbhoo MA, Irvine DJ, Huppa JB, Davis MM. T cell killing does not require the formation of a stable mature immunological synapse. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:524–530. doi: 10.1038/ni1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Keefe JP, Gajewski TF. Cutting edge: Cytotoxic granule polarization and cytolysis can occur without central supramolecular activation cluster formation in CD8+ effector T cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:5581–5585. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benvenuti F, Lagaudriere-Gesbert C, Grandjean I, Jancic C, Hivroz C, Trautmann A, Lantz O, Amigorena S. Dendritic cell maturation controls adhesion, synapse formation, and the duration of the interactions with naive T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2004;172:292–301. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brossard C, Feuillet V, Schmitt A, Randriamampita C, Romao M, Raposo G, Trautmann A. Multifocal structure of the T cell - Dendritic cell synapse. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1741–1753. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dustin ML, Tseng SY, Varma R, Campi G. T cell-dendritic cell immunological synapses. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:512–516. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wulfing C, Sumen C, Sjaastad MD, Wu LC, Dustin ML, Davis MM. Costimulation and endogenous MHC ligands contribute to T cell recognition. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:42–47. doi: 10.1038/ni741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee KH, Dinner AR, Tu C, Campi G, Raychaudhuri S, Varma R, Sims TN, Burack WR, Wu H, Wang J, Kanagawa O, Markiewicz M, Allen PM, Dustin ML, Chakraborty AK, Shaw AS. The immunological synapse balances T cell receptor signaling and degradation. Science. 2003;302:1218–1222. doi: 10.1126/science.1086507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dustin ML, Olszowy MW, Holdorf AD, Li J, Bromley S, Desai N, Widder P, Rosenberger F, van der Merwe PA, Allen PM, Shaw AS. A novel adaptor protein orchestrates receptor patterning and cytoskeletal polarity in T-cell contacts. Cell. 1998;94:667–677. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81608-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim JM, Wu H, Green G, Winkler CA, Kopp JB, Miner JH, Unanue ER, Shaw AS. CD2-associated protein haploinsufficiency is linked to glomerular disease susceptibility. Science. 2003;300:1298–1300. doi: 10.1126/science.1081068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varma R, Campi G, Yokosuka T, Saito T, Dustin ML. T cell receptor-proximal signals are sustained in peripheral microclusters and terminated in the central supramolecular activation cluster. Immunity. 2006;25:117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iezzi G, Karjalainen K, Lanzavecchia A. The duration of antigenic stimulation determines the fate of naive and effector T cells. Immunity. 1998;8:89–95. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80461-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friedl P, den Boer AT, Gunzer M. Tuning immune responses: Diversity and adaptation of the immunological synapse. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:532–545. doi: 10.1038/nri1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Irvine DJ, Purbhoo MA, Krogsgaard M, Davis MM. Direct observation of ligand recognition by T cells. Nature. 2002;419:845–849. doi: 10.1038/nature01076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krogsgaard M, Li QJ, Sumen C, Huppa JB, Huse M, Davis MM. Agonist/endogenous peptide-MHC heterodimers drive T cell activation and sensitivity. Nature. 2005;434:238–243. doi: 10.1038/nature03391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huse M, Lillemeier BF, Kuhns MS, Chen DS, Davis MM. T cells use two directionally distinct pathways for cytokine secretion. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:247–255. doi: 10.1038/ni1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Purbhoo MA, Irvine DJ, Huppa JB, Davis MM. T cell killing does not require the formation of a stable mature immunological synapse. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:524–530. doi: 10.1038/ni1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Keefe JP, Gajewski TF. Cutting edge: Cytotoxic granule polarization and cytolysis can occur without central supramolecular activation cluster formation in CD8+ effector T cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:5581–5585. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faroudi M, Utzny C, Salio M, Cerundolo V, Guiraud M, Muller S, Valitutti S. Lytic versus stimulatory synapse in cytotoxic T lymphocyte/target cell interaction: Manifestation of a dual activation threshold. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14145–14150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2334336100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiedemann A, Depoil D, Faroudi M, Valitutti S. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes kill multiple targets simultaneously via spatiotemporal uncoupling of lytic and stimulatory synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10985–10990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600651103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shahinian A, Pfeffer K, Lee KP, Kundig TM, Kishihara K, Wakeham A, Kawai K, Ohashi PS, Thompson CB, Mak TW. Differential T cell costimulatory requirements in CD28-deficient mice. Science. 1993;261:609–612. doi: 10.1126/science.7688139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grakoui A, Bromley SK, Sumen C, Davis MM, Shaw AS, Allen PM, Dustin ML. The immunological synapse: A molecular machine controlling T cell activation. Science. 1999;285:221–227. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andres PG, Howland KC, Dresnek D, Edmondson S, Abbas AK, Krummel MF. CD28 signals in the immature immunological synapse. J Immunol. 2004;172:5880–5886. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.5880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Viola A, Lanzavecchia A. T cell activation determined by T cell receptor number and tunable thresholds. Science. 1996;273:104–106. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Viola A. The amplification of TCR signaling by dynamic membrane microdomains. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:322–327. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)01938-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Michel F, Mangino G, Attal-Bonnefoy G, Tuosto L, Alcover A, Roumier A, Olive D, Acuto O. CD28 utilizes Vav-1 to enhance TCR-proximal signaling and NF-AT activation. J Immunol. 2000;165:3820–3829. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salazar-Fontana LI, Barr V, Samelson LE, Bierer BE. CD28 engagement promotes actin polymerization through the activation of the small Rho GTPase Cdc42 in human T cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:2225–2232. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tavano R, Contento RL, Baranda SJ, Soligo M, Tuosto L, Manes S, Viola A. CD28 interaction with filamin-A controls lipid raft accumulation at the T-cell immunological synapse. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1270–1276. doi: 10.1038/ncb1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Viola A, Schroeder S, Sakakibara Y, Lanzavecchia A. T lymphocyte costimulation mediated by reorganization of membrane microdomains. Science. 1999;283:680–682. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5402.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tavano R, Gri G, Molon B, Marinari B, Rudd CE, Tuosto L, Viola A. CD28 and lipid rafts coordinate recruitment of Lck to the immunological synapse of human T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2004;173:5392–5397. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang J, Lo PF, Zal T, Gascoigne NR, Smith BA, Levin SD, Grey HM. CD28 plays a critical role in the segregation of PKC theta within the immunologic synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9369–9373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142298399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanchez-Lockhart M, Miller J. Engagement of CD28 outside of the immunological synapse results in up-regulation of IL-2 mRNA stability but not IL-2 transcription. J Immunol. 2006;176:4778–4784. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holdorf AD, Green JM, Levin SD, Denny MF, Straus DB, Link V, Changelian PS, Allen PM, Shaw AS. Proline residues in CD28 and the Src homology (SH)3 domain of Lck are required for T cell costimulation. J Exp Med. 1999;190:375–384. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.3.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tai X, Cowan M, Feigenbaum L, Singer A. CD28 costimulation of developing thymocytes induces Foxp3 expression and regulatory T cell differentiation independently of interleukin 2. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:152–162. doi: 10.1038/ni1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rodgers W, Rose JK. Exclusion of CD45 inhibits activity of p56lck associated with glycolipid-enriched membrane domains. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1515–1523. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Janes PW, Ley SC, Magee AI. Aggregation of lipid rafts accompanies signaling via the T cell antigen receptor. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:447–461. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.2.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang M, Moran M, Round J, Low TA, Patel VP, Tomassian T, Hernandez JD, Miceli MC. CD45 signals outside of lipid rafts to promote ERK activation, synaptic raft clustering, and IL-2 production. J Immunol. 2005;174:1479–1490. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Manes S, Viola A. Lipid rafts in lymphocyte activation and migration. Mol Membr Biol. 2006;23:59–69. doi: 10.1080/09687860500430069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mossman KD, Campi G, Groves JT, Dustin ML. Altered TCR signaling from geometrically repatterned immunological synapses. Science. 2005;310:1191–1193. doi: 10.1126/science.1119238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yokosuka T, Sakata-Sogawa K, Kobayashi W, Hiroshima M, Hashimoto-Tane A, Tokunaga M, Dustin ML, Saito T. Newly generated T cell receptor microclusters initiate and sustain T cell activation by recruitment of Zap70 and SLP-76. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1253–1262. doi: 10.1038/ni1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Campi G, Varma R, Dustin ML. Actin and agonist MHC-peptide complex-dependent T cell receptor microclusters as scaffolds for signaling. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1031–1036. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Varma R, Campi G, Yokosuka T, Saito T, Dustin ML. T cell receptor-proximal signals are sustained in peripheral microclusters and terminated in the central supramolecular activation cluster. Immunity. 2006;25:117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kropshofer H, Spindeldreher S, Rohn TA, Platania N, Grygar C, Daniel N, Wolpl A, Langen H, Horejsi V, Vogt AB. Tetraspan microdomains distinct from lipid rafts enrich select peptide-MHC class II complexes. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:61–68. doi: 10.1038/ni750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schamel WW, Arechaga I, Risueno RM, van Santen HM, Cabezas P, Risco C, Valpuesta JM, Alarcon B. Coexistence of multivalent and monovalent TCRs explains high sensitivity and wide range of response. J Exp Med. 2005;202:493–503. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Giannoni F, Barnett J, Bi K, Samodal R, Lanza P, Marchese P, Billetta R, Vita R, Klein MR, Prakken B, Kwok WW, Sercarz E, Altman A, Albani S. Clustering of T cell ligands on artificial APC membranes influences T cell activation and protein kinase C theta translocation to the T cell plasma membrane. J Immunol. 2005;174:3204–3211. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Douglass AD, Vale RD. Single-molecule microscopy reveals plasma membrane microdomains created by protein-protein networks that exclude or trap signaling molecules in T cells. Cell. 2005;121:937–950. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sumen C, Mempel TR, Mazo IB, von Andrian UH. Intravital microscopy: Visualizing immunity in context. Immunity. 2004;21:315–329. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hugues S, Fetler L, Bonifaz L, Helft J, Amblard F, Amigorena S. Distinct T cell dynamics in lymph nodes during the induction of tolerance and immunity. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1235–1242. doi: 10.1038/ni1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lindquist RL, Shakhar G, Dudziak D, Wardemann H, Eisenreich T, Dustin ML, Nussenzweig MC. Visualizing dendritic cell networks in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1243–1250. doi: 10.1038/ni1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mempel TR, Henrickson SE, Von Andrian UH. T-cell priming by dendritic cells in lymph nodes occurs in three distinct phases. Nature. 2004;427:154–159. doi: 10.1038/nature02238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miller MJ, Hejazi AS, Wei SH, Cahalan MD, Parker I. T cell repertoire scanning is promoted by dynamic dendritic cell behavior and random T cell motility in the lymph node. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:998–1003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306407101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shakhar G, Lindquist RL, Skokos D, Dudziak D, Huang JH, Nussenzweig MC, Dustin ML. Stable T cell-dendritic cell interactions precede the development of both tolerance and immunity in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:707–714. doi: 10.1038/ni1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Depoil D, Zaru R, Guiraud M, Chauveau A, Harriague J, Bismuth G, Utzny C, Muller S, Valitutti S. Immunological synapses are versatile structures enabling selective T cell polarization. Immunity. 2005;22:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cerottini JC, Brunner KT. Cell-mediated cytotoxicity, allograft rejection, and tumor immunity. Adv Immunol. 1974;18:67–132. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60308-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Poenie M, Tsien RY, Schmitt-Verhulst AM. Sequential activation and lethal hit measured by [Ca2+]i in individual cytolytic T cells and targets. EMBO J. 1987;8:2223–2232. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02494.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Isaaz S, Baetz K, Olsen K, Podack E, Griffiths GM. Serial killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes: T cell receptor triggers degranulation, refilling of the lytic granules and secretion of lytic proteins via a non-granule pathway. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1071–1079. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Viola A, Contento RL, Molon B. T cells and their partners: The chemokine dating agency. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:421–427. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Molon B, Gri G, Bettella M, Gomez-Mouton C, Lanzavecchia A, Martinez-A C, Manes S, Viola A. T cell costimulation by chemokine receptors. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:465–471. doi: 10.1038/ni1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mellado M, Rodriguez-Frade JM, Manes S, Martinez-A C. Chemokine signaling and functional responses: The role of receptor dimerization and TK pathway activation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:397–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rodriguez-Frade JM, Mellado M, Martinez-A C. Chemokine receptor dimerization: Two are better than one. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:612–617. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tybulewicz VL. Chemokines and the immunological synapse. Immunology. 2002;106:287–288. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01467.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shamri R, Grabovsky V, Gauguet JM, Feigelson S, Manevich E, Kolanus W, Robinson MK, Staunton DE, von Andrian UH, Alon R. Lymphocyte arrest requires instantaneous induction of an extended LFA-1 conformation mediated by endothelium-bound chemokines. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:497–506. doi: 10.1038/ni1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Boss V, Talpade DJ, Murphy TJ. Induction of NFAT-mediated transcription by Gq-coupled receptors in lymphoid and nonlymphoid cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10429–10432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Trautmann A. Chemokines as immunotransmitters? Nat Immunol. 2005;6:427–428. doi: 10.1038/ni0505-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rachmilewitz J, Lanzavecchia A. A temporal and spatial summation model for T-cell activation: Signal integration and antigen decoding. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:592–595. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02342-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Faroudi M, Zaru R, Paulet P, Muller S, Valitutti S. Cutting edge: T lymphocyte activation by repeated immunological synapse formation and intermittent signaling. J Immunol. 2003;171:1128–1132. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schamel WW, Arechaga I, Risueno RM, van Santen HM, Cabezas P, Risco C, Valpuesta JM, Alarcon B. Coexistence of multivalent and monovalent TCRs explains high sensitivity and wide range of response. J Exp Med. 2005;202:493–503. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liu H, Rhodes M, Wiest DL, Vignali DA. On the dynamics of TCR: CD3 complex cell surface expression and downmodulation. Immunity. 2000;13:665–675. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mazerolles F, Barbat C, Hivroz C, Fischer A. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase participates in p56(lck)/CD4-dependent down-regulation of LFA-1-mediated T cell adhesion. J Immunol. 1996;157:4844–4854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Egen JG, Allison JP. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 accumulation in the immunological synapse is regulated by TCR signal strength. Immunity. 2002;16:23–35. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Allenspach EJ, Cullinan P, Tong J, Tang Q, Tesciuba AG, Cannon JL, Takahashi SM, Morgan R, Burkhardt JK, Sperling AI. ERM-dependent movement of CD43 defines a novel protein complex distal to the immunological synapse. Immunity. 2001;15:739–750. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00224-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Teft WA, Kirchhof MG, Madrenas J. A molecular perspective of CTLA-4 function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:65–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tivol EA, Borriello F, Schweitzer AN, Lynch WP, Bluestone JA, Sharpe AH. Loss of CTLA-4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA-4. Immunity. 1995;3:541–547. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chuang E, Fisher TS, Morgan RW, Robbins MD, Duerr JM, Vander Heiden MG, Gardner JP, Hambor JE, Neveu MJ, Thompson CB. The CD28 and CTLA-4 receptors associate with the serine/threonine phosphatase PP2A. Immunity. 2000;13:313–322. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Martin M, Schneider H, Azouz A, Rudd CE. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 and CD28 modulate cell surface raft expression in their regulation of T cell function. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1675–1681. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.11.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schneider H, Downey J, Smith A, Zinselmeyer BH, Rush C, Brewer JM, Wei B, Hogg N, Garside P, Rudd CE. Reversal of the TCR stop signal by CTLA-4. Science. 2006;313:1972–1975. doi: 10.1126/science.1131078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]