Abstract

The plant parasitic nematode Heterodera schachtii invades the roots of Arabidopsis thaliana to induce nematode feeding structures in the central cylinder. During nematode development, the parasites feed exclusively from these structures. Thus, high sugar import and specific sugar processing of the affected plant cells is crucial for nematode development. In the present work, we found starch accumulation in nematode feeding structures and therefore studied the expression genes involved in the starch metabolic pathway. The importance of starch synthesis was further shown using the Atss1 mutant line. As it is rather surprising to find starch accumulation in cells characterised by a high nutrient loss, we speculate that starch serves as long- and short-term carbohydrate storage to compensate the staggering feeding behaviour of the parasites.

Key words: Heterodera schachtii, Arabidopsis, nematode, starch metabolism, syncytia

The obligate plant parasitic nematode Heterodera schachtii is entirely dependent on a system of nutrient supply provided by the plant. Host plants—among those the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana—have to endure invasion of second stage juveniles and the establishment of nematode feeding structures in the plant's vascular cylinder. For induction of the specific feeding structures, the juveniles pierce one single plant cell with their stylet and inject secretions, thus triggering the formation of a syncytium by local cell walls dissolutions.1 Further, the central vacuole of the syncytial cells disintegrates, nuclei enlarge and many organelles proliferate.1 About 24 hours after feeding site induction, the nematode juveniles start feeding in repetitive cycles.2 Syncytia have previously been described as strong sinks in the plant's transport system.3 Thus, in the recent years several studies were carried out to discover solute supply to syncytial cells.4–7 To our present knowledge, syncytia are symplasmically isolated in the first days of nematode development. During that period, the nematodes depend on transport protein activity in the syncytia plasmamembranes. At later stages plasmodesmata appear to open to the phloem elements, facilitating symplasmic transport.

Incoming solutes may either be taken up by the feeding nematode or are synthesised and catalysed by the syncytium's metabolism. Due to the microscopically observable high density of the cytosol1 and the increased osmotic pressure,8 syncytia appear to accumulate high solute concentrations. In fact, significantly increased sucrose levels have been found in syncytia in comparison to non-infected control roots.7 In case of high sugar levels, plant cells generally synthesize starch in order to reduce emerging osmotic stress.9 The aim of the work of Hofmann et al.,10 was to elucidate if starch is utilised as carbohydrate storage in nematode-induced syncytia and to study expression of genes involved in starch metabolism with an emphasis on nematode development.

Starch levels of nematode induced syncytia and roots of non-infected plants grown on sand/soil culture were measured by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The results showed a high accumulation of starch in syncytia that was steadily decreasing during nematode development. The accumulation of starch could further be localised within syncytial cells by electron microscopy. Based on these results, we studied the gene expression of the starch metabolic pathway by Affymetrix gene chip analysis. About half of the 56 involved genes were significantly upregulated in syncytia compared to the control and only two genes were significantly downregulated. Thus, the high induction of the gene expression is consistent with the high starch accumulation. Finally, we applied an Arabidopsis mutant line lacking starch synthase I expression that has been described previously.11 Starch synthase I was the second highest upregulated gene in syncytia. It catalyses the linkage of ADP-glucose to the non-reducing end of an a-glucan, forming the linear glucose chains of amylopectin. In a nematode infection assay we were able to prove the significant importance of the gene for nematode development.

With the presented results, we can unambiguously prove the accumulation of starch and the induction of the gene expression of the starch metabolic pathway in nematode-induced syncytia. The primary question however is: why do syncytia accumulate soluble sugars and starch although their metabolism is highly induced and nematodes withdraw solutes during continuously repeating feeding cycles?

One explanation may be found where least expected—in nematode feeding. It is the feeding activity that induced solute import mechanisms into syncytia resulting in a newly formed sink tissue. However, during moulting events to the third, the fourth juvenile stage and to the adult stage nematodes interrupt feeding for about 20 hours.2 During this period sugar supply mechanisms will most probably not be altered thus leading to increasing levels of sugars in the syncytium. Starch may serve as short-term carbohydrate buffering sugar excess. Further, starch may serve as long-term carbohydrate storage during nematode development. In the early stages of juvenile development nematodes withdraw considerably small quantities (about 0,8-times the syncytium volume a day).12 At later stages, nutrient demand increases so that adult fertilised females require 4-times the syncytium volume per day in order to accomplish egg production.12 Thus, excessive sugar supply in the first days may be accumulated as starch that gets degraded at later stages when more energy is required from the parasites. Consequently, starch reserve serves as both short-term and long-term carbohydrate storage in nematode-induced syncytia in order to buffer changing feeding pattern of the parasites.

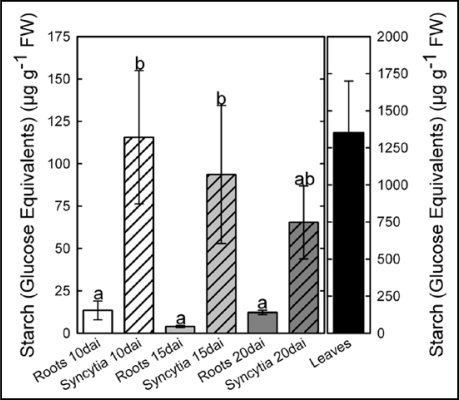

Figure 1.

Arabidopsis wild-type Columbia-0 plants were grown in sand/soil culture. Nematode-induced syncytia and non-infected control roots were harvested at 10, 15 and 20 days after inoculation (dai) and starch content was measured as glucose (Glc) equivalents. Values are means ± SE, n = 3. Different letters indicate significant variations (p < 0.05). © ASPB

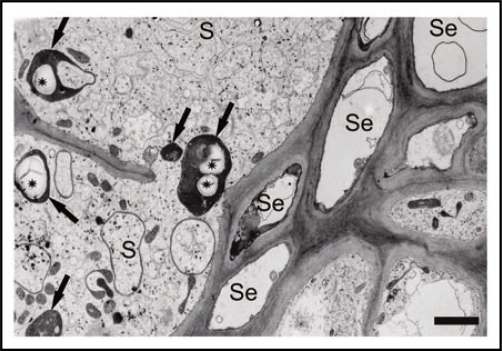

Figure 2.

Transmission electron microscope picture of a cross-section of a syncytium associated with female fourth stage juvenile (H. schachtii) induced in roots of Arabidopsis. Bar = 2 µm. S, syncytium; Se, sieve tube; arrow, plastid; asterisk, starch granule. © ASPB

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Plant Signaling & Behavior E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/6075

References

- 1.Golinowski W, Grundler FMW, Sobczak M. Changes in the structure of Arabidopsis thaliana during female development of the plant-parasitic nematode Heterodera schachtii. Protoplasma. 1996;194:103–116. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wyss U. Observations of the feeding behaviour of Heterodera schachtii throughout development, including events during moulting. Fundam Appl Nematol. 1992;15:75–89. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Böckenhoff A, Prior DAM, Grundler FMW, Oparka KJ. Induction of phloem unloading in Arabidopsis thaliana roots by the parasitic nematode Heterodera schachtii. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:1421–1427. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.4.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juergensen K, Scholz-Starke J, Sauer N, Hess P, van Bel AJE, Grundler FMW. The companion cell-specific Arabidopsis disaccharide carrier AtSUC2 is expressed in nematode-induced syncytia. Plant Physiol. 2003;131:61–69. doi: 10.1104/pp.008037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoth S, Schneidereit A, Lauterbach C, Scholz-Starke J, Sauer N. Nematode infection triggers the de novo formation of unloading phloem that allows macromolecular trafficking of green fluorescent protein into syncytia. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:383–392. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.058800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hofmann J, Grundler FMW. Females and males of root-parasitic cyst nematodes induce different symplasmic connections between their syncytial feeding cells and the phloem in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2006;44:430–433. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofmann J, Wieczorek K, Blöchl A, Grundler FMW. Sucrose supply to nematode-induced syncytia depends on the apoplasmic and the symplasmic pathway. J Exp Bot. 2007;58:1591–1601. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Böckenhoff A. Untersuchungen zur Physiologie der Nährstoffversorgung des Rübenzystennematoden Heterodera schachtii und der von ihm induzierten Nährzellen in Wurzeln von Arabidopsis thaliana unter Verwendung einer speziell adaptierten in situ Mikroinjektionstechnik. Institut für Phytopathologie, Christian-Albrecht Universität; 1995. (Ger). PhD thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dennis DT, Blakeley SD. Carbohydrate metabolism. In: Buchanan BB, Gruissem W, Jones RL, editors. Biochemistry and molecular biology of plants, Ed 1. Rockville: American Society of Plant Biologists; 2000. pp. 630–675. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofmann J, Szakasits D, Blöchl A, Sobczak M, Daxböck-Horvath S, Golinowski W, Bohlmann H, Grundler FMW. Starch serves as carbohydrate storage in nematode-induced syncytia. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:228–235. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.107367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delvallé D, Dumez S, Wattebled F, Roldán I, Planchot V, Berbezy P, Colonna P, Vyas D, Chatterjee M, Ball S, Mérida A, D'Hulst C. Soluble starch synthase I: a major determinant for the synthesis of amylopectin in Arabidopsis thaliana leaves. Plant J. 2005;43:398–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sijmons PC, Grundler FMW, von Mende S, Burrows PR, Wyss U. Arabidopsis thaliana as a new model host for plant parasitic nematodes. Plant J. 1991;1:245–254. [Google Scholar]